A Seismic Horizon Identification Method Based on scSE-VGG16-UNet++

Abstract

1. Introduction

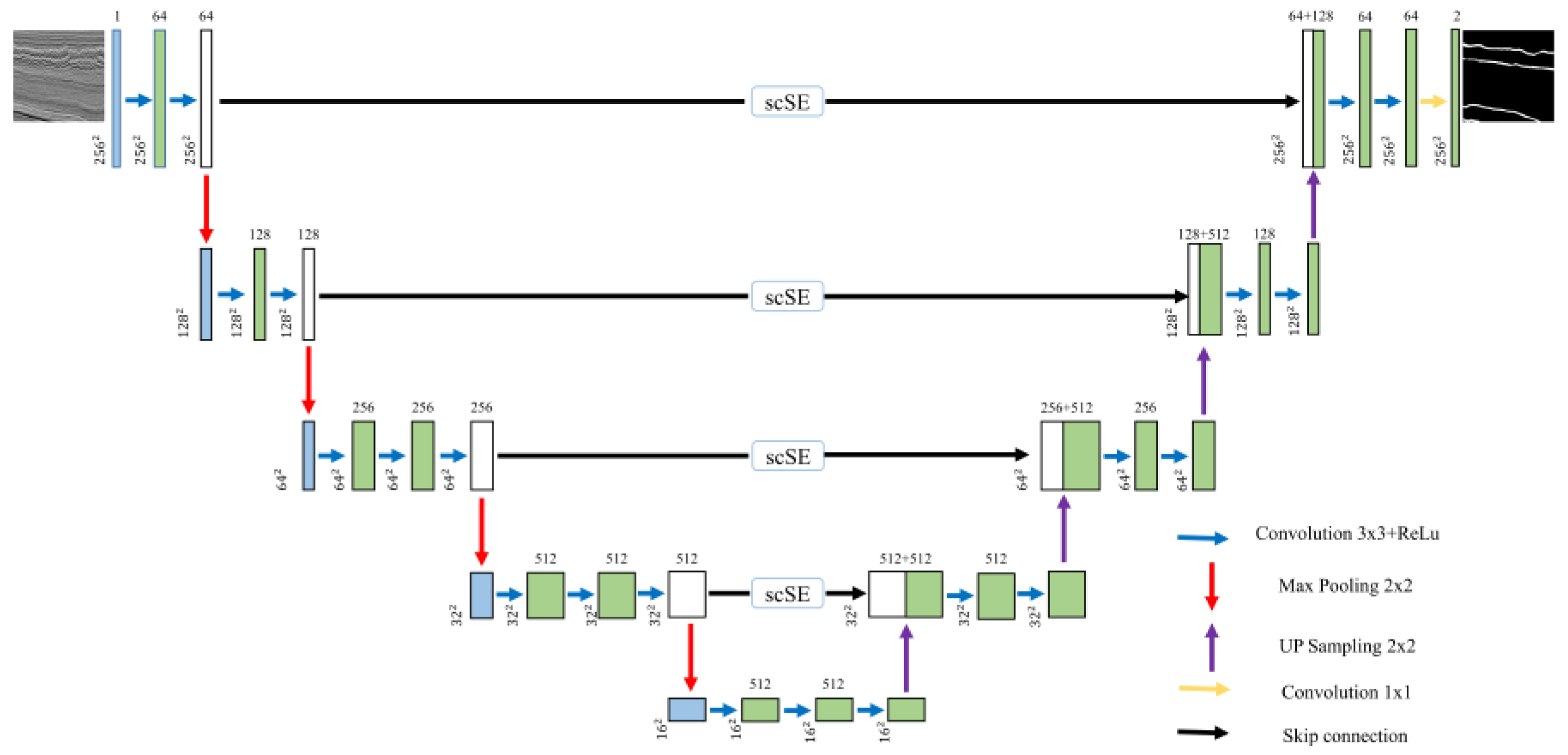

2. The Data-Augmented scSE-VGG16-UNet++

2.1. UNet

2.2. VGG16-UNet

2.3. VGG16-UNet++

2.4. Data Augmentation Techniques

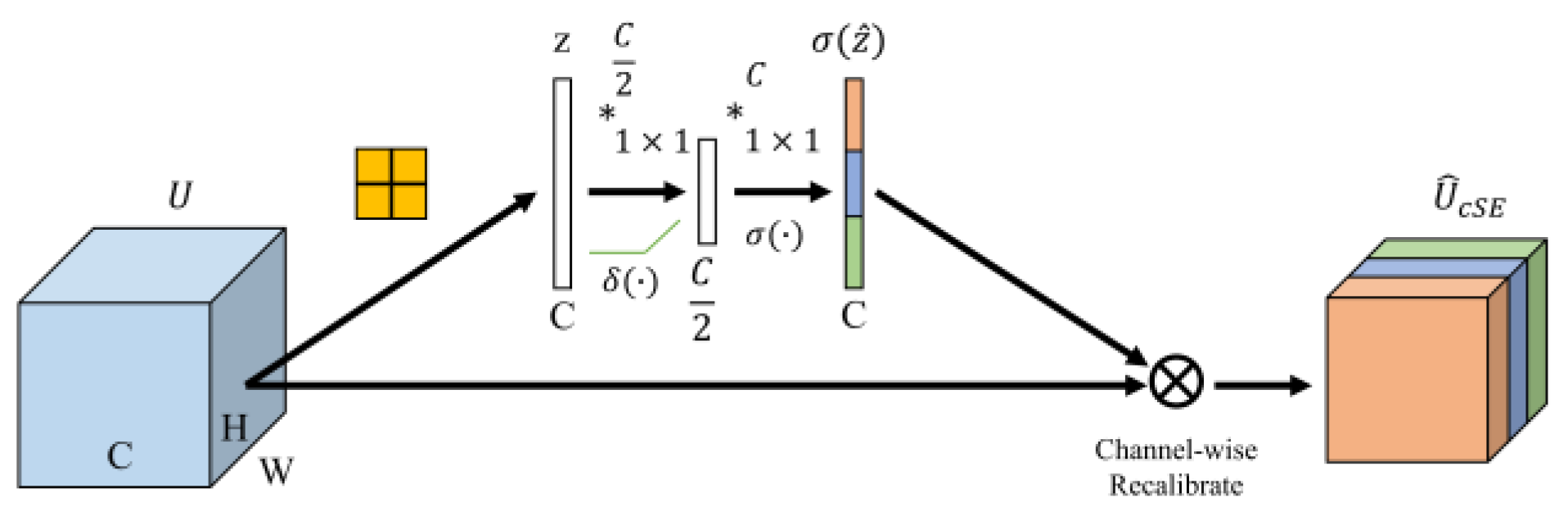

2.5. scSE Attention Mechanism

2.6. The Data-Augmented scSE-VGG16-UNet++

2.7. Loss Function and Optimizer

2.8. Evaluation Criteria

3. Datasets and Experimental Setup

3.1. Horizon Identification Workflow

3.2. Dataset Construction

3.3. Experimental Setup

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Comparative Experiment

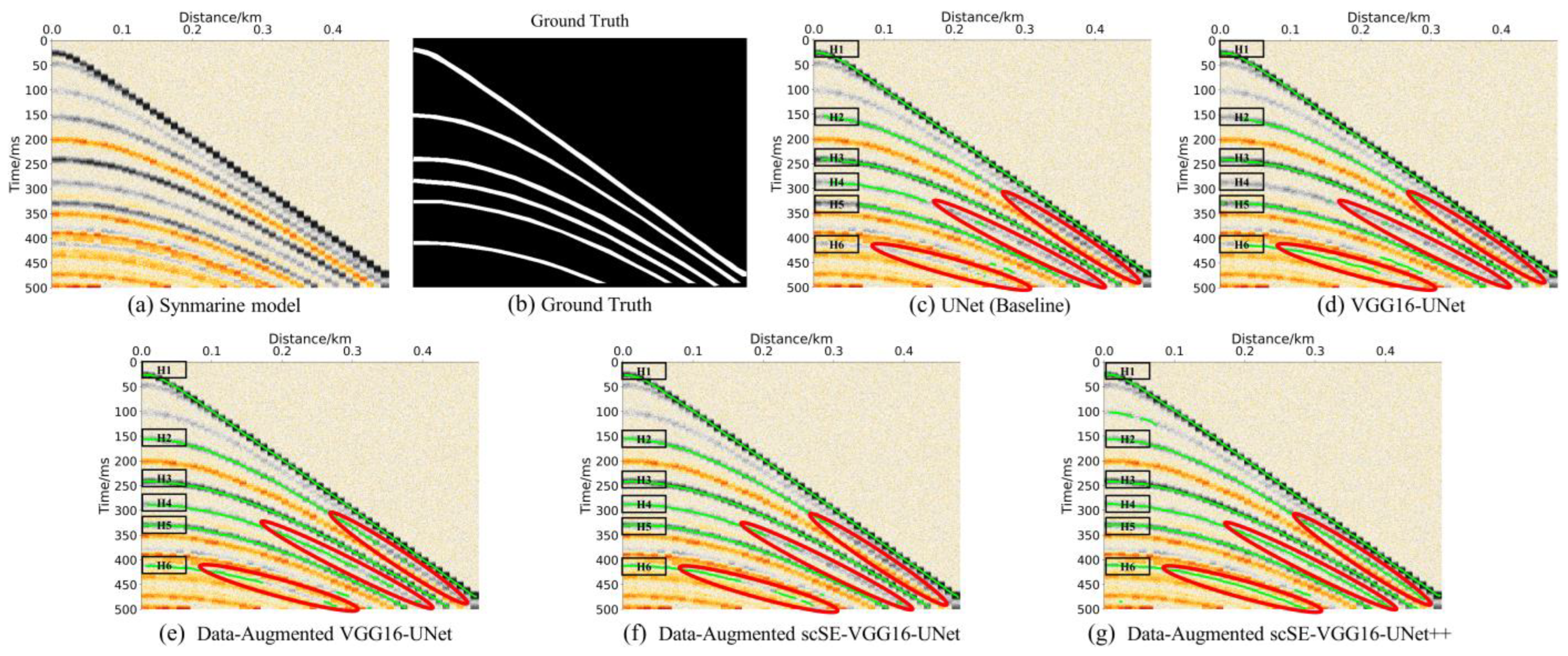

4.2. Synthetic Model Testing

4.3. Application to Field Data

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The VGG16-UNet architecture is constructed by integrating the deep feature extraction capabilities of VGG16 with the traditional UNet network architecture. This architecture is then applied this architecture to seismic horizon identification for the first time, and the experimental results confirmed its effectiveness for this task.

- (2)

- To address the high cost of seismic data annotation and the high similarity of sample features within a single survey area, this paper, for the first time, adopts data augmentation techniques tailored to the strong lateral continuity of seismic horizons to effectively enrich seismic profile features. The experimental results demonstrate that data augmentation can effectively alleviate discontinuities in seismic horizon identification caused by limited data diversity, and can also improve the identification capability of the network architecture on noisy data.

- (3)

- This paper introduced the scSE attention mechanism at the skip connections of the VGG16-UNet for the first time. This enabled the architecture to focus on horizon boundary information while suppressing interference from noise and non-target regions. The quantitative evaluation showed that the introduction of scSE significantly improved the accuracy and continuity of the identification results.

- (4)

- Building upon the scSE-VGG16-UNet method, the dense connections and deep supervision mechanisms of UNet++ and combined with data augmentation to form the final network architecture. The final network architecture demonstrated superior performance over the VGG16-UNet and all intermediate network architectures, both in quantitative metrics (PA and mIoU) and in qualitative tests on synthetic model data and field data. Furthermore, it exhibited strong noise resistance on noisy data, indicating its potential for intelligent horizon identification in complex seismic datasets and its good generalization ability.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Shi, X.; Wei, X.; Yang, C.; Ma, H.; Li, Y. Problems and Countermeasures for Construction of China’s Salt Cavern Type Strategic Oil Storage. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. Chin. Version 2023, 38, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aki, K.; Richards, P.G. Quantitative Seismology; University Science Books: New York, NY, USA, 2002; ISBN 978-1891389634. [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz, Ö. Seismic Data Analysis: Processing, Inversion, and Interpretation of Seismic Data; Society of Exploration Geophysicists: Houston, TX, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Harishidayat, D.; Al-Shuhail, A.; Randazzo, G.; Lanza, S.; Muzirafuti, A. Reconstruction of Land and Marine Features by Seismic and Surface Geomorphology Techniques. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgos, H.G.; Skov, T.; Randen, T.; Sonneland, L. Automated Geometry Extraction from 3D Seismic Data. In Proceedings of the SEG International Exposition and Annual Meeting, Dallas, TX, USA, 26–31 October 2003; SEG: Houston, TX, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Marfurt, K.J.; Kirlin, R.L.; Farmer, S.L.; Bahorich, M.S. 3-D Seismic Attributes Using a Semblance-based Coherency Algorithm. Geophysics 1998, 63, 1150–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gersztenkorn, A.; Marfurt, K.J. Eigenstructure-based Coherence Computations as an Aid to 3-D Structural and Stratigraphic Mapping. Geophysics 1999, 64, 1468–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hale, D. Dynamic Warping of Seismic Images. Geophysics 2013, 78, S105–S115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Wu, X. Seismic Horizon Extraction with Dynamic Programming. Geophysics 2021, 86, IM51–IM62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, L.G. Machine Perception of Three-Dimensional Solids. Ph.D. Thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Prewitt, J.M. Object Enhancement and Extraction. Pict. Process. Psychopictorics 1970, 10, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Faraklioti, M.; Petrou, M. Horizon Picking in 3D Seismic Data Volumes. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2004, 15, 216–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, C.; Tao, C. The Study of Application of Edge Measuring Technique to the Detection of Phase Axis of Seismic Section. Prog. Geophys. 2007, 22, 1607–1610. [Google Scholar]

- Li, P.; Feng, X.; Wang, D.; Liu, C.; Li, H.X. Auto Tracking the Sync Phase Axis of Seismic Profiles. J. Jilin Univ. Earth Sci. Ed. 2008, 38, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herron, D.A. Horizon Autopicking. Lead. Edge 2000, 19, 491–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; David, J.M.; Kim, S.H. The Fourth Industrial Revolution: Opportunities and Challenges. Int. J. Financ. Res. 2018, 9, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, W.S.; Pitts, W. A Logical Calculus of the Ideas Immanent in Nervous Activity. Bull. Math. Biophys. 1943, 5, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenblatt, F. The Perceptron: A Probabilistic Model for Information Storage and Organization in the Brain. Psychol. Rev. 1958, 65, 386–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning Representations by Back-Propagating Errors. Nature 1986, 323, 533–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohonen, T. Self-Organized Formation of Topologically Correct Feature Maps. Biol. Cybern. 1982, 43, 59–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopfield, J.J. Neural Networks and Physical Systems with Emergent Collective Computational Abilities. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1982, 79, 2554–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosko, B. Bidirectional Associative Memories. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1988, 18, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bottou, L.; Bengio, Y.; Haffner, P. Gradient-Based Learning Applied to Document Recognition. Proc. IEEE 2002, 86, 2278–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, C.; Chow, M.-Y.; Li, X.; Tian, J.; Luo, H.; Yin, S. A Data-Model Interactive Remaining Useful Life Prediction Approach of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on PF-BiGRU-TSAM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 20, 1144–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosro Anjom, F.; Vaccarino, F.; Socco, L.V. Machine Learning for Seismic Exploration: Where Are We and How Far Are We from the Holy Grail? Geophysics 2024, 89, WA157–WA178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Shi, Y.; Fomel, S.; Liang, L. Convolutional Neural Networks for Fault Interpretation in Seismic Images. In Proceedings of the SEG Technical Program Expanded Abstracts 2018, Anaheim, CA, USA, 14–19 October 2018; Society of Exploration Geophysicists: Anaheim, CA, USA, 2018; pp. 1946–1950. [Google Scholar]

- Di, H.; Li, Z.; Maniar, H.; Abubakar, A. Seismic Stratigraphy Interpretation by Deep Convolutional Neural Networks: A Semisupervised Workflow. Geophysics 2020, 85, WA77–WA86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wu, X.; Fomel, S. Waveform Embedding: Automatic Horizon Picking with Unsupervised Deep Learning. Geophysics 2020, 85, WA67–WA76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Sun, S.-Z. Seismic Horizon Tracking Using a Deep Convolutional Neural Network. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 187, 106709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tschannen, V.; Delescluse, M.; Ettrich, N.; Keuper, J. Extracting Horizon Surfaces from 3D Seismic Data Using Deep Learning. Geophysics 2020, 85, N17–N26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.; Cao, J.; You, J.; Wang, J.; Liu, J. Automatic Horizon Tracking Method Based on Image Semantic Segmentation. Prog. Geophys. 2021, 36, 1504–1511. [Google Scholar]

- Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.; Xie, E.; Wang, W. Simple and Efficient Design for Semantic Segmentation with Transformers . Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021. submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin Transformer: Hierarchical Vision Transformer Using Shifted Windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10012–10022. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Zhao, J. Seismic Horizon Tracking Based on the TransUnet Model. Geophysics 2025, 90, IM1–IM13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salamon, J.; Bello, J.P. Deep Convolutional Neural Networks and Data Augmentation for Environmental Sound Classification. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2017, 24, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di, H.; Li, C.; Smith, S.; Li, Z.; Abubakar, A. Imposing Interpretational Constraints on a Seismic Interpretation Convolutional Neural Network. Geophysics 2021, 86, IM63–IM71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, P. Feed Forward and Backward Run in Deep Convolution Neural Network. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1711.03278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, S.; Chaki, A.; Santosh, K. Improved U-Net Architecture with VGG-16 for Brain Tumor Segmentation. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2021, 44, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention, Munich, Germany, 5–9 October 2015; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very Deep Convolutional Networks for Large-Scale Image Recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- Hahnloser, R.H.; Sarpeshkar, R.; Mahowald, M.A.; Douglas, R.J.; Seung, H.S. Digital Selection and Analogue Amplification Coexist in a Cortex-Inspired Silicon Circuit. Nature 2000, 405, 947–951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nair, V.; Hinton, G.E. Rectified Linear Units Improve Restricted Boltzmann Machines. In Proceedings of the 27th International Conference on Machine Learning (ICML-10), Haifa, Israel, 21–24 June 2010; pp. 807–814. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Siddiquee, M.M.R.; Tajbakhsh, N.; Liang, J. UNet++: A Nested U-Net Architecture for Medical Image Segmentation. In Deep Learning in Medical Image Analysis and Multimodal Learning for Clinical Decision Support; Springer Nature: Berlin, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Lei, F.; Zang, Z.; Zhang, M. Forest Mapping Using a VGG16-UNet++& Stacking Model Based on Google Earth Engine in the Urban Area. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2023, 20, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jähne, B. Digital Image Processing; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, A.G.; Navab, N.; Wachinger, C. Concurrent Spatial and Channel ‘Squeeze & Excitation’ in Fully Convolutional Networks. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention—Miccai 2018; Frangi, A.F., Schnabel, J.A., Davatzikos, C., Alberola-López, C., Fichtinger, G., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 11070, pp. 421–429. ISBN 978-3-030-00927-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, J.; Shen, L.; Sun, G. Squeeze-and-Excitation Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7132–7141. [Google Scholar]

- Kinga, D.; Adam, J.B. A Method for Stochastic Optimization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR), San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015; Volume 5. [Google Scholar]

- De Boer, P.-T.; Kroese, D.P.; Mannor, S.; Rubinstein, R.Y. A Tutorial on the Cross-Entropy Method. Ann. Oper. Res. 2005, 134, 19–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claerbout, J.F.; Green, I. Basic Earth Imaging; Citeseer: University Park, PA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Alaudah, Y.; Michałowicz, P.; Alfarraj, M.; AlRegib, G. A Machine-Learning Benchmark for Facies Classification. Interpretation 2019, 7, SE175–SE187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Predicted Class | Actual Class | |

|---|---|---|

| Target Horizon | Non-Target Horizon | |

| Target Horizon | TP | FN |

| Non-Target Horizon | FP | TN |

| Component | Specification |

|---|---|

| GPU | Nvidia GeForce RTX 4070 Ti Super |

| VRAM | 16 GB |

| Operation System | Windows 11 |

| Programming Language | Python 3.8.5 |

| Deep Learning Framework | Pytorch 1.12 |

| Cuda | 12.4 |

| Method (Architecture) | PA | mIoU |

|---|---|---|

| M0 (UNet) | 92.54 | 46.24 |

| M1 (VGG16-UNet) | 93.01 | 46.96 |

| M2 (Data-Augmented VGG16-UNet) | 93.24 | 50.19 |

| M3 (Data-Augmented scSE-VGG16-UNet) | 94.11 | 50.69 |

| M4 (Data-Augmented scSE-VGG16-UNet++) | 97.70 | 79.23 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wang, Q.; Liu, C.; Liu, Y.; Fan, J.; Wang, D.; Lu, Q.; Li, P. A Seismic Horizon Identification Method Based on scSE-VGG16-UNet++. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010394

Wang Q, Liu C, Liu Y, Fan J, Wang D, Lu Q, Li P. A Seismic Horizon Identification Method Based on scSE-VGG16-UNet++. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):394. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010394

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Qin, Cai Liu, Yang Liu, Jiaqi Fan, Dian Wang, Qi Lu, and Peng Li. 2026. "A Seismic Horizon Identification Method Based on scSE-VGG16-UNet++" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010394

APA StyleWang, Q., Liu, C., Liu, Y., Fan, J., Wang, D., Lu, Q., & Li, P. (2026). A Seismic Horizon Identification Method Based on scSE-VGG16-UNet++. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 394. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010394