Tensile Strain Effect on Thermoelectric Properties in Epitaxial CaMnO3 Thin Films

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Synthesis and Characterization of Thin Films

2.2. Evaluation of Thermoelectric Properties

2.3. Evaluation of Carrier Properties

3. Results

3.1. Structural Characterization of CMO Thin Films

3.2. Strain-Dependent Oxygen Vacancies in CMO Films

3.3. Thermoelectric Properties of CMO Thin Films

3.4. Carrier Properties of CMO Thin Films

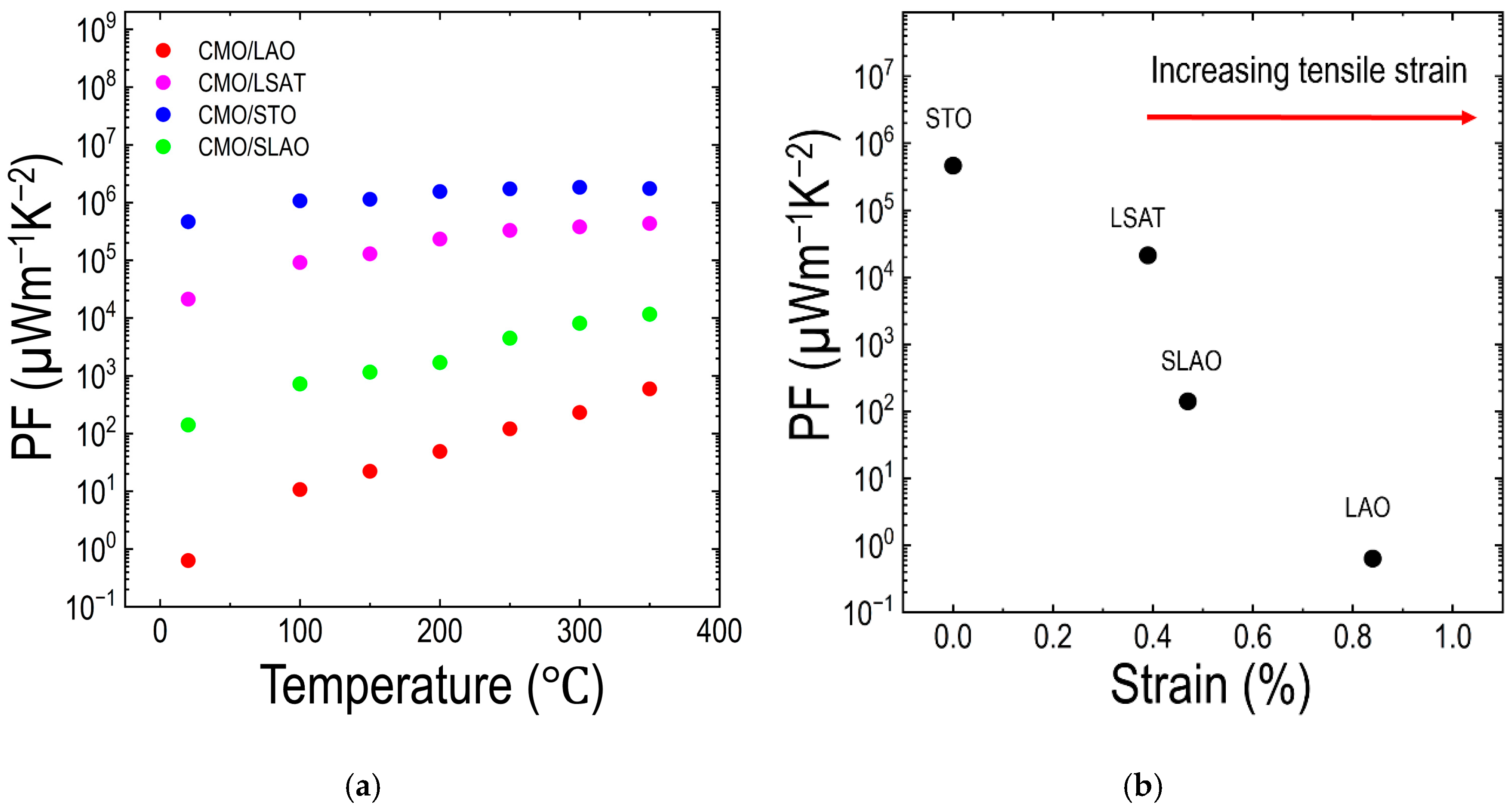

3.5. Power Factor of CMO Thin Films

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- DiSalvo, F.J. Thermoelectric cooling and power generation. Science 1999, 285, 703–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Dresselhaus, M.; Dresselhaus, G.; Fleurial, J.-P.; Caillat, T. Recent developments in thermoelectric materials. Int. Mater. Rev. 2003, 48, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, G.J.; Toberer, E.S. Complex thermoelectric materials. Nat. Mater. 2008, 7, 105–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perumal, S.; Roychowdhury, S.; Biswas, K. Reduction of thermal conductivity through nanostructuring enhances the thermoelectric figure of merit in Ge1−xBixTe. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2016, 3, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, H.; Ramakrishna, S. A review on the enhancement of figure of merit from bulk to nano-thermoelectric materials. Nano Energy 2013, 2, 190–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Channegowda, M.; Mulla, R.; Nagaraj, Y.; Lokesh, S.; Nayak, S.; Mudhulu, S.; Rastogi, C.K.; Dunnill, C.W.; Rajan, H.K.; Khosla, A. Comprehensive insights into synthesis, structural features, and thermoelectric properties of high-performance inorganic chalcogenide nanomaterials for conversion of waste heat to electricity. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 7913–7943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabri, M.; Masoumi, S.; Sajadirad, F.; West, R.P.; Pakdel, A. Thermoelectric energy conversion in buildings. Mater. Today Energy 2023, 32, 101257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhi, J.; Li, W.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y. Oxide materials for thermoelectric conversion. Molecules 2023, 28, 5894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Sui, Y.; Fan, H.; Wang, X.; Su, Y.; Su, W.; Liu, X. High temperature thermoelectric response of electron-doped CaMnO3. Chem. Mater. 2009, 21, 4653–4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Jiang, X.; Ghafari, E.; Kucukgok, B.; Zhang, C.; Ferguson, I.; Lu, N. Metal oxides for thermoelectric power generation and beyond. Adv. Compos. Hybrid Mater. 2018, 1, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nag, A.; Shubha, V. Oxide thermoelectric materials: A structure–property relationship. J. Electron. Mater. 2014, 43, 962–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koumoto, K.; Terasaki, I.; Funahashi, R. Complex oxide materials for potential thermoelectric applications. MRS Bull. 2006, 31, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funahashi, R.; Kosuga, A.; Miyasou, N.; Takeuchi, E.; Urata, S.; Lee, K.; Ohta, H.; Koumoto, K. Thermoelectric properties of CaMnO3 system. In Proceedings of the 2007 26th International Conference on Thermoelectrics, Jeju, Republic of Korea, 3–7 June 2007; pp. 124–128. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S.; Wang, H.; Bu, T.; Wang, X.; Dong, Z.; Zhang, M.; Li, C.; Zhao, W. Utilization of doping and compositing strategy for enhancing the thermoelectric performance of CaMnO3 perovskite. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 37119–37125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Du, N.; Rahman, J.U.; Huy, P.T.; Shin, W.H.; Seo, W.-S.; Kim, M.H.; Lee, S. X-site aliovalent substitution decoupled charge and phonon transports in XYZ half-Heusler thermoelectrics. Acta Mater. 2019, 166, 650–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Wang, C.; Su, W.; Li, J.; Liu, J.; Du, Y.; Mei, L. High-temperature thermoelectric performance of Ca0.96Dy0.02RE0.02MnO3 ceramics (RE=Ho, Er, Tm). Ceram. Int. 2014, 40, 15531–15536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-H.; Su, W.-B.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y.-C.; Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Du, Y.; Wang, C.-L. Effects of Dy and Yb co-doping on thermoelectric properties of CaMnO3 ceramics. Ceram. Int. 2015, 41, 1535–1539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiel, P.; Eilertsen, J.; Populoh, S.; Saucke, G.; Döbeli, M.; Shkabko, A.; Sagarna, L.; Karvonen, L.; Weidenkaff, A. Influence of tungsten substitution and oxygen deficiency on the thermoelectric properties of CaMnO3−δ. J. Appl. Phys. 2013, 114, 243707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yin, Y.; Che, C.; Cui, M. Research Progress of Thermoelectric Materials—A Review. Energies 2025, 18, 2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehkordi, A.M.; Zebarjadi, M.; He, J.; Tritt, T.M. Thermoelectric power factor: Enhancement mechanisms and strategies for higher performance thermoelectric materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2015, 97, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petsagkourakis, I.; Pavlopoulou, E.; Cloutet, E.; Chen, Y.F.; Liu, X.; Fahlman, M.; Berggren, M.; Crispin, X.; Dilhaire, S.; Fleury, G. Correlating the Seebeck coefficient of thermoelectric polymer thin films to their charge transport mechanism. Org. Electron. 2018, 52, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschauer, U.; Pfenninger, R.; Selbach, S.M.; Grande, T.; Spaldin, N.A. Strain-controlled oxygen vacancy formation and ordering in CaMnO3. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 2013, 88, 054111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayeshiba, T.; Morgan, D. Strain effects on oxygen vacancy formation energy in perovskites. Solid State Ion. 2017, 311, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasena, R.U.; Yang, W.; Lei, Q.; Delgado-Jaime, M.U.; Wijesekara, K.D.; Golalikhani, M.; Davidson, B.A.; Arenholz, E.; Kobayashi, K.; Kobata, M. Strain-engineered oxygen vacancies in CaMnO3 thin films. Nano Lett. 2017, 17, 794–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Khalek, E.; Mohamed, E.; Ismail, Y.A. Study the role of oxygen vacancies and Mn oxidation states in nonstoichiometric CaMnO3-δ perovskite nanoparticles. J. Sol Gel Sci. Technol. 2025, 113, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkulov, O.; Shamsutov, I.; Ryzhkov, M.; Politov, B.; Baklanova, I.; Chulkov, E.; Zhukov, V. Impact of oxygen vacancies on thermal and electronic transport of donor-doped CaMnO3-δ. J. Solid State Chem. 2023, 326, 124231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; El Loubani, M.; Chalaki, H.R.; Kim, J.; Keum, J.K.; Rouleau, C.M.; Lee, D. Tuning ionic conductivity in fluorite Gd-doped CeO2-Bixbyite RE2O3 (RE = Y and Sm) multilayer thin films by controlling interfacial strain. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 2023, 5, 4556–4563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; El Loubani, M.; Handrick, D.; Stevenson, C.; Lee, D. Understanding the influence of strain-modified oxygen vacancies and surface chemistry on the oxygen reduction reaction of epitaxial La0.8Sr0.2CoO3-δ thin films. Solid State Ion. 2023, 393, 116171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Jacobs, R.; Jee, Y.; Seo, A.; Sohn, C.; Ievlev, A.V.; Ovchinnikova, O.S.; Huang, K.; Morgan, D.; Lee, H.N. Stretching epitaxial La0.6Sr0.4CoO3−δ for fast oxygen reduction. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 25651–25658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, T.L.; Jacobs, R.; Lee, D.; Jiang, L.; Freeland, J.W.; Sohn, C.; Egami, T.; Morgan, D.; Lee, H.N. Strain control of oxygen kinetics in the Ruddlesden-Popper oxide La1.85Sr0.15CuO4. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayeshiba, T.; Morgan, D. Strain effects on oxygen migration in perovskites. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 2715–2721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herklotz, A.; Lee, D.; Guo, E.-J.; Meyer, T.L.; Petrie, J.R.; Lee, H.N. Strain coupling of oxygen non-stoichiometry in perovskite thin films. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 2017, 29, 493001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aidhy, D.S.; Liu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Weber, W.J. Strain-induced phase and oxygen-vacancy stability in ionic interfaces from first-principles calculations. J. Phys. Chem. C 2014, 118, 30139–30144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mouyane, M.; Itaalit, B.; Bernard, J.; Houivet, D.; Noudem, J.G. Flash combustion synthesis of electron doped-CaMnO3 thermoelectric oxides. Powder Technol. 2014, 264, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, S.d.O.; Thomazini, D.; Balthazar, G.P.; Gelfuso, M.V. Microstructural influence on thermoelectric properties of CaMnO3 ceramics. Mater. Res. 2020, 23, e20200169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanas, N.; Williamson, B.A.; Steinbach, F.; Hinterding, R.; Einarsrud, M.-A.; Selbach, S.M.; Feldhoff, A.; Wiik, K. Tuning the thermoelectric performance of CaMnO3-based ceramics by controlled exsolution and microstructuring. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2022, 5, 12396–12407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.P.; Kanas, N.; Desissa, T.D.; Einarsrud, M.-A.; Norby, T.; Wiik, K. Thermoelectric properties of non-stoichiometric CaMnO3-δ composites formed by redox-activated exsolution. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 2020, 40, 1344–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J. Protocols for the high temperature measurement of the Seebeck coefficient in thermoelectric materials. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2013, 24, 085601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, G.J.; Snyder, A.H.; Wood, M.; Gurunathan, R.; Snyder, B.H.; Niu, C. Weighted mobility. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 2001537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katase, T.; He, X.; Tadano, T.; Tomczak, J.M.; Onozato, T.; Ide, K.; Feng, B.; Tohei, T.; Hiramatsu, H.; Ohta, H. Breaking of Thermopower–Conductivity Trade-Off in LaTiO3 Film around Mott Insulator to Metal Transition. Adv. Sci. 2021, 8, 2102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namiki, H.; Kobayashi, M.; Nagata, K.; Saito, Y.; Tachibana, N.; Ota, Y. Relationship between the density of states effective mass and carrier concentration of thermoelectric phosphide Ag6Ge10P12 with strong mechanical robustness. Mater. Today Sustain. 2022, 18, 100116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korte, C.; Peters, A.; Janek, J.; Hesse, D.; Zakharov, N. Ionic conductivity and activation energy for oxygen ion transport in superlattices—The semicoherent multilayer system YSZ (ZrO2 + 9.5 mol% Y2O3)/Y2O3. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2008, 10, 4623–4635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, W.T.; Gadre, M.; Lee, Y.-L.; Biegalski, M.D.; Christen, H.M.; Morgan, D.; Shao-Horn, Y. Tuning the spin state in LaCoO3 thin films for enhanced high-temperature oxygen electrocatalysis. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013, 4, 2493–2499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitterdorfer, A.; Gauckler, L. La2Zr2O7 formation and oxygen reduction kinetics of the La0.85Sr0.15MnyO3, O2(g)|YSZ system. Solid State Ion. 1998, 111, 185–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunkel, F.; Christensen, D.V.; Chen, Y.; Pryds, N. Oxygen vacancies: The (in) visible friend of oxide electronics. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2020, 116, 120505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyunina, M.; Pacherova, O.; Kocourek, T.; Dejneka, A. Anisotropic chemical expansion due to oxygen vacancies in perovskite films. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 15247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyunina, M.; Peräntie, J.; Kocourek, T.; Saukko, S.; Jantunen, H.; Jelinek, M.; Dejneka, A. Oxygen vacancy dipoles in strained epitaxial BaTi O3 films. Phys. Rev. Res. 2020, 2, 023056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyunina, M.; Levoska, J.; Pacherova, O.; Kocourek, T.; Dejneka, A. Strain enhancement due to oxygen vacancies in perovskite oxide films. J. Mater. Chem. C 2022, 10, 6770–6777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aidhy, D.S.; Rawat, K. Coupling between interfacial strain and oxygen vacancies at complex-oxides interfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 2021, 129, 171102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Z.; Vegge, T.; Castelli, I.E. Exploring the electronic properties and oxygen vacancy formation in SrTiO3 under strain. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2024, 231, 112623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Weber, W.J. Strain effects on oxygen vacancy energetics in KTaO3. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 6264–6273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.H.; Kim, S.; Lim, J.C.; Cho, J.Y.; Yang, H.; Kim, H.S. Approach to determine the density-of-states effective mass with carrier concentration-dependent Seebeck coefficient. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2022, 32, 2203852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhansali, S.; Khunsin, W.; Chatterjee, A.; Santiso, J.; Abad, B.; Martín-González, M.; Jakob, G.; Torres, C.S.; Chávez-Angel, E. Enhanced thermoelectric properties of lightly Nb doped SrTiO3 thin films. Nanoscale Adv. 2019, 1, 3647–3653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Liu, S.; Piao, Y.; Jia, B.; Yuan, Y.; Wang, Q. Joint improvement of conductivity and Seebeck coefficient in the ZnO: Al thermoelectric films by tuning the diffusion of Au layer. Mater. Des. 2018, 154, 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, V.; Mensch, P.F.; Karg, S.F.; Gotsmann, B.; Das Kanungo, P.; Schmid, H.; Riel, H. Using the Seebeck coefficient to determine charge carrier concentration, mobility, and relaxation time in InAs nanowires. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2014, 104, 012113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roguai, S.; Djelloul, A. Sn doping effects on the structural, microstructural, Seebeck coefficient, and photocatalytic properties of ZnO thin films. Solid State Commun. 2022, 350, 114740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Xiao, Y.; Ren, D.; Su, L.; Qiu, Y.; Zhao, L.-D. Enhancing thermoelectric performance of BiSbSe3 through improving carrier mobility via percolating carrier transports. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 836, 155473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movaghar, B.; Jones, L.O.; Ratner, M.A.; Schatz, G.C.; Kohlstedt, K.L. Are transport models able to predict charge carrier mobilities in organic semiconductors? J. Phys. Chem. C 2019, 123, 29499–29512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, A.; Zhu, K.; Zhong, H.; Shao, Q.; Ge, G. A new investigation of oxygen flow influence on ITO thin films by magnetron sputtering. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 2014, 120, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werner, F. Hall measurements on low-mobility thin films. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 122, 135306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganguly, K.; Prakash, A.; Jalan, B.; Leighton, C. Mobility-electron density relation probed via controlled oxygen vacancy doping in epitaxial BaSnO3. APL Mater. 2017, 5, 056102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffei, R.M.; di Bona, A.; Sygletou, M.; Bisio, F.; D’Addato, S.; Benedetti, S. Suppression of grain boundary contributions on carrier mobility in thin Al-doped ZnO epitaxial films. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 624, 157133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Román Acevedo, W.; Aguirre, M.H.; Noheda, B.; Rubi, D. Oxygen vacancy engineering in pulsed laser deposited BaSnO3 thin films on SrTiO3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2025, 127, 061904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Huang, H.; Zou, W.; Yang, M.; Peng, R.; Yan, W.; Huang, Q. Oxygen deficiency induced strong electron localization in lanthanum doped transparent perovskite oxide BaSnO3. Phys. Rev. B 2019, 100, 165312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosendal, V.; Pryds, N.; Petersen, D.H.; Brandbyge, M. Electron-vacancy scattering in SrNbO3 and SrTiO3: A density functional theory study with nonequilibrium Green’s functions. Phys. Rev. B 2024, 109, 205129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Loubani, M.; Yang, G.; Kouzehkanan, S.M.T.; Oh, T.-S.; Balijepalli, S.K.; Lee, D. Influence of redox engineering on the trade-off relationship between thermopower and electrical conductivity in lanthanum titanium based transition metal oxides. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 9007–9017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Walter, J.; Feng, T.; Zhu, J.; Zheng, H.; Mitchell, J.F.; Biškup, N.; Varela, M.; Ruan, X.; Leighton, C. Glass-Like Through-Plane Thermal Conductivity Induced by Oxygen Vacancies in Nanoscale Epitaxial La0.5Sr0.5CoO3−δ. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1704233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, G.-K.; Lan, J.-L.; Ventura, K.J.; Tan, X.; Lin, Y.-H.; Nan, C.-W. Contribution of point defects and nano-grains to thermal transport behaviours of oxide-based thermoelectrics. npj Comput. Mater. 2016, 2, 16023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, D.M. Materials, Preparation, and Characterization in Thermoelectrics; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Sarantopoulos, A.; Saha, D.; Ong, W.-L.; Magén, C.; Malen, J.A.; Rivadulla, F. Reduction of thermal conductivity in ferroelectric SrTiO3 thin films. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2020, 4, 054002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fumega, A.O.; Fu, Y.; Pardo, V.; Singh, D.J. Understanding the lattice thermal conductivity of SrTiO3 from an ab initio perspective. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2020, 4, 033606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrie, J.R.; Mitra, C.; Jeen, H.; Choi, W.S.; Meyer, T.L.; Reboredo, F.A.; Freeland, J.W.; Eres, G.; Lee, H.N. Strain control of oxygen vacancies in epitaxial strontium cobaltite films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2016, 26, 1564–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Seesi, E.; El Loubani, M.; Rostaghi Chalaki, H.; Suber, A.; Kincaid, C.; Lee, D. Tensile Strain Effect on Thermoelectric Properties in Epitaxial CaMnO3 Thin Films. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010193

Seesi E, El Loubani M, Rostaghi Chalaki H, Suber A, Kincaid C, Lee D. Tensile Strain Effect on Thermoelectric Properties in Epitaxial CaMnO3 Thin Films. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):193. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010193

Chicago/Turabian StyleSeesi, Ebenezer, Mohammad El Loubani, Habib Rostaghi Chalaki, Avari Suber, Caden Kincaid, and Dongkyu Lee. 2026. "Tensile Strain Effect on Thermoelectric Properties in Epitaxial CaMnO3 Thin Films" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010193

APA StyleSeesi, E., El Loubani, M., Rostaghi Chalaki, H., Suber, A., Kincaid, C., & Lee, D. (2026). Tensile Strain Effect on Thermoelectric Properties in Epitaxial CaMnO3 Thin Films. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010193