1. Introduction

Cultural Ecosystem Services (CES) are defined as non-material benefits provided by ecosystems to human societies. These benefits include esthetic appreciation, recreational opportunities, educational value, and spiritual enrichment [

1,

2]. CES are recognized as an essential component of Ecosystem Services (ES). Recently, rapid global urbanization has drawn greater attention to CES. This increased interest arises from their key roles in improving residents’ quality of life, promoting social identity, enhancing psychological health, and facilitating sustainable urban development [

3,

4,

5]. CES have been systematically classified into specific dimensions by internationally accepted frameworks, including the Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES) and the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES). These dimensions typically include esthetic values, recreational functions, educational significance, and spiritual aspects [

6,

7]. Such standardized categorizations provide a theoretical foundation for research on CES. However, accurately assessing the dynamic characteristics, spatial-temporal distribution, and impacts of CES on human well-being remains challenging. This challenge arises from the complexity of social-ecological contexts and requires interdisciplinary collaboration between ecology and social sciences.

In highly urbanized environments, urban parks serve as essential green spaces. They provide diverse ecological services and also reflect urban historical heritage, spatial memory, and social interaction functions [

8,

9]. Macau is characterized by high urbanization and notable cultural diversity. Its urban parks play especially important roles in esthetic, recreational, and educational aspects. These parks also serve as important carriers of local cultural heritage. However, current research on Cultural Ecosystem Services (CES) in Macau’s urban parks remains fragmented. Existing studies mainly employ questionnaires, interviews, and behavioral observations [

10]. These methods are insufficient to comprehensively capture the dynamic characteristics and spatial distribution patterns of cultural services. In the current era of rapid development in information technology and big data, traditional research methods are limited by inadequate data coverage and timeliness. These limitations restrict the systematic quantification and spatial analysis of cultural ecosystem services provided by urban parks.

With the rapid proliferation of social media platforms, user-generated content (UGC) has emerged as a novel data source for CES research [

11]. Social media data comprise text, images, geographical tags, and user comments. These data can reflect public perceptions, preferences, and usage patterns regarding cultural services [

12]. Additional data supporting these results can be found in

Appendix A Figure A1. Compared to traditional data collection methods, social media data offer advantages such as broad coverage, high temporal resolution, and multidimensional characteristics. These advantages provide valuable tools for the dynamic assessment of CES. For example, Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques enable the extraction of emotional expressions and thematic preferences regarding cultural services from public discourse [

13]. Additionally, image analysis techniques can identify user preferences for landscape features and frequently occurring activities [

14]. Furthermore, geographic information technologies can be applied to these data to reveal spatial distribution patterns of cultural services.

Previous studies have demonstrated clear advantages of social media data in revealing public perceptions, usage patterns, and socio-cultural values of CES. For instance, Liang and Zhang [

15] conducted sentiment analysis on images and user comments from the Dianping platform. They explored tourists’ perceptions of cultural services in Shanghai’s urban parks, finding that tourists’ emotional responses closely correlated with park landscape design and spatial arrangement. Similarly, Plunz et al. [

16] and Song et al. [

17] analyzed user-generated data from Twitter and Flickr. They quantified the performance of urban parks in providing cultural services, including esthetics, social interactions, and leisure functions. These studies illustrate that social media data can effectively reflect real-time public perceptions and dynamic changes in cultural services. Thus, they provide valuable data support for urban planning and public space management. Nevertheless, current research has mainly focused on Europe, North America, and mainland China. Studies specifically examining CES in Macau’s urban parks remain relatively scarce.

Macau is a city with a long history and notable cultural diversity. Its urban parks provide significant esthetic, recreational, and educational benefits, and also play a vital role in preserving cultural heritage [

18,

19]. For instance, Lou Lim Ieoc Garden and Monte Fort in Macau are important recreational spaces for residents. These parks also reflect Macau’s distinctive integration of Chinese and Western cultures. However, current research primarily focuses on evaluating ecological functions in urban parks. In comparison, studies addressing cultural services are relatively scarce. Traditional methods, including questionnaire surveys and field observations, are predominantly employed. However, these methods have limitations in comprehensively capturing the dynamic characteristics and spatial distribution patterns of cultural services in parks. Social media platforms serve as important channels for Macau residents and tourists to express their experiences and share perceptions of landscape values. Thus, social media data provide a novel perspective for systematically evaluating CES in Macau’s urban parks.

Therefore, this study aims to establish a quantitative evaluation system of CES based on social media data from a cultural heritage perspective. This system is utilized to systematically assess the characteristics and spatial distribution of cultural ecosystem services in 12 major urban parks on the Macau Peninsula. Natural language processing techniques and spatial analysis methods are combined to extract emotional expressions and spatial characteristics from user-generated content. This approach highlights differences in CES dimensions among Macau’s urban parks and identifies the factors influencing these differences. This study provides scientific support for urban park planning and cultural heritage conservation in Macau. Additionally, it offers a novel theoretical and practical framework for future quantitative CES research.

2. Research Objectives

This study focuses on 12 major urban parks located on the Macau Peninsula. An innovative evaluation framework for Cultural Ecosystem Services (CES) is proposed and developed, integrating social media data with Natural Language Processing (NLP) techniques. Emotional expressions and perceptions of cultural values are analyzed from User-Generated Content (UGC). Based on this analysis, the framework quantitatively evaluates the characteristics and spatial distribution patterns of CES in urban parks, thereby revealing how the public perceives and uses these cultural services. The innovative contributions of this study are reflected in two main aspects:

Methodological innovation: A data-driven analytical approach is adopted, integrating social media data, NLP techniques, and spatial analysis methods. This approach constructs a multidimensional CES evaluation framework specifically suited for urban green spaces. This framework requires no predefined assumptions and can flexibly extract patterns from complex multidimensional data. It systematically identifies emotional characteristics, value distribution, and spatial heterogeneity of CES in Macau’s urban parks, thereby providing a novel perspective for exploring CES dynamics in complex urban environments.

Practical application value: This study provides practical tools and scientific evidence for planning urban green spaces and protecting cultural heritage in Macau. It addresses the research gap regarding CES evaluation in Macau’s parks and serves as a reference model for CES studies in other cities.

Specifically, this study aims to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: How can social media data be employed to quantitatively evaluate CES values in urban parks?

RQ2: Do Macau’s urban parks show significant differences across various CES dimensions?

RQ3: How do users’ emotional evaluations of CES reflect their spatial distribution characteristics and usage preferences?

A CES evaluation framework was developed based on social media data. This framework incorporated analyses of emotional expressions and perceived cultural values extracted from user-generated content (UGC). Additionally, spatial analytical methods were applied to quantitatively explore the spatial characteristics of CES within Macau’s urban parks. This approach fills existing research gaps in assessing CES in Macau’s urban parks. Furthermore, it provides scientific evidence for urban green space planning and cultural heritage conservation.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Design

The research was conducted in five steps, which aimed to analyze evaluations of CES in Macau’s urban parks using social media data (

Figure 1). First, image and text data were collected from social media platforms using web-crawling techniques. These data provided visual representations of users’ perceptions and evaluations regarding the park environment. Second, the collected texts were analyzed to identify and quantify key CES elements; this analysis was then used to establish a CES indicator framework. Third, a sentiment analysis of user-generated textual data was conducted using natural language processing (NLP) techniques. This analysis accurately captured users’ satisfaction with CES in Macau’s urban parks. Fourth, cluster analysis and multiple regression analysis were performed on the collected data using SPSS 27 software. Fifth, spatial analysis techniques were applied to visually illustrate the spatial distribution patterns of CES evaluations across different park locations.

3.2. Study Area

Urban parks on the Macau Peninsula, located in the Macau Special Administrative Region of China, were selected as the study area. This choice was primarily due to their unique position and significant role within a highly urbanized context. Macau is located on the west bank of the Pearl River Delta along China’s southeastern coast. It borders Zhuhai city in Guangdong Province and faces Hong Kong to the east, providing Macau with a favorable geographic location. Macau experiences a subtropical monsoon climate with distinct seasons. The annual average temperature is approximately 22 °C, with abundant rainfall and relatively high humidity. This climatic condition provides a suitable ecological environment for green spaces in Macau. The Macau Peninsula is one of the world’s most densely populated regions with limited green space resources. Urban parks, however, serve as open spaces that significantly enhance ecological quality and residents’ well-being, as well as providing rich cultural ecosystem services (CES). Macau’s urban parks integrate Chinese and Western cultural elements with natural landscapes. They possess significant cultural heritage value and attract diverse user groups, including local residents and international tourists. Thus, these parks provide abundant multidimensional data for studying user perceptions and CES functions. Within Macau’s sustainable development framework, enhancing the planning and management of urban green spaces has become a policy priority. Therefore, the selection of urban parks on the Macau Peninsula as the research area has important scientific significance and practical value (

Figure 2).

3.3. Data Sources and Processing

The cultural ecosystem services (CES) of Macau’s urban parks were evaluated through the analysis of user-generated content (UGC) from social media platforms. Data were obtained from the following two prominent applications listed under the “Navigation” and “Travel” categories in Macau’s Apple Store: Google Maps and TripAdvisor. These platforms are frequently used for travel guidance and location evaluation. They provide abundant and structured user-generated data, including park-related comments, ratings, and associated information. Information about urban parks on the Macau Peninsula was sourced from OpenStreetMap

https://www.openstreetmap.org (accessed on 20 December 2024). Evaluation data, including usernames, review dates, ratings (1–5 stars), and textual comments, were extracted using Octoparse software 8. To ensure data representativeness, 12 parks with a substantial number of reviews (N > 100) and high visitation indices (index > 1.5) were selected for detailed analysis. These parks provided extensive data, enabling a more accurate analysis of user perceptions and preferences towards park CES (

Figure 3).

3.3.1. Data Screening

User-generated content (UGC) was collected from 12 urban parks in Macau between 2020 and 2024, resulting in over 26,000 valid text entries. As the collected data involved multiple languages, all texts were initially translated using the online version of Google Translate, accessed on 30 December 2024. Subsequently, manual proofreading was performed to enhance translation accuracy and ensure contextual appropriateness. Subsequently, the data underwent rigorous screening. First, comments unrelated to cultural ecosystem services (CES), such as those about transportation or dining, were removed. Second, duplicate entries, irrelevant content, and promotional comments were excluded to improve data quality and relevance. Additionally, textual data were preprocessed by removing special symbols, formatting tags, and meaningless characters. This step was conducted to further clean the data and ensure consistency in data formatting. Finally, the screened texts were classified systematically to ensure the accuracy and reliability of this study’s findings.

3.3.2. Data Processing

Word Segmentation and High-Frequency Word Extraction. In contrast to English texts, which are naturally separated by spaces, Chinese texts require word segmentation prior to textual analysis. In this study, the Python 3.12-based third-party tool “Jieba” was selected for Chinese word segmentation, as it exhibits high speed, efficiency, and accuracy in processing large-scale textual data. Each comment was segmented into individual lexical units using Jieba. Words that were unrelated to the research topic or lacked clear relevance were removed. Subsequently, high-frequency words occurring more than five times across all comments were extracted to support further analysis.

Construction of the Dictionary Framework. The dictionary framework was established based on core concepts from the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment (MEA) [

1] and The Economics of Ecosystems and Biodiversity (TEEB) [

2], described in

Section 1. Additionally, detailed classifications from the Common International Classification of Ecosystem Services (CICES V5.1) [

20] were utilized. Additionally, recent studies in the field of urban green space (UGS), such as those conducted by Havinga et al. [

21], Xin et al. [

22], and Wang et al. [

5] were incorporated into the framework. Based on this framework, six evaluation dimensions of CES for urban parks were clearly defined (

Table 1).

Matching of Perception Vocabulary. A research team consisting of five experienced researchers was formed. The team was tasked with scientifically classifying high-frequency vocabulary according to the previously established CES framework. Statistical analysis and vocabulary screening were systematically performed. Multiple rounds of evaluation and feedback were conducted. Ambiguous or unclear terms were carefully reviewed and reclassified by the research team until a consensus was reached. Ultimately, these classification results were directly applied to the construction of a perception vocabulary dictionary for the CES of urban parks. Specifically, the CES dictionary contained 110 key terms, thereby providing a reliable basis for subsequent detailed research.

3.4. Sentiment Analysis

Advanced natural language processing (NLP) techniques were applied in this study to accurately identify emotional content in text. This approach provided a basis for subsequent quantitative analysis. The sentiment analysis algorithm integrated into the Baidu Intelligent Cloud API platform

https://cloud.baidu.com (accessed on 4 February 2025) was employed. This algorithm efficiently analyzes large-scale textual data and generates highly accurate sentiment scores. The calculation formula is as follows:

where f(w

i) represents the frequency of word w

i, reflecting its importance; s(w

i) denotes the sentiment value of word w

i, reflecting its emotional orientation; and is the total frequency of all words within a given dimension. It serves as a normalization factor, ensuring that sentiment scores are not influenced by variations in total word frequency.

Sentiment scores were calculated on a scale ranging from 0 to 100, representing sentiment intensity. This scoring range enables clear comparisons of sentiment intensity across different comments. Additionally, multiple random sampling validations were conducted (with 300 comments drawn in each sampling) to minimize bias introduced by single sampling. Consistency tests were performed to verify the stability of the results. The validation results indicated high stability in sentiment analysis performed by Baidu Intelligent Cloud. This demonstrates its suitability for large-scale data analysis.

3.5. Multiple Linear Regression Model

The overall CES sentiment score in urban parks may be influenced by multiple CES categories. Thus, a multiple linear regression model was employed to examine the effects of each CES category on the overall sentiment score. PSS 27 software was utilized to verify the fundamental assumptions of the regression model. These assumptions included tests for residual independence, normality of distribution, and multicollinearity, which were essential for ensuring the accuracy and validity of the regression model. Subsequently, multiple linear regression analysis was performed, with the six CES categories as independent variables and the overall sentiment score as the dependent variable. The aim was to clearly determine the specific contribution of each CES category to the overall sentiment score. Finally, the results of the regression model were interpreted. These results provided empirical support for understanding the complexity of CES sentiment composition in urban parks and identifying potential strategies for optimization.

3.6. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis

In this study, spatial autocorrelation analysis was performed using ArcGIS pro software to investigate the spatial distribution characteristics of CES in urban parks in Macau. The analysis aimed to identify spatial patterns within CES evaluation data. Specifically, spatial relationships among urban parks were assessed across various CES dimensions. Specifically, Z-scores were calculated to detect significant clustering or dispersion among urban parks. Spatial analysis tools were applied to clearly identify distribution patterns of CES dimensions among urban parks. The results provided empirical support for park management optimization.

4. Results

4.1. Word Frequency and Sentiment Scores

According to the integrated analysis of word frequencies and sentiment scores across six CES dimensions in 12 urban parks in Macau (

Table 2), higher word frequencies were observed for “landscape experience” (0.29) and “education and knowledge dissemination” (0.20). This result indicates visitors’ strong interest in the natural landscapes and cultural functions of urban parks. In contrast, relatively low frequencies were found for “cultural services” (0.08) and “aesthetic appreciation” (0.13). This finding suggests that these dimensions receive less attention in social media discussions. A further analysis of the sentiment scores was conducted to clarify visitors’ emotional tendencies toward each CES dimension. Higher sentiment scores were obtained for “aesthetic appreciation” (76.04) and “landscape experience” (72.47), suggesting positive visitor evaluations regarding parks’ natural scenery and recreational functions. In contrast, relatively lower sentiment scores were recorded for “public facilities” (62.77) and “education and knowledge dissemination” (57.38). These scores indicate moderate visitor satisfaction with these services. In particular, visitors expressed neutral sentiment regarding education-related services, which may reflect insufficient development or utilization.

The results indicated relatively high evaluations for cultural ecosystem services associated with “recreation and tourism” and “landscape experience”. These findings suggest that natural landscapes and recreational experiences represent primary motivations for park visitation in Macau. However, despite relatively high word frequencies, lower sentiment scores were observed for “public facilities” and “education and knowledge dissemination”. This finding suggests relatively negative or unsatisfactory visitor evaluations of these services. Notably, although “social interaction” exhibited low word frequency (0.08), a relatively high sentiment score (71.35) was recorded. This result indicates that some visitors positively recognized the cultural significance of urban parks.

4.2. Influence of CES Categories on Visitor Sentiment

According to the regression analysis results (

Table 3 and

Table 4), the coefficient of determination (R

2) was 0.96. This indicates a strong goodness-of-fit for the model. The adjusted R

2 was 0.91, showing a slight decrease compared to the original R² value. This result suggests limited contributions from some independent variables to the model. The standard error of the estimate was 2.64, indicating a relatively small average discrepancy between predicted and observed values. The Durbin–Watson statistic was 2.02, which is close to the optimal value of 2. This finding implies no significant autocorrelation among the residuals. This result further supports the validity of the regression model. Additionally, the ANOVA results (F = 19.45,

p = 0.003) indicated that the overall regression model was statistically significant. This demonstrates that the independent variables significantly accounted for the variation in the dependent variable.

The results (

Table 5) indicated that “landscape experience” (B = 0.95,

p = 0.006) and “social interaction” (B = 0.83,

p = 0.01) had significant positive effects on visitors’ overall evaluations. These findings suggest that both factors played essential roles in enhancing visitors’ overall experiences and satisfaction. In particular, “landscape experience” showed a notably high standardized coefficient (Beta = 0.83), underscoring the critical role of natural environment and scenic quality in visitor experience. Conversely, “public facilities” (B = −0.59,

p = 0.01) demonstrated a significant negative effect on the overall score. This result indicates that inadequate or poorly maintained public facilities might significantly reduce visitors’ overall satisfaction. Therefore, it is suggested that park managers pay attention to optimizing and maintaining these facilities to enhance the visitor experience. However, other independent variables, including “recreation and tourism” (

p = 0.12), “aesthetic appreciation” (

p = 0.51), and “education and knowledge dissemination” (

p = 0.63), did not show statistically significant effects on the overall evaluation. This indicates limited contributions of these factors in the current regression model. These findings may reflect that visitors’ needs in these aspects have not yet been adequately addressed.

4.3. Comparative Evaluation of CES in Macau Parks

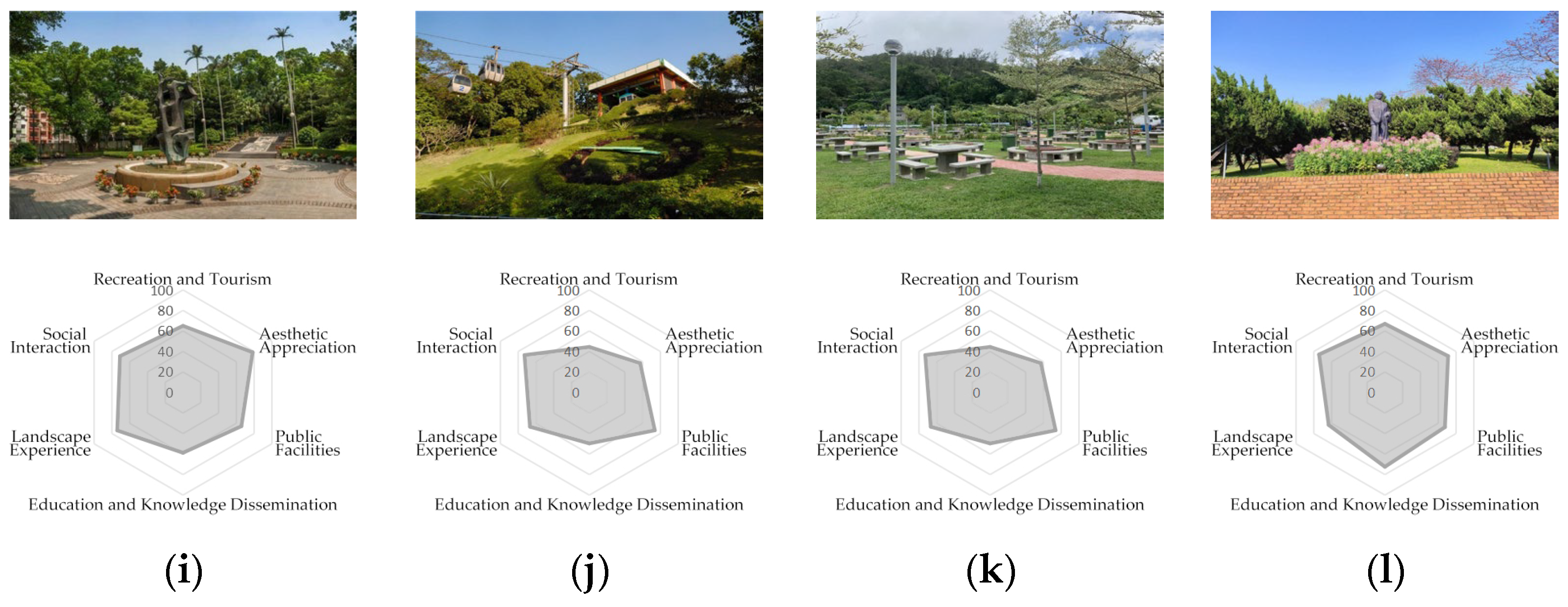

Significant differences were observed in the performance of cultural ecosystem services (CES) between Macau parks, as shown in

Figure 4. These differences were associated not only with parks’ functional positioning and facility development but also with their cultural heritage backgrounds. In terms of overall scores, Montanha Russa Municipal Park (78.82) and Lou Lim Ioc Park (73.94) had notably high scores; in contrast, Monte Fort Park (51.78) and Hac Sa Van Park (52.78) had relatively low scores. Montanha Russa Municipal Park, Lou Lim Ioc Park, and Monte Fort Park are important components of the UNESCO World Heritage site “Historic Centre of Macau”. Their cultural heritage backgrounds were found to significantly enhance performance in esthetic appreciation and landscape experiences. Montanha Russa Municipal Park (esthetic appreciation: 90; landscape experience: 80) and Lou Lim Ioc Park (esthetic appreciation: 84.3; landscape experience: 77.57) exhibited particularly strong performances in these two dimensions. This finding reflects their advantages in historical and cultural significance, as well as scenic attractiveness. However, Monte Fort Park received the lowest overall score, particularly exhibiting poor performance in “aesthetic appreciation” (54.71) and “public facilities” (50). This result may be related to inadequate facility construction and insufficient cultural interpretation services. In comparison, parks outside the historic district, such as Hac Sa Van Park and Dr. Sun Yat Sen Municipal Park, were found to emphasize daily functional services. These parks received higher scores in “public facilities” (73.67 and 67.48, respectively), but relatively lower scores in “aesthetic appreciation” and “landscape experience”. This indicates that cultural heritage backgrounds play an important role in enhancing the esthetic value and cultural depth of parks. In contrast, non-heritage parks were observed to prioritize daily usage needs. In summary, CES performance in Macau parks was significantly influenced by their cultural heritage backgrounds. Parks located within historic districts generally performed better within the esthetic appreciation and landscape experiences dimensions. However, significant differences were found between parks, indicating the important influence of facilities and management strategies on CES performance.

4.4. Spatial Autocorrelation Analysis of CES

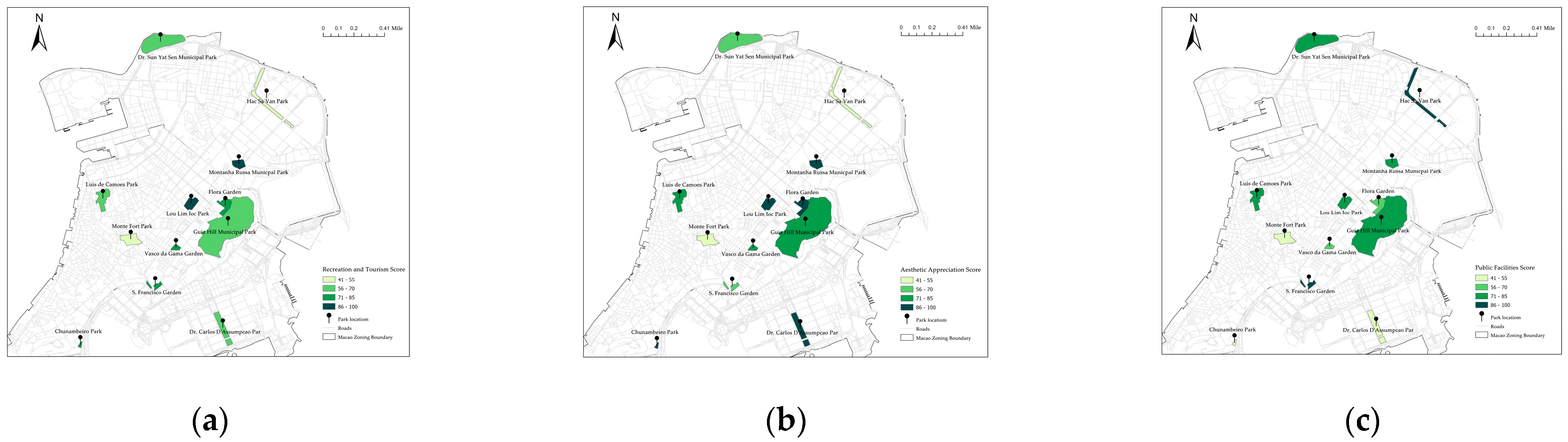

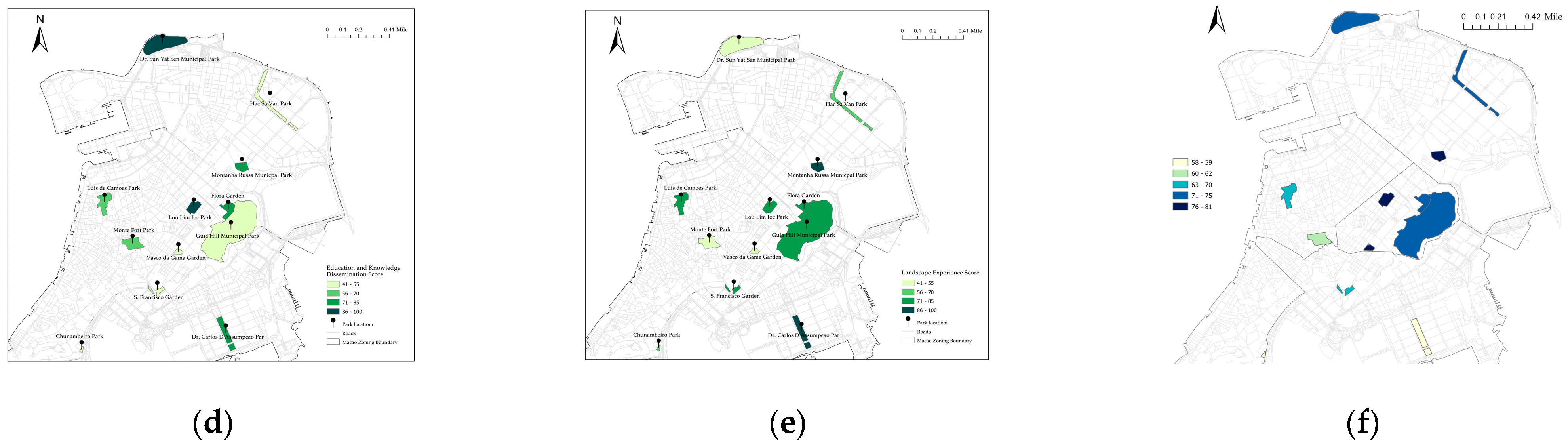

The results from the spatial autocorrelation analysis (

Figure 5) indicated no statistically significant difference between the spatial distribution of CES in parks and a random distribution pattern (Moran’s I = 0.018, Z = 0.59). Additional data supporting these results can be found in

Appendix A Table A2. This result suggested that the CES distribution across Macau parks lacked significant spatial clustering or dispersion, displaying characteristics of a random distribution. This finding was closely related to the urban spatial structure of Macau. Park layouts were influenced by geographical constraints and land-use planning, resulting in the absence of high-value clusters or distinct regional groupings. Although differences were identified between parks in multiple CES dimensions, these variations did not appear directly associated with their geographical locations or spatial configurations. The distribution of CES in Macau parks might be influenced by multiple factors, such as park size, park content, and surrounding socioeconomic contexts. Interactions among these factors might partially mask potential spatial clustering patterns of cultural services. Therefore, further research is recommended to explore how visitor experiences could be enhanced by optimizing the functional layouts and landscape designs of parks.

5. Discussion

5.1. Potential and Limitations of Social Media Data in Quantitative Assessment of Cultural Heritage Ecosystem Services

This study quantitatively assessed the cultural ecosystem services (CES) of urban parks in Macau from a cultural heritage perspective. Social media data were analyzed using natural language processing (NLP) and multimedia interaction analysis techniques. The results indicated that social media data had significant potential for capturing user perceptions and sentiment evaluations regarding cultural services in parks. Particularly strong potential was observed in explicit cultural services, such as esthetic appreciation and landscape experiences. This finding is consistent with Hausmann et al. [

23], who confirmed the effectiveness of social media data in CES research. Through analysis of user-generated content (UGC), this study dynamically captured the diversity and emotional variations in user experiences. Consequently, an innovative methodological approach was provided for the quantitative assessment of cultural services.

5.2. Differences Between Cultural Service Dimensions in Parks and Directions for Optimization

Significant differences were found between the various cultural service dimensions in major urban parks in Macau (F = 19.45,

p < 0.01). Esthetic appreciation (M = 76.04) and landscape experience (M = 72.47), which were identified as core dimensions of cultural services in Macau parks, received significantly higher scores compared to other dimensions. Parks with high scores, such as Song Yusheng Park and Guia Hill Park, effectively integrate natural landscapes with cultural heritage elements. This integration provides strong visual appeal and emotional resonance, significantly improving visitor satisfaction. Guia Hill Park achieved excellent scores in esthetic services (M = 90) and landscape experiences (M = 80). These results demonstrate a deep integration between cultural and natural elements. Mount Fortress Park and Vasco da Gama Garden received relatively low scores for landscape experience (M = 61.18 and M = 59.26, respectively). These results indicate that their cultural heritage potential has not been fully explored. The primary reasons for these low scores may include insufficient interactive design and a lack of cultural interpretation methods. This finding indicated that Macau parks performed well in enhancing users’ visual satisfaction and emotional connection. By effectively integrating natural landscapes with Chinese and Western cultural elements, parks demonstrate considerable potential as carriers of cultural heritage. This result is consistent with the findings of Huai and Van de Voorde [

24], who emphasized the importance of esthetic value in green spaces.

However, park performances in the educational and cultural dimensions of CES were relatively weak. This weakness could reflect deficiencies in exploring cultural content and designing educational functions within Macau parks. For example, explicit facilities and activities related to local culture, such as historical exhibitions and ecological education programs, were found to be relatively scarce in Macau parks. These shortcomings were observed to limit the role of parks as media for cultural heritage dissemination, weakening their competitiveness in providing diversified services. Therefore, it is suggested that multimedia interaction technologies be employed to strengthen parks’ performances in cultural transmission and educational services. These technologies could include virtual tours, digital displays, and interactive educational platforms, thereby enriching user experiences and enhancing participation in cultural services.

Significant differences exist among major urban parks in Macau in terms of CES. These differences may result from multiple influencing factors. First, uneven distribution of cultural heritage resources is a critical factor. Parks with abundant historical and cultural resources, such as Guia Hill Park and Lou Lim Ieoc Garden, perform well in esthetic services and landscape experiences. In contrast, Areia Preta Park in peripheral areas exhibits weaker performance in cultural and educational functions due to resource scarcity. Second, differences in facilities and management resources significantly affect the provision of cultural services. Song Yusheng Park, located in the central urban area, achieves strong performance across multiple CES dimensions due to adequate facilities and sufficient management resources. Conversely, limited investment in management resources in peripheral parks restricts their capacity for cultural dissemination. Additionally, disparities in visitor behavior patterns further intensify this imbalance. Parks located in central urban areas benefit from high visitation rates and diverse activity demands, enhancing visitors’ perceptions of cultural services. Conversely, peripheral parks, characterized by lower visitation rates, tend to have their cultural service functions underestimated. These multidimensional factors collectively contribute to differences in cultural services among Macau’s urban parks. In the future, spatial heterogeneity and diversity in cultural service expression could be enhanced through optimization of resource allocation, facility improvements, and cultural function design.

5.3. Spatial Distribution of Park Cultural Services and Factors Influencing Users’ Sentiment Evaluation

The spatial autocorrelation analysis (Z = 0.59) indicated no significant spatial clustering in the supply of cultural ecosystem services (CES) between the 12 major urban parks on the Macau Peninsula. This finding suggests that, although urban parks in Macau are geographically distributed relatively evenly, variations in cultural service quality are primarily determined by their functional positioning, landscape design, and service content rather than spatial location. Compared with the findings of Richards and Friess [

25] regarding the distribution characteristics of cultural services in urban green spaces, cultural services provided by Macau’s urban parks show a certain degree of homogeneity. This homogeneity is particularly evident in the limited provision of cultural education and heritage-related functions, leading to relatively weak individualized service characteristics among parks. Service homogeneity not only limits the potential of urban parks to meet diverse cultural demands but also weakens Macau’s ability to express cultural diversity as a city renowned for its heritage. To address these limitations, multimedia interactive technologies could be introduced in the future. Examples include virtual tours, digital exhibitions, and immersive educational projects. Integrating these technologies within Macau’s cultural heritage context would enable each park to develop a more distinctive cultural service theme.

The sentiment analysis further revealed that esthetic appreciation and landscape experience were the primary factors influencing users’ sentiment evaluations (β = 0.95,

p < 0.01). Landscape design and high vegetation coverage in Macau’s urban parks significantly enhanced users’ visual satisfaction and emotional connections. This result is consistent with findings by Li [

26] on how the esthetic value of green spaces influences user sentiment. However, user comments indicated that insufficient facility maintenance and overcrowding negatively affected sentiment experiences. Notably, more abstract CES dimensions, such as cultural heritage and educational services, showed relatively weak effects on sentiment evaluations [

27]. This result reflected an insufficient explicit representation of these dimensions in Macau parks. Therefore, the introduction of virtual reality technologies and interactive cultural experience activities [

23] is suggested to further enhance users’ perceptions and emotional connections with cultural services.

6. Conclusions

This study conducted a systematic evaluation of cultural ecosystem services (CES) provided by 12 major urban parks on the Macau Peninsula. Social media data were analyzed by integrating natural language processing (NLP), multimedia interaction techniques, and spatial analysis methods. Firstly, the effectiveness of social media data in quantitatively assessing cultural heritage ecosystem services was verified. Social media data successfully captured users’ sentiment evaluations and perceptions regarding explicit services, such as esthetic appreciation and landscape experiences. Secondly, Macau parks performed well in dimensions of esthetic appreciation and landscape experience. However, their performance was relatively weak in science education and cultural heritage functions. This deficiency limited the role of Macau parks as media for cultural heritage dissemination. To address this limitation, it is suggested that multimedia interaction techniques, such as virtual tours, interactive educational displays, and digital cultural experiences, be employed. These measures could enhance cultural expression and educational functions, diversify park services, and improve user engagement in the future. Finally, cultural services provided by Macau parks did not exhibit significant spatial clustering. Differences in service quality were primarily driven by park design and functional positioning rather than geographic location. The sentiment evaluation analysis indicated that esthetic appreciation and landscape experiences were primary factors influencing users’ emotional connections with the parks. In contrast, insufficient explicit expression of cultural heritage and educational functions resulted in weaker user perceptions of these dimensions. Therefore, it is recommended that multimedia interactive cultural experience activities be introduced to effectively enhance users’ perceptions and emotional connections with cultural heritage ecosystem services.

Based on the findings of this study, several recommendations are proposed to address existing deficiencies in cultural heritage ecosystem services (CES) provided by Macau urban parks. Firstly, Macau’s unique historical and cultural resources should be fully explored. Cultural landscape designs, historical narrative exhibitions, and local cultural symbols could be integrated into park planning. These measures would strengthen heritage transmission functions, thereby enhancing cultural value and user identification with parks. Secondly, to enhance user experiences, multimedia interactive technologies are recommended. These include virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), and digital guided tours, which could enrich cultural service presentations and increase their interactivity and attractiveness. Additionally, in response to user concerns regarding insufficient facility maintenance and overcrowding, it is suggested that facility layouts and spatial management be optimized. Interactive spaces should be rationally configured, and dynamic crowd control measures implemented, to maintain high standards of service quality and efficiency despite high visitor numbers. Furthermore, it is recommended that the educational functions of parks be expanded. Ecological exhibition paths, interactive educational activities, and digital science content could be added to enhance public awareness of cultural heritage and ecological conservation. These optimization measures are applicable not only to improving cultural services in Macau urban parks but also offer practical references for green space management and cultural heritage conservation in other highly urbanized regions globally.

Although this study provided a comprehensive evaluation of cultural heritage ecosystem services in Macau’s urban parks using social media data mining and multimedia interactive evaluation techniques, certain limitations remain. First, the representativeness of social media data is limited. Experiences of elderly users and infrequent visitors may therefore be underestimated, leading to biases in the coverage of different population groups. Second, the specific roles of urban facilities within parks (such as benches, walkways, and lighting) were not deeply examined. These facilities significantly influence park esthetics, functionality, and visitor experiences. Due to limitations in research scope, comprehensive analyses of their contributions to cultural services were not conducted. Finally, the unstructured characteristics of textual data and existing limitations in sentiment analysis techniques restrict the in-depth analysis of intangible cultural services (such as inspiration and sense of place). Additionally, these limitations hinder the comprehensive capture of users’ complex emotions and deeper cultural value perceptions.

To address the limitations identified in this study, future research could be enhanced in the following three aspects. First, field surveys, questionnaires, and sensor data could be integrated to address the limited representativeness of social media data. This integration would enable a more comprehensive understanding of cultural service perceptions across diverse population groups. Second, future studies should focus on specific park facilities, such as benches, walkways, and lighting. Quantitative analyses and user behavior tracking methods could be employed to evaluate the effects of these facilities on cultural service provision, thereby improving research precision. Finally, advanced natural language processing techniques and multimodal sentiment analysis models could be introduced to analyze complex emotions and deeper cultural values embedded in unstructured textual data. Additionally, integrating time-series data could help reveal dynamic changes in cultural services and their underlying driving mechanisms.