Honey Bee Lifecycle Activity Prediction Using Non-Invasive Vibration Monitoring

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Honey Bee Colony Lifecycle

1.2. Our Approach

- 1.

- The creation of a honey bee vibration dataset spanning a whole apicultural season, recorded using wholly non-invasive techniques with accelerometers positioned on top of brood frames.

- 2.

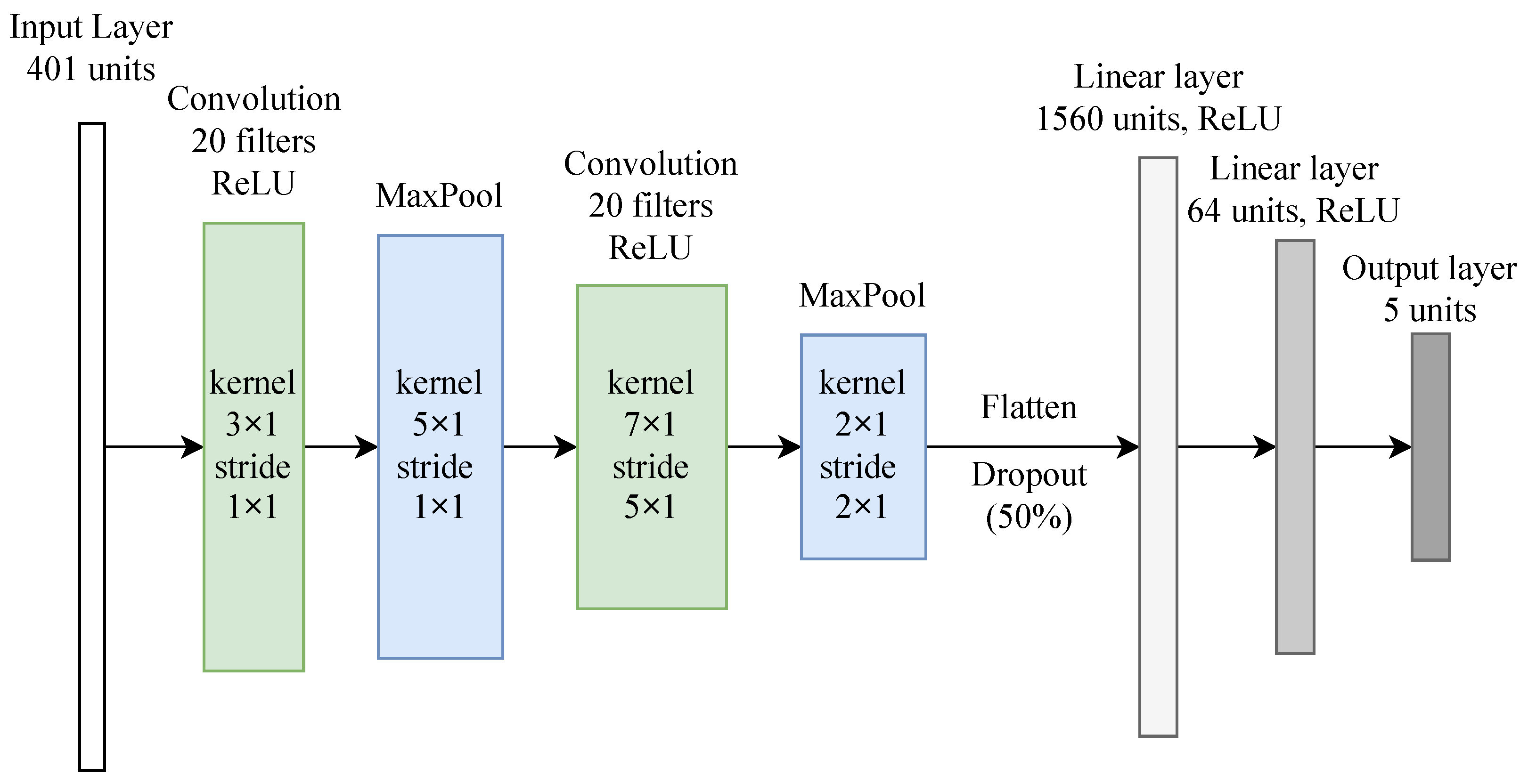

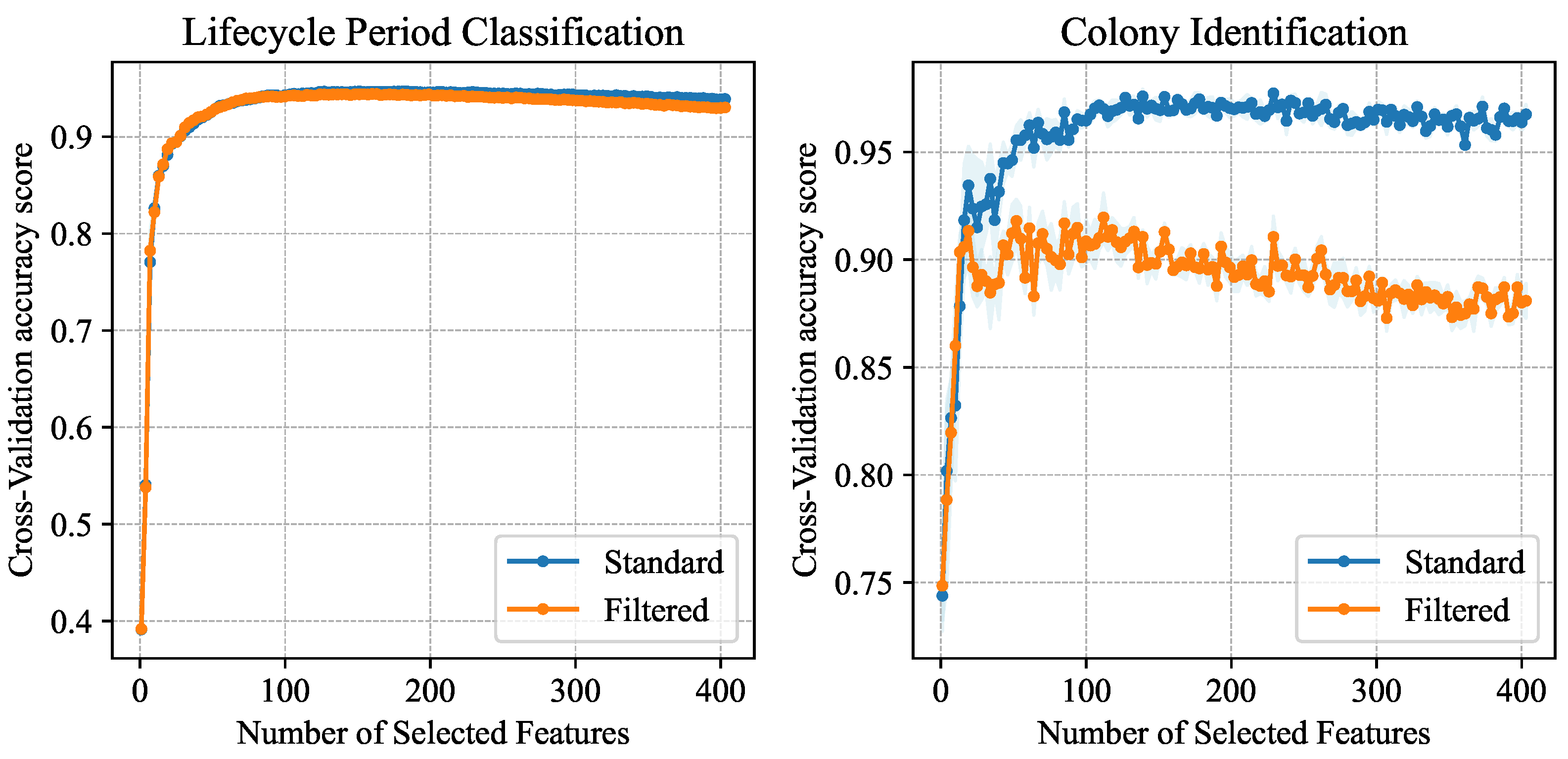

- Performance of lifecycle period identification using convolutional neural networks along with logistic regression and extra trees methods.

- 3.

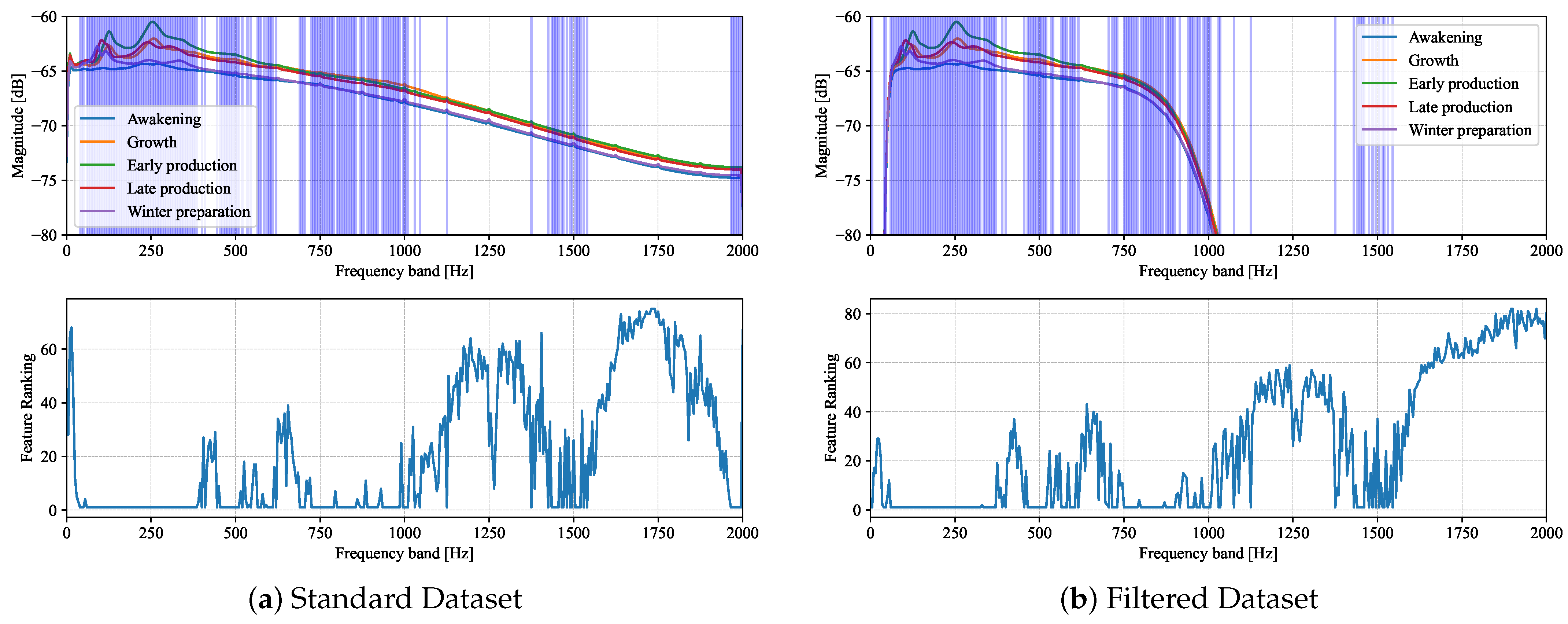

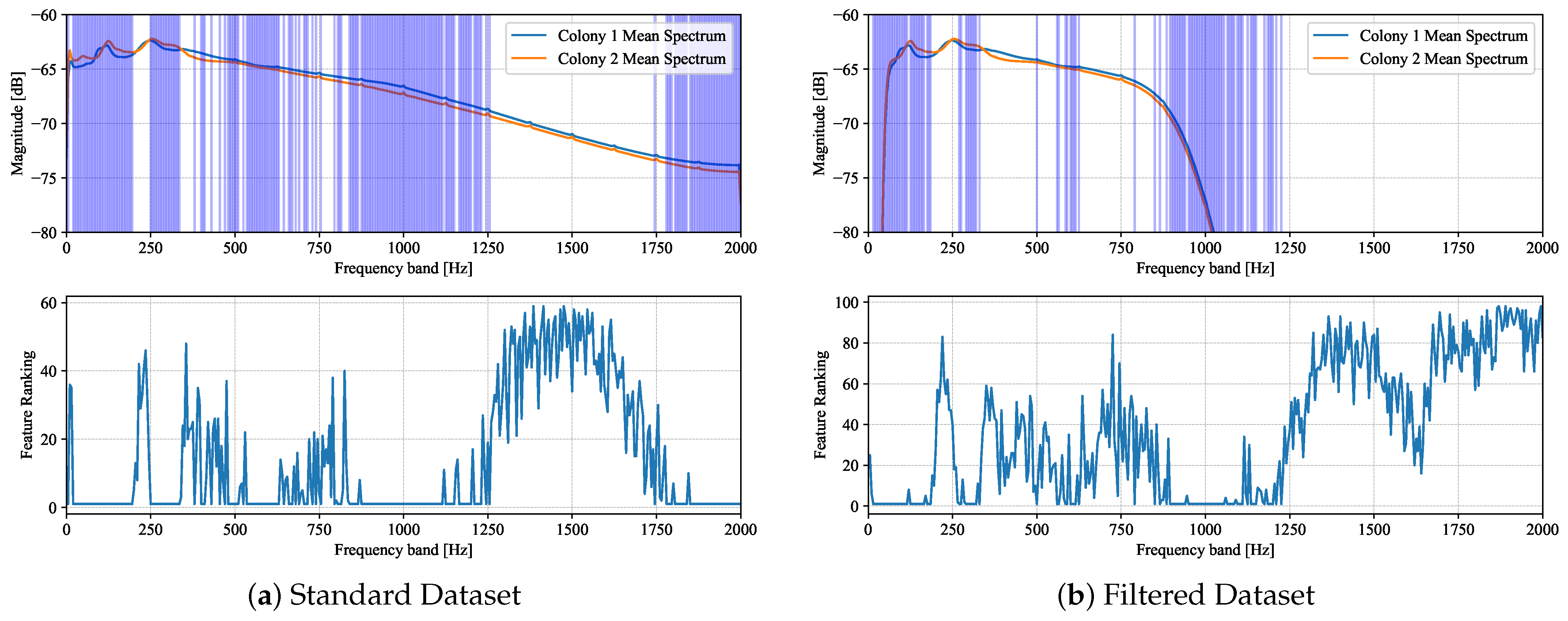

- Feature importance analysis of honey bee-produced vibration for the task of lifecycle period classification and hive identification; verification of the conclusions using a band-filtered dataset.

- 4.

- An analysis of possible difficulties affecting further experiments regarding bee colony identification using vibration signals recorded in beehives.

2. Materials and Methods

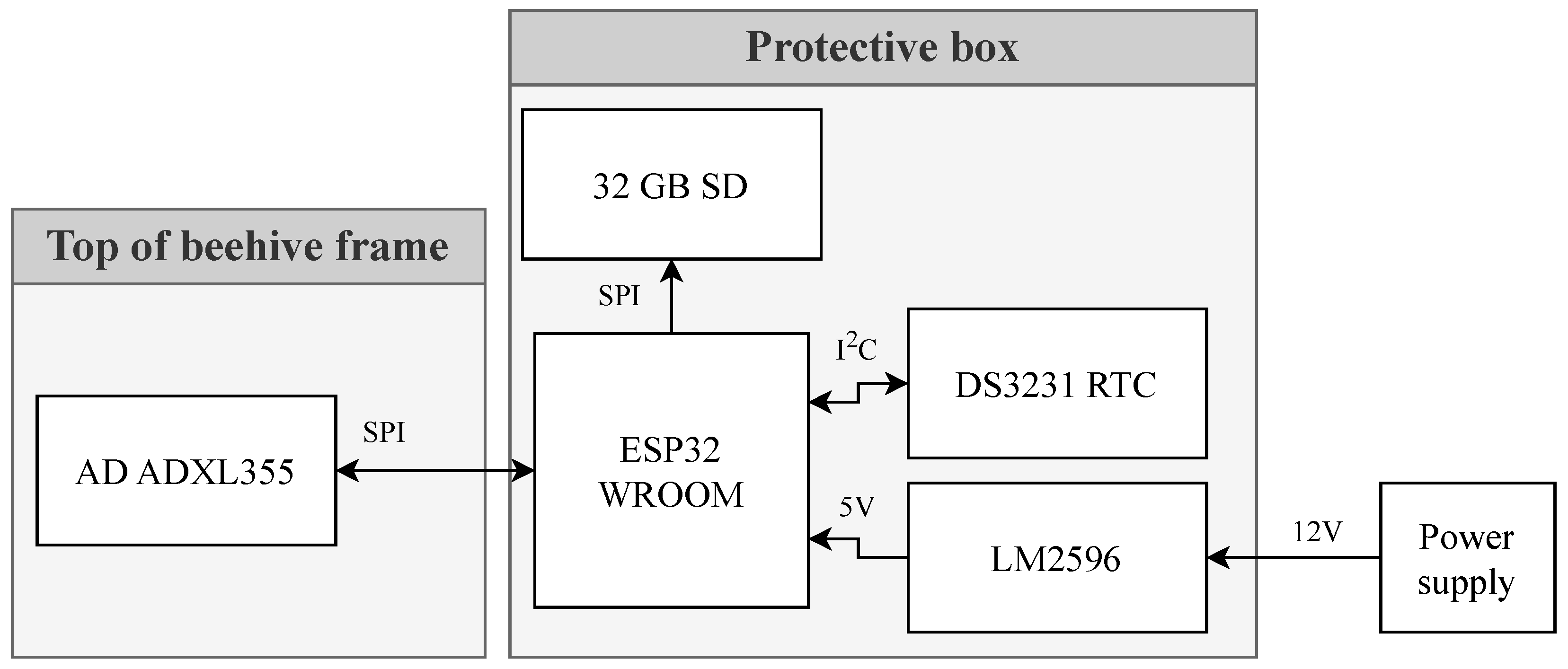

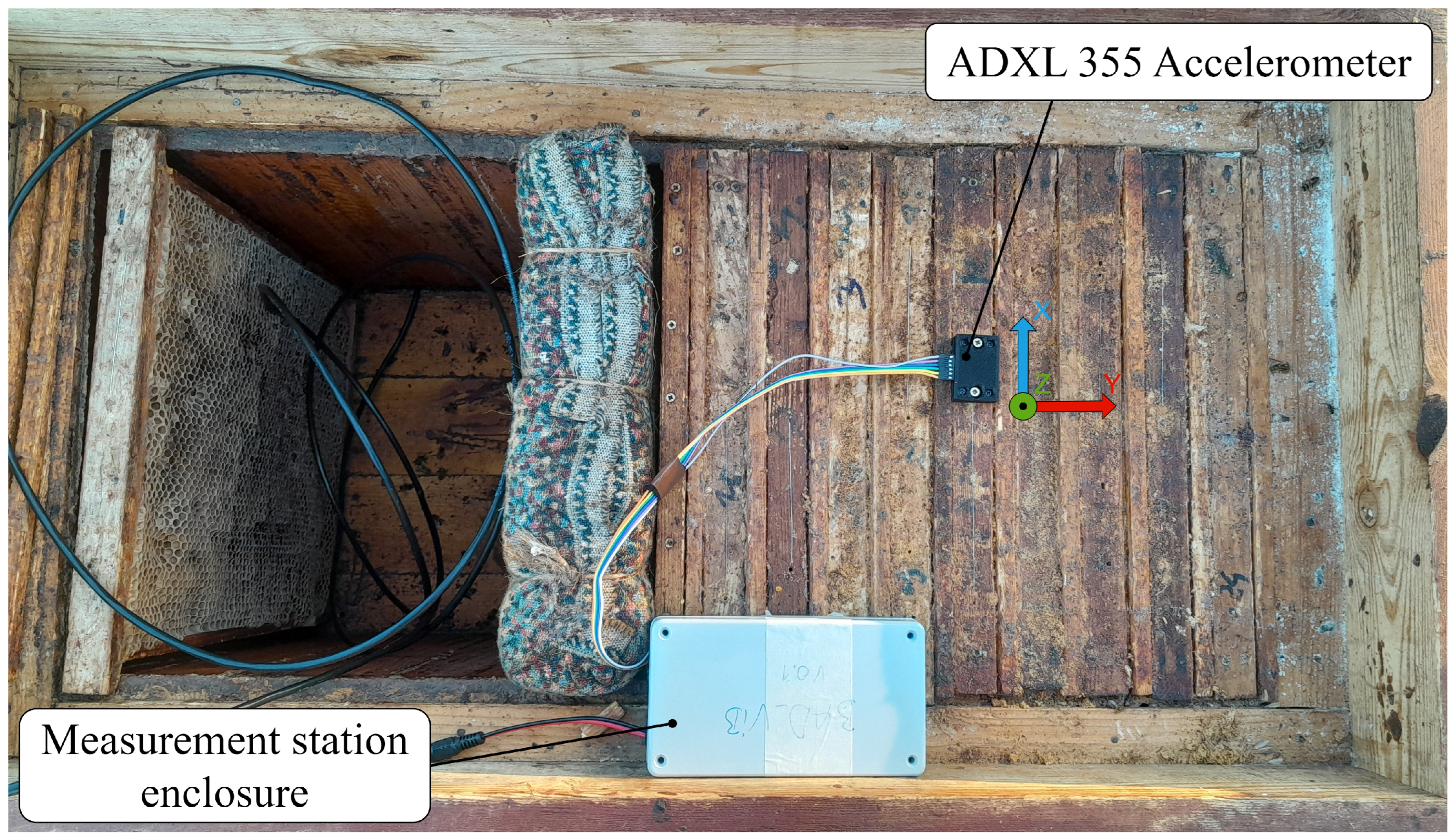

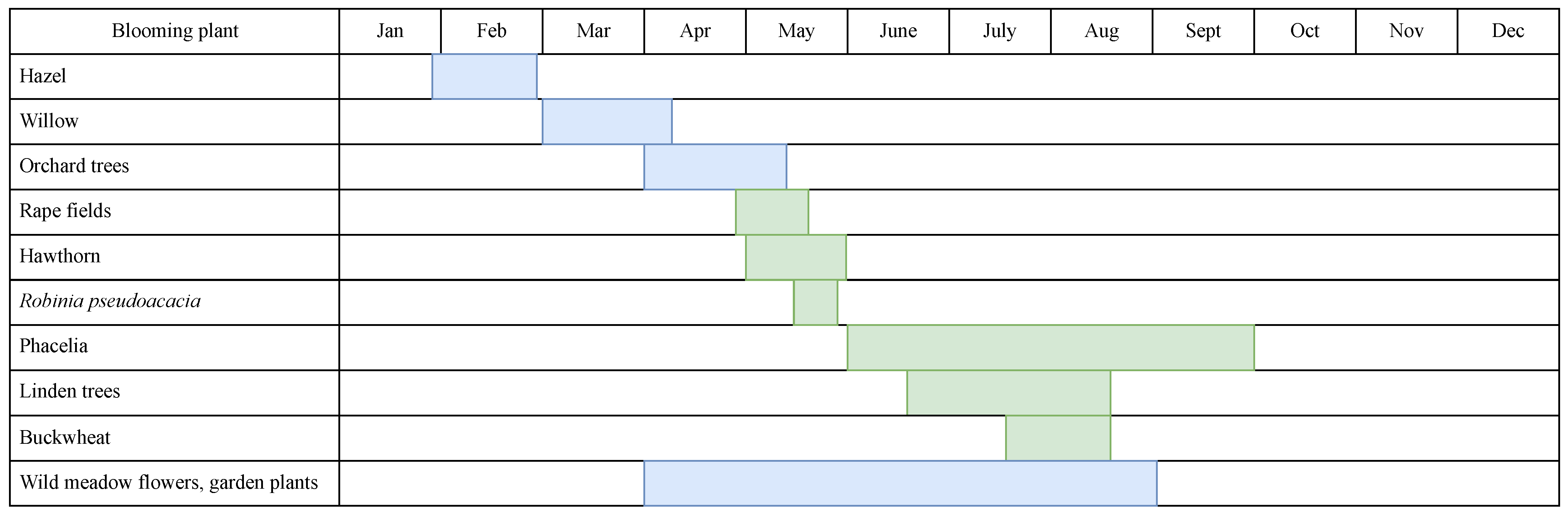

2.1. Measurement Set-Up

2.2. Dataset Preparation

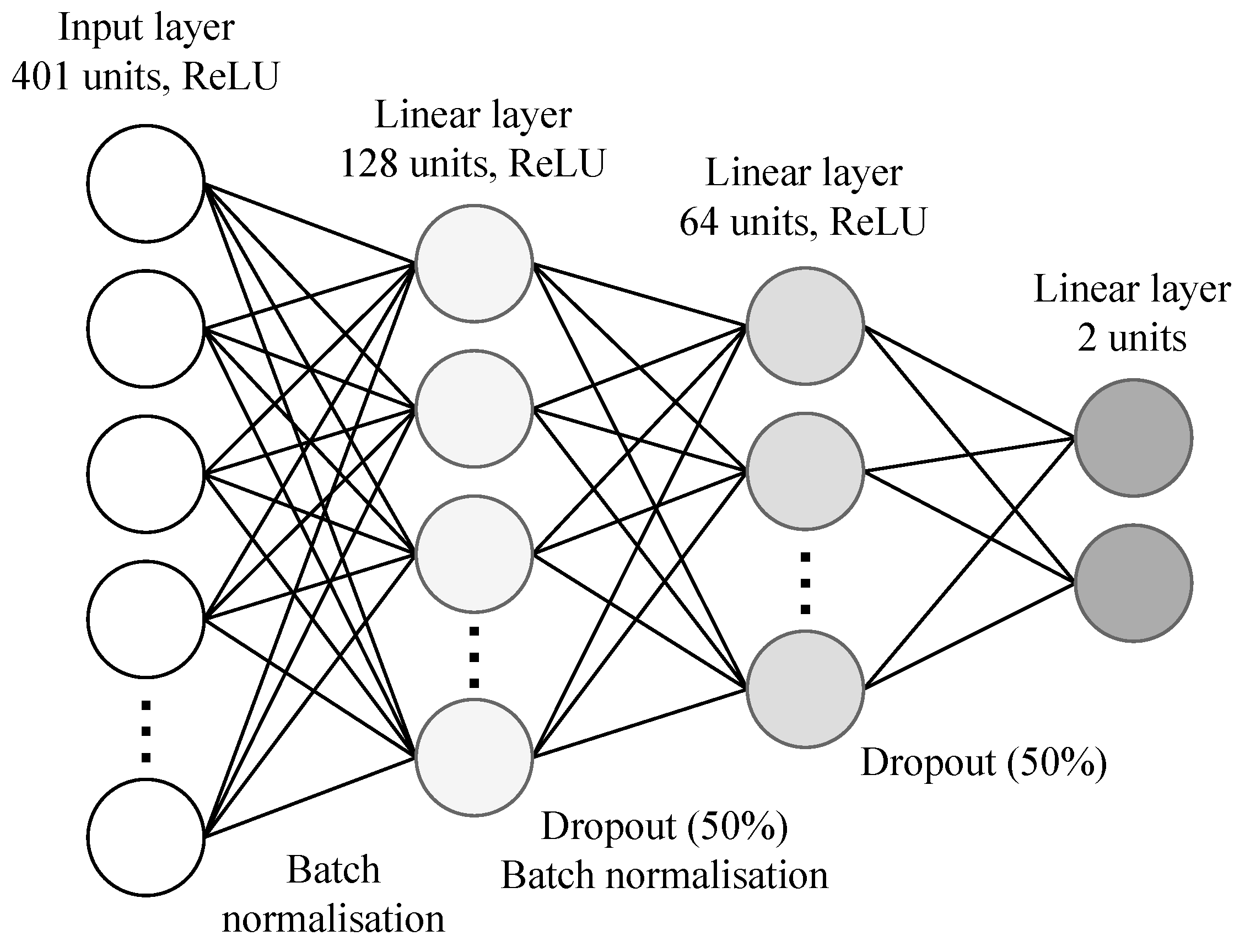

2.3. Classification Algorithms

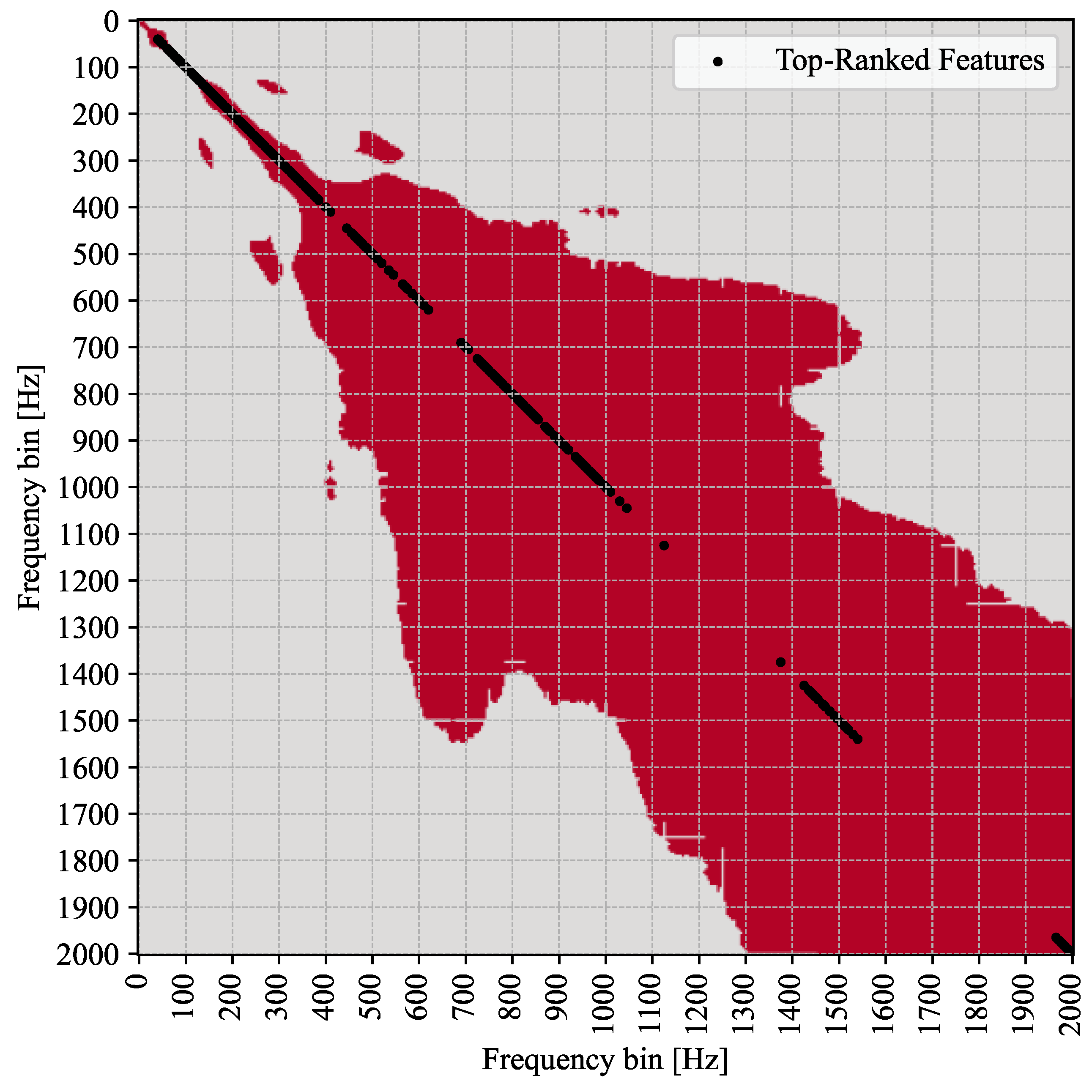

2.4. Feature Importance Investigation

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- 1.

- The dataset used for verification, both in terms of maintenance-caused discontinuities and the low sample size;

- 2.

- Data sourced from only a single bee breed within a single apiary;

- 3.

- Possible label noise introduced by hard limits on classification categorisation;

- 4.

- A single year of measurements, necessitating the use of non-time blocking dataset split techniques, possibly inflating results due to correlations between training and testing data.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| MLP | Multi-Layer Perceptron |

| ET | Extra Trees |

| CV | Cross-Validation |

| RFECV | Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation |

Appendix A

References

- Jeong, K.; Oh, H.; Lee, Y.; Seo, H.; Jo, G.; Jeong, J.; Park, G.; Choi, J.; Seo, Y.D.; Jeong, J.H.; et al. IoT and AI Systems for Enhancing Bee Colony Strength in Precision Beekeeping: A Survey and Future Research Directions. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 362–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczurek, A.; Maciejewska, M.; Batog, P. Monitoring System Enhancing the Potential of Urban Beekeeping. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Diallo, M.A.; van Dooremalen, C.; Schoonman, M.; Williams, J.H.; Van Espen, M.; D’Haese, M.; de Graaf, D.C. European beekeepers’ interest in digital monitoring technology adoption for improved beehive management. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 227, 109556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karmańska, A.; Ziemba, E.W.; Maruszewska, E.W.; Jarka, S. Socio-Demographic Factors Influencing Adoption of Digital Technologies in Beekeeping. J. Apic. Sci. 2025, 69, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turyagyenda, A.; Katumba, A.; Akol, R.; Nsabagwa, M.; Mkiramweni, M.E. IoT and Machine Learning Techniques for Precision Beekeeping: A Review. AI 2025, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dsouza, A.; P, A.; Hegde, S. HiveLink, an IoT based Smart Bee Hive Monitoring System. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.12054. [Google Scholar]

- Meikle, W.G.; Rector, B.G.; Mercadier, G.; Holst, N. Within-day variation in continuous hive weight data as a measure of honey bee colony activity. Apidologie 2008, 39, 694–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjerge, K.; Frigaard, C.E.; Mikkelsen, P.H.; Nielsen, T.H.; Misbih, M.; Kryger, P. A computer vision system to monitor the infestation level of Varroa destructor in a honeybee colony. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 164, 104898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreller, C.; Kirchner, W. Hearing in honeybees: Localization of the auditory sense organ. J. Comp. Physiol. A 1993, 173, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchner, W. Hearing in honeybees: The mechanical response of the bee’s antenna to near field sound. J. Comp. Physiol. A 1994, 175, 261–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michelsen, A.; Kirchner, W.H.; Lindauer, M. Sound and vibrational signals in the dance language of the honeybee, Apis mellifera. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 1986, 18, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrncir, M.; Maia-Silva, C.; Farina, W.M. Honey bee workers generate low-frequency vibrations that are reliable indicators of their activity level. J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sens. Neural Behav. Physiol. 2019, 205, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jankauski, M.A. Measuring the frequency response of the honeybee thorax. Bioinspiration Biomimetics 2020, 15, 046002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, M.; Bencsik, M.; Newton, M.I. Long-term trends in the honeybee whooping signal’ revealed by automated detection. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0181736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, M.T.; Bencsik, M.; Newton, M.; Reyes Carreño, M.; Pioz, M.; Crauser, D.; Simon-Delso, N.; Le Conte, Y. The prediction of swarming in honeybee colonies using vibrational spectra. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsey, M.; Bencsik, M.; Newton, M. Extensive Vibrational Characterisation and Long-Term Monitoring of Honeybee Dorso-Ventral Abdominal Vibration signals. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cejrowski, T.; Szymański, J.; Mora, H.; Gil, D. Detection of the Bee Queen Presence Using Sound Analysis. In Intelligent Information and Database Systems; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Simone, A.; Barbisan, L.; Turvani, G.; Riente, F. Advancing Beekeeping: IoT and TinyML for Queen Bee Monitoring Using Audio Signals. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 2527309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zgank, A. Bee Swarm Activity Acoustic Classification for an IoT-Based Farm Service. Sensors 2020, 20, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, K.; Alabdullah, B.; Al Mudawi, N.; Algarni, A.; Jalal, A.; Park, J. Empirical Analysis of Honeybees Acoustics as Biosensors Signals for Swarm Prediction in Beehives. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 148405–148421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulyukin, V.; Mukherjee, S.; Amlathe, P. Toward Audio Beehive Monitoring: Deep Learning vs. Standard Machine Learning in Classifying Beehive Audio Samples. Appl. Sci. 2018, 8, 1573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Libal, U.; Biernacki, P. Non-Intrusive System for Honeybee Recognition Based on Audio Signals and Maximum Likelihood Classification by Autoencoder. Sensors 2024, 24, 5389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezquida Atauri, D.; Llorente Martínez, J. Platform for bee-hives monitoring based on sound analysis. A perpetual warehouse for swarm’s daily activity. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2009, 7, 824–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uthoff, C.; Homsi, M.N.; von Bergen, M. Acoustic and vibration monitoring of honeybee colonies for beekeeping-relevant aspects of presence of queen bee and swarming. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 205, 107589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šabić, J.; Perković, T.; Šolić, P.; Šerić, L. Buzzing with Intelligence: A Systematic Review of Smart Beehive Technologies. Sensors 2025, 25, 5359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Döke, M.A.; Frazier, M.; Grozinger, C.M. Overwintering honey bees: Biology and management. Curr. Opin. Insect Sci. 2015, 10, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winston, M.L. The Biology of the Honey Bee; Harvard University Press: London, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.; Saifur Rahman, M.; Parvin, N.; Rahman, M. Fundamental Frequency Extraction by Utilizing the Modified Weighted Autocorrelation Function in Noisy Speech. Lect. Notes Netw. Syst. 2024, 890, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, P. The use of fast Fourier transform for the estimation of power spectra: A method based on time averaging over short, modified periodograms. IEEE Trans. Audio Electroacoust. 1967, 15, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ksiazek, P.; Libal, U. Impact of Time of Day on Spectral and Entropic Parameters of Honeybee Audio Signals. In Proceedings of the 2025 Signal Processing Symposium (SPSympo), Warsaw, Poland, 8–10 July 2025; pp. 84–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1412.6980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geurts, P.; Ernst, D.; Wehenkel, L. Extremely Randomized Trees. Mach. Learn. 2006, 63, 3–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, M.; Fraihat, S. Recursive Feature Elimination with Cross-Validation with Decision Tree: Feature Selection Method for Machine Learning-Based Intrusion Detection Systems. J. Sens. Actuator Netw. 2023, 12, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Książek, P.; Libal, U.; Król-Nowak, A. Spectral Components of Honey Bee Sound Signals Recorded Inside and Outside the Beehive: An Explainable Machine Learning Approach to Diurnal Pattern Recognition. Sensors 2025, 25, 4424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amlathe, P. Standard Machine Learning Techniques in Audio Beehive Monitoring: Classification of Audio Samples with Logistic Regression, K-Nearest Neighbor, Random Forest and Support Vector Machine. Master’s Thesis, Utah State University, Logan, UT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Zippenfenig, P. Open-Meteo.com Weather API. 2023. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/14582479 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

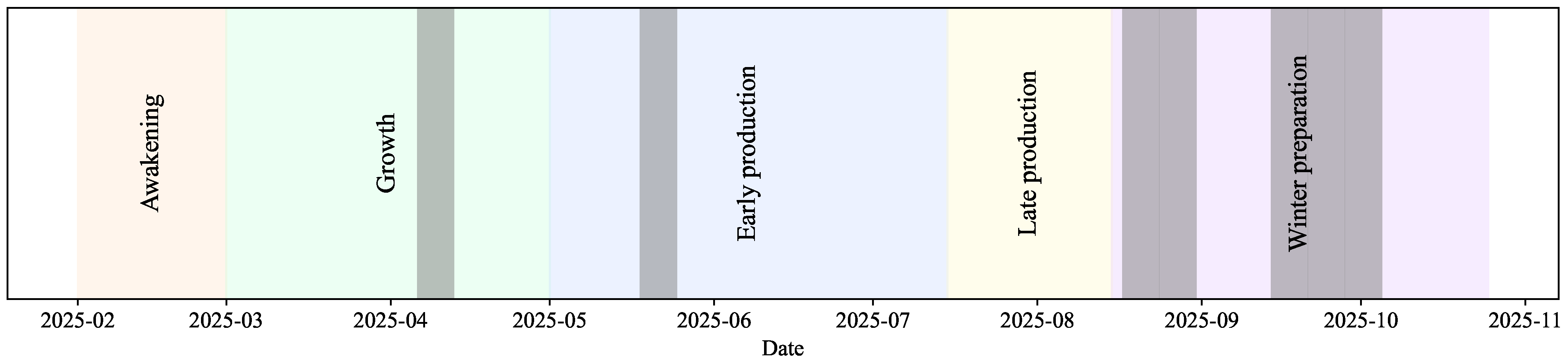

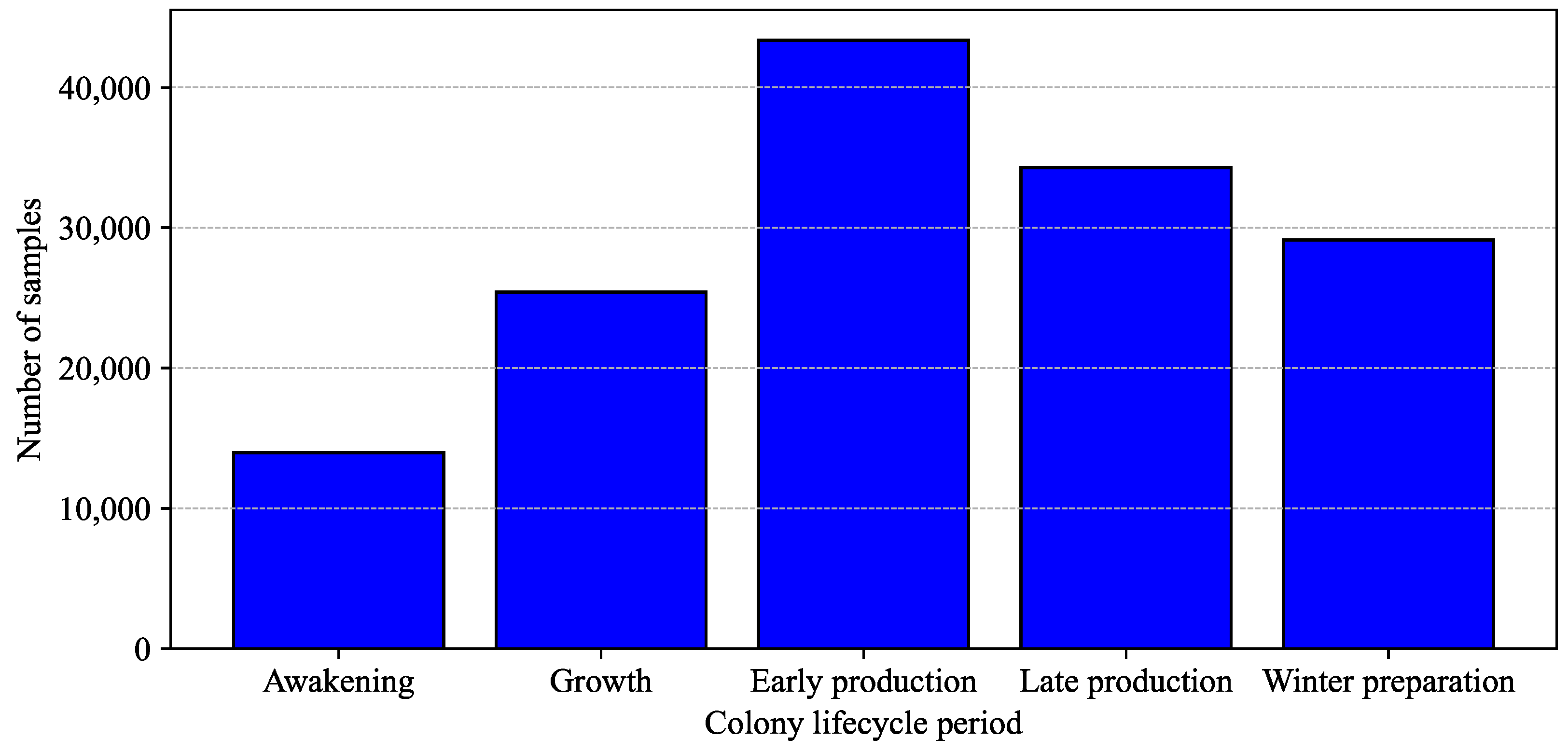

| Class Number | Period Name | Events | Temporal Bounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Awakening | The queen resumes egg laying, the overwintered brood is reared, the spring flight occurs at the end | 01.02–01.03 |

| 1 | Growth | Start of foraging, intensive colony growth, drone rearing occurs. | 01.03–01.05 |

| 2 | Early production | Foraging for early nectar and pollen. Peak drone population. | 01.05–15.07 |

| 3 | Late production | Foraging for later nectar and pollen. | 15.07–15.08 |

| 4 | Winter preparation | Late blooming forage. Sugar syrup feeding and Varroa treatments are performed. | 15.08–25.10 |

| Task | Dataset Variant | Mean Accuracy | Std Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lifecycle period classification | Standard | 85.6% | 0.2% |

| Filtered | 82.9% | 0.2% | |

| Colony identification | Standard | 97.8% | 0.1% |

| Filtered | 97.2% | 0.1% |

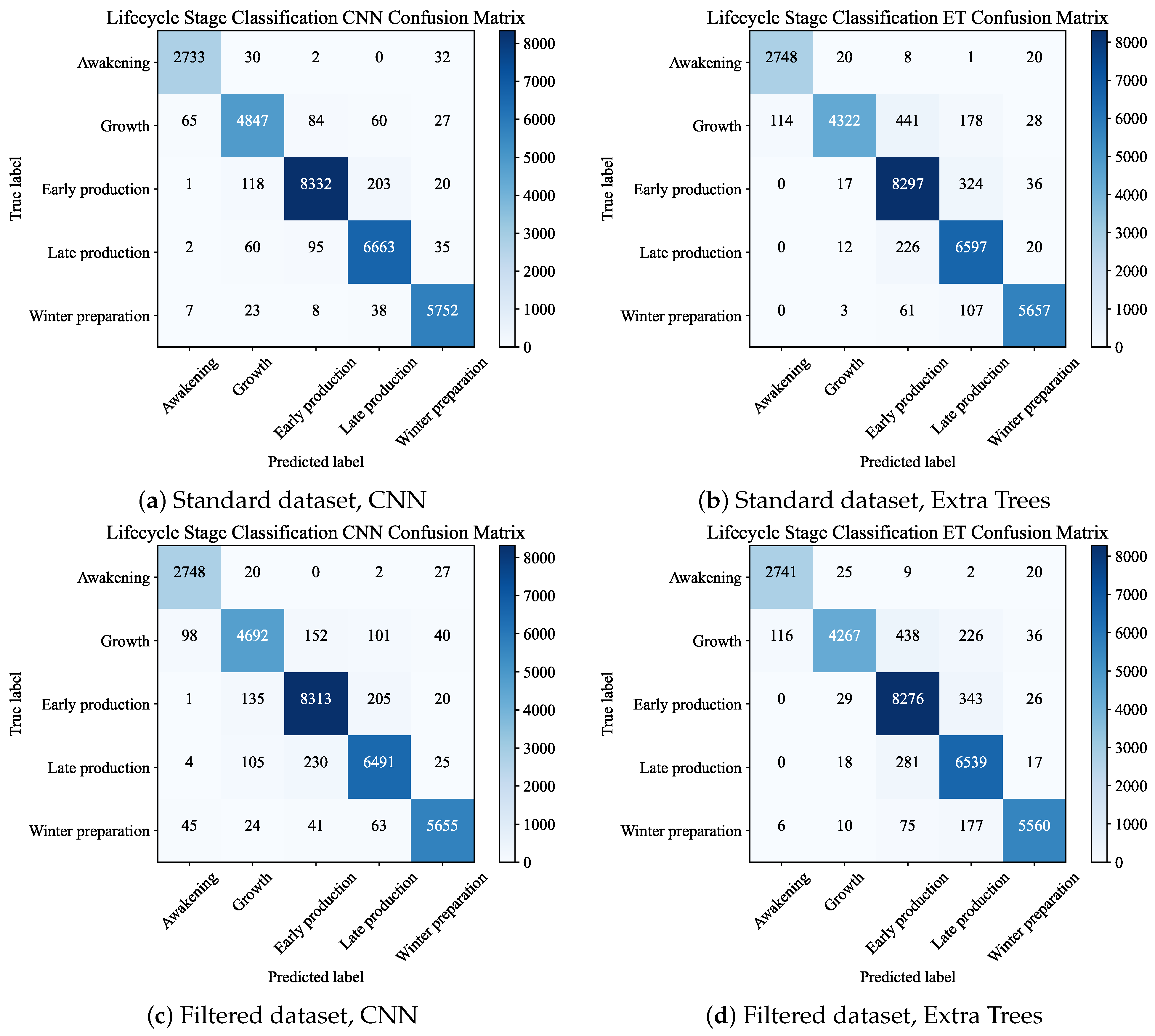

| Model | Dataset Variant | Mean Accuracy | Std Accuracy | F1 Score | Std F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNN | Standard | 96.7% | 0.4% | 96.5% | 0.3% |

| Filtered | 95.9% | 0.5% | 95.7% | 0.5% | |

| ET | Standard | 94.2% | 0.2% | 94.1% | 0.2% |

| Filtered | 93.4% | 0.2% | 93.3% | 0.2% |

| Standard Dataset | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lifecycle Period | CNN | ET | ||

| Mean Accuracy | Std Accuracy | Mean Accuracy | Std Accuracy | |

| Awakening | 98.6% | 0.5% | 98.3% | 0.3% |

| Growth | 94.0% | 0.8% | 84.3% | 0.6% |

| Early production | 95.8% | 0.5% | 95.3% | 0.3% |

| Late production | 97.3% | 0.6% | 96.2% | 0.2% |

| Winter preparation | 97.9% | 0.6% | 96.8% | 0.2% |

| Filtered Dataset | ||||

| Awakening | 98.2% | 0.3% | 98.1% | 0.3% |

| Growth | 93.2% | 1.1% | 83.0% | 0.5% |

| Early production | 95.3% | 0.7% | 94.9% | 0.3% |

| Late production | 95.6% | 0.9% | 95.6% | 0.3% |

| Winter preparation | 97.3% | 0.8% | 95.1% | 0.3% |

| Model | Dataset Variant | Mean Accuracy | Std Accuracy | F1 Score | Std F1 Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLP | Standard | 99.8% | 0.0% | 99.8% | 0.0% |

| Filtered | 99.6% | 0.1% | 99.6% | 0.1% | |

| ET | Standard | 95.9% | 0.6% | 95.8% | 0.6% |

| Filtered | 86.7% | 0.6% | 86.3% | 0.7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Książek, P.; Szlachetko, B.; Roman, A. Honey Bee Lifecycle Activity Prediction Using Non-Invasive Vibration Monitoring. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010188

Książek P, Szlachetko B, Roman A. Honey Bee Lifecycle Activity Prediction Using Non-Invasive Vibration Monitoring. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):188. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010188

Chicago/Turabian StyleKsiążek, Piotr, Bogusław Szlachetko, and Adam Roman. 2026. "Honey Bee Lifecycle Activity Prediction Using Non-Invasive Vibration Monitoring" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010188

APA StyleKsiążek, P., Szlachetko, B., & Roman, A. (2026). Honey Bee Lifecycle Activity Prediction Using Non-Invasive Vibration Monitoring. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010188