Numerical Study on the Effect of Drafting Spacing on the Aerodynamic Drag Between Cyclists in Cycling Races

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Research Method

2.1. Governing Equations

2.2. Turbulence Model

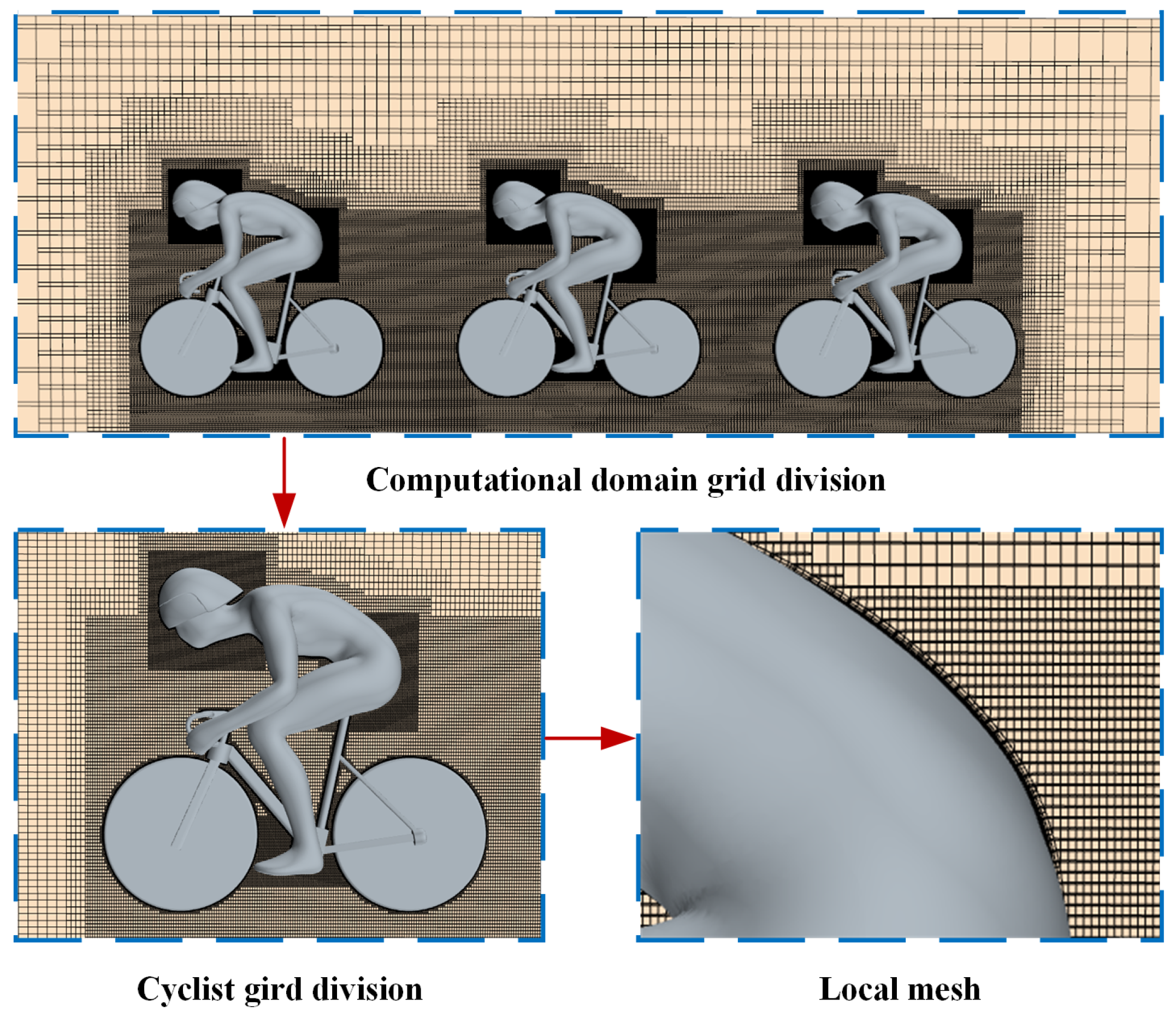

2.3. Computational Model and Grid Division

2.4. Mesh Independence and Convergence Verification

2.5. Validation of the Numerical Simulation Method

3. Results and Discussion

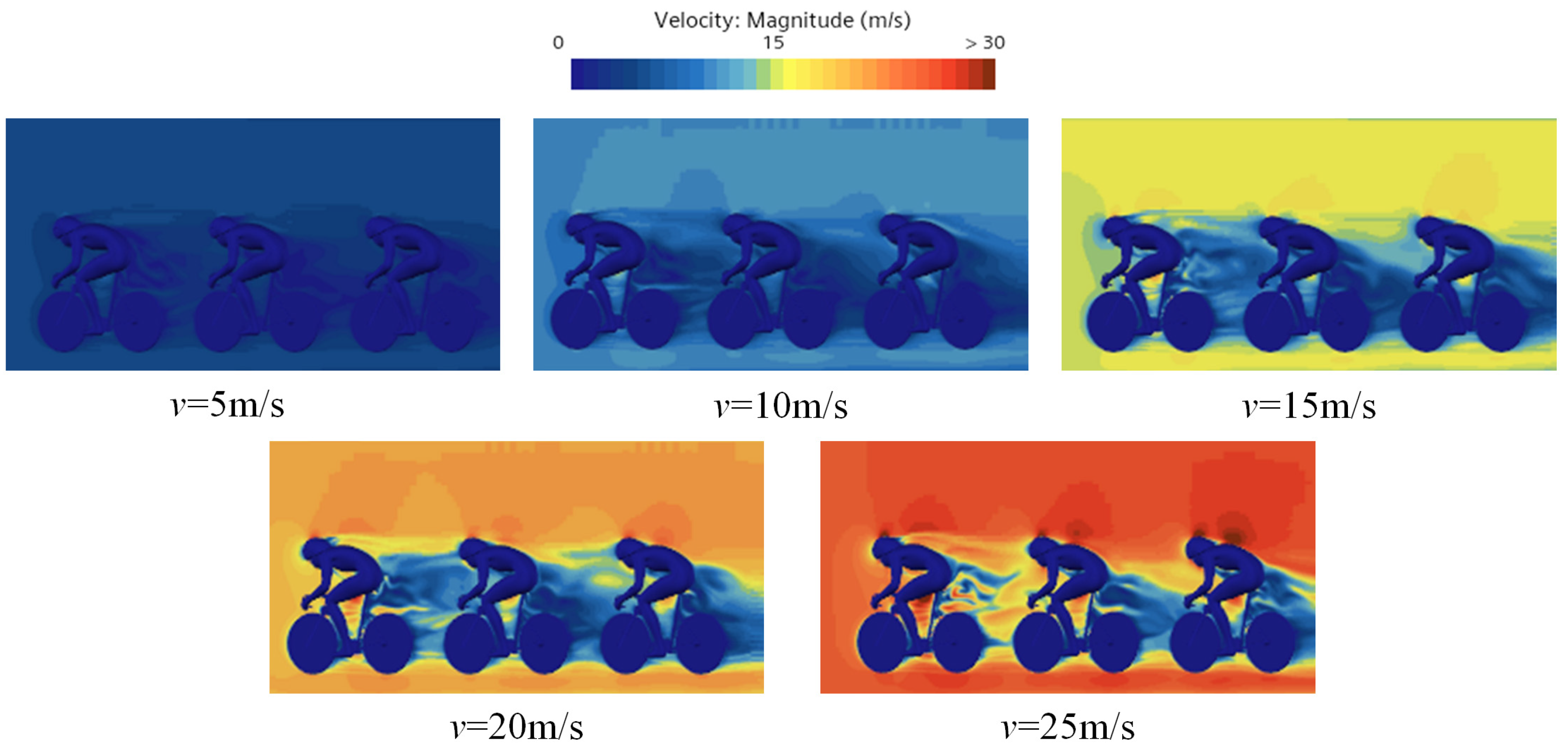

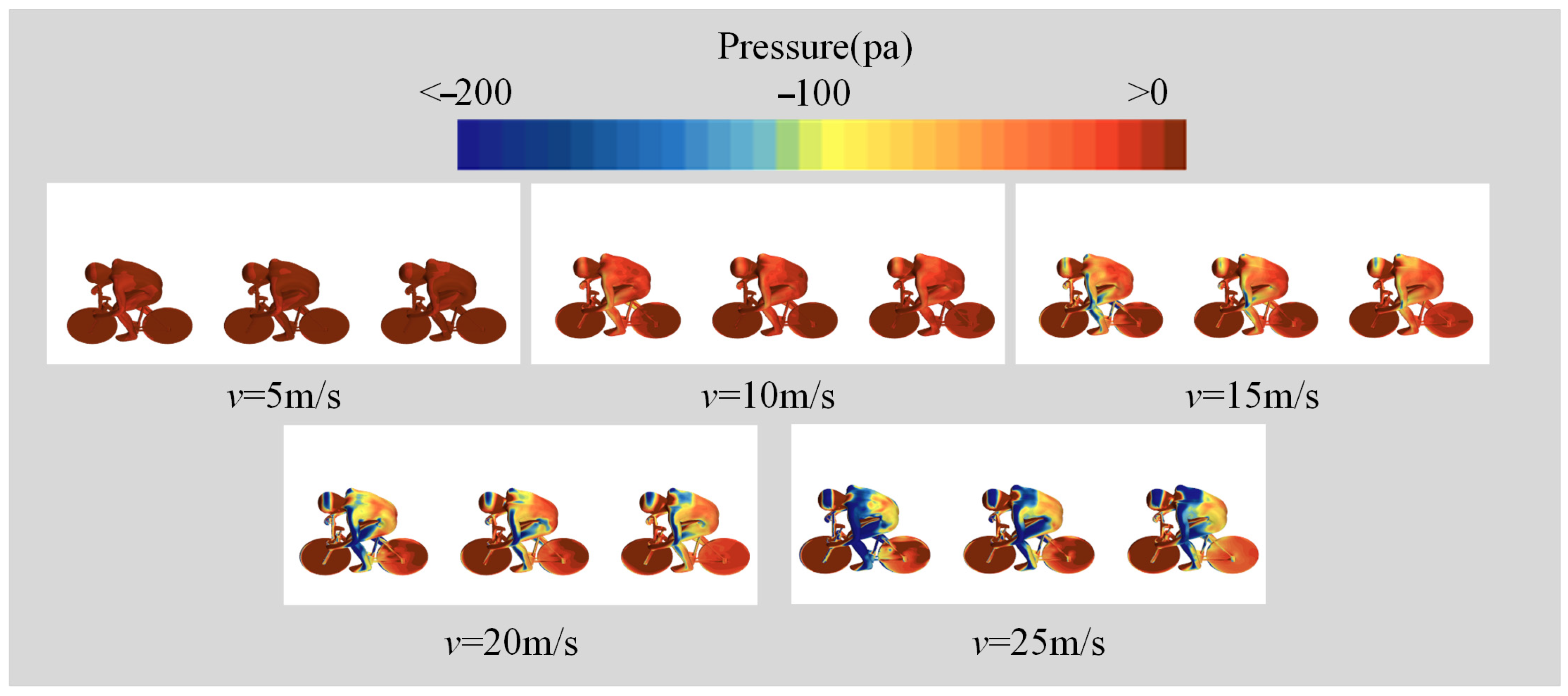

3.1. Influence of the Velocity Magnitude on the Flow Field

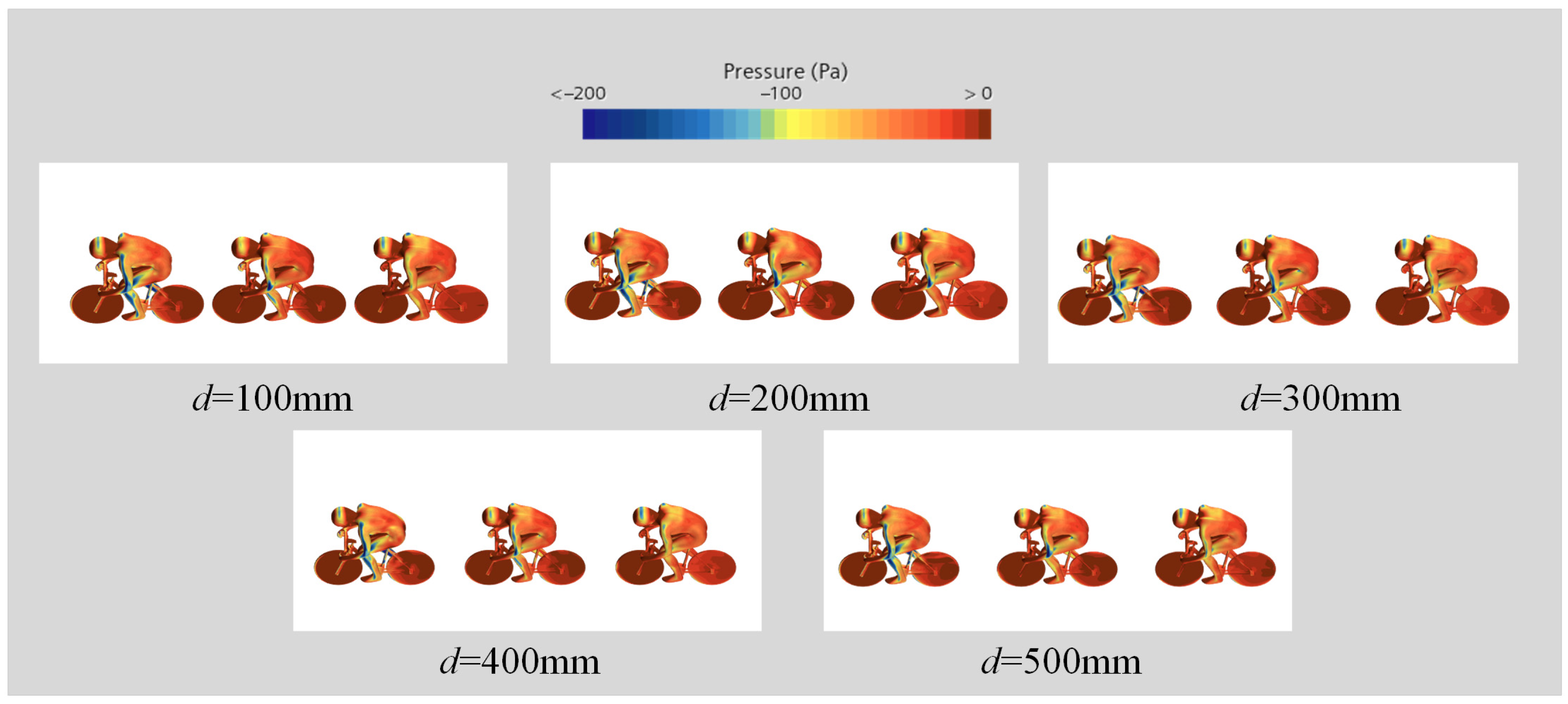

3.2. Influence of the Spacing Magnitude on the Flow Field

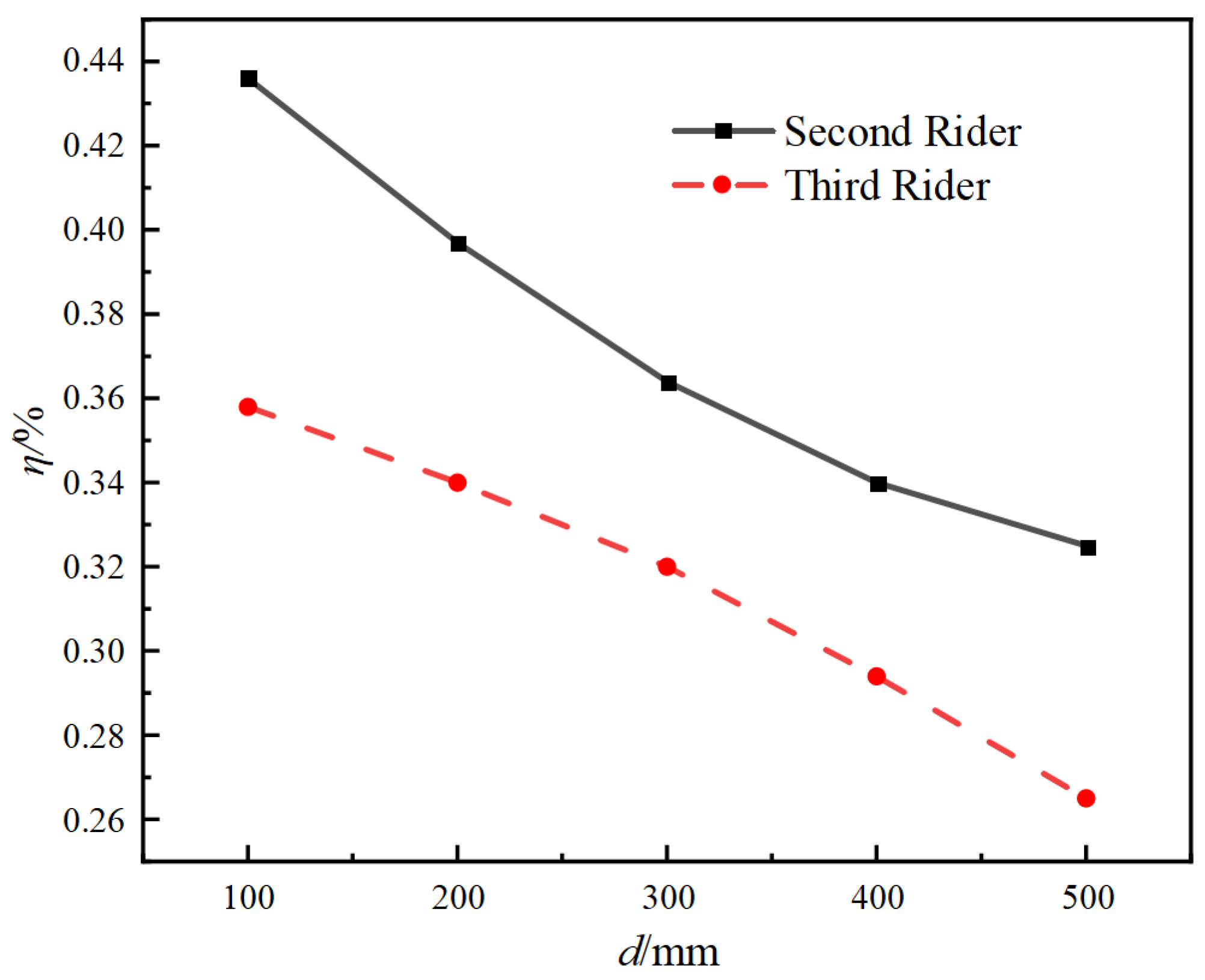

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grappe, F.; Candau, R.; Belli, A.; Rouillon, J.D. Aerodynamic drag in field cycling with special reference to the Obree’s position. Ergonomics 1997, 40, 1299–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, C.R.; Burke, E.R. Improving the racing bicycle. Mech. Eng. 1984, 106, 34–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bourlet, C. Traité des Bicycles et Bicyclettes: Suivi d’une Application à la Construction des Vélodromes. 1894. Available online: https://cnum.cnam.fr/pgi/redir.php?onglet=d&ident=12DY14 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Pearce, D.H.; Milhorn, H.T., Jr. Dynamic and steady-state respiratory responses to bicycle exercise. J. Appl. Physiol. 1977, 42, 959–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kyle, C.R. Experiments in human ergometry as applied to the design of human powered vehicles. J. Appl. Biomech. 1986, 2, 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, A.C.; Kyle, C.R.; Malewicki, D.J. The aerodynamics of human-powered land vehicles. Sci. Am. 1983, 249, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravkovich, M.M. Aerodynamics of bicycle wheel and frame. J. Wind. Eng. Ind. Aerodyn. 1992, 40, 55–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonweiler, T. The Air Resistance of Racing Cyclists. 1956. Available online: https://dspace.lib.cranfield.ac.uk/items/88f6c4a5-e421-4134-9975-1980153969a9 (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Kyle, C.R. Reduction of wind resistance and power output of racing cyclists and runners travelling in groups. Ergonomics 1979, 22, 387–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCole, S.D.; Claney, K.; Conte, J.C.; Anderson, R.; Hagberg, J.M. Energy expenditure during bicycling. J. Appl. Physiol. 1990, 68, 748–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagberg, J.M.; McCole, S.D. The effect of drafting and aerodynamic equipment on the energy expenditure during cycling. Cycl. Sci. 1990, 2, 19–22. [Google Scholar]

- Broker, J.P.; Kyle, C.R.; Burke, E.R. Racing cyclist power requirements in the 4000-m individual and team pursuits. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1999, 31, 1677–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, A.G.; Byrnes, W.C. Aerodynamic characteristics as determinants of the drafting effect in cycling. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 39, 170–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.C.; Milliken, D.L.; Cobb, J.E.; McFadden, K.L.; Coggan, A.R. Validation of a mathematical model for road cycling power. J. Appl. Biomech. 1998, 14, 276–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassett, D.R., Jr.; Kyle, C.R.; Passfield, L.; Broker, J.P.; Burke, E.R. Comparing cycling world hour records 1967–1996: Modeling with empirical data. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1999, 31, 1665–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olds, T. The mathematics of breaking away and chasing in cycling. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1998, 77, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olds, T. Modelling human locomotion: Applications to cycling. Sports Med. 2001, 31, 497–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lukes, R.A.; Chin, S.B.; Hart, J.H.; Haake, S. The Aerodynamics of Mountain Bicycles: The Role of Computational Fluid Dynamics. 2004. Available online: https://shura.shu.ac.uk/2294/ (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- McManus, J.; Zhang, X. A computational study of the flow around an isolated wheel in contact with the ground. J. Fluids Eng. 2006, 128, 520–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blocken, B.; Defraeye, T.; Koninckx, E.; Carmeliet, J.; Hespel, P. Numerical study on the aerodynamic drag of drafting cyclist groups. In Proceedings of the 6th European and African Conference on Wind Engineering EACWE, Cambridge, UK, 7–11 July 2013; pp. 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Oggiano, L.; Spurkland, L.; Sætran, L.; Bardal, L.M. Aerodynamical resistance in cycling on a single rider and on Two drafting riders: CFD simulations, validation and comparison with wind tunnel tests. In Proceedings of the International Congress on Sports Science Research and Technology Support, Lisbon, Portugal, 15–17 November 2015; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 22–37. [Google Scholar]

- Defraeye, T.; Blocken, B.; Koninckx, E.; Hespel, P.; Carmeliet, J. Aerodynamic study of different cyclist positions: CFD analysis and full-scale wind-tunnel tests. J. Biomech. 2010, 43, 1262–1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, N.; Sheridan, J.; Burton, D.; Brown, N.A. The effect of spatial position on the aerodynamic interactions between cyclists. Procedia Eng. 2014, 72, 774–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barry, N.; Burton, D.; Sheridan, J.; Thompson, M.; Brown, N.A.T. Aerodynamic drag interactions between cyclists in a team pursuit. Sports Eng. 2015, 18, 93–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Druenen, T.; Blocken, B. Aerodynamic analysis of uphill drafting in cycling. Sports Eng. 2021, 24, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benito, M.A.; Herrero-Molleda, A.; Garcia-Lopez, J. Benefits of drafting on the leading cyclist: A preliminary field study. ISBS Proc. Arch. 2022, 40, 70. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, S.; Kelso, R.; Grimshaw, P.; Warr, A. Measurements of roll, steering, and the far-field wake in track cycling. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blocken, B.; Malizia, F.; van Druenen, T.; Gillmeier, S. Aerodynamic benefits for a cyclist by drafting behind a motorcycle. Sports Eng. 2020, 23, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoelstra, A.; Mahalingesh, N.; Sciacchitano, A. Drafting effect in cycling: On-site aerodynamic investigation by the ‘Ring of Fire’. Proceedings 2020, 49, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zdravkovich, M.M.; Ashcroft, M.W.; Chishohn, S.J.; Hicks, N. Effect of cyclist’s posture and vicinity of another cyclist on aerodynamic drag. In The Engineering of Sport; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2020; pp. 21–28. [Google Scholar]

- Van Druenen, T.; Blocken, B. Aerodynamic impact of cycling postures on drafting in single paceline configurations. Comput. Fluids 2023, 257, 105863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Dong, Y.F.; Li, H.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, J. Analysis of Overall Aerodynamic Characteristics of Spanwise Adaptive Wing. J. Xi’an Jiaotong Univ. 2020, 54, 174–184. [Google Scholar]

| Velocity | Max Flow Velocity | Min Pressure | Max Wall Shear Stress |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 m/s | 6.8 m/s | −12.8 Pa | 0.24 Pa |

| 10 m/s | 14.1 m/s | −42.5 Pa | 0.98 Pa |

| 15 m/s | 21.5 m/s | −95.2 Pa | 2.35 Pa |

| 20 m/s | 29.2 m/s | −158.4 Pa | 4.10 Pa |

| 25 m/s | 37.6 m/s | −225.8 Pa | 6.55 Pa |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, F.; Lu, L.; Yang, S. Numerical Study on the Effect of Drafting Spacing on the Aerodynamic Drag Between Cyclists in Cycling Races. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13206. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413206

Li F, Lu L, Yang S. Numerical Study on the Effect of Drafting Spacing on the Aerodynamic Drag Between Cyclists in Cycling Races. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13206. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413206

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Fei, Lin Lu, and Shuai Yang. 2025. "Numerical Study on the Effect of Drafting Spacing on the Aerodynamic Drag Between Cyclists in Cycling Races" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13206. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413206

APA StyleLi, F., Lu, L., & Yang, S. (2025). Numerical Study on the Effect of Drafting Spacing on the Aerodynamic Drag Between Cyclists in Cycling Races. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13206. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413206