Working from Home and Indoor Environmental Quality: A Scoping Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

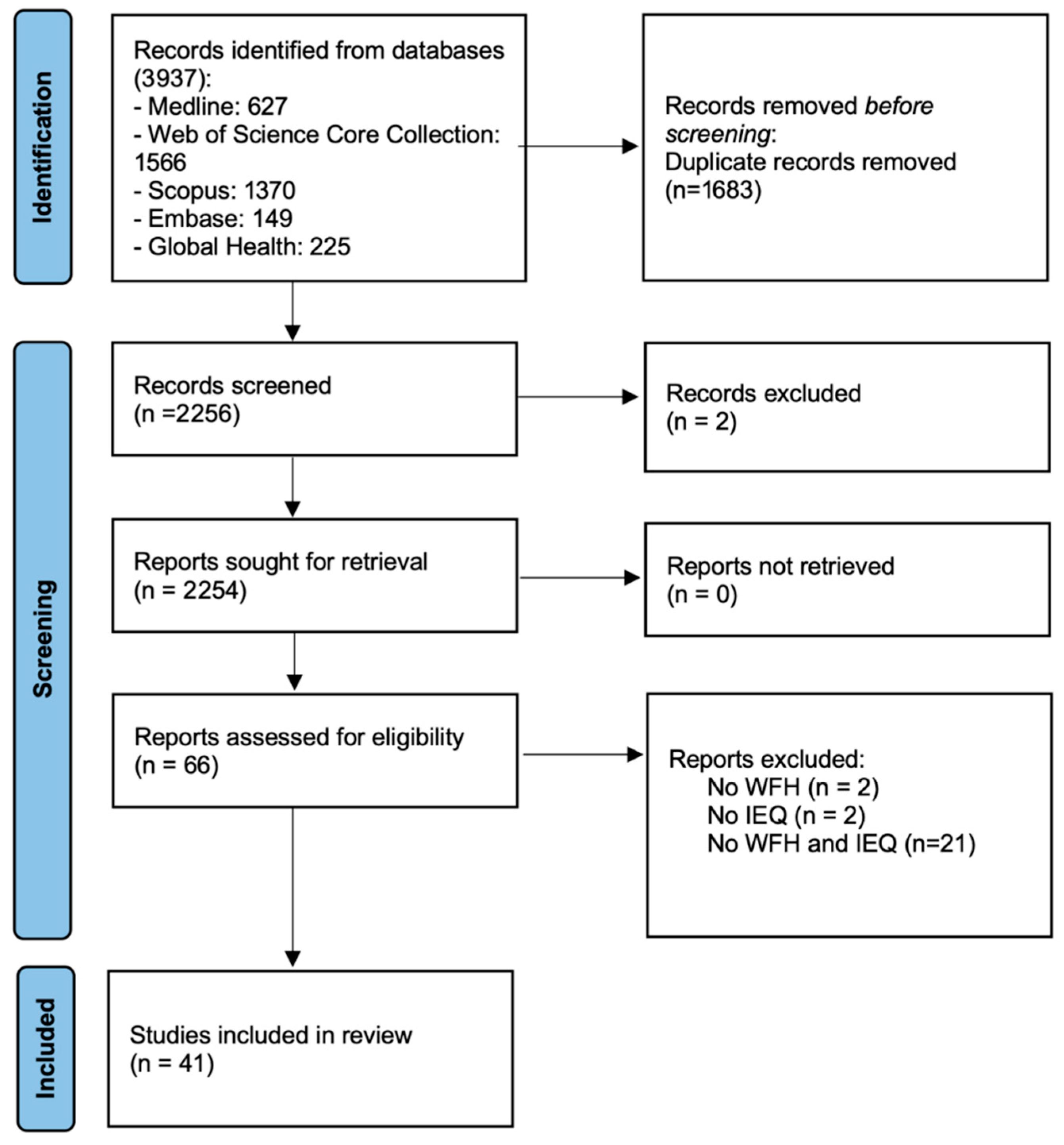

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

2.2. Search Strategy

2.3. Screening

2.4. Data Charting Process

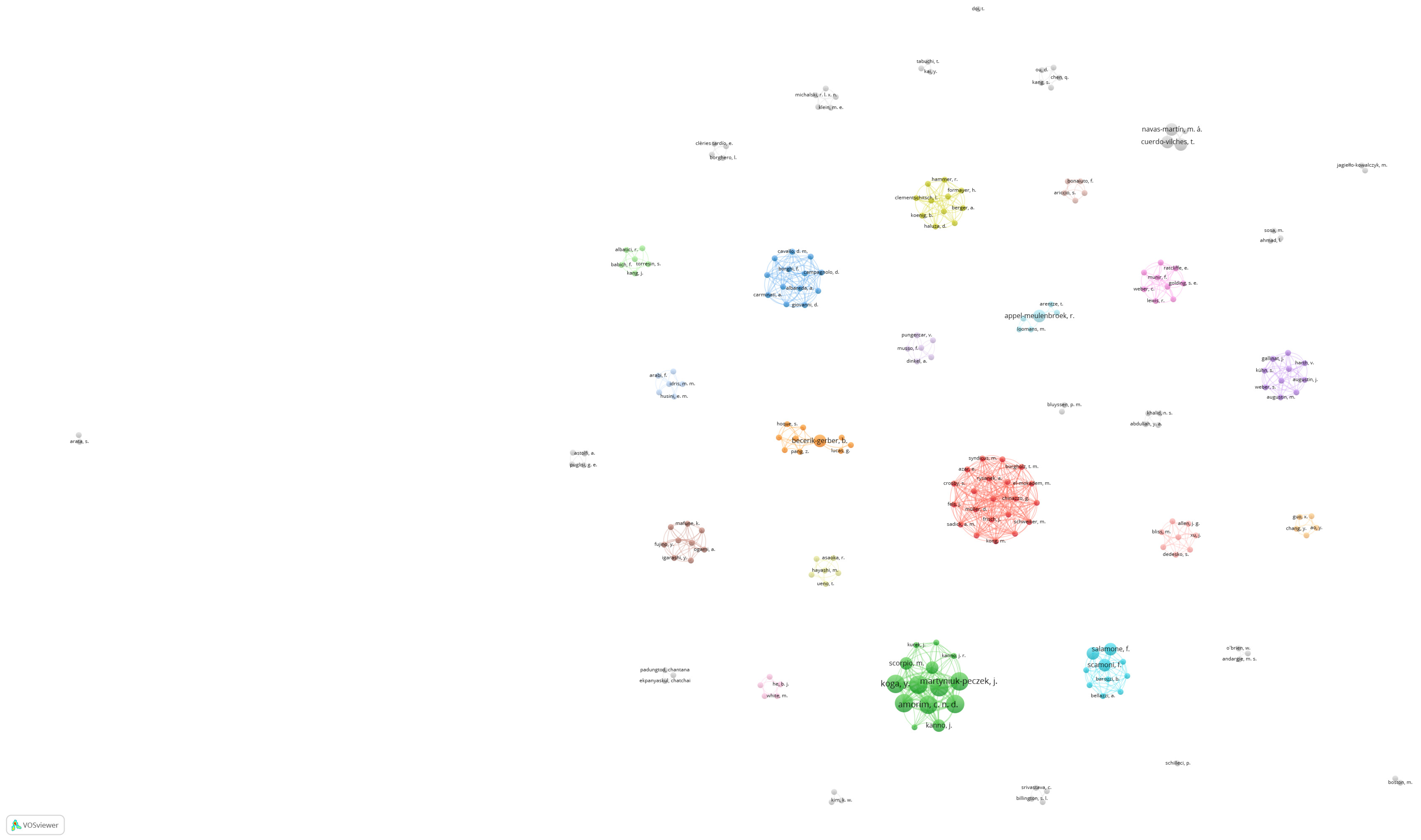

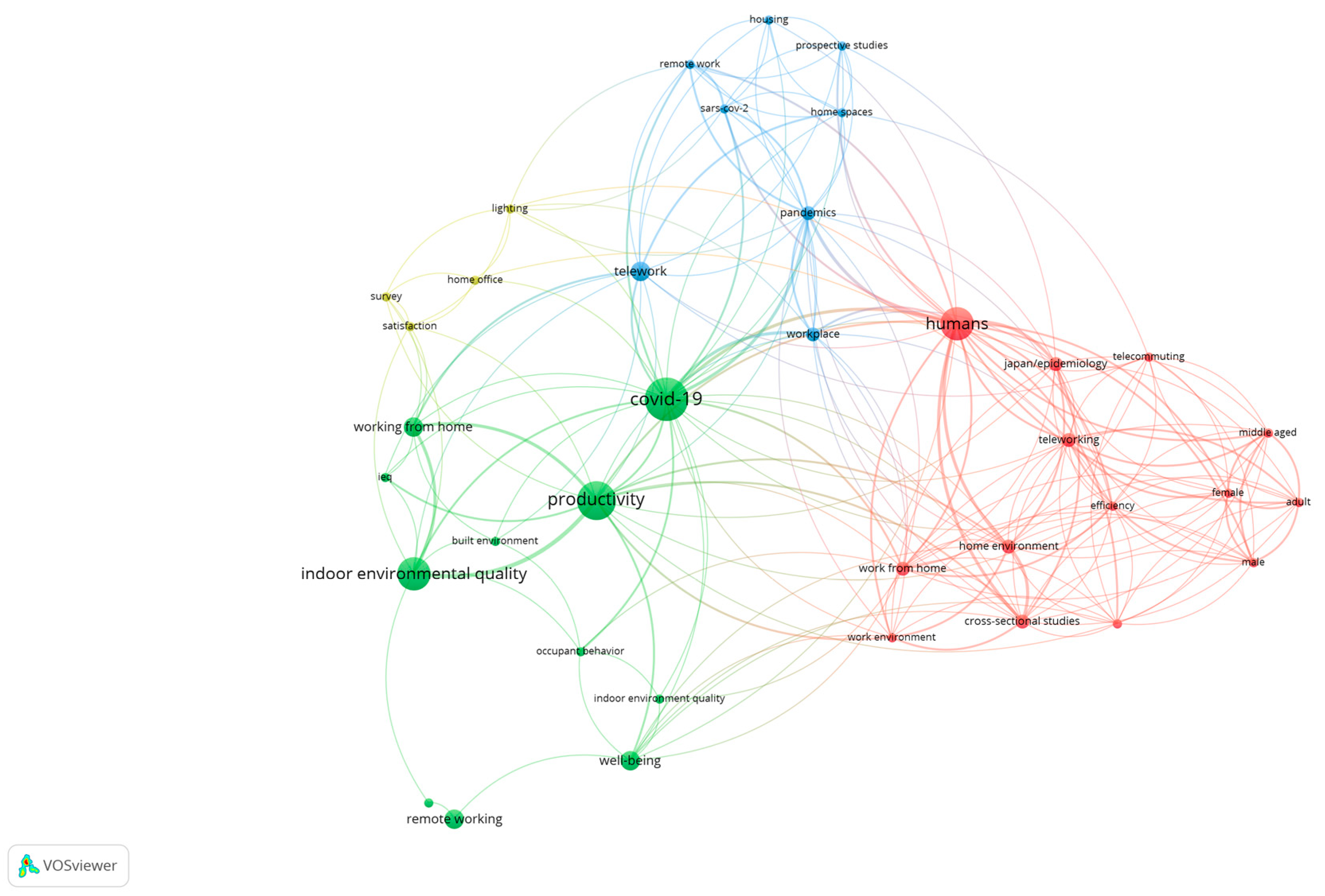

2.5. Data Analysis

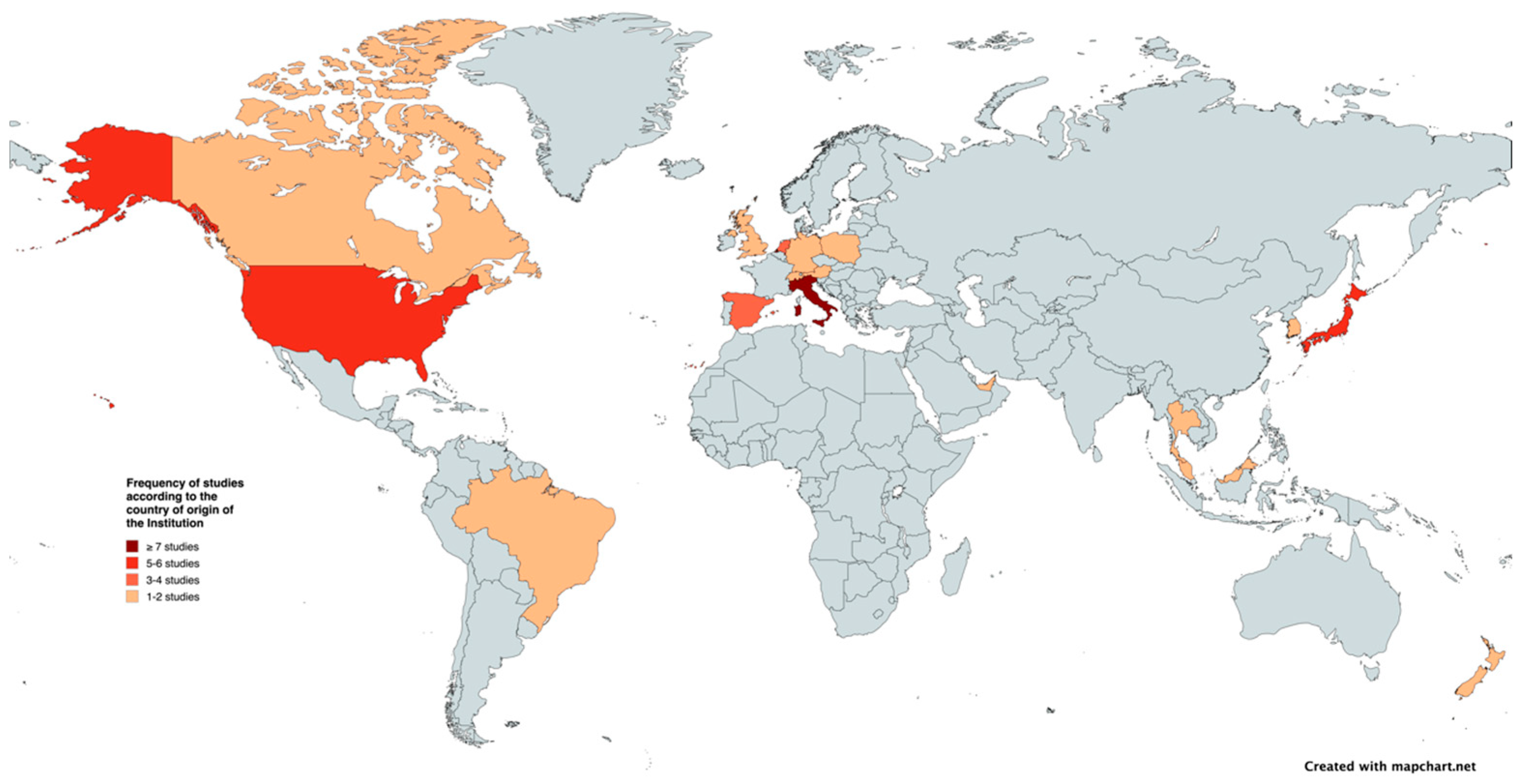

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- López-Igual, P.; Rodríguez-Modroño, P. Who Is Teleworking and Where from? Exploring the Main Determinants of Telework in Europe. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerdo-Vilches, T.; Navas-Martín, M.Á.; Oteiza, I. Working from Home: Is Our Housing Ready? Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asmussen, K.E.; Mondal, A.; Bhat, C.R. The Interplay between Teleworking Choice and Commute Distance. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2024, 165, 104690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doling, J.; Arundel, R. The Home as Workplace: A Challenge for Housing Research. Hous. Theory Soc. 2022, 39, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, E.A.; Rampasso, I.S.; Serafim, M.P.; Filho, W.L.; Anholon, R. Productivity Analysis in Work from Home Modality: An Exploratory Study Considering an Emerging Country Scenario in the COVID-19 Context. Work 2022, 72, 39–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mura, A.L.; Ariccio, S.; Villani, T.; Bonaiuto, F.; Bonaiuto, M. The Physical Environment in Remote Working: Development and Validation of Perceived Remote Workplace Environment Quality Indicators (PRWEQIs). Sustainability 2023, 15, 2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbu, I.; Sebarchievici, C. Aspects of Indoor Environmental Quality Assessment in Buildings. Energy Build. 2013, 60, 410–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinemann, A. Human Exposure, Health Hazards, and Environmental Regulations. Environ. Impact Assess Rev. 2004, 24, 695–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godish, T. Indoor Environmental Quality; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Navas-Martín, M.Á.; Ovalle-Perandones, M.-A.; López-Bueno, J.A.; Sánchez, G.; Díaz, J.; Linares, C. Population Heat Adaptation Through the Relationship Between Temperature and Mortality in the Context of Global Warming on Health: A Scoping Review. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 908, 168441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PRISMA PRISMA for Scoping Reviews. Available online: https://www.prisma-statement.org/scoping (accessed on 16 December 2022).

- Peters, M.D.J.; Marnie, C.; Tricco, A.C.; Pollock, D.; Munn, Z.; Alexander, L.; McInerney, P.; Godfrey, C.M.; Khalil, H. Updated Methodological Guidance for the Conduct of Scoping Reviews. JBI Evid. Synth. 2020, 18, 2119–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navas-Martín, M.Á.; Jiménez-Planet, V.; Castaño-Rosa, R.; Cuerdo-Vilches, T. Indoor Environmental Quality of Telework Spaces in Homes: A Scoping Review Protocol; Center for Open Science: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.D.J.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A.C.; Khalil, H. Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Munn, Z., Eds.; JBI: Adelaide, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Messenger, J.C.; Gschwind, L. Three Generations of Telework: New ICTs and the (R)Evolution from Home Office to Virtual Office. New Technol. Work Employ 2016, 31, 195–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopp, O. JabRef. Available online: https://www.jabref.org/ (accessed on 17 May 2023).

- Khangura, S.; Konnyu, K.; Cushman, R.; Grimshaw, J.; Moher, D. Evidence Summaries: The Evolution of a Rapid Review Approach. Syst. Rev. 2012, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardin, L. El Análisis de Contenido; Ediciones Akal: Madrid, Spain, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Granovetter, M.S. The Strength of Weak Ties. Am. J. Sociol. 1973, 78, 1360–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.P.; Everett, M.G. A Graph-Theoretic Perspective on Centrality. Soc. Netw. 2006, 28, 466–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, L.C. Centrality in Social Networks Conceptual Clarification. Soc. Netw. 1978, 1, 215–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuerdo-Vilches, T.; Navas-Martín, M.Á.; March, S.; Oteiza, I. Adequacy of Telework Spaces in Homes during the Lockdown in Madrid, According to Socioeconomic Factors and Home Features. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andargie, M.S.; Touchie, M.; O’Brien, W. Case Study: A Survey of Perceived Noise in Canadian Multi-Unit Residential Buildings to Study Long-Term Implications for Widespread Teleworking. Build. Acoust. 2021, 28, 443–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puglisi, G.E.; Di Blasio, S.; Shtrepi, L.; Astolfi, A. Remote Working in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results from a Questionnaire on the Perceived Noise Annoyance. Front. Built. Environ. 2021, 7, 688484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Shin, H.K.; Kim, K.W. Remote Work during the COVID-19 Pandemic and Perception of Indoor Environment: A Focus on Acoustic Environment. J. Acoust. Soc. Korea 2023, 42, 627–636. [Google Scholar]

- Torresin, S.; Albatici, R.; Aletta, F.; Babich, F.; Oberman, T.; Kang, J. Associations between Indoor Soundscapes, Building Services and Window Opening Behaviour during the COVID-19 Lockdown. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2022, 43, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scamoni, F.; Salamone, F.; Scrosati, C. A Survey on Perceived Indoor Acoustic Quality by Workers from Home during COVID-19 Lockdown in Italy. Buildings 2023, 13, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husini, E.M.; Arabi, F.; Shamri, S.L.; Manaf, A.A.; Idris, M.M.; Jamaludin, J. Resillient living by optimizing the building façade in designing post-COVID housing. Plan. Malays. 2022, 20, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, N.S.; Abdullah, Y.A.; Nasrudin, N.; Kholid, M.F. How does the indoor environment affect mental health when working remotely? Plan. Malays. 2022, 20, 287–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awada, M.; Becerik-Gerber, B.; Lucas, G.; Roll, S.C. Associations Among Home Indoor Environmental Quality Factors and Worker Health While Working from Home During COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Eng. Sustain. Build. Cities 2021, 2, 041001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz, M.A.; Bluyssen, P.M. Profiling Office Workers Based on Their Self-Reported Preferences of Indoor Environmental Quality and Psychosocial Comfort at Their Workplace during COVID-19. Build. Environ. 2022, 211, 108742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boegheim, B.; Appel-Meulenbroek, R.; Yang, D.; Loomans, M. Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) in the Home Workplace in Relation to Mental Well-Being. Facilities 2022, 40, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, C.; Hedge, A. Ergonomic Lighting Considerations for the Home Office Workplace. Work 2022, 71, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, B.; Boston, M. Residential Built Environment and Working from Home: A New Zealand Perspective during COVID-19. Cities 2022, 129, 103844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umishio, W.; Kagi, N.; Asaoka, R.; Hayashi, M.; Sawachi, T.; Ueno, T. Work Productivity in the Office and at Home during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Cross-Sectional Analysis of Office Workers in Japan. Indoor Air 2022, 32, e12913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peixoto, N.G.M.; Rafael Ferreira, L.; Klein, M.E.; Michalski, R.L.X.N.; Monteiro, L.M. Influence of Soundscape on Quality of Work from Home during the Second Phase of the Pandemic in Brazil. Noise Mapp. 2023, 10, 20220175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, C.; Golding, S.E.; Yarker, J.; Teoh, K.; Lewis, R.; Ratcliffe, E.; Munir, F.; Wheele, T.; Windlinger, L. Work Fatigue during COVID-19 Lockdown Teleworking: The Role of Psychosocial, Environmental, and Social Working Conditions. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1155118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stachura, E.J.; Jagiełło-Kowalczyk, M. Housing and the Pandemic: How Has COVID-19 Influenced Residents’ Needs and Aspirations? Real Estate Manag. Valuat. 2023, 31, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Kawakubo, S.; Arata, S. Study on Residential Environment and Workers’ Personality Traits on Productivity While Working from Home. Build. Environ. 2022, 212, 108787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salamone, F.; Barozzi, B.; Bellazzi, A.; Belussi, L.; Danza, L.; Devitofrancesco, A.; Ghellere, M.; Meroni, I.; Scamoni, F.; Scrosati, C. Working from Home in Italy during COVID-19 Lockdown: A Survey to Assess the Indoor Environmental Quality and Productivity. Buildings 2021, 11, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okawara, M.; Ishimaru, T.; Igarashi, Y.; Matsugaki, R.; Mafune, K.; Nagata, T.; Tsuji, M.; Ogami, A.; Fujino, Y. Health and Work Performance Consequences of Working from Home Environment: A Nationwide Prospective Cohort Study in Japan. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2023, 65, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wu, H.; Chen, Y.; Chang, Y.; Ao, Y. Gauging the Impact of Personal Lifestyle, Indoor Environmental Quality and Work-Related Factors on Occupant Productivity When Working from Home. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 3713–3730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doi, T. The Relationship between the Living Environment and Remote Working: An Analysis Using the SHEL Model. PeerJ 2024, 12, e17301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasquez, N.G.; Amorim, C.N.D.; Matusiak, B.; Kanno, J.; Sokol, N.; Martyniuk-Peczek, J.; Sibilio, S.; Scorpio, M.; Koga, Y. Lighting Conditions in Home Office and Occupant’s Perception: Exploring Drivers of Satisfaction. Energy Build. 2022, 261, 111977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, C.N.D.; Vasquez, N.G.; Matusiak, B.; Kanno, J.; Sokol, N.; Martyniuk-Peczek, J.; Sibilio, S.; Koga, Y.; Ciampi, G.; Waczynska, M. Lighting Conditions in Home Office and Occupant’s Perception: An International Study. Energy Build. 2022, 261, 111957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, F.; White, M.; Memon, S.; He, B.J.; Yang, S. The Application of Human-Centric Lighting in Response to Working from Home Post-COVID-19. Buildings 2023, 13, 2532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergefurt, L.; Appel-Meulenbroek, R.; Arentze, T. How Physical Home Workspace Characteristics Affect Mental Health: A Systematic Scoping Review. Work.-A J. Prev. Assess. Rehabil. 2023, 76, 489–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schilleci, P. Exploring the Impact of the Physical Work Environment on Service Employees: An Analysis of Literature. J. Facil. Manag. 2023, 21, 717–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manu, S.; Burgholz, T.M.; Nabilou, F.; Rewitz, K.; El-Mokadem, M.; Yadav, M.; Chinazzo, G.; Rupp, R.F.; Azar, E.; Syndicus, M.; et al. A State-of-the-Art, Systematic Review of Indoor Environmental Quality Studies in Work-from-Home Settings. Build. Environ. 2024, 259, 111652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamori, S.; Tabuchi, T.; Kai, Y. Association between the Telecommuting Environment and Somatic Symptoms among Teleworkers in Japan. J. Occup. Health 2024, 66, uiad014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffernicht, S.K.; Tuerk, A.; Kogler, M.; Berger, A.; Scharf, B.; Clementschitsch, L.; Hammer, R.; Holzer, P.; Formayer, H.; Koenig, B.; et al. Heat vs. Health: Home Office under a Changing Climate. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clèries Tardío, E.; Ortiz, J.; Borghero, L.; Salom, J. What Is the Temperature Acceptance in Home-Office Households in the Winter? Buildings 2023, 13, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghi, F.; Spinazzè, A.; Fanti, G.; Albareda, A.; Ghiraldini, J.; Campagnolo, D.; Carminati, A.; Keller, M.; Rovelli, S.; Zellino, C.; et al. Exposure to Airborne Particulate Matter in Working from Office and Working from Home Employees. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2024, 35, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.S.; Parikh, S.; Dedesko, S.; Bliss, M.; Xu, J.; Zanobetti, A.; Miller, S.L.; Allen, J.G. Home Indoor Air Quality and Cognitive Function over One Year for People Working Remotely during COVID-19. Build. Environ. 2024, 257, 111551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pungercar, V.; Zhan, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Musso, F.; Dinkel, A.; Pflug, T. A New Retrofitting Strategy for the Improvement of Indoor Environment Quality and Energy Efficiency in Residential Buildings in Temperate Climate Using Prefabricated Elements. Energy Build. 2021, 241, 110951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekpanyaskul, C.; Padungtod, C.; Kleebbua, C. Home as a New Physical Workplace: A Causal Model for Understanding the Inextricable Link between Home Environment, Work Productivity, and Well-Being. Ind. Health 2022, 61, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiyasat, R.; Sosa, M.; Ahmad, L. Use of Work-Space at Home under COVID-19 Conditions in the UAE. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2023, 30, 3142–3159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, E.T.; Bae, Y.; Birkett, R.; Sharma, A.M.; Zhang, R.; Fisch, K.M.; Funk, W.; Mestan, K.K. Cord Blood Adductomics Reveals Oxidative Stress Exposure Pathways of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funk, W.E.; Montgomery, N.; Bae, Y.; Chen, J.; Chow, T.; Martinez, M.P.; Lurmann, F.; Eckel, S.P.; McConnell, R.; Xiang, A.H. Human Serum Albumin Cys34 Adducts in Newborn Dried Blood Spots: Associations with Air Pollution Exposure During Pregnancy. Front. Public Health 2021, 9, 730369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voller, S.B.; Chock, S.; Ernst, L.M.; Su, E.; Liu, X.; Farrow, K.N.; Mestan, K.K. Cord Blood Biomarkers of Vascular Endothelial Growth (VEGF and SFlt-1) and Postnatal Growth: A Preterm Birth Cohort Study. Early Hum. Dev. 2014, 90, 195–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mestan, K.K.; Gotteiner, N.; Porta, N.; Grobman, W.; Su, E.J.; Ernst, L.M. Cord Blood Biomarkers of Placental Maternal Vascular Underperfusion Predict Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia-Associated Pulmonary Hypertension. J. Pediatr. 2017, 185, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrote Sanchez, D.; Gomez Parra, N.; Ozden, C.; Rijkers, B.; Viollaz, M.; Winkler, H. Who on Earth Can Work from Home? World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Aksoy, C.G.; Barrero, J.M.; Bloom, N.; Davis, S.J.; Dolls, M.; Zarate, P. Working from Home around the Globe: 2023 Report; CESifo GmbH: Munich, Germany, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka, Y.; Itani, O.; Nakajima, S.; Matsumoto, Y.; Kaneita, Y. Impact of Teleworking Practices on Presenteeism: Insights from a Cross-Sectional Study of Japanese Teleworkers During COVID-19. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Iglesias, J.J.; Gómez-Salgado, J.; Apostolo, J.; Rodrigues, R.; Costa, E.I.; Ruiz-Frutos, C.; Martínez-Isasi, S.; Fernández-García, D.; Vilches-Arenas, Á. Presenteeism and Mental Health of Workers during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1224332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.; Colquhoun, H.; Kastner, M.; Levac, D.; Ng, C.; Sharpe, J.P.; Wilson, K.; et al. A Scoping Review on the Conduct and Reporting of Scoping Reviews. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2016, 16, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, M.T.; Rajić, A.; Greig, J.D.; Sargeant, J.M.; Papadopoulos, A.; Mcewen, S.A. A Scoping Review of Scoping Reviews: Advancing the Approach and Enhancing the Consistency. Res. Synth. Methods 2014, 5, 371–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| First Author | Year | Country | Aims | Keywords | Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pungercar | 2021 | Germany | Analyzing the indoor environment quality of a typical 1960s semi-detached house in Germany before and after our retrofitting strategy | Energy saving; Indoor environment quality; Residential buildings; Retrofit; Window machine | Energy efficiency |

| Andargie | 2021 | Canada | Using the COVID-19 pandemic experience to investigate how acoustic conditions in multi-unit residential buildings affect occupants’ subjective wellbeing and work productivity for a large-scale implementation of teleworking | COVID-19 | |

| Awada | 2021 | USA | Knowing the satisfaction of office workers with indoor environmental quality (IEQ) factors of their houses where work activities took place and associate these factors with mental and physical health | Indoor environmental quality (IEQ); health; well-being; COVID-19; work from home, indoor environment quality; occupant behavior | COVID-19 |

| Pang | 2021 | USA | Investigating how working from home (WFH) has affected occupant well-being in residential buildings in the context of the coronavirus disease 2020 (COVID-19) pandemic. | occupant well-being; built environment; indoor environmental quality, COVID-19, occupant-centric design and operation; international survey; building; occupant behavior; occupant productivity | COVID-19 |

| Salamone | 2021 | Italy | Analyzing the Indoor Environmental Quality (IEQ) of home offices and the productivity of workers during the Coronavirus pandemic | working from home; survey; questionnaire; indoor environmental quality; COVID-19 lockdown; productivity | COVID-19 |

| Puglisi | 2021 | Italy | Extending outcomes to the environments where remote working is performed as its practice is getting more and more common | well-being; noise annoyance; office acoustics; remote working; noise sensitivity | Noise |

| Cuerdo-Vilches | 2021 | Spain | Contributing to the debates on the effective application of telework, its real application capacities, the subjective perception and the level of satisfaction of these workspaces according to its practitioners, and how they affect their socioeconomic qualities in real practice | COVID-19 housing confinement; Telework; Home spaces; Gender; Incomes; User environmental perception; COVID-19 confinement; Workspace; Telecommuting | COVID-19 |

| Cuerdo-Vilches | 2021 | Spain | Analyzing in depth the nature of these teleworking spaces in homes, and their adequacy, considering multiple factors, in the context of confinement | COVID-19; confinement; telework; comfort; home spaces; telework space adequacy index (TSAI), photo; narrative; mixed-method; remote work | COVID-19 |

| Khalid | 2022 | Malaysia | Understanding the role IEQ plays in ensuring comfort when working from home, as the practice could have a negative or positive impact depending on the IEQ. | Indoor Environment; Mental Health; Remote Working; Pandemic | COVID-19 |

| Husini | 2022 | Malaysia | Providing healthy indoor strategies and passive building performance for open-plan home-office design, to investigate the open-plan home design with optimum thermal performance based on the passive indoor environment, and to examine the bioclimatic response and energy efficiency of home-office design during the pandemic | Passive indoor performance; Daylighting; open-plan home | COVID-19 |

| Mayer | 2022 | New Zealand | While some studies have considered WFH in New Zealand, no existing literature sources that explicitly examine WFH experiences concerning the WFH environment were found. This study aims to provide an initial insight into this area. | Telework; Working from home; New Zealand; Built environment; Resilient; infrastructure; COVID-19 pandemic; | COVID-19 |

| Umishio | 2022 | Japan | Studying was to investigate the link between different work styles and work environments and productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic, and to explore ways to improve productivity in the New Normal era | Air Pollution; Indoor; COVID-19; Cross-Sectional Studies; Efficiency; Home Environment; Humans; Japan/epidemiology; Pandemics; Workplace; PM2.5; Productivity; Work, environment; work from home; work in the office; | COVID-19 |

| Ortiz | 2022 | Netherlands | Clustering office workers working at home based on their self-reported preferences for IEQ and psychosocial comfort at their most used workspace and to identify these preferences and needs of workers during the COVID-19 pandemic | Workplace; Preferences and needs; Health and comfort; COVID-19; | COVID-19 |

| Torresin | 2022 | UK | Understanding the mutual interrelations between indoor soundscapes, building occupants, building services and window opening behaviour. | COVID-19 | |

| Kawakubo | 2022 | Japan | Elucidating the relationships among residential environment, personality traits, and productivity while working from home. | Telework; Working from home; COVID-19; Productivity; Residential environment; Personality traits; | COVID-19 |

| Vasquez | 2022 | Denmark | Investigating the drivers of participants’ satisfaction with the lighting conditions at the home office | Home office; Lighting; Visual environment; Perception; Satisfaction; Survey | Lighting |

| Boegheim | 2022 | Netherlands | Exploring the effects of the IEQ at the home workplace on employee mental health. | Design; Mental health; Employee health; Field study; Indoor environmental quality; Home office workplace | Health |

| McKee | 2022 | USA | Reviewing and discussing various lighting sources and their ergonomic impacts on the population of office employees now working from home. Specifically addressing the impacts of electronic light from screens, daylight, and task lighting’s impact on health and well-being in the frame of the COVID-19 pandemic | Screen light; daylight; home work environment; COVID-19; remote work; task lighting | COVID-19 |

| Amorim | 2022 | Brazil | Defining the current limitations of home offices in providing a resilient visual environment | Lighting | |

| Hiyasat | 2022 | United Arab Emirates | Assessing user satisfaction of workspaces modified at home in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, thereby analyzing the flexibility of modern homes in the twenty-first century in the United Arab Emirates. | Pandemic; COVID-19; Satisfaction; Working space; Living space; Interior design | Satisfaction |

| Bergefurt | 2023 | Netherlands | Providing insights in previously studied relationships between the physical home-workspace and mental health and to identify measures for both using a systematic scoping review | COVID-19 pandemic; Workplace; psychological phenomena; teleworking | Review |

| Schaffernicht | 2023 | Austria | Modeling thermal comfort changes in people working at home in three Austrian cities (Vienna, Innsbruck, and Graz) during the next decades until 2090. We present findings based on (I) an inter-disciplinary literature search and (II) indoor and outdoor climate simulations for actual and future climate scenarios. | Home work; Climate simulations; Austria; Built environment; Urban Heat island effect; Health | Thermal comfort |

| Schilleci | 2023 | Italy | Providing a clear understanding of the main and most recent issues discussed in academic literature regarding the impact of the physical work environment, particularly offices, on service employees’ internal responses, behaviors, and outcomes, highlighted by the COVID-19 emergency. | Physical work environment; Service employees; Service environment; Servicescape; Systematic literature review; Workplace design | Review |

| Stachura | 2023 | Poland | Presenting how the phenomena mentioned above have influenced the housing environment and residential preferences and trends that may follow. | housing environment; COVID pandemic; residential needs and preferences | COVID-19 |

| Weber | 2023 | Switzerland | Examining the relationships between the psychosocial, environmental, and social working conditions of teleworking during the first COVID-19 lockdown and work fatigue. Specifically, the study examined teleworkers’ physical work environment (e.g., if and how home office space is shared, crowding, and noise perceptions) as predictors of privacy fit and the relationship between privacy fit, childcare, psychosocial working conditions (job demand, job control, and job change management), and work fatigue | COVID-19; teleworking; home office; office design; privacy; psychosocial working conditions; lockdown; burnout | COVID-19 |

| Ekpanyaskul | 2023 | Thailand | Evaluating the chronology of the effects of work hazards at home on factors such as workers’ health, productivity, and well-being | Work style; Working-from-home; Work environment; Occupational stress; Sick house syndrome, Productivity; Well-being | IEQ |

| Weber | 2023 | Germany | Investigating the association between the subjective evaluation of home environment and self-reported levels of anxiety using population data from the Hamburg City Health Study | Anxiety; subjective evaluation of home environment; housing; indoor lifestyle; Hamburg City Health Study; mental well-being | Health |

| Peixoto | 2023 | Brazil | Assessing the impact of the soundscape in the home office environment during the pandemic | Indoor sounds; outdoor sounds; sound perception; occupational exposure | COVID-19 |

| Okawara | 2023 | Japan | The physical work environment while working from home (WFH) is a key component of WFH, which, if inadequate, can impair workers’ health and work functioning. This paper investigates environmental factors in WFH and worsening of work functioning | work from home; telework; work environment; presenteeism; prospective cohort study; observational study | Productivity |

| Guo | 2023 | USA | Identifying key causal factors of occupant productivity when working from home. | Personal lifestyle; Indoor environmental quality; Work-related factor; Satisfaction; Productivity; Working from home; Offices; Regression model | Productivity |

| Mura | 2023 | Italy | Developing a tool named Perceived Remote Workplace Environment Quality Indicators (PRWEQIs) to study the impact of the remote work environment on worker well-being | spatial-physical comfort; remote working; sustainable workplace; remote studying; scale development and validation; perceived comfort; PRWEQIs | Tool |

| Clèries Tardío | 2023 | Spain | Understanding occupants’ accepted Indoor Environmental Quality values in winter based on self-reported comfort. | thermal comfort; human perception; indoor environmental quality; building energy use | Thermal comfort |

| Roberts | UK | Understanding what lighting conditions are currently present within the WFH environments in terms of safety and visual clarity. | circadian lighting; biological potency; melanopic lux; lux level; uniformity | Lighting | |

| Park | 2023 | South Korea | Investigating the relationship between indoor noise perception and remote work during the pandemic. The study assessed how people who worked from home perceived indoor noise, and how it related with their work performance and job satisfaction. | COVID-19 | |

| Scamoni | 2023 | Italy | Investigating buildings’ year of construction, presence of other people in the home, and comparison between acoustic perception before and during the pandemic. | house typology; acoustic quality; survey; well-being; COVID-19 lockdown; working from home | COVID-19 |

| Doi | 2024 | Japan | Investigating the relationship of living environment factors with satisfaction, work engagement, perceived productivity, and stress among teleworkers. | Work from home; Telecommuting; SHEL model; Living environment | Productivity |

| Borghi | 2024 | Italy | Quantitatively evaluating the differences, in terms of exposure to PM (particulate matter), between WFO (working-from-office) and WFH (working-from-home) conditions | Agile working; remote working; non-occupational exposure; risk factors; human health | Air quality |

| Kanamori | 2024 | Japan | This study aimed to clarify the association between telecommuting environments and somatic symptoms among teleworkers in Japan | teleworking, home environment, somatic symptoms, occupational health | Health |

| Manu | 2024 | Canada | Understanding the influence of indoor environmental quality (IEQ) on workers’ well-being and productivity. | Thermal; Indoor air quality; Visual; Acoustics; Well-being; Productivity | Review |

| Young | 2024 | USA | Understanding the impact of indoor air quality (IAQ) in homes on the cognitive performance of people working from home. | Buildings; IEQ; Occupational; Productivity; Remote; Ventilation | Air quality |

| Srivastava | 2024 | USA | Evaluating home and office workplaces using a comparative approach and a data-driven framework. The computational models in this study aim to predict the impact of 10 workplace spatial attributes on perceptions of comfort, work performance, and aspects of well-being, such as sense of connectedness and physical activity. | Connectedness; Indoor environmental quality; productivity; return to office; worker physical activity; workplace comfort | Productivity |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Navas-Martín, M.Á.; Jiménez-Planet, V.; Cuerdo-Vilches, T. Working from Home and Indoor Environmental Quality: A Scoping Review. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010250

Navas-Martín MÁ, Jiménez-Planet V, Cuerdo-Vilches T. Working from Home and Indoor Environmental Quality: A Scoping Review. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):250. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010250

Chicago/Turabian StyleNavas-Martín, Miguel Ángel, Virginia Jiménez-Planet, and Teresa Cuerdo-Vilches. 2026. "Working from Home and Indoor Environmental Quality: A Scoping Review" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010250

APA StyleNavas-Martín, M. Á., Jiménez-Planet, V., & Cuerdo-Vilches, T. (2026). Working from Home and Indoor Environmental Quality: A Scoping Review. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 250. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010250