1. Introduction

Three-dimensional (3D) geological models integrate structural geometry with physical properties to support the visualization and analysis of subsurface data [

1]. They underpin initiatives in Digital Earth [

2,

3], Smart Cities [

4], and Digital Twins [

4], and are widely applied to regional resource exploration [

5], reservoir characterization [

6,

7], and tunnel engineering [

8,

9]. Recent voxel-based geological data models and digital-twin frameworks [

10,

11] further highlight the importance of unified volumetric representations and efficient voxel storage for large-scale engineering and Earth system applications. In practice, two complementary categories are often distinguished: geological structural models, which express spatial relationships among strata, faults, and rock masses, and geological property models, which consolidate multi-source data into discretized units with attributes such as porosity and mineral composition [

12]. Among various representations, block-based models have become mainstream for large-scale 3D geological modeling due to their spatial adaptability and computational efficiency [

13]. These models partition the subsurface into 3D cells, each storing geological attributes (e.g., lithology, material properties), typically arranged as structured grids (axis-aligned or stratigraphic-aligned). Such explicit storage enables direct queries and computations (e.g., resource estimation) on the block grid. For instance, Han et al. (2022) [

14] developed a three-dimensional engineering geological model for the Xiong’an New Area to support urban planning, and Radwan et al. (2022) [

15] employed reservoir modeling to optimize oilfield strategies. However, geological properties vary across scales [

16,

17], and real-world datasets exhibit uneven spatial density, heterogeneous resolution, and hierarchical block representations, all of which complicate model organization and indexing.

Multiscale partitioning provides a path to reconcile macro-scale navigation with micro-scale analysis. However, effective indexing and management of multiscale blocks are still challenging for three main reasons. First, cross-scale variation is complex, and traditional methods struggle to maintain spatial structure and consistency. This leads to integration issues, information loss, and inefficiency. Second, spatial density is uneven. Uniform partitioning wastes storage in sparse regions and fails to aggregate efficiently in dense regions, which increases access path length. Third, query cost grows with scale dependence because geological features change across scales and require conversion and synchronization steps. Several hierarchical frameworks partially mitigate these issues. Tree-structured indexes and spatial grid coding have been explored [

10,

18]. Octrees support recursive refinement [

19,

20] but waste storage in sparse datasets due to empty nodes [

21]. VDB variants efficiently manage sparsity [

22,

23,

24], but incur storage overhead in dense regions. Hybrid indexing, such as the TQ-tree-based HiIndex [

25], improves visualization but still suffers from high cross-scale mapping cost [

26]. Beyond classical octrees and VDB, recent work on hierarchical voxel structures [

27] systematically analyzes efficient voxel layouts and access patterns, which further underscores the need for integrated multiscale data models. Space-filling curves transform multi-dimensional data into one-dimensional keys while preserving spatial locality. Among them, Hilbert curves generally provide stronger spatial clustering than Z-order (Morton) codes [

28]. From a broader database perspective, WH-MSDM can be viewed as a specialized multidimensional index [

29] that leverages W-Hilbert codes to balance locality, storage cost, and query performance in a geological setting. Nevertheless, classical Hilbert curves assume uniform grids and do not encode scale. Consequently, cross-scale clustering is limited, and recursive child-code computation has

complexity [

30], which restricts real-time performance in multi-resolution settings.

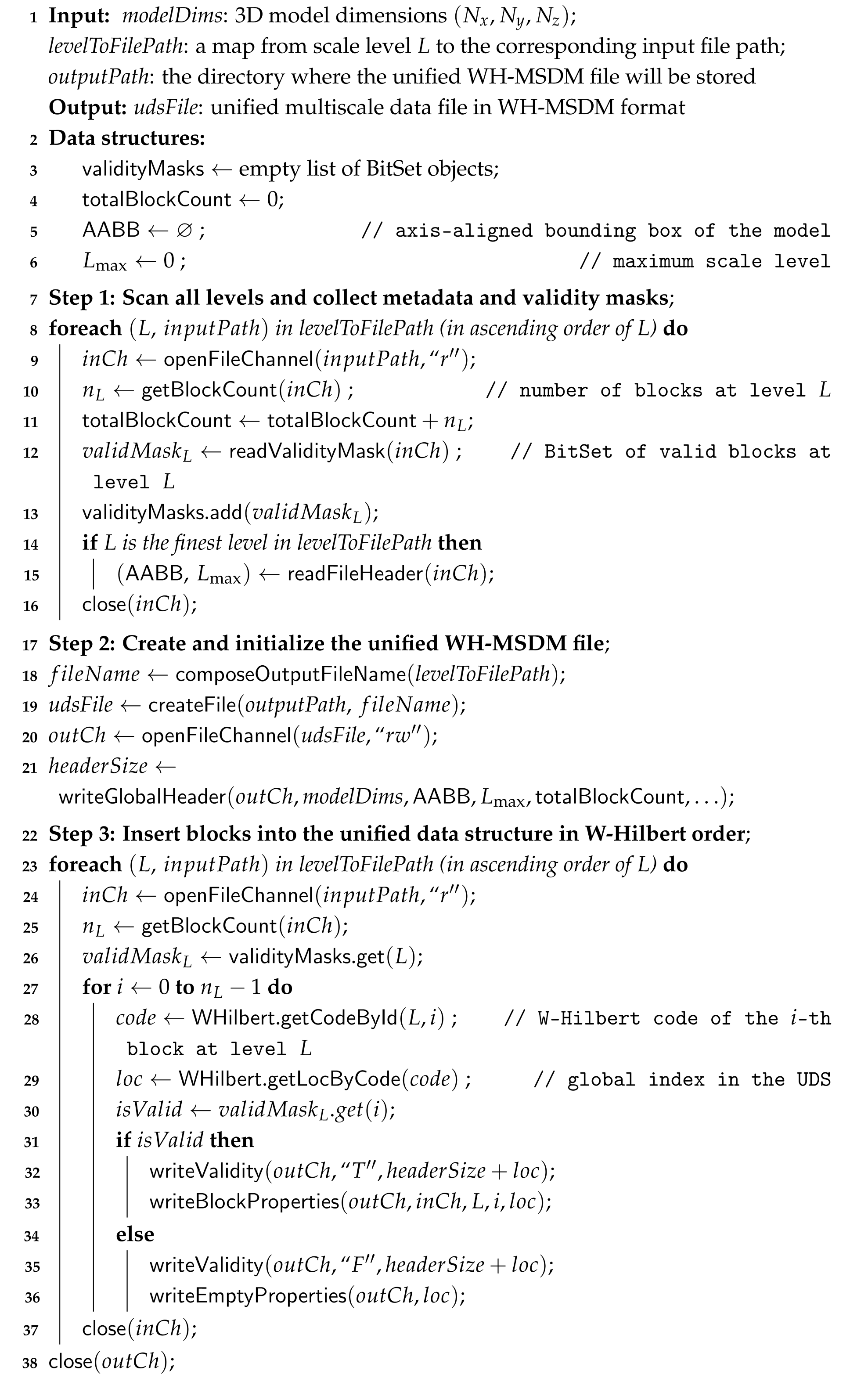

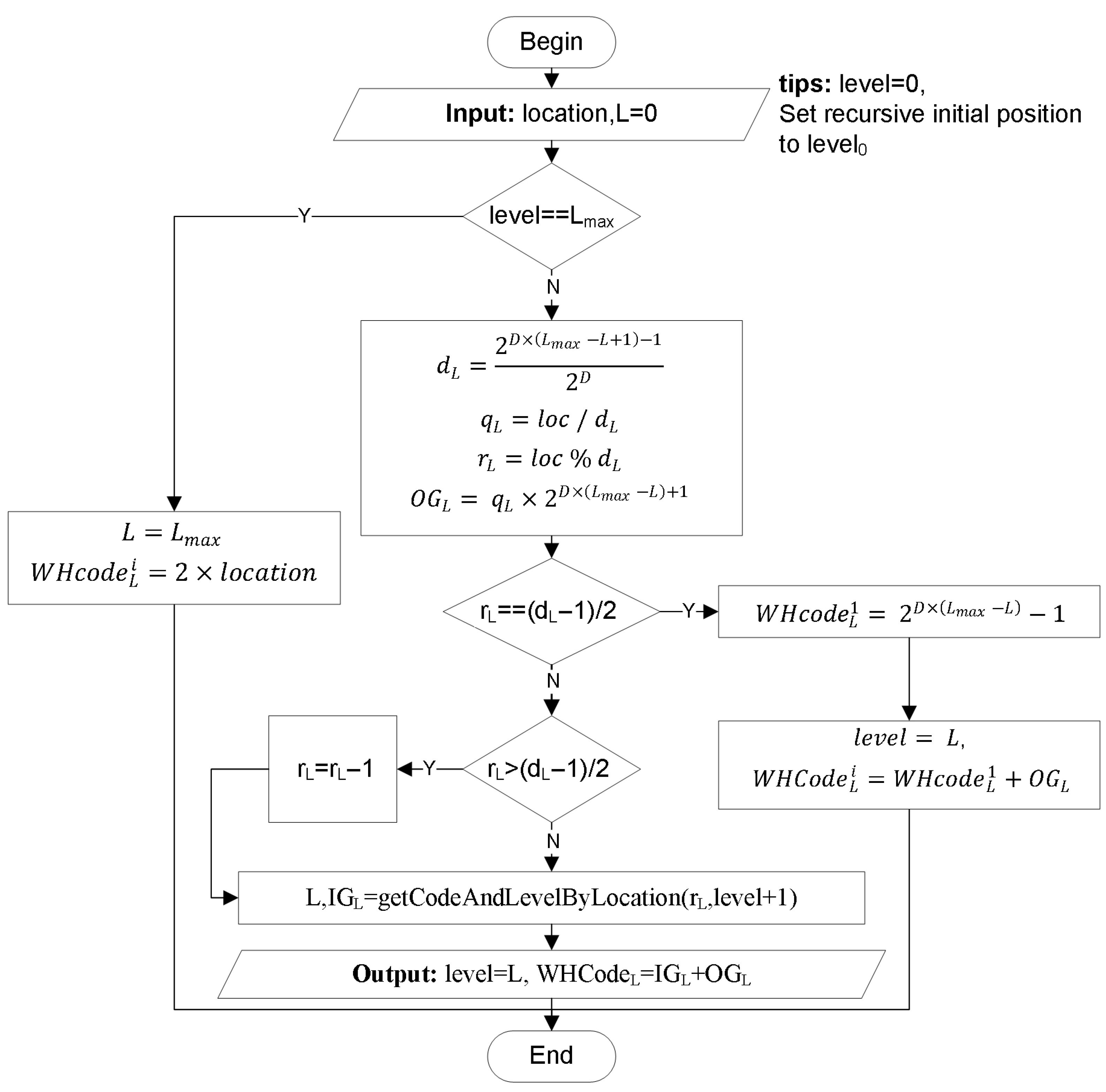

To alleviate these limitations, Lei et al. (2023) [

31] proposed the W-shaped Hilbert curve. The method combines fractal partitioning with optimized child-code computation and maps multi-level n-dimensional blocks into an inverted

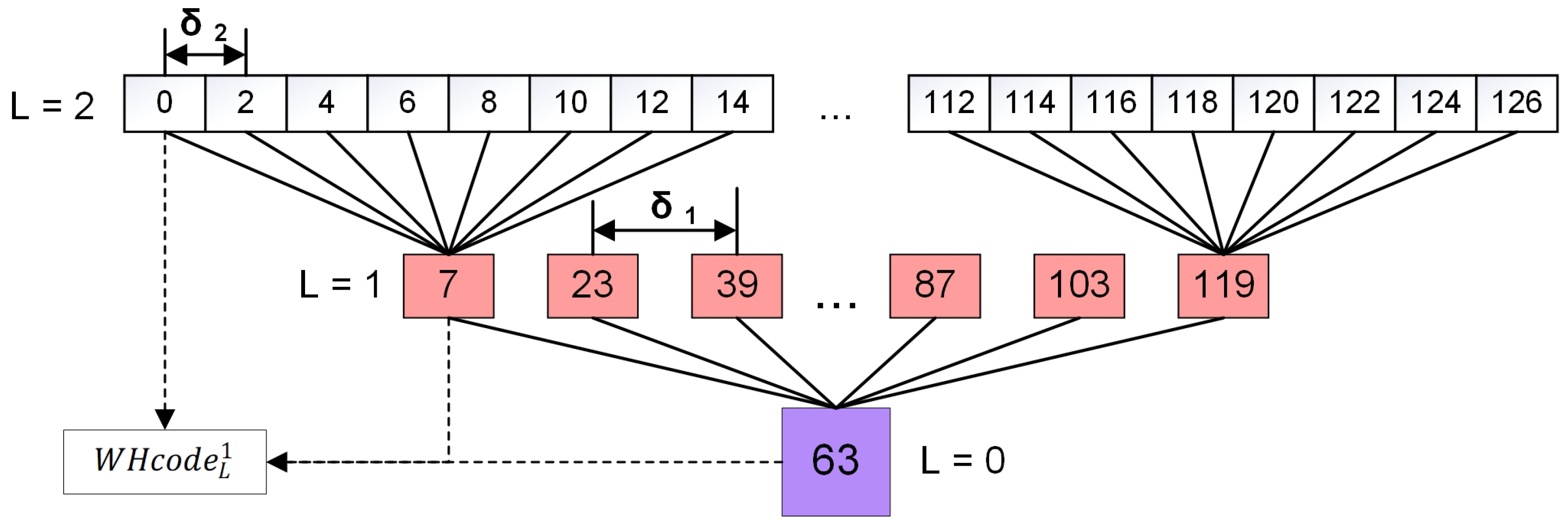

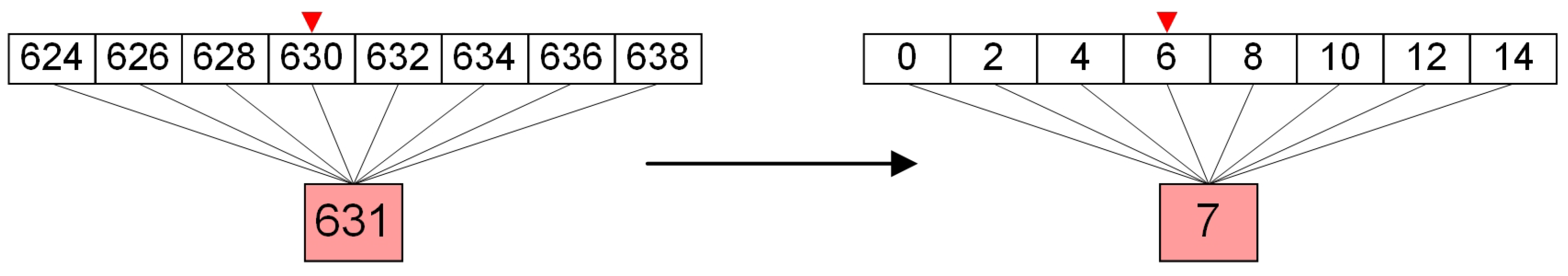

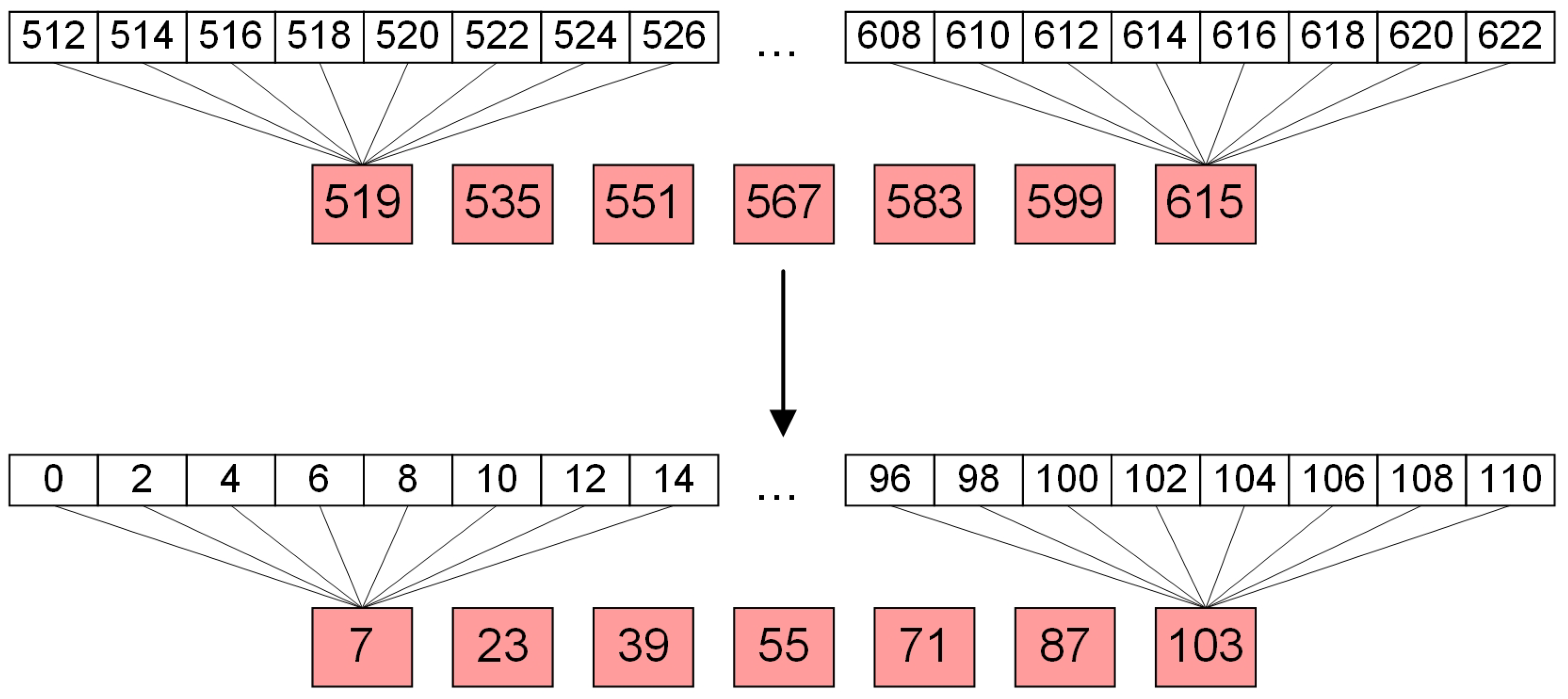

tree as illustrated in

Figure 1. The hierarchical code explicitly embeds scale information and preserves spatial locality. This design enables efficient multiscale operations using bitwise arithmetic. Previous work on the W-Hilbert curve has already provided a systematic comparison against classical Hilbert and Morton curves. Lei et al. (2023) [

31] report quantitative locality metrics, visual analyses of clustering patterns, and query benchmarks, and show that W-Hilbert achieves better multiscale spatial clustering and more efficient child-code computation than the classical curves. Building on these results, the present work does not re-evaluate W-Hilbert itself; instead, we treat W-Hilbert as a validated multiscale indexing primitive and focus on designing a unified data structure and bidirectional mapping model that connect these codes to storage layout and application-level queries on 3D geological blocks. Two properties govern the encoding. The initial encoding sets a level-dependent base code given by Equation (

1):

which

ensures distinct base values across levels, where

D denotes the spatial dimensionality and

is the maximum refinement depth. The encoding interval then fixes the intra-level spacing, as given by Equation (

2):

which isolates scale levels while allowing for expansion within the same level. In Equation (

2),

is the fixed spacing between consecutive W-Hilbert codes at level

L, so that all codes at the same level form an evenly spaced sequence. Given block coordinates

, the standard Hilbert code

at the target level

L is first computed. The W-Hilbert code is then obtained as shown in Equation (

3),

is the standard Hilbert code at level

L,

is the resulting W-Hilbert code, and the two terms respectively encode the intra-level ordering and the level-dependent base code.

In this expression, the first term preserves the spatial ordering of the Hilbert code within level L the second term anchors the code to the scale hierarchy.

Decoding proceeds in two steps. The scale level

L is inferred from the trailing bits of the binary form, which can be written as shown in Equation (

4):

so that counting the consecutive trailing 1s yields

Here the “Trailing 1’s count” denotes the number of consecutive 1 bits at the end of the binary representation of

, which uniquely determines the scale level L according to the pattern in Equation (

4). The intra-level Hilbert code is then recovered by

The intra-level Hilbert code is then recovered by (

6), and standard Hilbert decoding maps

back to spatial coordinates [

30]. Taken together, Equations (

4)–(

6) show that level information and the standard Hilbert index can be recovered from a single W-Hilbert code using simple arithmetic and bit operations. In summary, W-Hilbert improves cross-scale spatial locality and the efficiency of encoding and decoding. Given the base and interval in Equations (

1) and (

2) and the decoding in Equations (

4)–(

6), W-Hilbert yields a hierarchical code space with explicit scale markers and strong spatial locality, which we adopt as the backbone for coding multi-resolution blocks. What remains unmet in practice is the need for an integrated model to bind these codes to storage for attribute-rich blocks and to provide spatial, attributive, hybrid, and cross-scale query operators with predictable cost, thereby connecting W-Hilbert’s cross-scale locality with end-to-end storage, indexing, and querying on hierarchical block models.

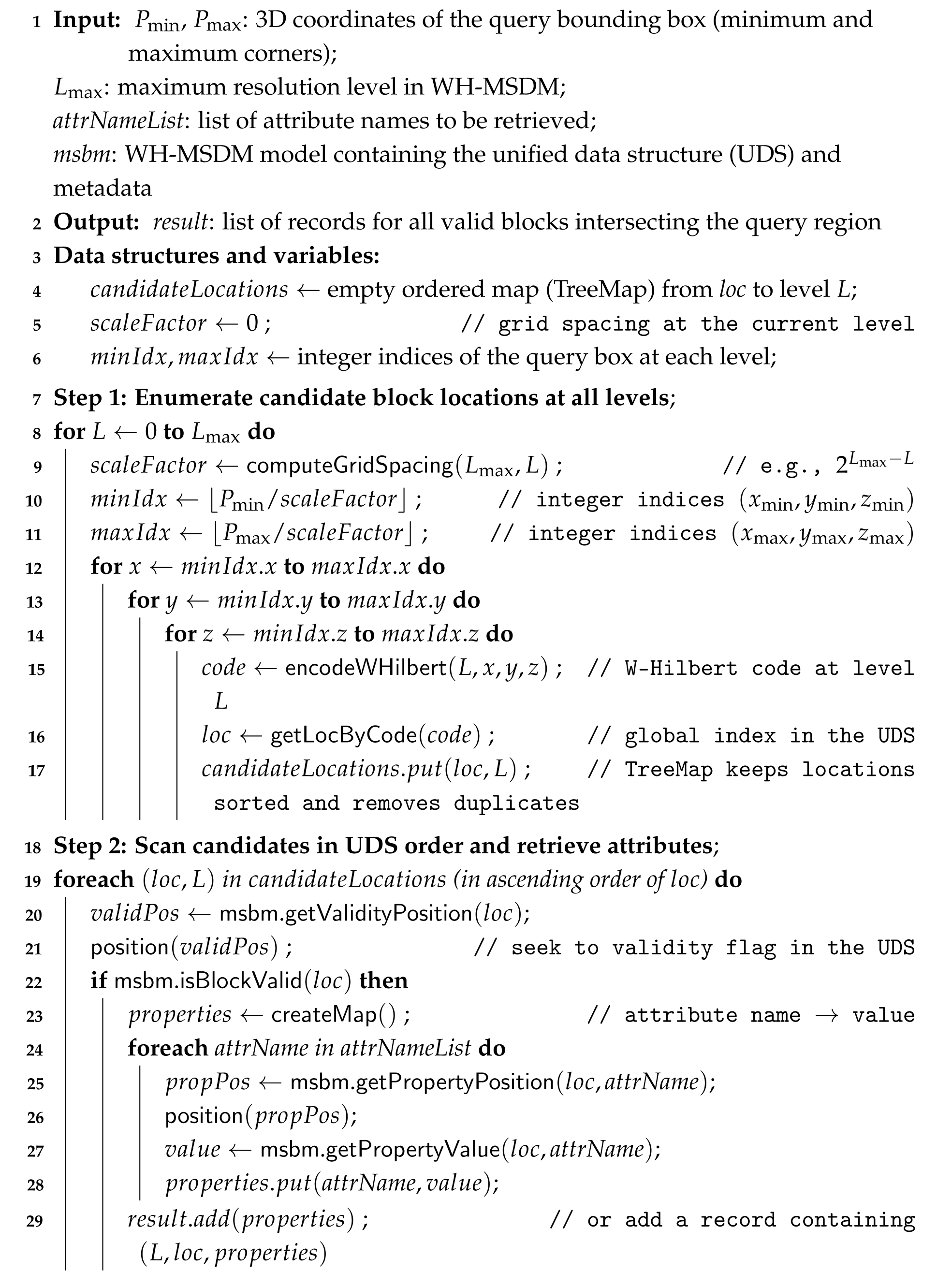

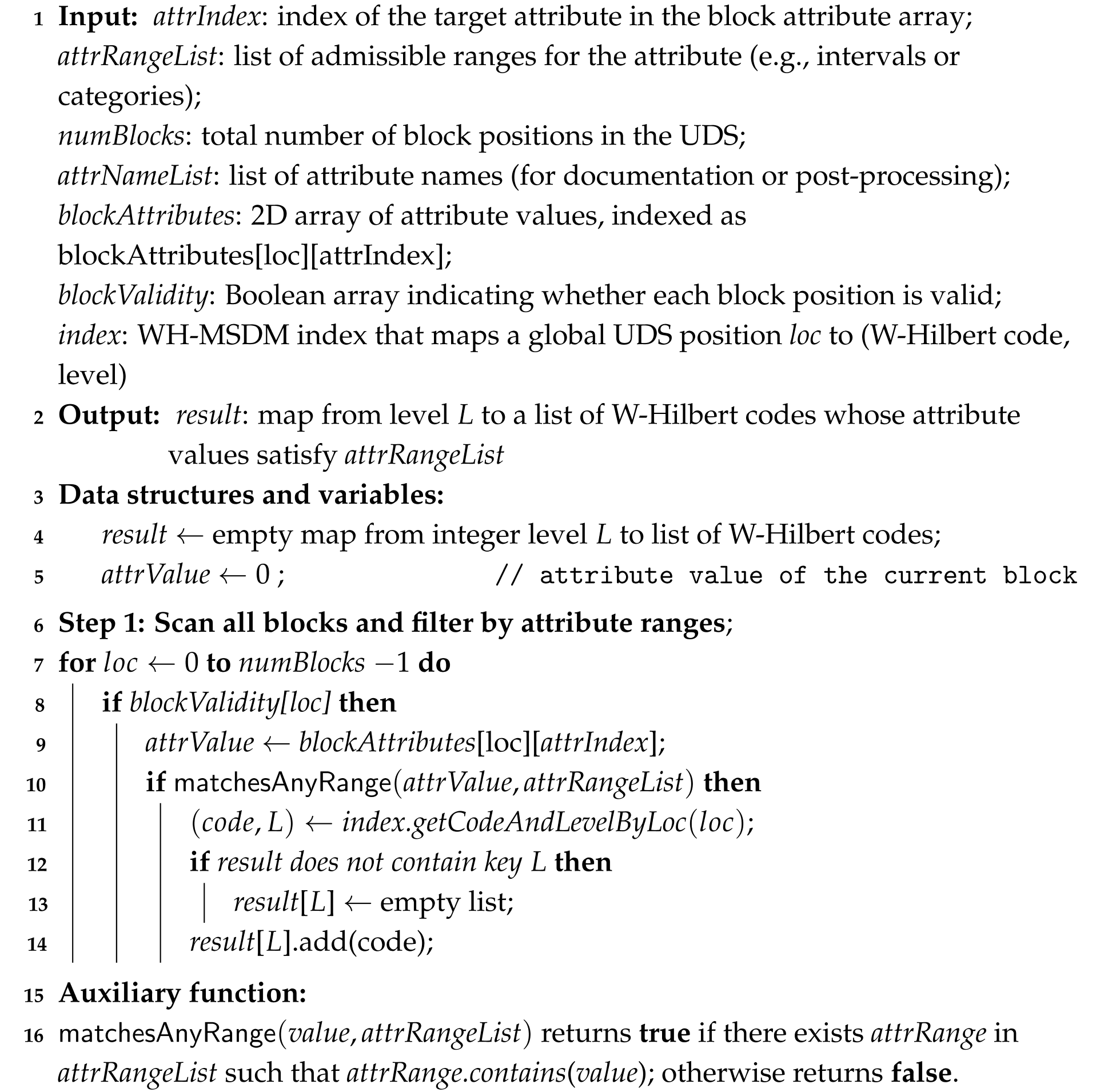

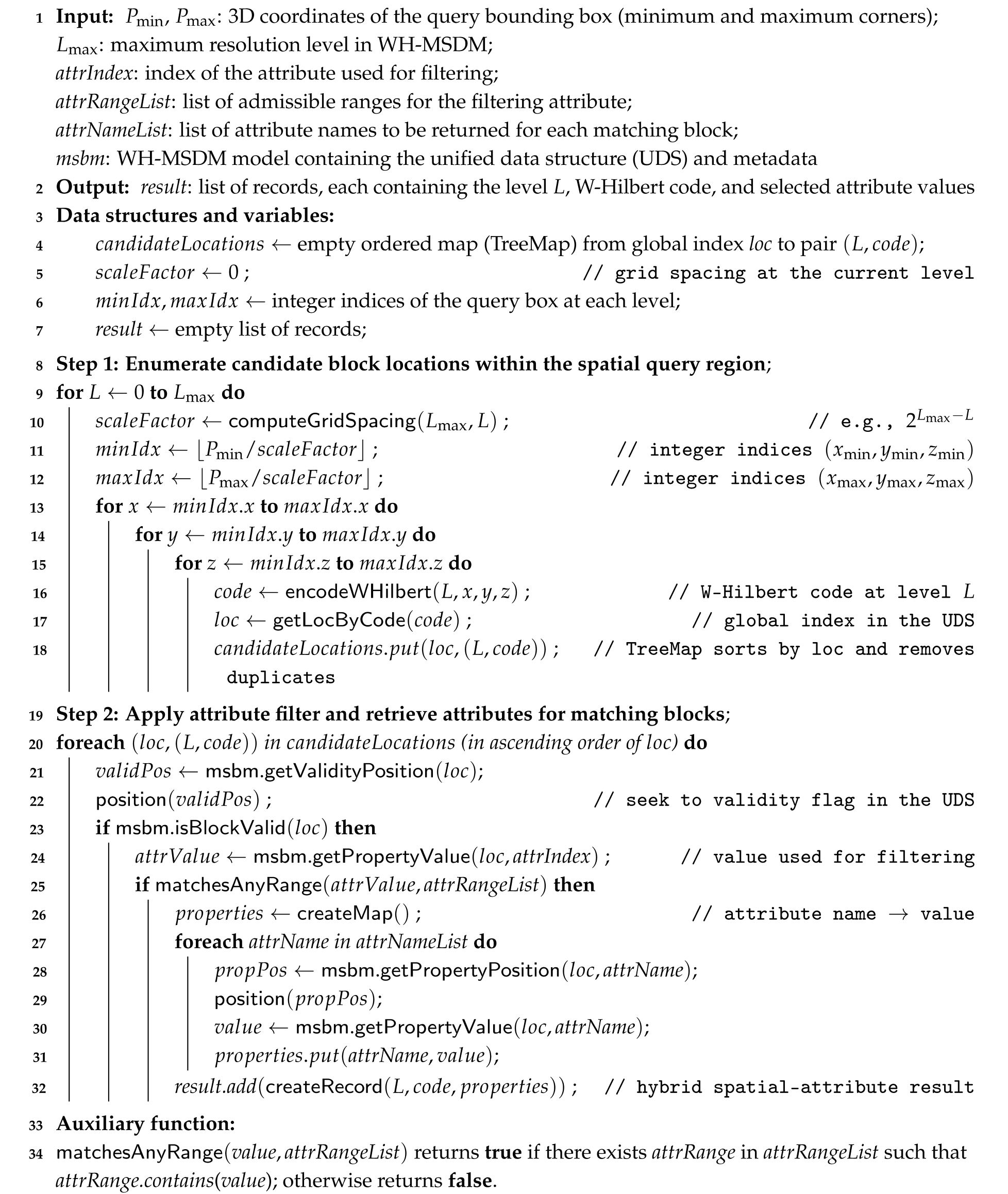

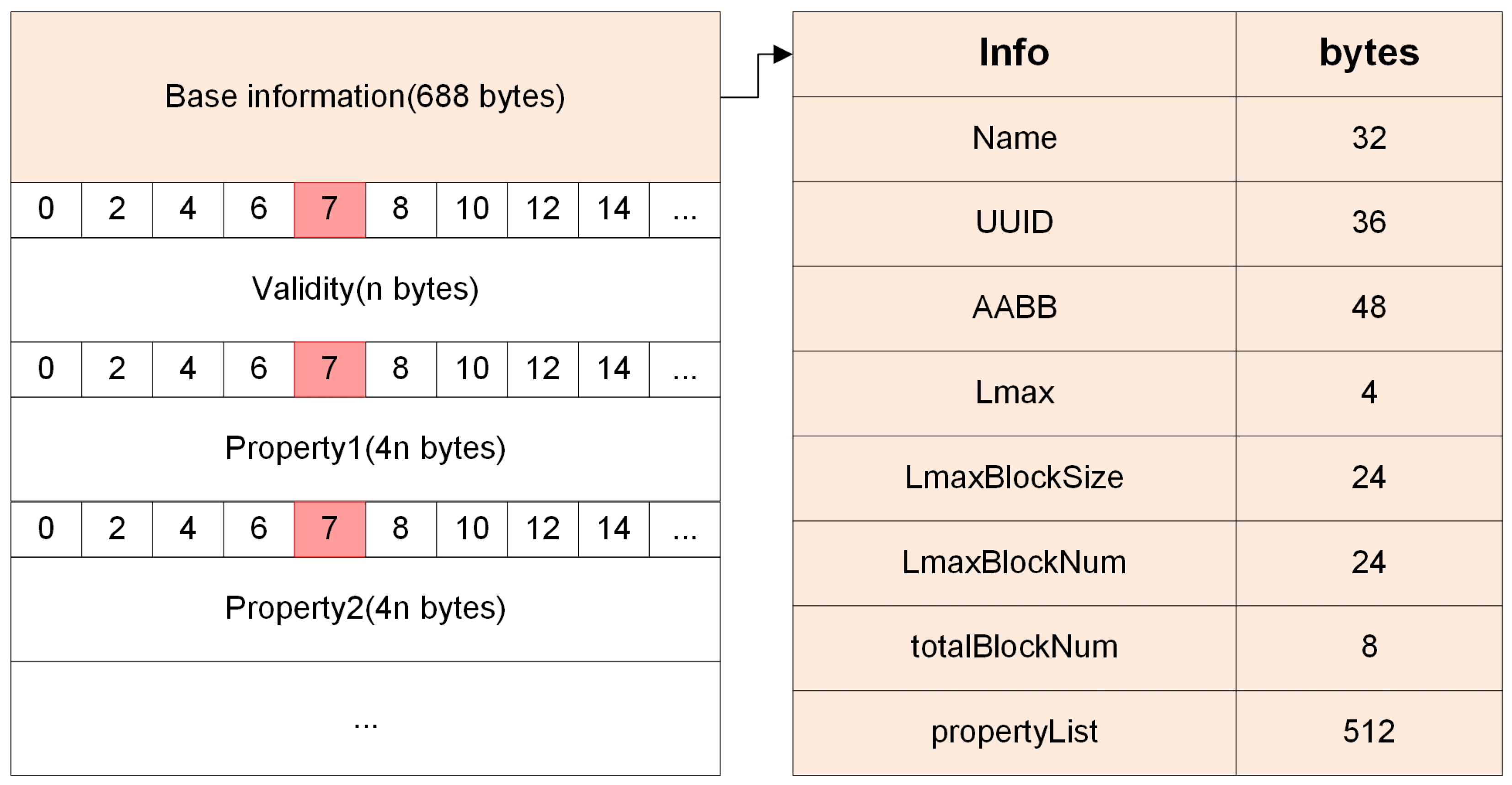

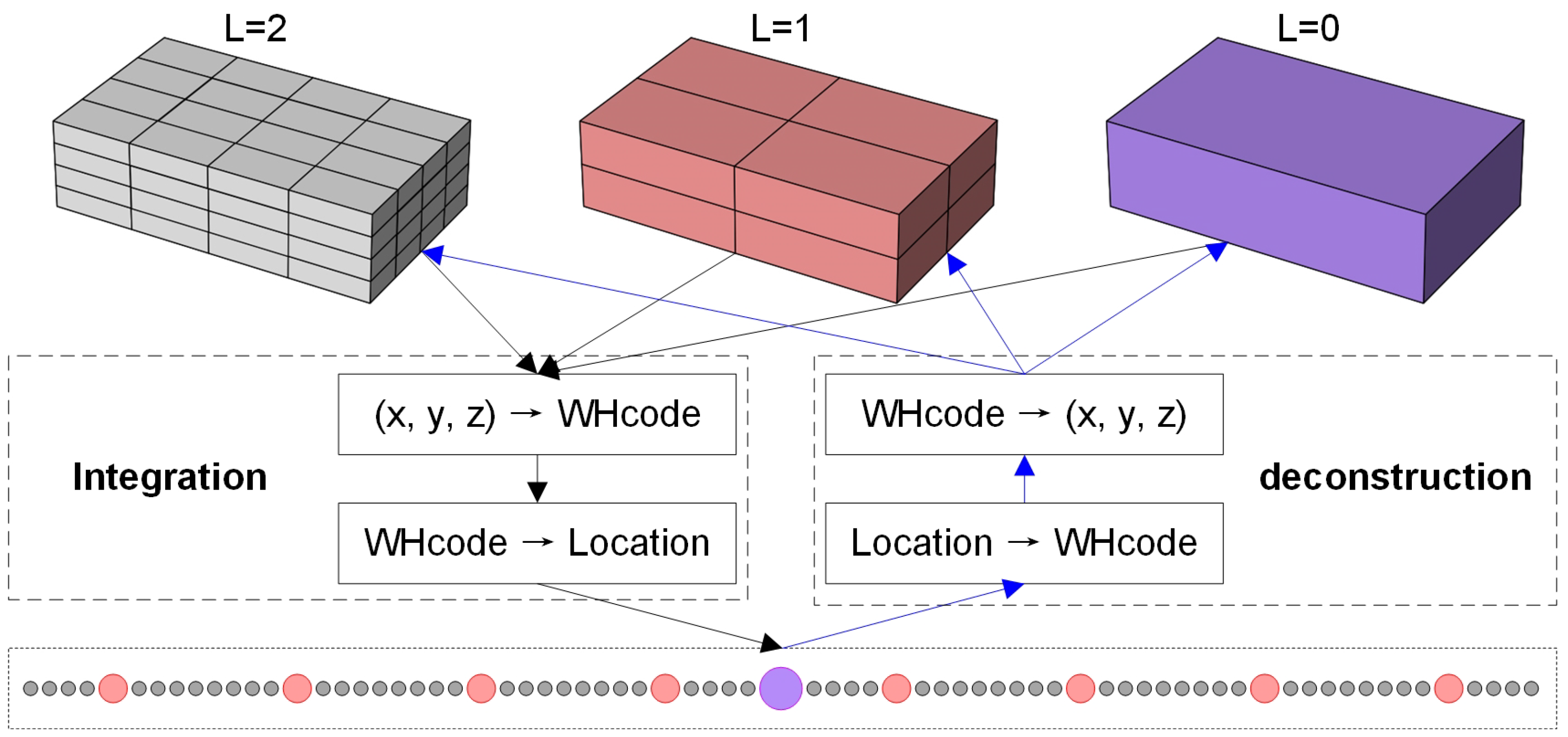

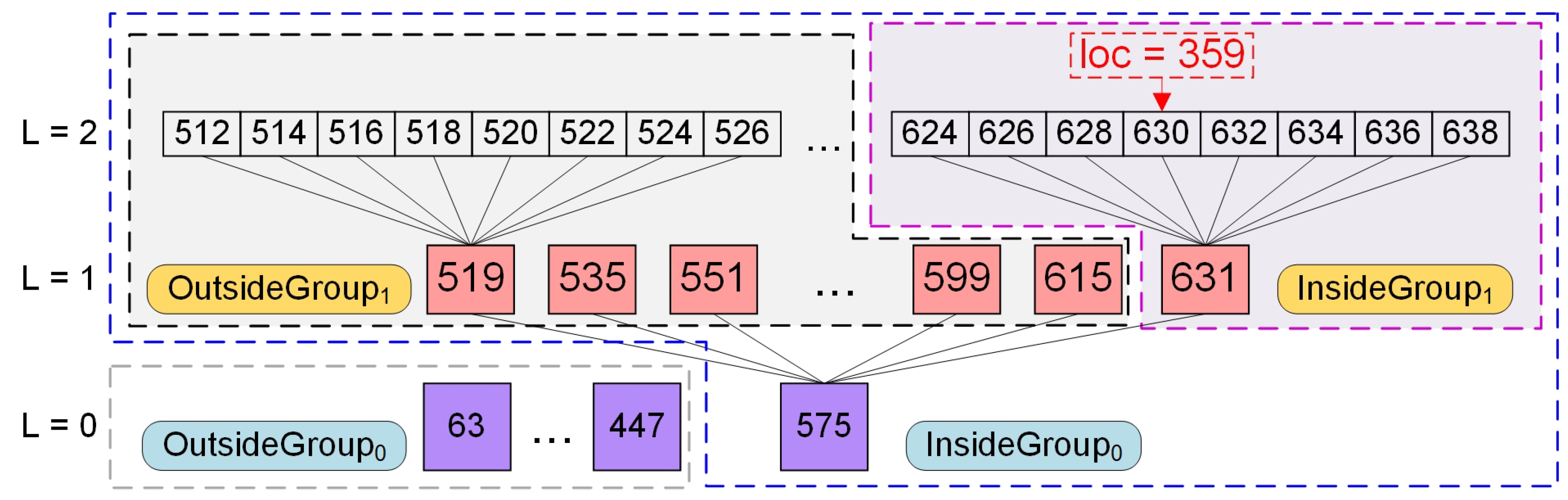

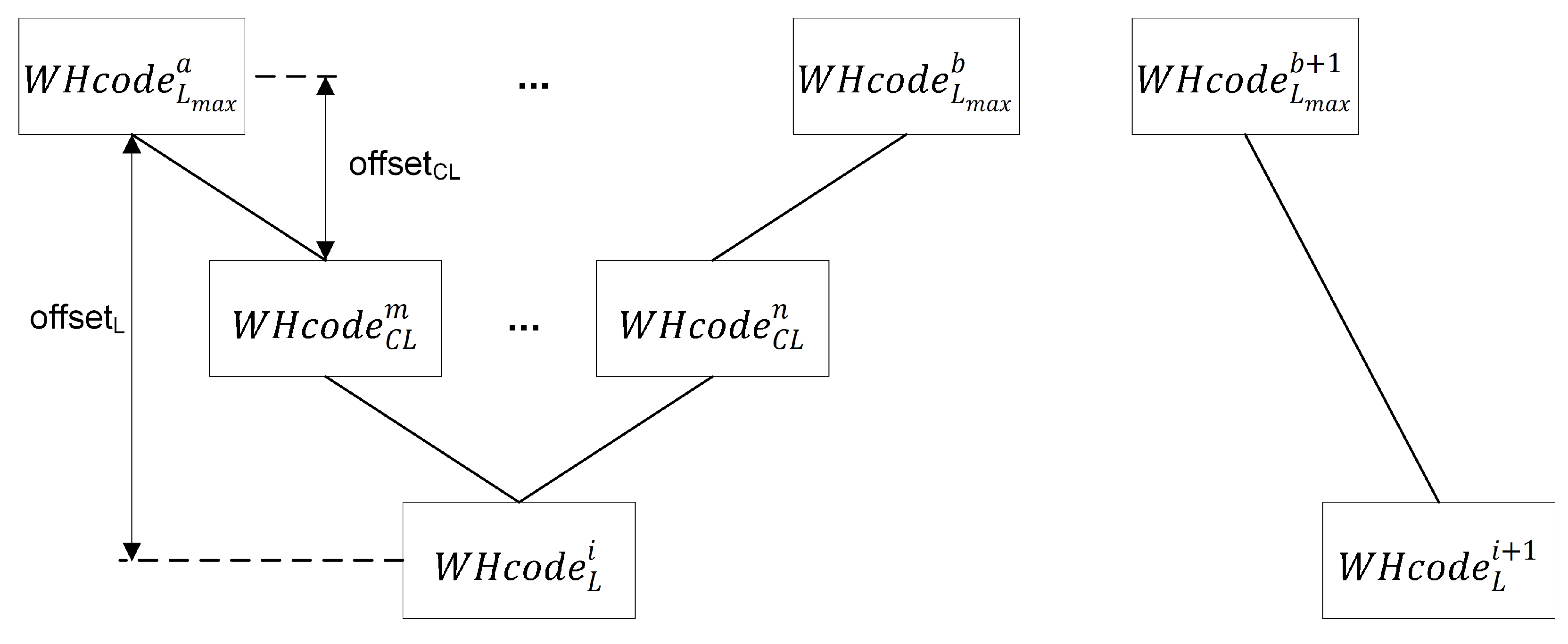

To fill this gap, we propose WH-MSDM, a comprehensive multiscale data model that elevates W-Hilbert encoding into a complete data management solution. WH-MSDM introduces a unified data structure (UDS) that assigns contiguous W-Hilbert codes to blocks at every resolution, enabling single-pass retrieval without redundant storage, and a bidirectional mapping model (BMM) that binds 3D block coordinates to these codes for unified hierarchical indexing. Building on this foundation, we design scalable query algorithms, including spatial, attributive, hybrid, and cross-scale queries, which exploit the WH-MSDM framework to retrieve multi-resolution block data flexibly and precisely. This framework provides an integrated solution that unifies storage, indexing, and querying for multiscale 3D geological data, which provides a data-model foundation for Digital Earth-oriented multiscale 3D geological analysis.

4. Conclusions

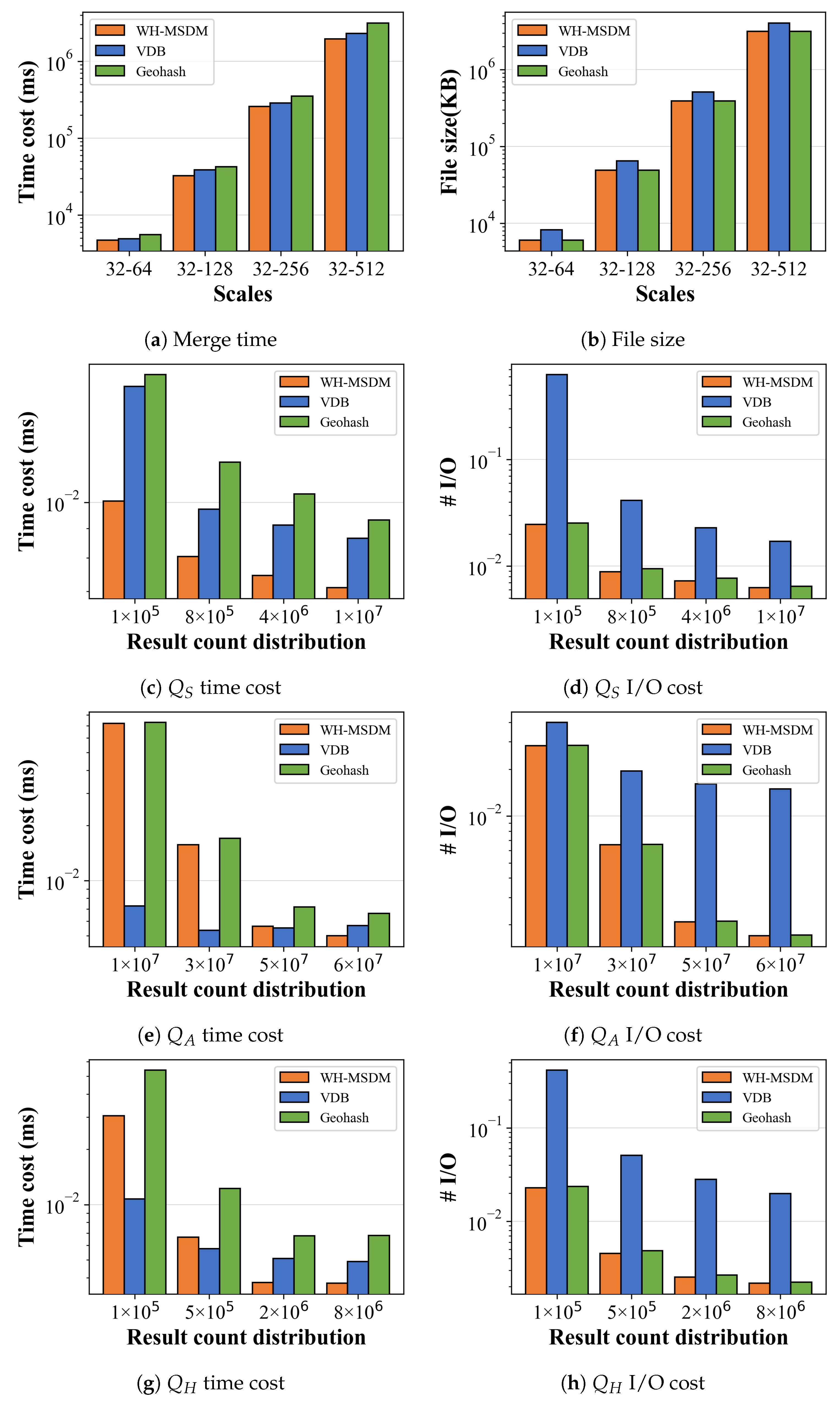

This paper proposed WH-MSDM to address the management of geological data with uneven spatial distribution, multidimensional attributes, and multiscale structure. By combining a unified data structure (UDS), a bidirectional mapping model (BMM), and specialized query algorithms, WH-MSDM achieves more efficient and scalable data organization and querying than VDB, Geohash, and Octree. The UDS allows WH-MSDM to organize blocks from all resolutions within a single global framework, thereby accommodating highly non-uniform spatial distributions without duplicating data. In terms of data organization, WH-MSDM reduces organization time by 10.1% compared to VDB and 25.9% compared to Geohash while saving 32.0% of storage space relative to VDB.

On the query side, WH-MSDM provides dedicated procedures for spatial, attribute, hybrid, and cross-scale queries, which together support flexible access to multiscale and multidimensional geological attributes. Benchmark experiments consistently show lower query times and I/O costs compared to the baseline. For spatial queries, WH-MSDM is 24.9% faster than VDB and 32.1% faster than Geohash, while substantially reducing I/O overhead. As data size, attribute count, and maximum scale level increase, WH-MSDM maintains stable performance, whereas VDB and Octree exhibit clear degradation. By exploiting the BMM for efficient cross-scale mapping, the framework quickly and accurately retrieves parent and child blocks, thereby supporting seamless integration across levels of detail in multiscale analysis. The main contributions of this work can be summarized as follows: (1) a W-Hilbert-based unified data structure that assigns contiguous codes to blocks at all resolutions, enabling single-pass retrieval without redundant storage. (2) A bidirectional mapping model that dynamically links three-dimensional geological block coordinates to multiscale storage positions, supporting unified hierarchical indexing and efficient joint querying of geometric structure and multiscale attributes. (3) A suite of query algorithms for spatial, attribute, hybrid, and cross-scale access that improves the flexibility, precision, and efficiency of block data storage and retrieval in complex geological settings.

WH-MSDM is well-suited to practical multiscale applications such as regional geological surveys and mineral exploration, where reducing the time and computational resources required for data organization and querying directly improves analytical efficiency and supports resource management and environmental assessment. At the same time, WH-MSDM is complementary to recent multiscale geospatial grid management frameworks [

32], which focus on grid design and indexing strategies at global scales. Despite the above advantages, WH-MSDM has several limitations and applicability conditions that should be noted. First, the current experiments are conducted on a real 1:250,000 3D geological model from southwestern Guizhou Province, but the available attribute set is still relatively modest and the number of tested resolution levels is limited. In real industrial deployments, such as large-scale mining or reservoir models, the attribute dimensionality and the range of scales may be substantially higher, which could increase index size and cache pressure. Second, the method assumes that the valid-block ratio is not extremely low. When the proportion of valid blocks becomes very small, storing identifiers for invalid blocks to maintain global spatial coherence can introduce additional overhead, and sparse representations such as VDB may become more favorable in terms of memory. Third, WH-MSDM is currently designed for grids that are locally regular in three dimensions. Highly anisotropic grids or strongly irregular stratigraphic geometries may require a more sophisticated coupling between the geological modeling step and the W-Hilbert-based indexing to avoid inefficiencies. Finally, although our implementation is CPU-based and demonstrates clear performance benefits, mapping the bidirectional mapping model and query operators efficiently to GPUs or other parallel architectures requires careful design of data layouts and memory access patterns, which we leave as future work.