1. Introduction

The rapid progression of artificial intelligence, combined with a surge in associated investments, has triggered an extraordinary increase in data generation. This explosion in data volume places tremendous strain on current storage infrastructure, revealing the capacity, efficiency, and scalability limits of legacy storage technologies. As traditional systems struggle to keep up with the growing demand for high-density, reliable data storage, bit-patterned media recording (BPMR) [

1] emerges as a compelling next-generation solution. In BPMR, data are stored on precisely arranged, isolated nanoscale magnetic islands, which substantially reduce inter-bit interference and yield sharper, more accurate readback signals [

2]. To further enhance areal density, recent research has explored the incorporation of a second magnetic recording layer into the patterned media structure, giving rise to double-layer bit-patterned media recording (DLBPMR) [

3,

4]. While this patterned medium provides clear advantages, it may also introduce positional and dimensional inconsistencies among bit islands, potentially degrading reliability. At the same time, the regular pattern helps lower transition noise and reduce edge irregularities, resulting in improved tracking performance and greater operational stability [

5]. These developments are expected to push the limits of BPMR even further, establishing a practical route toward next-generation ultrahigh-density recording systems.

In DLBPMR systems, each recording layer preserves the fundamental structure of BPMR, which naturally leads to intricate interference behaviors. This configuration produces two-dimensional (2D) interference: intersymbol interference (ISI) in the down-track direction and inter-track interference (ITI) in the cross-track direction. Moreover, the presence of multiple stacked layers introduces an additional distortion component—inter-layer interference (ILI)—arising from signal coupling between the layers [

6]. Collectively, these interference effects make it challenging to achieve accurate signal recovery and reliable decoding performance.

To mitigate interference-related challenges in DLBPMR systems, researchers have explored both optimized structural designs and advanced signal processing techniques. Structural optimization focuses on refining the arrangement and dimensions of magnetic islands to reduce ILI and enhance readback signal energy [

7]. On the signal processing side, various equalization methods, detection algorithms, and channel coding schemes have been proposed. For example, several studies [

8,

9,

10] introduced a modified one-dimensional (1D) detection framework to address 2D interference. This sequential two-stage approach first estimates and cancels ITI from the received signal and then applies the conventional 1D Viterbi algorithm (VA) to detect the remaining signal, which is now affected solely by down-track ISI.

However, these earlier models are not specifically designed to address the additional ILI encountered in DLBPMR. To overcome this limitation, subsequent research [

11] has focused on signal processing techniques tailored to the more complex three-dimensional (3D) interference environment inherent in DLBPMR. Such approaches include equalization methods for 2D partial-response maximum likelihood (PRML) channels and the implementation of generalized partial-response (GPR) models to enhance bit-error-rate (BER) performance. Additionally, [

12] proposed a multi-dimensional signal processing framework for heated-dot magnetic recording (HDMR) systems employing BPMR, demonstrating the feasibility of sequentially detecting data sequences recorded on two tracks within each layer. Despite these advances, developing robust and efficient signal processing techniques for DLMR remains a significant challenge, particularly in accurately separating information from the upper and lower layers when their signals are combined in a single readback waveform.

In this work, we adopt the DLBPMR channel model previously introduced in [

6] as a fixed and validated transmission framework. The primary objective of this paper is not to develop a new channel model, but rather to investigate and advance MAP-based detection techniques for DLBPMR systems. By using the same channel model and evaluation metrics as in [

13], we enable a fair and direct comparison with existing detection approaches, particularly the Viterbi-based detector, while clearly isolating the algorithmic contribution of the proposed method. Building on these developments, this work proposes a novel detection scheme for DLBPMR channels, leveraging the theoretical foundations of target design, equalization, and detection from [

14,

15], as well as the channel modeling frameworks in [

16,

17,

18,

19]. The proposed approach incorporates the detection structure from [

13] and enhances it with a maximum a posteriori (MAP)-based algorithm to extract extrinsic information, which is iteratively exchanged between the upper and lower layers to improve detection accuracy. This iterative process enables significant performance gains, as demonstrated by simulation results showing that the proposed method outperforms existing models and holds strong potential for practical implementation in next-generation high-density storage systems. Finally, this paper makes the following key contributions:

- -

Novel MAP-based Detection for DLBPMR: We propose MAP algorithm for estimator and detection schemes specifically designed for double-layer bit-patterned media recording channels, addressing both intra-layer ISI and inter-layer interference (ILI).

- -

Iterative Extrinsic Information Exchange: The detection framework leverages a parallel structure between the upper and lower layers, enabling iterative exchange of extrinsic information to enhance detection accuracy and bit-error-rate (BER) performance.

- -

Extension of Generalized Partial-Response Models: By incorporating GPR modeling, the proposed approach captures the complex three-dimensional interference environment in DLBPMR systems, improving signal recovery compared to conventional 1D or 2D detection methods.

- -

Demonstrated Performance Gains: Simulation results show that the proposed MAP-based detection achieves substantial BER improvements over existing detection schemes, highlighting its potential for practical implementation in next-generation ultrahigh-density storage systems.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the structure and channel model of the DLBPMR system, along with the channel configuration.

Section 3 details the channel estimation and detection schemes developed for the optimized channel.

Section 4 presents the simulation results and analyzes the performance of the proposed approach. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines potential directions for future research.

2. DLBPMR Channel

In this paper, we adopt the DLBPMR channel model described in [

13]. In this model, the DLBPMR structure consists of two layers, where the bit islands in each layer are arranged into rectangular arrays, as illustrated in

Figure 1.

With the structure shown in

Figure 1, the bit islands in the upper layer are smaller than those in the lower layer. As reported in [

13], this size difference helps balance the energy received from each layer at the read head. The optimal bit island sizes for the upper and lower layers are 2 nm and 6 nm, respectively. In this paper, we adopt these configurations to implement the DLBPMR channel model. The continuous time readback waveform is given by the following expression:

In this formulation,

j {1,2} indicates the index of the recording layer. The magnetization

a(

,

)

1 specifies the magnetic orientation at position (

,

), where

and

denote the down-track and cross-track coordinates, respectively. Term

S represents the integration region defined by the overlap between the read head and the bit-patterned media (BPM) centered at (

x,

y). The function

h(

x,

y) corresponds to the read-head sensitivity response, in which the vertical coordinate

z is replaced by the head-media spacing (HMS), expressed as follows:

where

Hy_total and

Hy_fl are computed as follows:

where

Hy_sh1,

Hy_sh2 and

Hy are obtained from the following expressions:

where

Hy is the vertical components of each field vector and calculated in

Appendix A.

Accordingly, the continuous time readback waveform corresponding to the upper layer is given by

In the same manner, the continuous time readback waveform corresponding to the lower layer is given by

here,

w(

x,

y) is modeled as electronic noise, specifically Gaussian noise with zero mean and variance

. To obtain the discrete-time signal, oversampling is applied with a temporal resolution of

t/0.5

Tx along the down-track (

x) direction and

t/

Ty along the cross-track (

y) direction. The resulting signal

r(

x,

y) is then processed through the equalizer and detection modules, as detailed in

Section 3, to recover the original data. Finally, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is defined as follows:

here,

Pr =

E{

r(

x,

y)

2} represents the power of the signal

r(

x,

y), where

E{.} denotes the expectation operator.

4. Results and Discussions

In the simulations, we adopt the DLBPMR channel structure and parameter configuration defined in [

13], which is designed to suppress inter-layer interference through its recording and readback architecture. Under this configuration, inter-layer interference is relatively limited, allowing the proposed MAP-based detector to be evaluated without introducing additional interference-related parameters. In this section, we present the simulation setup for evaluating the proposed detection scheme in DLBPMR systems. First, we adopt the DLBPMR channel model from [

13] and implement the system shown in

Figure 2 using MATLAB R2023a. A pair of data pages with dimensions of 1200

1200 is used to represent the upper-layer (

Au) and lower-layer (

Al) data, respectively. One pair of

Au and

Al is employed to estimate the parameters of the target

G and equalizer

F. The estimated target

G is then provided to the MAP detection stage: the full target

G is used for the MIE, while only the second row of

G is supplied to the 1D MAP detector.

After obtaining equalizer F, the received signals Ru and Rl are processed by the upper-layer and lower-layer equalizers, respectively. The equalizer outputs zu and zl are then fed into the proposed MAP detection scheme to recover the original signals Au and Al. Finally, ten pairs of Au and Al are used to evaluate the BER performance of the system.

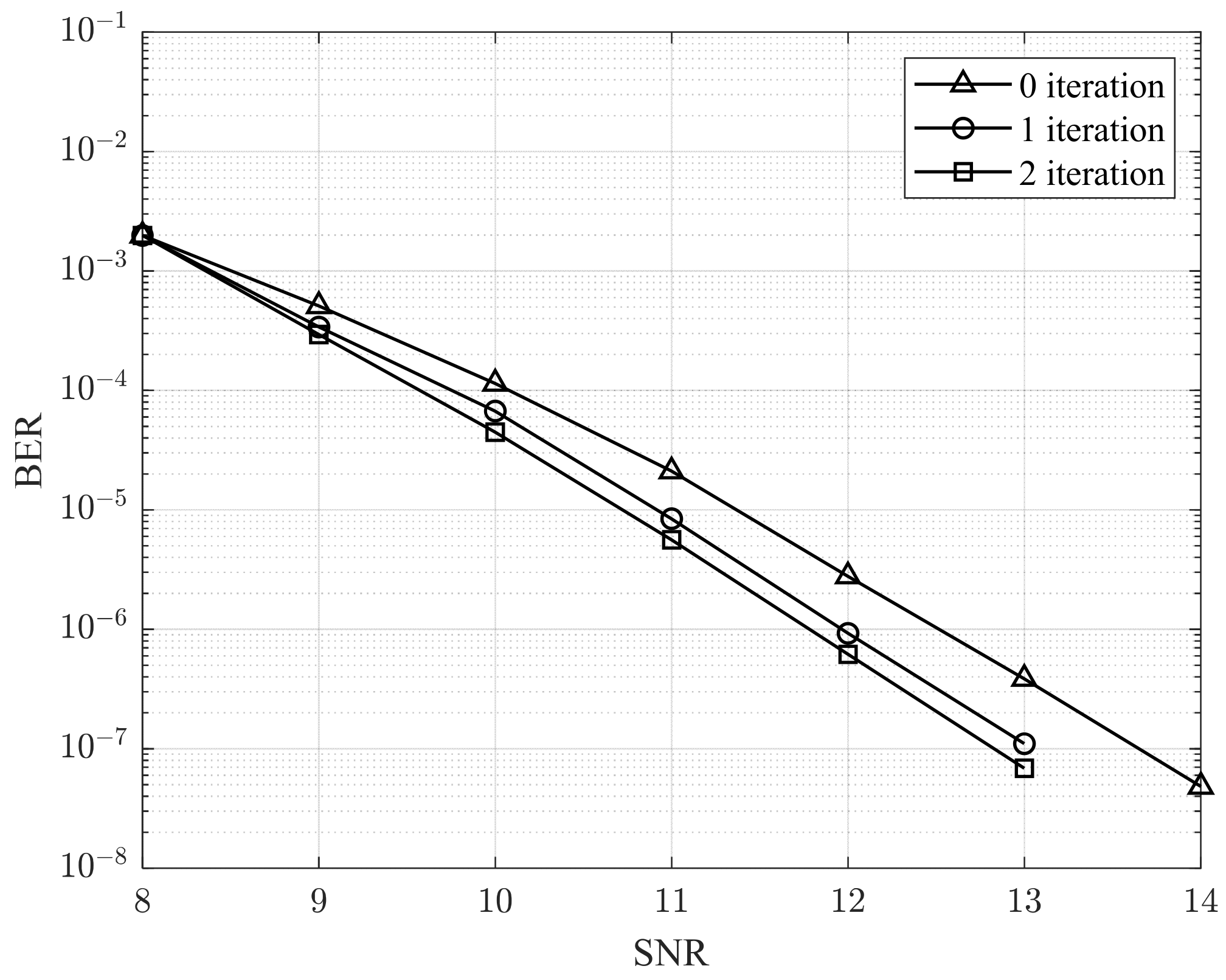

In the first experiment, we evaluate the system performance both with and without the feedback path. Specifically, we compare the BER of the proposed MAP-based detector in two scenarios: (1) when the iterative exchange of extrinsic information between the upper and lower layers is enabled, and (2) when the detector operates without any feedback. This comparison allows us to quantify the contribution of the feedback mechanism to interference mitigation and overall detection accuracy. As shown in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, the BER results for the upper, lower and both layers, respectively, demonstrate the effectiveness of the feedback-based iterative process.

From

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, it is evident that the performance of the proposed model improves as the number of iterations increases. However, beyond two iterations, the performance gain becomes negligible. This observation indicates that two iterations provide an effective balance between performance improvement and computational complexity for the proposed model. In particular, the dominant ISI and ILI components are largely captured during the first two iterations, leading to rapid convergence of the MAP-based detection process. As a result, additional iterations contribute only marginal performance gains while incurring increased computational cost, suggesting diminishing returns beyond this point. In addition, the performance asymmetry between the upper and lower layers mainly results from the inherent characteristics of the double-layer recording channel rather than from the proposed MAP detector. In the DLBPMR model, the upper layer experiences weaker ILI, while the lower layer is more strongly affected by backward coupling from the upper layer. As a result, the MAP detector achieves larger gains in the upper layer by exploiting more favorable interference conditions, without introducing algorithmic bias toward a specific layer.

Furthermore, the proposed method yields a larger performance improvement for the upper layer compared to the lower layer. This is because the upper layer is located closer to the read head and therefore delivers a stronger signal, making the interference estimation and detection process more effective. As a result, the MAP-based detector can more accurately extract and refine the signal of the upper layer, leading to a greater performance enhancement.

Finally, for both layers, the proposed model achieves an improvement of approximately 0.5 dB at a BER of 10−6 when comparing cases without feedback and with the proposed feedback mechanism. This confirms the effectiveness of the iterative feedback path in mitigating inter-layer interference and improving overall detection accuracy.

Next, we compare our proposed model with several representative methods from previous studies. The corresponding performance curves are presented in

Figure 8, allowing us to assess the relative improvements achieved by our MAP-based detection framework.

In

Figure 8, the results of the proposed model with optimized feedback, corresponding to two iterations, are presented. “SL-reg” denotes the single-layer system with a regular layout, and “SL-stag” refers to the single-layer system with a staggered layout, as described in [

20]. The model labeled “Interference Estimator using Viterbi Algorithm” represents the approach proposed in [

13].

The results demonstrate that our proposed method achieves better performance compared to previous studies. At a BER of 10−6, the proposed model obtains an improvement of approximately 1 dB relative to existing approaches. This improvement is attributed to the enhanced exchange of extrinsic information between the upper and lower layers, which strengthens the MIE process for each layer. By iteratively refining the interference estimates, the proposed model more effectively mitigates inter-layer interference, leading to improved detection accuracy across the system. Although BER improvement does not directly translate into increased areal density, it serves as an indicator of system reliability and allows a fair comparison between multilayer and single-layer recording schemes. From a system perspective, multilayer recording can distribute data across layers and potentially reduce the number of read heads required per layer, which may indirectly support higher effective storage density while maintaining reliability.

Finally, we evaluate the computational complexity of the proposed model. To estimate this complexity, we count the number of arithmetic operations required per detected bit, following a standard complexity-analysis approach used in prior DLBPMR studies. The results of this analysis, including the operation counts for the MIE, the 1D MAP detector, and the iterative feedback mechanism, are summarized in

Table 2. This comparison helps quantify the trade-off between the performance gains achieved by the proposed scheme and the additional computational cost introduced by the feedback-based detection process.

In

Table 2,

Add/Sub denote the addition and subtraction operations,

Mul/Div denote the multiplication and division operations, and

Exp/Log denote the exponential and logarithmic operations. We report on the number of operators required by the proposed MAP detection scheme. First, we consider a single branch of the proposed model, which consists of the MAP interference estimator and the 1D MAP detector. To compute the number of operators required by the MAP interference estimator per detected bit, we analyze a single state-transition process in the trellis. Since a sequence of

M symbols corresponds to

M detected bits, the number of operators involved in one state transition is equivalent to the number of operators per detected bit. Similarly, the operator count for the 1D MAP detector is obtained by considering a single-state transition process in the corresponding trellis.

In the trellis of the MAP interference estimator, there are branches. For each branch, the branch metric is computed according to (34). This computation requires two addition/subtraction operations. The term is treated as a constant, resulting in three multiplication/division operations. In addition, one exponential operation is required per branch. Therefore, over all branches, the total number of operations is addition/subtraction operations, 216 multiplication/division operations, and 72 exponential operations. Furthermore, after computing , the product is calculated on each trellis branch, which results in a total of 360 multiplication/division operations.

In the trellis of the 1D MAP detector, there are branches. Following the same procedure, the total number of operations over all branches is 16 addition/subtraction operations, 40 multiplication/division operations, and 8 exponential operations.

Based on the above analysis for one branch of the proposed detection scheme, and considering two layers, the total number of operations is

addition/subtraction operations, 800 multiplication/division operations, and 160 exponential operations. Finally, to compute the extrinsic information according to

Table 1, six additional multiplication operations are required per branch, resulting in a total of 812 multiplication/division operations.

5. Conclusions

In this paper, we proposed a MAP-based detection scheme for DLBPMR systems, featuring a novel MAP interference estimator (MIE) that enables iterative cancelation of inter-layer interference. By extending the traditional 1D MAP algorithm to address the 2D interference structure inherent in DLBPMR, the proposed model effectively enhances the reliability of multi-layer signal detection. The iterative feedback mechanism, implemented through the exchange of extrinsic information between the upper and lower layers, further improves the accuracy of interference estimation, thereby strengthening the overall detection performance. Simulation results demonstrate that the proposed scheme achieves notable performance gains compared to both the baseline system and previously published methods. Specifically, the iterative process converges quickly, with two iterations providing near-optimal performance. At a BER of 10−6, the proposed detector provides approximately a 1 dB gain over existing approaches. This improvement is attributed to the enhanced feedback path and the more accurate interference compensation achieved by the MAP-based estimator.

Finally, the proposed method exhibits a clear performance–complexity trade-off in which improved detection accuracy is obtained at the expense of increased computational complexity. Practical real-time implementation at gigabit-per-second data rates will require further hardware-oriented optimization, such as parallel and pipelined processing architectures, hardware acceleration using FPGA or ASIC platforms, and complexity reduction through approximate MAP techniques (e.g., log-MAP) to mitigate the cost of exponential operations. Moreover, the current study adopts Gaussian noise and idealized island geometry to isolate the algorithmic behavior of the proposed detector. Extending the framework to incorporate non-Gaussian noise, island inhomogeneities, and magnetic island position variability—which are critical factors in practical BPMR systems—remains an important direction for future research to enhance robustness and real-world applicability.