A Dual-Head Mixer-BiLSTM Architecture for Battery State of Charge Prediction

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Material and Methods

3.1. BMW i3 Dataset

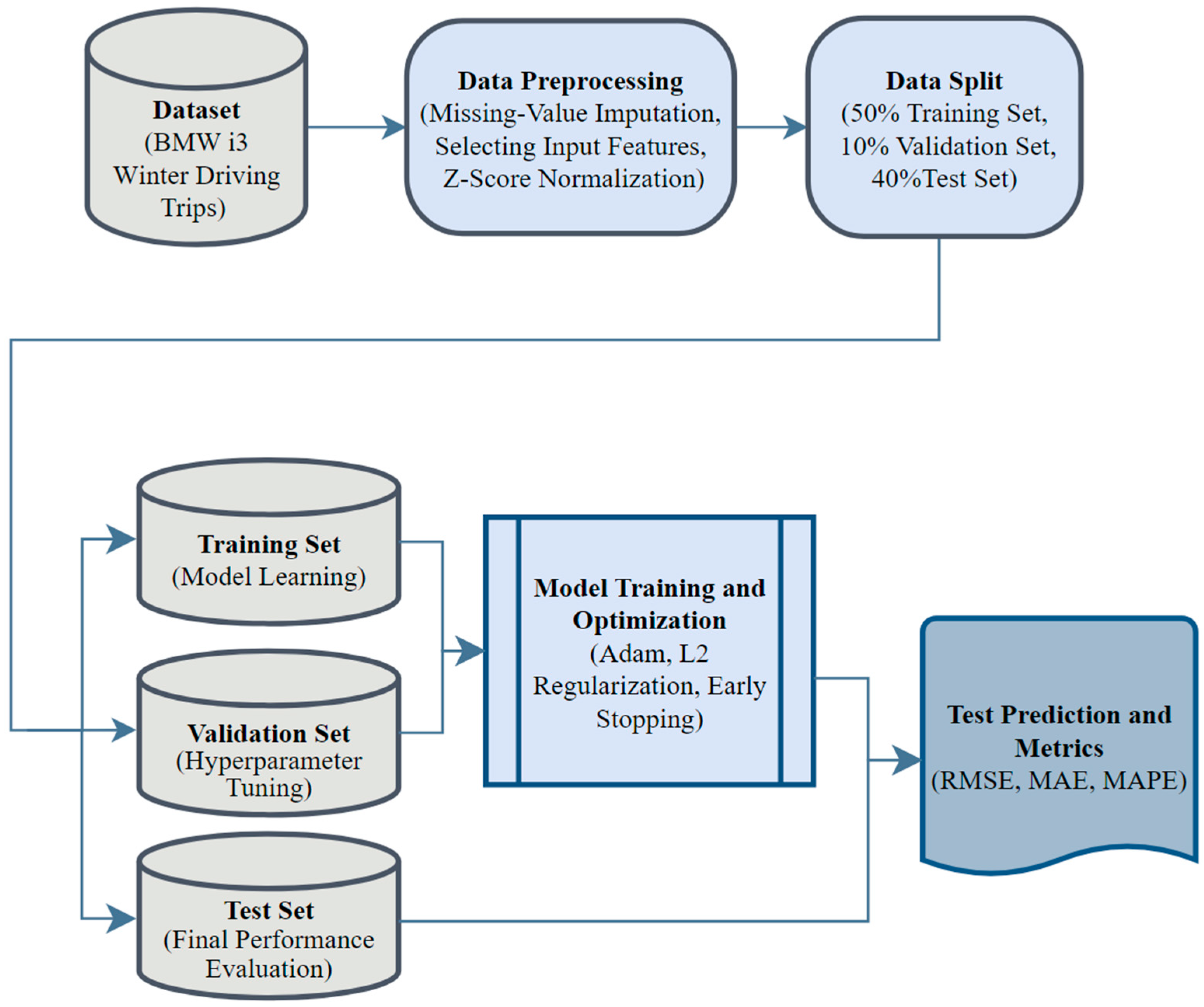

3.2. Proposed Framework

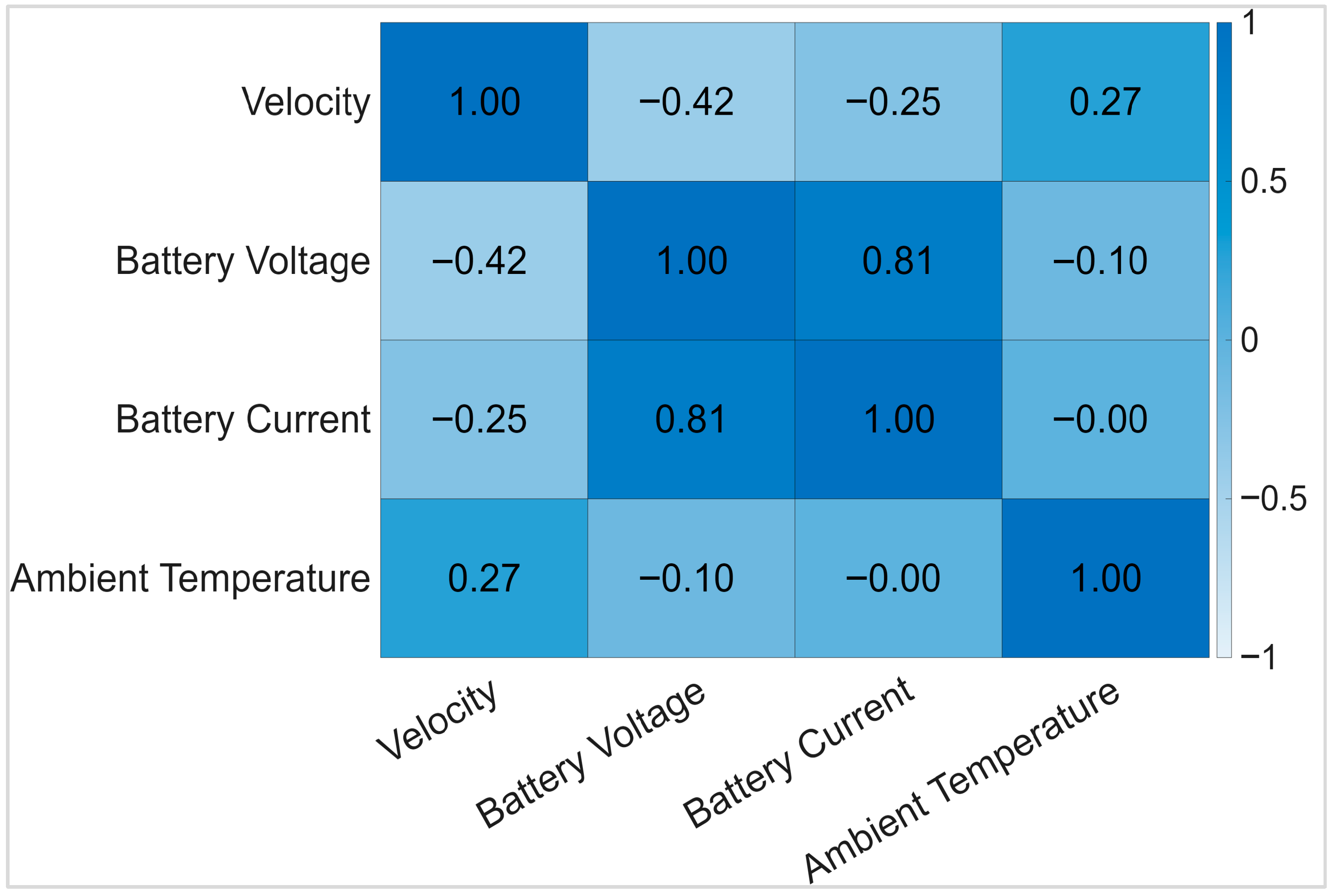

3.2.1. Data Preprocessing

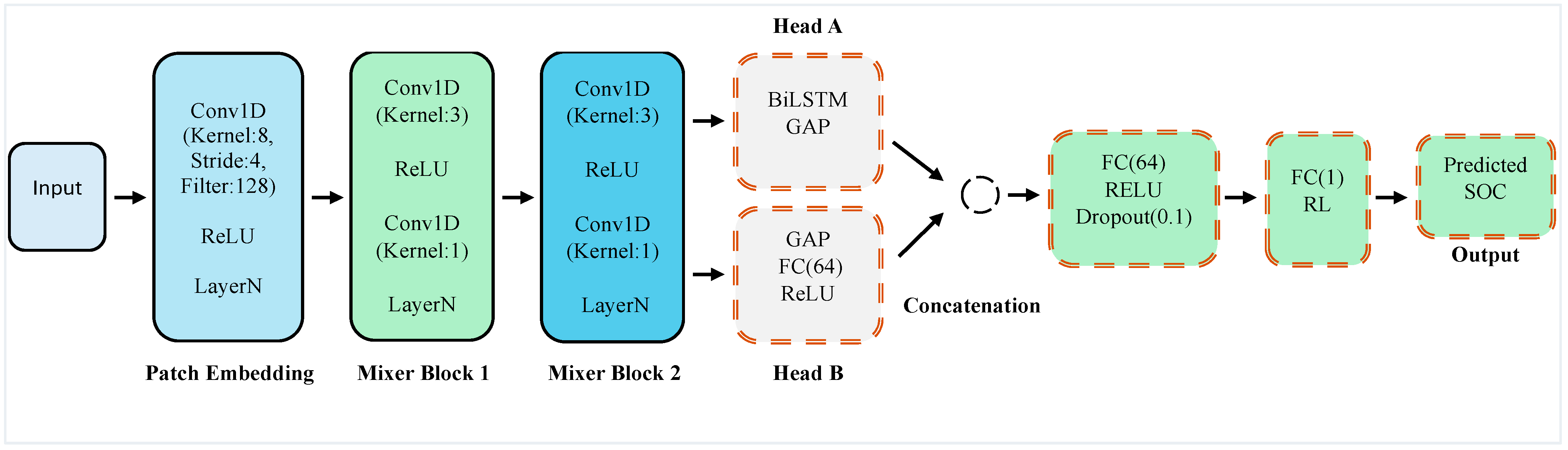

3.2.2. SOC Estimation

3.2.3. Computational Feasibility

4. Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Electric Vehicle Battery Market Size, Segments, Regional Outlook (NA, EU, APAC, LA, MEA) & Competitive Landscape, 2025–2034. Available online: https://www.towardsautomotive.com/insights/electric-vehicle-battery-market-sizing (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Hannan, M.A.; Hoque, M.M.; Hussain, A.; Yusof, Y.; Ker, P.J. State-of-the-Art and Energy Management System of Lithium-Ion Batteries in Electric Vehicle Applications: Issues and Recommendations. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 19362–19378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, R.; Cao, J.; Yu, Q.; He, H.; Sun, F. Critical Review on the Battery State of Charge Estimation Methods for Electric Vehicles. IEEE Access 2017, 6, 1832–1843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manthopoulos, A.; Wang, X. A Review and Comparison of Lithium-Ion Battery SOC Estimation Methods for Electric Vehicles. In Proceedings of the IECON 2020 (Industrial Electronics Conference), Singapore, 18–21 October 2020; pp. 2385–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movassagh, K.; Raihan, A.; Balasingam, B.; Pattipati, K. A Critical Look at Coulomb Counting Approach for State of Charge Estimation in Batteries. Energies 2021, 14, 4074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrivastava, P.; Naidu, P.A.; Sharma, S.; Panigrahi, B.K.; Garg, A. Review on Technological Advancement of Lithium-Ion Battery States Estimation Methods for Electric Vehicle Applications. J. Energy Storage 2023, 64, 107159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, J.; Zhao, P.; Kang, J.; Yan, F.; Du, C. Correlation between the Model Accuracy and Mod-el-Based SOC Estimation. Electrochim. Acta 2017, 228, 146–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sesidhar, D.V.S.R.; Badachi, C.; Green, R.C. A Review on Data-Driven SOC Estimation with Li-Ion Batteries: Implementation Methods & Future Aspirations. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipu, M.H.; Hannan, M.A.; Hussain, A.; Ayob, A.; Saad, M.H.; Karim, T.F.; How, D.N. Data-Driven State of Charge Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries: Algorithms, Im-plementation Factors, Limitations and Future Trends. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 124110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindemann, B.; Müller, T.; Vietz, H.; Jazdi, N.; Weyrich, M. A Survey on Long Short-Term Memory Networks for Time Series Prediction. Procedia CIRP 2021, 99, 650–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimi-Eichi, H.; Chow, M.Y. Big-Data Framework for Electric Vehicle Range Estimation. In Proceedings of the IECON 2014 (Industrial Electronics Conference), Dallas, TX, USA, 29 October–1 November 2014; pp. 5628–5634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.H.; Khan, N.M.; Houran, M.A.; Mansoor, M.; Akhtar, N.; Sanfilippo, F. A Novel Hybrid Deep Learning Model for Accurate State of Charge Estimation of Li-Ion Batteries for Electric Vehicles under High and Low Temperature. Energy 2024, 292, 130584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Ryu, S.; Park, K.; Kim, H. Machine Learning-Based Lithium-Ion Battery Capacity Estimation Ex-ploiting Multi-Channel Charging Profiles. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 75143–75152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, P.K.; Jena, P.; Padhy, N.P. Electric Vehicle State-of-Charge Prediction Using Deep LSTM Network Model. In Proceedings of the 10th IEEE International Conference on Power Electronics, Drives and Energy Systems (PEDES 2022), Jaipur, India, 14–17 December 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Fan, Y.; Jin, S.; Takyi-Aninakwa, P.; Fernandez, C. Improved Anti-Noise Adaptive Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network Modeling for the Robust Remaining Useful Life Prediction of Lithium-Ion Batteries. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2023, 230, 108920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wu, F.; Takyi-Aninakwa, P.; Fernandez, C.; Stroe, D.I.; Huang, Q. Improved Singular Filtering–Gaussian Process Regression–Long Short-Term Memory Model for Whole-Life-Cycle Remaining Capacity Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries Adaptive to Fast Aging and Multi-Current Variations. Energy 2023, 284, 128677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Zuo, W.; Zhou, K.; Li, Q.; Huang, Y. State of Charge Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on PSO–TCN–Attention Neural Network. J. Energy Storage 2024, 84, 110806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Xiong, R.; Shen, W.; Lu, J. State-of-Charge Estimation of LiFePO4 Batteries in Electric Vehicles: A Deep-Learning Enabled Approach. Appl. Energy 2021, 291, 116812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.H.; Mansoor, M.; Abou Houran, M.; Khan, N.M.; Khan, K.; Moosavi, S.K.R.; Sanfilippo, F. Hybrid Deep Learning Model for Efficient State of Charge Estimation of Li-Ion Batteries in Electric Vehicles. Energy 2023, 282, 128317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.L. Deep Learning-Based State of Charge Estimation for Electric Vehicle Batteries: Overcoming Tech-nological Bottlenecks. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandran, V.; Patil, C.K.; Karthick, A.; Ganeshaperumal, D.; Rahim, R.; Ghosh, A. State of Charge Estimation of Lithium-Ion Battery for Electric Vehicles Using Machine Learning Algorithms. World Electr. Veh. J. 2021, 12, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Abualsaud, K. On Equivalent Circuit Model-Based State-of-Charge Estimation for Lithium-Ion Batteries in Electric Vehicles. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 69950–69966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.; Wen, S.; Zhao, Q.; Zhang, B.; Wu, G.; Zhu, M. Multi-Model Deep Learning-Based State of Charge Estimation for Shipboard Lithium Batteries with Feature Extraction and Spatio-Temporal Dependency. J. Power Sources 2025, 629, 235983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; Shi, D.; Nan, J.; Burke, A.F. Battery State of Health Estimation under Fast Charging via Deep Transfer Learning. iScience 2025, 28, 112235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IEEE DataPort. Battery and Heating Data in Real Driving Cycles. Available online: https://ieee-dataport.org/open-access/battery-and-heating-data-real-driving-cycles (accessed on 10 December 2025).

- Hochreiter, S.; Schmidhuber, J. Long Short-Term Memory. Neural Comput. 1997, 9, 1735–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oruh, J.; Viriri, S.; Adegun, A. Long Short-Term Memory Recurrent Neural Network for Automatic Speech Recognition. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 30069–30079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuster, M.; Paliwal, K.K. Bidirectional Recurrent Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 1997, 45, 2673–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pau, D.P.; Aniballi, A. Tiny Machine Learning Battery State-of-Charge Estimation Hardware Accelerated. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ruan, G.; Tian, Y.; Hu, X.; Yan, R.; Yang, K. A Real-World Battery State of Charge Prediction Method Based on a Lightweight Mixer Architecture. Energy 2024, 311, 133434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nainika, C.; Balamurugan, P.; Febin Daya, J.L.; Anantha Krishnan, V. Real Driving Cycle Based SoC and Battery Temperature Prediction for Electric Vehicle Using AI Models. J. Appl. Res. Technol. 2024, 22, 351–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mustaffa, Z.; Sulaiman, M.H.; Isuwa, J. State of Charge Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries in an Electric Vehicle Using Hybrid Metaheuristic–Deep Neural Networks Models. Energy Storage Sav. 2025, 4, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariche, S.; Boulghasoul, Z.; El Ouardi, A.; Elbacha, A.; Tajer, A.; Espié, S. A Comparative Study of Electric Vehicles Battery State of Charge Estimation Based on Machine Learning and Real Driving Data. J. Low Power Electron. Appl. 2024, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trip | Route/Area | Initial Battery SOC (%) | Final Battery SOC (%) | Distance (km) | Duration (min) | Number of Rows | Mean Speed | Mean Voltage | Mean Current | Mean Ambient Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TripB01 | FTMRoute (2×) | 86.1 | 57.4 | 38.8 | 54.2 | 32,518 | 42.9 | 378.7 | −19.6 | 9.5 |

| TripB02 | FTMRoute | 81.0 | 66.2 | 18.9 | 26.9 | 16,113 | 42.3 | 381.6 | −26.5 | 7.2 |

| TripB03 | FTMRoute | 67.4 | 50.4 | 19.4 | 26.3 | 15,794 | 44.2 | 370.2 | −24.0 | 5.0 |

| TripB04 | Munich North | 45.1 | 69.2 | 16.6 | 49.2 | 29,550 | 20.2 | 379.7 | 17.1 | 10.1 |

| TripB05 | Munich North | 71.9 | 59.5 | 14.82 | 17.0 | 10,195 | 52.3 | 373.1 | −27.2 | 7.5 |

| TripB06 | Munich North | 83.2 | 69.3 | 16.6 | 22.5 | 13,521 | 44.1 | 382.0 | −22.8 | 6.5 |

| TripB07 | Munich Northeast | 67.4 | 50.4 | 30.4 | 38.2 | 22,899 | 47.8 | 369.9 | −24.4 | 2.3 |

| TripB08 | Munich Northeast | 67.3 | 44.0 | 32.2 | 48.6 | 29,140 | 39.8 | 369.4 | −17.8 | 10.2 |

| TripB09 | Munich South | 70.0 | 46.0 | 54.2 | 93.5 | 56,102 | 34.8 | 371.6 | 24.5 | 7.1 |

| TripB10 | Highway | 84.8 | 39.0 | 47.8 | 33.7 | 20,233 | 85.1 | 364.7 | −50.4 | 4.4 |

| TripB11 | Munich South | 38.9 | 30.8 | 10.2 | 12.6 | 7534 | 48.8 | 360.3 | −23.8 | 5.9 |

| TripB12 | Highway | 73.4 | 51.3 | 37.1 | 53.8 | 32,256 | 41.4 | 378.8 | −15.3 | 5.9 |

| TripB13 | Munich South | 57.0 | 55.1 | 2.8 | 5.9 | 3545 | 28.3 | 375.1 | −12.3 | 5.2 |

| TripB14 | Highway | 85.5 | 34.6 | 61.0 | 63.7 | 38,220 | 57.4 | 368.0 | −29.6 | 3.5 |

| TripB15 | FTMRoute | 85.1 | 67.5 | 19.2 | 30.4 | 18,223 | 38.0 | 381.3 | −21.5 | 2.7 |

| TripB16 | FTMRoute | 67.5 | 52.8 | 19.2 | 25.5 | 15,286 | 45.3 | 372.4 | −21.3 | 3.1 |

| TripB17 | FTMRoute | 52.8 | 37.2 | 19.2 | 26.0 | 15,610 | 44.4 | 365.4 | −22.2 | 3.4 |

| TripB18 | Munich North | 82.8 | 68.1 | 15.8 | 18.5 | 11,095 | 51.3 | 375.2 | −29.4 | 5.1 |

| TripB19 | Munich North | 85.8 | 71.6 | 16.4 | 19.9 | 11,911 | 49.6 | 379.5 | −26.5 | 4.3 |

| TripB20 | Munich North | 72.7 | 62.0 | 12.3 | 23.4 | 14,029 | 31.7 | 376.8 | −16.9 | 8.6 |

| TripB21 | Munich North | 55.7 | 41.1 | 15.8 | 17.3 | 10,397 | 54.8 | 365.2 | −31.2 | 4.1 |

| TripB22 | Munich North | 84.4 | 70.5 | 16.9 | 20.0 | 11,993 | 50.6 | 380.8 | −25.8 | 8.7 |

| TripB23 | Munich North | 72.1 | 53.5 | 18.7 | 18.6 | 11,133 | 60.5 | 366.8 | −37.1 | 5.7 |

| TripB24 | Munich North | 53.4 | 45.5 | 9.3 | 16.3 | 9780 | 34.4 | 367.7 | −17.9 | 5.8 |

| TripB25 | Munich North | 45.4 | 33.6 | 13.5 | 17.0 | 10,219 | 47.6 | 359.3 | −25.8 | 5.7 |

| TripB26 | Munich North | 33.4 | 21.2 | 14.7 | 13.4 | 8050 | 65.7 | 348.7 | −33.6 | 5.7 |

| TripB27 | FTMRoute | 52.9 | 34.5 | 19.2 | 24.5 | 14,690 | 47.1 | 361.1 | −28.0 | 2.6 |

| TripB28 | FTMRoute | 34.4 | 20.0 | 17.5 | 22.8 | 13,665 | 46.2 | 351.1 | −24.2 | 3.3 |

| TripB29 | Munich North | 31.5 | 15.4 | 15.8 | 16.1 | 9686 | 58.8 | 346.7 | −37.0 | 4.8 |

| TripB30 | Munich North | 84.2 | 70.4 | 14.9 | 15.3 | 9209 | 58.1 | 376.2 | −33.2 | 1.1 |

| TripB31 | Munich North | 72.1 | 57.8 | 15.2 | 18.3 | 10,969 | 50.0 | 370.0 | −29.0 | 4.3 |

| TripB32 | Munich North | 52.6 | 38.1 | 14.2 | 13.3 | 7958 | 64.4 | 358.6 | −40.5 | 2.2 |

| TripB33 | Munich North | 77.4 | 71.6 | 7.0 | 9.1 | 5480 | 46.2 | 384.0 | −23.7 | 4.2 |

| TripB34 | Munich North | 73.9 | 71.3 | 9.1 | 12.2 | 7338 | 44.9 | 382.2 | −18.2 | 5.8 |

| TripB35 | Munich North | 85.4 | 71.5 | 15.4 | 22.7 | 13,626 | 40.7 | 382.0 | −22.7 | 7.6 |

| TripB36 | Munich North | 72.1 | 44.5 | 38.7 | 47.5 | 28,523 | 48.9 | 369.4 | −21.5 | 7.2 |

| TripB37 | Munich East | 83.8 | 68.0 | 17.5 | 23.6 | 14,173 | 44.4 | 380.4 | −24.9 | −3.3 |

| TripB38 | FTMRoute reverse | 65.0 | 48.8 | 18.9 | 27.4 | 16,429 | 41.4 | 364.6 | −22.0 | −0.9 |

| Hyperparameter | Evaluated Values |

|---|---|

| Learning Rate | 5 × 10−5, 8 × 10−4, 1 × 10−3 |

| Learning Rate Drop Factor | 0.3, 0.5, 0.8 |

| Learning Rate Drop Period | 20, 25, 30 |

| L2 Regularization Coefficient | 5 × 10−5, 2 × 10−4, 1 × 10−3 |

| Validation Patience | 12, 16, 20 |

| Batch Size | 16, 32, 48 |

| Test Dataset | 5%, 15%, 40% |

| Valid Dataset | 5%, 10%, 15% |

| Study | Method | RMSE (%) | MAE (%) | MAPE (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pau and Aniballi (2024) [29] | TCN | 2.32 | - | 2.96 |

| Liu et al. (2024) [30] | Trend Flow-Mixer | 1.19 | 0.46 | - |

| Nainika et al. (2024) [31] | Lasso Regression | 0.49 | 0.43 | - |

| Mustaffa et al. (2025) [32] | Teaching–Learning-Based Optimization (TLBO) DNN | 4.64 | 3.44 | - |

| Ariche et al. (2024) [33] | Neural Networks (NNs) | 0.79 | 0.49 | - |

| Lin (2024) [20] | DNN | 0.84 | 0.62 | - |

| Proposed Method | DH-DW-M | 0.21 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kara, F.; Yücedağ, İ. A Dual-Head Mixer-BiLSTM Architecture for Battery State of Charge Prediction. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13255. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413255

Kara F, Yücedağ İ. A Dual-Head Mixer-BiLSTM Architecture for Battery State of Charge Prediction. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13255. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413255

Chicago/Turabian StyleKara, Fatih, and İbrahim Yücedağ. 2025. "A Dual-Head Mixer-BiLSTM Architecture for Battery State of Charge Prediction" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13255. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413255

APA StyleKara, F., & Yücedağ, İ. (2025). A Dual-Head Mixer-BiLSTM Architecture for Battery State of Charge Prediction. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13255. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413255