Magnetic Field Simulation of Demagnetization Process in Complex Ferromagnetic Cavity Structures

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Analysis of Dynamic Demagnetization Mechanisms

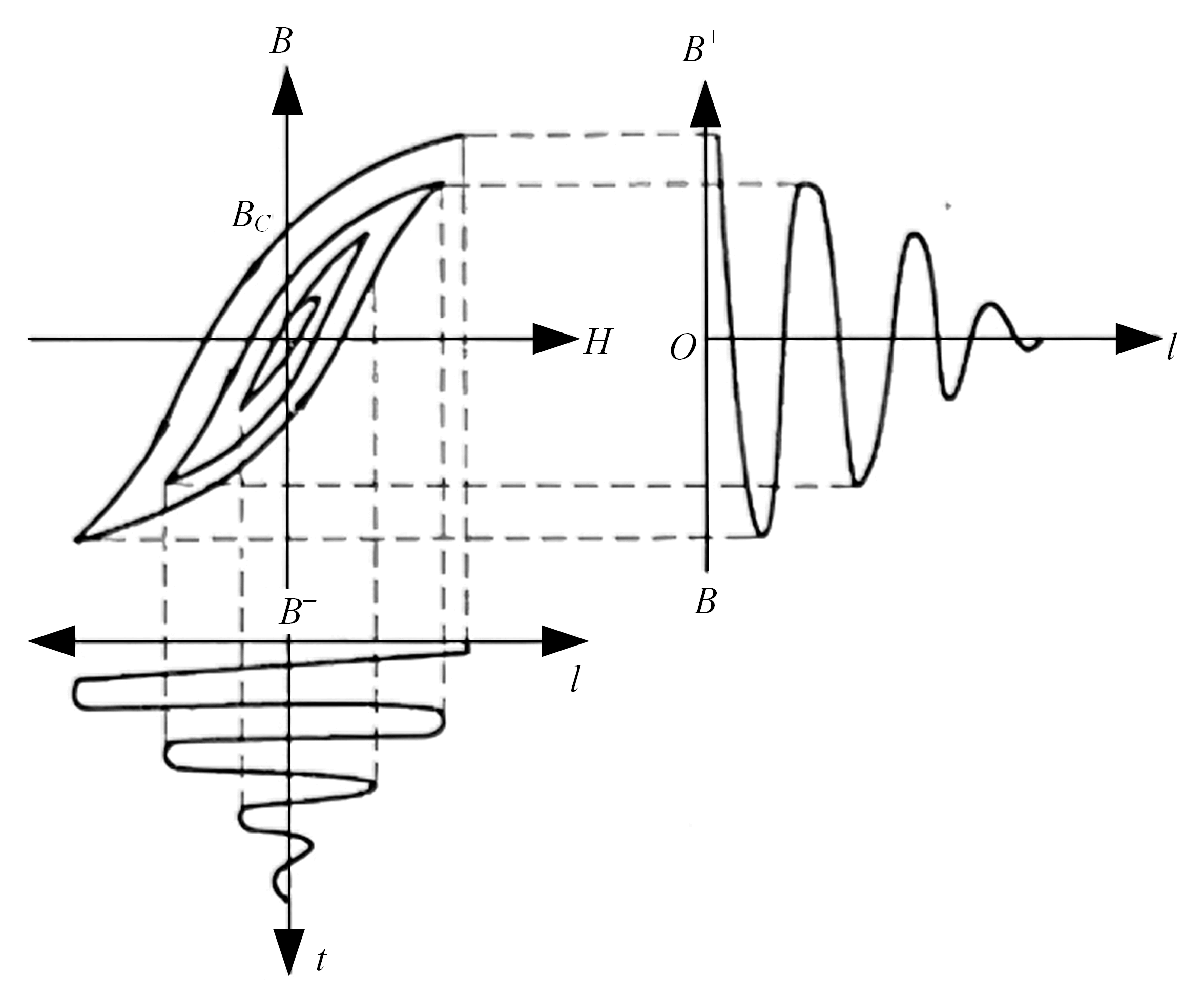

2.1. Hysteresis Effect

2.2. Eddy Current Effect

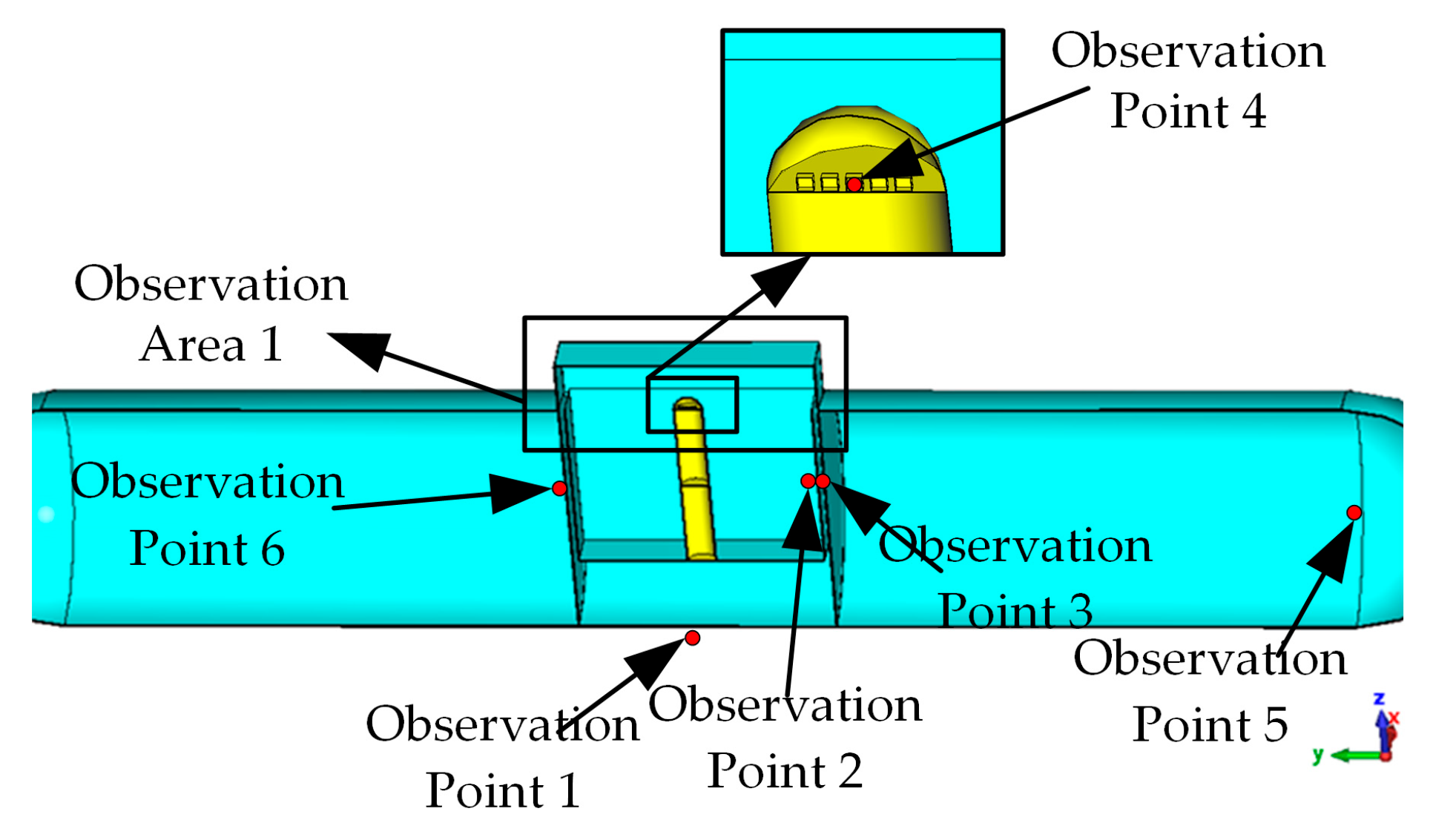

3. Modeling of Dynamic Demagnetization Processes for Complex Ferromagnetic Cavity Structures

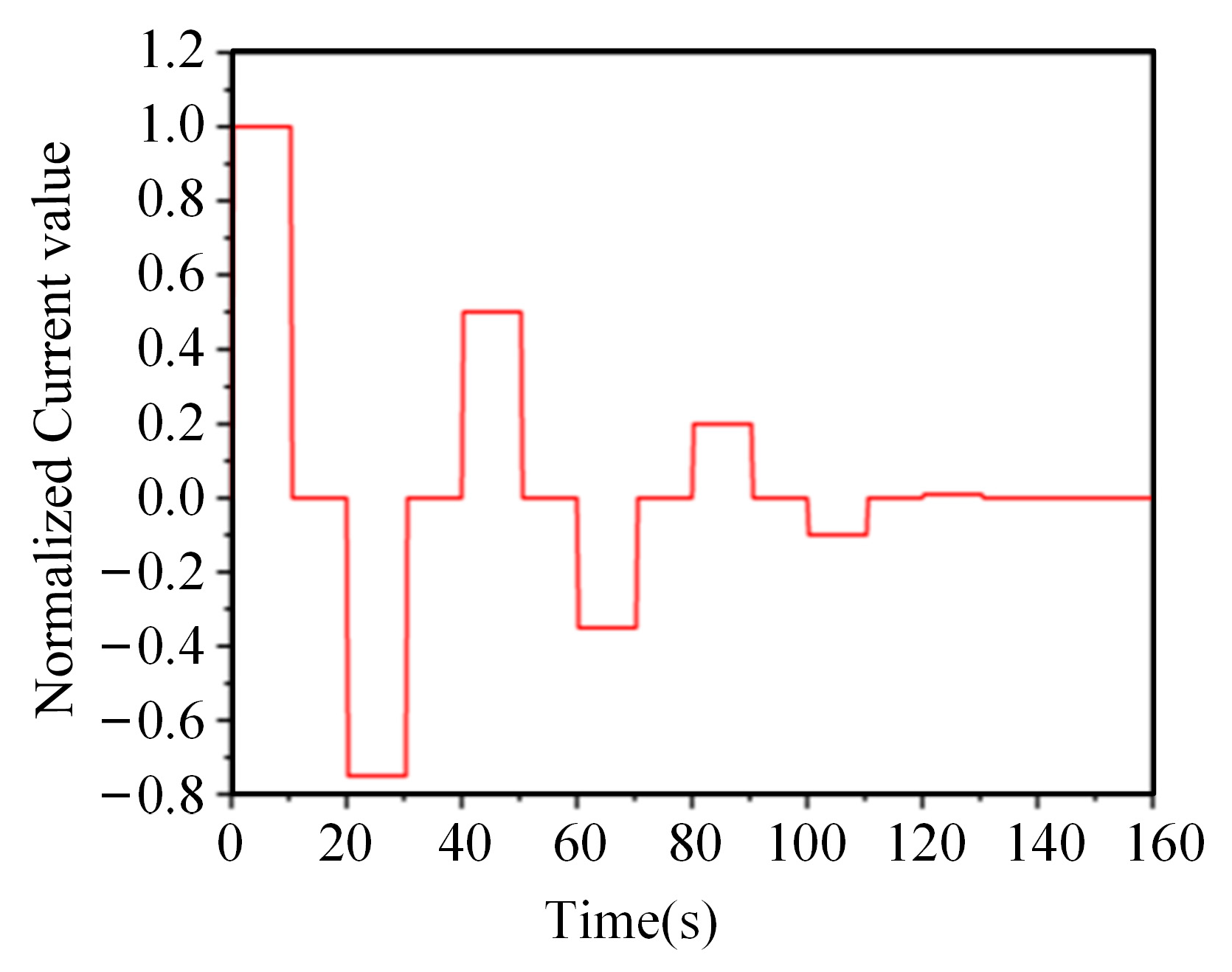

4. Simulation of Magnetic Fields During Demagnetization Processes for Complex Ferromagnetic Cavity Structures

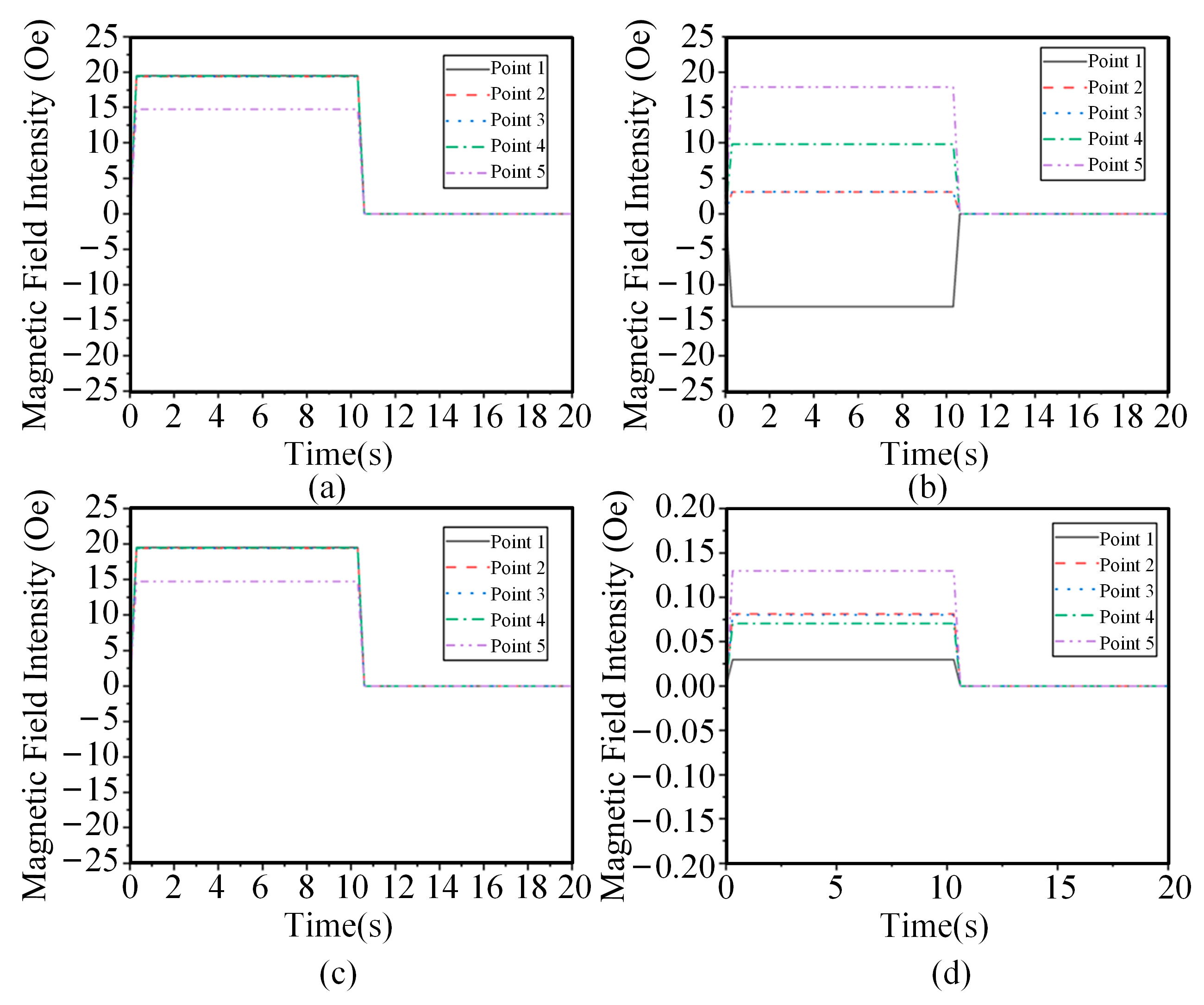

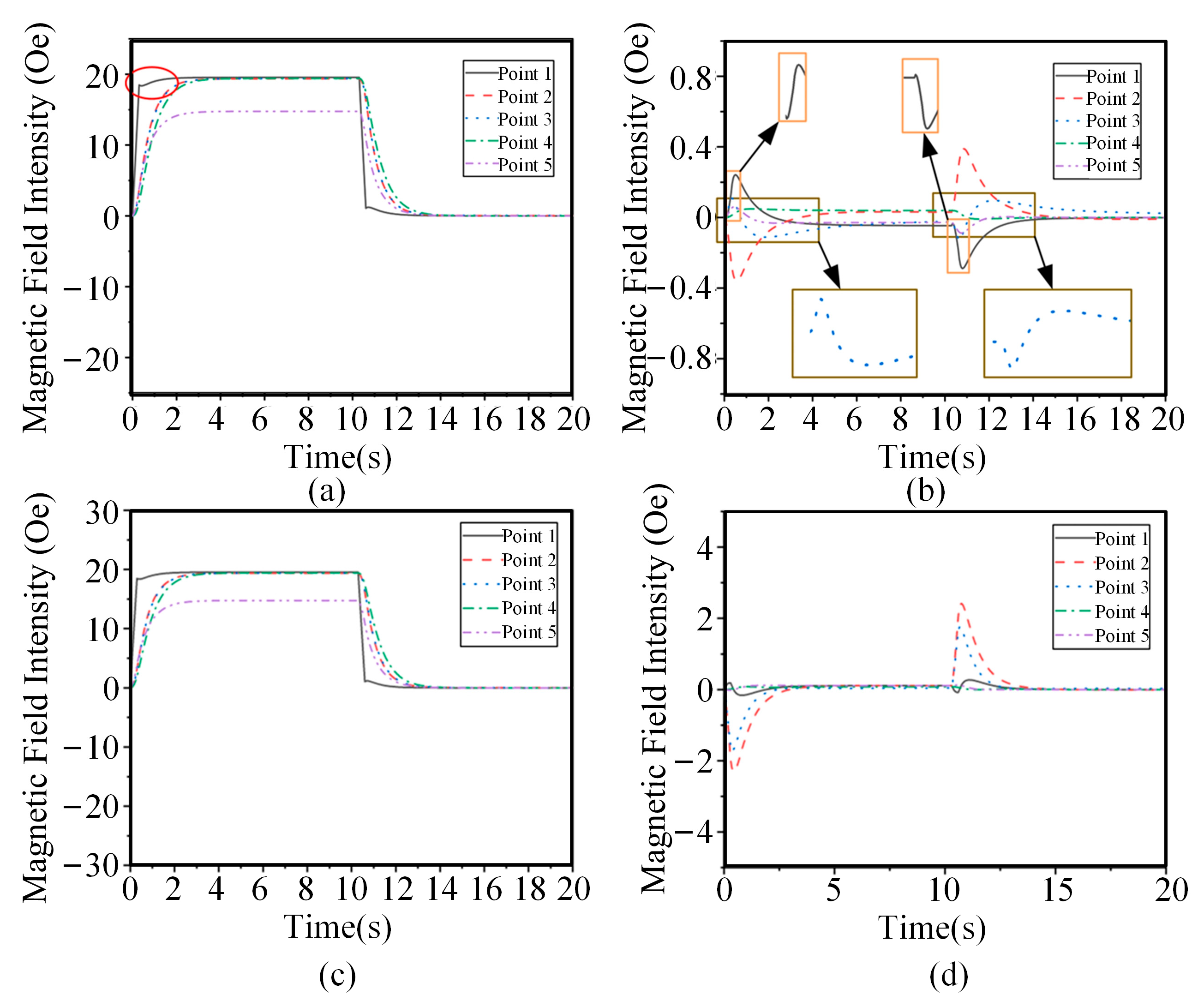

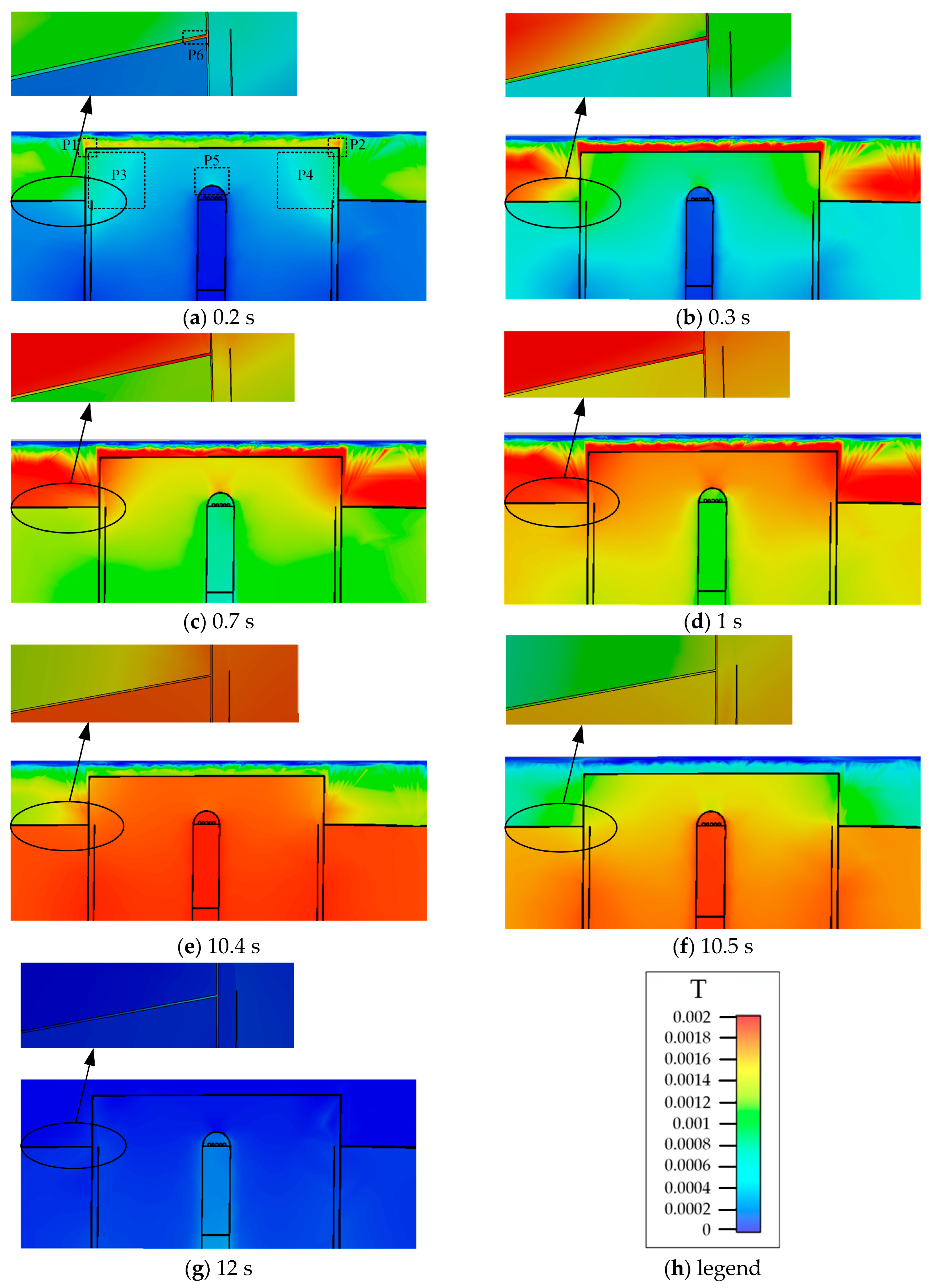

4.1. Time-Varying Characteristics of Magnetic Fields at Different Positions

4.2. Effects of Eddy Currents on Time-Varying Characteristics of Magnetic Fields

4.3. Analysis of Magnetic Field Intensity at Different Positions Inside Complex Ferromagnetic Cavity Structures and Eddy Current Effects

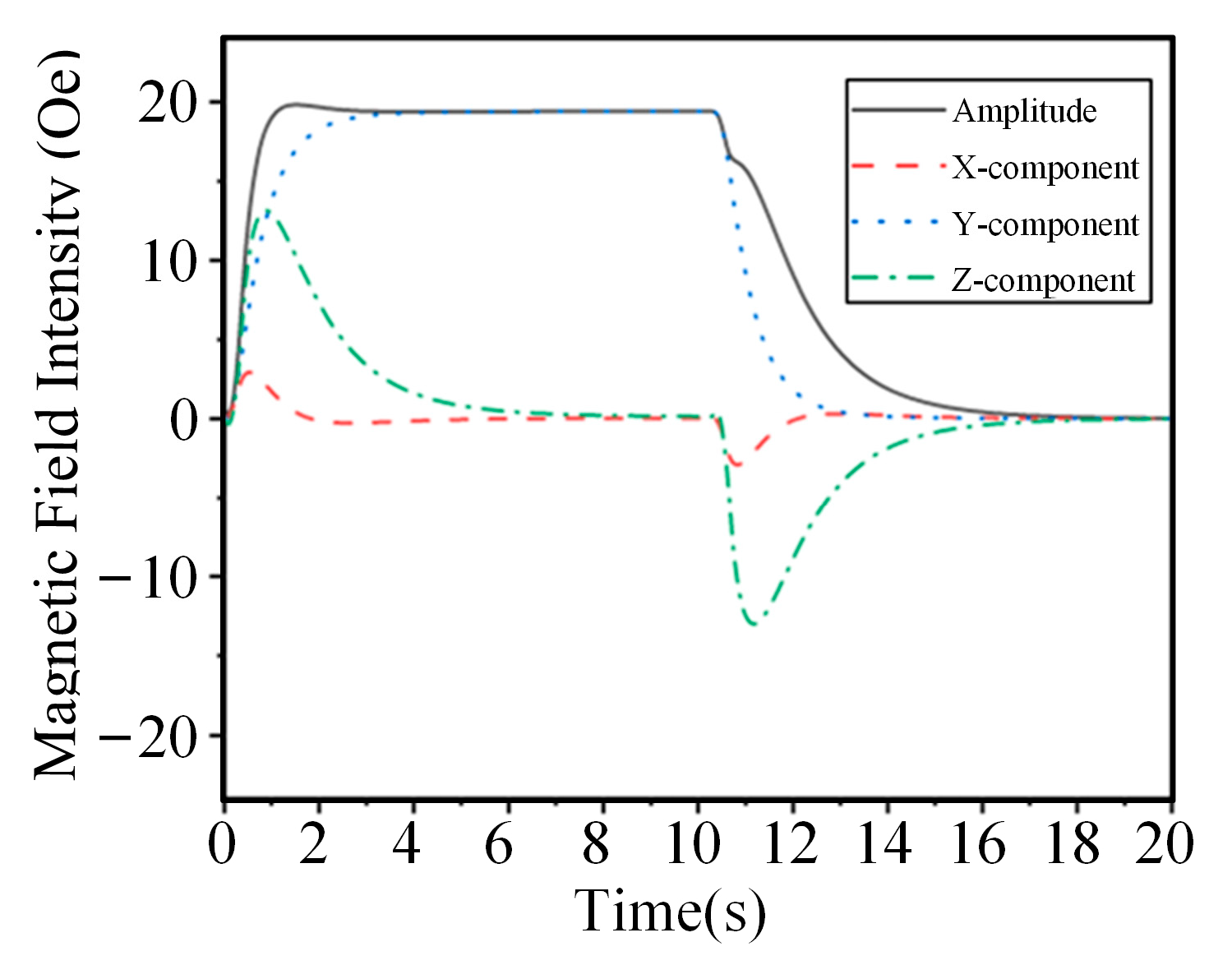

4.4. Analysis of Three-Dimensional Magnetic Field Time-Varying Characteristics of Complex Ferromagnetic Cavity Structures

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Modi, A.; Kazi, F. Magnetic-Signature Prediction for Efficient Degaussing of Naval Vessels. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2020, 56, 6000606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, V.M.; Alejandro, A.M. Using Genetic Algorithms for Compensating the Local Magnetic Perturbation of a Ship in the Earth’s Magnetic Field. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2005, 47, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oded, Y.; Gregory, Z.; Touvia, M. Detection of the Electromagnetic Field Induced by the Wake of a Ship Moving in a Random Sea of Finite Depth. J. Eng. Math. 2011, 70, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, K.G.; Tan, E.L.; Grimes, C.A.; Shao, R. Removal of Temperature and Earth’s Field Effects of a Magnetoelastic pH Sensor. IEEE Sens. J. 2008, 8, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, K.; Sasada, I.; Tashiro, K. High-Performance Bench-Top Cylindrical Magnetic Shield with Magnetic Shaking Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2002, 38, 3335–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gontarz, S.; Radkowski, S. Impact of Various Factors on Relationships between Stress and Eigen Magnetic Field in a Steel Specimen. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2012, 48, 1143–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, S.J.; Rawlins, P.G. A Multi-Influence Range with Electromagnetic Modeling; Ultra Electronics Limited: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Zolotarevskii, Y.M.; Bulygin, F.V.; Ponomarev, A.N.; Narchev, V.A.; Berezina, L.V. Methods of Measuring the Low Frequency Electric and Magnetic Fields of Ships. Meas. Tech. 2005, 48, 1140–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikkerink, D.; Mor, A.R.; Polinder, H.; Ross, R. Magnetic Signature Reduction by Converter Switching Frequency Modulation in Degaussing Systems. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 74103–74110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitin, V.F.; Smirnov, N.N.; Smirnova, M.N.; Tyurenkova, V.V. On-Board Electronic Devices Safety Subject to High-Frequency Electromagnetic Radiation Effects. Acta Astronaut. 2017, 135, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacBain, J.A. Some Aspects of Vehicle Degaussing. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1993, 29, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikkerink, D.; Mor, A.R.; Polinder, H.; Ross, R. Converter Design for High Temperature Superconductive Degaussing Coils. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 128656–128663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Lu, J.; Liu, Y. Research Progress of Electromagnetic Launch Technology. IEEE Trans. Plasma Sci. 2019, 47, 2197–2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, N.B. Shipboard Degaussing Installations. Electr. Eng. 1949, 68, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, N.S.; Jeung, G.; Jung, S.S.; Yang, C.S.; Chung, H.J.; Kim, D.H. Efficient Methodology for Optimizing Degaussing Coil Currents in Ships Utilizing Magnetomotive Force Sensitivity Information. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2012, 48, 419–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gordon, B. Degaussing—The Demagnetisation of Ships. Electron. Power 1984, 6, 473–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J.J. Reduction of a Ship’s Magnetic Field Signatures; Morgan & Claypool Publishers: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2008; pp. 237–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmes, J.J. Exploitation of a Ship’s Magnetic Field Signatures; Morgan & Claypool Publishers: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2006; pp. 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruoho, S.; Arkkio, A. Partial Demagnetization of Permanent Magnets in Electrical Machines Caused by an Inclined Field. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2008, 44, 1773–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udpa, S.S.; Sun, Y.S.; Lord, W. Alternative Demagnetization Curve Representations for the Finite Element Modeling of Residual Magnetism. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1988, 24, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.X.; Brug, J.; Goldfarb, R. Demagnetizing Factors for Cylinders. IEEE Trans. Magn. 1991, 27, 3601–3619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.X.; Pardo, E.; Sanchez, A. Fluxmetric and Magnetometric Demagnetizing Factors for Cylinders. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 2006, 306, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parq, J.H. Magnetometric Demagnetization Factors for Hollow Cylinders. J. Magn. 2017, 22, 550–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dassault Systèmes. CST Studio Suite [Software]. 2025. Available online: https://www.3ds.com/products/simulia/cst-studio-suite (accessed on 25 July 2023).

| Cabin | Length (m) | 100 |

| Diameter (m) | 10 | |

| Shell thickness (m) | 0.04 | |

| Partition | Thickness (m) | 0.02 |

| Storage device | Length(m) | 14 |

| Width (m) | 6 | |

| Height (m) | 10 | |

| Cylindrical structure | Length (m) | 10 |

| Diameter (m) | 1.2 | |

| Shell thickness (m) | 0.01 |

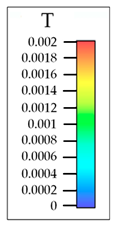

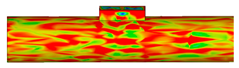

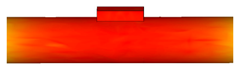

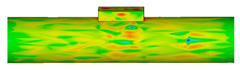

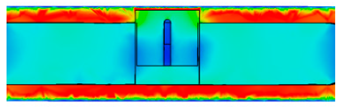

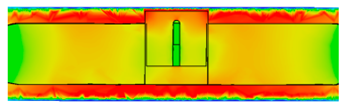

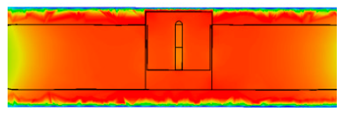

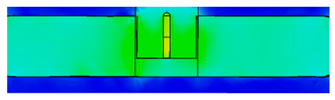

| Time (s) | Internal Magnetic Fields in Complex Ferromagnetic Cavity Structures | Legend |

|---|---|---|

| 0.3 |  |  Magnetic (T) |

| 0.5 |  | |

| 1 |  | |

| 3.5 |  | |

| 10.3 |  | |

| 10.5 |  | |

| 10.9 |  |

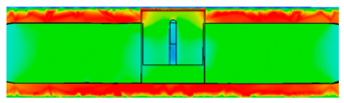

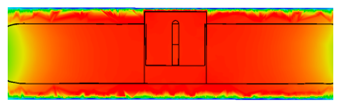

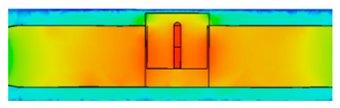

| Time (s) | Internal Magnetic Fields in Complex Ferromagnetic Cavity Structures | Legend |

|---|---|---|

| 0.3 |  |  Magnetic (T) |

| 0.5 |  | |

| 1 |  | |

| 3.5 |  | |

| 10.3 |  | |

| 10.5 |  | |

| 10.9 |  | |

| 13 |  | |

| 160 |  |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Guo, T.; Lu, C.; Chen, M. Magnetic Field Simulation of Demagnetization Process in Complex Ferromagnetic Cavity Structures. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010176

Guo T, Lu C, Chen M. Magnetic Field Simulation of Demagnetization Process in Complex Ferromagnetic Cavity Structures. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):176. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010176

Chicago/Turabian StyleGuo, Tao, Chengjin Lu, and Meng Chen. 2026. "Magnetic Field Simulation of Demagnetization Process in Complex Ferromagnetic Cavity Structures" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010176

APA StyleGuo, T., Lu, C., & Chen, M. (2026). Magnetic Field Simulation of Demagnetization Process in Complex Ferromagnetic Cavity Structures. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 176. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010176