1. Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) are widely adopted across consumer electronics, transportation, and strategic applications due to their high energy density, long cycle life, environmental sustainability, and operational reliability. Their inherent advantages—such as the absence of moving mechanical parts—combined with continuous improvements in energy and power density, have made LIBs the preferred energy source in defense, aerospace, and automotive sectors. Moreover, the integration of battery management systems (BMS), which regulate power flow and ensure operational safety, has further enhanced the performance and reliability of modern energy storage technologies [

1]. Despite these advantages, safety remains a critical concern, particularly under abnormal operating conditions, as thermal runaway (TR) can lead to fires or explosions due to excessive internal temperature or pressure buildup [

2].

Unexpected venting, jetting, and, in severe cases, explosive failure of 18650 LIBs pose significant hazards for consumer products, electric vehicles, and large-scale energy storage systems. TR produces hot, pressurized, and often flammable gases capable of rupturing the cell casing, ejecting hot particulate and reactive chemicals, and generating damaging pressure waves or jet fires when confined or ignited. Experimental investigations have quantified vent-flow rates, jet velocities, flammability limits, and ignition behavior, revealing that venting dynamics and post-vent combustion dominate hazards to neighboring structures and adjacent cells. Quantitative experimental datasets—covering vent mass flux, jet velocity, ejected-mass temporal histories, and ignition thresholds—serve as essential benchmarks for predictive models of cell failure and hazard outcomes.

Several studies have investigated TR and explosion behavior under different conditions. Zhao et al. [

3] demonstrated that explosions occur above 50% state of charge (SOC) in enclosed chambers due to increasing concentrations of flammable gases (CH

4, CO), while ventilation reduces rupture and explosion risk, highlighting the influence of gas venting rates and external pressure on cell integrity. Mier et al. [

4] analyzed venting dynamics under thermal abuse, correlating external fluid behavior with internal pressure evolution. Using strain measurements on casings as a non-invasive pressure estimation method, they examined the effects of cell chemistry, SOC, and heating rate on venting characteristics and thermal stability.

Sun et al. [

5] studied vented gas explosions and laminar flame speeds under different safety valve pressures (1–3 MPa). Higher venting pressures (3 MPa) broadened the explosive range, increased deflagration severity, and produced peak pressure rise rates of 36.4 MPa/s, with maximum flame propagation velocity reaching 74.9 cm/s at φ = 1.1. CHEMKIN simulations highlighted radical-generating reactions facilitated by elevated H

2 and C

2H

4, emphasizing the importance of vent design in mitigating secondary hazards. Wang et al. [

6] investigated SOC, C-rate, and heating mode effects on 18650 TR, finding that pre-TR temperature was largely independent of C-rate, while TR onset temperature increased with higher C-rates. Increasing C-rate from 0.2C to 3C reduced maximum overpressure by ~0.30 MPa and the pressure rise rate by 2.49 MPa/s, indicating that SOC and C-rate exert a stronger influence on TR severity than heating power. Liu et al. [

7] examined SOC and charging–discharging effects using a controlled heating apparatus, identifying 6 W as the critical heating power at 40% SOC. TR onset temperature decreased with increasing SOC or charging current, while higher SOC caused more intense exothermic reactions and mass loss; discharging increased TR onset temperature relative to non-discharging cells.

Mechanical failure mechanisms have also been studied. Spielbauer et al. [

8] investigated 18650 cells under dynamic loads, focusing on the current interruptive device (CID). Shock tests showed minimal impact on modern cells, whereas older cells displayed mandrel displacement and increased ohmic resistance. Drop tests revealed that accelerations in practical applications could exceed standard test levels, and axial drops induced ohmic failures without thermal events. Post-mortem analyses identified CID contact loss as the predominant failure mode, though even severe mechanical damage did not compromise CID safety during overcharge tests. Li et al. [

9] studied the effect of discharge current under external heating, showing that while mass loss, onset temperatures, and peak temperatures were mostly determined by cell capacity, higher currents accelerated TR, reducing onset time by ~7.4% at 6 A. Meng et al. [

10] combined experimental and FE analyses to examine TR and gas venting in large LIB packs for underground mining, highlighting key design parameters for explosion-proof enclosures and providing insights for safer pack operation in hazardous environments. Collectively, these studies underscore the importance of experimental characterization for understanding TR initiation, venting, combustion, and mechanical failure mechanisms in LIBs.

Although experimental studies provide detailed quantitative data, they are limited by the practical infeasibility of exploring all abuse scenarios—including variations in SOC, manufacturing tolerances, confinement conditions, ignition positions, and environmental factors. Numerical investigations complement experiments by enabling controlled parametric studies and providing access to internal quantities that are difficult to measure, such as local pressure histories, transient fluid–structure interaction forces, and fragmentation dynamics. Consequently, numerical methods are indispensable for understanding the coupled thermal, chemical, and mechanical processes that govern battery failure and post-vent hazards, supporting safer cell and pack designs.

Continuum finite element (FE) models have been widely employed to simulate mechanical deformation and rupture under quasi-static and dynamic loads, while coupled thermal-chemical and lumped-parameter models have been used to predict gas generation during TR. Computational fluid dynamics (CFD) studies have provided insights into vent jet dynamics and post-vent mixing and combustion. Hybrid strategies combining FE and CFD, including RANS and LES with detailed cap geometries, have been used to estimate jet velocities and momentum, offering understanding of secondary fire hazards. However, extreme deformations, fragmentation, and strong fluid–structure interactions remain challenging for traditional FE and CFD approaches.

Recent multiphysics approaches couple gas generation source terms with FE shell failure models or use partitioned FE–CFD simulations to capture venting and post-vent combustion. While improving realism, these methods still face difficulties with mesh distortion and topological changes during rupture and fragment ejection. Many studies simplify internal contents using lumped-gas reservoirs or empirical venting laws, avoiding explicit treatment of multiphase flow and fragmenting solids. Recent works integrating experimental validation with realistic gas generation kinetics and vent-flow measurements are narrowing these gaps, yet capturing the dynamic interactions of expanding gas, vent rupture, and fragment ejection remains challenging.

Representative numerical studies include Wang et al. [

11], who simulated vent gas combustion and explosions with vent jet flames up to 0.8 m, peak temperatures of ~1800 K, and maximum flame propagation velocity of 20.4 m/s (overpressure 595 kPa). Hu et al. [

12] modeled a 150-cell LFP pack enclosure, showing that ignition location critically influences venting overpressure and hazard zones, with external pressures up to 40 kPa and hazard zones extending 6 m. Peng et al. [

13] developed a 3D combustion model for TR vented gases, demonstrating that vent panel design and stoichiometric control significantly mitigate overpressure, fireball size, and high-velocity flame zones. Wang et al. [

14] constructed an FE model of an 18650 cell under internal short-circuit conditions, incorporating all key components and accounting for temperature, strain rate, and anisotropy, providing insights difficult to obtain experimentally.

Despite the advances of FE and CFD methods, fully capturing violent venting and explosions with large-scale fragmentation and high-speed jets remains challenging. Smoothed-particle hydrodynamics (SPH) offers a promising alternative due to its meshless, Lagrangian nature, accommodating large free-surface motions, evolving discontinuities, and high-speed advection without remeshing [

15]. SPH can model compressible gas dynamics, shocks, and jet expansion in a unified particle framework, and can be coupled with FE solids (FE–SPH) [

16] to simulate momentum transfer from rapidly expanding gas to a ductile, fracturing can. For 18650 explosions, this enables explicit representation of internal pressurization, rupture, jet formation, and fragment ejection, which are difficult to capture using traditional FE or CFD.

SPH applications to LIBs remain limited, with most studies addressing mechanical impacts or ballistic fragmentation rather than TR-driven venting. Recent FE–SPH studies successfully reproduced damage morphologies and fragment distributions under high-velocity impact, but no work has explicitly modeled internal gas pressurization, vent rupture, and subsequent explosion or jet dynamics in 18650 cells. Addressing this gap, the present work develops a dedicated SPH and FE–SPH modeling framework. A compressible-gas SPH model of internal pressurization and venting is constructed and validated against experimental vent flow and rupture pressure data, while coupled FE–SPH simulations illustrate the interaction of expanding gas with a ductile steel can undergoing progressive damage and fragmentation. By integrating validated gas generation and pressure histories with meshless fluid dynamics and established damage models, this study delivers the first end-to-end SPH simulation of an 18650 explosion, providing novel insights into jet formation, fragment kinematics, and pressure pulse evolution, informing the design of safer cells and battery packs.

2. Simulation Procedure

The present study employs a coupled FEM–SPH strategy. The FE formulation is retained in regions where deformation remains moderate, while SPH particles are assigned to zones expected to undergo rupture, fragmentation, or violent gas expansion. This hybrid approach captures the essential physics of the explosion without excessive computational expense, while eliminating mesh distortion [

17] and maintaining accurate gas–structure interaction during venting and failure.

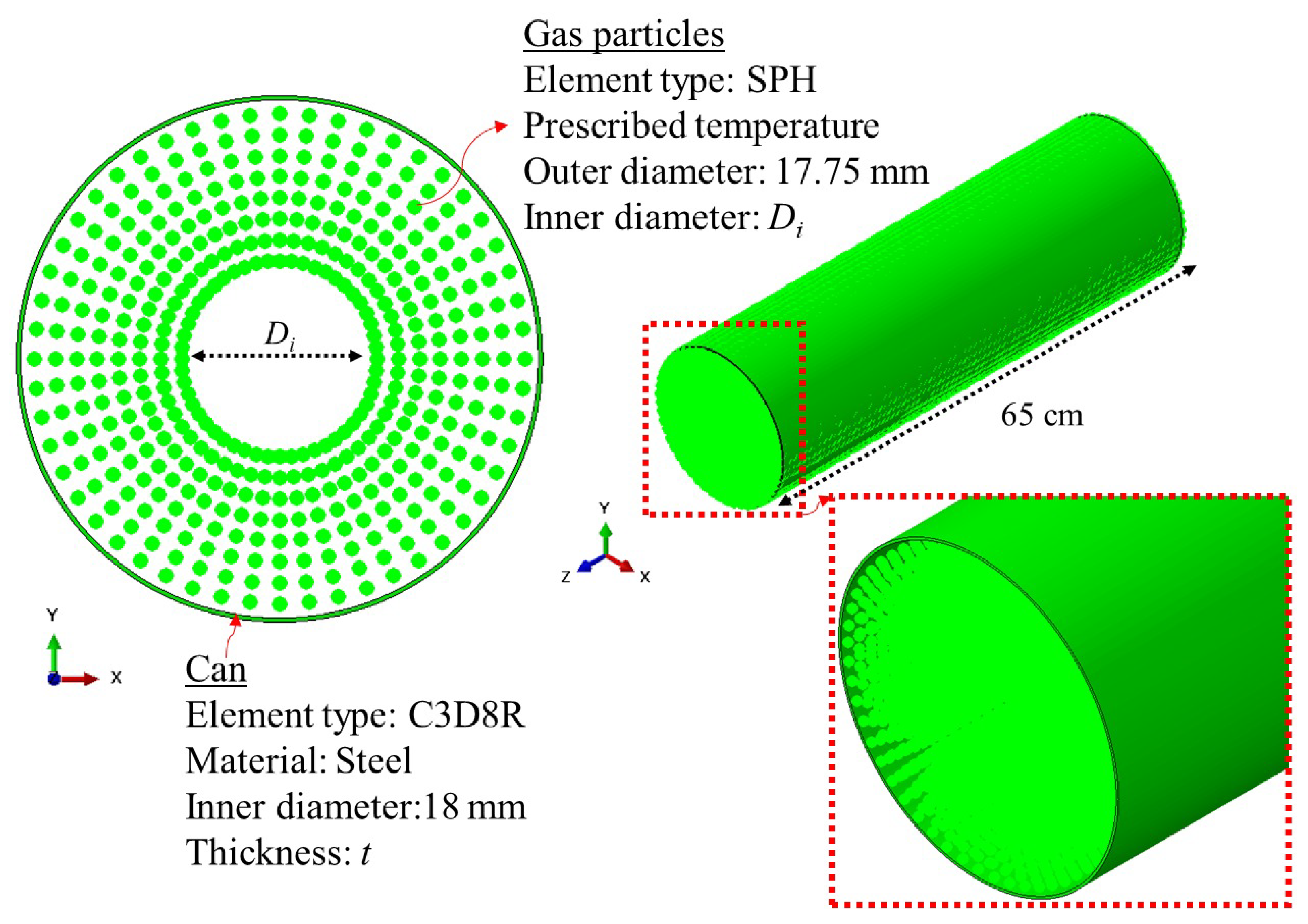

Figure 1 illustrates the numerical configuration adopted for the SPH model developed to simulate the explosion behavior of a cylindrical 18650 battery cell. The metallic can was modeled using finite element (FE) solid elements of type C3D8R, representing a deformable steel enclosure with an inner diameter of 18 mm and variable wall thickness

t. The can geometry was defined as a cylindrical shell 65 mm in length, consistent with standard 18650 dimensions. The internal gas domain was discretized using SPH particles, representing the high-pressure gaseous products generated during thermal runaway. The gas particles were prescribed with an initial temperature and thermodynamic properties corresponding to the conditions immediately prior to rupture. A particle spacing of 0.75 mm resulted in 28,188 SPH elements (PC3D type), while the metallic can was modeled with 14,400 hexahedral elements (C3D8R) of 0.5 mm size. The details of the convergence study for the SPH particle spacing are provided in

Section 3.

In the present SPH–FE simulations, the average spacing between neighboring SPH particles was 0.75 mm, and the corresponding characteristic length was defined based on this spacing. To ensure numerical stability and an accurate representation of pressure gradients, it is generally recommended that each SPH particle interacts with approximately 50–150 neighboring particles. This can be achieved when the smoothing length h is about 1.2–1.5 times the particle spacing. In Abaqus/Explicit, the characteristic length determines the kernel (smoothing) radius, which in turn governs the number of neighboring particles contributing to the interpolation of field variables such as pressure and density. To maintain stability and capture smooth pressure gradients without excessive diffusion, the smoothing length h was set within this range. In this study, a smoothing length factor of 1.4 was adopted, resulting in an effective smoothing radius of approximately 1.05 mm. This configuration allows each SPH particle to interact with a sufficient number of neighbors (typically 50–150), ensuring stable force transmission and accurate pressure-wave propagation while avoiding artificial oscillations or particle disorder near the gas–can interface.

In SPH, the number of neighboring particles interacting with each particle significantly affects numerical stability, pressure smoothness, and energy conservation. This number depends on the ratio

f =

h/Δ

p, where Δ

p is the particle spacing. In most SPH implementations, including Abaqus/Explicit, the kernel function has a compact support extending to approximately 2

h, meaning that each particle interacts with all others within a spherical region of radius 2

h. The approximate number of neighbors can be estimated as follows:

For the present model, Δ

p = 0.75 mm and

f = 1.4, giving an effective smoothing radius of 2

h = 2.1 mm and approximately 92 neighbors—an excellent compromise between stability and computational cost.

Table 1 summarizes the estimated number of neighbors for different

f values under the 2

h support assumption. When

f < 1.2, the number of neighbors falls below ~50, causing insufficient kernel overlap, pressure noise, tensile instability, and irregular particle motion—particularly in regions with steep gradients such as the gas–can interface. Conversely, for

f > 1.5, the number of neighbors exceeds ~120, leading to over-smoothing of pressure gradients, loss of spatial resolution, and higher computational cost due to the larger number of particle interactions. Thus, maintaining

f between 1.2 and 1.5 provides an optimal balance between stability, accuracy, and efficiency in coupled SPH–FE explosion modeling.

A surface-to-node contact formulation was used to define the interaction between the SPH gas particles and the inner surface of the FE can, ensuring accurate transmission of pressure and momentum across the gas–structure interface. This coupling allowed the expansion of the pressurized gas to induce realistic deformation and potential failure in the metallic can during the explosion process. The outer and inner diameters of the gas domain were defined as 17.75 mm and Di, respectively, ensuring full confinement and uniform distribution of internal pressure. This modeling configuration provided a robust computational framework for capturing the coupled thermomechanical response of the can and internal gas during the early stages of explosion initiation.

Just prior to rupture, the gases generated inside the 18650 cell are expected to compress and migrate toward the outer regions of the jelly-roll due to pressure gradients. This non-uniform distribution arises because the densely wound jelly-roll structure restricts gas flow near the core while providing less confinement near the can wall. Consequently, just before the explosion, the gaseous phase becomes concentrated in the outer regions, exerting the highest pressure on the inner surface of the metal can. To capture this behavior, the gas domain in the present SPH model was represented as a hollow cylindrical region, with its outer boundary coinciding with the can’s inner wall and the inner radius adjusted to reflect outward gas accumulation. This configuration ensures a realistic representation of fluid–structure interaction during the battery explosion.

The gas phase was modeled using the ideal gas equation of state (EOS), which adequately represents the behavior of high-temperature, low-density gases generated during venting and explosion. The EOS relates the gas pressure

p to density

ρ and specific internal energy

e as follows:

where

γ is the specific heat ratio. For air,

γ = 1.4 and

R = 287 J/(kg·K) were adopted [

18]. This formulation couples thermal and mechanical responses, allowing pressure to evolve naturally from temperature and density variations within the SPH domain. Although more complex EOS formulations (e.g., Mie–Grüneisen) can capture non-ideal effects at very high pressures, the ideal gas law was sufficient here due to the relatively short duration of the event and the moderate pressure range. Its simplicity also enhances numerical robustness and facilitates stable coupling between the SPH gas and the Lagrangian FE can during the highly transient explosion process.

Two initial gas conditions were considered to represent the pre-rupture state inside the 18650 cell. In the first configuration, the gas was initialized at 600 K—based on reported vent onset temperatures (~170 °C) [

9] and typical thermal runaway ranges (500–800 °C) [

19] and a pressure of 3.5 MPa [

4]. The corresponding density, calculated using the ideal gas law, was approximately 20.3 g/L (2.03 × 10

−11 tonne/mm

3). In the second configuration, a radially varying velocity field was prescribed, increasing linearly from the inner to the outer radius, to mimic the dynamic expansion tendency of compressed gas during thermal runaway. Comparing these two initializations allows for the assessment of how thermal versus thermokinetic initialization influences the resulting pressure evolution, can deformation, and rupture behavior.

Boundary and numerical conditions were applied to ensure physical consistency and stability of the coupled SPH–FE simulation. The cylindrical metal can was modeled with one end fully fixed to represent the welded cap region, while the opposite end and lateral wall were left free to deform under internal pressure. A general contact algorithm defined the interaction between SPH gas particles and the can’s inner surface, enabling the transfer of both normal and tangential forces and preventing interpenetration. The SPH particle characteristic length was chosen to ensure six to eight particles across the gas annulus, providing sufficient resolution of pressure gradients. Artificial viscosity, following the standard Monaghan formulation, was introduced to stabilize shock propagation and suppress unphysical particle clustering. The explicit solver’s time increment was automatically determined using the Courant–Friedrichs–Lewy (CFL) stability criterion [

18], ensuring accurate wave transmission across the SPH–FE interface. These configurations collectively guarantee stable fluid–structure coupling, accurate pressure prediction, and reliable representation of the transient deformation and rupture behavior of the can during the explosion event.

The elastic and plastic properties of the steel can and external cover made of AL6061 are shown in

Table 2. The Johnson–Cook (JC) material model was used to simulate the material behavior under high strain-rate conditions during the explosion process. This material law is commonly adopted for the dynamic problems characterized by high strains (

) and strain rates (

). More details about JC model can be found elsewhere [

14,

18]. Following the approach used in Refs. [

9,

14,

16,

17], a strain-based failure criterion was adopted in the present study, wherein elements were removed once their corresponding failure strain threshold was reached.

The fundamental concepts of the SPH theory are briefly outlined below. In this approach, the conservation equations of continuum fluid dynamics are converted into their integral forms through the use of an interpolation function. The kernel approximation of a function is evaluated over the computational domain, where its value at a specific position is determined using smoothing kernels

W as follows:

Here,

represents the material positions within the compactly supported domain, while

h denotes the smoothing length, which varies both spatially and temporally. In defining

W, the cubic-spline kernel approximation is most commonly employed and it must satisfy the following conditions:

Here, the Dirac delta function is recovered as the smoothing length approaches zero. The variable k denotes a constant representing the relative distance between the points and .

In the SPH method, the solution domain is typically discretized into uniformly distributed particles that carry the field variables. These particles are influenced by the pressure gradient and viscous stresses within the flow field. The discrete representation of a field variable at a given particle can be expressed as follows:

Here, the subscript i refers to the particle of interest, while j denotes the particles located within the support domain of particle i. N represents the number of neighboring particles, and and are the mass and density of each neighboring particle, respectively. The number of adjacent particles is determined according to the smoothing length.

3. Results and Discussion

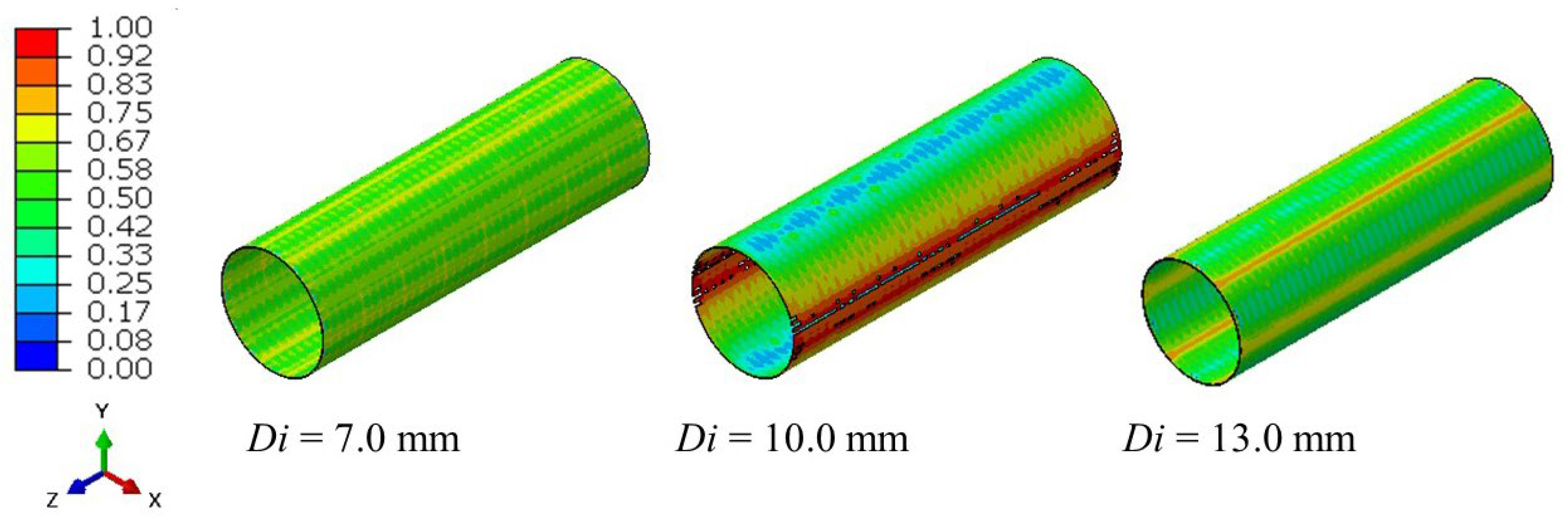

A parametric study was performed to investigate the influence of the hollow SPH gas domain’s inner radius on the deformation and failure behavior of the 18650 battery can. Owing to the absence of experimentally reported measurements of the instantaneous inner gas radius during cylindrical cell explosions, a range of representative inner radii was selected to enable a qualitative, yet physically informed, assessment of the gas–structure interaction. Three inner diameters—7.0 mm, 10.0 mm, and 13.0 mm—were examined, while all other parameters, including gas pressure, temperature, and density, were held constant. As illustrated in

Figure 2, the extent and pattern of deformation on the can surface were found to depend strongly on the assumed inner radius of the gas region. The simulation corresponding to an inner diameter of 10.0 mm resulted in localized thinning and rupture, indicating that the critical strain threshold was exceeded under this configuration. For the other two cases (7.0 mm and 13.0 mm), the fracture strain was not reached, although both exhibited measurable plastic deformation. Between these, the 13.0 mm configuration produced more pronounced deformation than the 7.0 mm case, confirming that the internal gas geometry plays a key role in determining the overall mechanical response of the can.

A deeper analysis of the gas–structure interaction provides a physical explanation for these observations. When the inner radius increases from 7.0 mm to 10.0 mm, the annular gas layer becomes thinner and the gas volume slightly decreases; however, the energy release becomes more spatially focused toward the outer wall. The confined gas expansion, acting over a shorter radial distance, enhances the synchronization of the pressure wave and concentrates the impulse on the can surface—producing the most severe deformation and eventual rupture for the 10.0 mm configuration. When the inner radius is further enlarged to 13.0 mm, the total gas mass and stored energy decrease more significantly, resulting in a less intense impact and reduced deformation severity. Conversely, a smaller inner radius (7.0 mm) allows for a thicker gas domain that dissipates the expansion energy over a larger distance, lowering the localized wall pressure. Overall, these results highlight a geometric focusing effect in which the spatial distribution of the gas governs the dynamic pressure transfer and failure initiation. This influence of the internal gas domain geometry on can rupture has not been explicitly reported in previous finite element–based simulations of 18650 battery explosions and underscores the importance of accurately representing gas confinement in SPH-based models. In the next simulations, Di = 10.0 mm was considered.

The deformation patterns predicted on the outer surface of the can exhibit strong qualitative similarity to the experimentally and numerically observed failure modes reported in Ref. [

14]. In particular, the outward bulging and localized expansion regions obtained in our analysis closely mirror the deformation profiles documented in that study. This correspondence offers indirect yet meaningful validation of the physical realism of the gas–structure interaction captured by the present model.

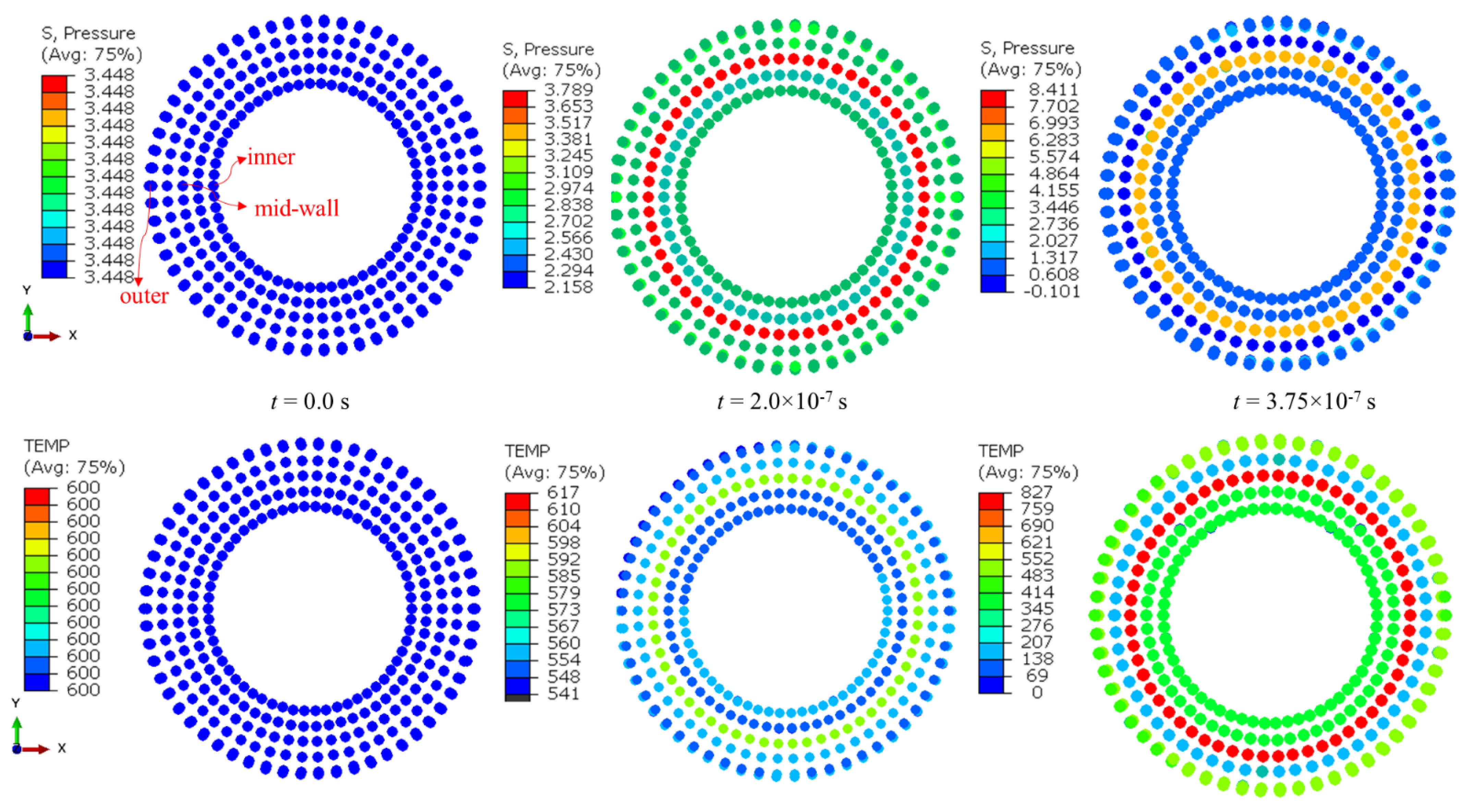

To better understand the thermodynamic and mechanical behavior of the confined gas during the bursting event, the pressure and temperature evolution were analyzed both spatially and temporally within the SPH gas domain.

Figure 3 illustrates the pressure and temperature distributions at three representative instants—0.0 s, 2.0 × 10

−7 s, and 3.75 × 10

−7 s. Initially, the gas inside the battery exhibits a uniform pressure of approximately 3.45 MPa and a homogeneous temperature of 600 K, corresponding to the pre-burst equilibrium condition. As expansion begins, radial gradients in both fields emerge due to the outward acceleration of the compressed gas.

At t = 2.0 × 10−7 s, the pressure near the inner radius begins to decrease, while elevated pressure zones develop around the mid-wall region. This occurs because the gas layer located midway between the inner gas core and the resisting can wall becomes momentarily trapped between two opposing effects: the rapid rarefaction near the inner radius and the growing resistance imposed by the outer boundary. As a result, this mid-wall region experiences a temporary compression, leading to a localized rise in pressure. By t = 3.75 × 10−7 s, these pressure non-uniformities become more pronounced, with the mid-wall region maintaining the highest pressure while both the inner and outer radii continue to unload. The outer-radius pressure drop reflects the beginning of can deformation and outward displacement, which reduces confinement and causes local pressure decay rather than the previously assumed pressure buildup near the boundary.

The corresponding temperature fields (bottom row in

Figure 3) follow the same general trend. The initially uniform temperature distribution gradually transitions to a non-uniform profile as the gas expands. The temperature decreases rapidly near the inner radius, where adiabatic expansion dominates. A notable temperature rise occurs at the mid-wall region, consistent with the localized compression and delayed expansion observed in the pressure field. In contrast, the temperature at the outer radius gradually decreases, indicating that gas adjacent to the can wall undergoes decompression as the wall begins to accelerate outward, reducing local confinement. At later times, continued decompression promotes cooling across most of the domain.

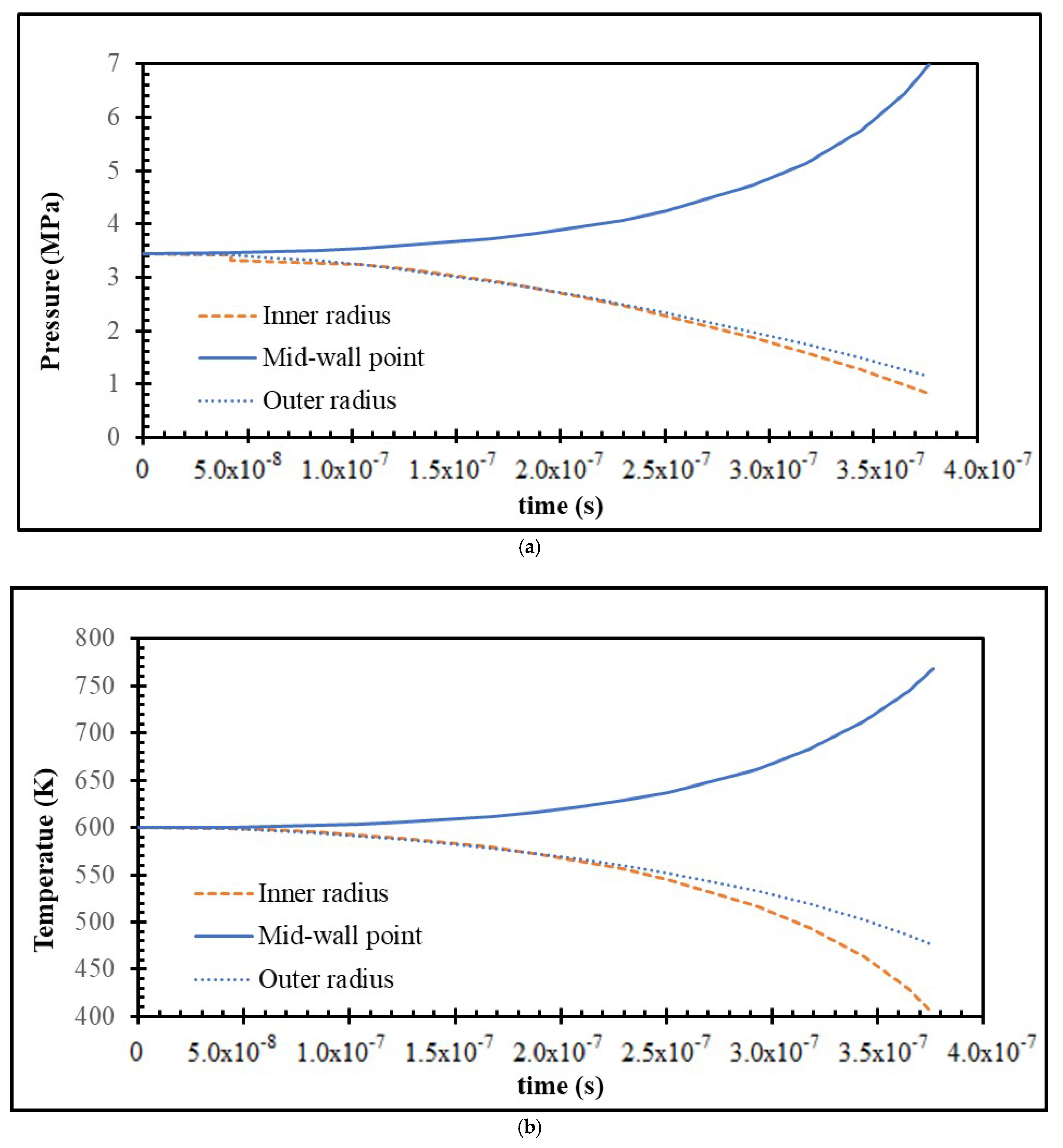

Figure 4 provides further insight into the temporal evolution of pressure and temperature at three characteristic radial positions—inner radius, mid-wall point, and outer radius. The pressure–time history shows an initially uniform distribution that diverges as the burst progresses. The mid-wall point exhibits a steadily increasing pressure, confirming that inertial effects and wave reflections sustain a localized buildup. Conversely, both the inner and outer radii experience a monotonic pressure reduction, which aligns with the early rarefaction near the inner cavity and the outward-moving boundary at the can wall.

A similar trend is observed in the temperature–time histories. The temperature at the mid-wall rises continuously due to compression and reduced volumetric expansion in this region. Meanwhile, the temperatures at both the inner and outer radii drop sharply, demonstrating dominant adiabatic cooling as these regions expand more rapidly. The coupling of these processes highlights that, during the early stages of the explosion, the gas energy is redistributed asymmetrically, concentrating thermal and mechanical energy within the mid-wall region rather than at the boundaries.

Overall, the results reveal an intricate interaction between gas thermodynamics and the structural response of the can. The mid-wall region acts as a transient reservoir of concentrated energy, which governs the timing and magnitude of the impulse transmitted to the outer wall. Understanding this localization mechanism is essential for accurately predicting can deformation and the subsequent initiation and propagation of rupture.

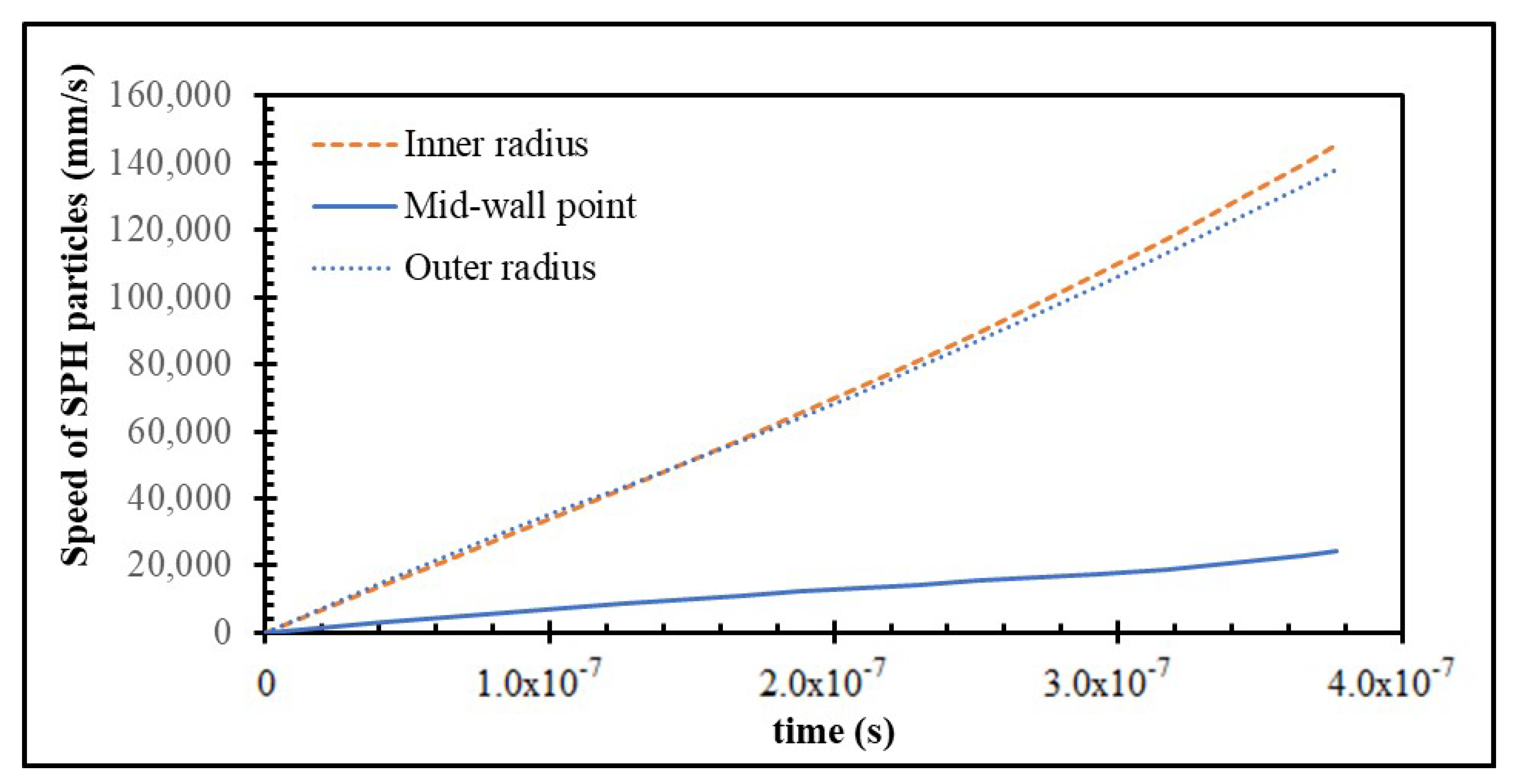

Figure 5 illustrates the temporal evolution of the SPH particle velocities at the inner radius, mid-wall point, and outer radius of the confined gas domain. The particles located at the inner radius attain the highest velocities throughout the simulated time window, increasing almost linearly as the gas begins to expand. This behavior is expected, because these particles are directly exposed to the strongest initial pressure gradient generated by the rapid gas pressurization near the core region. Particles near the outer radius also experience substantial acceleration, although with a slightly lower slope compared with the inner radius, indicating that part of the energy of the outward-moving pressure wave is consumed in accelerating the intervening gas and is attenuated by geometric spreading. In contrast, the mid-wall particles exhibit significantly lower velocities. This reduced acceleration arises from the competing pressure forces acting on both sides of the mid-wall region and from the temporary compressive loading identified earlier in the pressure and temperature distributions. Although this region exhibits elevated pressure and temperature due to transient compression, these conditions do not translate into large translational momentum. The combined behavior confirms that particle acceleration is strongest at the boundaries of the gas domain, where unidirectional pressure gradients dominate, whereas the mid-wall region primarily stores and redistributes energy through compression rather than bulk motion. This pattern is fully consistent with the physical gas dynamic mechanisms governing confined expansion and with the previously observed radial variations in pressure and temperature.

Although the present study employs a thermally driven initialization through elevated internal temperature and the equation of state (EOS) of the confined gas, it is worth noting that the explosion of a cylindrical 18650-type battery can alternatively be represented through a kinematic approach, where each SPH particle is assigned an initial velocity rather than an initial temperature rise. In this framework, the rapid gas expansion is modeled explicitly as a momentum-driven process, and the velocity field prescribes the initial impulse that triggers the can deformation. Such a formulation is particularly useful for cases where the pressure–temperature equilibrium prior to rupture is not precisely known, but the magnitude and distribution of gas momentum are measurable or can be inferred from experimental venting data.

A physically meaningful radial velocity field should capture the fact that gas acceleration is strongest at the boundaries of the confined domain—namely, near the inner and outer radii—while being minimal at the mid-wall region where compressive interactions dominate. This behavior was also evident in the present thermal simulations, which showed that SPH particles at both boundaries attained the highest velocities, whereas those near the mid-wall experienced lower translational motion despite higher local pressure and temperature. To reproduce such dynamics, a boundary-peaked velocity profile can be defined as

where

denotes the mid-wall radius, and

is the maximum particle speed at the inner and outer boundaries. Depending on the desired directionality of motion, the sign of

may be assigned such that both boundaries accelerate outward, or alternatively, the inner and outer surfaces move in opposite directions according to

The latter option represents symmetric expansion waves moving away from the mid-plane, consistent with the reflection-dominated behavior of confined gases.

When using this kinematic initialization, it is crucial to ensure thermodynamic consistency. Imposing nonzero initial velocities injects additional kinetic energy into the system, which must be balanced against the internal energy derived from the EOS to avoid artificially overestimating the total energy release.

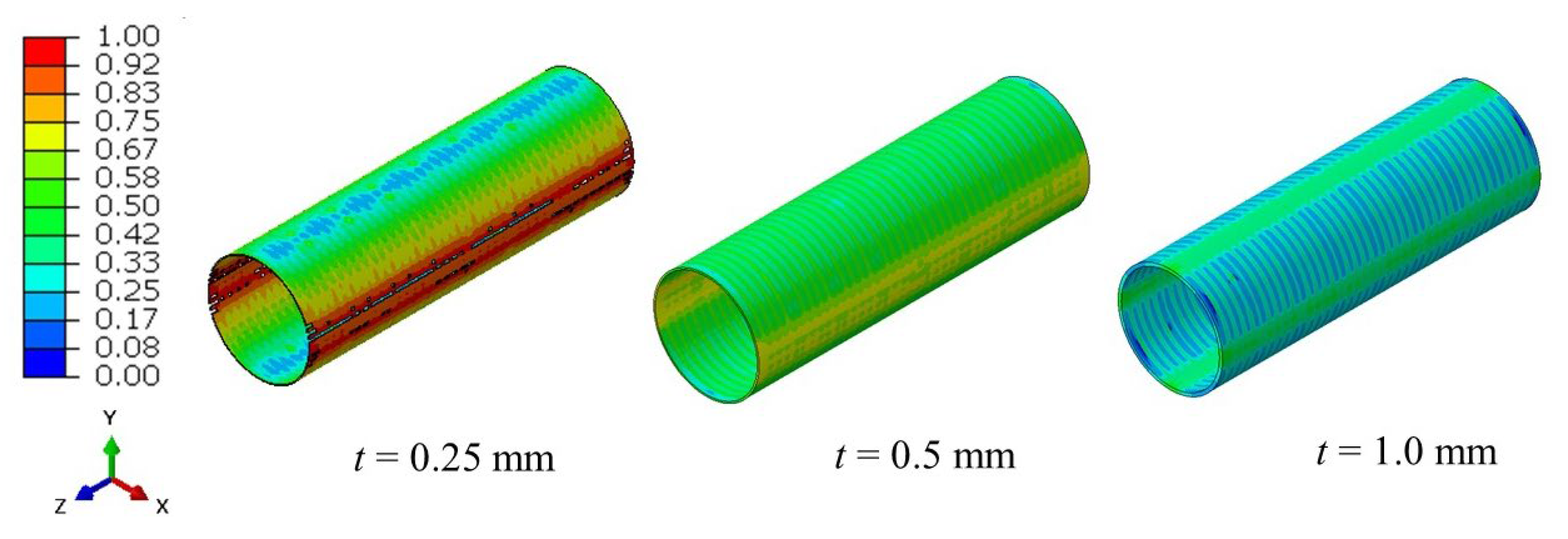

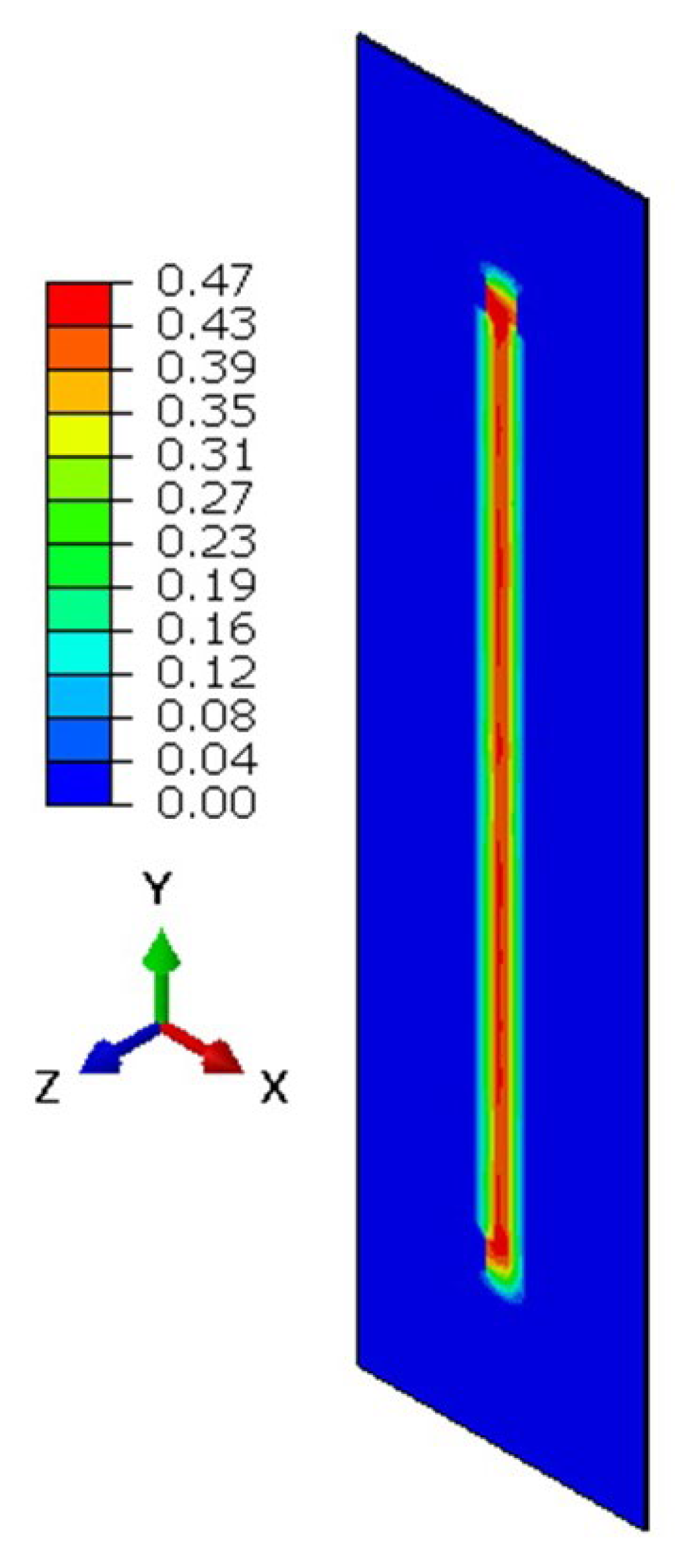

Figure 6 illustrates the distribution of plastic strain (normalized with failure strain, 1.0 indicates the failure strain is reached) in the outer can of the battery at an internal pressure of 6.896 MPa and a temperature of 600 K for three different wall thicknesses (

t = 0.25 mm [

14], 0.5 mm, and 1.0 mm). The results correspond to the conditions immediately preceding the onset of explosion, as obtained from SPH simulations. For the thinnest case (

t = 0.25 mm), localized regions of high plastic strain (normalized with fracture strain) approaching unity are observed, particularly along the circumferential direction, indicating imminent material failure. This suggests that the can is unable to withstand the combined thermal and mechanical loading, leading to rupture initiation. As the thickness increases to 0.5 mm, the overall plastic strain decreases significantly, and the strain distribution becomes more uniform, implying enhanced structural integrity and reduced likelihood of failure. For the thickest configuration (

t = 1.0 mm), the strain remains well below the critical failure limit throughout the can surface, demonstrating that increasing wall thickness substantially improves resistance to deformation and prevents fracture under the same loading conditions. These results highlight the critical influence of can thickness on the explosion resistance of cylindrical battery enclosures, with thicker walls effectively mitigating failure risk under high-pressure, high-temperature scenarios.

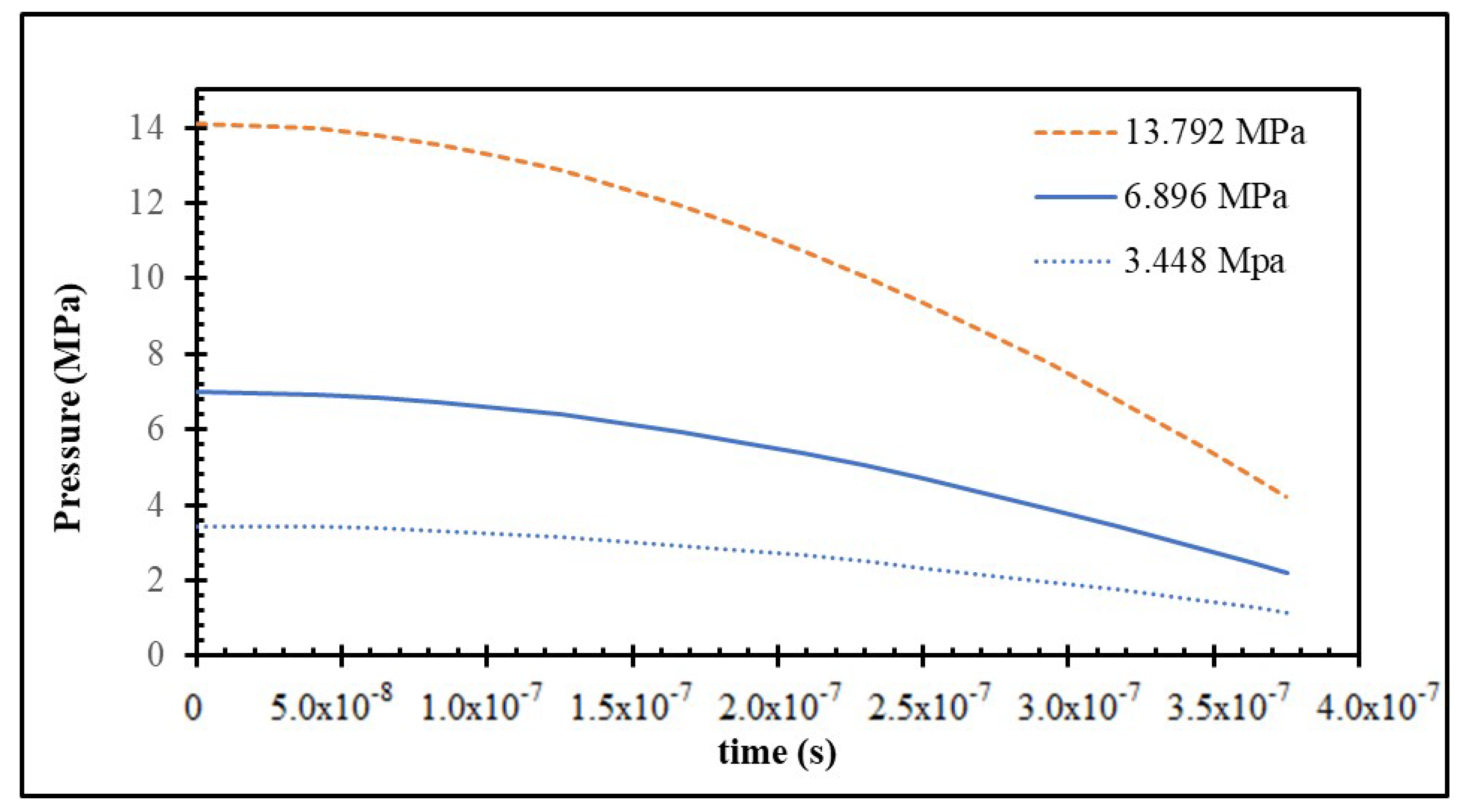

Figure 7 and

Table 3 together summarize the effect of initial internal gas pressure on the final residual pressure distribution at the inner radius, mid-wall region, and outer radius of the gas domain. For initial pressures of 3.448, 6.896, and 13.792 MPa, the corresponding residual pressures at the outer surface were 1.142, 2.192, and 4.233 MPa, respectively, demonstrating a nearly proportional relationship between the initial energy stored in the confined gas and the remaining load transmitted to the can wall after the initial expansion phase. A similar scaling behavior is observed at the inner radius (0.826, 1.672, and 3.311 MPa), reflecting the rapid decompression occurring close to the gas core. In contrast, the mid-wall region retains substantially higher residual pressures (6.978, 14.373, and 29.875 MPa). This behavior is consistent with the earlier pressure–temperature analyses, where the mid-wall region acted as a transient compression zone due to wave reflections and the opposing pressure gradients between the expanding inner gas and the resisting outer can. As a result, the mid-wall location becomes the primary reservoir of trapped or delayed gas energy during the decompression phase.

The most critical quantity from a structural safety standpoint is the residual pressure acting on the outer radius, because this load interacts directly with the battery can at a stage when it is already plastically deformed, thinned, or partially cracked. Even after substantial unloading, the residual pressures of 1.142–4.233 MPa acting on the outer boundary remain large enough to drive continued outward deformation or secondary rupture. The scaling trend underscores that higher initial internal pressure not only increases the peak transient load but also significantly elevates the sustained pressure that persists during the late-time expansion. This behavior has practical implications for protective design: any external reinforcement—such as an additional steel sleeve, composite overwrap, or energy-absorbing containment layer—must be engineered to accommodate both the peak shock load and the substantial residual pressure that follows. The presented results therefore emphasize that the residual pressure magnitudes, especially those at the outer surface, play a decisive role in determining the required strength and effectiveness of supplemental outer coverage intended to mitigate battery explosion hazards.

A convergence study was conducted to evaluate the influence of SPH particle spacing on the predicted residual pressure distribution at both the inner and outer radii (see

Table 4). When the spacing was reduced from 0.75 mm to 0.375 mm, the change in residual pressure was less than 5% for both positions, indicating that further refinement had a minimal effect on the results. In contrast, the difference between the 1.5 mm and 0.75 mm particle spacing exceeded 15%, demonstrating that the coarser resolution was insufficient to capture the pressure response accurately. Based on these observations, the 0.75 mm spacing was considered adequately converged and was adopted in the numerical simulations.

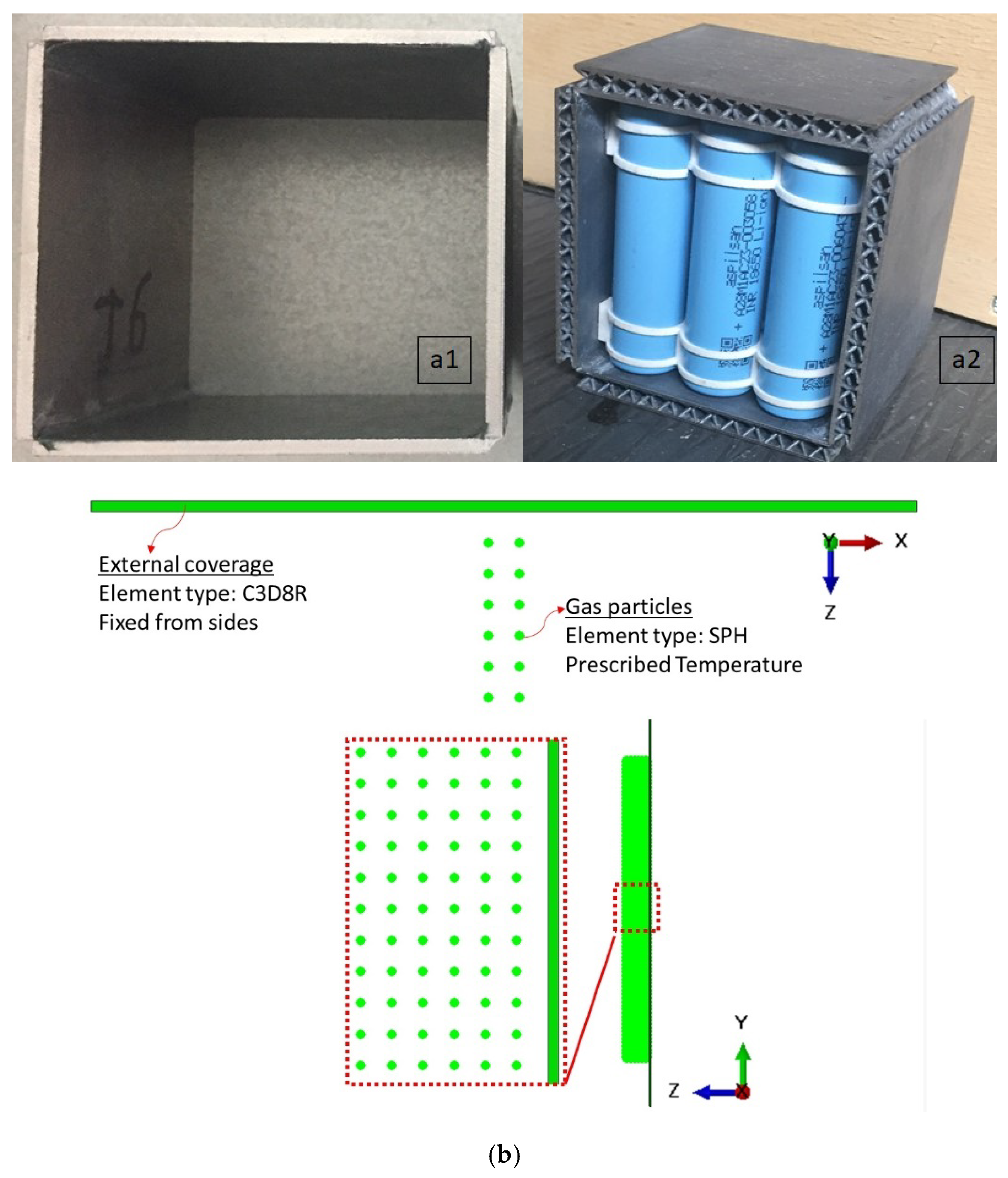

In battery packs, particularly those comprising multiple 18650 cells, external coverage plays a crucial role in ensuring structural integrity, mitigating the impact of vented gases, and protecting surrounding components and users from post-explosion hazards. Properly designed enclosures or protective layers can absorb or redirect the energy released during cell failure, limiting the propagation of debris, hot gases, and pressure waves within the pack.

Figure 8(a1,a2) demonstrates different external coverages that could be used.

Figure 8b illustrates the developed smoothed particle hydrodynamics (SPH) model established to simulate the post-explosion behavior of the battery, focusing on the interaction between the escaping gas and the external coverage after rupture of the can. Following the initial explosion event, where the cylindrical can failed along its longitudinal axis, the internal gas particles were allowed to exit through the tear and impact the outer protective layer. The external coverage was modeled using three-dimensional solid elements (C3D8R), with boundary conditions applied to fix the lateral sides. The gas was represented using SPH particles, which were assigned a prescribed temperature field corresponding to the residual thermal and pressure states obtained from the preceding explosion simulations. This approach enabled the realistic representation of the dynamic loading exerted by the hot, expanding gas on the outer coverage structure under post-failure conditions.

Figure 9 presents the resulting distribution of plastic strain (normalized with fracture strain) on the external coverage induced by the escaping gas for initial pressures of 6.896 MPa. The maximum strain values are localized along the central region, directly aligned with the gas outflow path, indicating the most intense deformation zone. The strain magnitude gradually decreases toward the boundaries, signifying energy dissipation through the coverage. The observed plastic strain pattern confirms that gas ejection following the can rupture can significantly deform the outer coverage, although the damage remains largely confined to the impact zone. This simulation thus provides valuable insights into the secondary mechanical effects following battery explosion and demonstrates the applicability of the SPH approach in capturing complex post-failure interactions between gas particles and solid enclosures.

Although the present SPH-based framework provides valuable insights into the explosion dynamics and post-failure behavior of cylindrical 18650 battery systems, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the simulations were conducted under idealized and axisymmetric conditions, neglecting potential manufacturing defects, material anisotropy, or weld irregularities that may influence real-world rupture initiation. Second, the gas was modeled as a homogeneous and thermodynamically ideal medium, without explicitly resolving multiphase effects such as electrolyte vaporization, solid–gas reactions, or the presence of combustion products, which could alter the local pressure–temperature evolution during thermal runaway. Third, the metallic can and external coverage were assumed to behave according to isotropic plasticity with predefined fracture strain limits, while rate-dependent or temperature-dependent constitutive effects were not included. Fourth, the coupling between electrochemical heat generation and gas pressurization was not modeled explicitly; instead, the initial temperature and pressure fields were prescribed based on equilibrium assumptions. Finally, experimental validation of the simulated deformation and pressure histories remains limited due to the challenges of measuring transient phenomena during actual battery explosions. Future work should aim to incorporate more detailed multiphysics coupling, material characterization, and experimental verification to enhance the predictive capability and generality of the proposed SPH model.