Effectiveness of a Home-Based Telehealth Exercise Program Using the Physitrack® App on Adherence and Vertical Jump Performance in Handball Players: A Randomized, Controlled Pilot Study

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Type and Design

2.2. Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

2.3. Test Description

2.4. Countermovement Jump (CMJ) Variables

- Jump Height (JH): Main indicator of explosive power; greater height reflects better force application.

- Take-off Velocity: More sensitive to strength improvements than height; reflects efficiency in force-to-movement conversion.

- Peak Power: Calculated from force and velocity of the center of mass; key in strength and explosiveness programs.

- Time to Take-off: Time from the beginning of movement to take-off; a shorter time with equal or greater jump height indicates faster force application.

- Rate of Force Development (RFD): Speed at which force is generated during the concentric phase.

- Flight Time: Directly related to jump height; used in combination with other metrics.

- Modified Reactive Strength Index (mRSI): Ratio between jump height and time to take-off; measures the efficiency of the stretch-shortening cycle. Low values may indicate fatigue or reactive deficits, whereas high values suggest neuromuscular efficiency and reduced joint load.

- Stiffness: Resistance of the muscle-tendon system; excessive or insufficient levels may be associated with a higher risk of injury.

- Time to Stabilization (TTS): Time an athlete takes to regain balance after landing; high values indicate possible neuromuscular deficits, fatigue, or imbalances.

- Peak Propulsive Force: Maximum force generated during the propulsion phase; reflects the potential for maximal force production.

- Propulsive Impulse: Integration of the applied force over time during the propulsion phase; an increase indicates a greater capacity for sustained force application.

- Jump height improvement: Change in jump height.

- Flight time improvement: Change in flight time.

- Peak velocity improvement: Change in peak velocity.

2.5. Adherence Variables and Satisfaction and Usability Questionnaires

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Anthropometric Variables

3.2. Jump Performance (CMJ)

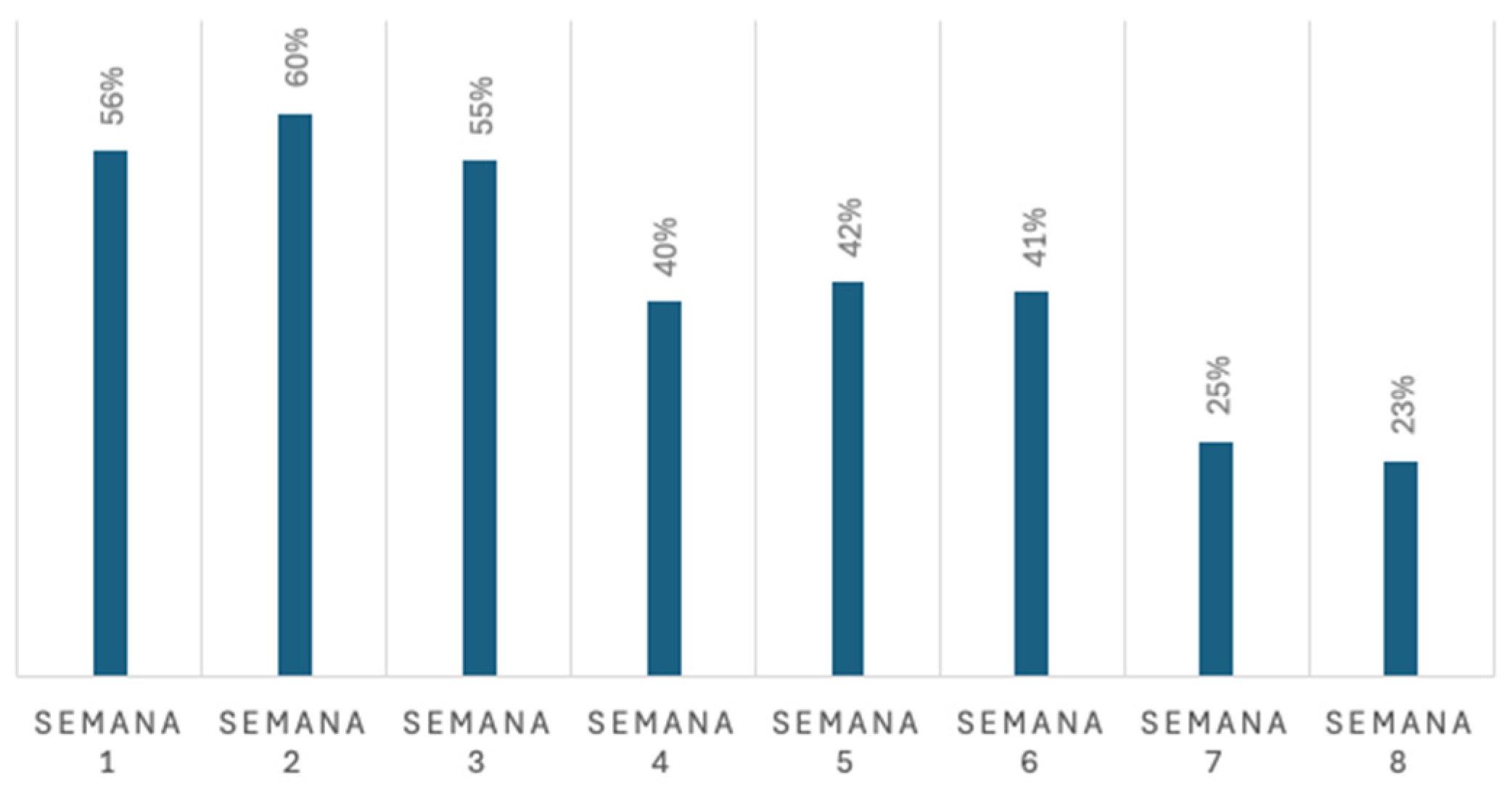

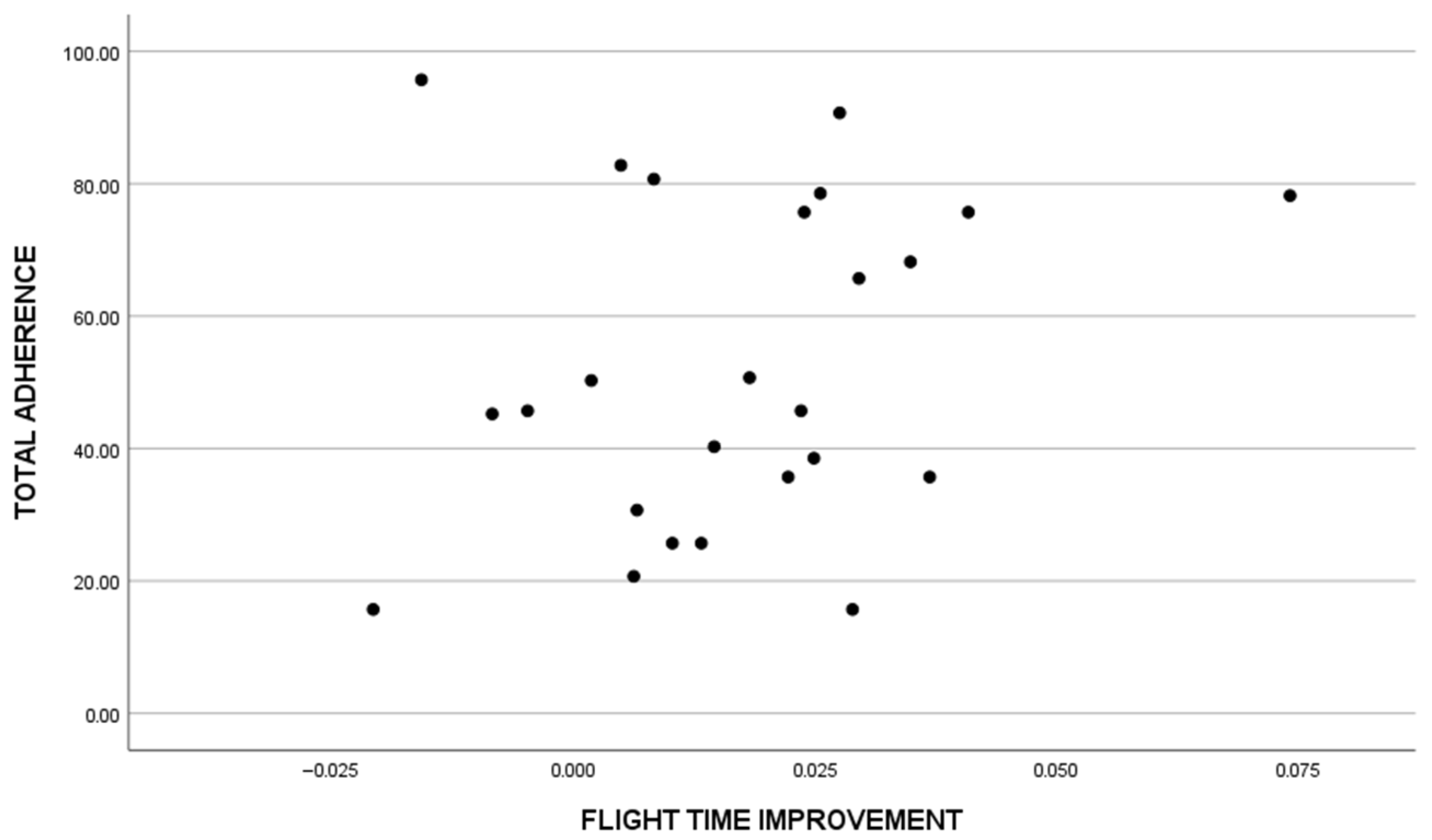

3.3. Adherence

3.4. Satisfaction and Usability Questionnaires

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IG | Intervention group |

| CG | Control group |

| HD | Hawkin Dynamics |

| TSUQ | Telemedicine Satisfaction and Usefulness Questionnaire |

| SUS | System Usability Scale |

| mRSI | Modified Reactive Strength Index |

| RFD | Rate Force Development |

| CMJ | Countermovement jump |

| BMI | Body Mass Index |

| SDT | Self Determination Theory |

Appendix A. Control Group Exercise Program

| Week | Exercise | Series | Repetition | Rest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks 1–2: Initial adaptation | Core plank | 3 | 20–30 s | 30–60 s |

| Hip 90/90 | 3 | 6 reps | 30–60 s | |

| Push-ups | 3 | 6–8 reps | 30–60 s | |

| L-shape raise | 3 | 8 reps | 30–60 s | |

| Bodyweight lunges | 3 | 8 reps per side | 30–60 s | |

| Bodyweight squat | 3 | 8–10 reps | 30–60 s | |

| Weeks 3–4: Moderate increase | Core plank | 3 | 30–40 s | 30–60 s |

| Hip 90/90 | 3 | 8 reps per side | 30–60 s | |

| Push-ups | 3 | 8–10 reps | 30–60 s | |

| L-shape raise | 3 | 10 reps | 30–60 s | |

| Bodyweight lunges | 3 | 10 reps | 30–60 s | |

| Bodyweight squat | 3 | 10–12 reps | 30–60 s | |

| Weeks 5–6: High intensity | Core plank | 4 | 40–50 s | 30–60 s |

| Hip 90/90 | 4 | 10 reps per side | 30–60 s | |

| Push-ups | 4 | 10–12 reps | 30–60 s | |

| L-shape raise | 4 | 12 reps | 30–60 s | |

| Bodyweight lunges | 4 | 12 reps per side | 30–60 s | |

| Bodyweight lunges | 4 | 12–15 reps | 30–60 s | |

| Weeks 7–8: Maximum power | Core plank | 5 | 50–60 s | 30–60 s |

| Hip 90/90 | 5 | 12 reps per side | 30–60 s | |

| Push-ups | 5 | 12–15 reps | 30–60 s | |

| L-shape raise | 5 | 12–15 reps | 30–60 s | |

| Bodyweight lunges | 5 | 15 reps per side | 30–60 s | |

| Bodyweight squat | 5 | 15–20 reps | 30–60 s |

Appendix B. Intervention Group Exercise Program

| Week | Exercise | Series | Repetition | Rest |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weeks 1–2: Initial adaptation | Hurdles jumps | 3 | 8 | 60–90 s |

| Narrow squat jump | 3 | 8 | 60–90 s | |

| Stride jump | 3 | 8 | 60–90 s | |

| Plyometrics—drop jump—two feet on the ground and jump (with arm swing) | 3 | 6 | 60–90 s | |

| Counter move—drop jump—landing on one leg and jumping to the left on two legs (with arm swing) | 3 | 6 (per side) | 60–90 s | |

| Countermovement—drop jump—landing on two feet and jumping over hurdles | 3 | 8 | 60–90 s | |

| Weeks 3–4: Moderate increase | Hurdles jumps | 4 | 10 | 60–90 s |

| Narrow squat jump | 4 | 10 | 60–90 s | |

| Stride jump | 4 | 10 | 60–90 s | |

| Plyometrics—drop jump—two feet on the ground and jump (with arm swing) | 4 | 8 | 60–90 s | |

| Counter move—drop jump—landing on one leg and jumping to the left on two legs (with arm swing) | 4 | 8 (per side) | 60–90 s | |

| Countermovement—drop jump—landing on two feet and jumping over hurdles | 4 | 10 | 60–90 s | |

| Weeks 5–6: High intensity | Hurdles jumps | 4 | 12 | 90 s |

| Narrow squat jump | 4 | 12 | 90 s | |

| Stride jump | 4 | 12 | 90 s | |

| Plyometrics—drop jump—two feet on the ground and jump (with arm swing) | 4 | 10 | 90 s | |

| Counter move—drop jump—landing on one leg and jumping to the left on two legs (with arm swing) | 4 | 10 (per side) | 90 s | |

| Countermovement—drop jump—landing on two feet and jumping over hurdles | 4 | 12 | 90 s | |

| Weeks 7–8: Maximum power | Hurdles jumps | 5 | 10 | 90–120 s |

| Narrow squat jump | 5 | 10 | 90–120 s | |

| Stride jump | 5 | 10 | 90–120 s | |

| Plyometrics—drop jump—two feet on the ground and jump (with arm swing) | 5 | 12 | 90–120 s | |

| Counter move—drop jump—landing on one leg and jumping to the left on two legs (with arm swing) | 5 | 12 | 90–120 s | |

| Countermovement—drop jump—landing on two feet and jumping over hurdles | 5 | 10 | 90–120 s |

References

- Chang, P.; Engle, J. Telemedicine and Virtual Interventions in Cancer Rehabilitation: Practical Application, Complications and Future Potentials. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2024, 26, 1600–1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suso-Martí, L.; La Touche, R.; Herranz-Gómez, A.; Angulo-Díaz-Parreño, S.; Paris-Alemany, A.; Cuenca-Martínez, F. Effectiveness of Telerehabilitation in Physical Therapist Practice: An Umbrella and Mapping Review with Meta–Meta-Analysis. Phys. Ther. 2021, 101, pzab075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manchado, C.; Tortosa Martínez, J.; Pueo, B.; Cortell Tormo, J.M.; Vila, H.; Ferragut, C.; Sánchez Sánchez, F.; Busquier, S.; Amat, S.; Chirosa Ríos, L.J. High-Performance Handball Player’s Time-Motion Analysis by Playing Positions. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anicic, Z.; Janicijevic, D.; Knezevic, O.M.; Garcia-Ramos, A.; Petrovic, M.R.; Cabarkapa, D.; Mirkov, D.M. Assessment of Countermovement Jump: What Should We Report? Life 2023, 13, 190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakšić, D.; Maričić, S.; Maksimović, N.; Bianco, A.; Sekulić, D.; Foretić, N.; Drid, P. Effects of Additional Plyometric Training on the Jump Performance of Elite Male Handball Players: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Physiotherapy Research Foundation. Telehealth by Physiotherapists in Australia During the COVID-19 Pandemic; Australian Physiotherapy Association: Camberwell, VIC, Australia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Argent, R.; Daly, A.; Caulfield, B. Patient Involvement with Home-Based Exercise Programs: Can Connected Health Interventions Influence Adherence? JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018, 6, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Collado-Mateo, D.; Lavín-Pérez, A.M.; Peñacoba, C.; Del Coso, J.; Leyton-Román, M.; Luque-Casado, A.; Gasque, P.; Fernández-Del-Olmo, M.Á.; Amado-Alonso, D. Key Factors Associated with Adherence to Physical Exercise in Patients with Chronic Diseases and Older Adults: An Umbrella Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dos’Santos, T.; Evans, D.T.; Read, D.B. Validity of the Hawkin Dynamics Wireless Dual Force Platform System Against a Piezoelectric Laboratory Grade System for Vertical Countermovement Jump Variables. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2024, 38, 1144–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Badby, A.J.; Mundy, P.D.; Comfort, P.; Lake, J.P.; Mcmahon, J.J. The Validity of Hawkin Dynamics Wireless Dual Force Plates for Measuring Countermovement Jump and Drop Jump Variables. Sensors 2023, 23, 4820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fristrup, B.; Krustrup, P.; Kristensen, K.H.; Rasmussen, S.; Aagaard, P. Test–retest reliability of lower limb muscle strength, jump and sprint performance tests in elite female team handball players. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2024, 124, 2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bishop, C.; Jordan, M.; Torres-Ronda, L.; Loturco, I.; Harry, J.; Virgile, A.; Mundy, P.; Turner, A.; Comfort, P. Selecting Metrics That Matter: Comparing the Use of the Countermovement Jump for Performance Profiling, Neuromuscular Fatigue Monitoring, and Injury Rehabilitation Testing. Strength Cond. J. 2023, 45, 545–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkin Dynamics. CMJ Playbook. 2024. Available online: https://www.hawkindynamics.com/cmjplaybook (accessed on 27 September 2024).

- Berton, R.; Lixandrão, M.E.; Pinto E Silva, C.M.; Tricoli, V. Effects of weightlifting exercise, traditional resistance and plyometric training on countermovement jump performance: A meta-analysis. J. Sports Sci. 2018, 36, 2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kraemer, W.J.; Ratamess, N.A. Fundamentals of Resistance Training: Progression and Exercise Prescription. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2004, 36, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammami, M.; Ramirez-Campillo, R.; Gaamouri, N.; Aloui, G.; Shephard, R.J.; Chelly, M.S. Effects of a Combined Upper- and Lower-Limb Plyometric Training Program on High-Intensity Actions in Female U14 Handball Players. Pediatr. Exerc. Sci. 2019, 31, 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazurek, K.; Zmijewski, P.; Makaruk, H.; Mróz, A.; Czajkowska, A.; Witek, K.; Bodasiński, S.; Lipińska, P. Effects of Short-Term Plyometric Training on Physical Performance in Male Handball Players. J. Hum. Kinet. 2018, 63, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sladeckova, M.; Kocica, J.; Vlckova, E.; Dosbaba, F.; Pepera, G.; Su, J.J.; Batalik, L. Exercise-based telerehabilitation for patients with multiple sclerosis using physical activity: A systematic review. J. Rehabil. Med. 2024, 56, jrm40641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Özden, F.; Özkeskin, M.; Tümtürk, İ.; Yalın Kılınç, C. The effect of exercise and education combination via telerehabilitation in patients with chronic neck pain: A randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Med. Inform. 2023, 180, 105281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntoumanis, N.; Moller, A.C. Self-determination theory informed research for promoting physical activity: Contributions, debates, and future directions. Psychol. Sport. Exerc. 2025, 80, 102879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kortum, P.; Acemyan, C.Z.; Oswald, F.L. Is It Time to Go Positive? Assessing the Positively Worded System Usability Scale (SUS). Hum. Factors 2020, 63, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Control Group | Intervention Group | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics of the Players | n = 14 Mean ± SD | n = 14 Mean ± SD | |

| Age (years) | 22.8 ± 3.2 | 23.71 ± 4.51 | 0.56 |

| Height (cm) | 1.80 ± 0.06 | 1.79 ± 0.04 | 0.63 |

| Weight (kg) | 82.6 ± 16.1 | 78.6 ± 9.5 | 0.12 |

| BMI | 26.47 ± 3.91 | 24.37 ± 2.27 | 0.99 |

| Years playing | 12.5 ± 2.8 | 14.2 ± 6.2 | 0.36 |

| Variable | Control PRE | Intervention PRE | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jump Height (m) | 0.35 ± 0.05 | 0.36 ± 0.06 | 0.970 |

| Peak Propulsive Force (N) * | 2215.4 ± 429.9 | 1935.9 ± 281.6 | 0.777 |

| Flight Time (s) * | 0.53 ± 0.04 | 0.53 ± 0.05 | 0.991 |

| Propulsive Impulse (N·s) | 444.9 ± 101.7 | 393.6 ± 51.1 | 0.129 |

| Time to Takeoff (s) * | 0.75 ± 0.13 | 0.76 ±0.10 | 0.448 |

| mRSI (Reactive Strength Index) | 0.48 ± 0.10 | 0.48 ± 0.11 | 0.599 |

| Time to Stabilization (s) | 725.5 ± 134.3 | 768.7 ± 180.4 | 0.511 |

| Peak Propulsive Power (W) | 4548.8 ± 737.7 | 4090.8 ± 697.7 | 0.542 |

| Stiffness (N/m/kg) | −7408 ± 2132 | −6331 ± 1295 | 0.130 |

| Braking RFD (N/s) * | 8628 ± 4414 | 7436 ± 3080 | 0.701 |

| Peak Velocity (m/s) | 2.74 ± 0.19 | 2.76 ± 0.19 | 0.953 |

| Variable | Control PRE | Control POST | p | d Cohen | Intervention PRE | Intervention POST | p | d Cohen |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jump Height (m) | 0.35 ± 0.05 | 0.37 ± 0.05 | 0.008 | 0.02 | 0.36 ± 0.05 | 0.38 ± 0.06 | 0.037 | 0.03 |

| Peak Propulsive Force (N) * | 2215.4± 429.9 | 2199.6 ± 374.6 | 0.722 | 156.49 | 1935.2 ± 281.6 | 1977.7 ± 277.2 | 0.316 | 120.32 |

| Flight Time (s) * | 0.53 ± 0.04 | 0.55 ± 0.04 | 0.011 | 0.02 | 0.53 ± 0.04 | 0.56 ± 0.04 | 0.016 | 0.02 |

| Propulsive Impulse (N·s) | 444.9 ± 101.7 | 448.5± 95.5 | 0.577 | 22.49 | 393.6 ± 51.1 | 398.4 ± 42.6 | 0.575 | 25.43 |

| Time to Takeoff (s) | 0.75 ± 0.13 | 0.76 ± 0.14 | 0.674 | 0.08 | 0.76 ± 0.10 | 0.74 ± 0.09 | 0.543 | 0.11 |

| mRSI (Reactive Strength Index) | 0.48 ± 0.10 | 0.50 ± 0.11 | 0.176 | 0.04 | 0.48 ± 0.12 | 0.53 ± 0.12 | 0.094 | 0.07 |

| Time to Stabilization (s) | 725.5± 134.3 | 717.2 ± 128.6 | 0.914 | 160.55 | 768.7 ± 180.4 | 747.4 ± 227.7 | 0.894 | 201.97 |

| Peak Propulsive Power (W) * | 4548.8 ± 737.7 | 4646.1 ± 615.9 | 0.136 | 219.36 | 4090.8 ± 697.7 | 4277.3 ± 747.7 | 0.189 | 341.05 |

| Stiffness (N/m/kg) | −7408 ± 2132 | −7306 ± 2614 | 0.809 | 1496.11 | −6331 ± 1295 | −6351 ± 1151 | 0.986 | 1103.96 |

| Braking RFD (N/s) * | 8628 ± 4414 | 8890 ± 4618 | 0.713 | 2508.62 | 7436 ± 3080 | 8151 ± 2885 | 0.186 | 1774.36 |

| Peak Velocity (m/s) | 2.74 ± 0.19 | 2.80 ± 0.18 | 0.004 | 0.06 | 2.76 ± 0.19 | 2.85 ± 0.22 | 0.023 | 0.09 |

| Variable | Control POST | Intervención POST | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jump Height (m) | 0.37 ± 0.05 | 0.38 ± 0.06 | 0.521 |

| Peak Propulsive Force (N) * | 2199.6 ± 374.6 | 1977.7 ± 277.2 | 0.277 |

| Flight Time (s) * | 0.55 ± 0.04 | 0.56 ± 0.04 | 0.586 |

| Propulsive Impulse (N·s) | 448.5 ± 95.5 | 398.4 ± 42.6 | 0.109 |

| Time to Takeoff (s) * | 0.76 ± 0.14 | 0.74± 0.09 | 0.870 |

| mRSI (Reactive Strength Index) | 0.50 ± 0.11 | 0.52 ± 0.12 | 0.565 |

| Time to Stabilization (s) | 717.2 ± 128.6 | 747.4 ± 227.7 | 0.688 |

| Peak Propulsive Power (W) | 4646 ± 615 | 4277 ± 747 | 0.190 |

| Stiffness (N/m/kg) | −7306 ± 2614 | −6351 ± 1151 | 0.257 |

| Braking RFD (N/s) * | 8890 ± 4618 | 8151 ± 2 885 | 0.639 |

| Peak Velocity (m/s) | 2.80 ± 0.18 | 2.85 ± 0.22 | 0.526 |

| Variable | Control | Intervention | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attendance (%) | 46.8± 32.31 | 41.9 ± 31.81 | 0.68 |

| Compliance (%) | 41.29 ± 31.07 | 44.25 ± 30.12 | 0.8 |

| Psychosocial (%) | 78.4 ± 6.85 | 78.4 ± 6.85 | 1 |

| Total adherence (%) | 48.98 ± 25.14 | 53.13 ± 24.83 | 0.74 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kwapisz Dos Santos, A.; García Catalán, A.; Rodríguez-Fernández, Á.L.; García-Muro San José, F. Effectiveness of a Home-Based Telehealth Exercise Program Using the Physitrack® App on Adherence and Vertical Jump Performance in Handball Players: A Randomized, Controlled Pilot Study. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13108. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413108

Kwapisz Dos Santos A, García Catalán A, Rodríguez-Fernández ÁL, García-Muro San José F. Effectiveness of a Home-Based Telehealth Exercise Program Using the Physitrack® App on Adherence and Vertical Jump Performance in Handball Players: A Randomized, Controlled Pilot Study. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13108. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413108

Chicago/Turabian StyleKwapisz Dos Santos, Andréa, Adrián García Catalán, Ángel Luís Rodríguez-Fernández, and Francisco García-Muro San José. 2025. "Effectiveness of a Home-Based Telehealth Exercise Program Using the Physitrack® App on Adherence and Vertical Jump Performance in Handball Players: A Randomized, Controlled Pilot Study" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13108. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413108

APA StyleKwapisz Dos Santos, A., García Catalán, A., Rodríguez-Fernández, Á. L., & García-Muro San José, F. (2025). Effectiveness of a Home-Based Telehealth Exercise Program Using the Physitrack® App on Adherence and Vertical Jump Performance in Handball Players: A Randomized, Controlled Pilot Study. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13108. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413108