A Multistage Manufacturing Process Path Planning Method Based on AEC-FU Hybrid Decision-Making

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

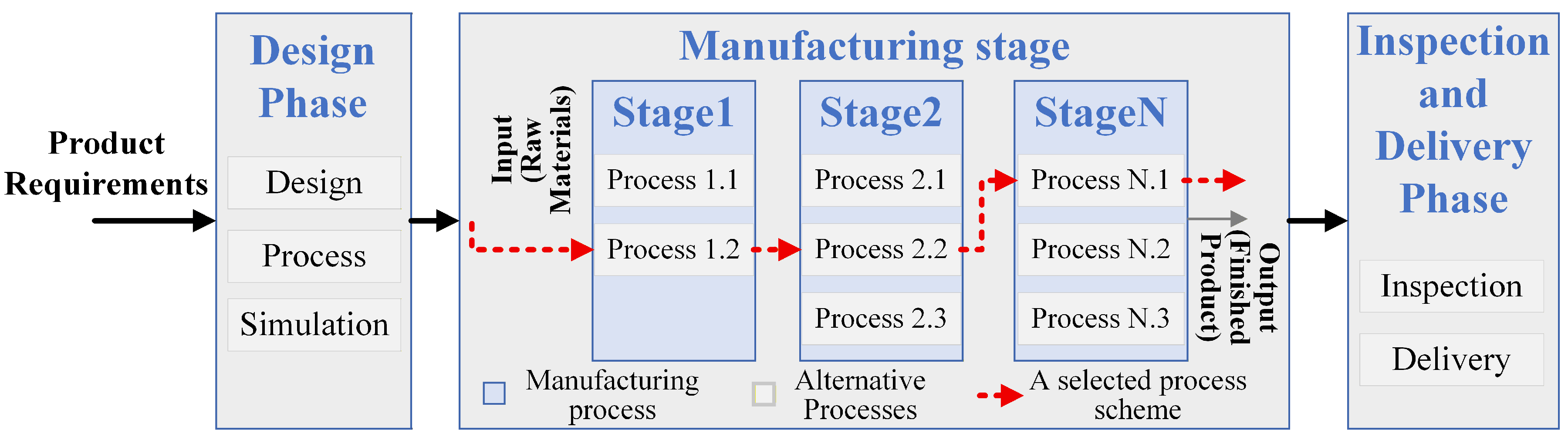

3. Problem Description

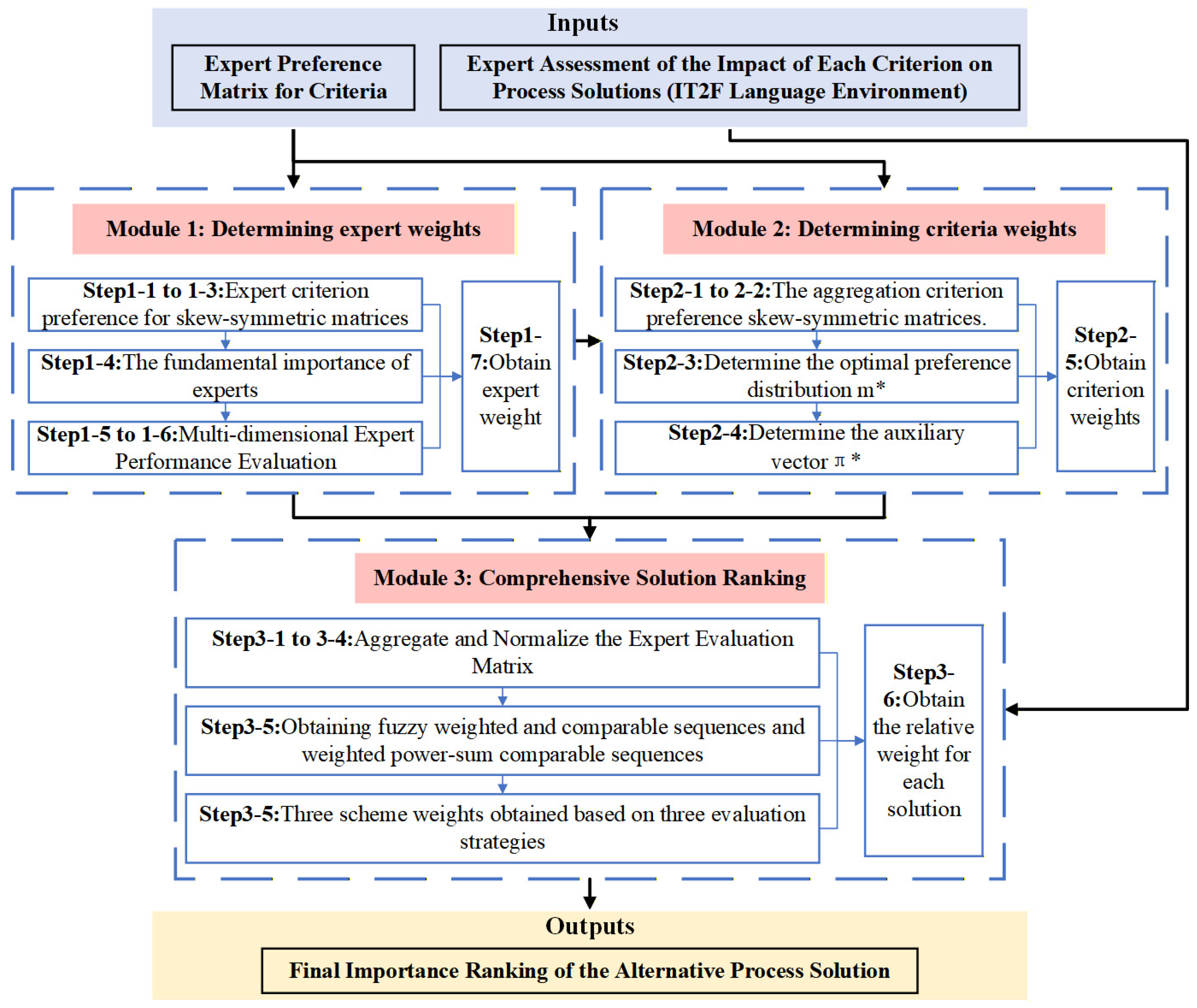

4. Methodology

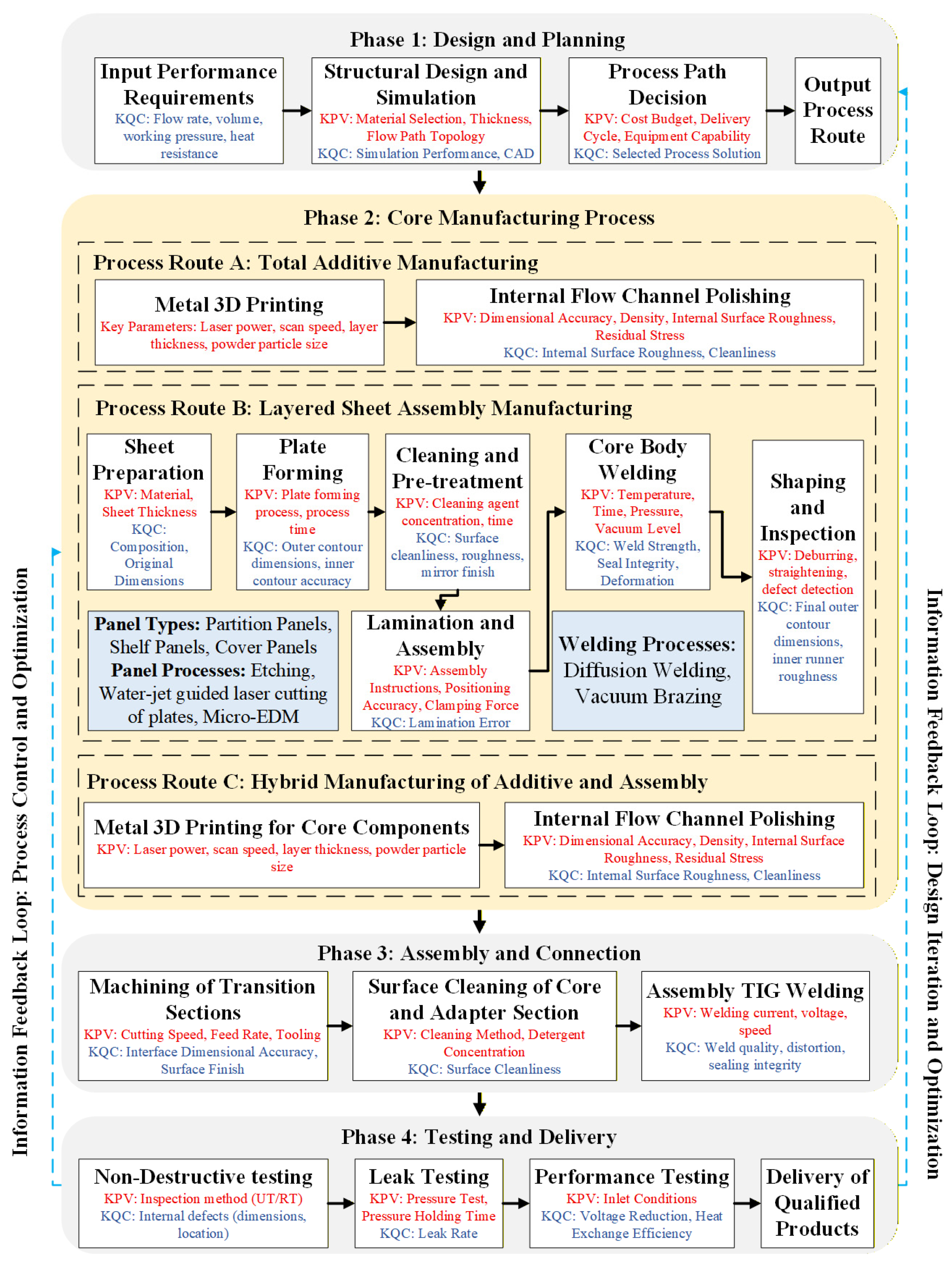

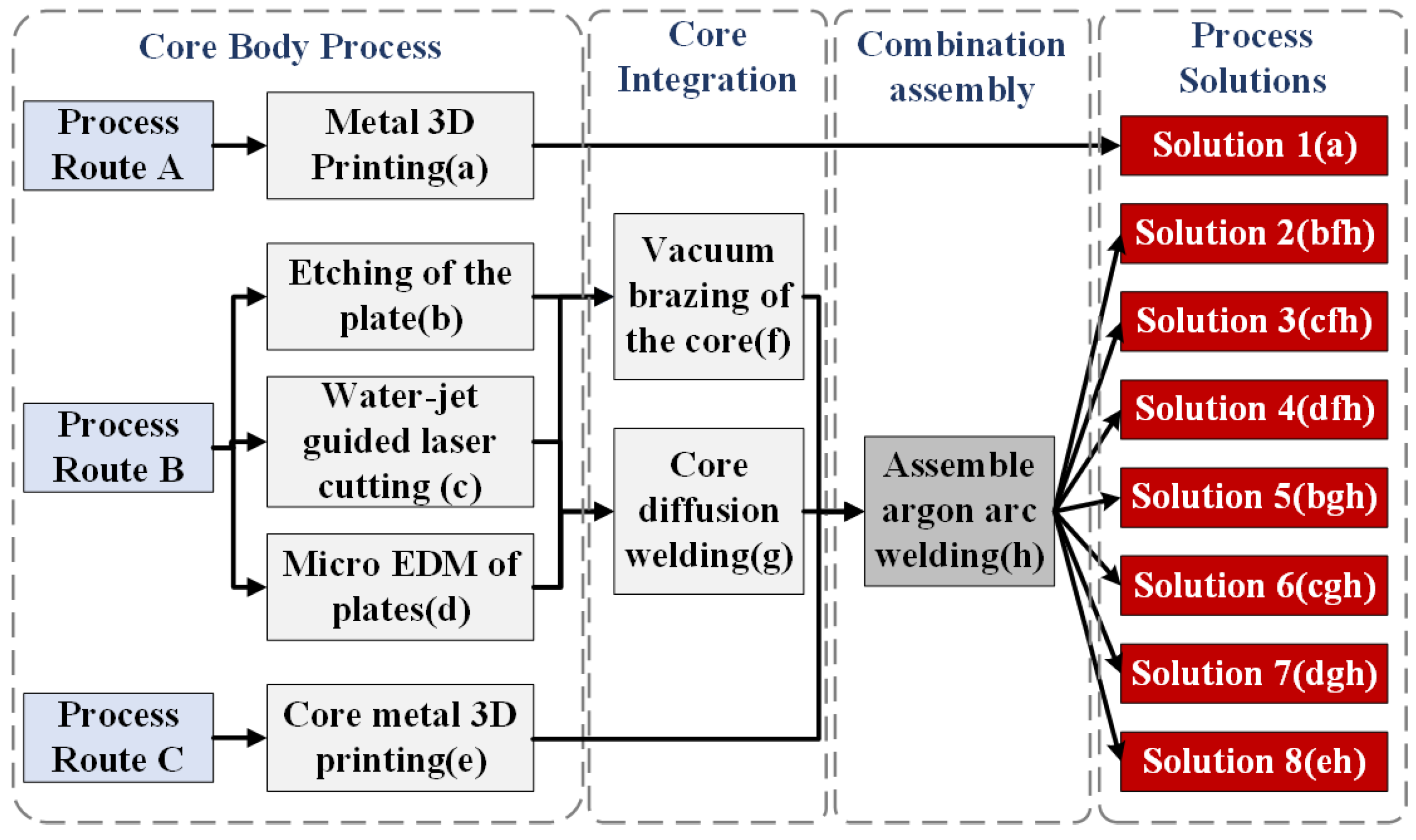

5. Case Study

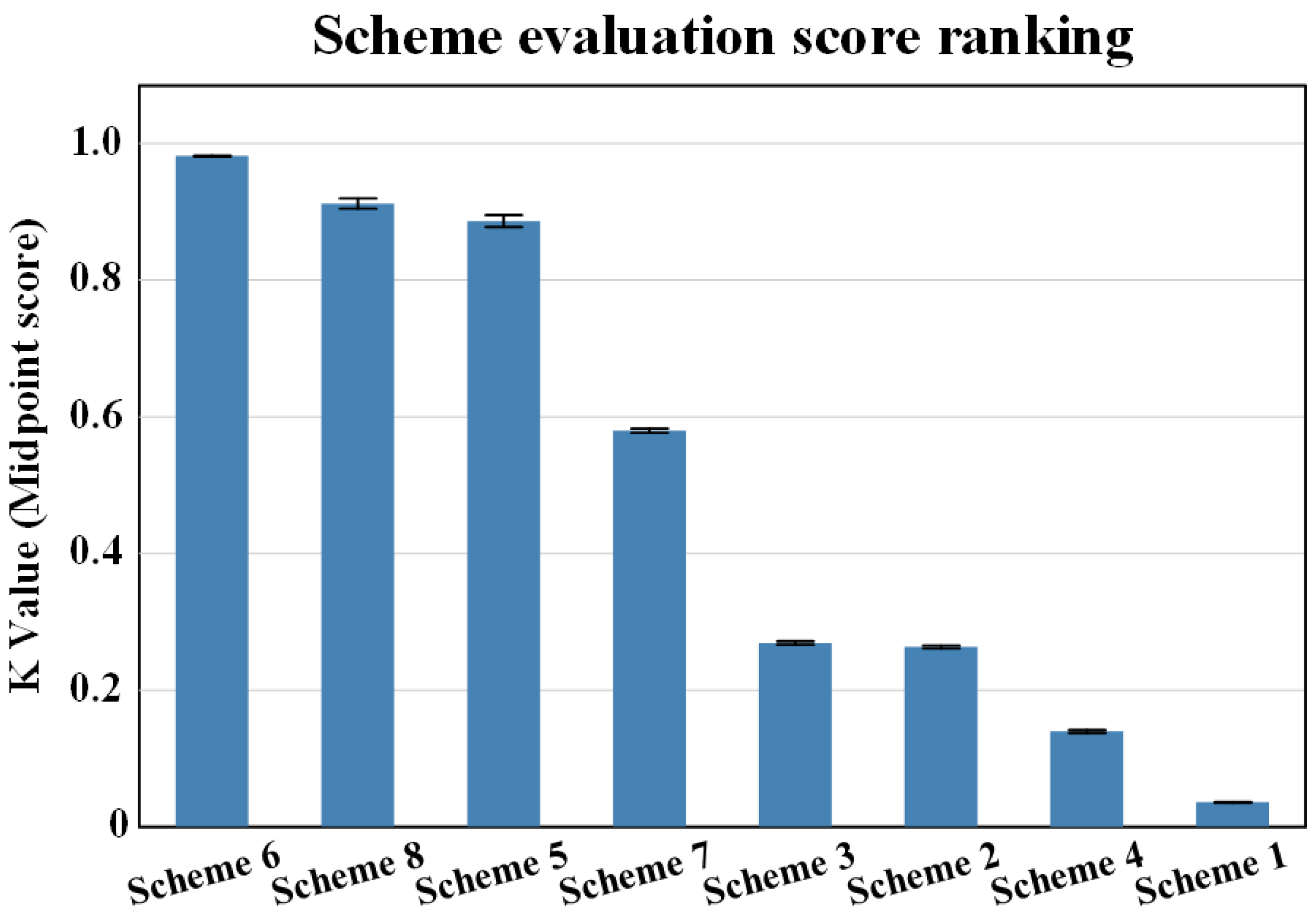

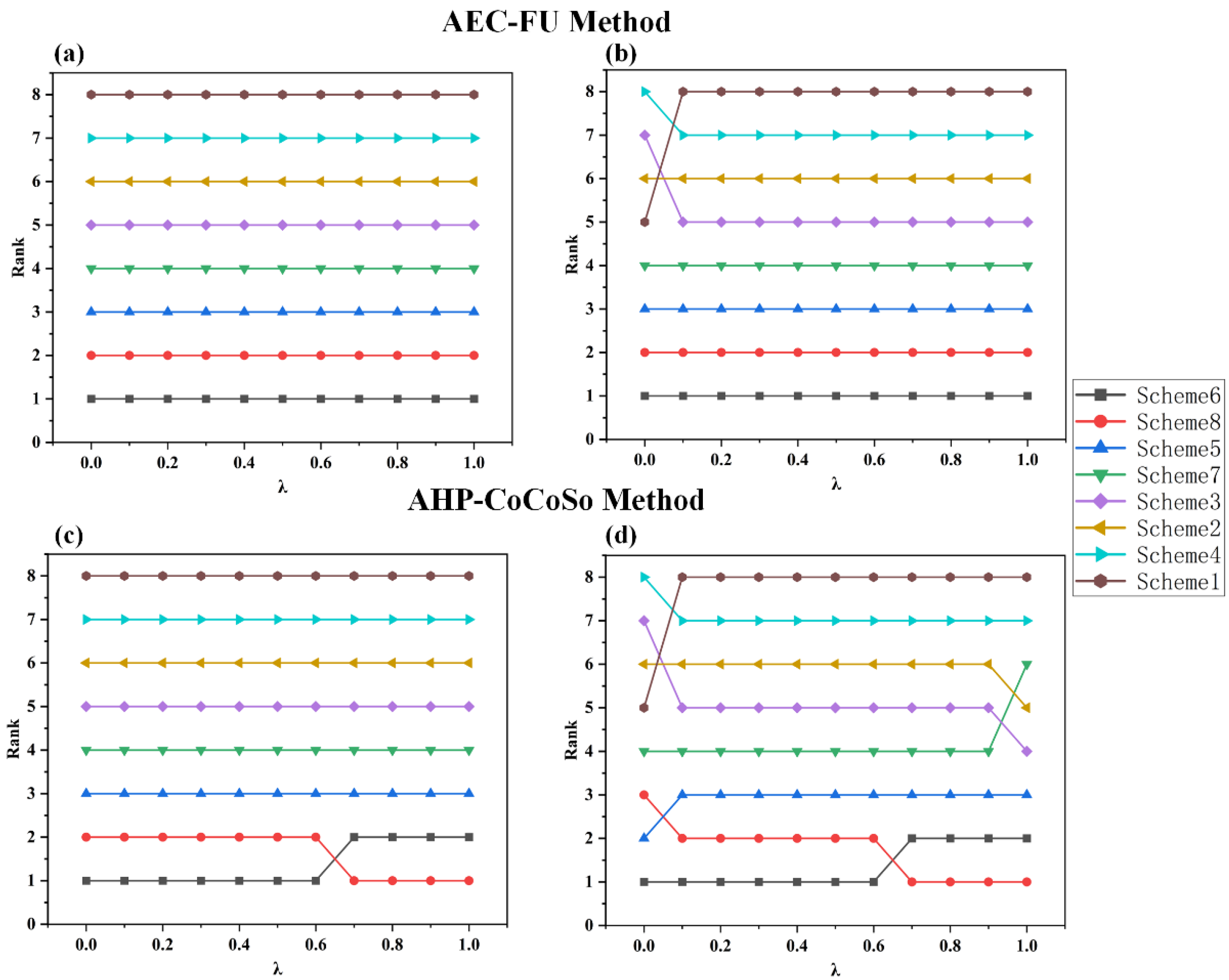

5.1. Sensitivity Analysis

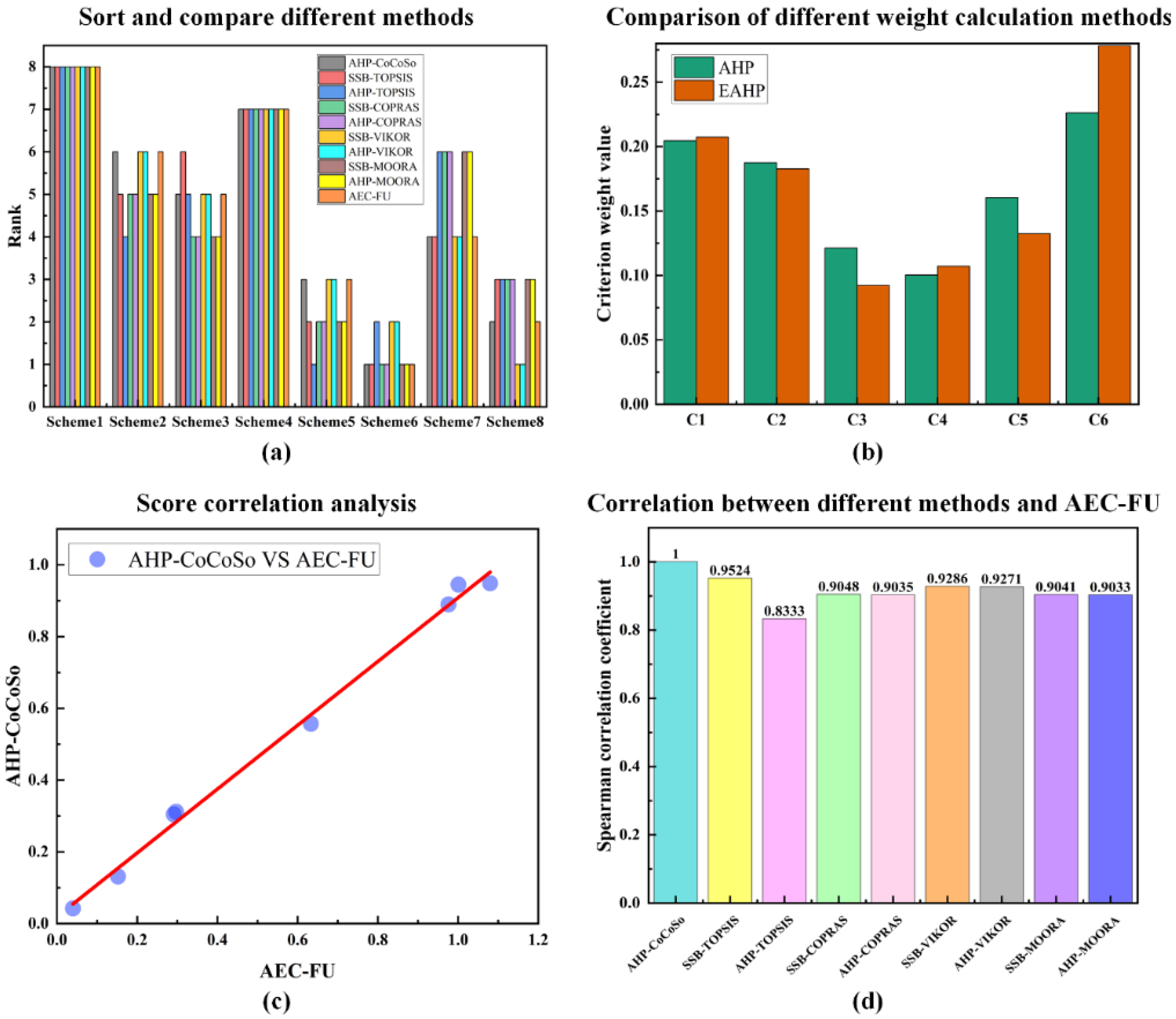

5.2. Comparative Analysis

6. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AEC-FU | AHP-Enhanced CoCoSo with Fuzzy Uncertainty |

| MMPs | Multistage Manufacturing Processes |

| EAHP | Enhanced AHP |

| CoCoSo | Combined Compromise Solution |

| IT2FS | Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Sets |

| MCDM | Multi-Criteria Decision Making |

| KPVs | Key Process Variables |

| KQCs | Key Quality Characteristics |

References

- Wang, P.; Qu, H.; Zhang, Q.; Xu, X.; Yang, S. Production quality prediction of multistage manufacturing systems using multi-task joint deep learning. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 70, 48–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, M.H.B.; Szejka, A.L.; Mas, F. Intelligent systems applied to anomaly detection and diagnosis in product design and manufacturing: Aerospace industry case study. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2025, 137, 5789–5807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Xu, R.; Huang, D.; Yao, X. Markov modeling and analysis of multi-stage manufacturing systems with remote quality information feedback. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2015, 88, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Maske, H.; Shui, H.; Upadhyay, D.; Hopka, M.; Cohen, J. Stochastic deep koopman model for quality propagation analysis in multistage manufacturing systems. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 71, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.-H.; Kim, S.-H.; Kim, K.-J. Multistage MR-CART: Multiresponse optimization in a multistage process using a classification and regression tree method. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 159, 107513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Yao, X.; Huang, D. Engineering model-based bayesian monitoring of ramp-up phase of multistage manufacturing process. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 4594–4613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, H.; Kim, K.; Yoon, K.; Chun, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, K.; Lee, J.; Lim, C. MMP net: A feedforward neural network model with sequential inputs for representing continuous multistage manufacturing processes without intermediate outputs. IISE Trans. 2024, 56, 1058–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Wang, H.; Guo, X.; Zhang, Q.; Zeng, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, K. Problem driven innovation design strategies research for product manufacturing process. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 14061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, B.; Xu, Z.; Qin, Y.; Philip Chen, C.L. An exploration of deep learning for decision making: Methods, applications, and challenges. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 289, 128406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahajan, A.; Singh, I.; Arora, N. CompoCraft: An expert system for process selection in sustainable composites. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 310, 113032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gradl, P.; Tinker, D.C.; Park, A.; Mireles, O.R.; Garcia, M.; Wilkerson, R.; Mckinney, C. Robust metal additive manufacturing process selection and development for aerospace components. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2022, 31, 6013–6044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumali, F.; Kałkowska, J. Intelligent support in manufacturing process selection based on artificial neural networks, fuzzy logic, and genetic algorithms: Current state and future perspectives. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 193, 110272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, M.; Aouag, H.; Anass, C.; Mouss, M.D. Development of an advanced application process of lean manufacturing approach based on a new integrated MCDM method under pythagorean fuzzy environment. J. Clean Prod. 2023, 386, 135731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, X.; Melkote, S. Automated manufacturability analysis and machining process selection using deep generative model and siamese neural networks. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 67, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, S.; Oh, Y. Optimal process planning for hybrid additive–subtractive manufacturing using recursive volume decomposition with decision criteria. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 71, 360–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Wei, J.; He, Y.; Rong, X.; Guo, W.; Wang, F.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J. A process strategy planning of additive-subtractive hybrid manufacturing based multi-dimensional manufacturability evaluation of geometry feature. J. Manuf. Syst. 2023, 67, 296–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Yan, X.; Bjorni, J.; Dinar, M.; Melkote, S.; Rosen, D. Manufacturing process selection based on similarity search: Incorporating non-shape information in shape descriptor comparison. J. Intell. Manuf. 2025, 36, 2509–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Jiang, Q.; Han, Y.; Wang, T.; He, Q. Knowledge graph-driven decision support for manufacturing process: A graph neural network-based knowledge reasoning approach. Adv. Eng. Inf. 2025, 64, 103098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussong, M.; Ruediger-Flore, P.; Klar, M.; Kloft, M.; Aurich, J.C. Selection of manufacturing processes using graph neural networks. J. Manuf. Syst. 2025, 80, 176–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, N.; Xu, B. Fuzzy hybrid technology in manufacturing and management, used to optimize decision-making and operational efficiency. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gangwar, S.; Saxena, P.; Virmani, N.; Biermann, T.; Steinnagel, C.; Lachmayer, R. Selection of a suitable additive manufacturing process for soft robotics application using three-way decision-making. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 132, 2003–2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, A.-D.; He, Z.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Ma, Y. A multi-objective evolutionary algorithm with mutual-information-guided improvement phase for feature selection in complex manufacturing processes. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2025, 323, 952–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, F.A.; Devriendt, H.; Metin, H.; Özer, M.; Naets, F. Physics-informed digital twin design for supporting the selection of process settings in continuous manufacturing, with a focus in fiberboard production. Comput. Ind. 2025, 168, 104267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baby, M.; Nellippallil, A.B. An information-decision framework for the multilevel co-design of products, materials, and manufacturing processes. Adv. Eng. Inf. 2024, 59, 102271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Chen, C. Application and research of intelligent temperature control system based on deep learning in precision manufacturing product design. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2025, 57, 103185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khani, M.; Ghazi, R.; Nazari, B. An unsupervised learning based MCDM approach for optimal placement of fault indicators in distribution networks. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 125, 106751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.-S.; Zhou, A.; Shen, S.-L. Safety assessment of excavation system via TOPSIS-based MCDM modelling in fuzzy environment. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 138, 110206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Jaisankar, R.; Murugesan, V.; Suvitha, K.; Narayanamoorthy, S. A novel MCDM approach to selecting a biodegradable dynamic plastic product: A probabilistic hesitant fuzzy set-based COPRAS method. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 340, 117967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimi, M.; Thanh, H.V.; Ebrahimzade, I.; Abbaspour-Fard, M.H.; Rohani, A. A multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) approach to determine the synthesizing routes of biomass-based carbon electrode material in supercapacitors. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 397, 136606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltan, H.; Janada, K.; Omar, M. FAQT-2: A customer-oriented method for MCDM with statistical verification applied to industrial robot selection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 226, 120106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, J.; Zhong, S.; Tian, M.; Liu, Y. Combining fuzzy MCDM with kano model and FMEA: A novel 3-phase MCDM method for reliable assessment. Ann. Oper. Res. 2024, 342, 725–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, A.K.; Kumar, Y.; Kumar, S.; Raja, A.R. Parametric optimization of AWJM using RSM-grey-TLBO-based MCDM approach for titanium grade 5 alloy. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2024, 50, 13693–13711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dere, S.; Elçin Günay, E.; Kula, U.; Kremer, G.E. Assessing agrivoltaics potential in türkiye—A geographical information system (GIS)-based fuzzy multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) approach. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 197, 110598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atif, M.; Junejo, F.; Amin, I. Development of a framework for sustainability assessment of the machining process through machining parameter optimisation technique. Int. J. Sustain. Eng. 2024, 17, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfan, S.; Alamoodi, A.H.; Sulaiman, S.; Albahri, O.S.; Albahri, A.S.; Sharaf, I.M. Multicriteria decision-making framework for robust energy management AI solutions. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 100822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Z.; Zhang, X. An integrated decision support system for supplier selection and performance evaluation in global supply chains. Appl. Soft Comput. 2025, 180, 113325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi, N.; Schuelke-Leech, B.-A.; Mirhassani, M. Enhanced TARA model for heavy-duty vehicles using ISO/SAE 21434 and fuzzy analytic hierarchy process (FAHP). Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 291, 128441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Zhang, Y.; Jing, F. Fault diagnosis of hot rolling equipment under uncertain conditions based on cloud rough model, game theory, and improved GRA-TOPSIS. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2025, 18, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rishabh, R.; Das, K.N. A decomposed fuzzy based fusion of decision-making and metaheuristic algorithm to select best unmanned aerial vehicle in agriculture 4.0 era. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 159, 111491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Gou, Z.; Chau, H.-W. A decision framework for multi-dimensional analysis of roof retrofit scenarios to mitigate urban heat island effects and enhance energy efficiency. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 130, 106591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zegai, R.; Khettabi, I.; Benyoucef, L.; Abbas, M. Enhancing collaborative multi-criteria group decision-making in supply chains: A probabilistic-based approach using SFNs and CoCoSo. Int. J. Fuzzy Syst. 2025, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.-H.; He, S.-F.; Wang, Y.-M.; Martínez, L. An ExpTODIM based multi-criteria sorting method under uncertainty. Inf. Fusion 2026, 125, 103519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-R.; Liu, F.; Mo, J.-T. Decision making based on AND-logical quantification of uncertainty in pairwise comparisons. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 2025, 16, 2335–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamal, A.; Abdel-Basset, M.; Hezam, I.; Sallam, K.; Alshamrani, A. A computational sustainable approach for energy storage systems performance evaluation based on spherical-fuzzy MCDM with considering uncertainty. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 1319–1341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hezam, I.; Al, A.; Sallam, K. An efficient decision-making model for evaluating irrigation systems under uncertainty: Toward integrated approaches to sustainability. Agric. Water Manag. 2024, 303, 109034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, X.; Xu, K.; Li, Z.; Jin, L.; Tian, D.; Zhao, B. A novel framework for optimal selection of vector-valued intensity measures under mainshock-aftershock sequences considering uncertainties and multi-criteria correlation. Soil Dyn. Earthq. Eng. 2025, 198, 109655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.; Liu, J.; Liu, X.; Meng, Z.; Pu, M.; Wu, H.; Yan, X.; Yang, G.; Zhang, X.; Chen, C.; et al. An integrated MCDM model with enhanced decision support in transport safety using machine learning optimization. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2024, 301, 112286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alrashdi, I.; Ali, A.; Sallam, K.; Abdel-Basset, M. Assessment and analysis of development risks under uncertainty: The impact of disruptive technologies on renewable energy development. Energy Nexus 2025, 17, 100371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafari, M.; Naghdi Khanachah, S. Integrated knowledge management in the supply chain: Assessment of knowledge adoption solutions through a comprehensive CoCoSo method under uncertainty. J. Ind. Inf. Integr. 2024, 39, 100581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpitella, S.; Kratochvíl, V.; Pištěk, M. Multi-criteria decision making beyond consistency: An alternative to AHP for real-world industrial problems. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2024, 198, 110661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Zhou, L.; Chen, Y.; Chen, H. An integrated approach to green supplier selection based on the interval type-2 fuzzy best-worst and extended VIKOR methods. Inf. Sci. 2019, 502, 394–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, B.; Wan, M.; Zhao, R.; Zou, Z.; Liu, H. Micromanufacturing technologies of compact heat exchangers for hypersonic precooled airbreathing propulsion: A review. Chin. J. Aeronaut. 2021, 34, 79–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebbor, I.; Benmamoun, Z.; Hachimi, H. Leveraging digital twins and metaverse technologies for sustainable circular operations: A comprehensive literature review. Circ. Econ. Sustain. 2025, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebbor, I.; Raouf, Y.; Benmamoun, Z.; Hachimi, H. Process improvement of taping for an assembly electrical wiring harness. In Industrial Engineering and Applications—Europe. ICIEA-EU 2024; Sheu, S.H., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Business Information Processing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 507. [Google Scholar]

- Saaty, R.W. The analytic hierarchy process—What it is and how it is used. Math. Modell. 1987, 9, 161–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazdani, M.; Zaraté, P.; Kazimieras Zavadskas, E.; Turskis, Z. A combined compromise solution (CoCoSo) method for multi-criteria decision-making problems. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 2501–2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmamoun, Z.; Khlie, K.; Agarwal, V.; Jebbor, I.; Jha, C.K.; El Kadi, H. A multicriteria risk management model for agri-food industrial companies. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.E.B.; Lima-Junior, F.R.; Galo, N.R. A comparison of hesitant fuzzy VIKOR methods for supplier selection. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 149, 110920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H.; Madanchian, M. Multi-criteria decision making (MCDM) methods and concepts. Encyclopedia 2023, 3, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotoudeh-Anvari, A. The applications of MCDM methods in COVID-19 pandemic: A state of the art review. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 126, 109238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author | Problem | Method |

|---|---|---|

| Khani et al. [26] | Optimal Placement of Fault Indicators | AHP + EPSO |

| Lin et al. [27] | Excavation Project Risk Identification | SFS + TOPSIS |

| Kang et al. [28] | Biodegradable Plastic Product Selection | CRITIC + COPRAS |

| Rahimi et al. [29] | Synthesis Routes for Electrode Materials | TOPSIS |

| Soltan et al. [30] | Industrial Robot Selection | AHP + QFD + TOPSIS |

| Shao et al. [31] | Hydrogen Storage Solution Assessment | AHP + Kano + FMEA + TOPSIS |

| Dubey et al. [32] | Titanium Alloy Process Parameter Optimization | RSM + GRA + TLBO |

| Dere et al. [33] | Agricultural Photovoltaic Site Selection | FAHP + TOPSIS |

| Atif et al. [34] | Cast Iron Processing Evaluation | GRA + multi-objective optimization |

| Garfan et al. [35] | Energy Management Systems | FWZIC + CODAS |

| Xiang and Zhang [36] | Supplier Selection | CIMAS + LOPCOW + ERUNS |

| Rahimi et al. [37] | Heavy Vehicle Risk Assessment | FAHP |

| Hu et al. [38] | Equipment Fault Diagnosis | CRITIC + GRA − TOPSIS |

| Rishabh and Das [39] | Agricultural Drone Selection | DFNL − AHP + SS − PSO |

| Yang et al. [40] | Roof Conversion | TOPSIS |

| Zegai et al. [41] | Supply Chain Group Decision-Making | CRITIC + SFNs + CoCoSo |

| Symbol | Representation |

|---|---|

| Language Expression | Abbreviation | IT2FS Number |

|---|---|---|

| Poor | P | ((0, 0, 1, 3; 1, 1), (0, 0, 0.5, 2; 0.9, 0.9)) |

| Medium-Poor | MP | ((1, 3, 3, 5; 1, 1), (2, 3, 3, 4; 0.9, 0.9)) |

| Medium | M | ((3, 5, 5, 7; 1, 1), (4, 5, 5, 6; 0.9, 0.9)) |

| Medium-Good | MG | ((5, 7, 7, 9; 1, 1), (6, 7, 7, 8; 0.9, 0.9)) |

| Good | G | ((7, 9, 10, 10; 1, 1), (8, 9.5, 10, 10; 0.9, 0.9)) |

| Corporate Criteria | Description | Number |

|---|---|---|

| Design and technical specifications (%) | Technical core to meet product design requirements and key performance indicators | |

| Production process and equipment capacity (%) | Whether the qualified products can be manufactured in accordance with the design requirements, and the production efficiency of the products | |

| Budget costs (ten thousand RMB) | Expected development cost and production cost | |

| Customer feedback and after-sales (%) | Expected customer after-sales demand probability after product delivery | |

| Expected delivery time (hours) | Expected development time, production time, and quality inspection time | |

| Quality control (%) | The expected rework rate during the production process |

| Corporate Criteria | Mapping Mechanism | Specific Indicators in Figure 3 |

|---|---|---|

| : Design and technical specifications | Evaluate complex geometries and precision requirements through Key Process Variables (KPVs). | Laser power, scan speed, layer thickness (Route A); etching precision, Micro-EDM accuracy (Route B). |

| : Production process and equipment capacity | Evaluated based on the maturity and stability of the core forming and joining technologies. | Equipment capability for Metal 3D printing; stability of diffusion welding and vacuum brazing processes. |

| : Budget costs | Calculated based on material consumption rates, energy usage of equipment, and tooling costs. | Powder usage efficiency (Routes A and C); Cost of cleaning agents; tooling wear in machining transition sections. |

| : Customer feedback and after-sales | Projected based on historical reliability data of similar processes and potential defect rates. | Probability of internal defects: porosity in printing (Routes A and C), misalignment rate of laminated assemblies (Routes B). |

| : Expected delivery time | Calculated by summing the processing cycles of individual steps and post-processing duration. | Comparison of long printing cycles (Route A) vs. parallel batch processing times (Route B: etching, stamping). |

| : Quality control | Key Quality Characteristics (KQCs) that directly cause product rework. | Internal surface roughness, lamination error, weld strength, seal integrity, leak rate, and heat exchange efficiency. |

| : Designer Manager | : Production Director | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 0.07 | 1 | 1/5 | 3 | 4 | 1/4 | 1/4 | 0.131 | ||

| 1/4 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 1/3 | 5 | 1 | 7 | 8 | 2 | 4 | ||||

| 1/7 | 1/5 | 1 | 1/3 | 1/2 | 1/6 | 1/3 | 1/7 | 1 | 2 | 1/6 | 1/4 | ||||

| 1/5 | 1/3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1/4 | 1/4 | 1/8 | 1/2 | 1 | 1/7 | 1/5 | ||||

| 1/6 | 1/2 | 2 | 1/2 | 1 | 1/5 | 4 | 1/2 | 6 | 7 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| 1/2 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 1/4 | 4 | 5 | 1/3 | 1 | ||||

| : Project Manager | : Quality Manager | ||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 1/5 | 1/2 | 1/4 | 1 | 0.11 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 1/2 | 0.089 | ||

| 1/2 | 1 | 1/6 | 1/4 | 1/5 | 1/2 | 1/2 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 1/4 | ||||

| 5 | 6 | 1 | 1/2 | 2 | 4 | 1/7 | 1/5 | 1 | 1/3 | 4 | 1/8 | ||||

| 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 1/2 | 2 | 1/5 | 1/3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1/6 | ||||

| 4 | 5 | 1/2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1/7 | 1/5 | 1/4 | 1/3 | 1 | 1/8 | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 1/4 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 1 | ||||

| Expert | Expert Weights | |

|---|---|---|

| 4.77 | 0.31 | |

| 6.95 | 0.24 | |

| 8.78 | 0.18 | |

| 5.82 | 0.27 |

| Aggregated Pairwise Comparison Matrix | Aggregated Skew-Symmetric Matrix | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.43 | 3.00 | 3.12 | 1.65 | 0.73 | 0 | 0.36 | 1.10 | 1.14 | 0.50 | −0.31 | ||

| 0.69 | 1 | 2.93 | 2.42 | 1.69 | 0.59 | −0.36 | 0 | 1.07 | 0.88 | 0.53 | −0.31 | ||

| 0.33 | 0.34 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.87 | 0.30 | −1.10 | −1.07 | 0 | −0.59 | −0.14 | −1.19 | ||

| 0.32 | 0.41 | 1.82 | 1 | 0.93 | 0.31 | −1.14 | −0.88 | 0.59 | 0 | −0.08 | −1.17 | ||

| 0.61 | 0.59 | 1.15 | 1.08 | 1 | 0.55 | −0.50 | −0.53 | 0.14 | 0.08 | 0 | −0.60 | ||

| 1.36 | 1.67 | 3.31 | 3.23 | 1.83 | 1 | 0.31 | 0.51 | 1.19 | 1.17 | 0.60 | 0 | ||

| Criteria | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria Weights | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.28 |

| : Designer Manager | : Production Director | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | MG | P | M | MG | MG | P | M | P | M | G | MP | ||

| M | M | MG | M | M | M | G | MG | G | M | MG | M | ||

| M | M | M | M | M | M | G | G | MG | M | G | M | ||

| MG | MG | MP | M | MP | M | M | MP | MP | M | MP | M | ||

| M | MG | M | MG | M | G | M | M | M | M | M | MG | ||

| M | MG | MP | MG | M | G | M | MG | MP | M | MG | MG | ||

| MG | G | P | MG | MP | G | MP | P | P | M | P | MG | ||

| G | MG | MP | G | M | MG | MG | M | M | M | M | M | ||

| : Project Manager | : Quality Manager | ||||||||||||

| M | MP | P | G | G | MP | G | M | P | M | P | MG | ||

| MG | M | G | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | ||

| MG | MG | MG | M | MG | M | M | M | M | M | M | M | ||

| M | MP | MP | M | MP | M | MG | MG | MP | M | MP | M | ||

| M | M | M | MG | M | MG | MG | G | M | MG | M | G | ||

| M | MG | MP | MG | M | MG | MG | G | MP | MG | M | G | ||

| M | MP | P | MG | P | G | G | G | P | G | P | G | ||

| G | MG | MP | G | MG | MG | G | MG | MP | G | M | G | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chen, W.; Gao, X. A Multistage Manufacturing Process Path Planning Method Based on AEC-FU Hybrid Decision-Making. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13276. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413276

Chen W, Gao X. A Multistage Manufacturing Process Path Planning Method Based on AEC-FU Hybrid Decision-Making. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13276. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413276

Chicago/Turabian StyleChen, Wanlu, and Xinqin Gao. 2025. "A Multistage Manufacturing Process Path Planning Method Based on AEC-FU Hybrid Decision-Making" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13276. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413276

APA StyleChen, W., & Gao, X. (2025). A Multistage Manufacturing Process Path Planning Method Based on AEC-FU Hybrid Decision-Making. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13276. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413276