Evaluation of Maritime Safety Policy Using Data Envelopment Analysis and PROMETHEE Method

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

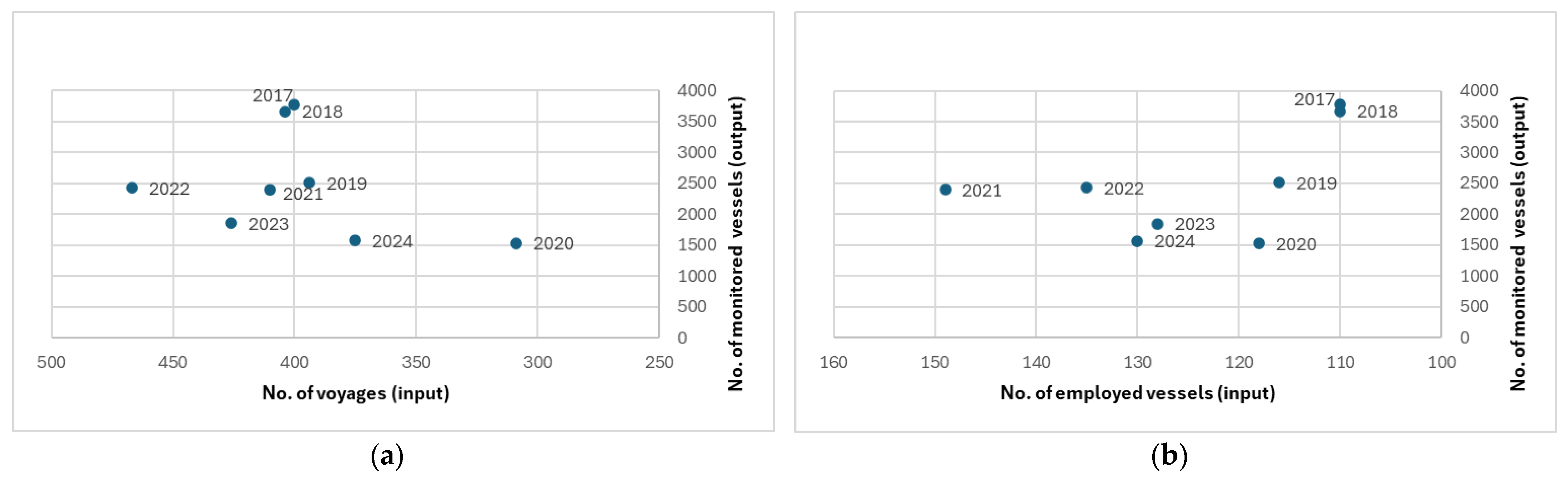

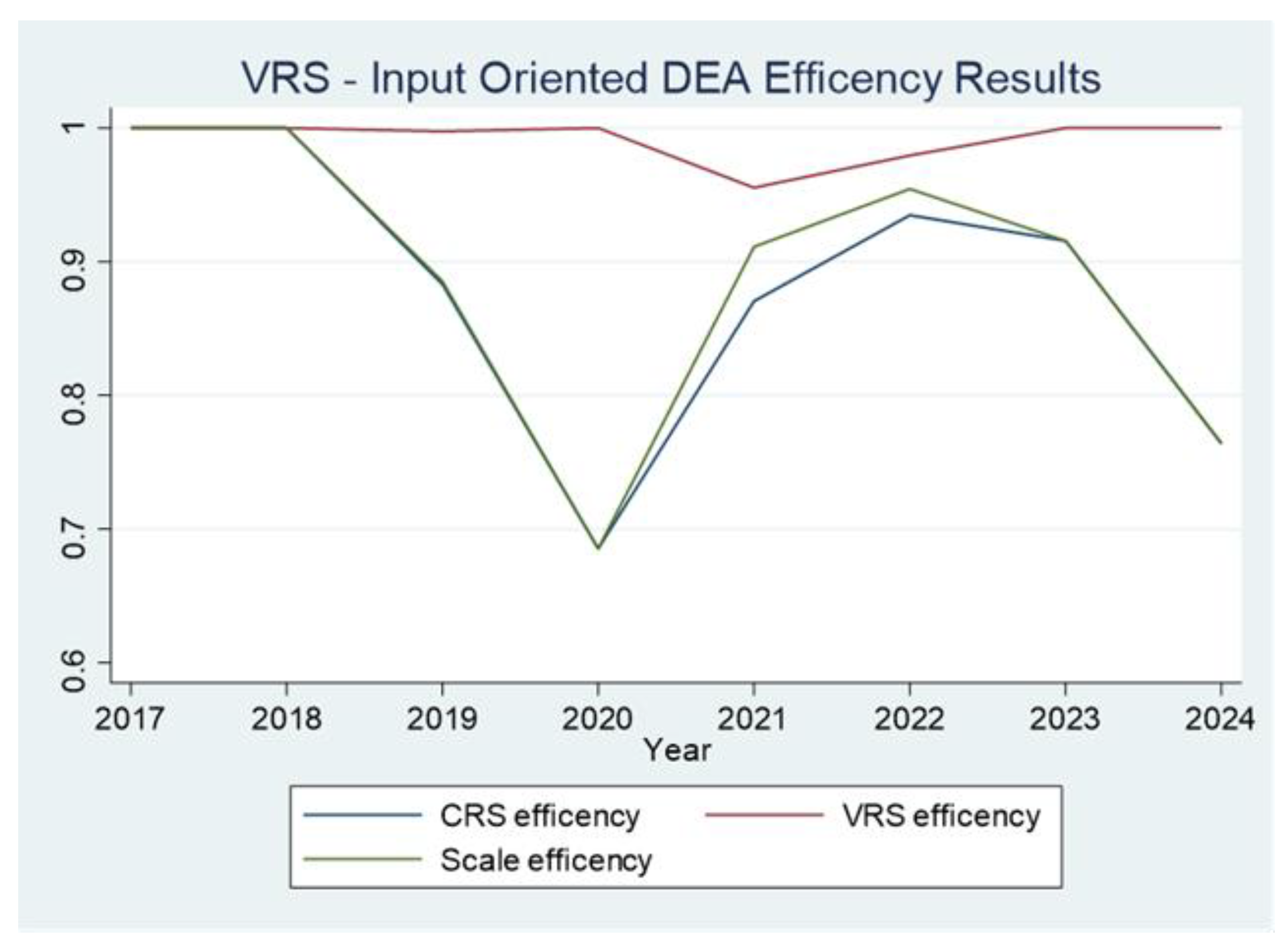

3.1. Results of the Input-Oriented DEA Model

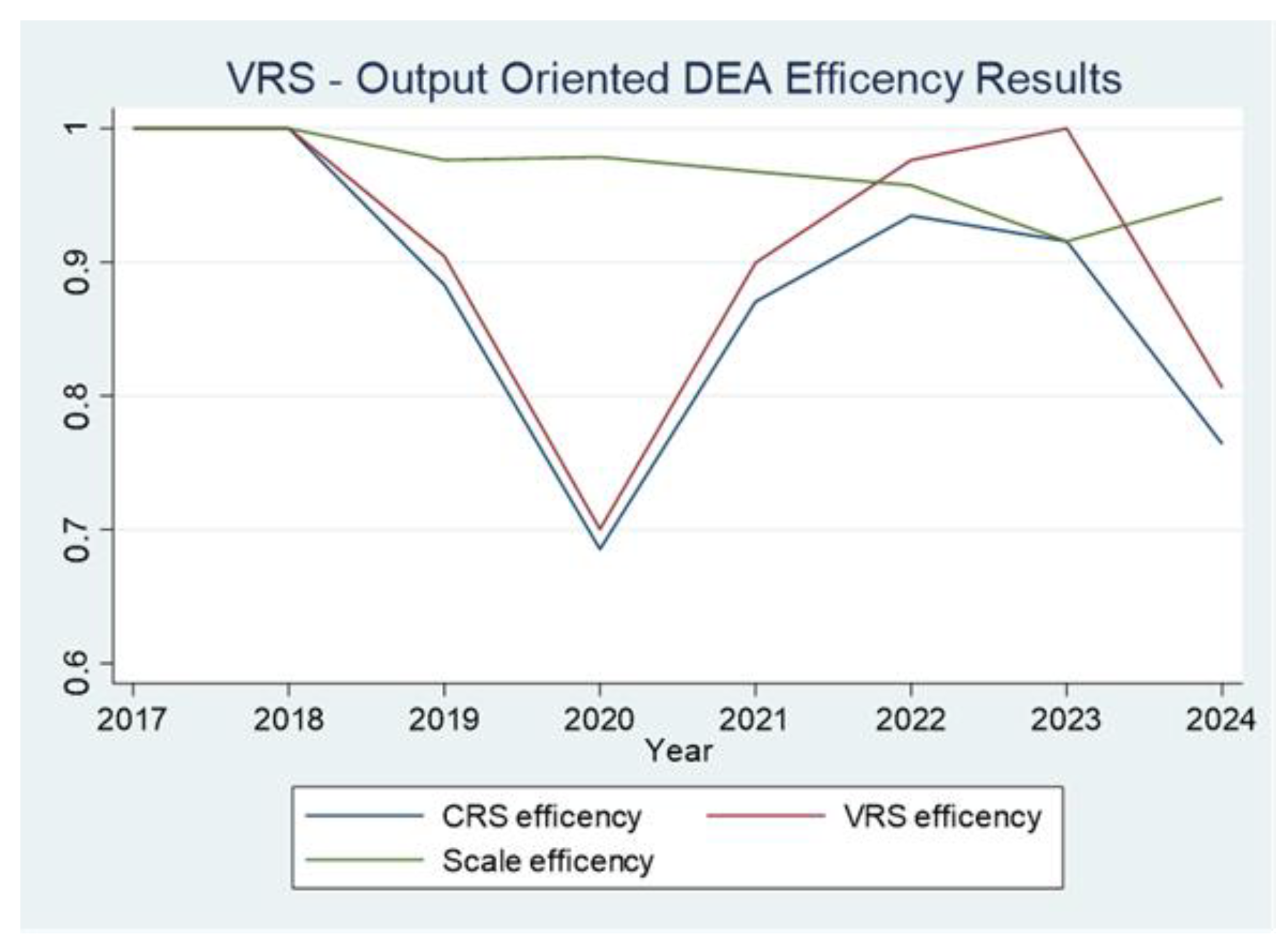

3.2. Results of the Output-Oriented DEA Model

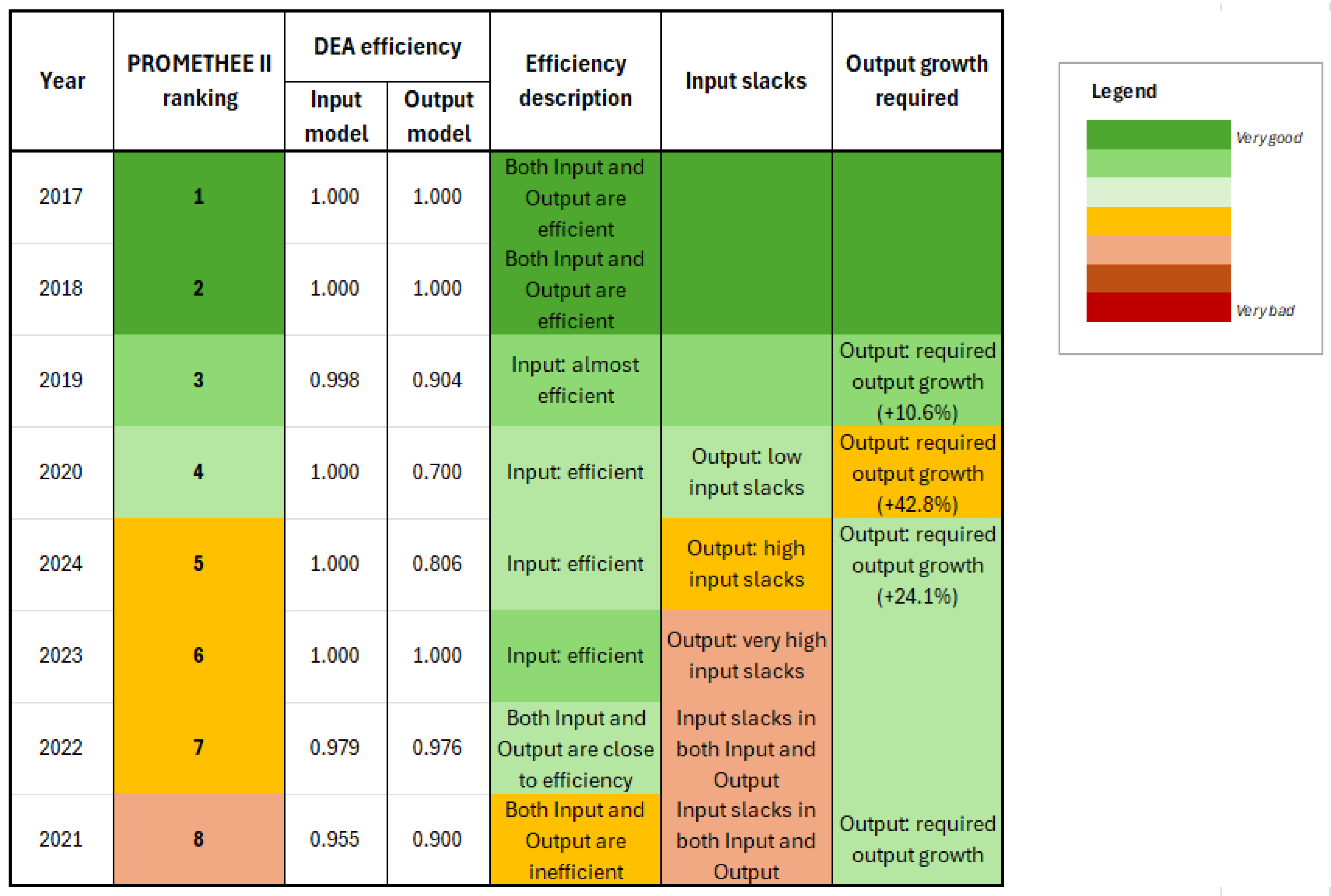

3.3. Comparison of the Results of the Input- and Output-Oriented DEA Models

4. Discussion

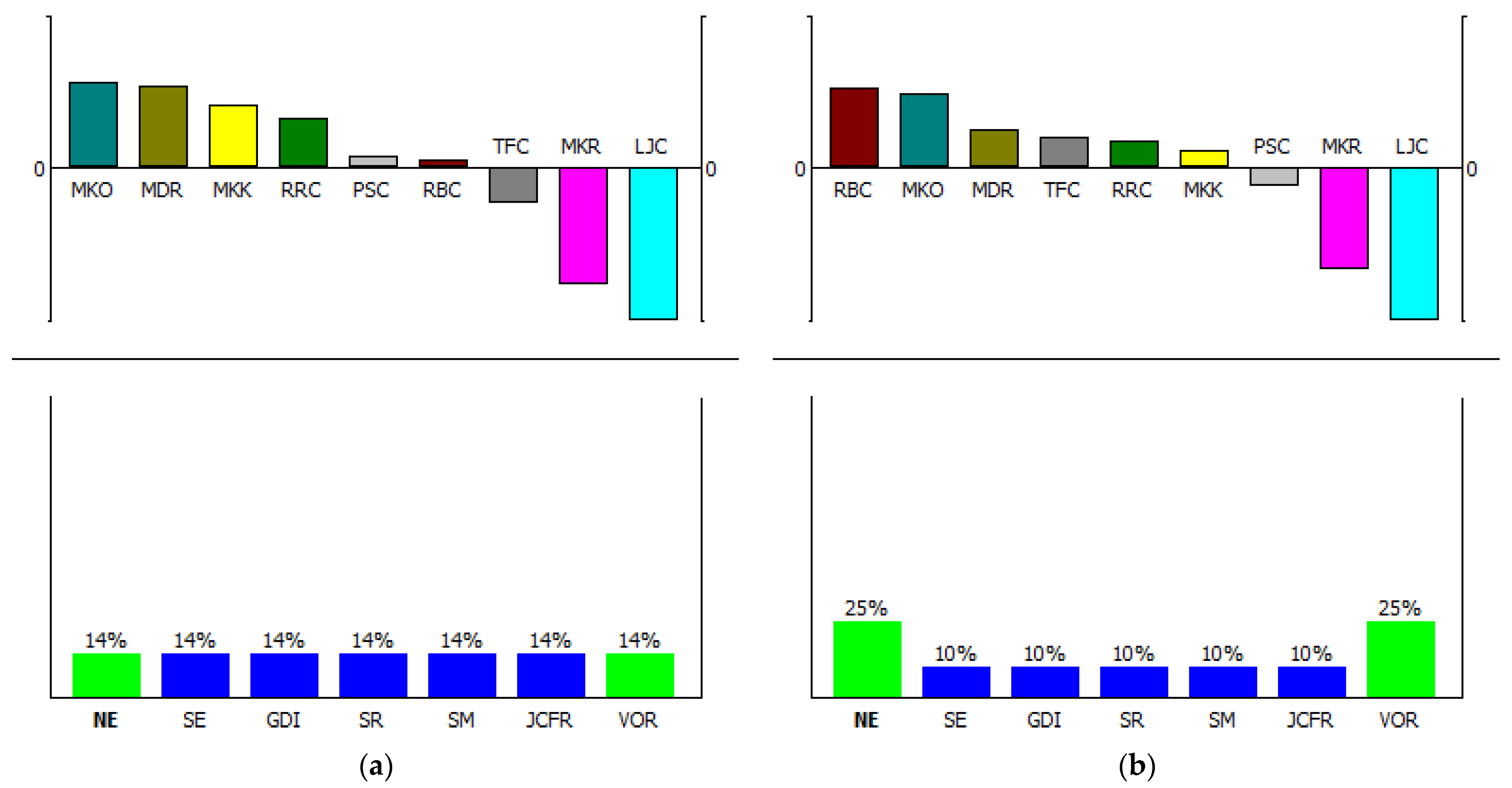

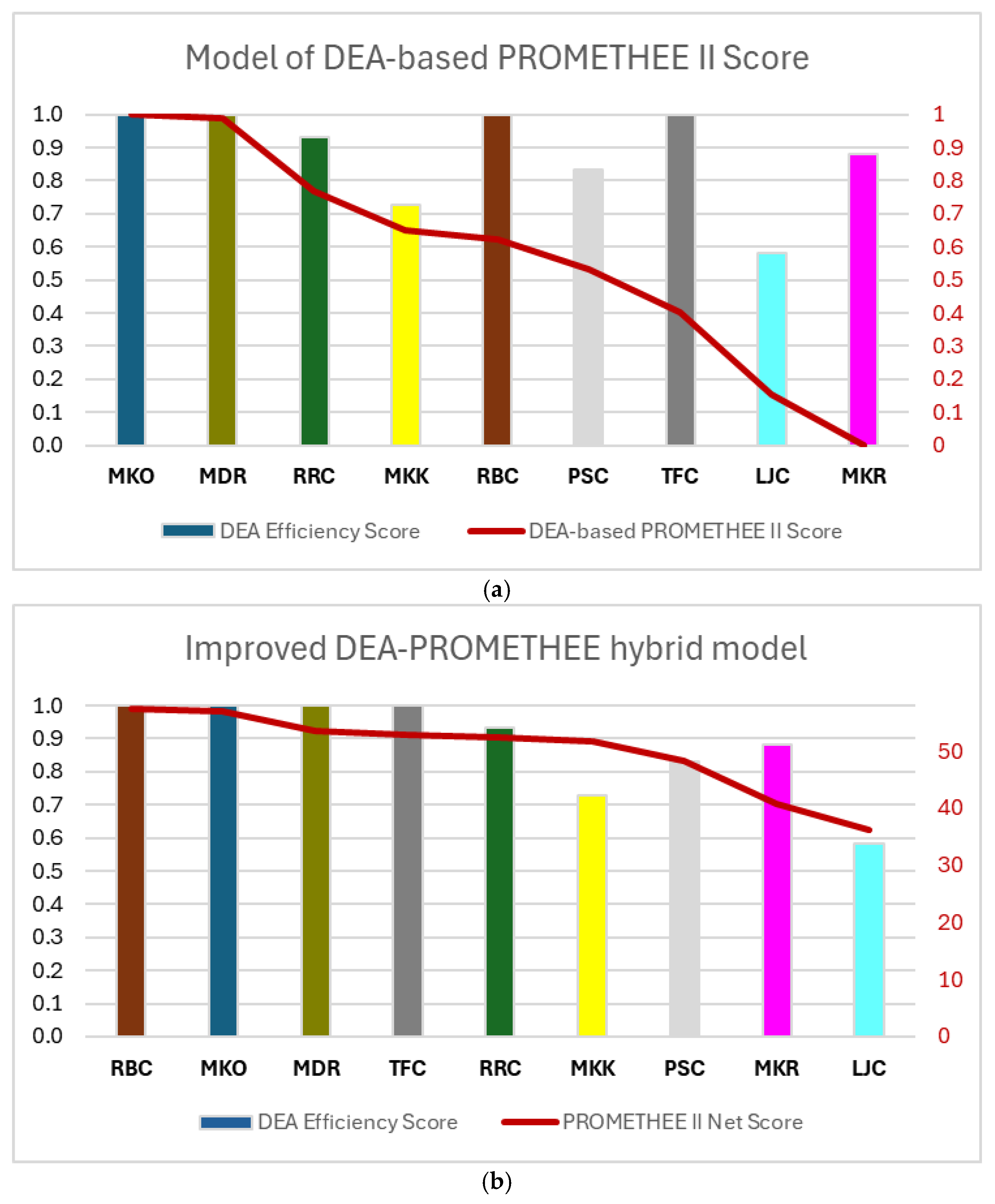

4.1. DEA Efficiency Interpretation Based on PROMETHEE Method

4.2. Comparison of DEA–PROMETHEE Hybrid Model with DEA-Based PROMETHEE II Approach

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khodamoradi, A.; Figueiras, P.A.; Grilo, A.; Lourenço, L.; Rêga, B.; Agostinho, C.; Costa, R.; Jardim-Gonçalves, R. Vessel Traffic Density Prediction: A Federated Learning Approach. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Cai, X.; Qiao, J.; Yang, J.-B. Integrated Modeling of Maritime Accident Hotspots and Vessel Traffic Networks in High-Density Waterways: A Case Study of the Strait of Malacca. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez Vázquez, R.M.; Milán García, J.; De Pablo Valenciano, J. Analysis and Trends of Global Research on Nautical, Maritime and Marine Tourism. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2021, 9, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Liu, J.; Yan, P.; Jiang, X. Research on the Impact of Deep Sea Offshore Wind Farms on Maritime Safety. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W.; Rhodes, E. Measuring the efficiency of decision-making units. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1978, 2, 429–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panwar, A.; Olfati, M.; Pant, M.; Snasel, V. A Review on the 40 Years of Existence of Data Envelopment Analysis Models: Historic Development and Current Trends. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2022, 29, 5397–5426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mergoni, A.; Emrouznejad, A.; De Witte, K. Fifty years of Data Envelopment Analysis. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2025, 326, 389–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R.D.; Charnes, A.; Cooper, W.W. Some models for estimating technical and scale inefficiencies in data envelopment analysis. Manag. Sci. 1984, 30, 1078–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.-H.; Nguyen, T.-L.; Nguyen, T.-G.; Nguyen, D.-T.; Tran, T.-H.; Le, H.-C.; Phung, H.-T. A Cross-Country European Efficiency Measurement of Maritime Transport: A Data Envelopment Analysis Approach. Axioms 2022, 11, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Lee, G.; Kim, H. Analysis of Operational Efficiency Considering Safety Factors as an Undesirable Output for Coastal Ferry Operators in Korea. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2020, 8, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, G.Y.; Lee, H.S.; Chung, C.C.; Chen, S.L. Performance evaluation of the security management of Changjiang maritime safety administrations: Application with undesirable outputs in Data Envelopment Analysis. J. Mar. Sci. Technol. 2017, 25, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.C. Adaptation of undesirable-output DEA for navigation safety in Taiwan international ports. Cogent Eng. 2021, 8, 1989998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, B.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Savan, E.E.; Yan, X. Effectiveness of maritime safety control in different navigation zones using a spatial sequential DEA model: Yangtze River case. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2015, 81, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brans, J.P.; Vincke, P.; Mareschal, B. How to select and how to rank projects: The PROMETHEE method. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 1986, 24, 228–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishizaka, A.; Resce, G.; Mareschal, B. Visual management of performance with PROMETHEE productivity analysis. Soft Comput. 2018, 22, 7325–7338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherikahvarin, M. A DEA-PROMETHEE approach for complete ranking of units. Int. J. Oper. Res. 2019, 35, 224–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagherikahvarin, M.; De Smet, Y. A ranking method based on DEA and PROMETHEE II (a rank based on DEA & PR.II). Measurement 2016, 89, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alidrisi, H. DEA-Based PROMETHEE II Distribution-Center Productivity Model: Evaluation and Location Strategies Formulation. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radfar, R.; Salahi, F. Evaluation and Ranking of Suppliers with Fuzzy DEA and PROMETHEE Approach. Int. J. Ind. Math. 2014, 6, 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Mladineo, N.; Mladineo, M.; Knezic, S. Web MCA-based Decision Support System for Incident Situations in Maritime Traffic: Case Study of Adriatic Sea. J. Navig. 2017, 70, 1312–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daugavietis, J.E.; Soloha, R.; Dace, E.; Ziemele, J. A Comparison of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis Methods for Sustainability Assessment of District Heating Systems. Energies 2022, 15, 2411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunko, T.; Mladineo, M.; Kovačić, M.; Mišković, T. Multi-Criteria Analysis of Coast Guard Resource Deployment for Improvement of Maritime Safety and Environmental Protection: Case Study of Eastern Adriatic Sea. Sustainability 2024, 16, 7531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Central Coordinating Committee for Surveillance and Protection of the Maritime Rights and Interests of the Republic Croatia, Annual Report on the Implementation of the Established Policy, Plans and Regulations Related to Surveillance and Protection of Rights and Interests of the Republic of Croatia at Sea for 2017 and 2018. Available online: https://vlada.gov.hr/UserDocsImages//2016/Sjednice/2019/Kolovoz/174%20sjednica%20VRH//174%20-%2017.1.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- The Central Coordinating Committee for Surveillance and Protection of the Maritime Rights and Interests of the Republic Croatia, Annual Report on the Implementation of the Established Policy, Plans and Regulations Related to Surveillance and Protection of Rights and Interests of the Republic of Croatia at Sea for 2019. Available online: https://mup.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/dokumenti/2020/Izvje%C5%A1%C4%87a/Godisnje%20izvjesce%20o%20provedbi%202019..pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- The Central Coordinating Committee for Surveillance and Protection of the Maritime Rights and Interests of the Republic Croatia, Annual Report on the Implementation of the Established Policy, Plans and Regulations Related to Surveillance and Protection of Rights and Interests of the Republic of Croatia at Sea for 2020. Available online: https://www.morh.hr/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/2021-07-05-godisnje-izvjesce-o-provedbi-utvr-politike.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- The Central Coordinating Committee for Surveillance and Protection of the Maritime Rights and Interests of the Republic Croatia, Annual Report on the Implementation of the Established Policy, Plans and Regulations Related to Surveillance and Protection of Rights and Interests of the Republic of Croatia at Sea for 2021. Available online: https://www.morh.hr/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/2022-06-30-gizinm.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- The Central Coordinating Committee for Surveillance and Protection of the Maritime Rights and Interests of the Republic Croatia, Annual Report on the Implementation of the Established Policy, Plans and Regulations Related to Surveillance and Protection of Rights and Interests of the Republic of Croatia at Sea for 2022. Available online: https://mmpi.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/dokumenti/MORE/More%206_23/Godisnje%20izvjesce%20o%20provedbi%20utvrdene%20politike,%20planova%20i%20propisa%20u%20vezi%20s%20nadzorom%20i%20zastitom%20prava%20i%20interesa%20RH%20na%20moru-2022%2029-6_23.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- The Central Coordinating Committee for Surveillance and Protection of the Maritime Rights and Interests of the Republic Croatia, Annual Report on the Implementation of the Established Policy, Plans and Regulations Related to Surveillance and Protection of Rights and Interests of the Republic of Croatia at Sea for 2023. Available online: https://mmpi.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/dokumenti/MORE/More%206_24/Godisnje%20izvjesce%20o%20provedbi%20utvrdene%20politike,%20planova%20i%20propisa%20u%20vezi%20s%20nadzorom%20i%20zastitom%20prava%20i%20interesa%20RH%20na%20moru-2023%2028-6_24.pdf (accessed on 31 July 2025).

- The Central Coordinating Committee for Surveillance and Protection of the Maritime Rights and Interests of the Republic Croatia, Annual Report on the Implementation of the Established Policy, Plans and Regulations Related to Surveillance and Protection of Rights and Interests of the Republic of Croatia at Sea for 2024. Available online: https://mup.gov.hr/UserDocsImages/dokumenti/2025/5/Godi%C5%A1nje%20izvje%C5%A1%C4%87e%20Sredi%C5%A1nje%20koordinacije%20za%202024.%20godinu.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Cooper, W.W.; Seiford, L.M.; Tone, K. Data Envelopment Analysis: A Comprehensive Text with Models, Applications, References and DEA-Solver Software; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nemery, P. On the Use of Multicriteria Ranking Methods in Sorting Problems. Ph.D. Thesis, Université Libre de Bruxelles, Brussels, Belgium, November 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brans, J.P.; Mareschal, B. PROMCALC & GAIA: A new decision support system for multicriteria decision aid. Decis. Support Syst. 1994, 12, 297–310. [Google Scholar]

- Mladineo, M.; Veza, I.; Gjeldum, N. Solving Partner Selection Problem in Cyber-Physical Production Networks using the HUMANT algorithm. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2017, 55, 2506–2521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Smet, Y. About the computation of robust PROMETHEE II rankings: Empirical evidence. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Bali, Indonesia, 4–7 December 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Year | Input Variables | Output Variable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Voyages | Number of Employed Vessels | Navigational Miles Traveled by Vessels | Fuel Consumption of Vessels (Liters) | Number of Monitored Subjects/Vessels | |

| 2017 | 400 | 110 | 20,790.00 | 290,363.80 | 3779 |

| 2018 | 404 | 110 | 21,003.00 | 279,376.38 | 3666 |

| 2019 | 394 | 116 | 19,545.00 | 216,787.36 | 2512 |

| 2020 | 309 | 118 | 15,017.10 | 169,915.12 | 1528 |

| 2021 | 410 | 149 | 23,849.40 | 209,773.90 | 2396 |

| 2022 | 467 | 135 | 22,248.10 | 197,860.70 | 2427 |

| 2023 | 426 | 128 | 19,572.00 | 153,732.30 | 1847 |

| 2024 | 375 | 130 | 16,807.00 | 156,518.00 | 1569 |

| Year | VRS Efficiency | CRS Efficiency | Scale of Efficiency | Returns to Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | CRS (0) |

| 2018 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | CRS (0) |

| 2019 | 0.998 | 0.883 | 0.885 | IRS (+1) |

| 2020 | 1.000 | 0.685 | 0.685 | IRS (+1) |

| 2021 | 0.955 | 0.870 | 0.911 | IRS (+1) |

| 2022 | 0.979 | 0.935 | 0.954 | IRS (+1) |

| 2023 | 1.000 | 0.916 | 0.916 | IRS (+1) |

| 2024 | 1.000 | 0.764 | 0.764 | IRS (+1) |

| Year | VRS Efficiency | CRS Efficiency | Scale of Efficiency | Returns to Scale |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | CRS (0) |

| 2018 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | CRS (0) |

| 2019 | 0.904 | 0.883 | 0.976 | IRS (+1) |

| 2020 | 0.700 | 0.685 | 0.979 | IRS (+1) |

| 2021 | 0.900 | 0.870 | 0.968 | IRS (+1) |

| 2022 | 0.976 | 0.935 | 0.957 | IRS (+1) |

| 2023 | 1.000 | 0.916 | 0.916 | IRS (+1) |

| 2024 | 0.806 | 0.764 | 0.948 | IRS (+1) |

| Year | Efficiency | Key Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Input Model | Output Model | ||

| 2017 | 1.000 | 1.000 | Both Input and Output are efficient (strong efficiency) |

| 2018 | 1.000 | 1.000 | Both Input and Output are efficient (strong efficiency) |

| 2019 | 0.998 | 0.904 | Input: almost efficient; Output: required output growth (+10.6%) |

| 2020 | 1.000 | 0.700 | Input: efficient; Output: required output growth (+42.8%), low input slacks |

| 2021 | 0.955 | 0.900 | Both Input and Output are inefficient; Input emphasizes reductions, output emphasizes growth of results |

| 2022 | 0.979 | 0.976 | Both Input and Output are close to efficiency; Input slacks in both |

| 2023 | 1.000 | 1.000 | Input: efficient; Output: very high input slacks |

| 2024 | 1.000 | 0.806 | Input: efficient; Output: required output growth (+24.1%), high input slacks |

| DEA Ranking | Rank Reversal | |

|---|---|---|

| Model of DEA-Based PROMETHEE II Score [18] | Improved DEA–PROMETHEE Hybrid Model | |

| RBC | Yes | No |

| MKO | No | No |

| MDR | No | No |

| TFC | Yes | No |

| RRC | Yes | No |

| MKR | Yes | Yes |

| PSC | Yes | No |

| MKK | Yes | Yes |

| LJC | Yes | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sunko, T.; Mladineo, M.; Medvidović, Z.; Dedo, M. Evaluation of Maritime Safety Policy Using Data Envelopment Analysis and PROMETHEE Method. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13256. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413256

Sunko T, Mladineo M, Medvidović Z, Dedo M. Evaluation of Maritime Safety Policy Using Data Envelopment Analysis and PROMETHEE Method. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13256. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413256

Chicago/Turabian StyleSunko, Tomislav, Marko Mladineo, Zoran Medvidović, and Mihael Dedo. 2025. "Evaluation of Maritime Safety Policy Using Data Envelopment Analysis and PROMETHEE Method" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13256. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413256

APA StyleSunko, T., Mladineo, M., Medvidović, Z., & Dedo, M. (2025). Evaluation of Maritime Safety Policy Using Data Envelopment Analysis and PROMETHEE Method. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13256. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413256