Comparative Study of Lipid Quality from Edible Insect Powders and Selected Cereal Flours Under Storage Conditions

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Samples for Analyses and Storage

2.3. Analytical Techniques

2.3.1. Lipid Extraction (Bligh–Dyer Method)

2.3.2. Lipid Oxidation Level

2.3.3. Antioxidant Activity

2.3.4. Fatty Acid Composition Analysis

2.3.5. Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

2.3.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

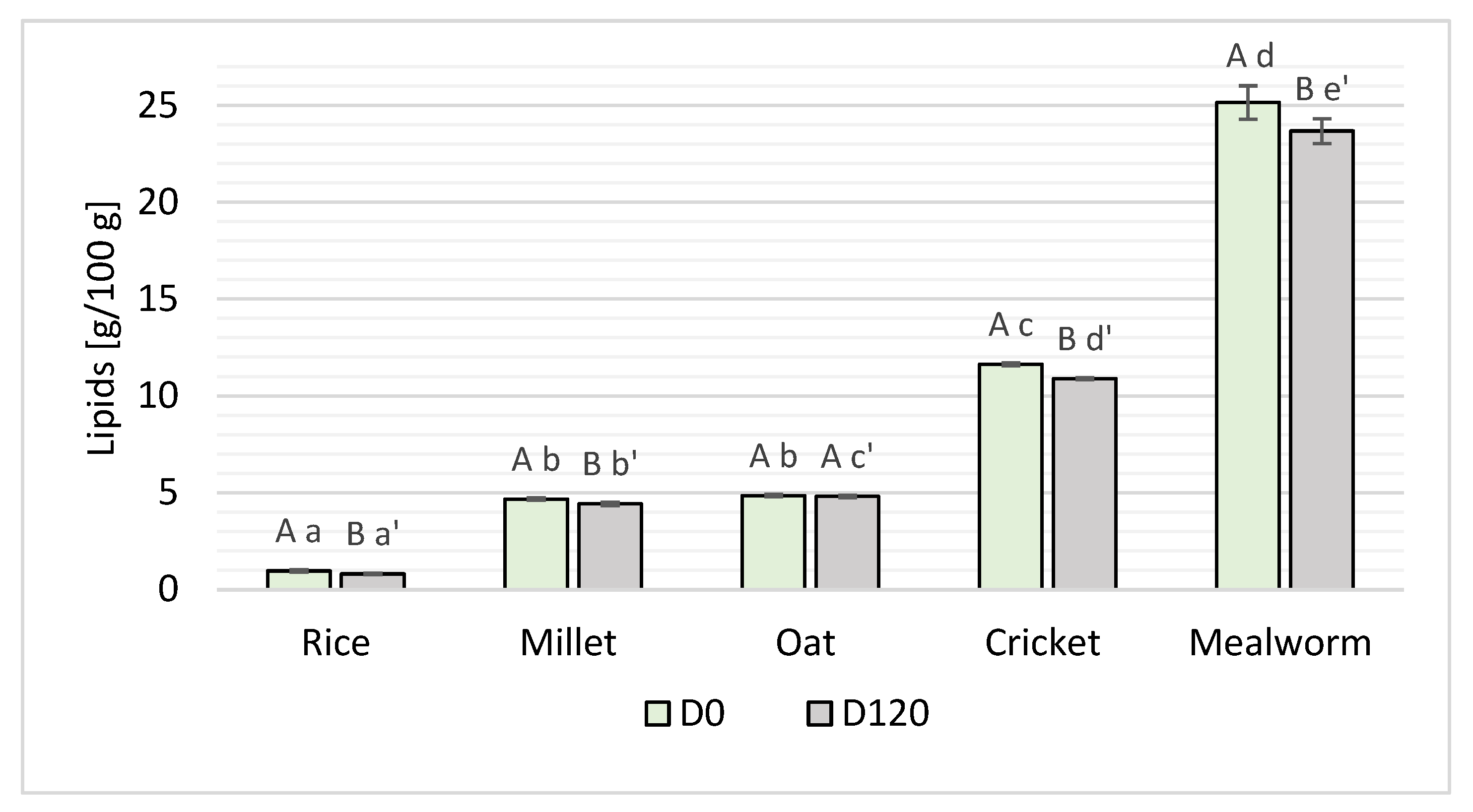

3.1. Lipid Content

3.2. Lipid Oxidation

3.3. Antioxidant Activity

3.4. Fatty Acid Composition of Lipids

3.5. DSC Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Name |

| AI | atherogenic index |

| DSC | differential scanning calorimetry |

| Ea | activation energy |

| FAME | fatty acid methyl ester |

| FID | flame ionization detector |

| h/H | hypocholesterolemic/hypercholesteolemic ratio |

| k | rate constant |

| KAS | Kissinger–Akahira–Sunose |

| MUFA | monounsaturated fatty acids |

| PUFA | polyunsaturated fatty acid |

| SE | standard error |

| SFA | saturated fatty acids |

| TI | thrombogenic index |

| TON | onset oxidation temperature |

| Z | pre-exponential factor |

| β | heating rate |

| τ | induction times |

References

- Lin, X.; Wang, F.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J.; Chen, J.; Yu, Y.; Peng, Y. A review on edible insects in China: Nutritional supply, environmental benefits, and potential applications. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2023, 7, 100596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchward-Venne, T.A.; Pinckaers, P.J.; van Loon, J.J.; van Loon, L.J. Consideration of insects as a source of dietary protein for human consumption. Nutr. Rev. 2017, 75, 1035–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barroso, F.G.; Sánchez-Muros, M.J.; Segura, M.; Morote, E.; Torres, A.; Ramos, R.; Guil, J.L. Insects as food: Enrichment of larvae of Hermetia illucens with omega 3 fatty acids by means of dietary modifications. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2017, 62, 8–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J.; He, R.; Ma, J.; Chen, C.; Liu, L. A New Strategy for Consumption of Functional Lipids from Ericerus pela (Chavannes): Study on Microcapsules and Effervescent Tablets Containing Insect Wax–Derived Policosanol. Foods 2023, 12, 3567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abutaha, N.; Al-Mekhlafi, F.A. The impact of drying and extraction methods on total lipid, fatty acid profile, and cytotoxicity of Tenebrio molitor larvae. Open Chem. 2024, 22, 20240110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz, R.M.S.; da Silva, C.; da Silva, E.A.; Hegel, P.; Barao, C.E.; Cardozo-Filho, L. Composition and oxidative stability of oils extracted from Zophobas morio and Tenebrio molitor using pressurized n-propane. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2022, 181, 105504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kępińska-Pacelik, J.; Biel, W.; Podsiadło, C.; Tokarczyk, G.; Biernacka, P.; Bienkiewicz, G. Nutritional value of banded cricket and mealworm larvae. Foods 2023, 12, 4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolobe, S.D.; Manyelo, T.G.; Malematja, E.; Sebola, N.A.; Mabelebele, M. Fats and major fatty acids present in edible insects utilised as food and livestock feed. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2023, 22, 100312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoops, J.; Vandeweyer, D.; Crauwels, S.; Verreth, C.; Boeckx, H.; Van Der Borght, M.; Van Campenhout, L. Minced meat-like products from mealworm larvae (Tenebrio molitor and Alphitobius diaperinus): Microbial dynamics during production and storage. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2017, 41, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes Martins, V.M.; Milano, P.; Rodrigues Pollonio, M.A.; dos Santos, M.; de Oliveira, A.P.; Savay-da-Silva, L.K.; de Souza Paglarini, C. Adding cricket (Gryllus assimilis) flour in hybrid beef patties: Physicochemical, technological and sensory challenges. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 450–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, V.; Campos, L.; Ribeiro, N.; Costa, R.; Correia, P.; Goncalves, J.; Henriques, M. Insect flour as milk protein substitute in fermented dairy products. Food Biosci. 2024, 60, 104379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mierzejewska, S.; Domiszewski, Z.; Piepiórka-Stepuk, J.; Bielicka, A.; Szpicer, A.; Wojtasik-Kalinowska, I. Analysis of the Impact of the Addition of Alphitobius diaperinus Larval Powder on the Physicochemical, Textural, and Sensorial Properties of Shortbread Cookies. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 4269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinopoulou, A.; Kagioglou, G.; Vacharakis, N.; Raphaelides, S.; Papageorgiou, M. Effects of the incorporation of male honey bees on dough properties and on wheat flour bread’s quality characteristics. Foods 2023, 12, 4411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashanth, P.; Joshi, T.J.; Singh, S.M.; Rao, P.S. Impact of hydrothermal treatment on functional properties of pearl millet flour: Process modelling and optimisation. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2024, 18, 7627–7640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sruthi, N.U.; Rao, P.S. Effect of processing on storage stability of millet flour: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 112, 58–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Tomer, V.; Kaur, A.; Kumar, V.; Gupta, K. Millets: A solution to agrarian and nutritional challenges. Agric. Food Secur. 2018, 7, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartosz, G. Druga Twarz Tlenu; PWN: Warszawa, Poland, 2003; ISBN 978-83-01-13847-9. [Google Scholar]

- Wąsowicz, E.; Gramza, A.; Hęś, M.; Jeleń, H.H.; Korczak, J.; Małecka, M.; Mildner–Szkudlarz, S.; Rudzińska, M.; Samotyja, U.; Zawirska–Wojtasiak, R. Oxidation of lipids in food. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2004, 54, 87–100. [Google Scholar]

- EFSA Scientific opinion on fish oil for human consumption. Food hygiene, including rancidity. EFSA J. 2010, 10, 1874.

- Maszewska, M.; Florowska, A.; Dłużewska, E.; Wroniak, M.; Marciniak-Lukasiak, K.; Żbikowska, A. Oxidative Stability of Selected Edible Oils. Molecules. 2018, 23, 1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yehuda, S.; Rabinovitz, S.; Carass, R.L.; Mostofsky, D.I. The role of polyunsaturated fatty acids in restoring the aging neuronal membrane. Neurobiol. Aging 2002, 23, 843–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farooqui, A.A.; Horrocks, L.A. Lipid peroxides in the free radical patho-physiology of brain diseases. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 1998, 18, 599–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frankel, E.N. Lipid Oxidation, 2nd ed.; Oily Press: Bridgwater, UK, 2005; ISBN 0953194981. [Google Scholar]

- Molteberg, E.L.; Magnus, E.M.; Bjørge, J.M.; Nilsson, A. Sensory and chemical studies of lipid oxidation in raw and heat-treated oat flours. Cereal Chem. 1996, 73, 579–587. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, K.; Liu, Y.; Chen, F. Effect of storage temperature on lipid oxidation and changes in nutrient contents in peanuts. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 2280–2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeleń, H.; Mildner–Szkudlarz, S.; Jasińska, I.; Wąsowicz, E. A headspace–SPME–MS method for monitoring rapeseed oil autoxidation. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2007, 84, 509–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bligh, E.G.; Dyer, W.J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can. J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959, 37, 911–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domiszewski, Z.; Mierzejewska, S. Effect of Technological Process on True Retention Rate of Eicosapentaenoic and Docosahexaenoic Acids, Lipid Oxidation and Physical Properties of Canned Smoked Sprat (Sprattus sprattus). Int. J. Food Sci. 2021, 2021, 5539376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzyk, C. Spectrophotometric determination of lipid peroxides by tiocyanate technique. Roczn. Panst. Zak. Hig. 1958, 9, 75–84. [Google Scholar]

- AOCS Official Methods and Recommended Practices of the American Oil Chemists’ Society, 6th ed.; AOCS Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2003.

- Li, W.; Pickard, M.D.; Beta, T. Evaluation of antioxidant activity and electronic taste and aroma properties of antho-beers from purple wheat grain. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 8958–8966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Nanguet, A.L.; Beta, T. Comparison of Antioxidant Properties of Refined and Whole Wheat Flour and Bread. Antioxidants 2013, 2, 370–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity, LWT. Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bińkowska, W.; Szpicer, A.; Stelmasiak, A.; Wojtasik-Kalinowska, I.; Półtorak, A. Innovative Application of Microencapsulated Polyphenols in Cereal Products: Optimization of the Formulation of Dairy- and Gluten-Free Pastry. J. Food Process Eng. 2024, 47, e14685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulbricht, T.L.V.L.V.; Southgate, D.A.T.A.T. Coronary Heart Disease: Seven Dietary Factors. Lancet 1991, 338, 985–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szpicer, A.; Onopiuk, A.; Wojtasik-Kalinowska, I.; Półtorak, A. Red Grape Skin Extract and Oat β-Glucan in Shortbread Cookies: Technological and Nutritional Evaluation. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 1999–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdalla, A.A.; El Tinay, A.H.; Mohamed, B.E.; Abdalla, A.H. Proximate composition, starch, phytate and mineral contents of 10 pearl millet genotypes. Food Chem. 1998, 63, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokinen, I.; Pihlava, J.M.; Puganen, A.; Sontag-Strohm, T.; Linderborg, K.M.; Holopainen-Mantila, U.; Nordlund, E. Predicting the properties of industrially produced oat flours by the characteristics of native oat grains or non-heat-treated groats. Foods 2021, 10, 1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronie, M.E.; Hasmadi, M. Factors affecting the properties of rice flour: A review. Food Res. 2022, 6, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorrette, B.; Sanchez, L. New lipid sources in the insect industry, regulatory aspects and applications. OCL 2022, 29, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biel, W.; Kazimierska, K.; Bashutska, U. Wartość odżywcza ziaren pszenicy, pszenżyta, jęczmienia i owsa. Acta Sci. Pol. Zootech. 2020, 19, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sikorski, Z.E.; Pan, B.S. The effect of heat–induced changes in nitrogenous on the properties of seafoods. In Seafood Proteins; Sikorski, Z.E., Pan, B.S., Shahidi, F., Eds.; Chapman & Hall: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 84–98. ISBN 978-1-4615-7830-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pokorny, J.; Kołakowska, A.; Bienkiewicz, G. Lipid–protein and lipid–saccharide interactions. In Chemical and Functional Properties of Food Lipids; Sikorski, Z.E., Kołakowska, A., Eds.; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 455–472. ISBN 978-1-58716-105-6. [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski, Z.E.; Kolakowska, A. Chemical and Functional Properties of Food Lipids; CRC Press: Boca Raton, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, M. Protein carbonyls in meat systems: A review. Meat Sci. 2011, 89, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelderss, G.G.; Goesaert, H.; Delcour, J.A. Amylose-lipid complexes as controlled lipid release agents during starch gelatinization and pasting. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 1493–1499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Putseys, J.A.; Lamberts, L.; Delcour, J.A. Amylose-inclusion complexes: Formation, identity and physico-chemical properties. J. Cereal Sci. 2010, 51, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F.; Zhong, Y. Lipid oxidation and improving the oxidative stability. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010, 39, 4067–4079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokorny, J.; Janicek, G.; Davidek, J. Determination of the interaction products of proteins with lipids. Zesz. Probl. Post. Nauk Rol. 1975, 167, 155–170. [Google Scholar]

- Codex Alimentarius 2011; Codex Standard; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2011; pp. 33–198. ISBN 978-92-5-107006-2.

- GOED. Voluntary Monograph for Omega-3; GOED: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, S.S. Food Analysis Laboratory Mannual, 2nd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiokias, S.; Varzakas, T.H.; Arvanitoyannis, I.S.; Labropoulos, A.E. Advances in Food Biochemistry, 1st ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Goswami, S.; Kumar, R.R.; Singh, T.; Ali, A.; Meena, M.C.; Singh, S.P.; Satyavathi, C.T. Insights into recent techniques for improving shelf life and value addition in pearl millet flour: A mini review on recent advances. Ann. Arid Zone 2023, 62, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gumus, C.E.; Decker, E.A. Oxidation in low moisture foods as a function of surface lipids and fat content. Foods 2021, 10, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Kumar, R.R.; Vinutha, T.; Bansal, N.; Bollinedi, H.; Singh, S.P.; Goswami, S. Characterization of biochemical indicators and metabolites linked with rancidity and browning of pearl millet flour during storage. J. Plant Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 32, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estévez, M.; Ventanas, S.; Cava, R. Physicochemical properties and oxidative stability of liver pâté as affected by fat content. Food Chem. 2005, 92, 449–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/4/y4705e/y4705e22.htm (accessed on 19 November 2025).

- Ngamnikom, P.; Songsermpong, S. The effects of freeze, dry, and wet grinding processes on rice flour properties and their energy consumption. J. Food Eng. 2011, 104, 632–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Zheng, J.; Liu, F.; Woo, M.W.; Xiong, H.; Zhao, Q. Fabrication and characterization of oat flour processed by different methods. J. Cereal Sci. 2020, 96, 103123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naraharasetti, B.; Chakraborty, S.; Siliveru, K.; Prasad, P.V. Thermal and nonthermal processing of pearl millet flour: Impact on microbial safety, enzymatic stability, nutrients, functional properties, and shelf-life extension. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2025, 24, e70190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kröncke, N.; Böschen, V.; Woyzichovski, J.; Demtröder, S.; Benning, R. Comparison of suitable drying processes for mealworms (Tenebrio molitor). Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 50, 20–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ssepuuya, G.; Nakimbugwe, D.; Van Campenhout, L.; De Winne, A.; Claes, J.; Van Der Borght, M. Towards establishing the spoilage mechanisms of the long-horned grasshopper Ruspolia differens Serville. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2021, 247, 2915–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, J.Y.; Kim, M.R.; Kim, Y.J.; Kim, J.H.; Han, J.; Choi, Y.S. Influence of the drying method on the physicochemical properties, volatile compounds, and odor characteristics of edible insect oils. Food Res. Int. 2025, 220, 117088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Xing, X.; Chen, X.; Li, M.; Liu, F.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, Q. Six edible insect oils extracted by ultrasound-assisted: Physicochemical characteristics, aroma patterns and antioxidant properties. Future Foods 2025, 11, 100662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osimani, A.; Milanović, V.; Cardinali, F.; Roncolini, A.; Garofalo, C.; Clementi, F.; Aquilanti, L. Bread enriched with cricket powder (Acheta domesticus): A technological, microbiological and nutritional evaluation. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2018, 48, 150–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojha, S.; Bußler, S.; Psarianos, M.; Rossi, G.; Schlüter, O.K. Edible insect processing pathways and implementation of emerging technologies. J. Insects Food Feed 2021, 7, 877–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, E.S.; Hibbs, A.N. Wheat Flour Milling; American Association of Cereal Chemists, Inc.: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domiszewski, Z.; Mierzejewska, S.; Michalska-Pożoga, I.; Rybka, K.; Rydzkowski, T. Effect of graphene and graphene oxide addition to polyethylene film on lipid quality of African Catfish (Clarias gariepinus) fillets during refrigerated storage. Coatings 2024, 14, 1506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robards, K.; Kerr, A.F.; Patsalides, E. Rancidity and its measurement in edible oils and snack foods. A review. Analyst 1988, 113, 213–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brash, A.R. Lipoxygenases: Occurrence, functions, catalysis, and acquisition of substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 23679–23682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampi, A.M.; Damerau, A.; Li, J.; Moisio, T.; Partanen, R.; Forssell, P.; Piironen, V. Changes in lipids and volatile compounds of oat flours and extrudates during processing and storage. J. Cereal Sci. 2015, 62, 102–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xiao, H.; Lyu, X.; Chen, H.; Wei, F. Lipid oxidation in food science and nutritional health: A comprehensive review. Oil Crop Sci. 2023, 8, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bienkiewicz, G.; Kołakowska, A. Effect of lipid oxidation on fish lipids–amylopectin interactions. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2023, 105, 410–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, R.; Pateiro, M.; Gagaoua, M.; Barba, F.J.; Zhang, W.; Lorenzo, J.M. A comprehensive review on lipid oxidation in meat and meat products. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak–Łukasiak, K.; Żbikowska, A.; Krygier, K. Influence of use of nitrogwn into oxidative of rapseed and linseed oils. Żyw. Nauka Techmol. Jak. 2006, 132, 206–215. [Google Scholar]

- Goufo, P.; Trindade, H. Factors influencing antioxidant compounds in rice. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 893–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marzoli, F.; Tata, A.; Zacometti, C.; Malabusini, S.; Jucker, C.; Piro, R.; Belluco, S. Microbial and chemical stability of Acheta domesticus powder during one year storage period at room temperature. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1179088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzola-Rodríguez, S.I.; Muñoz-Castellanos, L.N.; López-Camarillo, C.; Salas, E. Phenolipids, amphipilic phenolic antioxidants with modified properties and their spectrum of applications in development: A review. Biomolecules 2022, 12, 1897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilci, A.; Gocmen, D. Phenolic acid composition, antioxidant activity and phenolic content of tarhana supplemented with oat flour. Food Chem. 2014, 151, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruni, A.R.S.; Alves, E.S.; Campos, T.A.F.; Carvalho, L.C.; Santos Júnior, O.O. Incorporation of natural antioxidants into biodegradable food packaging: Enhancing food quality and shelf life. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2025, 36, e20250074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Pineda, M.; Juan, T.; Antoniewska-Krzeska, A.; Vercet, A.; Abenoza, M.; Yagüe-Ruiz, C.; Rutkowska, J. Exploring the potential of yellow mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) oil as a nutraceutical ingredient. Foods 2024, 13, 3867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharibzahedi, S.M.T.; Altintas, Z. Lesser mealworm (Alphitobius diaperinus L.) larvae oils extracted by pure and binary mixed organic solvents: Physicochemical and antioxidant properties, fatty acid composition, and lipid quality indices. Food Chem. 2023, 408, 135209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikołajczak, N.; Tańska, M.; Ogrodowska, D. Phenolic compounds in plant oils: A review of composition, analytical methods, and effect on oxidative stability. Trends Food Sci. Tech. 2021, 113, 110–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamuangmorn, S.; Sreethong, T.; Saenchai, C.; Rerkasem, B.; Prom-U-Thai, C. Effects of roasting conditions on anthocyanin, total phenolic content, and antioxidant capacity in pigmented and non-pigmented rice varieties. Int. Food Res. J. 2021, 28, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decker, E.A.; Livisay, S.A.; Zhou, S. Mechanism of Endogenous Skeletal Muscle Antioxidants: Chemical and Physical Aspects. In Antioxidants in Muscle Foods: Nutritional Strategies to Improve Quality; Decker, E.A., Faustman, C., Lopez-Bote, C.J., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000; ISBN 978-0-471-31454-7. [Google Scholar]

- Losada-Barreiro, S.; Paiva-Martins, F.; Bravo-Díaz, C. Analysis of the efficiency of antioxidants in inhibiting lipid oxidation in terms of characteristic kinetic arameters. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Mumper, R.J. Plant phenolics: Extraction, analysis and their antioxidant and anticancer properties. Molecules 2010, 15, 7313–7352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmons, C.L.; Peterson, D.M.; Paul, G.L. Antioxidant capacity of oat (Avena sativa L.) extracts. 2. In vitro antioxidant activity and contents of phenolic and tocol antioxidants. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1999, 47, 4894–4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palupi, E.; Nasir, S.Q.; Jayanegara, A.; Susanto, I.; Ismail, A.; Chandra, A.; Setiawan, B.; Sulaeman, A.; Damanik, M.R.M.; Filianty, F. Meta-Analysis on the Fatty Acid Composition of Edible Insects as a Sustainable Food and Feed. Future Foods 2025, 11, 100529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkusz, A.; Dymińska, L.; Banaś, K.; Harasym, J. Chemical and Nutritional Fat Profile of Acheta domesticus, Gryllus bimaculatus, Tenebrio molitor and Rhynchophorus ferrugineus. Foods 2024, 13, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chantakun, K.; Petcharat, T.; Wattanachant, S.; Karim, M.S.B.A.; Kaewthong, P. Fatty Acid Profile and Thermal Behavior of Fat-Rich Edible Insect Oils Compared to Commonly Consumed Animal and Plant Oils. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2024, 44, 790–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardo, Y.A.A.; Conte-Junior, C.A. Oxidative Stability in Edible Insects: Where Is the Knowledge Frontier? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 148, 104518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orkusz, A. Edible insects versus meat-nutritional comparison: Knowledge of their composition is the key to good health. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mlcek, J.; Adamkova, A.; Adamek, M.; Borkovcova, M.; Bednarova, M.; Knizkova, I. Fat from Tenebrionidae bugs—Sterols content, fatty acid profiles, and cardiovascular risk indexes. Pol. J. Food Nutr. Sci. 2019, 69, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilami, S.K.; Kouřimská, L. Assessment of the nutritional quality of plant lipids using atherogenicity and thrombogenicity indices. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oonincx, D.G.A.B.; Laurent, S.; Veenenbos, M.E.; Loon, J.J.A. Van Dietary Enrichment of edible insects with Omega 3 fatty acids. Insect Sci. 2020, 27, 500–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riekkinen, K.; Väkeväinen, K.; Korhonen, J. The Effect of Substrate on the Nutrient Content and fatty acid composition of edible insects. Insects 2022, 13, 590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirkowska-Wojdyła, M.; Ostrowska-Lig, E.; Agata, G.; Bry, J. Application of chromatographic and thermal methods to study fatty acids composition and positional distribution, oxidation kinetic parameters and melting profile as important factors characterizing amaranth and quinoa oils. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 2166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, B.; Zhang, Q.; Sui, X.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Jiang, L. Differential scanning calorimetry study–assessing the Influence of composition of vegetable oils on oxidation. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 601–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, M.; Kaczmarek, A.; Tomaszewska-Gras, J. Differential scanning calorimetry as a tool to assess the oxidation state of cold-pressed oils during shelf-life. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2023, 17, 6639–6651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosme, P.; Rodríguez, A.B.; Espino, J.; Garrido, M. Plant phenolics: Bioavailability as a key determinant of their potential health-promoting applications. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rastrelli, L.; Passi, S.; Ippolito, F.; Vacca, G.; Simone, F.D. Rate of degradation of α-tocopherol, squalene, phenolics, and polyunsaturated fatty acids in olive oil during different storage conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 5566–5570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amft, J.; Meissner, P.M.; Stöckmann, H.; Meynier, A.; Vermoesen, A.; Forte, E.; Steffen-heins, A.; Hasler, M.; Birault, L.; Velasco, J.; et al. Interlaboratory study on lipid oxidation during accelerated storage trials with rapeseed and sunflower oil analyzed by conjugated dienes as primary oxidation products. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2023, 125, 2300067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cichocki, W.; Kmiecik, D.; Baranowska, H.M.; Staroszczyk, H.; Sommer, A.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł. Chemical characteristics and thermal oxidative stability of novel Cold-pressed oil blends: GC, LF NMR, and DSC studies. Foods 2023, 12, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banaś, J.; Maciejaszek, I.; Surówka, K.; Zawiślak, A. Temperature—Induced storage quality changes in pumpkin and safflower cold—Pressed oils. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2020, 14, 1213–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, Y.; Son, Y.; Kim, S.; Yun, E.; Kang, H.; Hwang, I. Physicochemical properties and oxidative stabilities of mealworm (Tenebrio molitor) oils under different roasting conditions. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2016, 25, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| PV [meq O2/kg Lipids] | p-AsV | TOTOX | |

|---|---|---|---|

| D0 | 2.62 ± 0.10 Aa | 1.56 ± 0.11 Aa | 6.80 ± 0.29 Aa |

| D120 | 2.74 ± 0.22 Aa’ | 1.84 ± 0.13 Aa’ | 7.32 ± 0.35 Aa’ |

| D0 | 5.60 ± 0.24 Ac | 4.13 ± 0.31 Ac | 15.33 ± 0.79 Ac |

| D120 | 6.20 ± 0.18 Bc’ | 5.14 ± 0.38 Bc’ | 17.54 ± 0.81 Bc’ |

| D0 | 4.40 ± 0.10 Ab | 3.57 ± 0.24 Ab | 12.37 ± 0.59 Ab |

| D120 | 4.72 ± 0.11 Bb’ | 4.28 ± 0.26 Ab’ | 13.72 ± 0.69 Bb’ |

| D0 | 6.85 ± 0.15 Ad | 5.21 ± 0.21 Ad | 18.91 ± 0.88 Ad |

| D120 | 7.78 ± 0.31 Bd’ | 6.56 ± 0.26 Bd’ | 22.12 ± 1.05 Bd’ |

| D0 | 9.89 ± 0.16 Ae | 7.56 ± 0.29 Ae | 27.34 ± 1.42 Ae |

| D120 | 11.58 ± 0.21 Be’ | 9.83 ± 0.44 Be’ | 32.99 ± 1.61 Be’ |

| Fatty Acid | Rice D0 | Rice D120 | Millet D0 | Millet D120 | Oat D0 | Oat D120 | Cricket D0 | Cricket D120 | Mealworm D0 | Mealworm D120 | SEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C12:0 | ND a | 0.02± 0.00 b’ | ND a | ND a’ | ND a | ND a’ | 0.10 ± 0.00 aB | 0.09 ± 0.00 c’A | 0.20 ± 0.00 b | 0.20 ± 0.00 d’ | 0.008 |

| C13:0 | ND a | ND a’ | ND a | ND a’ | ND a | ND a’ | ND a | ND a’ | 0.06 ± 0.00 b | 0.06 ± 0.01 b’ | 0.003 |

| C14:0 | 0.46 ± 0.01 cA | 0.56 ± 0.03 c’B | 0.10 ± 0.00 aB | 0.05 ± 0.01 a’A | 0.23 ± 0.00 bB | 0.21 ± 0.00 b’B | 0.84 ± 0.01 d | 0.81 ± 0.04 d’ | 3.80 ± 0.00 e | 3.80 ± 0.01 e’ | 0.147 |

| C14:1 | ND a | ND a’ | ND a | ND a’ | ND a | ND a’ | 0.05 ± 0.01 bA | 0.16 ± 0.03 b’B | 0.01 ± 0.00 a | 0.01 ± 0.00 a’ | 0.005 |

| C15:0 | ND a | ND a’ | ND a | ND a’ | ND a | ND a’ | 0.06 ± 0.00 b | 0.09 ± 0.02 b’ | 0.09 ± 0.00 c | 0.11 ± 0.01 b’ | 0.005 |

| C16:0 | 19.78 ± 0.06 d | 19.66 ± 0.05 d’ | 8.51 ± 0.02 aB | 8.21 ± 0.02 a’A | 16.67 ± 0.02 c | 16.67 ± 0.02 c’ | 25.74 ± 0.02 eA | 25.96 ± 0.04 e’B | 15.56 ± 0.01 bB | 15.50 ± 0.01 b’A | 0.603 |

| C16:1 | 0.18 ± 0.01 aA | 0.58 ± 0.01 b’B | 0.23 ± 0.00 b | 0.21 ± 0.01 a’ | 0.24 ± 0.01 b | 0.22 ± 0.00 a’ | 0.84 ± 0.01 c | 0.98 ± 0.08 c’ | 2.56 ± 0.00 d | 2.59 ± 0.03 d’ | 0.096 |

| C17:0 | ND aA | 0.09 ± 0.00 ab’B | ND aA | 0.16 ± 0.04 b’B | 0.04 ± 0.00 b | 0.04 ± 0.00 a’ | 0.27 ± 0.00 c | 0.31 ± 0.03 c’ | 0.37 ± 0.00 d | 0.37 ± 0.00 c’ | 0.016 |

| C17:1 | ND aA | 0.02 ± 0.00 a’B | ND aA | 0.04 ± 0.01 a’B | 0.02 ± 0.00 b | 0.02 ± 0.00 a’ | 0.34 ± 0.01 d | 0.35 ± 0.01 c’ | 0.18 ± 0.00 cA | 0.19 ± 0.00 b’B | 0.014 |

| C18:0 | 2.15 ± 0.02 bA | 4.66 ± 0.07 d’B | 1.56 ± 0.19 a | 1.78 ± 0.04 b’ | 1.58 ± 0.01 a | 1.56 ± 0.00 a’ | 10.54 ± 0.01 d | 10.48 ± 0.02 e’ | 2.90 ± 0.00 cB | 2.91 ± 0.00 c’A | 0.360 |

| C18:1 trans | 0.35 ± 0.01 bB | 0.04 ± 0.01 b’A | ND a | 0.02 ± 0.01 ab’ | ND a | ND a’ | 0.09 ± 0.02 aB | 0.02 ± 0.00 ab’A | 0.02 ± 0.00 a | 0.03 ± 0.00 ab’ | 0.016 |

| C18:1 cis | 37.76 ± 0.15 d | 37.89 ± 0.02 d’ | 22.07 ± 0.06 a | 22.21 ± 0.05 a’ | 36.97 ± 0.00 cA | 37.32 ± 0.05 c’B | 22.75 ± 0.02 b | 22.67 ± 0.04 b’ | 43.65 ± 0.01 eB | 43.34 ± 0.02 e’A | 0.918 |

| C18:2 9.12 cis | 34.81 ± 0.13 bB | 31.86 ± 0.01 a’B | 63.31 ± 0.17 e | 63.72 ± 0.06 e’ | 40.54 ± 0.05 d | 40.37 ± 0.06 d’ | 36.00 ± 0.03 c | 36.13 ± 0.07 c’ | 29.27 ± 0.02 aA | 29.63 ± 0.02 a’B | 1.273 |

| C18:3 6.9.12 | ND a | ND a | ND a | ND a’ | 0.03 ± 0.00 ab | 0.03 ± 0.00 b’ | ND a | ND a’ | 0.08 ± 0.00 b | ND a’ | 0.005 |

| C18:3 9.12.15 | 1.47 ± 0.00 eB | 1.30 ± 0.00 c’A | 0.90 ± 0.00 cB | 0.52 ± 0.01 b’A | 1.26 ± 0.00 d | 1.30 ± 0.04 c’ | 0.44 ± 0.00 aB | 0.25 ± 0.07 a’A | 0.57 ± 0.00 bA | 0.59 ± 0.00 b’B | 0.044 |

| C20:0 | 0.73 ± 0.02 e | 0.73 ± 0.00 e’ | 0.57 ± 0.00 dB | 0.55 ± 0.01 d’A | 0.14 ± 0.00 b | 0.15 ± 0.01 b’ | 0.25 ± 0.00 cA | 0.28 ± 0.01 c’B | 0.09 ± 0.00 aA | 0.11 ± 0.01 a’B | 0.026 |

| C20:1 | 0.54 ± 0.03 cA | 0.67 ± 0.00 b’B | 0.60 ± 0.01 dB | 0.25 ± 0.00 a’A | 0.85 ± 0.01 eA | 0.93 ± 0.04 c’B | 0.08 ± 0.00 a | 0.10 ± 0.01 a’ | 0.14 ± 0.00 b | 0.13 ± 0.00 a’ | 0.037 |

| C21:0 | ND aA | 0.22 ± 0.00 b’B | 0.08 ± 0.00 dA | 1.35 ± 0.01 c’B | 0.04 ± 0.00 bA | 0.13 ± 0.04 ab’B | 0.06 ± 0.00 c | 0.12 ± 0.03 ab’ | 0.06 ± 0.00 c | 0.06 ± 0.00 a’ | 0.037 |

| C20:3 8.11.14 | ND aA | 0.03 ± 0.01 ab’B | ND a | ND a’ | ND aA | 0.05 ± 0.02 abc’B | 0.13 ± 0.00 c | 0.11 ± 0.01 c’ | 0.08 ± 0.00 bB | 0.07 ± 0.00 bc’A | 0.006 |

| C20:4 | ND aA | 0.17 ± 0.06 b’B | ND aA | ND a’ | ND a | 0.10 ± 0.02 ab’B | 0.06 ± 0.00 b | 0.06 ± 0.00 ab’ | ND a | ND a’ | 0.008 |

| C22:0 | 0.31 ± 0.00 cB | 0.16 ± 0.06 b’A | 0.39 ± 0.00 dB | 0.37 ± 0.00 c’A | 0.07 ± 0.00 bB | ND a’A | 0.06 ± 0.00 b | 0.07 ± 0.01 ab’ | ND a | ND a’ | 0.017 |

| C22:1 | ND a | ND a’ | 0.19 ± 0.01 dB | 0.16 ± 0.00 b’A | 0.10 ± 0.00 cB | ND a’A | 0.08 ± 0.00 bB | ND a’A | ND a | ND a’ | 0.007 |

| C22:2 | 0.12 ± 0.00 bA | 0.43 ± 0.11 b’B | ND a | ND a | 0.29 ± 0.00 bA | 0.50 ± 0.02 b’B | ND a | ND a’ | ND a | ND a’ | 0.021 |

| C23:0 | 0.44 ± 0.04 bB | 0.09 ± 0.01 ab’A | 1.04 ± 0.23 cB | 0.07 ± 0.01 a’A | 0.75 ± 0.00 bcB | 0.18 ± 0.04 b’A | 0.35 ± 0.00 abB | 0.08 ± 0.00 ab’A | ND a | ND a’ | 0.044 |

| C24:0 | 0.91 ± 0.25 b | 0.83 ± 0.01 c’ | 0.45 ± 0.00 aB | 0.32 ± 0.02 b’A | 0.10 ± 0.00 a | 0.14 ± 0.03 a’ | 0.15 ± 0.01 a | 0.17 ± 0.02 a’ | 0.21 ± 0.00 a | 0.21 ± 0.00 a’ | 0.040 |

| C24:1 | ND a | ND a | ND a | ND a | 0.06 ± 0.00 b | 0.06 ± 0.00 ab’ | 0.05 ± 0.01 bA | 0.19 ± 0.03 c’B | 0.10 ± 0.00 cA | 0.11 ± 0.00 b’B | 0.006 |

| C22:6 | ND a | ND a | ND a | ND a | ND a | ND a’ | 0.65 ± 0.00 b | 0.51 ± 0.04 b’ | ND a | ND a’ | 0.026 |

| ΣSFA | 24.77 ± 0.21 dA | 27.02 ± 0.05 d’B | 12.71 ± 0.23 a | 12.87 ± 0.09 a’ | 19.64 ± 0.04 bB | 19.09 ± 0.05 b’A | 38.43 ± 0.04 e | 38.46 ± 0.04 e’ | 23.34 ± 0.01 c | 23.32 ± 0.02 c’ | 0.901 |

| ΣMUFA | 38.82 ± 0.09 dA | 39.20 ± 0.03 d’B | 23.08 ± 0.06 aB | 22.89 ± 0.04 a’A | 38.23 ± 0.02 cA | 38.56 ± 0.02 c’B | 24.28 ± 0.04 b | 24.47 ± 0.09 b’ | 46.65 ± 0.01 eB | 46.39 ± 0.01 e’A | 0.967 |

| ΣPUFA | 36.40 ± 0.15 bB | 33.79 ± 0.04 b’A | 64.21 ± 0.17 e | 64.24 ± 0.05 e’ | 42.13 ± 0.05 dA | 42.36 ± 0.03 d’B | 37.29 ± 0.04 cB | 37.07 ± 0.08 c’A | 30.01 ± 0.02 aA | 30.29 ± 0.01 a’B | 1.259 |

| PUFA/SFA | 1.47 ± 0.02 bB | 1.25 ± 0.00 b’A | 5.05 ± 0.11 d | 4.99 ± 0.04 d’ | 2.15 ± 0.01 cA | 2.22 ± 0.01 c’B | 0.97 ± 0.00 a | 0.96 ± 0.00 a’ | 1.29 ± 0.00 bA | 1.30 ± 0.00 b’B | 0.158 |

| AI | 0.29 ± 0.00 cA | 0.30 ± 0.00 c’B | 0.10 ± 0.00 a | 0.10 ± 0.00 a’ | 0.22 ± 0.00 b | 0.22 ± 0.00 b’ | 0.47 ± 0.00 e | 0.48 ± 0.00 e’ | 0.40 ± 0.00 d | 0.40 ± 0.00 d’ | 0.014 |

| TI | 0.54 ± 0.00 cA | 0.63 ± 0.00 d’B | 0.22 ± 0.00 a | 0.22 ± 0.00 a’ | 0.43 ± 0.00 b | 0.42 ± 0.00 b’ | 1.11 ± 0.00 eA | 1.14 ± 0.00 e’B | 0.56 ± 0.00 d | 0.56 ± 0.00 c’ | 0.032 |

| h/H | 3.66 ± 0.02 cB | 3.55 ± 0.01 b’A | 10.02 ± 0.01 eA | 10.47 ± 0.02 e’B | 4.68 ± 0.01 dA | 4.72 ± 0.00 d’B | 2.26 ± 0.00 aB | 2.23 ± 0.00 a’A | 3.80 ± 0.00 bA | 3.82 ± 0.00 c’B | 0.293 |

| n6/n3 | 23.66 ± 0.10 aA | 24.62 ± 0.05 a’B | 70.21 ± 0.17 dA | 122.06 ± 2.92 c’B | 32.15 ± 0.06 bB | 31.29 ± 0.90 a’A | 33.11 ± 0.33 bA | 47.46 ± 1.87 b’B | 51.28 ± 0.43 c | 50.35±0.35 b’ | 2.823 |

| Heating Rate. β [°C min−1] | Rice | Millet | Oat | Cricket | Mealworm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before storage (D0) | |||||

| 5 | 95.71 ± 0.01 dB | 40.46 ± 0.00 aB | 95.13 ± 0.00 cB | 85.53 ± 0.00 bB | 157.57 ± 0.01 eB |

| 7.5 | 100.38 ± 0.00 dB | 50.15 ± 0.01 aB | 99.29 ± 0.01 cB | 91.47 ± 0.00 bB | 160.47 ± 0.00 eB |

| 10 | 105.10 ± 0.00 dB | 58.73 ± 0.00 aB | 102.73 ± 0.01 cB | 96.15 ± 0.01 bB | 162.05 ± 0.00 eB |

| 12.5 | 108.18 ± 0.00 dB | 65.20 ± 0.00 aB | 105.78 ± 0.00 cB | 101.50 ± 0.01 bB | 163.83 ± 0.01 eB |

| 15 | 109.86 ± 0.01 dB | 67.83 ± 0.01 aB | 107.59 ± 0.00 cB | 103.17 ± 0.00 bB | 165.47 ± 0.00 eB |

| After storage (D120) | |||||

| 5 | 92.51 ± 0.01 c’A | 36.31 ± 0.00 a’A | 92.47 ± 0.01 c’A | 82.54 ± 0.00 b’A | 155.12 ± 0.01 d’A |

| 7.5 | 97.12 ± 0.00 d’A | 47.51 ± 0.00 a’A | 96.78 ± 0.00 c’A | 88.12 ± 0.00 b’A | 158.45 ± 0.00 e’A |

| 10 | 101.74 ± 0.00 d’A | 53.45 ± 0.01 a’A | 100.33 ± 0.00 c’A | 93.66 ± 0.00 b’A | 160.24 ± 0.00 e’A |

| 12.5 | 105.11 ± 0.01 d’A | 60.42 ± 0.00 a’A | 103.63 ± 0.01 c’A | 97.74 ± 0.01 b’A | 161.75 ± 0.01 e’A |

| 15 | 107.48 ± 0.00 d’A | 63.25 ± 0.00 a’A | 105.24 ± 0.00 c’A | 100.21 ± 0.00 b’A | 163.47 ± 0.00 e’A |

| Parameters | |||||

| Before storage (D0) | |||||

| r2 | 0.994 | 0.991 | 0.998 | 0.991 | 0.995 |

| Ea [kJ mol−1] | 81.31 ± 0.00 cB | 28.74 ± 0.00 aA | 94.54 ± 0.00 dB | 60.74 ± 0.00 bB | 215.37 ± 0.00 eB |

| log Z [s−1] | 11.08 ± 0.00 cB | 4.03 ± 0.00 aA | 13.04 ± 0.00 dB | 8.31 ± 0.00 b | 25.96 ± 0.00 eB |

| τ at 160 °C (min) | 18.63 ± 0.00 dB | 3.67 ± 0.00 bA | 43.46 ± 0.00 eB | 9.61±0.00 cA | 0.99±0.00 aA |

| τ at 170 °C (min) | 31.02±0.00 dB | 4.41±0.00 bA | 78.57±0.00 eB | 14.06±0.00 cA | 3.82 ± 0.00 aA |

| τ at 180 °C (min) | 50.48 ± 0.00 dB | 5.23 ± 0.00 aA | 138.41 ± 0.00 eB | 20.23 ± 0.00 cA | 13.87 ± 0.00 bA |

| After storage (D120) | |||||

| r2 | 0.996 | 0.990 | 0.996 | 0.996 | 0.996 |

| Ea [kJ mol−1] | 76.63 ± 0.00 c’A | 29.31 ± 0.00 a’B | 90.01 ± 0.00 d’A | 60.46 ± 0.00 b’A | 202.49 ± 0.00 e’A |

| log Z [s−1] | 10.49 ± 0.00 c’A | 4.20 ± 0.00 a’B | 12.47 ± 0.00 d’A | 8.34 ± 0.00 b’ | 24.51 ± 0.00 e’A |

| τ at 160 °C (min) | 17.96 ± 0.00 d’A | 4.65 ± 0.00 b’B | 41.61 ± 0.00 e’A | 11.36 ± 0.00 c’B | 1.25 ± 0.00 a’B |

| τ at 170 °C (min) | 29.04 ± 0.00 d’A | 5.59 ± 0.00 b’B | 73.13 ± 0.00 e’A | 16.59 ± 0.00 c’B | 4.44 ± 0.00 a’B |

| τ at 180 °C (min) | 45.94 ± 0.00 d’A | 6.67 ± 0.00 a’B | 125.36 ± 0.00 e’A | 23.83 ± 0.00 c’B | 14.94 ± 0.00 b’B |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Domiszewski, Z.; Szpicer, A.; Mierzejewska, S.; Wojtasik-Kalinowska, I.; Bińkowska, W.; Maziarz, K.; Piepiórka-Stepuk, J. Comparative Study of Lipid Quality from Edible Insect Powders and Selected Cereal Flours Under Storage Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2026, 16, 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010013

Domiszewski Z, Szpicer A, Mierzejewska S, Wojtasik-Kalinowska I, Bińkowska W, Maziarz K, Piepiórka-Stepuk J. Comparative Study of Lipid Quality from Edible Insect Powders and Selected Cereal Flours Under Storage Conditions. Applied Sciences. 2026; 16(1):13. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010013

Chicago/Turabian StyleDomiszewski, Zdzisław, Arkadiusz Szpicer, Sylwia Mierzejewska, Iwona Wojtasik-Kalinowska, Weronika Bińkowska, Karolina Maziarz, and Joanna Piepiórka-Stepuk. 2026. "Comparative Study of Lipid Quality from Edible Insect Powders and Selected Cereal Flours Under Storage Conditions" Applied Sciences 16, no. 1: 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010013

APA StyleDomiszewski, Z., Szpicer, A., Mierzejewska, S., Wojtasik-Kalinowska, I., Bińkowska, W., Maziarz, K., & Piepiórka-Stepuk, J. (2026). Comparative Study of Lipid Quality from Edible Insect Powders and Selected Cereal Flours Under Storage Conditions. Applied Sciences, 16(1), 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/app16010013