Hybrid AI Systems for Tool Wear Monitoring in Manufacturing: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

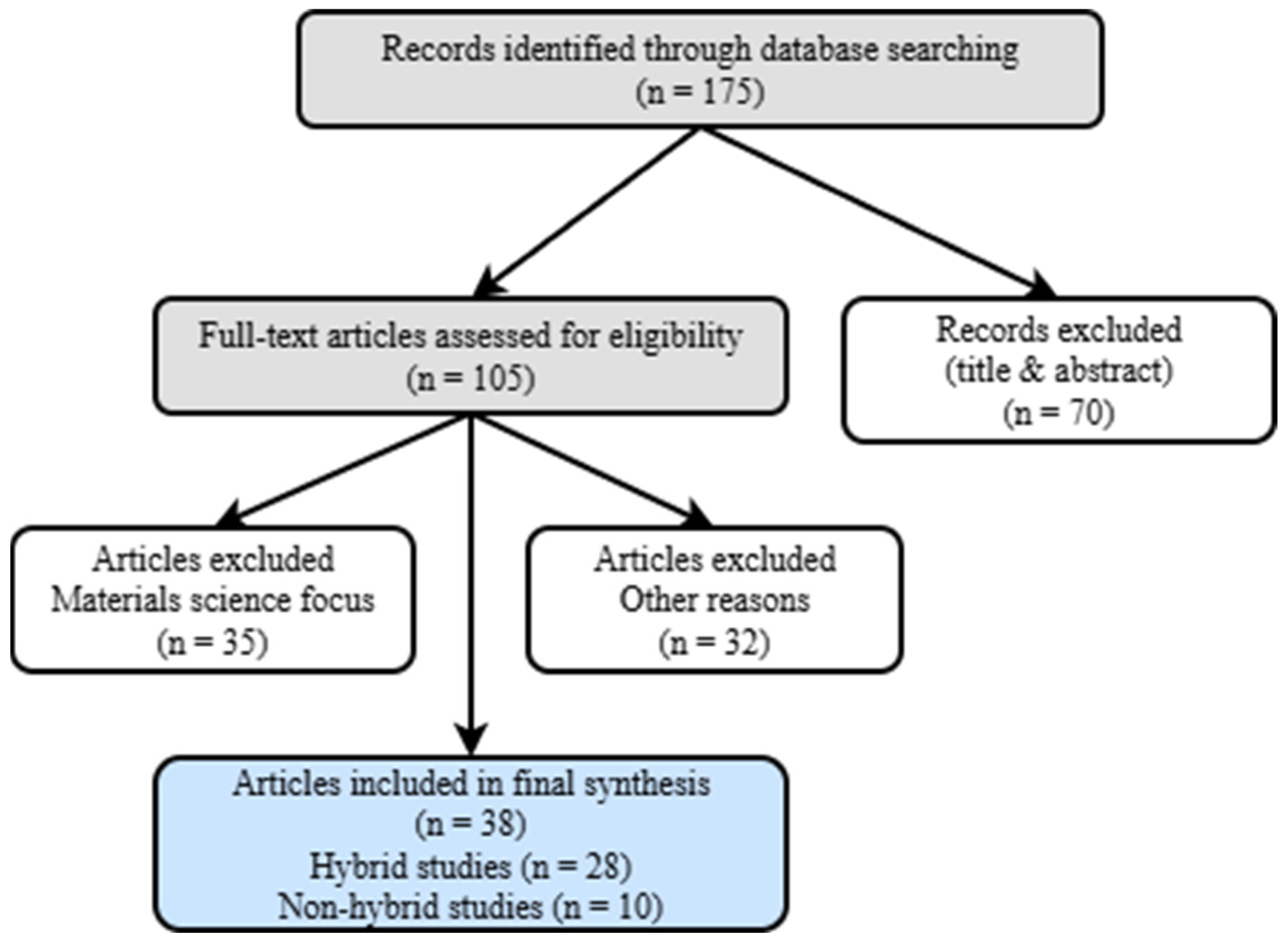

Methodology of the Review

- (i)

- What is the scope of the study?

- (ii)

- What methods were used?

- (iii)

- What data types and datasets were used?

- (iv)

- What are the key performance results?

- (v)

- What are the contributions and limitations of the study?

- Studies using classical machine learning (ML) algorithms,

- Studies using deep learning (DL) algorithms,

- Hybrid studies,

- Current challenges and future research trends.

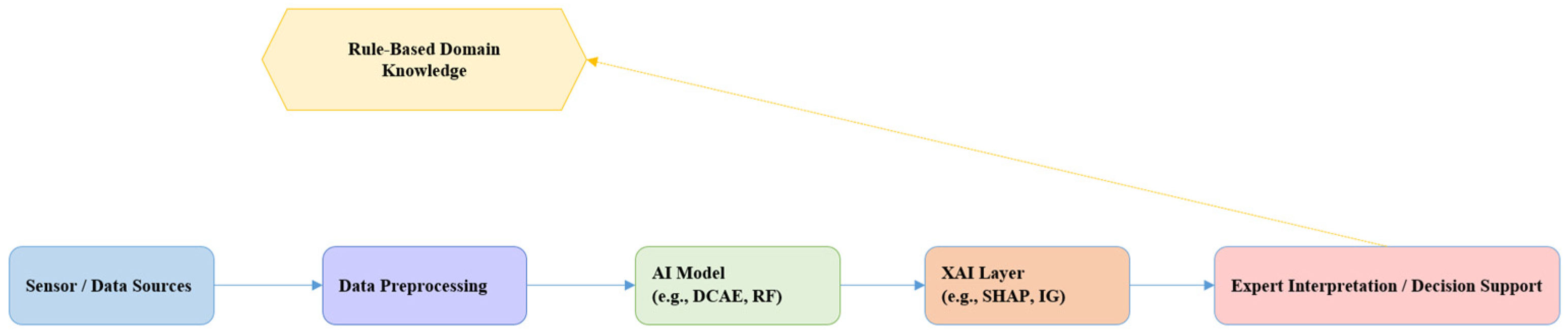

2. Defining Hybrid Approaches: Integration Principles and Applications

2.1. Physics-Informed Hybrid Applications

2.2. Knowledge-Guided Hybrid Applications

- Local explanations, which explain the decision in a single example;

- Global explanations, which explain the overall structure of the model (visual/mathematical);

- Contrastive explanations, which explain why a particular output was chosen;

- What-if explanations, which explain the effect of input changes on the outcome;

- Counterfactual explanations, which explain how changing assumptions can affect the outcome;

- Example-based explanations that explain model behavior with concrete data examples.

2.3. Transfer Learning Hybrid Applications

2.4. Heterogeneous Model Hybrid Applications

3. The Limitations of Non-Hybrid Approaches

4. Challenges and Future Directions

4.1. Major Challenges

4.2. Future Research Directions

- 1.

- Prioritize “Generalization by Design”: Future hybrid systems must be built with adaptability as a core principle. This involves:

- -

- Invariant Feature Learning for Sensor Variability: As highlighted by the industrial deployment case study in [79], transfer learning can fail asymmetrically (e.g., successful transfer from Factory B to A, but failure from A to B) due to variations in sensor placement (e.g., tool holder vs. cutting tool). Future hybrid models must incorporate invariant feature learning techniques that decouple the monitoring signal from the specific hardware configuration. Research should focus on learning “sensor-agnostic” representations that remain robust even when signal amplitude or noise profiles change due to physical sensor relocation.

- -

- -

- Meta-Learning and Automated Configuration: Creating systems that can automatically reconfigure their hybrid architecture (e.g., the weight of a physics-based loss function) based on the target task, moving beyond the static designs prevalent today.

- 2.

- Bridge the Real-Time Explainability Gap: Accuracy alone is insufficient for shop-floor acceptance. We believe the next frontier is the co-design of efficiency and interpretability.

- -

- Develop Lightweight, Intrinsically Interpretable Hybrids: Following the precedent of lightweight models like PIDGGCN [58], future work should focus on architectures that are both computationally efficient and transparent by design, perhaps through simplified model structures or rule-based components.

- -

- 3.

- Embrace Causal and Generative Frameworks: The field must evolve from predictive diagnostics to prescriptive and generative solutions.

- -

- Integrate Causal Discovery: Moving beyond correlations to identify root causes of faults or wear will make hybrid systems more robust and actionable.

- -

- Develop Hybrid Digital Twins: Combining physics-based models, real-time data, and AI into dynamic digital twins can create a powerful platform for simulation, optimization, and proactive decision-making, ultimately leading to autonomous self-optimizing manufacturing systems.

- 4.

- Develop Cost-Aware and Noise-Resilient Hybrid Architectures: The transition from lab to factory is often stalled by the cost of high-precision sensors. The case study of the Physics-Informed State Space Model (PSSM) [60] demonstrated that while multi-sensor fusion (force, vibration, AE) yields high accuracy, the installation complexity and cost of dynamometers are prohibitive for widespread use. Conversely, the knowledge-guided study in [69] revealed that low-cost alternatives like motor current sensors suffer from low signal-to-noise ratios, particularly at low feed rates.

- 5.

- Asynchronous Multi-Modal Fusion Strategies: Hybrid systems that combine visual inspection with sensor data offer superior performance but face synchronization challenges. The heterogeneous model case study in [87] showed that while integrating image analysis (YOLOv3) with force/vibration signals eliminated critical classification errors, it highlighted a temporal disconnect: sensor data is continuous and real-time, while optical inspection is often discrete or offline.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yang, T.; Yi, X.; Lu, S.; Johansson, K.H.; Chai, T. Intelligent Manufacturing for the Process Industry Driven by Industrial Artificial Intelligence. Engineering 2021, 7, 1224–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baru, C.; Daimler, E.; Ferguson, R.; Forbe, N.; Harder, E.; Ferguson, R. The National Artificial Intelligence Research and Development Strategic Plan; U.S. NSTC: Washington, DC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Executive Office of the President. Fiscal Year 2020 Administration Research and Development Budget Priorities: Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies; White House Office of Management and Budget: Washington, DC, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Executive Office of the President. Fiscal Year 2021 Administration Research and Development Budget Priorities: Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies; Executive Office of the President: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The Research Group for Research on Intelligent Manufacturing Development Strategy. Research on Intelligent Manufacturing Development Strategy in China. Strateg. Stud. Chin. Acad. Eng. 2018, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Li, P.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, B.; Zang, J.; Meng, L. Toward New-Generation Intelligent Manufacturing. Engineering 2018, 4, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, L.M.; Teti, R.; Alvir, E.M.R. Quality, Efficiency and Sustainability Improvement in Machining Processes Using Artificial Intelligence. Procedia CIRP 2023, 118, 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.-Q.; Doan, H.-P.; Vu, V.Q.; Vu, L.T. Machine Learning and IoT-Based Approach for Tool Condition Monitoring: A Review and Future Prospects. Measurement 2023, 207, 112351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, R.X.; Krüger, J.; Merklein, M.; Möhring, H.-C.; Váncza, J. Artificial Intelligence in Manufacturing: State of the Art, Perspectives, and Future Directions. CIRP Ann. 2024, 73, 723–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, A.; Gutknecht, R.; Warnke, P.; Goetheer, A.; Schirrmeister, E.; Bakker, B.; Meissner, S. New Perspectives for Data-supported Foresight: The Hybrid AI-expert Approach. Futures Foresight Sci. 2022, 4, e99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peres, R.S.; Jia, X.; Lee, J.; Sun, K.; Colombo, A.W.; Barata, J. Industrial Artificial Intelligence in Industry 4.0—Systematic Review, Challenges and Outlook. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 220121–220139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ordenshiya, K.M.; Revathi, G.K. Hybrid FCMG-OP-FIS Model Approach to Convert Regression into Classification Data for Machine Learning-Based AQI Prediction. Heliyon 2024, 10, e39759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasilingam, S.; Yang, R.; Singh, S.K.; Farahani, M.A.; Rai, R.; Wuest, T. Physics-Based and Data-Driven Hybrid Modeling in Manufacturing: A Review. Prod. Manuf. Res. 2024, 12, 2305358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijay Kumar, V.; Shahin, K. Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning for Sustainable Manufacturing: Current Trends and Future Prospects. Intell. Sustain. Manuf. 2025, 2, 10002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macit, C.K.; Saatci, B.T.; Albayrak, M.G.; Ulas, M.; Gurgenc, T.; Ozel, C. Prediction of Wear Amounts of AZ91 Magnesium Alloy Matrix Composites Reinforced with ZnO-HBN Nanocomposite Particles by Hybridized GA-SVR Model. J. Mater. Sci. 2024, 59, 17456–17490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalidindi, S.R. Feature Engineering of Material Structure for AI-Based Materials Knowledge Systems. J. Appl. Phys. 2020, 128, 041103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M. Unleashing the Power of Artificial Intelligence in Phonon Thermal Transport: Current Challenges and Prospects. J. Appl. Phys. 2024, 135, 170904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ejjami, R.; Boussalham, K. Industry 5.0 in Manufacturing: Enhancing Resilience and Responsibility through AI-Driven Predictive Maintenance, Quality Control, and Supply Chain Optimization. Int. J. Multidiscip. Res. 2024, 6, 25733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Liu, Z.; Wang, B.; Song, Q.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L. Leveraging Artificial Intelligence for Real-Time Indirect Tool Condition Monitoring: From Theoretical and Technological Progress to Industrial Applications. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2024, 202, 104209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangwala, S.; Dornfeld, D. Sensor Integration Using Neural Networks for Intelligent Tool Condition Monitoring. J. Eng. Ind. 1990, 112, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntoğlu, M.; Aslan, A.; Pimenov, D.Y.; Usca, Ü.A.; Salur, E.; Gupta, M.K.; Mikolajczyk, T.; Giasin, K.; Kapłonek, W.; Sharma, S. A Review of Indirect Tool Condition Monitoring Systems and Decision-Making Methods in Turning: Critical Analysis and Trends. Sensors 2020, 21, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimla, D.E. Sensor Signals for Tool-Wear Monitoring in Metal Cutting Operations—A Review of Methods. Int. J. Mach. Tools Manuf. 2000, 40, 1073–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagani, L.; Parenti, P.; Cataldo, S.; Scott, J.; Annoni, M. Indirect Cutting Tool Wear Classification Using Deep Learning and Chip Colour Analysis. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 111, 1099–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yavuz, M.; Gökçe, H.; Şeker, U. Matkap Geometrisinin Takım Aşınması ve Talaş Oluşumu Üzerine Etkisinin Araştırılması. Gazi Mühendislik Bilim. Derg. 2017, 3, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Mir, A.; Luo, X.; Cheng, K.; Cox, A. Investigation of Influence of Tool Rake Angle in Single Point Diamond Turning of Silicon. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2018, 94, 2343–2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddhpura, A.; Paurobally, R. A Review of Flank Wear Prediction Methods for Tool Condition Monitoring in a Turning Process. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 65, 371–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saez-de-Buruaga, M.; Soler, D.; Aristimuño, P.X.; Esnaola, J.A.; Arrazola, P.J. Determining Tool/Chip Temperatures from Thermography Measurements in Metal Cutting. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 145, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marani, M.; Zeinali, M.; Songmene, V.; Mechefske, C.K. Tool Wear Prediction in High-Speed Turning of a Steel Alloy Using Long Short-Term Memory Modelling. Measurement 2021, 177, 109329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Ordás, M.T.; Alegre, E.; González-Castro, V.; Alaiz-Rodríguez, R. A Computer Vision Approach to Analyze and Classify Tool Wear Level in Milling Processes Using Shape Descriptors and Machine Learning Techniques. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2017, 90, 1947–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.-H.; Luo, Z.-R. Study of Using Cutting Chip Color to the Tool Wear Prediction. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2020, 109, 823–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SK, T.; Shankar, S.; T, M.; K, D. Tool Wear Prediction in Hard Turning of EN8 Steel Using Cutting Force and Surface Roughness with Artificial Neural Network. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2019, 234, 329–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgurovsky, M.Z.; Sineglazov, V.M.; Olena, I.C. Artificial Intelligence Systems Based on Hybrid Neural Networks; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; Volume 390. [Google Scholar]

- Akata, Z.; Balliet, D.; de Rijke, M.; Dignum, F.; Dignum, V.; Eiben, G.; Fokkens, A.; Grossi, D.; Hindriks, K.; Hoos, H.; et al. A Research Agenda for Hybrid Intelligence: Augmenting Human Intellect With Collaborative, Adaptive, Responsible, and Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Computer 2020, 53, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moravec, H. Mind Children: The Future of Robot and Human Intelligence; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1988; ISBN 0674576187. [Google Scholar]

- Dellermann, D.; Ebel, P.; Söllner, M.; Leimeister, J.M. Hybrid Intelligence. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2019, 61, 637–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Liang, W.; Liang, Y. A Review of Hybrid and Ensemble in Deep Learning for Natural Language Processing. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.05589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavarchee, A. A Hybrid Deep Learning Model for Optimizing Particle Identification Systems. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2024, 303, 109277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, P.; Pahari, S.; Bhavsar, R.; Kwon, J.S.-I. Hybrid Modeling of First-Principles and Machine Learning: A Step-by-Step Tutorial Review for Practical Implementation. Comput. Chem. Eng. 2025, 194, 108926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asiedu, S.T.; Nyarko, F.K.A.; Boahen, S.; Effah, F.B.; Asaaga, B.A. Machine Learning Forecasting of Solar PV Production Using Single and Hybrid Models over Different Time Horizons. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, S.V.S.; Kondaveeti, H.K. Bird Species Recognition Using Transfer Learning with a Hybrid Hyperparameter Optimization Scheme (HHOS). Ecol. Inform. 2024, 80, 102510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Zhu, J.; Dai, Y.; Zhang, C. Multicondition Tool Wear Assessment for Cutting Tools Based on Kernel Principal Component Analysis and Integrated Transfer Learning. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 2519813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.T.; Pan, S.J.; Tsang, I.W. A Deep Learning Framework for Hybrid Heterogeneous Transfer Learning. Artif. Intell. 2019, 275, 310–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Guo, H.; Li, S.; Lin, X. Physics-Informed Deep Learning for Tool Wear Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 524–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutinho, B.; Pereira, E.; Gonçalves, G. 0-DMF: A Decision-Support Framework for Zero Defects Manufacturing. In Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Informatics in Control, Automation and Robotics, Porto, Portugal, 18–20 November 2024; SCITEPRESS—Science and Technology Publications: Setúbal, Portugal, 2024; pp. 253–260. [Google Scholar]

- Papenberg, B.; Hogreve, S.; Tracht, K. Visualization of Relevant Areas of Milling Tools for the Classification of Tool Wear by Machine Learning Methods. Procedia CIRP 2023, 118, 525–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-Y.; Hsieh, C.-J. Construction of a Cutting-Tool Wear Prediction Model through Ensemble Learning. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pashmforoush, F.; Ebrahimi Araghizad, A.; Budak, E. Tool Wear Prediction in Milling Process Using Physics-Informed Machine Learning and Thermo-Mechanical Force Model with Monitoring Applications. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 82, 1192–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dellermann, D.; Calma, A.; Lipusch, N.; Weber, T.; Weigel, S.; Ebel, P. The Future of Human-AI Collaboration: A Taxonomy of Design Knowledge for Hybrid Intelligence Systems. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.03354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtarzadeh, M.; Rodríguez-Echeverría, J.; Semanjski, I.; Gautama, S. Hybrid Intelligence Failure Analysis for Industry 4.0: A Literature Review and Future Prospective. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025, 36, 2309–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leberruyer, N.; Bruch, J.; Ahlskog, M.; Afshar, S. Toward Zero Defect Manufacturing with the Support of Artificial Intelligence—Insights from an Industrial Application. Comput. Ind. 2023, 147, 103877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Moon, H.; Lee, J.; RYu, S. Toward Knowledge-Guided AI for Inverse Design in Manufacturing: A Perspective on Domain, Physics, and Human-AI Synergy. Adv. Intell. Discov. 2025, e202500107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’heureux, A.; Grolinger, K.; Elyamany, H.F.; Capretz, M.A.M. Machine Learning with Big Data: Challenges and Approaches. Ieee Access 2017, 5, 7776–7797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Willard, J.; Karpatne, A.; Read, J.; Zwart, J.; Steinbach, M.; Kumar, V. Physics Guided RNNs for Modeling Dynamical Systems: A Case Study in Simulating Lake Temperature Profiles. In Proceedings of the 2019 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2–4 May 2019; SIAM: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2019; pp. 558–566. [Google Scholar]

- Lagaris, I.E.; Likas, A.; Fotiadis, D.I. Artificial Neural Networks for Solving Ordinary and Partial Differential Equations. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 1998, 9, 987–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karpatne, A.; Atluri, G.; Faghmous, J.H.; Steinbach, M.; Banerjee, A.; Ganguly, A.; Shekhar, S.; Samatova, N.; Kumar, V. Theory-Guided Data Science: A New Paradigm for Scientific Discovery from Data. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2017, 29, 2318–2331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Sicard, B.; Gadsden, S.A. Physics-Informed Machine Learning: A Comprehensive Review on Applications in Anomaly Detection and Condition Monitoring. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 255, 124678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karthik, M.R.; Rao, T.B. Physics-Informed Data-Driven Ensemble and Transfer Learning Approaches for Prediction of Temperature Field and Cutting Force during Machining IN625 Superalloy. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2025, 19, 7027–7060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhang, J.; Qin, F.; Tao, G.; Li, D.; Cao, H. PIDGGCN: A Novel Physics-Informed Deep Learning Framework for Tool Wear Monitoring. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 68, 103790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, C.; Zhao, J. An Augmented AutoEncoder With Multi-Head Attention for Tool Wear Prediction in Smart Manufacturing. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 79128–79137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Zhao, M.; Dai, X.; Chen, Y. A Hybrid-Driven Probabilistic State Space Model for Tool Wear Monitoring. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 200, 110599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, T.; Chitlangia, S.; Ahuja, A.; Srinivasan, A. A Review of Some Techniques for Inclusion of Domain-Knowledge into Deep Neural Networks. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Jeon, G.; Piccialli, F. From Artificial Intelligence to Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Industry 4.0: A Survey on What, How, and Where. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2022, 18, 5031–5042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.-C.T. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) in Manufacturing. In Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) in Manufacturing: Methodology, Tools, and Applications; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, J.-S.; Chen, K.-H. A Novel Decision Support System Based on Computational Intelligence and Machine Learning: Towards Zero-Defect Manufacturing in Injection Molding. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2024, 40, 100621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajgató, G.; Wéber, R.; Szilágyi, B.; Tóthpál, B.; Gyires-Tóth, B.; Hős, C. PredMaX: Predictive Maintenance with Explainable Deep Convolutional Autoencoders. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 54, 101778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr, M.M.; Anwar, S.; Al-Samhan, A.M.; Ghaleb, M.; Dabwan, A. Milling of Graphene Reinforced Ti6Al4V Nanocomposites: An Artificial Intelligence Based Industry 4.0 Approach. Materials 2020, 13, 5707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmetz, A.; Vahl, C.; Zhen, Z.; Reibert, D.; Mayer, S.; Zontar, D.; Garcke, J.; Brecher, C. Decision Support by Interpretable Machine Learning in Acoustic Emission Based Cutting Tool Wear Prediction. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management (IEEM), Singapore, 13–16 December 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 629–633. [Google Scholar]

- Holst, C.; Yavuz, T.B.; Gupta, P.; Ganser, P.; Bergs, T. Deep Learning and Rule-Based Image Processing Pipeline for Automated Metal Cutting Tool Wear Detection and Measurement. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2022, 55, 534–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, H.-X.; Guan, X.-P.; Du, R. Fuzzy Estimation of Feed-Cutting Force From Current Measurement—A Case Study on Intelligent Tool Wear Condition Monitoring. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part C (Appl. Rev.) 2004, 34, 506–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Guo, F.; Gao, H.; Li, M.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, H. Defect Detection of Injection Molding Products on Small Datasets Using Transfer Learning. J. Manuf. Process. 2021, 70, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiyan, V.; Drissi-Daoudi, R.; Shevchik, S.; Masinelli, G.; Le-Quang, T.; Logé, R.; Wasmer, K. Deep Transfer Learning of Additive Manufacturing Mechanisms across Materials in Metal-Based Laser Powder Bed Fusion Process. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2022, 303, 117531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, S.; Song, K.D.; Chung, J.W. Basics of Deep Learning: A Radiologist’s Guide to Understanding Published Radiology Articles on Deep Learning. Korean J. Radiol. 2020, 21, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Lei, Y.; Jia, F.; Xing, S. An Intelligent Fault Diagnosis Approach Based on Transfer Learning from Laboratory Bearings to Locomotive Bearings. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2019, 122, 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Ma, M.; Zhao, Z.; Tian, S.; Yan, R.; Chen, X. Deep Transfer Learning Based on Sparse Autoencoder for Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Tool in Manufacturing. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2019, 15, 2416–2425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marei, M.; El Zaatari, S.; Li, W. Transfer Learning Enabled Convolutional Neural Networks for Estimating Health State of Cutting Tools. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2021, 71, 102145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, Y.; Meng, Q.; Chen, G. Deep Transfer Learning for Conditional Shift in Regression. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 227, 107216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, B.; Zhu, L.; Dun, Y. Tool Wear Monitoring of TC4 Titanium Alloy Milling Process Based on Multi-Channel Signal and Time-Dependent Properties by Using Deep Learning. J. Manuf. Syst. 2021, 61, 495–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papacharalampopoulos, A.; Alexopoulos, K.; Catti, P.; Stavropoulos, P.; Chryssolouris, G. Learning More with Less Data in Manufacturing: The Case of Turning Tool Wear Assessment through Active and Transfer Learning. Processes 2024, 12, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, B.; Chakraborty, S.; Čep, R.; Kalita, K. Development of Optimized Ensemble Machine Learning-Based Prediction Models for Wire Electrical Discharge Machining Processes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 23299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Demircioglu Diren, D.; Ozsoy, N.; Ozsoy, M.; Pehlivan, H. Optimization of Cutting Parameters and Result Predictions with Response Surface Methodology, Individual and Ensemble Machine Learning Algorithms in End Milling of AISI 321. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2023, 48, 12075–12089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, L.G.; Patra, R.K.; Falkowski-Gilski, P.; Divakarachari, P.B.; Antony Marcilin, L.J. Tool Wear Monitoring Using Improved Dragonfly Optimization Algorithm and Deep Belief Network. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ou, J.; Li, H.; Huang, G.; Liu, B.; Wang, Z. Tool Wear Recognition Based on Deep Kernel Autoencoder With Multichannel Signals Fusion. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 3521909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Shi, T.; Xuan, J.; Li, T. Research on Tool Wear Prediction Based on Temperature Signals and Deep Learning. Wear 2021, 478–479, 203902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Huang, M.; Sun, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y. Intelligent Tool Wear Monitoring Method Using a Convolutional Neural Network and an Informer. Lubricants 2023, 11, 389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Echeverria-Rios, D.; Green, P.L. Predicting Product Quality in Continuous Manufacturing Processes Using a Scalable Robust Gaussian Process Approach. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 127, 107233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Granados, G.; Misaka, T.; Herwan, J.; Komoto, H.; Furukawa, Y. An Experimental Study of Multi-Sensor Tool Wear Monitoring and Its Application to Predictive Maintenance. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 133, 3415–3433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.K.; Singh, B.K.; Gupta, S. Prediction of Tool Wear Using Machine Learning Approaches for Machining on Lathe Machine. Evergreen 2023, 10, 1357–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, N.S.; Sheeba, P.T.; Shibi, C.S.; Gupta, M.K.; Korkmaz, M.E.; Sharma, V.S. A Novel Approach of Tool Condition Monitoring in Sustainable Machining of Ni Alloy with Transfer Learning Models. J. Intell. Manuf. 2024, 35, 757–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukunda, S.G.; Srivastava, A.; Boppana, S.B.; Dayanand, S.; Yeshwanth, D. Wear Performance Prediction of MWCNT-Reinforced AZ31 Composite Using Machine Learning Technique. J. Bio- Tribo-Corros. 2023, 9, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Meurer, M.; Bergs, T. Deep Learning Approach for Enhanced Transferability and Learning Capacity in Tool Wear Estimation. Procedia CIRP 2024, 126, 360–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molitor, D.A.; Kubik, C.; Hetfleisch, R.H.; Groche, P. Workpiece Image-Based Tool Wear Classification in Blanking Processes Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Prod. Eng. 2022, 16, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrnjica, B.; Softic, S. Explainable AI in Manufacturing: A Predictive Maintenance Case Study. In IFIP International Conference on Presentation in Production Management Systems; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- Schueller, A.; Saldaña, C. Indirect Tool Condition Monitoring Using Ensemble Machine Learning Techniques. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2023, 145, 011006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulas, M.; Altay, O.; Gurgenc, T.; Özel, C. A New Approach for Prediction of the Wear Loss of PTA Surface Coatings Using Artificial Neural Network and Basic, Kernel-Based, and Weighted Extreme Learning Machine. Friction 2020, 8, 1102–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thankachan, T.; Soorya Prakash, K.; Kavimani, V.; Silambarasan, S.R. Machine Learning and Statistical Approach to Predict and Analyze Wear Rates in Copper Surface Composites. Met. Mater. Int. 2021, 27, 220–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, F. The Investigation of the Effect of Particle Size on Wear Performance of AA7075/Al2O3 Composites Using Statistical Analysis and Different Machine Learning Methods. Adv. Powder Technol. 2021, 32, 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hybrid Category | Core Components | Integration Architecture | Synergistic Benefit | Example Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physics-Informed Hybrids | 1. Deep Learning (LSTM) 2. Physical Models (Taylor’s equations) | Physical equations and cutting parameters were integrated into the deep learning model’s loss function and input features. | Generalization with limited data and physical consistency: The model demonstrated a significant improvement in prediction accuracy and provided more consistent results under varying conditions compared to purely data-driven models. | Zhu et al. (2024): Developed a model for cutting tool wear prediction by integrating physical laws with deep learning [43]. |

| Knowledge-Guided Hybrids | 1. Machine Learning (CatBoost, XGBoost) 2. Explainable AI (XAI—SHAP, LIME) | Model predictions were explained to operators using SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) and Local Interpretable Model-agnostic Explanations (LIME), guiding expert intervention based on these explanations. | Transparency, trust, and actionable insights: The “black box” model was transformed into a decision-support system that operators could understand and trust, achieving a very high defect detection rate. | Coutinho et al. (2024): Proposed a Zero Defect Manufacturing framework that predicts faults and explains them using XAI [44]. |

| Transfer Learning Hybrids | 1. Pre-trained CNN (on ImageNet) 2. Target Task (Tool Wear) | A CNN (EfficientNetB0) pre-trained on general image features was fine-tuned on a relatively small dataset of milling tools. | High performance with limited data: Enabled achieving a very high classification accuracy from a small, domain-specific dataset, which would be difficult with training from scratch. | Papenberg et al. (2023): Utilized transfer learning to classify milling tool wear [45]. |

| Heterogeneous Model Hybrids | 1. Ensemble Learning 2. Multiple Algorithms (SVM, DT, LR, LDA) | An ensemble was created by strategically combining predictions from different base algorithms (SVM, Decision Trees, etc.). | Enhanced robustness and reliability: Mitigated the weaknesses of any single model by leveraging the strengths of diverse algorithms, leading to more stable and reliable predictions. | Lin and Hsieh (2024): Developed a heterogeneous ensemble learning model for tool wear prediction [46]. |

| Study | Method | Source of Physical Knowledge | Hybrid Integration Logic | Target Application | Hybrid Rationale | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [43] | Physics-informed deep learning (ADHL-LSTM) | Cutting parameters, Taylor equations, physical residual modeling | Physics-Informed Hybrid: Physical equations (Taylor) and residual modeling are incorporated into the LSTM’s architecture and multi-task loss function, enhancing the model’s adherence to physical processes and its generalization ability under limited data conditions. | Cutting tool wear monitoring in high-speed milling | Massive increase in prediction accuracy compared to purely data-driven or physics-based methods. Robust results with limited data due to the integration of physical knowledge. | Influence from low signal-to-noise ratio labels; residual learning method failing to provide the expected improvement; scalability to different production types (e.g., turning, drilling) not fully demonstrated. |

| [47] | PIML | Thermo-mechanical force model that accounts for wear effects | Physics-Informed Hybrid: A physical force and wear model is combined with machine learning algorithms (LSBoost, SVR, etc.), and an inverse modeling strategy enables the direct prediction of tool wear from cutting parameters. | Milling tool wear & force prediction | The combination of the explainability of the physical model with the predictive power of ML. High reliability with less experimental data. | Narrow validation (only Steel 1050 and a specific tool geometry); potential need for a larger dataset due to the complex wear-force relationship. |

| [57] | Hybrid physics-based & data-driven approach | Finite Element (FE) simulations (Johnson–Cook material model, Coulomb–Tresca friction, ALE re-mesh) | Physics-Informed Hybrid: Physically validated simulations are used as a rich and reliable data source to train various ML algorithms (AdaBoost, SVR, etc.), ensuring predictions are grounded in physical principles. | Machining of Ni-based superalloy IN625 (cutting temperature & force prediction) | Speed and lower cost compared to expensive physical experiments; increased reliability due to results consistent with theoretical expectations. | High simulation cost; hyperparameter sensitivity |

| [58] | PIDGGCN | Physics-based regularizers; spatio-temporal dependencies in machining data | Physics-Informed Hybrid: Physical principles (regularizers) and spatio-temporal relationships are integrated into the deep learning model’s graph structure, creating a more accurate and lightweight model that observes monotonic wear progression. | Tool wear monitoring in machining of titanium alloy thin-walled parts & CFRP composites | The combination of high accuracy and low computational cost (lightweight model) makes it ideal for real-time industrial applications. | Continued reliance on labeled data for noisy data across different cutting conditions; limited ability to interpret complex wear behaviors. |

| [59] | Physics-Informed MCAG | Principle of progressive tool wear | Physics-Informed Hybrid: A custom monotonicity loss function is added to the training objective, penalizing non-increasing predictions and hard-coding the physical law of wear progression into the data-driven model. | Tool wear prediction | Ensures predictions are physically plausible and increases model reliability, especially in data-sparse regimes. | High computational cost; reliance on the strict monotonicity assumption, which might not hold in all scenarios (e.g., tool changes, run-in periods). |

| Study | Hybrid Category | Integration Architecture | Application Domain | Hybrid Rationale | Limitations and Future Work |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [64] | Knowledge-Guided Hybrid | Integration of a heuristic optimizer (PSO) with a transparent classifier (C4.5 decision tree) to encode decision rules. | Zero-Defect Manufacturing (ZDM) in Injection Molding | Structural Transparency and Actionable Guidance: The model’s intrinsic interpretability builds operator trust and provides a concrete basis for preventive interventions. | Risk of optimizer convergence to local minima; generalizability is constrained to symmetric mold geometries. |

| [65] | Knowledge-Guided Hybrid | Combination of a Deep Convolutional Autoencoder (DCAE) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) for anomaly detection. Model outputs are explained using Integrated Gradients (IG). | Lubricant Degradation Detection in a Gearbox | Diagnosable Anomaly Detection: The system not only identifies faults but also pinpoints the critical sensor channels responsible, enabling informed maintenance decisions. | High sensitivity to DCAE hyperparameters; requires pre-definition of the number of clusters. |

| [66] | Knowledge-Guided Hybrid | An Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System (ANFIS) encodes expert knowledge, which is then optimized using Multi-Objective Particle Swarm Optimization (MOPSO) to identify feasible process parameters. | Milling of Ti6Al4V/GNP Nanocomposites | Expert Knowledge Capture & Multi-Objective Optimization: The fuzzy logic base provides interpretable predictions, while the optimization balances conflicting objectives (e.g., surface quality vs. cutting force). | Validated within a narrow range of material compositions and process parameters; scalability to other material systems remains unverified. |

| [44] | Knowledge-Guided Hybrid | Predictions from high-performance gradient boosting models (CatBoost, XGBoost) are explained globally and locally using model-agnostic XAI methods (SHAP, LIME). | Zero-Defect Manufacturing in Wood Panel Production | Operator-Level Transparency and System Trust: “Black-box” predictions are translated into intuitive explanations that operators can reconcile with their expert intuition, strengthening human–machine collaboration. | Reliance on SMOTE for class imbalance; the application scope is limited to a specific production line. |

| [67] | Knowledge-Guided Hybrid | A Random Forest (RF) model was selected for its inherent interpretability; decision contributions are communicated to operators visually and audibly using a Tree Interpreter. | Tool Wear Prediction in Ultra-Precision Turning | Operator Training and Decision Verification: Visualizing the model’s decision-making process aids operator understanding of process dynamics and increases trust in model outputs. | Lack of comprehensive user studies; challenges in effectively representing frequencies beyond the human auditory range. |

| [68] | Knowledge-Guided Hybrid | CNN (for detection) + U-Net (for segmentation) + Rule-based algorithm (for measurement) | Automated tool wear measurement in metal cutting | Automation & Interpretability: The measurement rule transforms the black-box model output into a tangible, meaningful, and reliable metric, enhancing interpretability and trust. | Limitations: Small dataset, focus on flank wear only, limited explainability of segmentation. Future Work: Expand datasets, model multiple wear types, connect segmentation outcomes with final part properties. |

| Study | Hybrid Category | Integration Architecture | Application Domain | Hybrid Rationale | Limitations and Future Work |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [75] | Transfer Learning Hybrids | Fine-tuning of a ResNet-18 model, pre-trained on ImageNet, with a limited set of microscopic tool images. | CNC Tool Wear Prediction | Adapts features learned from a large-scale, general image dataset to a data-constrained manufacturing problem, achieving high accuracy. | Dataset imbalance; long training times for deep models; not yet validated in real-time systems. Future work suggests sensor fusion and reinforcement learning integration. |

| [77] | Transfer Learning Hybrids | A Deep Transfer Learning (DTL) architecture (CDAR model) combining MSE and CEOD loss functions to mitigate conditional distribution shift between source and target domains. | Machine Health Monitoring (PHM- Prognostics and Health Management) | Enables strong generalization with limited labeled data; novel loss integration improves accuracy by preserving global conditional distribution properties. | Low explainability; high computational cost; complex hyperparameter tuning. Future research suggests incorporating active learning and enhancing interpretability. |

| [45] | Transfer Learning Hybrids | Fine-tuning of an EfficientNetB0 CNN, pre-trained on ImageNet, for milling tool wear classification, supplemented with Grad-CAM for explainability. | Tool Condition Monitoring | Achieves high classification accuracy from a small dataset; provides partial interpretability by visualizing the model’s decision points. | Sensitivity to lighting conditions; incomplete detection of some wear indicators (e.g., cracks). Future work requires a new approach that integrates domain-specific knowledge (e.g., focus on the cutting edge) into the decision process. |

| [78] | Transfer Learning Hybrids | Multi-channel force and acceleration signals transformed into spectrograms via STFT and fed into a ResNet-18 model pre-trained on ImageNet. | Real-time Tool Wear Prediction in Milling | Leverages a large, unique dataset for stable and low-error predictions; transfer learning allows adaptation to varying signal lengths and channel settings. | Low explainability; poor Acoustic Emission (AE) signal quality; prediction fluctuations with input changes. Future work will acquire more data to supplement the existing dataset and study more kinds of fine-tuning for other processing environments and conditions. |

| Study | Hybrid Category | Component Algorithms/Methods | Hybrid Integration Logic | Target Application | Qualitative Benefit/Hybrid Purpose | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [46] | Heterogeneous Model Hybrid | 10 different ML models + Voting Regressor | Parallel Ensemble: Combines diverse base learners through a voting mechanism to average out errors and reduce variance. | Tool wear prediction in SKD11 steel milling | Robust & Generalizable Predictions: Mitigates the bias of any single model, leading to more stable and reliable predictions. | Tested on a single tool-workpiece combination. |

| [81] | Heterogeneous Model Hybrid | ANN + Decision Tree + k-NN | Comparative Ensemble (Soft Hybrid): Uses multiple, fundamentally different algorithms in parallel; the best-performing model for each output variable is selected, leveraging their inherent strengths. | Cutting force and surface roughness prediction in milling | Complementary Strength Utilization: Acknowledges that no single algorithm is best for all tasks; selects the most suitable model for each specific output. | Small dataset; lack of model explainability. |

| [82] | Heterogeneous Model Hybrid | IDOA + Deep Belief Network (DBN) | Optimization-Model Hybrid: Uses a metaheuristic algorithm (IDOA) to optimize the hyperparameters and feature space for a deep learning model (DBN). | Tool wear classification from tool edge images | Performance & Efficiency: The optimization algorithm ensures the DBN operates at its peak potential. | Small dataset; “black-box” nature. |

| [83] | Heterogeneous Model Hybrid | Deep Kernel Autoencoder (DKAE) + Gray Wolf Optimization (GWO) | Feature Extraction-Classifier Hybrid: Uses an unsupervised DKAE for non-linear, kernel-based feature compression, followed by GWO-optimized classification. | Tool wear detection from spindle motor current signals | Interpretability & Efficiency: The kernel-based feature extraction provides a more interpretable signal structure than raw data. | Reliance on a limited dataset and a single sensor type. |

| [84] | Heterogeneous Model Hybrid | Stacked Sparse Autoencoder (SSAE) + BPNN | Deep Feature Extraction Hybrid: Uses an unsupervised SSAE for automatic feature learning from sensor signals, the outputs of which are then fed into a BPNN for supervised regression. | Tool wear prediction on a CNC lathe | Automatic Feature Engineering: Eliminates the need for manual feature engineering by leveraging the SSAE’s ability to learn robust features directly from raw data. | Requires specialized sensors; high computational cost. |

| [85] | Heterogeneous Model Hybrid | CNN + Informer Encoder + BiLSTM (CIEBM) | Deep Architectural Hybrid: Integrates three distinct deep learning architectures: CNN for local features, Informer for long-sequence dependencies, and BiLSTM for bidirectional temporal context. | Tool wear monitoring | Multi-scale Temporal Feature Fusion: Combines strengths for both short-term and very long-term pattern recognition, leading to superior accuracy. | High computational complexity. |

| [86] | Heterogeneous Model Hybrid | Dirichlet Process Clustering + Gaussian Process Regression (DPGP) | Pre-processing-Model Hybrid: Uses a non-parametric clustering method to automatically identify and filter out faulty data, creating a clean dataset for a robust regression model. | Product quality prediction in continuous manufacturing | Robustness & Uncertainty Quantification: The hybrid system is inherently robust to sensor faults and provides reliable predictions with well-calibrated uncertainty estimates. | Limited real-time efficiency on large datasets. |

| Dimension | Non-Hybrid Example | Hybrid Example | Conceptual Distinction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Model Type | Random Forest (RF) [88] | Physics-Informed Deep Learning (ADHL-LSTM) [43] | RF relies purely on statistical correlations among input variables, whereas ADHL-LSTM embeds physical residuals (Taylor equations) within a deep network, aligning predictions with physical processes. |

| Integration Principle | CNN (ResNet, VGG-16) [89]–Single deep learning paradigm trained only on image data | Knowledge-Guided Hybrid (DCAE + PCA + IG) [65].–Combines autoencoder-based learning with explainable AI (Integrated Gradients) | Hybrid models integrate data-driven learning and expert-guided interpretability, while non-hybrid CNNs extract patterns without incorporating domain knowledge. |

| Learning Scope | XGBoost [90]–Homogeneous ensemble of decision trees | Transfer Learning Hybrid (CDAR model) [77]–Combines source-domain representation learning with target-domain adaptation | Hybrid systems leverage cross-domain knowledge transfer, while non-hybrid ensembles remain limited to a single dataset or environment. |

| Algorithmic Diversity | Adaptive CNN [91]–Self-updating within one algorithmic family | Heterogeneous Model Hybrid (ANN + DT + kNN) [81]–Integrates fundamentally different algorithms in parallel to exploit their complementary strengths | Hybrids combine diverse learning paradigms to balance accuracy and robustness, whereas non-hybrids rely on a single methodological family. |

| Knowledge Incorporation | Data-driven models trained solely on experimental data without explicit physics or expert rules | Hybrid frameworks integrate physical laws, rule-based logic, or domain expertise to guide learning and enhance interpretability | Non-hybrid systems depend mainly on statistical correlations, whereas hybrid systems combine data-driven learning with physical or expert knowledge to ensure interpretability and physical realism. |

| Expected Strength | High accuracy under narrow experimental conditions; limited adaptability | Enhanced generalization, interpretability, and robustness under variable industrial conditions | Hybrid systems are designed to overcome the structural fragility and context dependence of non-hybrid methods. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Saatci, B.T.; Ulas, M.; Gurgenc, T. Hybrid AI Systems for Tool Wear Monitoring in Manufacturing: A Systematic Review. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010208

Saatci BT, Ulas M, Gurgenc T. Hybrid AI Systems for Tool Wear Monitoring in Manufacturing: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):208. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010208

Chicago/Turabian StyleSaatci, Busra Tan, Mustafa Ulas, and Turan Gurgenc. 2026. "Hybrid AI Systems for Tool Wear Monitoring in Manufacturing: A Systematic Review" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010208

APA StyleSaatci, B. T., Ulas, M., & Gurgenc, T. (2026). Hybrid AI Systems for Tool Wear Monitoring in Manufacturing: A Systematic Review. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 208. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010208