The Application of Ground-Penetrating Radar Inversion in the Determination of Soil Moisture Content in Reclaimed Coal Mine Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

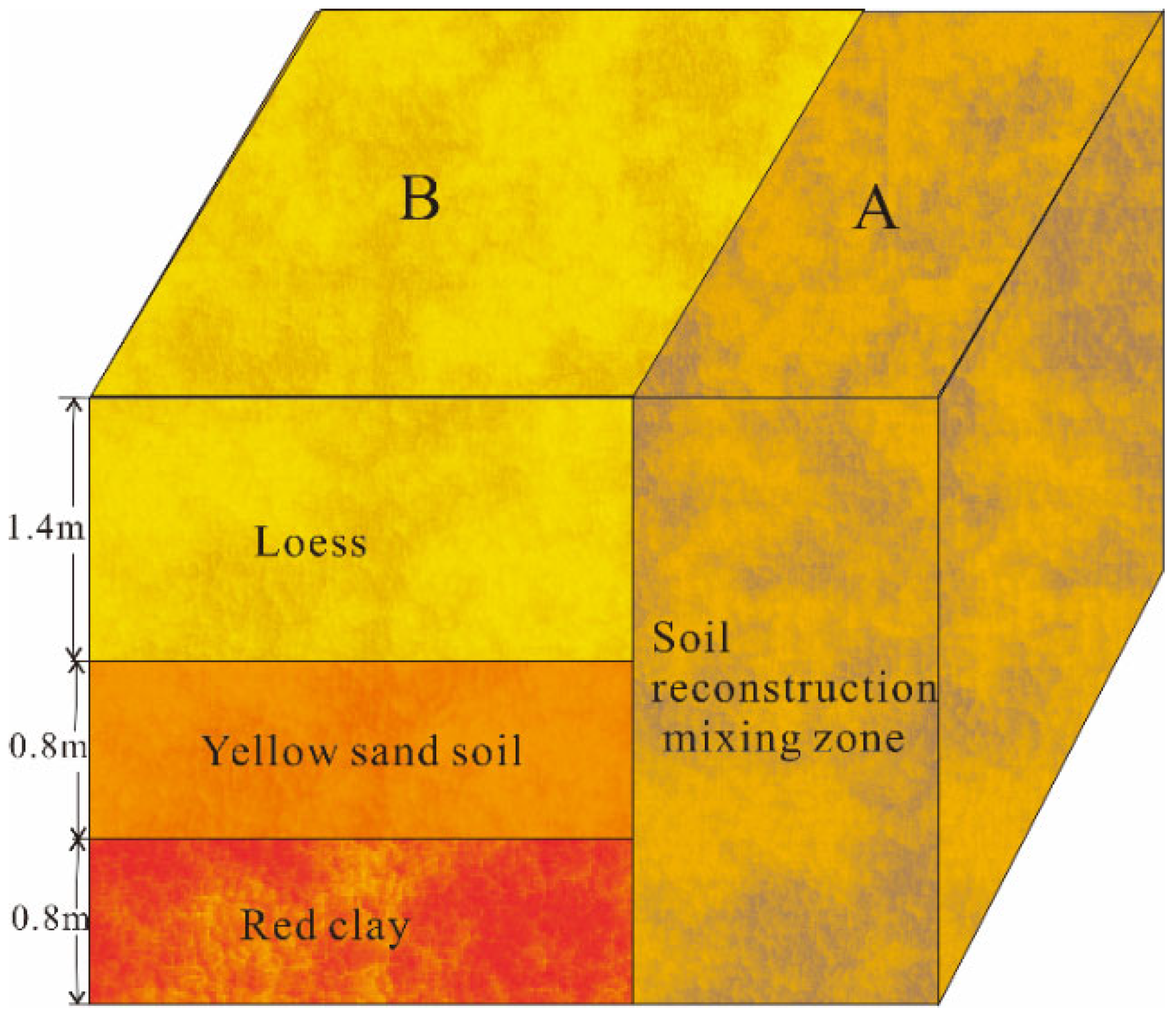

2.1. Experimental Site Overview

2.2. ARMA Method Power Spectrum Principle

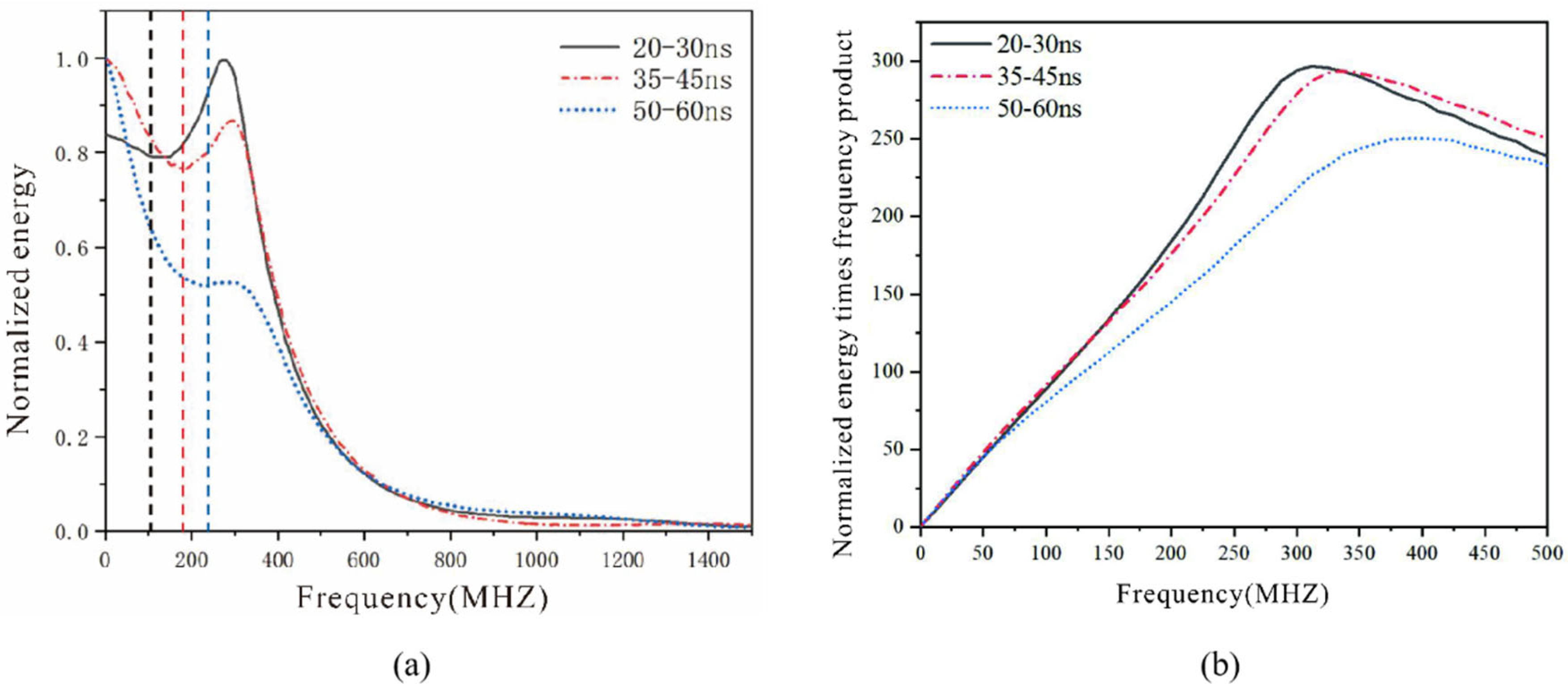

2.3. Feasibility Analysis

2.4. Principle of Drying Method

3. Results

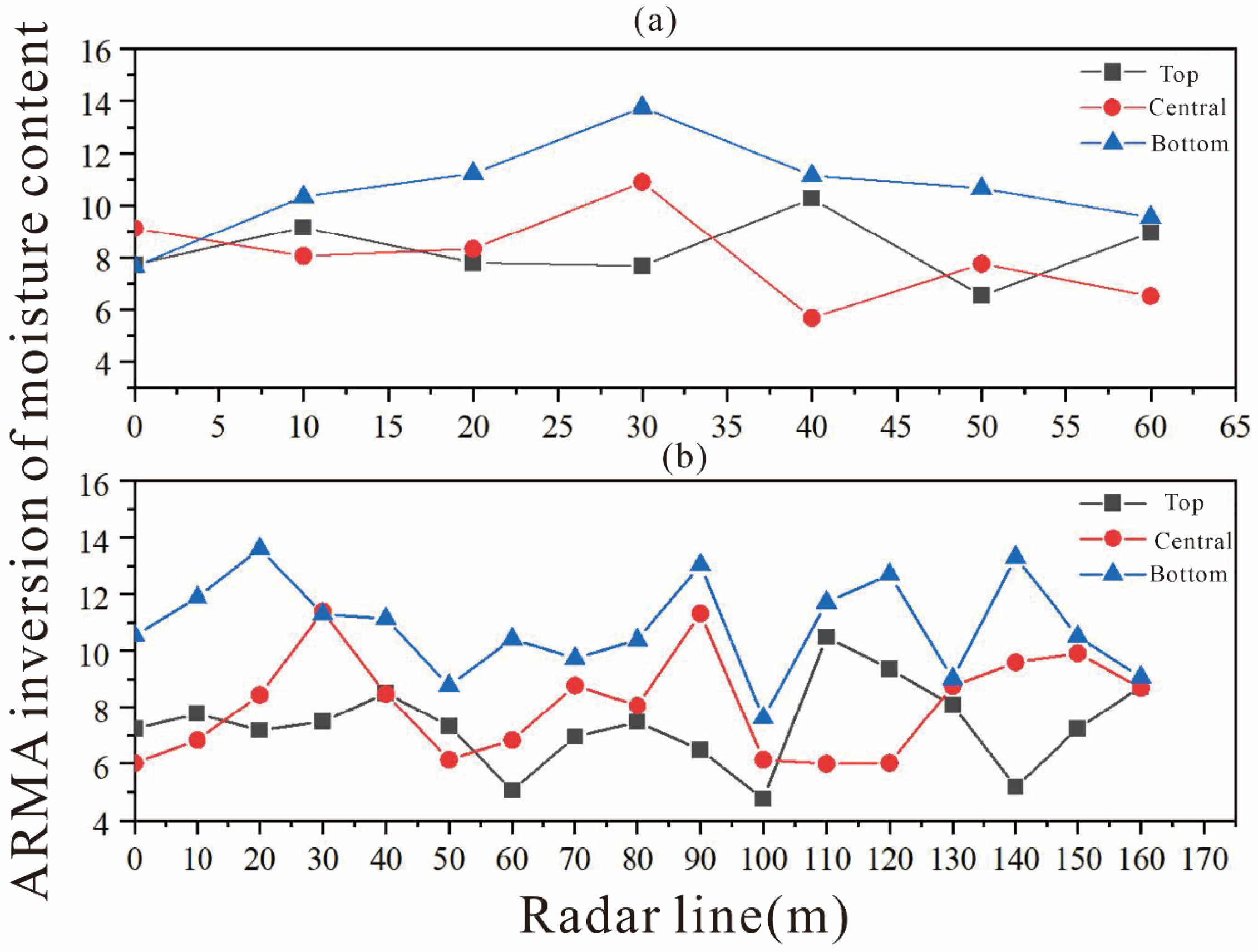

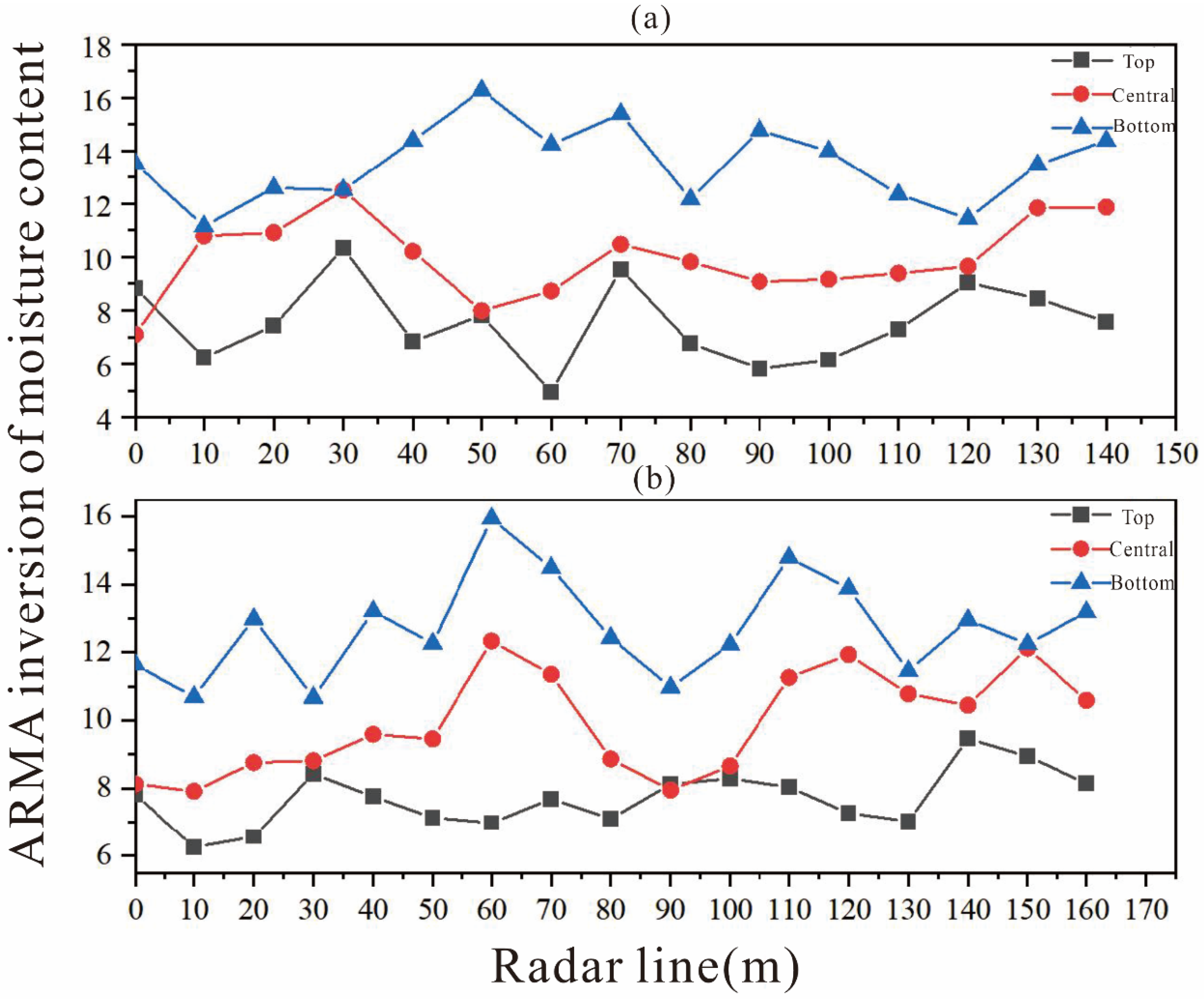

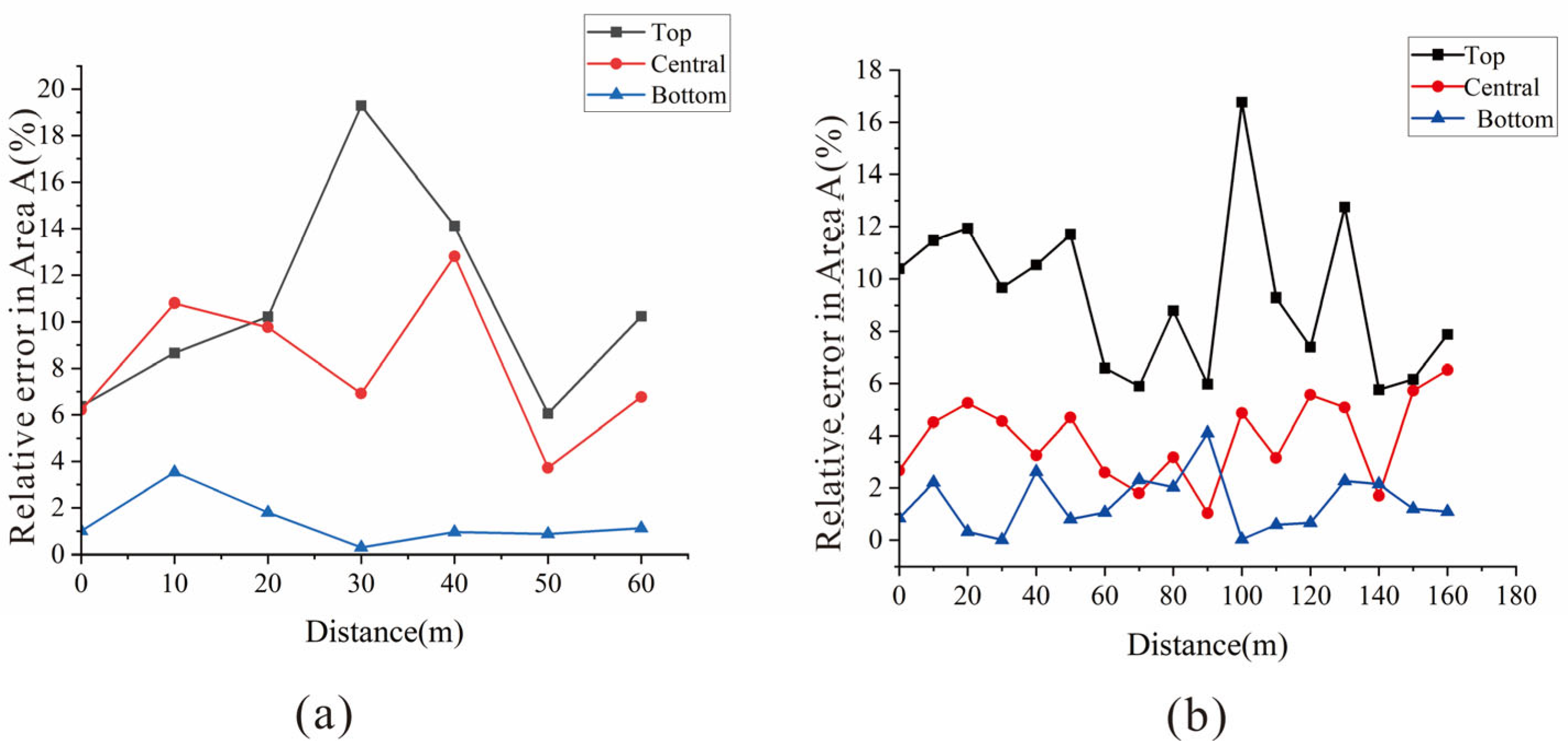

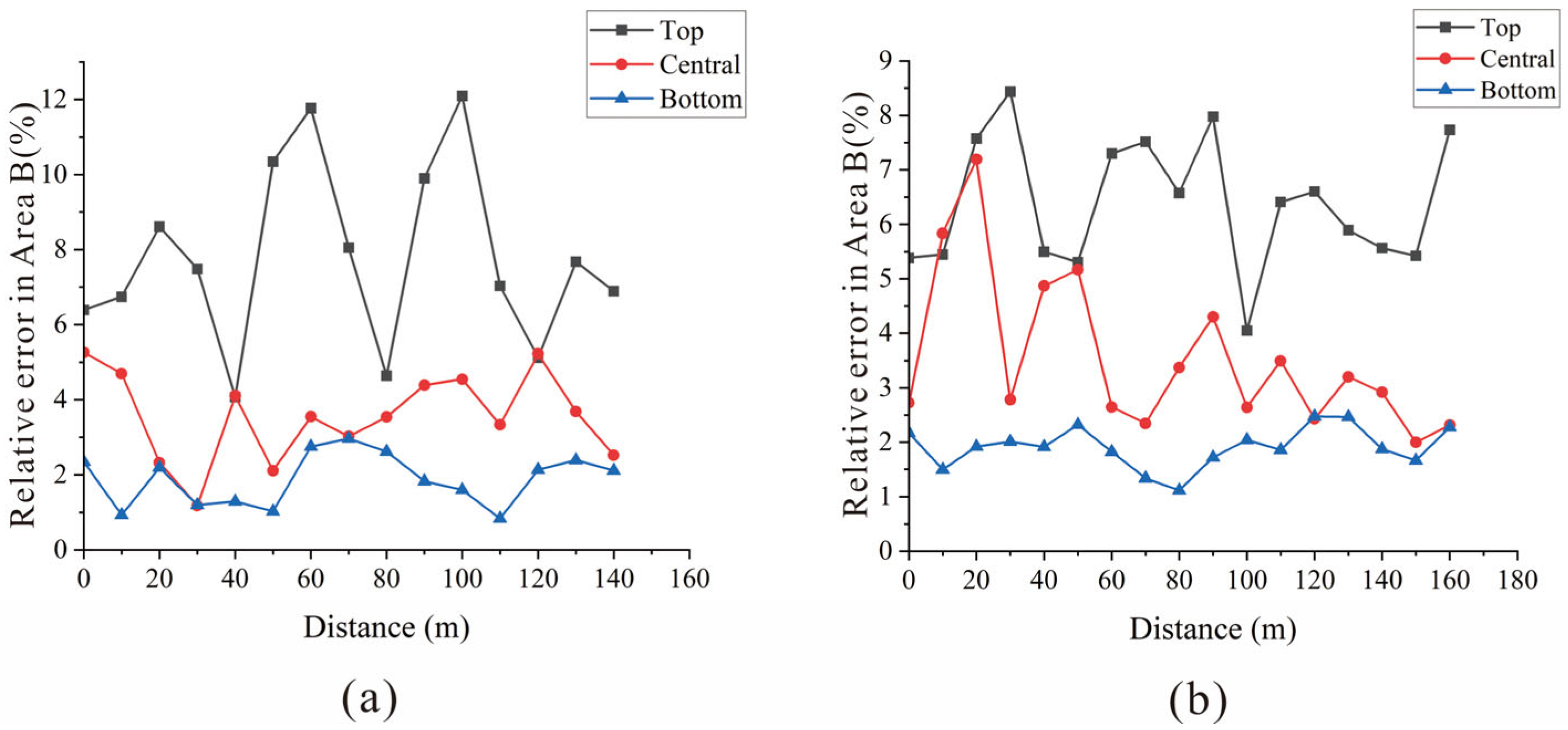

3.1. ARMA Method to Invert Moisture Content

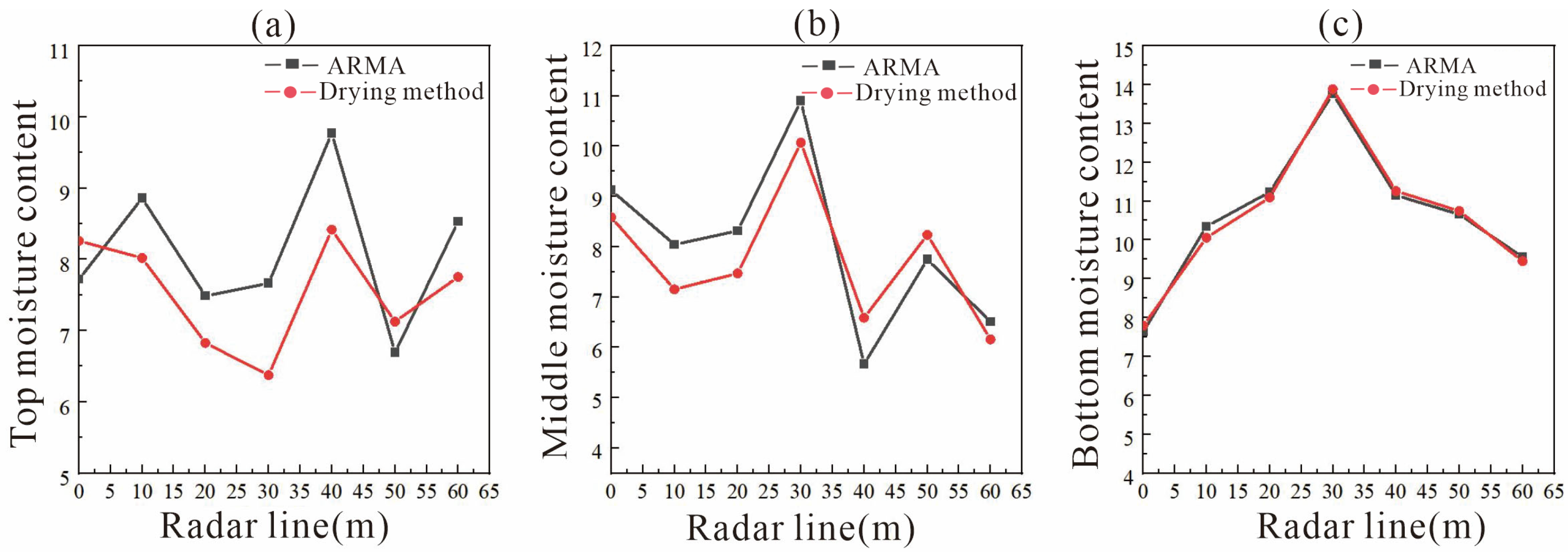

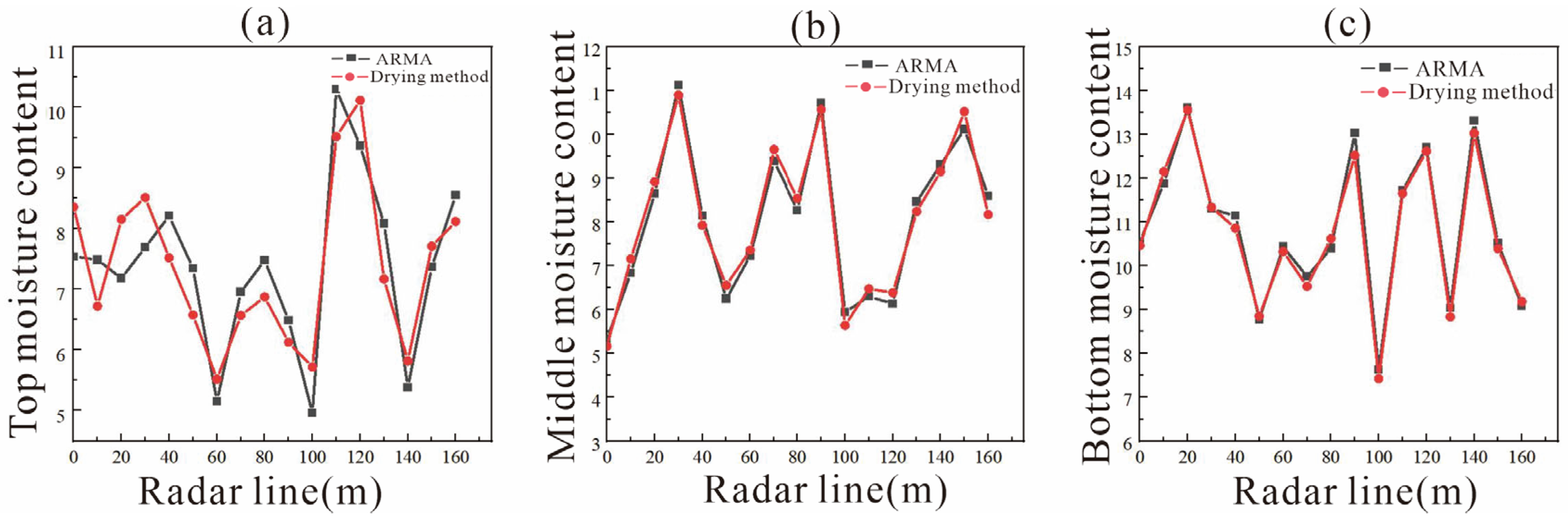

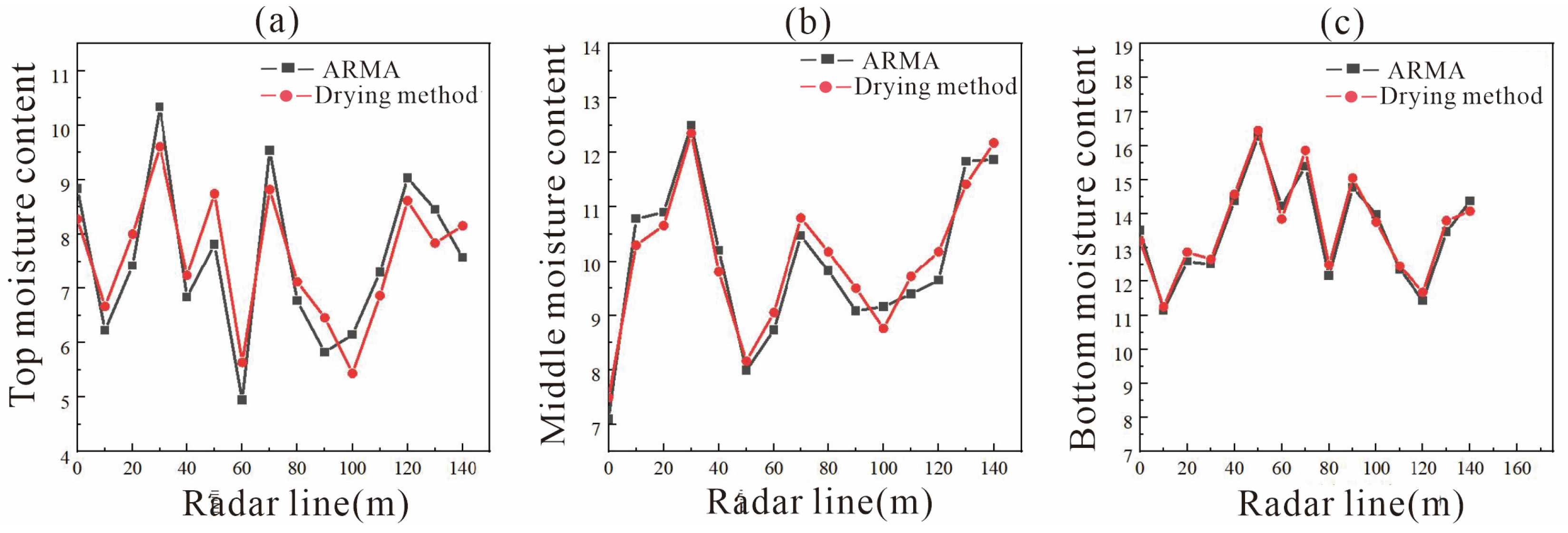

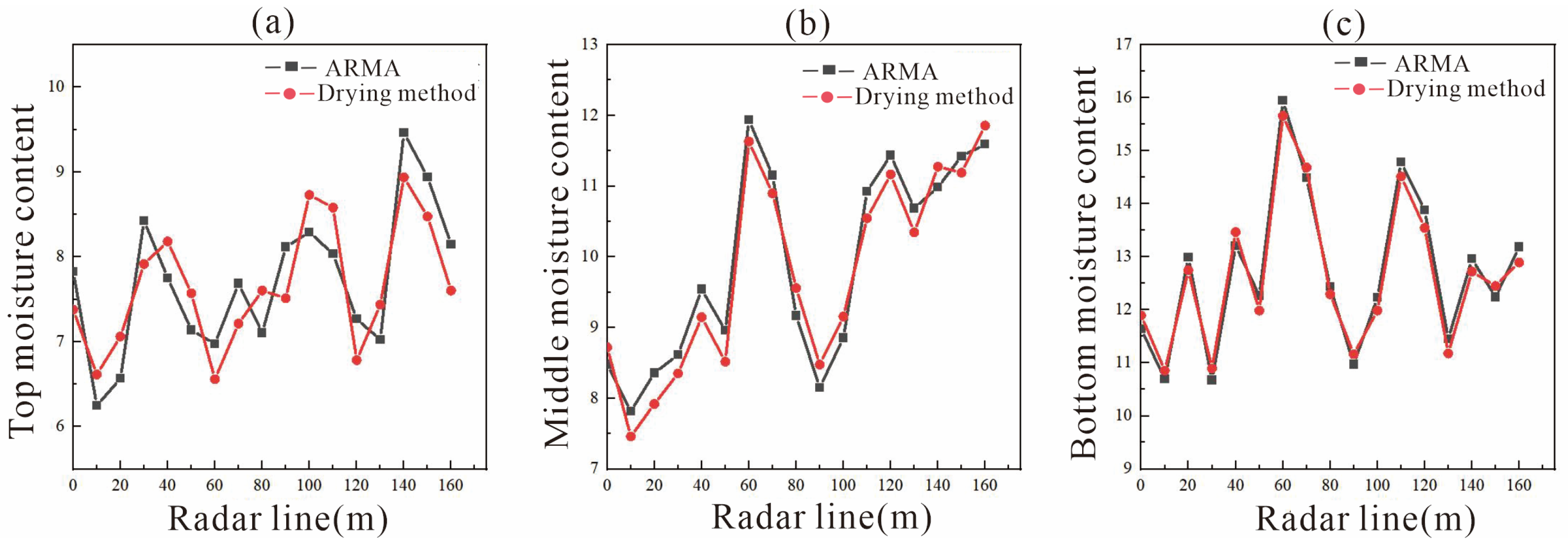

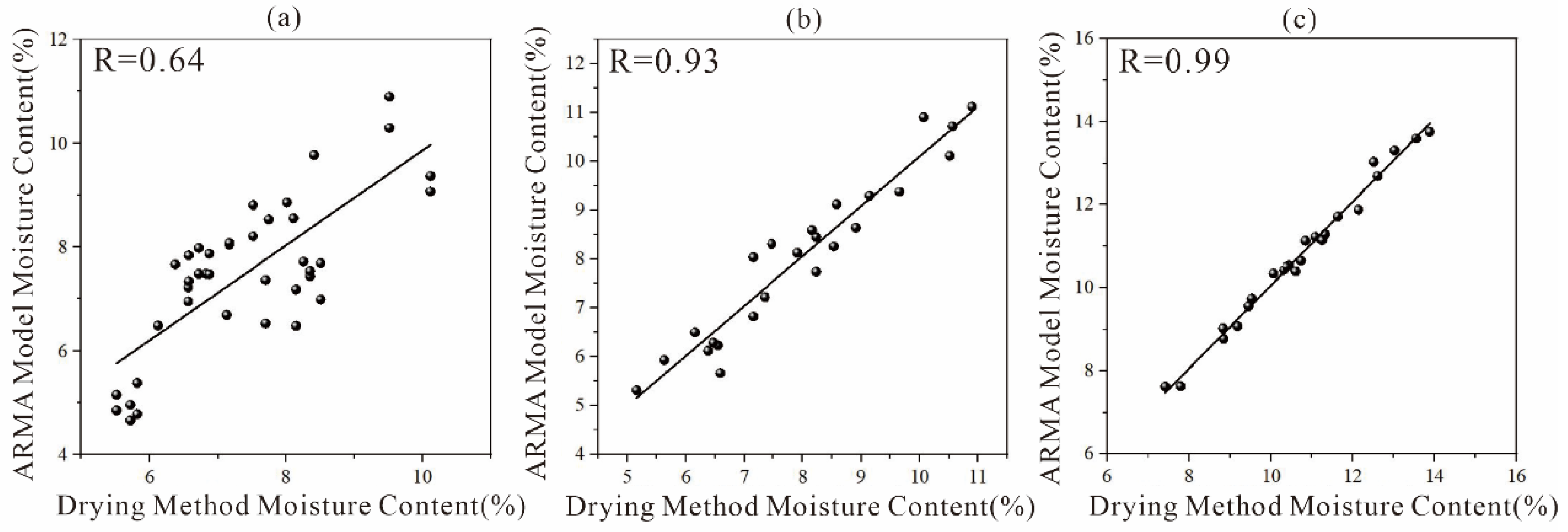

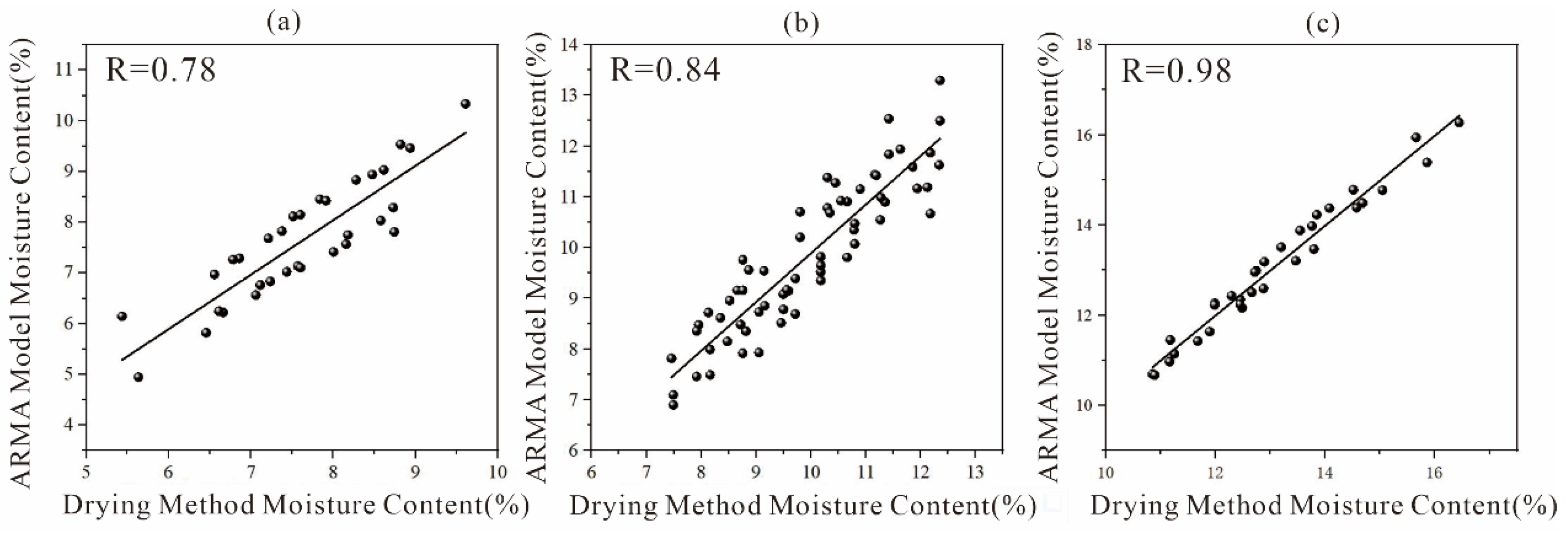

3.2. Comparison of Moisture Content Measured Using the Drying Method and ARMA Inversion

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- This study found that an increase in soil moisture content leads to a significant increase in the relative proportion of the final low-frequency energy component of the ground-penetrating radar signal, which is obvious in the range of 0–225 MHz. This provides an effective theoretical basis for the inversion of soil moisture content in reclamation based on spectrum energy changes.

- (2)

- This study found that in the soil reconstruction area, whether it is the zoning characteristics of the inverted moisture content of layered strata or the curve intersection characteristics of the inverted moisture content of non-uniform strata, the ARMA method can effectively capture the dynamic relationship between the dielectric constant and moisture content of the reclaimed soil in the mining area.

- (3)

- The correlation range between the ARMA inversion value of mixed soil and the measured value using the drying method was 0.64–0.99. The correlation range was 0.78–0.98 in the three-layer soil structure. This indicates that as medium depth and structural uniformity increase, the accuracy of ARMA inversion for water content improves significantly.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, X.; Peng, S.; He, Y. Research on the upward transport of vadose water based on isotope technology: A case study of mining subsidence area in shendong mining area. Earth Sci. Inform. 2025, 18, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhou, W.; Bai, Z.; Cao, Y. Delimiting supervision zones to inform the revision of land reclamation management modes in coal mining areas: A perspective from the succession characteristics of rehabilitated vegetation. Land Use Policy 2023, 131, 106729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, G.; Cao, Y.; Xu, H.; Yang, G.; Wang, S.; Huang, Y.; Bai, Z. Research on typical soil physical properties in a mining area: Feasibility of three-dimensional ground penetrating radar detection. Environ. Earth Sci. 2021, 80, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Bi, Y.; Peng, S.; Zhu, W. Isotope tracers reveal plant-soil water dynamics in shendong mining area: Dryland hydrological and ecosystem recovery. Rhizosphere 2025, 36, 101176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Bi, Y.; Zhu, W.; Bai, Z.; Zhao, P. Stratified soil profiles and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi reshape plant water use strategy and enhance root development in arid mine waste dump restoration. Rhizosphere 2025, 35, 101145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Zhang, S.; Chen, X.; Cui, H.; Xu, Y.; Xia, S.; Xia, K.; Zhou, T.; Zhou, X. Inversion of reclaimed soil water content based on a combination of multi-attributes of ground penetrating radar signals. J. Appl. Geophys. 2023, 213, 105019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, T.; Wang, J.; Wang, J.; Feng, Y. Non-destructive detection of soil volumetric water content in reclaimed soils in an opencast coal mine using hyperbolic reflection in GPR images. Catena 2025, 252, 108845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Bao, J.; Cao, Z.; Li, L.; Zheng, Q. Soil hydraulic parameters estimation using ground penetrating radar data via ensemble smoother with multiple data assimilation. J. Hydrol. 2020, 583, 124552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liao, Z.; Ji, G.; Liu, T.; Yu, X.; Jiao, R. Estimation of the Soil Moisture Content in a Desert Steppe on the Mongolian Plateau Based on Ground-Penetrating Radar. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.A.; Jones, S.B.; Wraith, J.M.; Or, D.; Friedman, S.P. A Review of Advances in Dielectric and Electrical Conductivity Measurement in Soils Using Time Domain Reflectometry. Vadose Zone J. 2003, 2, 444–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahunsi, J.; Pathirana, S.; Cheema, M.; Krishnapillai, M.; Galagedara, L. Estimating soil hydraulic conductivity from time-lapse ground-penetrating radar data in podzolic soils using the green-ampt model. J. Hydrol. 2025, 657, 133059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Li, X.; Duan, R.; Zhao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Che, H.; Liu, G.; Xue, Z.; Yan, C.; Liu, J.; et al. Quality evaluation of ground improvement by deep cement mixing piles via ground-penetrating radar. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 3448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Z.; Gao, J.; Yuan, D. Advances of deep learning applications in ground-penetrating radar: A survey. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 258, 120371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoudzadeh Ardekani, M.R. Off- and on-ground GPR techniques for field-scale soil moisture mapping. Geoderma 2013, 200–201, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Liu, X.; Cao, X.; Fan, B.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, J.; Chen, X.; Lin, H.; Guo, L. Pairing dual-frequency GPR in summer and winter enhances the detection and mapping of coarse roots in the semi-arid shrubland in China. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2020, 71, 236–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Wang, J.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, T.; Yan, X.; Yuan, L.; Chen, W. Influence Analysis and Stepwise Regression of Coal Mechanical Parameters on Uniaxial Compressive Strength Based on Orthogonal Testing Method. Energies 2020, 13, 3640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Desesquelles, H.; Cockenpot, R.; Guyard, L.; Cuisiniez, V.; Lambot, S. Ground-Penetrating Radar Full-Wave Inversion for Soil Moisture Mapping in Trench-Hill Potato Fields for Precise Irrigation. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 6046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongrac, B.; Gleich, D. Remote monitoring system based on cross-hole GPR and deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 17th International Conference on Telecommunications (ConTEL), Graz, Austria, 11–13 July 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, C.; Zhang, S.; Jiang, X.; Chen, F. Monitoring and characterization of water infiltration in soil unsaturated zone through an integrated geophysical approach. CATENA 2023, 230, 107243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Su, Q.; Binley, A.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Z.; Chen, X. Estimation of Surface Soil Moisture by a Multi-Elevation UAV-Based Ground Penetrating Radar. Water Resour. Res. 2023, 59, e2022WR032621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, J.; Butnor, J.R.; Qin, G.; Cui, X.; Fan, B.; Lin, H.; Guo, L. Noninvasive 2D and 3D Mapping of Root Zone Soil Moisture Through the Detection of Coarse Roots With Ground-Penetrating Radar. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR026930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Z.; Xue, S.; Peng, Z.; Liu, F.; Xie, L. A full waveform inversion with noise models in GPR detection. J. Appl. Geophys. 2025, 243, 105970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, H.; Zhang, M.; Bano, M. Harris hawks optimization for soil water content estimation in ground-penetrating radar waveform inversion. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zeng, Z.; Xiong, H.; Lu, Q.; An, B.; Yan, J.; Li, R.; Xia, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, K. Study on Rapid Inversion of Soil Water Content from Ground-Penetrating Radar Data Based on Deep Learning. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Du, Y.; Yue, G.; Li, Y.; Wu, D.; Li, F. Advances in automatic identification of road subsurface distress using ground penetrating radar: State of the art and future trends. Autom. Constr. 2024, 158, 105185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Wang, R.; Chen, B.; Zeng, L.; Chen, Y. Application research of autoregressive and moving average power spectrum in mine ground-penetrating radar structure detection data analysis. Geophys. Prospect. 2023, 71, 1743–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Wu, Z.-Y.; Wang, L.; Wu, Y.-B. Application of the ground penetrating radar ARMA power spectrum estimation method to detect moisture content and compactness values in sandy loam. J. Appl. Geophys. 2015, 120, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Chen, B.; Wu, Z.; Nie, J.; Li, S.; Geng, X.; Li, S. Soil moisture estimation based on GPR power spectrum and envelope amplitude in sand loam. Trans. CSAE 2018, 34, 121–127. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewer, M.; Igel, J.; Wagner, N. Spectral decomposition of soil electrical and dielectric losses and prediction of In situ GPR performance. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2016, 9, 212–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

He, Y.; Li, K.; Fang, L.; Peng, S.; Tian, Z.; Meng, L.; Luo, J. The Application of Ground-Penetrating Radar Inversion in the Determination of Soil Moisture Content in Reclaimed Coal Mine Areas. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010350

He Y, Li K, Fang L, Peng S, Tian Z, Meng L, Luo J. The Application of Ground-Penetrating Radar Inversion in the Determination of Soil Moisture Content in Reclaimed Coal Mine Areas. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):350. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010350

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Yunlan, Kexin Li, Lulu Fang, Suping Peng, Zibo Tian, Lingyuan Meng, and Jie Luo. 2026. "The Application of Ground-Penetrating Radar Inversion in the Determination of Soil Moisture Content in Reclaimed Coal Mine Areas" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010350

APA StyleHe, Y., Li, K., Fang, L., Peng, S., Tian, Z., Meng, L., & Luo, J. (2026). The Application of Ground-Penetrating Radar Inversion in the Determination of Soil Moisture Content in Reclaimed Coal Mine Areas. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 350. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010350