Short-Term Nutritional Supplementation Accelerates Creatine Kinase Normalization in Adolescent Soccer Players: A Prospective Study with Regression Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Procedures and Measurements

2.3. Supplementation Protocol

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. CK Level at 3 Days

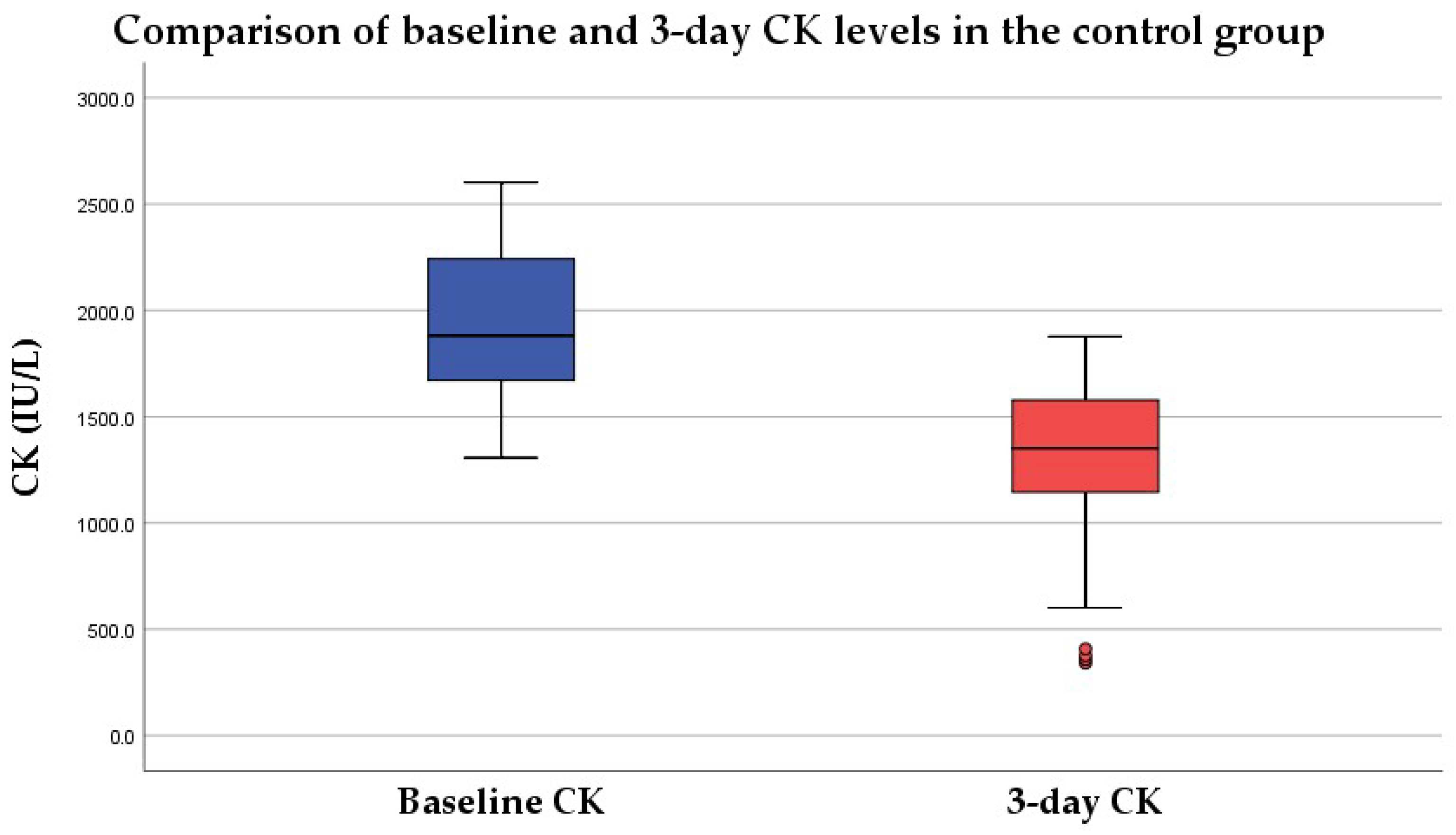

3.1.1. No Intervention Group

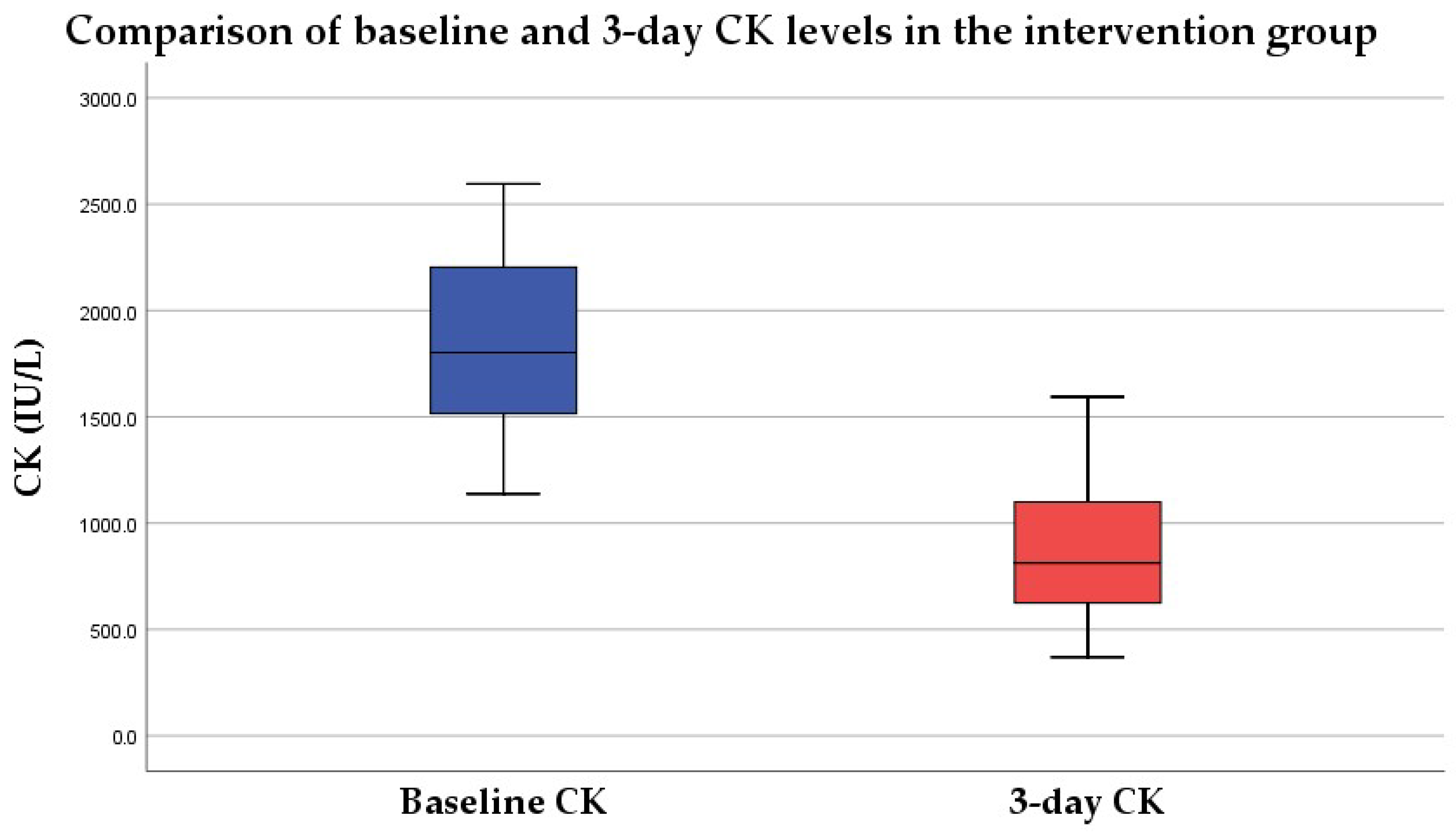

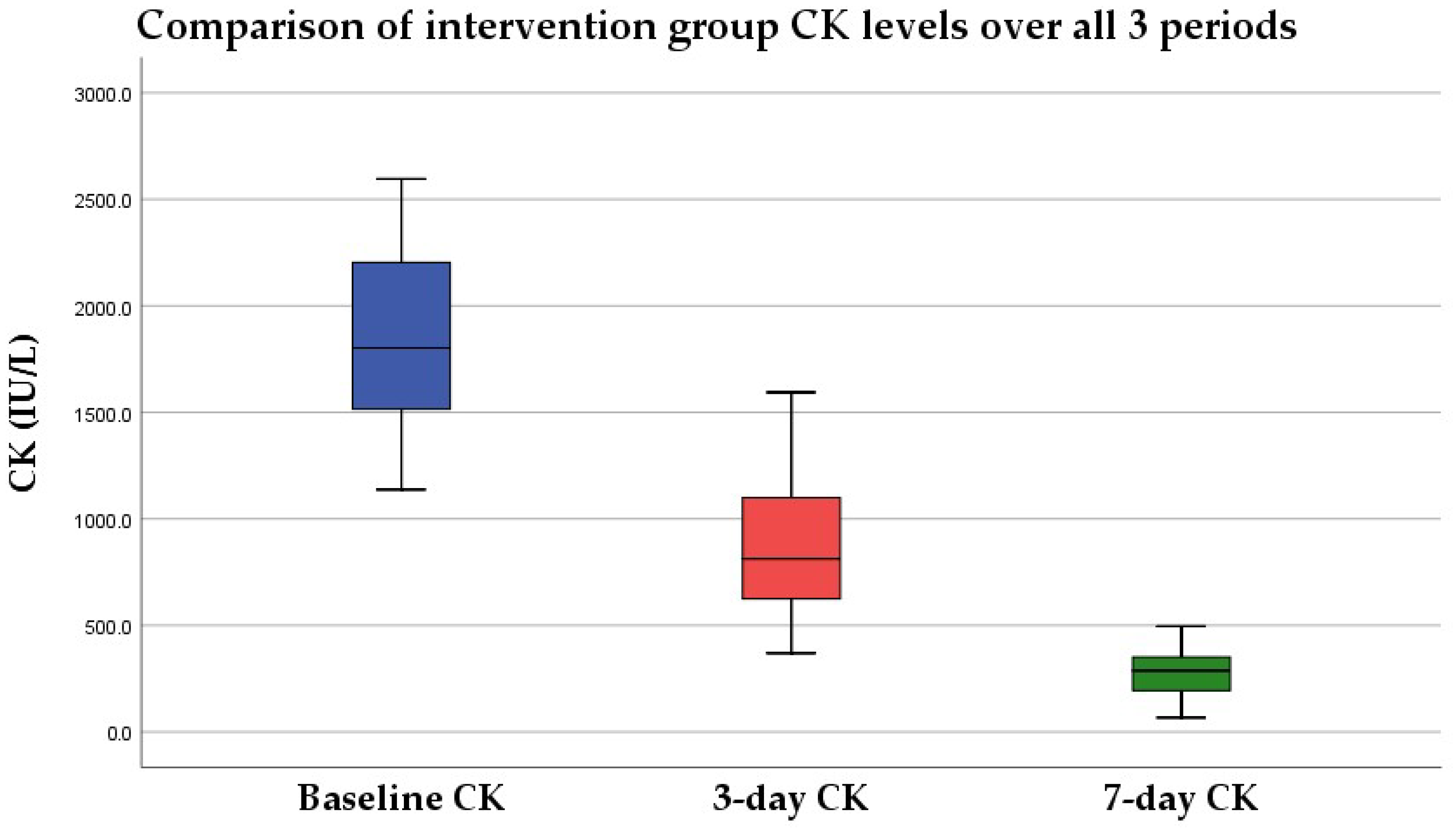

3.1.2. Intervention Group

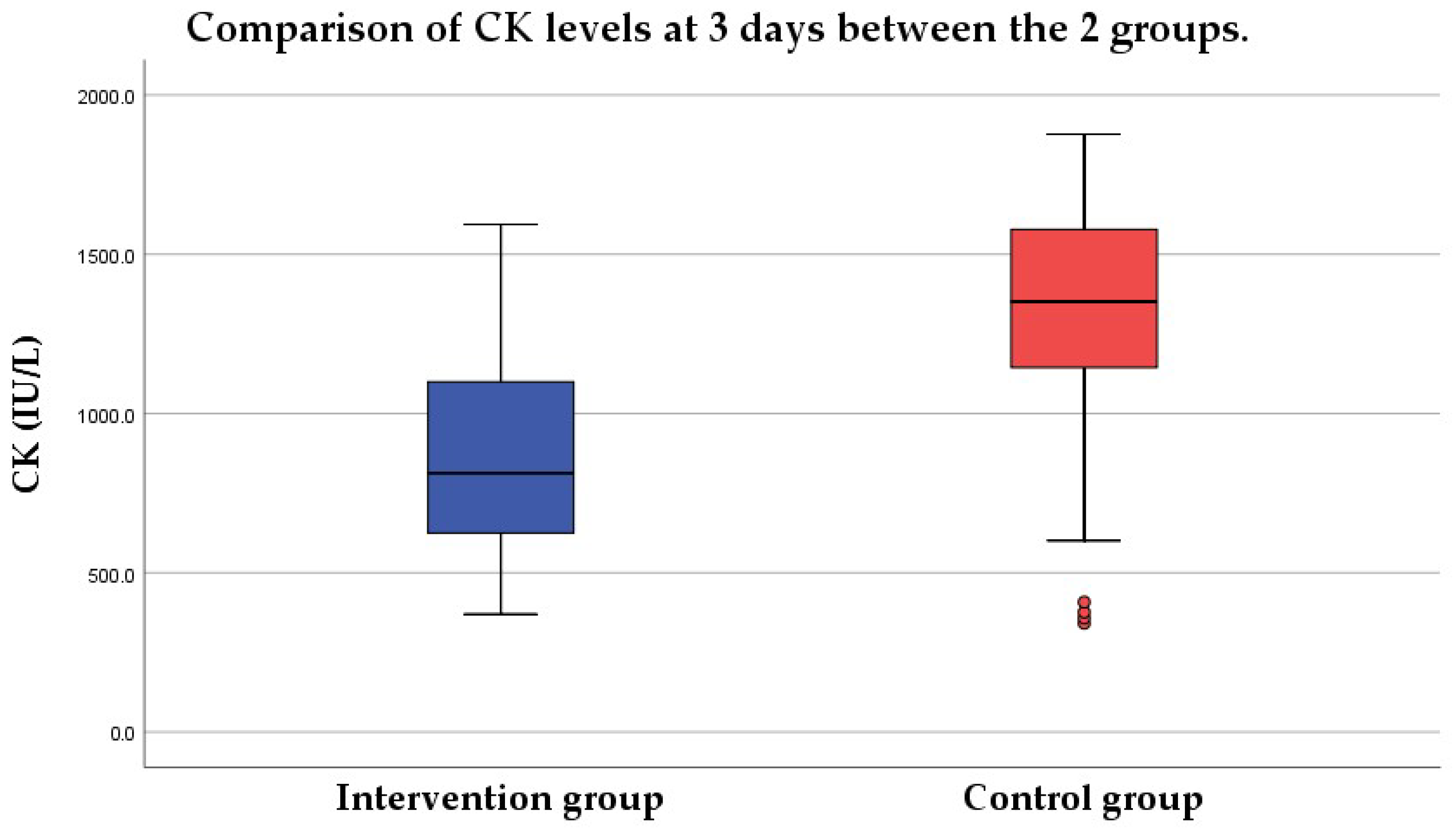

3.1.3. Group Comparison

3.2. CK Level at 7 Days

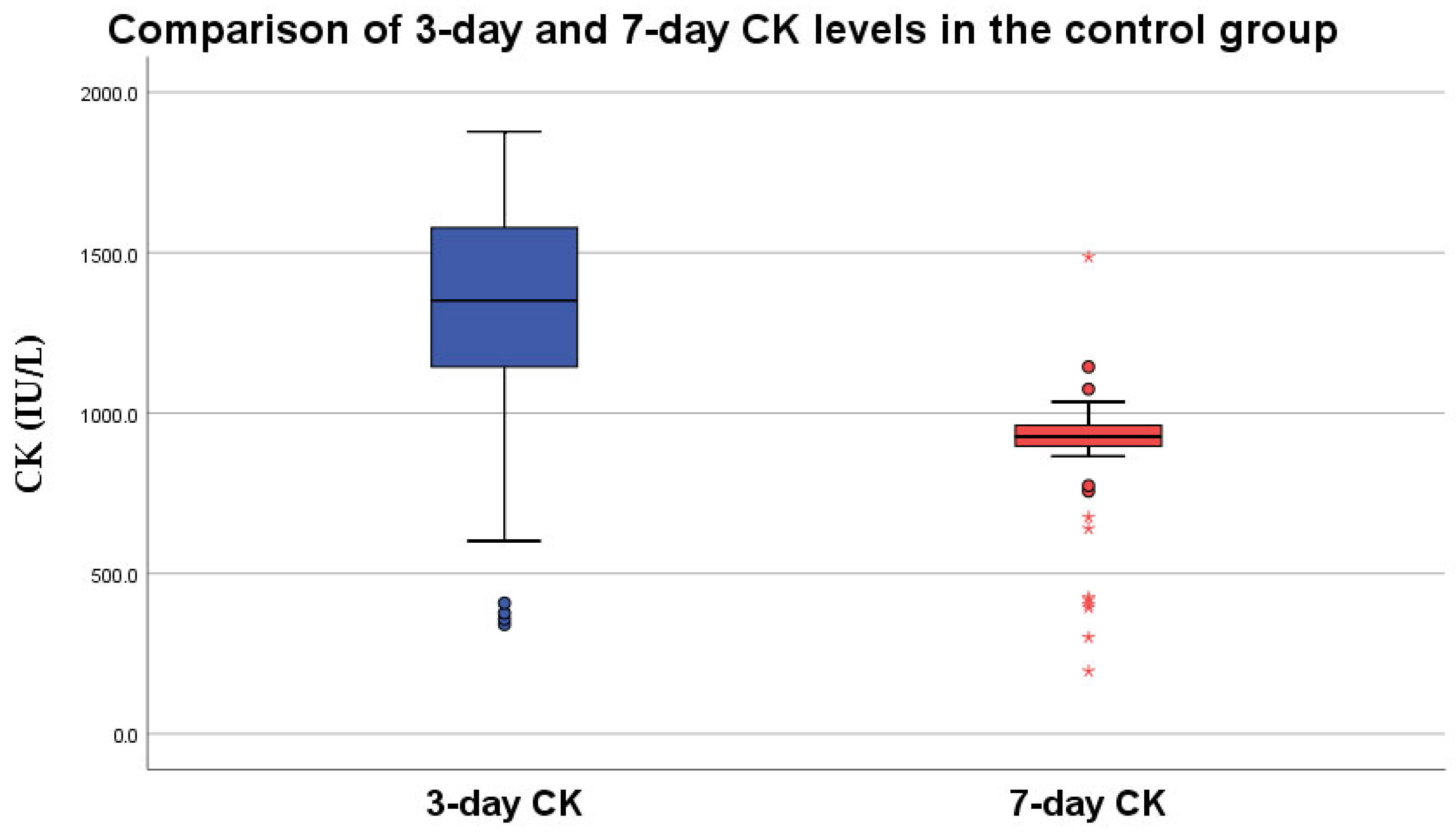

3.2.1. No-Intervention Group

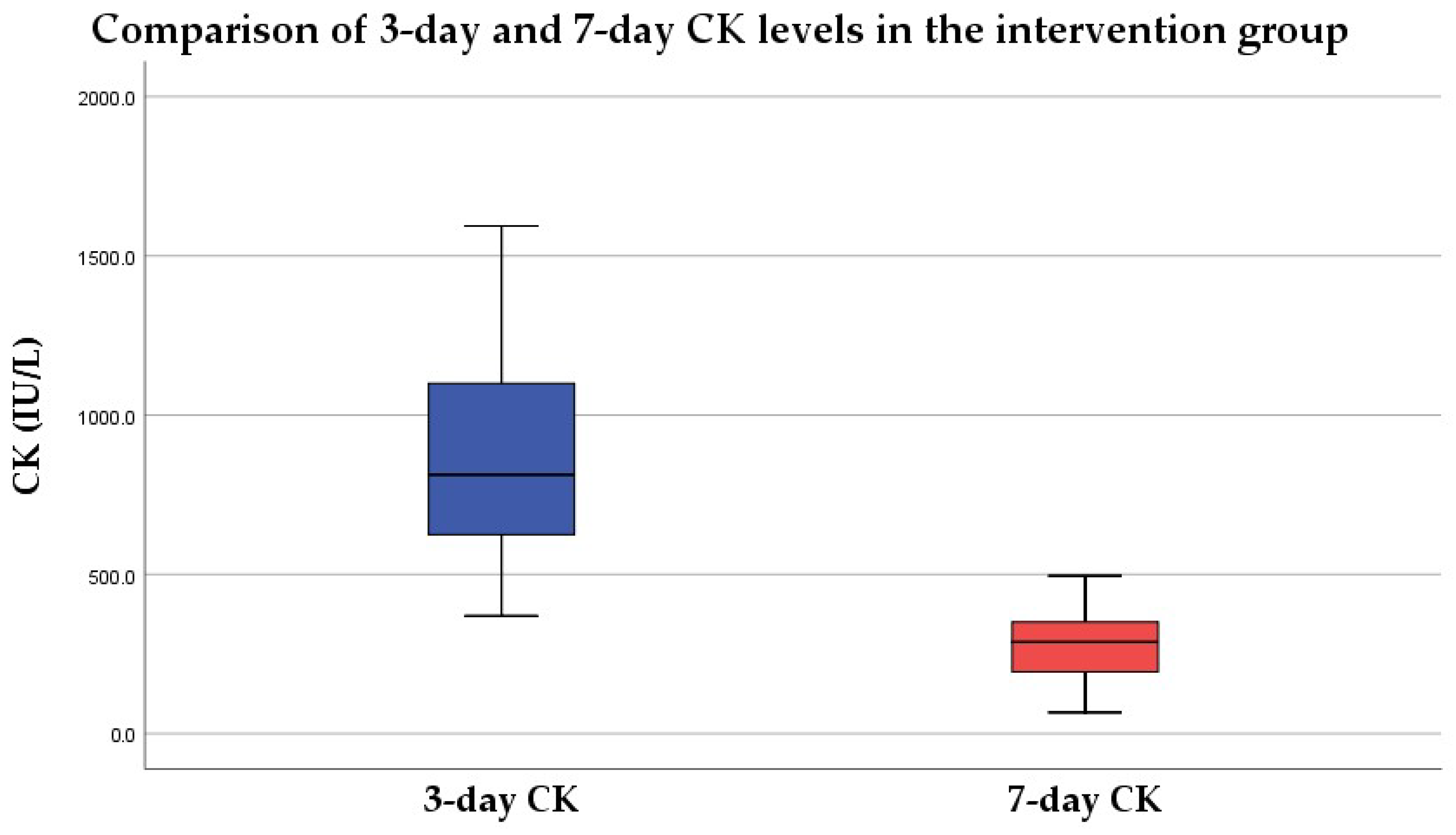

3.2.2. Intervention Group

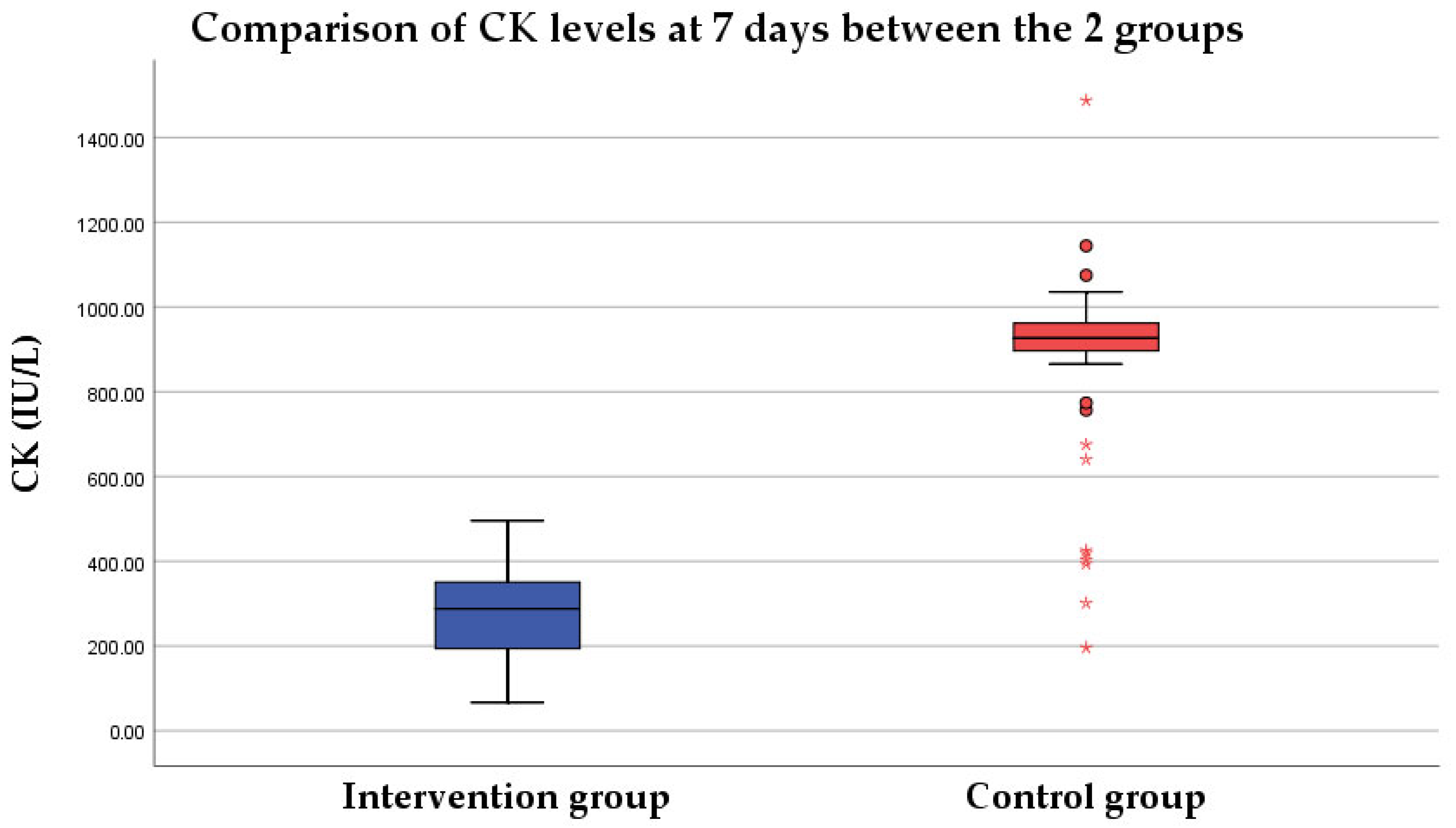

3.2.3. Group Comparison

3.3. CK Regression Model

4. Discussion

4.1. Limitations

4.2. Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus disease 2019 |

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| CK | Creatine kinase |

References

- Aujla, R.S.; Zubair, M.; Patel, R. Creatine Phosphokinase. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546624/ (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Kindermann, W. Creatine Kinase Levels After Exercise. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2016, 113, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, E.S.; Tengesdal, S.; Radke, M.; Rise, K.A.L. Kraftig Stigning i Kreatinkinase Etter Intensiv Trening. Tidsskr. Nor. Legeforening 2019, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baird, M.F.; Graham, S.M.; Baker, J.S.; Bickerstaff, G.F. Creatine-Kinase- and Exercise-Related Muscle Damage Implications for Muscle Performance and Recovery. J. Nutr. Metab. 2012, 2012, 960363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leite, C.D.F.C.; Zovico, P.V.C.; Rica, R.L.; Barros, B.M.; Machado, A.F.; Evangelista, A.L.; Leite, R.D.; Barauna, V.G.; Maia, A.F.; Bocalini, D.S. Exercise-Induced Muscle Damage after a High-Intensity Interval Exercise Session: Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 7082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostapiuk-Karolczuk, J.; Dziewiecka, H.; Bojsa, P.; Cieślicka, M.; Zawadka-Kunikowska, M.; Wojciech, K.; Kasperska, A. Biochemical and Psychological Markers of Fatigue and Recovery in Mixed Martial Arts Athletes during Strength and Conditioning Training. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, E.C.; Fragala, M.S.; Kavouras, S.A.; Queen, R.M.; Pryor, J.L.; Casa, D.J. Biomarkers in Sports and Exercise: Tracking Health, Performance, and Recovery in Athletes. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2017, 31, 2920–2937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saračević, A.; Pekas, D.; Nikler, A.; Lazić, A.; Radišić Biljak, V.; Trajković, N. Post-Exercise Creatine Kinase Variability. Biochem. Med. 2025, 35, 186–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berriel, G.P.; Costa, R.R.; da Silva, E.S.; Schons, P.; de Vargas, G.D.; Peyré-Tartaruga, L.A.; Kruel, L.F.M. Stress and Recovery Perception, Creatine Kinase Levels, and Performance Parameters of Male Volleyball Athletes in a Preseason for a Championship. Sports Med. Open 2020, 6, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mougios, V. Reference Intervals for Serum Creatine Kinase in Athletes. Br. J. Sports Med. 2007, 41, 674–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancaccio, P.; Maffulli, N.; Limongelli, F.M. Creatine Kinase Monitoring in Sport Medicine. Br. Med. Bull. 2007, 81–82, 209–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szigeti, G.; Schuth, G.; Kovács, T.; Revisnyei, P.; Pasic, A.; Szilas, Á.; Gabbett, T.; Pavlik, G. Football Movement Profile Analysis and Creatine Kinase Relationships in Youth National Team Players. Physiol. Int. 2023, 110, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, M.; Chippa, V.; Adigun, R. Rhabdomyolysis. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448168/ (accessed on 22 July 2025).

- Furman, J. When Exercise Causes Exertional Rhabdomyolysis. J. Am. Acad. Physician Assist. 2015, 28, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawson, E.S.; Clarkson, P.M.; Tarnopolsky, M.A. Perspectives on Exertional Rhabdomyolysis. Sports Med. 2017, 47, 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luan, S.; Ji, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, H.; Ouyang, J.; Yang, X.; Zhao, H.; Zhu, B. Real-Time Reconstruction of HIFU Focal Temperature Field Based on Deep Learning. BME Front. 2024, 5, 0037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulios, A.; Papanikolaou, K.; Draganidis, D.; Tsimeas, P.; Chatzinikolaou, A.; Tsiokanos, A.; Jamurtas, A.Z.; Fatouros, I.G. The Effects of Antioxidant Supplementation on Soccer Performance and Recovery: A Critical Review of the Available Evidence. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, E.; Mündel, T.; Barnes, M.J. Nutritional Compounds to Improve Post-Exercise Recovery. Nutrients 2022, 14, 5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.-M.; Li, H.; Chiu, Y.-S.; Huang, C.-C.; Chen, W.-C. Supplementation of L-Arginine, L-Glutamine, Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Folic Acid, and Green Tea Extract Enhances Serum Nitric Oxide Content and Antifatigue Activity in Mice. Evid.-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2020, 2020, 8312647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raizel, R.; Tirapegui, J. Role of Glutamine, as Free or Dipeptide Form, on Muscle Recovery from Resistance Training: A Review Study. Nutrire 2018, 43, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panthi, M.; Subba, R.K.; Raut, B.; Khanal, D.P.; Koirala, N. Bioactivity Evaluations of Leaf Extract Fractions from Young Barley Grass and Correlation with Their Phytochemical Profiles. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.-C.; Hsu, Y.-J.; Shen, S.-Y.; Ho, C.-S.; Huang, C.-C. A Functional Evaluation of Anti-Fatigue and Exercise Performance Improvement Following Vitamin B Complex Supplementation in Healthy Humans, a Randomized Double-Blind Trial. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 20, 1272–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinulingga, A.R.; Slaidiņš, K.; Salajeva, A.; Liepa, A.; Pontaga, I. Effect of Integrative Balance and Plyometric Training on Balance, Ankle Mobility, and Jump Performance in Youth Football Players: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Phys. Act. Health 2025, 9, 146–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teschler, M.; Waranski, M.; Schmitz, B.; Mooren, F.C. Inter-Individual Differences in Muscle Damage Following a Single Bout of High-Intense Whole-Body Electromyostimulation. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1454630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyamoto, T.; Oguma, Y.; Sato, Y.; Kobayashi, T.; Ito, E.; Tani, M.; Miyamoto, K.; Nishiwaki, Y.; Ishida, H.; Otani, T.; et al. Elevated Creatine Kinase and Lactic Acid Dehydrogenase and Decreased Osteocalcin and Uncarboxylated Osteocalcin Are Associated with Bone Stress Injuries in Young Female Athletes. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 18019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrard, J.; Rigort, A.-C.; Appenzeller-Herzog, C.; Colledge, F.; Königstein, K.; Hinrichs, T.; Schmidt-Trucksäss, A. Diagnosing Overtraining Syndrome: A Scoping Review. Sports Health Multidiscip. Approach 2022, 14, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichner, E.R. Exertional Rhabdomyolysis. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2008, 7, 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scalco, R.S.; Snoeck, M.; Quinlivan, R.; Treves, S.; Laforét, P.; Jungbluth, H.; Voermans, N.C. Exertional Rhabdomyolysis: Physiological Response or Manifestation of an Underlying Myopathy? BMJ Open Sport Exerc. Med. 2016, 2, e000151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tietze, D.C.; Borchers, J. Exertional Rhabdomyolysis in the Athlete. Sports Health Multidiscip. Approach 2014, 6, 336–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Jo, M.G.; Kim, S.Y.; Chung, C.G.; Lee, S.B. Dietary Antioxidants and the Mitochondrial Quality Control: Their Potential Roles in Parkinson’s Disease Treatment. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurutas, E.B. The Importance of Antioxidants Which Play the Role in Cellular Response against Oxidative/Nitrosative Stress: Current State. Nutr. J. 2015, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, Z.; Liu, J. Amino Acids Regulating Skeletal Muscle Metabolism: Mechanisms of Action, Physical Training Dosage Recommendations and Adverse Effects. Nutr. Metab. 2024, 21, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.; Wang, W.; Yang, Y.; Lei, Y.; Liu, D.; Wang, X.; Wu, T. The Effect of Metabolites on Mitochondrial Functions in the Pathogenesis of Skeletal Muscle Aging. Clin. Interv. Aging 2022, 17, 1275–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanna, M.; Jaqua, E.; Nguyen, V.; Clay, J.B. Vitamins: Functions and Uses in Medicine. Perm J. 2022, 26, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poulab, E.; Sajedinia, H.; Hafezi, F.; Khazaei, S.; Mabani, M. The Effect of A Four-Week Acute Vitamin C Supplementation on The Markers of Oxidative Stress and Inflammation Following Eccentric Exercise in Active Men. Int. J. Basic Sci. Appl. Res. 2015, 4, 190–195. [Google Scholar]

- Bryer, S.C.; Goldfarb, A.H. Effect of High Dose Vitamin C Supplementation on Muscle Soreness, Damage, Function, and Oxidative Stress to Eccentric Exercise. Int. J. Sport Nutr. Exerc. Metab. 2006, 16, 270–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Righi, N.C.; Schuch, F.B.; De Nardi, A.T.; Pippi, C.M.; de Almeida Righi, G.; Puntel, G.O.; da Silva, A.M.V.; Signori, L.U. Effects of Vitamin C on Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, Muscle Soreness, and Strength Following Acute Exercise: Meta-Analyses of Randomized Clinical Trials. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 2827–2839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.-C.; Ke, C.-Y.; Wu, W.-T.; Lee, R.-P. L-Glutamine Is Better for Treatment than Prevention in Exhaustive Exercise. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1172342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Córdova-Martínez, A.; Caballero-García, A.; Bello, H.J.; Pérez-Valdecantos, D.; Roche, E. Effect of Glutamine Supplementation on Muscular Damage Biomarkers in Professional Basketball Players. Nutrients 2021, 13, 2073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Street, B.; Byrne, C.; Eston, R. Glutamine Supplementation in Recovery from Eccentric Exercise Attenuates Strength Loss and Muscle Soreness. J. Exerc. Sci. Fit. 2011, 9, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, W.B.; Jacinto, J.L.; da Silva, D.K.; Roveratti, M.C.; Estoche, J.M.; Oliveira, D.B.; Balvedi, M.C.W.; da Silva, R.A.; Aguiar, A.F. L-Arginine Supplementation Does Not Improve Muscle Function during Recovery from Resistance Exercise. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2018, 43, 928–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Jiang, Q.; Zhou, X.-Q.; Xu, S.-X.; Feng, L.; Liu, Y.; Jiang, W.-D.; Wu, P.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, J. Effect of Dietary Threonine on Growth Performance and Muscle Growth, Protein Synthesis and Antioxidant-Related Signalling Pathways of Hybrid Catfish Pelteobagrus Vachelli ♀ × Leiocassis Longirostris ♂. Br. J. Nutr. 2020, 123, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Morning | Lunch | Evening |

|---|---|---|

| Tonotil * vial; 1 before breakfast Sod Natural ** 1 vial after breakfast Vitamin C 1000 mg 1 tablet | Magnesium 500 mg 1 tablet Sod Natural ** 1 vial | Sod Natural ** 1 vial Sargenor *** 1 vial |

| Variable | No Dietary Intervention Group (n = 50) | Dietary Intervention Group (n = 50) | Independent-Samples Mann–Whitney U Test (p) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 14 (13–14) | 14 (13–15) | =0.496 |

| Height (cm) | 167 (162–174) | 165 (156–173) | =0.151 |

| Weight (kg) | 48.8 (43.3–57.2) | 53.6 (46.3–56.5) | =0.105 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 18.2 (16.7–19.5) | 18.9 (17.5–19.5) | =0.193 |

| Initial CK (U/L) | 1881 (1670.3–2246.7) | 1802.3 (1511.7–2213.9) | =0.140 |

| Coefficient | Multiple Linear Regression | Lasso Regression |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.0748 | 0.1601 |

| a1 | 0.0236 | 0.0157 |

| a2 | –0.0316 | –0.0000 |

| a3 | –0.0002 | −0.0003 |

| a4 | 0.3077 | 0.2851 |

| a5 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Timnea-Florescu, A.-C.; Dinulescu, A.; Pavelescu, M.-L.; Palcău, A.C.; Prejmereanu, A.; Timnea, O.C.; Vîrgolici, H.; Nemes, A.F.; Nemes, R.M. Short-Term Nutritional Supplementation Accelerates Creatine Kinase Normalization in Adolescent Soccer Players: A Prospective Study with Regression Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010183

Timnea-Florescu A-C, Dinulescu A, Pavelescu M-L, Palcău AC, Prejmereanu A, Timnea OC, Vîrgolici H, Nemes AF, Nemes RM. Short-Term Nutritional Supplementation Accelerates Creatine Kinase Normalization in Adolescent Soccer Players: A Prospective Study with Regression Analysis. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010183

Chicago/Turabian StyleTimnea-Florescu, Andreea-Consuela, Alexandru Dinulescu, Mirela-Luminita Pavelescu, Alexandru Cosmin Palcău, Ana Prejmereanu, Olivia Carmen Timnea, Horia Vîrgolici, Alexandra Floriana Nemes, and Roxana Maria Nemes. 2026. "Short-Term Nutritional Supplementation Accelerates Creatine Kinase Normalization in Adolescent Soccer Players: A Prospective Study with Regression Analysis" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010183

APA StyleTimnea-Florescu, A.-C., Dinulescu, A., Pavelescu, M.-L., Palcău, A. C., Prejmereanu, A., Timnea, O. C., Vîrgolici, H., Nemes, A. F., & Nemes, R. M. (2026). Short-Term Nutritional Supplementation Accelerates Creatine Kinase Normalization in Adolescent Soccer Players: A Prospective Study with Regression Analysis. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 183. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010183