Abstract

The digitalization of educational systems and the corresponding impact on the learners’ improvement require modern pedagogical approaches to increase motivation among learners in distance learning. According to the literature, authentic e-learning and real-world themes create a dynamic learning setting and enhance learners’ engagement; however, the impact of adopting authentic learning has not been investigated for deaf learners in a sign language e-learning setting. Therefore, this study aims to examine the effect of adopting authentic learning for the design of e-learning for deaf learners. The study employed a mixed-methods approach by conducting a one-group pre-test–post-test with 11 deaf learners and measuring design principles of authentic learning via semi-structured interviews. The statistical portion analyzed the T-test and Cohen’s d-effect size, and the result showed that e-learning through authentic themes was significantly effective. The interview results revealed a positive attitude toward using e-learning based on an authentic learning approach, which increased deaf learners’ motivation. It was found that e-learning based on an authentic sign language e-learning setting and technology enhances deaf learners’ satisfaction and motivation with their first e-learning experience.

1. Introduction

Authentic e-learning is identified as integrating real-world situations into e-learning settings to enhance motivation among learners in different educational settings. E-learning design based on an authentic learning approach has greatly benefited by increasing the effectiveness of learning settings. In this learning environment, motivation will be increased between learners by involving them in the teaching process. Recent studies have highlighted that learning through authentic themes increases learners’ communication around teaching topics and enhances motivation by fostering engagement [1,2]. Authentic learning has the potential to adopt effective factors for designing a meaningful learning environment where learners can share their real-world experiences with their peers. In addition, e-learning settings with authentic themes have provided a dynamic learning environment that aims to increase learners’ engagement [3].

Distance learning, known as online or e-learning, has created a modern type of educational system by offering flexible and accessible learning materials. This approach influences digital platforms and technological tools to facilitate collaboration and provide sources without needing physical attendance, the same as in a traditional classroom. Distance learning enables learners to study at their own pace and provides opportunities for different learners in different locations [4].

In the 1960s, with the development of technology and computers, the concept of e-learning was first designed to deliver teaching content by focusing on drill and practice with a lack of interactivity [5]. Later, the development of simple e-learning systems throughout e-learning history revealed information on the need to switch to more inclusive approaches in content delivery and technology, particularly for diverse learners. As evidenced by the COVID-19 pandemic, which emphasized the need for inclusive and equitable digital learning environments, e-learning has evolved significantly for inclusion learners [6,7]. Today, the design of e-learning continues to progress with the integration of technologies and interactive digital tools to enhance motivation and improve learning outcomes [8]. These improvements can gradually be merged with inclusive design principles for supporting equity in education for all learners.

Learning through authentic learning helps learners become more dynamic and increases their motivation. Herrington et al. [9] proposed nine principles for designing an authentic learning setting and including all areas of twenty-first-century skills development. Authentic tasks at the core of authentic e-learning settings serve as stepping stones to promoting engagement and reinforcing teaching concepts. Adopting multiple roles with different outlooks during tasks supports higher-order thinking skills. Likewise, the tasks lead learners to identify their experiences in the target problems and solve them by collaborating in the learning process, where reflection is processed and drives opportunities for articulation. Instructional techniques such as coaching and scaffolding are increased in collaborative learning when learners share their knowledge in realistic contexts and practice it in a real-world situation [10].

However, studies on e-learning for deaf learners are limited, and the impact of the factors to increase engagement and motivation among deaf learners through e-learning in sign language has not been explored. Although some studies on deaf education suggest that technology tools draw attention to addressing the factors in designing e-learning for deaf learners, increasing motivation and investigating the effective factors are still gaps in deaf distance learning [11,12]. Therefore, this study aims to explore how authentic e-learning affects deaf learners and increases their motivation through learning a foreign sign language.

Research Questions

- RQ 1. Does authentic e-learning positively affect deaf learners’ improvement after treatment?

- RQ 2. What are the participants’ perceptions (deaf learners) about e-learning based on the principles of authentic learning?

- RQ 3. To what extent do technological tools for tasks affect deaf learners’ motivation?

2. Background

2.1. Distance Learning and Authentic E-Learning

Learning from a distance is a way of transferring knowledge without having face-to-face connections and currently happens through digital devices and applications, such as web-based learning. E-learning is a platform for distance learning in which the learners can join online tutorials via smartphone or laptop. E-learning allows learners to be tough on their schedule (self-paced) and provides a flexible learning setting. E-learning promotes the flexibility of education and encourages learners to progress learning at their own pace. Additionally, e-learning improves the digital literacy of both teachers and learners and increases collaboration between learners by integrating technology tools into the teaching environment [13,14,15].

Technology tools to design e-learning platforms by preparing an interactive learning setting enhance learners’ interest and increase their motivation. Additionally, to provide collaboration opportunities in learning concepts, employing technology tools is the critical component [16]. Technology and user-friendly learning platforms allow learners to access teaching materials in an easy way, anywhere and anytime. E-learning can support the learner’s needs, and it is particularly valuable in contexts where traditional educational resources, such as classrooms and face-to-face instruction, are limited or inaccessible [17].

Authentic e-learning increases the engagement between learners, and creating collaborative learning is the key to increasing the effectiveness of e-learning [18,19]. The studies provide significant results to show the impact of employing authentic learning in the design of e-learning settings that enhance engagement while involving learners in real-world situations. Learning from real-world contexts increases problem-solving skills and develops critical thinking and collaboration [1,2].

2.2. E-Learning for Deaf Learners

E-learning for deaf learners provides opportunities for continuing their education through inclusive and accessible systems. By integrating visual aids and using both sign and oral language. Using subtitles and interactive content in e-learning platforms can enhance interest and motivation among deaf learners. The study on the design of e-learning for deaf learners highlighted factors for developing problem-solving skills [20]. Another study highlighted that collaboration between deaf learners should be increased through e-learning settings by embedding technology tools into the learning settings [21]. Since e-learning should also increase motivation among deaf learners, the correct, precise, and supportive digital platforms for deaf people need to be embedded into the e-learning setting and be more effective for teaching and learning. Effective learning results can be facilitated by e-learning since the model itself is available everywhere and at any time [22].

Deaf learners’ motivation through e-learning can be effectively enhanced by designing highly visual materials such as pictures and videos and adopting technology tools to increase their interest in being taught. For instance, encouraging deaf learners and keeping learner’s interest created some challenges, such as communication and not encouraging during online lessons [23]. Aljedaani et al. [20] believe in the accessibility of learning materials in e-learning, and because most deaf learners have poor literacy skills, adequate visual aids and subtitles can have benefits and are major elements to encourage. It also requires employing any visual aids that are employed as a theme to design and embed visual aids into the learning settings [24,25].

Previous studies presented that e-learning for deaf learners can be used, with advantages like increased motivation and engagement; however, there remain questions for understanding teaching approaches that influence deaf learners’ interest in learning from a distance [26].

2.3. Learning Challenges of Deaf Learners

Research believes that learning from a distance can have many challenges for deaf learners in parallel with having several benefits, such as flexibility. These challenges have arisen when improving learners’ skills such as problem-solving, collaboration, and communication, impacting teaching outcomes [22]. There is a lack of teaching approaches to how learning from the real world may increase motivation and influence the learning processes of deaf learners when e-learning is used for learning from a distance. There is a significant gap in the literature, especially in research on increasing motivation among deaf learners in distance learning [27,28].

In language learning, deaf learners have fewer abilities in reading and writing in the first language compared to hearing ones, which increases learning challenges [24]; thus, transferring their abilities from the L1 to the L2 cannot depend on the same condition as hearing peers. Learning language happens by mapping between oral language and printed vocabularies between hearing learners; however, deaf learners, because of the lack of auditory, do this mapping through hand movements and onto a visual code via sign language [26]. Thus, teaching deaf learners (L1, L2, L3) involves more than just written material; visual aids like pictures, videos, and sign language are also crucial [24,25]. Deaf learners learn from visual materials [26]. Therefore, supportive technology tools can increase deaf learners’ motivation to learn from a distance when the teaching materials can be observed in real-life situations [27]. It is recommended that the design of learning environments should support the needs of deaf students, including visual aids that present deaf culture [28] and the use of instructions through sign language [21].

In an e-learning environment, the research explored strategies to develop accessibility in e-learning for deaf learners, concentrating on how characteristics can support these learners’ needs. Likewise, adaptive technology tools for enhancing engagement and illustrating e-learning settings play a key role in promoting digital education for them [23]. The study suggested that the performance of an online education system may be influenced by the attitudes of deaf learners toward it, specifically their level of satisfaction with it. Happiness and better performance in online learning courses are positively correlated with lower dropout rates [29].

Despite the lack of sufficient teaching approaches in e-learning environments designed for deaf learners, as mentioned by [26], using e-learning would have negative effects due to a lack of videos with sign language translation, the unavailability of real-world learning contexts, and the limitation of visual learning design. This means that adopting videos for designing e-learning for deaf learners can have a significant impact on deaf learners’ learning processes [30].

In addition to these challenges for deaf people, preparing for learning online has difficulties for both learners and teachers, where face-to-face communication is eliminated and can reduce the motivation between learners. Therefore, the design of e-learning does not only help improve the skills of learners; it also should encourage learners to be motivated in the learning setting. Teaching deaf students through digital tools has more difficulties for teaching deaf students when all teaching materials have to be prepared for visual needs. As stated by World Health Organization research, the opportunity of distance education may be the only chance to have a modern educational system if there is no face-to-face learning, even if online education reduces motivation and engagement among deaf learners [31]. However, some studies suggest that deaf learners learn from their real-life situations when they can observe and feel them in their daily lives [32]. Deaf learners regularly depend on their observation of real-life contexts to develop their knowledge and skills [25]. Visual consciousness and focus on the details gained by observations are the main characteristics of deaf people [33]. Adopting real-life situations that can feel them in social environments and the deaf community provides rich experiences for learning [34,35,36].

2.4. Authentic Learning and Tasks

Learning from real-world situations, or authentic learning, is one common teaching approach that was used in different learning fields, and studies showed that including real-world scenarios in the assignments increases the engagement of foreign language learners [37,38,39]. Authentic learning by involving students in the learning subject increases motivation among learners when adopting tasks and raises the opportunity for students to develop their problem-solving skills [33]. To encourage students to use the target language in their communication, authentic tasks by immersing learners in authentic scenarios prepare them for real-world challenges [34]. Martínez-Argüelles et al. [39] believed that authentic learning allows learners to engage in the learning process and the cognitive domain is increased. This kind of learning, also called learning from real-world situations [12], prepares the learning settings by using authentic tasks to achieve something in a meaningful teaching environment. Significantly, learning from outside of school enhances their learners’ memory and problem-solving skills, which are applicable in their lives.

Güneş et al. [2] believed in the value of using real-world situations for designing learning environments and highlighting the learner’s value concerning what they are taught in real life. Roman et al. [35] described this approach as the common teaching method and said authentic learning is the idea that the tasks should somehow have a connection to the real-world situation, which increases the learners’ practice in real-life phenomena.

Adopting real-world situations to design learning environments and tasks are key factors in increasing motivation among learners [40]. Collaboration as an important factor in creating active learning settings is increased when real-world situations apply to learners. Authentic learning highlights the use of real-life problems to increase the problem-solving skills of learners by fostering learners to find their solutions by completing their tasks. Tasks at the core of authentic learning encourage learners to share their ideas, which mirror authentic challenges, and develop critical thinking and creativity skills [41]. The goal of learning through an authentic learning approach is to encourage learners to work together and increase their motivation for preparing their final products [42].

Despite research to explore the effects of authentic learning in different educational contexts, the lack of research specifically addressing deaf learners through e-learning is notable. This leads to the current study being designed and formulating research questions to fill this gap in the current literature.

3. Materials and Methods

The current study adopted a mixed-methods strategy to examine the effectiveness of authentic e-learning when both qualitative and quantitative views are considered for answering the research questions. Therefore, to understand to what extent the course contributed to learning British Sign Language (BSL), participants were given a test before and after teaching (pre-test, post-test). Additionally, the qualitative part of this study employed semi-structured interviews to explore deaf learners’ views on the learning process.

3.1. Population of the Study

The study used purposive sampling to acquire data in a reliable position. The sample consisted of eleven deaf adult learners from both the north and south sides of Cyprus who had two different sign languages (as L1): Greek sign language (GSL) and Turkish sign language (TSL). The age range of participants was between 30 and 50 in both genders, seven males and four females. Moreover, Turkish Cypriot participants’ education levels varied, with some having completed primary school and secondary school. Greece Cypriot participants have high school education diplomas. Socioeconomic status was clarified based on their income, whether from employment or government assistance.

3.2. Ethical Approval and Data Collection Procedures

The procedure for collecting data started when the study was approved by the ethics committee of the university, and the consent of participants was gathered via an online form that included QR codes in both TSL and GSL videos. This study lasted three months in the spring of 2024. The quantitative data was collected by taking a test before and after treatment. The multiple-choice test was adopted from https://bslsignbank.ucl.ac.uk/quiz/ (accessed on 16 January 2025) and https://www.signlang-assessment.info/tests-of-l1-development.html (accessed on 20 January 2025), and the test was developed according to the North Carolina Testing Program (NCTP). The test’s validity and reliability were confirmed by a pilot study, and Cronbach’s alpha yelling a value of (0.814) in both pre- and post-test, representing acceptable and suitable internal consistency that is higher than 0.7. However, some essential changes happened according to the pilot study test and the suggestions from a deaf BSL teacher. Thirty-five multiplicate-choice BSL questions were processed both before and after treatment to collect the quantitative data.

To gather qualitative data, semi-structured interviews, observations, and video recordings were used. To maintain the validity of the data from the qualitative part, data source triangulations such as observation, video recordings, and interviews were followed [33]. In addition, the twenty questions were reviewed by deaf BSL teachers and one more expert in the deaf education field. The qualitative part focused on increasing motivation and engagement in a collaborative learning setting with real-world applications. In addition, the effect of the integration of technology into design tasks in a sign language-based learning setting is considered. Therefore, the following criteria were applied for designing interview questions:

1. The participants’ view about the e-learning environment is based on nine principles of authentic learning (Herrington et al. [9]).

2. The difficulties during learning FL through e-learning.

3. Adopting the tasks in sign language is helpful to increase the learner’s motivation.

4. Providing an online platform for communication purposes increases learner’s interest and collaboration.

5. The impact of an e-learning environment for deaf learners. (positive and negative effect)

6. What should be included or eliminated factors to be considered for e-learning for deaf learners?

At the end of the teaching process, the first author and BSL teacher scheduled a day for the interview and determined approximately twenty minutes for each participant. The results from this part were recorded by a video recorder in sign language and then interpreted into written English. This section was analyzed using the coding procedures recommended by Miles et al. [43], which involved classifying the data according to the main areas of study and exploring the participants’ perspectives in depth.

4. E-Learning Design and Implementation

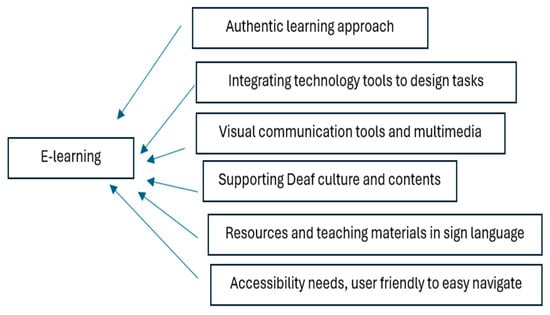

Authentic e-learning refers to creating engagement between learners and involving them in the learning process. Authentic concepts to design e-learning by integrating technology tools increase deaf learners’ interest by supporting their emotions and behavior when the learning is in sign language and respecting their culture [36]. It is also another important factor, the availability of teaching materials in sign language in e-learning settings for engagement with online courses. Adopting multimedia to create and design a communication platform increases the effectiveness of e-learning readiness and the technological ability of deaf learners. The authentic e-learning model was developed according to nine principles of the authentic learning approach [9] to increase the effectiveness of e-learning by adopting the important factors that were mentioned before. The model (Figure 1) aims to increase motivation and communication around an authentic theme in an online environment and also improve the digital knowledge of participants.

Figure 1.

The developed model of e-learning for deaf learners.

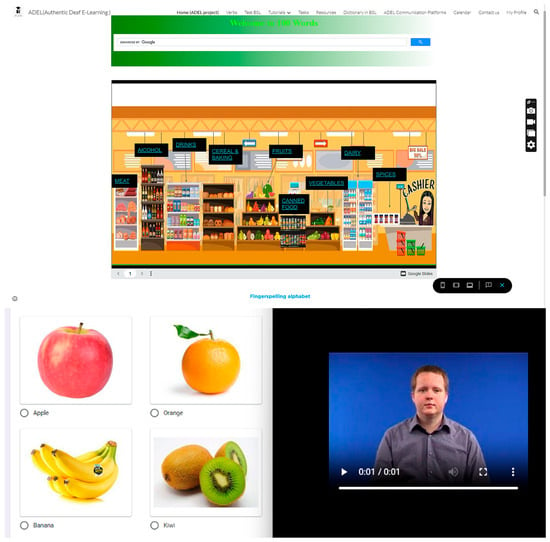

Thus, e-learning was designed through Google Sites based on an authentic subject (see Figure 2). The study adopted supermarket items to teach the target vocabulary in sign language form. Each supermarket stand was designed to be easily accessible to the product and to show the tutorial page. The vocabulary size was one hundred words, including vegetables, fruits, proteins, and dairy products. A video recording in sign language was used to demonstrate each topic on the tutorial pages (BSL dataset: https://www.signbsl.com/ (accessed on 20 January 2025)). In an e-learning environment that was clickable and allowed the learners to access the recorded videos in BSL, the written vocabulary and pictures for each item were supplied. After receiving instructional materials based on the principles of authentic learning, the self-paced learning was completed in three months. Online tools like dictionaries and currency calculators were also made available in e-learning environments. A Facebook group is used for communication and material sharing, and learners can freely view each other’s GSL, TSL, and BSL recorded videos. At the beginning of the learning process, the students received basic technology instruction, which included how to use Google Docs, Sheets, Slides, and Padlet. Each week, learners watched videos in BSL e-tutorials, and at the end of each month, they discussed what they had learned. The synchronous meeting sessions on the learning process, problem-solving, and answering the questions that happened through Google Meet, and their positive and negative sights during learning and using the tasks were recorded.

Figure 2.

Parts of e-learning.

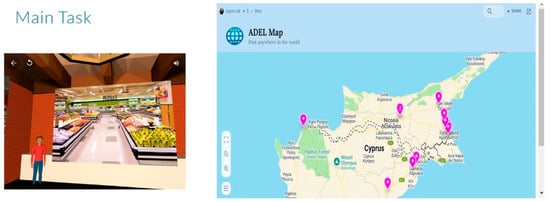

The Design of Tasks

The current study used technology tools to design authentic tasks that were carefully prepared according to the characteristics of authentic activities [2], which focus on deaf adult learners’ ability to learn a foreign sign language while also using technology. Therefore, we designed a fictional scenario for the learning theme and design of the task (ex: Figure 3). The scenario was about a financial officer checking the supermarket prices, comparing them, and preparing a report for the Minister of Finance. To locate the supermarkets, the Padlet program was used, where the learners could pin and comment on their opinions about the supermarkets located. The final product was recorded videos in BSL embedded into PowerPoint. Additionally, technology tools such as Google PowerPoint and Word have been used to design subtasks where learners could share their information about the production’s quality and price.

Figure 3.

The virtual design of a supermarket environment on the task page and using Padlet map for one task.

5. Data Analysis and Results

To answer the first research question, a paired samples t-test was conducted to compare the mean scores of deaf learners on the pre-test and post-test. Therefore, for the analysis of e-learning effects on deaf learners, mean values of pre-test and post-test were determined. To measure effect size, Cohen’s d was calculated.

According to a paired sample, learners’ achievement scores on the pre-test and post-test means differ significantly, as evidenced by the reported 30.818 difference between the pre-test and post-test means (Table 1). In addition, Table 1 demonstrated that the mean post-test score (M = 170.91, SD = 15.940) was significantly higher than the mean pre-test score (M = 140.45, SD = 16.501) when t-value (10) = 14.691 and Sig (tailed) <0.001. Moreover, the effect size of the course |d|:|mean difference|/standard deviation = 4.429 > 0.80 (Table 2), which Table 3 demonstrates a large effect size (According to the statistical results, learning through authentic e-learning improved the performance and post-test scores of participants. It appears that online learning was advantageous because the website’s resources and educational materials are easily accessible to increase deaf learners’ vocabulary knowledge.

Table 1.

A paired sample statistic.

Table 2.

A paired samples test (Paired differences).

Table 3.

A Paired sample for estimating effect sizes.

To address the second and third research questions (deaf learners’ opinions on authentic learning principles and the use of technology tools to design tasks), the data gathered from the semi-structured interviews according to the nine authentic learning principles and defining the advantages and disadvantages of authentic e-learning.

E-learning with real-life contexts: The results showed that deaf learners were satisfied with the e-learning setting prepared through authentic themes. Some of the participants indicated their opinions below:

“E-learning is a good way to teach. I went to the website to see teaching materials every time I needed them, it was understandable and easy to use. The topic of communication was interesting. It enhanced our communication when we see the different prices in different supermarkets daily.”(P2)

“It was my first experience learning through e-learning and was helpful when we compared the prices of supermarket items in BSL.”(P6)

- Authentic tasks: Deaf learners acknowledged that the tasks in e-learning with authentic contexts made for a more meaningful learning process where they see the authentic concepts in their real-world situations. It increased their interest in learning. Some of their perceptions are indicated below:

“Thanks to recorded videos by the teacher on how I can use applications for doing the tasks, we worked together we were more active. We had the opportunity to talk about something that we have experienced.”(P2)

“My opinion on having task is positive, I learned how I can use Google Docs, sheets, … I have never had this opportunity before. It motivates learners to do something.”(P6)

“I was active in contact with other friends. Before we did not have this communication in a group, I liked the topic, because it is our daily life events, going to the supermarket and comparing the prices. But, for me it was difficult to use technology because I do have not good technology knowledge, I am the mom of two kinds.”(P3)

- Scaffolding: The study used two different sign language users to increase scaffolding among learners, according to ZPD’s Vygotsky [35]. Due to having a better level of L1 in one group (Greek Cypriot), authentic e-learning provided scaffolding and coaching opportunities. The teacher and their groupmate helped Turkish Cypriots learn the meaning of some vocabulary in BSL. According to their views, e-learning includes both Greek and Turkish Cypriot encouraging them to use the new BSL vocabulary to communicate with each other while completing the task and sub-tasks.

“I learned finger spelling in BSL first. Thanks to the teacher and my friends, they corrected my mistakes in BSL spelling. A teacher helped us choose good resources in the Internet, he also recommended me to use an application, we uploaded videos to our Facebook group, and my friend gave some feedback on my video…. It was good. I am happy to join the learning via Internet.”(P7)

- Multiple perceptions: Deaf learners believed that the different results from participants were interesting. For example, some of them did not agree with other results to name the cheapest and most expensive supermarket. Learning more because of having different results from tasks. Therefore, learners did not lose their interest and worked on the purpose topics.

“Using technology tools was very challenging for me, but it is ok I see I need to learn it; I searched some information on YouTube, and I asked from teacher. Both visual and written vocabularies were good enough to understand the meaning of the words. Yes, we had different results which I did not agree with some of them, I had some comments on … video, because I watched his videos which I disagreed about his given information.”(P4)

- Collaboration is one of the most notable characteristics of authentic e-learning for deaf learners when they freely share their opinions, learn, and correct each other.

“The video for doing tasks provided by a teacher was helpful, he used a screen recorder program and sent us. We work together. I asked…, …To know how they complete their task. I think it means we had a good working.”(P1)

“Yes, we finished the final homework, yes! Its name was the task, and we presented it. It helped me to be motivated because I had to finish on my part.”(P10)

“Having a story (scenario) in the tasks provided us with a better understanding of BSL, I showed the vocabulary in BSL, but still, I have to learn more English vocabulary to learn more words in BSL. Cyprus has many British deaf people who come here as tourist; I hope I have more communication with them.”(P2)

- Reflection on other products was another positive element of authentic e-learning. According to the observations from deaf learners’ views, they learned to analyze their work and compare it with their peers.

“…we freely discussed on recorded videos and also during online meetings.”(P2)

- Articulation in the learning process is another advantage of using authentic learning. Articulation involves learners articulating their experiences during problem-solving processes, which helps learners to have deep observations on problems and share their solutions as a finding.

“…asked me about …supermarket, I asked why you bought from there? No quality, there is another brand cheaper with higher quality, and I gave the address.”(P4)

- Authentic assessment Deaf learners liked authentic assessment when they compared it with their traditional assessment in school that they had. The main purpose of authentic assessment is to evaluate learners’ understanding and how they solve problems.

“The teacher gave good information about why we have to learn English, and he corrected our mistakes in spelling vocabulary. because spelling words and the alphabet in BSL is very different.”(P1)

- Expert performance According to this principle, students experience their instructor’s help and assess them in applying the new information to their assignments and tasks.

“The teacher taught the pronunciation of vocabulary related to supermarket items in BSL, his correction of our mistakes was helpful, we used them in our recorded videos …”(P7)

- Positive parts: As indicated by deaf learners, the e-learning process was mostly satisfied when authentic learning and tasks were the core of lessons. Additionally, it was remarked that their communication through authentic themes in e-learning was effective in promoting their BSL as an FL. They also mentioned that motivation through this program was because of creating something through technology tools and discussing their products, especially after they learned the difference between FL with L1.

“Learning through the Internet was good with finding pictures about economic problems on the Internet, technology provides more easy ways to learn something.”(P3)

“I was interested in learning BSL, I thought BSL was the same as my language (TSL), however, I found the different shapes of sign language in BSL, e-learning gathered us from the south and north sides of Cyprus, which before we had not had this experience.”(P1)

“E-learning provides the ability to have communication with friends.”(P2)

- Negative parts: Although deaf learners were positive about e-learning, some learners said there were some weaknesses, like having more meetings and their technological knowledge needing to improve; however, the weakness of L1 literacy in writing and reading was mentioned as a great problem for deaf people. In addition, the speed of the Internet and the quality of digital tools were reported.

“Understanding what we have to do for tasks, was a little bit difficult. We should have more meetings and more time to discuss it.”(P1)

“The learning through the Internet was hard for me, ex: knowing the basic knowledge of technology, having good Internet speed… but it helped me to learn something different.”(P3)

“The tasks could be easier, I had difficulty in downloading programs on my mobile phone, I do have not laptop, and I couldn’t complete the task on my own.”(P9)

The results from quantitative data show the effectiveness of authentic e-learning for deaf learners when the improvement happened after treatment and there is a significant difference between the pre- and post-test grades. In addition, qualitative results indicate that using the authentic theme of supporting deaf learners in distance education caused motivation among participants when they were interested in talking about the prices and inflation in their local supermarkets. The subject of preparing distance communication and discussion is important when some participants agreed that through e-learning and digital platforms, they attempted to communicate in different sign languages.

Adopting technology tools to design tasks and learning settings encouraged deaf learners to improve their digital literacy, same as British Sign Language. However, in some others’ beliefs, difficulty in using and learning technology tools was reported. In addition, the important role of the teacher was mentioned when they were asked about the kinds of support; they believed that the teacher for deaf learners is the key to preparing motivating learning settings. From their perspective, e-learning and distance deaf education can be boring if there is no theme for discussing and working on it. The participants also emphasized that employing visualization tools and using sign language are the base factors in designing any learning setting for deaf learners.

6. Discussion

Initially, it is important to mention that the results proved that the motivation among deaf learners increased when there were authentic themes to design the e-learning setting. The results from the current study revealed the positive impact of adopting authentic learning relevance with real-world situations for designing e-learning for deaf learners. The mixed-method analysis of e-learning evaluation through pre-test, post-test, and interview shows reliable improvements in learning British Sign Language (BSL). The result strongly indicates that authentic e-learning positively impacted deaf learners in their first online learning experiences. For instance, an increase in the mean in the post-test was observed (mean increase from 140.45 to 170.91). These findings highlight the benefits of adopting an authentic theme in fostering engagement between deaf learners in learning environments [37,42,43].

Observation and video recordings provided a closer view and communication patterns that were not fully captured in the interviews. The analysis of the interview part provided more detail about the strengths and challenges of the e-learning approach and how adopting a dynamic (real-world) theme increases the communication and motivation between learners and enhances their understanding. Moreover, the results show that participants applied authentic concepts in practice and showed their confidence in using foreign sign language [24,38,40].

In addition, this aligns with research suggesting that authentic online learning impacts increasing motivation among learners [39]. In addition, another study on hearing learners, such as [38], believed that learning from real-world situations plays an important role in developing education and shows that the nine principles of authentic learning to design learning environments are also applicable in online contexts.

Additionally, technology tools to design effective, authentic e-learning settings and authentic tasks should be employed. Technology tools are important to increase motivation, especially for deaf learners who may need more support. Adopting technology in learning design also improves the digital skills of learners [44]. This was also found from the results in which deaf participants mentioned their technology knowledge improvement. We would like to highlight that trying to integrate authentic themes in online courses and design tasks for deaf learners can sometimes be complex for the instructor. Therefore, the teacher must first increase the level of technology knowledge, which is the most important vehicle to increase motivation through communication. Future studies may explore how to tailor different ICT tools and technology tools to increase motivation among deaf learners.

In addition, as indicated by Shadiev et al. [16], learning through an authentic learning approach increases collaboration between learners and encourages them in the learning process. Adopting authentic tasks as the main element in an authentic e-learning setting increases collaboration between deaf learners when they have to produce something as a final product and present it. Additionally, the results conducted by studies on authentic subjects and tasks, increase motivation and communication through authentic themes [37,45,46].

Using visual materials provides motivation and creates scaffolding opportunities for designing tasks for deaf learners. As stated by [47], visualization is the first factor for deaf learners and affects their reading skills. Although integrating technology tools is helpful in increasing the visualization of online learning, it needs to increase the technology literacy of deaf learners, ref. [45] believed that the challenges of using technology tools are due to having enough teachers with a good level of knowledge for these learners.

It seems that adopting technology tools assists deaf learners in video calling communication and then increases collaboration in completing their tasks. This study observed a collaborative learning process when deaf learners tried to find solutions for inflation in markets. This mentioned the importance of improving the problem-solving skills of learners. As stated by Herrington et al. [9], learners need to develop problem-solving skills in their real lives. Similarly, ref. [41] indicated that when the main aim of learning settings is to increase problem-solving skills between learners, they are more encouraged to have a positive role in finding a real-world solution for a real-world problem. This agreed with our results when deaf learners communicated to find a solution for economic problems and supermarket inflations through the target language when they were excited to produce their digital final product and present it to the Ministry of Economics.

Finally, authentic tasks when applying technology tools create some difficulties for deaf learners. This suggests that the technology tools should be appropriate for deaf learners, and tutorial videos to download and use the technology tools should be provided in e-learning settings as extra teaching resources. Additionally, the results show that Greek deaf learners felt more comfortable than Turkish deaf learners with using technology and teaching materials. This aligns with the important role of having a better first language (L1) in searching materials in Google. Therefore, further studies on deaf education and deaf learners can focus on the impact of technology tools on increasing L1.

7. Research Limitations

Firstly, the small size of participants was a limitation when the study faced a lack of a control group. Secondly, due to the lack of technology literacy among participants, the study took time to teach the basics of using technology tools, and because of the time limitation, a limited number of tasks for the evaluation of the final prototype was considered.

8. Recommendations and Conclusions

We admit that we are acutely aware of the numerous discussions regarding improving the literacy of deaf students in L1 and that further study and pedagogical strategies are required in this field. Additionally, it is highly advised that deaf students be taught in an interactive visual environment. Deaf learners must learn how to use e-learning effectively in a suitable and sign language-based learning environment. E-learning and distance learning are strategic choices, and students with hearing impairments must have adequate digital devices and Internet speeds. For deaf students who struggle with technology and instructional materials, individual tutoring may be necessary.

As a recommendation for designing e-learning for deaf education with authentic themes, considering deaf cultures and their needs to be embedded in learning settings should be given priority, which increases motivation and the positive effect of online learning. The results can be gathered from interviews with deaf learners to understand their interests in authentic topics.

In conclusion, this study provided reliable results to present the positive effect of authentic themes in e-learning, and motivation among deaf participants was observed. The findings indicated that the combination of real-world situations and technology tools to design tasks increases engagement and assists in inclusive educational practices. Moreover, implications of sign language-based tools, interactive visual aids, and real-time captioning to design motivated and active e-learning environments are needed. Furthermore, the importance of preparing a collaborative learning setting was highlighted. The role of authentic e-learning in enhancing the learning experience for deaf learners was observed, and the study addressed the specific needs through inclusive and visually rich environments to bridge the gap in deaf education and promote deaf learner’s lifelong learning.

As indicated by deaf learners’ perspectives, learning through real-life situations increased their learning motivation, and the flexibility of e-learning prepared them an opportunity to learn in their free time. The research questions addressed the satisfaction of deaf learners, and their learning through an authentic theme was useful. Moreover, additional factors were gained for designing an e-learning setting for deaf learners, which could be helpful for future research. Factors such as adopting sign language-based learning settings and designing the learning setting around Deaf culture were found as additional elements for designing e-learning. To sum up, this study examined the effects of authentic learning as an intervention on BSL proficiency in an online sign language learning environment. Future research on the writing abilities of deaf learners can examine the efficacy of this strategy. As a result, a larger deaf population can be studied using more realistic tasks. Since deaf learners did not receive instruction in a physical institution, learning a foreign language (FL) in sign format was a great opportunity for them. The current study aimed to close the gap in the literature on authentic e-learning for deaf learners. E-learning is feasible and can increase motivation among deaf learners. To improve distance learning for deaf learners, schools must provide and support deaf students’ needs. Lastly, distance education could bring more opportunities for deaf people to ensure their future success in academics and careers.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, N.N., İ.Ö. and A.F.M.; methodology, N.N., İ.Ö. and A.F.M.; software, N.N.; validation, N.N., İ.Ö. and A.F.M.; formal analysis, N.N.; investigation, N.N., İ.Ö. and A.F.M.; resources, N.N., İ.Ö. and A.F.M.; data curation, N.N.; writing—original draft preparation, N.N.; writing—review and editing, İ.Ö. and A.F.M.; visualization, N.N., İ.Ö. and A.F.M.; supervision, İ.Ö. and A.F.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted by the Educational Sciences Ethics Committee at Eastern Mediterranean University Institutional Review Board’s Ethics Committee, Approval Code: ETK00-2023-0199; Approval Date: 24 October 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The authors will make the data supporting this article’s conclusions available upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Di Blas, N. Authentic learning, creativity and collaborative digital storytelling. Educ. Technol. Soc. 2022, 25, 80–104. [Google Scholar]

- Güneş, G.; Arıkan, A.; Çetin, T. Analyzing the Effect of Authentic Learning Activities on Achievement in Social Studies and Attitudes towards Geographic Information System (GIS). Particip. Educ. Res. 2020, 7, 247–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pohan, J.E.; Ikawati, E. Authentic assessment of communication skills high school student in Indonesia. J. Posit. Sch. Psychol. 2022, 6, 596–605. [Google Scholar]

- Marek, M.W.; Chew, C.S.; Wu, W.-c.V. Teacher experiences in converting classes to distance learning in the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Distance Educ. Technol. 2021, 19, 89–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alawajee, O. Influence of COVID-19 on students’ sign language learning in a teacher-preparation program in Saudi Arabia: Moving to e-learning. Contemp. Educ. Technol. 2021, 13, ep308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoylenko, N.; Zharko, L.; Glotova, A. Designing Online Learning Environment: ICT Tools and Teaching Strategies. Athens J. Educ. 2022, 9, 49–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sangrà, A.; Vlachopoulos, D.; Cabrera, N. Building an inclusive definition of e-learning: An approach to the conceptual framework. Int. Rev. Res. Open Distrib. Learn. 2012, 13, 145–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guaña-Moya, J.; Arteaga-Alcívar, Y.; Criollo-C, S.; Cajamarca-Carrazco, D. Use of Interactive Technologies to Increase Motivation in University Online Courses. Educ. Sci. 2024, 14, 1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, J.; Oliver, R. An instructional design framework for authentic learning environments. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2000, 48, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.Y.; Hariyanti, U.; Chen, N.S.; Purba, S.W.D. Developing and validating an authentic contextual learning framework: Promoting healthy learning through learning by applying. Interact. Learn. Environ. 2023, 31, 2206–2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamakhsyari, F.; Wibowo, A.T.; Milad, M.K. Enhance User Interface to Deaf E-Learning Based on User Centered Design. MATICS J. Ilmu Komput. Dan Teknol. Inf. (J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol.) 2022, 14, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, G.; Şahin, F.; Doğan, E.; Okur, M.R. Influential factors on e-learning adoption of university students with disability: Effects of type of disability. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 2022, 53, 2029–2049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, S.L.; Council, M.L. Distance learning in the era of COVID-19. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2021, 313, 389–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kusmaryono, I.; Jupriyanto, J.; Kusumaningsih, W. A systematic literature review on the effectiveness of distance learning: Problems, opportunities, challenges, and predictions. Int. J. Educ. 2021, 14, 62–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sabagh, H.A. Adaptive e-learning environment based on learning styles and its impact on development students’ engagement. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2021, 18, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shadiev, R.; Yang, M. Review of studies on technology-enhanced language learning and teaching. Sustainability 2020, 12, 524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillmayr, D.; Ziernwald, L.; Reinhold, F.; Hofer, S.I.; Reiss, K.M. The potential of digital tools to enhance mathematics and science learning in secondary schools: A context-specific meta-analysis. Comput. Educ. 2020, 153, 103897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, J.; Oliver, R.; Reeves, T.C. Patterns of engagement in authentic online learning environments. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2003, 19, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrington, J.; Reeves, T.C.; Oliver, R. A Guide to Authentic E-Learning; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Aljedaani, W.; Krasniqi, R.; Aljedaani, S.; Mkaouer, M.W.; Ludi, S.; Al-Raddah, K. If online learning works for you, what about deaf students? Emerging challenges of online learning for deaf and hearing-impaired students during COVID-19: A literature review. Univers. Access Inf. Soc. 2023, 22, 1027–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuwono, I.; Mirnawati, M.; Kusumastuti, D.E.; Ramli, T.J. Challenges of deaf students in online learning at universities. Al-Ishlah J. Pendidik. 2022, 14, 2291–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, M.M.; Carrano, A.L.; Dannels, W.A. Adapting experiential learning to develop problem-solving skills in deaf and hard-of-hearing engineering students. J. Deaf Stud. Deaf Educ. 2016, 21, 403–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luangrungruang, T.; Kokaew, U. E-Learning Model to Identify the Learning Styles of Hearing-Impaired Students. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontra, E.H.; Csizér, K.; Piniel, K. The challenge for deaf and hard-of-hearing students to learn foreign languages in special needs schools. Eur. J. Spec. Needs Educ. 2015, 30, 141–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kontra, E.H. The foreign-language learning situation of Deaf adults: An overview. J. Adult Learn. Knowl. Innov. 2017, 1, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Birinci, F.G.; Saricoban, A. The effectiveness of visual materials in teaching vocabulary to deaf students of EFL. J. Lang. Linguist. Stud. 2021, 17, 628–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqraini, F.M.; Alasim, K.N. Distance education for d/Deaf and hard of hearing students during the COVID-19 pandemic in Saudi Arabia: Challenges and support. Res. Dev. Disable. 2021, 117, 104059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmed, M.E.; Hasegawa, S. Development of New Distance Learning Platform to Create and Deliver Learning Content for Deaf Students. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ávila Caica, O.L. Teacher: Can you see what I’m saying?: A Research experience with deaf learners. Profile Issues Teach. Dev. 2011, 13, 131–146. [Google Scholar]

- Lawyer, G. Deaf education and deaf culture: Lessons from Latin America. Am. Ann. Deaf 2018, 162, 486–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flórez-Aristizábal, L.; Collazos, C.A.; Cano, S.; Solano, A. CollabABILITY cards: Supporting researchers and educators to co-design computer-supported collaborative learning activities for deaf children. Sustainability 2022, 14, 14703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.M.; Abreu, A.M.; Holmström, I.; Mineiro, A. E-learning is a burden for the deaf and hard of hearing. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 9346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F.M.; Rato, J.R.; Mineiro, A.; Holmström, I. Unveiling teachers’ beliefs on visual cognition and learning styles of deaf and hard of hearing students: A Portuguese-Swedish study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mounty, J.L.; Cohen, O. Assessing Deaf Adults: Critical Issues in Testing and Evaluation; Gallaudet University Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Roman, T.A.; Callison, M.; Myers, R.D.; Berry, A.H. Facilitating authentic learning experiences in distance education: Embedding research-based practices into an online peer feedback tool. TechTrends 2020, 64, 591–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manavalamamuni, D. The influence of Visual Learning Materials on Learners’ Participation. In Read, Write, Easy: Research, Practice, and Innovation in Deaf Multiliteracies; Ishara Press: Lancaster, UK; Worthing, UK, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 45–87. [Google Scholar]

- Arikan, A.; Çetin, T. Authentic Learning in Social Studies Education. In New Horizons in Social Studies Education; SRA Academic Publishing: Trowbridge, UK, 2020; pp. 193–212. [Google Scholar]

- Cross, I.D.; Congreve, A. Teaching (super) wicked problems: Authentic learning about climate change. J. Geogr. High. Educ. 2021, 45, 491–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Argüelles, M.J.; Plana-Erta, D.; Fitó-Bertran, À. Impact of using authentic online learning environments on students’ perceived employability. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2023, 71, 605–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, M.; Solheim, I.; Zhao, M. Can task-based language teaching be “authentic” in foreign language contexts? Exploring the case of China. TESOL J. 2021, 12, e00534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, H.W.; Liu, Y.; Law, N. An In-Depth Study of Assessment of Collaborative Problem Solving (CPS) Skills of Students in Both Technological and Authentic Learning Settings. In Proceedings of the Interdisciplinarity of the Learning Sciences, 14th International Conference of the Learning Sciences (ICLS), Nashville, TN, USA, 19–23 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pais Marden, M.; Herrington, J. Encouraging reflective practice through learning portfolios in an authentic online foreign language learning environment. Reflective Pract. 2022, 23, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Alakrash, H.M.; Abdul Razak, N. Technology-based language learning: Investigation of digital technology and digital literacy. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teras, H.; Kartoglu, U. Authentic learning with technology for professional development in vaccine management. Australas. J. Educ. Technol. 2018, 34, 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.T.N.; Johnson, N.F.; McAlinden, M. Exploring the Potential of VR in Enhancing Authentic Learning for EFL Tertiary Students in Vietnam. Teach. Engl. Technol. 2023, 23, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Hashim, M.H.; Tasir, Z. An e-learning environment embedded with sign language videos: Research into its usability and the academic performance and learning patterns of deaf students. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 2020, 68, 2873–2911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).