1. Introduction

Risk assessment and management in historic city centers represent one of the most complex challenges in contemporary conservation and urban planning. These contexts, characterized by a dense historic urban fabric with buildings differing in construction period, materials, and techniques, are exposed to multiple natural hazards (e.g., seismic, flood, and landslide) whose interaction amplifies the potential effects on the built heritage. In this scenario, the increasing frequency and intensity of extreme events, associated with climate change and the intrinsic fragility of historic fabrics, highlight the need to develop knowledge and assessment tools capable of integrating different scales, sources, and domains from a preventive rather than exclusively emergency-oriented perspective. Current practices, however, display significant limitations due to the fragmentation of available data and the limited interoperability between territorial information systems and building databases. Many approaches focus on single hazards or specific disciplinary domains, without providing coordinated procedures for semantic harmonization or scalable interoperability models. In addition, the availability of detailed and up-to-date information is often limited, especially in smaller contexts where there are low resources for monitoring, surveying, or modeling activities. These conditions make it difficult to construct integrated knowledge frameworks capable of linking natural hazards, structural vulnerability, and the socio-economic components of risk.

In recent years, scientific research and international regulations have increasingly emphasized the need for multi-level and multi-scale methodologies [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5] aimed at data standardization, comparability of assessments, and transparency of decision-making processes in risk management. The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030 [

6] identifies risk knowledge as an essential prerequisite for urban resilience, promoting the development of shared databases. In line with these principles, the INSPIRE Directive (Infrastructure for Spatial Information in the European Community, 2007/2/EC) and its related Technical Guidelines, particularly those concerning the Natural Risk Zones theme [

7,

8], define specific, interoperable requirements for the collection, harmonization, and dissemination of data related to the components of risk, fostering the creation of interoperable digital infrastructures and the sharing of geospatial datasets according to common attributes and ontologies. At the administrative scale, Administrative Units and Statistical Units [

9,

10] themes provide a framework for linking territorial, demographic, and socio-economic information, ensuring logical continuity across the municipal, inter-municipal, and regional levels. At the building scale, the Buildings [

11] theme provides a structured data model for the geometric and typological–constructional characterization of the built environment and connects territorial and building data. In this perspective, the Digital Building Logbook (DBL) [

12,

13] is emerging as a key reference for semantic integration, as it represents the most detailed information layer and can incorporate data from the higher INSPIRE levels, including the Natural Risk Zones theme. Recent studies [

14,

15,

16,

17] have highlighted both its potential and its limitations: the combination of traditional and digital sources can cover up to 88% of the relevant indicators, but the low interoperability between models and the insufficient availability of national data confirm the need to conceive the DBL as a connective gateway between systems rather than as a static archive. In the same direction, the Risk Data Hub developed by the Joint Research Centre (JRC) within the Disaster Risk Management Knowledge Centre (DRMKC) provides a harmonized framework of data and indicators to support European policies for risk mitigation and climate adaptation. In the field of built heritage protection, the ICOMOS–ICCROM Guidelines (Managing Disaster Risks for World Heritage, 2010) propose methodologies for the assessment and mitigation of risk in cultural and natural heritage contexts, emphasizing the importance of integrated and multidisciplinary approaches. Overall, these reference frameworks suggest an integrated approach to risk management—promoting the adoption of interoperable information tools and the use of shared digital environments capable of presenting a unified perspective on interrelated territorial analyses and building descriptors—to support prevention and management strategies for built heritage.

Despite the progress made in hazard-specific (mono-hazard) vulnerability and risk mapping and the simultaneous evolution of multi-hazard frameworks, an operational gap persists in translating heterogeneous datasets into a coherent, multi-scale decision support workflow for historic city centers. In practice, mono-hazard studies often generate detailed thematic outputs that remain difficult to compare across hazards and integrate into a unified prioritization logic, while multi-hazard contributions frequently rely on aggregated overlays that are not systematically linked to building-scale descriptors. Therefore, direct connections between municipal screening, the identification of hotspot areas (e.g., census units), and subsequent building aggregate/building prioritization are still limited. Moreover, integration between GIS-based multi-hazard results and building information layers is often addressed conceptually, whereas replicable data architectures that ensure semantic consistency, traceability, and “interoperability-ready” building records (e.g., DBL fields) remain scarce, especially in low-resource contexts where detailed surveys and continuous updates are not feasible.

In summary, the research gap lies in the limited availability of traceable, end-to-end procedures that connect territorial screening to actionable prioritization at both the building aggregate and building scales in historic centers. This paper addresses this gap by operationalizing a replicable multi-scale workflow supported by an INSPIRE-aligned, DBL-ready relational data architecture, enabling interoperability-ready outputs toward GIS–BIM environments.

Literature Review

In line with this general trend, the scientific literature on multi-hazard risk also reflects a tendency toward the integration and standardization of analysis processes. In this work, the literature review specifically focuses on seismic, flood, and landslide hazards, which are among the most relevant and systematically documented natural threats to historic city centers in Europe. Several authors have addressed the issue of the coexistence of multiple hazards within the same area and have highlighted the need to represent the interactions, correlations, and possible cascading effects that such phenomena may generate. One line of research is based on the construction of aggregate indices obtained through multicriteria analysis techniques, which enable the combination of heterogeneous factors within a single evaluation framework. In particular, Ref. [

18] proposes an integrated seven-step method for assessing multi-hazard intensity on cultural resources, combining probabilistic hazards (earthquakes, floods) and qualitative hazards (landslides, wildfires, and soil erosion) within an aggregated index. Similarly, Ref. [

2] employs the PROMETHEE method to define homogeneous hazard zones derived from the intersection of different thematic layers. Fuzzy variants of AHP are used by [

19,

20] to weight risk factors and construct aggregate indices, whereas Ref. [

21] proposes a simpler exploratory approach based on the superposition of hazard maps. Alongside these qualitative or semi-quantitative methods, other studies pursue the objective of harmonizing impact metrics to ensure comparability between different hazards. Among these, Refs. [

22,

23] share an approach oriented toward multi-layer single-hazard analysis and the quantification of economic losses as a risk assessment metric, employing monetary or percentage indicators to compare the impact of seismic and flood scenarios.

More recent research explores computational approaches and predictive models based on machine learning: Ref. [

24] compares several classification algorithms (Random Forest, SVM, BRT, and MARS) for the development of multi-hazard susceptibility maps, identifying MARS as the model with the best predictive performance. At a broader territorial scale, frameworks such as TERIMAAS [

1] and Landscape Digital Twins [

25] focus on the multi-scale generation and integration of multi-hazard maps, harmonizing heterogeneous data and spatial analyses to evaluate territorial resilience and accessibility under event scenarios. In [

26], a decision support system (DSS) is applied for the prioritization of interventions on critical infrastructures, demonstrating the operational effectiveness of multi-hazard aggregation models.

In addition, studies on the vulnerability of built heritage propose a wide range of methodologies calibrated to different scales of analysis. At the macroscale, simplified macroscale seismic models such as RISK-UE [

27] and GNDT level II [

28] are consolidated tools for extensive analyses, based on typological–constructional indices derived from statistical, cadastral, or census parameters. Similar approaches have been developed for flood vulnerability [

29,

30] and landslide vulnerability [

31,

32], in which the load-bearing capacity of historic built heritage is correlated with the intensity or susceptibility of the phenomenon, producing homogeneous maps that are useful for identifying critical areas, even in the absence of dense historical event data. At the mesoscale, index-based methods [

33,

34] extend the GNDT approach by including interaction factors between contiguous buildings and morpho-settlement conditions, while in the case of flood vulnerability [

35,

36,

37], a distinction is introduced between sensitivity and exposure components, which are combined into aggregate indices. For landslide hazard, recent studies [

38,

39] employ semi-quantitative models that relate structural and morphological parameters to estimate the propensity to damage as a function of slope thrust or movement. At the microscale, the assessment is based on geometric, constructional, and conservation state parameters derived from direct surveys or information models [

36,

40,

41], which are applied to the three main hazard types to define consistent and comparable damage indicators.

Regarding exposure assessment, the reviewed literature reveals recurring approaches in which exposure is analyzed according to three main components: strategic–functional, economic, and cultural. The strategic–functional component is related to the operational role of the building within urban and emergency systems [

2,

4,

25]; the economic component refers to the quantification of the exposed value, which is derived from parameters such as usable floor area, number of stories, and unit reconstruction costs [

4,

28,

42]; and the cultural component is based on the levels of protection and formal designation of the assets [

36,

43,

44]. The latter is particularly significant in the case of historic centers, since the loss or damage of a heritage asset entails not only economic consequences but also the impairment of the identity and symbolic value of the communities [

18].

In line with these approaches, more recent literature tends to relate the components of hazard, vulnerability, and exposure within multi-level models, in which risk is expressed through quantitative or semi-quantitative indicators calibrated to the scale of analysis. At the macro- and mesoscale, methods are based on risk matrices or on estimates of Expected Annual Losses (EALs) [

22,

34], supporting planning activities and the definition of intervention priorities [

45]. Other contributions [

26,

36] propose composite multi-hazard risk indices for the integrated management of infrastructures and urban fabrics, while quantitative approaches [

31,

46] correlate local susceptibility with vulnerability and the economic value of the historic built heritage. At the building and component scale, risk assessment is based on damage probability matrices [

45], calibrated vulnerability curves [

47], estimates of direct losses [

48], and kinematic or mechanical analyses of local failure mechanisms [

49,

50]. Although they differ in scale and purpose, these approaches point to a converging tendency toward the development of standardized and comparable models, capable of integrating heterogeneous data and providing a coherent and operational representation of risk.

Overall, the literature reports substantial advances in both mono-hazard vulnerability/risk assessment (seismic, flood, and landslide) and multi-hazard aggregation; however, key limitations persist regarding historic city centers. First, mono-hazard outputs often rely on hazard-specific metrics and spatial supports, which hampers cross-hazard comparability and impedes the development of unified, decision-oriented prioritization. Conversely, multi-hazard approaches frequently simplify complexity into thematic overlays or aggregate indices at the territorial scale, effectively decoupling the analysis from building aggregates and individual units. Furthermore, end-to-end procedures that operationalize the continuum from municipal screening to hotspot selection, and subsequent actionable prioritization across the macro- and microscale, remain limited, particularly when scale transitions must manage heterogeneous or partly aggregated datasets. Finally, exposure representation in historic fabrics remains methodologically sensitive, as conventional economic indicators fail to fully capture heritage-related values; moreover, interoperability is often reduced to co-visualization rather than achieved through semantically consistent relational structures that preserve traceability and enable dynamic, queryable building-scale records.

To overcome these limitations, the primary objective of this study is to develop and operationalize a multi-scale, end-to-end risk assessment workflow that transitions from territorial screening to a building-level prioritization in historic city centers.

To achieve this, the study pursues the following specific objectives:

Advancing an integrated methodology based on a relational, INSPIRE-aligned data architecture that addresses informational fragmentation and delivers interoperability-ready outputs toward GIS–BIM environments;

Implementing the workflow within an open-source GIS framework supported by automated procedures;

Integrating physical and morpho-settlement vulnerability indicators with socio-territorial components and heritage-related exposure dimensions, ensuring semantic consistency and traceability of sources and assumptions;

Ensuring functionality under variable levels of detail and data availability, enabling replication even in low-resource contexts, and validating the model through a real-world case study by producing decision-oriented outputs (hotspot identification and intervention prioritization) to support preventive planning and risk mitigation in vulnerable historic contexts.

To strengthen decision-oriented, multi-scale, multi-hazard assessment and improve interoperability readiness, the proposed approach contributes to the following main contributions:

INSPIRE-based multi-hazard information system: The information system adopts INSPIRE data models as a reference for the Natural Risk Zones component (hazard, exposure, and risk) and for the DBL, Buildings, Statistical Units, and Administrative Units themes. These datasets are harmonized and organized in a hierarchical, relational structure to ensure interoperability across scales and maintain semantic and informational consistency. In addition to geometry-focused GIS–BIM exchanges, the contribution lies in a DBL-ready relational structure that preserves cross-scale traceability (sources, methods, and confidence) and supports decision-oriented queries across the macro-, meso-, and microscale.

Multi-scale structure and variable levels of detail: The methodology supports different levels of detail by linking territorial screening to the highest available resolution, while remaining applicable under varying conditions of data completeness and spatial resolution. The key advancement is the explicit handling of heterogeneous and partly aggregated datasets, enabling consistent scale transitions and replicability in low-resource contexts.

End-to-end screening-to-prioritization logic: The workflow formalizes explicit scale transitions from municipal screening to hotspot identification and then to intervention ranking from the macro- to microscale, supported by stable relational links between units, aggregates, and buildings. This enables a traceable, decision-oriented prioritization chain that connects screening outputs to building-scale actions.

Automated and reproducible workflow: The procedures are automated using Python 3.12 scripts and open-source GIS tools, standardizing the analyses and improving repeatability by encoding key steps and parameters for consistent re-runs, easier updates, and reduced operator-dependent variability.

Overall, the proposed model harmonizes territorial- and building-scale data within a single evaluation framework, enabling the identification of intervention priorities and supporting the definition of risk-mitigation strategies in historic city centers. This paper presents the following: a detailed description of the proposed methodology, with reference to the multi-scale framework, the database structure, and the operational procedures implemented in the GIS environment (

Section 2); the application of the workflow and the presentation of the results obtained through its implementation on the case study (

Section 3); the discussion of the main findings and future developments of the work (

Section 4); and, finally, a summary of the study (

Section 5).

2. Materials and Methods

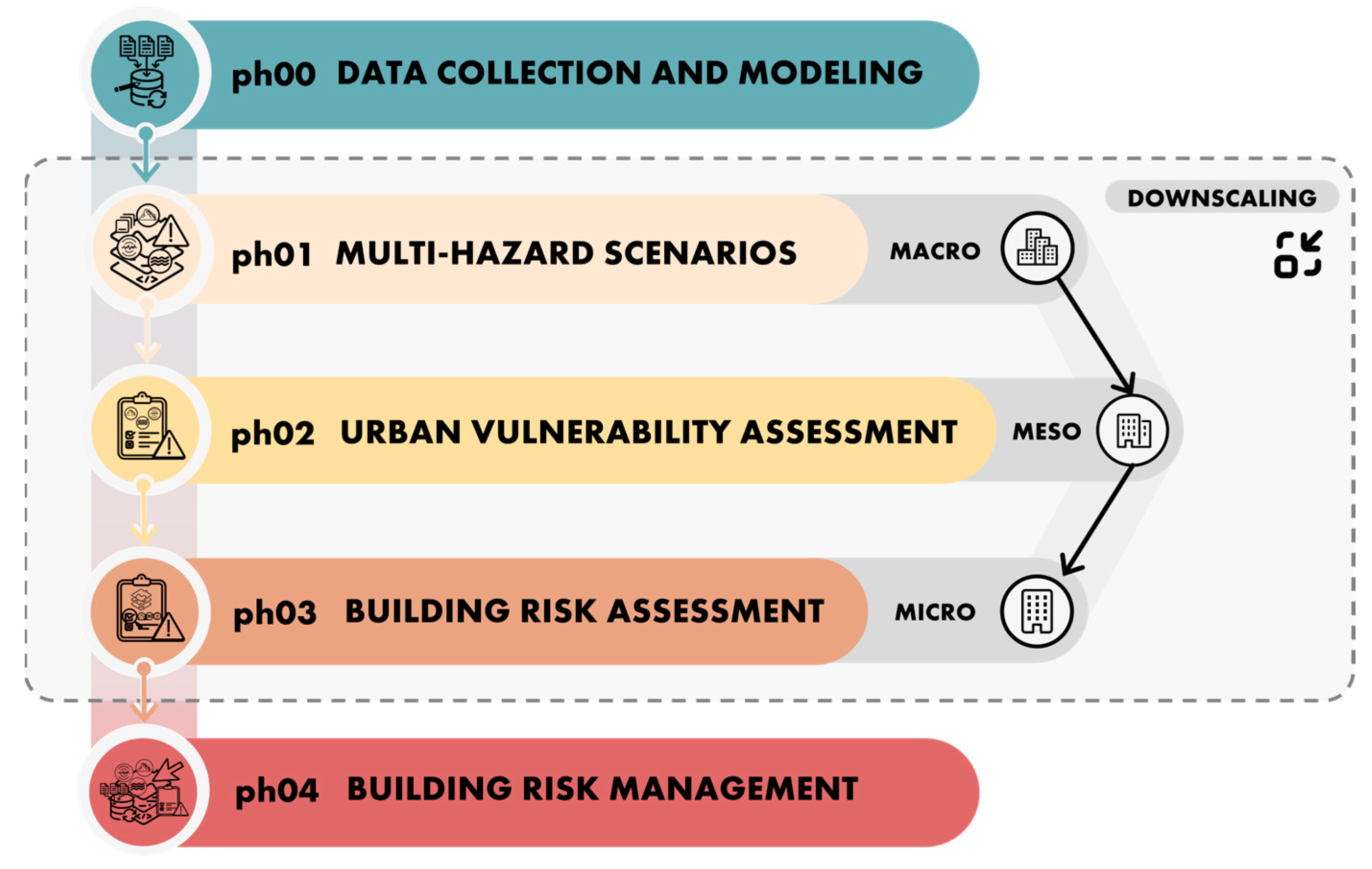

The research introduces a methodological framework for assessing the risk to which historic built heritage is exposed, structured for multi-level analyses, from hazard (H) to vulnerability/exposure (V/E) and finally risk (R), and for multi-scale analyses, from the macro territorial level to the meso census section (CS) scale and down to the microscale of the building aggregate (BA) and the single building (B), as shown in

Figure 1. Geometric data, vector and raster, along with non-geometric attributes, are stored in a centralized Relational Database Management System (RDBMS) with spatial extensions, to preserve the heterogeneity of the datasets, trace their provenance, and ensure the reproducibility of the analyses throughout the entire process [

51].

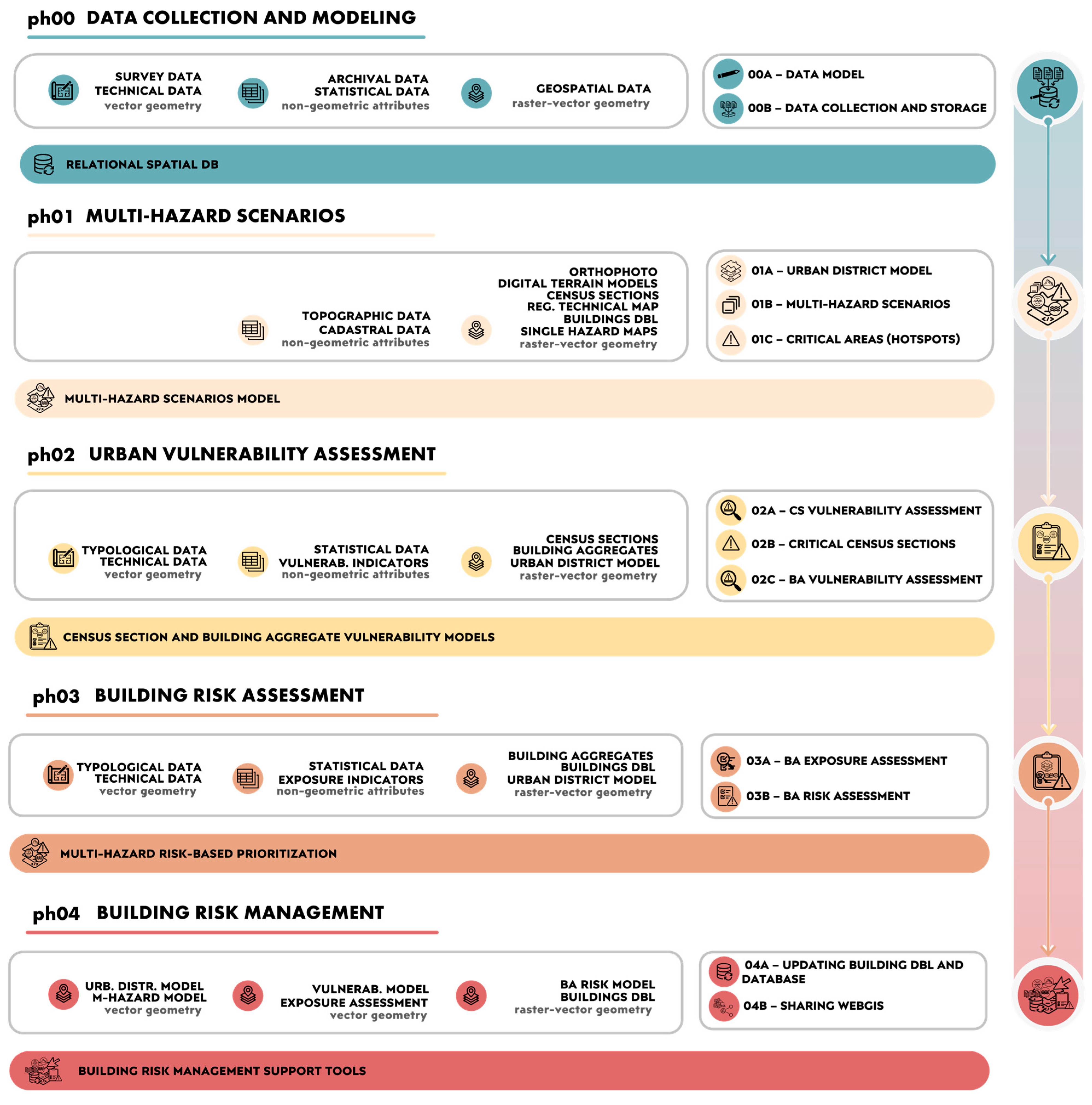

The methodology is articulated into five operational phases, each further subdivided into sub-phases, as illustrated in

Figure 2. The initial phase (ph00—Data Collection and Modeling) defines the data model and configures the system, consolidating sources and harmonizing reference systems, domains, and ontologies to construct a knowledge framework that is coherent across scales. In the GIS environment, the urban–district model is developed, and Multi-Hazard Scenarios are generated at the mesoscale, normalizing hazard maps onto a shared metric (ph01—Multi-Hazard Scenarios). The territory is discretized using a regular grid, and a Multi-Hazard Index (MHI) is estimated to classify each cell into four classes (from Low to Very High). The adopted thresholds follow [

18], who reclassify the MHI index (0–10) into four qualitative categories. The dominant hazard identified in the scenario guides the downscaling process and the selection of critical areas within an automated pipeline implemented in the GIS environment. Accordingly, subsequent vulnerability and exposure assessments are carried out only for the CS and BA scales located in areas classified as High or Very High hazard. The vulnerability of the historic built heritage is then assessed at the mesoscale of the CS and the microscale of the BA (ph02—Urban Vulnerability Assessment) through typological–constructional and morpho-settlement indicators which, once normalized and weighted, are aggregated into a vulnerability index (IV) and corresponding classes (from Low to Very High), supporting the identification of critical aggregates as the subsequent analysis unit. At the BA scale, exposure is estimated and risk is assessed (ph03—Building Risk Assessment) by combining H, V, and E in a multiplicative form with normalized factors (R = H × V × E), returning for each aggregate an exposure classification on four levels (from Low to Top Priority) and a risk gradation organized into six ordered classes (from Low Risk to Maximum Priority). These outputs support case comparison and the definition of intervention priorities. The final phase (ph04—Building Risk Management) brings the results back to the building scale, translating them into the compilation of information attributes that are consistent and enhanced with extensions dedicated to risk-related fields; at this stage, the dominant hazard, vulnerability outcomes at the CS and BA scales, exposure and risk values, and the adopted estimation methods and their confidence levels are recorded, together with elements that guide further investigation, monitoring, and preliminary intervention hypotheses. The database is progressively updated with the outputs of the analytical phases and prepared for dissemination through thematic maps and datasets, supporting monitoring, planning, and prioritization over time. The operational details (criteria for normalization and weighting, aggregation rules, precise definition of the indicators, and validation procedures) are provided in the following sections. To support the legibility of risk component maps and the results of the evaluation, all continuous indices used in the framework are discretized into a limited number of ordered classes using equal-interval thresholds between the minimum and maximum values recorded in the study area. This scheme preserves the relative ranking of units while providing a common legend across assessments.

2.1. Data Collection and Modeling and Multi-Hazard Scenarios

The first phase of the methodology (ph00—Data Collection and Modeling) defines the relational and geospatial data model used to represent, at the different scales of analysis, the territorial context and the public built heritage in accordance with the informational requirements of the assessment. In ph00A—Data Model, the logical and physical schema, shared domains and ontologies, as well as the declarative and procedural languages required for writing to a spatially enabled relational database, are specified. The structure is aligned with the relevant standards and regulatory guidelines and is designed for interoperability between GIS environments and BIM models for future integrations, thus ensuring a continuous information flow throughout the entire assessment process. Data obtained from surveys, physical archives, and open sources are collated and systematized, preserving the geometric component and harmonizing their semantics.

In defining the information schema, data on natural hazards, census sections, cadastral and topological references, as well as statistical datasets without geometry, are mapped to the relevant INSPIRE specifications to maintain semantic consistency between sources and ensure reproducibility. For the hazard, exposure, and risk themes, the Technical Guidelines of the Natural Risk Zones theme are adopted, recording the category and type of analysis, the acquisition method, the value with its unit of measure, and the validity range, together with the essential metadata, for each dataset. At the territorial scale, the Administrative Units theme describes the subdivision of the territory into administrative units and includes parameters such as name, nationalCode, nationalLevel, and nationalLevelName, ensuring the correct institutional hierarchy among municipal, supra-municipal, and regional levels. At the mesoscale, census sections are aligned with the structure of the Statistical Units theme, with attributes such as ReferencePeriod, StatisticalMeasureType, StatisticalDistributionType, and ObservationMethod, which allow specification of the associated statistical variables (population, density, building type, and socio-economic indicators) while maintaining a direct link to the previously defined administrative unit.

At the microscale, building aggregates and individual buildings are described according to the Buildings theme profile, extended with the conceptual model of the Digital Building Logbook. This enables the association, for each building or aggregate, of information on cadastral references, land use and occupancy, typological–constructional characteristics, structural and systems components, as well as relationships with higher information levels. This structure supports data traceability along the entire building life cycle, with dedicated fields for inspections, updates, and links to external resources (surveys, vulnerability forms, and photographic documentation). In ph00B—Data Collection and Storage, the system is then populated operationally: data from surveys, the cadaster, archives, and thematic maps produced by national and regional agencies are loaded into the database, preserving the existing geometries and attributes, and mappings to the INSPIRE dictionaries defined in ph00A are applied, thereby maintaining semantic continuity among heterogeneous sources. Access is regulated by profiles and roles to enable controlled updating and broad consultation by the stakeholders involved in risk management and mitigation. In this way, the database is prepared for uniform management of heterogeneous data and for consistently feeding the subsequent phases of the methodology.

Indeed, the following phase (ph01—Multi-Hazard Scenarios), which constructs Multi-Hazard Scenarios at the macroscale, is directly supplied by the data and models already systematized in the central database and linked to the GIS environment. In this context, the urban–district model is set up by overlaying the spatial layers that describe the territory (ph01A—Urban District Model), organized hierarchically: at the macroscale, municipal boundaries and census sections (CSs); at the mesoscale, building aggregates (BAs) based on regional technical cartography; and at the microscale, building footprints (B) based on cadastral records. Orthoimages and digital terrain models complete the framework, providing the morphology and topography required for a territorial representation consistent with the needs of the analysis.

Hazard maps (e.g., seismic, flood, landslide) available from competent authorities (expressed as physical quantities, delineations associated with return periods, or susceptibility classes) are transformed into a common metric in the range 0–10, following [

18], while preserving the original information and enabling the comparison of heterogeneous layers. The territory is then discretized into a regular grid, adopted as a “neutral” support for describing the spatial distribution of phenomena, with a fixed cell size of 40 × 40 m; this parameter can be adapted to settlement density and to the resolution of the sources. For each cell, a Multi-Hazard Index (MHI) is computed by means of qualitative overlay: in the absence of explicit interactions among hazards, the MHI is taken as the maximum of normalized values, in accordance with a worst-case assumption that prioritizes the rapid identification of critical areas. In parallel, the dominant hazard is determined, defined as the component that provides the prevailing contribution to MHI in the cell.

The results are reclassified into four qualitative levels (Low, Moderate, High, and Very High) and represented as a thematic map that, for each cell, reports the scores of individual hazards, the MHI, the assigned class, and the dominant hazard (ph01B—Multi-Hazard Scenarios). This framework guides scale reduction, allowing subsequent assessments to be focused on the most critical areas (ph01C—Critical Areas) with respect to the prevailing hazard and enabling the transfer of representative values to census units through zonal statistics operations, without repeating computations already performed.

In this framework, High and Very High MHI classes are used as a screening layer to delineate critical zones, which define the assessment area of the subsequent vulnerability, exposure, and risk assessments. The entire flow is automated through a Python pipeline, executable in the GIS environment, which constructs the grid over the study area, performs the intersections with the hazard layers, builds their union, and generates the thematic layer with the derived attributes. The integration of automated pipelines within the workflow ensures traceability and reproducibility, in line with the data architecture established in ph00.

2.2. Urban Vulnerability Assessment

Based on the results of ph01, which identify critical areas and the dominant hazard, the vulnerability assessment (ph02—Urban Vulnerability Assessment) proceeds in two sequential steps: first at the scale of census sections (CSs), and then at the scale of building aggregates (BAs). In both cases, rapid screening approaches are adopted, with assessments carried out in parallel and independently for each identified hazard. At the macroscale (CS), the assessment of the physical vulnerability of the historic built heritage is oriented toward a homogeneous and comparable analysis across areas, while remaining consistent with the informational constraints inherent to this scale.

In the field of seismic vulnerability assessment, simplified macro seismic approaches represent effective tools for rapid, large-scale analyses. Among these, the Level 1 RISK-UE model [

27] constitutes a consolidated methodology based on the association between structural typologies and reference vulnerability indices. These indices, based on statistical and archival parameters, are accompanied by variability ranges and extreme limits that describe their uncertainty. The correlation between the vulnerability index and macro seismic intensity, expressed according to the EMS-98 scale, allows the estimation of the expected mean damage for each building typology, together with the corresponding probability matrices.

The operational application of the method first requires the identification of the building typologies present in the territory through the analysis of statistical, cadastral, or historical data. The most representative vulnerability index is then assigned to each category. A second widely used approach, which can be adapted to the considered scale of analysis through appropriate simplifications, is represented by the Level II GNDT method [

28], configured according to a hybrid typological–index-based scheme. In its original formulation, the method involves the evaluation of eleven structural, geometric, and nonstructural parameters. The simplified version of the method allows the use of census data, such as structural typology, construction age, number of stories, and maintenance condition, to identify recurrent typologies and estimate a composite index of structural resistance.

In the field of flood hazard assessment, preliminary screening at the municipal or census section (CS) scale can be carried out by adopting rapid methods in which the historic built heritage is organized into homogeneous typological categories and subcategories [

29]. For each category, three elementary components (material, structure, and contents) are defined with reference to attributes such as prevalent construction techniques and materials, the presence of foundations/walls/basements, and the nature of internal elements. The three components are normalized and combined into an overall indicator, in which each component contributes differently according to specific weights.

The method developed by [

30] is specifically designed for the use of national census databases. Construction of the index starts from seven parameters that are representative of building behavior under flooding (including construction period, number of stories, structural system, and lithological/soil context) to which weights defined in [

30] are assigned. The weighted sum of the parameter scores defines the index, whose value is then normalized for subsequent classification.

At the macroscale, landslide vulnerability assessment methods employ approaches that relate intensity and resistance factors, whereby the expected structural resistance is compared with local susceptibility or intensity, resulting in homogeneous maps that are useful for isolating hotspots, even in the absence of dense historical records. The method developed by [

31] evaluates physical vulnerability as the joint outcome of an indicator of landslide intensity on the built environment and the average load-bearing capacity of the building assets within each census section. Intensity is reconstructed as the intersection between the built heritage and susceptible areas, by overlaying building footprints with susceptibility maps and weighting the classes present within each polygon, and then normalizing the resulting values into four classes. Load-bearing capacity is instead calculated from parameters that can be retrieved at the census section scale, such as structural typology, maintenance condition, and number of stories. The contingency matrix resulting from the intersection of the two indicators yields, for each section, a discrete vulnerability class, which is converted into a normalized value (0–1). The approach proposed by [

32] makes it possible to measure the intrinsic propensity of buildings to damage independently of the specific magnitude of the event, estimating susceptibility as an aggregate index in the absence of quantitative hazard evaluations. The parameters used are structural and morphological characteristics that can be retrieved systematically (construction typology, height and number of stories, configuration and size of openings, orientation with respect to the slope, and maintenance condition), which are converted to standardized values between 0 and 1 and aggregated using an unweighted rule, thus obtaining, for each section, a susceptibility index free from implicit weightings. The resulting susceptibility surface and associated indices can be used directly to derive a vulnerability estimate.

The vulnerability indices thus obtained are normalized and classified into four levels (Low, Moderate, High, and Very High) according to the general classification scheme described above, resulting in a vulnerability distribution map at the census section scale (02A—CS Vulnerability Assessment), which supports the identification of priority areas for detailed analyses (02B—Critical Census Sections).

Approaches aimed at assessment at the scale of urban aggregates require a more in-depth reading of the historic built heritage, including typological–constructional and morpho-settlement attributes obtained from surveys and archival data.

In the case of seismic hazard, the rapid screening methods developed by [

33,

34] are both based on the vulnerability index approach, in semantic continuity with the GNDT metric and adapted and calibrated for specific purposes and contexts. The first approach is conceived as an extension of the GNDT method, incorporating interaction effects between structural units within the same aggregate. Five additional parameters are introduced to capture the combined action of contiguous units, typological–constructional irregularities, and possible local mechanisms induced by contact between adjacent building bodies. The second approach, which retains a lower level of detail than the first, is likewise configured as a hybrid version of the Level II GNDT model, but in simplified form. The logic is typological–index-based: information on the historic built heritage (derived from inventories and aggregated data) is translated into a limited set of empirical parameters as a function of structural typology (URM, unreinforced masonry; RC, reinforced concrete), calibrated on post-earthquake damage observations and adapted to the local fabric by introducing variables related to building position and interaction between adjacent structures. Both approaches adopt a common method for calculating the vulnerability index, based on a weighted sum of the parameters, which is then normalized and divided into four risk classes. Each parameter is associated with a specific score, and the assigned values reflect the relative contribution of each aspect, modulated by a predefined weight.

Flood vulnerability assessment relies on approaches that employ detailed parameters, allowing a more site-specific and less generalized reading of built heritage and contributing to the definition of representative aggregate indices. Rapid screening methods, such as those shown in [

35,

36], exhibit similarities, as they represent specific or extended versions of [

37]. In the first case, the methodological approach is developed for the assessment of historic urban centers of heritage value and involves decomposing vulnerability into an exposure component, which describes the relationship between the building and flood flow (e.g., façade orientation, configuration of openings), and a sensitivity component, which summarizes intrinsic characteristics such as material, number of stories, conservation state, age, and protection status. The two components are normalized and integrated into a final composite index. In the second case, an extended vulnerability module is proposed, maintaining the decomposition into sensitivity and exposure factors while increasing the number of parameters. Seven sensitivity parameters are evaluated, including conservation state, type/condition of window and door frames, and finally façade finishing materials. In addition, three exposure factors are examined: land use, heritage value, and surface condition. The index resulting from the aggregation of the two components is then normalized and reclassified into four classes.

In the context of vulnerability associated with landslide phenomena, approaches based on composite indicators are more appropriate for analyses at a broad territorial scale, whereas when the investigation focuses on more detailed scales, such as the urban aggregate or the individual building, quantitative mechanics-based methodologies are adopted, providing context-specific evaluations of instability conditions. For example, [

38] develops an intensity–resistance model for rapid landslides, in which vulnerability is estimated as the outcome of the interaction between event intensity and the load-bearing capacity of the structure, which depends on the built environment. Intensity is expressed through kinematic and geometric properties of the flow, including a debris-depth factor, while resistance is parameterized based on four factors (foundation depth, structural type, maintenance condition, and height) so that “debris-depth–foundation-depth” pairs allow the derivation of coherent and comparable vulnerability values.

For slow-moving landslides, the analysis adopts a mechanical perspective, examining the physical response of buildings to the thrust force exerted by the landslide on the foundation. In the approach proposed by [

39], intensity is represented by the slope safety factor at the foundation location, derived from geotechnical analyses or official mapping. The response of the building is modeled in terms of its tendency to tilt, with reference to the geometric parameters of the foundation (length, width, and depth), thereby avoiding complex modeling while capturing the order of magnitude of the effect. In this case as well, vulnerability is evaluated with respect to the ratio between the actual tilt experienced by the building due to the residual thrust force of the landslide (computed at the foundation) and the threshold tilt value for buildings at risk.

To construct the vulnerability distribution map at the aggregate scale, the outputs of the composite index methods are normalized and classified into four levels (Low, Moderate, High, and Very High) according to the general classification scheme adopted in this study, thereby identifying the most critical aggregates (ph02C—BA Vulnerability Assessment).

2.3. Building Risk Assessment and Risk Management

The risk estimation phase (ph03—Building Risk Assessment) marks the progressive shift in scale from the aggregate to the single building. Exposure is quantified as the sum of three independent components analyzed separately: strategic–functional (sf), economic (eco), and cultural (ch). The strategic–functional component is estimated based on the building’s function and operational role in emergency management, whereas the economic component derives from quantifying the exposed value through usable floor area per story, number of stories, and unit reconstruction cost, where the available or market value is expressed in €/m2. The cultural component is obtained from the inventory of formally recognized protection levels. The overall exposure indicator (E) is defined as the sum of the three contributions, each normalized and discretized into four ordered levels, and is then classified into four categories (Low, Moderate, High, and Very High), resulting in an exposure thematic map at the aggregate scale (ph03A—BA Exposure Assessment).

The final phase of the assessment process consistently brings together the three analytical axes (hazard, vulnerability, and exposure) into a single operational representation of risk. The classes produced in the previous phases are expressed on a common four-level scale for H, V, and E and combined through a matrix-based scheme, in line with the definition of risk, R = H × V × E. The outcome is a six-level gradation (from Low Risk to Maximum Priority) that expresses the potential damage intensity and is represented in a final thematic map. From an operational perspective, the risk map directly supports the definition of mitigation priorities, the scheduling of interventions, and the design of targeted monitoring measures (ph03B—BA Risk Assessment). Integration with the relational database ensures that all elements required for risk computation (values and classes of H, V, and E, methods employed, parameters, and sources) are accessible to the stakeholders and platforms involved.

The subsequent phase of the workflow (ph04—Building Risk Management) extends the process from the evaluative to the management dimension, translating the results of risk estimation into operational tools for the consultation, updating, and sharing of data at the building scale. It enables the transfer of analytical results into management information tools, ensuring consistency between the data produced in the different phases of the workflow and their subsequent visualization for updating and control activities.

In module ph04A—Updating Buildings DBL and Database, the results of the assessment process are transferred to the building scale by compiling the DBL, for buildings classified as Priority or Maximum Priority in risk maps and updating the relational database. In this phase, the information produced at the different levels of analysis is organized within a unified structure, maintaining consistency across scales and ensuring that it can be jointly queried within the information system. For each building, the cadastral footprint is used as the spatial reference, ensuring correspondence with aggregates and census sections through the two unique keys adopted in the process (classRef for building aggregates and inspireId for individual buildings). This relational structure, based on one-to-many relationships and foreign keys as defined in ph00, supports the automatic integration of data from the different analytical phases into the layer, making them immediately correlated and viewable at the building scale.

DBL represents the final information layer of the system and provides a consistent transfer of the data organized in the relational database to the building scale, preserving continuity across the different scales of analysis.

In module ph04B—Sharing WebGIS, the results organized in the database are published and exposed through a WebGIS platform used for visualizing and navigating data at the different scales of analysis. The platform acts as the output interface of the information system and provides interactive access to spatial content and descriptive attributes. The information layers are published while preserving the hierarchical structure of the database to maintain the relationships between buildings, aggregates, and census units. Features are represented as thematic layers that can be overlaid and queried against descriptive parameters and analysis results, in accordance with the multi-scale logic of the model. The system supports the visualization of information stored in related tables, the consultation of descriptive records, and the use of search and filtering functions based on attributes. Vector data can be provided for downloading or querying in formats compliant with INSPIRE and OGC standards (GeoJSON, GML, and CSV), ensuring structural consistency and the possibility of integration with other information systems.

3. Results

To support the demonstration and validation of the described methodology, the following results are presented from its application to the case study of the municipality of Montalbano Jonico in Southern Italy. It is a small town located on the edge of a clay plateau dissected by deeply incised badlands and characterized by a compact medieval urban fabric (

Figure 3). The area is affected by widespread geomorphological instability due to the predominantly clayey lithology and the presence of Pliocene and Pleistocene deposits that are prone to flow-like phenomena [

52]. Numerous documented landslide events throughout the twentieth century, and in particular the episodes of 1970–1971, caused severe damage to buildings and urban infrastructure, ultimately leading to the evacuation and relocation of residential areas situated in the most unstable zones (Decree No. 1166/1971). Several buildings in the affected historic quarters are still uninhabitable or walled up, reflecting a persistent condition of criticality which, together with progressive abandonment, has fostered urban decay and a loss of functional continuity in the built fabric. In addition, the indirect effects of the 1980 Irpinia earthquake further exacerbated the vulnerability of part of the historic built heritage, providing an appropriate context for testing a multi-hazard approach capable of integrating different components of instability within a single analytical system.

3.1. Datasets Integration and Multi-Hazard Scenarios

In line with the workflow described in

Section 2.1, the first application phase concerned the construction of the relational and geospatial data model, aimed at representing, at the different scales of analysis, the territorial context and the historic built heritage of the municipality of Montalbano Jonico in alignment with the informational requirements of the risk analysis. The information model was implemented in a PostgreSQL/PostGIS environment, following a relational structure compliant with the INSPIRE thematic profiles, as described in the methodology (ph00A—Data Model). For each level of analysis, specific feature layers were created that preserve both the original geometry and the semantics of the reference schema. All layers are connected through association relationships that support a hierarchical and consistent reading of territorial and thematic data (

Table 1).

At the territorial scale, the Administrative Units layer defines the administrative profile of the municipality, with unique identification codes (nationalCode = 077016, corresponding to a 3rd Order Administrative Unit) and territorial classification parameters [

53]. At the mesoscale, the Statistical Units theme identifies the 15 census sections (CSs) of the municipality, derived from the 2011 ISTAT Census [

54], specifying for each the statistical method employed (combination of methods), the type of measure (count), and the type of distribution (frequency distribution). These units are associated with the main aggregated building and demographic attributes (construction typologies, number of stories, conservation state, and construction year).

At the microscale, building aggregates (BAs) inherit their geometry from the Regional Technical Map [

55] and their semantics from the Buildings theme, including cadastral references and land use/occupancy for each aggregate. The extension to the Digital Building Logbook allows representation at the scale of the single building (B) and real estate unit, using the geometric footprint derived from the cadastral webmap service [

56]. The logical implementation schema is unified but structured across multiple levels: each layer maintains a link to the upper scale through three identifiers ensuring traceability of spatial and registry relationships among entities: statisticalCode (census sections), classRef (building aggregates), and inspireId (buildings). Among the thematic layers, the Digital Terrain Model (DTM) [

57] and the orthophoto [

58], both raster datasets, complete the territorial characterization from a morphological and visual standpoint, providing elevation information, slopes, and elements useful for photointerpretation of geomorphological and settlement conditions.

The seismic, flood, and landslide hazard layers integrated into the database retain the original geometries of the source datasets, while the semantic component was reclassified in accordance with the Technical Guidelines of the Natural Risk Zones theme, specifying for each layer attributes such as the assessment method, qualitative class, and validity date. Seismic hazard was acquired from the official data provided by the Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia (INGV) [

59], covering the entire municipal territory and representing peak ground acceleration (PGA) values for a 50-year return period. For flood and landslide hazards, influence areas were derived from the Piano per l’Assetto Idrogeologico (PAI) [

60,

61] prepared by the Autorità di Bacino Distrettuale dell’Appennino Meridionale, which defines flood hazard scenarios for different return periods and landslide hazard classes, identifying sectors affected by active, dormant, or potential instability.

Table 1.

Input datasets and their role in the multi-hazard, multi-scale risk assessment for Montalbano Jonico.

Table 1.

Input datasets and their role in the multi-hazard, multi-scale risk assessment for Montalbano Jonico.

| Input Data | Description | Analysis Level | Format | Accessibility |

|---|

| Administrative Units [53] | Municipal administrative boundaries | ph01—Multi-Hazard Scenarios | Vector (SHP) | Open |

| Census sections (ISTAT) [54] | Socio-demographic

and housing variables at the sub-municipal scale | ph02—Urban Vulnerability Assessment | Vector (SHP) | Open |

Aggregate of

Building footprints (CTR) [55] | Spatial geometry of buildings and

structural typology | ph02—Urban Vulnerability Assessment

ph03—Building Risk Assessment | Vector (SHP) | Open |

| Cadastral map [56] | Property parcels, boundaries, and legal land divisions | ph03—Building Risk Assessment

ph04—Building Risk Management | Raster (WMS) | Open,

read-only |

| Flood hazard maps (PAI–AdB) [60]; | Flood-prone areas and water depth for low | ph01—Multi-Hazard Scenarios | Vector (SHP) | Open |

| Landslide hazard maps (PAI–AdB) [61] | Landslide hazard

classes (P1–P4) | ph01—Multi-Hazard Scenarios | Vector (SHP) | Open |

Seismic hazard map

(INGV) [59] | Peak ground acceleration (PGA) for a

50-year return period | ph01—Multi-Hazard Scenarios | Raster (TIFF)

Vectorized (SHP) | Open,

read-only |

| Heritage and land use data (MiC–BDU) [62] | Cultural and functional value of buildings and land cover | ph03—Building Risk Assessment | Vector (SHP) | Open |

| Market value database (OMI) [63] | Property and assets

market value | ph03—Building Risk Assessment | Vector (SHP) | Open |

| Digital Terrain Model (DTM) [57] | Elevation and

slope parameters | ph01—Multi-Hazard Scenarios

ph04—Building Risk Management | Raster (GeoTIFF) | Open |

| Orthophoto [58] | Orthorectified

aerial image | ph01—Multi-Hazard Scenarios

ph04—Building Risk Management | Raster (GeoTIFF) | Open |

In addition, to prepare supporting documents for risk assessment, the layers from the Regional Landscape Plan [

62] were loaded into the database and used to identify monumental assets and protection areas relevant for the cultural exposure component; the OMI [

63] zones, with associated market value ranges, were used for estimating the economic component of exposure. The integration of these datasets resulted in a consistent and integrated cartographic base ready for the implementation of subsequent multi-hazard, vulnerability, and exposure analyses at the urban and aggregate scales (ph00B). All input datasets are summarized in

Table 1. The urban–district model was developed in QGIS© 3.40, using the recorded geometric and informational base as the reference framework for constructing Multi-Hazard Scenarios at the territorial and urban scales. The model was structured through the spatial overlay of the geometric–informational layers stored in the database, which is directly connected to the software, including both geospatial data and nonspatial attribute data. Each scale of analysis is associated with a specific layer, and the project is completed by terrain models and individual hazard maps, enabling a hierarchical and continuous reading of the information (ph01A).

For the construction of the Multi-Hazard Scenarios (ph01B), the seismic, flood, and landslide hazard maps were incorporated into the project and organized following the data structure defined in the preceding phase (ph00). Harmonizing the source data with the fields and domains of the database defined for the hazard layers required normalizing the hazard values onto a numerical scale from 1 to 10, consistent with the adopted methodology, to enable comparison among the different risk components.

The normalized hazard values were then reclassified into qualitative classes derived from the standardized ranges and from the thresholds established for each type of event. The analysis highlighted, for the Montalbano Jonico area, a moderate level of seismic hazard, a medium-to-high level of landslide hazard concentrated along the badland slopes bordering the historic center, and a medium level of flood hazard associated with valley areas and valley-bottom segments potentially subject to flooding.

In addition, an ad hoc Python pipeline was developed in the QGIS Processing Toolbox, which, starting from the individual hazard maps together with the Administrative Units layer, automatically defines the Multi-Hazard Scenarios within the GIS project. When the script is executed, a 40 × 40 m square grid is generated and adopted as a neutral analysis unit for the municipal territory.

Within each cell, the normalized values of the three hazard components are computed, and, for synthesis, the Multi-Hazard Index (MHI) is derived as the maximum of the three components, according to a conservative worst-case criterion.

At the same time, for each cell, the dominant hazard type and the corresponding qualitative intensity class are determined, providing a continuous and integrated spatial representation of multi-hazard levels.

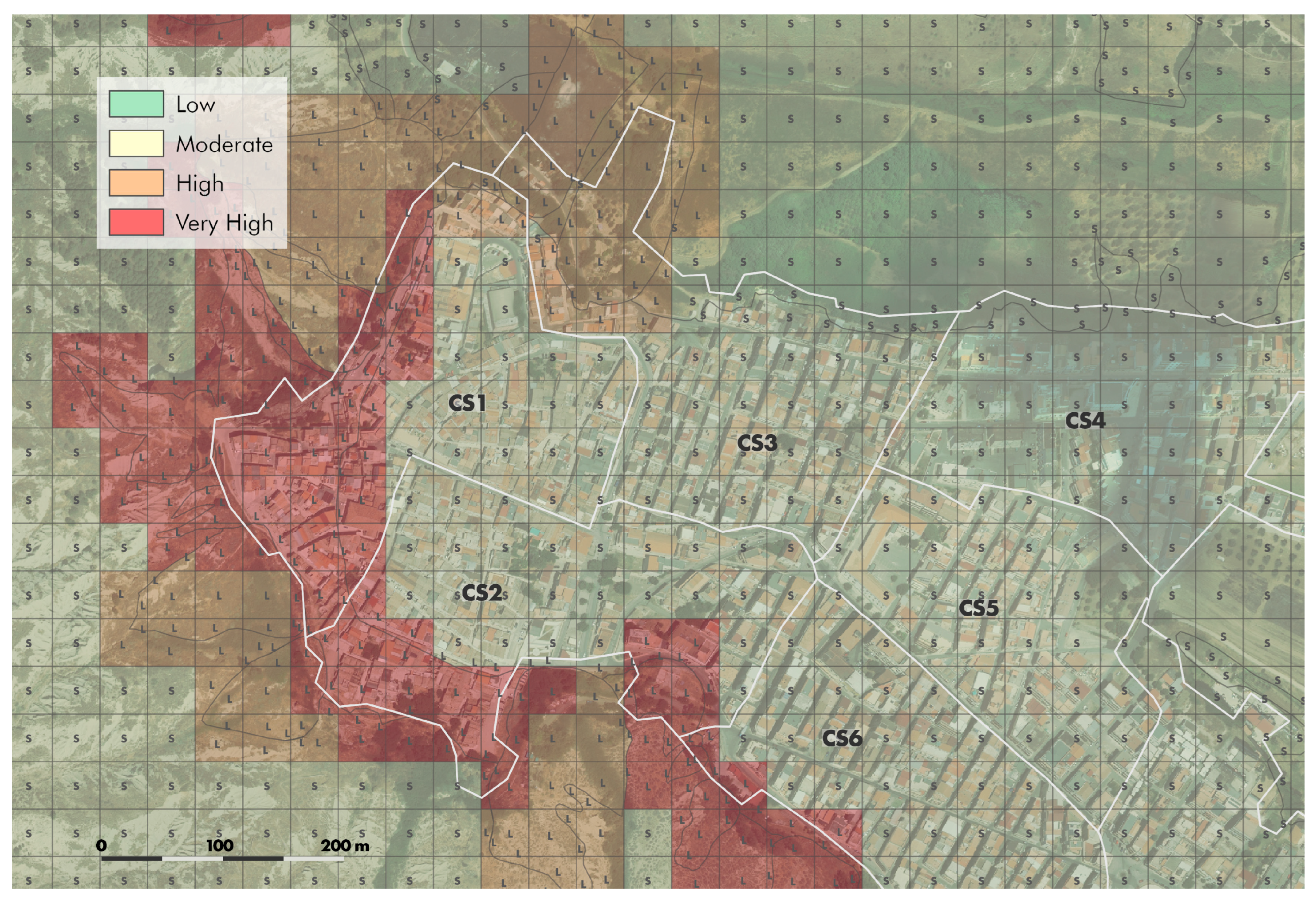

The highest index values, shown in red, are concentrated along the western and southwestern edge of the historic center, coinciding with the areas already classified as P3–P4 landslide hazard in the PAI and with documented historical instability events. Intermediate hazard classes are distributed along the transition zones between the built-up area and agricultural slopes, highlighting morphologically sensitive but not yet critical conditions. In the northeastern sectors and in the valley-bottom areas, index values are moderate and primarily influenced by flood hazards associated with accumulation zones and minor drainage lines. The areas at highest hazard are concentrated along the badland edge of the historic center, as shown in

Figure 4, which are affected by both seismic and landslide hazards and correspond to census sections CS1, CS2, and CS3, which are identified as priority hotspots for subsequent vulnerability and risk assessment (ph01C).

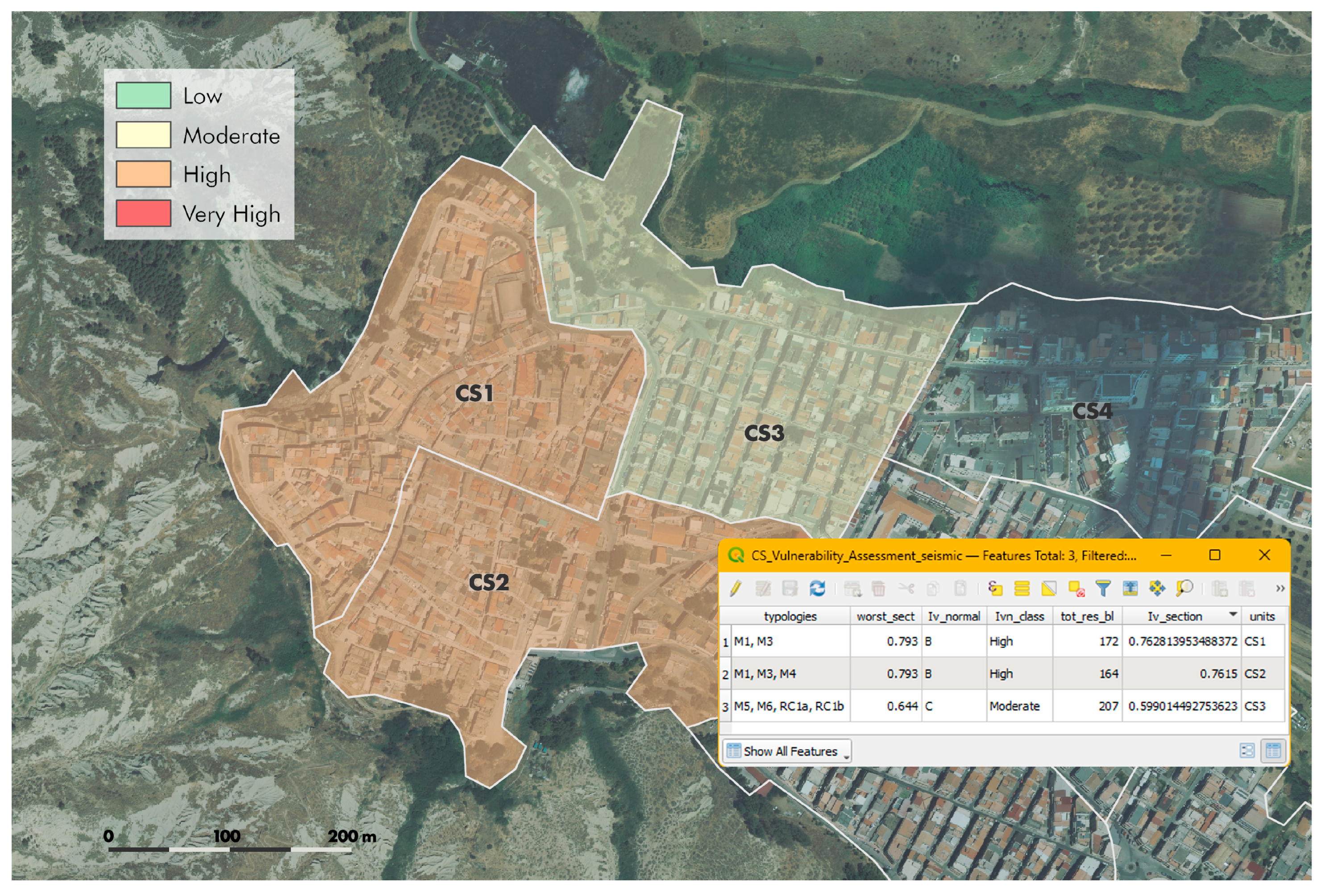

3.2. Seismic Urban Vulnerability Assessment

In line with the results of the previous phase, a vulnerability assessment was carried out through two parallel and complementary analyses for seismic and landslide hazards, applied at two investigation scales, census section (CS) and building aggregate (BA), as described in

Section 2.2 of the methodology.

For seismic vulnerability at the CS scale, the Level 1 RISK-UE model [

27] was adopted. This method allows the use of ISTAT data associated with individual census sections, in this case for residential buildings, with appropriate simplifications related to the aggregated nature of the available data. In the three census sections under analysis, residential masonry buildings account for almost the entire built heritage; however, it was necessary to rely on additional statistical indicators to further disaggregate the data and enable the application of the method. ISTAT provides an online resource with aggregated statistical risk indicators for Italian municipalities [

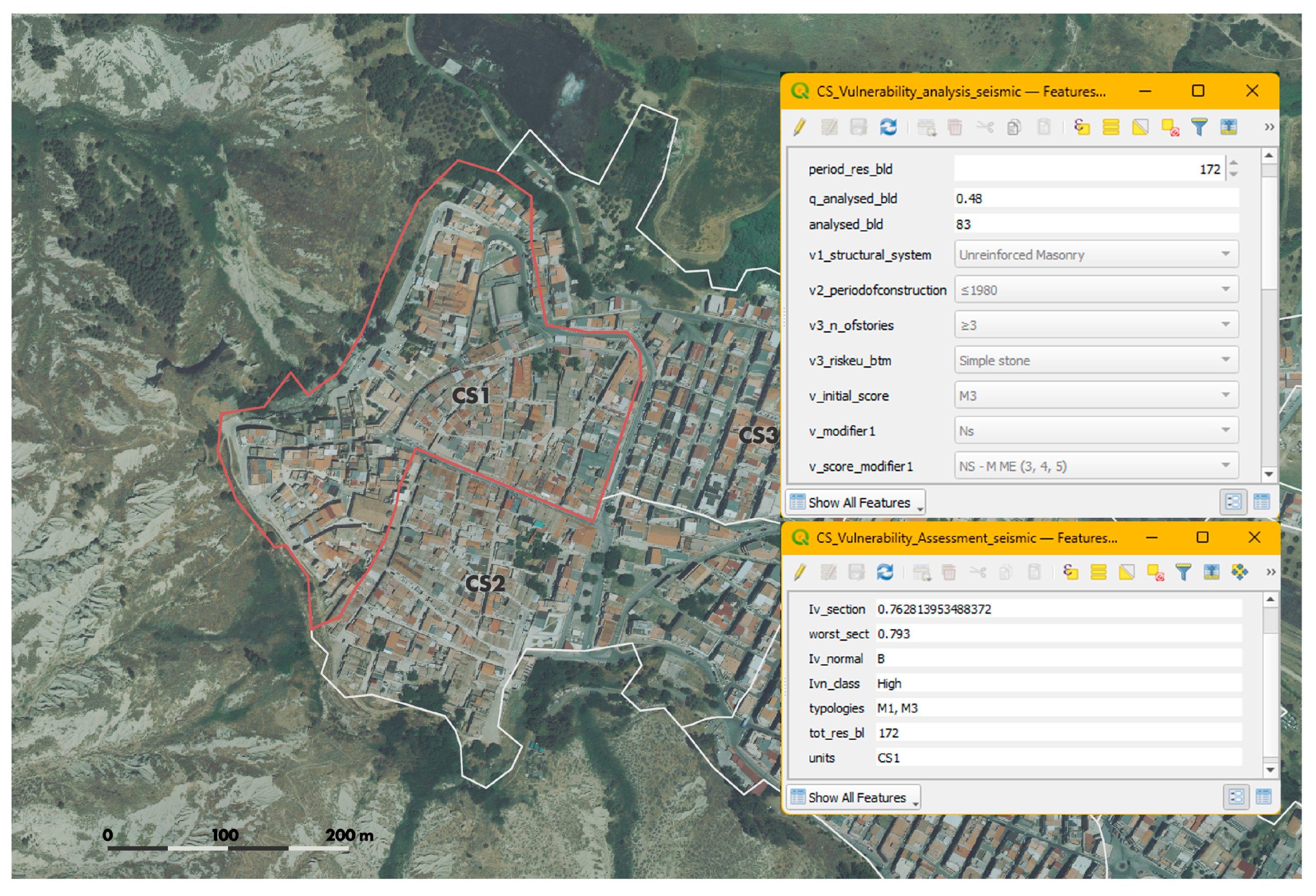

64]. Some of these indicators relate the number of residential buildings by construction period to the number of above-ground stories. The resulting data were transformed for use in the method through suitable calculations, converting percentage shares into absolute counts. A further simplification was introduced by aggregating the limited number of buildings with structural systems other than masonry or reinforced concrete into the prevailing structural category, which in this case is masonry. The processed data enabled the identification of fourteen building typology classes, based on structural system, construction period, and number of stories, of which ten are masonry types (M) and four are reinforced concrete types (RC). The typologies are distributed as follows: in the first census section, classes M1 and M3 prevail, corresponding to masonry buildings with 1–2 and ≥3 stories constructed before 1980; in the second section, the same typologies are found for periods before 1980 and 1981–2005, with variations in the number of stories; in the third section, classes M5–M6 and RC1a–RC1b are present, referring to buildings with two or more stories constructed both before and after 1980. Overall, historic masonry buildings predominate within the historic core, whereas reinforced concrete structures are more prevalent in the more recent and peripheral urban sectors. An example of the prevalent typological class M3 in census section CS1 is shown in

Figure 5.

For each typology class, a base vulnerability index value was assigned, which, combined additively with specific influencing factors, such as the number of stories used in this application, yields the final vulnerability index. To compute the vulnerability index for each census section (ph02A), an automated Python pipeline was developed and integrated into the Processing Toolbox. Starting from the typology classes identified in the analysis layer, the script calculates and maps, for each census section, seismic vulnerability as a weighted average with respect to the total number of residential buildings in the section (Iv_section), the corresponding worst-case value (worst_section), and the associated class on the EMS-98 macro seismic scale.

The results classify sections CS1 and CS2 as high vulnerability and section CS3 as moderate vulnerability; consequently, the subsequent aggregate-scale analysis was carried out on the first two sections (ph02B). The spatial distribution of seismic vulnerability at the census section scale is illustrated in

Figure 6.

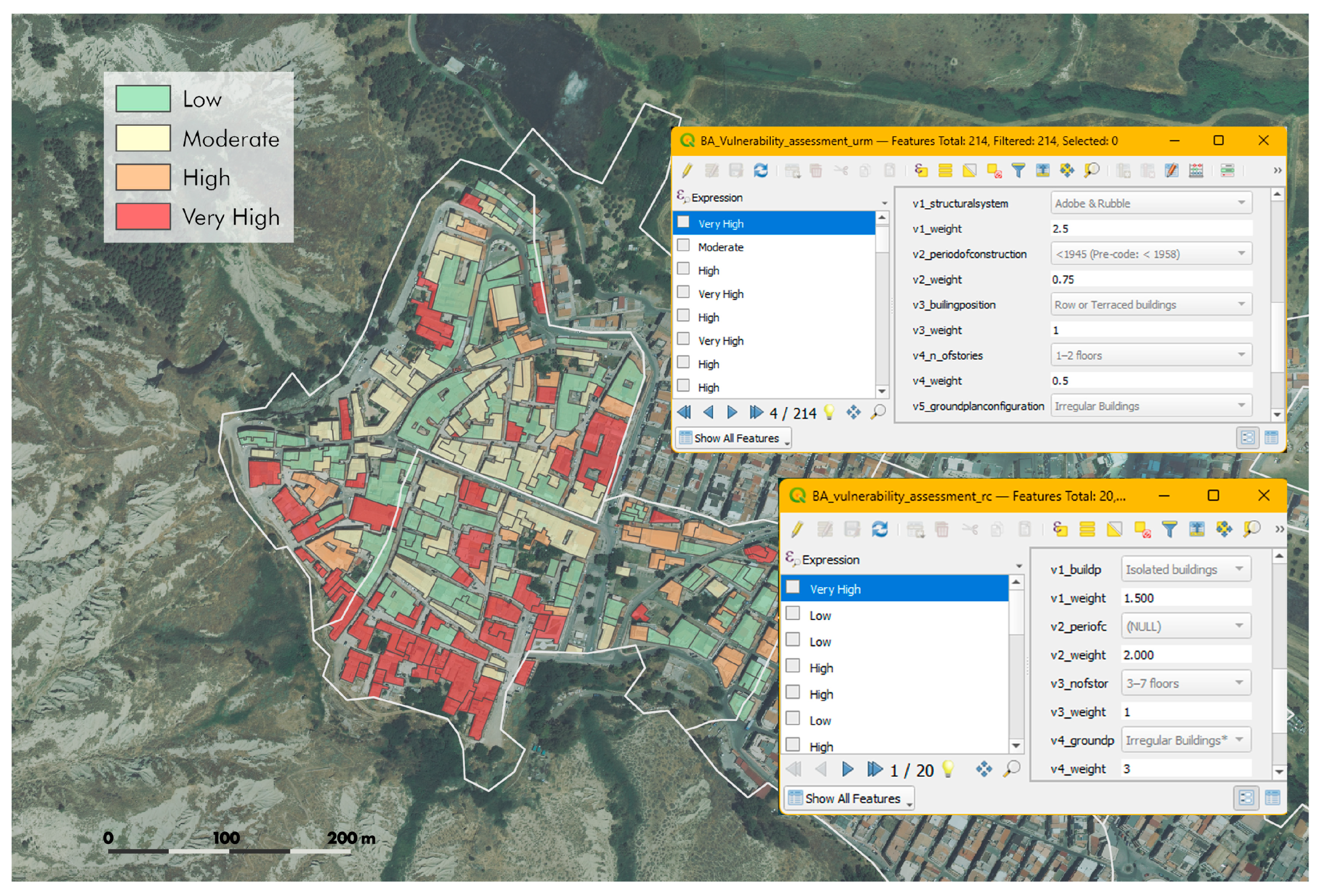

For seismic vulnerability assessment at the building aggregate (BA) scale, rapid screening methods based on aggregate indices calibrated for historic urban contexts were adopted [

34]. Analysis of the data for the first two census sections (CS1, CS2) showed that no framed reinforced concrete (RC) buildings were present; consequently, the assessment was initially carried out using the indicators defined for unreinforced masonry (URM) typologies only. The assignment of typological–constructional attributes (structural typology, construction period, number of stories, plan regularity, conservation state, interaction, and position within the block) was performed in accordance with the reference methodology by integrating cadastral data, archival surveys, and photointerpretation checks on orthophotos and Google Street View

® imagery. The reference geometry was given by the building aggregates identified in the Regional Technical Map (CTR), which is incorporated into the geospatial database. However, a more detailed examination of CS2 revealed the presence of some RC structures, which required a parallel analysis using the specific indicators for RC typologies in that area. Overall, approximately 91% of the built heritage was classified as URM, while the remaining 9% belonged to the RC typology. Among RC structures, most were constructed between 1961 and 1980, whereas more than 80% of masonry buildings date back to before 1945, reflecting the historical stratification and age of the fabric built in the settlement. For the computation of the vulnerability index, a Python pipeline was developed and integrated into the QGIS toolbox. This script reads the layer containing the parameters and geometries used in the analysis and computes the index from the attribute values of the parameters to which reference-based weights are assigned according to [

34]. The index is obtained as a weighted sum, and then normalized to a 0–100 scale (Iv_normal) and divided into four qualitative classes (Iv_class), in line with the methodology. The results in

Figure 7 show medium-to-high vulnerability values in the western sector of the historic center, due to the oldest and most irregular masonry aggregates; overall, 100/234 BA (42.8%) fall in the High–Very High vulnerability classes (

Table 2), while the more recent expansion areas show moderate or low values, which is consistent with the presence of buildings with greater structural and morphological regularity (ph02C).

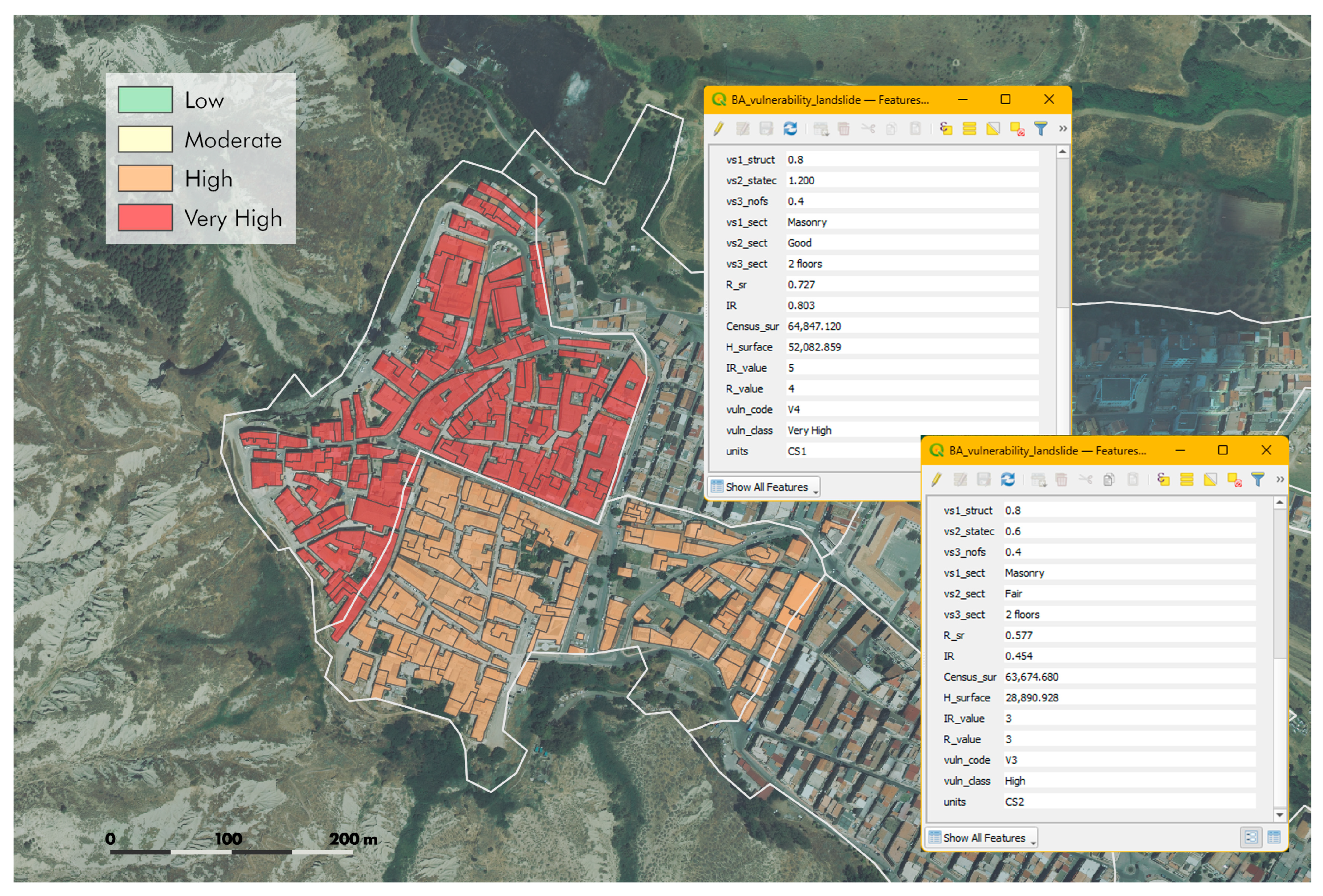

3.3. Landslide Urban Vulnerability Assessment

For landslide vulnerability at the census section (CS) scale, the method proposed by [

31] was adopted, as it is specifically designed for aggregated and statistical data. Unlike the seismic vulnerability case, typological classes were defined from the average values of the available data, in line with the approach proposed in the literature. The parameters considered were structural typology, conservation state, and number of stories, which are used to compute structural resistance as one of the components of the vulnerability index in the adopted method.

The resulting typological classes differ between the two census sections most exposed to landslide hazard (CS1 and CS2), mainly in terms of conservation state, which is, on average, worse in CS2 than in CS1. In both sections, masonry is the prevailing structural typology, with an average of two above-ground stories, and an overall structural resistance value ranging from 0.727 in CS1 to 0.577 in CS2. In parallel, the second component (Impact Ratio) was calculated as the ratio between the area affected by landslide hazard and the effective area of the census section. Vulnerability is then obtained from a contingency matrix between structural resistance and Impact Ratio, computed through an ad hoc Python pipeline implemented in the QGIS toolbox (ph02A).

For Montalbano Jonico, the results (

Figure 8) show that CS1 is more affected by landslide hazard due to the presence of badland slopes directly adjacent to the built-up area (ph02B), yielding a vulnerability value in the Very High class, while CS2 falls into the High class. Unlike the approach adopted for seismic vulnerability, in this case, the transition from the census section scale to the aggregate scale is performed by directly assigning the mesoscale vulnerability value to all aggregates belonging to each section (ph02C).

3.4. Multi-Hazard Risk-Based Prioritization and WebGIS Decision-Support Platform

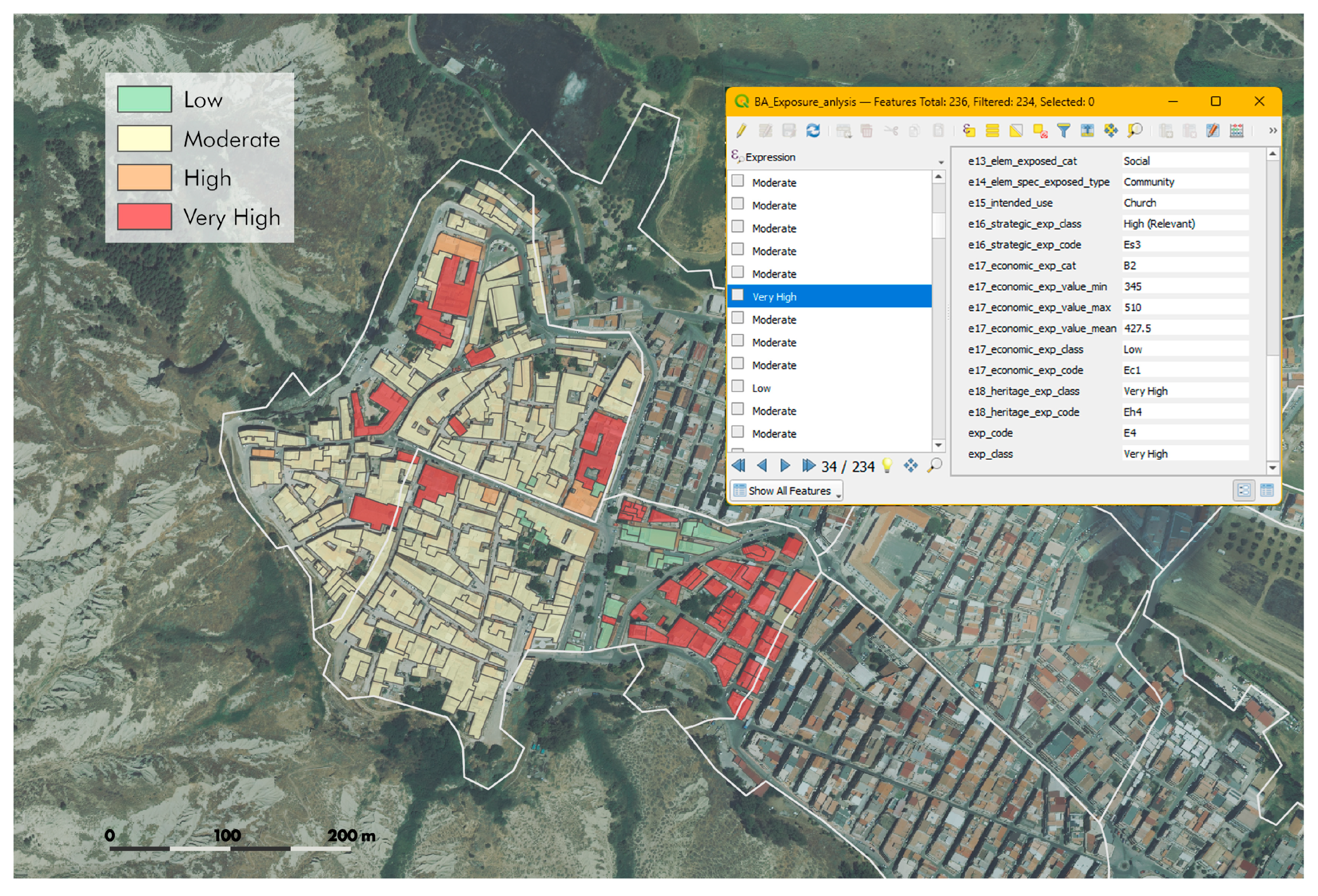

During the final phase, an exposure assessment was carried out, followed by the development of risk maps, using a common and parallel methodological setup for the seismic and landslide scenarios.

Exposure was analyzed as a cross-cutting component for both hazard domains, adopting an integrated approach that considers the strategic (E_strategic), economic (E_economic), and cultural (E_heritage) value of the building assets (ph03A).

The data used to define exposure were derived from institutional information bases and reference thematic cartography, including the Regional Technical Map, used for the functional classification and land use/occupancy of buildings; the Osservatorio del Mercato Immobiliare (OMI), Italian real-estate market database, from which updated average market values were extracted for the corresponding territorial sectors; and the Regional Landscape Plan, used to identify buildings under cultural protection or formal heritage constraints.

All datasets were harmonized with the INSPIRE Natural Risk Zones data model, ensuring semantic consistency with the hazard and vulnerability layers.

Regarding the strategic–functional value, following the criteria adopted in the Municipal Civil Protection Plan [

65], the analyzed building assets consist predominantly of residential buildings (about 93%), corresponding to the Low class (Ordinary). A smaller share includes ecclesiastical buildings (4%) and, to a lesser extent, structures hosting collective functions, such as cultural associations, offices, and small-scale commercial activities, which are assigned a High (Relevant) exposure value (

Figure 9a).

For the economic value, the municipality is subdivided into six OMI zones (B1, B2, C1, C2, D1, and R1), with market values that vary by zone. Buildings located in CS1 and CS2 fall within zones B1, with market values between 630 and 760 €/m2, and B2, with values between 345 and 510 €/m2. For classification purposes, the market value ranges were normalized into four classes, based on the minimum and maximum values observed within the municipal territory. The analysis shows that the highest exposure values are concentrated in the area where OMI zone B1 intersects census section CS2.

Finally, four listed buildings identified in the Regional Landscape Plan [

62] (Palazzo Rondinelli, Palazzo Bonelli, Palazzo Federici–Cavaliere, and Palazzo De Ruggieri) were included, together with buildings retrieved from Vincoli in Rete, a cultural-heritage constraints dataset [

66], which includes the Chiesa Madre and other minor churches; these were assigned the highest exposure class, Very High. Given the historical and identity value of the historic center, in which most of the aggregates in the two sections are located, each building within this area was assigned a moderate exposure class (

Figure 9b). This choice reflects the fact that, even in the absence of high market values, the historic fabric possesses cultural and symbolic relevance that increases overall exposure, consistent with its identity role and the need for priority protection compared with the rest of the urban fabric [

37].

The overall exposure value (E) was computed through an automated pipeline developed ad hoc in QGIS and integrated into the Processing Toolbox by means of a dedicated Python script. The script systematically combines the three main exposure components (economic, strategic–functional, and cultural–heritage) and returns, for each building aggregate, a synthetic value and a qualitative exposure class. Consistent with a conservative worst-case approach, the code automatically selects the highest level among the three components to represent the most critical exposure condition, assigning an exposure class and code and thus providing an aggregate-scale exposure assessment (

Figure 10). The results indicate higher exposure for buildings with higher market values and for listed/protected buildings; overall, within the hotspot area (CS1–CS2,

N = 234), exposure is predominantly Moderate (157 BAs; 67.1%), followed by Very High (51 BAs; 21.8%), while Low (19 BAs; 8.1%) and High (7 BAs; 3.0%) classes are less represented, confirming that most residential buildings exhibit medium-to-low exposure levels.

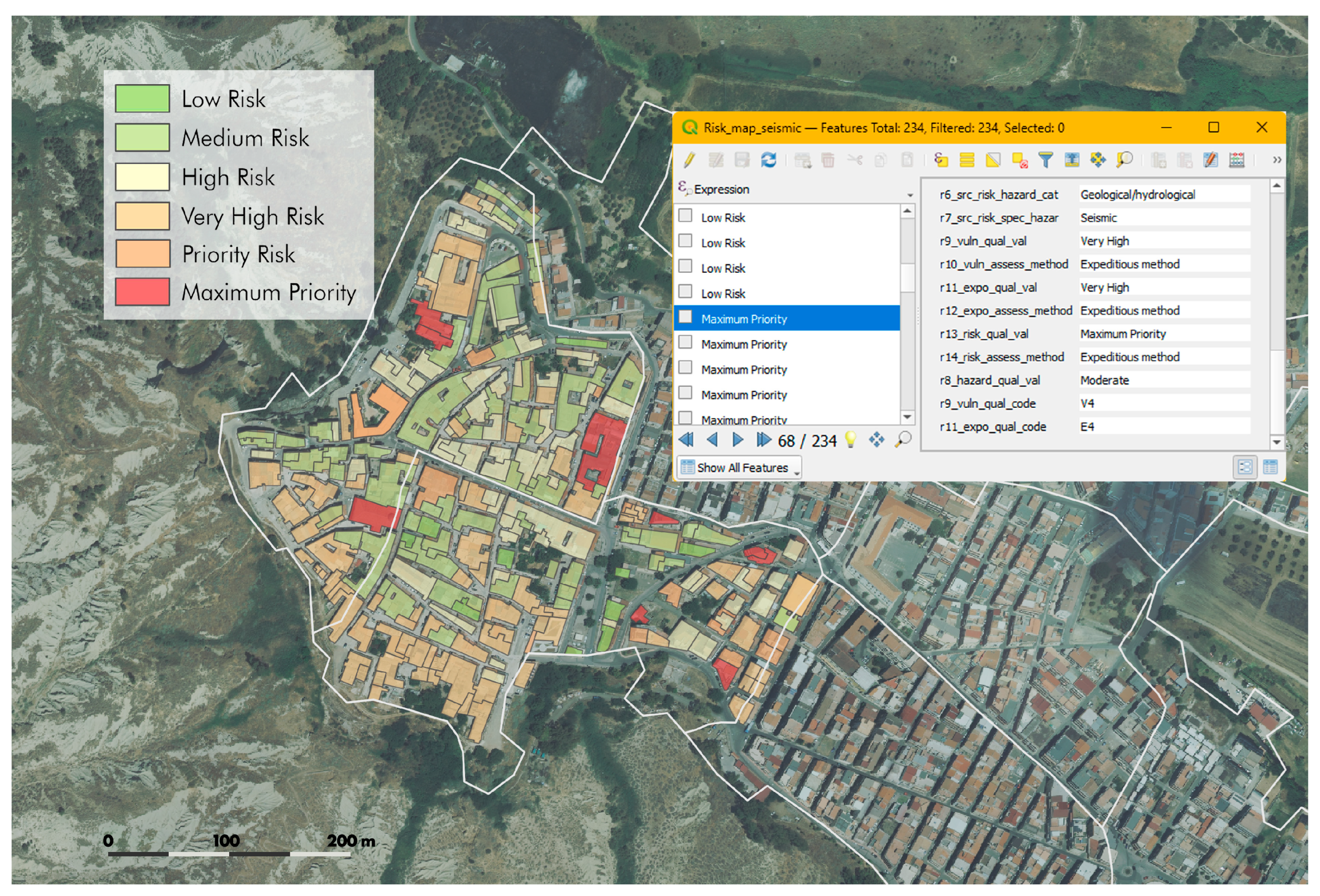

The subsequent risk assessment was carried out in parallel to the two hazard types. As in the previous phases, an ad hoc Python pipeline was developed and integrated into the QGIS Processing Toolbox; it reads hazard, vulnerability, and exposure values, consistent with the semantics defined for the risk layer and the geometry of the aggregates, and combines them through a 4 × 4 risk matrix in accordance with the relation R = H × V × E, producing six risk classes and the final thematic risk map (ph03B).

For the seismic component, risk was evaluated by combining vulnerability and exposure values at the building aggregate scale, assuming a spatially uniform hazard level. The analysis reveals a spatial distribution that is strongly controlled by typological–constructional features and by the conservation state of the building assets (

Figure 11). The highest risk classes (High and Very High) are concentrated where the building aggregates are older, composed of load-bearing masonry buildings with plan irregularities and nonuniform heights. In these areas, the combination of high structural vulnerability and high building density amplifies the potential severity of seismic effects. Overall, the seismic risk classification shows that 104/234 BAs (44.4%) fall in the Very High–Maximum Priority classes (

Table 3), with a higher concentration in CS2 than in CS1. Moderate risk classes are distributed along the central belt of the historic center, where urban morphology is more regular, and buildings exhibit better maintenance conditions. The lowest risk classes are found in sectors with more recent RC buildings and a more open urban layout.

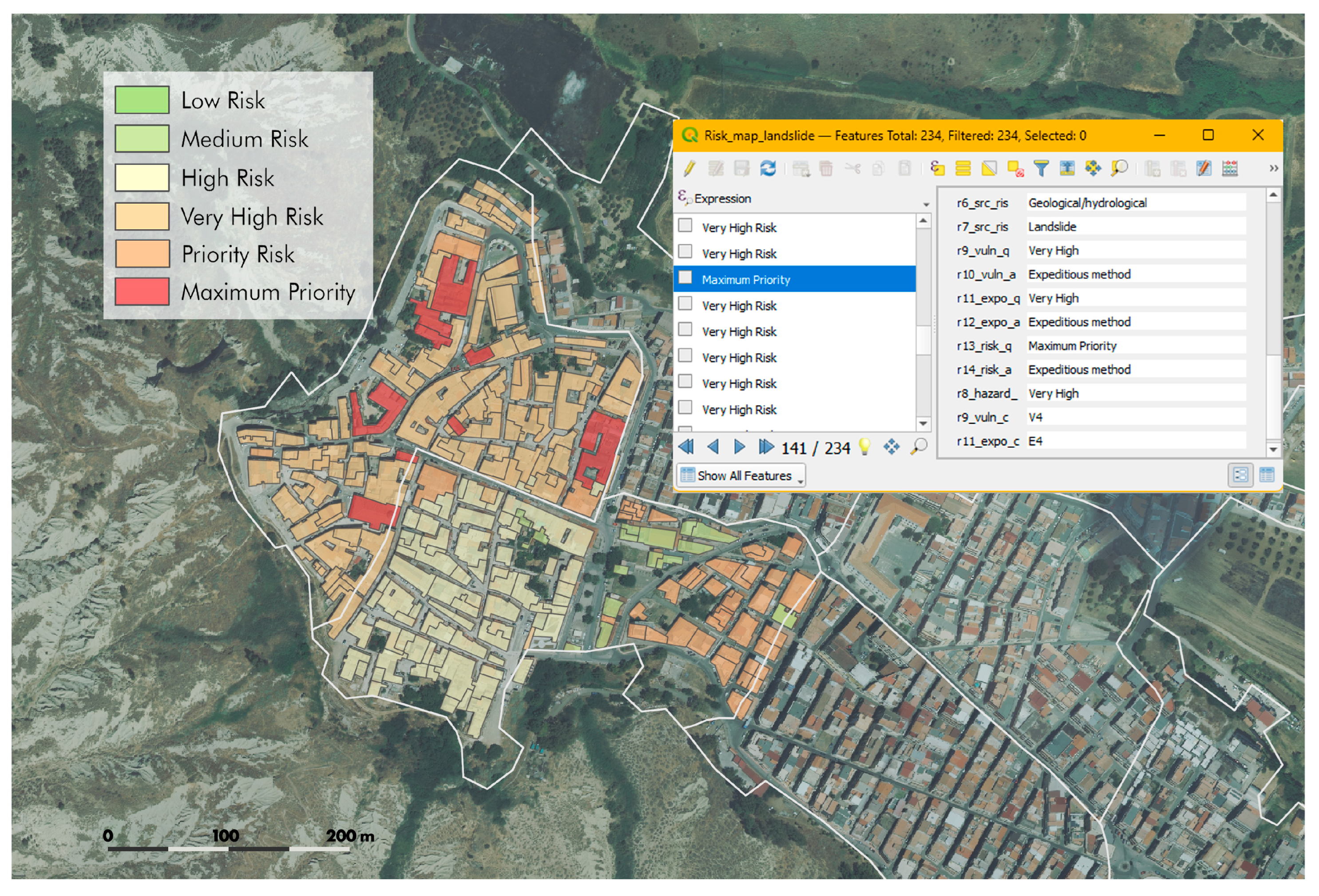

For landslide risk, the custom script produced a risk map showing a spatial distribution that is strongly correlated with the morphology of the historic center of Montalbano Jonico (

Figure 12). The highest risk classes (High and Very High) are concentrated along the western margin of the badlands, where the combination of high structural vulnerability of masonry buildings and high landslide hazard generates the most critical conditions. 148/234 building aggregates (63.2%) are classified as Very High/Maximum Priority (

Table 3), largely driven by the prevalence of the Very High class. Intermediate classes (Moderate) are in central and transitional areas, characterized by gentler slopes and buildings with generally better construction conditions. Finally, the lowest risk values are found in the more recent expansion zones, characterized by reinforced concrete buildings on stable terrain, where both hazard and vulnerability remain limited.

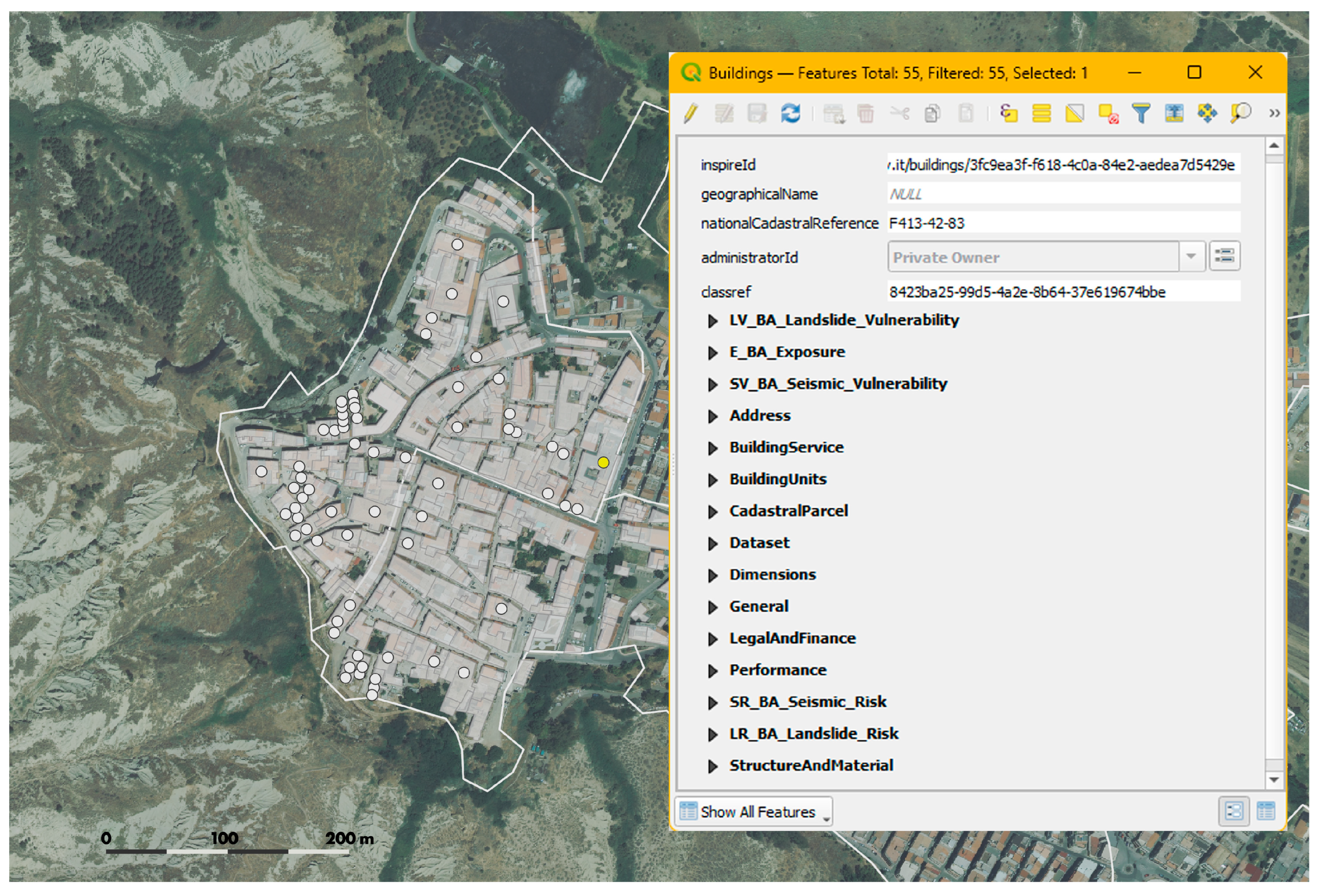

To complete the analysis, the risk maps were used to derive building-level prioritization. Digital Building Logbooks (DBLs) were then compiled for buildings classified as Priority or Maximum Priority in either the seismic or landslide risk maps, within the historic center area, using the cadastral footprint as the spatial reference for their localization (

Figure 13). Within this layer, data from the different levels of analysis (hazard, vulnerability, exposure, and risk) are integrated through direct spatial relationships based on the two unique keys used in the process (classRef for building aggregates and inspireId for buildings), together with the technical and informational metadata defined in the ontology. In this way, the DBL becomes an operational tool for the management and updating of the buildings, enabling all territorial and structural information derived from the multi-hazard model to be consistently transferred to the building scale (ph04A).

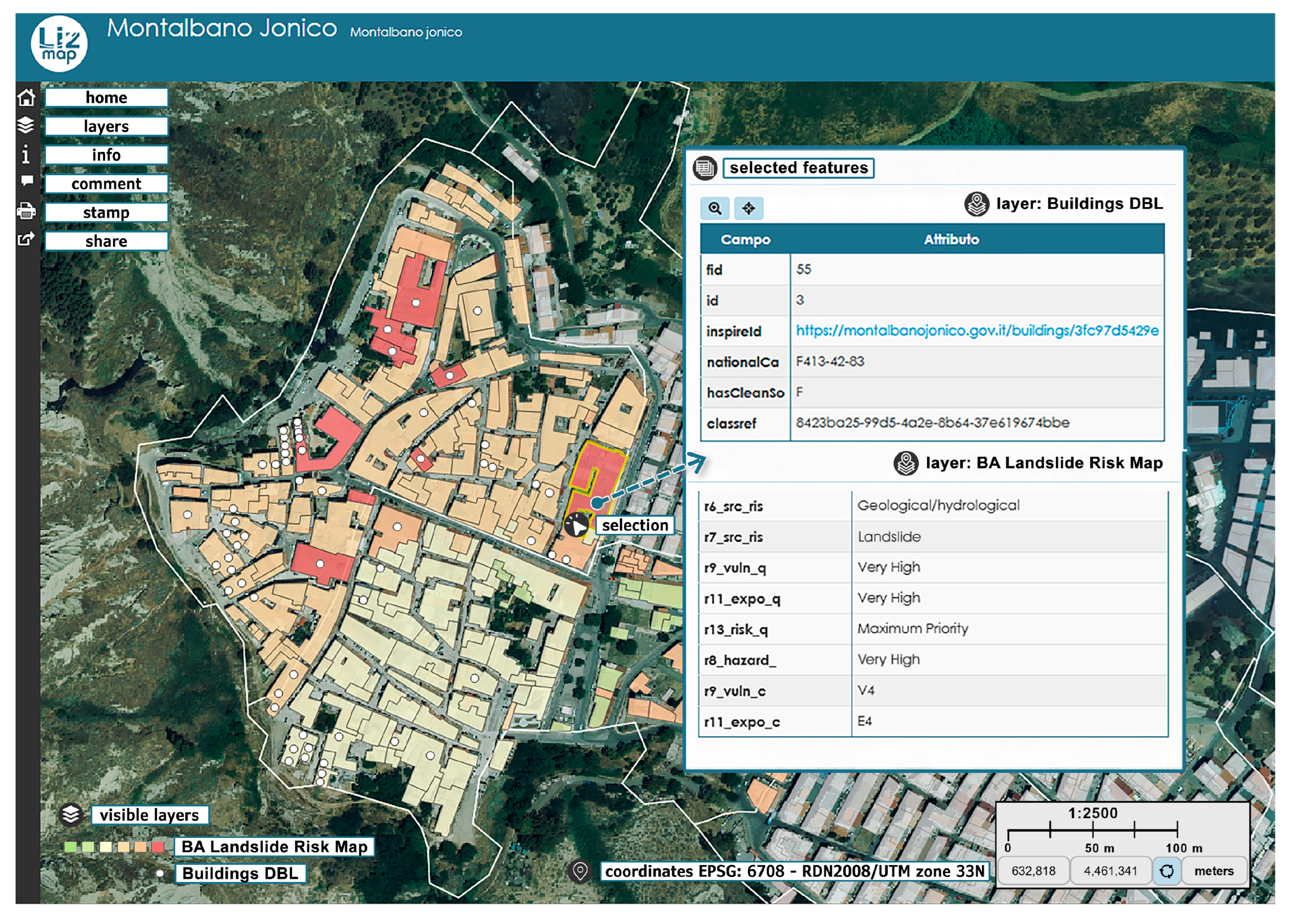

The subsequent phase (ph04B) involved publishing the results on a WebGIS platform built with Lizmap® Web Client 3.9.4, an open-source software that enables QGIS projects to be viewed and queried on the web. The configuration was carried out using the dedicated QGIS plugin, which was used to define the layer structure, the relationships between database entities, and the informational fields to be made available for consultation.

The WebGIS environment was set up as the access interface to the information system, preserving the hierarchy of analysis levels and the connections between buildings, aggregates, and census sections. The platform allows users to navigate across the different layers, query individual features, and visualize linked data, including the records compiled in DBL, using search and filtering functions that support the exploration of results. The WebGIS interface and the main thematic layers are shown in

Figure 14.

4. Discussion

The multi-hazard risk assessment workflow presented in this study provides a structured and reproducible approach that bridges territorial multi-hazard screening and decision-ready prioritization at the building and building aggregate scales in historic city centers, thereby addressing a key gap identified in the state of the art. It harmonizes heterogeneous spatial datasets within an INSPIRE-aligned relational architecture implemented in PostGIS, reducing informational fragmentation and producing semantically consistent outputs that are interoperability-ready and transferable toward GIS–BIM-oriented environments. The workflow was implemented in an open-source GIS environment and supported by automated Python scripts to standardize procedures and extend core system functionalities. Within this framework, physical and morpho-settlement vulnerability aggregate indices are integrated with socio-territorial components and heritage-related exposure dimensions while maintaining semantic consistency and explicit traceability of sources. This integration supports a decision-oriented interpretation of multi-domain risk drivers and clarifies how area-based patterns translate into localized priorities, which is a persistent challenge in preventive risk governance for complex historic assets. The following subsections synthesize the main key findings (

Section 4.1), discuss the implications for decision-makers (

Section 4.2), and finally, limitations and future developments (

Section 4.3).

4.1. Key Findings

From a methodological perspective, the use of a regular grid as a neutral analysis unit, combined with the normalization of the different hazard contributions to a common metric, allowed the representation of heterogeneous phenomena (seismic, flood, and landslide) in a homogeneous way and the clear identification of the most critical areas along the badlands edge of the historic center. Identifying the dominant hazard for each cell proved useful for downscaling and for guiding the selection of census sections and building aggregates on which to focus the subsequent vulnerability and exposure analyses.

Regarding data organization, the adoption of a spatially enabled relational database, structured according to INSPIRE themes and based on a system of primary and foreign keys, enabled the maintenance of semantic consistency between heterogeneous sources and the establishment of stable links between administrative units, census sections, aggregates, and individual buildings. In this way, the system simplifies the application of the workflow according to the level of detail of the available data and supports the reading of results at different scales, allowing a shift from an extensive view of the municipal territory to a selective focus on the most critical areas, without losing information at either higher or lower levels. The exposure component, articulated into strategic–functional, economic, and cultural contributions, also showed the ability to identify, at least as a first approximation, specific situations related to the variability in exposure of the same building that would otherwise remain unnoticed. In particular, the integration of sources such as OMI real estate values, landscape protection constraints, and land use data made it possible to combine indicators of different nature within a common framework.

Finally, the automation of procedures through Python scripts integrated into the QGIS toolbox enabled a more transparent and replicable workflow, reducing the risk of errors in repetitive operations (normalization, reclassification, index calculation, and population of risk fields), especially in scale-transition steps. Overall, the Montalbano Jonico case study shows that a multi-hazard and multi-scale workflow based on open data and open-source tools can be implemented even in small contexts with limited resources, providing a comparative framework that supports prevention and risk mitigation actions.

4.2. Implications for Decision-Makers