Bulkfill Resin Composite Polymerization Efficiency by Monowave vs. Polywave Light Curing Units: A Systematic Review of In Vitro Studies

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sources and Search Strategy

2.2. Selection, Inclusion, and Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Data Extraction

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessment

3. Results

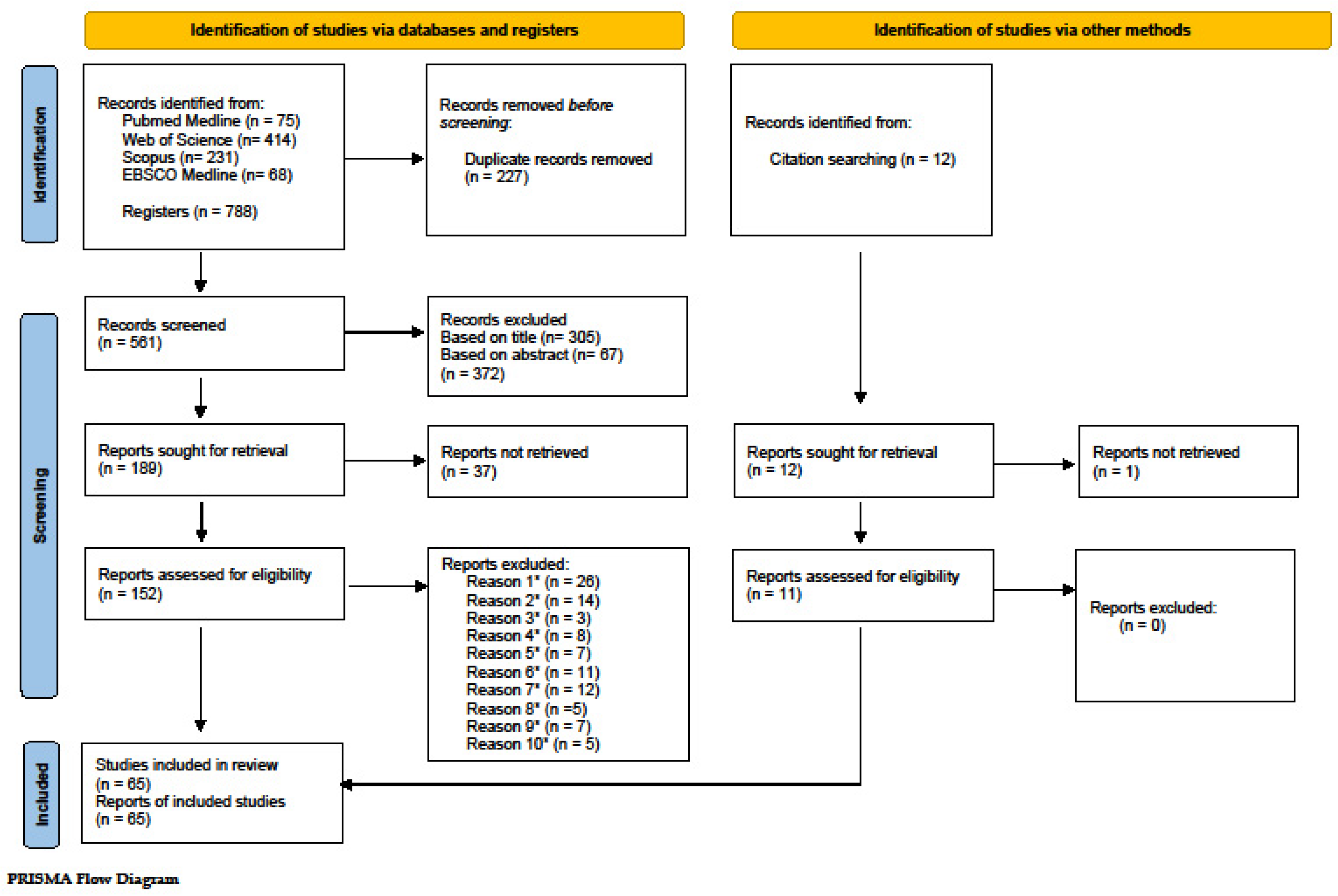

3.1. Search and Selection

3.2. Descriptive Analysis

| First Author Year of Publication | Bulk Fill Resin Composite | LCU Monowave Irradiance (mW/cm2) | Exposure Time (s) | LCU Polywave Irradiance (mW/cm2) | Exposure Time (s) | Methodology | Number of Specimens | Results | Polywave-Monowave Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelwahed 2022 [62] | PALFIQUE BULK FLOW X-tra fil (Voco) Filtek™ One Bulk Fill (3M/ESPE) | Dr’s light AT CL-AT24 1400 | 5 s | VHN | 10 | All materials >80% B/T VHN | _ | ||

| Aldhafyan 2025 [63] | STARK bulk fill Composite (President) Filtek One bulk fill restorative (3M/ESPE) SDR Plus bulkfill flowable (Dentsply) Tetric N-Cerambulk fill (Ivoclar) X-tra fil (Voco) BEAUTIFIL-Bulk Restorative (Shofu) | Elipar S10 (3M/ESPE) 1200 | 20 s | VHN Immediate/24 h | 5 | 58.31/61.97 32.08/48.51 18.75/29.28 38.19/46.94 64.03/72.06 45.09/49.50 | |||

| Algamaiah 2024 [19] | Filtek One Bulkfill (3M/ESPE) Tetric EvoCeram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) Tetric Power Fill (Ivoclar) Tetric EvoFlow Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) Tetric Power Flow (Ivoclar) Estelite bulkfill (Kuraray) | Elipar S (3M/ESPE) 1200 | 20 s | BluePhase Powercure (Ivoclar) 1200 | 10 s 3 s | DC (FTIR) | 5 | EliparS > Bluephase Power cure All material >50% except for Tetric PowerFlow and Filtek One Bulkfill | _ |

| Alrahlah 2014 [64] | Tetric Evo Ceram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) X-tra Base (Voco) Venus Bulk Fill (Heraeus) Filtek Bulk Fill (3M) Sonicfill (Kerr) | Elipar-S (3M/ESPE) 1200 | 20 s | VHN | 3 | All > 80% | _ | ||

| Alzahrani 2023 [65] | Bulk Fill One Bulk Fill (3M/ESPE) | Blue phase G2 1200 | 20 s 40 s | VHN | 20 | 4.1 mm (20 s) 5 mm (40 s) | _ | ||

| ALShaafi 2016 [78] | SDR (Dentsply) x-Trafil (Voco) Tetric Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) SonicFill (Kerr) | Bluephase 20i (Ivoclar) 1402 | 20 s | KHN | 5 | 80% 88% 70% 70% | _ | ||

| Altınok Uygun 2021 [36] | SonicFill (Kerr) Tetric EvoCeram Bul kFill (Ivoclar) X-trafil (Voco) | Valo (Ultradent) 1000 1400 3200 | 20 s 12 s 6 s | DC (FTIR) VHN | 10 | Peculiar method >80% Filtek76–79 | _ | ||

| Arafa 2025 [37] | Tetric Power Fill (Ivoclar) Tetric N-Ceram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) | Guilin (Woodpecker Medical Instrument) 900 | 20 s | DC (FTIR) | 5 | 55.3 (5.47) 61.6 (6.60) | |||

| Cardoso 2022 [20] | Filtek One Bulk Fill (3M/ESPE) Aura Bulk Fill (SDI) Tetric Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) | Radii Xpert (SDI) 1575 | 20 s | Valo (Ivoclar) 1103 | 20 s | DC (FTIR) | 10 | ~50% Significantly higher differrences Valo Tetric bulkfill | Material dependent Polywave |

| Conteras 2021 [21] | Tetric N-Ceram Bulkfill (Ivoclar) | 3M/ESPE 2nd generation LED 1181.2 | 20 s | BluePhase N 1145.3 | 20 s | DC (FTIR) | 5 | No significant difference | No significant defference |

| Czasch 2013 [38] | Surefil SDR Flow (Dentsply) Venus bulk fill (Heraeus Kulzer) | Elipar Freelight 2 (3 M ESPE) 1226 | 10 s 20 s 40 s | FTIR | 6 | 58.3 (1.7) 62.9 (2.3) 59.7 (1.7) 66.1 (2.8) 61.2(2.1) 67.92 (1.6) | |||

| Daugherty 2018 [39] | Beautifil-Bulk, (SHOFU) Filtek-Bulk-Fill, (3 M ESPE) Tetric-EvoCeram-Bulk-Fill (Ivoclar) Sonic-Fill-2(Kerr) Venus-Bulk-Fill (Kulzer) | FlashMax P3 (CMS Dental) 2378 Paradigm (3M ESPE 1226 SPEC 3 (Coltene) 1827 3001 | 3 s, 9 s 10 s, 20 s 5 s 20 s | DC (FTIR) | 1 | standard irradiance& exposure did significantly outperform the other two combinations Venus-Bulk-Fill best | _ | ||

| Derchi 2018 [22] | Filtek Bulk Fill (3M/ESPE) Surefil SDR (Dentsply) Tetric Evo Ceram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) | Bluephase style M8 800 | 20 s | Bluephase style 1200 Valo 1000 | 20 s 20 s | DC (FTIR) | 3 | >50% except Filtek Bulkfill with monowave, which was lower | Polywave |

| Elhejazi 2024 [66] | Any-Com™ Bulk (Mediclus) Opus Bulk Fill Flow APS (FGM) Filtek™ One Bulk Fill Restorative (3M/ESPE) Opus Bulk Fill APS (FGM) | BluePhase | manufacturer’s instructions | VHN KHN | 5 | >80% except Opus Bulk and Opus Flow | _ | ||

| Fronza 2017 [84] | Filtek Bulk Fill (3M ESPE) Tetric Evo Ceram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) | Valo (Ultradent) 995 | 20 s | DC Raman | 5 | 46.2 (1.0) 61.0 (1.5) | |||

| Gan 2018 [23] | Tetric N-Ceram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) SDR Posterior Bulk Fill Flowable Base (Dentsply) | Bluephase N monowave 800 QHL-5 550 | 15 s 21.8 s | Bluephase N polywave 1200 650 | 10 s 18.5 s | KHN | 6 | Monowave significantly higher Both < 80% | Monowave |

| Garcia 2014 [79] | SureFil SDR flow (Dentsply) Venus Bulk Fill (Kulzer) Sonic Fill (Kerr) | SmartLite iQ2 (Dentsply) 800 | 20 s | KHN | 10 | All materials < 70% B/T KHN at 4 mm | _ | ||

| Garoushi 2016 [40] | X-trafil (Voco) Venus bulk fill (Heraeus) TetricEvoCeram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) SDR (Dentsply) Filtek Bulk Fill (3M) SonicFill (Kerr) | Elipar Freelight 2 (3M) 1000 | 40 s | DC (FTIR) | 3 | All >55% except for Tetric Evo Ceram Bulk Fill | _ | ||

| Georgiev 2021 [67] | Filtek One Bulk Fill Restorative (3M/ESPE) | LED LCU Curing Pen (Eighteeth, China) 600 1000 1500 | 20 s 40 s 60 s | VHN | 3 | 600 × 20 > 78% >80% | _ | ||

| Gomes de Araújo-Neto 2021 [56] | Filtek Bulk Fill (3M/ESPE) Tetric N-Ceram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) | Valo 1680 | 10 s | DC (micro-Raman) | 10 | FB88% TC 83% | _ | ||

| Goncalves 2018 [41] | Filtek bulk fill (3M/ESPE) Filtek bulk fill flow (3M/ESPE) SonicFill (Kerr) Venus bulk fill flow (Kulzer) | Radii (SDI) 800 | 25 s | DC (FTIR) | 5 | All above 55%, except Filtek bulk fill flow | _ | ||

| Goracci 2014 [42] | SonicFill (Kerr) SDR (Dentsply) | Demi Led (Orange) 1100 | 20 s | DC (FTIR) | 5 | SonidFill > 55% SDR > 50% | _ | ||

| Gonzales Guarneri 2025 [42] | Tetric PowerFill (Ivoclar) Tetric PowerFlow (Ivoclar) Filtek One Bulk Fill Restorative (3M/ESPE) Filtek Bulk Fill Flowable (3M/ESPE) Tetric plus Fill (Ivoclar) Tetric plus Flow (Ivoclar) | Bluephase PowerCure (Ivoclar) 1226 | 10 s | DC (FTIR) | 3 | 42.8 56.1 45.6 45.4 45.8 52.9 | |||

| Jakupovic 2023 [68] | Tetric Power Fill (Ivoclar) Tetric Power Flow (Ivoclar) | Bluephase PowerCure (Ivoclar) 3440 1340 | 3 s 10 s | VHN | 8 | All bulkfil > 80% | _ | ||

| Jakupovic 2025 [83] | Tetric PlusFill (Ivoclar) Tetric PowerFill (Ivoclar) Tetric PlusFlow (Ivoclar) Tetric PowerFlow (Ivoclar) | Bluephase PowerCure (Ivoclar) 1200 | 10 s | VHN | 7 | 88 87 89 87 | |||

| Javed 2025 [44] | (SDR)-Universal shade (Dentsply Caulk) Beautifi Bulk Restorative universal shade (Shofu Inc) | Bluephase N (Ivoclar) 1120 | 20 s | DC (FTIR) VHN | 7 | 70.65 (1.37) 46.48 (1.07) 94% 86% VHN > 80% all | |||

| Ilie Stark 2014 [69] | High viscosity Tetric Evo Ceram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar0 X-tra Fil (Voco) SonicFill (Kerr) | Valo (Ultradent) 1272 | 20 s 40 s | VHN | 5 | 80% B/T VHN 6 mm 5.6 mm (20 s) 6 mm (40 s) 4.3 mm (20 s) 5.4 mm (40 s) | _ | ||

| Ilie Stark 2015 [70] | Low Viscosity Venus Bulk Fill (Kulzer) Surefil SDR (Dentsply) X-tra base (Voco) Filtek Bulk Fill (3M/ESPE) | Valo (Ultradent) 1272 | 20 s 40 s | VHN | 5 | 80% B/T VHN All > 6 mm | _ | ||

| Karacolak 2018 [71] | Aura (Kuraray) Filtek Bulk Fill Posterior (3M) SonicFill (Kerr) X-tra Fill (Voco) Tetric EvoCeram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar Filtek Bulk Fill Flowable (3M/ESPE) SDR (Dentsply) X-tra Base (Voco) Venus Bulk Fill | SmartLite Focus (Dentsply) | 20 s | VHN | 5 | >80% Except Sonicfill and Tetric EvoCeraqm Bulk Fill | _ | ||

| Kaya 2018 [24] | Beautifil Bulk Restorative (Shofu) | Optima 10 1100 Demi Ultra 1100–1330 | 20 s 10 s | Valo (Ultradent) 3200 | 3 s | DC (FTIR) | 5 | Demi Ultra> Optima> Valo | Monowave |

| Lempel 2023 [57] | Tetric PowerFill (Ivoclar) Filtek One Bulk Fill Restorative (3M/ESPE) | Bluephase PowerCure (Ivoclar) 3150 1180 1950 | 3 s 5 s 10 s, 20 s | DC (Micro-Raman spectroscopy) | 5 | 20 s Tetric 50.8 Filtek 48.9 | _ | ||

| Li 2015 [58] | Filtek Bulk Fill Flowable (3M/ESPE) Tetric EvoCeram Bulk Fil (Ivoclar) SDR (Dentsply) | Bluephase 20i (Ivoclar Vivadent) | 20 s | DC Micro-Raman mapping | 3 | Properly cured | _ | ||

| Maghaireh 2019 [25] | X-tra fill (Voco) Filtek-Bulk Fill flowable (3M/ESPE) Tetric Evo-Ceram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) SDR posterior Bulk Fill Flowable (Dentsply) Filtek Bulk Fill posterior (3M/ESPE) | Elipar S10 (3M) 1200 | 10 s | Bluephase Style (Ivoclar) 1000 | 10 s | VHN | 5 | 4 mm B/T VHN above 80% except Tetric EvoCeram Bulkfill and Filtek Bulk Fill Flowable X-tra fill polywave and Filtek Bulk Fill posterior Monowave | Material dependent |

| Makhdoom 2020 [26] | Tetric EvoCeram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) Filtek Bulk Fill (3M/ESPE) | Satelec | 10 s 20 s | BluePhase Style | 10 s 20 s | 4049 | 5 | No statistically significant differences Inadequate depth | No significant difference |

| Marovic 2025 [27] | Filtek One Bulk Fill (3M ESPE) Tetric PowerFill (Ivoclar) Tetric PowerFlow (Ivoclar) SDR flow(Dentsply Sirona) | Translux Wave (Kulzer) 1000 1000 | 10 s 20 s | VALO Cordless (Ultradent) 3000 1000 1000 Bluephase PowerCure (Ivoclar) 3000 1000 1000 | 3 s 10 s 20 s 3 s 10 s 20 s | DC (FTIR) | 5 | 20 s > higher conversion Power Flow and SDR > 50% Monowave Polywave no significant difference | No significant difference |

| Miletic 2017 [45] | Filtek Bulk Fill Flowable (3M/ESPE) SDR, Smart Dentin Replacement (Dentsply) SonicFill (Kerr) Xenius Base (Xenius) Tetric EvoCeram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) | Bluephase 20i (Ivoclar) | 10 s 20 s | DC (FTIR) VHN ISO 4049 [3] | 6 6 6 | DC SDR: >60% at 6 mm Filtek > 60% at 4 mm Rest < 50% B/T VHN At 10 s well above 80% SDR and Filtek Bulkill flowable At 20 s all Bulk Fills ISO > 4 mm except For SonicFill >5 mm: SDR, Filtek, Xenius | _ | ||

| Moharam 2017 [72] | X-tra Fill (Voco) Sonic Fill (Kerr) | Elipar S10, (3M ESPE) 1000 | 20 s | VHN | 10 | 97.6 (0.6) 90.4 (1.5) | |||

| Ozciftci 2025 [46] | PowerFill (Ivoclar) PowerFlow (Ivoclar) Omnichroma Flow Bulk (Tokuyama) | Bluephase PowerCure 1100 | 10 s/20 s | DC (FTIR) VHN | 61.71/57.38 77.9/66.49 47.34/51.78 80.31%(5)/81.05%(4) 80.96%/(4)/79.87%(3) 75.09%(5)/86.97%(5) | ||||

| Özdemir 2025 [73] | GrandioSO Heavy Flow (Voco) Filtek Bulk Fill (3M/ESPE) SonicFill 2 (Kerr) | Valo (Ultradent) 1000 | 20 s | VHN | 5 | 4.8–5.1 mm Depth of cure 80% | _ | ||

| Papadogiannis 2015 [47] | SDR (Dentsply) SonicFill (Kerr) Tetric Evo Ceram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) X-tra Base (Voco) X-tra Fill (Voco) | Bluphase G2 1200 | 30 s | DC (FTIR) | 5 | Venus, SDR > 55% Material dependent | _ | ||

| Par 2015 [59] | Tetric EvoCeram BulkFill (Ivocalr) Quixfil (Dell Denral) X-tra fil (Voco) Venus Bulk Fill (Kulzer) X-tra Base (Voco) SDR (Dentsply) Filtek Bulk Fill (3M/ESPE) | Bluephase G2 (Ivoclar) 1090 | 20 s | DC (Raman Spectroscopy) | 5 | Adequate polymerizarion 59.1–71.8% | _ | ||

| Par 2019 [28] | TetricEvoCeramBulkFill (Ivoclar) FiltekBulkFill (3M/ESPE) X-trafil (Voco) | BluePhasreStyle M8 (Ivoclar)648 | 30 s | BluePhase Style (Ivoclar) 924 | 30 s | VHN | 5 | No benefit for Bf containing alternative Photonitiators All BF > 80% | No significant difference |

| Parasher 2020 [74] | X-tra fil Tetric EvoCeram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) Beautiful Bulk restorative (Shofu) | Bluephase G2 | manufacturer’s recommenda tions | VHN | 19 | X-tra Fil > 80% | _ | ||

| Renzai 2019 [48] | Filtek Bulk Fill Posterior (3M/ESPE) Sonic Fill 2(Kerr) Tetric N-Ceram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) X-tra fil (Voco) | Bluepase N 1200 | 30 s | VHN DC (FTIR) | 6 3 | B/T VHN > 85% DC > 60% | _ | ||

| Rizzante 2019 [80] | Admira Xtra Fusion (Voco) Filtek Bulk Fill Posterior (3M/ESPE) Tetric Evo Ceram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) X-tra Fil (Voco) Filtek Bulk Fill Flowable (3M/ESPE) Surefil SDR flow (Dentsply) X-tra Base | LED Blue Star 3 (Microdont) 1550 | 20 s | KHN | 8 | All Bulkfill CR Adequate 80% DoC up to 4.5 mm | _ | ||

| Rocha 2017 [29] | Sonic Fill 2(Kerr) Tetric EvoCeram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) | Smartllite Focus (Dentsply) 1000 | 20 s | Valo (Ultradent) 954 | 21 s | DC (FT-NIR) | 3 | Inhomegeinity Polywave more effective in the superficial 2 mm of the material containing alternative photoinitiators 4 mm: no significant difference | No significant difference |

| Rocha 2022 [30] | Surefil SDR (Dentsply) Tetric Power Flow (Ivoclar) X-tra-Fil (Voco) | SmartLite Pro (Dentsply/Sirona) 1200 Monet (AMD Lasers) 2000–2400 | 10 s 20 s 1 s, 3 s | Valo Grand (Ultradent) 900 | 10 s 20 s | ISO 4049 [3] | 10 | DOC > 4 mm Monowave no significant differences, SDR monowave higher Monowave 10 s higher | No significant difference |

| Sampaio 2024 [49] | Tetric EvoCeram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) Tetric EvoFlow Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) Tetric PowerFill (Ivoclar) Tetric PowerFlow (Ivoclar) | Bluephase Style 20i 1200 Bluephase Powercure 3050 | 20 s 3 s | DC (FTIR) VHN | 5 | Bottom DC Only Tetric Evo Ceram Bulk Fill 53.3% TetricPower Flow 61.2% B/T VHN all > 80% | _ | ||

| Shimokawa 2018 [31] | Filtek Bulk Fill posterior Restorative (3M/ESPE) Tetric EvoCeram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) | Elipar DeepCure-S (3M) 1470 Celalux 3 (Voco) 1300 | Bluephase 20i (Ivoclar) 1200 Valo Grand (Ultradent) 1000 | KHN | 5 | All ~70% Polywave Wide light tip> homogeneous distribution of irradiance and wave lengths | Monowave | ||

| Siagian 2020 [32] | Filtek Bulk-Fill (3M/ESPE) Tetric N-Ceram Bulk-Fill (Ivoclar) SDR flow (Dentsply) | SmartLite Focus (Dentsply Sirona) | 20 s | Bluephase style (Ivoclar) | 40 s | DC (FTIR) Pulverized samples | 5 | DC > 50% Filtek and Tetric with both LCUs SDR < 50% No significant differences | No significant difference |

| Skrinjaric 2025 [75] | Tetric EvoCeram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) Filtek Bulk Fill Posterior (3M/ESPE) Filtek One Bulk Fill(3M/ESPE) SonicFill 2 (Kerr) Admira Fusion X-tra (Voco) Admira Fusion X-tra (Voco) | D-Light Duo (RF-Pharmaceuticals Sarl) 1200–1300 | 20 s | VHN 4 mm/ 6 mm | 3 | 91/87 90/90 96/90 95/94 98/96 98/97 | |||

| Son 2017 [76] | Filtek Bulk Fill (3M), SureFil SDR (Dentsply) Venus Bulk Fill (Heraeus) SonicFill (Kerr) Tetric N-Ceram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) | LE Demetron (Kerr) 900 | 40 s | VHN | 12 | SDR, Venus > 80% | _ | ||

| Soto-Montero 2020 [81] | Sonic Fill (Kerr) Tetric EvoCeram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) | Bluephase Style, Ivoclar Regular tip 935 homogenizer tip 850 | SF 20 s TECBF 10 s | KHN | 10 | Below 80% 78% with HT and 70% with RT | _ | ||

| Strini 2022 [50] | Filtek One Bulk Fill (3M/ESPE) Tetric N-Ceram Bulk-Fill (Ivoclar) SonicFill 2 (Kerr) | Valo (Ultradent) 1000 | 20 s | DC (FTIR) KHN | 15 | DC SonicFill2: 63.67% Rest below 50% B/T KHN all below 80% | _ | ||

| Terada 2024 [60] | Filtek Bulk-Fill Flowable (3M/ESPE) Beautifil Bulk Flowable (Shofu) Surefill SDR Flow (Dentsply) Filtek Bulk-Fill Restorative (3M/ESPE) Beautifil-Bulk Restorative (Shofu) Tetric EvoCeram Bulk Fill | Valo (Ultradent) 1001 | 20 s | DC (Raman spectroscopy) 3–4 mm depth | 5 | Between 82.2% and 90.9% | _ | ||

| Thomaidis 2024 [33] | VenusBulkFill (Kulzer) X-traBase (Voco) SDR (Dentsply) Tetric EvoCeram BulkFill (IvocalR0 SonicFill (Kerr) FiltekBulkFill flowable restorative (3M/ESPE) | Demi Ultra 1100 | 20 s | Bluephase Style 1100 Valo 1000 | 20 s 20 s | VHN | 10 | Material dependent | Material dependent |

| Torres 2024 [51] | Filtek One bulk fill restorative (3M/ESPE) Tetric N Ceram bulk fill (Ivoclar) SonicFill (Kerr) VisCalor (Kuraray) | Demi (Kerr) 1000 | 10 s 20 s 40 s | KHN DC (FTIR) | 5 5 | B/T KH > 80% only 40 s | _ | ||

| Tsuzuki 2020 [34] | SDR (Dentsply) | Raddi Plus (SDI) 1300 Emitter.D (Schuster) 1250 Biolux Plus (Bioart) 880 Woodpecker (Guilin Woodpecker) 520 | 20 s 40 s | Valo Cordless (Ultradent) 1010 | 20 s 40 s | DC (confocal Raman spectroscopy) | 10 | All LCUs above 50% at 20 s and 40 s Valo significantly higher than Radii plus and Biolux at 20 s | Polywave |

| Varshney 2022 [35] | Wonder Bulk Fill (Wizden) (CQ) Tetric N-Ceram (Ivoclar) (CQ + TPO + Ivocerin) | Waldent ECO Plus (Waldent) | 10 s | Bluephase N LED (Ivoclar) | 10 s | DC (FTIR) Of pulverized samples | 20 | BluePhase Tetric DC 59% Wonder < 50% Waldent(CQ) no significantly higher DC in Tetric(ivocerin) | Polywave |

| Wang 2021 [61] | Filtek Bul Fill Flowable (3M/ESPE) Filtek One Bulk Fill (3M/ESPE) | Elipar S10 (3M ESPE) 1200 | 20 s 40 s | DC (Micro-Raman spectroscopy) at 5 mm depth | 25 | Filtek Bulkfill Flowable >55% at 20 s and 40 s | _ | ||

| Yap 2016 [82] | Beautifil Bulk Restorative (Shofu) Beautifil Bulk Flowable (Shofu) SDR Posterior Bulk-Fill Flowable Base (Dentsply) EverX Posterior (GC) Tetric N-Ceram Bulk-Fill (Ivoclar) | Blue Shor LED (Shofu) 700 | 20 s | KHN ISO4049 | 5 | 80% B/T KHN 3 mm, except for EverX Posterior Tetric N-Ceram Bulk-Fil at 2.5 mm ISO 4049 [3] overestimated | _ | ||

| Yeo 2021 [77] | Filtek One Bulk Fill Restorative (3M/ESPE) | Elipar LED light cure 1200 | 20 s 40 s | VHN | 1 | B/T VHN 40 s > 96.8% 20 s > 85% | _ | ||

| Yıldırım 2023 [52] | SDR Plus (Dentsply) SonicFill 2 (Kerr) ACTIVA BioActive Restorative (Pulpdent) | Elipar FreeLight 2 (3M/ESPE) 1000 | Manufacturer’s instructions 20 s SDR 40 s | DC (FTIR) VHN | 6 10 | Inadequate polymerization In all materials | _ | ||

| Yokesh 2017 [53] | Surefil SDR bulk fill f lowable composite (Kerr) Filtek bulk fill flowable composite (3M/ESPE) | LEDition (Ivoclar) 600 | 20 s | DC(FTIR) Of pulverized coronal and pulpal half ISO 4049 [3] | 10 | DC < 50% ISO 4049 [3] Surefil: 3.89 Filtek: 3.54 | _ | ||

| Zorzin 2015 [54] | Filtek Bulk Fill Flowable (3M/ESPE) SDR Surefil (Dentsply) Tetric Evo Ceram Bulk Fill (Ivoclar) Venus Bulk Fill (Heraeus) X-tra Base (Voco) | Bluephase 20i (Ivoclar) 1200 | Manufacturer’s instructions 30 s | DC (FTIR) VHN | 5 | 30 s all Manufacturer’s instructions all except SDR and X-tra Base | _ |

3.3. Risk of Bias (Quality Assessment)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Bis-GMA | Bisphenol A-glycidyl methacrylate |

| Bis-EMA | Ethoxylated bisphenol A dimethacrylate |

| UDMA | Urethane dimethacrylate |

| AUDMA | Aromatic urethane dimethacrylate |

| TEGDMA | Triethylene glycol dimethacrylate |

| AFCT | Addition–fragmentation chain transfer |

| AFM | Addition–fragmentation chain transfer |

| RAFT | Reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer |

| VHN | Bottom to Top Vickers Hardness Ratio |

| KHN | Bottom to Top Knoop Hardness Ratio |

| DC | Degree of Conversion |

| DOC | Depth of cure |

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy |

| LCU | Light curing unit |

| QTH | Quartz-tungsten-halogen lights |

| LED | Light emission diode |

| CQ | Camphoroquinone |

| TPO | diphenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)-phosphine or Lucirin-TPO |

References

- Cadenaro, M.; Maravic, T.; Comba, A.; Mazzoni, A.; Fanfoni, L.; Hilton, T.; Ferracane, J.; Breschi, L. The role of polymerization in adhesive dentistry. Dent. Mater. 2019, 35, e1–e22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferracane, J.L.; Hilton, T.J.; Stansbury, J.W.; Watts, D.C.; Silikas, N.; Ilie, N.; Heintze, S.; Cadenaro, M.; Hickel, R. Academy of Dental Materials guidance-Resin composites: Part II-Technique sensitivity (handling, polymerization, dimensional changes). Dent. Mater. 2017, 33, 1171–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 4049; Dentistry—Polymer-Based Restorative Materials. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Francis, N.; Rajan, R.R.; Kumar, V.; Varughese, A.; Karuveetil, V.; Sapna, C.M. Effect of irradiance from curing units on the microhardness of composite—A systematic review. Evid.-Based Dent. 2022, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corrêa, A.; Moro, G.; Cechin, L.; Gonçalves, L.; Rocha, R.O.; Soares, F.Z.M. Polywave LEDs increase the degree of conversion of composite resins, but not adhesive systems: A systematic review and meta-analysis of in vitro studies. Lasers Med. Sci. 2025, 40, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, R.B.W.; Melo, A.M.D.S.; Dias, J.D.N.; Barbosa, L.M.M.; Santos, J.V.D.N.; Souza, G.M.; Andrade, A.K.M.; Assunção, I.V.; Borges, B.C.D. Are polywave light-emitting diodes more effective than monowave ones in the photoactivation of resin-based materials containing alternative photoinitiators? A systematic review. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2023, 143, 105905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucuta, S.; Ilie, N. Light transmittance and micro-mechanical properties of bulk fill vs. conventional resin based composites. Clin. Oral Investig. 2014, 18, 1991–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, N.; Bucuta, S.; Draenert, M. Bulk-fill resin-based composites: An in vitro assessment of their mechanical performance. Oper. Dent. 2013, 38, 618–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moszner, N.; Fischer, U.K.; Ganster, B.; Liska, R.; Rheinberger, V. Benzoyl germanium derivatives as novel visible light photoinitiators for dental materials. Dent. Mater. 2008, 24, 901–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, N. Sufficiency of curing in high-viscosity bulk-fill resin composites with enhanced opacity. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veloso, S.R.M.; Lemos, C.A.A.; de Moraes, S.L.D.; do Egito Vasconcelos, B.C.; Pellizzer, E.P.; de Melo Monteiro, G.Q. Clinical performance of bulk-fill and conventional resin composite restorations in posterior teeth: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loguercio, A.D.; Ñaupari-Villasante, R.; Gutierrez, M.F.; Gonzalez, M.I.; Reis, A.; Heintze, S.D. 5-year clinical performance of posterior bulk-filled resin composite restorations: A double-blind randomized controlled trial. Dent. Mater. 2023, 39, 1159–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lima, R.B.W.; Troconis, C.C.M.; Moreno, M.B.P.; Murillo-Gómez, F.; De Goes, M.F. Depth of cure of bulk fill resin composites: A systematic review. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2018, 30, 492–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, A.F.; Vestphal, M.; Amaral, R.C.D.; Rodrigues, J.A.; Roulet, J.F.; Roscoe, M.G. Efficiency of polymerization of bulk-fill composite resins: A systematic review. Braz. Oral Res. 2017, 31, e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.5 (Updated August 2024); Wiley-Blackwell: Cochrane, AB, Canada, 2024; Available online: www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Sheth, V.H.; Shah, N.P.; Jain, R.; Bhanushali, N.; Bhatnagar, V. Development and validation of a risk-of-bias tool for assessing in vitro studies conducted in dentistry: The QUIN. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2024, 131, 1038–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algamaiah, H.; Alshabib, A.; Algomaiah, M.; Yang, J.; Watts, D.C. Diversity of short-term DC outcomes in bulk-fill RBCs subjected to a 3 s high-irradiance protocol. Dent. Mater. 2024, 40, 1872–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, I.O.; Machado, A.C.; Fernandes, L.O.; Soares, P.V.; Raposo, L.H.A. Influence of tip diameter and light spectrum of curing units on the properties of bulk-fill resin composites. Eur. J. Dent. 2022, 16, 360–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, S.C.M.; Barbosa Jurema, A.L.; Claudino, E.S.; Bresciani, E.; Ferraz Caneppele, T.M. Monowave and polywave light-curing of Bulk-Fill resin composites: Degree of conversion and marginal adaptation following thermomechanical aging. Biomater. Investig. Dent. 2021, 8, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derchi, G.; Vano, M.; Ceseracciu, L.; Diaspro, A.; Salerno, M. Stiffness effect of using polywave or monowave LED units for photo-curing different bulk fill composites. Dent. Mater. J. 2018, 37, 709–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, J.K.; Yap, A.U.; Cheong, J.W.; Arista, N.; Tan, C.B.K. Bulk-fill composites: Effectiveness of cure with poly- and monowave curing lights and modes. Oper. Dent. 2018, 43, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaya, M.S.; Bakkal, M.; Durmus, A.; Durmus, Z. Structural and mechanical properties of a giomer-based bulk fill restorative in different curing conditions. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2018, 26, e20160662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maghaireh, G.A.; Price, R.B.; Abdo, N.; Taha, N.A.; Alzraikat, H. Effect of thickness on light transmission and Vickers hardness of five bulk-fill resin-based composites using polywave and single-peak light-emitting diode curing lights. Oper. Dent. 2019, 44, 96–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makhdoom, S.N.; Campbell, K.M.; Carvalho, R.M.; Manso, A.P. Effects of curing modes on depth of cure and microtensile bond strength of bulk fill composites to dentin. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2020, 28, e20190753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marovic, D.; Par, M.; Daničić, P.; Marošević, A.; Bojo, G.; Alerić, M.; Antić, S.; Puljić, K.; Badovinac, A.; Shortall, A.C.; et al. The role of rapid curing on the interrelationship between temperature rise, light transmission, and polymerisation kinetics of bulk-fill composites. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Par, M.; Repusic, I.; Skenderovic, H.; Milat, O.; Spajic, J.; Tarle, Z. The effects of extended curing time and radiant energy on microhardness and temperature rise of conventional and bulk-fill resin composites. Clin. Oral Investig. 2019, 23, 3777–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, M.G.; de Oliveira, D.; Correa, I.C.; Correr-Sobrinho, L.; Sinhoreti, M.; Ferracane, J.L.; Correr, A.B. Light-emitting diode beam profile and spectral output influence on the degree of conversion of bulk fill composites. Oper. Dent. 2017, 42, 418–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, M.G.; Maucoski, C.; Roulet, J.F.; Price, R.B. Depth of cure of 10 resin-based composites light-activated using a laser diode, multi-peak, and single-peak light-emitting diode curing lights. J. Dent. 2022, 122, 104141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimokawa, C.A.K.; Turbino, M.L.; Giannini, M.; Braga, R.R.; Price, R.B. Effect of light curing units on the polymerization of bulk fill resin-based composites. Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 1211–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siagian, J.S.; Dennis, D.; Ikhsan, T.; Abidin, T. Effect of different LED light-curing units on degree of conversion and microhardness of bulk-fill composite resin. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2020, 21, 615–620. [Google Scholar]

- Thomaidis, S.; Kampouropoulos, D.; Antoniadou, M.; Kakaboura, A. Evaluation of the depth of cure by microhardness of bulk-fill composites with monowave and polywave LED light-curing units. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 11532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuzuki, F.M.; de Castro-Hoshino, L.V.; Lopes, L.C.; Sato, F.; Baesso, M.L.; Terada, R.S. Evaluation of the influence of light-curing units on the degree of conversion in depth of a bulk-fill resin. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2020, 12, e1117–e1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varshney, I.; Jha, P.; Nikhil, V. Effect of monowave and polywave light curing on the degree of conversion and microhardness of composites with different photoinitiators: An in vitro study. J. Conserv. Dent. 2022, 25, 661–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altınok Uygun, L.; Akgül, N. Evaluation of the polymerization properties of bulk-fill composite resins. J. Dent. Mater. Tech. 2021, 10, 164–172. [Google Scholar]

- Arafa, N.; Sherief, D.I.; Elmalawanya, L.M.; Nassif, M.S. Performance of RAFT-based and conventional bulk-fill composites cured with conventional and high irradiance photocuring: A comparative study. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 714. [Google Scholar]

- Czasch, P.; Ilie, N. In vitro comparison of mechanical properties and degree of cure of bulk fill composites. Clin. Oral Investig. 2013, 17, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugherty, M.M.; Lien, W.; Mansell, M.R.; Risk, D.L.; Savett, D.A.; Vandewalle, K.S. Effect of high-intensity curing lights on the polymerization of bulk-fill composites. Dent. Mater. 2018, 34, 1531–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garoushi, S.; Vallittu, P.; Shinya, A.; Lassila, L. Influence of increment thickness on light transmission, degree of conversion and micro hardness of bulk fill composites. Odontology 2016, 104, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, F.; Campos, L.M.P.; Rodrigues-Júnior, E.C.; Costa, F.V.; Marques, P.A.; Francci, C.E.; Braga, R.R.; Boaro, L.C.C. A comparative study of bulk-fill composites: Degree of conversion, post-gel shrinkage and cytotoxicity. Braz. Oral Res. 2018, 32, e17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales Guarneri, J.A.; Gareau, A.; MacNeil, B.; Maucoski, C.; Campos, L.A.; Price, R.B.; Arrais, C.A.G. Impact of high irradiance and short exposure times on the polymerization kinetics of sculptable and flowable bulk-fill composites. J. Dent. 2025, 162, 105990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goracci, C.; Cadenaro, M.; Fontanive, L.; Giangrosso, G.; Juloski, J.; Vichi, A.; Ferrari, M. Polymerization efficiency and flexural strength of low-stress restorative composites. Dent. Mater. 2014, 30, 688–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, F.; Tewari, R.K.; Alam, S.; Husain, S.; Hasan, F. Effect of different light-curing modes and curing times on degree of conversion and microhardness of three different bulk-fill composites: An in vitro study. Clin. Oral Investig. 2025, 29, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miletic, V.; Pongprueksa, P.; De Munck, J.; Brooks, N.R.; Van Meerbeek, B. Curing characteristics of flowable and sculptable bulk-fill composites. Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 1201–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozciftci, G.; Boyacioglu, H.; Turkun, L.S. Degree of conversion and microhardness of different composite resins polymerized with an advanced LED-curing unit. BMC Oral Health 2025, 25, 1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papadogiannis, D.; Tolidis, K.; Gerasimou, P.; Lakes, R.; Papadogiannis, Y. Viscoelastic properties, creep behavior and degree of conversion of bulk fill composite resins. Dent. Mater. 2015, 31, 1533–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezaei, S.; Abbasi, M.; Sadeghi Mahounak, F.; Moradi, Z. Curing depth and degree of conversion of five bulk-fill composite resins compared to a conventional composite. Open Dent. J. 2019, 13, 422–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sampaio, C.S.; Abreu, J.L.B.; Kornfeld, B.; Silva, E.M.D.; Giannini, M.; Hirata, R. Short curing time bulk fill composite systems: Volumetric shrinkage, degree of conversion and Vickers hardness. Braz. Oral Res. 2024, 38, e030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strini, B.S.; Marques, J.F.L.; Pereira, R.; Sobral-Souza, D.F.; Pecorari, V.G.A.; Liporoni, P.C.S.; Aguiar, F.H.B. Comparative evaluation of bulk-fill composite resins: Knoop microhardness, diametral tensile strength and degree of conversion. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dent. 2022, 14, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, C.R.G.; Prado, T.P.; Ávila, D.M.D.S.; Pucci, C.R.; Borges, A.B. Influence of light-curing time and increment thickness on the properties of bulk fill composite resins with distinct application systems. Int. J. Dent. 2024, 1, 2123406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, S.Z.; Eyiler, E.; Bek Kürklü, Z.G. Effect of thickness on the degree of conversion, monomer elution, depth of cure and cytotoxicity of bulk-fill composites. J. Oral Sci. 2023, 65, 121–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yokesh, C.A.; Hemalatha, P.; Muthalagu, M.; Justin, M.R. Comparative evaluation of the depth of cure and degree of conversion of two bulk fill flowable composites. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2017, 11, ZC86–ZC89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zorzin, J.; Maier, E.; Harre, S.; Fey, T.; Belli, R.; Lohbauer, U.; Petschelt, A.; Taschner, M. Bulk-fill resin composites: Polymerization properties and extended light curing. Dent. Mater. 2015, 31, 293–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fronza, B.M.; Rueggeberg, F.A.; Braga, R.R.; Mogilevych, B.; Soares, L.E.; Martin, A.A.; Ambrosano, G.; Giannini, M. Monomer conversion, microhardness, internal marginal adaptation, and shrinkage stress of bulk-fill resin composites. Dent. Mater. 2015, 31, 1542–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomes de Araújo-Neto, V.; Sebold, M.; Fernandes de Castro, E.; Feitosa, V.P.; Giannini, M. Evaluation of physico-mechanical properties and filler particles characterization of conventional, bulk-fill, and bioactive resin-based composites. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2021, 115, 104288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lempel, E.; Szebeni, D.; Őri, Z.; Kiss, T.; Szalma, J.; Lovász, B.V.; Kunsági-Máté, S.; Böddi, K. The effect of high-irradiance rapid polymerization on degree of conversion, monomer elution, polymerization shrinkage and porosity of bulk-fill resin composites. Dent. Mater. 2023, 39, 442–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Pongprueksa, P.; Van Meerbeek, B.; De Munck, J. Curing profile of bulk-fill resin-based composites. J. Dent. 2015, 43, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Par, M.; Gamulin, O.; Marovic, D.; Klaric, E.; Tarle, Z. Raman spectroscopic assessment of degree of conversion of bulk-fill resin composites--changes at 24 h post cure. Oper. Dent. 2015, 40, E92–E101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terada, R.S.S.; Fronza, B.M.; Faraoni, J.J.; Hoshino, L.V.C.; Sato, F.; Palma-Dibb, R.G.; Scheffel, D.L.S.; Giannini, M. Roughness profile and surface roughness after toothbrushing and degree of conversion of bulk-fill resins. Braz. Oral Res. 2024, 38, e128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Wang, Y. Depth-dependence of degree of conversion and microhardness for dual-cure and light-cure composites. Oper. Dent. 2020, 45, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwahed, A.G.; Essam, S.; Abdelaziz, M.M. Marginal adaptation and depth of cure of flowable versus packable Bulk-Fill restorative materials: An In Vitro Study. Open Access Maced. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 10, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldhafyan, M.; Al-Odayni, A.B.; Saeed, W.S.; Khan, R.; Alrahlah, A. Network integrity of bulk-fill composites: Thermal stability, post-curing hardness development and acidic softening. Dent. Mater. J. 2025, 44, 201–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alrahlah, A.; Silikas, N.; Watts, D.C. Post-cure depth of cure of bulk fill dental resin-composites. Dent. Mater. 2014, 30, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzahrani, B.; Alshabib, A.; Awliya, W. The depth of cure, sorption and solubility of dual-cured bulk-fill restorative materials. Materials 2023, 16, 6673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elhejazi, A.A.; Alosimi, A.; Alarifi, F.; Almuqayrin, A. The effect of depth of cure on microhardness between bulk-fill and hybrid composite resin material. Saudi Dent. J. 2024, 36, 381–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiev, G.; Dikova, T. Hardness investigation of conventional, bulk fill and flowable dental composites. J. Achiev. Mater. Manuf. Eng. 2021, 109, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakupović, S.; Pervan, N.; Mešić, E.; Gavranović-Glamoč, A.; Bajsman, A.; Muratović, E.; Kazazić, L.; Kantardžić-Kovačević, A. Assessment of microhardness of conventional and bulk-fill resin composites using different light-curing intensity. Polymers 2023, 15, 2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, N.; Stark, K. Curing behaviour of high-viscosity bulk-fill composites. J. Dent. 2014, 42, 977–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, N.; Stark, K. Effect of different curing protocols on the mechanical properties of low-viscosity bulk-fill composites. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 19, 271–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karacolak, G.; Turkun, L.S.; Boyacioglu, H.; Ferracane, J.L. Influence of increment thickness on radiant energy and microhardness of bulk-fill resin composites. Dent. Mater. J. 2018, 37, 206–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moharam, L.M.; El-Hoshy, A.Z.; Abou-Elenein, K. The effect of different insertion techniques on the depth of cure and vickers surface micro-hardness of two bulk-fill resin composite materials. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2017, 9, e266–e271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, S.; Ayaz, İ.; Çetin Tuncer, N.; Barutçugil, Ç.; Dündar, A. Evaluation of polymerization shrinkage, microhardness, and depth of cure of different types of bulk-fill composites. J. Esthet. Restor. Dent. 2025, 37, 1920–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parasher, A.; Ginjupalli, K.; Somayaji, K.; Kabbinale, P. Comparative evaluation of the depth of cure and surface roughness of bulk-fill composites: An in vitro study. Dent. Med. Probl. 2020, 57, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skrinjaric, T.; Gorseta, K.; Bagaric, J.; Bucevic Sojcic, P.; Stojanovic, J.; Marks, L.A.M. Comparison of microhardness and depth of cure of six Bulk-Fill resin composites. J. Compos. Sci. 2025, 9, 418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Son, S.A.; Park, J.K.; Seo, D.G.; Ko, C.C.; Kwon, Y.H. How light attenuation and filler content affect the microhardness and polymerization shrinkage and translucency of bulk-fill composites? Clin. Oral Investig. 2017, 21, 559–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, H.W.; Loo, M.Y.; Alkhabaz, M.; Li, K.C.; Choi, J.J.E.; Barazanchi, A. Bulk-fill direct restorative materials: An in vitro assessment of their physio-mechanical properties. Oral 2021, 1, 75–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALShaafi, M.M.; Haenel, T.; Sullivan, B.; Labrie, D.; Alqahtani, M.Q.; Price, R.B. Effect of a broad-spectrum LED curing light on the Knoop microhardness of four posterior resin based composites at 2, 4 and 6-mm depths. J. Dent. 2016, 45, 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, D.; Yaman, P.; Dennison, J.; Neiva, G. Polymerization shrinkage and depth of cure of bulk fill flowable composite resins. Oper. Dent. 2014, 39, 441–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizzante, F.A.P.; Duque, J.A.; Duarte, M.A.H.; Mondelli, R.F.L.; Mendonça, G.; Ishikiriama, S.K. Polymerization shrinkage, microhardness and depth of cure of bulk fill resin composites. Dent. Mater. J. 2019, 38, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soto-Montero, J.; Nima, G.; Rueggeberg, F.A.; Dias, C.D.S.; Giannini, M. Influence of multiple peak light-emitting-diode curing unit beam homogenization tips on microhardness of resin composites. Oper. Dent. 2020, 45, 327–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, A.U.; Pandya, M.; Toh, W.S. Depth of cure of contemporary bulk-fill resin-based composites. Dent. Mater. J. 2016, 35, 503–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakupović, S.; Pervan, N.; Duratbegović, D.; Jakupović, V.; Muratović, E.; Kobašlija, S. Evaluation of the effect of different light-curing protocols on the microhardness of contemporary Bulk-Fill resin composites. Polymers 2025, 17, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fronza, B.M.; Ayres, A.; Pacheco, R.R.; Rueggeberg, F.A.; Dias, C.; Giannini, M. Characterization of inorganic filler content, mechanical properties, and light transmission of bulk-fill resin composites. Oper. Dent. 2017, 42, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ilie, N.; Hilton, T.J.; Heintze, S.D.; Hickel, R.; Watts, D.C.; Silikas, N.; Stansbury, J.W.; Cadenaro, M.; Ferracane, J.L. Academy of Dental Materials guidance-resin composites: Part I-mechanical properties. Dent. Mater. 2017, 33, 880–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silikas, N.; Eliades, G.; Watts, D.C. Light intensity effects on resin-composite degree of conversion and shrinkage strain. Dent. Mater. 2000, 16, 292–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferracane, J.L.; Mitchem, J.C.; Condon, J.R.; Todd, R. Wear and marginal breakdown of composites with various degrees of cure. J. Dent. Res. 1997, 76, 1508–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eliades, G.C.; Vougiouklakis, G.L.; Caputo, A.A. Degree of double bond conversion in light-cured composites. Dent. Mater. 1987, 3, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, W.D. Factors affecting the depth of cure of UV-polymerized composites. J. Dent. Res. 1980, 59, 800–808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wald, J.P.; Ferracane, J.L. A comparison of four modes of evaluating depth of cure of light-activated composites. J. Dent. Res. 1987, 66, 727–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferracane, J.L. Correlation between hardness and degree of conversion during the setting reaction of unfilled dental restorative resins. Dent. Mater. 1985, 1, 11–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rueggeberg, F.A.; Craig, R.G. Correlation of parameters used to estimate monomer conversion in a light-cured composite. J. Dent. Res. 1988, 67, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouschlicher, M.R.; Rueggeberg, F.A.; Wilson, B. Correlation of bottom-to-top surface microhardness and conversion ratios for a variety of resin composite compositions. Oper. Dent. 2004, 29, 698–704. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goncalves, F.; Azevedo, C.L.N.; Ferracane, J.L.; Braga, R.R. BisGMA/TEGDMA ratio and filler content effects onshrinkage stress. Dent. Mater. 2011, 27, 520–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Asmussen, E.; Peutzfeldt, A. Influence of UEDMA BisGMA and TEGDMA on selected mechanical properties of experimentalresin composites. Dent. Mater. 1998, 14, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halvorson, R.H.; Erickson, R.L.; Davidson, C.L. The effect of filler and silane content on conversion of resin-based composite. Dent. Mater. 2003, 19, 327–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sideridou, I.; Tserki, V.; Papanastasiou, G. Effect of chemical structure on degree of conversion in light-cured dimethacrylate-based dental resins. Biomaterials 2002, 23, 1819–1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlow, J.E.; Rueggeberg, F.A.; Labrie, D.; Sullivan, B.; Price, R.B. Transmission of violet and blue light through conventional (layered) and bulk cured resin-based composites. J. Dent. 2016, 53, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, N.; Hogg, C. Kinetic of light transmission during setting and aging of modern flowable bulk-fill composites. Materials 2024, 17, 4292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, N.; Bauer, H.; Draenert, M.; Hickel, R. Resin-based composite lightcured properties assessed by laboratory standards and simulated clinical conditions. Oper. Dent. 2013, 38, 159–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algamaiah, H.; Silikas, N.; Watts, D.C. Conversion kinetics of rapid photo-polymerized resin composites. Dent. Mater. 2020, 36, 1266–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, N.; Watts, D.C. Outcomes of ultra-fast (3 s) photo-cure in a RAFT-modified resin-composite. Dent. Mater. 2020, 36, 570–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, M.G.; Oliveira, D.C.R.S.; Sinhoreti, M.A.C.; Roulet, J.F.; Correr, A.B. The combination of CQ-amine and TPO increases the polymerization shrinkage stress and does not improve the depth of cure of bulk-fill composites. Oper. Dent. 2019, 44, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.J.; Moon, H.J.; Lim, B.S.; Lee, Y.K.; Rhee, S.H.; Yang, H.C. The effect of nanofiller on the opacity of experimental composites. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2007, 80, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shortall, A.C.; Palin, W.M.; Burtscher, P. Refractive index mismatch and monomer reactivity influence composite curing depth. J. Dent. Res. 2008, 87, 84–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Y.K.; Lu, H.; Powers, J.M. Measurement of opalescence of resin composites. Dent. Mater. 2005, 21, 1068–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzopardi, N.; Moharamzadeh, K.; Wood, D.J.; Martin, N.; van Noort, R. Effect of resin matrix composition on the translucency of experimental dental composite resins. Dent. Mater. 2009, 25, 1564–1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamareselvy, K.; Rueggeberg, F.A. Dynamic mechanical analysis of two crosslinked systems. Dent. Mater. 1994, 10, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmussen, E.; Peutzfeldt, A. Influence of pulse-delay curing on softening of polymer structures. J. Dent. Res. 2001, 80, 1570–1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimokawa, C.; Sullivan, B.; Turbino, M.L.; Soares, C.J.; Price, R.B. Influence of emission spectrum and irradiance on light curing of resin-based composites. Oper. Dent. 2017, 42, 537–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, M.G.; Roulet, J.F.; Sinhoreti, M.A.C.; Correr, A.B.; Oliveira, D. Light transmittance and depth of cure of a bulk fill composite based on the exposure reciprocity law. Braz. Dent. J. 2021, 33, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaud, P.-L.; Price, R.B.; Labrie, D.; Rueggeberg, F.A.; Sullivan, B. Localised irradiance distribution found in dental light curing units. J. Dent. 2014, 42, 129–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, Y.; Watts, D.C.; Boyd, D.; Price, R.B. Effect of curing light emission spectrum on the nanohardness and elastic modulus of two bulk-fill resin composites. Dent. Mater. 2016, 32, 535–550. [Google Scholar]

- Guerra, R.M.; Duran, I.; Ortiz, P. FTIR monomer conversion analysis of UDMA-based dental resins. J. Oral Rehabil. 1996, 23, 632–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, N. Microstructural dependence of mechanical properties and their relationship in modern resin-based composite materials. J. Dent. 2021, 114, 103829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Safty, S.; Akhtar, R.; Silikas, N.; Watts, D.C. Nanomechanical properties of dental resin-composites. Dent. Mater. 2012, 28, 1292–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masouras, K.; Akhtar, R.; Watts, D.C.; Silikas, N. Effect of filler size and shape on local nanoindentation modulus of resin-composites. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2008, 19, 3561–3566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Clearly Stated Aims/Objectives | Randomization | Detailed Explanation of Sample Size Calculation | Details of Compa- rison Group | Detailed Expla- nation of Methodology | Operator Details | Method of Measurement of Outcome | Proper Statistical Analysis | Presenta- tion of Results | Blinding | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdelwahed [62] | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Low |

| Aldhafyan [63] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Algamaiah [19] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Alrahlah [64] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| ALShaafi [78] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Altınok Uygun [36] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Low |

| Alzahrani [65] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Low |

| Arafa [37] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Conteras [21] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Cardoso [20] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Szalma [57] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Daugherty [39] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Derchi [22] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Elhejazi [66] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Medium |

| Fronza [55] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Gan [23] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Garcia [79] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Garoushi [40] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Georgiev [67] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | High |

| Gomes de Araújo-Neto [56] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Goncalves [41] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Gorrachi [43] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Gonzales Guarneri [42] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Medium |

| Jakupovic (2023) [68] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Jakupovic (2025) [83] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Javed [44] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Low |

| Ilie Stark 2014 [69] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Ilie Stark 2015 [70] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Karacolak [71] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | High |

| Kaya [24] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Lempel [57] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Li [58] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Maigaireh [25] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Makhdoom [26] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Marovic [27] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Miletic [45] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Medium |

| Moharam [72] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Ozciftci [46] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Özdemir [73] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Papadogiannis [47] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Par 2015 [59] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Par 2019 [28] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Medium |

| Parasher [74] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Renzai [48] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Medium |

| Rizzante [80] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Rocha (2017) [29] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Medium |

| Rocha (2022) [30] | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Low |

| Sampaio [49] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Shimokawa [31] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Siagian [32] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Medium |

| Skrinjaric [75] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Son [76] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Medium |

| Soto-Montero [81] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Strini [50] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Medium |

| Terada [60] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Thomaidis [33] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Torres [51] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Tsuzuki [34] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Varshney [35] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Medium |

| Wang [61] | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Yap [82] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Yeo [77] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Yıldırım [52] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Yokesh [53] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Zorzin [54] | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | Medium |

| Author | Monowave | Polywave | Material Dependent | No Statistical Signify |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algamiah [19] | X | |||

| Cardoso [20] | X | |||

| Conteras [21] | X | |||

| Derci [22] | X | |||

| Gan [23] | X | |||

| Kaya [24] | X | |||

| Maghaireh [25] | X | |||

| Makhdoom [26] | X | |||

| Marovic [27] | X | |||

| Par [28] | X | |||

| Rocha [29] | X | |||

| Rocha [30] | X | |||

| Shimokawa [31] | X | |||

| Siagian [32] | X | |||

| Thomaidis [33] | X | |||

| Tsuzuki [34] | X | |||

| Varshney [35] | X |

| Author | Monowave | Polywave | CQ | CQ + Ivocerin + TPO | CQ + Ivocerin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aldhafyan [63] | Y | - | Filtek One Bulk Fill SDR | Ok | - |

| Algamaiah [19] | Y | Y | Filtek One Bulk Fill | - | Power Flow |

| Al Shaafi [78] | - | Y | SonicFill | Tetric BulkFill | |

| Daugherty [39] | Y | - | SonicFill Beautiful Filtek Bulk Fill | Tetric Evo Ceram Bulk Fill | |

| Derci [22] | Y | Y | Filtek Bulk Fill | - | - |

| Fronza [55] | Y | Filtek Bulk Fill | - | - | |

| Elhejazi [66] | - | Y | Opus Bulk Fill | - | - |

| Gan [23] | Y | Y | All materials | All materials | - |

| Garcia [79] | Y | - | All materials | All materials | - |

| Georgiev [67] | - | Y | Filtek One Bulk Fill | - | - |

| Gonzales Guarneri [42] | - | Y | Filtek One Bulk Fill Filtek Bulk Fill flowable | - | Tetric PowerFill Tetric Powerflow |

| Kaya [24] | Y | Y | Beautiful | - | - |

| Lempel [57] | - | Y | Filtek One Bulk Fill | - | - |

| Maghaireh [25] | Y | Y | Filtek Bulk Fill X-tra Fill | Tetric Evo Ceram Bulk Fill | - |

| Makhdoom [26] | Y | Y | All materials | All materials | - |

| Ozciftci [46] | - | Y | Omnichroma flow Bulk Fill | - | - |

| Papadogiannis [47] | - | Y | X-tra Base X-tra Fill | Tetric Evo Ceram Bulk Fill | - |

| Parasher [74] | - | Y | Beautiful | Tetric Evo Ceram Bulk Fill | - |

| Shimokawa [31] | Y | Y | - | Tetric Evo Ceram Bulk Fill | - |

| Soto Montero [81] | - | Y | SonicFill | Tetric Evo Ceram Bulk Fill | - |

| Strini [50] | - | Y | Filtek One Bulk Fill | Tetric Evo Ceram Bulk Fill |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Thomaidis, S.; Masouras, K.; Papazoglou, E. Bulkfill Resin Composite Polymerization Efficiency by Monowave vs. Polywave Light Curing Units: A Systematic Review of In Vitro Studies. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010346

Thomaidis S, Masouras K, Papazoglou E. Bulkfill Resin Composite Polymerization Efficiency by Monowave vs. Polywave Light Curing Units: A Systematic Review of In Vitro Studies. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):346. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010346

Chicago/Turabian StyleThomaidis, Socratis, Konstantinos Masouras, and Efstratios Papazoglou. 2026. "Bulkfill Resin Composite Polymerization Efficiency by Monowave vs. Polywave Light Curing Units: A Systematic Review of In Vitro Studies" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010346

APA StyleThomaidis, S., Masouras, K., & Papazoglou, E. (2026). Bulkfill Resin Composite Polymerization Efficiency by Monowave vs. Polywave Light Curing Units: A Systematic Review of In Vitro Studies. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010346