1. Introduction

In Poland, the issue of methane emissions from mining operations is of particular importance due to the large number of coal mines exploiting seams with a high level of methane hazard [

1]. The urgency of addressing this problem has been further reinforced by the ambitious climate goals set by the European Union, as outlined in the EU Strategy to Reduce Methane Emissions [

2].

In addition to the obligations arising from international climate agreements, economic factors, production forecasts, and the gradual depletion of operational hard coal reserves in Poland also play a crucial role [

3,

4,

5]. The scenario of systematic restructuring followed by the closure of successive hard coal mines in the region over the next three decades is already certain and has become an integral part of the social agreement. Despite its challenges, the planned restructuring of the sector also opens new opportunities for methane capture and utilization for electricity generation [

6,

7], even after the cessation of mining activities. This extends the role of mines as potential facilities for methane recovery from strata disturbed by coal extraction. Researchers emphasize that, at this stage, thorough identification and improvement of solutions aimed at reducing methane emissions from mines are of critical importance [

8,

9,

10,

11]. This issue remains significant both in actively operating mines, due to mining safety concerns [

12,

13,

14], the costs of preventive measures [

15], and potential downtime caused by exceeding permissible methane concentrations [

16], and in mines undergoing closure.

One of the significant factors affecting recorded methane concentrations is the fluctuation in atmospheric pressure, which leads to the phenomenon known as gob-breathing [

17]. Although this phenomenon has been practically recognized for many years and has been studied locally in selected areas of longwall mining [

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25], few researchers have undertaken comprehensive quantitative investigations. This difficulty arises from the challenge of isolating the influence of atmospheric pressure in conditions where numerous other factors affect methane concentration variations. In [

20], the author addresses the issue of methane emission prediction, focusing primarily on the role of geological conditions and the intensity of mining operations. The authors of [

21] also highlight the significant importance of ventilation and organizational factors that affect the level of methane hazard. In [

22], the author highlights the significant influence of absolute pressure variations on methane concentration in workings of methane-prone coal mines. It is emphasized that prolonged drops in barometric pressure—particularly those preceding approaching storms—may promote increased methane emissions and elevate the associated risk. The study also notes that while forecasting methods based on recorded barometric decreases are effective under slow pressure changes, they do not provide a complete assessment of hazard when dynamic fluctuations occur due to production processes. The author demonstrates that monitoring absolute air pressure, both underground and at the surface of the mine, which is now standard practice, serves as an effective tool for early warning of methane hazards. Similar conclusions are drawn by the authors of [

23], who, based on a monitored case, note that even when the amplitude of barometric pressure changes reaches ±0.5%, the measured methane concentration can increase from a minimum of 1% to 1.5%. However, the authors focus primarily on modeling this phenomenon using CFD simulations. The authors of [

25] note that gas emission in the goaf is inversely proportional to changes in atmospheric pressure, with rapid surface pressure variations causing corresponding fast increases or decreases in emission. They propose a multiple-parameter goaf gas emission model using equivalent porosity and permeability, with PSO applied to determine parameters. The results indicate that the model has potential for practical application, although deviations in peak gas concentrations remain and require further investigation.

Recent studies suggest that an effective approach is to analyze methane hazard in mines undergoing closure [

26,

27,

28,

29,

30].

The authors of [

26] note that methane migration toward the surface in closed mines can pose a hazard for many years after closure, focusing particularly on mines closed by flooding. Special attention should be paid to the presented model illustrating the ratio of average methane emission from goafs, covering both the period of active mining and the years following its cessation. The model presented in [

26], as well as the model from [

20], was tested during the closure of a Anna section of the Rydultowy–Anna coal mine by Duda & Krzemień [

27]. The results confirmed usefulness of both models in forecasting methane emissions from closed mines, indicating that the model can be considered a reliable tool for predicting methane emissions from closed underground coal mines exploited by longwall mining. However, the forecasts indicate average methane values and do not account for more dynamic variations that may occur under the influence of rapid or intensive atmospheric pressure fluctuations. Duda, additionally in [

28], investigated the influence of atmospheric pressure changes on methane emissions in caved goafs. The study highlights that pressure drops can lead to additional methane release, which can be captured by drainage systems, improving their efficiency. It also points out the issue of methane migration through fracture networks in the rock mass within complex goaf systems, which may increase the hazard in actively exploited sections of the mine. In [

29], the authors additionally present an experimental study on methane release from coal under high hydrostatic pressure, simulating flooded coal mine conditions. The results indicate that the amount of CH

4 released depends on hydrostatic pressure, with higher pressure leading to greater gas release. Furthermore, Karacan [

30] presents a reservoir modeling study of methane extraction from an abandoned room-and-pillar coal mine (Buck Creek, Indiana, USA), showing that the captured gas originates from accumulation in mine voids, coal emissions, and seal leakages, with coal emissions being the dominant source.

The phenomenon of gas migration due to atmospheric pressure drops was also investigated by Wrona et al. [

31,

32], who analyzed gas emissions around shafts of long-closed mines, where most of the infrastructure had already been dismantled. The authors noted that, in the context of climate change and increasingly extreme weather events, deeper pressure drops can be expected, which are the main cause of gas flow from underground workings to the surface. The study presented the results of numerical simulations of CO

2 and CH

4 distribution near a closed shaft under projected barometric changes. The results indicate that deeper pressure drops may lead to a wider spread of gases around the shaft, especially along the prevailing wind direction.

It should be noted that focusing on closed or decommissioned mines is particularly advantageous when analyzing this phenomenon, as this approach minimizes the influence of additional factors on methane emissions, such as ongoing mining activities, changes in the aerodynamic potential field caused by ventilation disturbances, or alterations in the structure and aerodynamic resistance of mine workings. Moreover, linking the increase in methane emissions with atmospheric pressure drops and attempting to model this relationship may be applicable not only to closed mines but also to active mining operations.

The aim of the research presented in this article was to provide a detailed analysis of the impact of dynamic atmospheric pressure drops on methane emissions from a mine undergoing closure, with particular emphasis on identifying and quantifying the observed relationships.

2. Methods

For the study of the impact of atmospheric pressure fluctuations on methane concentrations in a mining facility, a mine SRK S.A., KWK „Krupiński” in Poland undergoing closure was selected. This mine was chosen primarily due to the significant methane levels recorded in the years preceding its closure.

The selected mine constituted an independent operation, not connected to any other facility in the period preceding its closure, which reflects the standard practice for most mining sites in Poland. This organizational and infrastructural isolation made it possible to more effectively capture the phenomenon of interest, as the additional factors previously mentioned were absent. Such conditions would have significantly complicated the analysis in the case of closing only one section of a previously merged mining complex. Another advantage of the selected facility was the high methane concentrations recorded in the years preceding its decommissioning; its annual absolute methane emission remained stable at approximately 75 million m

3 CH

4 [

31], placing it among the most methane-intensive coal mines in Poland. Furthermore, the smooth transition into the decommissioning process, initiated immediately after extraction from the last longwall had ceased, made it possible to conduct detailed monitoring of the entire process from its very first days.

During the decommissioning period, the authors compiled an extensive database that included continuous measurements of methane concentrations and atmospheric pressure from telemetry centers (covering both sensors installed in the workings and at the methane drainage station), daily reports on methane capture behind stoppings in individual areas, and information allowing for the ongoing update of the closure plan location along with updated ventilation network diagrams as the process progressed.

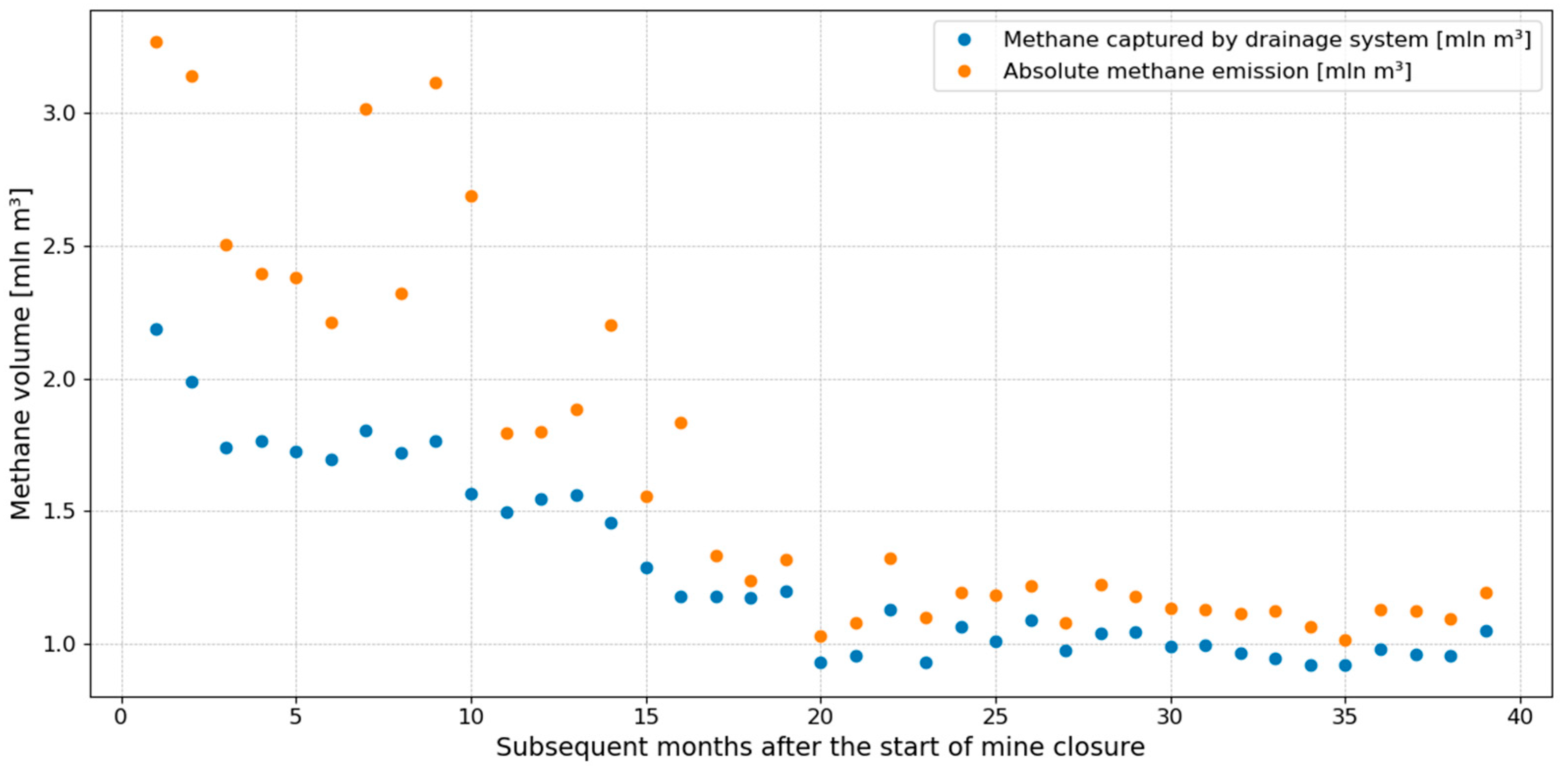

Figure 1 presents the monthly absolute methane emission and methane capture by the drainage system, measured from the first month after the cessation of mining operations. During the initial decommissioning period, lasting approximately one year, a sharp decline in the methane recorded by the system is clearly observed, after which the values stabilize. Subsequently, roughly after one year, the methane drainage efficiency increases and maintains a relatively steady level, ranging from 85% to 95%.

The process illustrated in

Figure 1, though observed across the entire mine undergoing decommissioning, is similar to the model of methane release into the longwall during mining operations and, after their completion, into the goaf, as described by Krause & Pokryszka [

26]. However, the percentage decrease in methane emissions is markedly smaller than in the model presented in the publication of these authors.

For the analysis, a year of measurements corresponding to the ‘middle’ stage of closure was selected, which was characterized by good stability of conditions in the facility due to a slowdown in the closure process for political and legal reasons, facilitating the accuracy of the conducted research.

The data used in the present analyses were obtained from automatic telemetry sensors in the mine. Methane concentration analysis was conducted using data from a CSM-1 sensor, which measured gas levels in the drainage pipeline (during the decommissioning stage, when the workings had already been sealed). The sensor is characterized by a resolution of 1% and an accuracy of ±3% CH4 within the operating range of 5–100% CH4, employing a conductometric measurement method. The sampling frequency was ≤5 s. Atmospheric pressure was measured using a microprocessor-based MSP-1 weather sensor, located in the dispatcher’s office and connected to the telemetry control unit. The sensor operated within the range of 800–1110 hPa, with a sampling frequency of 12 s. The system allowed for continuous measurement of the mine atmosphere, including, among others, methane concentrations and pressure, which is a standard practice in Polish mines. The measurement databases, in the form of CSV report files, were generated by the SWuP-3 methane monitoring dispatcher support system.

The aforementioned sensor reports are structured and take the form of text documents containing a series of records, generated each time a change in the recorded methane concentration occurs. A single sensor record has the following format: Time [dd:mm:yyyy hh:mm:ss]—Measurement [xx %CH

4 or xxx.x hPa]—Persistence time [hh:mm:ss]—More info [e.g., sensor maintenance]. Sample excerpts of the sensor reports are presented in

Figure 2. Due to the large size of the database, analyses were conducted using the Python 3.12.1 programming language (Python Software Foundation, Beaverton, OR, USA) and Tibco Statistica 13.5.0 software (Tibco Software Inc., San Ramon, CA, USA).

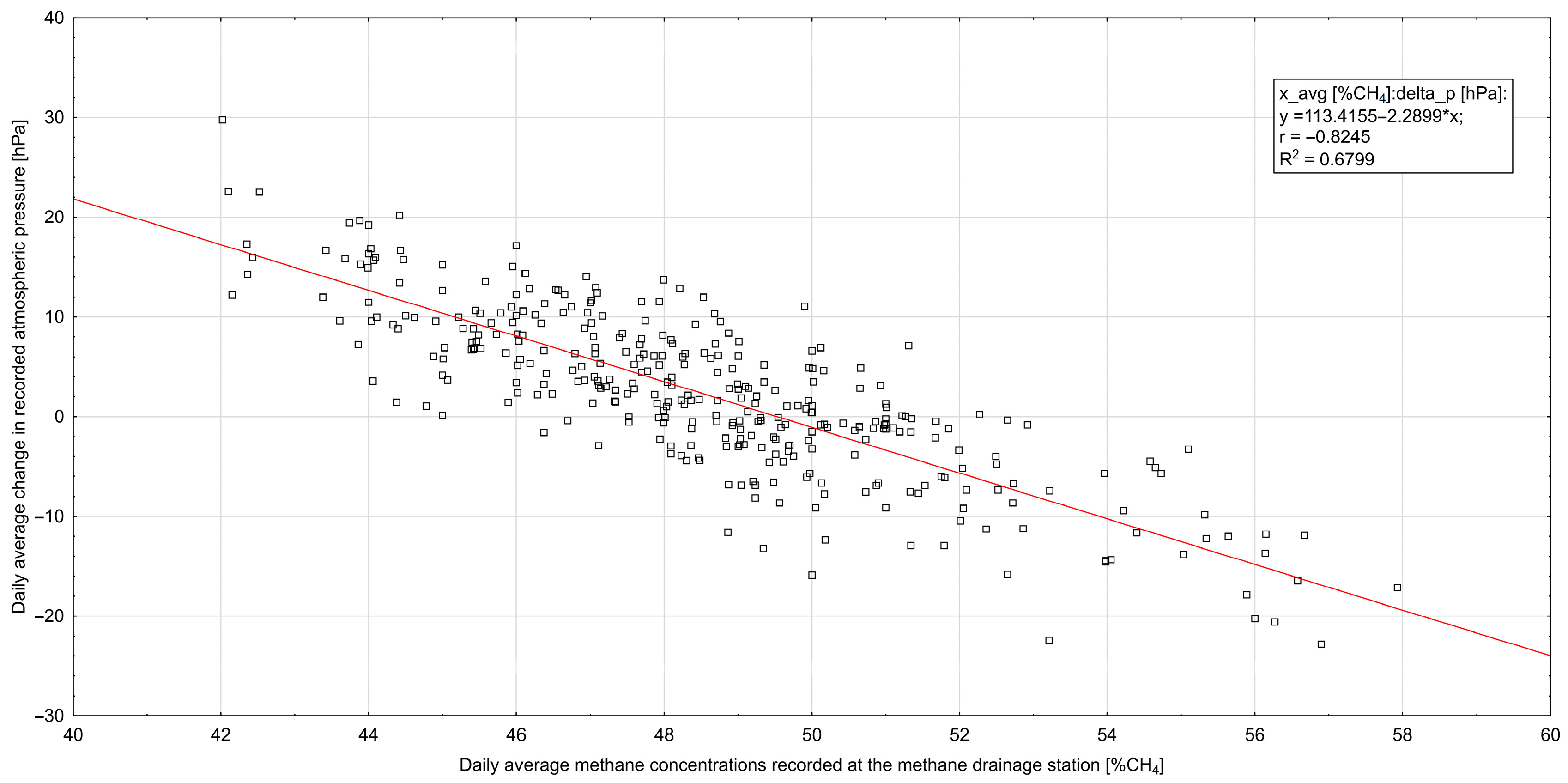

Prior to the analysis, the correlation between recorded methane concentrations in the pipeline at the degassing station and changes in recorded atmospheric pressure was examined. Due to the large size of the dataset, the correlation was assessed using daily averaged values (

Figure 3). Due to the nature of the measurement recording, a weighted average was applied. The average is determined according to the mine’s working cycle, from 06:00:00 to 05:59:59. The obtained correlation coefficient, r = 0.8245, indicates a strong relationship between the analyzed parameters. The coefficient of determination, R

2 = 0.6799, further confirms a significant fit of the data to a linear trend line and indicates that atmospheric pressure changes are one of the main factors influencing the recorded methane concentrations. The negative sign of the correlation indicates an increase in methane concentrations during barometric pressure drops, which is consistent with previous observations.

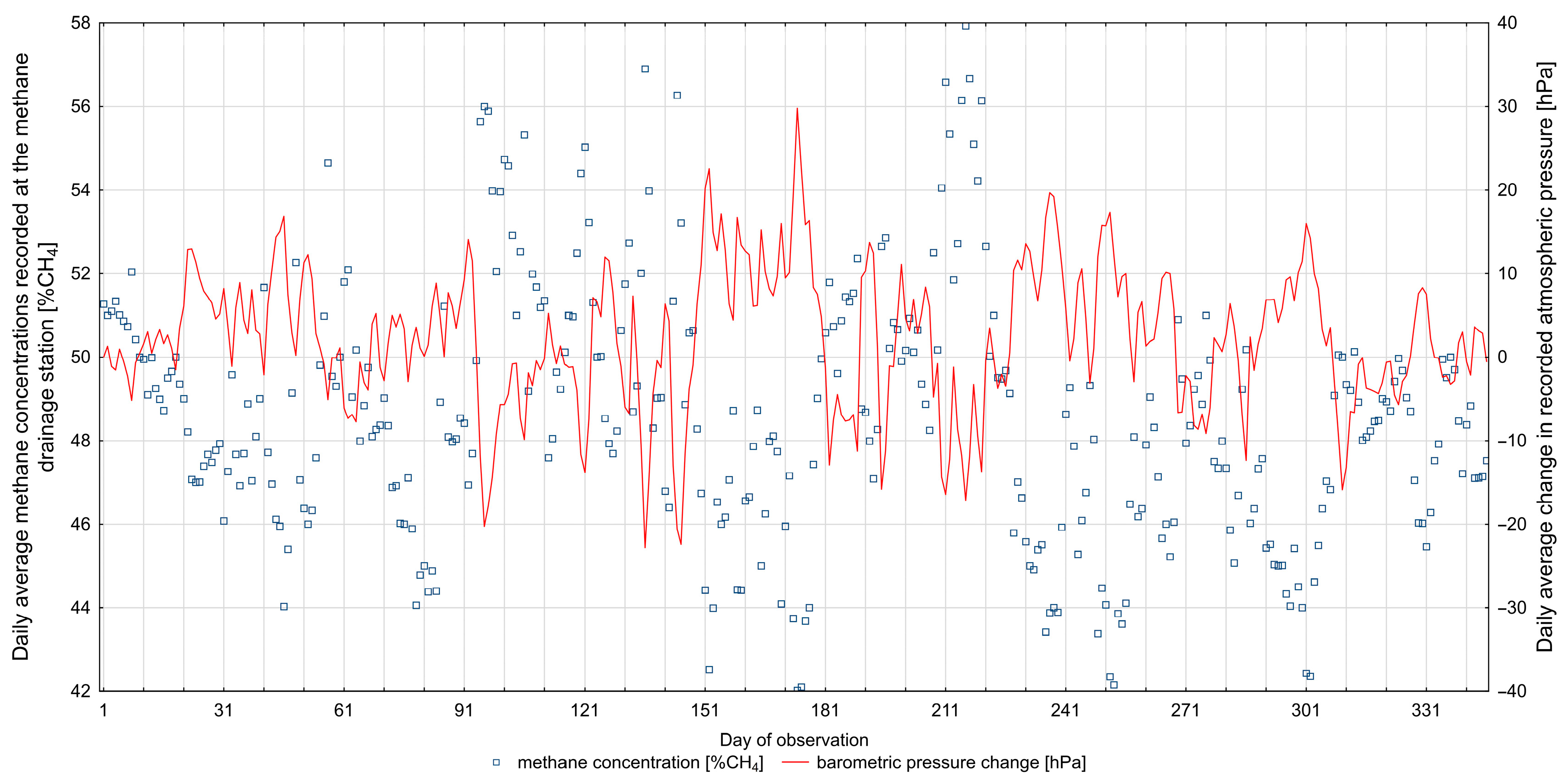

To investigate the impact of atmospheric pressure drops on methane concentrations recorded in the degassing pipeline, it was necessary to initially identify periods of barometric decline characterized by significant dynamics. To identify these events, a time series (

Figure 4) illustrating pressure changes relative to the initial value during the study period was analyzed. Due to the nature of the phenomenon, longer periods of systematic pressure decline, in which the observed trend persisted continuously, were of particular importance. To focus on such events, the authors first analyzed daily average values, which allowed for the elimination of short-term and random fluctuations. Ultimately, continuous barometric declines lasting longer than two days were identified and considered representative for further analysis of their relationship with methane emission levels.

Table 1 presents the selected periods of barometric decline analyzed, along with their key parameters, such as duration and magnitude of pressure change.

Over the course of the year-long study, particularly during the autumn, early winter, and spring periods, nine selected periods of high-dynamic barometric decline were identified and observed. All periods of barometric decline selected for analysis were characterized by an average pressure change rate exceeding 0.2 hPa per hour and a duration equal to or longer than 45 h. The recorded pressure drops during these nine events ranged from −18.6 hPa to −36.8 hPa, with durations between 45 and 112 h. The corresponding pressure gradients varied from −0.20 to −0.68 hPa/h, indicating the intensity of the barometric changes during these events. The most pronounced barometric decline was observed on 12–13 December (Period 2), with a total drop of −36.8 hPa over 65 h, yielding a gradient of −0.57 hPa/h. The longest period of continuous decline occurred on 24–29 March (Period 6), lasting 112 h, although the pressure change rate was relatively moderate (−0.20 hPa/h).

These data demonstrate that high-dynamic barometric fluctuations in the study area are not only significant in magnitude but also vary in duration and intensity. Such variations are critical for understanding their potential influence on underground methane behavior, as rapid or sustained declines can drive notable changes in gas migration and concentration patterns. The prepared printouts of continuous measurements for these periods facilitate detailed analysis of the correlation between atmospheric pressure changes and methane concentration dynamics.

For these periods, printouts of continuous measurements of methane concentrations and atmospheric pressure were prepared.

As noted earlier, measurements are conducted continuously, with a new record registered whenever a change in value occurs. This high-resolution data acquisition ensures that even subtle fluctuations in the measured parameter are captured. However, the irregular timing of consecutive records introduces challenges for quantitative analyses that require uniform temporal spacing. To address this, the intervals between consecutive measurements, recorded in the Persistence time column, were standardized using linear interpolation. Linear interpolation provides an estimation of intermediate values under the assumption of a constant rate of change between successive measurements, preserving the overall dynamics while generating a uniformly spaced time series suitable for further statistical treatment. This procedure was applied both to the recorded methane concentrations and to the pressures in order to unify the sampling time.

To determine the optimal measurement interval, five different standardization intervals: 2 s, 5 s, 10 s, 30 s, and 60 s were evaluated on two representative datasets. Empirical analysis demonstrated that a 30 s interval between consecutive recorded values provides sufficient accuracy for subsequent analyses while avoiding excessive dataset enlargement. Consequently, all further analyses were conducted using this standardized interval, ensuring both robustness and efficiency of the results.

3. Results and Discussion

Figure 5 presents the recorded methane concentrations (right axis) and the changes in atmospheric pressure relative to the initial value (left axis) during the analyzed periods of barometric decline. A clear relationship can be observed between the decrease in atmospheric pressure and the increase in methane concentration. The course of the recorded functions suggests a potential linear correlation between the analyzed parameters. In cases 2 and 5, it is evident that the slowdown of atmospheric pressure decline directly affects the rate of methane concentration increase, leading to its inhibition. In particular, cases 4 and 7 show a noticeable time lag between changes in atmospheric pressure and the subsequent increase in methane concentrations. This phenomenon is consistent with the gas release mechanism from porous media, which has been extensively described in the scientific literature. Furthermore, in all analyzed periods, the increase in methane concentration during barometric decline reaches a threshold value, after which further growth slows down or ceases, even if the pressure drop continues. This may be associated with the attainment of a dynamic equilibrium, resulting, among others, from the limited amount of methane present in the medium.

The analysis of measurement data from the decommissioned mining facility confirms the causal relationship between changes in atmospheric pressure and methane concentration. Moreover, the dynamics of this phenomenon, including time lags and the attainment of threshold values, may have significant implications for attempts to model and quantitatively predict this process.

The obtained results prompted the authors to evaluate the correlation and determination coefficients between methane concentration and changes in atmospheric pressure. As mentioned earlier, the analyzed time series suggest a linear nature of this phenomenon. At this stage of the study, potential time lags were not considered, and the data were aligned at the same time points.

The relationship between the parameter representing the decrease in recorded pressure relative to the initial value during the analyzed period and the methane concentration in the mixture recorded in the methane drainage station pipeline is presented in

Figure 6. Additionally,

Table 2 presents the parameters of the linear regression models and the values of the correlation coefficient (r) and the coefficient of determination (R

2) for the analyzed datasets.

The slope coefficients range from −0.4180 to −0.0997, with a mean of −0.3032 and a median of −0.3177. Attention should be paid to the atypical coefficient value for Case 4; excluding this dataset from the analysis significantly reduces the coefficient range from −0.4180 to −0.2442. This substantial difference may result from an incorrect determination of the start of the dynamic pressure drop period, as shown in

Figure 3, where the increase in methane concentrations occurs only after 100,000 s from the onset of the intensified pressure decline. The absolute values of the correlation coefficients range from 0.88 to 0.97, indicating a significant linear relationship in one case and a very strong linear relationship in the remaining cases between the analyzed parameters. The coefficient of determination values, which exceed 0.86 in all but one case, suggest that the pressure change parameter effectively explains the variability of recorded methane concentrations, with minimal contribution from other factors affecting changes in the degassing pipeline.

Table 2 also presents coefficients calculated as the median of all analyzed cases (MED.), the median excluding the atypical Case 4 (excl.4), and the median excluding the two extreme cases, Case 4 and Case 5 (excl.4–5). Notably, Case 9 exhibits identical values of coefficients a and b as the median of all nine cases (MED.), namely −0.3177 and 46.2051, respectively. This convergence indicates that Case 9 is particularly representative of the entire study group, serving as a form of an averaged type. It can be inferred that the measurement conditions and their dynamics in this case most closely reflect the central trend of the data.

The absolute errors of the aforementioned regression model parameters, both individually for each case and for the median of all parameters as well as the median excluding Case 4 and both Cases 4 and 5, are presented in

Table 3.

The individual model exhibits the lowest mean global error (0.6612), which is consistent with expectations. Each such model is optimally fitted to its own dataset, naturally achieving the smallest error for that specific case. In contrast, the generalized models (MED., excl.4, excl.4–5) show significantly higher mean global errors (1.8873; 1.7913; 1.9231, respectively). The analysis indicates that the data from Case 4 are sufficiently atypical that their inclusion disrupts the structure of the universal model, reducing its predictive quality. Unexpectedly, excluding Case 5—characterized by a non-linear pressure drop—further worsens the model’s performance. The results obtained do not yet allow a definitive conclusion as to whether a fully effective predictive model can be constructed based on the available data. Nevertheless, they suggest that expanding the dataset with observations from other mining facilities could substantially increase the likelihood of success.

It should also be noted that the key findings from the conducted analyses align with those presented in the study by Duda [

28]. The author indicates that, for a fixed atmospheric pressure drop in the gob, an increase in the average methane concentration leads to a linear increase in the volume of methane additionally released into the workings. Furthermore, he demonstrates that a higher gradient of pressure decline during the considered period results in a greater volume of methane released from the gob. These conclusions are consistent with our observations, confirming that the dynamics of pressure decline directly influence the rate and magnitude of methane release.