1. Introduction

In recent years, surrogate models [

1,

2] (also known as meta-models or response surface models) have gained increasing popularity in solving black-box problems due to their convenience and efficiency. Black-box problems [

3,

4] refer to a class of problems where the explicit expression of the objective function is unavailable. Surrogate models, however, can simulate and approximate the true objective function using known data, thereby facilitating the solution of black-box problems. Common surrogate models, such as Kriging [

5,

6,

7,

8], radial basis functions [

9,

10], neural networks [

11,

12], support vector machines [

13,

14], and polynomial chaos expansion [

15,

16], have been extensively employed in engineering design problems. Among these, the Kriging model is widely used due to its high computational efficiency, suitability for low-dimensional problems, and ability to approximate highly nonlinear models.

The initial Design of Experiments (DoE) in the construction of a Kriging model acquires samples for modeling. The initial DoE involves collecting all the samples needed for modeling in a single instance, such as Latin Hypercube Sampling (LHS) [

17,

18], Optimal Latin Hypercube Sampling (OLHS) [

19,

20], Monte Carlo Random Sampling [

21,

22], etc. Since the true objective function is unknown, there is no guarantee that all the sample points generated by the initial DoE are of high quality for high-precision modeling [

23]. Furthermore, a greater number of sample points means higher computational costs, so it is necessary to reduce the number of samples as much as possible in order to minimize the costs. Consequently, the key problem of modeling is to construct surrogate models with the highest possible accuracy at the lowest possible computational cost, which necessitates that the sample points used for modeling are of a higher quality, i.e., the sample points contain richer information [

24,

25,

26,

27]. To address this challenge, adaptive Kriging methodologies have been developed to iteratively refine sampling distributions through intelligent infill criteria [

28].

In the field of complex engineering system design, Kriging-based engineering design methods have become a core technology for handling black-box problems [

26]. However, as the complexity of various engineering fields increasingly demands a higher model accuracy, the existing methods have revealed significant shortcomings in model fitting, spatial correlation, and candidate set generation. This paper addresses three key issues in Kriging modeling and proposes solutions.

First, the current adaptive sampling methods based on Kriging overly rely on variance criteria, which limits the exploration capability of the parameter space and significantly affects the global prediction accuracy of the surrogate model. Forrester et al. [

29] found in multi-peak function modeling experiments that if Kriging variance is solely used as the sampling criterion, over 90% of new samples would densely cluster around the existing samples rather than in regions of high nonlinearity or high gradient changes in the true response surface. Similarly, Schöbi et al. [

30] found in knee cartilage constitutive model calibration that variance-guided sampling reduced the prediction interval coverage of a fiber direction modulus from 95% to 67%, indicating that the model misjudged the physical mechanisms in unsampled regions. While bootstrap resampling methods [

31] can improve the variance estimation robustness through ensemble Kriging models, they require repeated model fitting (typically hundreds of iterations) and still fail to address the fundamental bias-variance decoupling issue. For instance, in [

31]’s geotechnical case study, bootstrap-enhanced variance estimates showed limited improvement in the discontinuous regions despite a significant computational overhead.

The deeper contradiction stems from the mismatch between the variance criterion and the modeling objective: Kriging variance is essentially a geometric measure of interpolation uncertainty in blank regions, while the modeling task requires statistical control of the global prediction error. For example, in climate model simplification surrogate modeling, Lataniotis et al. [

32] pointed out that variance-guided sampling would cause the prediction confidence interval of tropical cyclone generation thresholds to miss the key phase transition points because it did not consider the nonlinear sensitivity differences of the model near the threshold. In this case, a hybrid sampling criterion based on prediction error gradients can more effectively identify model structural defect regions [

33]. To address this issue, this paper integrates prediction bias as a compensation term, introducing a bias-variance synergy mechanism, considering both the uncertainty represented by variance and the prediction bias caused by the model’s inaccuracy during the adaptive sampling process of the Kriging model.

Secondly, the traditional LOOCV method overlooks the spatial correlation of sample points. How to quantify the prediction bias of the model is one of the key issues in improving the accuracy of adaptive sampling. Leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) is a method for evaluating the model bias. Although LOOCV can reflect the stability of the model in single-point prediction, its core defect lies in ignoring the synergistic effect of spatial correlation on the prediction bias. The existence of spatial autocorrelation directly violates the independence assumption of LOOCV. Le et al. [

34] pointed out that when data exhibit spatial clustering or gradient distribution, LOOCV systematically overestimates the model prediction performance due to the spatial dependence between the validation set and the training set, which allows the model to “anticipate” the characteristics of the validation samples, thereby weakening the objectivity of bias assessment. Similarly, Juergen and Marcelo [

35] found in tropical ecosystem data research that traditional LOOCV could introduce an error estimation bias of up to 28% for rare species distribution models, while introducing spatial block partitioning in cross-validation reduced the bias to below 5%, further verifying the interference of spatial association with the reliability of LOOCV. Maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) methods [

36] attempt to address the spatial dependence through explicit covariance modeling, but their effectiveness heavily relies on assumptions of data distribution (e.g., Gaussianity). As showed in [

36], MLE-based spatial models exhibited significant performance degradation when handling non-stationary cloud-cover patterns. This highlights the challenge of balancing theoretical rigor with adaptability in spatial bias quantification.

The deeper reason lies in the fundamental conflict between the statistical basis of LOOCV and the essential characteristics of spatial data. Zhang et al. [

37] theoretically proved that the independent and identically distributed assumption of LOOCV is incompatible with the spatial dependence network of geographical data—after removing a sampling point, its unsampled spatial neighborhood still influences the prediction residual of the current point through spatial autocorrelation mechanisms such as Moran’s I. For example, Hanna and Edzer [

38] demonstrated that when the spatial autocorrelation coefficient exceeds 0.6, LOOCV overestimates the coefficient of determination (R

2) of the regression model by more than 0.15, and the error distribution shows significant spatial aggregation. This conclusion is consistent with the empirical research of Hijmans [

39] in the field of ecology: in species distribution modeling, LOOCV ignoring spatial dependence mistakenly identifies overfitting as model robustness. To address this defect, this paper considers the spatial neighborhood set of sample points and proposes a spatially corrected weighted bias estimator based on KNN by integrating LOOCV and the KNN algorithm.

Finally, the static candidate set strategy significantly constrains the model convergence efficiency. The inherent conflict between its fixed parameter configuration and dynamic modeling requirements has been widely demonstrated across multidisciplinary modeling studies. The conventional approaches typically predefine the parameter distributions or sampling densities in candidate sets (e.g., uniform grids, fixed confidence intervals), resulting in the model’s inability to capture the dynamic evolution of sensitive regions during later iterations. Kennedy [

40] demonstrated that fixed candidate sets generate approximately 35% invalid sampling points during the model calibration stages—these parameter combinations are filtered out via computationally intensive high-fidelity model evaluation processes due to their deviation from the high-probability parameter regions.

This phenomenon fundamentally stems from the phase-dependent characteristics of modeling processes, which demand dynamic adaptability in candidate sets: the early stages require the comprehensive coverage of the global possibilities in the parameter space, while the later stages necessitate focused fine-tuning in the critical response regions. Nevertheless, static strategies fail to satisfy such progressive modeling demands. While Bayesian optimization methods [

41] dynamically adapt the sampling regions through posterior updates, they require computationally expensive posterior recalculations, making them impractical for high-dimensional or time-sensitive applications. To address this challenge, this paper proposes a dual candidate set dynamic balancing strategy that intelligently explores the design space to capture the most sensitive regions.

Probabilistic machine learning methods—ranging from simple bootstrapping to maximum likelihood estimation—have demonstrated significant value in enhancing the interpretability across disciplines [

31,

36,

41]. While these probabilistic methods enhance the interpretability, their computational and distributional constraints limit the effectiveness in adaptive sampling. To overcome these limitations while addressing the above three issues, this paper proposes a Kriging modeling adaptive sampling method based on KNN through maximizing the weighted expected prediction error (KMWEPE), with the following contributions:

- (1)

This paper introduces a bias–variance decomposition strategy, decomposing the expected prediction error of candidate points into the sum of bias and Kriging variance, considering both the prediction bias caused by the model’s inaccuracy and the uncertainty represented by the variance, thereby solving the problem of limited spatial exploration capability due to the over-reliance on the variance in the sampling methods. At the same time, the KNN algorithm based on the Euclidean distance between sample points is introduced, and K-nearest neighbor samples are determined based on the spatial correlation. The weighted sum of LOOCVE of K-nearest neighbor samples is used to quantify the bias, reducing the error caused by traditional LOOCV methods ignoring the spatial correlation.

- (2)

A dual candidate set dynamic balance strategy is proposed to achieve a balance between global exploration and local exploitation. This paper defines the local most sensitive region with the highest uncertainty based on LOOCVE and the distance between the sample points, and dynamically updates the local most sensitive region in each iteration based on prior information. Two sets of candidate points are generated in this region and the global design space, respectively, improving the convergence efficiency of modeling.

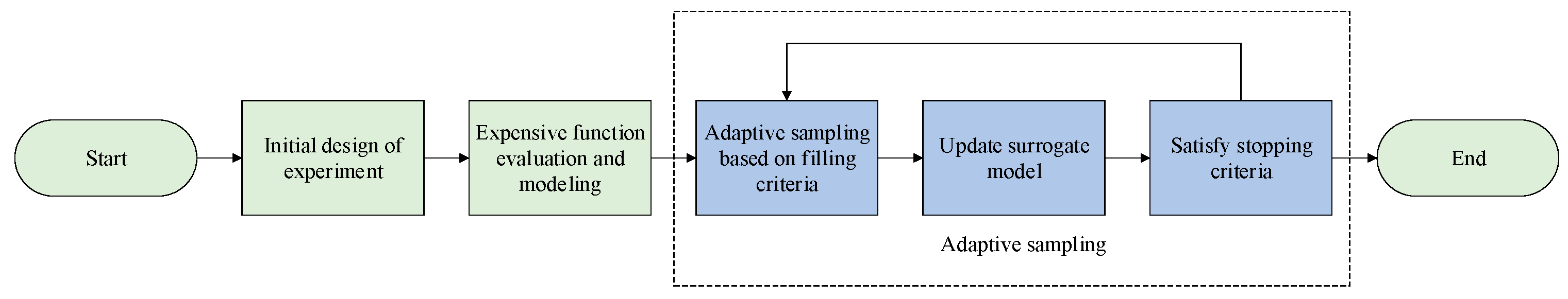

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 provides a brief overview of Kriging and the general process of Kriging modeling and adaptive sampling, and introduces the basic content of the KNN algorithm and bias–variance decomposition. In

Section 3, the KMWEPE method proposed in this paper is introduced, and the flowchart and specific steps of the method for modeling are provided.

Section 4 demonstrates the effectiveness of the method with six benchmark test functions and two engineering application examples. Finally, the main conclusions of this work are given in

Section 5.

3. The Proposed KMWEPE Method

This paper proposes a novel adaptive sampling strategy, namely KMWEPE. In this section, the specific details and flowchart of the KMWEPE method will be provided, including the criterion for balancing local exploitation with global exploration and the method for calculating the weighted expected prediction error.

3.1. Criterion for Balancing Local Exploitation with Global Exploration

In the adaptive modeling process, the static candidate set significantly impedes the convergence efficiency of the model. Consequently, it is imperative to dynamically update the candidate set based on the information obtained during the model iterations. At the same time, it is essential to consider how to achieve the dynamic balance between local exploitation and global exploration. For example, Zhao et al. [

48] decided whether subsequent sampling favors local exploitation or global exploration based on the comparison of the cross-validation error between the current iteration and the last iteration.

Local exploitation refers to searching for some interesting regions (such as areas with large errors) in the design space and the sampling within these local regions to obtain informative sample points. For example, Liu et al. [

49] divided the design space into several Voronoi cells and quantified the uncertainty of each cell via the LOOCVE of the sample point within the cell. And then, the sample with the highest uncertainty in the cell is filtered. The advantage of local exploitation is that the search space is limited to some local regions where the Kriging model differs significantly from the real model, and the sampling in these local regions can accelerate the construction of high-precision models.

Global exploration refers to sampling in the design space to avoid certain promising regions not being explored. The high accuracy for modeling refers to the global accuracy. Indeed, local exploitation can be considered as another form of global exploration, which involves searching for points with global characteristics within local regions. Both aim at improving the global accuracy of the model.

A novel criterion for balancing local exploitation with global exploration is proposed in this paper. For each iteration, two sets of candidate points are generated in the most sensitive region and the design space, respectively. Then, the WEPEs of all candidate points are calculated, and the point with the largest WEPE is selected from each set of candidate points. Finally, the WEPEs of the two points are compared, and the point with the larger WEPE is selected as the new sample point (the calculation method of WEPE is shown in

Section 3.2). If the point comes from the candidate points in the most sensitive region, the current iteration favors local exploitation; if the point comes from the candidate points in the design space, the current iteration favors global exploration.

For local exploitation, the prior information from previous iterations is used to direct the current iteration. In each iteration, the LOOCVE for each known sample point is calculated. A larger error indicates higher uncertainty in the area around the sample point. Therefore, the sample point with the largest error is selected as the center point

, and the distance between

and the nearest sample point to

is used as the radius

r. The hypercube formed by the center point

and the radius

is the most sensitive region

(as shown in Equation (19)), implying high uncertainty in this region. In order to identify the region with the highest uncertainty in

, a complete exploration is required in the entire region. Therefore, LHS is used to generate a set of local candidate points

within

to ensure that the sample points in

are uniformly distributed within

. The WEPE for all points in

is calculated, and the point with the largest WEPE is selected as the iterative point

for local exploitation.

The uniformly distributed initial sample points obtained via LHS ensure that all the areas in the design space are sampled, and the screening of local candidate points

ensures the exploration of regions with high uncertainty. Therefore, for global exploration, Monte Carlo Random Sampling is used to generate a second set of candidate points

to ensure that each sample point in the design space has an equal chance of being selected, thus reducing the sampling bias. Similarly, the WEPE of all points in

is calculated and the point with the largest WEPE is selected as the iterative point

for global exploration.

Compare the WEPE of

and

, and select the point with the larger value as the new sample point

for the current iteration, i.e.,

If

, it indicates that the region around

in

has higher uncertainty, so then, the current iteration favors local exploration; if

, it indicates that some promising regions near

have not been explored, so then, the current iteration favors global exploration.

3.2. The Method for Maximizing the Weighted Expected Prediction Error

The calculation method for the weighted expected prediction error is introduced in this subsection.

To mitigate the over-reliance of the sampling criterion on the variance, a bias term is introduced to enhance the model’s exploratory capability across the design space. As mentioned in

Section 2.4, the bias–variance decomposition converts the expected prediction error at any candidate point into the sum of bias and variance. The variance can be predicted directly via Kriging, while the bias is the difference between the true value and the expectation of prediction value. The prediction value can also be predicted directly by using the Kriging model, but the true value is unknown. Therefore, it is necessary to consider other methods to calculate the bias of candidate points.

One of the characteristics of adaptive sampling is that it uses information obtained from the previous iterations to direct the subsequent iterations. Therefore, prior information can be used to calculate the bias of the candidate points in the subsequent iterations. In this paper, the Euclidean distance-based KNN algorithm is introduced to address the spatial correlation neglect in the traditional LOOCV’s impact on the model performance. For each candidate point, KNN selects the K-nearest neighbor sample points based on the Euclidean distance.

Theoretically, a closer distance between an unknown candidate point and a known sample point indicates a higher correlation between them, i.e., the error at the known sample point reflects the uncertainty at the unknown candidate point to a greater extent. Therefore, for each candidate point, the weighted average sum of the LOOCVEs of the

K sample points is used to replace the bias of the candidate point rather than the arithmetic sum. For a sample point closer to the candidate point, the error of that sample point should be assigned a greater weight, which is obviously a negative correlation. Consequently, the inverse proportion method is used to calculate the weights of each sample point (the weight calculation is detailed in

Section 4.3). The weights of all sample points are normalized so that the sum of the weights is 1, as shown in Equation (24),

where

denotes the weight assigned to the

nearest neighbor sample point, and

denotes the distance between the candidate point

and the

nearest neighbor sample point to point

.

The weighted sum can also be calculated to obtain the bias of the candidate point

, as shown in Equation (25).

where

denotes the leave-one-out cross-correlation validation error of the

nearest sample point to the candidate point

. The variance

of the candidate point

is predicted via Kriging. Then, the arithmetic sum of the bias

and the variance

is used to construct a new function,

, for calculating the expected prediction error of point

x. And the expected prediction error of point

x is termed as the weighted expected prediction error of point

, which quantifies the uncertainty of the candidate point

, as shown in Equation (26). Note that in “the weighted expected prediction error”, the term “weighted” refers to the weights of leave-one-out cross-validation errors when calculating the bias, rather than the weights of the bias and variance.

Therefore, in the adaptive sampling process, the maximization of the weighted expected prediction error is used as the filling criterion to identify the new sample point

, as shown in Equation (27).

3.3. Implementation of the KMWEPE Method

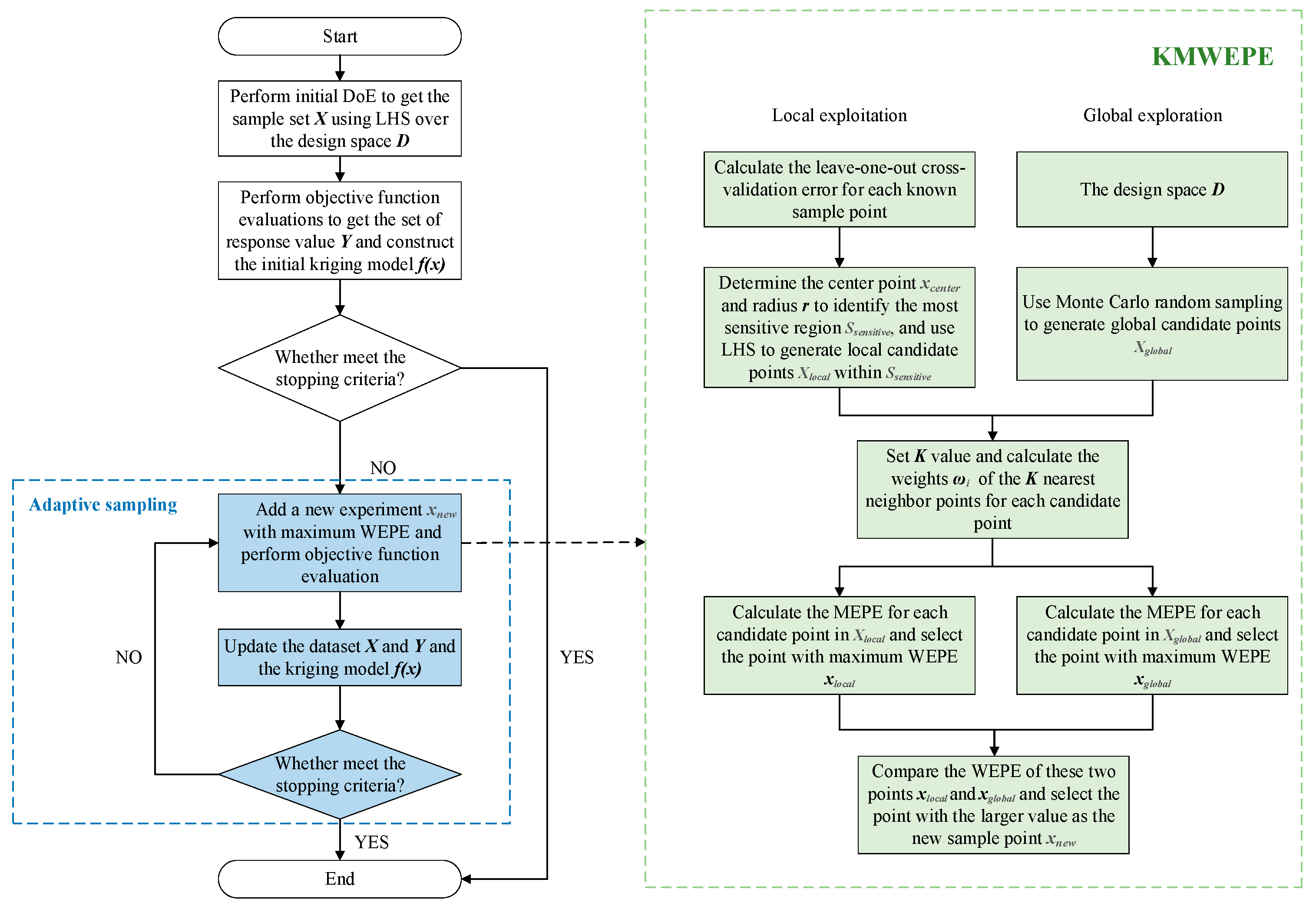

The KMWEPE method proposed in this paper is shown in

Figure 2. The details of the specific steps are as follows:

Step 1: The initial DoE is performed via LHS to obtain the initial sample set , ensuring that the initial sample points are uniformly distributed in the design space. The number of initial sample points should be enough for constructing an effective initial Kriging model to provide sufficient prior information for the subsequent iterations. Conversely, an excessively large number may lead to overlapping information, which has a limited effect on the model accuracy. Therefore, the number of initial sample points in this paper is 5 times the dimension of the function, i.e., (where refers to the dimension of the real function).

Step 2: Expensive function evaluation is conducted on the sample set to obtain the response set . Based on the input data and output data , the initial Kriging model is constructed by using Kriging interpolation.

Step 3: Determine whether the current Kriging model satisfies the stopping criterion. If so, then the iteration ends; if not, proceed to step 4.

Step 4: Calculate the LOOCVE for each known sample point in , and select the sample point with the largest error as the center point . The distance between and the nearest sample point to is used as the radius r, and the most sensitive region is identified by the center point and the radius . LHS is used in to generate a set of local candidate points , and Monte Carlo Random Sampling is used in the design space to generate a set of global candidate points . Note that and are resampled in each iteration.

Step 5: Set the value of K. For each candidate point in and , calculate the Euclidean distance between the candidate point and all the sample points. Select the K-nearest neighbor sample points, and calculate the weights of these K sample points based on the inverse proportion method.

Step 6: Obtain the prediction variance s2 of each candidate point in and based on the updated Kriging model (if it is the first iteration based on the initial Kriging model), and calculate the WEPE of each candidate point based on Equation (26). Select the candidate point with the largest WEPE in and respectively, denoted as and .

Step 7: Compare the WEPE of these two points, and , and select the point with the larger value as the new sample point .

Step 8: Perform the expensive function evaluation of point to obtain its response value , and add and to the dataset and , respectively. Update the Kriging model and determine whether the current Kriging model satisfies the stopping criterion; if so, then the iteration ends; if not, proceed to step 4.

4. Discussion

In this chapter, a comprehensive discussion is presented on various aspects of the proposed KMWEPE method. The discussion encompasses the selection process of the K-value, the identification of the local most sensitive regions, the calculation method for the weights in the bias term of KNN prediction, the balance between the modeling accuracy and efficiency, and a series of tests.

To demonstrate the universality and effectiveness of KMWEPE, a series of tests were conducted using six benchmark functions, two publicly available datasets from the UCI repositories, and two engineering examples. The LHD and MEPE methods were also employed for comparative analysis.

Four distinct types of functions were selected for testing in order to test the impact of the proposed KMWEPE method on different types of functions. The first type of test functions is the multi-peak function represented by the Alpine01 function, which usually has multiple local minimum points and multiple peaks, making the modeling process more challenging. The second type is the plate-shaped function represented by the Zakharov5 function, which usually has a flat or plateau-like shape in certain regions. In flat regions, the function values remain constant within a certain range. In contrast, in plateau regions, the function values usually remain relatively constant in a certain region and then change drastically. The third type is the valley-shaped function represented by the Sixhump function, where the image of this type of function presents a downward concave shape, similar to the contour of a valley. The last type is other functions, including Colville, Hartman3, and Hartman6 functions.

4.1. Selection Process of the K-Value

The calculation of the bias of candidate points in KMWEPE is based on the KNN algorithm, and the value of K in KNN has a significant impact on the experimental results, which is often set artificially. In order to make the KMWEPE method more universal, the value of K should be different for the objective functions with different dimensions. Therefore, the value of K set in this study is proportional to the dimension of the objective function. Additionally, as the number of sample points set in the initial DoE is 5D (D here refers to the number of dimensions), i.e., in the first adaptive sampling process, the maximum number of samples that can be utilized is 5D. Consequently, the value of K is set to 1D, 2D, 3D, 4D, and 5D. Furthermore, due to the limitation of the number of initial sample points, and also taking into account the possibility that a greater number of sample points for obtaining information leads to a better modeling effect, this study adds another set of comparison experiments—K = all. In this case, K represents the number of all points in the current dataset (i.e., when applying KNN in each iteration, use all sample points in the current dataset to calculate the bias). The effect of each value of K on the results is compared in the subsequent experiments to further determine the optimal value of K.

In order to reduce the impact of sampling randomness on the experimental results, the KMWEPE approach was conducted with 100 independent repeated experiments of each test function for each of the six values of

K. The number of sample points in the initial DoE is 5D, and the number of updated points added in the adaptive sampling is 6D. The mean and standard deviation of the RMSE for 100 independent repeated experiments are used as evaluation indicators. The experimental data are presented in

Table 1, and the best results of the experiments for each benchmark function are highlighted in bold.

From the test results in

Table 1, it can be seen that in the six groups of experiments, when

K takes 5D, the RMSE mean value demonstrates a superior performance on the four test functions, including Alpine01, Sixhump, Colville, and Hartman6. For the other two test functions, Hartman3 and Zakharov5, the test results for

K = 5D are only slightly worse than

K = all. As for the RMSE standard deviation, except for the Hartman3 function where the standard deviation is twice as large when the value of

K is taken as 5D compared to the other five sets of experiments, the standard deviations of the other five test function experiments show no significant variation. Therefore, it can be inferred that among the six

K-values, the modeling effect is best when the value of

K is 5D.

From a statistical perspective, further validation of the optimal value of K is conducted. To eliminate the differences in the magnitude of the RMSE across different functions, the RMSE for each function is independently normalized using max-min normalization. A one-way ANOVA is employed to analyze the impact of dimensionality on the value of

K, as shown in

Table 2. Initially, a Levene’s test is performed, yielding a

p-value of 0.2291, which is greater than 0.05, indicating that the homogeneity of variances is confirmed by Levene’s test, satisfying the ANOVA assumption. Subsequently, a one-way ANOVA is conducted, resulting in a

p-value of 8.39349 × 10

−9, which is less than 0.001, indicating an extremely significant difference between the groups, meaning that the value of

K has a significant impact on the RMSE. The effect size calculation yielded η

2 = 0.77, reflecting the proportion of variance between the groups to the total variance, indicating that the intergroup differences accounted for 77% of the total variance, which is considered a large effect. Compared to other values (1D, 2D, 3D, 4D, and all), the RMSE mean for

K = 5D decreased by 14.4%, 30.0%, 12.8%, 6.4%, 31.95%, and 7.4% across the six test functions, with an average decrease of 17.15%. Therefore, from a statistical standpoint, it is also demonstrated that the optimal value of

K is 5D.

4.2. Identification of the Local Most Sensitive Regions

During the adaptive sampling process, it is more likely to search for informative sample points in areas with higher uncertainty. The KMWEPE method identifies the local most sensitive regions using the sample point with the largest LOOCVE and its distance to the nearest neighbor. However, this approach may simplify the complex uncertainty of the black-box function. Therefore, this subsection explores the identification of the local most sensitive regions through three metrics: the KMWEPE method, variance gradient, and gradient-based sensitivity.

All three metrics establish the local most sensitive regions by determining the center point and the radius, with the radius being determined by the distance between the center point and its nearest neighbor sample. The difference lies in the method of determining the center point. In each iteration, the KMWEPE method calculates the LOOCVE for all the sample points and uses the sample point with the largest LOOCVE as the center point. The variance gradient (VG) method calculates the partial derivatives of the predicted variance of the sample points in each dimension to obtain the gradient vector, and selects the point with the largest variance gradient magnitude as the center point. Gradient-based sensitivity (GBS), on the other hand, calculates the gradient of the function values of the sample points, and the sample point with the largest gradient magnitude is selected as the center point.

During a complete experiment involving multiple iterations, for each iteration, the local sensitive regions are identified using the aforementioned three methods. Within the local most sensitive region determined in the current iteration, 100D sample points are generated using LHS, and the RMSE value of the current model is calculated. The arithmetic mean of the RMSE values obtained throughout all the iterations of a complete experiment is calculated, as shown in

Table 3.

As can be observed from

Table 3, among the six test functions, the KMWEPE method yields the highest RMSE mean for the candidate points within the identified local most sensitive regions. This indicates that, compared to the VG and GBS methods, the local most sensitive regions determined by using KMWEPE exhibit the highest level of uncertainty. The sampling within these regions can potentially reduce the model error more rapidly.

The variance gradient method relies on the accuracy of the surrogate model; in sparse sample regions, the variance gradient may be falsely amplified. Gradient-based sensitivity is more applicable to smooth regions and is unstable under discrete data or noise interference. Large gradients may indicate local oscillations (such as high-frequency noise) and do not necessarily correspond to critical regions. Gradient-based methods only contain first-order information, reflecting instantaneous rates of change. In contrast, LOOCV directly quantifies the model’s generalization ability in local regions by assessing the reconstruction error after sample point exclusion. It incorporates the influence of function values, gradients, and curvature, and reduces the dependence on individual samples through multiple resampling, thereby demonstrating more reliable performance in identifying sensitive regions.

4.3. Calculation Method for the Weights

The KMWEPE method employs an inverse distance weighting scheme to compute the bias from KNN-selected LOOCVE values, assuming a uniform decay of spatial influence. However, the design space of practical problems may not be uniform, and using an inverse distance weighting scheme may lead to estimation biases in regions with heterogeneous correlation structures. Therefore, this subsection discusses the weighting calculation methods for different spatial correlation functions.

Four methods are used to calculate the weights of candidate points: Inverse Distance (ID), Exponential Decay (ED), Gaussian Decay (GD), and Inverse-Square Distance (ISD). The ID method exhibits the uniform decay of weights with increasing distance; the ED method features strong correlation at close distances and weak correlation at far distances, with weights decaying exponentially—rapidly at first and then leveling off; the GD method’s weights decay exponentially with the square of the distance, starting gently and then dropping sharply, providing a more balanced weight distribution for intermediate distances; and the ISD method’s weights decay inversely with the square of the distance, more steeply than when using the ID method. Based on these four methods, the weights of candidate points are calculated to compute the bias. Ten independent repeated experiments were conducted on six test functions. The RMSE mean was used as the evaluation metric, and the test results are shown in

Table 4.

The Alpine01 function exhibits a highly heterogeneous space, featuring multiple periodic sharp peaks with significant variations in the rate of change across different regions, and a nonlinear correlation decay. The Sixhump function presents moderate heterogeneity, with six local extrema, alternating flat and steep regions, and regionally dependent correlation structures. The Hartman3 function is locally homogeneous, consisting of the superposition of four Gaussian peaks, with uniform correlation decay within each peak but abrupt changes in the correlation between peaks. The Colville function exhibits complex heterogeneity, with multiple interacting terms and anisotropic correlation structures in different directions. The Zakharov5 function is globally homogeneous, with its overall correlation decaying uniformly. The Hartman6 function is highly localized, comprising a combination of six-dimensional Gaussian peaks, with strong internal correlations within each peak and rapid decay to zero outside the peaks.

As can be observed from

Table 4, among the six sets of experiments, the ED method demonstrates the optimal performance on the Alpine01, Sixhump, Hartman3, and Colville functions, while the ID method exhibits the optimal performance on the Zakharov5 and Hartman6 functions. For the globally homogeneous Zakharov5 function, the ID method significantly outperforms the other three methods, and it also shows a good performance on the locally homogeneous Hartman3 and Hartman6 functions. It can be inferred that the ID method is suitable for cases with uniform spatial correlation. When calculating the bias of KNN predictions, a

K-value of 5D is used, meaning that the local region encompasses the 5D nearest neighbor samples of the candidate point. This approach excludes the consideration of distant regions in the design space, thereby focusing exclusively on the local spatial correlations around the candidate point. Consequently, the ED method, which emphasizes strong near-distance correlations, demonstrates a superior performance across all the four test functions.

In practical problems, the characteristics of the design space vary, and when calculating the weights of neighboring samples for candidate points, it is crucial to choose different weighting methods based on the characteristics of the design space. For functions with uniform spatial correlation, the inverse distance method should be selected to calculate weights, whereas for functions with strong spatial correlation decay, exponential decay will be a better choice.

4.4. Balance Between Modeling Accuracy and Efficiency

In the modeling process, there is typically a trade-off between the modeling accuracy and modeling efficiency. An improved modeling accuracy is often achieved at the expense of reduced modeling efficiency, and vice versa. Striking an optimal balance between these two factors is a critical consideration in the modeling process.

To demonstrate how the KMWEPE method balances the accuracy and efficiency, another adaptive sampling method—MEPE (Maximization of the Expected Prediction Error)—is selected for comparative testing. The experimental results of MEPE and KMWEPE are analyzed to evaluate their respective performance in terms of accuracy–efficiency trade-offs.

The LHD, MEPE, and KMWEP methods are evaluated across six test functions. To ensure statistical robustness, both the mean value and standard deviation of the RMSE from 100 independent repeated experiments are also employed as evaluation metrics, with the comprehensive experimental results detailed in

Table 5. Since LHD is a non-adaptive sampling method, the comparative analysis focuses exclusively on the accuracy–efficiency trade-off between the MEPE and KMWEPE methods.

According to the experimental data in

Table 5, compared to the MEPE method, KMWEPE shows the best performance in terms of the RMSE mean value across the six test functions, and has a better RMSE standard deviation across the three test functions, including Sixhump, Zakharov5, and Hartman6. The RMSE standard deviation across the other three test functions, including Alpine01, Hartman3, and Colville is only slightly inferior to MEPE, indicating that KMWEPE has a better performance in regard to the modeling accuracy.

However, MEPE is a single-candidate-set method that dynamically generates one candidate set per iteration, whereas KMWEPE employs a dual-candidate-set strategy by simultaneously generating candidate sets in both the global design space and local most sensitive regions during each iteration. The size of each candidate set is consistently set to 100D. Consequently, while KMWEPE achieves an improved modeling accuracy compared to MEPE, this enhancement comes at the expense of increased computational costs—a typical trade-off in engineering applications where a higher model fidelity justifies additional computational expenditure.

To quantitatively demonstrate the rationality of KMWEPE’s accuracy–computation trade-off, the normalized Precision per Time Efficiency (nPTE) metric is introduced. Since different test functions exhibit varying RMSE magnitudes and computational time requirements, both the relative RMSE improvement and relative time increment are calculated to eliminate scaling effects and hardware-dependent variations. The nPTE calculation formula for comparing the MEPE and KMWEPE methods is presented in Equation (28), with the computed nPTE values for all six test functions summarized in

Table 6.

The physical meaning of nPTE represents the percentage reduction in the RMSE per unit increase in the computational time. For instance, in the case of the Alpine01 function, the KMWEPE method achieves a 23.13% decrease in the RMSE value per additional unit of computation time compared to the MEPE method. As evidenced by

Table 6, all the six test functions exhibit positive nPTE values, demonstrating that the KMWEPE method significantly enhances the modeling accuracy of the Kriging surrogate while incurring only a controlled increase in the computational cost. This systematic improvement confirms that the additional computational resources required via KMWEPE are effectively converted into measurable performance gains, as quantitatively reflected by the reduced RMSE values across all the benchmark functions.

Meanwhile, the nPTE values generally exhibit a decreasing trend with increasing dimensionality, indicating diminishing returns in the precision improvement per unit computational time (with the notable exception of the Zakharov5 function, where the KMWEPE method significantly improves the RMSE mean). This demonstrates that while KMWEPE maintains superior performance over MEPE in higher dimensional scenarios, its marginal benefits decrease progressively with dimension growth. This phenomenon fundamentally reflects the impact of the “curse of dimensionality” on modeling—as the dimensions increase, the computational costs grow exponentially, and while some accuracy improvement is achieved, the rate of the computational cost escalation outpaces the precision gains. Consequently, the KMWEPE method proves particularly effective for low-dimensional problems.

The curse of dimensionality presents significant challenges in high-dimensional modeling. Previous work has addressed the dimension reduction techniques; for instance, principal component analysis (PCA) has been implemented in Kriging modeling to achieve faster modeling efficiency under the premise of meeting certain accuracy requirements [

50]. In the future research, the integration of multidimensional scaling, principal component analysis, and other dimensionality reduction algorithms can be considered within the KMWEPE method. On the one hand, the adaptive sampling process after dimensionality reduction can greatly improve the modeling efficiency and reduce the computational cost. On the other hand, the efficiency of the KMWEPE method in low-dimensional modeling can be fully utilized. Additionally, exploring parallel or distributed computing techniques could further reduce the computational costs and broaden the KMWEPE method’s applicability.

4.5. Publicly Available Dataset Testing

The aforementioned experiments are all based on benchmark test functions. To validate the practicality of the KMWEPE method in real-world engineering problems, this subsection selects two real datasets from the UCI repositories (Auto MPG dataset and Forest Fire dataset) for verification.

The Auto MPG dataset is used for predicting the fuel efficiency, consisting of 398 samples, including seven features and one target variable. The seven features are as follows: cylinders (number of engine cylinders, with common values of 4, 6, and 8); displacement (engine displacement in cubic inches, reflecting the engine size); horsepower (engine horsepower (HP), with some missing values filled with the mean); weight (vehicle weight in pounds, which directly affects the fuel efficiency); acceleration (acceleration performance, i.e., the time required to accelerate from 0 to 60 mph in seconds, where a smaller value indicates faster acceleration); model_year (model year, reflecting technological iteration); and origin (origin code, a categorical variable where 1 indicates made in the USA, 2 indicates Europe, and 3 indicates Japan). The target variable is mpg (miles per gallon), which measures the fuel efficiency, with higher mpg values indicating better fuel economy.

The validation using datasets differs from that using benchmark test functions. When using benchmark test functions, the candidate points are generated from the given design space for selection, allowing for infinite sampling. However, when validating with datasets, the real dataset is finite, and all data points are given. In this case, the essence of the adaptive sampling process is data selection, and the training set and candidate set are continuously updated. For the KMWEPE method, it is not possible to establish the local most sensitive regions when validating with datasets, and thus, high-uncertainty candidate points cannot be generated. Therefore, the adaptive sampling process can only be based on the bias term predicted by KNN, selecting the next iteration point according to the WEPE value, which to some extent limits the improvement of the modeling accuracy by using the KMWEPE method.

Specifically, when validating with the seven-dimensional Auto MPG dataset, 5D samples are randomly selected from the dataset as the initial dataset to establish the initial Kriging model, and the remaining data are used as the candidate set. The WEPE values for all the candidate points are calculated based on the KNN algorithm, the candidate point with the highest WEPE value is selected as the new iteration point, and the Kriging model is updated. The number of sample points added by the adaptive sampling process is 6D.

The Forest Fire dataset is used for predicting the burned area of forest fires, derived from fire records between January 2000 and December 2003 in the Montesinho Natural Park, Portugal. The Forest Fire dataset contains 517 samples, encompassing 12 features and one target variable. Due to the low predictive contribution and high correlation with the core features of some features, this study selects the five most core features from the Forest Fire dataset as input variables: X, Y, month, temp, and RH. X and Y represent the spatial location of the fire area, which is strongly correlated with the fire risk; month represents the time variable, as fires exhibit significant seasonality; temp and RH represent meteorological variables—temperature and relative humidity. The target variable, area, represents the burned area of the fire. Similarly, when validating with the Forest Fire dataset, the initial dataset contains 5D samples, and the adaptive process adds 6D samples. Finally, the remaining data are used as the test set, and the mean and standard deviation of the RMSE from 100 independent repeated experiments are used as the evaluation metrics. The test results for the Auto MPG and Forest Fire datasets are shown in

Table 7.

As shown in

Table 7, compared to the MEPE method, the KMWEPE method still maintains better performance on the five-dimensional Forest Fire dataset and the seven-dimensional Auto MPG dataset without generating a dynamic dual candidate set, which demonstrates the effectiveness of the KNN-based bias term. The bias predicted by KNN explains the true bias of the candidate points to a greater extent, thereby filtering out more informative sample points. On the other hand, without a dynamic dual candidate set, the improvement of the KMWEPE method over the MEPE method is reduced, which also reflects the effectiveness of the local most sensitive region in the dynamic dual candidate set for generating high-uncertainty candidate points.

In conclusion, whether it is for practical engineering problems (such as vehicle fuel prediction in the Auto MPG dataset) or real-world case applications (such as fire area prediction in the Forest Fire dataset), the KMWEPE method can effectively improve the modeling process in relation to prediction, thereby enhancing the prediction accuracy. It holds certain value and significance for global approximation problems based on the Kriging model.

4.6. Benchmark Functions and Engineering Examples’ Testing

This section demonstrates the effectiveness of the KMWEPE method through comparative analysis using both the LHD and MEPE methods.

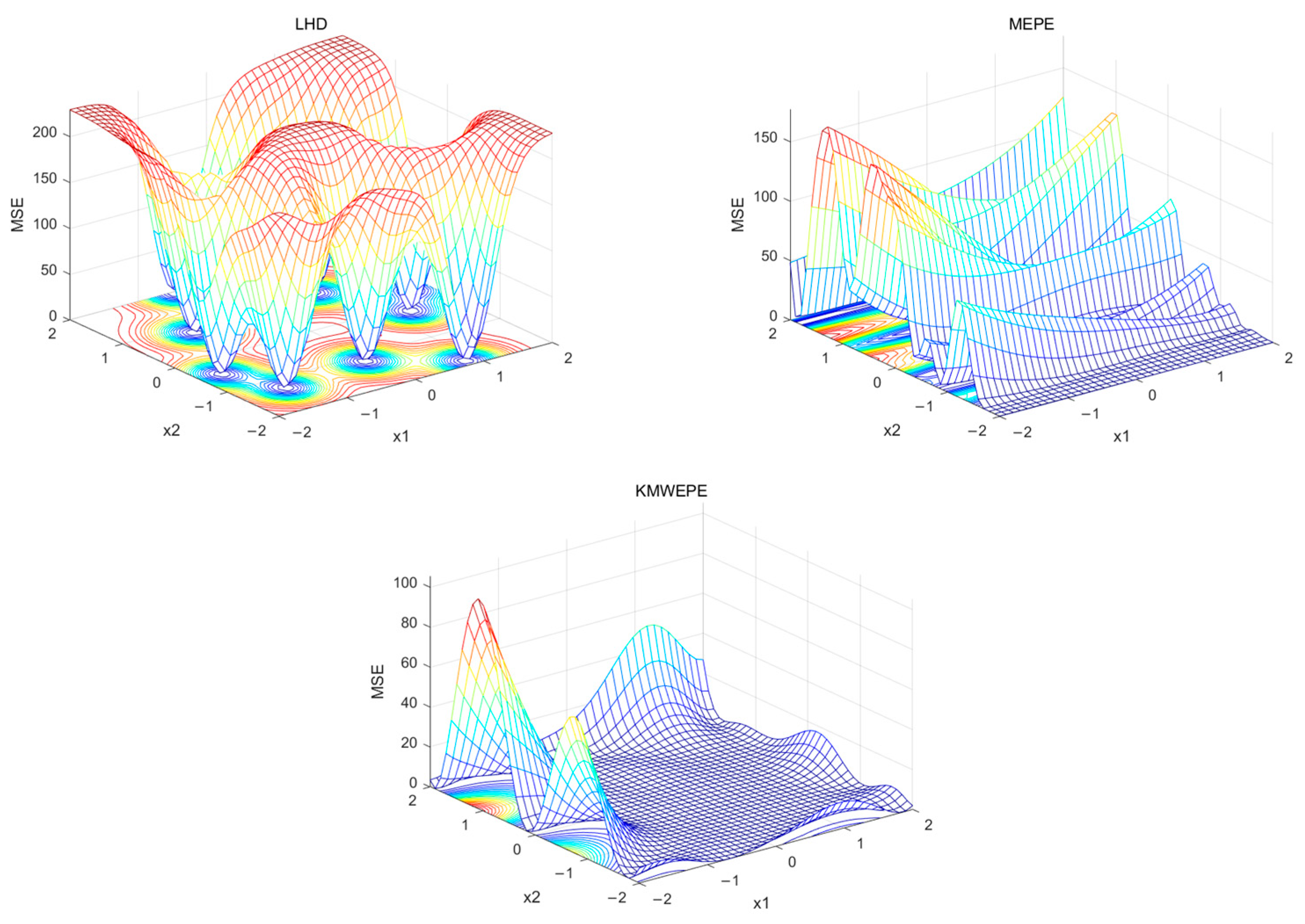

Table 5 presents the experimental results of the three methods. The experimental data provide an objective explanation of the effectiveness of KMWEPE, while images provide a more intuitive observation. For two-dimensional functions, the DACE toolbox can be used to draw the MSE grid curve, which provides a more intuitive representation of the overall MSE of the function and its overall trend of change. This paper first presents the MSE grid curves of the two 2D functions—Alpine01 and Sixhump—after conducting a complete adaptive modeling experiment using the three testing methods, as shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4. The bottom plane is a contour map that reflects the MSE. The color gradient ranges from blue (indicating lower MSE values) to red (indicating higher MSE values), providing a visual representation of how MSE varies across the parameter space.

From

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, it can be observed that for the Alpine01 function, the MSE of the Kriging model obtained via LHD and MEPE are greater than 10 in most areas of the design space, and the changes are relatively drastic. In contrast, the MSE of the Kriging model obtained via KMWEPE are almost all less than 8 in the design space and relatively flat. For the Sixhump function, the MSE of the Kriging model obtained via LHD is above 100 in most areas of the design space, exhibiting a high degree of variability, while the Kriging model obtained via MEPE is extremely non-smooth. In contrast, the MSE of the Kriging model obtained via KMWEPE is close to zero in most regions with only a small portion having a large MSE, and the entire region is also smoother.

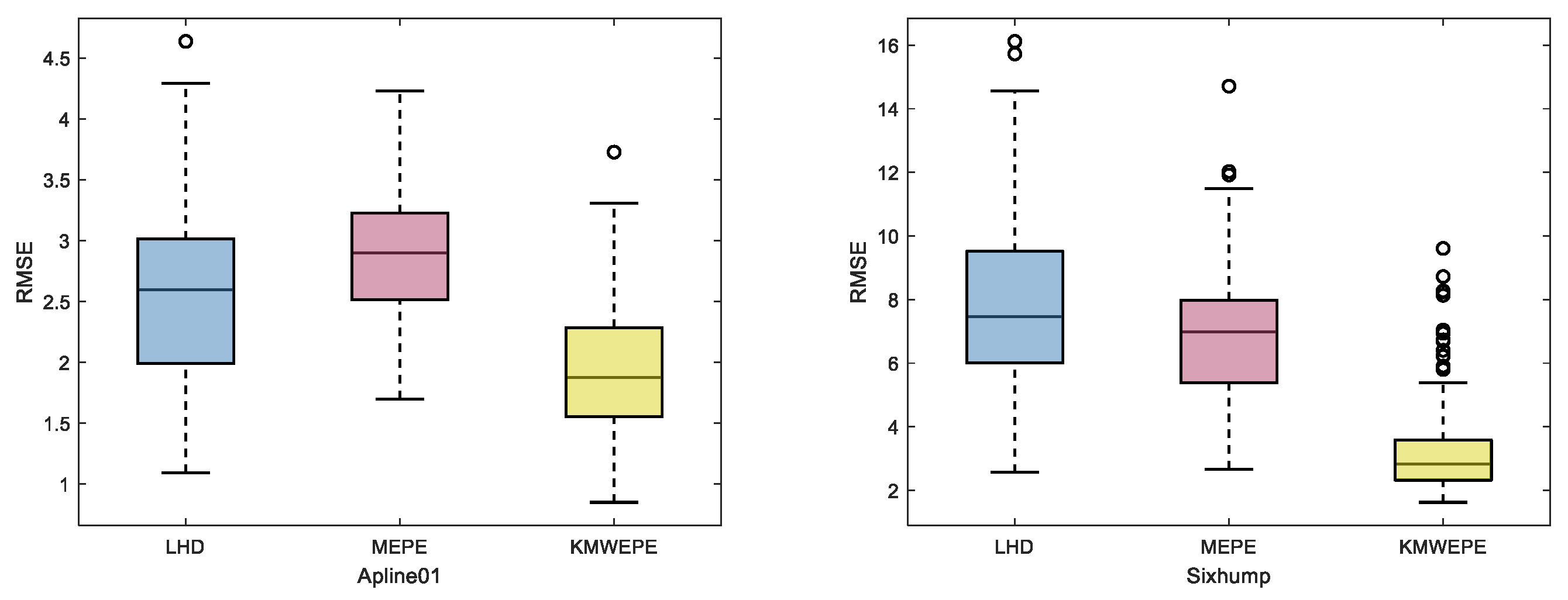

For functions with more than two dimensions, it is difficult to use grid curves to represent the overall trend of the MSE. Therefore, the test results are presented in the form of box plots, as shown in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7.

The box plot shows the distribution and dispersion of data from 100 independent repeated experiments, and the lines inside the box represent the median of the data. As shown in

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7, in the comparison experiments of the three different methods for six test functions, it can be observed that the modeling accuracy of KMWEPE is better than that of LHD and MEPE. Among them, the test results of the Sixhump, Hartman3, and Colville functions via KMWEPE are significantly superior to those of the other two methods, and the other three test functions also demonstrate the effectiveness of KMWEPE to a certain extent. Although some data points of the experimental results via KMWEPE are separated from the box by a certain distance, the data distribution of the test function experimental results via KMWEPE is significantly better than via LHD and MEPE.

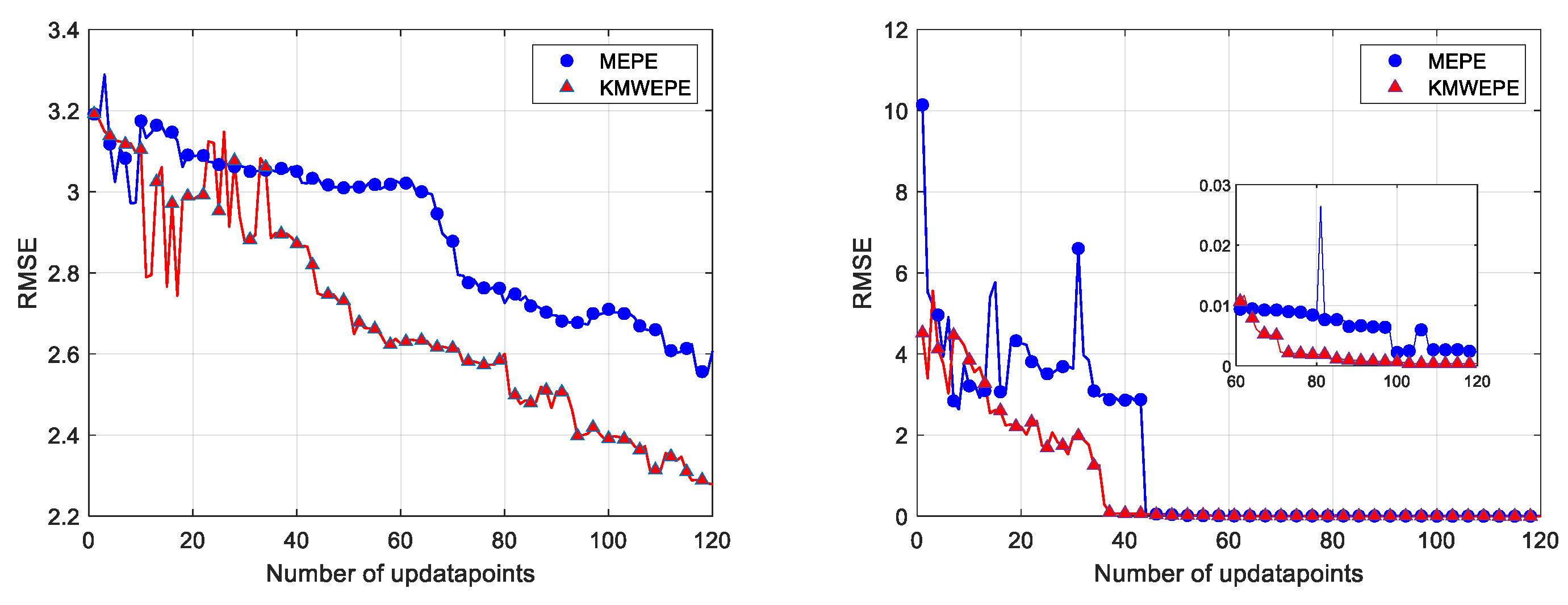

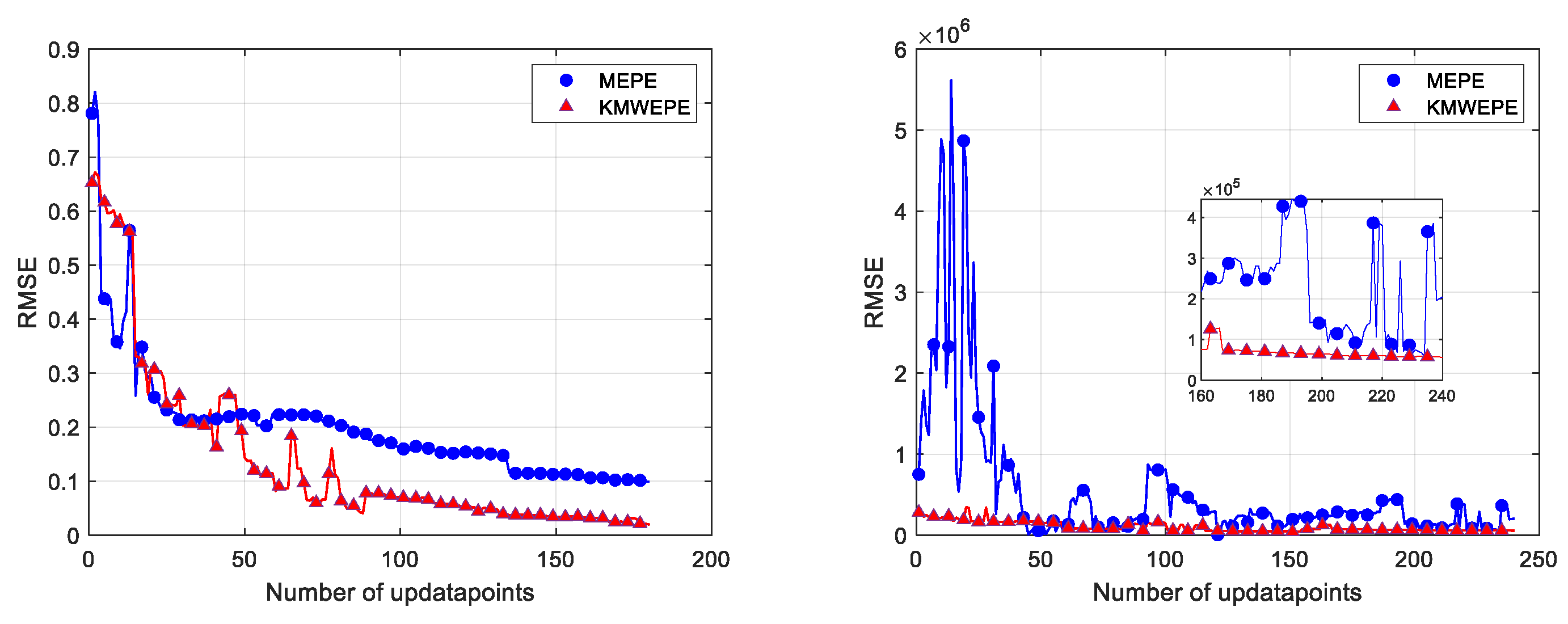

This study also focuses on the convergence trend of the RMSE with the increase in the number of update points in an experiment, and the convergence curves of six benchmark test functions under MEPE and KMWEPE are plotted. The number of sample points in the initial DoE is 5D, and the number of updated points is increased to 60D in order to better observe the convergence trend of the RMSE. As shown in

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10, except for the Alpine01 function, the other five test functions can converge when sufficient updated points are added to the adaptive sampling phase of KMWEPE. Among them, the Colville and Zakharov5 functions showed the best experimental results, achieving convergence in the initial stage of the iteration. The Sixhump, Hartman3, and Hartman6 functions can gradually converge after adding 20D updated points. After achieving convergence, the RMSE obtained via KMWEPE are all less than via MEPE. Even for the Apline01 function that failed to achieve convergence, the modeling accuracy of KMWEPE is better than that of MEPE after adding more than 20D updated points.

From the above analysis, it can be observed that from both the objective experimental data and the intuitive images, KMWEPE shows a better modeling performance compared to LHD and MEPE.

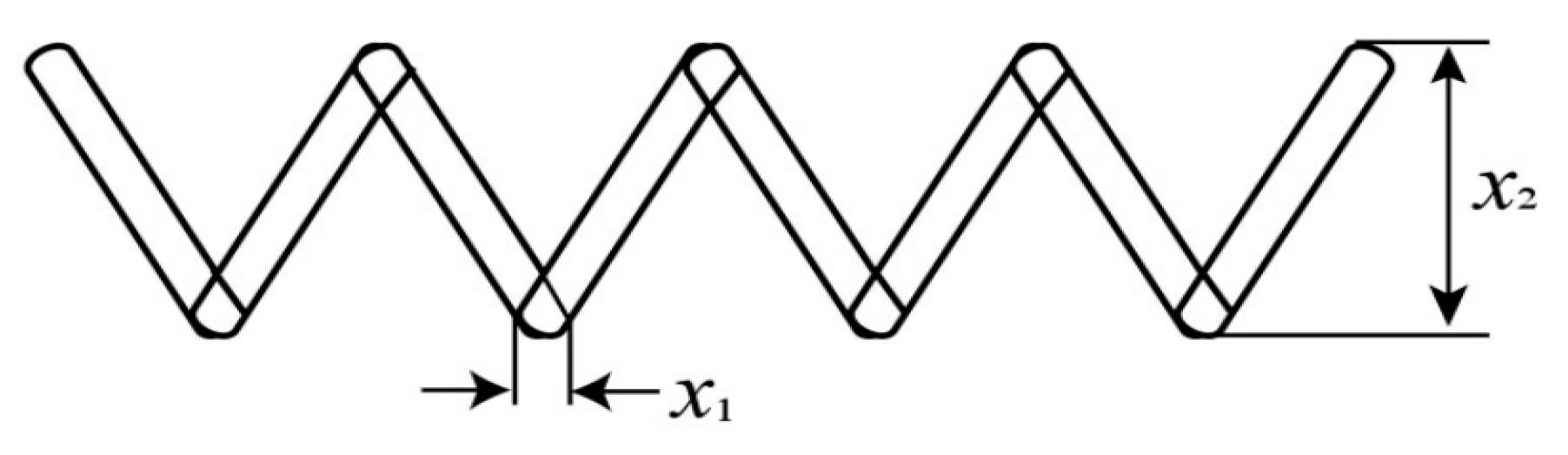

Two engineering examples are also used to demonstrate the effectiveness of KMWEPE. The first engineering example is the design problem of helical tension cylinder springs. The Helical Tension Cylinder Spring (HTCS) is a high-temperature alloy spring with good elasticity and high-temperature resistance, which is suitable for engineering applications in high-temperature environments, such as automotive engines, aerospace, machinery manufacturing, etc. The design schematic of the HTCS is shown in

Figure 11.

The HTCS design problem is a three-dimensional problem with three design variables: the spring diameter

, the average coil diameter

, and the number of active coils

. The response function of this design problem is shown in Equation (29). The HTCS design problem represents a complex engineering optimization challenge, where the primary objective is to minimize the spring weight while satisfying specified performance constraints. This study selects the HTCS problem as a test case precisely because of its inherent nonlinearity and multimodal characteristics, which make it particularly suitable for validating the effectiveness of the modeling methods.

The second engineering example is the Output Transformer Less (OTL) circuit. In traditional power amplifier circuits, the output transformer plays the role of signal transmission and impedance matching, but the output transformer is often expensive and large in size. The OTL circuits are designed to connect directly to the load, eliminating the need for an output transformer and thus reducing the cost and size. OTL circuits are suitable for applications such as audio amplifiers, high-fidelity sound systems, laboratory instruments, and communication equipment.

The OTL circuit design problem is a six-dimensional problem with six design variables of five resistors

and the current gain

. The OTL circuit function models an output transformerless push–pull circuit, and the response is the midpoint voltage

with the expression shown in Equation (31).

As above, the experimental setup involves 100 independent repeated experiments. The number of sample points in the initial DoE is 5D, and the number of updated points in the adaptive sampling phase is 6D. The experimental test results for the HTCS and OTL circuits are shown in

Table 8 and

Table 9.

From

Table 8 and

Table 9, for the spring design problem, the RMSE mean value of MEPE is almost half that of LHD, while the RMSE mean value of KMWEPE is further reduced by nearly half compared to that of MEPE. Additionally, the RMSE standard deviation of KMWEPE is also the smallest among the three methods, which shows that KMWEPE significantly improves the modeling accuracy compared to LHD and MEPE for the spring design problem. For the OTL circuit design problem, the RMSE mean value and standard deviation of KMWEPE are smaller than when using the other two methods. Moreover, as shown in

Figure 12, for the two engineering example design problems, not only the RMSE mean value and standard deviation of KMWEPE are better than those of the other two methods, but the dispersion of the test result data for the 100 independent repeated experiments is also superior. Under the KMWEPE method, all the data for the spring design problem are within the box, and for the OTL circuit design problem, the number of experimental data outside the box are also less than for the other two methods.

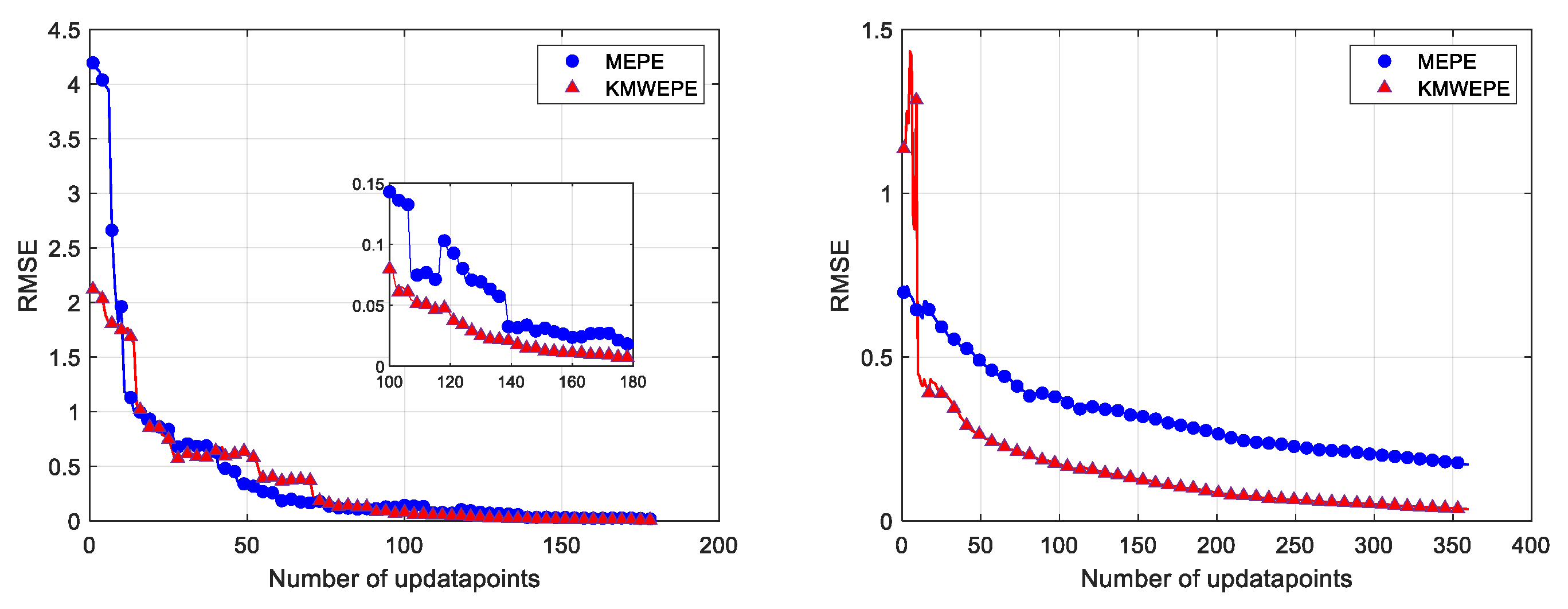

Similarly, the convergence curves of the test results for the two engineering examples are also plotted for a more visual representation of the test results, as shown in

Figure 13. For the spring design problem, although the RMSE of MEPE decreases rapidly and converges quickly during the iteration process, the RMSE of KMWEPE remains lower than for MEPE when the updated point is greater than 30D. For the OTL circuit problem, the RMSE of KMWEPE decreases rapidly, becomes lower than the RMSE of MEPE at the beginning of the iteration process, and maintains the better performance throughout the subsequent iterations.