Agent-Based Decentralized Manufacturing Execution System via Employment Network Collaboration

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Agent-Based MES

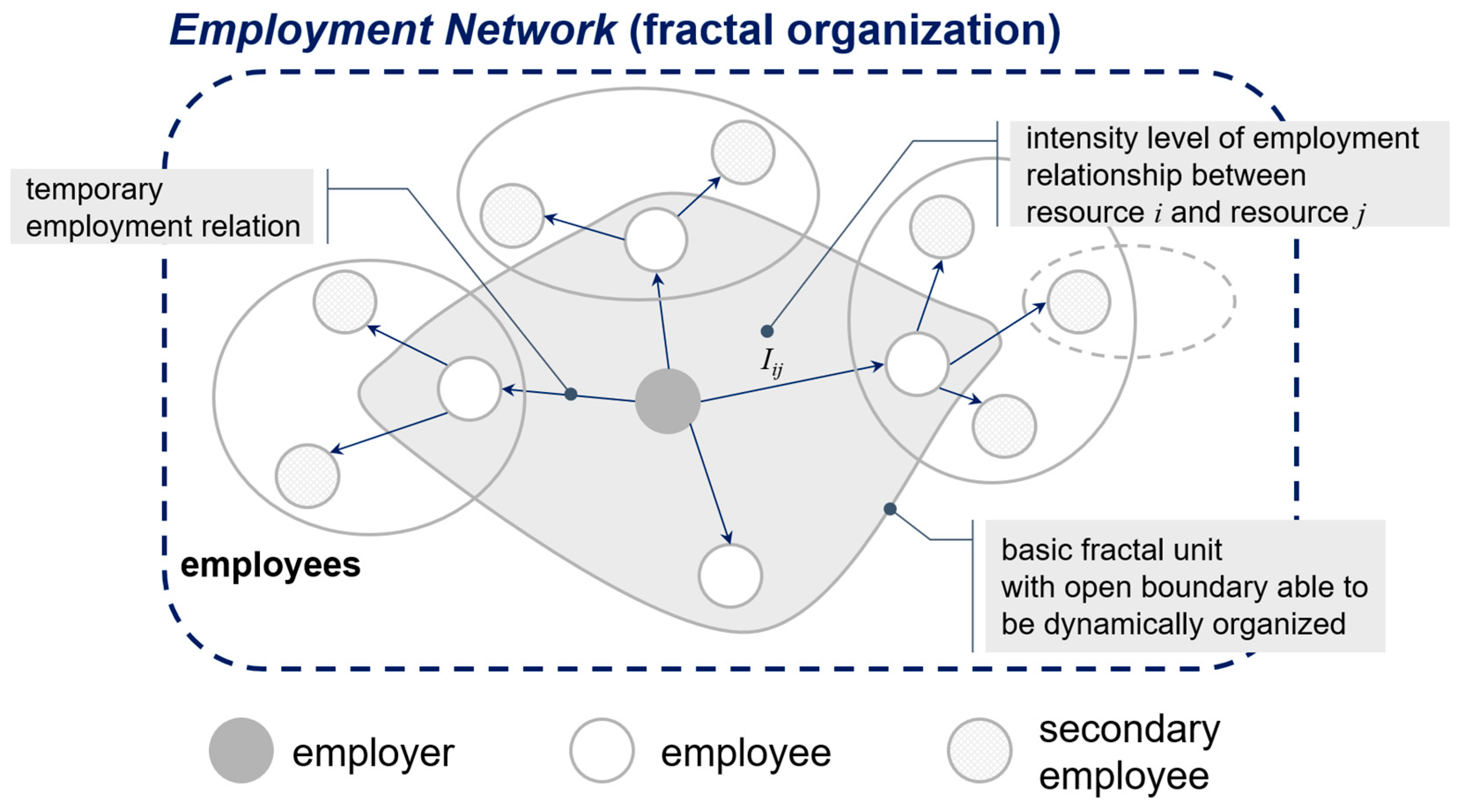

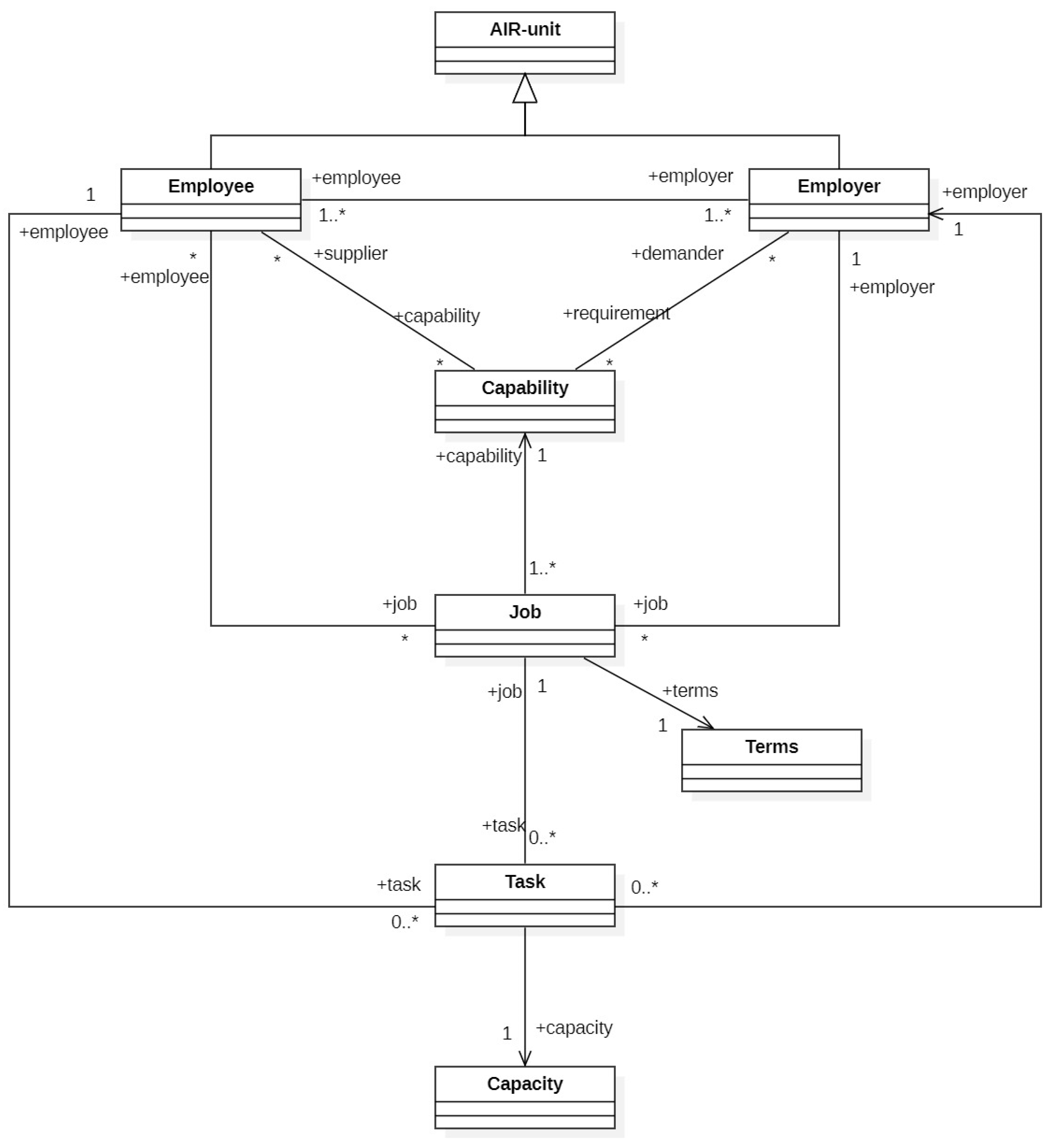

2.2. EmNet-Based Collaboration

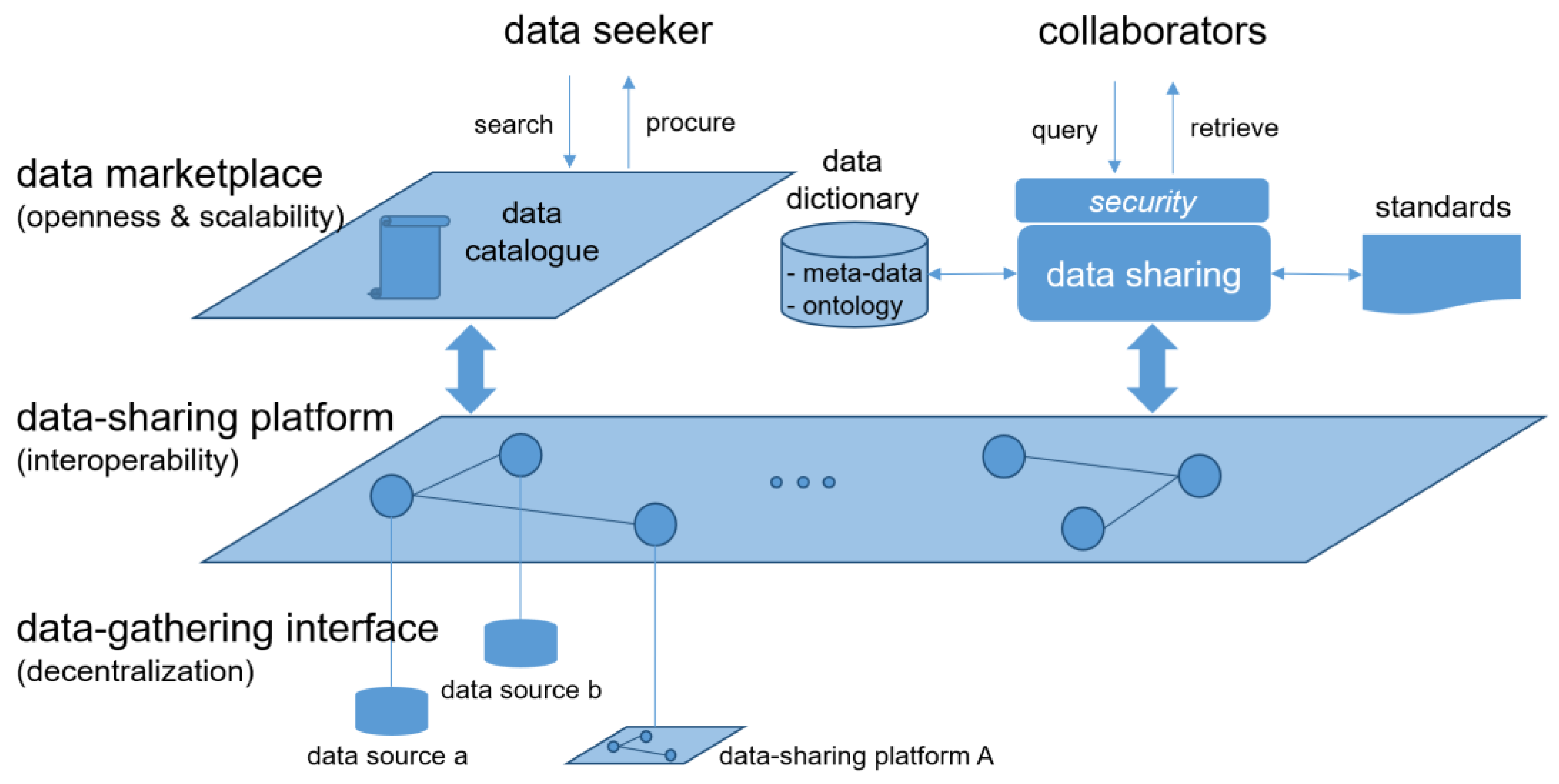

2.3. Data-Space-Based Collaboration Platform

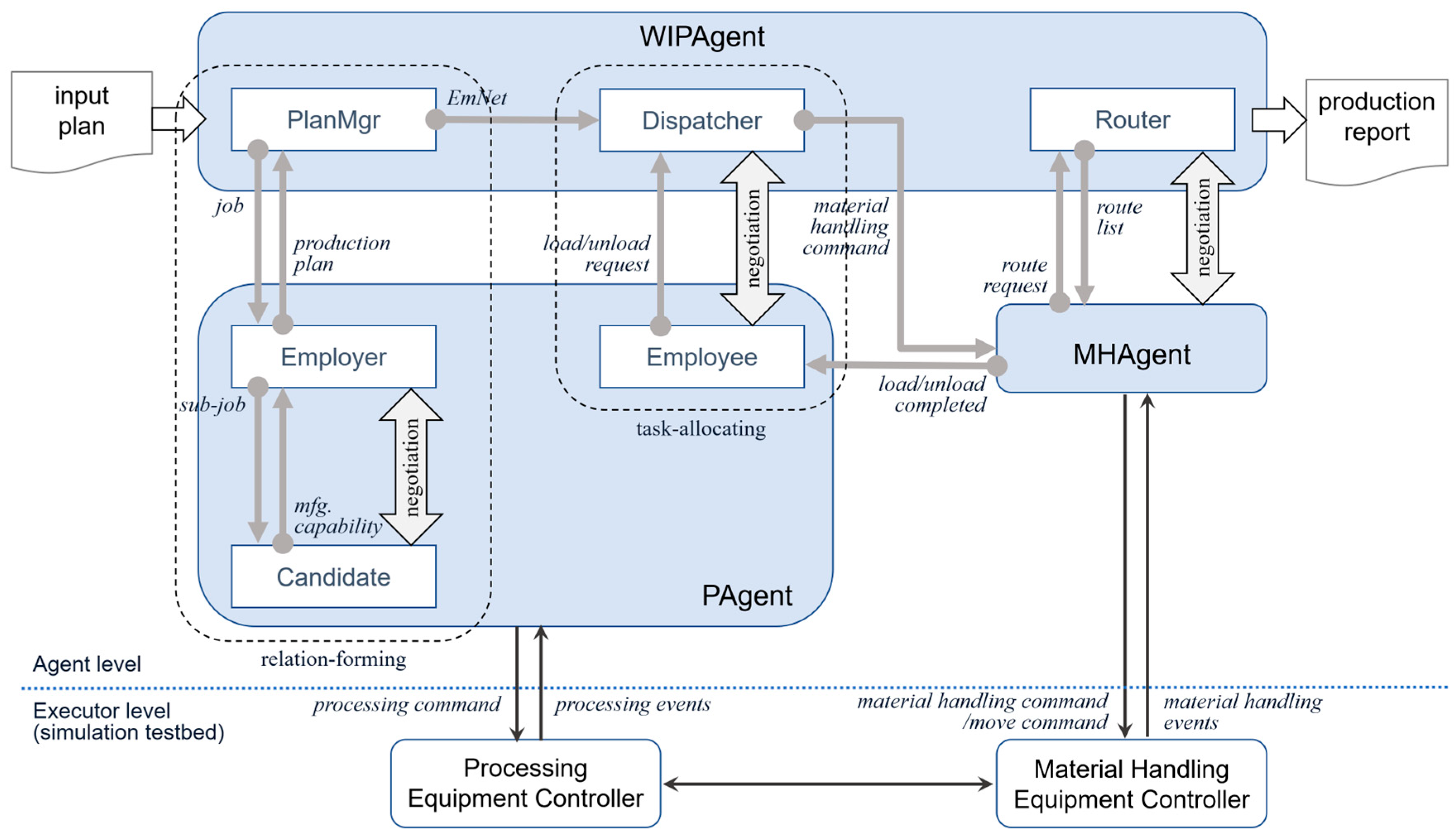

3. EmNet-Based Manufacturing Execution System

3.1. Conceptual Architecture

3.1.1. Constituent Agents

3.1.2. Manufacturing Execution Functions

3.2. Collaboration Mechanism

3.2.1. Employment Contract

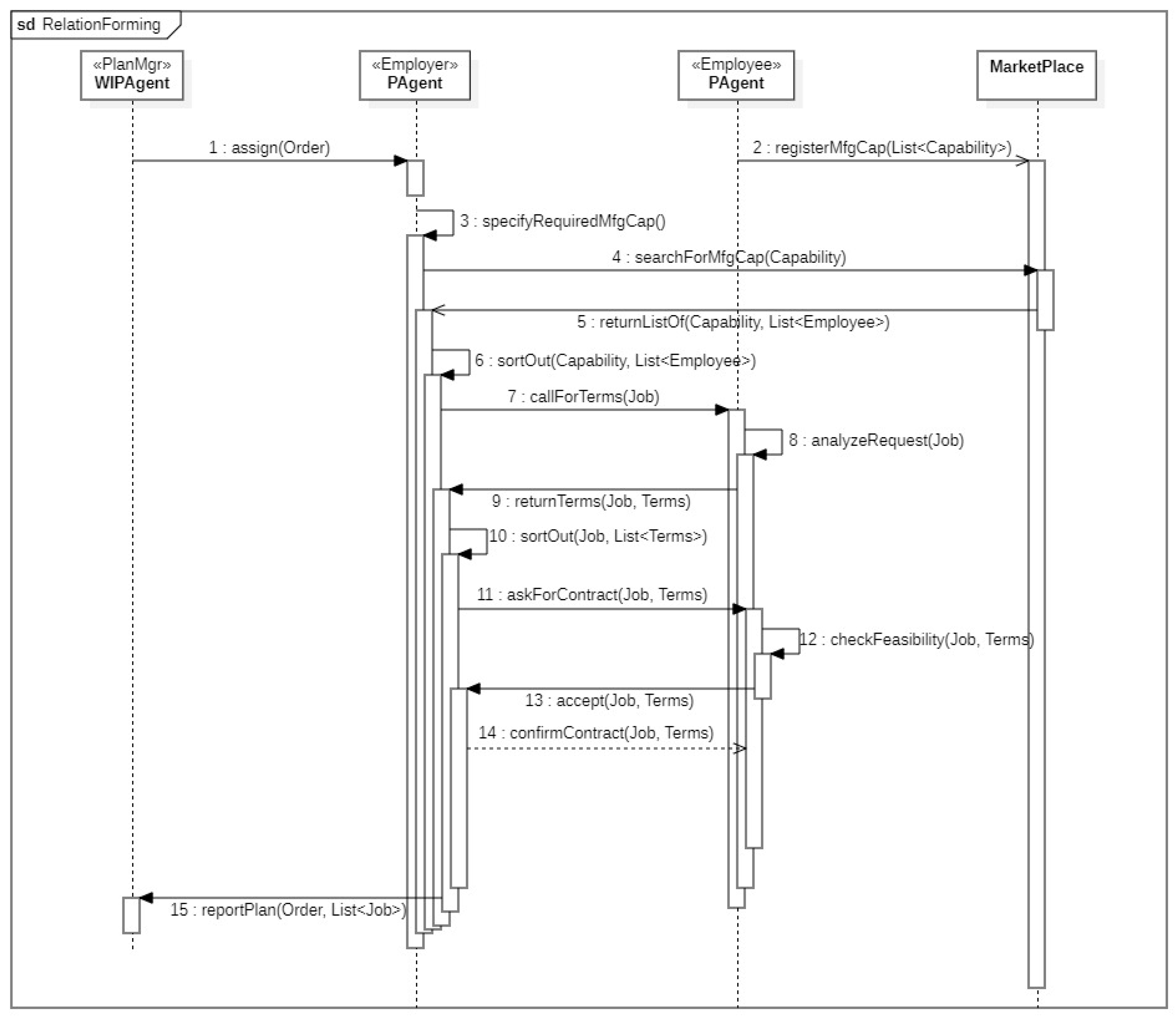

3.2.2. Relation-Forming (Planning)

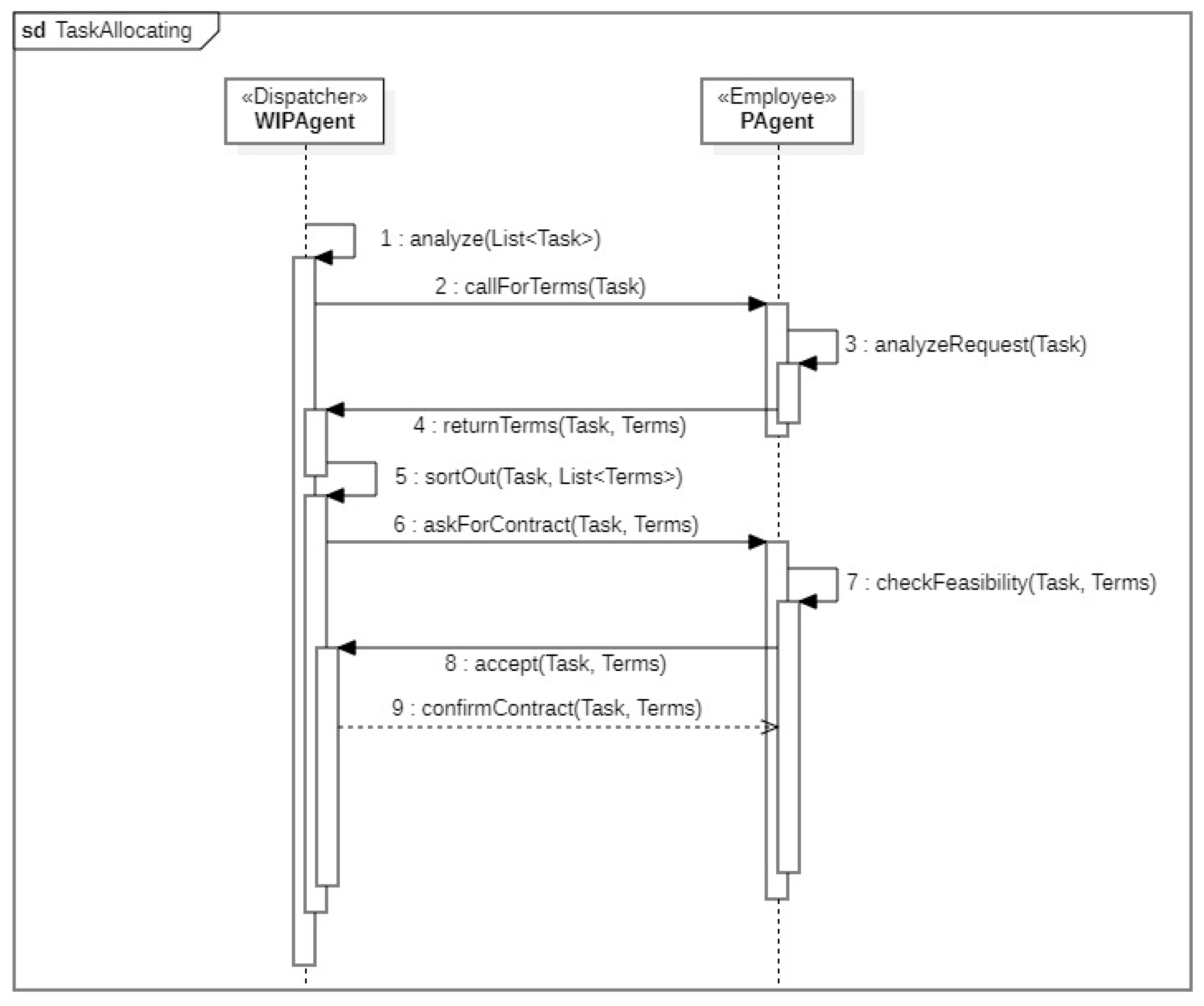

3.2.3. Task-Allocating (Detailed Scheduling/Dispatching)

3.3. Relation to Previous Work

4. Digital-Twin-Based Simulation Testbed

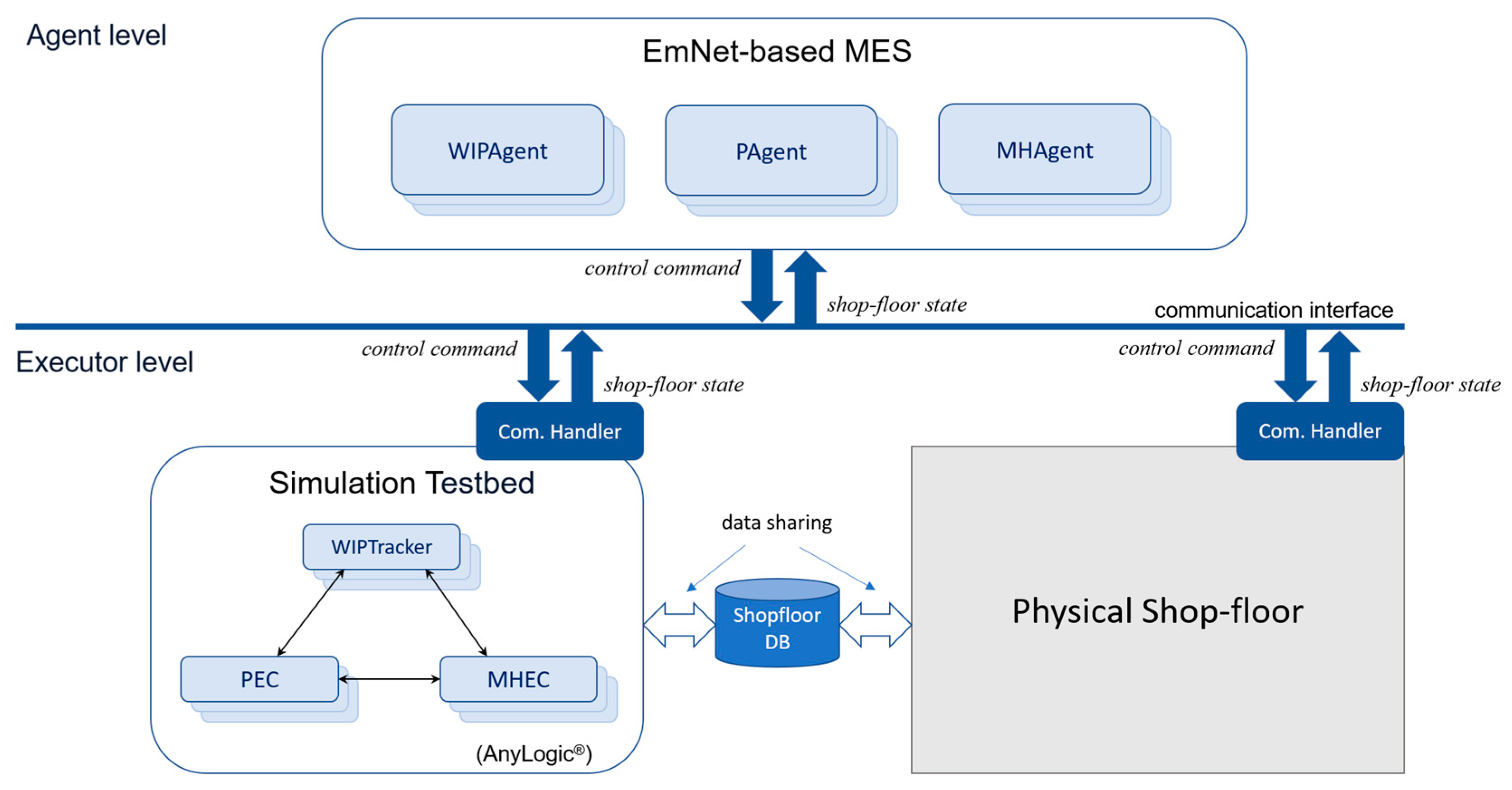

4.1. System Configuration

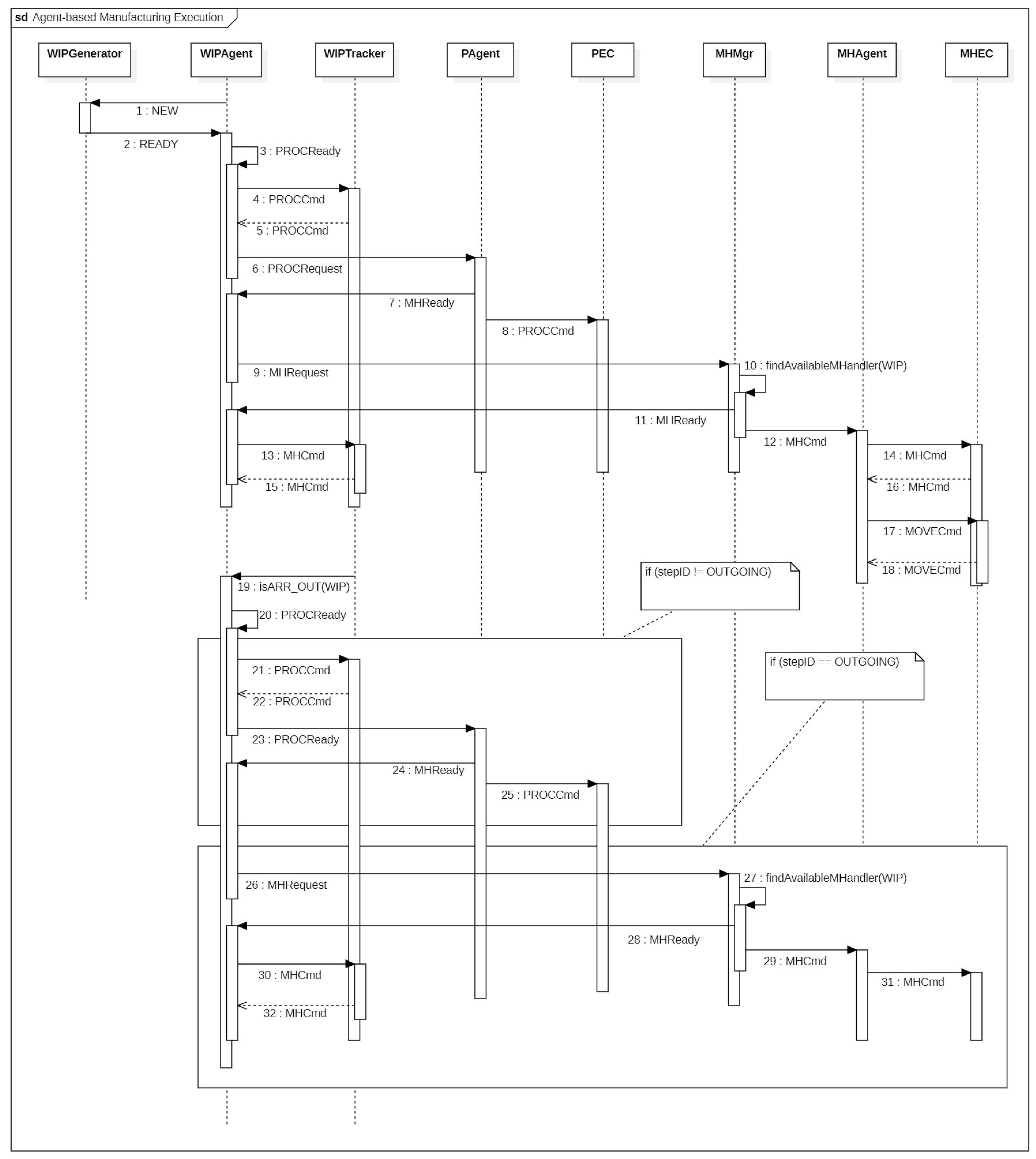

- WIPTracker: It simulates the behavior of WIP on the shop floor and reports tracking information of individual WIPs to their corresponding WIPAgents. Each WIPTracker is linked one-to-one with a WIPAgent in the MES.

- PEC (processing equipment controller): It simulates the behavior of processing workstations and reports status changes of individual workstations to the MES. Each PEC is typically linked one-to-one with a PAgent, receives control commands from the associated PAgent and reports on the execution results. It also interacts with WIPTrackers to induce changes in WIP processing status.

- MHEC (material-handling equipment controller): It simulates the behavior of material-handling equipment and reports status changes to the MES. Each MHEC is typically linked in a one-to-one manner with an MHAgent, receives control commands from the associated MHAgent and reports on the execution results. It specifically handles WIP transportation, thereby inducing changes in WIP status.

4.2. Reference Model of the Physical Shop Floor

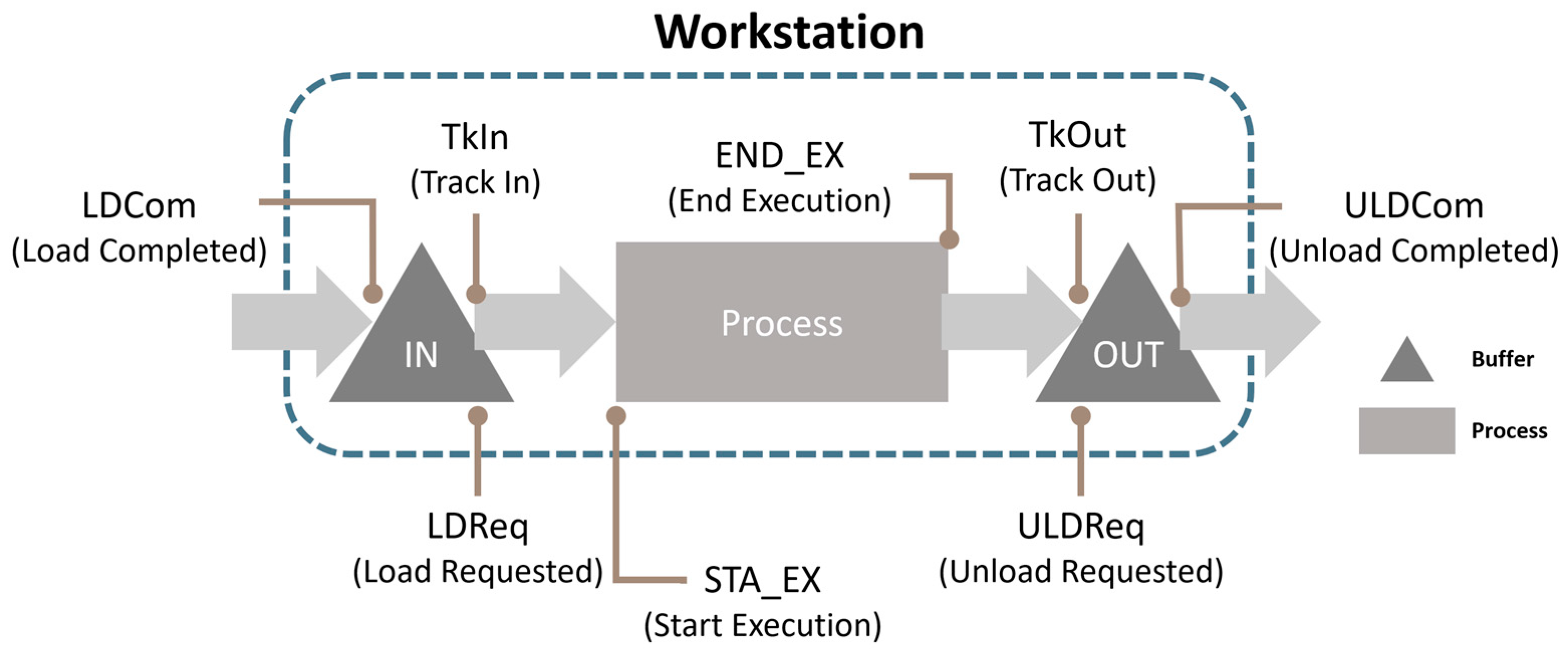

4.2.1. Processing Model

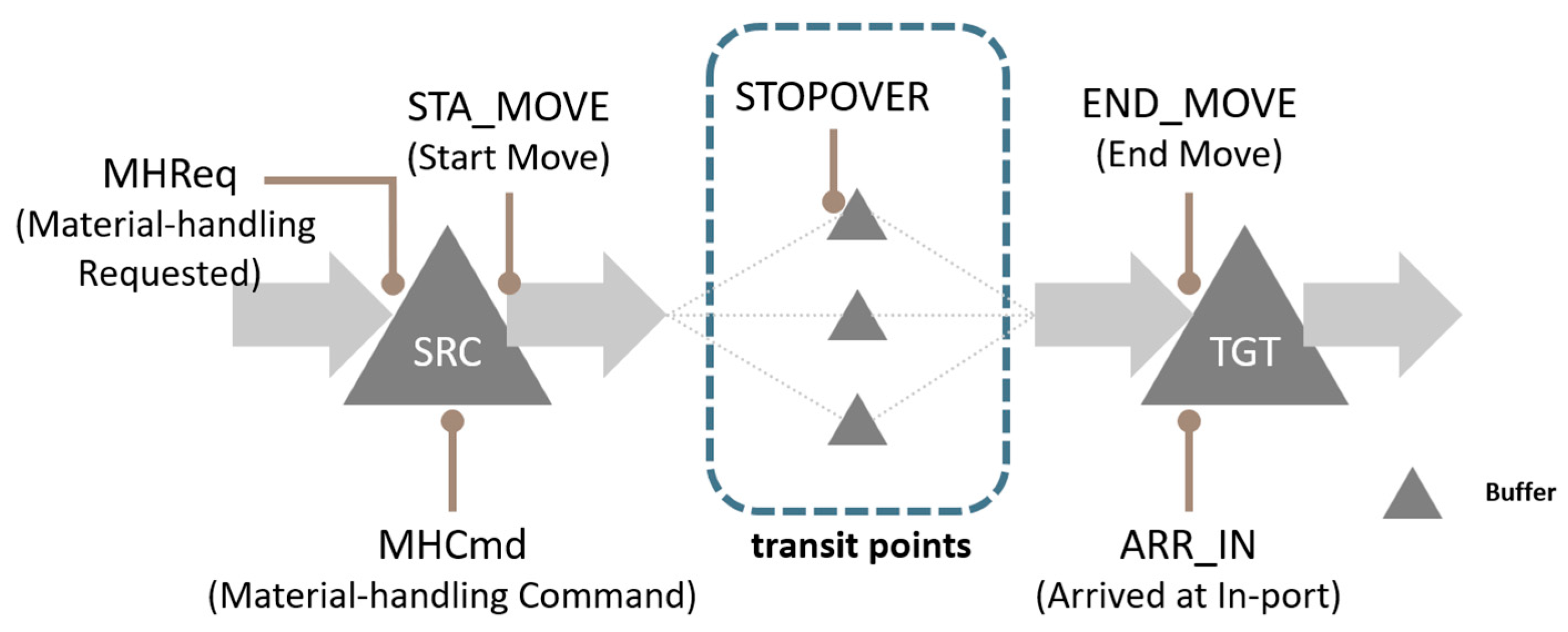

4.2.2. Material-Handling Model

4.3. Prototype Implementation

4.3.1. Executors

4.3.2. Agent−Executor Interaction

5. Simulation Experiments

5.1. Experimental Configuration

5.1.1. Comparative Policies

5.1.2. Experimental Scenario

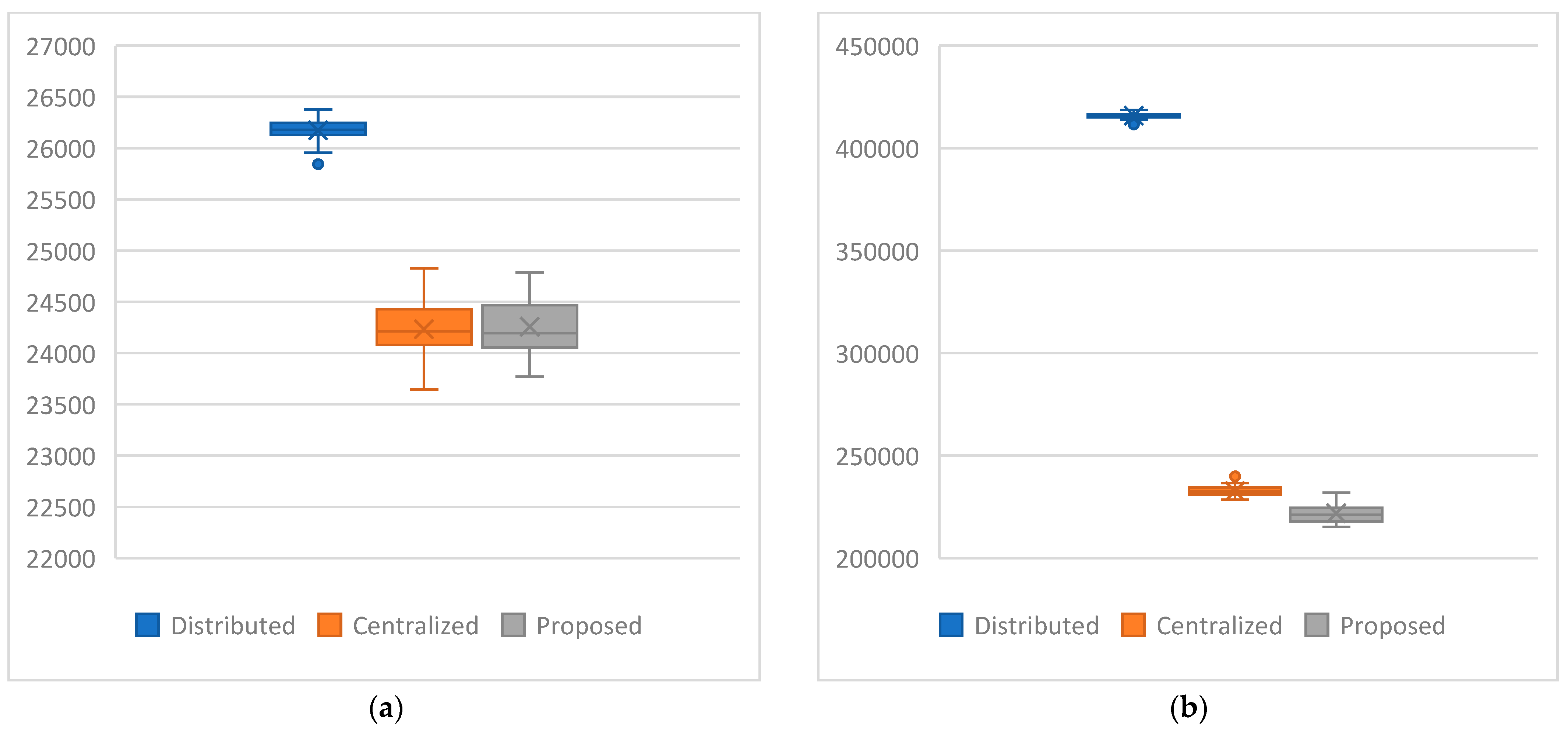

5.2. Results

5.3. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cheng, Y.; Zhang, Y.P.; Tao, F.; Nee, A.Y.C. Cyber–physical integration for moving digital factories forward towards smart manufacturing: A survey. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 97, 1209–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, P.; Wang, H.; Sang, Z.; Zhong, R.Y.; Liu, Y.; Liu, C.; Mubarok, K.; Yu, S.; Xu, X. Smart manufacturing systems for Industry 4.0: Conceptual framework, scenarios, and future perspectives. Front. Mech. Eng. 2018, 13, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.; Qi, Q.; Wang, L.; Nee, A.Y.C. Digital twins and cyber–physical systems toward smart manufacturing and Industry 4.0: Correlation and comparison. Engineering 2019, 5, 653–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.; Bai, K.J. Digital twin-based sustainable intelligent manufacturing: A review. Adv. Manuf. 2021, 9, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valckenaers, P. Perspective on holonic manufacturing systems: PROSA becomes ARTI. Comput. Ind. 2020, 120, 103226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaskó, S.; Skrop, A.; Holczinger, T.; Chován, T.; Abonyi, J. Development of manufacturing execution systems in accordance with Industry 4.0 requirements: A review of standard- and ontology-based methodologies and tools. Comput. Ind. 2020, 123, 103300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zwolińska, B.; Tubis, A.A.; Chamier-Gliszczyński, N.; Kostrzewski, M. Personalization of the MES system to the needs of highly variable production. Sensors 2020, 20, 6484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boccella, A.R.; Centobelli, P.; Cerchione, R.; Murino, T.; Riedel, R. Evaluating centralized and heterarchical control of smart manufacturing systems in the era of Industry 4.0. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Hao, Q.; Yoon, H.J.; Norrie, D.H. Applications of agent-based systems in intelligent manufacturing: An updated review. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2006, 20, 415–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, P.; Karnouskos, S.; Ribeiro, L.; Lee, J.; Strasser, T.; Colombo, A.W. Smart agents in industrial cyber–physical systems. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 1086–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Li, D.; Wang, S.; Dong, Z. CASOA: An architecture for agent-based manufacturing system in the context of Industry 4.0. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 12746–12754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalenko, I.; Tilbury, D.; Barton, K. The model-based product agent: A control-oriented architecture for intelligent products in multi-agent manufacturing systems. Control Eng. Pract. 2019, 86, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, P.; Demongodin, I.; Castagna, P. A holonic approach for manufacturing execution system design: An industrial application. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2008, 21, 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, J.; Huang, G.Q.; Li, Z. Event-driven multi-agent ubiquitous manufacturing execution platform for shop floor work-in-progress management. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2013, 51, 1168–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monostori, L.; Valckenaers, P.; Dolgui, A.; Panetto, H.; Brdys, M.; Csáji, B.C. Cooperative control in production and logistics. Annu. Rev. Control 2015, 39, 12–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cupek, R.; Ziebinski, A.; Huczala, L.; Erdogan, H. Agent-based manufacturing execution systems for short-series production scheduling. Comput. Ind. 2016, 82, 245–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vyskočil, J.; Douda, P.; Novák, P.; Wally, B. A digital twin-based distributed manufacturing execution system for Industry 4.0 with AI-powered on-the-fly replanning capabilities. Sustainability 2023, 15, 6251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, P. Agent-based distributed manufacturing control: A state-of-the-art survey. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2009, 22, 979–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novas, J.M.; Van Belle, J.; Saint Germain, B.; Valckenaers, P. A collaborative framework between a scheduling system and a holonic manufacturing execution system. In Service Orientation in Holonic and Multi Agent Manufacturing and Robotics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Pulikottil, T.; Estrada-Jimenez, L.A.; Rehman, H.U.; Mo, F.; Nikghadam Hojjati, S.; Barata, J. Agent-based manufacturing—Review and expert evaluation. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 127, 2151–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa, J.; Leitão, P.; Adam, E.; Trentesaux, D. Dynamic self-organization in holonic multi-agent manufacturing systems: The ADACOR evolution. Comput. Ind. 2015, 66, 99–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitão, P.; Restivo, F. ADACOR: A holonic architecture for agile and adaptive manufacturing control. Comput. Ind. 2006, 57, 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panetto, H.; Molina, A. Enterprise integration and interoperability in manufacturing systems: Trends and issues. Comput. Ind. 2008, 59, 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iarovyi, S.; Mohammed, W.M.; Lobov, A.; Ferrer, B.R.; Lastra, J.L.M. Cyber–physical systems for open-knowledge-driven manufacturing execution systems. Proc. IEEE 2016, 104, 1142–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M. Employment contract-based self-organizing mechanism for production resources. J. Korean Inst. Ind. Eng. 2020, 46, 282–295. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, M. Development of collaboration model for data space-based open collaboration platform in continuous process industries. Sustainability 2025, 17, 126. [Google Scholar]

- Rolón, M.; Martínez, E. Agent-based modeling and simulation of an autonomic manufacturing execution system. Comput. Ind. 2012, 63, 53–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Brussel, H.; Wyns, J.; Valckenaers, P.; Bongaerts, L.; Peeters, P. Reference architecture for holonic manufacturing systems: PROSA. Comput. Ind. 1998, 37, 255–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiceanu, R.F.; Chen, F.F. Development and applications of holonic manufacturing systems: A survey. J. Intell. Manuf. 2006, 17, 111–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valckenaers, P.; Van Brussel, H.; Verstraete, P.; Saint Germain, B. Schedule execution in autonomic manufacturing execution systems. J. Manuf. Syst. 2007, 26, 75–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnecke, H.-J. The Fractal Company: A Revolution in Corporate Culture; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ryu, K.; Jung, M. Agent-based fractal architecture and modelling for developing distributed manufacturing systems. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2003, 41, 4233–4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Mun, J.; Lee, K.; Jung, M. r-FrMS: A relation-driven fractal organisation for distributed manufacturing systems. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2009, 47, 1791–1814. [Google Scholar]

- Ueda, K. A concept for bionic manufacturing systems based on DNA-type information. In Human Aspects in Computer Integrated Manufacturing; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1992; pp. 853–863. [Google Scholar]

- Tharumarajah, A. Comparison of the bionic, fractal and holonic manufacturing system concepts. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 1996, 9, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.G. The contract net protocol: High-level communication and control in a distributed problem solver. IEEE Trans. Comput. 1980, 29, 1104–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, A.D. A survey of factory control algorithms that can be implemented in a multi-agent heterarchy: Dispatching, scheduling, and pull. J. Manuf. Syst. 1998, 17, 297–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, K.; Yücesan, E.; Jung, M. Dynamic restructuring process for self-reconfiguration in the fractal manufacturing system. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2006, 44, 3105–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parunak, H.V.D. Industrial and practical applications of distributed artificial intelligence. In Multiagent Systems: A Modern Approach to Distributed Artificial Intelligence; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1999; pp. 377–421. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, M.S.; Ali, M. A multi-agent-based dynamic scheduling of flexible manufacturing systems. Glob. J. Flex. Syst. Manag. 2019, 20, 267–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, T.; Aiyama, Y.; Sugi, M.; Ota, J. Holonic assembly system with Plug and Produce. Comput. Ind. 2001, 46, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, M.; Ryu, K. Agent-based resource model for relation-driven fractal organization. ICIC Expr. Lett. 2013, 7, 1539–1544. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, M. Employment contract-based management model of production resources on relation-driven fractal organization. J. Korean Inst. Ind. Eng. 2013, 39, 278–289. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel, L.; Lycklama, D. Design Principles for Data Spaces. 2021. Available online: https://design-principles-for-data-spaces.org/ (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Gaia-X European Association for Data and Cloud AISBL. GAIA-X Architecture Document, 22.04 Release. Available online: https://gaia-x.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Gaia-x-Architecture-Document-22.04-Release.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2024).

- Schöppenthau, F.; Patzer, F.; Schnebel, B.; Watson, K.; Baryschnikov, N.; Obst, B.; Chauhan, Y.; Kaever, D.; Usländer, T.; Kulkarni, P. Building a digital manufacturing as a service ecosystem for Catena-X. Sensors 2023, 23, 7396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usländer, T.; Baumann, M.; Boschert, S.; Rosen, R.; Sauer, O.; Stojanovic, L.; Wehrstedt, J.C. Symbiotic evolution of digital twin systems and dataspaces. Automation 2022, 3, 378–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MESA International. History of the MESA Models. Available online: https://mesa.org/topics-resources/mesa-model/history-of-the-mesa-models/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 20 November 2025).

- International Society of Automation (ISA). ANSI/ISA-95.00.03-2013 (IEC 62264-3 Modified), Enterprise-Control System Integration—Part 3: Activity Models of Manufacturing Operations Management. Available online: https://www.isa.org/products/ansi-isa-95-00-03-2013-enterprise-control-system-i (accessed on 20 November 2025).

| Unified Category | ISA-95 Function(s) | MESA Function(s) | Summary of Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Production Scheduling | Detailed Production Scheduling | Operations/ Detailed Scheduling | Translating high-level production plans into executable schedules by reflecting real-time resource constraints. |

| Dispatching and Execution Control | Production Dispatching | Dispatching Production Units; Process Management | Coordinating the real-time release, sequencing, and monitoring of work orders and process operations. |

| Resource and Labor Management | Resource Management | Resource Allocation and Status; Labor Management | Managing the availability, capability, and utilization of resources such as equipment, tools, materials, and personnel. |

| Quality and Compliance Management | Quality Operations Management | Quality Management; Document Control | Maintaining quality and compliance through inspection, data collection, and document management. |

| Maintenance and Asset Management | Maintenance Operations Management | Maintenance Management | Managing maintenance schedules (preventive/corrective) and monitoring asset health to maximize system availability. |

| Material/WIP Tracking and Genealogy | Tracking and Genealogy; Inventory Operations Management | Product Tracking and Genealogy | Tracking materials, components, and products end-to-end to ensure WIP visibility and maintain product genealogy. |

| Data Collection and Performance Analysis | Data Collection; Performance Analysis | Data Collection/Acquisition; Performance Analysis | Acquiring real-time data to calculate KPIs (e.g., OEE, yield) and enabling data-driven continuous improvement. |

| Stakeholder | Function | Description |

|---|---|---|

| <<PlanMgr>> WIPAgent | assign (Order) | Assigning a production order to an AIR-unit responsible for acting as the employer. |

| <<Employer>> PAgent | specifyRequiredMfgCap () | Specifying the list of required manufacturing capabilities. |

| searchForMfgCap (Capability) | Searching for candidates capable of providing the given capability. | |

| sortOut (Capability, List <Employee>) | Sorting out candidates for the employee to provide the given capability. | |

| callForTerms (Job) | Calling for contract terms for the given job. | |

| sortOut (Job, List <Terms>) | Sorting the list of the terms provided by the candidate employees. | |

| askForContract (Job, Terms) | Requesting a contract for the given job. | |

| confirmContract (Job, Terms) | Confirming a contract for the job according to the terms presented. | |

| reportPlan (Order, List <Job>) | Reporting on the list of jobs associated with the production order. | |

| <<Candidate>> PAgent | registerMfgCap (List <Capability>) | Registering the list of manufacturing capabilities. |

| analyzeRequest (Job) | Analyzing the requested job and specifying the contract terms for the job. | |

| returnTerms (Job, Terms) | Returning the contract terms for the job. | |

| checkFeasibility (Job, Terms) | Checking the feasibility of the terms for the job. | |

| accept (Job, Terms) | Accepting the terms for the job. | |

| deny (Job, Terms) | Denying the terms for the job. | |

| MarketPlace | returnListOf (Capability, List <Employee>) | Returning the list of candidate employees capable of providing the given manufacturing capability. |

| Stakeholder | Function | Description |

|---|---|---|

| <<Dispatcher>> WIPAgent | analyze (List <Task>) | Analyzing the tasks associated with a job and identifying the employees assigned to it. |

| callForTerms (Task) | Calling for terms associated with the given task. | |

| sortOut (Task, List <Terms>) | Evaluating a list of terms provided by its employees and selecting the task with the most favorable terms. | |

| askForContracts (Task, Terms) | Asking for a task contract under the specified terms. | |

| confirmContract (Task, Terms) | Confirming the task allocation under the given terms. | |

| <<Employee>> PAgent | analyzeRequest (Task) | Analyzing a given task and generates its associated terms. |

| returnTerms (Task, Terms) | Returning a task along with its associated terms. | |

| checkFeasibility (Task, Terms) | Determining the feasibility of executing the task under the provided terms. | |

| accept (Task, Terms) | Accepting the proposed task in accordance with the given terms. | |

| deny (Task, Terms) | Denying the proposed task in accordance with the given terms. |

| Event | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| Triggering condition | TkIn or WakeUp occurs, provided that the inBuffer has sufficient loading capacity:

| |

| Action | Find a next WIP:

| |

| LDCom | Triggering condition | A WIP arrives at the inBuffer once either the WIP is determined by an LDReq or its destination is determined by a ULDReq. |

| Action | TkIn is triggered, provided that the process start conditions are fulfilled. | |

| TkIn | Triggering condition | LDCom occurs, provided that the process start conditions are fulfilled.

|

| Action | The WIP is removed from the inBuffer. STA_EX is triggered. | |

| STA_EX | Triggering condition | TkIn occurs. |

| Action | Processing is initiated. END_EX is triggered after the processing time. | |

| END_EX | Triggering condition | After STA_EX occurs and the processing time has elapsed. |

| Action | Processing is completed. TkOut is triggered. | |

| TkOut | Triggering condition | END_EX occurs. |

| Action | ULDReq is triggered, provided that the transfer conditions are met.

| |

| ULDReq | Triggering condition | TkOut or WakeUp occurs, provided that the transfer conditions are met.

|

| Action | Find the next destination of the WIP.

| |

| ULDCom | Triggering condition | A WIP leaves the outBuffer once either the WIP is determined by an LDReq or its destination is determined by a ULDReq. |

| Action | The transfer process is initiated. | |

| WakeUp | Triggering condition | The event periodically Periodically occurs at a predefined frequency to check the trigger conditions of each event type (e.g., LDReq, ULDReq). |

| Action | LDReq and ULDReq are triggered, provided that their respective conditions are met. | |

| Event | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| MHReq | Triggering condition | Triggered by either (1) the selection of the transport WIP following LDReq, (2) the assignment of its destination following ULDReq, or (3) WakeUp. |

| Action | Find a material-handling equipment to transport the WIP from the source to the target.

| |

| MHCmd | Triggering condition | Triggered by MHReq, upon the assignment of a qualified material handler. |

| Action | The transit of the material handler to the source location is initiated. | |

| STA_MOVE | Triggering condition | After the MHCmd is issued, the material handler arrives at the source location, and the WIP becomes ready for transport. |

| Action | The WIP transfer process is initiated. | |

| STOPOVER | Triggering condition | After the MHCmd is issued, the WIP arrives at a transit point. |

| Action | The next destination is identified, and the transfer process is resumed. | |

| END_MOVE | Triggering condition | The WIP arrives at a target location. |

| Action | The WIP transfer process is terminated. ARR_IN is triggered. | |

| ARR_IN | Triggering condition | END_MOVE is triggered. |

| Action | If the arrival location is a workstation, LDCom is triggered; if it is a buffer, ULDReq is triggered. | |

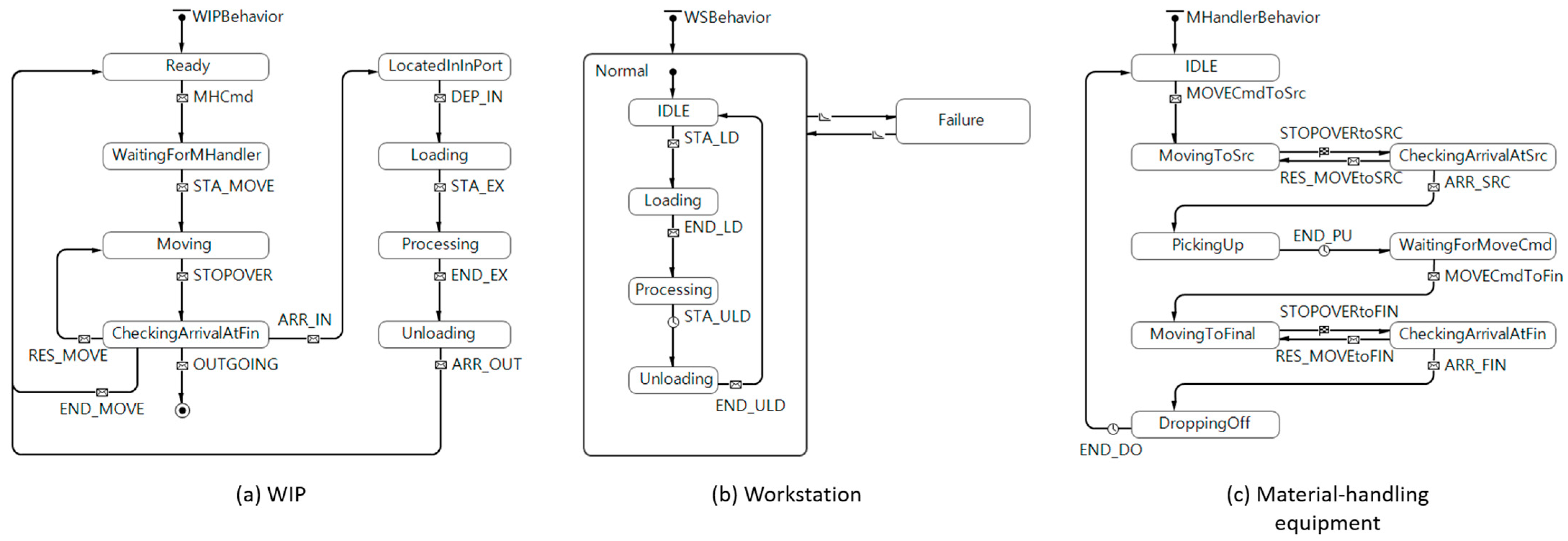

| Executor | State | Description |

|---|---|---|

| WIPTracker | Ready | A WIP is ready for transport. |

| WaitingForMHandler | The WIP is waiting for the material-handling equipment to arrive. | |

| Moving | The WIP is on the move. | |

| CheckingArrivalAtFin | Check whether the WIP has reached its target workstation. | |

| LocatedInInPort | The WIP is located at the input port of its target workstation. | |

| Loading | The WIP is being loaded onto the workstation. | |

| Processing | The WIP is under processing at the workstation. | |

| Unloading | The WIP is being unloaded from the workstation. | |

| PEC | IDLE | The workstation status: idle. |

| Loading | The workstation is loading the WIP. | |

| Processing | The workstation is processing the WIP. | |

| Unloading | The workstation is unloading the WIP. | |

| Failure | The workstation status: failed. | |

| MHEC | IDLE | The material-handling equipment status: idle |

| MovingToSrc | The material-handling equipment is moving toward the source workstation where the WIP is located. | |

| CheckingArrivalAtSrc | Check if the material-handling equipment has arrived at the source workstation. | |

| PickingUp | The material-handling equipment is retrieving the WIP. | |

| WaitingForMoveCmd | The material-handling equipment is awaiting the move command. | |

| MovingToFin | The material-handling equipment is moving toward the target workstation of the WIP. | |

| CheckingArrivalAtFin | Check if the material-handling equipment has arrived at the target workstation. | |

| DroppingOff | The material-handling equipment is dropping off WIP. |

| Executor | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| WIPTracker | MHCmd | A material-handling command is received from WIPAgent. |

| STA_MOVE | A WIP movement is initiated. | |

| STOPOVER | The WIP arrives at an intermediate station. | |

| RES_MOVE | The WIP movement resumes. | |

| END_MOVE | The WIP movement is completed. | |

| ARR_IN | The WIP arrives at the input port of a workstation. | |

| DEP_IN | The WIP has left the input port of a workstation. | |

| STA_EX | A WIP processing is initiated. | |

| END_EX | The WIP processing is completed. | |

| ARR_OUT | The WIP arrives at the output port of a workstation. | |

| OUTGOING | The WIP finishes processing and exits the system. | |

| PEC | STA_LD | A WIP loading to the workstation is initiated. |

| END_LD | The WIP loading to the workstation is completed. | |

| STA_ULD | A WIP unloading from the workstation is initiated. | |

| END_ULD | The WIP unloading from the workstation is completed. | |

| MHEC | MOVECmdToSRC | A moving command to source station is received from MHAgent. |

| STOPOVERtoSRC | The material-handling equipment arrives at the intermediate station during transit to the source station. | |

| RES_MOVEtoSRC | The material-handling equipment resumes transit to the source station. | |

| ARR_SRC | The material-handling equipment arrives at the source station. | |

| END_PU | The WIP pick-up is completed. | |

| MOVECmdToFIN | A move command to the target station is received from MHAgent. | |

| STOPOVERtoFIN | The material-handling equipment arrives at the intermediate station during the transit to the target station. | |

| RES_MOVEtoFIN | The material-handling equipment resumes transit to the target station. | |

| ARR_FIN | The material-handling equipment arrives at the target station. | |

| END_DO | The WIP drop-off is completed. |

| Type | Sender Type | Receiver Type | Sender | Receiver | Performative | Event | Msg. Contents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WIP Event | Agent | Agent | WIPAgent | WIPGenerator | Request | NEW | [wipID 1 |productID 2 |stepID 3 |curLocID 4] |

| WIPAgent | Inform | PROCReady | [wipID|stepID|tgtID 5] | ||||

| PAgent | Inform | PROCRequest | [wipID|stepID|tgtID] | ||||

| MHMgr | Inform | MHRequest | [wipID|srcID 6 |tgtID|handlerID 7] | ||||

| WIPGenerator | WIPAgent | Inform | READY | [wipID|productID|stepID|curLocID] | |||

| Executor | WIPAgent | WIPTracker | Request | PROCCmd | [wipID|stepID|tgtID] | ||

| Request | MHCmd | [wipID|srcID|tgtID|handlerID] | |||||

| Executor | Agent | WIPTracker | WIPAgent | Inform | PROCCmd | [wipID|stepID|tgtID] | |

| Inform | MHCmd | [wipID|srcID|tgtID|handlerID] | |||||

| Inform | STA_MOVE | [wipID|srcID|tgtID|handlerID|fromID 8] | |||||

| Inform | STOPOVER | [wipID|srcID|tgtID|handlerID|toID 9] | |||||

| Inform | RES_MOVE | [wipID|srcID|tgtID|handlerID|fromID] | |||||

| Inform | END_MOVE | [wipID|srcID|tgtID|handlerID|toID] | |||||

| Inform | ARR_IN | [wipID|tgtID|portID 10] | |||||

| Inform | DEP_IN | [wipID|tgtID|portID] | |||||

| Inform | STA_EX | [wipID|tgtID] | |||||

| Inform | END_EX | [wipID|tgtID] | |||||

| Inform | ARR_OUT | [wipID|tgtID|portID] | |||||

| Inform | DEP_OUT | [wipID|tgtID|portID] | |||||

| Inform | OUTGOING | [wipID] | |||||

| Processing Event | Agent | Agent | PAgent | WIPAgent | Inform | MHReady | [wipID|stepID|tgtID] |

| Executor | PAgent | PEC | Request | PROCCmd | [wipID|stepID|tgtID] | ||

| Request | RESERVE_PORT | [wipID|tgtID|portID] | |||||

| Request | CANCEL_PORT | [wipID|tgtID|portID] | |||||

| Executor | Agent | PEC | PAgent | Inform | PROCCmd | [wipID|stepID|tgtID] | |

| Inform | STA_LD | [wipID|tgtID|portID] | |||||

| Inform | END_LD | [wipID|tgtID|portID] | |||||

| Inform | STA_EX | [wipID|tgtID] | |||||

| Inform | END_EX | [wipID|tgtID] | |||||

| Inform | STA_ULD | [wipID|tgtID|portID] | |||||

| Inform | END_ULD | [wipID|tgtID|portID] | |||||

| Inform | RESERVE_PORT | [wipID|tgtID|portID] | |||||

| Inform | CANCEL_PORT | [wipID|tgtID|portID] | |||||

| Inform | SEIZE_PORT | [wipID|portID] | |||||

| Inform | RELEASE_PORT | [wipID|portID] | |||||

| Material-handling Event | Agent | Agent | MHMgr | WIPAgent | Inform | MHReady | [wipID|srcID|tgtID|handlerID] |

| MHAgent | Inform | MHCmd | [wipID|srcID|tgtID|handlerID] | ||||

| Executor | MHAgent | MHEC | Request | MHCmd | [wipID|srcID|tgtID|handlerID] | ||

| Request | MOVECmd | [wipID|srcID|tgtID|fromID|toID] | |||||

| Executor | Agent | MHEC | MHAgent | Inform | MHCmd | [wipID|srcID|tgtID|handlerID] | |

| Inform | MOVECmd | [wipID|srcID|tgtID|fromID|toID] | |||||

| Inform | ARRIVE | [wipID|srcID|tgtID|fromID|toID] | |||||

| Inform | PICKUP | [wipID|locID] | |||||

| Inform | DROPOFF | [wipID|locID] | |||||

| Inform | RES_MOVEtoSRC | [wipID|locID] | |||||

| Inform | ARR_SRC | [wipID|locID] | |||||

| Inform | RES_MOVEtoFIN | [wipID|locID] | |||||

| Inform | ARR_FIN | [wipID|locID] | |||||

| Executor Event | Executor | Executor | MHEC | WIPTracker | Inform | STA_MOVE | [wipID|srcID|tgtID|handlerID|fromID] |

| Inform | STOPOVER | [wipID|srcID|tgtID|handlerID|toID] | |||||

| Inform | RES_MOVE | [wipID|srcID|tgtID|handlerID|toID] | |||||

| Inform | END_MOVE | [wipID|srcID|tgtID|handlerID|toID] | |||||

| PEC | WSPort | Request | RESERVED | [wipID|tgtID|portID] | |||

| Request | CANCELED | [wipID|tgtID|portID] | |||||

| Request | SEIZED | [wipID|portID] | |||||

| Request | RELEASED | [wipID|portID] | |||||

| MHEC | WSPort | Inform | SEIZED | [wipID|portID] | |||

| Inform | RELEASED | [wipID|portID] | |||||

| WSPort | PEC | Inform | SEIZE_PORT | [wipID|portID] | |||

| Inform | RELEASE_PORT | [wipID|portID] | |||||

| Inform | STA_LD | [wipID|tgtID|portID] | |||||

| PEC | WIPTracker | Inform | ARR_IN | [wipID|tgtID|portID] | |||

| Inform | DEP_IN | [wipID|tgtID|portID] | |||||

| Inform | STA_EX | [wipID|tgtID] | |||||

| Inform | END_EX | [wipID|tgtID] | |||||

| Inform | ARR_OUT | [wipID|tgtID|portID] | |||||

| Inform | DEP_OUT | [wipID|tgtID|portID] |

| Mean | Greedy (Distributed) | Centralized | Proposed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tardiness (95% CI) | 1549.54 10.39 | 154.68 8.59 | 1419.51 22.91 |

| Tardiness rate (95% CI) | 88.24% 0.28 | 50.51% 1.22 | 76.01% 0.62 |

| Number of batches | 100.00 | 44.27 | 44.57 |

| Number of setups | 927.00 | 416.60 | 188.90 |

| Number of messages | 0.00 | 0.00 | 500.00 |

| Mean | Greedy (Distributed) | Centralized | Proposed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tardiness (95% CI) | 37.61 | 81.13 | 95.04 |

| Tardiness rate (95% CI) | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.09 |

| Number of batches | 1000.00 | 924.13 | 921.77 |

| Number of setups | 9445.00 | 8919.67 | 9093.67 |

| Number of messages | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5000.00 |

| Mean | Greedy (Distributed) | Centralized | Proposed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tardiness (95% CI) | 483.76 | 937.56 | 1706.45 |

| Tardiness rate (95% CI) | 0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 |

| Number of batches | 1000.00 | 583.00 | 585.83 |

| Number of setups | 14,512.33 | 8376.50 | 359.67 |

| Number of messages | 0.00 | 0.00 | 40,387.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shin, M. Agent-Based Decentralized Manufacturing Execution System via Employment Network Collaboration. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010386

Shin M. Agent-Based Decentralized Manufacturing Execution System via Employment Network Collaboration. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):386. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010386

Chicago/Turabian StyleShin, Moonsoo. 2026. "Agent-Based Decentralized Manufacturing Execution System via Employment Network Collaboration" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010386

APA StyleShin, M. (2026). Agent-Based Decentralized Manufacturing Execution System via Employment Network Collaboration. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 386. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010386