Fatigue Life Prediction and Reliability Analysis of Reinforced Concrete Bridge Decks Based on an XFEM–ANN–Monte Carlo Hybrid Framework

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

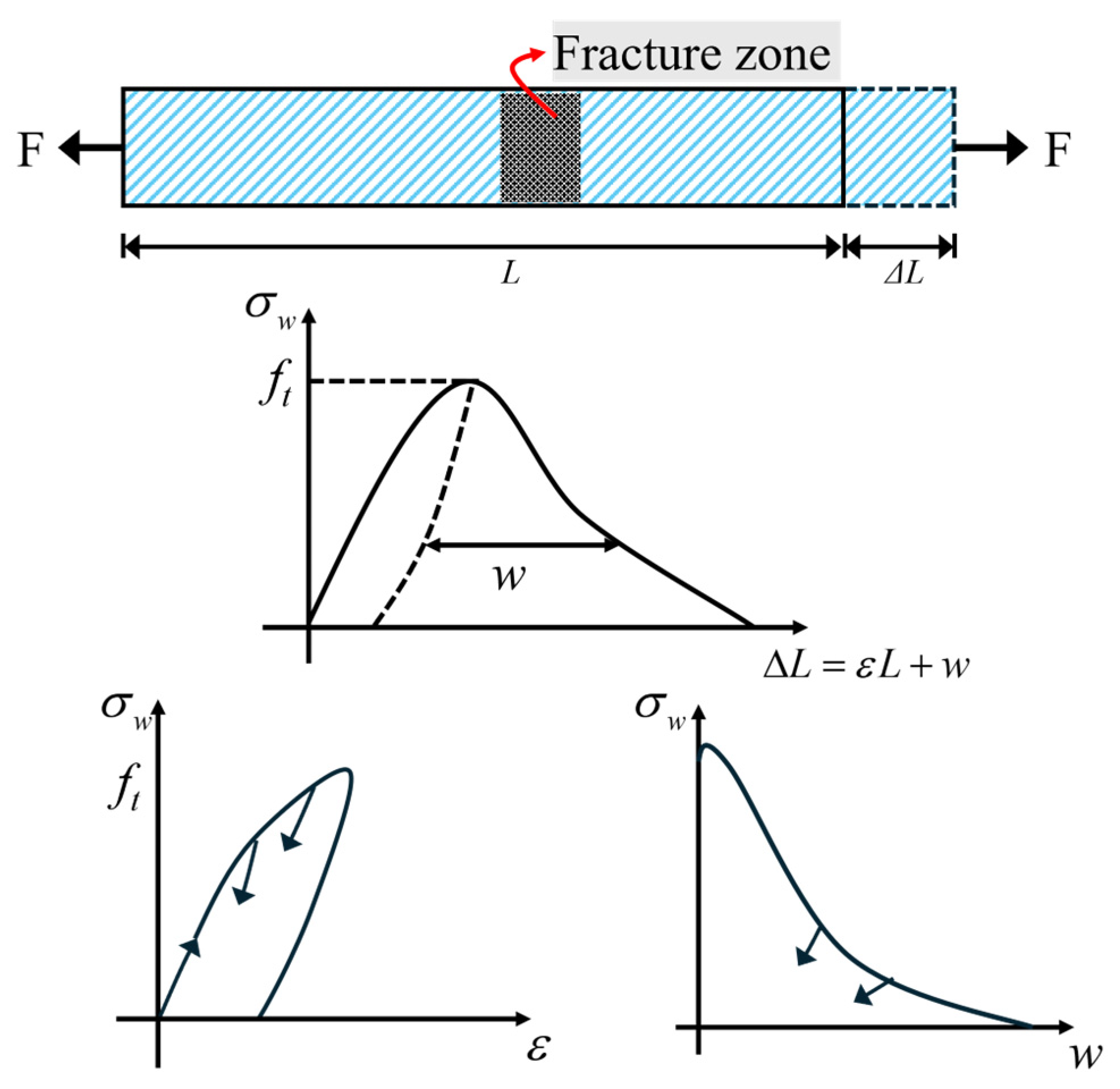

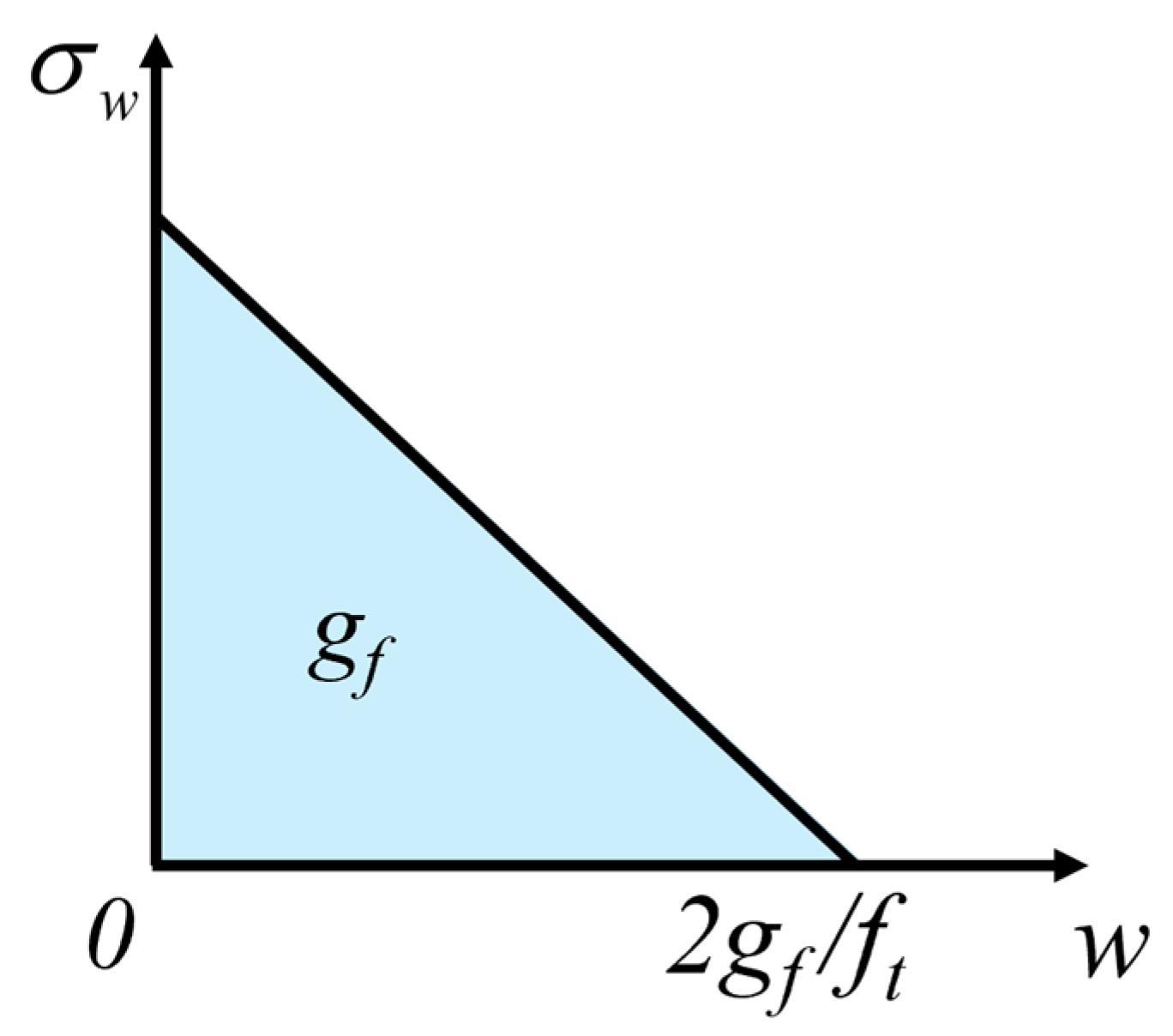

2.1. Virtual Crack Model

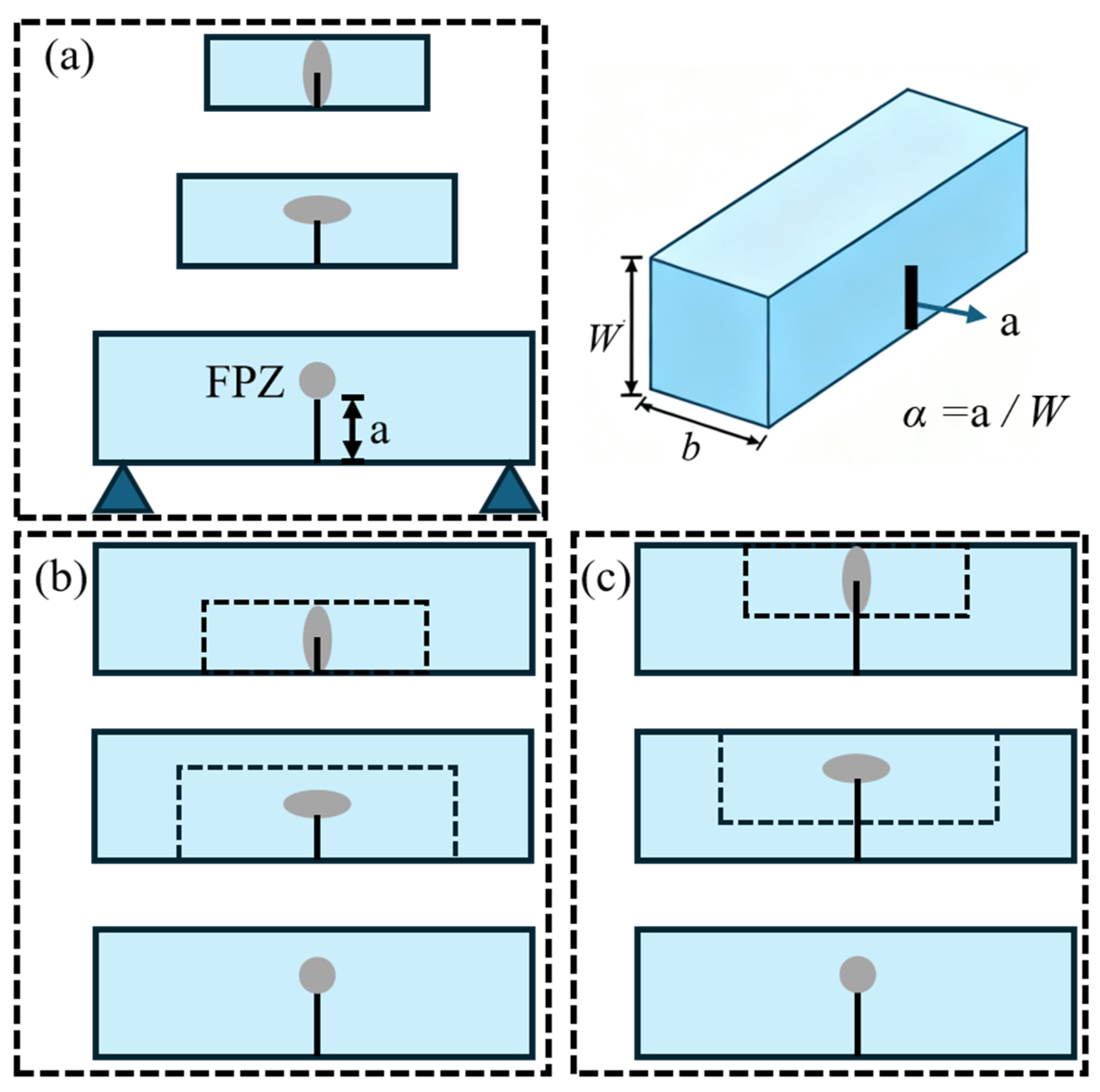

2.2. Fatigue Crack Growth and Size Effect Correction

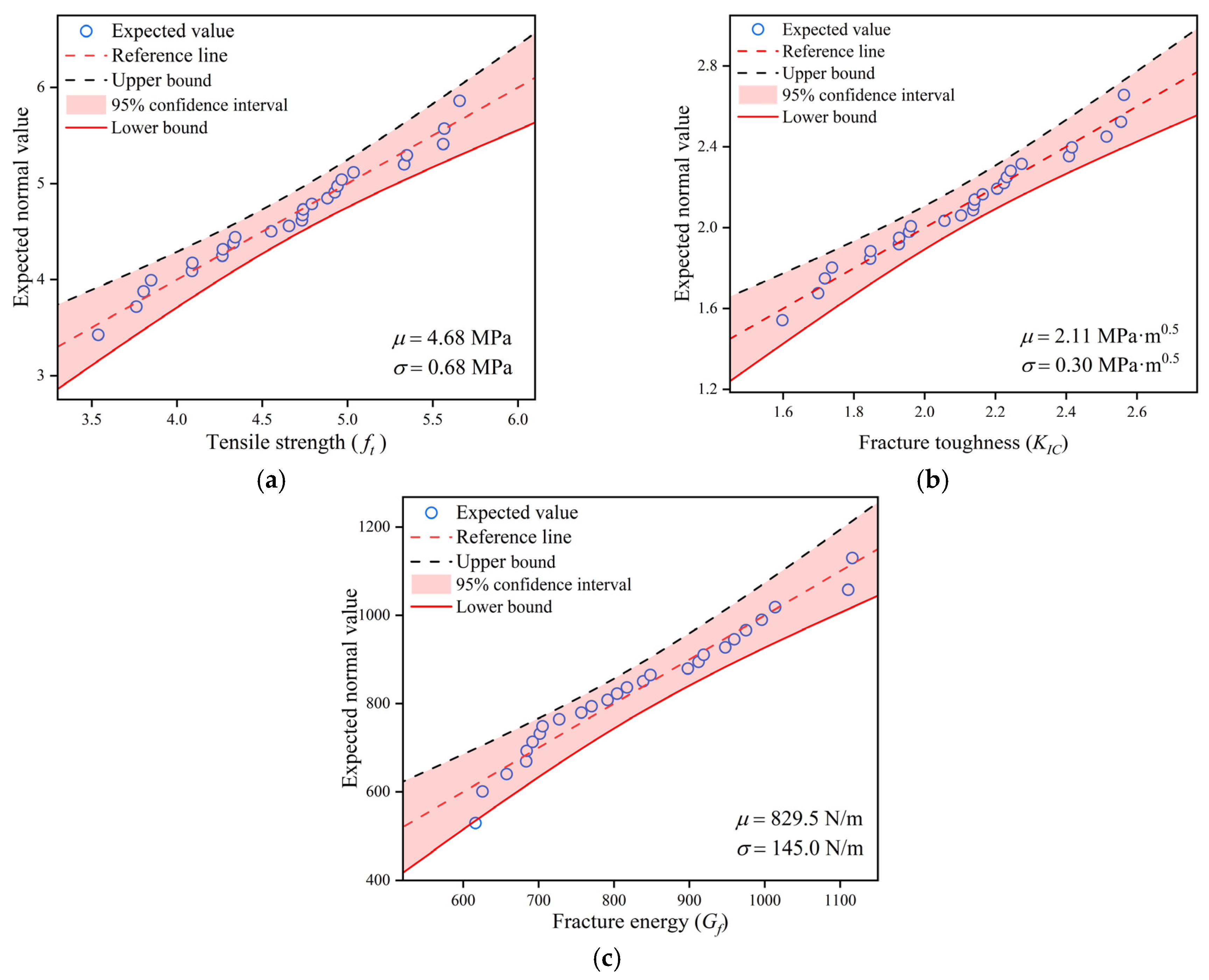

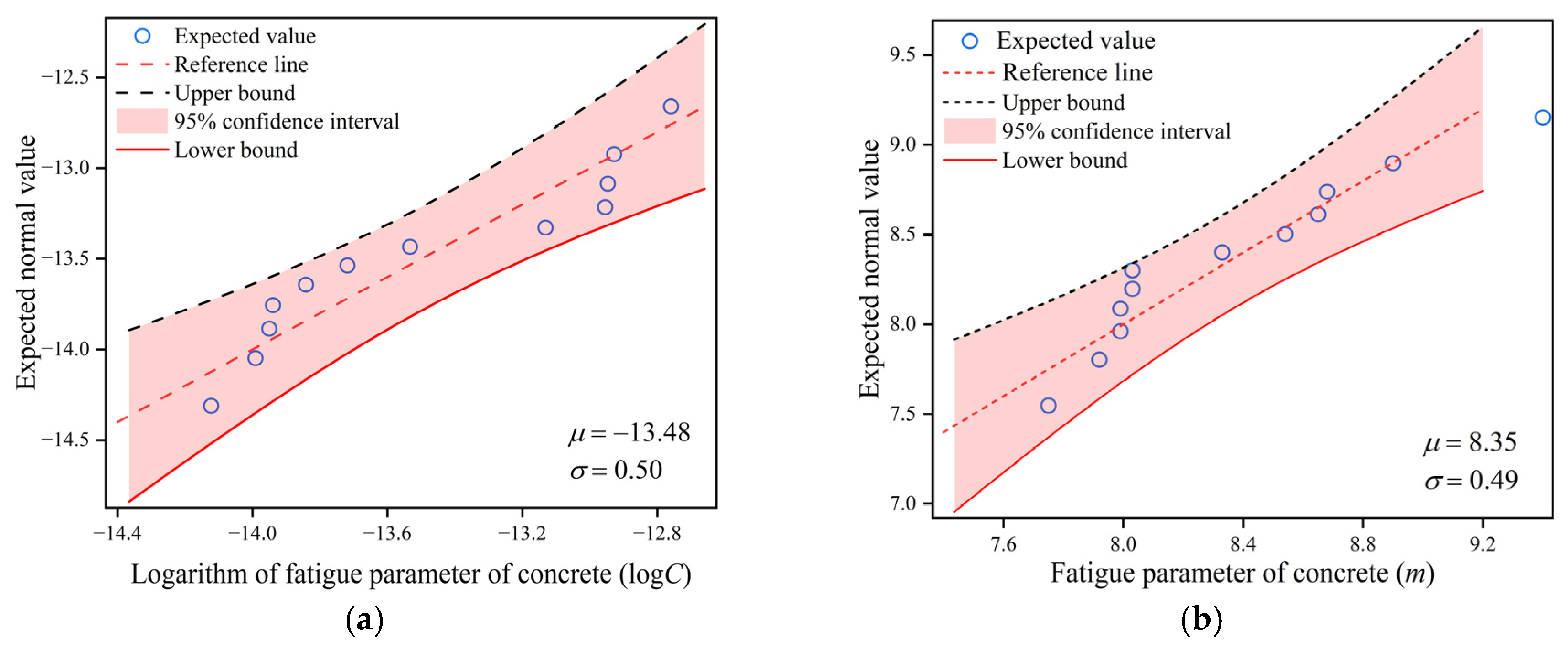

2.3. Statistical Characterization of Material Parameters

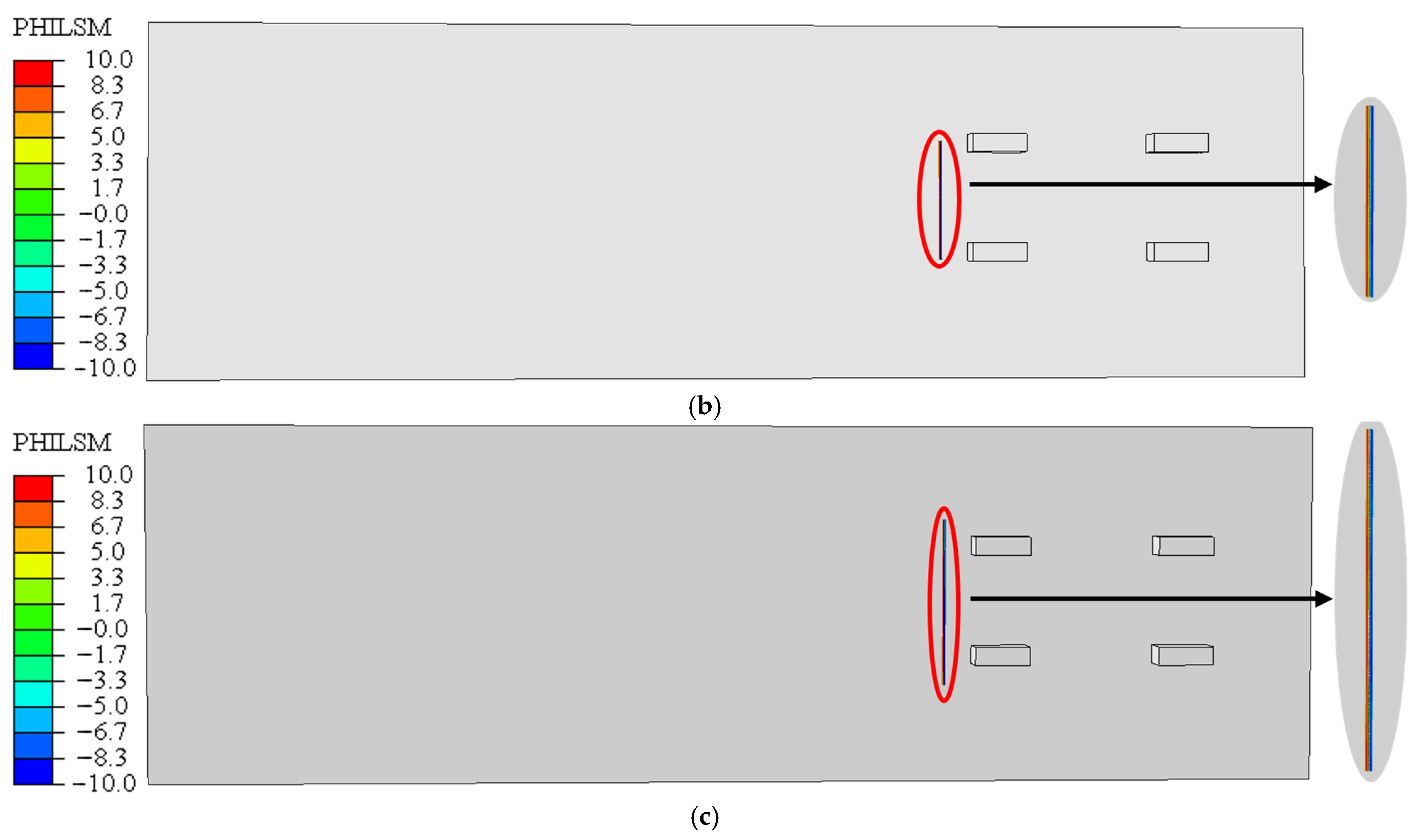

3. XFEM Simulation

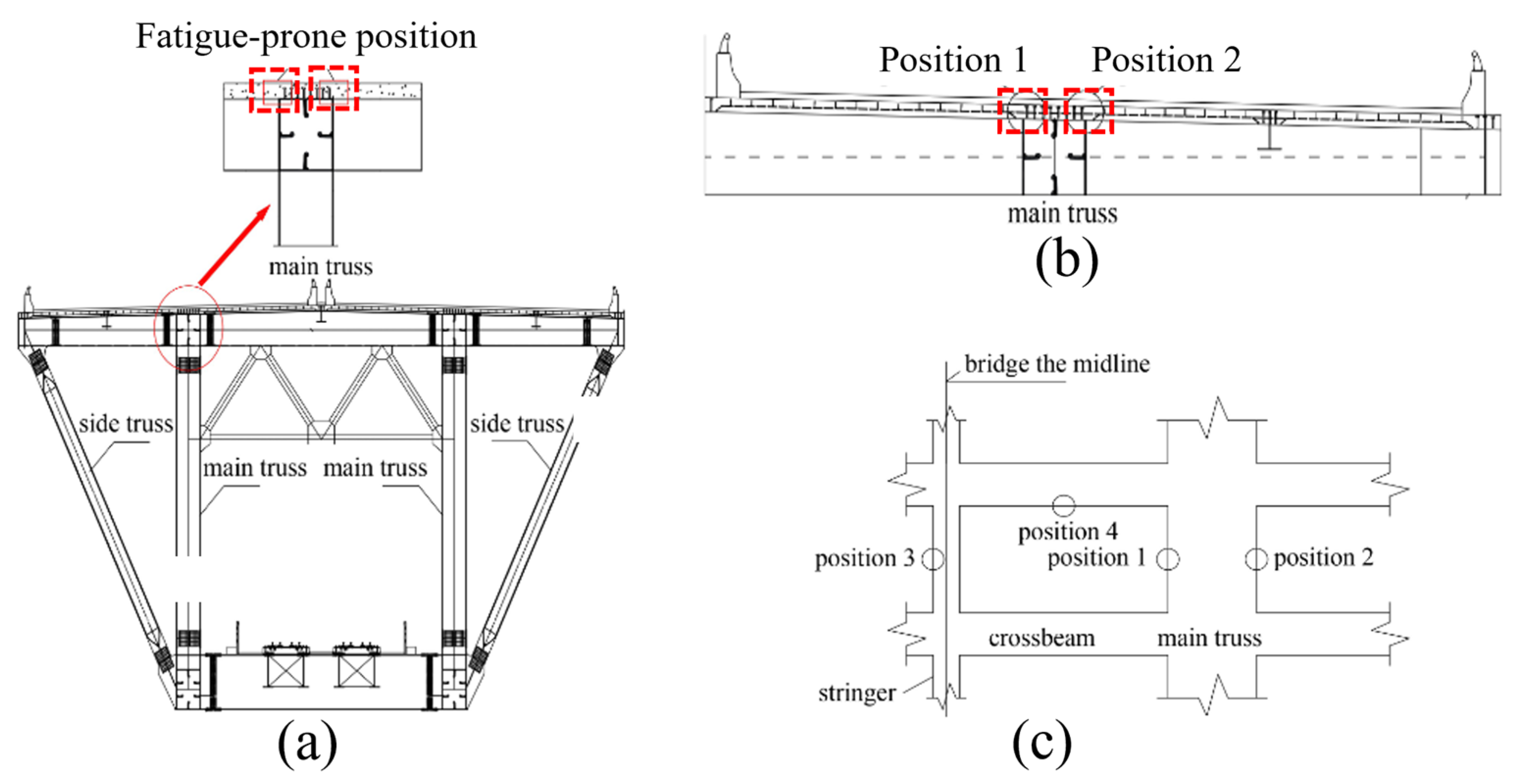

3.1. Prototype Bridge and Identification of Fatigue-Prone Regions

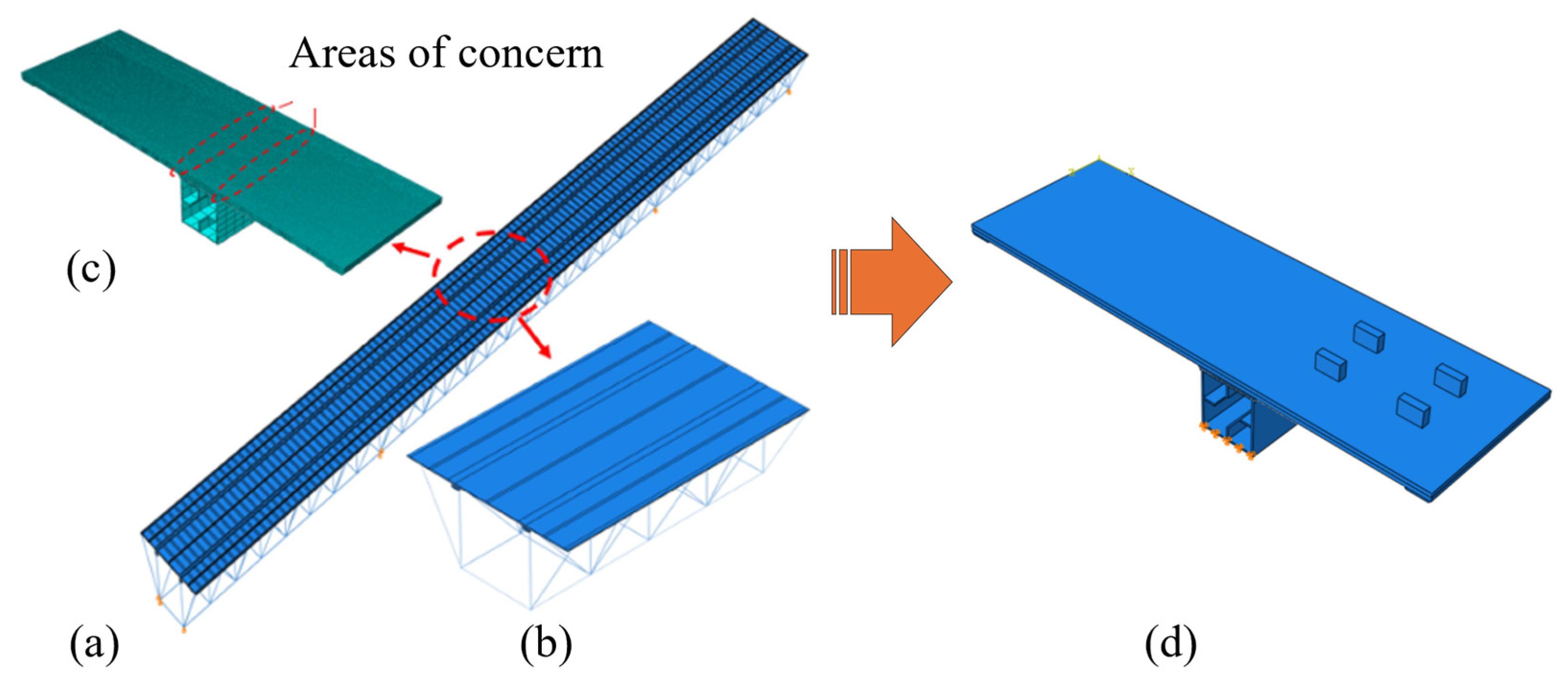

3.2. Finite Element Modeling of the Composite Bridge Deck

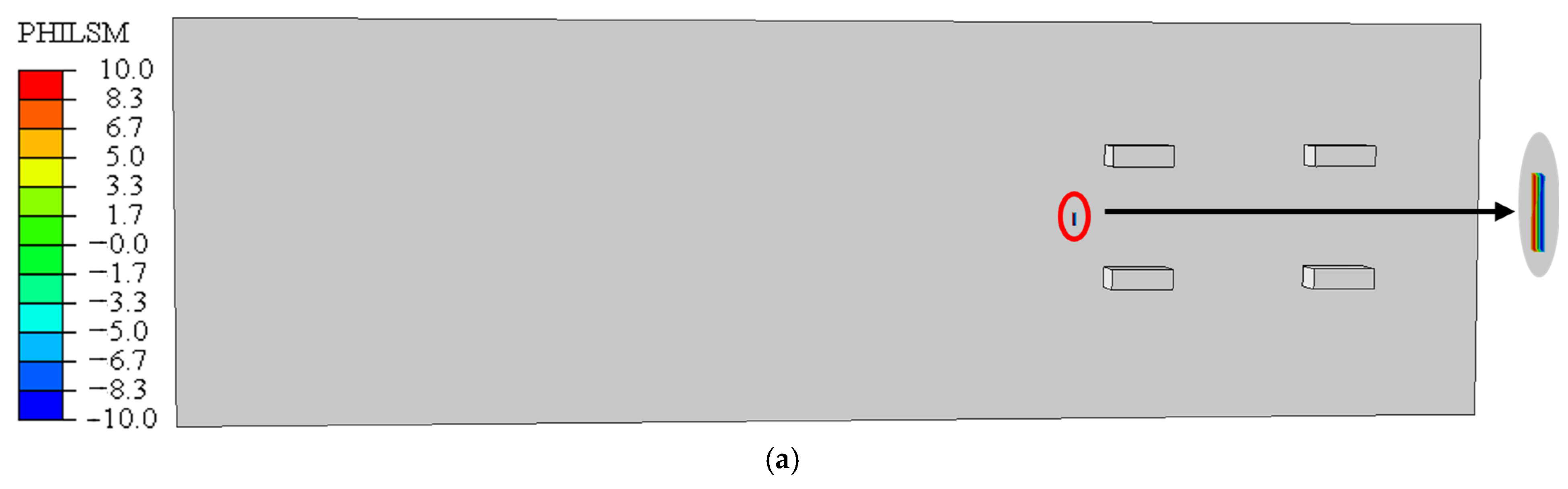

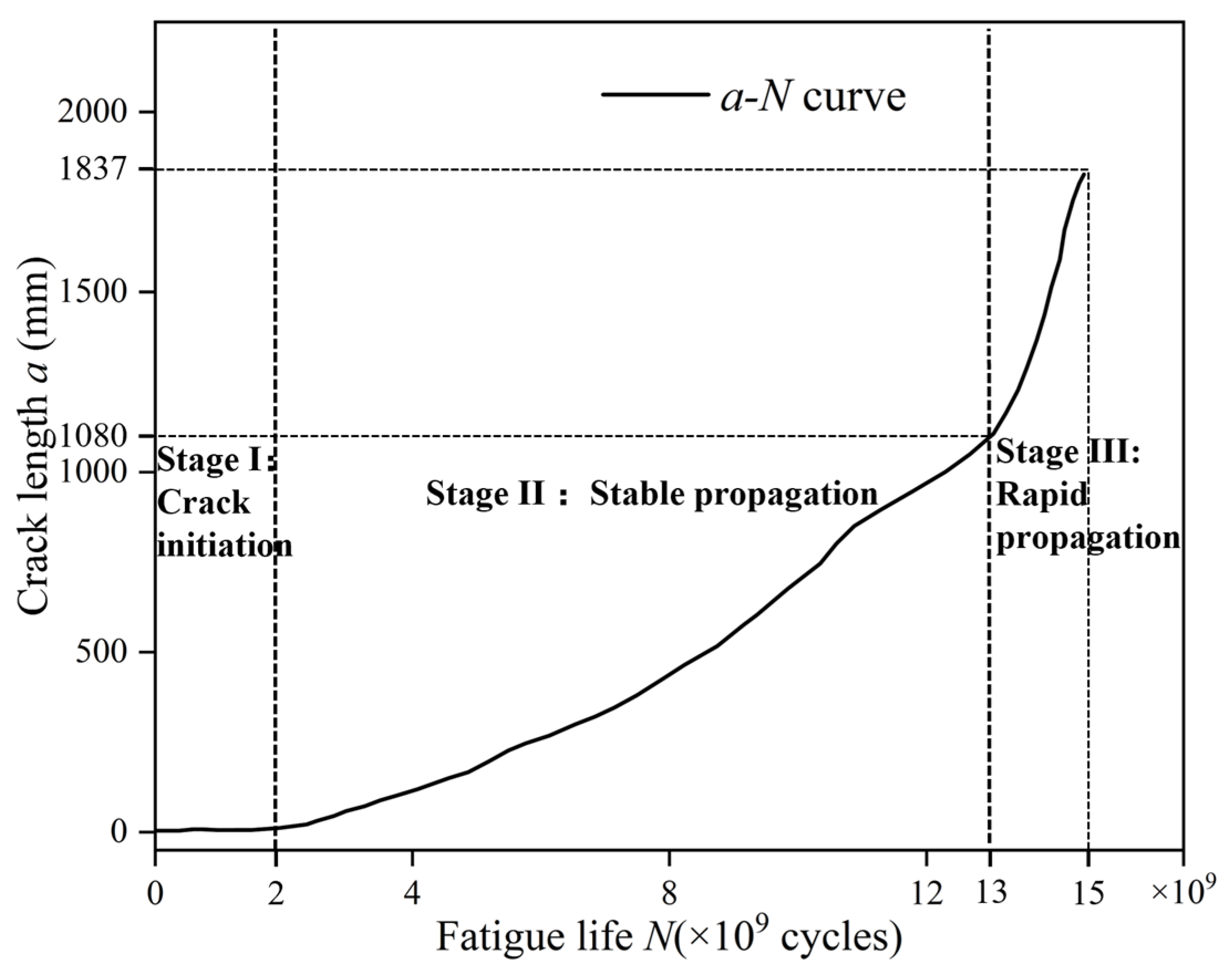

3.3. XFEM-Based Fatigue Crack Propagation and Material Parameters

4. Artificial Neural Network

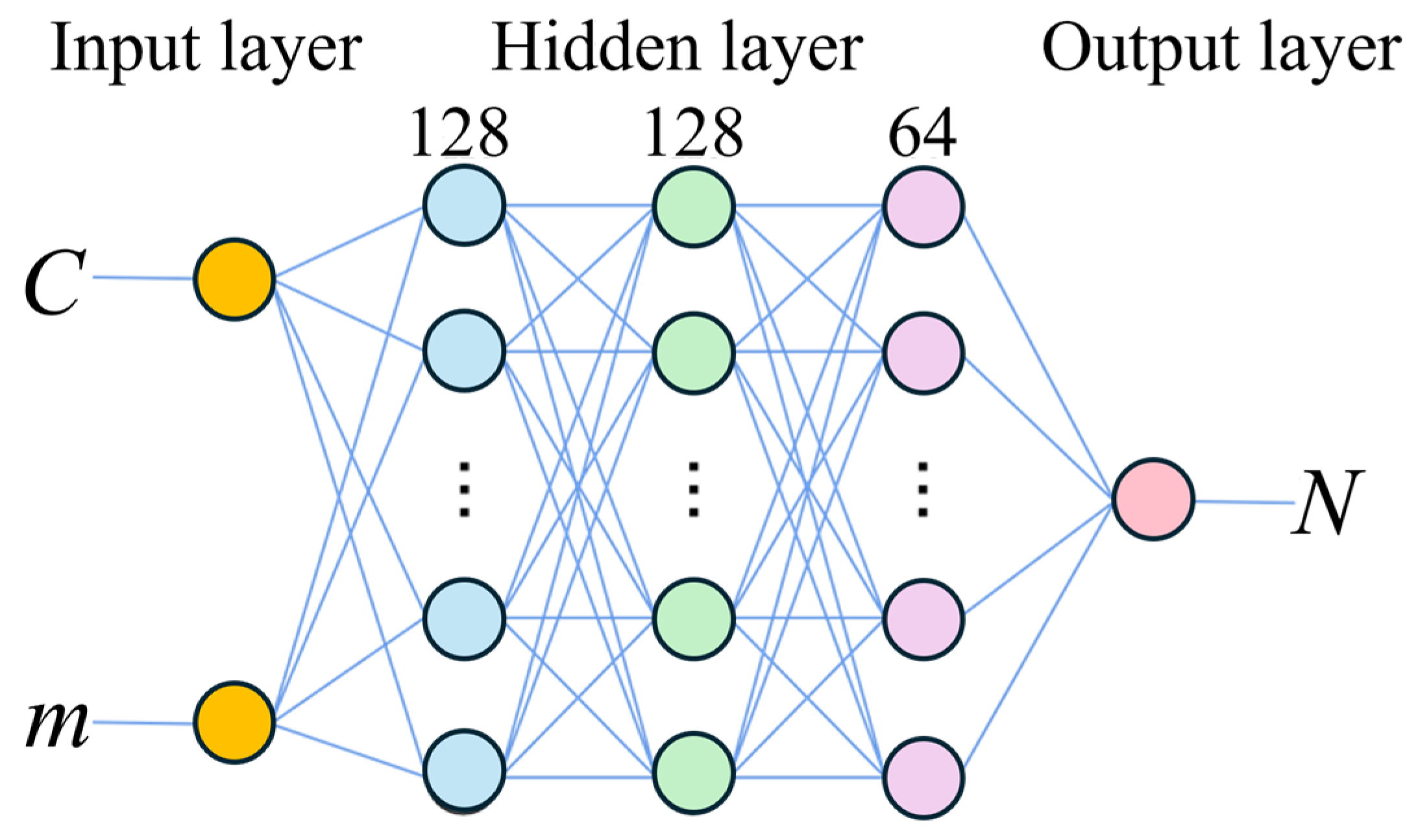

4.1. Structure of BP Neural Network

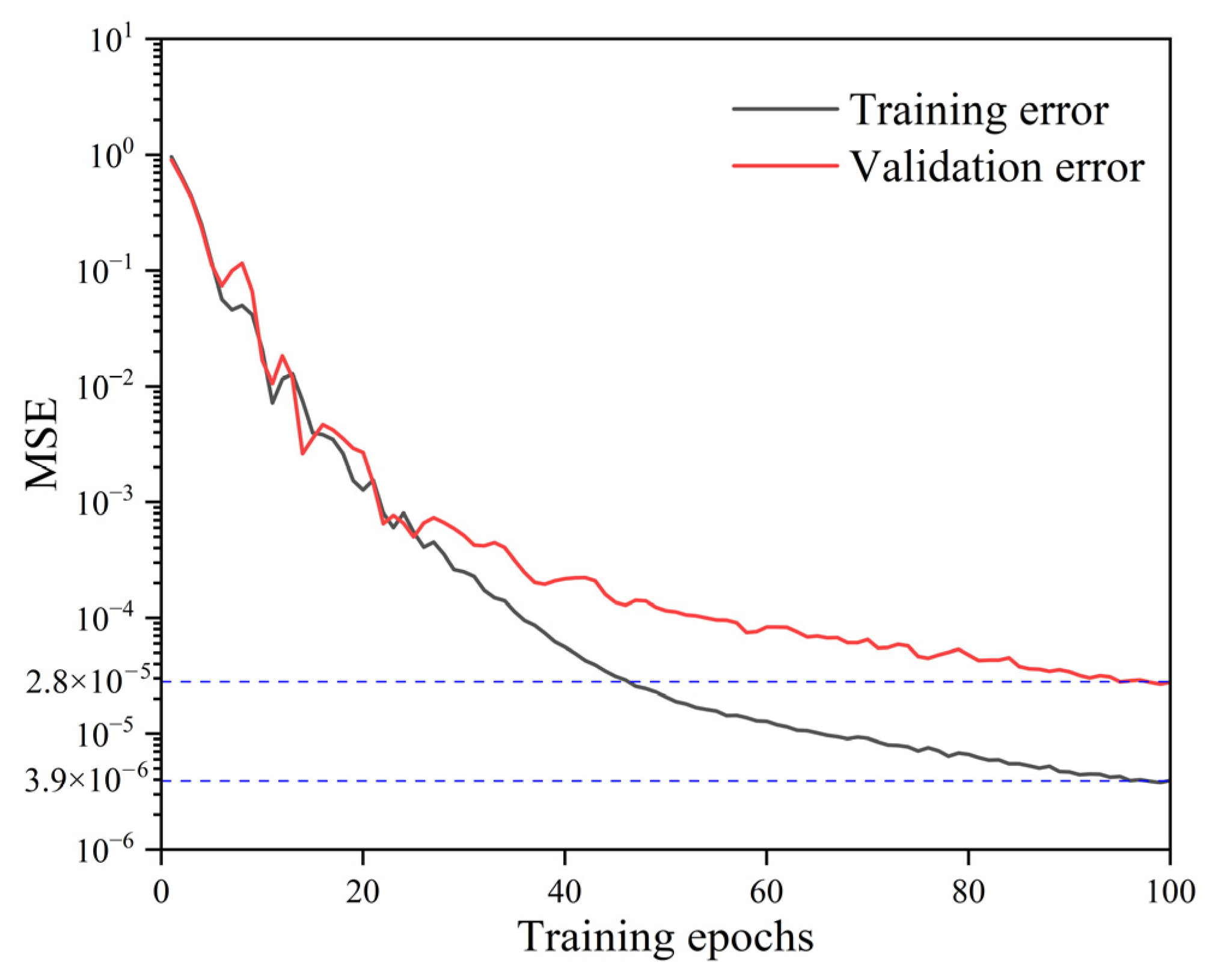

4.2. Data Collection and Preprocessing

4.3. Model Evaluation and Verification

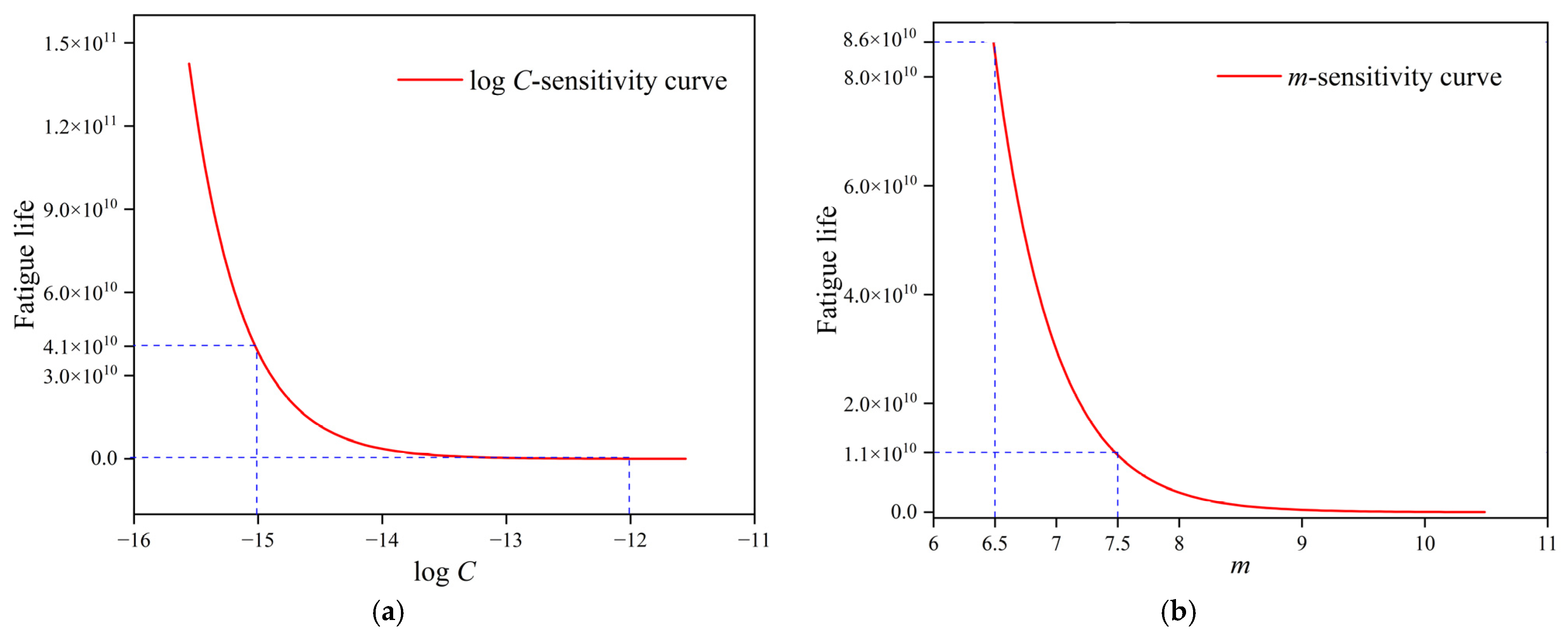

4.4. Sensitivity Analysis of Parameters

5. Fatigue Life Reliability Analysis

5.1. Monte Carlo-Based Reliability Evaluation

5.2. Conversion to Service Time and Computational Efficiency Comparison

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- Based on the statistical characteristics of the Paris law parameters C and m, 100 sets of random parameter combinations were generated from normal distributions using Python’s random sampling functions. The XFEM was employed to simulate crack initiation and propagation under cyclic loading, and the resulting fatigue life data served as the foundation for the subsequent ANN training and verification.

- (2)

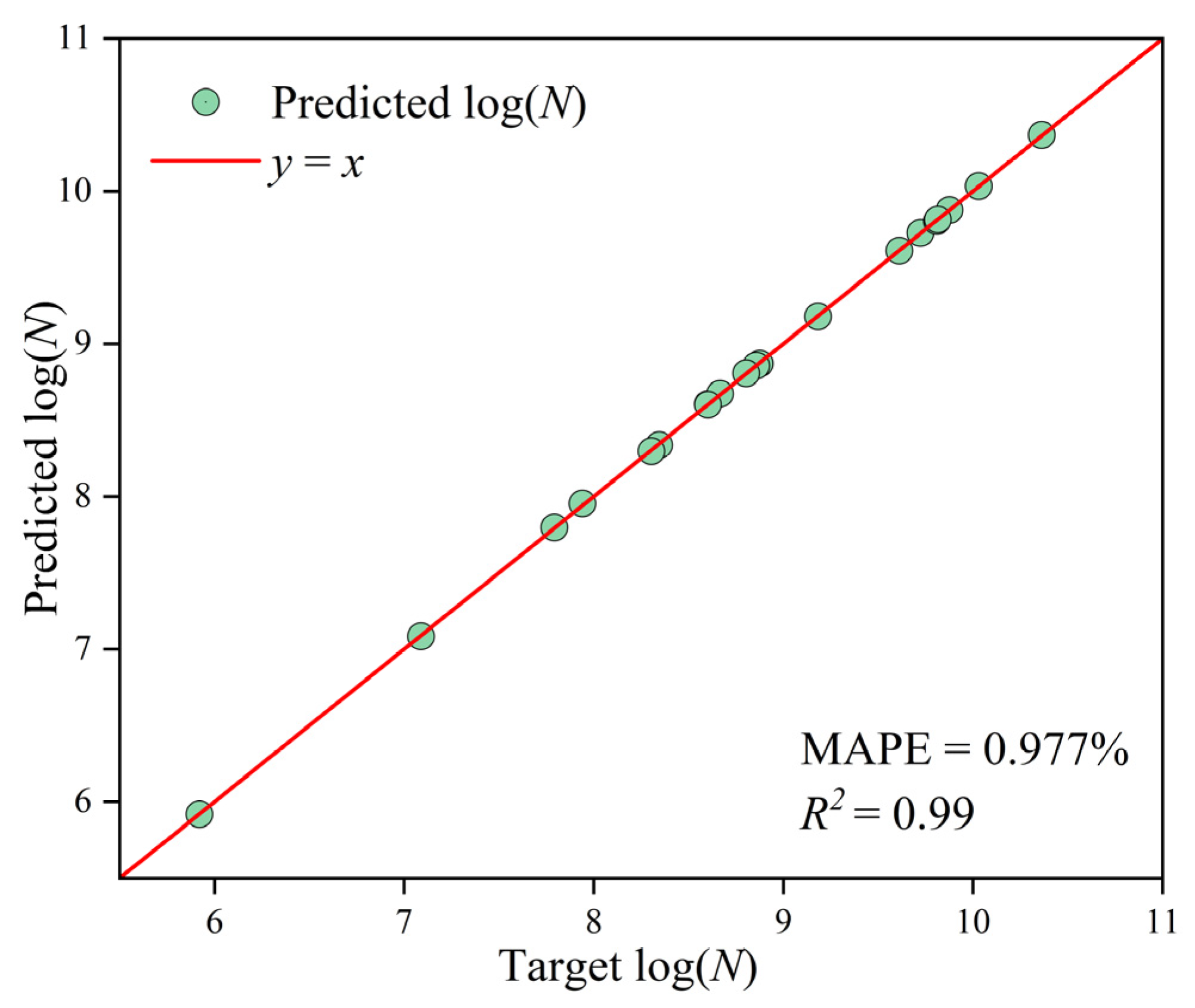

- A feedforward back-propagation neural network with three hidden layers (128–128–64) was constructed in Python using the ReLU activation function and Adam optimization algorithm. The model was trained by minimizing the Mean Squared Error (MSE) and evaluated through Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and Mean Absolute Percentage Error (MAPE). The optimized ANN achieved R2 = 0.99 and MAPE = 0.977%, demonstrating high prediction accuracy and good generalization for fatigue life estimation of the bridge deck.

- (3)

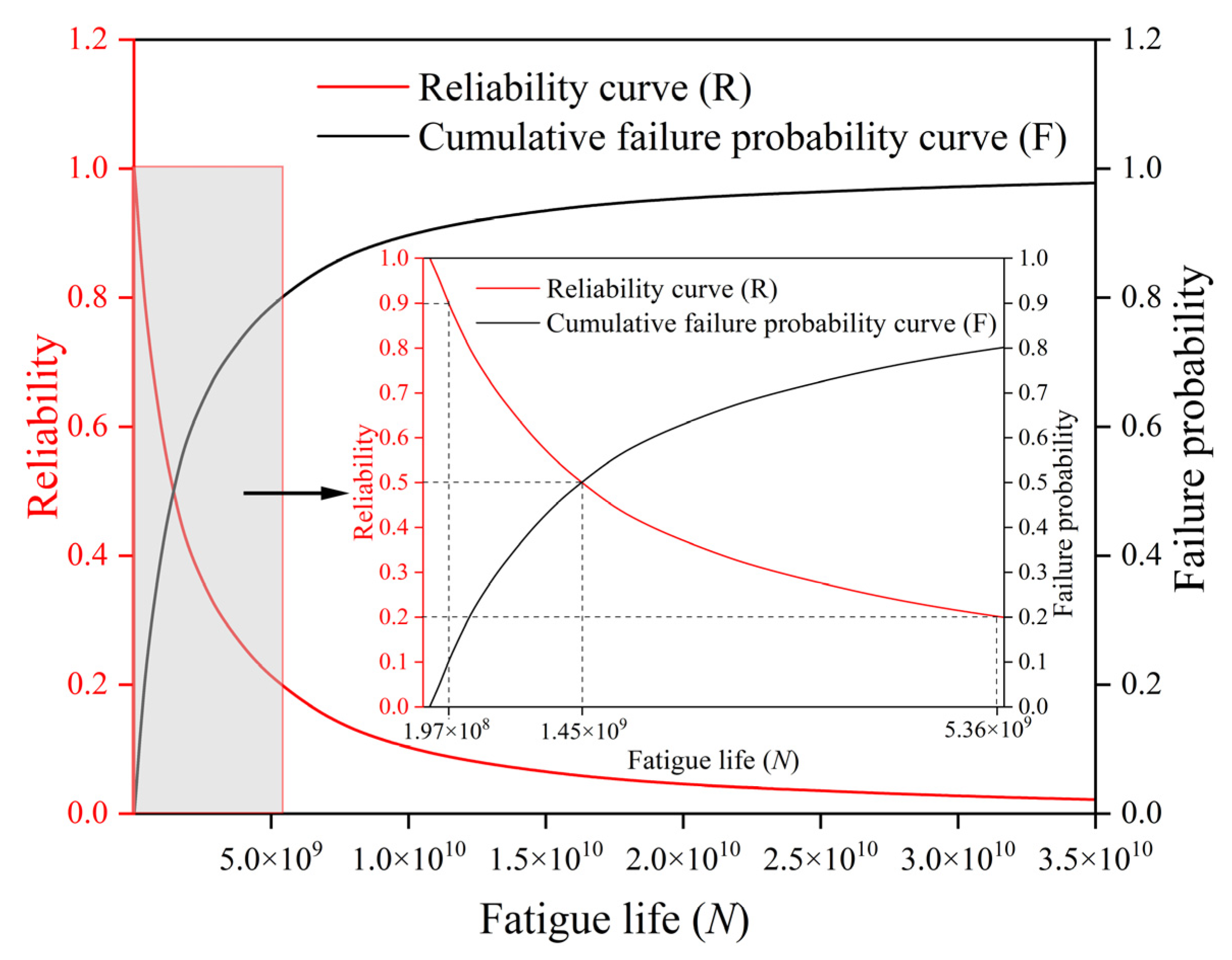

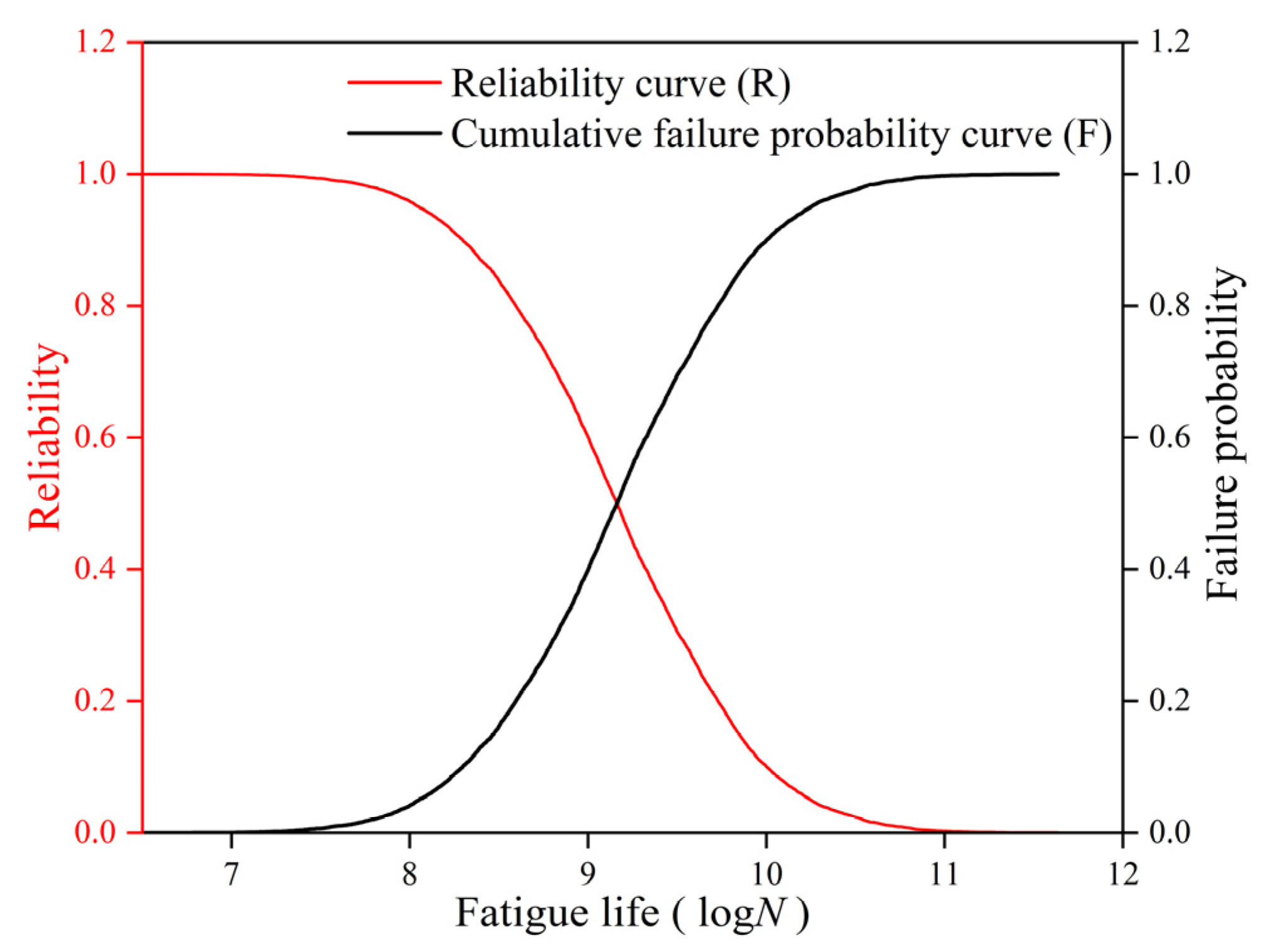

- The trained ANN model was coupled with the Monte Carlo simulation to perform 10,000 random samplings of parameters C and m, enabling rapid fatigue life prediction under multiple parameter combinations. The resulting reliability curves exhibited a nonlinear degradation pattern, in which the reliability remained high under low fatigue cycles but dropped sharply once a critical threshold of approximately 1.45 × 109 cycles was reached. Considering the actual bridge traffic volume of approximately 4593 vehicles per lane per day, the analysis indicated that the bridge deck maintained a reliability level of 0.99 after 23 years of service and decreased to 0.95 after 67 years, implying an increasing risk of fatigue cracking during long-term operation.

- (4)

- Compared with XFEM, which requires 6–8 h to complete a single fatigue simulation, the trained ANN model can predict 10,000 parameter combinations within seconds, improving computational efficiency by more than four orders of magnitude. This hybrid XFEM–ANN–Monte Carlo framework effectively bridges deterministic simulation and probabilistic modeling, offering a practical and efficient tool for large-scale reliability evaluation of concrete bridge decks.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fathalla, E.; Tanaka, Y.; Maekawa, K. Effect of crack orientation on fatigue life of reinforced concrete bridge decks. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.C.; Cao, J.Z.; Huang, Z.; Wang, S.Q.; Takahashi, Y.; Gong, F.Y. Fatigue life of RC bridge decks affected by speed and load weight of wheel-type moving loads. Structures 2024, 64, 106563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, P.N.; Matsumoto, T. Determination of dominant degradation mechanisms of RC bridge deck slabs under cyclic moving loads. Int. J. Fatigue 2018, 112, 328–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Zhao, C.J.; Liu, Y.Q. Mechanism of longitudinal cracking in concrete deck slabs of composite cable-stayed bridges. Eng. Struct. 2025, 327, 119544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blacha, Ł. Non-linear probabilistic modification of Miner’s rule for damage accumulation. Materials 2021, 14, 7335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batsoulas, N.D.; Giannopoulos, G.I. Cumulative fatigue damage of composite laminates: Engineering rule and life prediction aspect. Materials 2023, 16, 3271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baktheer, A.; Chudoba, R. Experimental and theoretical evidence for the load sequence effect in the compressive fatigue behavior of concrete. Mater. Struct. 2021, 54, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Li, N.C.; Tan, B.K.; Shi, J.L.; Zhang, Z. Multiaxial fatigue damage analysis of steel–concrete composite beam based on the Smith–Watson–Topper parameter. Buildings 2024, 14, 1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burhan, I.; Kim, H.S. S-N curve models for composite materials characterisation: An evaluative review. J. Compos. Sci. 2018, 2, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedmak, A. Fatigue crack growth simulation by extended finite element method: A review of case studies. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2024, 47, 1819–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moës, N.; Dolbow, J.; Belytschko, T. A finite element method for crack growth without remeshing. Int. J. Numer. Methods Eng. 1999, 46, 131–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, G.L.; Zhang, Z.X.; Huang, X.M. Fatigue cracking analysis of asphalt concrete based on coupled XFEM-Continuum Damage Mechanics method. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2021, 33, 04020425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontarz, J.; Podgórski, J. Prediction of crack path in concrete-like composite using extended finite element method. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2025, 19, 239–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swati, R.; Reddy, K.S.; Ramachandra, L.S. Stress intensity factor based damage prediction model for plain concrete under cyclic loading. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2018, 30, 04018118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.D.; Wu, Z.M.; Jiang, X.Y.; Yu, R.C.; Zhang, X.X.; Wang, Y.J. Modified Paris law for mode I fatigue fracture of concrete based on crack propagation resistance. Theor. Appl. Fract. Mech. 2024, 131, 104383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.K.; Kim, Y.Y. Fatigue crack growth of high-strength concrete in wedge-splitting test. Cem. Concr. Res. 1999, 29, 705–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Chen, X.D.; Guo, S.S. Experimental study on acoustic emission characteristic of fatigue crack growth of self-compacting concrete. Struct. Control Health Monit. 2019, 26, e2332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miarka, P.; Seitl, S.; Bílek, V.; Cifuentes, H. Assessment of fatigue resistance of concrete: S-N curves to the Paris’ law curves. Constr. Build. Mater. 2022, 341, 127811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Li, Y.F. Dynamic reliability assessment of multi-cracked structure under fatigue loading via multi-state physics model. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2021, 213, 107664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llanos, D.; Huerta, A.; Huisa, J.; Ariza, V. Probabilistic evaluation of flexural demand in RC beams through Monte Carlo simulation. Constr. Mater. 2025, 5, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix, E.F.; Falcão, I.d.S.; dos Santos, L.G.; Carrazedo, R.; Possan, E. A Monte Carlo-based approach to assess the reinforcement depassivation probability of RC structures: Simulation and analysis. Buildings 2023, 13, 993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.N.; Zhang, W.X.; Zhao, Y.R. ANN prediction model of concrete fatigue life based on GRW-DBA data augmentation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lunardi, L.R.; Cornélio, P.G.; Prado, L.P.; Nogueira, C.G.; Felix, E.F. Hybrid machine learning model for predicting the fatigue life of plain concrete under cyclic compression. Buildings 2025, 15, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.H.; Ding, K.Q.; Huang, B.Q. Approach for fault prognosis using recurrent neural network. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 1621–1633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z.P. Size effect in blunt fracture: Concrete, rock, metal. J. Eng. Mech. 1984, 110, 518–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.Z.; Duan, K. Size effect and quasi-brittle fracture: The role of FPZ. Int. J. Fract. 2008, 154, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillerborg, A.; Modéer, M.; Petersson, P.E. Analysis of crack formation and crack growth in concrete by means of fracture mechanics and finite elements. Cem. Concr. Res. 1976, 6, 773–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillerborg, A. Application of the fictitious crack model to different types of materials. Int. J. Fract. 1991, 51, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z.P.; Schell, W.F. Fatigue fracture of high-strength concrete and size effect. ACI Mater. 1993, 90, 472–478. [Google Scholar]

- Saouma, V.E.; Barton, C.C. Fractals, fractures, and size effects in concrete. J. Eng. Mech. 1994, 120, 835–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bažant, Z.P.; Planas, J. Fracture and Size Effect in Concrete and Other Quasibrittle Materials, 1st ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo, Y.F. Research on the Fatigue Crack Growth Life of Bridge Deck Concrete Based on Statistical Probability. Master’s Thesis, Beijing University of Technology, Beijing, China, 2025. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Kirane, K.; Bažant, Z.P. Size effect in Paris law and fatigue lifetimes for quasibrittle materials: Modified theory, experiments and micro-modeling. Int. J. Fract. 2016, 83, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.W. Fatigue Cracking Study of Composite Bridge Deck in Railway–Highway Bridge. Master’s Thesis, Beijing University of Technology, Beijing, China, 2023. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Transport of the People’s Republic of China. JTG D64-2015: Design Code for Highway Steel Bridges; China Communications Press: Beijing, China, 2015. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Mansour, M.Y.; Dicleli, M.; Lee, J.Y.; Zhang, J. Predicting the shear strength of reinforced concrete beams using artificial neural networks. Eng. Struct. 2004, 26, 781–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, M.; Zhou, C.; Pei, X.; Xu, Z.; Xu, W.; Wan, Z. Fatigue life prediction of CFRP-FBG sensor-reinforced RC beams enabled by LSTM-based deep learning. Polymers 2025, 17, 2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.Y. Study on Fatigue Damage Model of Composite Steel Truss Bridge Deck. Master’s Thesis, Beijing University of Technology, Beijing, China, 2024. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.T.; Zhan, X.W.; Zhu, X.F.; Zhang, W.X. Fatigue evaluation of steel-concrete composite deck in steel truss bridge—A case study. Front. Struct. Civ. Eng. 2022, 16, 1336–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | C | m | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | 1.11 × 10−13 | 7.92 | 155 | –0.046 | 1.73549 × 10−7 | 3.96 |

| No. | C | m | Fatigue Life N | Reliability R |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 3.04172 × 10−12 | 8.837 | 5.93 × 106 | 0.9999 |

| 2 | 1.14668 × 10−12 | 9.281 | 6.09 × 106 | 0.9998 |

| 3 | 9.72082 × 10−13 | 9.122 | 9.89 × 106 | 0.9997 |

| … | … | … | … | … |

| 9998 | 3.56685 × 10−15 | 6.882 | 2.81 × 1011 | 0.0003 |

| 9999 | 3.62076 × 10−16 | 7.775 | 4.32 × 1011 | 0.0002 |

| 10,000 | 2.17557 × 10−15 | 6.892 | 4.35 × 1011 | 0.0001 |

| Reliability (R) | Fatigue Life (Cycles) | Service Time (Years) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.99 | 3.82 × 107 | 23 |

| 0.95 | 1.13 × 108 | 67 |

| 0.90 | 1.97 × 108 | 118 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chen, H.; Li, P.; Zhuo, Y. Fatigue Life Prediction and Reliability Analysis of Reinforced Concrete Bridge Decks Based on an XFEM–ANN–Monte Carlo Hybrid Framework. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010209

Chen H, Li P, Zhuo Y. Fatigue Life Prediction and Reliability Analysis of Reinforced Concrete Bridge Decks Based on an XFEM–ANN–Monte Carlo Hybrid Framework. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):209. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010209

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Huating, Peng Li, and Yifan Zhuo. 2026. "Fatigue Life Prediction and Reliability Analysis of Reinforced Concrete Bridge Decks Based on an XFEM–ANN–Monte Carlo Hybrid Framework" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010209

APA StyleChen, H., Li, P., & Zhuo, Y. (2026). Fatigue Life Prediction and Reliability Analysis of Reinforced Concrete Bridge Decks Based on an XFEM–ANN–Monte Carlo Hybrid Framework. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 209. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010209