Enhancing Precise Point Positioning Under Active Ionosphere Using Wide-Range Ionospheric Corrections Derived from MADOCA Service

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Dual-Frequency Un-Combined PPP Model

2.2. MADOCA-PPP Wide-Range Ionosphere Correction Model

3. Data and Strategy

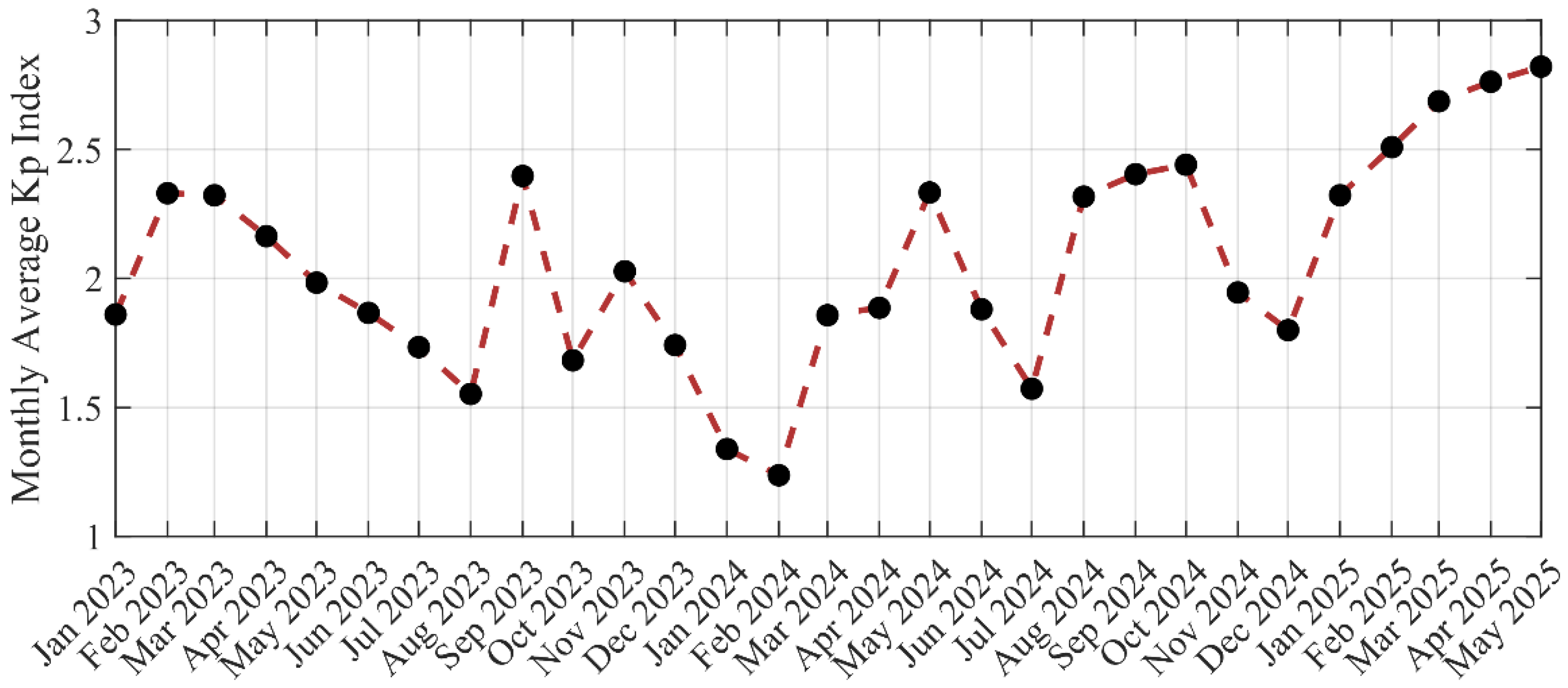

3.1. Data Collection

3.2. Processing Strategy

4. Results and Analysis

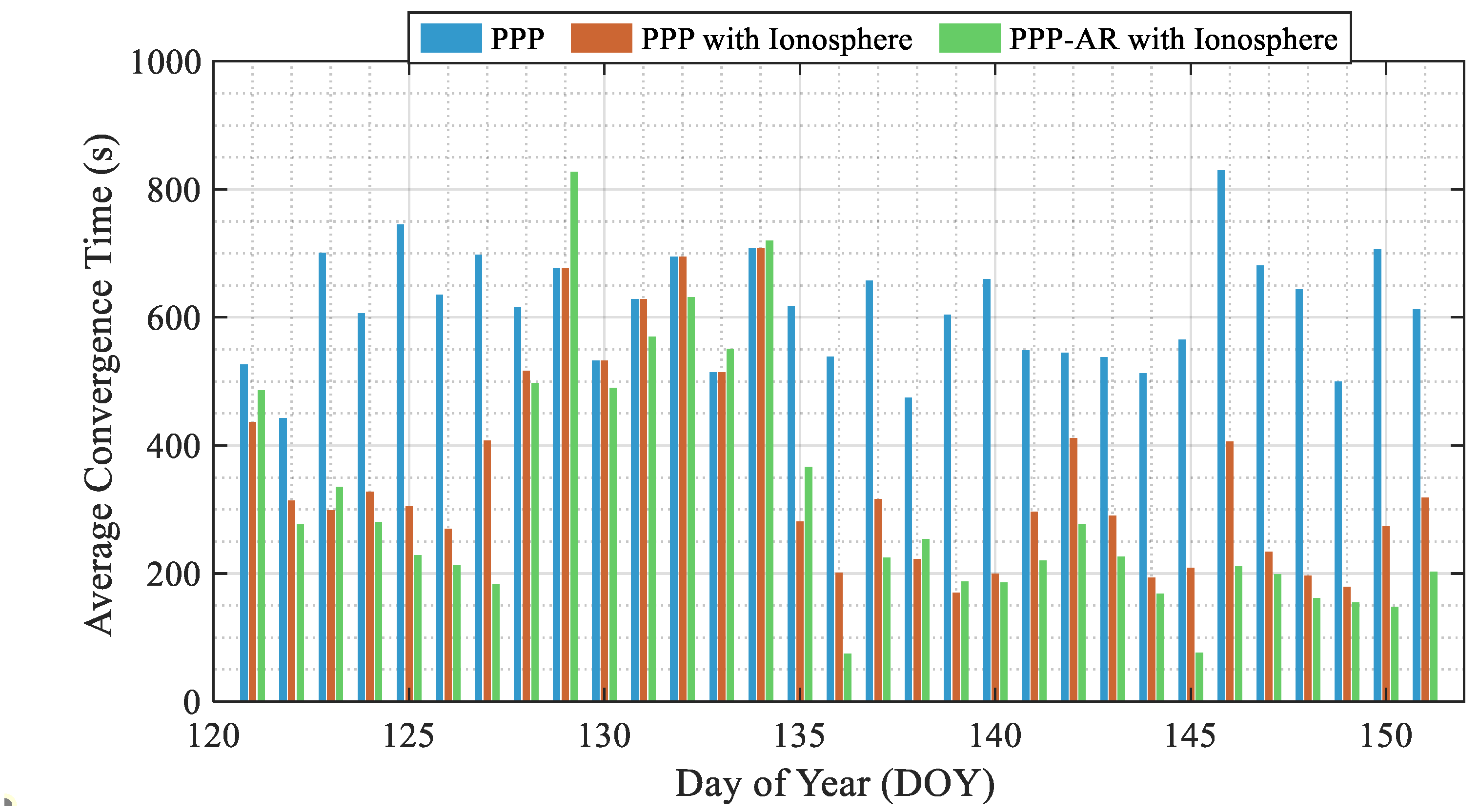

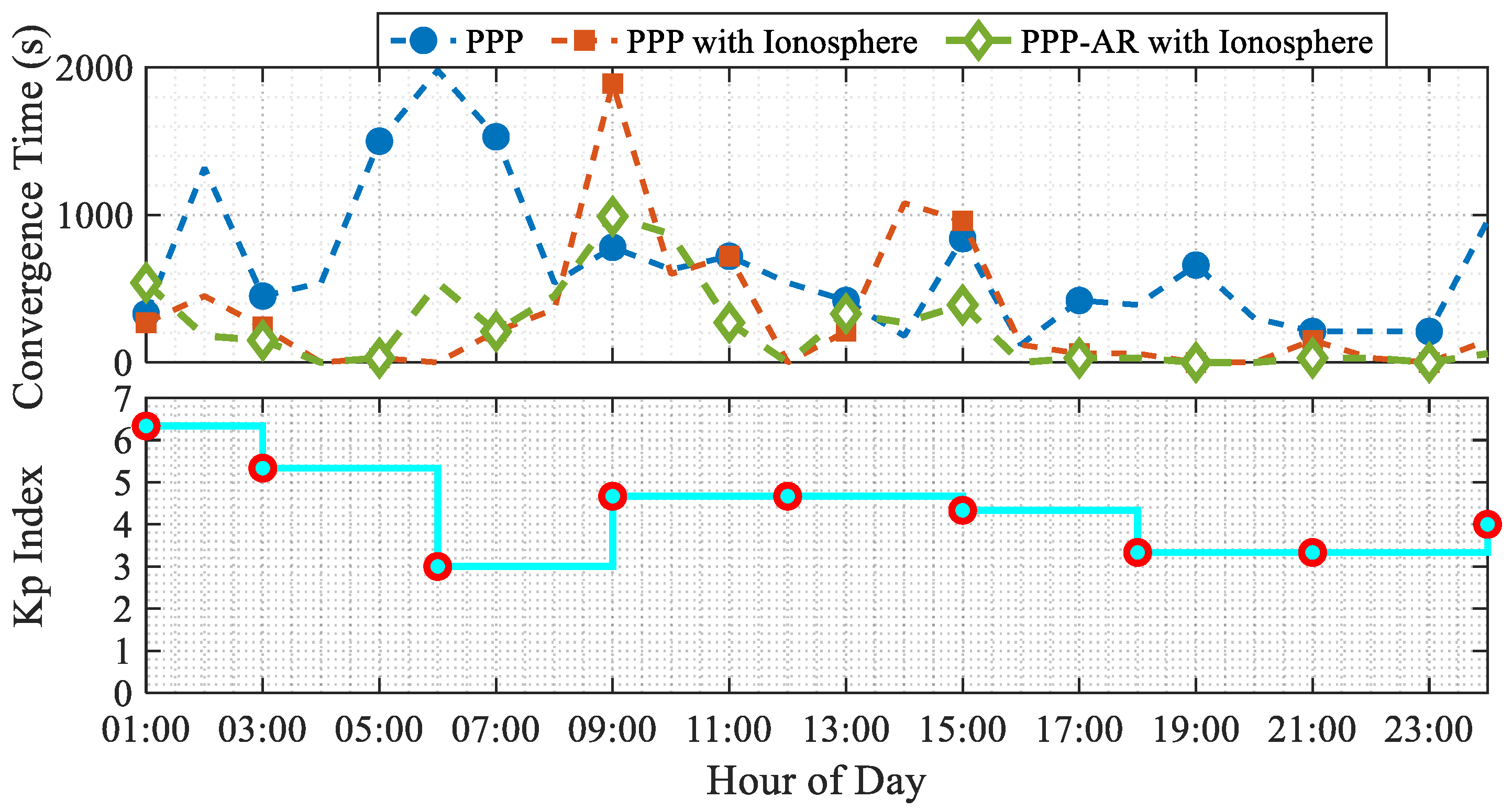

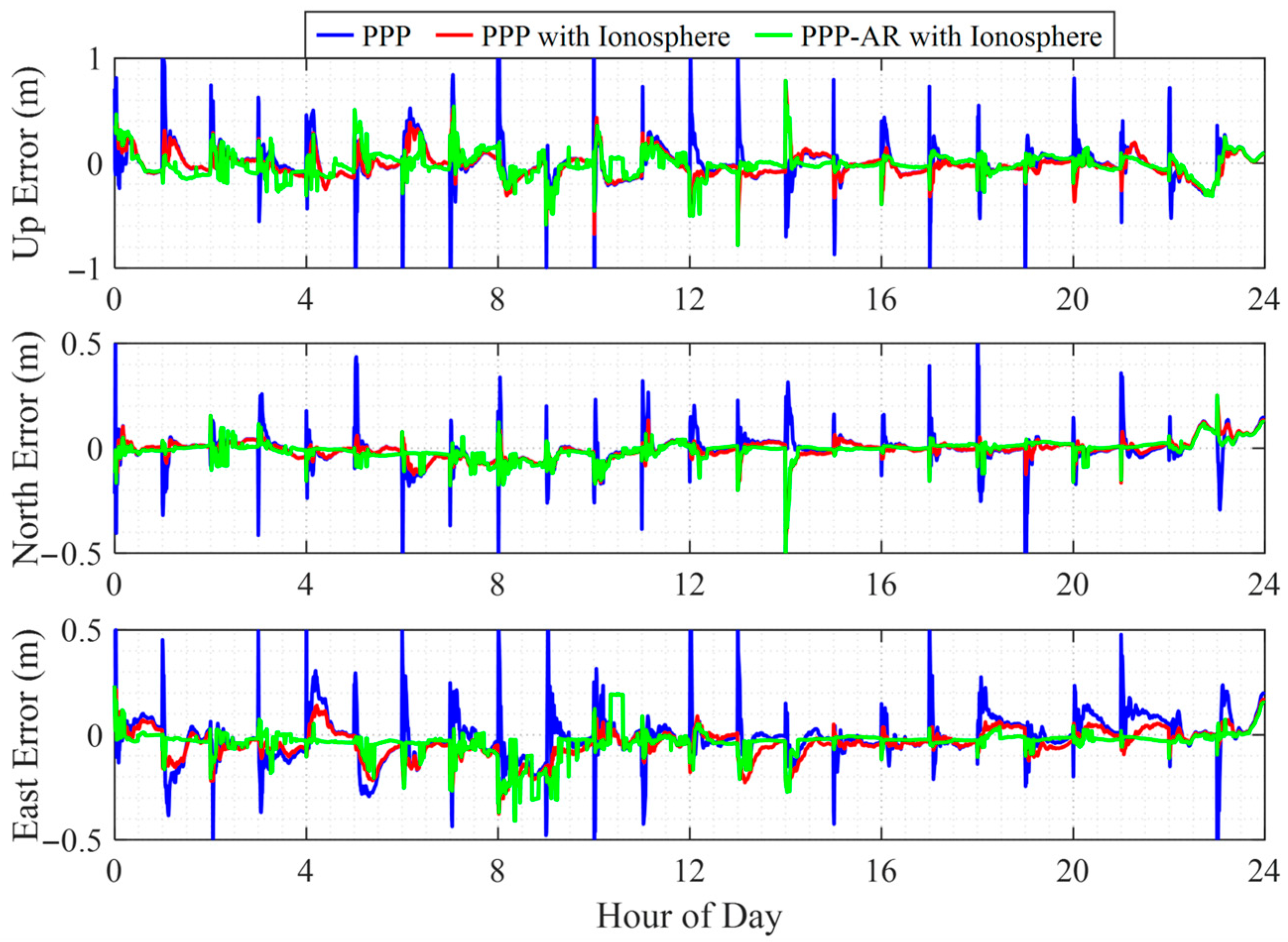

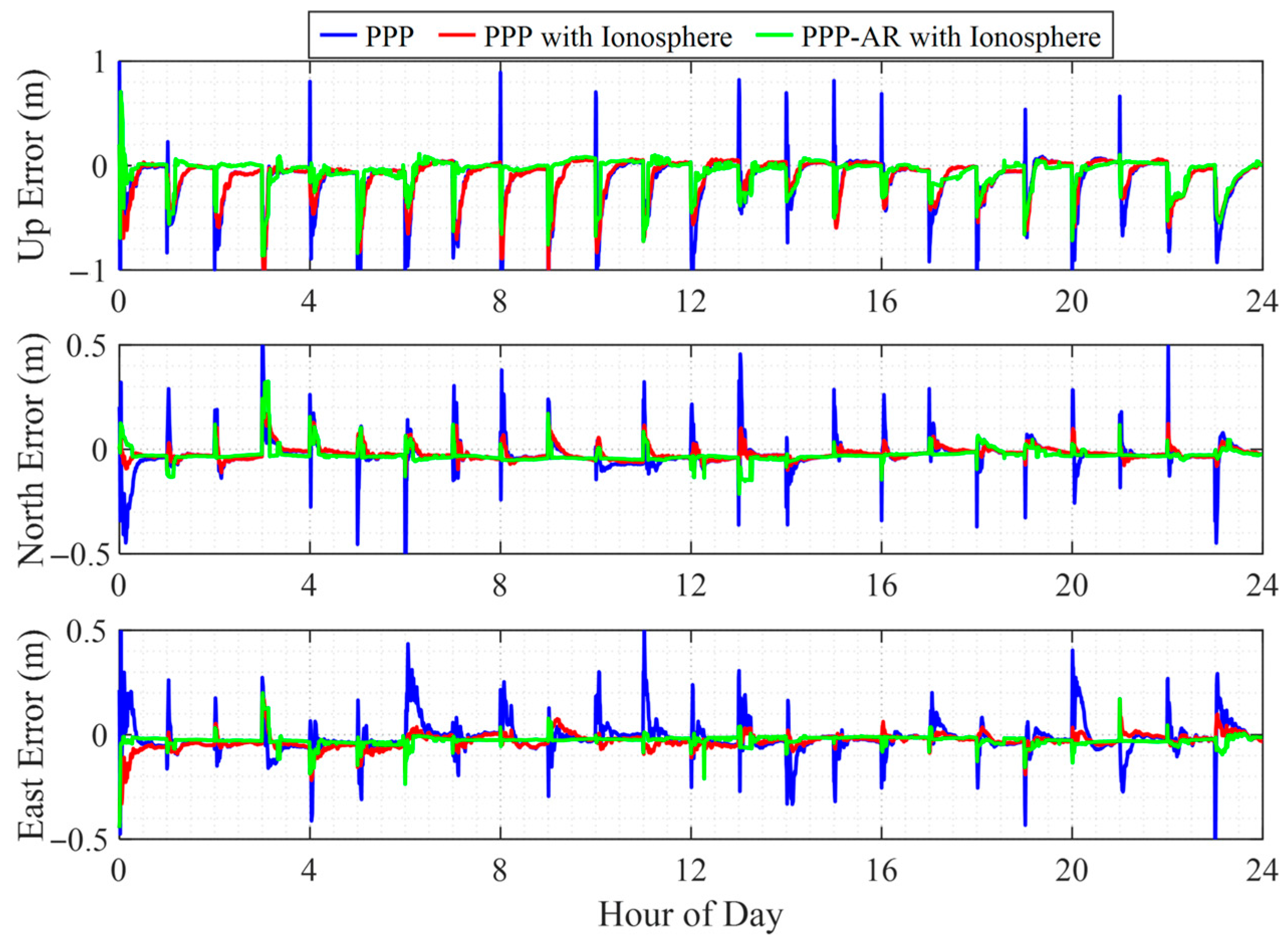

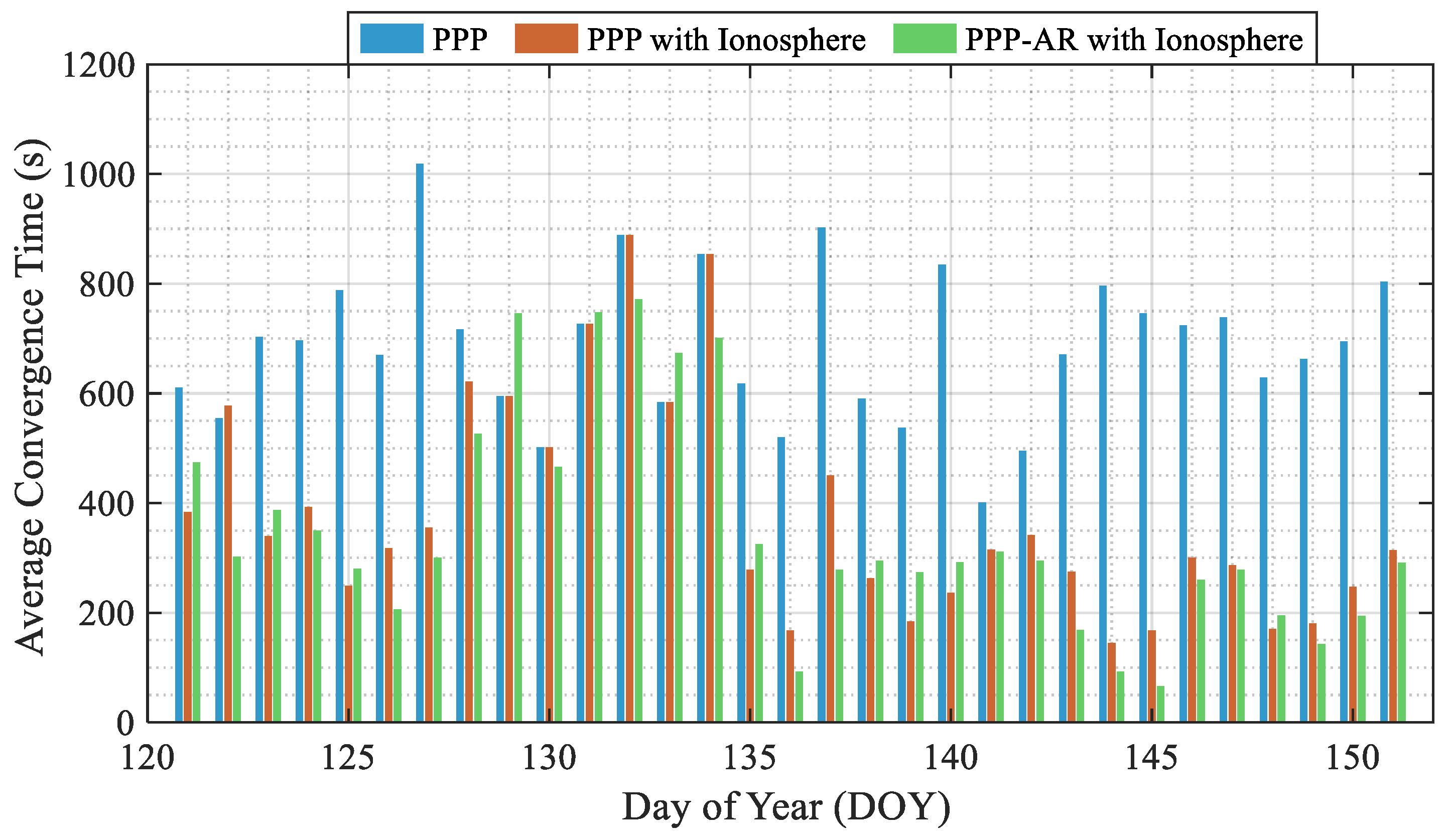

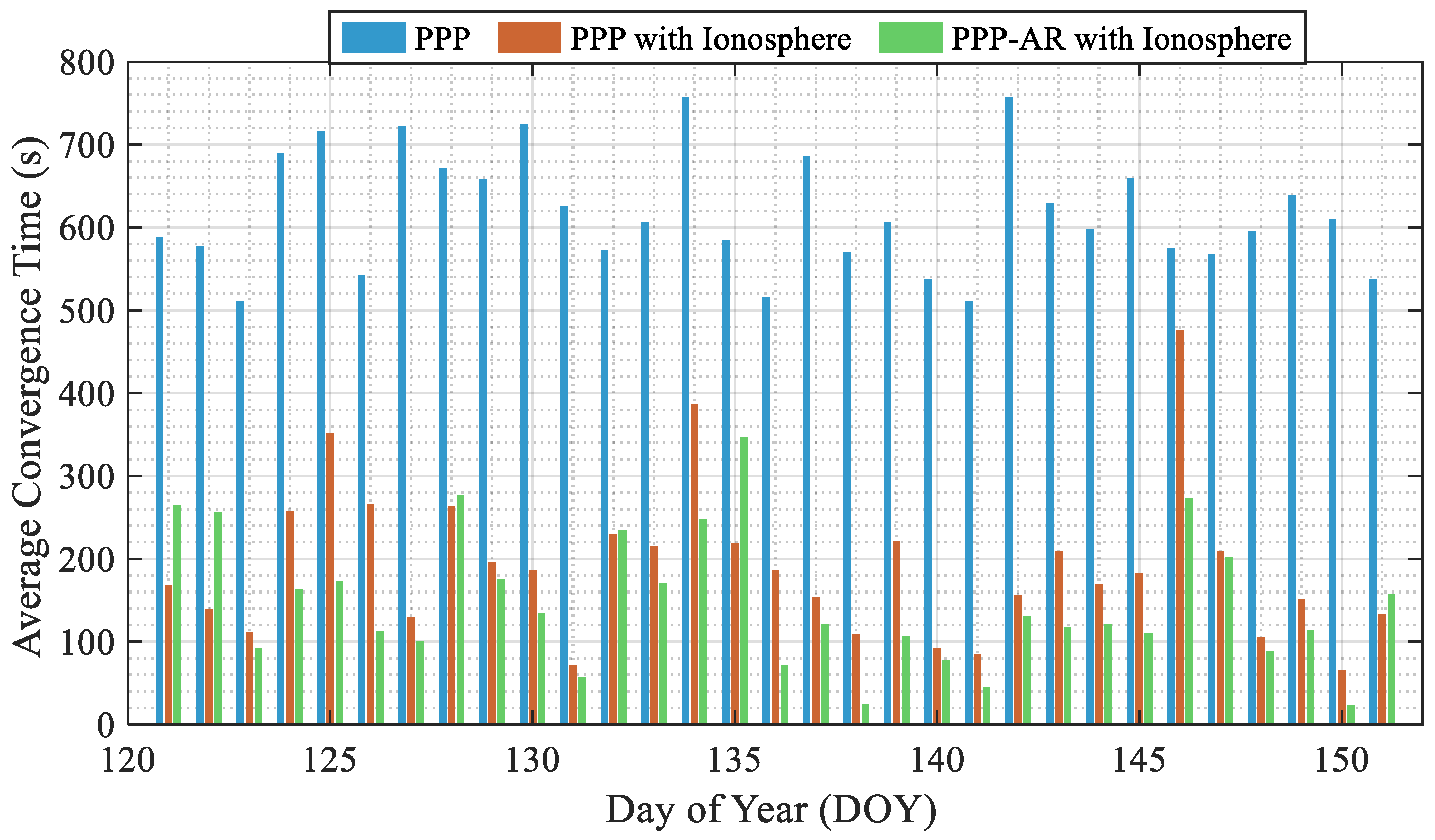

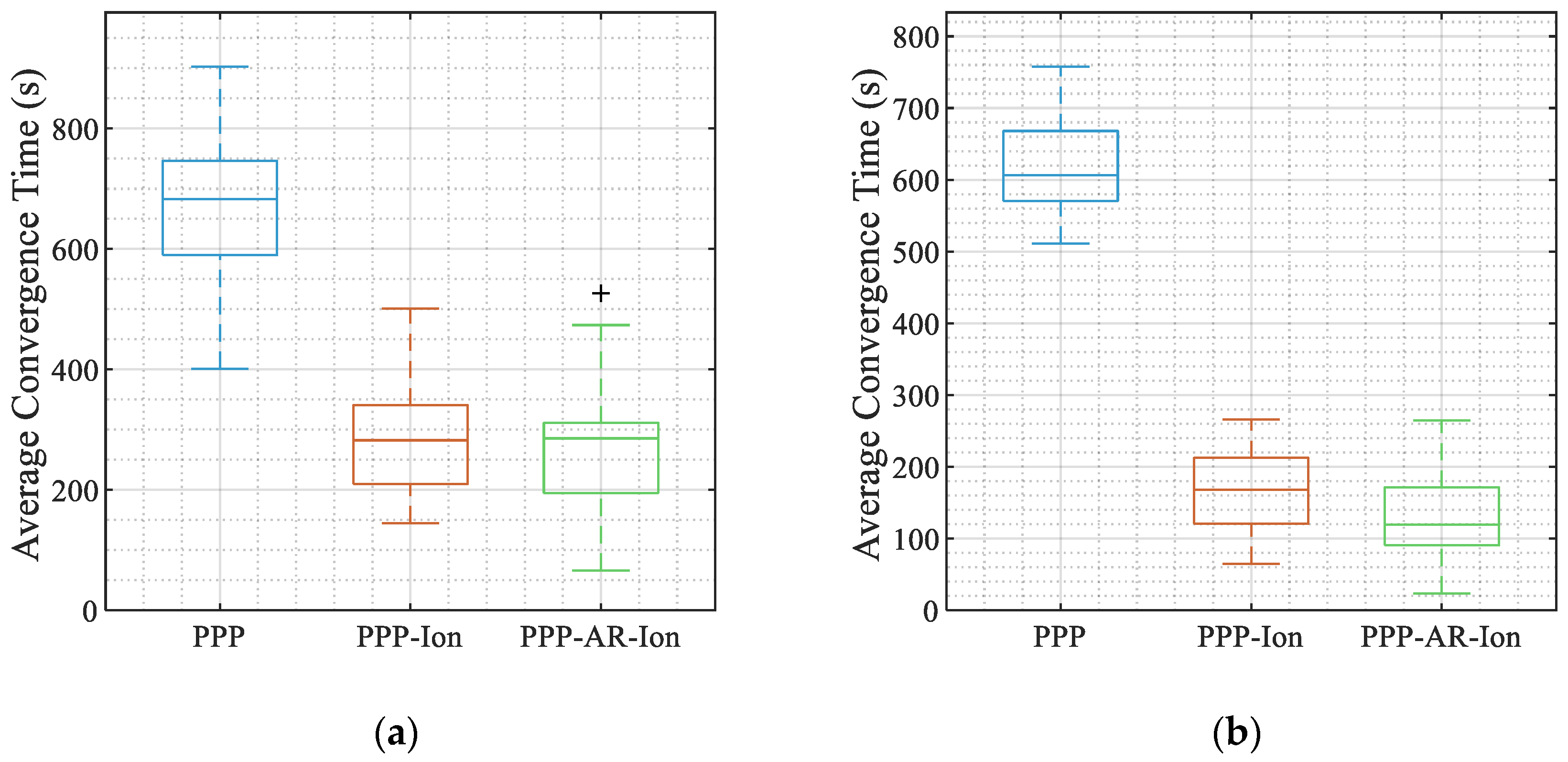

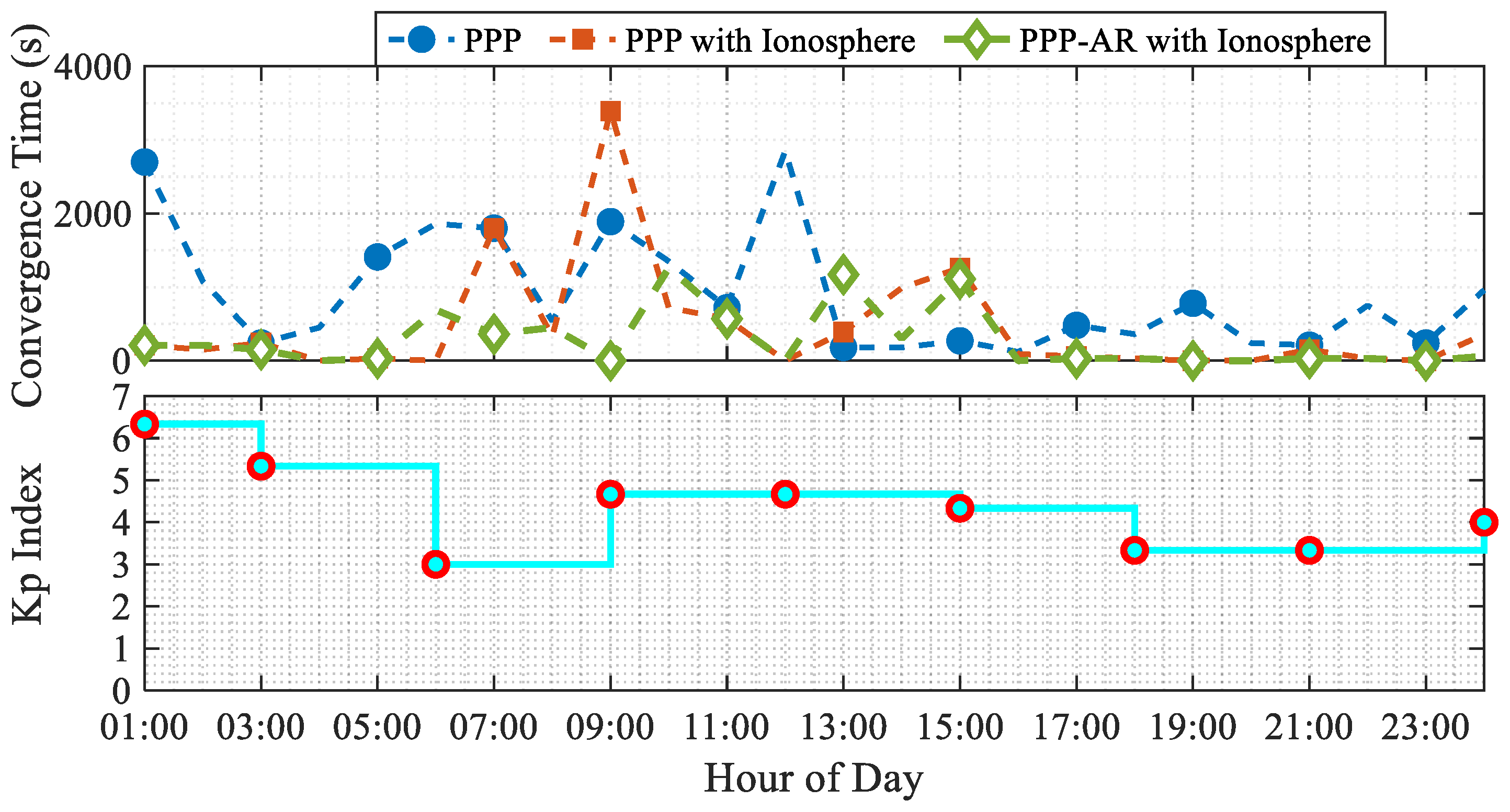

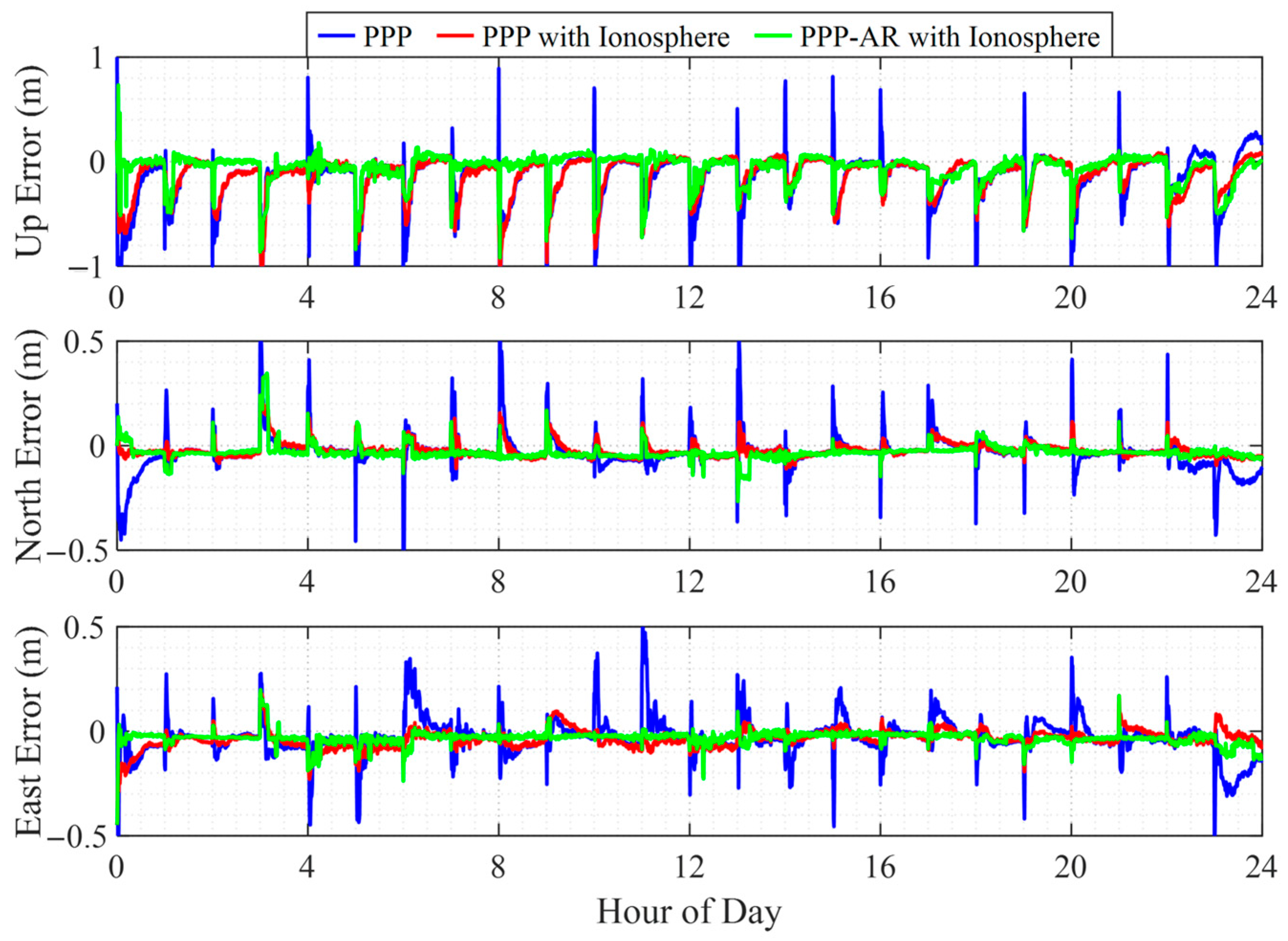

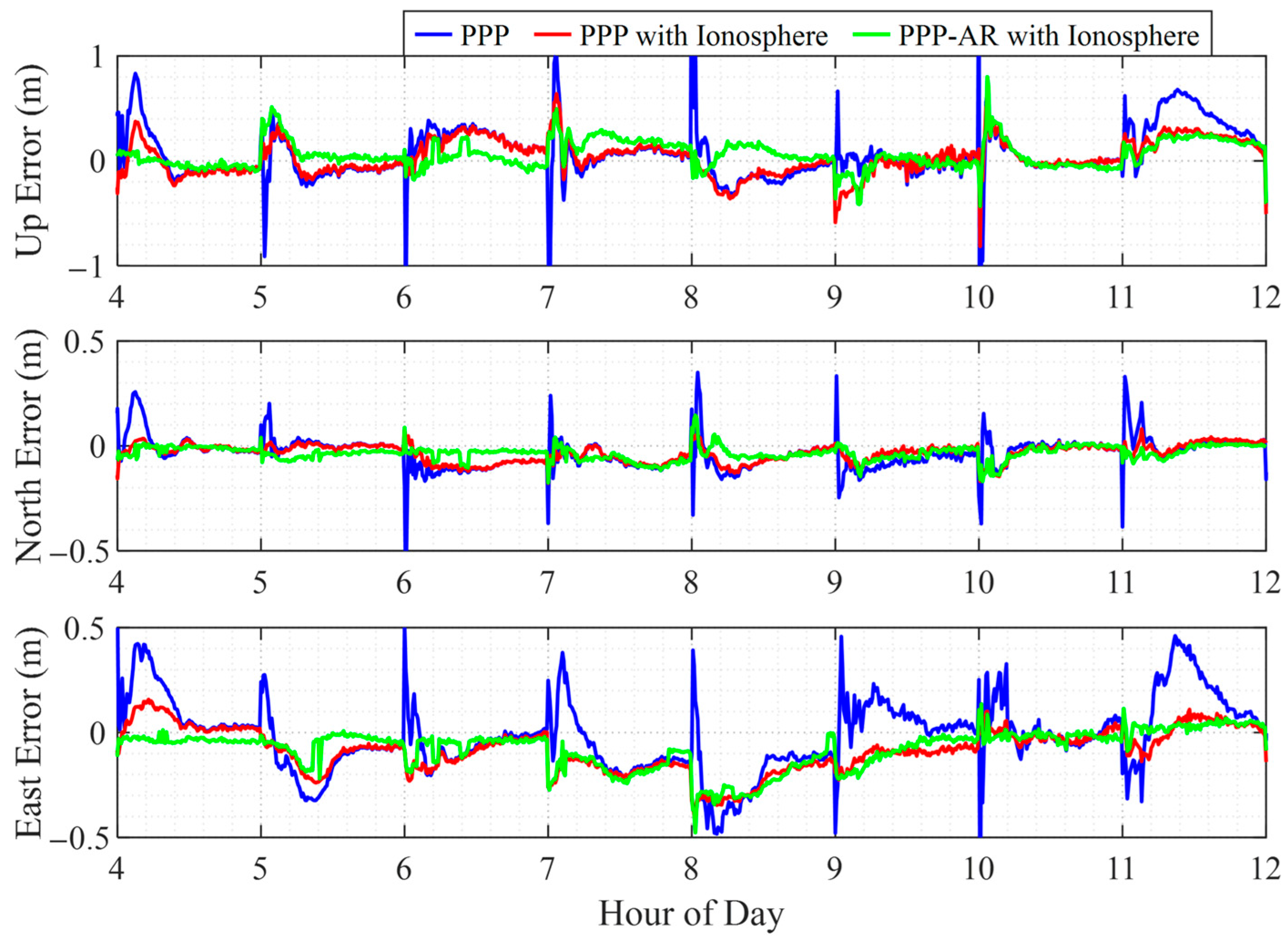

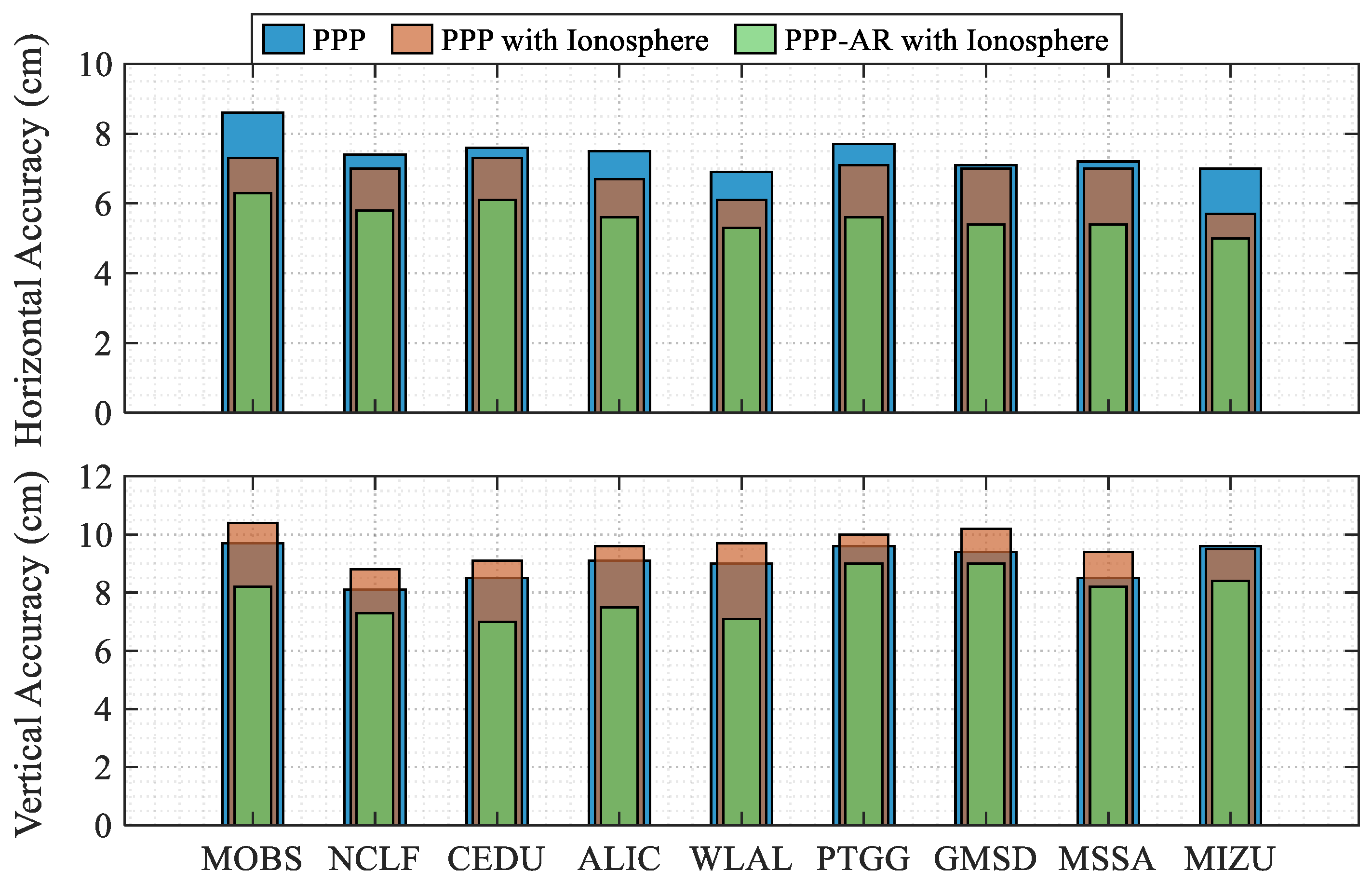

4.1. Static Positioning Performance

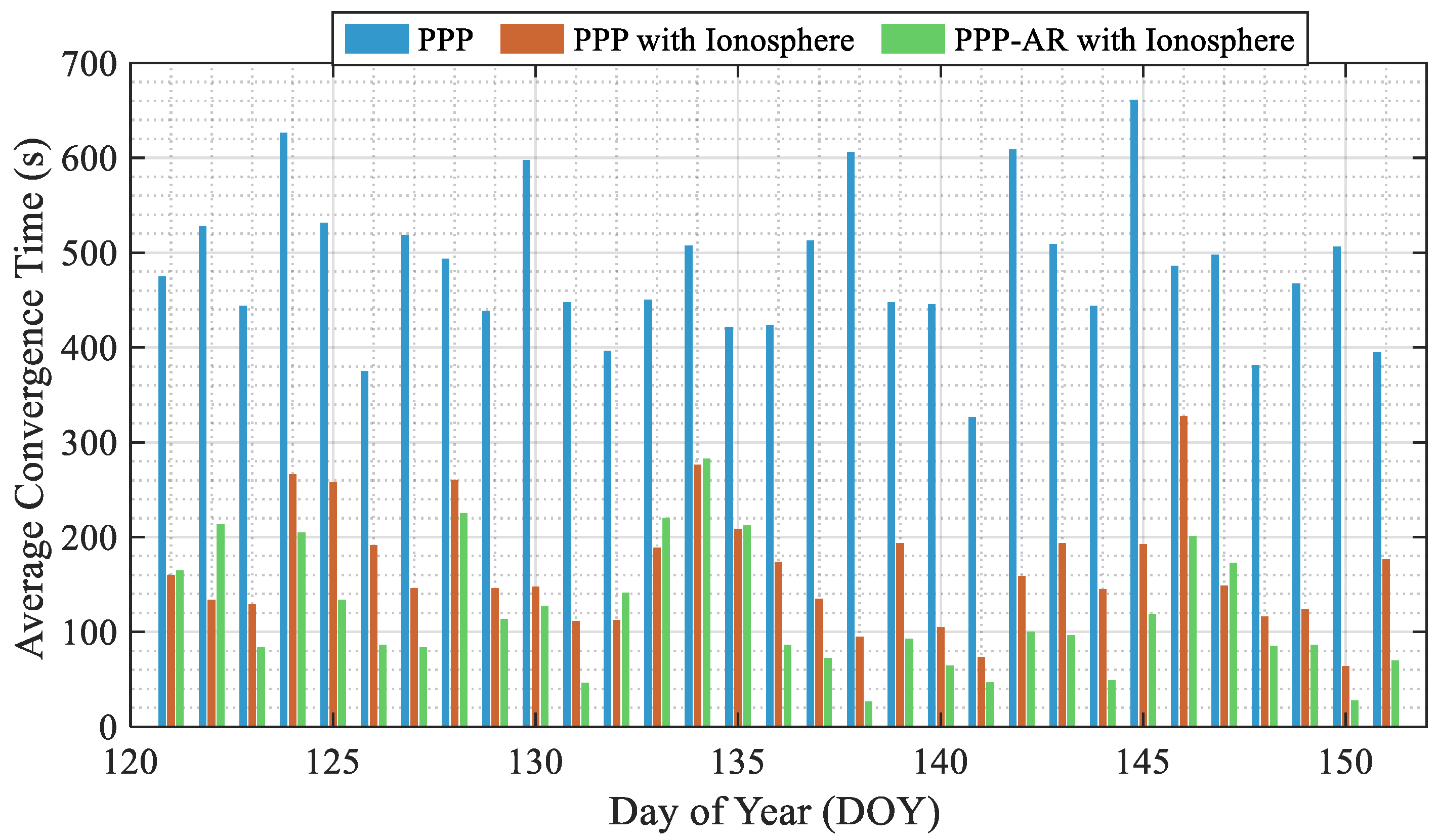

4.2. Kinematic Positioning Performance

4.3. Comparison with Previous Studies

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MADOCA-PPP | Multi-GNSS Orbit and Clock Augmentation-Precise Point Positioning |

| AR | Ambiguity resolution |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| SSR | State space representation |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| IF | Ionosphere-free |

| UC | Un-combined |

| TTFF | Time-to-first-fix |

| RTK | Real-time kinematic |

| ZTD | Zenith tropospheric delay |

| OSB | Observable-specific signal biase |

| TECU | Total electron content unit |

| LAMBDA | Least-squares ambiguity decorrelation adjustment |

| PAR | Partial ambiguity resolution |

| DOY | Day of year |

References

- Teunissen, P.J.G.; Khodabandeh, A. Review and principles of PPP-RTK methods. J. Geod. 2014, 89, 217–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Héroux, P.; Kouba, J. GPS Precise Point Positioning Using IGS Orbit Products. Phys. Chem. Earth 2001, 26, 573–578. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, S.; Su, K. PPP models and performances from single-to quad-frequency BDS observations. Satell. Navig. 2020, 1, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Bock, Y. Triple-frequency GPS precise point positioning with rapid ambiguity resolution. J. Geod. 2013, 87, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Zhang, X.; Ge, M.; Schuh, H. Three-frequency BDS precise point positioning ambiguity resolution based on raw observables. J. Geod. 2018, 92, 1357–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; Li, P.; Gao, Y.; Heck, B. A Unified Model for Multi-Frequency PPP Ambiguity Resolution and Test Results with Galileo and BeiDou Triple-Frequency Observations. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Jiang, X.; Zhang, X.; Ge, M.; Schuh, H. GPS + Galileo + BeiDou precise point positioning with triple-frequency ambiguity resolution. GPS Solut. 2020, 24, 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, X.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, X.; Wickert, J. Multi-GNSS phase delay estimation and PPP ambiguity resolution: GPS, BDS, GLONASS, Galileo. J. Geod. 2017, 92, 579–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.; Guo, J.; Meng, X.; Gao, K. Speeding up PPP ambiguity resolution using triple-frequency GPS/BeiDou/Galileo/QZSS data. J. Geod. 2020, 94, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, S.; Guo, J.; Zhao, Q. Multi-GNSS and Multi-Frequency Precise Point Positioning Based on High Accuracy Products from IGS Analysis Centers. Geomat. Inf. Sci. Wuhan Univ. 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Guo, F. Predicting atmospheric delays for rapid ambiguity resolution in precise point positioning. Adv. Space Res. 2014, 54, 840–850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Chen, W.; Ruan, R.; Liu, X. Evaluation of PPP-RTK based on BDS-3/BDS-2/GPS observations: A case study in Europe. GPS Solut. 2020, 24, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psychas, D.; Verhagen, S. Real-Time PPP-RTK Performance Analysis Using Ionospheric Corrections from Multi-Scale Network Configurations. Sensors 2020, 20, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yin, X.; Chai, H.; El-Mowafy, A.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Du, Z. Modeling and assessment of atmospheric delay for GPS/Galileo/BDS PPP-RTK in regional-scale. Measurement 2022, 194, 111043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, X.; Chai, H.; Xu, W.; Zhao, L.; Zhu, H. Realization and Evaluation of Real-Time Uncombined GPS/Galileo/BDS PPP-RTK in the Offshore Area of China’s Bohai Sea. Mar. Geod. 2022, 45, 577–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Wang, J.; Khodabandeh, A. Regional ionospheric correction generation for GNSS PPP-RTK: Theoretical analyses and a new interpolation method. GPS Solut. 2024, 28, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, P., Jr.; Morel, L.; Fund, F.; Legros, R.; Monico, J.; Durand, S.; Durand, F. Modeling tropospheric wet delays with dense and sparse network configurations for PPP-RTK. GPS Solut. 2017, 21, 237–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Huang, J.; Li, X.; Shen, Z.; Han, J.; Li, L.; Wang, B. Review of PPP–RTK: Achievements, challenges, and opportunities. Satell. Navig. 2022, 3, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Jiang, X.; Wang, J.; Li, P.; Ge, M.; Schuh, H. A new large-area hierarchical PPP-RTK service strategy. GPS Solut. 2023, 27, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabinet Office of Japan. Quasi-Zenith Satellite System Interface Specification: Multi-GNSS Advanced Orbit and Clock Augmentation—Precise Point Positioning; Cabinet Office of Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Ozeki, T.; Kubo, N. Evaluation of MADOCA-PPP in actual environment using MADOCA products decoded in real time processing. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Technical Meeting of The Institute of Navigation, Long Beach, CA, USA, 23–25 January 2024; pp. 830–839. [Google Scholar]

- Cabinet Office of Japan. Quasi-Zenith Satellite System Service Performance Report: MADOCA-PPP Technology Demonstration (Ionospheric Correction); Cabinet Office of Japan: Tokyo, Japan, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Teunissen, P.J.G.; Odijk, D. A Novel Un-differenced PPP-RTK Concept. J. Navig. 2011, 64, S180–S191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Yin, X.; Xiang, M. Improved PPP-RTK positioning performance by using the elevation-dependent weighting model for the atmospheric delay corrections. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2023, 34, 055003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Zhang, X. Assessment of the performance of GPS/Galileo PPP-RTK convergence using ionospheric corrections from networks with different scales. Earth Planets Space 2022, 74, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, J.; Zhang, B.; Liu, T.; Hou, P. Ionosphere-weighted undifferenced and uncombined PPP-RTK: Theoretical models and experimental results. GPS Solut. 2021, 25, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, H. Improving the (re-) convergence of multi-GNSS real-time precise point positioning through regional between-satellite single-differenced ionospheric augmentation. GPS Solut. 2022, 26, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Li, B.; Tu, R.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Z. Uncertainty estimation of atmospheric corrections in large-scale reference networks for PPP-RTK. Measurement 2022, 190, 110744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsen, M. Why Kp is such a good measure of magnetospheric convection. Space Weather 2004, 2, S11004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filjar, R.; Kos, S.; Krajnovic, S. Dst index as a potential indicator of approaching GNSS performance deterioration. J. Navig. 2013, 66, 149–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakota, M.; Jelaska, I.; Kos, S.; Brčić, D. Statistical Approach to Research on the Relationship Between Kp/Dst Geomagnetic Indices and Total GPS Position Error. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 2374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matzka, J.; Bronkalla, O.; Tornow, K.; Elger, K.; Stolle, C. Geomagnetic Kp index. GFZ Ger. Res. Cent. Geosci. 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teunissen, P.J.G. The least-squares ambiguity decorrelation adjustment: A method for fast GPS integer ambiguity estimation. J. Geod. 1995, 70, 65–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.W.; Yang, X.; Zhou, T. MLAMBDA: A modified LAMBDA method for integer least-squares estimation. J. Geod. 2005, 79, 552–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhagen, S.; Teunissen, P.J. New global navigation satellite system ambiguity resolution method compared to existing approaches. J. Guid. Control Dyn. 2006, 29, 981–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Feng, Y. Reliability of partial ambiguity fixing with multiple GNSS constellations. J. Geod. 2013, 87, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Kubo, N.; Chen, J.; Wang, J.; Wang, H. Initial positioning assessment of BDS new satellites and new signals. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, J.; Gong, X.; Chen, Q. The update of BDS-2 TGD and its impact on positioning. Adv. Space Res. 2020, 65, 2645–2661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | Strategy |

|---|---|

| Sample | 30 s |

| Elevation cutoff angle | 15° |

| Antenna phase center | igs20.atx |

| Station coordinates | Static mode, process noise of 0 m |

| Kinematic mode, process noise of 60 m | |

| Receiver clock offset | Estimated per epoch |

| Inter-System bias | Estimated per epoch |

| Tropospheric correction method | Estimate zenith tropospheric delay |

| Ionospheric correction method | Estimate slant ionospheric delay |

| Initial ratio test threshold | 1.5 |

| Station | PPP | PPP with Ionosphere | PPP-AR with Ionosphere |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALIC | 468 | 204 (56%) | 107 (77%) |

| CEDU | 484 | 296 (39%) | 181 (63%) |

| MOBS | 460 | 234 (49%) | 113 (75%) |

| NCLF | 461 | 301 (35%) | 220 (52%) |

| PTGG | 580 | 279 (52%) | 223 (62%) |

| WLAL | 571 | 361 (37%) | 175 (69%) |

| GMSD | 586 | 337 (42%) | 181 (69%) |

| MSSA | 523 | 302 (42%) | 168 (68%) |

| MIZU | 465 | 128 (72%) | 65 (86%) |

| Station | PPP | PPP with Ionosphere | PPP-AR with Ionosphere |

|---|---|---|---|

| ALIC | 570 | 206 (64%) | 112 (80%) |

| CEDU | 628 | 319 (49%) | 188 (70%) |

| MOBS | 587 | 254 (57%) | 131 (78%) |

| NCLF | 544 | 335 (38%) | 234 (57%) |

| PTGG | 644 | 272 (58%) | 236 (63%) |

| WLAL | 665 | 394 (41%) | 186 (72%) |

| GMSD | 736 | 369 (50%) | 244 (67%) |

| MSSA | 698 | 349 (50%) | 188 (73%) |

| MIZU | 593 | 125 (79%) | 69 (88%) |

| Station | Report | This Work |

|---|---|---|

| ALIC | 180 | 180 |

| CEDU | 90 | 300 |

| MOBS | 90 | 210 |

| PTGG | 330 | 420 |

| WLAL | 270 | 330 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Bian, Q.; Yin, X. Enhancing Precise Point Positioning Under Active Ionosphere Using Wide-Range Ionospheric Corrections Derived from MADOCA Service. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010184

Bian Q, Yin X. Enhancing Precise Point Positioning Under Active Ionosphere Using Wide-Range Ionospheric Corrections Derived from MADOCA Service. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):184. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010184

Chicago/Turabian StyleBian, Qianqian, and Xiao Yin. 2026. "Enhancing Precise Point Positioning Under Active Ionosphere Using Wide-Range Ionospheric Corrections Derived from MADOCA Service" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010184

APA StyleBian, Q., & Yin, X. (2026). Enhancing Precise Point Positioning Under Active Ionosphere Using Wide-Range Ionospheric Corrections Derived from MADOCA Service. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010184