Composite Bonded Anchor—Overview of the Background of Modern Engineering Solutions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Aim and Scope of the Conducted Analysis

3. Scientometric Analysis-Composite Bonded Anchors

3.1. Analysis of Scientific Literature

3.2. Detailed Scientometric Analysis

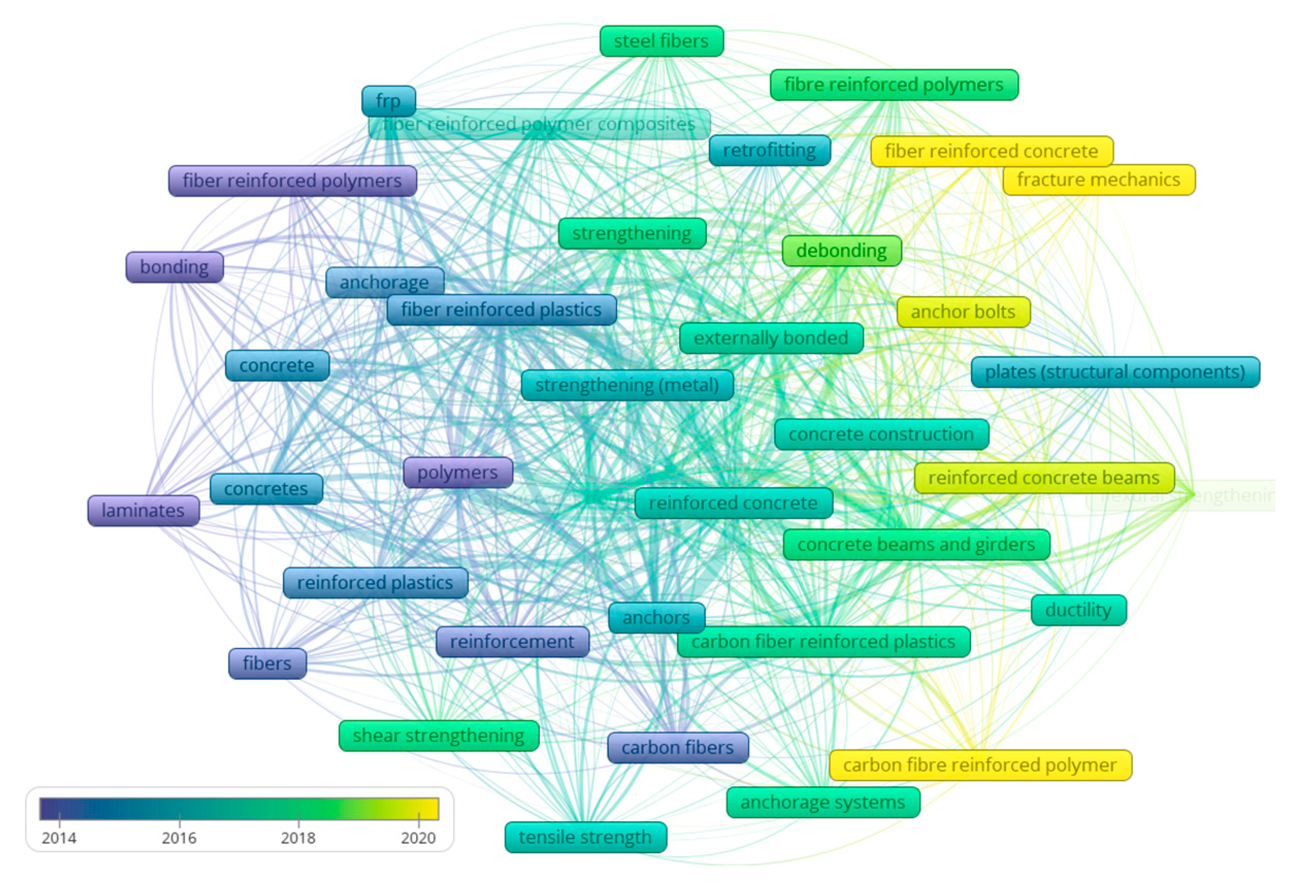

3.2.1. Detailed Scientometric Analysis–Composite Bonded Anchors

3.2.2. Detailed Scientometric Analysis–Composite PET with Fibers

3.3. Analysis of the Lifecycle Costs of Bonded Anchor Composite

- CAPEX: material costs, transportation, installation.

- OPEX: periodic maintenance and repairs.

- User costs: costs borne by the user (downtime, detours, disruptions).

- End-of-Life (EoL): dismantling, recycling, and recovery revenues.

3.4. Analysis of Available Patent Databases

4. Design Guidelines for Bonded Composite Anchors

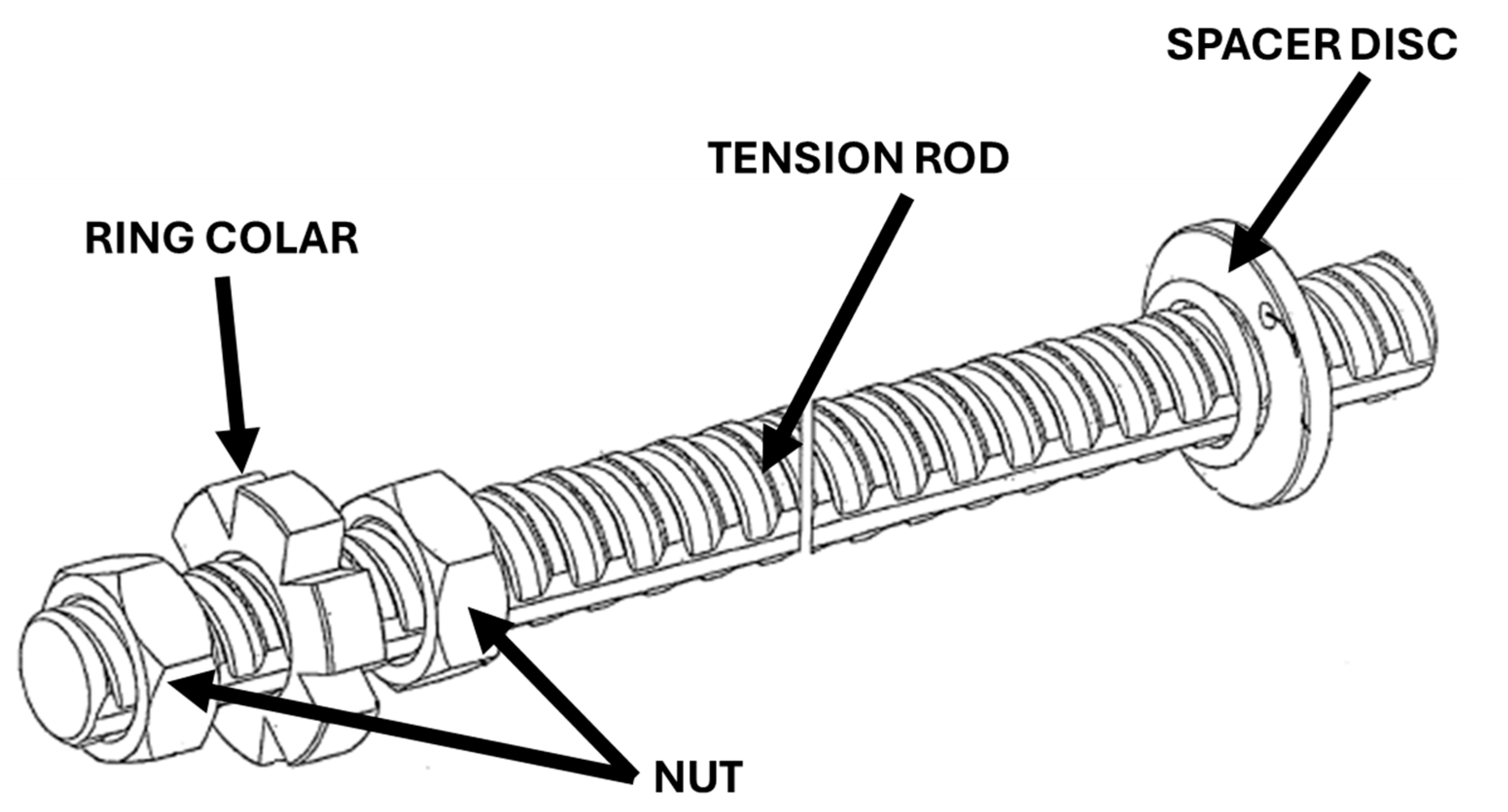

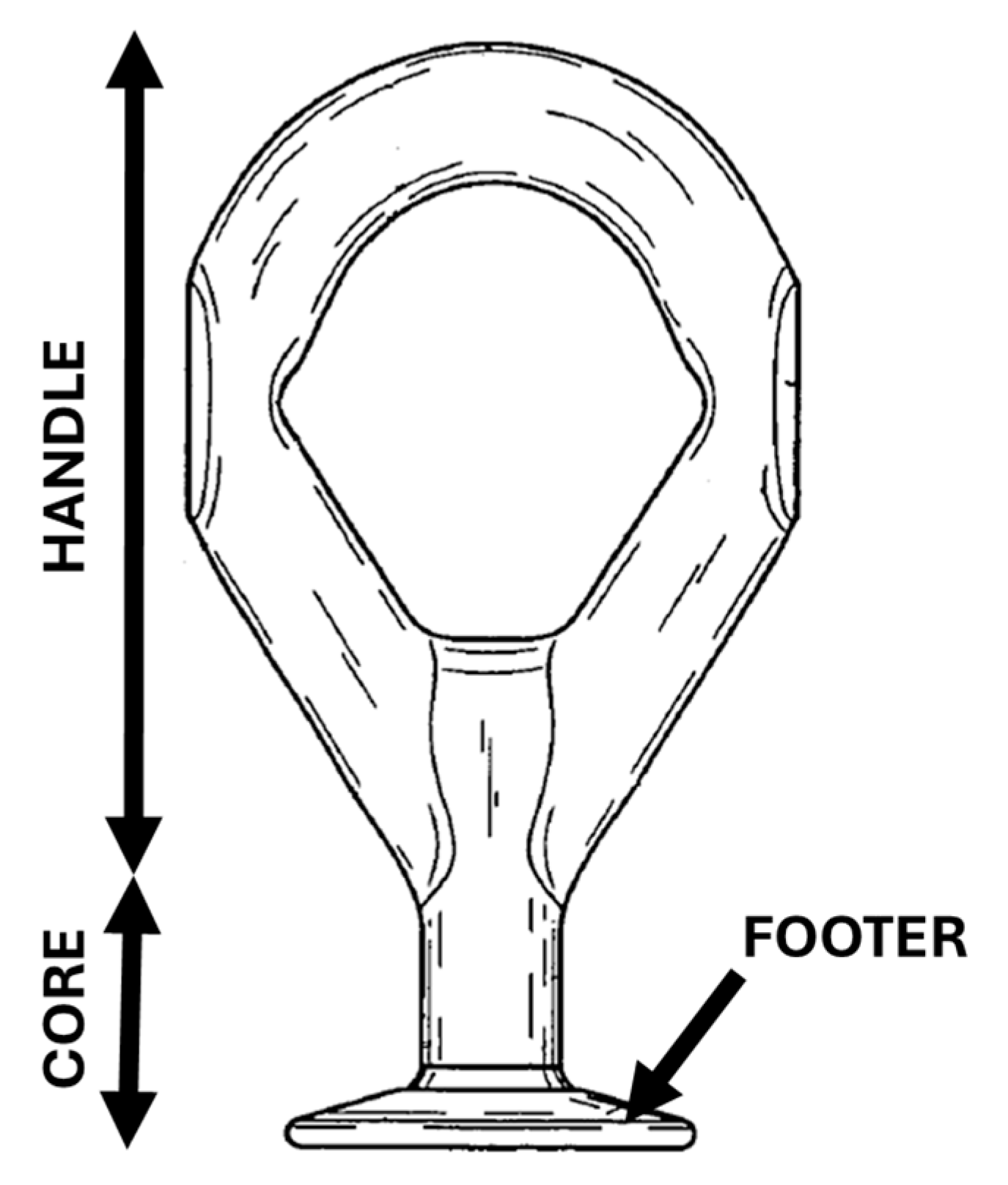

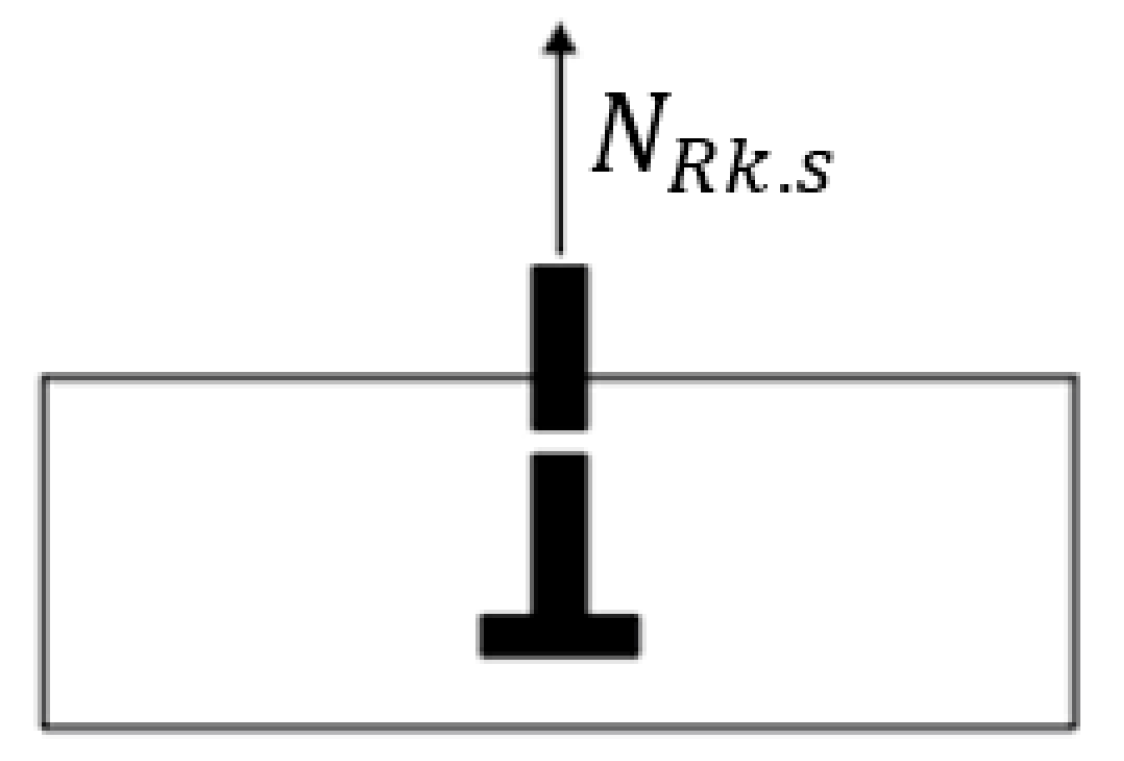

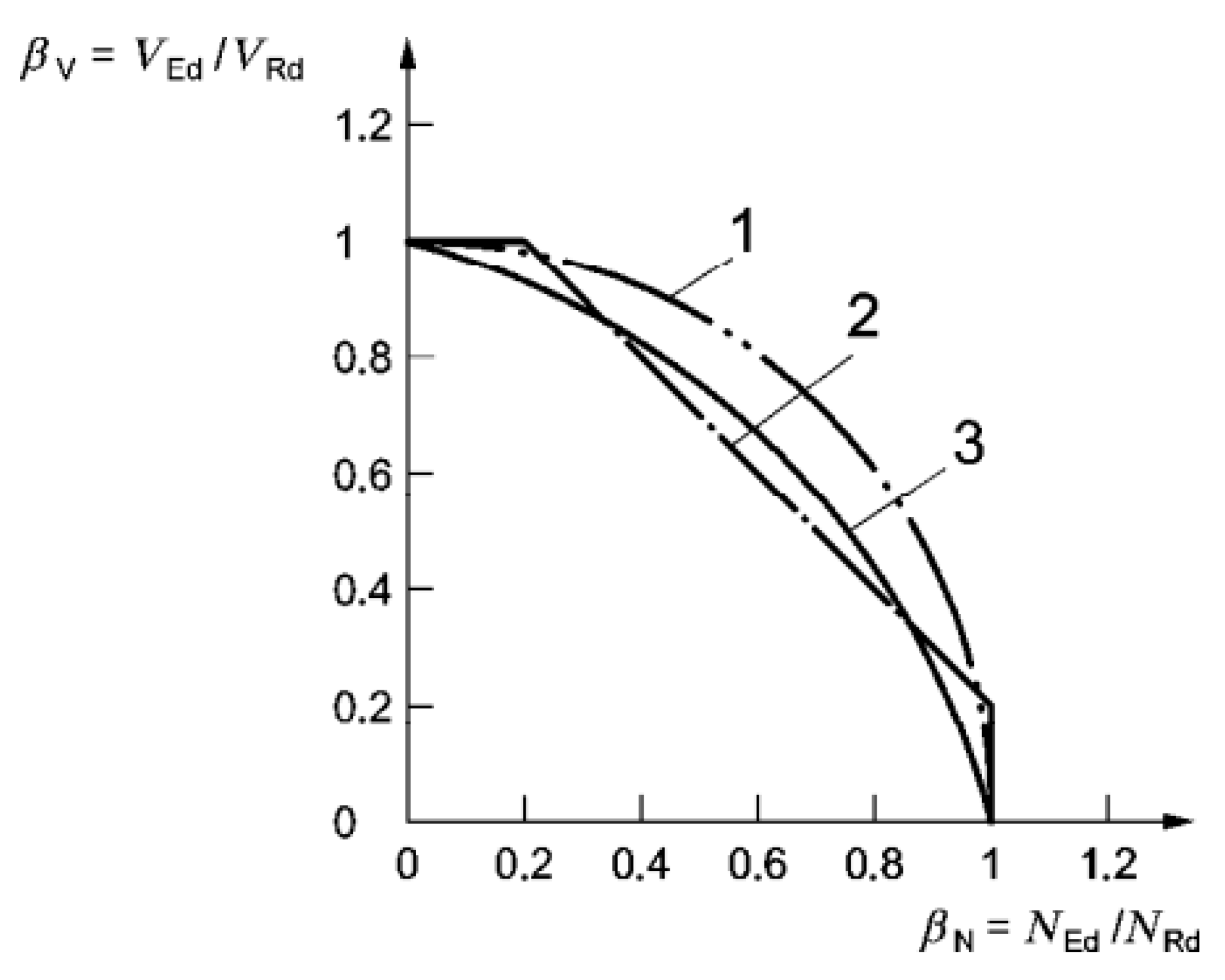

4.1. Basics of Designing Bonded Anchors

4.2. Basics of the Design of FRP Bar Constructions

4.3. Summary and Conclusions of Available Design Guidelines

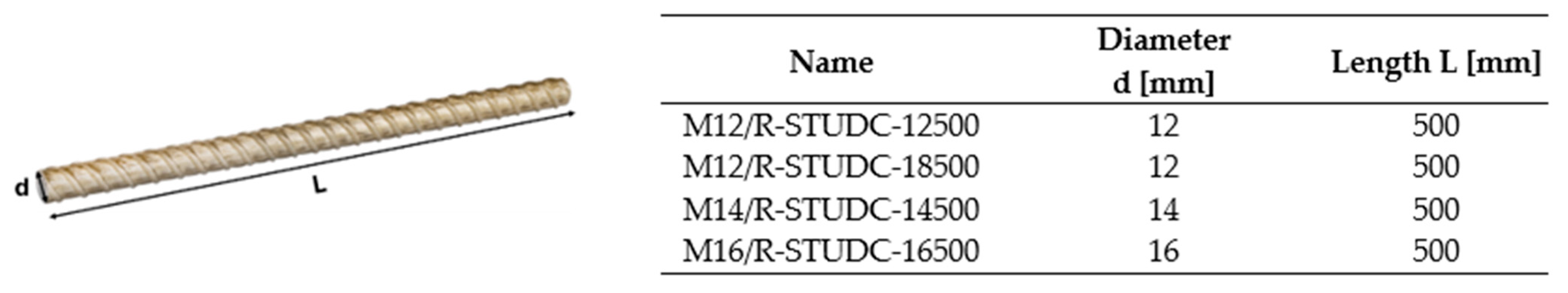

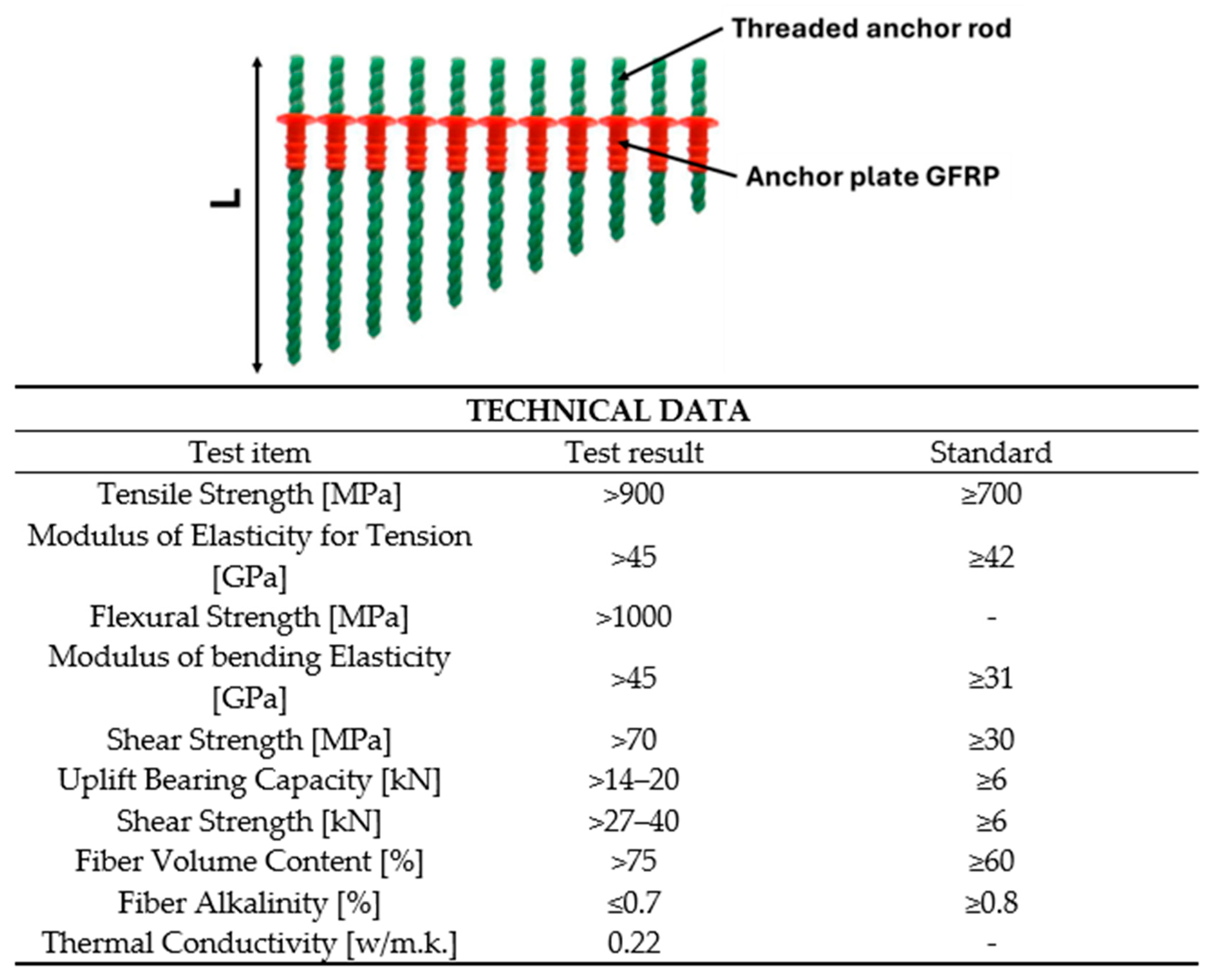

5. Composite Bonded Anchors-Market Identification

6. Summary and Conclusions

7. Futures and Perspectives

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviations | |

| FRP | Fiber Reinforcement Polymer |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| rPET | Recycled Polyethylene terephthalate |

| FEM | Finite Element Method |

| CTE | Coefficient of Thermal Expansion |

| CFRP | Carbon Fiber Reinforcement Polymers |

| ETA | European Technical Approvals |

| ULS | Ultimate Load States |

| SLS | Serviceability States |

| ETAG | European Technical Approval Guideline |

| EOTA | European Organization for Technical Approvals |

| ASTM | American Society for Testing and Materials |

| Nomenclature | |

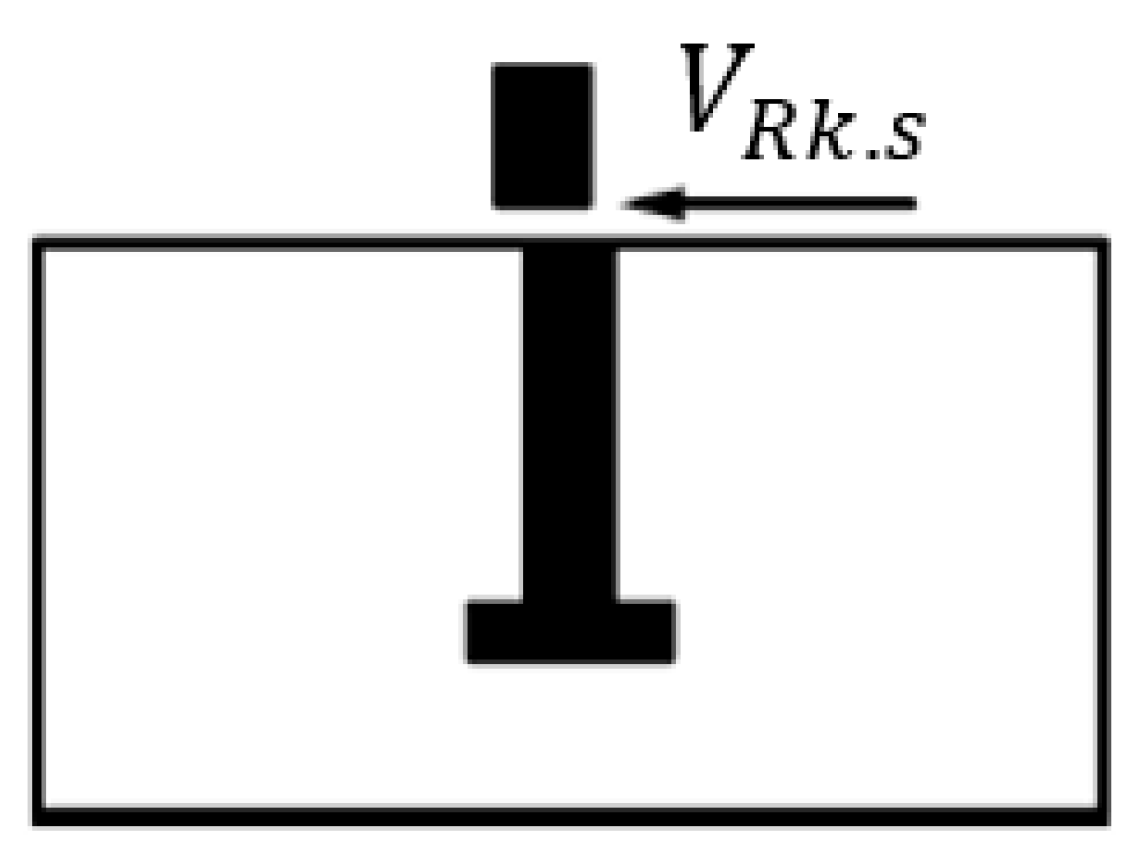

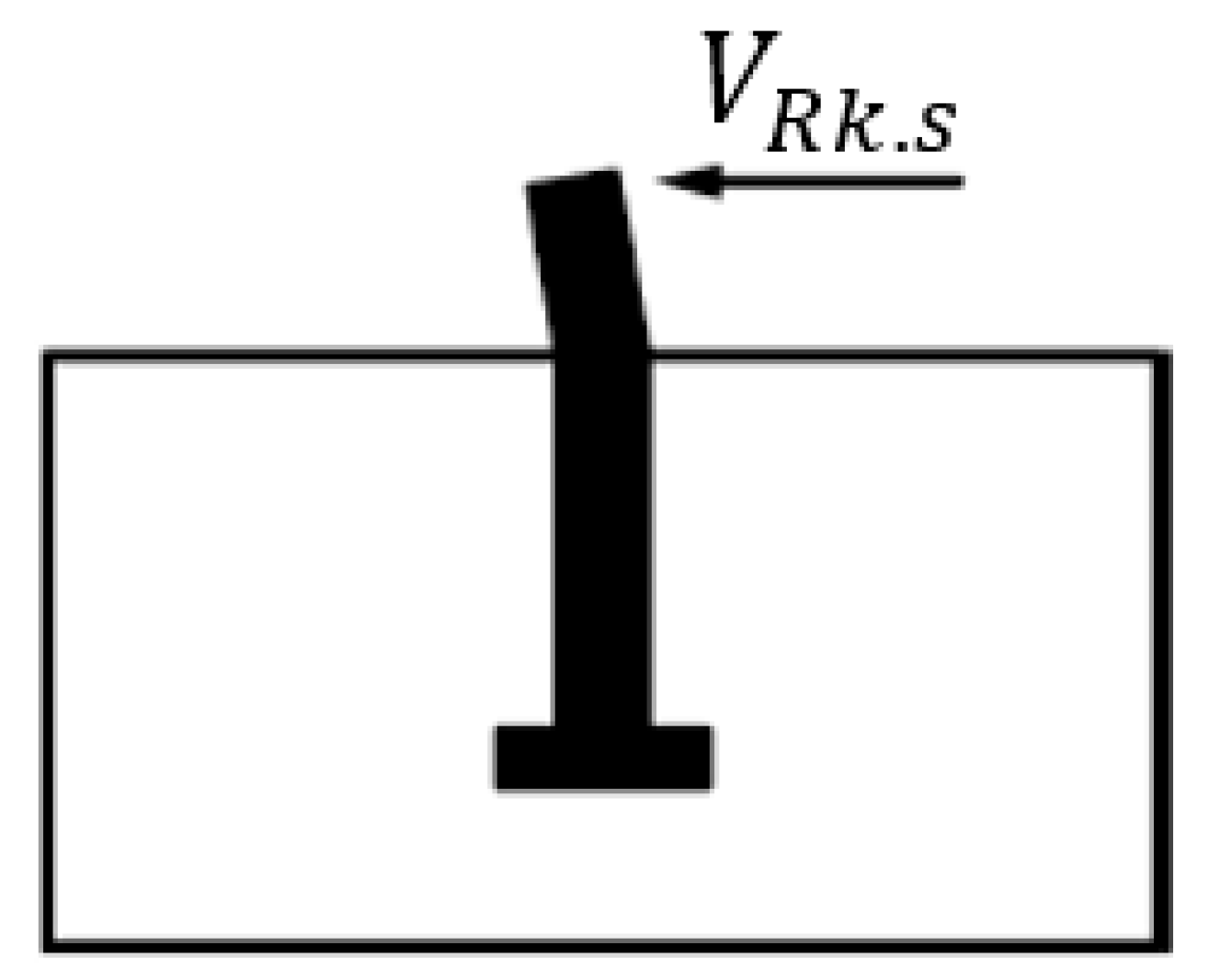

| characteristic resistance of an anchor in case of steel failure [N] | |

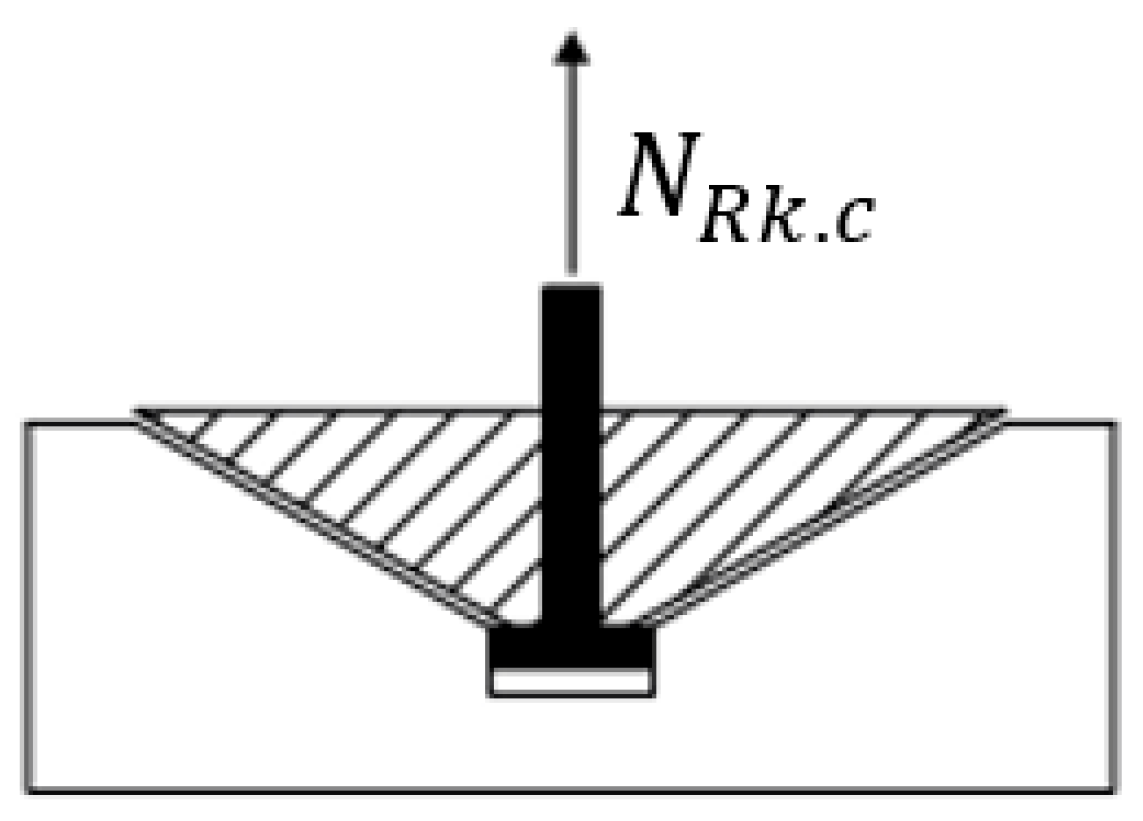

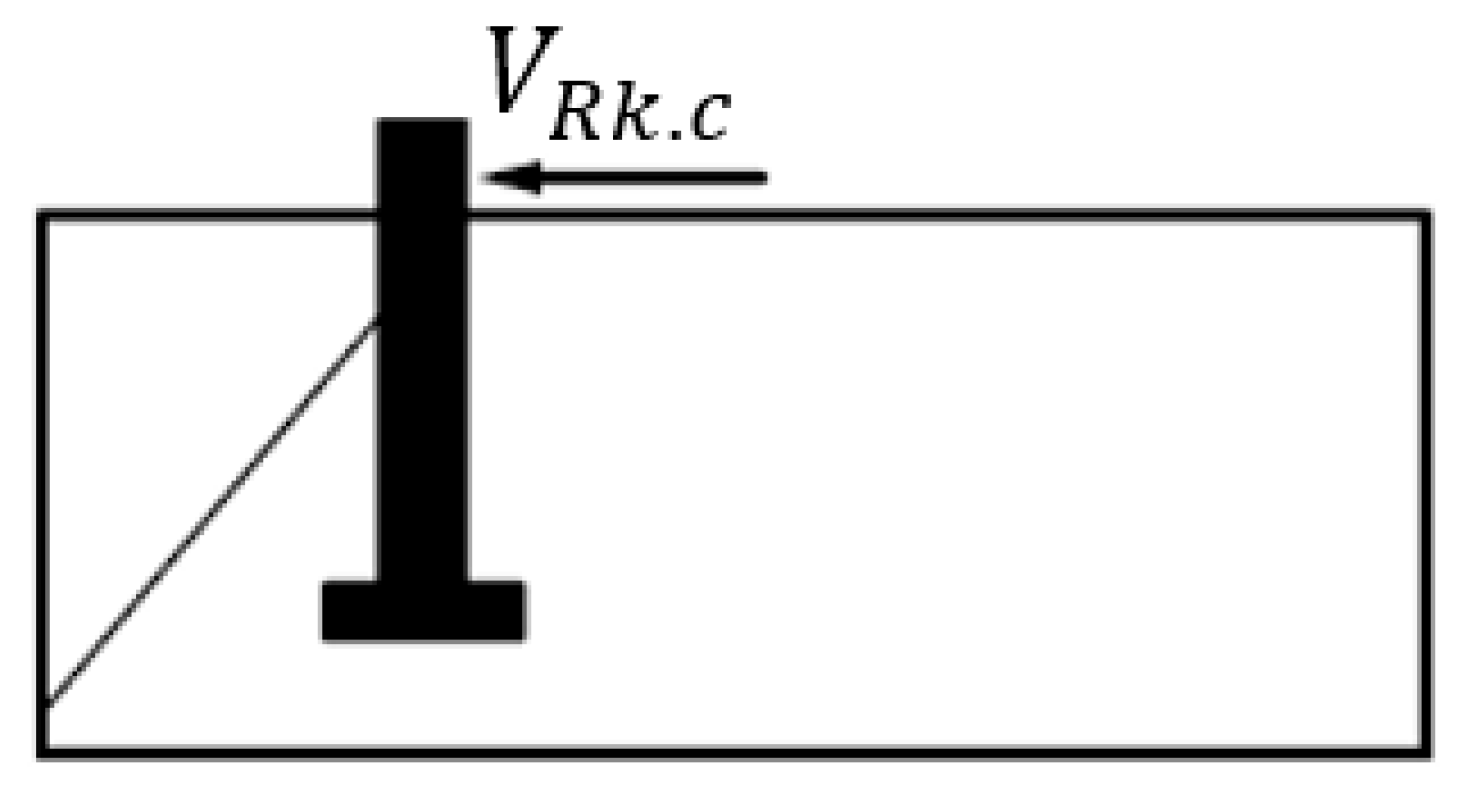

| characteristic resistance of an anchor in case of concrete cone failure [N] | |

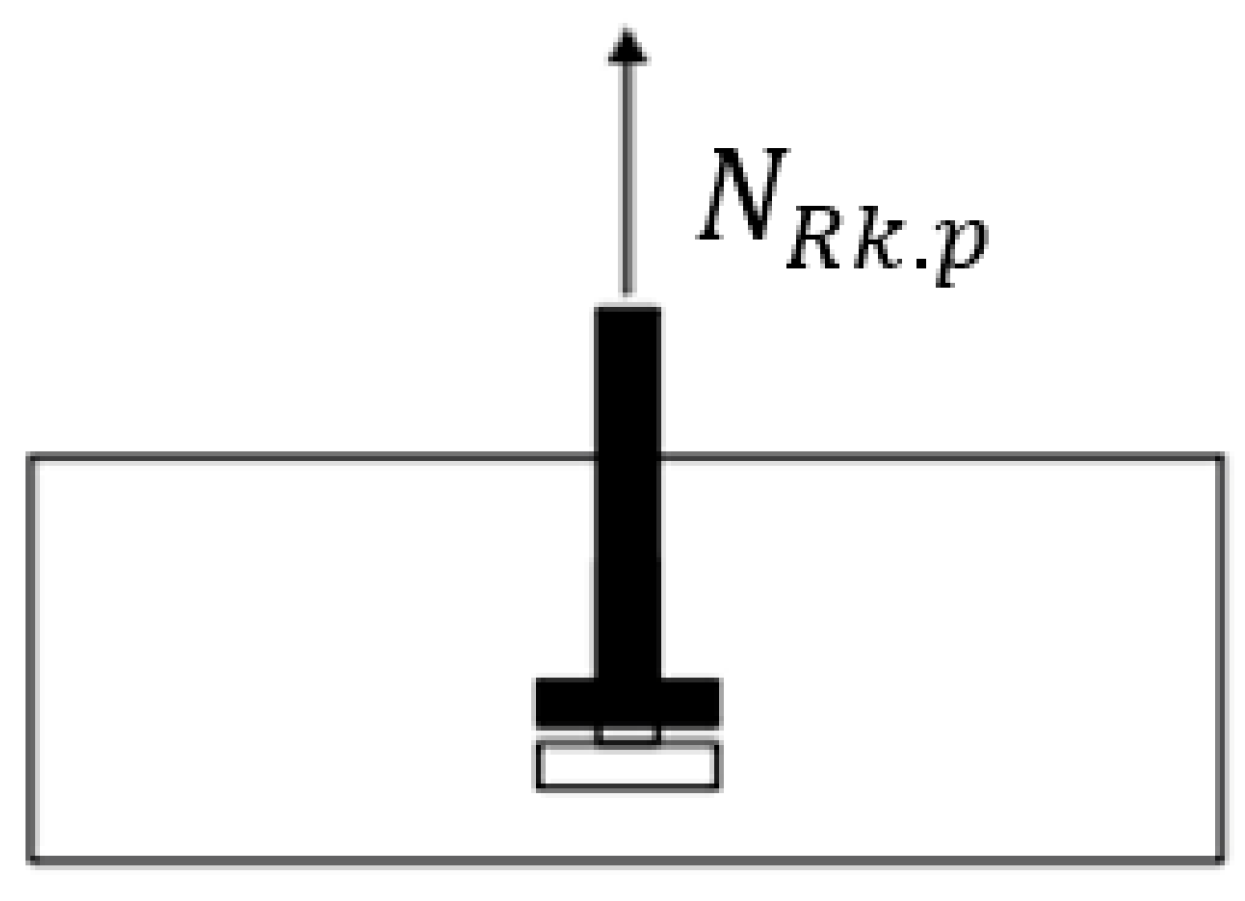

| characteristic resistance of an anchor in case of pull-out the anchor [N] | |

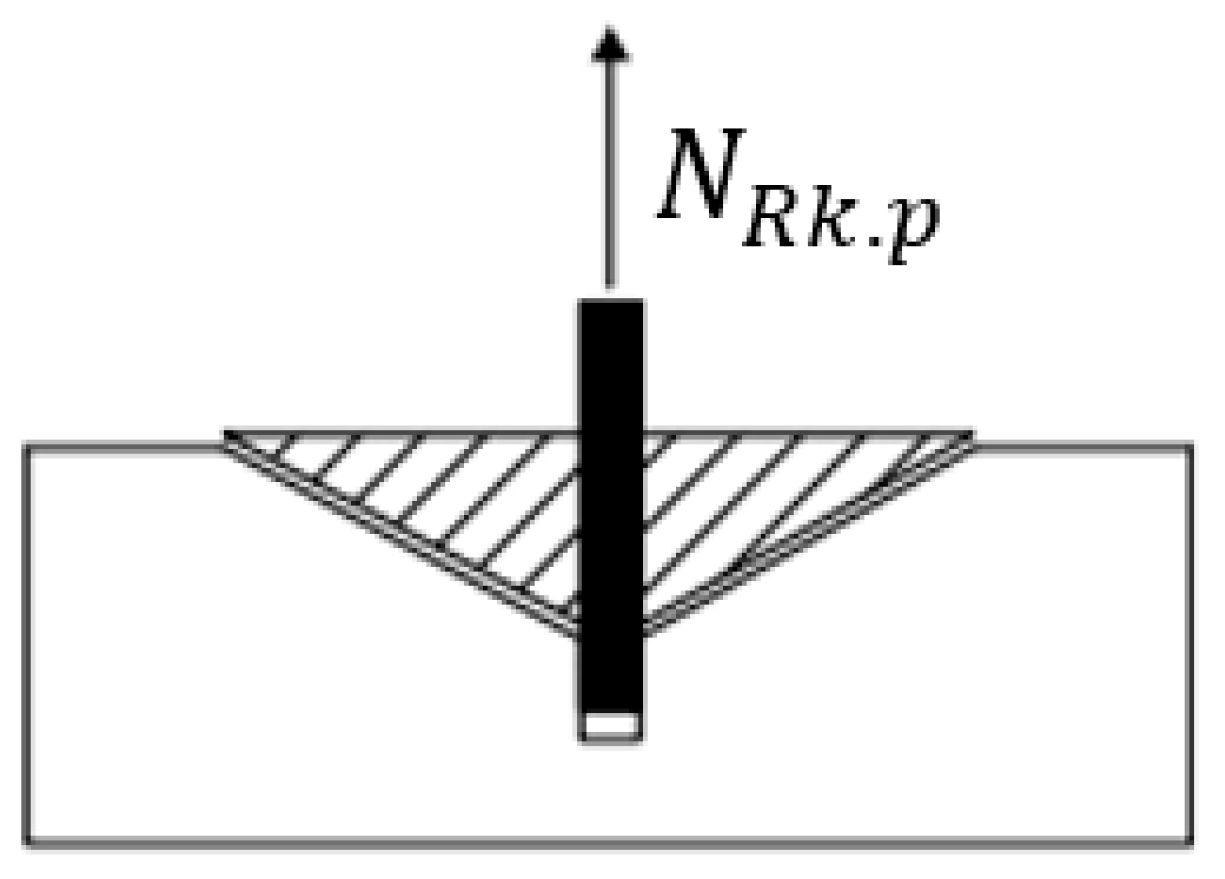

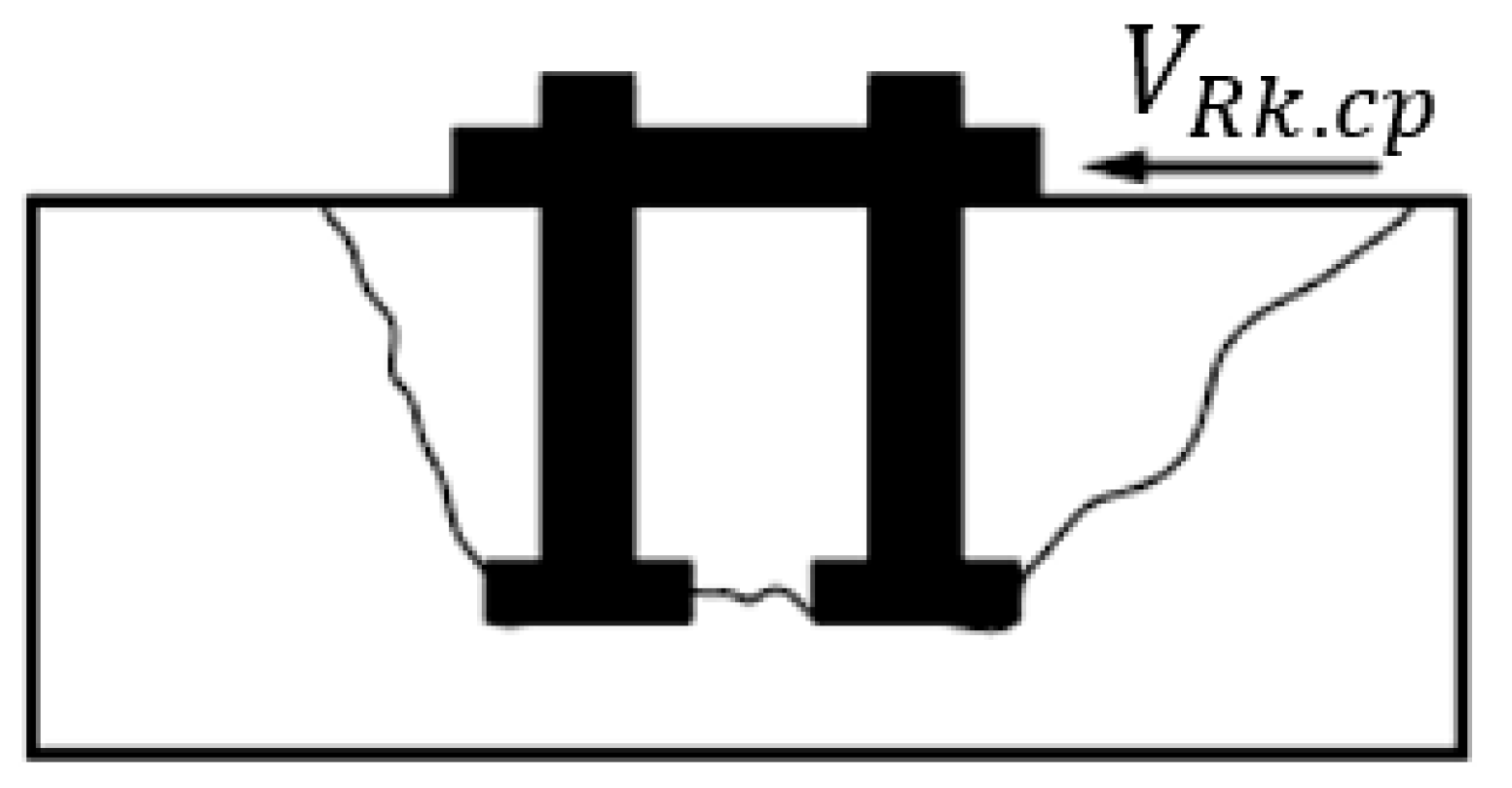

| characteristic resistance of an anchor in combined pull-out and concrete cone failure [N] | |

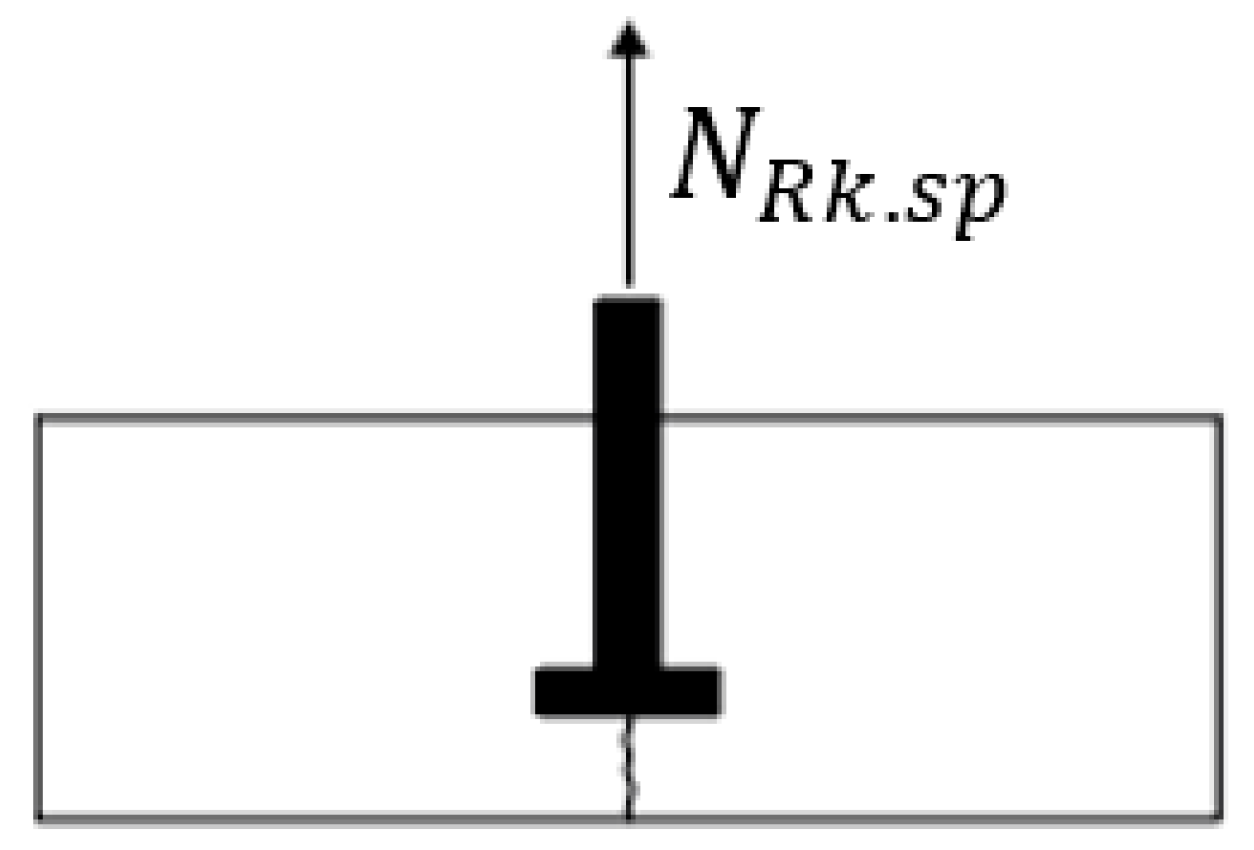

| characteristic resistance of an anchor in case of structural cracking [N] | |

| characteristic resistance of an anchor in case of steel failure without consideration of the arm of force [N] | |

| characteristic resistance of an anchor in case of steel failure considering the arm of force [N] | |

| characteristic resistance of an anchor in case of tearing out the concrete [N] | |

| characteristic resistance of an anchor in case of chipping off the edge of the concrete [N] | |

References

- Ramirez, R.; Muñoz, R.; Lourenço, P.B. On Mechanical Behavior of Metal Anchors in Historical Brick Masonry: Testing and Analytical Validation. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 3999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderini, C.; Piccardo, P.; Vecchiattini, R. Experimental Characterization of Ancient Metal Tie-Rods in Historic Masonry Buildings. Int. J. Archit. Herit. 2019, 13, 425–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

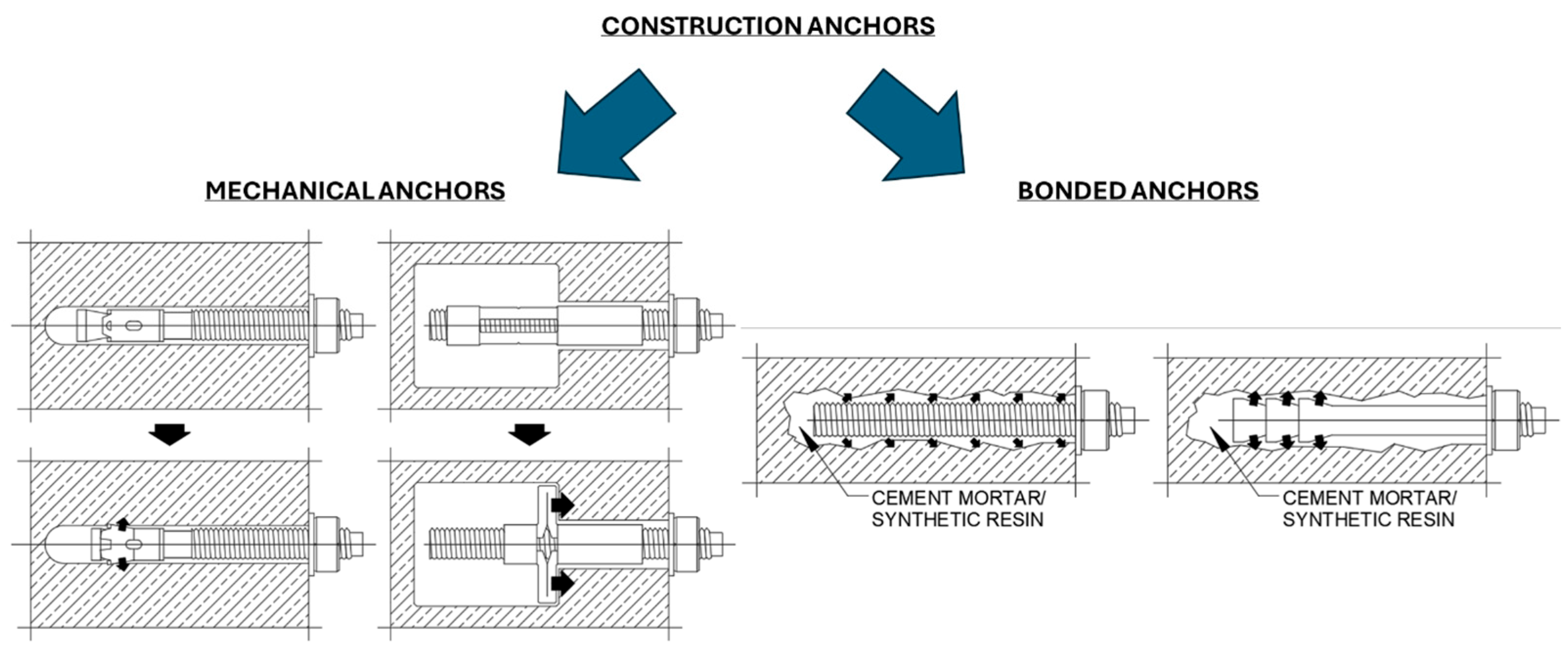

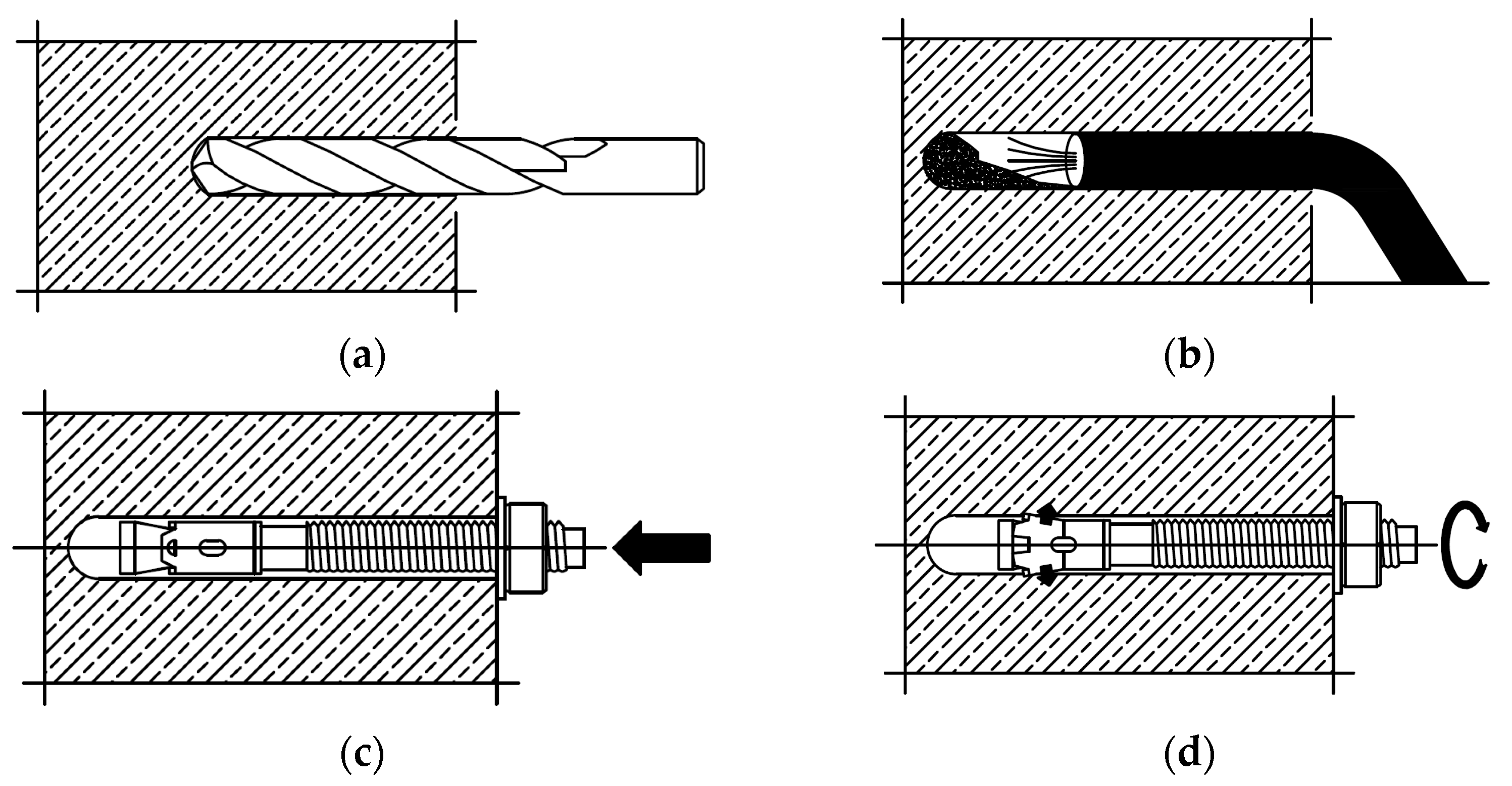

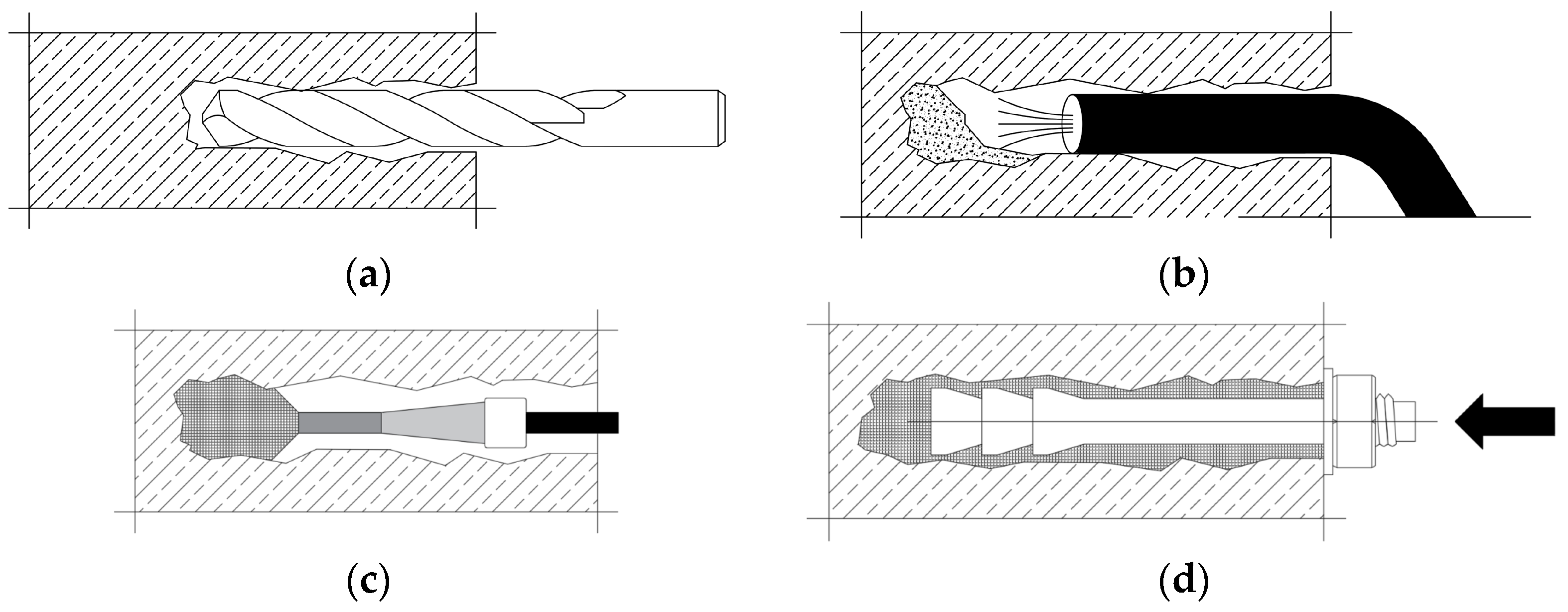

- Chudzik, R. Kotwy Mechaniczne i Kotwy Wklejane—Podział, Zastosowanie, Montaż. Inżynier Budownictwa 2024. Available online: https://inzynierbudownictwa.pl/kotwy-mechaniczne-i-kotwy-wklejane-podzial-zastosowanie-montaz/ (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- EJOT. Heavy-Duty Anchor Guidebook—Part 6: Types of Assembly; EJOT: Bad Berleburg, Germany, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kotwy Chemiczne i Mechaniczne—Jaką Kotwę Wybrać? Available online: https://rawlplug.com/pl/pl/blog/kotwy-chemiczne-i-mechaniczne-jak-dobrac-kotwe?srsltid=AfmBOoo-Xo_dPFCK6VVjgdn5xyoAnwwgnsztkiaMRdrOk4bBWKO1jwb2 (accessed on 7 May 2025).

- De Guzman, S. Chemical Anchors—How They Work, Installation, and Applications. Available online: https://punchlistzero.com/chemical-anchors/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Drobiec, Ł. Wklejanie Prętów Zbrojeniowych Za Pomocą Kotew Chemicznych—Połączenia w Konstrukcjach Żelbetowych. Inżynier Budownictwa 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, Y.; Wang, H.; Guan, Z.; Yang, K. Evaluation of the Properties and Applications of FRP Bars and Anchors: A Review. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2023, 62, 20220287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkurunziza, G.; Debaiky, A.; Cousin, P.; Benmokrane, B. Durability of GFRP Bars: A Critical Review of the Literature. Prog. Struct. Eng. Mater. 2005, 7, 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, F.; Bergmeister, K. FE-Analysis of Long-Term Performance of an Epoxy Bonded Anchor Based on Nanoindentation and CT-Scan. Struct. Concr. 2023, 24, 5086–5101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Z.; Liu, H.; Yan, N.; Wang, Z.; Bai, X.; Han, J.; Mi, C.; Jia, S.; Sun, G.; Zhu, L.; et al. In-Situ Test and Numerical Simulation of Anchoring Performance of Embedded Rock GFRP Anchor. Buildings 2023, 13, 2799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G.; Bai, X.; Sang, S.; Zeng, L.; Yin, J.; Jing, D.; Zhang, M.; Yan, N. Numerical Simulation of Anchorage Performance of GFRP Bolt and Concrete. Buildings 2023, 13, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, N.; Liu, X.; Zhang, M.; Bai, X.; Kuang, Z.; Huang, Y.; Jing, D.; Yan, J.; Li, C.; Wang, Z. Analytical Calculation of Critical Anchoring Length of Steel Bar and GFRP Antifloating Anchors in Rock Foundation. Math. Probl. Eng. 2021, 2021, 7838042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Bai, X.; Yan, N.; Sang, S.; Jing, D.; Chen, X.; Zhang, M. Load Transfer Law of Anti-Floating Anchor With GFRP Bars Based on Fiber Bragg Grating Sensing Technology. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 849114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, G.; Zornberg, J.G.; Morsy, A.M.; Huang, J. Interface Bond Behavior of Tensioned Glass Fiber-Reinforced Polymer (GFRP) Tendons Embedded in Cemented Soils. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 263, 120132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, A. Glassfiberbolt (GFRP) Som Permanent Sikringsbolt; Minova: Greenwood Village, CO, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ozbakkaloglu, T.; Fang, C.; Gholampour, A. Influence of FRP Anchor Configuration on the Behavior of FRP Plates Externally Bonded on Concrete Members. Eng. Struct. 2017, 133, 133–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, Y.; Zhang, S.S.; Smith, S.T.; Yu, T. Novel Embedded FRP Anchor for RC Beams Strengthened in Flexure with NSM FRP Bars: Concept and Behavior. J. Compos. Constr. 2023, 27, 04022093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carozzi, F.G.; Colombi, P.; Fava, G.; Poggi, C. Mechanical and Bond Properties of FRP Anchor Spikes in Concrete and Masonry Blocks. Compos. Struct. 2018, 183, 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, K.; Gao, Y.; Yang, S.; Yang, Z.; Jiang, J. Experimental Investigation and Analytical Prediction on Bond Behaviour of CFRP-to-Concrete Interface with FRP Anchors. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2023, 19, e02510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Rey Castillo, E.; Kanitkar, R. Effect of FRP Spike Anchor Installation Quality and Concrete Repair on the Seismic Behavior of FRP-Strengthened RC Columns. J. Compos. Constr. 2021, 25, 04020085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronkay, F.; Czigány, T. Development of Composites with Recycled PET Matrix. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2006, 17, 830–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldi, A.L.F.D.M.; Bartoli, J.R.; Velasco, J.I.; Mei, L.H.I. Glass Fibre Recycled Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate) Composites: Mechanical and Thermal Properties. Polym. Test. 2005, 24, 507–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondadori, N.M.L.; Nunes, R.C.R.; Zattera, A.J.; Oliveira, R.V.B.; Canto, L.B. Relationship between Processing Method and Microstructural and Mechanical Properties of Polyethylene Terephthalate/Short Glass Fiber Composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2008, 109, 3266–3274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cantwell, W.J. Fracture Behavior of Glass Fiber/Recycled PET Composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 1999, 18, 373–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kráčalík, M.; Pospíšil, L.; Šlouf, M.; Mikešová, J.; Sikora, A.; Šimoník, J.; Fortelný, I. Effect of Glass Fibers on Rheology, Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Recycled PET. Polym. Compos. 2008, 29, 915–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monti, M.; Scrivani, M.T.; Kociolek, I.; Larsen, Å.G.; Olafsen, K.; Lambertini, V. Enhanced Impact Strength of Recycled PET/Glass Fiber Composites. Polymers 2021, 13, 1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arabaci, H.; Özkan, N. Environmental and Economic Benefits of Recycling PET Bottles. Balk. Near East. J. Soc. Sci. 2023, 9, 119–125. [Google Scholar]

- University of Portsmouth Breakthrough in Enzymatic Plastic Recycling Cuts Costs and Emissions. Available online: https://www.newswise.com/articles/breakthrough-in-enzymatic-plastic-recycling-cuts-costs-and-emissions (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- 265,000 Jobs Created by PET. Available online: https://positivelypet.org/economic-impact/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- What Are the Economic Benefits of PET Bottle Recycling? Available online: https://jbpolypack.com/the-economic-benefits-of-pet-bottle-recycling/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Chandler, D.L. How to Increase the Rate of Plastics Recycling. MIT News, 3 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Detailed Overview and Results of the Current Deposit Return Scheme Implementations in Europe. Available online: https://sensoneo.com/waste-library/deposit-return-schemes-overview-europe/ (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Bassi, S.A.; Tonini, D.; Saveyn, H.; Astrup, T.F. Environmental and Socioeconomic Impacts of Poly(Ethylene Terephthalate) (PET) Packaging Management Strategies in the EU. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 501–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMARC. Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Prices, Trend, Chart, Demand, Market Analysis, News, Historical and Forecast Data Report; 2025 ed.; IMARC: Sydney, Australia, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- ALPLA. Study Confirms the Excellent Carbon Footprint of Recycled PET; ALPLA: Hard, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- CHEMANALYST. Track R-PET Price Trend And Forecast In Top Leading Countries Worldwide; CHEMANALYST: New York, NY, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Businessanalytiq. Prices Indexes RPET Price Index; Businessanalytiq: Singapore, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 15686-5; Buildings and Constructed Assets—Service Life Planning Part 5: Life-Cycle Costing. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Salem, A.; Waleed, A.; Fatima, S.S.S.A.; Ghdayra, O.A.M.A.; Kaouthar, M.; Khaled, A.S.; Yahia, A.B. Process to Recycle and Produce PET/Carbon Fiber Composite. U.S. Patent 12,043,725, 23 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Emil, G. PET Fiber-Rubber Composite and Tire. Japan Patent WO/2024/070779, 4 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, T.; Ouyang, W.; Feng, Y. Elastic Composite Fiber and Fabrication Method Therefor. U.S. Patent 12,043,923, 23 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- EN 1992-4; Design of Concrete Structures—Part 4: Design of Fastenings for Use in Concrete. Würth Group: Künzelsau, Germany, 2021.

- Fuchs, W.; Eligehausen, R.; Hofmann, J. Bemessung Der Verankerung von Befestigungen in Beton: EN 1992-4, Der Neue Eurocode 2, Teil 4. Beton Stahlbetonbau 2020, 115, 36–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ETAG 001; Guideline for European Technical Approval of Metal Anchors for Use in Concrete. EOTA: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2013.

- EAD 330499-00-0601; Bonded Fasteners for Use in Concrete. EOTA: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2017.

- EAD 330232-01-0601; Mechanical Fasteners for Use in Concrete. EOTA: Bruxelles, Belgium, 2019.

- ACI 318-11; Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete. ACI: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2011.

- AC308; Acceptance Criteria for Post-Installed Adhesive Anchors in Concrete Elements. ACI: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2016.

- ASTM-F1554-2017; Anchor-Bolt. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- ACI 318-14; Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete and Commentary. ACI: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2014.

- Mahrenholtz, C.; Sharma, A. Qualification and Design of Anchor Channels with Channel Bolts According to the New EN 1992-4 and ACI 318. Struct. Concr. 2020, 21, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabantsev, O.; Kovalev, M. Behavior of Anchors Embedded in Concrete Damaged by the Maximum Considered Earthquake: An Experimental Study. Buildings 2023, 13, 2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glass Fiber Reinforced Polymer (GFRP) Market. Available online: https://www.metastatinsight.com/report/glass-fiber-reinforced-polymer-gfrp-market (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Szumigała, M.; Pawłowski, D. Zastosowanie Kompozytowych Prętów Zbrojeniowych w Konstrukcjach Budowlanych. Przegląd Bud. 2014, 3, 47–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rduch, A.; Rduch, Ł.; Walentyński, R. Właściwości i Zastosowanie Kompozytowych Prętów Zbrojeniowych. Przegląd Bud. 2017, 11, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- ACI 440.1R-15; Guide for the Design and Construction of Structural Reinforced with Fiber-Reinforced Polymer(FRP) Bars. ACI: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2015.

- ACI 440.3R-04; Guide Test Methods for Fiber-Reinforced Polymers (FRPs) for Reinforcing or Strengthening Concrete Structures. ACI: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2017.

- FIB Bulletin 40. FRP Reinforcment in RC Structures; FIB: Lausanne Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 10406-1; Fibre-Reinforced Polymer (FRP) Reinforcement of Concrete—Test Methods Part 1: FRP Bars and Grids. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- ASTM WK87882; New Specification for Carbon Fiber Reinforced Polymer (FRP) Bars and Strands for Concrete Reinforcement. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2023.

- Siwowski, T. Mosty z Kompozytów FRP: Kształtowanie Projektowanie Badania; Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2018; Volume I. [Google Scholar]

- Nanni, A.; De Luca, A.; Jawaheri Zadeh, H. Reinforced Concrete with FRP Bars: Mechanics and Design; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- ACI 440.1R-06; Guide for the Design and Construction of Structural Concrete Reinforced with FRP Bars. ACI: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2006.

- ASTM D7205/D7205M-21; Standard Test Method for Tensile Properties of Fiber Reinforced Polymer Matrix Composite Bars. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021.

- ASTM D7617/D7617M-11; Standard Test Method for Transverse Shear Strength of Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Matrix Composite Bars. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2017.

- R-STUDC Pręt Zbrojeniowy Kompozytowy. 2024.

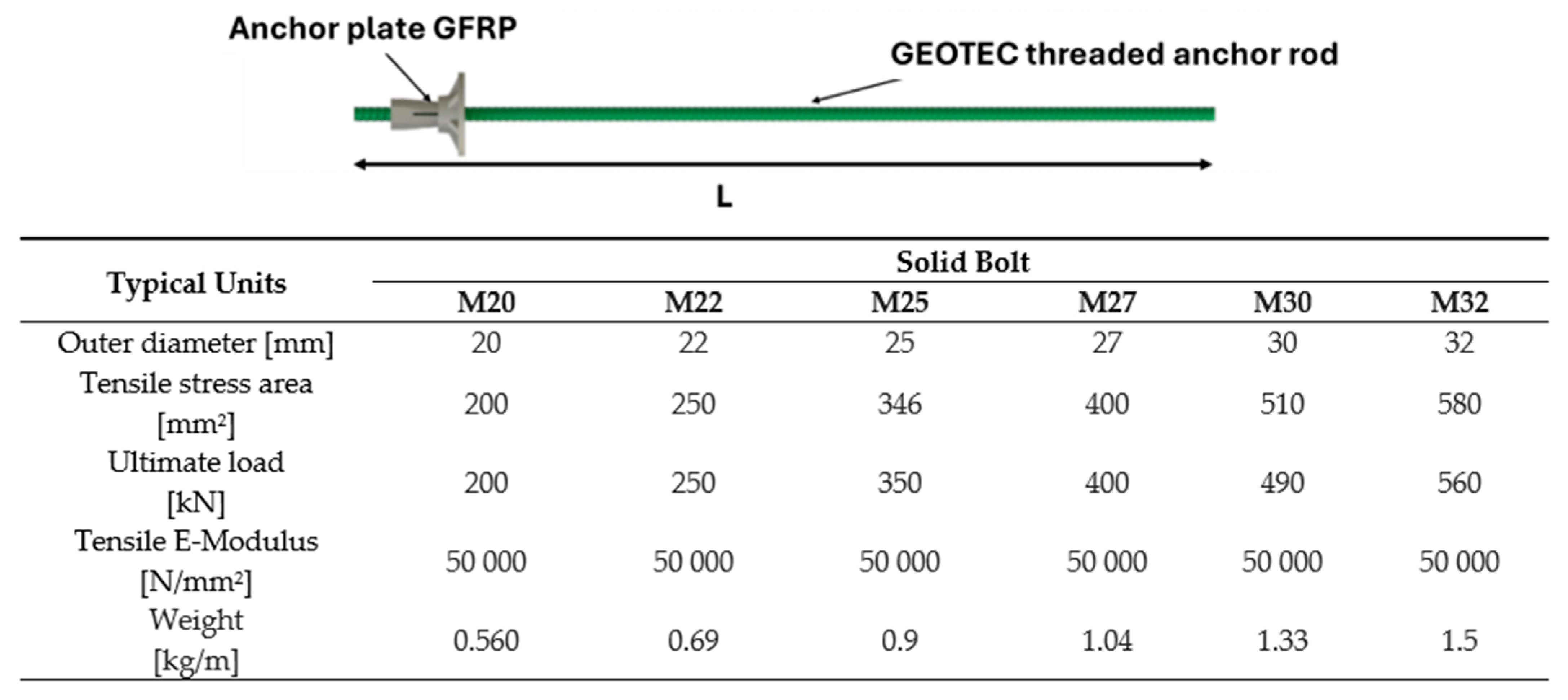

- Nordic Geo Support. Available online: https://nordicgeosupport.com/about-us/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Hollow Bar GFRP Bolting Technologies for Sustainability. Technical Data Sheet, Nordic Geo Support 2021. Available online: https://usercontent.one/wp/nordicgeosupport.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/NGS-GFRP-Hollow-Bolts.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Solid Bar GFRP Bolting Technologies for Sustainability. Technical Data Sheet, Nordic Geo Support 2021. Available online: https://usercontent.one/wp/nordicgeosupport.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/NGS-GFRP-Solid-Bolts.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Life-Cycle Assessments of Rock Bolts. Tunn. J. 2017, 46–49. Available online: https://usercontent.one/wp/nordicgeosupport.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/LCA-for-rock-bolts-TJ-2017.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- GFRP and Composite Bolting Technologies. Available online: https://nordicgeosupport.com/anchors-bolts-gfrp-composites/ (accessed on 14 March 2025).

- GFRP and Composite Bolting Technologies For Sustainability. Available online: https://usercontent.one/wp/nordicgeosupport.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/0000-21-NGS-GFRP-Overview.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- Spec Sheet GFPR System Glass Fiber Reinforced Polymer (GFRP) System, DYWIDAG. Available online: https://assets.ctfassets.net/wz1xpzqb46pe/3SPOWJGYcia9RsBNSWcloI/e7ad07942c87a2fa9e265cbdfbef7e92/220428_Product_Guide_GFRP_System_Tunneling_A4_EN_Web_uplbynder.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2025).

- GFRP FRP GFRP Self Drilling Rock Bolt/Self Drilling Anchor Bolt. Available online: https://www.tradewheel.com/p/gfrp-frp-gfrp-self-drilling-rock-931225/ (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- FRP Bolts/Fiber Reinforced Plastics Bolts/Gfrp Anchor Rock Bolts. Available online: https://chinainsulation.en.made-in-china.com/product/lSNxqKaUggYP/China-FRP-Bolts-Fiber-Reinforced-Plastics-Bolts-Gfrp-Anchor-Rock-Bolts.html (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Garford GRP/GFRP Bolts. Available online: https://www.garforduk.com/garford-gfrp-bolts.html (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- NANTONG HUYU Kołki Rozporowe GFRP. Available online: http://pl.huyufrp.com/gfrp-insulation-connectors/gfrp-pins-for-security-anchor-systems.html (accessed on 18 December 2024).

- Projektuj Efektywniej! FIXPERIENCE—Innowacyjne Rozwiązanie. Inżynier Budownictwa 2014.

- Adamczyk, A. Przykłady Normowe a Rzeczywiste Przypadki Projektowe. Program EuroZłącza. Inżynier Budownictwa 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Anchors | - Instant load - Possibility of through-mounting, which speeds up installation time - Opportunity for temporary installation - Cheaper than chemical anchors - Installation is less demanding compared to chemical anchors | - Not suitable for hollow and masonry substrates - They expand the substrate (cannot be installed close to other anchors or near edges) - May be subject to corrosion - Cannot be installed in wet substrates or in any chemical conditions |

| Bonded Anchors | - High load-bearing capacity and the possibility of deep anchoring. - Possibility of installation to substrates of any type (hollow block, rock, wood, composite). - Resistant to dynamic type of load (to vibration and oscillation). - Small distance between anchors and smaller anchor distance from the edge - Can be used for damp, wet and flooded substrates | - The installation of chemical anchor is more complicated - They cannot be loaded immediately after application - They require special accessories for application - Are not subject to disassembly, so they are also not suitable for temporary installation. - Need to be installed under established thermal conditions |

| Key Words | Number of Occurrences of the Phrase (Scopus) |

|---|---|

| STEP I | |

| anchor | 109,647 |

| concrete | 620,817 |

| PET | 262,485 |

| FRP | 31,057 |

| STEP II | |

| anchor + PET | 173 |

| Concrete + anchor | 7221 |

| FRP + anchor | 782 |

| FRP + PET | 177 |

| Concrete + PET | 1391 |

| STEP III | |

| FRP + anchor + concrete | 628 |

| FRP + anchor + PET | 3 |

| STEP IV | |

| FRP + anchor + concrete + PET | 3 |

| Fiber Content | Tensile Strength [MPa] | Flexural Modulus [GPa] | Impact Strength [kJ/m2] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ronkay & Czigany [22] | 15%, 30%, 45% | 55.86–84.05 | 2.29–9.96 | 4.23–7.88 kJ/m2 |

| Kráčalík et al. [26] | 15%, 20%, 30% | 110–121.7 | 7.9–12.65 | 32–43.3 kJ/m2 |

| Monti et al. [27] | 20% | 102–120 | - | 5.2–8.4 kJ/m2 (notched), 26.4–40.3 kJ/m2 (unnotched) |

| Giraldi et al. [23] | 20%, 30%, 40% | - | 7.8—9.2 | 76.9–108.9 J/m2 |

| Types | CAPEX (Index) | OPEX (100 Years) | User (100 Years) | EoL | Sum NPV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFRP bars | 100 | 95–100 | 90–100 | 95–100 | 100 (ref.) |

| BFRP bars | 105–115 | 95–100 | 90–100 | 95–100 | 102–110 |

| CFRP bars | 180–260 | 90–100 | 80–95 | 95–100 | 95–120 |

| rPET + GF/CF bars | 90–130 | 100–120 | 95–110 | 95–105 | 110–140 |

| Density [kg/m3] | Tensile Strength [MPa] | Tensile Modulus [GPa] | Ultimate Tensile Strain [%] | CTE [10−6/F] | Poisson’s Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E-glass | 2500 | 3447 | 72.5 | 2.4 | 0.15 | 0.22 |

| S-glass | 2500 | 4550 | 85.5 | 3.3 | 0.086 | 0.22 |

| AR-glass | 2255 | 1793 ÷ 3447 | 69.6 ÷ 75.8 | 2.0 ÷ 3.0 | N/A | N/A |

| High modulus carbon | 1952 | 2482 ÷ 3998 | 349.6 ÷ 650.2 | 0.5 | −0.036 ÷ −0.059 | 0.2 |

| Low modulus carbon | 1750 | 3496 | 239.9 | 1.1 | −0.018 ÷ −0.059 | 0.2 |

| Aramid (Kevlar 29) | 1440 | 2758 | 62.1 | 4.4 | −0.059 log. (1.7 radial) | 0.35 |

| Aramid (Kevlar 49) | 1440 | 3620 | 124.1 | 2.2 | −0.059 log. (1.7 radial) | 0.35 |

| Aramid (Kevlar 149) | 1440 | 3447 | 175.1 | 1.4 | −0.059 log. (1.7 radial) | 0.35 |

| Basalt | 2800 | 4826 | 88.9 | 3.1 | 0.24 | N/A |

| Density [kg/m3] | Tensile Strength [MPa] | Longitudinal Modulus [GPa] | Poisson’s Ratio | CTE [10−6/F] | Glass Transition Temperature [F] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epoxy | 1187 ÷ 1424 | 34.5 ÷ 103.4 | 2.07 ÷ 3.45 | 0.35 ÷ 0.39 | 1.6 ÷ 3.0 | 203 ÷ 347 |

| Polyester | 1187 ÷ 1424 | 48.3 ÷ 131 | 2.76 ÷ 4.14 | 0.38 ÷ 0.40 | 1.3 ÷ 1.9 | 158 ÷ 212 |

| Vinyl ester | 1127 ÷ 1365 | 68.9 ÷ 75.8 | 3.0 ÷ 3.45 | 0.36 ÷ 0.39 | 1.5 ÷ 2.2 | 158 ÷ 329 |

| Density [kg/m3] | CTE Longitudinal [10−6/F] | CTE Transverse [10−66/F] | Tensile Strength [MPa] | Tensile Modulus [GPa] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFRP | 3630 ÷ 6110 | 0.098 ÷ 0.17 | 0.35 ÷ 0.40 | 70 ÷ 230 | 5.1 ÷ 7.4 |

| CFRP | 4350 ÷ 4670 | −0.19 ÷ 0.0 | 1.2 ÷ 1.7 | 87 ÷ 535 | 15.9 ÷ 84.0 |

| AFRP | 3630 ÷ 4110 | −0.097 ÷ −0.32 | 0.99 ÷ 1.3 | 250 ÷ 368 | 6.0 ÷ 18.2 |

| Conditions of Exposure | Type of Synthetic Fibers | |

|---|---|---|

| Concrete not exposed to soil and weathering | Carbon | 1.0 |

| Glass | 0.8 | |

| Aramid | 0.9 | |

| Concrete exposed to earth and weathering | Carbon | 0.9 |

| Glass | 0.7 | |

| Aramid | 0.8 |

| Manufacturer | Polymer Type | Primary Application | Ultimate Load [kN] | Additional Properties |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STUDC | GFRP | Tunnels, mining | – | Alkali resistance |

| Nordic Geo Support | GFRP | Tunnels, mining | 200–3550 (range R25–T103 bars) | Corrosion-resistant, lightweight, electrically insulated |

| DYWIDAG | GFRP | Soil nails | up to 1280 (3-bar/4-bar system) | Alkali resistance |

| Shanxi Chengxinda Mining Equipment | BFRP/GFRP | Mining | – | Alkali resistance |

| XINCHENG Insulation | GFRP | Bolts, façade | capacity depends on diameter; tensile >600 MPa | – |

| Garford | GFRP | Façade | – | GFRP bolts available (no specific loads found) |

| Nantong Huyu | GFRP | fasade | 100–750 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Ostrowski, K.A.; Piechaczek, M. Composite Bonded Anchor—Overview of the Background of Modern Engineering Solutions. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010187

Ostrowski KA, Piechaczek M. Composite Bonded Anchor—Overview of the Background of Modern Engineering Solutions. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):187. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010187

Chicago/Turabian StyleOstrowski, Krzysztof Adam, and Marcin Piechaczek. 2026. "Composite Bonded Anchor—Overview of the Background of Modern Engineering Solutions" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010187

APA StyleOstrowski, K. A., & Piechaczek, M. (2026). Composite Bonded Anchor—Overview of the Background of Modern Engineering Solutions. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 187. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010187