LIDAR Observation and Numerical Simulation of Building-Induced Airflow Disturbances and Their Potential Impact on Aircraft Operation at an Operating Airport

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Meteorological Instrumentation

3. Setup of Numerical Models

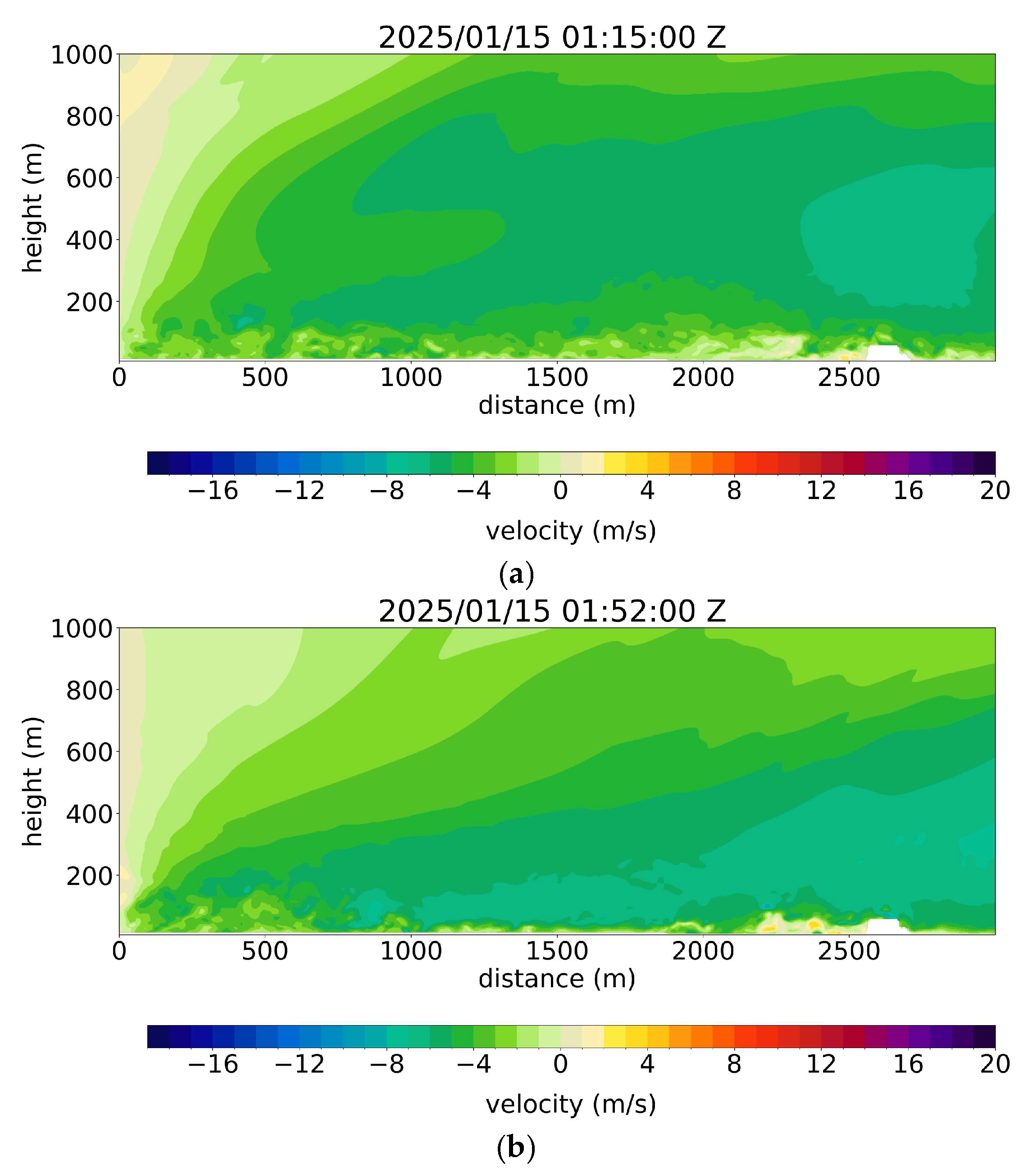

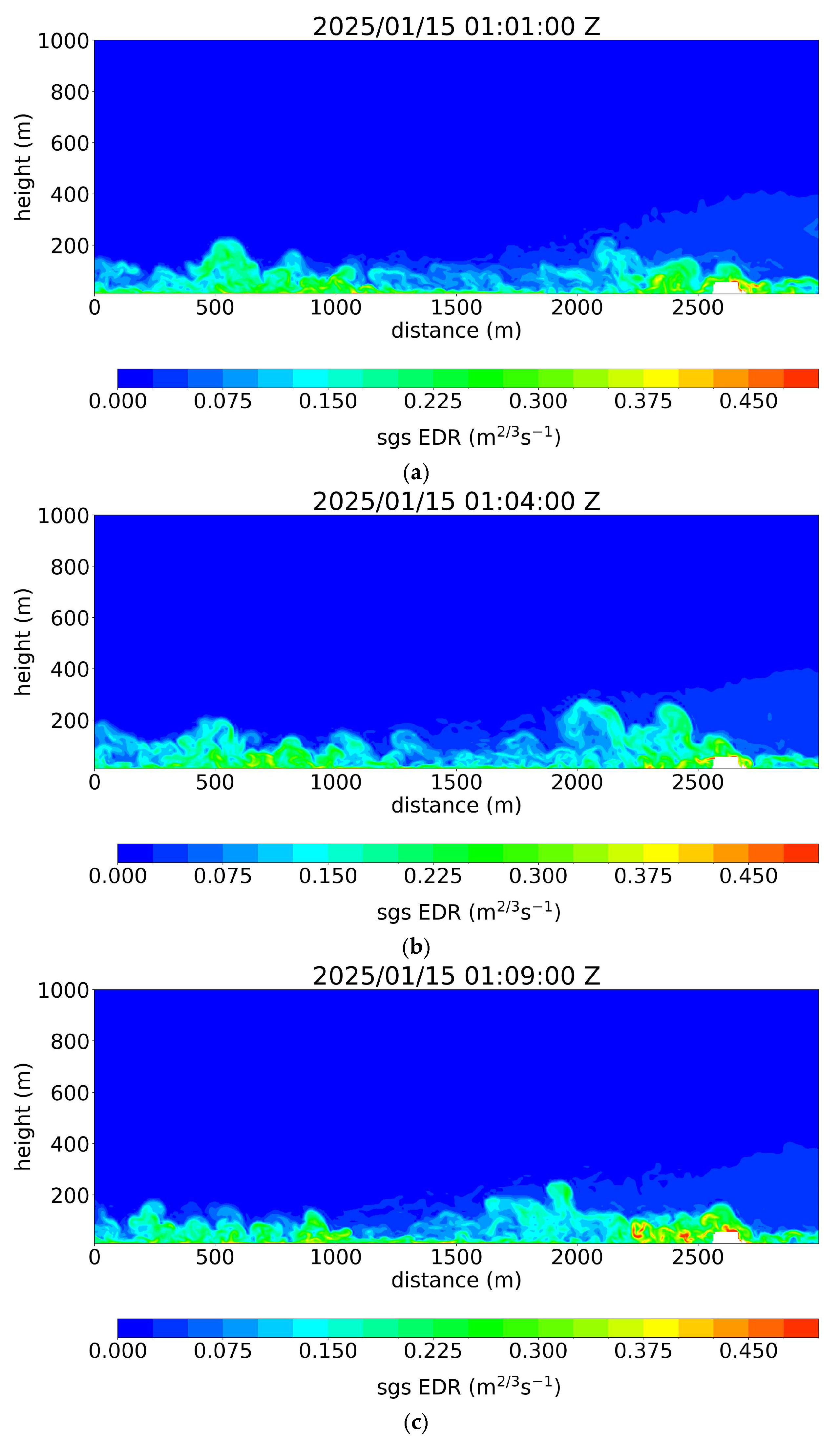

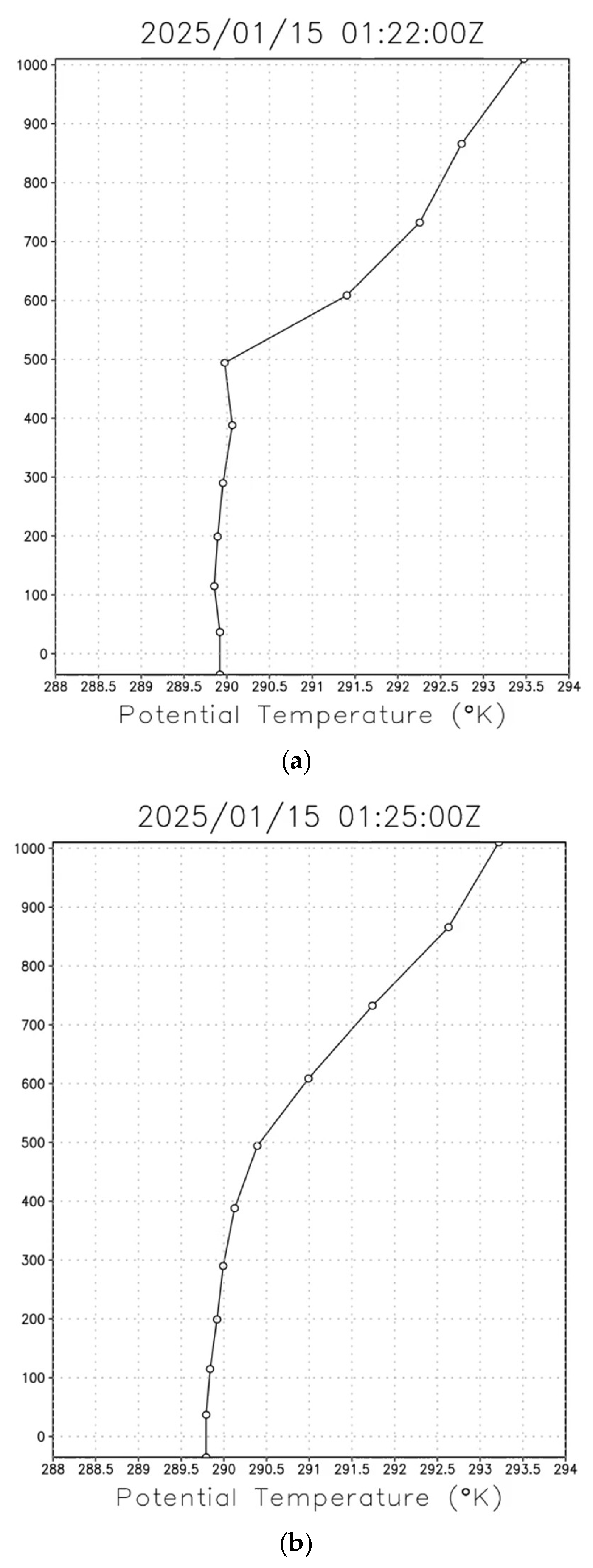

3.1. Case Study 1: 15 January 2025

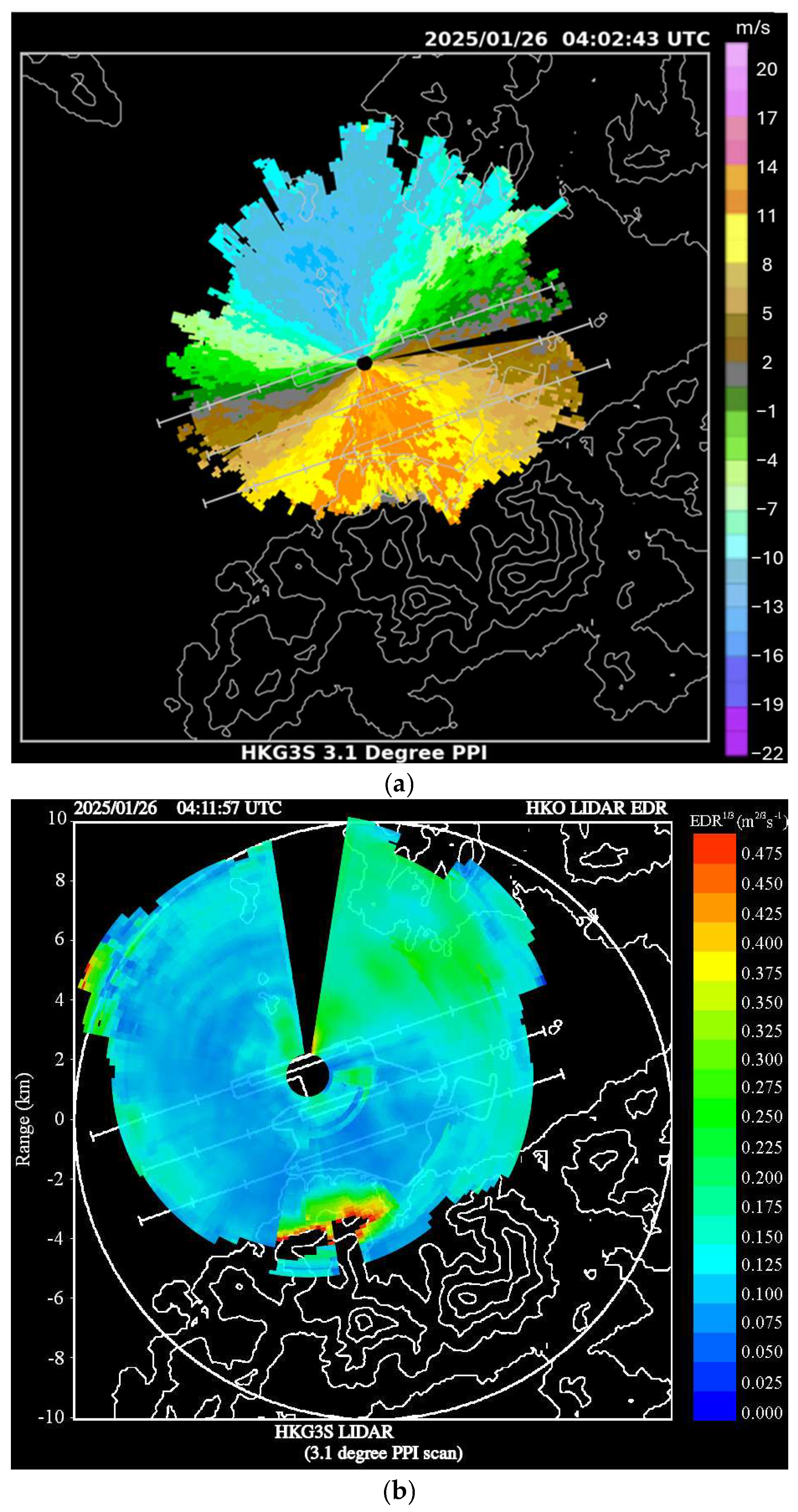

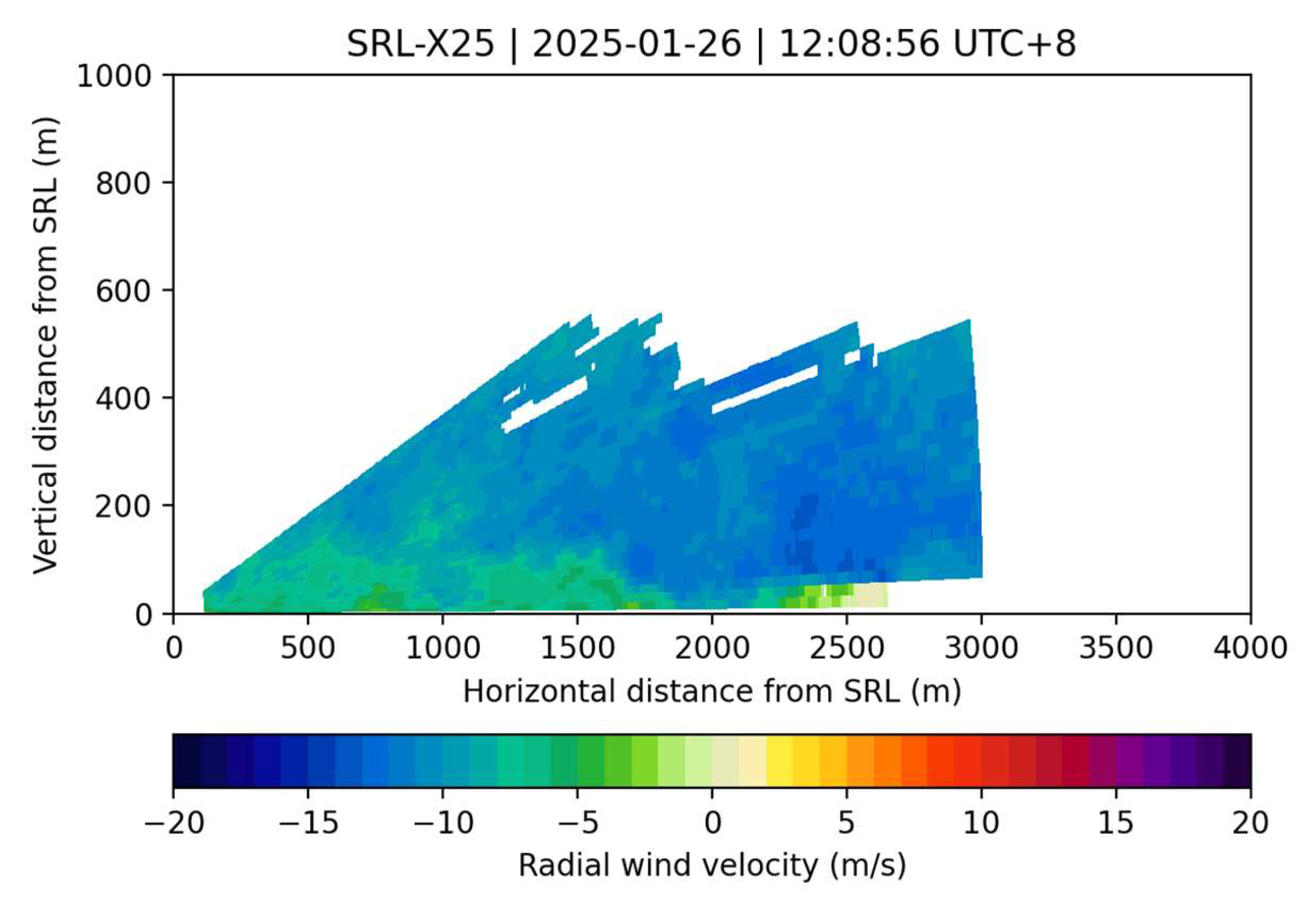

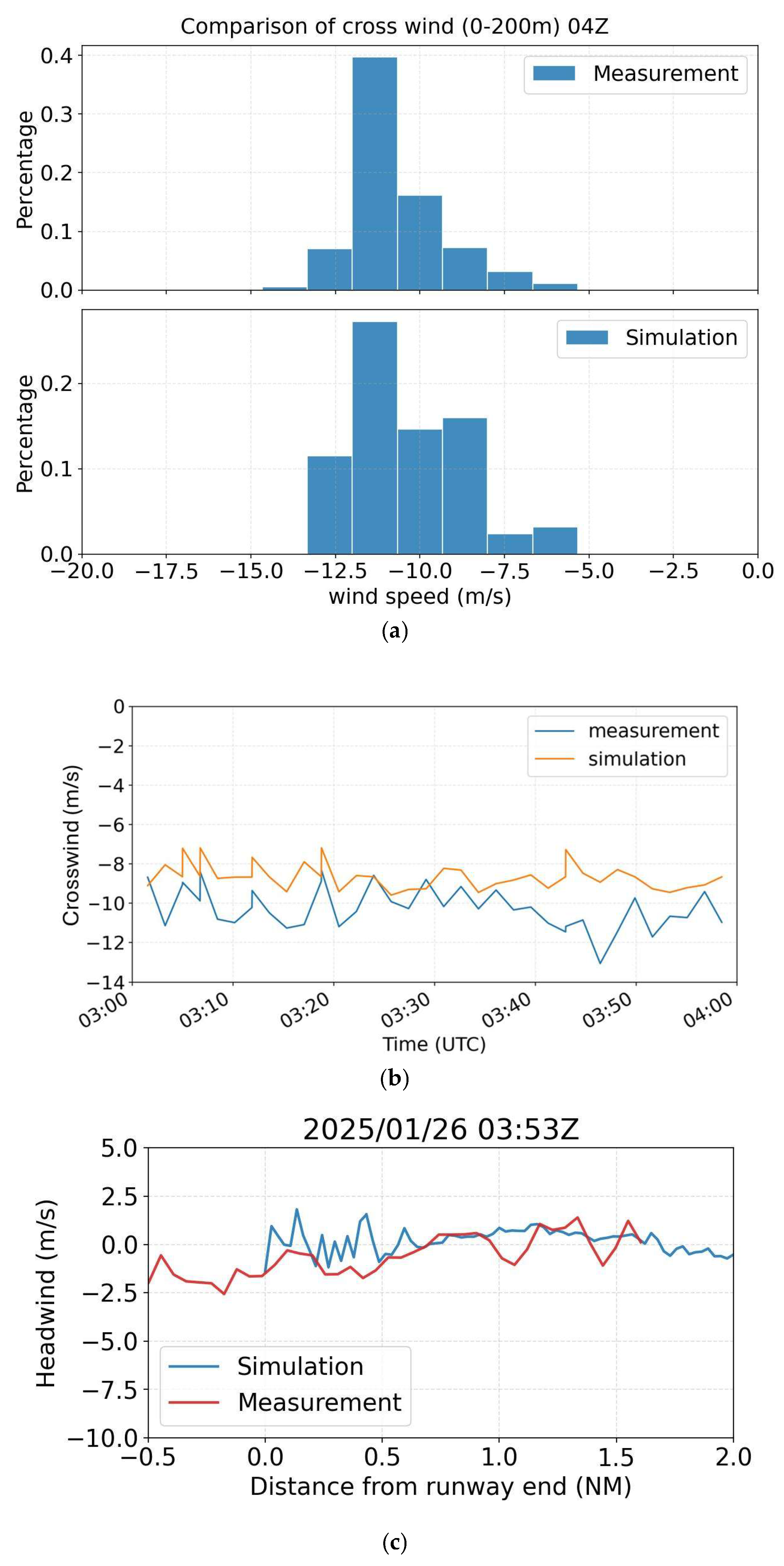

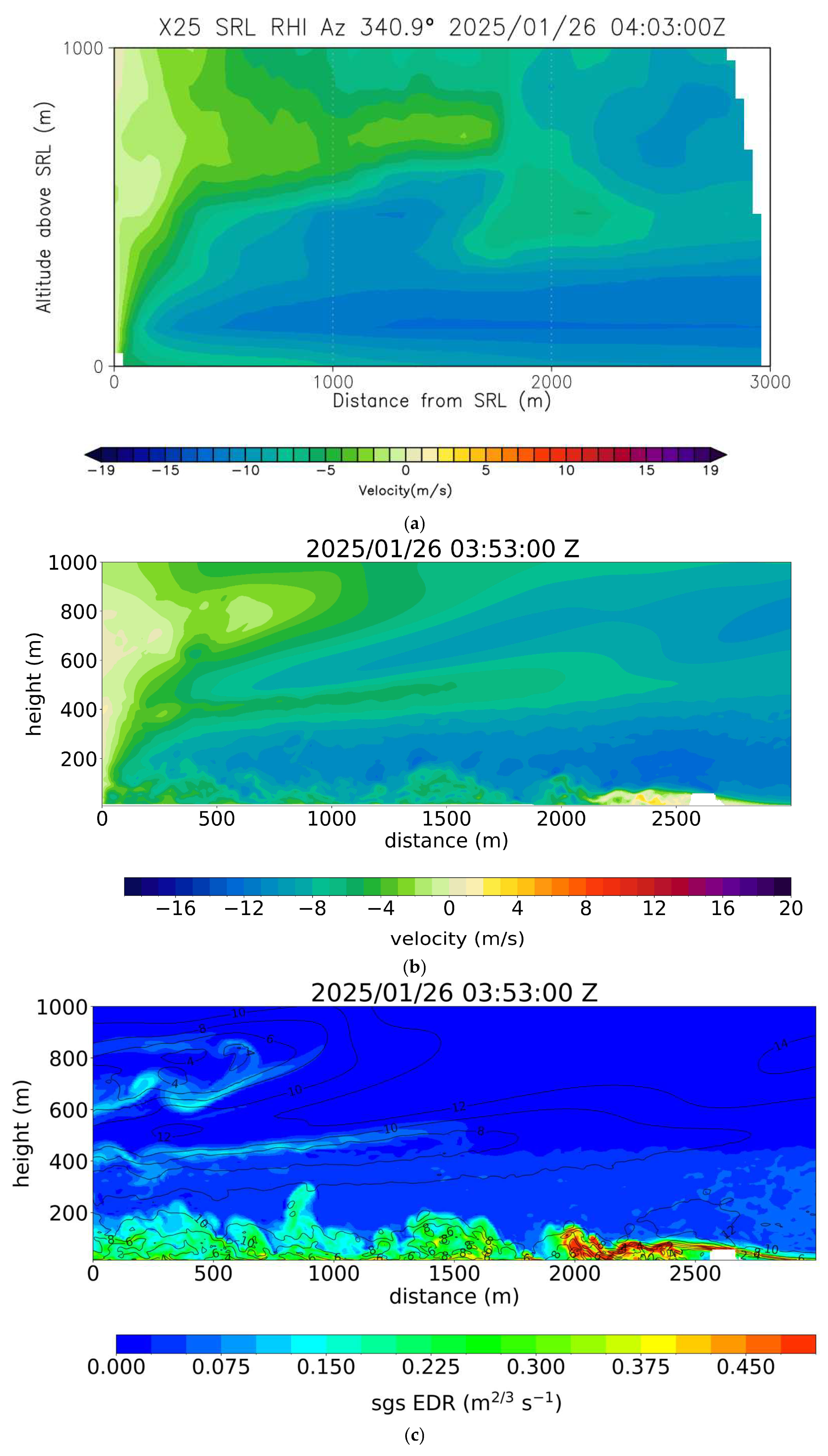

3.2. Case Study 2: 26 January 2025

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Coceal, O.; Dobre, A.; Thomas, T.G. Unsteady Dynamics and Organized Structures from DNS over an Idealized Building Canopy. Int. J. Climatol. 2007, 27, 1943–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hertwig, D.; Gough, H.L.; Grimmond, S.; Barlow, J.F.; Kent, C.W.; Lin, W.E.; Robins, A.G.; Hayden, P. Wake Characteristics of Tall Buildings in a Realistic Urban Canopy. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 2019, 172, 239–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, H.; Lee, S. Impact of Heterogeneous Building Arrangement on Local Turbulence Escalation. Build. Environ. 2023, 236, 110217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southgate-Ash, C.; Mishra, A.; Grimmond, S.; Robins, A.; Placidi, M. Wake Characteristics of Multiscale Buildings in a Turbulent Boundary Layer. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 2025, 191, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, H.H.; Muñoz-Esparza, D.; Sauer, J.A.; Steiner, M. Large-Eddy Simulations of Stability-Varying Atmospheric Boundary Layer Flow over Isolated Buildings. J. Atmos. Sci. 2021, 78, 1487–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastner-Klein, P.; Fedorovich, E.; Rotach, M.W. A Wind Tunnel Study of Organised and Turbulent Air Motions in Urban Street Canyons. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2001, 89, 849–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentieri, M.; Hayden, P.; Robins, A.G. Wind Tunnel Measurements of Pollutant Turbulent Fluxes in Urban Intersections. Atmos. Env. 2012, 46, 669–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Mak, C.M.; Cai, C.; Fu, Y.; Tse, K.T.; Niu, J. Wind Tunnel Measurement of Pedestrian-Level Gust Wind Flow and Comfort around Irregular Lift-up Buildings Within Simplified Urban Arrays. Build. Environ. 2024, 256, 111487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadane, A.; Redford, J.A.; Gueguin, M.; Hafid, F.; Ghidaglia, J.-M. CFD Wind Tunnel Investigation for Wind Loading on Angle Members in Lattice Tower Structures. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2023, 236, 105397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tominaga, Y. CFD Simulations of Turbulent Flow and Dispersion in Built Environment: A Perspective Review. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2024, 249, 105741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Weerasuriya, A.U.; Zhang, X.; Tse, K.T.; Lu, B.; Li, C.Y.; Liu, C.-H. Pedestrian Wind Comfort near a Super-Tall Building with Various Configurations in an Urban-like Setting. Build. Simul. 2020, 13, 1385–1408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwpoort, A.M.H.; Gooden, J.H.M.; de Prins, J.L. Wind Criteria Due to Obstacles at and Around Airports; NLR-CR-2006-261; National Aerospace Laboratory NLR: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, P.W. Generation of an Eddy Dissipation Rate Map at the Hong Kong International Airport Based on Doppler Lidar Data. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2011, 28, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wu, S.; Wang, Q.; Liu, B.; Yin, B.; Zhai, X. Airport Low-Level Wind Shear Lidar Observation at Beijing Capital International Airport. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2019, 96, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boilley, A.; Mahfouf, J.-F. Wind Shear over the Nice Côte d’Azur Airport: Case Studies. Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 13, 2223–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshino, K. Low-Level Wind Shear Induced by Horizontal Roll Vortices at Narita International Airport, Japan. J. Meteorol. Soc. Jpn. Ser. II 2019, 97, 403–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüs, H.W.; Haanstra, J.O.; van der Ham, R.; Schreur, B.W. Numerical Simulations of Wind Measurements at Amsterdam Airport Schiphol. J. Wind Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 2003, 91, 1215–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neofytou, P.; Venetsanos, A.G.; Vlachogiannis, D.; Bartzis, J.G.; Scaperdas, A. CFD Simulations of the Wind Environment around an Airport Terminal Building. Environ. Model. Softw. 2006, 21, 520–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chan, P.W. Numerical Simulation Study of the Effect of Buildings and Complex Terrain on the Low-Level Winds at an Airport in Typhoon Situation. Meteorol. Z. 2012, 21, 183–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, K.W.; Hon, K.K.; Chan, P.W.; Li, L.; Li, Q.S. Simulation of Building-Induced Airflow Disturbances in Complex Terrain Using Meteorological-CFD Coupled Model. Meteorol. Z. 2022, 31, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smagorinsky, J. General circulation experiments with the primitive equations: I. The basic experiment. Mon. Weather Rev. 1963, 91, 99–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deardorff, J.W. Stratocumulus-Capped Mixed Layers Derived from a Three-Dimensional Model. Bound. Layer Meteorol. 1980, 18, 495–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maronga, B.; Banzhaf, S.; Burmeister, C.; Esch, T.; Forkel, R.; Fröhlich, D.; Fuka, V.; Gehrke, K.F.; Geletič, J.; Giersch, S.; et al. Overview of the PALM Model System 6.0; Copernicus Publications: Göttingen, Germany, 2020; Volume 13. [Google Scholar]

- Raasch, S.; Schröter, M. PALM—A Large-Eddy Simulation Model Performing on Massively Parallel Computers. Meteorol. Z. 2001, 10, 363–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maronga, B.; Gryschka, M.; Heinze, R.; Hoffmann, F.; Kanani-Sühring, F.; Keck, M.; Ketelsen, K.; Letzel, M.O.; Sühring, M.; Raasch, S. The Parallelized Large-Eddy Simulation Model (PALM) Version 4.0 for Atmospheric and Oceanic Flows: Model Formulation, Recent Developments, and Future Perspectives. Geosci. Model. Dev. 2015, 8, 2515–2551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žuvela-Aloise, M.; Hahn, C.; Hollósi, B. Evaluation of City-Scale PALM Model Simulations and Intra-Urban Thermal Variability in Vienna, Austria Using Operational and Crowdsourced Data. Urban Clim. 2025, 59, 102245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gronemeier, T.; Surm, K.; Harms, F.; Leitl, B.; Maronga, B.; Raasch, S. Evaluation of the Dynamic Core of the PALM Model System 6.0 in a Neutrally Stratified Urban Environment: Comparison between LES and Wind-Tunnel Experiments. Geosci. Model Dev. 2021, 14, 3317–3333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resler, J.; Eben, K.; Geletič, J.; Krč, P.; Rosecký, M.; Sühring, M.; Belda, M.; Fuka, V.; Halenka, T.; Huszár, P.; et al. Validation of the PALM Model System 6.0 in a Real Urban Environment: A Case Study in Dejvice, Prague, the Czech Republic. Geosci. Model Dev. 2021, 14, 4797–4842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicker, L.J.; Skamarock, W.C. Time-Splitting Methods for Elastic Models Using Forward Time Schemes. Mon. Weather Rev. 2002, 130, 2088–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, J.H. Low-Storage Runge-Kutta Schemes. J. Comput. Phys. 1980, 35, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.-T.; Castro, I.P. Efficient Generation of Inflow Conditions for Large Eddy Simulation of Street-Scale Flows. Flow Turbul. Combust. 2008, 81, 449–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Castro, I.P.; Xie, Z.-T. Divergence-Free Turbulence Inflow Conditions for Large-Eddy Simulations with Incompressible Flow Solvers. Comput. Fluids 2013, 84, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.W.; Cheung, P.; Lai, K.K. Observation and Numerical Simulation of Terrain-Induced Airflow Leading to Low Level Windshear at the Hong Kong International Airport Based on Range-Height-Indicator Scans of a LIDAR. Meteorol. Z. 2024, 33, 255–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, P.; Cheung, P.; Chong, M.; Lai, K. New Observations of Airflow at Hong Kong International Airport by Range Height Indicator (RHI) Scans of LIDARs and Their Numerical Simulation. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 9655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lo, K.W.; Chan, P.W.; Cheung, P.; Lai, K.K.; Dong, Y. LIDAR Observation and Numerical Simulation of Building-Induced Airflow Disturbances and Their Potential Impact on Aircraft Operation at an Operating Airport. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010404

Lo KW, Chan PW, Cheung P, Lai KK, Dong Y. LIDAR Observation and Numerical Simulation of Building-Induced Airflow Disturbances and Their Potential Impact on Aircraft Operation at an Operating Airport. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):404. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010404

Chicago/Turabian StyleLo, Ka Wai, Pak Wai Chan, Ping Cheung, Kai Kwong Lai, and You Dong. 2026. "LIDAR Observation and Numerical Simulation of Building-Induced Airflow Disturbances and Their Potential Impact on Aircraft Operation at an Operating Airport" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010404

APA StyleLo, K. W., Chan, P. W., Cheung, P., Lai, K. K., & Dong, Y. (2026). LIDAR Observation and Numerical Simulation of Building-Induced Airflow Disturbances and Their Potential Impact on Aircraft Operation at an Operating Airport. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 404. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010404