1. Introduction

The skin is the barrier between the internal and external environment and is the largest organ of the human body, playing a role in both protecting the interior from the environment and in thermoregulation and sensory perception. Being in direct contact with the outside, it is prone to various traumas or diseases [

1,

2,

3].

Skin regeneration is an essential field of regenerative medicine, having a significant impact on the treatment of wounds, burns and chronic dermatological conditions [

4,

5]. The skin’s ability to repair itself is limited in the case of severe injuries, which requires the development of innovative solutions to accelerate the healing process. Tissue engineering is a modern approach that uses advanced biomaterials, cells and biochemical factors to recreate the structure and functionality of damaged skin [

6]. One of the biggest obstacles in this field is the creation of an environment that supports fundamental homeostatic mechanisms [

7]. The success of tissue regeneration depends on optimizing cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, apoptosis and angiogenesis, as well as on providing adequate stromal support and necessary signals [

8].

Currently, autologous skin grafting is the standard technique used for wound coverage, but it is limited by the availability of autologous tissue. Although plastic surgery has a variety of techniques for tissue transfer, these interventions cannot be considered solutions for true tissue regeneration or complete replacement [

8].

For deep dermal wounds, which cannot regenerate the epidermis due to the lack of keratinocytes, autografting is recommended. Since the autograft comes from the patient’s own tissue, there is no risk of rejection [

9].

To overcome the limitations related to the availability of tissues for autologous grafts, the use of allografts can be resorted to. Cadavers represent an important source of allografts, which are kept frozen in skin banks and can be used when needed [

10]. These grafts are widely used in the treatment of burns, and the application of an allograft skin graft allows the formation of granulation tissue and the contraction of the wound [

11]. However, allografts are eventually rejected by the host immune system and may pose a risk of viral transmission, such as hepatitis B and C or HIV [

11]. Although they provide temporary protection, they promote angiogenesis and provide growth factors and cytokines necessary for wound healing [

12].

Xenografts are grafts obtained from different species and animal skin is used to cover human wounds. These grafts are used as temporary solutions because the exogenous collagen integrates into the human wound and helps regenerate the dermis [

13]. As the wound heals, the xenografts are absorbed. The most used xenografts are derived from porcine skin and are frequently used in burn care [

12].

To avoid the limitations of the mentioned techniques, numerous types of biomaterials, both synthetic and natural origin, which have the property of biodegradability, are being studied for different types of applications, such as supports for tissue engineering and wound healing [

14]. These biomaterials include polymeric biocomposites, nanobiocomposites, hydrogels, etc. It has been reported that biopolymers are considered a remarkable candidate material for tissue engineering, medical devices for implants, wound healing, due to their suitable biochemical and biophysical properties in both in vivo and in vitro applications [

15].

In recent years, developments in advanced wound dressings have led to the integration of innovative materials and biological compounds that not only protect the wound, but also stimulate essential healing processes, such as cell migration and the production of extracellular matrix components [

16]. Modern therapies also include tissue-derived or cell-cultured skin substitutes, offering promising solutions for the regeneration of damaged skin [

17]. In this context, the development of effective wound treatment strategies remains a major area of interest in biomedical research [

18]. It is known that moist wound dressings promote a faster rate of wound healing compared to dry wound dressings [

19]. Studies on dermal wound healing have considered the proliferation rates of the cellular entities involved in this process [

20]. Comparison of the effects of wet and dry conditions on populations of both cell types shows that inflammatory phase cells fail to proliferate rapidly in a wet environment, but endothelial cells and fibroblasts increase in wet wound conditions compared to wounds maintained in a dry environment [

21].

Recently, wound dressings have been modernized, being mainly made of synthetic polymers [

19], such as poly(α-hydroxy acids), such as polylactic acid (PLA), polyglycolic acid (PGA), polyacrylate, and various copolymers, such as poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL), poly(lactic-co-glycolic) (PLGA), polypropylene fumarate, polyorthoesters, polycarbonates, and polyanhydrides [

22,

23]. The polyesters PLA and PGA have attracted attention due to their extensive use in biodegradable implants and tissue engineering [

24].

These dressings can be divided into two categories: passive and interactive. Passive dressings are non-occlusive, used to cover wounds and support skin function, examples being gauze and tulle. Interactive dressings are occlusive or semi-occlusive, providing a barrier against bacteria and can take various forms, such as films, foams, hydrogels or hydrocolloids [

19].

Hydrogels are represented by hydrophilic polymers, such as polyvinylpyrrolidone, polyacrylamide and polyethylene oxide [

24]. They are not soluble in water and have innate characteristics of swelling in contact with water, having a porous and hydrophilic structure that allows the exchange of fluids and gases to take place under favorable conditions, thus regulating water evaporation and exudate absorption, as well as maintaining moisture in the wound area [

25]. Hydrogels also mimic the structure and functionality of the extracellular matrix, supporting the attachment and proliferation of cells and directing their orientation [

26].

Several biopolymers have been used in the preparation of hydrogels, including cellulose, chitosan, pectin, glycosaminoglycans, alginate, collagen, fibrin, dextran, elastin and others [

27]. Collagen is extensively studied and crucial protein for skin regeneration, playing a fundamental role in maintaining the skin’s structure, strength, and elasticity [

28,

29]. It is the primary structural component of the dermis and is essential for the wound healing process [

30]. It is secreted by fibroblasts, being a common structural protein that stimulates cell migration, as it has the property of chemotaxis that attracts fibroblasts and facilitates the deposition of new tissue during wound healing [

31]. Pectin is a widely studied polysaccharide in the field of biomaterials due to its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and low toxicity [

32]. Numerous research papers explore its applications in drug delivery, tissue engineering, and wound healing, often as hydrogels, films, or composites [

33,

34,

35]. Alginate, a natural polysaccharide derived from brown seaweed, is extensively researched as a versatile biomaterial due to its biocompatibility, biodegradability, and ease of gelation into hydrogels [

36,

37]. Research papers highlight its use in tissue engineering, drug delivery, and wound healing.

Myrtus communis (Myrtle) essential oil is actively researched in the field of biomaterials, primarily for its potent antimicrobial and antioxidant properties [

38,

39]. It is often incorporated into biopolymer matrices, such as encapsulated in polysaccharides, to create functional hydrogels with applications in medicine, and tissue engineering [

40,

41,

42]. Most hydrogels require an additional layer to fix them to the skin because they do not adhere naturally. Hydrogels used as dressings are available in the form of elastic films or amorphous gels [

19]. They are versatile in creating a delivery structure and can be impregnated with various active substances [

43]. Thus, these hydrogel-based dressings are used for moderately to heavily exuding wounds, partial or full thickness wounds with drainage and infected wounds, but they are contraindicated for dry or minimally draining wounds or wounds covered with bedsores, arterial ulcers and exposed to deeper structures [

44].

The main aim of this work is to develop and comprehensively characterize an innovative hydrogel system, based on natural biopolymers—pectin, collagen and alginate—in combination with Myrtus communis essential oil, intended for applications in the field of skin regeneration. This study introduces a novel, fully natural hydrogel system formed from a synergistic blend of pectin, collagen, and alginate, further enhanced with Myrtle essential oil differentiates this system from conventional synthetic wound-care materials. This idea is based on the need to develop biocompatible, bioactive and functional materials that support the skin healing process by mimicking the structure of the extracellular matrix and providing favorable conditions for tissue regeneration. The choice of hydrogel components was based on their well-known properties: collagen as a major structural protein of the skin, pectin for its gelling capacity and interaction with cations, alginate for gel stability and pseudoplastic behavior and myrtle essential oil for its antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory potential.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Preparations of the New Hydrogels

The first part of the experiments was dedicated to the formulation of the hydrogel composition, by establishing the optimal proportions between the polymers, in order to obtain a homogeneous, stable and adapted hydrogel network for cutaneous application. Particular attention was paid to the integration of myrtle essential oil into hydrogel composition without compromising the physicochemical structure of the system. A pH compatible with the skin was targeted, to prevent collagen degradation or instability of other components, the pH was adjusted to 7. Subsequently, the obtained systems were characterized by a series of physicochemical and structural methods, including FTIR spectroscopy analysis to identify interactions between components, micro-computed tomography to evaluate internal morphology and porosity, biological tests, etc.

For the formulation of the hydrogel, natural polymers and analytical grade chemical reagents were used, provided by Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Citrus peel pectin (galacturonic acid ≥ 74%, methoxylation degree of 6.7%, Sigma-Aldrich), was used as powder form. Type I collagen from bovine with a purity of >90% and an average molecular weight of approximately 300,000 Da was provided by the INCDTP-ICPI Institute, Collagen Department. Sodium alginate (viscosity between 15–25 cP at 1% solution, Sigma-Aldrich), extracted from brown algae, was also used in lyophilized powder form. The Myrtus communis L. (myrtle) samples employed in this study were collected from their natural habitat in the Amanos Mountains during the flowering period. The studies showed that the essential oil content of fresh leaves was 0.70–0.75%. Myrtle essential oil was provided by Hatay Mustafa Kemal University, Turkey. It was obtained from fresh leaves through hydrodistillation employing a Neo-Clevenger apparatus.

Ionic crosslinking was performed with anhydrous calcium chloride (CaCl2, ≥93% purity and molecular weight 110.98 g/mol, Sigma-Aldrich). Additional stabilization of the hydrogel network was achieved by chemical crosslinking using glutaraldehyde (25% aqueous solution with molecular weight 100.12 g/mol, Sigma-Aldrich). pH adjustment was performed using NaOH (molecular weight 40.00 g/mol, Sigma-Aldrich) and HCl (molecular weight 36.46 g/mol, Sigma-Aldrich), both of reactive grade. For all experimental steps requiring ultrapure water, a TRITON 12 purification system (Neptec GmbH, Elbtal, Germany, specific resistance up to 18.2 MΩ·cm, total organic carbon (TOC) content ≤ 2 ppb, 10 L tank, silent recirculation pump and integrated microfiltration unit to prevent bacterial contamination) was used.

Hydrogels based on alginate, pectin, collagen and

Myrtus communis essential oil were obtained through a process involving homogenization, crosslinking and lyophilization steps. For each sample, mixtures of the three natural polymers were prepared in constant proportions: 1% alginate, 1% pectin and 1.5% collagen for samples 1–3 and 1% collagen for samples 4–6, respectively (

Table 1). The pectin and alginate solutions were obtained under magnetic stirring at 50 °C, for 20 min, in a water bath. After cooling, the predetermined amount of collagen gel obtained by solubilization in water was added, the polymer mixture being homogenized manually, using a spatula. The pH was adjusted to 7 with 5 M NaOH or 1 M HCl solutions, to avoid collagen precipitation, near its isoelectric pH.

Separately, the appropriate volume of myrtle essential oil was solubilized in ethanol and gradually added to the polymer mixture, in concentrations of 0.1% (samples 2 and 5) or 0.2% (samples 3 and 6). For samples 1 and 4, no oil was added. After complete dispersion of the oil, glutaraldehyde solution (0.025%) was added as a chemical crosslinking agent, mixing gently to prevent air bubbles and ensure uniform crosslinking.

Then, the samples were frozen at −30 °C for one and a half hours and subsequently lyophilized for 48 h. A Martin Christ Alpha 2-4 LSCbasic lyophilizer, Osterode am Harz, Germany, was used to perform the lyophilization.

The dried structures were then immersed in a 2% CaCl2 solution for ionic crosslinking of the alginate, for 30 min, followed by a washing step with distilled water to remove excess ions. Finally, the samples were lyophilized again to obtain the final porous hydrogels, which were prepared for morphological, physicochemical and biological characterizations.

2.2. Characterization Methods

Hydrogels characterization is essential for understanding the structural, physicochemical and biological behavior of these materials, especially when they are intended for biomedical applications, such as skin regeneration. Hydrogels are three-dimensional polymeric systems capable of absorbing large amounts of water or biological fluids, and their properties depend directly on the chemical composition, degree of crosslinking, porosity and internal structure. Therefore, rigorous characterization allows the optimization of hydrogel and its performance in clinical applications.

To evaluate the applicability of hydrogels in a biomedical context, it is essential to use characterization methods that provide information about the structure, stability and functionality of these materials.

2.2.1. Swelling Degree and Stability Tests

Among these methods, swelling and stability tests are of particular importance, as they provide critical information on the hydrogel’s ability to absorb biological fluids, which directly influences its behavior upon possible contact with the wound. The degree of swelling reflects the density of the polymer network, hydrophobic/hydrophilic interactions and the material’s ability to maintain a moist environment, essential for wound healing. The stability of hydrogel over time and under conditions simulating the physiological environment, indicates its potential to remain functional during the tissue regeneration process. The swelling and stability tests were performed using the same methods as in our previous research works [

45,

46].

2.2.2. Gas Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (GC–MS)

The Myrtle essential oil was analyzed by using 8890GC System Agilent gas chromatograph equipped with a 5977C GC/MSD mass spectrometer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA), HP-5MS inert column (30 m × 0.25 mm ID × 0.25 μm film), the carrier gas used was helium with a flow of 1 mL min−1, and with the following settled parameters: 50 °C degree, 3 °C/min ramp to 220 °C.

2.2.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR)

FTIR was used to confirm the presence and interaction of chemical components in the hydrogel network. By analyzing the characteristic bands of functional groups (e.g., -OH, -COO−, -NH), the formation of new bonds (hydrogen bonds, crosslinking reactions) or possible structural changes of the polymers following essential oil functionalization or crosslinking, can be detected. The FTIR spectra of the obtained biomaterials were recorded using a Bruker FTIR spectrometer (Bruker, Billerica, MA, USA), Vertex 70. The FTIR spectrum was recorded in ATR–FTIR mode with the following parameters: spectral region 4000–600 cm−1, resolution 4 cm−1 and 32 acquisitions for each sample.

2.2.4. Micro-CT (Micro-Computed Tomography)

Micro-CT provides a detailed three-dimensional image of the internal structure of the hydrogel. This method can assess porosity, pore distribution and interconnectivity, characteristics that influence the diffusion of nutrients, oxygen and cells, being essential for the efficiency of the material in tissue regeneration. This analysis was possible using the high-resolution Bruker SkyScan µCT 1272 equipment. For the morpho structural characterization of the 3D printed scaffolds, the freeze-dried samples were placed on the scanning stage and fixed with dental wax. Scanning was performed at room temperature by rotating the object in front of the source (voltage 50 kV, current 130 µA) at 180 degrees with a rotation step of 0.2 degrees, each frame resulting from the averaging of 3 projections per frame (300 ms/frame). The scanning resolution (image pixel size) was set to 12 µm for all samples. Data were reconstructed in Bruker NRecon 1.7.1.6 software (Kontich, Belgium), analyzed in Bruker CTAn 1.17.7.2 software (Kontich, Belgium) and rendered in Bruker CTVox 3.3.0.0 (Kontich, Belgium).

2.2.5. Antimicrobial Activity

Antibacterial tests are essential in evaluating the ability of hydrogel to prevent infections at the application site. In the case of hydrogels functionalized with myrtle essential oil, microbiological tests (disk-diffusion type) allow determining the efficacy against common pathogenic bacteria, such as

Staphylococcus aureus or

Escherichia coli and justify the therapeutic potential without the addition of classical antibiotics. The antibacterial effect of the obtained samples was evaluated using the method described in our previous research work [

47].

2.2.6. Biocompatibility Tests

In vitro cellular assessments, such as the XTT assay or cytotoxicity tests, such as LDH-release, are essential for evaluating the biocompatibility of the hydrogels. They show whether the material supports the viability, proliferation and functional behavior of fibroblast cells, critical parameters for the integration of the material into living tissue and the stimulation of regeneration processes. The biocompatibility of the materials was tested on a human fibroblast cell line stimulated with epidermal growth factor (EGF-1), cultured in Fibroblast culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% antibiotic-antimycotic (Penicillin/Streptomycin). For testing, the cells were seeded in a 24-well plate, at a density of 1.5 × 104 cells/well, in 500 μL of culture medium, and incubated at 37 °C, in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2, for 24 h, in the presence of the investigated samples. Cell viability was assessed using the XTT assay, a colorimetric method for quantifying metabolically active cells. The reaction is based on the reduction of the compound XTT–2,3-bis(2-methoxy-4-nitro-5-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium-5-carboxanilide–by mitochondrial enzymes of viable cells in the presence of an intermediate cofactor (phenazine methosulfate, PMS), resulting in a colored product (formazan) soluble in aqueous medium.

To perform the assay, the residual culture medium was removed, and the cell surface was washed with PBS (Phosphate-Buffered Saline) to remove fetal bovine serum, which could interfere with the reaction. 250 µL of XTT solution was added to each well, the final concentration of XTT solution being 0.3 mg/mL. The hydrogels were sterilized by UV exposure for 30 min on each side, cut into aseptic 6 mm discs, and directly placed in contact with the cells in 24-well plates. The samples were incubated for 24 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2. At the end of the incubation, the obtained solution, orange-brown, depending on the intensity of the reaction, was transferred to a 96-well plate and read with a Tecan spectrophotometer at 540 nm. The absorption intensity is directly proportional to the number of viable cells present in the sample.

Cytotoxic effects of the samples were evaluated using the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release assay (Roche LDH kit, Sigma-Aldrich), which measures the extracellular activity of LDH, a normally intracellular enzyme that is liberated upon plasma membrane disruption. After treatment, the microplates were incubated for 30 min at 37 °C under 5% CO2. The enzymatic reaction generated a red chromogenic product proportional to the amount of LDH released. Absorbance was measured at 490 nm with background correction at 600 nm using the same microplate spectrophotometer. The use of these methods can provide a thorough characterization, which can validate the use of these biomaterials in skin regeneration applications.

2.2.7. Statistical Assessment

The statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism 9 (San Diego, CA, USA). The level of significance was set to p < 0.05. All data were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (n = 3). The significant impact of the effect of swelling degree was statistically analyzed through 2way ANOVA and Holm–Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. The antimicrobial activity was evaluated by using one-way ANOVA and Tukey’s multiple comparisons test. The stability data were statistically analyzed using one-way ANOVA and Holm–Šídák’s multiple comparisons test. Data for in vitro cellular assessments were analyzed using the Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. GC–MS

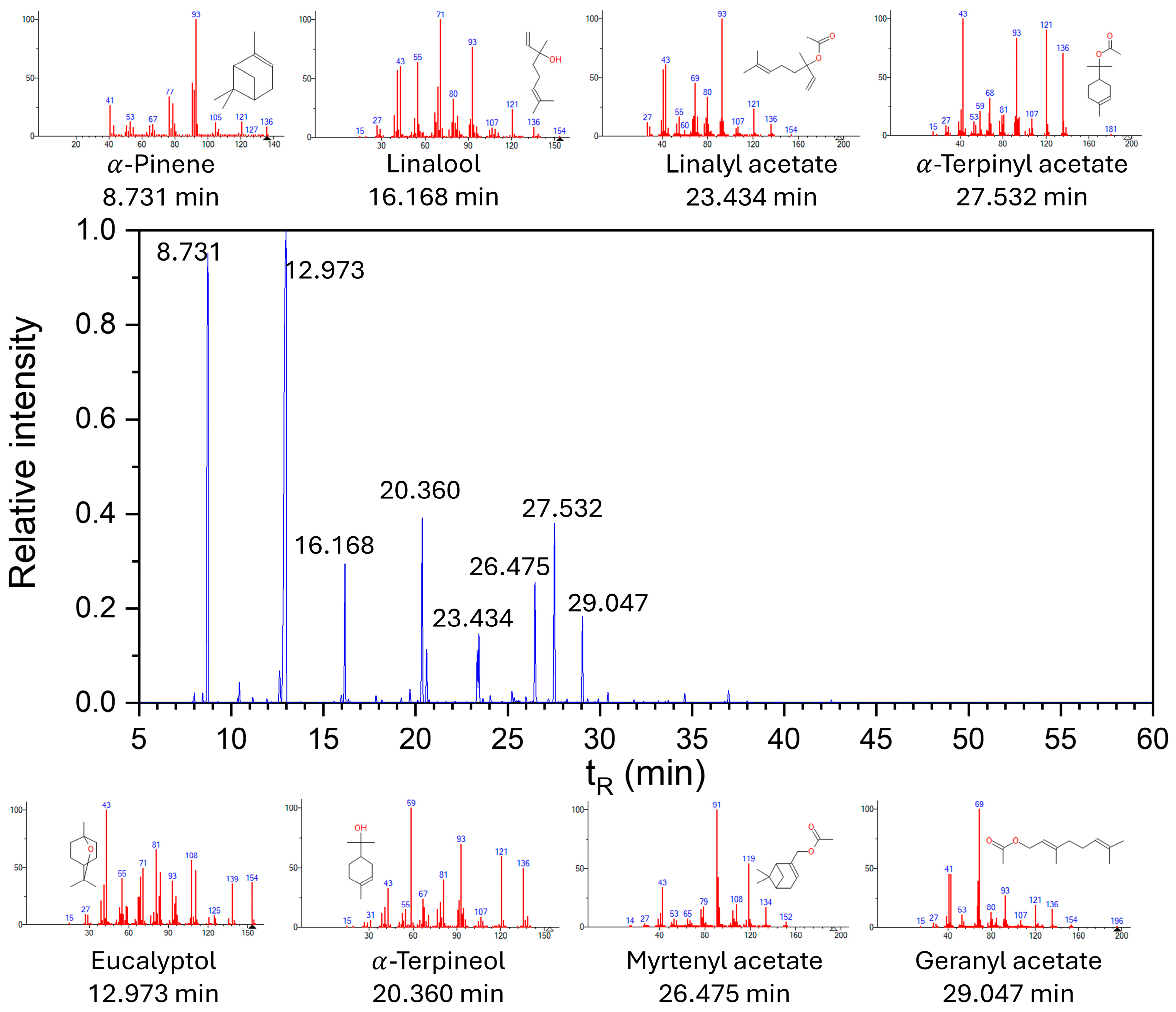

The chemical composition of the

Myrtus communis essential oil was characterized using GC–MS (

Figure 1). The resulting chromatogram revealed a complex profile of volatile constituents, with several compounds detected as major peaks.

These findings provide insight into the key aromatic and bioactive components present in the oil [

48]. The main components of the essential oil used in the study were determined to be eucalyptol (42%), followed by α-pinene (21%), α-terpineol (8%), and linalool (5%).

3.2. Micro-CT

Micro-CT analysis allowed a detailed evaluation of the internal structure of the obtained freeze-dried hydrogels, highlighting the influence of the composition on porosity, pore size, wall thickness and specific surface area.

The analyzed samples, shown in

Figure 2, varied in terms of collagen concentration (1.5% in samples J1–J3 and 1% in J4–J6) and myrtle essential oil (0%, 0.1% and 0.2%), in order to observe how these components influence the material porous architecture.

Table 2 summarizes key morphological features, measured for the synthesized materials, that are further discussed.

Samples with higher collagen concentration generally showed slightly lower porosities, which can be explained by the formation of a more compact polymer network. Sample J1, which does not contain essential oil, recorded a porosity of 76.67% and an average pore diameter of 116.87 μm, indicating a balanced network, ideal for cell migration and nutrient transport. The addition of 0.1% myrtle oil (J2) led to a slight decrease in porosity (74.53%) and pore size (84.70 μm). These changes can be attributed to interactions between the essential oil and the collagen network, which could disrupt uniform gel formation.

At 0.2% oil (J3), a sharp decrease in porosity (67.95%) and pore diameter (95.18 μm) is observed, suggesting a much more rigid network, an effect that can be associated with the presence of essential oil, which seems to densify the internal structure of the hydrogel at increasing concentrations. In the case of samples with 1% collagen (J4–J6), the overall porosity is higher. Sample J4, without essential oil, presented a significantly higher porosity (78.32%) and the largest pores (118.81 μm), which confirms that a less dense network due to the decrease in collagen concentration and supported by the absence of oil, allows the formation of a more porous and interconnected structure. In J5 (0.1% oil), the porosity decreases slightly to 73.40%, and the pores shrink to 103.93 μm, an effect similar to that observed in J2. The same effect is observed in J6, with 0.2% myrtle oil, as in the case of sample J3, the porosity value (71.62%) and pore size (95.18 μm) decreasing at increased concentrations of essential oil in the polymer network.

The wall thickness varies between 40.42 and 42.95 μm, without significant differences between samples, which suggests a network with walls of similar dimensions and comparable structural stability between formulations. J4 has the thinnest walls (40.42 μm), which, together with its high porosity, indicates a more unstable behavior upon contact with water, suggesting an extensible but fragile network. J3, with the thickest walls, could present a more compact and rigid network, which is also supported by its lower porosity. The specific surface area of the walls (relative to the total volume) is an important parameter for cell adhesion. J4 recorded the highest value (0.09203 μm−1), indicating an extended internal surface area, favorable for interaction with cells or water incorporation. The lower values in J3 and J6 (0.08161 μm−1 and 0.08496 μm−1) confirm the denser nature of the network in the presence of the lower oil concentration.

Overall, the results highlight that decreasing the collagen concentration favors the formation of a more porous network, while the addition of myrtle essential oil in increasing concentrations, can reduce the porosity and permeability of the network, especially when collagen is present in high proportion. Sample J4, containing 1% collagen in the absence of myrtle essential oil, presented the best structural characteristics for skin regeneration applications: high porosity, optimally sized pores and thin but stable walls. These properties are essential for supporting cell migration, nutrient transport and tissue integration.

3.3. FTIR Analyses

FTIR is a widely used method to identify functional groups and evaluate molecular interactions in composite materials. It provides a characteristic chemical “fingerprint” of each structure, thus allowing to follow the changes that occurred following the mixing, crosslinking or interaction processes between the components of a polymer system. For a better understanding of the structure of the obtained hydrogels, a comparison was made between the FTIR spectra of the individual polymers (collagen, pectin and alginate) and those of the hydrogels.

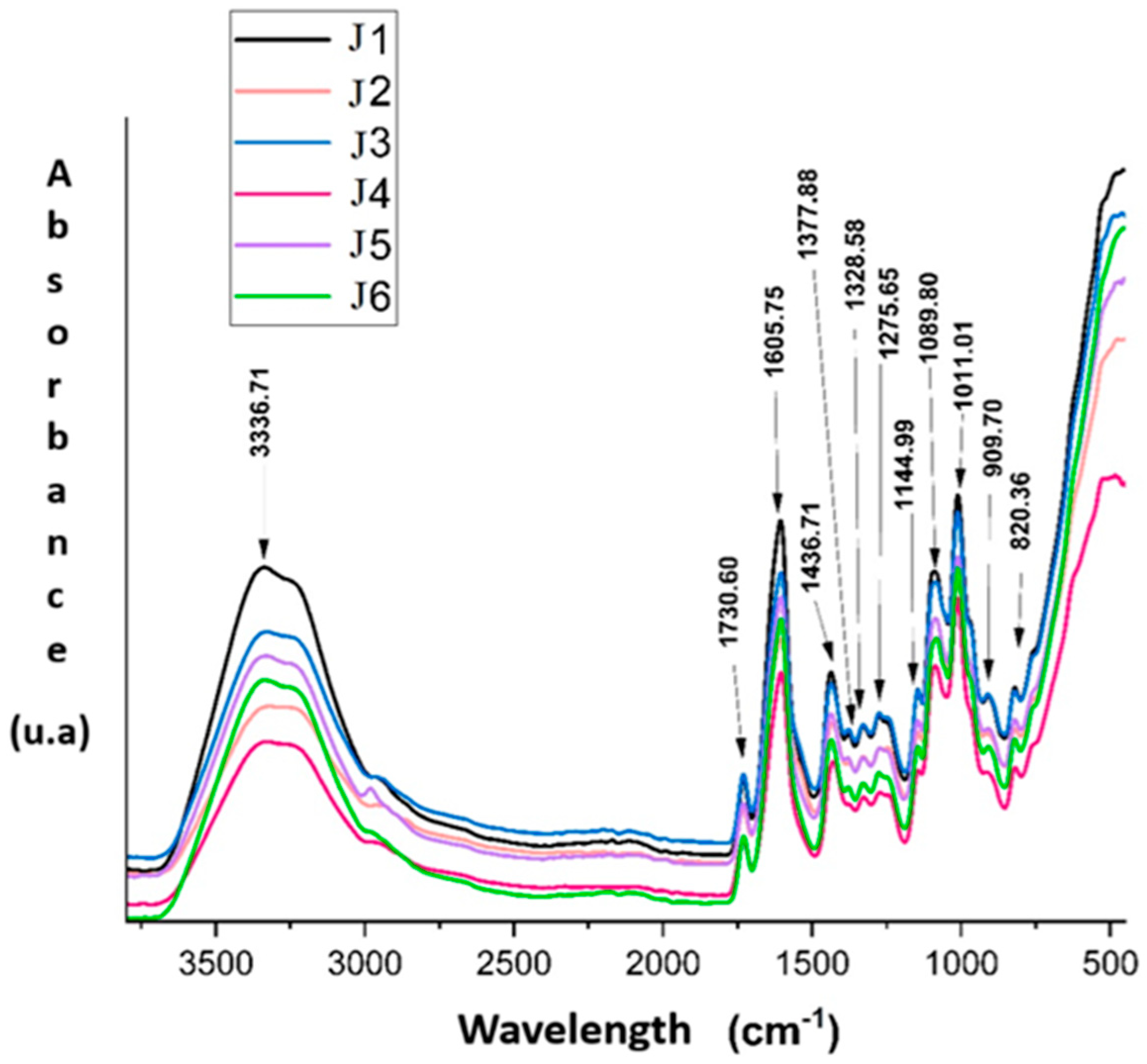

The FTIR spectra presented in

Figure 3 of hydrogels J1–J6 were analyzed in detail, considering the influence of the composition on the chemical structure. In the region of 3600–3000 cm

−1, the broad band around 3336 cm

−1 is associated with the stretching vibrations of hydroxyl (–OH) and amine (–NH) groups, characteristic of polysaccharides and proteins [

49,

50]. This band shows maximum intensity for sample J1 (1.5% collagen, without myrtle oil), suggesting an extensive hydrogen bond network. A gradual decrease in absorption for samples J2 and J3, containing 0.1% and 0.2% myrtle oil, respectively, indicates a possible disruption of the hydrogen bond network by the introduction of the hydrophobic phase. The same trend is observed for samples J4–J6, where the decrease in band intensity correlates with both the reduction in collagen content (1%) and the increase in essential oil concentration.

The band at 1730 cm

−1, attributed to the C=O vibrations of the ester groups in pectin, is present in all samples, which confirms the preservation of the degree of esterification of pectin in the composition of the hydrogels [

51]. The intensity of this band varies slightly, being more pronounced in J1 and J3, possibly due to a more homogeneous structure or a better compatibility between the hydrophilic components and the essential oil at low concentrations.

The regions 1600–1700 cm

−1, and 1500–1580 cm

−1 highlights the characteristic bands of amides I and II, corresponding to the C=O and C–N stretching vibrations of collagen [

49,

50]. The intensity of these bands is significantly higher for samples J1–J3, with 1.5% collagen, compared to J4–J6, which contain only 1%. This difference highlights the direct influence of collagen on the amide signals. In addition, a slight decrease in intensity in the presence of myrtle oil (visible especially for J6) suggests possible collagen–oil interactions that may partially affect the secondary structure of the protein.

Sample J4, although it does not contain essential oil, shows lower absorptions in the O–H and amide regions compared to J1, which confirms the impact of the decrease in collagen concentration on the hydrogel structure. Thus, J4 can be considered a valuable control to highlight the effects of collagen in the absence of hydrophobic interferences generated by the essential oil.

The 1350–1000 cm

−1 region is assigned to the C–O, C–O–C and COO

− vibrations, specific to the polysaccharide matrix formed by pectin and alginate [

51,

52]. The bands in this region (e.g., 1275, 1145, 1083 and 1011 cm

−1) are well defined in all spectra, indicating the stability of the polysaccharide network, but the slightly reduced intensities in the samples with essential oil (especially P6) may reflect a slight reorganization at the molecular level, possibly due to the inhomogeneous distribution of the oil in the network.

In the region < 1000 cm

−1, the bands at 909 and 820 cm

−1 can be attributed to the “out-of-plane” deformations of the C–H bonds and some vibrations characteristic of polysaccharides [

53]. The clear presence of these bands for J1–J3 and their attenuation for J6 may indicate a decrease in structural ordering in the hydrogels with higher essential oil concentration and reduced collagen.

Overall, these FTIR observations confirm the participation of each polymer in the formation of the hydrogel network, through chemical and physical interactions highlighted by changes in the position, intensity and shape of the spectral bands. The composition of the hydrogels directly influences the degree of molecular organization, structural stability and the nature of the interactions between the components.

Collagen significantly influences the amide and hydroxyl regions, and myrtle oil seems to reduce the degree of molecular organization through hydrophobic interferences. J1 and J3 present the best-defined bands, suggesting a stable and homogeneous network, while J6 exhibits the lowest absorptions, which reflects a less dense molecular structure and possibly an uneven dispersion of the components.

3.4. Swelling Degree and Stability Tests

Testing the swelling degree and stability of hydrogels in aqueous media is an essential step in the characterization of these materials, especially when they are intended for biomedical applications, such as wound healing dressings or controlled release systems of active substances. The degree of swelling reflects the ability of the hydrogel to absorb fluids, which directly influences tissue hydration, nutrient exchange and local comfort, while structural stability indicates the resistance of the polymer network in wet environments over the long term, being essential for maintaining physical integrity and functionality during application. Adequate swelling, combined with good stability, can highlight an optimal balance between absorption capacity and internal cohesion of the hydrogel, important criteria in the design of functional materials [

54,

55].

Figure 4 illustrates the evolution of the swelling degree (%) over time for the six hydrogel formulations (J1–J6), evaluated at time intervals ranging from 1 min to 1440 min. Significant differences are observed between the samples in terms of water absorption capacity, influenced by their composition, in particular by the content of collagen and myrtle essential oil, but also by the degree of crosslinking on the swelling capacity of the hydrogels. Crosslinking, achieved in this case using glutaraldehyde and calcium ions (Ca

2+), determines the formation of the three-dimensional network that confers stability to the hydrogel, but which, at the same time, limits its expansion in an aqueous environment. The error bars added to each column indicate the experimental variation (standard deviation), confirming the reproducibility of the data.

Sample J1 containing 1.5% collagen, without oil, shows high values of swelling degrees, but slightly lower than J4 which has 1% collagen in its composition, suggesting possible differences in structure or degree of crosslinking. Sample J4 shows the highest values of swelling degree, exceeding 8000% at 90 min and maintaining a high level throughout the test period. This behavior is attributed to the lower presence of collagen in the sample structure, which favors water absorption through the less dense structure of the hydrogel, but also to the absence of essential oil, which would otherwise reduce the hydrophilic character of the matrix [

56,

57]. It is observed that samples with the same polymer content, but with the presence of myrtle essential oil (e.g., J2 and J3 compared to J1, and J5 and J6 compared to J4), show lower swelling degrees, which suggests that oil, by its hydrophobic nature, modifies the homogeneity of the network and indirectly influences the efficiency of crosslinking.

Samples J1 and J4, in which the network appears loose (due to the absence of oil), present high values of the swelling degree, signaling a better balance between structural stability and absorption capacity. Thus, it can be concluded that the degree of crosslinking inversely influences the swelling degree: a network that is too dense reduces the hydration capacity, while a network that is too weakly crosslinked can lead to degradation or loss of structural integrity.

As for samples J2 and J3, which contain 1.5% collagen and myrtle essential oil (0.1% and 0.2%, respectively), they present intermediate swelling degrees, significantly lower than J1 (without oil), but higher than J5 and J6 (with less collagen). This behavior suggests that the presence of the essential oil begins to limit the water absorption capacity.

In contrast, samples J5 and J6, which contain only 1% collagen and myrtle essential oil (0.1% and 0.2%, respectively), present the lowest swelling degrees, being below 3000% throughout the tested range. This result can be explained by the hydrophobic effect of the essential oil, which limits water absorption and reduces the expansion of the hydrogel network.

It is also noted that, in the case of all samples, the swelling degree increases rapidly in the first 60–90 min, after which it reaches a plateau or fluctuates slightly. This behavior is characteristic of hydrogels that reach a hydration equilibrium, and the absorption capacity becomes limited by the internal structure of the network.

At the same time, the long-term constant values indicate a good dimensional stability of the samples in aqueous medium, highlighted in

Figure 5. The figure presented illustrates the mass loss of samples J1–J6 after immersion in water for 7 days. It is observed that sample J4 presents the highest mass loss, with an average of approximately 22%, accompanied by a considerable standard deviation, which indicates a low structural stability and a possible significant degradation of the polymer network in aqueous medium. This behavior is consistent with the high values of the swelling degree recorded for the same sample, suggesting that a highly expandable network can also be fragile and prone to material loss over time. In contrast, samples J3, J5 and J6 present the lowest mass losses (between 8–10%), indicating a superior structural stability. These samples contain myrtle essential oil in concentrations of 0.1% or 0.2%, which suggests that the oil, through its hydrophobic character, contributes to reducing the dissolution of the network in water and protects the hydrogel structure. Also, J1 and J2, both with 1.5% collagen, but without, respectively with 0.2% oil, show a moderate loss, which confirms that the stability is influenced not only by the amount of collagen, but also by the total composition and the interaction between the components.

This evaluation of the samples highlights that the balance between swelling capacity and stability is essential to understand the behavior of such hydrogels for the development of biomaterials used in skin wound treatment. Samples that include essential oil appear to offer better resistance to degradation in aqueous media, which recommends them for longer-term uses, while oil-free formulations, although able to absorb more liquid, are more prone to material loss.

3.5. Antimicrobial Activity

Testing the antibacterial activity of materials intended for skin regeneration applications is an essential step in assessing their safety and efficacy [

58,

59]. Especially in the case of hydrogels used as dressings, controlled release systems or matrices for tissue engineering, the ability to prevent the formation of bacterial colonies is crucial to reduce the risk of infections and to support the tissue regeneration process. Bacteria can quickly adhere to the surface of materials that come into direct contact with tissues and can form biofilms resistant to conventional treatments, which is why it is necessary to evaluate the antimicrobial potential of materials. Antibacterial tests allow the identification of effective formulations and the optimization of the composition, especially when natural compounds, such as essential oils, are used. The antibacterial activity test of the obtained hydrogels was performed according to standardized methods.

The results obtained from testing the antibacterial activity of hydrogels J1–J6 against the Gram-positive strain (

Staphylococcus aureus) highlight a correlation between the presence of myrtle essential oil and the antimicrobial efficiency of the samples. All samples showed a satisfactory antibacterial effect, observed in

Figure 6, indicated by the absence of any bacterial growth in the contact area with the sample, but the size of the Growth Inhibition Zone Diameter (GIZD) differs significantly depending on the composition.

Sample J1, containing 1.5% collagen and without myrtle oil, showed a minimal inhibition zone of only 1 mm, which indicates a weak activity, probably due exclusively to the barrier effect of the hydrogel. In contrast, samples J2 and J3, in which 0.1% and 0.2% myrtle essential oil were incorporated, showed significantly larger inhibition zones, 4 mm in the case of J2 and 5 mm for J3, demonstrating a progressive increase in antibacterial activity with increasing oil concentration.

Regarding the testing of the antibacterial activity of samples J4 against Staphylococcus aureus, similar to the first three samples, a clear influence of the presence and concentration of myrtle essential oil on antimicrobial efficiency is observed, this time in the context of a lower collagen concentration (1%). Sample J4, which does not contain essential oil, recorded an inhibition zone of 1 mm, suggesting a weak antibacterial effect, most likely determined by the physical barrier of the hydrogel and not by an active inhibition mechanism. This result is comparable to that of sample J1, suggesting that, in the absence of essential oil, collagen, regardless of concentration, does not significantly influence antibacterial activity.

In contrast, samples J5 and J6, containing myrtle essential oil at concentrations of 0.1% and 0.2%, respectively, demonstrated significantly increased antibacterial activity, with inhibition zones of 6 mm and 10 mm, respectively. These results highlight a clear dose-effect relationship, in which increasing the concentration of essential oil causes a progressive expansion of the zone devoid of bacterial growth. Furthermore, J6 presents the largest inhibition zone among all the samples tested, indicating remarkable efficiency against S. aureus, even in the context of a lower collagen content. This aspect suggests that the antibacterial activity is dominated by the presence of essential oil, which probably diffuses efficiently from the hydrogel matrix into the environment and inhibits the growth of the microorganism.

In conclusion, comparing the results, it is observed that, at higher oil concentrations and lower collagen concentrations, the antibacterial effect is significantly greater than that of samples with more collagen, indicating that the less dense network of the hydrogel may allow for a more efficient release of the active compound.

Similarly, the results obtained for the antibacterial tests of the hydrogels against the bacterium

Escherichia coli confirm, similarly to those performed on

Staphylococcus aureus, the significant influence of myrtle essential oil on the antimicrobial efficiency of the samples. The results are confirmed by

Figure 7.

Samples J1 and J4, which do not contain essential oil (but only collagen in concentrations of 1.5% and 1%, respectively), presented very low inhibition zones (1 mm and 2 mm), indicating a weak antibacterial effect, due exclusively to the physical contact with the hydrogel and not to an active antimicrobial effect. This highlights the fact that, in the absence of an active agent, the tested material does not show relevant activity against the Gram-negative bacterium E. coli, known for its increased resistance to external agents.

In contrast, with the introduction of myrtle oil, a clear increase in antibacterial efficiency is observed. Samples J2 and J5, both containing 0.1% essential oil, show inhibition zones of 3 mm and 4 mm, respectively, indicating moderate antibacterial activity, but significantly better than the controls without oil. The best results were obtained for samples J3 and J6, containing 0.2% essential oil, both having inhibition zones of 6 mm, demonstrating strong and effective antibacterial activity even against a resistant bacterium, such as E. coli.

The results confirm that the effect of the oil is also effective on Gram-negative bacteria, thus giving the hydrogels important therapeutic potential in the context of resistant bacterial infections, and the difference between the two values of the degree of inhibition for the two types of bacteria tested may be due to the structure of the cell wall.

3.6. Biocompatibility Tests

The evaluation of the cellular biocompatibility degree of samples J1–J4, was performed using the in vitro cellular tests, including the XTT assay for cell viability and the LDH-release assay for cytotoxicity.

The results were expressed as mean absorption ± standard deviation and were compared with the no treatment cell control, to highlight the influence of each formulation on cell viability, represented in

Table 3.

Sample J1 (without myrtle essential oil) presented a viability of 90.95 ± 2.57%, which indicates a minimal interaction with cellular metabolism, without significant toxic effects. The addition of 0.1% myrtle oil in the composition of sample J2 determined a slight increase in viability (94.38 ± 2.68%), suggesting that this plant compound has no harmful effects on cells, and in low concentrations it can even support cellular activity. Sample J3, containing 0.2% myrtle oil, recorded an average biocompatibility value of 95.26 ± 10.64%, maintaining the same positive trend, although the variability is slightly higher, which could be attributed to the more complex interactions between the hydrogel components and the cells. The highest viability value was recorded for sample J4 (99.53 ± 11.88%), indicating an exceptional compatibility with the cells used, almost identical to that of the untreated control.

These results highlight the fact that all four hydrogels are biocompatible and the presence of myrtle essential oil, in concentrations up to 0.2%, does not negatively affect cell viability. Results are similar with literature findings, indicating the potential positive benefits of including myrtle essential oil in wound dressings [

60] and other wound healing related biomaterials. On the contrary, a slight tendency to stimulate cell activity is observed, possibly through the antioxidant or anti-inflammatory effect of the active compounds in myrtle oil. Thus, the obtained hydrogels can be considered suitable for biomedical applications, such as dressings or matrices for tissue regeneration, where direct contact with cells is unavoidable. The results also suggest that optimizing the concentration of natural components can contribute not only to maintaining compatibility, but also to improving the biological behavior of the developed materials.

Figure 8 shows that the absorption values obtained for all four samples were close to those of the control (cells without treatment), indicating a high level of normal metabolic activity and, implicitly, good compatibility with the tested cells.

Table 4 shows the calculated cytotoxicity values of samples J1–J4.

The graphical representation illustrated in

Figure 9 shows the results of the LDH release test for hydrogel samples J1–J4, compared to the negative control (NT Cells—cells without treatment) and the positive control (cells treated with Triton X-100 0.1% for stimulating high LDH-release).

The absorbances recorded for samples J1–J4 are all located in a low range and close to that of the negative control, which suggests that the tested materials do not induce a significant degree of cytotoxicity. Specifically, the OD values for J1–J4 are around 0.25–0.28, very close to the value recorded for NT Cells, indicating that the cells exposed to the hydrogels maintain their membrane integrity and, implicitly, viability. These results support the data obtained in the XTT test, where a high metabolic activity was observed, confirming the biocompatibility of the hydrogels. Sample J1 presents the lowest cytotoxicity, with a percentage of 4.33 ± 1.93%, which suggests a minimal damage to the cells, comparable to the negative control. Samples J3 (8.98 ± 1.32%) and J4 (8.12 ± 7.44%) recorded low values, indicating low cytotoxicity and good compatibility with the tested cells. Sample J2 stands out with a higher cytotoxicity percentage (15.00 ± 3.68%), which could be attributed to a more pronounced cellular reaction to its composition, even though its absorption remains below the threshold considered critical in the assessment of biocompatibility (<20%). This sample indicates changes in the cell membrane and proliferation rate. Contrast microscopy images highlight cells with a slightly pyknotic, rounded appearance, the effect observed by exposing the cells to the product of interest being a morphological alteration of the cell colony and/or the cell shape in the monolayer culture (slowing down of metabolism). It is recommended to evaluate at longer contact times (48 h, 72 h).

Compared to the positive control (Positive LDH), which shows a high absorption corresponding to high LDH release (increased cytotoxicity), all four samples show significantly lower values, confirming that the tested hydrogels do not induce extensive cell lysis.

In this context, in vitro cytotoxicity tests are confirmed to be indispensable in the pre-validation stage of materials, representing an ethical and efficient alternative to animal models. The use of cell cultures relevant to the final application provides valuable information on the possible toxic reactions of the material on the target tissue.

All tested samples show an acceptable biocompatibility profile. Sample J4 is the most promising, combining high cell viability and minimal cytotoxicity, being suitable for biomedical applications (e.g., tissue engineering). Although J4 exhibited the highest mean viability, the large standard deviation suggests variability in cell–material interactions, likely due to the highly porous and less mechanically stable structure of this formulation, which may result in uneven contact with the cell monolayer. Sample J2 raises an alarm regarding increased cytotoxicity, requiring additional optimization steps. The elevated cytotoxicity observed for J2 indicates that this formulation may induce transient membrane stress. This represents a limitation of the current study, and future work will include longer exposure times (48–72 h) and additional assays to better elucidate this response.

Biocompatibility testing was performed only on J1–J4 because these formulations were selected as representative models for assessing the influence of collagen concentration and essential oil addition in the first stage of biological evaluation. Samples J5 and J6, although showing strong antibacterial activity, exhibited lower swelling capacity and reduced structural stability, making them less suitable candidates for direct contact with cells in preliminary tests. However, we acknowledge that excluding J5 and J6 is a limitation of the current study. Future work will include their full biocompatibility assessment to validate their potential for biomedical applications.

In conclusion, the differences observed between the samples suggest that compositional variations may influence cellular behavior to some extent, and overall, all samples can be considered biocompatible, in accordance with accepted standards for biomedical applications.

4. Conclusions

The study focused on the development, characterization, and evaluation of J1–J6 hydrogels based on type I collagen, pectin, alginate, and myrtle essential oil, intended for potential skin regeneration applications. The formulations differed in collagen content (1% and 1.5%) and myrtle essential oil concentration (0–0.2%) to assess their impact on structural, functional, and biological properties.

FTIR analysis confirmed the involvement of all components in hydrogel network formation, with collagen contributing predominantly to amide and hydroxyl bands, while myrtle essential oil influenced molecular organization through hydrophobic interactions. Swelling studies revealed that hydrogels with higher collagen content exhibited superior water retention, attributed to a denser and more crosslinked polymeric network. Micro-CT results showed high porosity (up to 78%) and pore sizes proper for nutrient transport and cell migration.

Stability tests indicated low mass loss in aqueous environments, although sample J4 showed higher degradation associated with increased porosity. Antibacterial assays demonstrated a strong antimicrobial effect of myrtle essential oil, particularly at 0.2% concentration (J3 and J6), with effective inhibition against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Cytocompatibility evaluations (XTT and LDH) confirmed high cell viability (>90%) and low cytotoxicity for most samples, while J2 requires further optimization.

Overall, all hydrogels exhibited favourable functional and biological characteristics, with formulation J4 emerging as the most promising candidate due to its balanced swelling behaviour, stability, antibacterial activity, and biocompatibility, supporting its potential use in wound healing and skin regeneration applications.