1. Introduction

Regular physical activity (PA) can improve women’s mental health and help avoid or delay the onset of osteoporosis and sarcopenia, which contribute to frailty in older age and are leading causes of women requiring social care [

1,

2,

3]. Crucially for women, regular PA participation has also been shown to prevent or delay the onset of dementia, Alzheimer’s, and cardiovascular disease [

4,

5]. Disease risk increases significantly in women during midlife and post-menopause [

6,

7] and having a regular PA routine in midlife can delay the onset of disability by up to 15 years [

8]. However, despite the robust evidence illustrating the efficacy of PA for reducing disease risk, women continue to participate in less PA than men, and participation rates continue to decline with age [

9]. Therefore, it is important to help support women in overcoming the barriers which prevent PA participation entirely, or the formation of PA as a habit.

Many PA interventions have focused on increasing women’s PA by targeting the most often reported barriers to participation, such as a lack of time due to family commitments [

10]. However, few interventions consider urinary incontinence (UI) and how it impacts a woman’s ability to be physically active. UI is any involuntary loss of urine from the bladder [

11] and is more commonly experienced by women compared to men [

12]. The prevalence rate of UI has been reported to be as high as 70% [

13,

14], and a number of treatments for individuals have been developed, including, for example, pelvic floor muscle training [

15]. However, the number of women seeking help for UI symptoms remains low. For example, in the UK, studies have shown that between 17 and 33% of women have sought help associated with UI [

16,

17]. Southall et al. [

18] attribute the low levels of UI help-seeking by women to feelings of shame and fear of public stigma. Research has calculated the average delay between symptom onset and seeking help to be almost 7 years [

19].

In a qualitative study exploring help-seeking behaviour, Fakari et al. [

20] reported that when help-seeking does occur, there is a delay from the onset of symptoms to the symptoms being raised as an issue with a healthcare professional due to women perceiving UI as a “natural process” and “normal”, particularly as they age. These findings have previously been reported in the literature; for example, a 2008 study found that 43% of their participants aged 30–44 years also believed UI to be “part of being female” and something to put up with [

21] and similar findings were reported by Peake, Manderson, and Potts [

22] in their earlier study, where they observed that women were reluctant to discuss UI with their doctor, believing UI to be non-medical and something their doctor would, therefore, not allow them time to discuss.

A recent 2024 review indicated women’s perceptions of UI and their attitudes to help-seeking have changed little over time; women continue to believe UI symptoms are a normal outcome of childbirth and ageing and are, therefore, to be expected, and that primary healthcare practitioners do not take their symptoms seriously or are too busy to disturb with such a ‘trivial’ matter [

23]. It can be deduced from the availability of these findings, that UI prevalence statistics may fail to capture data for women who have yet to seek help for their UI symptoms. While the extant research suggests some reasons why women may avoid raising concerns regarding UI in the clinical setting, it remains unknown whether this behaviour continues in the PA setting, particularly when gathering data on barriers.

UI, especially stress urinary incontinence (SUI), is common in physically active women and is estimated to affect up to 50% of women who exercise regularly [

24]. SUI during PA is generally attributed to decreased pelvic floor support resulting from increased intra-abdominal pressure during high-impact moves (such as jumping or running), and women experiencing UI may cease PA entirely or alter the mode, intensity or frequency of exercise being undertaken [

25]. Whilst vigorous-intensity PA may increase SUI risk [

26], several studies have reported long-term mild to moderate-intensity PA, including walking, can reduce the severity of UI symptoms or reduce the risk of UI developing [

27,

28,

29], suggesting that interventions utilising mild to moderate intensity PA may be useful for influencing PA behaviours in women with UI. However, women with UI are often forced to withdraw from their preferred mode of PA due to UI symptoms, which can negatively impact enjoyment and motivation [

30].

Enjoyment has been well-documented as a predictor of PA participation [

31]. For example, Philips et al. [

32] found intrinsic rewards, including enjoyment, promoted the intention to be physically active in pre-intenders, i.e., those who have not yet formed the intention to exercise. For individuals already participating in regular PA—i.e., ‘actors’, enjoyment facilitates habit-forming, which is crucial for long-term PA adherence [

32]. For those risk-averse women who withdraw from PA entirely, providing a modified version of their preferred PA mode, which minimises urine leakage and/or supports the management of UI during exercise, may provide women with the confidence to re-engage in PA. Women who have managed their UI during PA by changing the mode of PA they participate in may also be encouraged to return to their preferred PA mode if a modified version is offered, helping to maintain PA enjoyment, and aiding the formation of PA as a habit [

33].

There is a risk that participants will withdraw from group-based physical activity (PA), and subsequently reduce their enjoyment and motivation to stay active due to concerns about leaking in front of others in group-based PA. The literature supports this, indicating that UI contributes to disengagement from group-based PA [

30]. However, research also shows that group interventions targeting women with UI are well-received. For instance, a study on a group-based PA intervention for overweight women with UI found that the group dynamic was a critical factor in motivating participants and contributing to the intervention’s success [

34]. Physical activity-based studies in the general population have also found that women particularly enjoy the social aspect of group PA, valuing the opportunity to make social connections and create friendships, which reduce the feeling of social isolation and loneliness [

35]. Loneliness and a loss of social connectedness can increase the risk of heart disease and physical inactivity in older age [

36], and loneliness has been reported as a risk factor for dementia and Alzheimer’s disease [

37], making interventions reducing the risk of loneliness and social exclusion important factors to target for long-term health. Although people in older age are the most likely to experience loneliness and social isolation, and these are known to have significant impacts on health and quality of life, it has been suggested that interventions providing opportunities which create and nurture social relationships during midlife may reduce loneliness and social exclusion, and lessen the resulting health decline, in older age [

38].

Physical activity motivation through the social aspect of group exercise has been well-studied in older adults, but midlife studies appear scant; however, Spiteri et al. [

39] found that participants in both their midlife and “young-old” PA groups reported being motivated by social factors, but the young-old group did so more often. Another study examined links between social exclusion, loneliness, and physical inactivity in midlife adults and discovered that social exclusion, but not loneliness, was associated with participants in this life stage who were inactive [

38]. Having the opportunity to socialise during PA can foster a sense of shared identity and belonging to the PA group, and these have been linked to regular PA attendance and long-term adherence [

39,

40]. However, the opportunity to socialise may not be enough on its own to foster a sense of identity within a group, as demonstrated by several studies which found participants formed a stronger identity with and preferred to exercise in groups with others with whom they shared similar characteristics, such as having the same fitness level, age or sex [

41,

42]. Research has shown that older adults related more to single-sex groups, which then fostered group members’ feelings of group belonging [

43]; however, exercising with people of a similar age was a stronger predictor of group identity and PA adherence. For women who experience UI during PA, the sex of fellow exercisers may carry more significance than is reported for the general population, given that age appears rarely cited in the UI literature in this context, but, of the limited studies available exploring PA behaviours in those experiencing UI, withdrawal from group PA is suggested to be more likely for women with UI if the PA group consists of mixed-sex members [

44].

While there is little in the literature to indicate the preferences of women with UI for exercising in a group with members of a similar age, some participants expressed feeling uncomfortable undertaking PA when they perceived the group instructor to be much younger than themselves. Group PA instructors have been shown to play an important role in participant enjoyment and group identity formation, particularly where the instructor engages in group identity leadership by sharing the characteristics of the group and actively promoting a sense of “we” and “us” amongst group members [

45,

46]. For example, Stevens et al. [

46] reported group members where the group instructor was perceived to be engaging in identity leadership were more likely to attend the exercise class the following week, suggesting the characteristics of a group PA instructor may need careful consideration alongside those of the group members when designing targeted group-based PA interventions. For many women, a much younger group PA instructor was expected to have little knowledge of the impact of UI on women’s ability to perform certain exercises, nor to understand UI’s impact on women’s motivation or confidence to participate in PA. The issue of a lack of disease-specific knowledge has been reported by several studies exploring the role of PA instructors in group PA interventions where participants have chronic conditions. One study investigating factors which influence PA in adults with arthritis found that an instructor with first-hand knowledge of the disease was important to the participants’ confidence [

47]. Similarly, 82% of participants in another study exploring the factors which affect the PA participation of people with physical disabilities reported that participants thought it important that instructors understood their disability and how to adapt exercises accordingly [

48]. Instructors who lack the understanding of chronic disease and how symptoms impact PA participation, and instructors who do not possess the ability to modify exercises accordingly have been reported as a barrier to group PA and a reason to cease participation [

49,

50,

51]. Additionally, when groups consist of members who share the same chronic conditions, a stronger sense of group identity is formed, and PA adherence is positively impacted [

52]. This may be a particularly salient point when promoting PA to women with UI, as women in this population have reported feeling alone and socially isolated in their experiences [

53,

54], and it may be that encouraging participation in group-based PA alongside other women who experience UI could help build confidence and a stronger sense of belonging to the PA group.

The growing body of evidence suggests UI is an overlooked but significant barrier to women’s PA, usually resulting in women having to withdraw from their preferred mode, or from all modes, of PA [

30]. Group-based PA has been noted as a mode of PA that women find both enjoyable and rewarding, particularly due to the social opportunity group-based PA fosters; however, as discussed, it is also a mode from which women are likely to withdraw if they experience UI, due to the stigma and fear of leaking in front of others [

30,

53]. Understanding how women’s preferred modes of PA can be suitably modified to help minimise UI risk would seem prudent, especially given the importance of enjoyment and social inclusion in forming motivation and habitual PA adherence and the long-term effects these have on older age. Whilst many PA interventions are aimed directly at older women, promoting PA and developing PA as a habit in midlife women could be particularly beneficial as the risk associated with many of the chronic diseases which burden women increases with the onset of menopause [

6]. Social isolation, but not loneliness, appears to be a particularly useful factor to include in midlife PA interventions; Baumbach et al. [

38] suggest loneliness may be less of an issue in midlife due to this age group often reporting family commitments and pressures as a reason for physical inactivity and, as a result, familial relationships may negate feelings of loneliness but not those of social exclusion in midlife women. Family commitments are well known to be the reason midlife women are more likely to report “being busy” as a barrier to PA [

39]; therefore, it may be that a group-based PA intervention which allows opportunities to socialise could present women with a ‘time-saving’ opportunity by combining PA and social needs, increasing the attractiveness of such an intervention to women who experience UI during PA and encouraging the attendance and building of habitual PA.

No studies to date have examined the modification of individual design elements of a group-based PA intervention aimed at engaging women with UI or explored women with UI’s perception of modifications made to a group-based PA intervention. It is, therefore, the intention of the current study to modify a ‘standard’ dance-based group PA class using the evidence discussed above and to understand women’s perceptions of the modifications made as well as their willingness to participate in a similarly designed PA class in the future. This study also sought to understand how the advertising of group exercise could be improved to encourage and improve PA participation in women who experience UI during PA. Therefore, this research aims to answer the following research question: does a tailored ‘pelvic-floor friendly’ group exercise class help increase PA participation in women with UI? Specifically, the study aims to:

Determine if a ‘pelvic-floor friendly’ group exercise class can influence the motivation or intent of women with UI to participate in PA;

Explore women with UI’s perceptions and feelings towards the design elements of a ‘pelvic-floor friendly’ group exercise class, including when combined with access to a women’s specialist pelvic health physiotherapist;

Provide insight into the advertising of exercise programmes targeting women and how advertisements are perceived by women who experience UI when exercising.

2. Materials and Methods

A mixed-method research design was used in this study to explore the feelings and perceptions of women who experience urinary incontinence during physical activity. The subsections below outline the ethics, research design, sampling, procedures, measures, and data analysis for the study.

2.1. Study Design

This study utilised a parallel mixed-method design to collect and analyse data. Mixed methods research is defined as an approach to gathering both qualitative and quantitative data in a singular study, to gain greater insight than that afforded by using either of these methods alone [

55]. The convergent parallel mixed-method design was chosen for this study, as a single-phase approach allows for both the quantitative and qualitative data to be gathered and analysed separately, before merging during interpretation and discussion [

56].

2.2. Participants

Recruitment took place both online via social media advertising (i.e., Linked-In, Twitter, Instagram and Facebook, all via the first author’s personal profiles) and poster advertising in the local community (i.e., community notice boards, shop windows, and the local teaching-hospital gynaecology ward noticeboard). Participants were females aged between 32 and 62 years (mean age = 46.3 years) with self-reported UI which altered or limited their group exercise participation. Initially, 17 women were recruited and undertook an initial health screening interview. Two participants were found not to meet the health requirements of the study due to the presence of at least one additional chronic condition which may contribute to exercise limitations, and were removed before enrolment, leaving a total of 15 participants. Only participants recruited locally and who agreed to take part in a group exercise class (n = 6) were allocated to the intervention group, with the remaining participants (n = 9) allocated to the online control group.

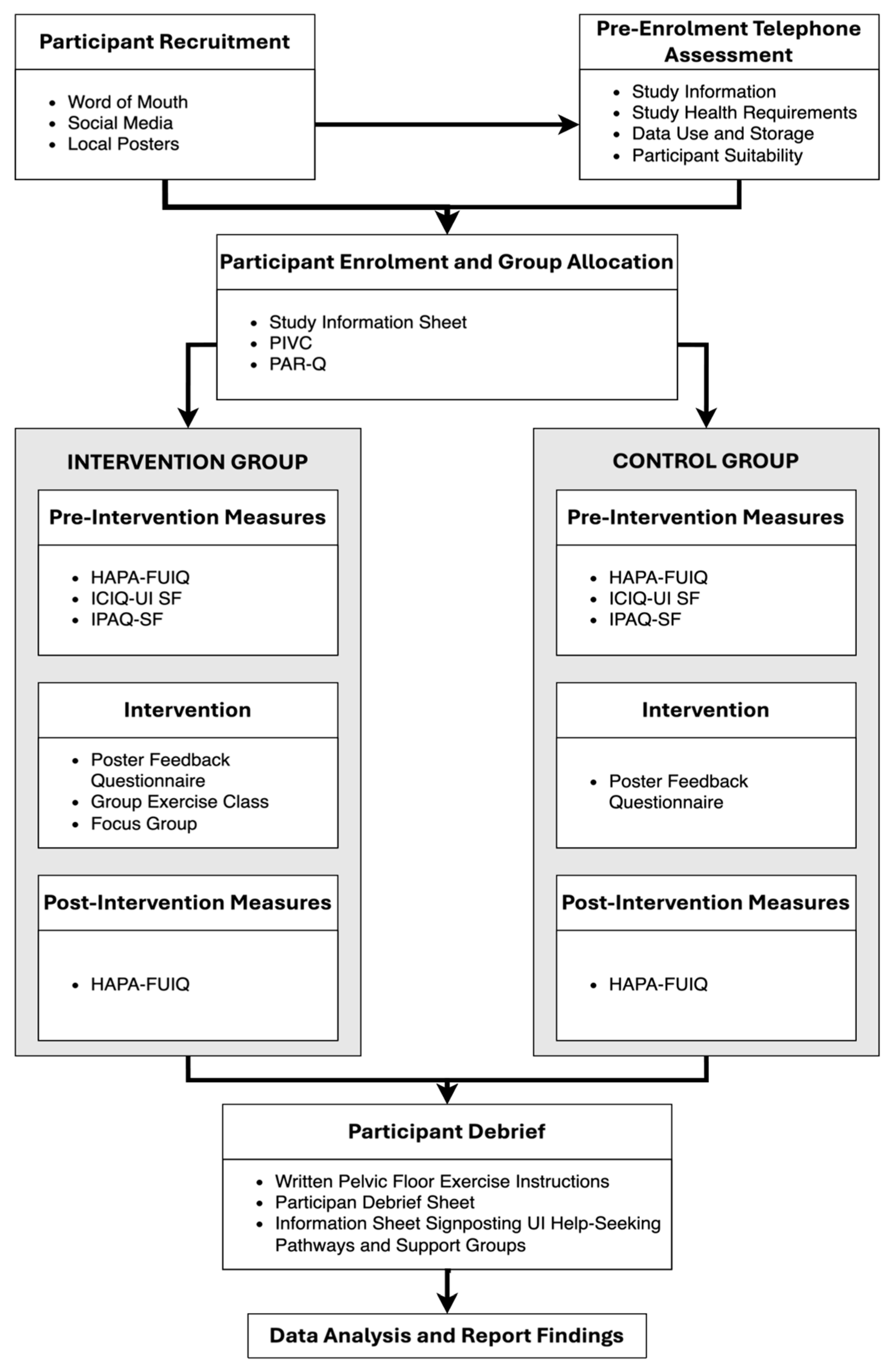

2.3. Procedure

The following study procedure was adhered to (see

Figure 1).

2.4. Screening and Enrolment

Immediately after recruitment, potential participants were emailed the study information and participant requirements. A Voluntary Informed Consent form was also emailed, and participants were allowed to ask any questions via email before returning the consent form. Once voluntary consent was obtained (n = 17), participants were asked to arrange a telephone appointment to undergo pre-grouping enrolment health screening. Any potential participant who was unavailable for telephone screening was able to complete the screening via email. Health screening was conducted using the Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q) to ensure each participant was safe to exercise and to minimise the likelihood of UI not being the only health condition limiting group exercise participation. The PAR-Q assesses current levels of physical health and was employed as a screening tool to ensure participants were safe to participate in a group exercise class [

57]. Participants were invited to answer 11 questions (for example, “Do you feel pain in your chest at rest, during your daily activities, or when you do physical activity?”) with yes/no responses. It was deemed important to only include women in the study who, despite experiencing UI, would otherwise be capable of participating in a group exercise class, thus ensuring any study recommendations aimed at helping increase women’s PA participation were likely concerning the impact of UI on PA ability, and not another health condition. During the screening process, the first author confirmed the aims and requirements of the study and how participant data would be handled, including how it would be anonymised. Participants were able to ask any questions and request any additional information before verbal consent to continue in the study was sought. Two participants were lost at the screening stage due to the presence of additional chronic conditions and were removed from the study before group enrolment. Six women were allocated to the intervention group based on their locality, availability and willingness to participate in an in-person group exercise class, with the remaining participants allocated to the online-only control group (n = 9).

Pre-intervention measures were administered online to both groups at the same time (with a 7-day return window), and the group exercise class and focus group were scheduled for the intervention group to take place two weeks later in a suitable university room. As outlined in

Table 1, both groups had similar (non-significant) baseline characteristics, showing participants engaged in PA at levels below current guidance recommendations and UI had a medium-to-high impact on quality of life.

2.5. Intervention

A dance-based group exercise class was designed with the aid of a qualified dance and fitness group exercise instructor. The class was designed primarily to limit the risk of participants leaking urine and was based on Ballroom and Latin dance, but with all jumping and moves, which placed stress on the pelvic floor muscles, removed. A woman’s pelvic floor specialist physiotherapist holding a fellowship with the Chartered Society of Physiotherapy was also consulted and made available throughout the study (online and in person), to guide decision-making and provide help to any participants requiring support during the group exercise class. Key characteristics of the class were altered from the ‘norm’ of common dance-based group exercise classes in the following ways as outlined below.

A ‘Reverse Instruction Method’ was used; this consisted of low-impact movements forming the basis of the class instead of the normal high-impact dance moves from the outset that one might expect. This was important as it allowed the exercise instructor to suggest higher impact movements “for those who feel safe to do them”, which could allow the participants an opportunity to assess the risk of increasing the intensity without fear of leaking or judgment if they could not do so. Wherever possible, medium intensity of exercise was maintained throughout the intervention class to maximise the exercise benefits given the time frame of the class. These changes and considerations were made based on evidence suggesting that participants often feel failure when group class instructors provide an “easier” exercise, particularly where the participant believes that the intensity is manageable, but the move itself is an issue (anything high impact or with legs apart, for example). This situation appears to be a reason why participants withdrew from the group PA environment. Therefore, it was decided to test whether reversing the normal method of instruction would prevent women from feeling this way and help them remain participatory.

A group instructor was also sought with characteristics that participants report as a deterrent to group exercise, for example, being less likely to consider group exercise if the instructor was male due to feeling he would not understand the issues UI presented in the exercise environment. A female instructor was therefore enlisted to conduct this study’s group class. The instructor was also required to be 35–59 years old, have experience with UI during exercise and be comfortable mentioning it in class. This decision was also informed by the screening procedure, where some participants reported they felt uncomfortable in front of younger instructors, even if they are female, and again, this was attributed to the perception that the instructor would not understand or consider UI’s impact on the women’s ability to perform certain exercises in class. The instructor also needed to be comfortable with participants leaving the class unexpectedly to use the toilet and also with participants halting exercise in places if they felt a move carried too high a risk of leaking—the ability to instinctively adjust exercises if the instructor observed this occurring was also a requirement but was not needed on the day due to successful design and execution of the reverse instruction method.

Consideration of the female toilet’s proximity to the exercise class was given high priority when choosing the location for the group exercise class. Ensuring the female toilet is adjacent to where women are exercising, allows those participants who leave mid-class to relieve their bladder minimal time out of the class, thereby maximising their exercising opportunity and minimising their discomfort.

An opportunity to socialise with fellow participants was factored in at the end of the class (and before the focus group started). The instructor also fostered an approachable, friendly environment, which allowed for social interaction during the class.

The group exercise class was preceded by a short health and safety briefing by the first author, and a medically trained pelvic health physiotherapist was introduced to help ensure participants were aware of her presence should they require medical attention or additional support during the class. Participants were encouraged during the briefing to use the toilet facilities as often as they needed and to not fear distracting the class instructor or other participants as a result. The group exercise class required no additional equipment, but participants were encouraged to bring water to remain hydrated. The class ran for 45 min, including warm-up and cool-down, at which time there was a 10 min break to recover and hydrate.

2.6. Focus Group

After the group exercise class, the intervention group participants (n = 6) took part in a focus group in an adjacent classroom. Refreshments were provided whilst the pelvic floor physiotherapist provided 15 min instruction and advice on performing effective pelvic floor exercises (PFEs), and the researcher briefed participants on the purpose of the focus group, obtaining verbal acceptance for recording the session and reconfirming the anonymising process and data handling.

The focus group aimed to explore the impact of the ‘pelvic-floor friendly’ group exercise class on behaviour change, particularly participants’ confidence to engage in PA, and to explore participants’ perceptions of the factors implemented in the group exercise class to help to understand whether these changes would motivate and/or provide confidence for women with UI to (re)participate in group exercise. Additionally, the focus group sought to aid understanding of the importance of the socialising opportunities group exercise can create, and whether having access to a pelvic floor specialist in the PA environment would help encourage women to be more active. The focus group lasted 64 min and was recorded for transcription purposes using a digital recording device.

The focus group began with the first author raising questions from the Interview Guide; however, participants quickly began directing the discussion, with the first author occasionally providing additional prompts for clarification, ensuring the discussion remained on-topic, or ensuring quieter participants had the opportunity to contribute.

Once the focus group ended and the recording equipment was turned off, the participants were thanked for taking part, and the process for undertaking the post-intervention measures was explained. Participants then had 30 min to consult with the pelvic floor physiotherapist to ask for advice or guidance on managing their condition and as a thank you for taking part in the intervention.

2.7. Group Exercise Advert Feedback Survey

Two days after the group exercise intervention and focus group concluded, both the control and intervention groups were emailed the group exercise advert feedback survey. The aim of the advertising feedback survey was to provide insight into the advertising of exercise programmes targeting women and how advertisements are perceived by women who experience UI when exercising. Participants were asked to complete the survey within 7 days.

2.8. Post-Intervention Measure

Two weeks post-intervention (and one week after the group exercise advertisement feedback survey was completed and four weeks from baseline) participants of both groups were asked to repeat the Health Action Process Approach-Female Urinary Incontinence Questionnaire (HAPA-FUIQ) measure within 7 days, to allow pre/post analysis of both groups (further details in

Section 2.10 below).

2.9. Participant Debrief

After the data analysis concluded, participants from both groups were contacted via email and thanked for their participation. They were also provided with a Participant Debrief, written instructions on how to perform effective PFEs and a guide to help-seeking pathways and managing UI during PA. Both the PFE instructions and help-seeking/UI management information were provided by the pelvic health physiotherapist alongside her contact details (at her request). This strategy also gave the online control group a similar opportunity to gain support from the pelvic health professional as the intervention group had.

2.10. Quantitative Measures

Pre-intervention data were collected via the International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form (IPAQ-SF), and the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire Urinary Incontinence-Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF). The PAR-Q was used as a screening tool, while the IPAQ-SF and ICIQ-UI SF were used to ensure the comparability of the two groups. The HAPA-FUIQ measure was employed both pre-intervention and post-intervention. The scoring criteria, reliability, and validity of the measures are reported by Gard et al. [

58].

2.10.1. International Physical Activity Questionnaire-Short Form (IPAQ-SF)

The IPAQ-SF measures physical activities that people do as part of their everyday lives [

59]. Participants are invited to answer up to 7 questions related to time spent being physically active during the previous 7-day period (for example, “During the last 7 days, on how many days did you walk for at least 10 min at a time?”). The number of days per week, as well as hours and minutes per day, if relevant, are recorded for vigorous, moderate, and walking activities, as well as the time spent sitting. This instrument has been validated for use in young and middle-aged adults, and also in older adults (≥60 years) [

60]. The instrument was chosen for this study as it covers the participant’s age range and provides an idea of both current sedentary time, and walking. In addition, it also measures the more commonly monitored moderate and vigorous PA levels. Sedentary time and time spent walking were considered important measures in this study, as the literature reports women often stop or reduce the intensity of exercise that they participate in due to their UI symptoms [

30].

2.10.2. International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF)

The ICIQ-UI SF measures the severity, frequency, and impact of UI on the quality of life in men and women and is commonly used in primary and secondary health settings [

61]. The ICIQ-UI SF includes three questions (for example, “Overall, how much does leaking urine interfere with your everyday life?) with a score range from 0 to 21. A score of 0 indicates UI does not occur and has no impact on quality of life, and a score of 21 indicates a high occurrence and severity of UI and a severe impact on quality of life.

2.10.3. Health Action Process Approach-Female Urinary Incontinence Questionnaire (HAPA-FUIQ)

The HAPA-FUIQ is an instrument adapted from the Health Action Process Approach (HAPA) theoretical framework, used to predict, modify, and explain health behaviours in a wide range of populations [

62]. The current instrument has been validated for use in predicting the physical activity behaviours of women who experience urinary incontinence and was chosen for the current study due to its ability, when combined with the data of the other instruments mentioned above, to provide greater insight into UI’s influence on women’s PA behaviour. The questionnaire consists of the following ten sub-scales, each rated by a seven-point Likert scale with anchors varying according to the content of the scales.

Outcome expectancies (OEs). Outcome expectancies were measured by seven items (for example, “For me, participating in at least 150 min of moderate-intensity physical activity over the next week would be enjoyable”), with higher scores indicating stronger agreement with the item.

Outcome expectancies-urinary incontinence (OEUI). Outcome expectancies (UI Specific) were measured by five items (for example, “I will be embarrassed due to leaking during physical activity”). Responses were made on 7-point scales ranging from 1 (Definitely False) to 7 (Definitely True), where lower scores indicate a better status of the responder towards outcome expectancies in relation to UI.

Risk perceptions (RPs). Risk perceptions were assessed via four questions (for example, “If nothing changes in my behaviour, my chance of developing or continuing to have poor mobility in the future is”) on seven-point scales with anchors of “Very Unlikely” (1) and “Very Likely” (7). Questions are worded so that lower scores indicate a more positive response to the item.

Action self-efficacy (ASE). Action self-efficacy was measured via three questions (for example, “Assuming I am motivated, I am sure that I can change my behaviour to be more physically active even if I find it difficult”). Responses were made on scales ranging from 1 (Definitely False) to 7 (Definitely True). Higher scores indicate stronger agreement with the item.

Behaviour intention (BI). Three items assessed behaviour intention (for example, “I plan to do at least 150 min of at least moderate intensity physical activity over the next week”) with anchors of “Definitely False” (1) to “Definitely True” (7). Higher scores indicate stronger agreement with the item.

Action planning (AP). Action planning was assessed with five items (for example, “I have made a detailed plan about how often I will do physical activity”) with anchors of “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (7). Higher scores indicate stronger agreement with the item.

Coping planning (CP). Nine items (for example, “I have made a detailed plan about what to do if bad weather interferes with my plans”), with anchors of “Strongly Disagree” (1) to “Strongly Agree” (7), were used to assess coping planning. Higher scores indicate stronger agreement with the item.

Maintenance self-efficacy (MSE). Maintenance self-efficacy was assessed via 21 items (for example, “it takes a lot of effort”) with the stem, “How confident are you that you will participate in physical activity of at least moderate intensity for 150 min over the next week even if…”. Responses were made on scales ranging from 1 (Very Unconfident) to 7 (Very Confident). Higher scores indicate stronger agreement with the item.

Recovery self-efficacy (RSE). This sub-scale measured participants’ recovery self-efficacy with anchors of “Very Unconfident” (1) to “Very Confident” (7) with nine items (for example, “Over the next week how confident are you that you can anticipate problems which may interfere with your planned physical activity session?). Higher scores indicate stronger agreement with the item.

Action control (AC). To assess action control, seven items were used (for example, “I often think about my physical activity goals during the day”) with anchors of “Definitely False” (1) to “Definitely True” (7). Higher scores indicate stronger agreement with the item.

2.10.4. Reliability Analysis

Cronbach’s Alpha (

α) coefficients of the self-administered HAPA questionnaire range from 0.6 to 0.98, indicating the questionnaire is internally consistent. The Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients for each construct and group can be viewed in

Table 2.

2.11. Qualitative Data

To collect the qualitative data, a semi-structured focus group was conducted with participants in the intervention group only, to gather feelings, perceptions, and thoughts toward the specific factors put in place during a group PA dance class, as detailed above. It was deemed a suitable method of data collection, as group discussion can facilitate the expression of spontaneous, and often emotional viewpoints when compared to individual interviews, as well as allowing participants to expand on the ideas and thoughts of others [

63]. Given the focus group aims, it was thought that this would lead to a richer dataset.

The focus group Interview Guide asked questions about participants’ previous experiences of group PA (i.e., “As an adult, if you attended group PA classes regularly, what did you enjoy about this method of exercise, especially?”), general barriers (i.e., “What are the top barriers that hinder or prevent your participation in group exercise?”), changes made to the intervention class (i.e., “Did making low-impact the ‘normal’ and higher impact the ‘additional needs’ help in terms of confidence and or controlling leaking?”), and finally, methods of delivering PFE instruction in the PA environment (i.e., “What about the language used? Do you think it is an effective way to communicate pelvic health information to women?”). Additional consideration was given to this method of data collection as the literature often suggests focus groups may not be suitable when the topic is considered sensitive, as UI tends to be. Sparkes and Smith [

63] attribute this to a high possibility of embarrassment hindering an honest participant response. The strategies recommended by Sim and Waterfield [

64] to help avoid issues associated with sensitive focus group discussions were considered and implemented to limit any unforeseen negative consequences.

Data were also collected post-focus group, using an online survey containing pre-dominantly open-ended questions, and some closed questions. The first three questions of the survey asked all participants, about their likes/dislikes of attending group PA, whether the opportunity to socialise is an important motivator for engaging in group PA, how experiencing UI during group PA affects their willingness to engage in group PA, and how the impact of UI on their group PA participation makes them feel. Some of these questions were similar to the focus group questions but the researchers felt it was important whether the opportunity to socialise is an important motivator for engaging in group PA, how experiencing UI during group PA affects their willingness to engage in group PA, and how the impact of UI on their group PA participation makes them feel. Some of these questions were similar to the focus group questions but the researchers felt that it was important to add the additional control group voices as it is an important topic and doing so would substantiate the findings from the focus group regarding how UI results in women withdrawing from, or modifying, their group PA participation.

The survey continued by asking for feedback on three group exercise advertisements to gauge participant perceptions of the language and imagery used, as well as the information given within the advertisement. Participants were also asked a series of questions regarding their confidence in attending, and their likelihood of attending each of the advertised classes before finally being asked which of the advertised classes they would be most likely to attend: Poster 1 was based on the imagery and language most used in advertising dance-based group exercise classes in a gym or leisure centre environment; Poster 2 introduced the suggestion of the class being ‘pelvic-floor friendly’ but with limited information on what that meant; and Poster 3 provided a fuller idea of the class being ‘pelvic-floor friendly’. The imagery was also changed to better reflect the most common demographic who are self-excluding from group PA due to UI—midlife adult women [

30,

65]. Additional information was also provided on Poster 3, including wording on ‘pelvic-floor friendly’ indicating its meaning as a low-impact exercise delivered using the ‘reverse instruction method’.

2.12. Data Analysis

Quantitative Analysis

Participants’ characteristics at baseline were described (means and standard deviations), including age, ICIQ and IPAQ. Mean scores pre- and post-intervention outcome (HAPA) measures were examined. Paired t-tests were conducted to examine within-group differences. Between-group changes were assessed via Mann–Whitney-Wilcoxon tests, and effect sizes were calculated to explore the magnitude of changes in variables from baseline to follow-up [

66]. The results of these analyses are included in

Table 3.

Qualitative Analysis

The focus group audio was transcribed verbatim using Otter.ai, and a hybrid inductive/deductive thematic analysis (TA) was used to analyse the focus group data and the group exercise advertisement survey data. Both data followed the same procedure but were analysed individually. TA was chosen as it “explicitly allows for social as well as psychological interpretations of the data” [

63], whilst a hybrid inductive/deductive approach was undertaken as it provides greater rigour to the TA process [

67]. More pertinent to the current study, Proudfoot [

68] demonstrated hybrid TA to be “highly compatible with quantitative work driven by the same theoretical framework” and combining inductive and deductive TA methods allows the researcher the freedom to choose the best methods for answering the research question, making it particularly suitable for mixed methods research with a pragmatic epistemological underpinning [

69].

Braun and Clark’s [

70] six-step framework for TA was used to guide the thematic process whilst also implementing additional recommendations for hybrid TA coding and theme development [

67,

68]. Step 1 involved the researcher familiarising themselves with the data; this was achieved with the focus group data by the researcher transcribing the audio and then listening to the full recording a second time, before reading and making notes on the transcripts. For the survey, the responses from each participant to the open-ended questions were copied into a table, which the researcher read and re-read, creating notes as necessary. Coding was conducted for step 2 by working systematically through both sets of written data using the hybrid inductive/deductive approach. Deductive analysis began by formulating initial codes based on the aims of the study, HAPA theory and prior research. The initial codes were then passed to a second researcher with experience in qualitative data analysis to corroborate, and any suggested differences between researchers’ codes, after discussion, were amended, added, or removed as necessary, before moving to the transcripts where the codes were used to help identify meaningful data and produce initial themes.

Once deductive TA was complete, transcripts were analysed three additional times in an inductive manner, highlighting any interesting or common concepts not captured during the deductive analysis phase. The inductive themes were then created before reviewing all identified inductive/deductive themes together (steps 3 and 4). All themes were finally reviewed against the study research question to ensure they shared meaning with the study aims before finalising the definitions and names of each theme (step 5). The analysis resulted in three general dimensions, eight themes and 19 sub-themes (see

Figure 2). Step 6 saw the writing of initial interpretations of the identified themes for each dataset, before merging all qualitative data and producing the results.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Study Aim 1

The study’s first aim was to determine whether a ‘pelvic-floor friendly’ group exercise class could influence the motivation or intent of women with UI to encourage women’s (re)engagement in PA. To do this, PA behaviours were measured pre- and post-intervention using the UI-modified and HAPA questionnaire, with the average HAPA construct sub-scale scores calculated for both the intervention and control group at baseline and follow-up (

Table 3). Non-significant improvements in all HAPA constructs were observed in the intervention group post-intervention, except for the constructs of Outcome Expectancy-UI (OEUI) and action planning (AP), which resulted in significant positive changes. Intriguingly, action self-efficacy (ASE) scores for the intervention group significantly decreased from baseline to follow-up; although not significantly different, the ASE scores were also higher at baseline for the control group. These ironic effects may have come about due to the participants having unusually high baseline scores, particularly the intervention group. The groups may not have fully understood the constructs being measured until they learned about what they were (i.e., in the intervention). As noted below, action planning was found to be significantly different at follow-up for the intervention group. According to the tenets of HAPA, action self-efficacy contributes to action planning, and this would further suggest that the baseline action self-efficacy scores were ironic [

71]. The control group showed minor changes in all constructs, but none were statistically significant, and there were no significant differences between groups.

Outcome expectancies are predominantly viewed as important in the motivation stage of HAPA where individuals consider the pros and cons of participating in PA [

62]. Our addition of the OEUI construct specifically added for predicting PA behaviours in women who experience UI is equally important in the motivation stage where participants anticipate the specific consequence of leaking urine if they were to undertake PA When comparing the pre-intervention scores for both constructs in the present study, it was noted that the OE of PA participation in both the intervention and control groups was viewed more negatively when the participants were asked to consider UI, specifically as an outcome of undertaking PA, as they were for OEUI. Previous research suggests that women omit considerations of UI symptoms during PA (even when UI is severe) unless they are explicitly requested to do so, and this behaviour may account for the more negative results recorded in OEUI when compared to OE. This view is corroborated when analysing individual responses where all participants (except one) from both groups responded with a maximum score (‘7’) to at least one of the items measuring OEUI at baseline, whilst only two participants in total included a maximum score for items measuring general OE. Post-intervention, the positive change in OEUI was significant within the intervention group only, suggesting the factors implemented in the intervention, which aimed to reduce the chance of experiencing UI during PA participation, may have positively influenced the perceived outcomes of being physically active where leaking urine is a possibility for women. Simply, participating in the group PA intervention may have provided the female participants with some degree of confidence, and it is possible to undertake PA without the risk of leaking; thus, the post-intervention measure of OEUI yielded a significant improvement in the intervention group.

According to the principles of HAPA, while outcome expectancies are important, they do not work in isolation to predict behavioural intention; ASE also has an influential role. ASE is the belief an individual holds that the action can be performed, and it has been shown to predict behaviour intention the strongest [

62,

72], but for many women with UI, having the belief that PA can be undertaken despite a risk of leaking may be difficult to achieve. As a result, the current intervention was designed to specifically influence ASE by providing women who experience UI during PA with both an opportunity to gain PA support from a pelvic health physiotherapist and to participate in a group PA class designed to minimise their risk of leaking, with the belief that a successful conclusion to participants’ engagement would result in a greater belief that they can perform PA in the future. However, contrary to expectations, post-intervention ASE for the intervention group decreased. As noted above, this occurred across both conditions. It is possible that these results may be due to an accidental inflation of participant ASE at baseline caused by the way recruitment was undertaken. It was thought that women who had withdrawn entirely from group PA due to UI would present a challenge for recruitment to a group PA intervention study; therefore, recruitment materials were purposely explicit in stating that strategies had been implemented into the intervention design to minimise participant’s leaking risk and to maintain their comfort. The researcher felt that if women could be reassured that the intervention was a safe environment to (re)engage in group PA and that it would meet their needs in terms of managing their leaking during exercise, recruitment would be more successful. However, by explaining this convincingly, the strength of the beliefs that participants held in their own capability of participating in the PA intervention without leaking may have been stronger at baseline than if the recruitment materials had been less convincing; thus, this indicates a negative change where a positive one was envisaged. It remains unknown whether the intervention influenced ASE, although, focus group findings in the study presented below provide additional insights into the intervention’s influence on women’s confidence and beliefs in their ability to participate in group PA despite experiencing UI.

As previous studies indicate, for intention to develop into action, some degree of planning is required, and individuals who engage in planning practises are more likely to engage in higher levels of PA [

72,

73]. At follow-up, the intervention group recorded a significant positive change in the AP variable, indicating that the intervention had a positive effect on the AP processes in some way. It is important to note that AP was not a variable of interest in this study as it was thought that without group PA classes of a similar design to the intervention class being available in the community, planning would yield little change; therefore, these findings were unexpected but may have arisen due to the cumulative positive changes observed in the motivational stage variables. According to HAPA, individuals who formulate plans of when, where, and how they will perform PA are more likely to translate their intention to exercise into action [

62], and it may be the case that intervention participation provided women with additional strategies to manage their UI during PA, which then allowed participants the confidence to make plans for engaging in other activities.

In summary, the findings of the pre/post-intervention testing suggest that a pelvic-floor friendly group PA intervention can positively influence women’s PA behaviours, but additional testing of the impact of such an intervention on ASE is required.

3.2. Study Aim 2

The study’s second aim was to explore women with UI perceptions and feelings toward the design elements of a ‘pelvic-floor friendly’ group exercise class, including when combined with access to a women’s specialist pelvic health physiotherapist. Focus group audio yielded 65 min of data, culminating in 10,575 words of transcribed verbatim text. Thematic analysis identified 42 meaningful units, 19 themes, 8 categories, and 3 general dimensions, i.e., women with the UI group’s PA behaviours, a failure to consider midlife women’s needs, and additional support to help women manage UI during PA) (

Figure 2).

3.2.1. Women’s Group PA Behaviour

Reasons to Engage in Group PA

The focus group began with participants being asked to consider factors which contribute to group PA being their preferred mode of exercise to gain insight into urinary incontinence and women’s motivations for attending group PA classes. Participants unanimously cited enjoyment as their primary motive for participation. For one non-exercising participant in particular, the intervention reminded her of why she had “loved’, and now missed, attending group exercise classes:

“You might not go and make your best friends in life, but you will go and have a good time with women having a laugh and embarrassing yourself like we just did. I had a blast! And I haven’t had a blast like, I want to cry, I haven’t had a blast like that in ages.”

The link between enjoyment and motivation is well evidenced in the literature with many studies reporting higher rates of motivation to exercise and long-term PA adherence when individuals perceive the PA mode as enjoyable [

31]. Rodrigues et al. [

74] recorded a high number of participants in their study, who maintained a steady amount of exercise 6 months after their initial assessment, attributing it to high levels of perceived enjoyment measured; however, enjoyment alone may not be enough to encourage women to go back to group PA or to ensure that women continue with group PA after experiencing UI, and in the current study, the older participants appeared to equally value the social opportunity group PA provided, suggesting it may be a possible facilitator to enjoyment:

“I think sometimes when you go into group things, it isn’t really about what you’re doing. It’s about the people that you’re with that makes it fun.”

The importance of social opportunities for midlife women is rarely included in loneliness or social exclusion studies; however, we know that women in this life stage often report having little time to participate in PA due mainly to caregiving responsibilities [

10], ignoring their own needs in favour of managing the needs of others [

75]. Baumbach et al. [

38] suggest that such caregiving also leads to feelings of social exclusion rather than loneliness and that providing opportunities to socialise can help positively influence those feelings in midlife adults. Therefore, it seems appropriate to prioritise group-type exercise when promoting PA to women to maximise feelings of social inclusion and reduce psychological distress; however, given that social isolation can increase when women withdraw from group PA due to UI [

54], successfully promoting social inclusion and enjoyment may be difficult without first understanding the exact factors that UI impacts and lead to women’s group PA withdrawal.

Reasons to Withdraw from Group PA

Participants discussed their enjoyment of dance-based group PA, in particular, and this appeared to be the most common mode of group-based PA, with five out of the six participants preferring this specific method over any other form of exercise. Despite their strong preference, all except one of the participants were not currently participating in dance-based PA:

“Absolutely anything with music and I love it… but I stopped because there was a lot of younger girls there and I just felt ’oh God! I’m going to wet myself!’ So, I ended up not going and I did other things, but I would like to be able to go back to that, or a modified version of that.”

All six participants reported a fear of leaking in front of others to be the main reason for their withdrawal from group PA. Withdrawal from general PA due to the stigma, embarrassment, or fear of leaking in front of others is well-cited in the literature [

6,

24,

76]; however, as this participant demonstrates, the threat of leaking in front of younger women seems to be particularly troublesome for the midlife women in this study. A multi-billion-dollar industry has developed around anti-ageing as society tells older women they are undesirable and ugly [

77] and that youthfulness equals attractiveness [

78]. Many women develop body dissatisfaction as they grow older as a result, but while most studies in this area agree that body dissatisfaction is higher in women than in men, the evidence regarding ageing being an influential factor is mixed. For example, in studies looking at body dissatisfaction across the life course, older women have been reported as being more likely to dislike their body, particularly when experiencing poor health [

79], and in studies including midlife women, they have been found to have higher body dissatisfaction, higher ageing anxiety and are more likely to participate in anti-ageing behaviours as a result [

80]. However, others have reported ageing has little effect, with body dissatisfaction remaining stable across the lifespan [

81]. Regardless of whether ageing increases body dissatisfaction, when the midlife woman experiences UI, body dissatisfaction may be intensified in the presence of younger women due to the negative stereotypes and stigma often associated with UI. For example, UI is often perceived as shameful and embarrassing, and of note is the assertion that UI represents the “beginning of old age” [

82]. This stereotyping of UI as an ‘old lady’ condition may contribute to midlife women’s fears of leaking in front of younger women during group PA due to the assumption younger women will view them as disgusting, old or incapable. However, perhaps somewhat surprisingly, it appears it is not only younger women whom midlife women fear leaking in front of in a group PA setting:

“… it was brilliant, the social element, and even though it was full of women older than me when I started leaking, I stopped… and I can’t exercise. I can’t do anything. Can’t do more than walk.”

A fear of leaking in front of older women was mentioned explicitly by this participant only; however, the researcher observed other women nodding in agreement, though they declined to comment when prompted. Using the term “even though”, suggests the participant feels UI is an older woman’s condition and that it may be expected or more acceptable to experience UI in that age group—a view reflected in the literature [

82,

83]. One may then expect midlife women who exercise in groups with older women to be more likely to continue group PA participation after experiencing UI during PA; however, the participant clearly states this was not the outcome of her experience, and she withdrew from group participation, and, indeed, all forms of PA except for walking. During pre-intervention testing, the participant reported her UI as bothering her the most out of all participants in the intervention group, and it may be that despite exercising with older women, she feels unable to manage her UI during any form of PA; this relationship between UI severity and PA levels is discussed later in this section.

While two participants stated they withdrew from group PA immediately after experiencing UI, the remainder discussed the different strategies, whether successful or not, that they employed to try and maintain their PA participation. Exercise adaptations appeared as a common strategy, where exercisers can choose to undertake an alternative, often lower-impact exercise to the class norm, to help avoid predicted pain, discomfort, or, in this case, leaking urine. While exercise adaptations were appreciated by all participants, it appeared the number of adaptations required negatively impacted motivation to continue attending group classes:

“It does put you off going. I would like to go to high-impact style classes… but I can’t do that anymore because it would be too embarrassing, because I would have to adapt too many of the exercises.”

Despite motivation and self-efficacy for exercise being high, and this participant exceeding current WHO PA guidelines, withdrawal from group PA still occurred, due to feeling embarrassed by the number of adaptations needed to avoid leaking during class. To the best of the researcher’s knowledge, this is the first time the volume of adaptations required has been reported as a barrier to participation, as no corroborating literature could be found; however, exercise adaptation, in general, is a commonly reported strategy utilised to help avoid leaking during PA and to maintain PA participation by reducing the exercise intensity, impact or changing the exercise type [

84].

The final reason for group withdrawal, which the women discussed was, worsening UI symptoms. As women age, UI can progressively worsen [

85] leading women to worry about their long-term health outcomes:

“It’s progressively getting worse, and I think to myself now, it’s going to get to a point where well, already I’ve not gone to workouts because there’s skipping in the program and if this keeps getting worse, I’m not going to be able to do it anymore and that’s really going to impact my mental health.”

The participant talks as if worsening symptoms are almost inevitable, which corresponds with women’s perceptions of UI and ageing previously reported in the literature. For example, Shaw et al. [

83] found UI was viewed as a normal part of ageing by over two-thirds of Canadian women, and this assumption had not changed over the past decade, despite public health campaigns and increased treatment awareness, suggesting health education is either failing in its messaging or additional factors require addressing. Already, the participant is avoiding PA classes where particular exercises are programmed despite reporting a relatively low ICIQ-SF severity score, and, despite her younger age (36 years old), the participant indicates concern over worsening UI symptoms and the impact the resulting reduction in her preferred PA mode will have on her mental health. Given that women experience poorer mental health than men across their lifespan, including higher rates of depression and anxiety [

86], the potential for the withdrawal from favoured modes of PA to exacerbate mental health decline is concerning and would seem worthy of further investigation.

Reasons to Continue Engaging in Group PA

Despite most intervention group members reporting UI as a reason they withdrew from group PA, and the motivations expressed for preferring this mode of exercise seemingly doing little to counteract that outcome, two participants continued regularly attending group PA classes. Both participants reported exceeding the current WHO physical activity guidelines, and the HAPA-FUIQ measurements indicate both are at least moderately motivated to be physically active; however, it should be noted that both also reported their UI bothered them “a little” and they reported the lowest UI severity in the group. A correlation between UI severity and PA participation levels has been reported in the literature [

87], and it is therefore possible the presence of all these factors may indicate these participants are predisposed to continue their preferred mode of PA and less likely to find their UI unmanageable during exercise. Despite this, it seems important to understand, in women’s own words, their perceptions of what drives them to continue participating in group PA, despite leaking urine whilst doing so.

As previously discussed, the social aspect of group PA is particularly coveted by all women in the focus group and is a reason for group participation. However, for two women currently participating in regular group PA and another who occasionally still attends group sessions, exercising with others also motivated them to continue participation despite experiencing UI and previously expressing fear of leaking in front of others:

“Makes you kind of feel like, ’oh, actually, I really need to go’, because if I don’t turn up maybe somebody else will feel less motivated because I haven’t gone.”

All three women conveyed feeling obligated to attend scheduled group PA because others in the class may be relying on them for motivation and encouragement:

“If you don’t go, people notice you don’t go and so there’s a little bit of you that goes ’oh! I can’t miss it this week’”.

Contemporary research exploring the role of peer pressure or peer accountability on midlife women’s PA adherence is scarce; however, a study of 19–57-year olds found exercising with others was important for fostering accountability at both the inter and intra-personal level, for programme adherence [

88]. Another study which compared younger women (aged 18–26 years) to older women (≥59 years old), examining their motivation for PA, reported that young women preferred exercising alone while the older women preferred to exercise with others, and this improved older women’s motivation for PA [

89]. Both studies suggest that midlife to older-aged women’s PA levels may be positively influenced by including a social element in the group class; however, due to the demographics of two of the three participants discussed here, it remains unclear as to whether feelings of obligation to other group members can evoke enough of a motivational response to overcome severely bothersome UI or the fear of leaking in front of others, as posited by those women in the focus group who have fully withdrawn from all group PA. Nevertheless, the current study’s findings suggest that encouraging strong inter-group friendships to help foster feelings of obligation to others may be an important consideration to further ensure that highly volitional women with low severity of UI, remain participatory in group PA.

Both the regular group-exercising women, plus another who attends the “occasional low-intensity group class”, also discussed the need to have time to themselves away from the demands of the home. Caring for others is the most cited barrier to women’s PA, where women are often too preoccupied with tending to others to prioritise their own health needs, including the need to be physically active [

75]. However, some women use group PA as a way of not only overcoming the social isolation that can occur with caregiving [

38], but also ensuring time for themselves:

“It’s an opportunity for me to go out on my own…and not have sticky little hands pulling at me, you know?”

Making an excuse for ‘self’ through group PA participation is a particularly important endeavour since women who have caring responsibilities are more likely to experience episodes of poor mental health than those women with none [

90], and PA is an effective treatment for improving mental health [

3]. For another participant, having something in her diary gives her motivation:

“it also maybe is about something to look forward to”. In psychology research, having a future event planned has been demonstrated to improve well-being and happiness [

91,

92], and according to the tenets of HAPA, planning the type of PA alongside where and when it will be undertaken facilitates an individual’s transition from intention to be physically active, to being physically active [

62]. Indeed, this was corroborated by another participant:

“I think there’s something quite motivating about a regular class that you go to and you just do it”. This view is supported in the literature [

93] and suggests the simple act of a suitable group PA class being available, that can be planned for, is motivating.

3.2.2. A Failure to Consider Midlife Women’s Needs

Exercising with Women of a Similar Age

Next, participants were asked about any differences they had observed between previously attended group classes and the intervention class recently undertaken—none of the design changes made in the intervention class were explicitly mentioned by the researcher. Several women were aware of being in the intervention with women of similar age to themselves and that this was unusual as so many classes they thought they would enjoy were seen to be mainly advertised to younger women. These classes were then interpreted as being both high-intensity and high-impact and beyond what the women felt their pelvic floor could cope with. When discussing the high-intensity levels, there was a general feeling of the midlife group member’s needs being ignored, particularly by group instructors who rarely seemed to consider the specific adjustments midlife women might need when programming high-impact exercises, though one participant thought instructors might be aware midlife women are more likely to be unable to undertake some exercises, they chose to ignore their needs in favour of the younger members of the class:

“Part of their brain is maybe aware that if they’ve got perhaps slightly older women in the class, they should be more careful, but actually that all just get swept aside in the ’well, I’ve got lots of 19/20-year-olds, so we’ll just cater to those people and the older people will just have to pretend they’ve got bad knees’.”

Most women seemed to feel that they were simply left to find a way to cope with UI themselves during group PA. Almost all the women felt they had tried to maintain their participation in group PA by adapting exercises in the class to avoid the risk of leaking; however, few in the focus group felt they had the knowledge to do this without worrying if their adaptations were safe. With no support being given from the class instructors, the women felt they had no choice but to “pretend they’ve got bad knees” to save their embarrassment at not being able to do certain exercises due to the impact on their pelvic floor. One participant felt that not being able to undertake the same exercises as the younger women in their exercise class was embarrassing, even if their inability is disguised through feigning injury:

“Normally you will see all these younger people and you’re the only one that is walking, and you know, it’s like everybody can see you as if you wore fluorescent clothes!”

Feeling as if you stand out due to leaking, whether you are seen to be wet or not, is a common feeling for women with UI and often leads women to try and hide their symptoms to avoid stigma [

55,

94]. When a stigmatised condition is revealed to others, it can result in the rejection of the individual from that social setting [

95] and worry over the risk of discovery of an as-yet-undiscovered stigmatised condition, such as UI, can lead to psychological distress [

94,

96]. For women trying to hide their UI in a group PA setting, worry over others finding out about their UI can result in a loss of enjoyment and, ultimately, withdrawal from group PA.

Rather than withdrawing from group PA altogether, several women tried to remain participatory by seeking out classes aimed at older women, as these were assumed to be of lower intensity and, therefore, lower impact, and subsequently, more pelvic-floor friendly:

“I find that I’m going along to ’old lady’ classes because I know I’m not going to affront myself, but then you come out of there and you’re like, ’well, it’s been nice and you’ve had a nice chat and had a bit of exercise’, but you can’t do anything hardcore, really.”

As discussed previously, there is an assumption that exercising with older ladies is ‘safer’ if you expect to leak during the class and as such, the risk of being stigmatised because of UI is lower. However, several women felt that attending lower-intensity classes aimed at older women also reduced their enjoyment somewhat. For most, it was due to the already covered social aspect of group exercise:

“I went to a class where everybody is 70 plus and I’d be like, yeah, it’s great but, you know, socialising, it’s been taken out”.

But for others, there appears to be a drop in enjoyment due to the lower exercise intensity experienced in these classes. To the best of the researchers’ knowledge, no studies have reported the impact on enjoyment from reducing the intensity of exercise from mid/high intensity to low intensity in midlife individuals who regularly participate in high volumes of PA, and who are also forced to permanently reduce their normal intensity level through illness or injury. However, a study comparing the intensities of walking football to that of small-sided running football found the higher-intensity running football was rated more enjoyable by older male and female participants (aged ≥60 years), although the authors of the study note this may be, at least in part, due to the majority of participants regularly participating in the higher-intensity running football and thus developing a preference toward it [

97]. This caveat may also suggest that it is possible an individual’s level of fitness influences enjoyment when participating in high-intensity PA, a view further strengthened by a study of non-exercising obese women, which found participants experienced lower levels of enjoyment when undertaking high-intensity interval training compared to moderate-intensity continuous exercise training [

98]. While overall, the evidence on which intensity exercise leads to higher perceived enjoyment in physically active adults is mixed, several studies have reported that high-intensity interval training (HIIT) is more enjoyable than medium-intensity continuous exercise [

99]. Research has suggested that at least some of the enjoyment elicited from HIIT may be due it being more time efficient, a factor which could be used to help influence busy midlife women to re-engage or continue with, group PA [

99].

Needs Ignored

Following on from their discussion of attending older women’s exercise classes to manage UI during group PA, the conversation orientated to the way the intervention class instructor had delivered the class using, what one participant referred to as, an ‘upside-down approach’. As previously outlined, it is standard practice in a group exercise class for a class instructor to provide lower-impact exercises to replace some of the most high-impact exercises, to help prevent pain and exacerbation of any injuries or health conditions. Exercisers can choose to perform these lower-impact exercises if they feel they are at risk, while the rest of the class continues with the normal exercise. However, the intervention instructor was asked to use a ‘reverse instruction method’ for the current study. The reverse instruction method maintains low-impact exercise as the norm and offers higher-impact alternatives for class members who feel their pelvic floor can cope safely. It is worth noting that a medium/high intensity of exercise was maintained throughout the session as much as possible.

Surprisingly, given the number of participants in the intervention group who have withdrawn from group PA due to UI, the researcher observed that none of the women during the intervention were avoiding any of the lower-impact exercises. Where the instructor gave higher-impact or higher-intensity alternatives, two women chose to undertake all of these, with two more attempting at least some. Overall, the participants felt this method of exercise instruction gave them more than simply the ability to participate in group PA:

“You don’t feel as if you’re letting anybody down, I suppose, including myself and the instructors and everything else, because you’re doing what everybody else is doing. And if you want to do a bit more, then that’s fine, but you’re not feeling that, you know, ’Oh no, I better not do that’.”

Participants reported the intervention instruction method helped reduce anxiety and the fear of leaking in front of others. It also appeared to help with avoiding feeling pressured to perform, with the above-quoted participant suggesting she was able to undertake all exercises and moves in the class, which then helped her feel included and aided in avoiding the feelings of failure or judgement which often followed the need to adapt or withdraw from high-impact exercises. The participant who had totally withdrawn from all modes of PA due to UI was particularly exuberant about the reverse instruction method undertaken:

“I think that it helped that the instruction wasn’t that ’we are going to do it this way and we will all be watching if you don’t do it’. The instruction was, ’We will all be doing it this way, but if you want to be stupid knock yourself out!’.”

Being judged by others featured heavily throughout the focus group session, particularly in relation to the participants’ previous experiences of requiring alternative exercises during group classes to ensure they remained dry. Few studies explore women’s fear of judgement in the PA environment and how it impacts PA engagement; however, a recent study by Seal et al. [

100] found that fear of judgement resulted in women changing exercise mode, withdrawing from all exercise entirely or choosing to exercise alone. The study also reported that the participants’ fear of judgement was most often related to how their bodies were judged and perceived by others, especially while moving during exercise [

100]. Whether UI exacerbates body image fears and fears of being judged in the group PA environment is beyond the scope of the current study; however, a study by Gümüşsoy et al. [

101] found as UI severity increased, body image perceptions were more negative, suggesting if the reverse instruction method can reduce feelings of judgement by providing women with the opportunity to participate at a similar impact/intensity as everyone else, women may be encouraged to stay participatory in group PA for longer. Future researchers may wish to explore this idea further.

After commenting on midlife women’s need to undertake alternative lower-impact exercises and those needs being largely ignored by group exercise instructors, the conversation turned toward the inconsiderate timings of suitable low-intensity classes:

“Everything is either for younger women, or for older women because they are low impact… they’re all at 10:00 AM when I’m working!”

As before, the assumption is that classes perceived as for younger women are entirely unsuitable to the needs of midlife women who experience UI during PA and, considering women in this study and others have reported seeking out lower-impact group PA to manage their leaking and remain participatory in group exercise, it is disheartening that these types of class appear only available during the working day, further exacerbating the idea that they are only for ‘older women’ and midlife women’s needs do not matter. Another participant voiced her annoyance at the lack of consideration of midlife women’s working patterns:

“I’m 55, so potentially still got 12 years to my retirement date. What happens in that time, when I’m working full-time? You can go to the stuff at night but that’s all the ’let’s lift each other up’ type of stuff.”

Participants appeared to understand that their long-term health depends on being physically active, but when there are no suitable classes available to achieve their goals, they are understandably frustrated, which may provide insight into why 50% of women reduce their PA levels during this life stage [

75]. As with men, there are more women aged 35–49 years in work than in any other age group [