1. Introduction

The ever-increasing desire to surpass the known limits of outer space has driven the development of new technologies and materials that facilitate success in this direction. The severe environmental conditions during reentry, which include ultra-high temperatures (exceeding 1600 °C) with intense heat transfer, high velocities and pressures, and a chemically active atmosphere, especially in the upper atmosphere, present an urgent need for new materials that can be used in a high-performance thermal protection system for modern space vehicles, like satellites, reentry vehicles, or rockets [

1,

2,

3]. Thermal Protection System (TPS) materials play a very important role in the aerospace industry, being used to manufacture the heat shield that protects the structure, aerodynamic surfaces, and payload of spacecraft from the severe heating encountered during launch, hypersonic flight, and atmospheric reentry. It acts as a heat shield that prevents hot air from entering the vehicle and potential impacts with space debris [

2,

4,

5,

6]. The increasing number of missions today has heightened the requirements for low-cost reusable launch vehicles (RLVs) for the exploration of new planets in both manned and unmanned missions [

7]. To ensure the survival of the vehicle and the protection of the payload, an efficient, reliable, and thoroughly characterized system (TPS) is required.

The last three decades have witnessed the rapid growth of TPSs and lightweight ablative materials with high anti-ablation and insulation performances, used in missions such as the Mars Sample Return and Stardust [

4].

Although carbon/carbon composites are among the most popular materials used as TPSs due to their excellent mechanical properties, they are susceptible to oxidation at high temperatures [

1,

8] and have very high production costs. A material with low density, low thermal conductivity, and low resistance to flame ablation that also exhibits excellent thermal stability at high temperatures is a nanocomposite composed of silico-phenolic resin (CF/Si/PR), reinforced with carbon fiber made by sol–gel polymerization of a mixture of chopped carbon fibers with Si/PR aerogel by solvent exchange and automatic carbon deposition (APD), which was made by Chonghai Wang et al. [

9]. To reduce the costs of both the production processes and raw material used to obtain C-C composites, ablative materials have been developed, which are single-use consumables that have a much lower cost, are versatile, withstand various hyperthermal environments, and are easier to manufacture and handle [

8]. Ablative composites are sacrificial thermal protection materials with a high degree of endothermy, used to manage the thermal shielding of propulsion devices (such as liquid and solid rocket motors (SRM)) [

2] or to protect vehicles and probes during hypersonic atmospheric entry [

5,

7]. The concept behind the consumable materials (so-called ablatives) is that they burn slowly, in a controlled manner, so that the heat is directed away from the spacecraft wall by the gases generated during the ablation process, and the remaining solid material serves to insulate the vehicle from the superheated gases [

6,

10,

11]. One of the most widely used ablative materials by NASA is PICA (phenolic impregnated carbon ablator), a material patented by NASA in the 1990s, which consists of a carbon preform impregnated with phenolic resin [

12]. PICA was used as a heat shield for the Stardust capsule [

13], but also for entry into the Martian atmosphere during the Mars Science Laboratory mission [

14].

Among the most recognized polymer matrices for the development of ablative materials (since their discovery [

15] to present [

16,

17]) are phenolic resins. Ash-forming ablative consumables are used in combination with sublimating or melting reinforcements (e.g., silica, nylon) [

18]. Other commonly used reinforcement elements are natural mixtures (cork [

19,

20,

21]) or inorganic preforms (carbon felt [

22,

23] or graphite felt [

10,

24]). They are often and intensively studied through new compositions and modifications by inserting various ceramic additives or nanoparticles (boron, silicon, etc.) to enhance their mechanical, thermal, or thermo-mechanical properties.

New heat-resistant polymer matrices based on polysiloxane [

25] and phthalonitrile resins have shown improvements over traditional phenolic resins. One such resin (polysiloxane) successfully used in thermal protection applications [

26,

27,

28,

29] is UHTR 6398-S, a solvent-free resin manufactured by Techneglas, Perrysburg, OH, USA. Recent studies in which ablative composite materials based on polysiloxane resin (UHTR) reinforced with carbon fiber (CF), which were processed and manufactured in a laboratory environment, were compared through ablation tests with common ablative composites based on phenolic resin reinforced with carbon fiber, indicated encouraging results for the use of these resins in applications aimed at thermal protection [

27,

28]. In a NASA technical report in 2024, P. B Patel and his team used UHTR due to its excellent ablation characteristics (low thermal conductivity, lightweight composition, high thermal resistance, and the ability to form a durable carbon layer), which was reinforced with carbon fibers, but also in combination with carbon nanotubes forming laminar composites called bulk nanocomposite lamination (BNL) [

30]. Needle-punched silica fabric was infiltrated with polysiloxane resin and characterized for applications targeting thermal protection systems in the study described by R. M McDermott et al. [

31] as a less expensive alternative to the 3D thermal protection system used on the Orion space shuttle.

Due to the encouraging information found in the literature, the current study focused on the development of a new form of ablative thermal protection material by using a relatively new polymer matrix based on polyxylane resin (UHTR 6398-S) with high-performance thermal properties and a graphite felt reinforcement element. This new ablative material was thermally tested, characterized, and compared with a recognized ablative material based on phenolic resin (Isophen 215 SM 57%), which uses the same reinforcement element, graphite felt.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Graphite felt preform purchased from SGL Group—The Carbon Company (Wiesbaden, Germany) was used as a reinforcement material. The graphite felt was a 0.5 cm thick preform, heat-treated at 2200 °C, and contained less than 300 ppm impurities [

32]. Soft graphite felt is characterized by high flexibility and ease of processing. It is distinguished by low thermal conductivity and resistance to high temperatures, does not take up static electrical charges, and has a low thermal capacity, excellent homogeneity, and high purity grade.

Two distinct polymer matrices were used. The first polymer matrix was a resol-type phenolic resin ISOPHEN 215 SM 57% supplied by ISVOLTA S.A., Bucharest, Romania, with a density value of 1.135 g/cm

3. The second polymer matrix used was UHTR 6398-S resin (with a density value of 1.2 g/cm

3), which consists of a variety of polysiloxane chemistries, purchased from Techneglas, LLC (Perrysburg, DH, USA) [

33]. This resin system offers the uniqueness of low-temperature curing, which promotes extreme resistance to a high-temperature environment. It also possesses properties such as low heat transfer, excellent chemical resistance, and low emission of toxic fumes when exposed to flame sources. The UHTR system in this study was found to have a carbonization efficiency of 87%.

2.2. Obtaining Procedure and Measurements

The ablative composites were obtained by impregnating graphite felt with the polymer matrix. Two distinct types of ablative materials were obtained: GF/UHT- for ablatives using UHTR 6398-S resin and GF/Isophen 215 for ablatives using ISOFEN 215 SM 57% resin.

The polysiloxane resin UHTR-6398S has a high viscosity at room temperature (>10,000 cP), which makes proper impregnation impossible without a prior thermal fluidization step. Thus, the resin was heated at 110 °C for 15 min, reaching its viscosity of approximately 900–1000 cP, considered optimal for fiber impregnation.

The graphite felt was sized (

Figure 1a) and then dried for 2 h at 100 °C to eliminate the residual moisture and gases retained in the internal porosity of the fibrous material. The dried preforms were then fully immersed in the resin and maintained for 60 min, with gentle stirring to facilitate air removal from the pores and ensure an efficient transfer of resin inside the fibrous structure. The saturated preforms were placed into a metal mold (

Figure 1b) and cured in a hot press system (

Figure 1c) where a force of 5 kg/cm

2 was applied at a constant temperature of 225 °C for 3 h to fully complete the crosslinking process of the resin under controlled pressure conditions. A total of six samples were obtained for each type of ablative composite (GF/UHT and GF/Isophen 215).

In order to characterize and analyze the specific properties of the ablative materials, these new materials were subsequently subjected to a series of investigations, tests, and measurements. Morphological analysis was performed by optical microscopy and scanning electron microscopy observations. Optical microscopy was performed using a Meiji ML 8520 microscope, equipped with an image capture and processing kit (Infinite Analyze-Lumenera Corporation (Ottawa, ON, Canada) video camera and dedicated Infinity Analyze software 6.5) and SEM analysis with a QUANTA FEI 250 (Eindhoven, The Netherlands), with a field emission gun with a resolution of 1.0 nm, and an energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) with a resolution of 133 eV. FTIR spectroscopy was performed using a spectrometer (Nicolet iS50 from Thermo Scientific Company, Madison, WI, USA) equipped with an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) instrument. All spectra were collected in the range 4000–500 cm−1, with a resolution of 4 cm−1, performing a number of 32 scans/sample. Background spectra were recorded before each sample measurement and automatically subtracted. This technique was used to evaluate the changes that occurred before and after crosslinking of resins (phenolic and polysiloxane) as well as to highlight the interactions that occurred at the resin–graphite felt interface. Thermal behavior was monitored by differential scanning calorimetry, using DSC 300 Caliris®Classic equipment from Netzsch (NETZSCH-Gerätebau GmbH, Selb, Germany). The sample (~10 mg) was inserted in an open crucible made of alumina and heated with 10 K·min−1 between 30 and 600 °C in an argon atmosphere.

Thermal shock tests in a static furnace (Nabertherm calcination furnace) consisted of introducing the sample from room temperature directly to 1100 °C (in an oxidizing atmosphere). This test highlighted the evaluation of mass loss after each holding period at the critical temperature and the evolution of material integrity after testing. Oxy-acetylene Flame Testing was carried out using an oxy-acetylene flame testing facility designed and built by INCAS. The temperatures of the flame jet on the surface of the ablative materials and the ablative heat transfer temperature measured on the surface opposite to that acted on by the flame were recorded using a laser pyrometer and a thermal imaging camera, respectively. Complementary mechanical tests were performed using the INSTRON 5982 facility (manufactured by INSTRON, Norwood, MA, USA) equipped with a 100 kN force cell and consisted of compressive stressing of the ablative materials under ambient conditions (25 °C) and at a temperature of 250 °C.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Optical Microscopy Analyses

Optical microscopy aims to identify the presence of voids and defects over an extended area of the cross-section. Samples with non-uniform surfaces present areas located in different planes, which leads to preferential focusing depending on the plane viewed and to images in which areas of different clarity are observed.

Figure 2 shows the optical microscopy images for both sets of ablative materials (GF/Isophen and GF/UHT, respectively).

The uneven appearance of the surface of the outer layer, with areas where the graphite felt preform can be observed, is due to the contact with the mold during the pressing stage, but it is important to mention that these areas do not represent voids in the structure but only discontinuities of the outer layer. At a higher magnification, it can be seen that in the discontinuity area of the outer layer, the internal structure of the composite can be seen, with the graphite felt preform deeply impregnated with resin. To analyze the degree of wetting of the graphite preform in depth, SEM analyses were performed on the cross-section of each sample.

3.2. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

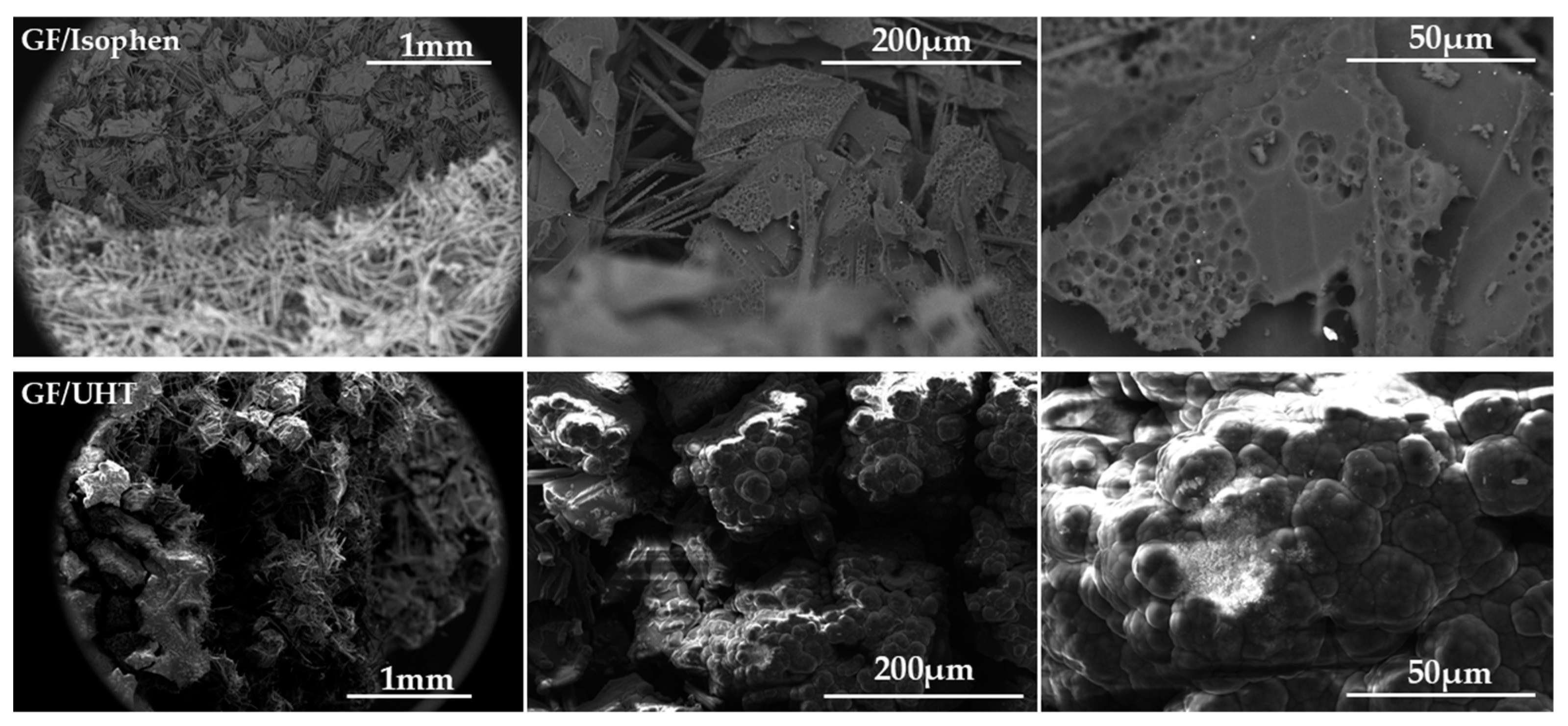

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the cross-section of ablative material samples were obtained to highlight the degree of impregnation and wetting of the graphite felt preform filaments.

Figure 3 illustrates the cross-sectional SEM images of the studied ablative material samples (GF/Isophen and GF/UHT, respectively) at different magnifications (100×, 800×, and 3000×). At 100× magnification, voids appear to be observed in the material section, but at higher magnifications, it is observed that in these voids, the graphite preform filaments are completely wetted in the resin, both in the GF/Isophen and GF/UHT samples. This confirms that the impregnation of the graphite preform was achieved in depth, even in areas where small voids are found in the ablative material.

3.3. FTIR

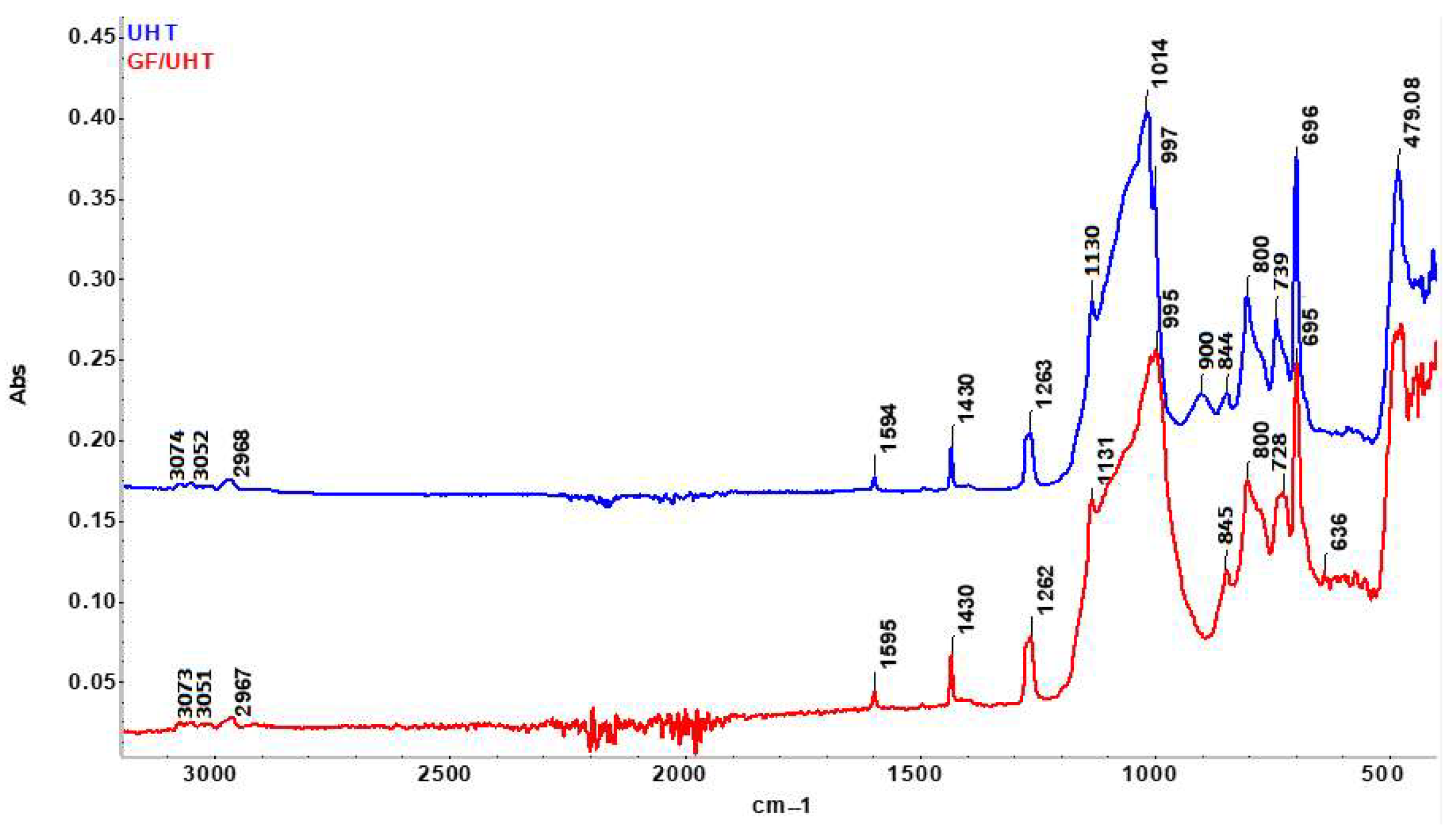

FTIR analysis was performed on both the ablative samples (GF/Isophen and Gf/UHT) and the resins that constitute these materials (UHTR and Isophen 215 resin, respectively).

The FTIR spectrum obtained on Isophen 215 SM 57% non-crosslinked liquid resin (Magenta curve) shows all the characteristic bands associated with a resole-type phenol-formaldehyde resin (

Figure 4). The broad band at 3267 cm

−1 appears due to the stretching vibration of the O-H bond related to the phenolic and methylol groups (-CH

2OH), which indicates the existence of significant inter- and intramolecular hydrogen bonds, which can be frequently observed in phenolic resin. The bands at 2943 and 2833 cm

−1 originate from the aliphatic -CH

2 and methylol stretching vibrations, confirming the presence of aliphatic side chains characteristic of un-crosslinked phenolic resins. The bands observed at 1595 and 1512 cm

−1 are due to the stretching vibrations of aromatic C=C bonds. The presence of the bands at 1474 and 1456 cm

−1 appears due to the deformation of the C-H/-CH

2- bonds originating from the methylene and methylol groups, reflecting the existence of lateral -CH

2 units linking the aromatic rings, without the formation of a stable three-dimensional network yet. The peak at 1370 cm

−1 appears due to the in-plane deformation of the phenolic OH bonds, while the peaks at 1237, 1153, 1111, and 1017 cm

−1 can be attributed to C-O vibrations originating from the phenolic and methylol groups and possibly incipient C-O-C ether bonds, which may indicate the beginning of condensation. The bands observed in the low frequency regions (887–692 cm

−1) highlight the out-of-plane vibrations of the C-H bond originating from the benzene nucleus [

34,

35,

36].

In the case of the sample GF/Isophen, which contains graphite felt impregnated with cross-linked phenolic resin, the FTIR spectrum highlights the drastic reduction in the intensity of the bands specific to non-crosslinked phenolic resins, due to the consumption of these reactive groups during cross-linking, and especially to the very weak spectral influence of the graphite felt. Thus, one can observe the almost total disappearance of methylol groups (1017–1153 cm

−1) during the polycondensation reactions, indicating the formation of methylene and ether bridges, which confirms the formation of a stable three-dimensional network. Additionally, the broad OH band at 3267 cm

−1 decreases substantially, confirming the consumption of free phenolic groups as cross-linking occurs, in accordance with observations reported by other authors in the case of fully cross-linked resins [

37]. The appearance of the spectrum is also influenced by the presence of graphite, which generates an almost flat IR signal/background (since carbonaceous materials exhibit weak and non-specific adsorptions), partially masking the aromatic structures of the resin, which remain visible only as small fluctuations in the signal [

38]. Therefore, the resulting spectrum confirms both the advanced crosslinking of the resin and the structural influence of the graphite felt in the final composite.

The FTIR spectrum obtained on the non-crosslinked UHT sample shows the characteristic bands originating from the methylated siloxane units (

Figure 5). The bands at 2968 cm

−1 and 1263 cm

−1 appear due to the vibrations of the C-H bonds in the Si-CH

3 groups and are in accordance with the values reported in the literature for siloxane resins. The Si-O-Si region presents 3 distinct regions at 1130, 1014, and 997 cm

−1, which can be attributed to a partially condensed polymer network, a phenomenon frequently observed in the case of polysiloxanes obtained by the sol–gel method. The appearance of the band at 900 cm

−1 confirms the appearance of the terminal band related to the Si-OH (silanol) terminal groups, a band that disappears after crosslinking. The weak band at 1594 cm

−1 is not specific to the siloxane skeleton but may appear due to minor vibrational contributions originating from residual organic species.

In the case of the GF/UHT composite, the FTIR spectrum reveals a clear remodeling of the siloxane network. The Si-O-Si region reorganizes and presents two main maxima (1131 and 995 cm

−1), indicating a high degree of polycondensation, in accordance with the phenomena observed in the case of crosslinked siloxane films. The complete disappearance of/decrease in the band at 900 cm

−1 confirms the complete consumption of the reactive Si-OH groups as a result of the complete crosslinking/densification of the siloxane networks. The band at 739 cm

−1 that can be observed in the UHT resin shifts to the value of 725 cm

−1 in the GF/UHT composite, suggesting a modification of the vibrational environment of the Si-O-Si chains as a result of the interaction with the carbon phase originating from the graphite felt. This aspect is compatible with the reorganization of the network and especially with the presence of interactions occurring at the resin–carbon interface, phenomena similar to those observed in polysiloxane hybrid materials [

25,

39,

40,

41].

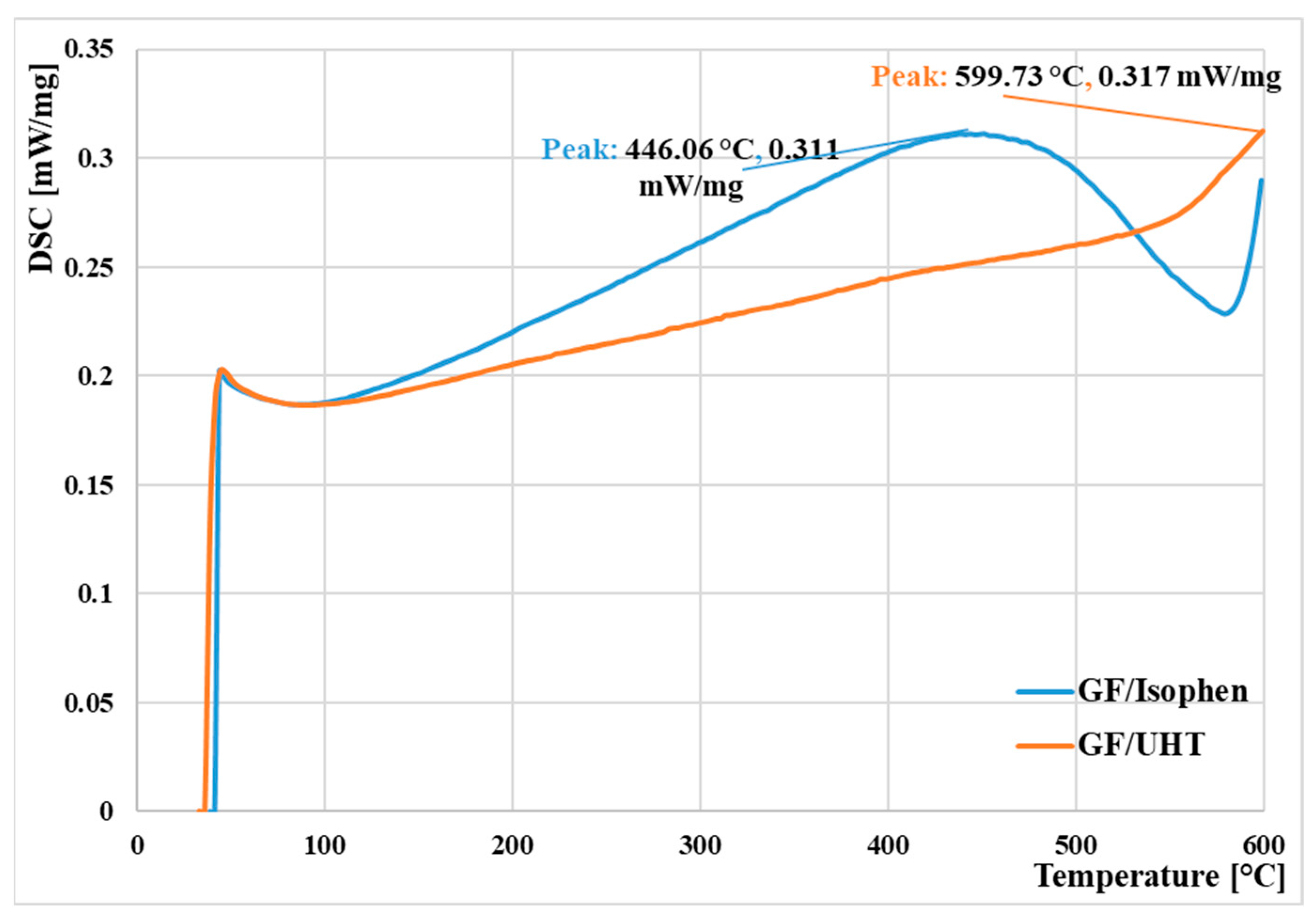

3.4. Differential Scanning Calorimetry

Thermal tests by Differential Scanning Calorimetry were conducted between 30 °C and 600 °C in an inert atmosphere.

Figure 6 illustrates the DSC curves of the ablative materials overlapped on the same graph.

It can be observed that the DSC curves behave slightly similarly to the two types of thermosetting resins that were the basis for obtaining the ablative materials. The major endothermic peak corresponding to the glass transition (Tg) is observed at 446.06 °C for the phenolic resin-based ablatives (

Table 1). For the sample made of UHT resin-based ablative material, it can be observed that the DSC curve shows a linear increase in values, and the major endothermic peak is found towards the maximum temperature of the thermal calorimetry test (599.73 °C). This value is most likely higher, since the limitations of DSC equipment cannot exceed temperatures of 600 °C. Slight differences can be observed in the corresponding glass transition values, with the onset and end temperatures being higher in the case of the UHT resin, indicating a greater amount of heat released during the reaction, most likely due to its chemical composition.

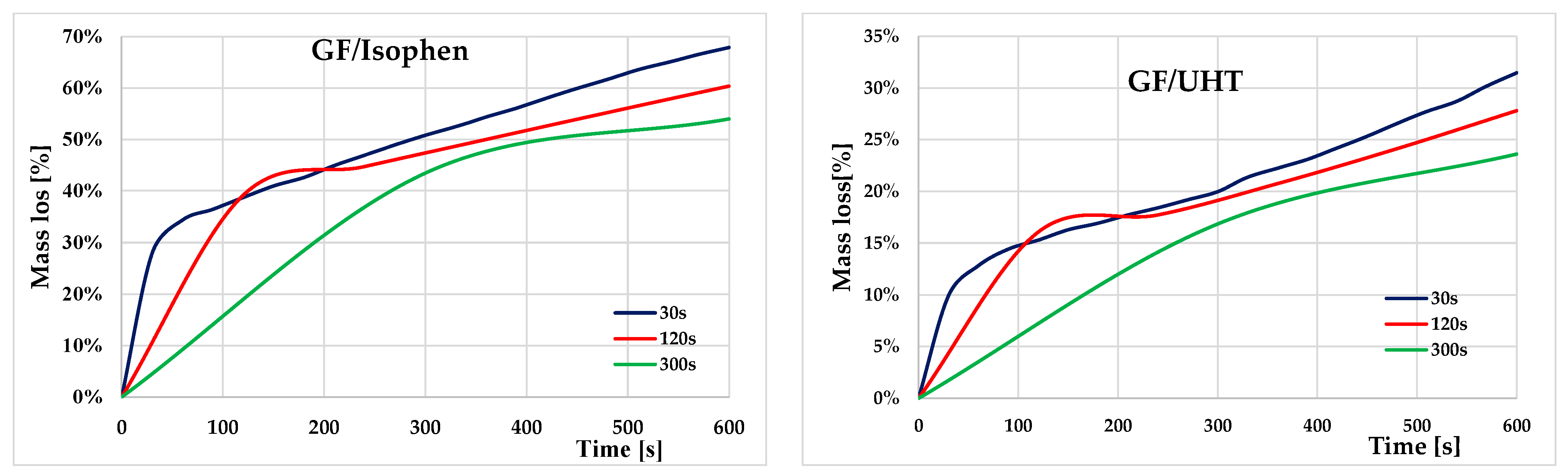

3.5. Thermal Shock Tests in Static Furnace

For both types of ablative materials, three testing regimes were conducted to evaluate mass loss as a function of exposure cycles. All specimens were exposed to a total time of 600 s (10 min), but three different cycling conditions:

Test 1—(blue line): 20 cycles of 30 s each;

Test 2—(red line): 5 cycles of 120 s each;

Test 3—(green line): 2 cycles of 300 s each.

After each thermal shock cycle, the specimens were cooled to room temperature and weighed to determine the cumulative mass loss. The results of the mass measurements are summarized in

Table 2 and represented in

Figure 7.

Figure 7 shows the evolution of relative mass loss (expressed as a percentage of the initial mass) for three ablative specimens subjected to heat treatment at a constant temperature of 1100 °C.

The slight differences observed in the initial masses of the GF/Isophen and GF/UHT specimens are attributed to both the intrinsic density of the polymer matrices and the presence of volatile components in the phenolic system. The phenolic resin has a density of 1.135 g·cm

−3, whereas the polysiloxane resin exhibits a higher density of 1.20 g·cm

−3, leading to a higher mass uptake for the UHT-based composites at similar impregnation volumes. In addition, the phenolic resin contains methanol as a solvent, which starts to evaporate at approximately 70 °C, generating gas bubbles within the composite mass. Several preliminary trial sessions demonstrated that extended dwell time at 70 °C promotes solvent evaporation and gas release from the resin solution.

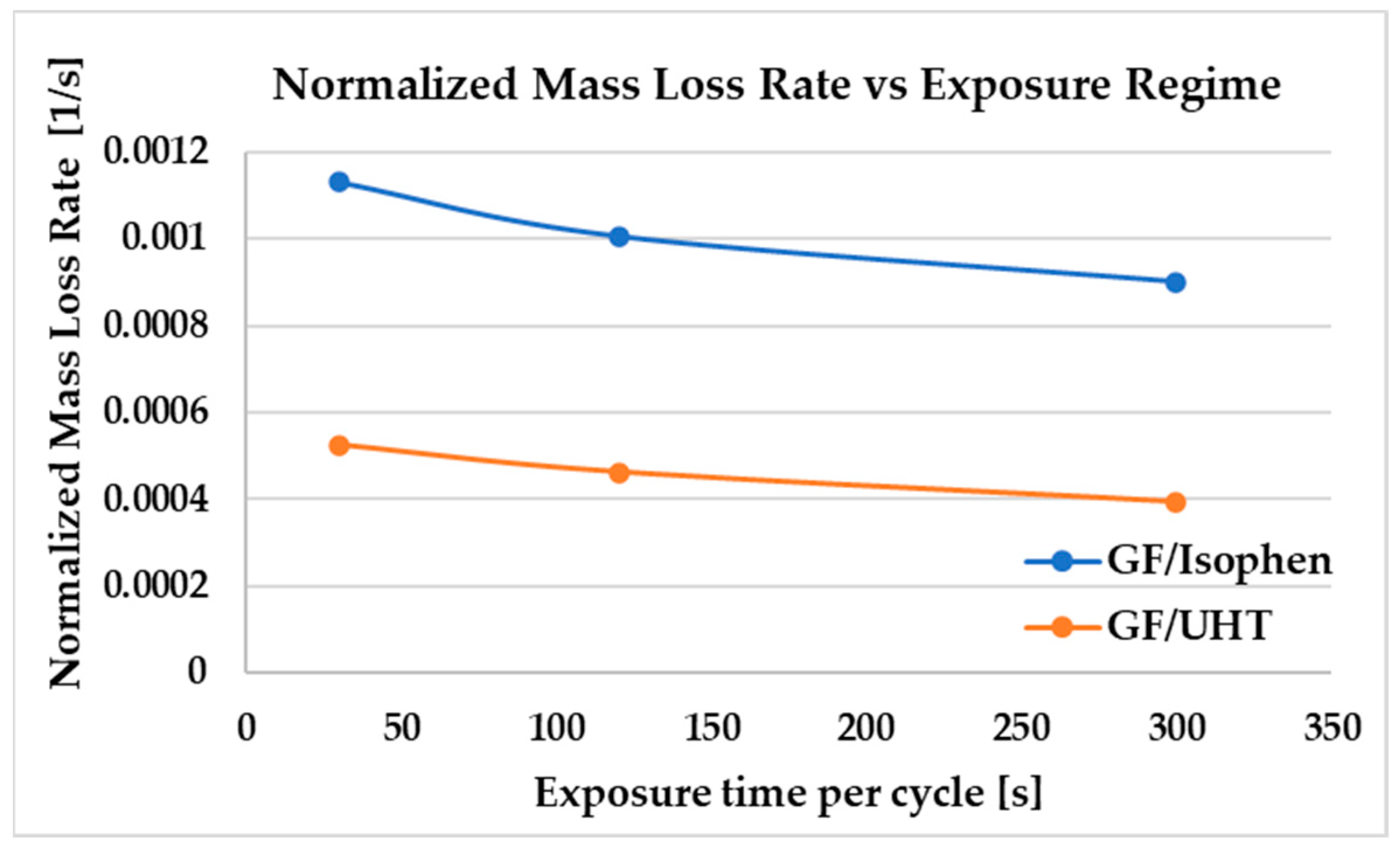

where

—total mass loss [g],

—initial mass [g] and t—total exposure time [s].

To eliminate the influence of different initial specimen masses, the mass loss results were additionally normalized (

Figure 8) with respect to both initial mass and total exposure time, using Equation (1). The normalized results confirm that GF/UHTR exhibits consistently lower degradation rates compared to GF/Isophen across all thermal cycling regimes.

Figure 9 illustrates the samples from the two sets of ablative material, before and after exposure at high temperature (1100 °C) for 10 min each, with maintenance in the three different dwell periods: 30 s, 120 s, and 300 s. Thermal degradation is well highlighted on the upper surface of the samples directly exposed to the high temperature in the furnace. Macroscopically, thermal degradation is observed from the outside of the ablative composites towards the inside of the samples for both the GF/Isophen and GF/UHT samples. This aspect is specific to ablative materials, which tend to be consumed in a controlled manner, from the outside to the inside, due to the gases released during the combustion process.

In

Figure 10, the comparison between the two classes of ablative materials is graphically represented. A general trend is observed for both sets of ablative materials as the mass loss decreases with the decrease in the number of temperature test cycles.

Thus, after 10 min of exposure to a temperature of 1100 °C, it is observed that in the case of GF/UHT samples, the mass loss for all three sets of thermal cycling is significantly lower than in the case of ablative GF/Isphen samples. At a dwell period of 30 s per stage, the GF/Isophen sample has a loss of 68% while the GF/UHT sample has a loss of only 31%. At a dwell period of 120 s per stage, the GF/Isophen sample has a loss of 60% while the GF/UHT sample has a loss of only 28%, and at a dwell period of 300 s per stage, the GF/Isophen sample has a loss of 54% while the GF/UHT sample has a loss of only 24%.

3.6. Oxy-Acetylene Flame Testing

Testing ablative materials in an oxy-acetylene flame represents a feasible experimental alternative, capable of reproducing an important part of the thermal stresses to which materials are subjected during reentry. It is valuable to mention the importance of performing this type of preliminary testing by subjecting materials with ablative application potential to oxy-acetylene flame, prior to the final definitive test for re-entry applications. The plasma-jet wind tunnel testing is extremely expensive and requires complex and long-term preparation, which consequently limits the number of samples and tests performed, providing essential data but often being limited in the number of cycles and materials evaluated. The oxy-acetylene test performed within this study simulates some of the parameters during the re-entry phase, allowing a significantly hot, concentrated flame that can reach around 3100 °C.

The oxy-acetylene flame was maintained at a constant distance of 4 cm from the specimen (

Figure 11) by using a Brenner device, generating an initial temperature of over 1600 °C at the specimen surface.

Figure 12 shows the temperature evolution graph measured during oxyacetylene flame testing. The red line represents the temperature of the flame jet on the surface of the ablative sample during the thermal test, while the green line (GF/UHT) and the blue line (GF/Isophen) represent the temperature on the opposite surface of the ablative sample when subjected to the flame jet to evaluate the heat transfer temperature through the material.

After approximately 70 s, the GF/Isophen ablative material is completely penetrated by the oxyacetylene flame flow, while the GF/UHT ablative material is not penetrated, not even after 90 s, with the flame being dispersed over the entire surface of the material.

In the temperature graph, it can be seen that the GF/UHT ablative material exhibits superior thermal performance, providing lower heat transfer temperature values through the material, together with greater resistance to flame penetration compared to GF/Isophen. These observations will be further correlated with the morphostructural analyses.

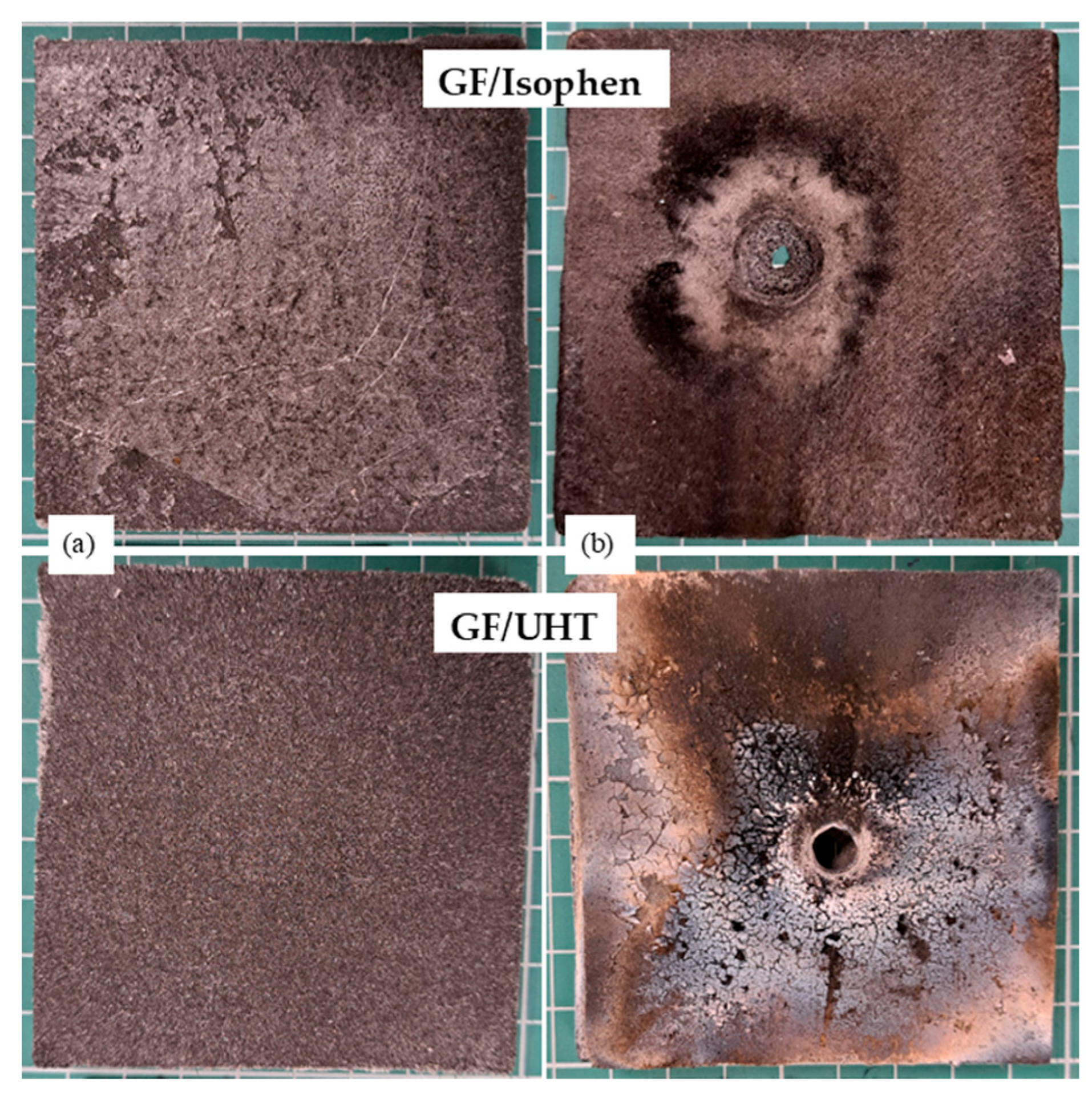

Figure 13 illustrates the ablative samples prepared for thermal testing in an oxyacetylene flame jet, comparing their appearances before and after exposure.

The GF/Isophen samples were completely penetrated by the flame at the end of the test, while the GF/UHT material was not completely penetrated, with the flame spreading over the entire surface of the ablative plate. This could be due to the composition of the two resins, which probably generate different ablation mechanisms in terms of gas emission.

Although numerous ablative materials have been studied over the past decades, only a very small fraction of published work reports oxy-acetylene flame testing under thermal environments comparable to those used in this study (≈1600–2000 °C for 70–300 s). Most aerospace ablators are evaluated using arc-jet, plasma torch, radiant heating, or laser-based facilities, which generate different heat fluxes and reactant species. Consequently, directly comparable datasets in the open literature are limited.

Table 3 summarizes the most relevant ablative systems tested under oxy-acetylene torch conditions alongside the results obtained in this work. Despite the restricted number of comparable sources, these studies are widely accepted benchmarks for evaluating ablative resistance under high-enthalpy flame environments.

3.7. SEM Analysis

SEM (

Figure 14) was performed on the surface of the ablative material samples on which the oxy-acetylene flame jet acted.

For the sample of GF/Isophen ablative material, the SEM images were taken from the area surrounding the perimeter where the oxy-acetylene flame acted and penetrated. These images indicate advanced thermal degradation; both the polymer matrix and the reinforcing element, the graphite felt, were thermally affected and show spongy/carbonized and decomposed areas.

In the case of the GF/UHT ablative material sample, SEM images captured in the area of action of the flame flow illustrate areas of agglutination, where the resin overlaps the graphite felt fibers and behaves as a thermo-protective coating.

Structural cracks at the material surface are present for both ablative materials, indicating the release of decomposition gases, which propagate and help cool the substrate.

3.8. Mechanical Tests

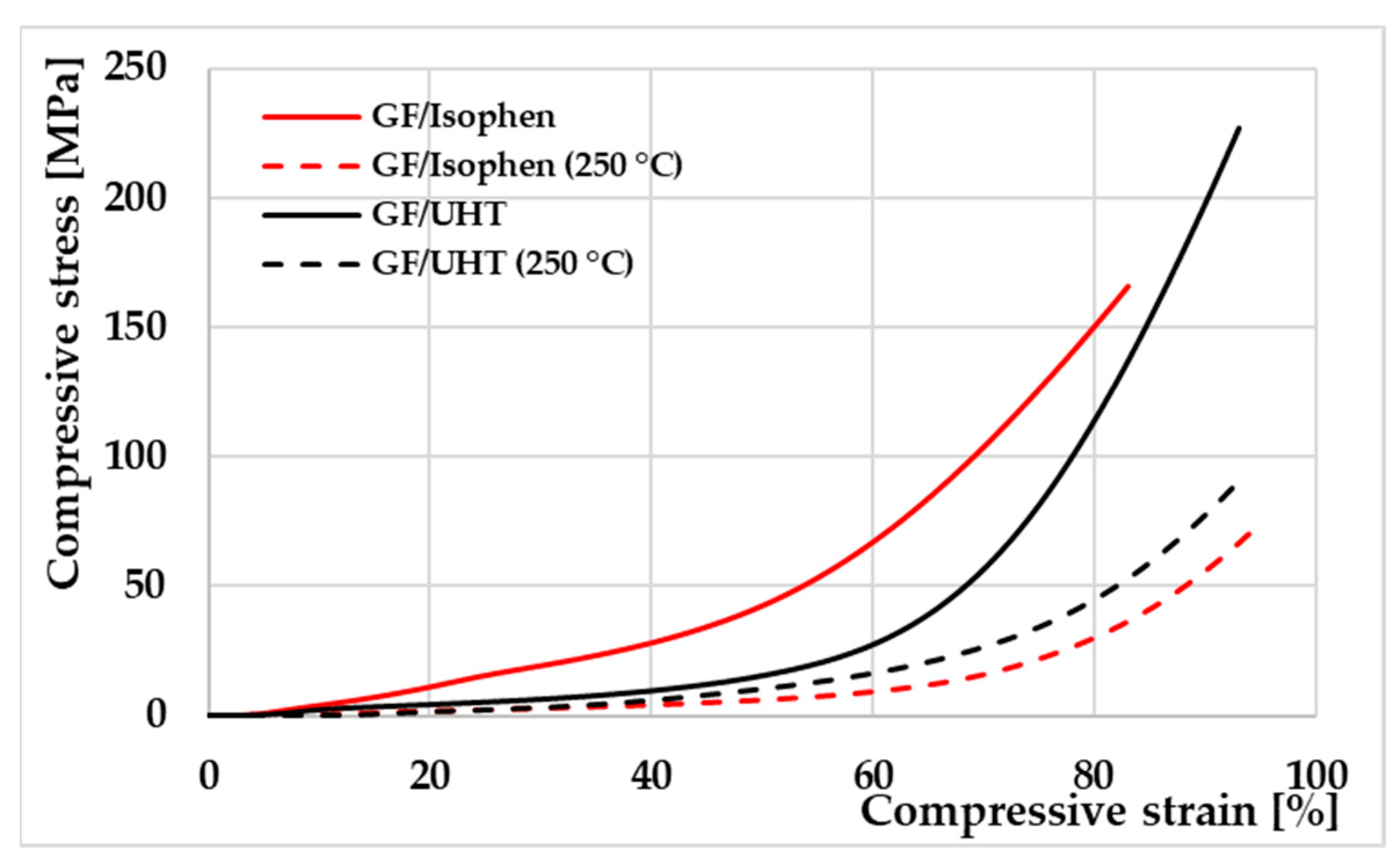

Three rectangular specimens of each ablative material were tested by compression, both at room temperature and at a temperature of 250 °C, using a testing speed of 1.3 mm/min.

Table 4 and

Figure 15 present the averaged values.

The averaged values (shown in

Table 4) of the compression test for the GF/UHT samples are slightly improved compared to those of the GF/Isophen samples, both in the ambient condition and at high temperature. Increments in the modulus of elasticity values are observed by up to 75% at room temperature and 9% at high temperatures. The compressive strength shows the same increasing trend, with a 35% increase at room temperature and 19% at high temperatures.

Figure 15 illustrates the stress–strain curves for the compression test of the studied ablative materials. It can be seen that compressive deformation tends to maintain the same trend for both types of ablative materials (over 90% compressive strain), in both thermal test environments (room temperature and +250 °C).

4. Conclusions

Two distinct classes of ablative material (GF/Isophen and GF/UHT, respectively) were developed, based on the same reinforcing material consisting of graphite felt, but with different polymer matrices, consisting of phenolic resin Isophen 215 SM 57% and polysiloxane resin (variety) UHTR 6398-S, respectively.

These ablative materials were characterized and analyzed using experimental laboratory methods to evaluate their behavior under thermal exposure (controlled thermal exposures in an oven and direct testing in an oxyacetylene flame), through DSC tests in the temperature range of 30–600 °C, as well as through mechanical compression tests (ambient temperature and +250 °C, respectively). Morphostructural investigations (optical microscopy and scanning electron microscopy) completed the study. Microstructural investigations revealed a uniform impregnation of both resins into the graphite felt preform, with no uncovered areas. Surface and cross-sectional images of the samples illustrated the graphite preform filaments fully covered (wetted) for both sets of ablative materials. The irregular distribution of the outer layer observed on the surface of the samples is associated with the pressing process but does not indicate structural voids. At 100× magnification in the optical images, the presence of the resin throughout the spaces between the graphite fibers was confirmed, a conclusion also validated by the SEM images performed at higher magnifications, thus validating the efficiency of the applied technological process.

Thermal analyses showed positive behavior for the ablative composite samples containing the UHT resin. During the differential scanning calorimetry test, the major endothermic peak corresponding to the glass transition (Tg) for the phenolic resin-based ablatives was reached at a value of 446.06 °C. For the sample with UHT resin-based ablative material, the DSC curve showed a linear increase in values, with the major endothermic peak appearing at the maximum temperature of the thermal calorimetry test (599.73 °C). Controlled thermal tests in the furnace showed good dimensional stability and gradual oxidation of the exposed surface without premature disintegration. Cyclic tests (30, 120, 300 s) revealed an increase in degradation level proportional to the duration of a cycle, indicating limited thermal resistance under continuous/extended exposure, but good stability for short regimes. The GF/UHT ablative samples showed reduced mass loss compared to the GF/Isophen ablative samples (only 31% compared to 68%, for those that were maintained for 30 s on the plateau, 28% compared to 60%, for those maintained for 102 s on the plateau, and for those maintained for 300 s, the mass loss was only 24% for GF/UHT, while for GF/Isophen it was 54%). Oxyacetylene flame jet testing showed that the GF/UHT ablative material exhibited superior thermal performance compared to GF/Isophen, offering lower heat transfer temperature values through the material, along with higher resistance to flame penetration compared to GF/Isophen (Gf/Isophen was fully penetrated after approximately 70 s, while GF/UHT was not penetrated by the oxyacetylene flame).

SEM images of the ablative samples after exposure to oxy-acetylene flame flux revealed severe carbonization and thermal degradation of both the polymer matrix and reinforcement in the GF/Isophen, while the GF/UHT samples exhibited localized resin agglutination, forming a protective carbonized layer over the graphite fibers, which explains the behavior of the ablative materials after thermal testing.

In conclusion, the investigated Gf/UHTR ablative composite presents superior thermal properties to the GF/Isophen ablative, the UHT resin being a promising binder for applications in passive thermal protection, especially in short or cyclic loading regimes, with potential for use in ablative systems for space vehicles and equipment subjected to combustion or reactive atmospheres.