1. Introduction

Nuclear energy, recognized as a clean and efficient alternative to fossil fuels, has been extensively utilized worldwide [

1,

2]. However, the generation of nuclear power and continued nuclear testing produce significant volumes of radioactive waste [

3]. Various types of disposal facilities have been constructed globally to manage this waste [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Near-surface disposal (NSD) is a common method used for the management of low- and intermediate-level, short-lived radioactive waste. Compared with deep geological disposal, NSD facilities are more susceptible to environmental and anthropogenic disturbances [

8]. If the engineered barriers fail, radionuclides may migrate into the biosphere, thereby posing potential risks to the environment and human health [

9,

10,

11].

In NSD systems, disposal units are typically placed within the vadose zone, above the groundwater table, leaving a certain vertical separation [

12]. This unsaturated layer plays a crucial role in retarding radionuclide migration, as sorption and decay processes within the vadose zone significantly reduce radionuclide concentrations reaching groundwater and delay their arrival time [

13,

14,

15,

16]. Consequently, determining the depth to the groundwater table is critical for safety assessments of NSD sites. However, because potential leakage from the disposal units may occur hundreds or thousands of years in the future, the groundwater table will be affected by both climatic variability and human activities over long timescales [

17,

18]. Therefore, evaluating groundwater level dynamics under various climatic and anthropogenic scenarios is essential for assessing the long-term safety of the repository.

Numerical simulation is a vital method for repository safety assessment, enabling the simulation and prediction of groundwater level changes over long timescales under the influence of multiple factors. Many researchers have utilized numerical simulation methods for the safety assessment of repositories [

19,

20,

21]. Li et al. [

22] used TOUGH3 to construct a groundwater flow numerical model for a high-level waste deep geological repository, simulating and predicting the impact of climate change on groundwater levels. Zhang et al. [

23] used FEFLOW to construct a groundwater flow numerical model for a near-surface, low- and intermediate-level waste repository, simulating groundwater level changes under climate change and artificial drainage conditions. Zhang et al. [

24] coupled HYDRUS-1D and FEFLOW to construct a numerical model for variably saturated flow and radionuclide transport at a near-surface repository. Wang et al. [

25] used the MODFLOW and MT3DMS programs within the GMS software version 10.8 to construct a numerical model for groundwater flow and radionuclide transport at a low-level waste repository.

Repository sites are often located in areas dominated by bedrock aquifers, where groundwater primarily occurs in fractures, making numerical modeling particularly challenging [

26,

27]. On one hand, this is due to the difficulty in accurately generalizing the permeability parameters of fractured media [

28,

29]; on the other hand, the high cost of drilling boreholes in fractured areas leads to a scarcity of groundwater level data, posing difficulties for numerical model validation. Currently, although some studies use field hydraulic test results as permeability parameters for rock layers and use average water levels from a few boreholes over several years to validate numerical models [

22,

30], this model construction approach is evidently insufficiently precise. Firstly, due to the complexity of fracture development patterns in rock layers, permeability parameters obtained solely through hydraulic tests have limitations [

31]. Secondly, data from a few simple observation wells cannot adequately calibrate the regional groundwater flow field, rendering the established model insufficiently reliable. Overall, current research lacks a comprehensive analysis of fracture media permeability, as well as effective methods for validating groundwater flow models in fractured regions.

The operational period of a disposal site extends over a long timescale, often spanning several centuries; therefore, it is necessary to account for the long-term effects of climate change on groundwater levels. To accurately construct a numerical groundwater flow model for areas containing fractured media, this study proposes a methodology for accurately constructing a transient groundwater flow model in a fractured-rock environment. The approach integrates: (1) borehole televiewer interpretation and hydraulic conductivity tensor computation to estimate fracture permeability; (2) field hydraulic tests for empirical verification of the calculated parameters; and (3) groundwater flow direction tests and long-term monitoring data for model calibration and validation. The developed model was subsequently used to predict groundwater level variations under different climatic and pumping scenarios, providing a scientific basis for the safety assessment of NSD facilities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The study area is located in northwestern China (

Figure 1a). It extends approximately 15 km from north to south and 13 km from east to west (

Figure 1b). The topography generally slopes from north to south, with surface elevations ranging from 1230 to 1270 m. The area is characterized by an arid temperate climate, with an average annual precipitation of approximately 60 mm and a high potential evaporation of 2079–2515 mm/yr. Stratigraphically, the area is composed mainly of Quaternary unconsolidated sediments that overlie Ordovician-Silurian and Neogene bedrock formations.

As shown in

Figure 1b, the repository is situated in the northwestern part of the study area. The surface lithology in the repository area consists of a 2–5 m thick layer of gravel with interbedded breccia, underlain by strongly, moderately, and slightly weathered bedrock layers. The bedrock types include three categories: mudstone, sandstone, and marble. The groundwater type is primarily fractured bedrock aquifer. The groundwater level is primarily controlled by climatic conditions, exhibiting natural fluctuations, with a depth to the water table of approximately 10 m. The water table resides within the jointed fractures of the bedrock. In the southern part of the study area, a large agricultural zone exists (

Figure 1b), where intensive groundwater extraction is taking place. The stratigraphy in this zone primarily consists of thick Quaternary unconsolidated sediments, including gravel with breccia layers, medium sand, fine sand, and clay. The groundwater type in this area is primarily pore groundwater. Due to intensive pumping, a cone of depression has developed, and the depth to the water table is approximately 20 m.

In the regional context, groundwater in the northern part of the study area is primarily fractured bedrock groundwater, with an overall flow direction from north to south. It is mainly recharged by atmospheric precipitation and lateral inflow from the piedmont area, while evaporation serves as the dominant discharge mechanism. In the southern area, groundwater occurs mainly in unconsolidated sediments and flows from the surrounding areas toward the center of the depression cone in the farm area. Recharge is derived primarily from atmospheric precipitation and lateral inflow from nearby surface water bodies such as Beihaizi Lake to the east, while discharge occurs mainly through evaporation and anthropogenic extraction.

Overall, the hydrogeological conditions of the study area are highly heterogeneous and complex. This complexity is primarily attributed to the variable lithological characteristics, which include both porous and fractured media. The permeability of porous media can be determined through field tests; however, that of fractured media is more challenging to quantify, as it depends on multiple factors including lithologic properties, fracture network connectivity, and fracture aperture and spacing. Moreover, notable differences exist between the southern and northern parts of the study area in terms of groundwater occurrence and groundwater level dynamics. In the southern agricultural zone, numerous irrigation wells have been developed, which provide data for characterizing the regional groundwater flow field. In contrast, most of the northern region is underlain by fractured bedrock aquifers, for which groundwater level monitoring data are scarce, making it difficult to accurately delineate the groundwater flow field. Therefore, the complexity of these hydrogeological conditions presents challenges for constructing a reliable numerical model.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. Fracture Geometry Measurement and Permeability Tensor Computation

Considering the complexity of fracture development, borehole televiewer logs were initially analyzed to determine fracture orientations and spacings. Subsequently, the permeability of the fractured rocks was computed based on the hydraulic conductivity tensor theory and compared with results from field packer tests.

The hydraulic conductivity tensor of a fractured rock mass is derived from flow through individual fractures, which are idealized as laminar flow between two smooth, parallel plates of uniform aperture. In this model, the flow velocity is proportional to the cube of the aperture [

32]. For

dominant fracture sets, the equivalent hydraulic conductivity tensor of the rock mass can be expressed as:

In the equation: is the dip direction of the -th fracture set; is the dip angle of the -th fracture set; is the fracture aperture (m); is the fracture spacing (m); is the gravitational acceleration (m/s2); is the kinematic viscosity of water (m2/s); is the total number of fracture sets developed in the rock mass; is the equivalent permeability coefficient of the i-th fracture set (m/s); is the permeability tensor of the rock mass (m/s).

The characteristic equation of the matrix was solved to obtain its three eigenvalues—the principal values of the permeability tensor (, , ). Substitute each eigenvalue into the characteristic equation to determine the corresponding eigenvectors , , ), , , ), , , ), , , ), and , , ). After obtaining the eigenvectors, the principal permeability directions derived from the tensor were converted to fracture orientations (strike and dip).

Fracture dip direction. If

, then

If , first change the signs of , , to their opposites and then substitute into Equation (4).

The geometric mean of the three principal values of the permeability tensor was taken as the composite permeability

:

2.2.2. Field Investigations

- (1)

Packer Tests

When evaluating the permeability of fractured rock masses, the accuracy of parameters derived solely from fracture geometry measurements must be validated. In this study, the permeability coefficient of the fractured rock mass was first calculated using the permeability tensor theory described in

Section 2.2.1. Subsequently, the permeability of the fractured rock mass was comprehensively analyzed in conjunction with the results of field hydraulic tests.

The fractured rock mass at the repository site was composed primarily of mudstone, sandstone, and marble. Considering that varying degrees of rock weathering result in vertical changes in permeability, sectional packer tests were conducted in boreholes of different lithologies to obtain vertical permeability parameters for each rock type. The locations of the packer test boreholes are shown in

Figure 1c. Borehole CK1 was drilled in sandstone, CK2 in marble, and CK3 in mudstone. The vertical lithologic characteristics of the three boreholes are as follows: the surface layer consists of 0–5 m of gravel with sandy–gravel interbeds, underlain by 4–8 m of strongly to moderately weathered rock, with a relatively thick, slightly weathered layer at the bottom.

- (2)

Groundwater Flow Direction Tests

To overcome the challenges of model construction and calibration caused by limited groundwater level data in the northern fractured zone, seven groundwater flow direction tests (BK1-BK7) were conducted from north to south across this area. The locations of these boreholes are shown in

Figure 1b, and groundwater flow directions were determined using the single-well tracer method [

33].

After tracer injection into the observation well, saline groundwater from the upstream portion of the aquifer continuously recharged the well. The tracer was subsequently transported by groundwater flow out of the borehole and into the aquifer, dispersing mainly along the flow direction within a defined angular range. Because the inflowing groundwater was saline, the tracer concentration exhibited a maximum in the inflow direction and a minimum in the outflow direction. Consequently, the centroid of the tracer concentration distribution in the horizontal plane shifted toward the upstream direction of groundwater flow. Since the concentration of the saline tracer is linearly related to its electrical conductivity, the spatial conductivity distribution was used to represent tracer concentration, thereby enabling the determination of groundwater flow direction.

2.2.3. Groundwater Flow Numerical Model

For the fractured media extensively developed in the northern part of the study area, permeability parameters derived from both field hydraulic tests and theoretical fracture-permeability tensor calculations were integrated. The northern part of the study area is dominated by fractured media, whereas the southern part is primarily composed of porous media. To enable integrated numerical simulation of the entire region, the subsurface media were therefore conceptualized uniformly as an effective porous medium. Based on this conceptualization, a three-dimensional groundwater flow model of the study area was constructed using the MODFLOW module within GMS software. First, a steady-state flow model was established. In regions of the north where groundwater observation wells were sparse, the simulated groundwater flow field was verified using results from the field groundwater flow direction tests. Subsequently, a transient flow model was developed, and long-term groundwater level variations were calibrated against data from dynamic monitoring wells within the study area. Finally, the calibrated model was applied to simulate groundwater level responses at the disposal site under various precipitation conditions and groundwater-extraction scenarios.

Horizontally, the northern and northwestern boundaries of the study area mark the transition between the piedmont and the plain. These boundaries receive lateral recharge from the piedmont and were therefore represented as specified-flux boundaries. The western and eastern boundaries had essentially no water exchange and were generalized as no-flow boundaries. The southeastern part contained Beihaizi Lake, which exhibited significant hydraulic interaction with groundwater, and was assigned as a general head boundary. In the southern farm area, long-term pumping for irrigation had created a large cone of depression, with surrounding groundwater flowing laterally into the farm area. Therefore, the southern and southwestern boundaries of the study area were treated as flux boundaries. The generalized boundary conditions of the study area are shown in

Figure 1b.

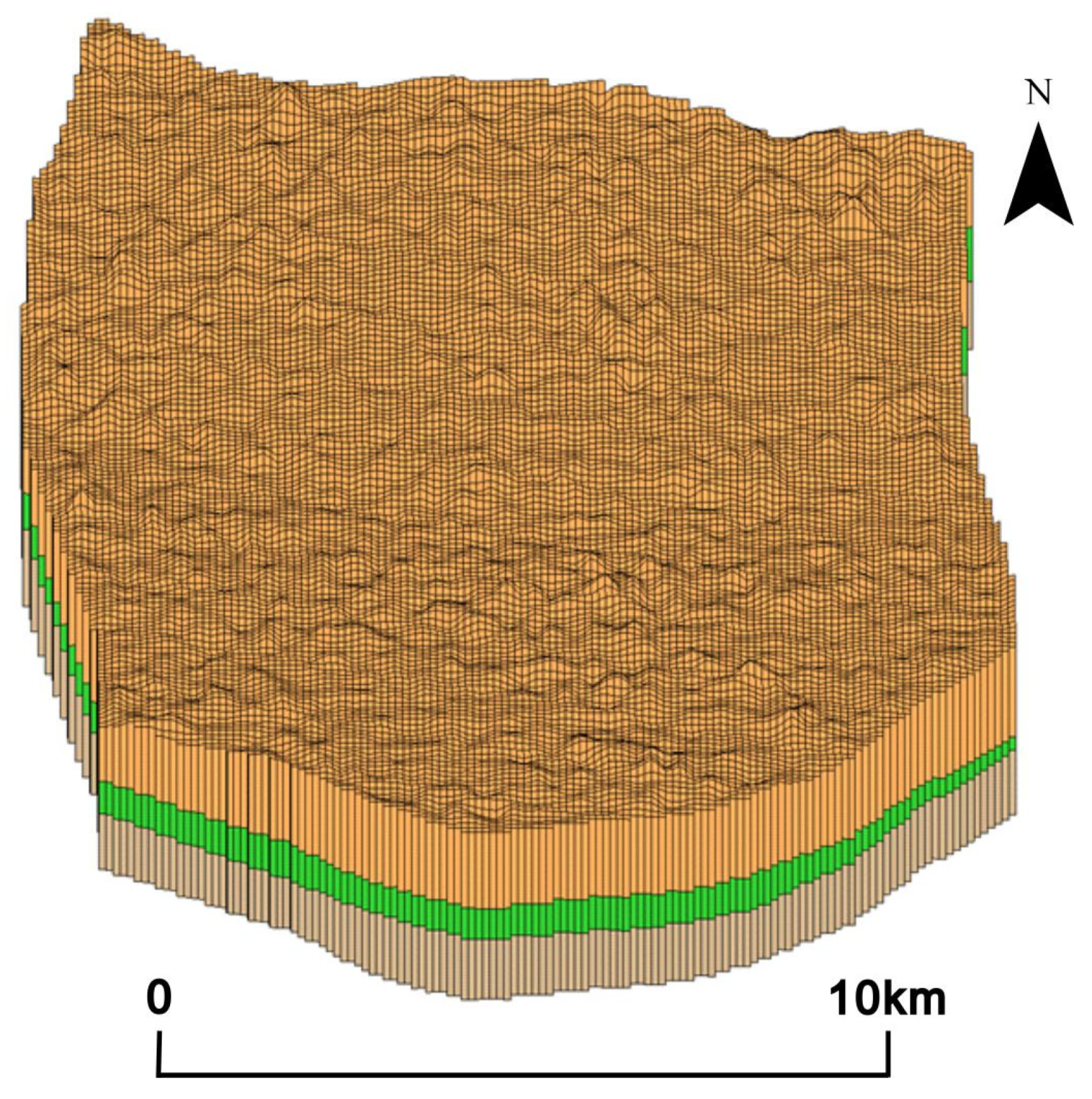

Vertically, based on borehole data and geological–hydrogeological conditions, the aquifer system in the study area was conceptualized as comprising three layers. The first layer was an unconfined aquifer, 15–65 m thick. The second layer was an aquitard, 10–25 m thick. The third layer was a confined aquifer, 40–55 m thick. The model domain was discretized using a rectangular grid with a cell size of 150 m × 150 m. The vertical layering and grid discretization are shown in

Figure 2. Recharge sources in the study area include atmospheric precipitation infiltration, agricultural irrigation return flow, piedmont lateral recharge, and lateral recharge from Beihaizi Lake. Discharge components include artificial extraction and evaporation. The model simulation period was from January 2021 to December 2024, with one-month stress periods. The prediction period was set to 50 years (2025–2075).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fracture Permeability Analysis

Based on lithology, degree of weathering, and the number of fractures identified from borehole core descriptions, the boreholes were divided vertically into zones. The permeability coefficients at different depths for each borehole were then calculated for each zone using the permeability tensor theory. Boreholes CK1, CK2, and CK3 were each divided into four vertical zones. The zones for CK1 are: 3–13 m; 13–41 m; 41–73 m; 73–80 m. For CK2: 6–20 m; 20–50 m; 50–67 m; 67–78 m. For CK3: 7–16 m; 16–43 m; 43–53 m; 53–78 m.

Using the equations presented in

Section 2.2.1 and the fracture geometry parameters derived from borehole televiewer interpretations, the permeability tensors, principal values, principal directions, and composite permeability coefficients were calculated for each borehole zone. The results are shown in

Table 1,

Table 2 and

Table 3.

The comprehensive permeability coefficient for sandstone (CK1) ranges from 2.78 × 10−8 to 2.51 × 10−7 m/s, for marble (CK2) from 1.05 × 10−7 to 4.08 × 10−7 m/s, and for mudstone (CK3) from 8.52 × 10−8 to 1.91 × 10−7 m/s. The values show limited variation, remaining within approximately one order of magnitude. Vertically, permeability coefficients calculated using the tensor theory tend to decrease with increasing depth.

In evaluating fractured-rock permeability, the coefficients derived from tensor theory are relatively idealized, as they do not explicitly account for factors such as fracture connectivity, surface roughness, limited fracture extent, or mineral fillings. Therefore, it is necessary to comprehensively evaluate the permeability of fractured rocks by integrating the tensor-based results with permeability coefficients obtained from hydraulic testing. The permeability coefficients measured by packer tests for the three boreholes are shown in

Figure 3.

The hydraulic test results show that the measured permeability coefficient for sandstone (CK1) ranges from 5.79 × 10−9 to 1.86 × 10−7 m/s, for marble (CK2) from 1.04 × 10−8 to 7.25 × 10−7 m/s, and for mudstone (CK3) from 4.63 × 10−9 to 2.1 × 10−6 m/s. The values vary relatively more, differing by 1 to 3 orders of magnitude.

Overall, permeability coefficients calculated using the tensor approach tend to exceed those obtained from hydraulic testing, and the measured coefficients exhibit greater vertical variability. This is because the permeability tensor calculation does not consider fracture connectivity, and the presence of fracture fillings can also lead to overestimation of the calculated permeability coefficient. Specifically, the hydraulic test value in the deeper part of CK3 is larger than the result from the permeability tensor calculation. This is because the deeper part of this borehole intersects fewer fractures with larger spacing, resulting in a smaller comprehensive permeability coefficient. Hence, relying solely on tensor-based calculations may introduce significant deviations, and a comprehensive approach considering multiple influencing factors is essential for accurately assessing subsurface permeability.

By integrating the results from both the tensor-based calculations and the hydraulic tests, and considering vertical zoning by lithology, permeability coefficients for different rock types and weathering degrees were determined. The permeability coefficient for strongly to moderately weathered sandstone ranges from 1.39 × 10−8 to 2.51 × 10−7 m/s, and for slightly weathered sandstone from 1.85 × 10−9 to 1.91 × 10−7 m/s. For strongly to moderately weathered marble, the range is 1.97 × 10−8 to 4.08 × 10−7 m/s, and for slightly weathered marble, it is 1.04 × 10−8 to 2.01 × 10−7 m/s. For strongly to moderately weathered mudstone, it is 1.27 × 10−8 to 2.1 × 10−6 m/s, and for slightly weathered mudstone 2.31 × 10−9 to 6.76 × 10−7 m/s.

3.2. Model Calibration and Validation

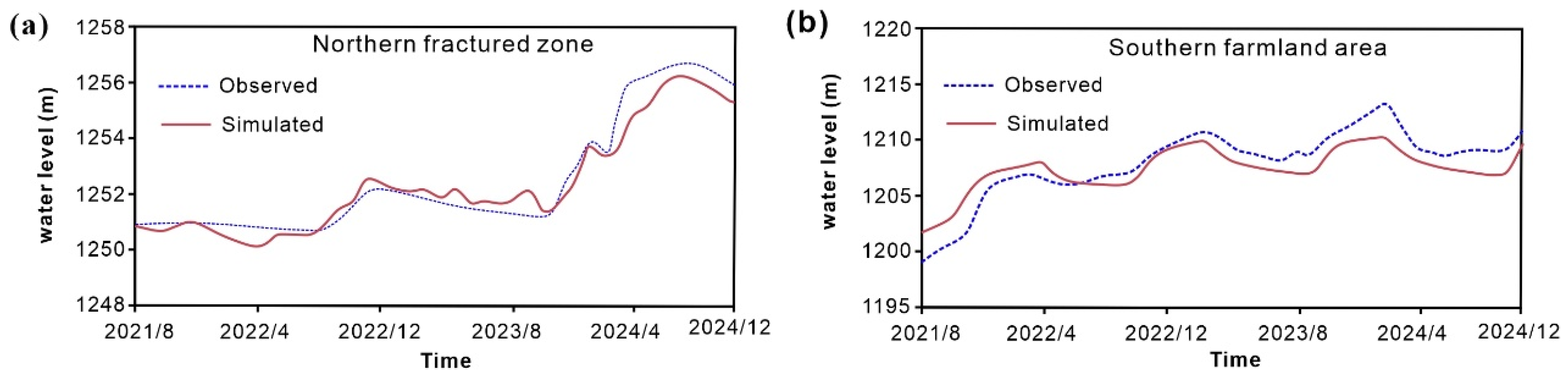

The simulated steady-state groundwater flow field and the measured field in the southern farm area are presented in

Figure 4. Two observation wells were selected for long-term dynamic calibration of groundwater levels, one located in the northern fractured area and one in the southern farm area, as shown in

Figure 5. The morphology of the simulated flow field and the trend of the water level hydrographs are generally consistent with the measurements. Based on the calculations, the normalized root-mean-square error for the long-term groundwater-level monitoring wells is 4.8%. Therefore, based on both the flow-field and observation-well calibration results, the model calibration was considered reliable, and the simulations accurately reflect the actual groundwater flow and dynamics in the southern farm area.

The results of the groundwater flow direction tests conducted in the northern fractured area are shown in

Table 4. For ease of comparison, the flow directions for the 7 boreholes are also annotated on the groundwater flow field map, as shown in

Figure 4. It can be seen from the figure that within the northern fractured area, the simulated flow directions in the groundwater flow field generally match the measured directions. Combined with the fitting of the water level hydrographs from the northern observation well, the simulation results can reflect the actual groundwater flow field and dynamic characteristics in the northern fractured area of the study area.

In summary, considering the comparison of simulated and measured flow fields in the southern farm area, the comparison between measured flow directions and the simulated flow field in the northern fractured area, and the fitting of long-term groundwater level trends in both north and south observation wells, the accuracy of the constructed numerical model is sufficient to support subsequent predictions of groundwater level changes under different scenarios.

Furthermore, from the groundwater flow field, it can be observed that under topographical control, groundwater in the northern part of the study area flows from north to south. In the south, however, long-term human extraction in the farm area has created a significant cone of depression. Human extraction has altered the natural groundwater flow direction; the closer to the southern farm area, the more the flow direction shifts towards the center of the depression cone. According to the flow direction test results, the BK6 borehole in the south is shifted by 53° towards the depression center compared to the BK1 borehole in the north. Therefore, in simulating groundwater level changes under different scenarios, human extraction in the southern farm area must be considered, and its potential impact on the groundwater level in the repository area under varying pumping intensities requires attention.

3.3. Analysis of Groundwater Level Dynamics at the Repository Site Under Different Scenarios

The dynamic variation of groundwater levels at the NSD site is crucial for its safety evaluation. In the northern fractured zone where the disposal site is located, groundwater level fluctuations are primarily influenced by rainfall. In contrast, in the southern agricultural area of the study region, groundwater has been severely overexploited. As shown in

Section 3.2, human extraction activities downstream have already exerted a measurable influence on the groundwater flow pattern in the northern area. The problem of groundwater overexploitation has attracted the attention of local authorities. In response, they have implemented water-saving agricultural measures and initiated water diversion from a nearby reservoir to reduce groundwater abstraction in the agricultural zone. How the reduction of groundwater extraction in the southern agricultural area will affect groundwater levels at the disposal site is an important concern for the site’s safety assessment. Therefore, the previously constructed numerical groundwater flow model was used to simulate and predict groundwater level variations at the disposal site over the next 50 years (2025–2075) under different rainfall and groundwater-extraction scenarios.

Based on actual data from a meteorological station near the study area, the average annual precipitation in the study area over the past 30 years was approximately 60 mm. The mean annual precipitation during the 15 driest years was 51 mm, whereas that during the 15 wettest years was 69 mm. The average annual extraction volume over the past 5 years was 31.08 million m3. Based on the collected precipitation and extraction data, three predictive scenarios were designed for model simulation. (1) Average rainfall scenario: Precipitation was set to the 30-year mean, and groundwater extraction to the five-year average volume. (2) Groundwater withdrawal cessation scenario: To assess the maximum possible influence of southern farm-area pumping on groundwater levels at the northern repository, groundwater extraction was set to zero, while precipitation remained the same as in the average-precipitation scenario. (3) Heavy rainfall scenario: Precipitation was set to the mean of the wetter 15 years (69 mm), while groundwater extraction was maintained at the five-year average level. The rainfall scenarios were established based on actual precipitation data from the past 30 years. The data were divided into two groups according to rainfall magnitude, with the average precipitation of the 15 wetter years designated as the input value for the heavy rainfall scenario. This configuration ensures applicability to future climate conditions.

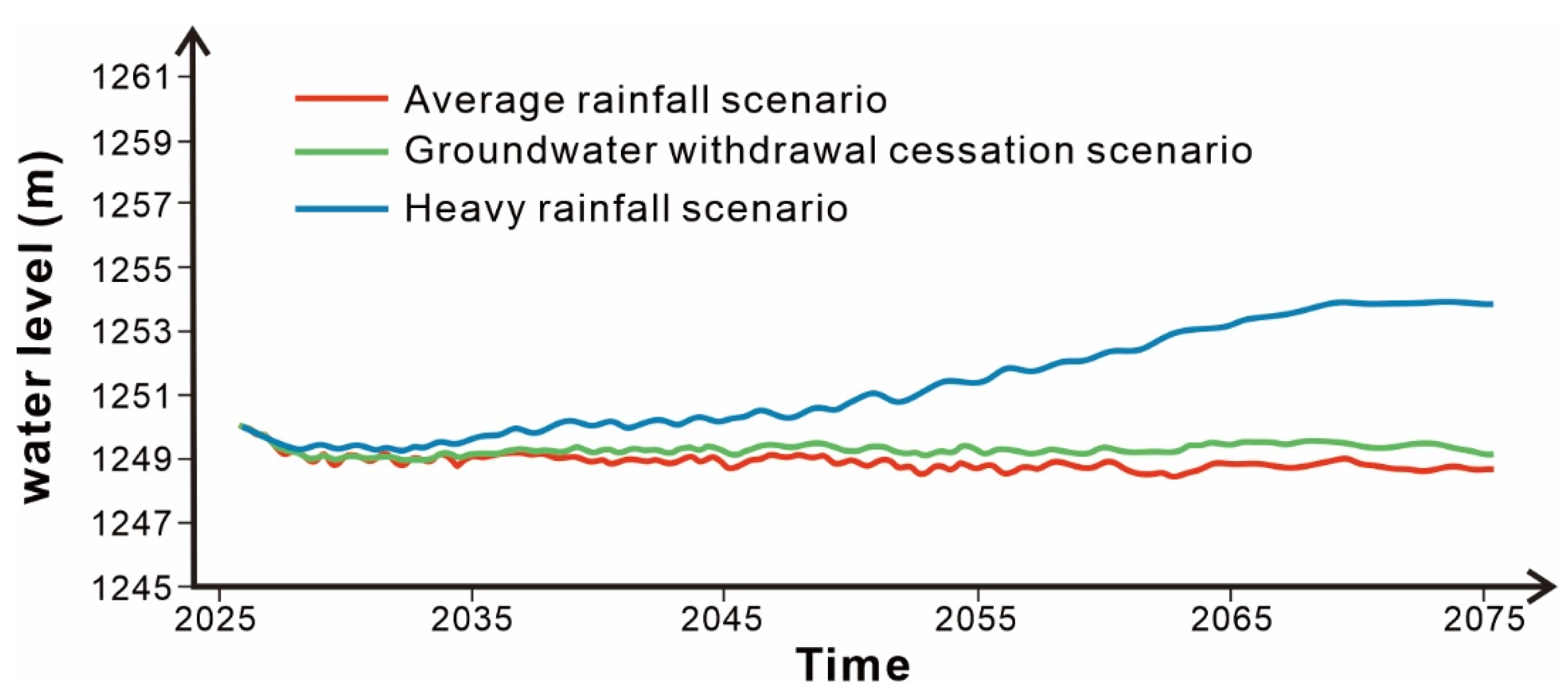

The simulation results for the three scenarios are shown in

Figure 6. Under the average-rainfall scenario, the groundwater level at the disposal site remained essentially stable throughout the 50-year simulation period. The cessation of groundwater extraction in the southern agricultural zone exerted only a minor influence on groundwater levels at the northern disposal site. This influence became evident approximately 14 years after pumping cessation, reaching its maximum around 38 years later (in 2063), when the groundwater level increased by about 0.3 m. This weak response is primarily attributed to the dominance of low-permeability fractured rocks in the northern part of the study area, which results in slow groundwater flow. Moreover, the disposal site is located approximately 5 km from the agricultural area. Consequently, the reduction of southern pumping had only a minor impact on groundwater levels at the disposal site. In contrast, increased rainfall intensity had a more pronounced effect. This is attributable to the combined effects of the direct influence of rainfall on groundwater levels and the increased piedmont lateral recharge associated with higher precipitation. After 50 years, under the heavy rainfall scenario, the groundwater level at the disposal site rose by approximately 5.2 m relative to the average rainfall scenario. With the elevation of the disposal unit’s base slab at 1259 m, the current groundwater level is now 6 m below it. From the perspective of groundwater level response to rainfall and downstream anthropogenic extraction, regulators must pay particular attention to changing climatic conditions. Under persistent heavy rainfall, appropriate drainage measures should be taken to ensure the safe operation of the disposal site.