Effect of Drying Methods on the Physical and Surface Properties of Blueberry and Strawberry Fruit Powders: A Review

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Fruit Berries Composition

2.1. Strawberries

2.2. Blueberry

3. Drying Methods to Produce Fruit Powders

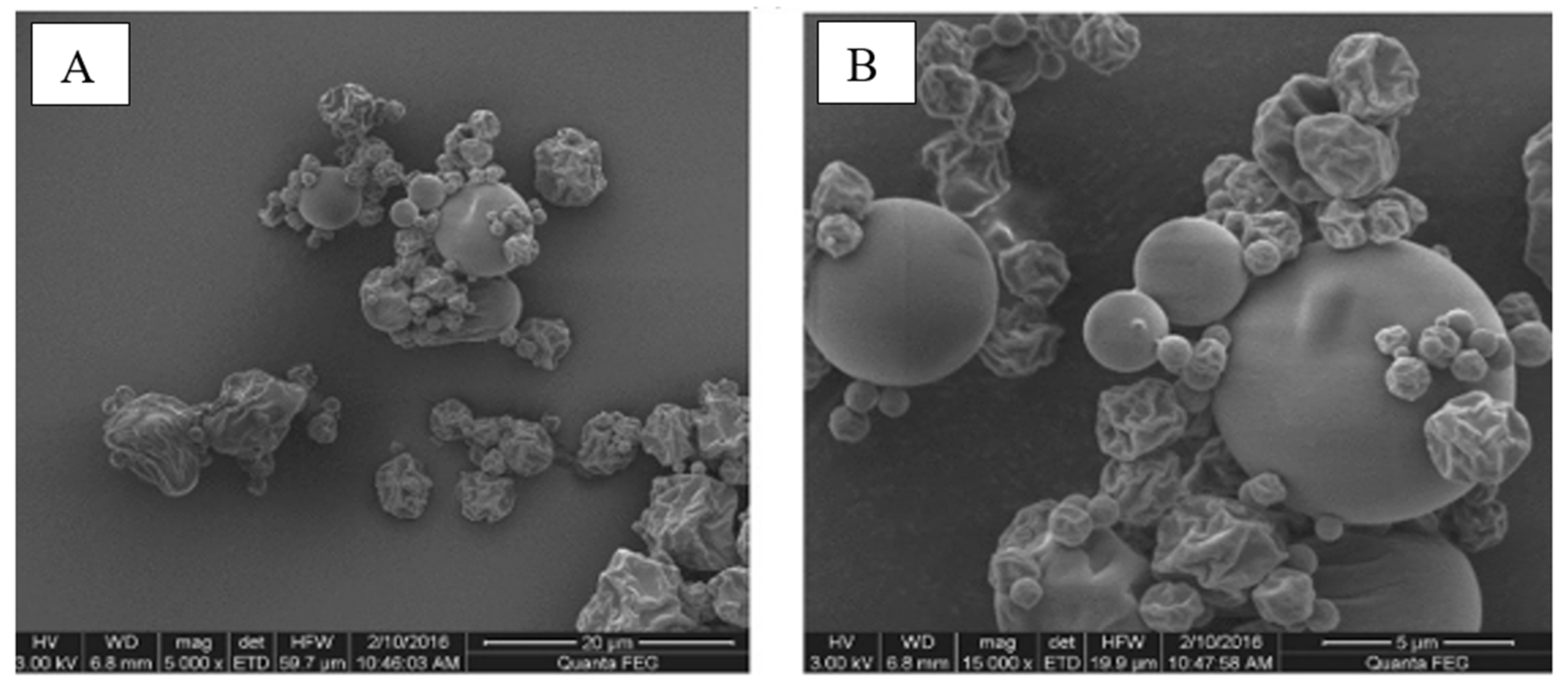

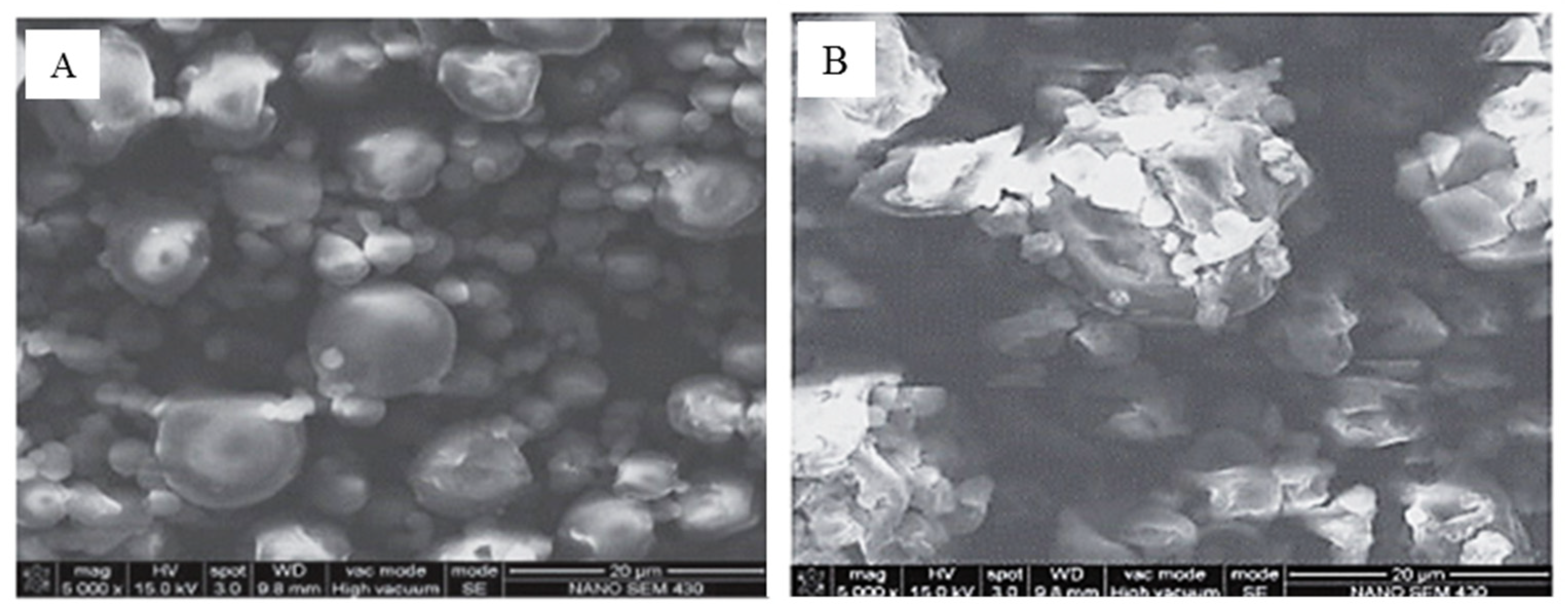

3.1. Spray Drying

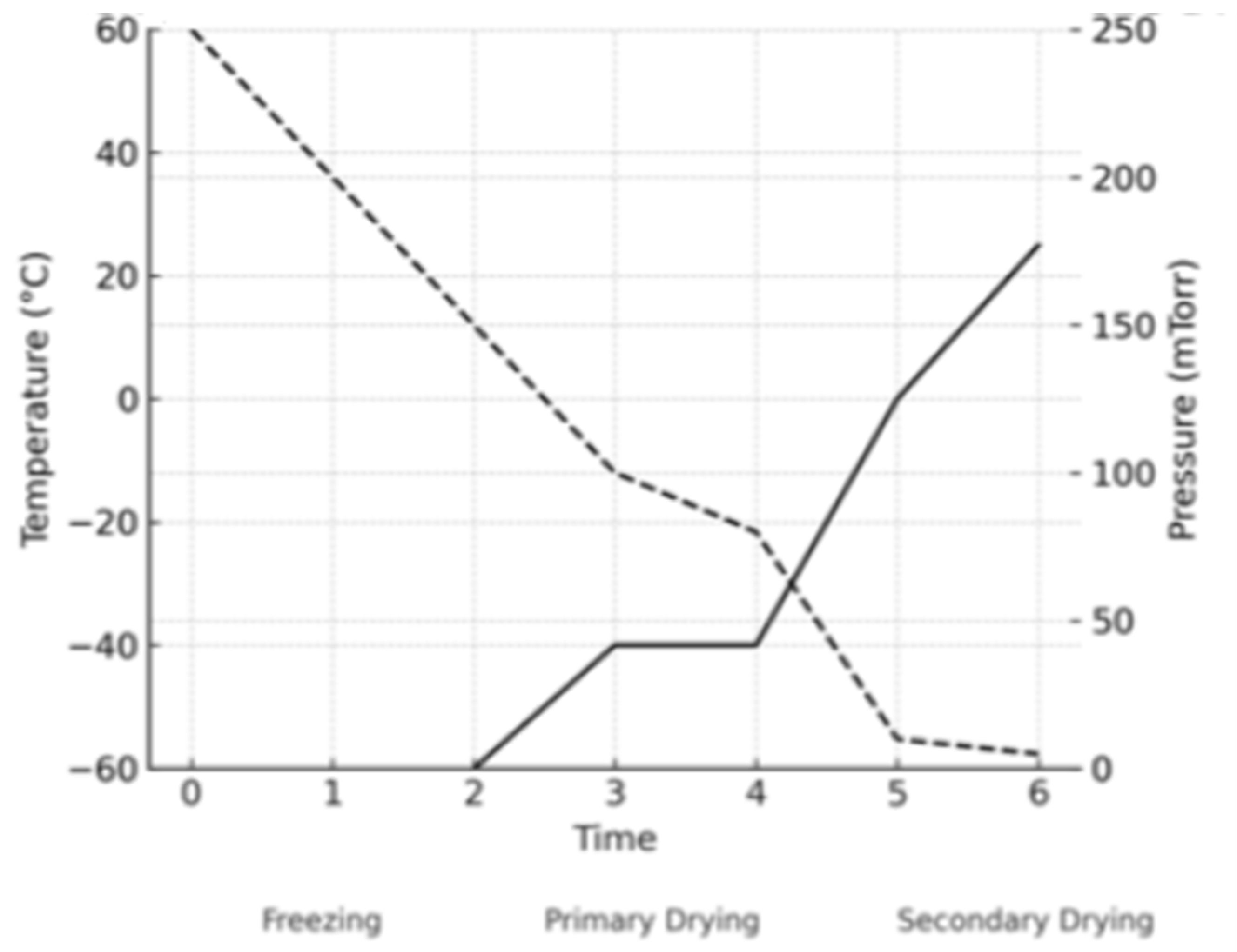

3.2. Freeze Drying

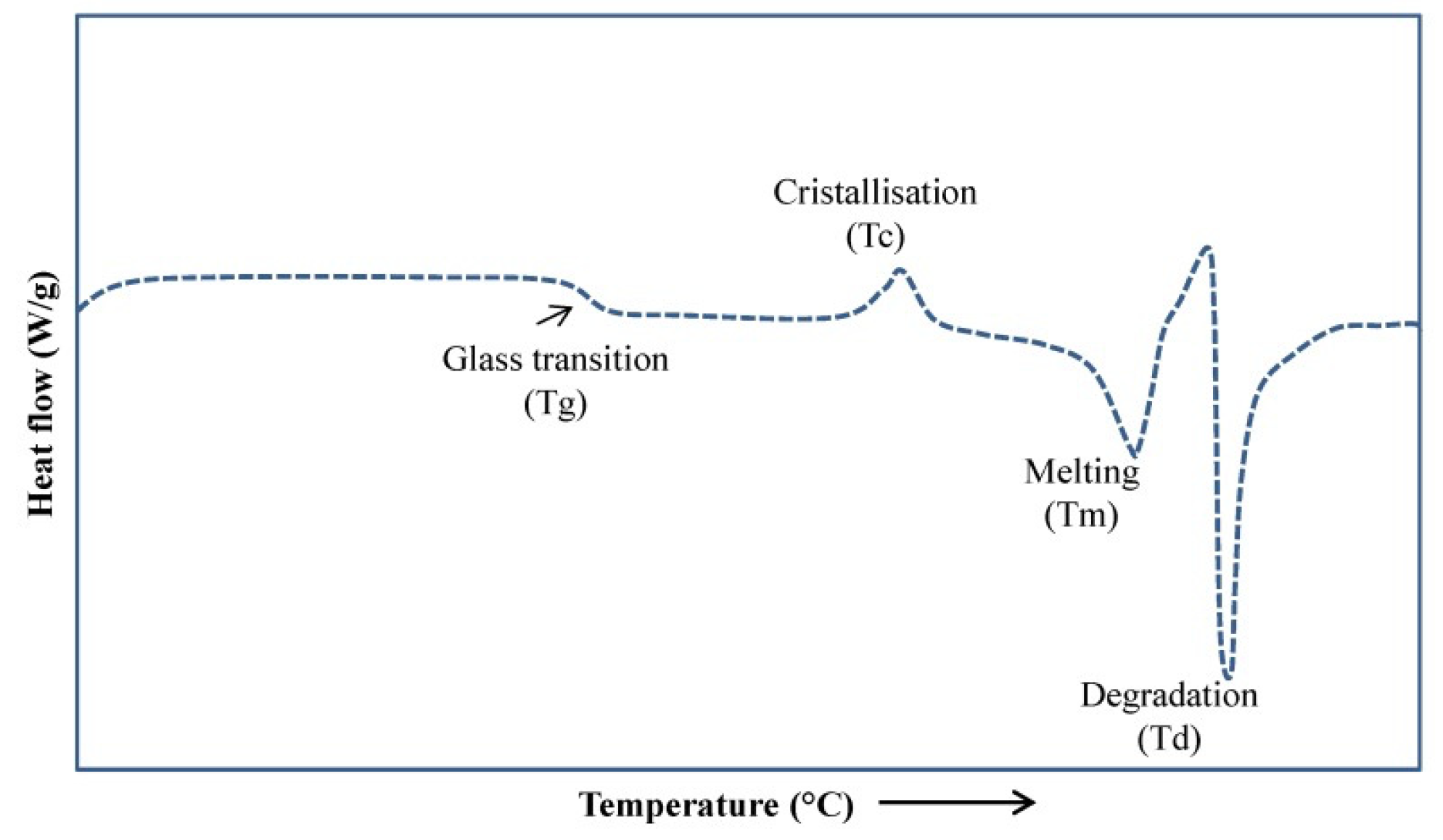

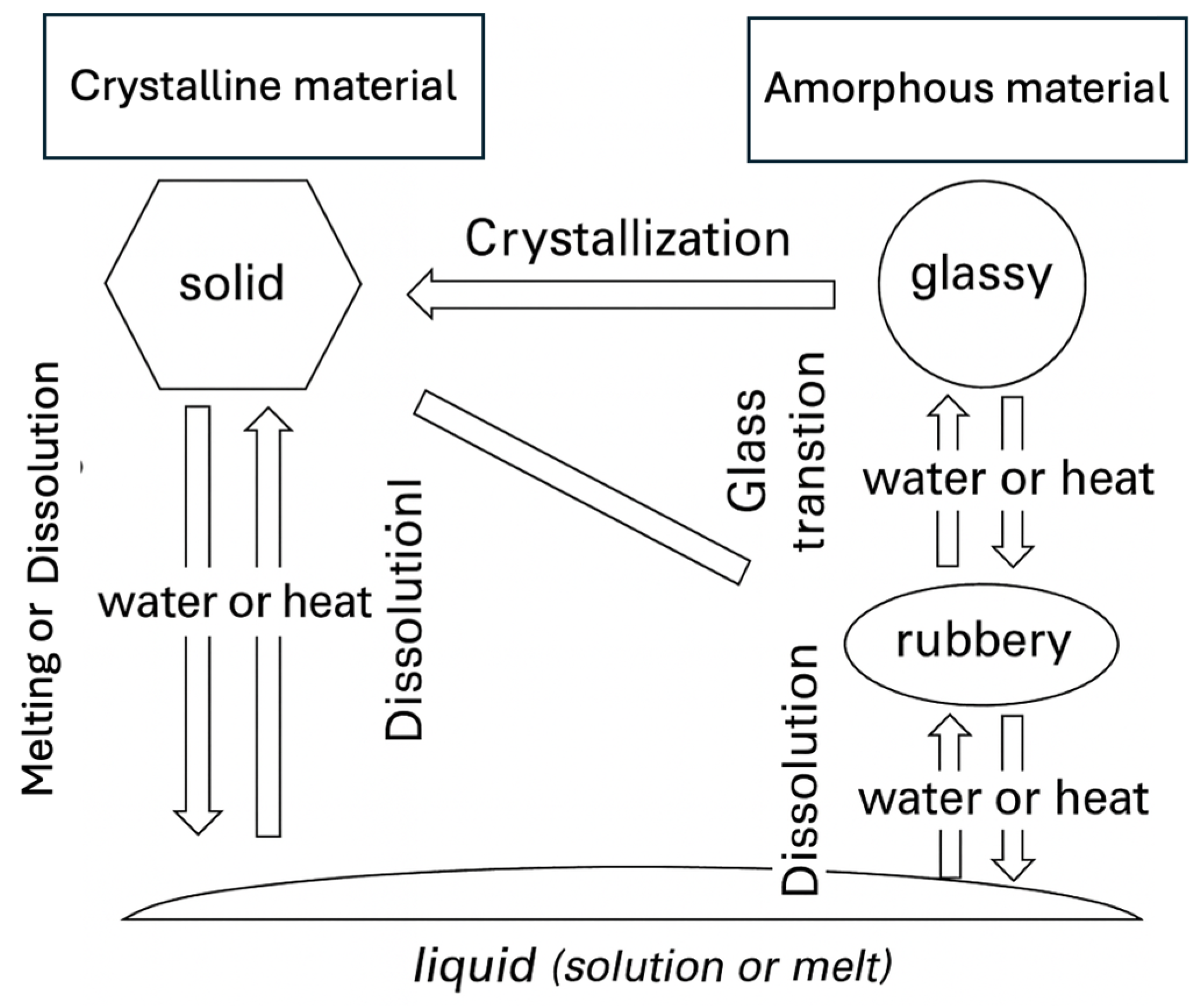

4. Material Science for Food Powders

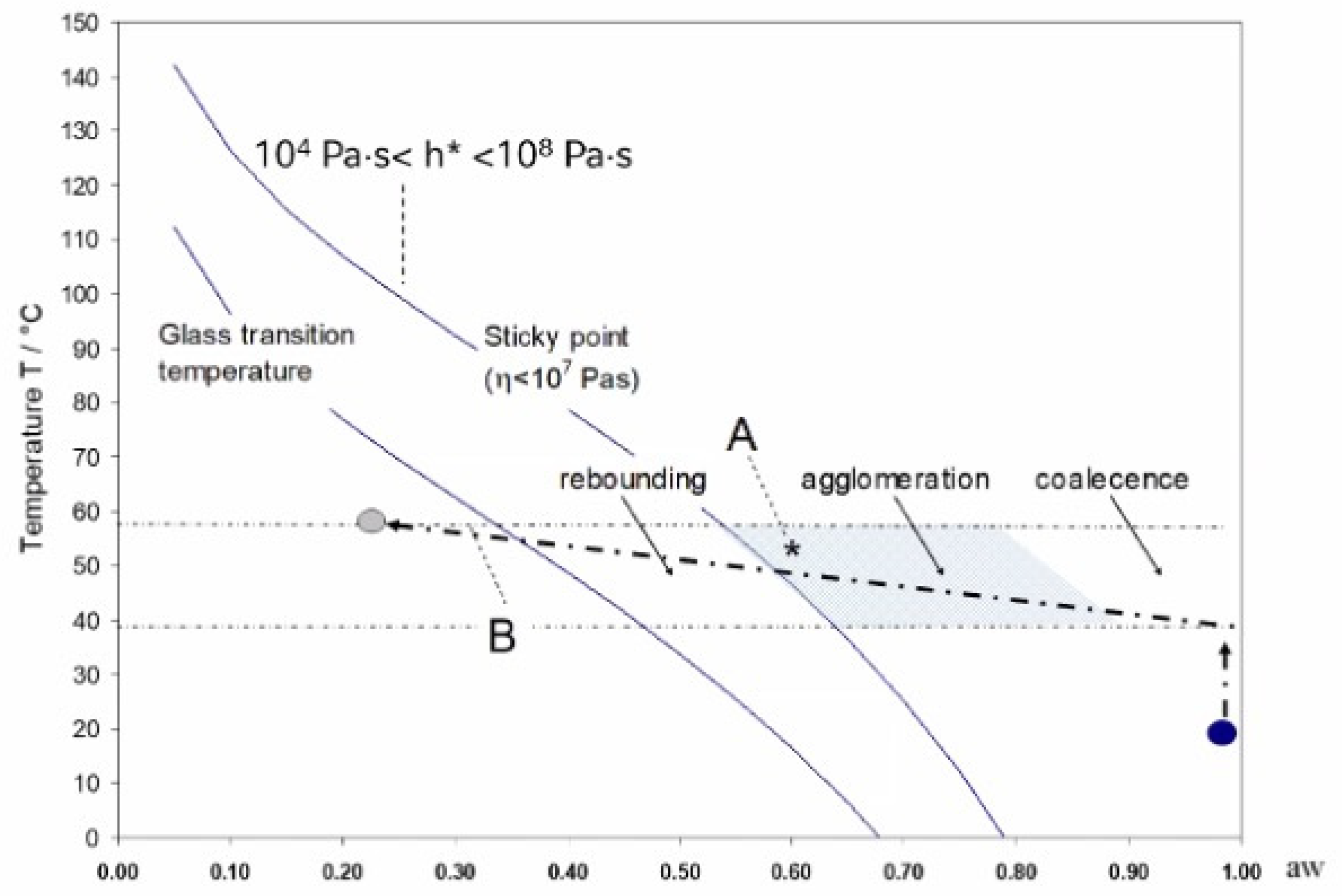

Material Properties, Environmental Conditions (Water, Temperature, Pressure, and Additives)

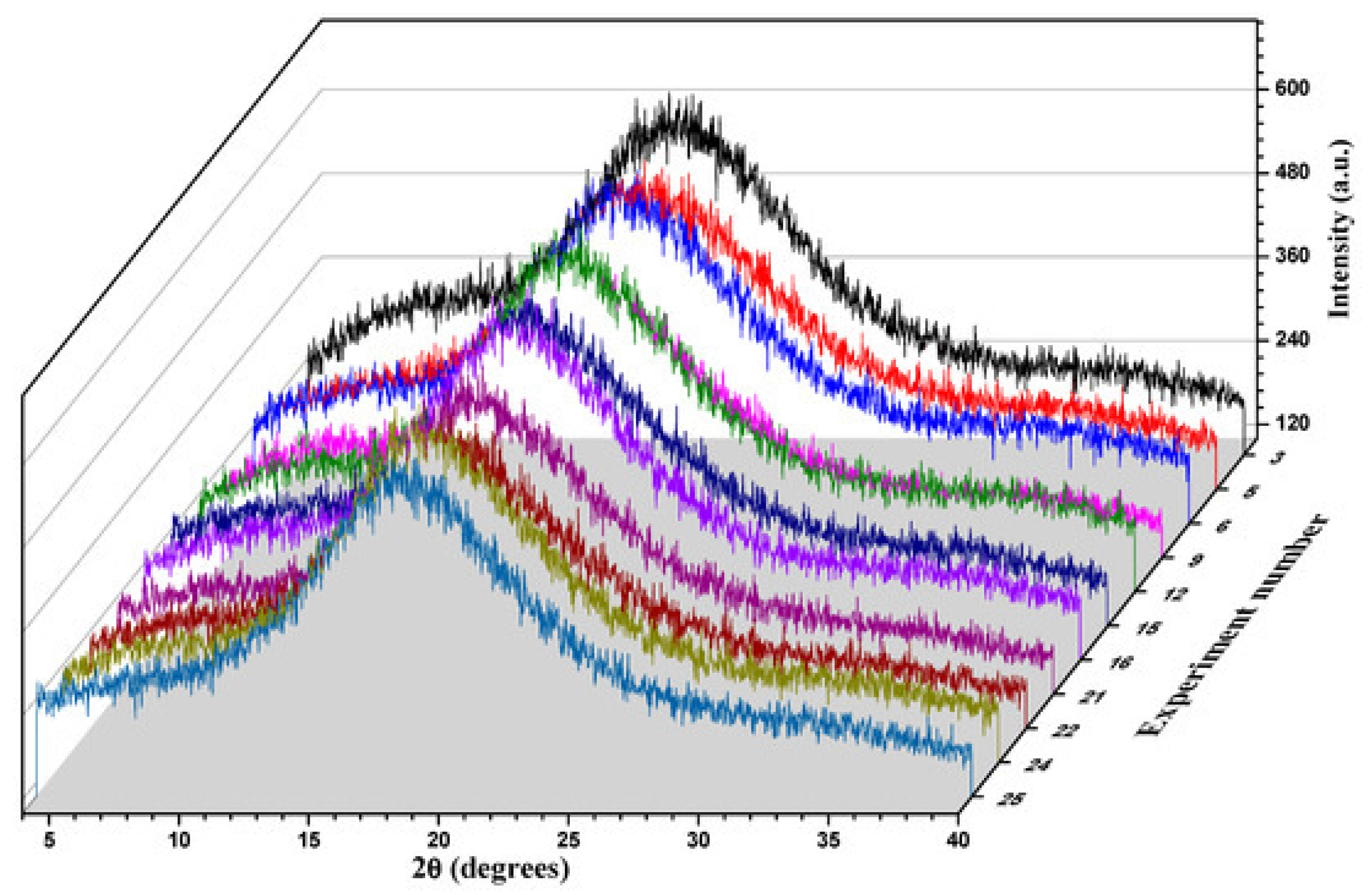

- Microstructure—Crystalline, Amorphous

- b.

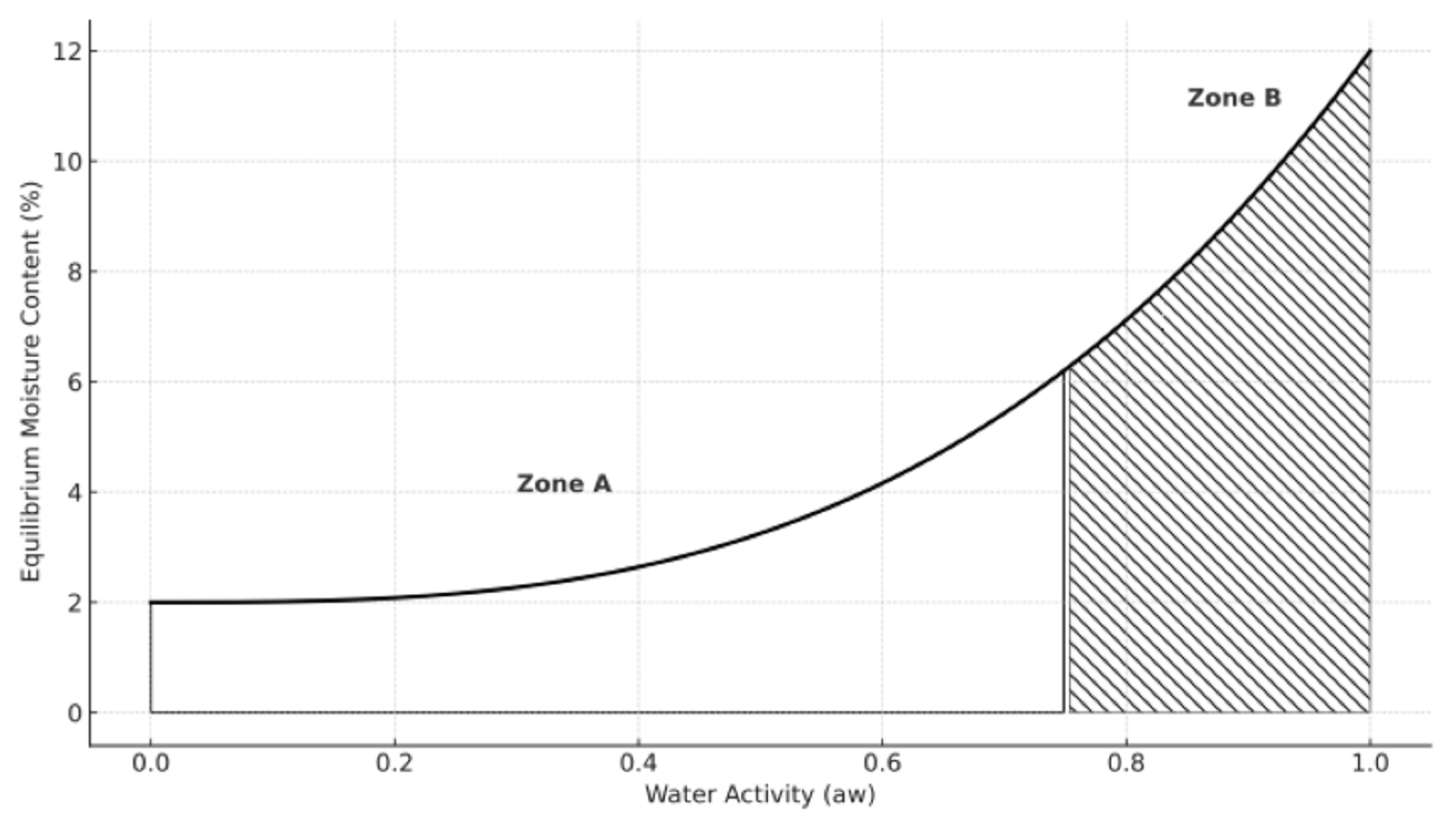

- Moisture Content and Water Sorption Behavior

- c.

- Phase Transformations, Additives

- d.

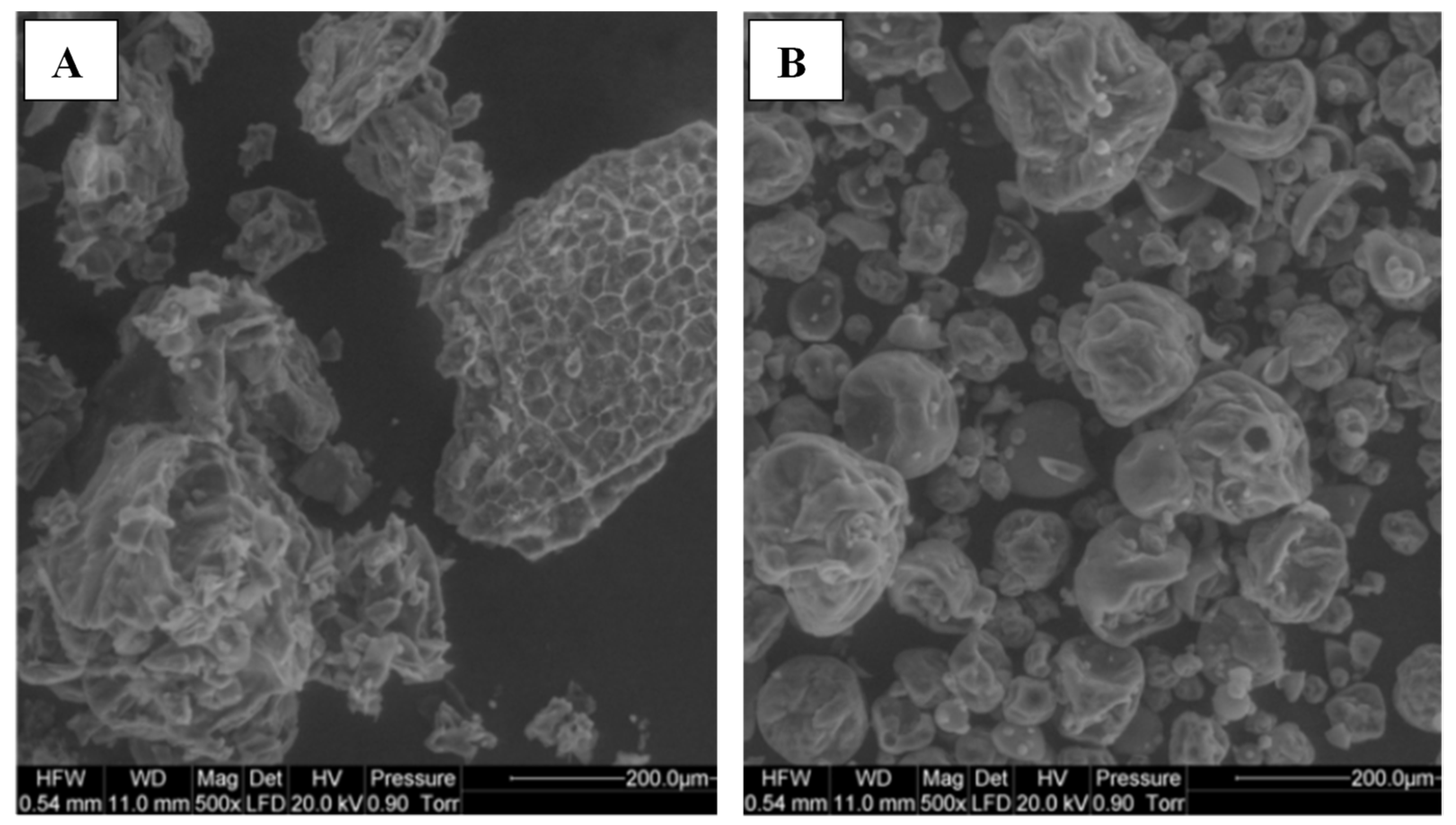

- Particle Morphology

- e.

- Powder Performance—Caking, Flow properties, Reconstitution

5. Trends in the Food Industry and Future Direction

6. Summary

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Skrovankova, S.; Sumczynski, D.; Mlcek, J.; Jurikova, T.; Sochor, J. Bioactive compounds and antioxidant activity in different types of berries. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 24673–24706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nile, S.H.; Park, S.W. Edible berries: Bioactive components and their effect on human health. Nutrition 2014, 30, 134–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz Pineda, C.; Temesgen, T.T.; Robertson, L.J. Multiplex Quantitative PCR Analysis of Strawberries from Bogotá, Colombia, for Contamination with Three Parasites. J. Food Prot. 2020, 83, 1679–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FreshPlaza Colombia Wants to Become a Top 10 Blueberry Exporter in 2020. Available online: https://www.freshplaza.com/article/9189354/colombia-wants-to-become-a-top-10-blueberry-exporter-in-2020/ (accessed on 17 April 2020).

- González, L.K.; Rugeles, L.N.; Magnitskiy, S. Effect of different sources of nitrogen on the vegetative growth of andean blueberry (Vaccinium meridionale swartz). Agron. Colomb. 2018, 36, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, D.A.; Kramer, J.; Calvin, L.; Weber, C.E.; United States, Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. The Changing Landscape of U.S. Strawberry and Blueberry Markets: Production, Trade, and Challenges from 2000 to 2020; Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture: Washington, DC, USA, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Guan, Z.; Whidden, A. An Overview of the US and Mexico Strawberry Industries; IFAS Extension, University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J.; Thakali, K.M.; Jensen, G.S.; Wu, X. Phenolic Acids of the Two Major Blueberry Species in the US Market and Their Antioxidant and Anti-inflammatory Activities. Plant Foods Hum. Nutr. 2015, 70, 56–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordor Intelligence Research & Advisory. Fruit Powder Market Size & Share Analysis—Growth Trends & Forecasts; Mordor Intelligence: Nanakramguda, India, 2025. Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/industry-reports/fruit-powder-market (accessed on 30 August 2025).

- Roos, Y.; Karel, M. Phase Transitions of Mixtures of Amorphous Polysaccharides and Sugars. Biotechnol. Prog. 1991, 7, 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buljeta, I.; Pichler, A.; Šimunović, J.; Kopjar, M. Polysaccharides as Carriers of Polyphenols: Comparison of Freeze-Drying and Spray-Drying as Encapsulation Techniques. Molecules 2022, 27, 5069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaman, B.; Acun, S.; Seyrekoğlu, F.; Ay, E.B. Impact of drying techniques on strawberry powder characteristics. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2025, 19, 6694–6704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, Z.; Yu, M.; Wang, W.; Shi, X. Functionality of spray-dried strawberry powder: Effects of whey protein isolate and maltodextrin. Int. J. Food Prop. 2018, 21, 2229–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, L.H.; Moraga, G.; Martínez-Navarrete, N. Critical water activity and critical water content of freeze-dried strawberry powder as affected by maltodextrin and arabic gum. Food Res. Int. 2012, 47, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurozawa, L.E.; Park, K.J.; Hubinger, M.D. Effect of maltodextrin and gum arabic on water sorption and glass transition temperature of spray dried chicken meat hydrolysate protein. J. Food Eng. 2009, 91, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinal, R.; Carvajal, M.T. Integrating Particle Microstructure, Surface and Mechanical Characterization with Bulk Powder Processing. KONA Powder Part. J. 2020, 37, 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tulipani, S.; Mezzetti, B.; Battino, M. Impact of strawberries on human health: Insight into marginally discussed bioactive compounds for the Mediterranean diet. Public Health Nutr. 2009, 12, 1656–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giampieri, F.; Tulipani, S.; Alvarez-Suarez, J.M.; Quiles, J.L.; Mezzetti, B.; Battino, M. The strawberry: Composition, nutritional quality, and impact on human health. Nutrition 2012, 28, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannum, S.M. Potential Impact of Strawberries on Human Health: A Review of the Science. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2004, 44, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Restrepo, A.M.; Cortés, M.; Rojano, B. Determinación de la vida útil de la fresa (Fragaria ananassa duch.) Fortificada con vitamina e vida útil de la fresa (Fragaria ananassa duch.) Fortificada con vitamina e misael cortés. Año 2009, 76, 163–175. [Google Scholar]

- Hummer, K.E.; Hancock, J.; Folta, K.M. Strawberry Genomics: Botanical History, Cultivation, Traditional Breeding, and New Technologies. In Genetics and Genomics of Rosaceae. Plant Genetics and Genomics: Crops and Models; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock, J.F.; Sjulin, T.M.; Lobos, G.A. Strawberries. In Temperate Fruit Crop Breeding: Germplasm to Genomics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 393–437. ISBN 9781402069079. [Google Scholar]

- Aaby, K.; Mazur, S.; Nes, A.; Skrede, G. Phenolic compounds in strawberry (Fragaria x ananassa Duch.) fruits: Composition in 27 cultivars and changes during ripening. Food Chem. 2012, 132, 86–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishehgarha, F.; Makhlouf, J.; Ratti, C. Freeze-drying characteristics of strawberries. Dry. Technol. 2002, 20, 131–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, F.L.; Escribano-Bailón, M.T.; Pérez Alonso, J.J.; Rivas-Gonzalo, J.C.; Santos-Buelga, C. Anthocyanin pigments in strawberry. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2007, 40, 374–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Rojas, M.E.; Mesa-Torres, P.A.; Grijalba-Rativa, C.M.; Pérez-Trujillo, M.M. Rendimiento y calidad de frutos de los cultivares de arándano Biloxi y Sharpblue en Guasca, Colombia. Agron. Colomb. 2016, 34, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalt, W.; McDonald, J.E.; Ricker, R.D.; Lu, X.; Canada, A.-F.; Ricker, J.E.; Lu, R.D.; Et Lu, R.D. Anthocyanin content and profile within and among blueberry species. Can. J. Plant Sci. 1999, 79, 617–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kerr, W. Vacuum-Belt Drying of Rabbiteye Blueberry (Vaccinium ashei) Slurries: Influence of Drying Conditions on Physical and Quality Properties of Blueberry Powder. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 3227–3237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norberto, S.; Silva, S.; Meireles, M.; Faria, A.; Pintado, M.; Calhau, C. Blueberry anthocyanins in health promotion: A metabolic overview. J. Funct. Foods 2013, 5, 1518–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

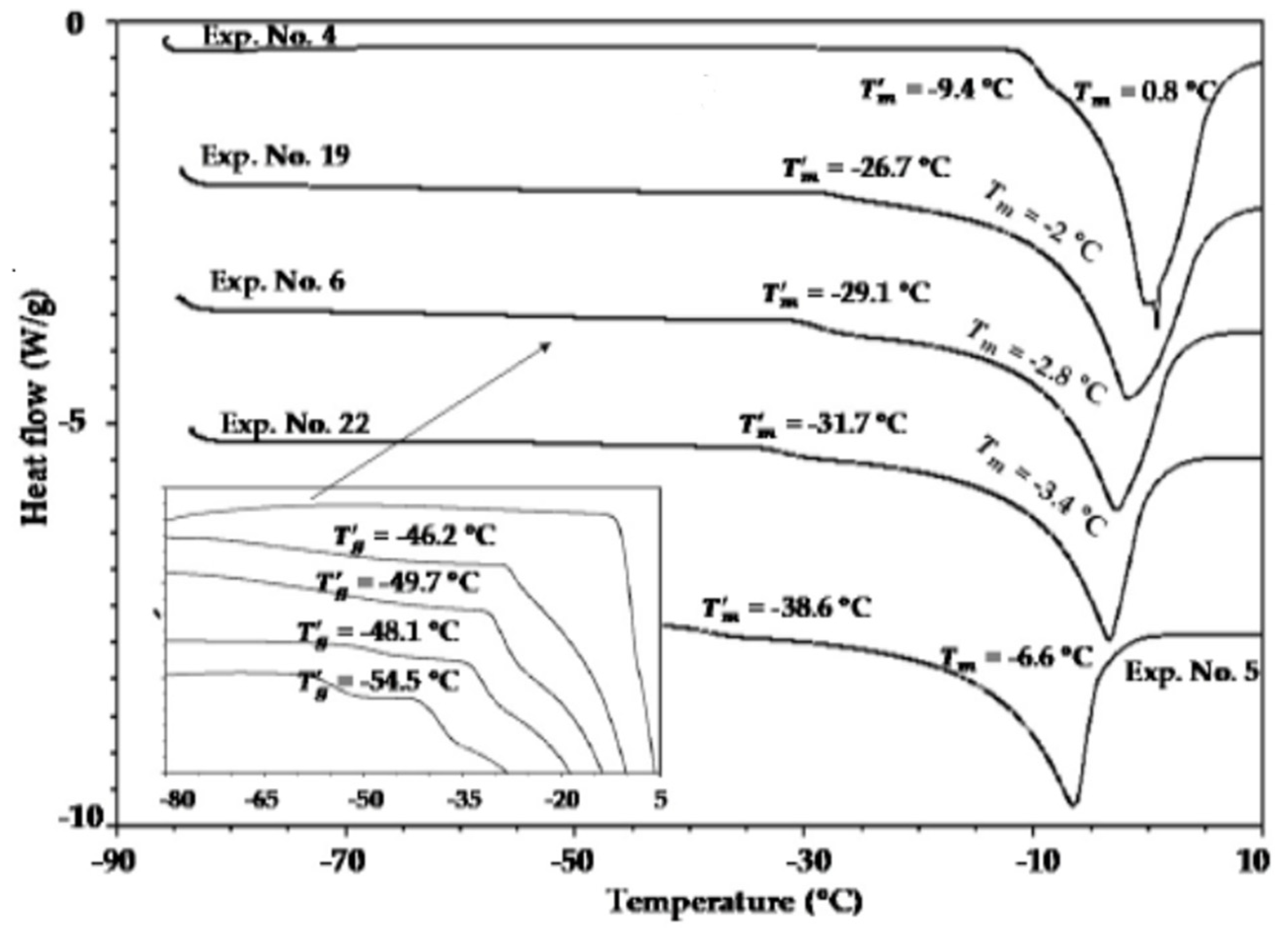

- García-Coronado, P.; Flores-Ramírez, A.; Grajales-Lagunes, A.; Godínez-Hernández, C.; Abud-Archila, M.; González-García, R.; Ruiz-Cabrera, M.A. The Influence of Maltodextrin on the Thermal Transitions and State Diagrams of Fruit Juice Model Systems. Polymers 2020, 12, 2077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalska, A.; Łysiak, G. Bioactive compounds of blueberries: Post-harvest factors influencing the nutritional value of products. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2015, 16, 18642–18663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishir, M.R.I.; Chen, W. Trends of spray drying: A critical review on drying of fruit and vegetable juices. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 65, 49–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkacz, K.; Wojdyło, A.; Michalska-Ciechanowska, A.; Turkiewicz, I.P.; Lech, K.; Nowicka, P. Influence Carrier Agents, Drying Methods, Storage Time on Physico-Chemical Properties and Bioactive Potential of Encapsulated Sea Buckthorn Juice Powders. Molecules 2020, 25, 3801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilbao-Sainz, C.; Sinrod, A.J.G.; Chiou, B.-S.; McHugh, T. Functionality of strawberry powder on frozen dairy desserts. J. Texture Stud. 2019, 50, 556–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nemzer, B.; Vargas, L.; Xia, X.; Sintara, M.; Feng, H. Phytochemical and physical properties of blueberries, tart cherries, strawberries, and cranberries as affected by different drying methods. Food Chem. 2018, 262, 242–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muzaffar, K.; Nayik, G.; Kumar, P. Stickiness Problem Associated with Spray Drying of Sugar and Acid Rich Foods: A Mini Review. Food Nutr. Sci. 2015, S12, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etzbach, L.; Meinert, M.; Faber, T.; Klein, C.; Schieber, A.; Weber, F. Effects of carrier agents on powder properties, stability of carotenoids, and encapsulation efficiency of goldenberry (Physalis peruviana L.) powder produced by co-current spray drying. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2020, 3, 73–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, C.C.; Marconi Germer, S.P.; Alvim, I.D.; de Aguirre, J.M. Storage Stability of Spray-Dried Blackberry Powder Produced with Maltodextrin or Gum Arabic. Dry. Technol. 2013, 31, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todorović, A.; Šturm, L.; Salević-Jelić, A.; Lević, S.; Osojnik Črnivec, I.G.; Prislan, I.; Skrt, M.; Bjeković, A.; Poklar Ulrih, N.; Nedović, V. Encapsulation of Bilberry Extract with Maltodextrin and Gum Arabic by Freeze-Drying: Formulation, Characterisation, and Storage Stability. Processes 2022, 10, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkiewicz, I.P.; Wojdyło, A.; Tkacz, K.; Lech, K.; Michalska-Ciechanowska, A.; Nowicka, P. The influence of different carrier agents and drying techniques on physical and chemical characterization of Japanese quince (Chaenomeles japonica) microencapsulation powder. Food Chem. 2020, 323, 126830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šturm, L.; Osojnik Črnivec, I.G.; Istenič, K.; Ota, A.; Megušar, P.; Slukan, A.; Humar, M.; Levic, S.; Nedović, V.; Kopinč, R.; et al. Encapsulation of non-dewaxed propolis by freeze-drying and spray-drying using gum Arabic, maltodextrin and inulin as coating materials. Food Bioprod. Process. 2019, 116, 196–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santivarangkna, C.; Kulozik, U.; Foerst, P. Alternative drying processes for the industrial preservation of lactic acid starter cultures. Biotechnol. Prog. 2007, 23, 302–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazaeli, M.; Emam-Djomeh, Z.; Kalbasi Ashtari, A.; Omid, M. Effect of spray drying conditions and feed composition on the physical properties of black mulberry juice powder. Food Bioprod. Process. 2012, 90, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palzer, S. Agglomeration of pharmaceutical, detergent, chemical and food powders—Similarities and differences of materials and processes. Powder Technol. 2011, 206, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratti, C. Freeze Drying for Food Powder Production; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Sawston, UK, 2013; ISBN 9780857098672. [Google Scholar]

- Nail, S.L.; Jiang, S.; Chongprasert, S.; Knopp, S.A. Fundamentals of Freeze-Drying. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2002, 14, 281–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Feng, X. Exergy analysis for a freeze-drying process. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2008, 28, 675–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

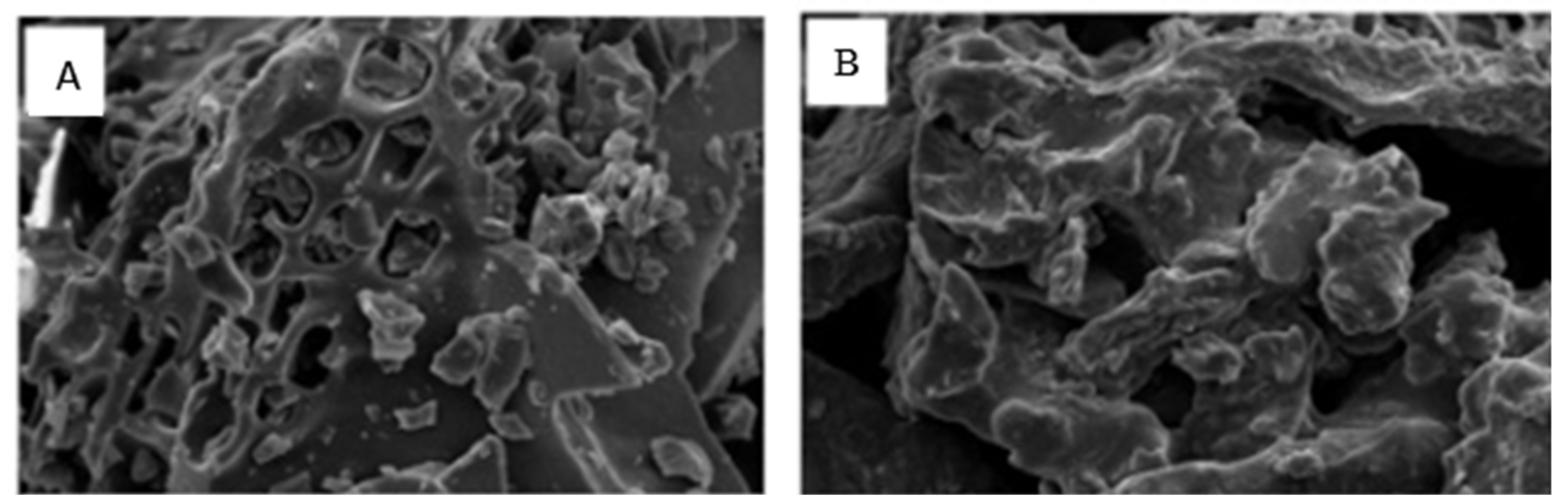

- Khalloufi, S.; Ratti, C. Quality deterioration of freeze-dried foods as explained by their glass transition temperature and internal structure. J. Food Sci. 2003, 68, 892–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, D.; Jakubczyk, E. The Freeze-Drying of Foods—The Characteristic of the Process Course and the Effect of Its Parameters on the Physical Properties of Food Materials. Foods 2020, 9, 1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantawittayanon, S.; Mochizuki, T.; Kawai, K. Effects of Water Activity and Temperature on the Caking Properties of Amorphous Carbohydrate Powders. J. Appl. Glycosci. 2025, 72, 7201103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechanteur, A.; Evrard, B. Influence of Composition and Spray-Drying Process Parameters on Carrier-Free DPI Properties and Behaviors in the Lung: A review. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depaz, R.A.; Pansare, S.; Patel, S.M. Freeze-Drying Above the Glass Transition Temperature in Amorphous Protein Formulations While Maintaining Product Quality and Improving Process Efficiency. J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 105, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Taip, F.; Abdullah, Z. Effectiveness of additives in spray drying performance: A review. Food Res. 2018, 2, 486–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, Y.; Wu, Y.; Yang, J.; Jiang, N.; Wang, Q.; Chu, D.T.; Han, Y.; Zhou, J. Thermodynamic sorption properties, water plasticizing effect and particle characteristics of blueberry powders produced from juices, fruits and pomaces. Powder Technol. 2018, 323, 208–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

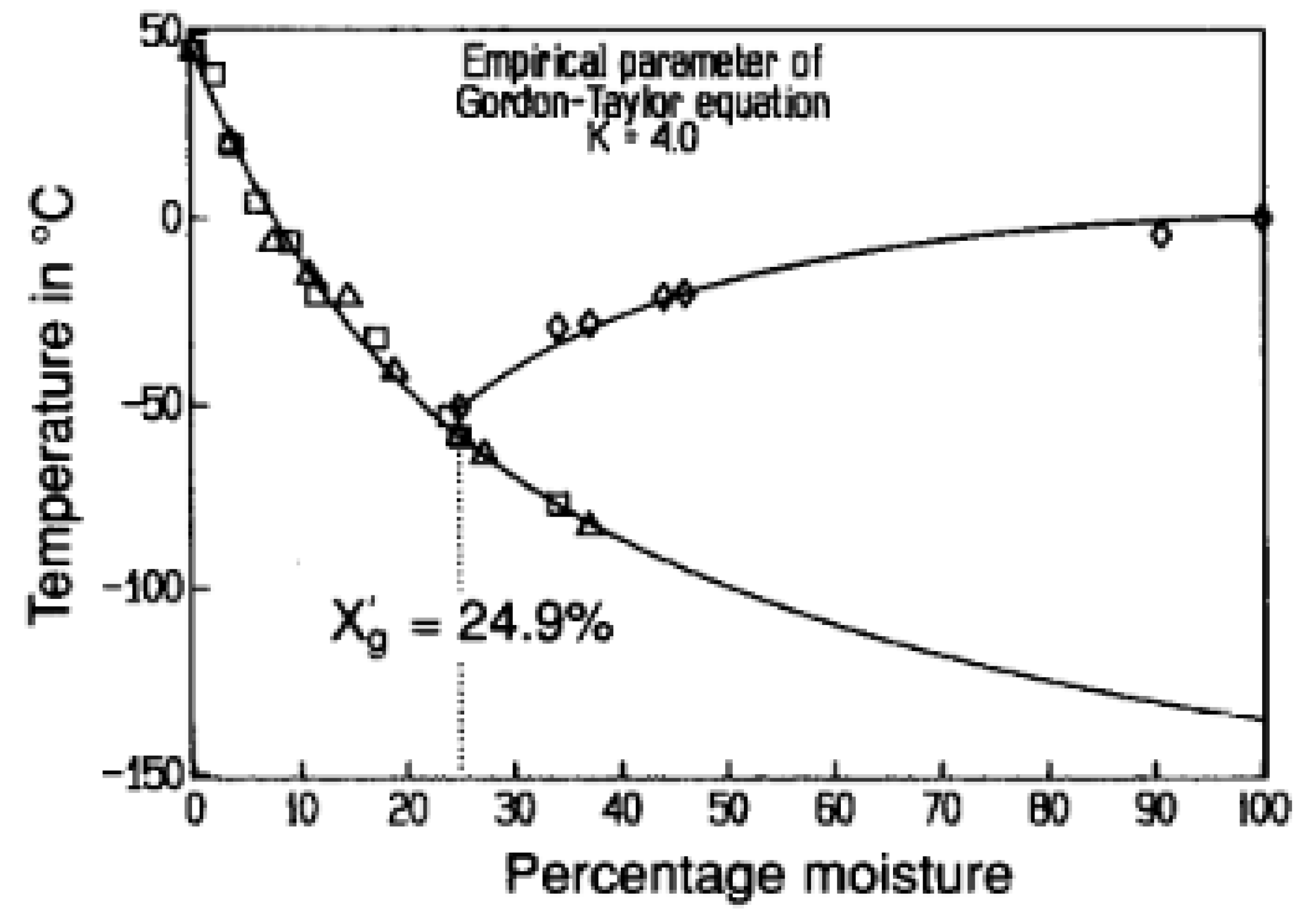

- Roos, Y.H. Effect of Moisture on the Thermal Behavior of Strawberries Studied using Differential Scanning Calorimetry. J. Food Sci. 1987, 52, 146–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noel, T.R.; Ring, S.G.; Whittam, M.A. Glass transitions in low-moisture foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1990, 1, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaya, S.; Das, H. Glass transition and sticky point temperatures and stability/mobility diagram of fruit powders. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2009, 2, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyva-Porras, C.; Cruz-Alcantar, P.; Espinosa-Solís, V.; Martínez-Guerra, E.; Piñón-Balderrama, C.I.; Martínez, I.C.; Saavedra-Leos, M.Z. Application of Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and Modulated Differential Scanning Calorimetry (MDSC) in Food and Drug Industries. Polymers 2019, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damond, C. Food Science: Mastering Powders. In Proceedings of the Nestlé Food Science & Technology Seminars, Online, 10 October 2025; Available online: https://events.zoom.us/ev/Ag35fF4KK5b66xmWg5-YAABSG4VG435NvUAIPqYFcZhLV08JET0K~Ap0hI96iG4bUeB63MLM9dX_MGAMmLi8ghXbT4jCCnbVp17lA6sKzzwYTxA (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Peng, Y.; Han, Y.; Gardner, D.J. Spray-drying cellulose nanofibrils: Effect of drying process parameters on particle morphology and size distribution. Wood Fiber Sci. 2012, 44, 448–461. [Google Scholar]

- Kawai, K.; Fukami, K.; Thanatuksorn, P.; Viriyarattanasak, C.; Kajiwara, K. Effects of moisture content, molecular weight, and crystallinity on the glass transition temperature of inulin. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 83, 934–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chegini, G.R.; Ghobadian, B. Effect of spray-drying conditions on physical properties of orange juice powder. Dry. Technol. 2005, 23, 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Descamps, N.; Palzer, S.; Roos, Y.H.; Fitzpatrick, J.J. Glass transition and flowability/caking behaviour of maltodextrin de 21. J. Food Eng. 2013, 119, 809–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darniadi, S.; Ho, P.; Murray, B.S. Comparison of blueberry powder produced via foam-mat freeze-drying versus spray-drying: Evaluation of foam and powder properties. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 2002–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Muhtaseb, A.H.; McMinn, W.A.M.; Magee, T.R.A. Moisture sorption isotherm characteristics of food products: A review. Food Bioprod. Process. Trans. Inst. Chem. Eng. Part C 2002, 80, 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Du, X.; Cui, D.; Wang, X.; Yang, Z.; Zhu, G. Improvement of stability of blueberry anthocyanins by carboxymethyl starch/xanthan gum combinations microencapsulation. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 91, 238–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, H.A.; Chirife, J. An alternative to the Guggenheim, Anderson and De Boer model for the mathematical description of moisture sorption isotherms of foods. Food Res. Int. 1995, 28, 317–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Shi, P.; Yan, W.; Chen, L.; Qian, L.; Kim, S.H. Thickness and Structure of Adsorbed Water Layer and Effects on Adhesion and Friction at Nanoasperity Contact. Colloids Interfaces 2019, 3, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, L.T.; Tang, J.; He, J. Moisture Sorption Characteristics of Freeze Dried Blueberries. J. Food Sci. 1995, 60, 810–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, L.H.; Moraga, G.; Fernández de Córdoba, P.; Martínez-Navarrete, N. Water Content–Water Activity–Glass Transition Temperature Relationships of Spray-Dried Borojó as Related to Changes in Color and Mechanical Properties. Food Biophys. 2011, 6, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vásquez, C.; Díaz-Calderón, P.; Enrione, J.; Matiacevich, S. State diagram, sorption isotherm and color of blueberries as a function of water content. Thermochim. Acta 2013, 570, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Do, H.T.T.; Nguyen, H.V.H. Effects of Spray-Drying Temperatures and Ratios of Gum Arabic to Microcrystalline Cellulose on Antioxidant and Physical Properties of Mulberry Juice Powder. Beverages 2018, 4, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogrodowska, D.; Tańska, M.; Brandt, W. The Influence of Drying Process Conditions on the Physical Properties, Bioactive Compounds and Stability of Encapsulated Pumpkin Seed Oil. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2017, 10, 1265–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ElGamal, R.; Song, C.; Rayan, A.M.; Liu, C.; Al-Rejaie, S.; ElMasry, G. Thermal Degradation of Bioactive Compounds during Drying Process of Horticultural and Agronomic Products: A Comprehensive Overview. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estupiñan-Amaya, M.; Fuenmayor, C.A.; López-Córdoba, A. Evaluation of mixtures of maltodextrin and gum Arabic for the encapsulation of Andean blueberry (Vaccinium meridionale) juice by freeze–drying. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 57, 7379–7390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonon, R.; Baroni, A.; Brabet, C.; Gibert, O.; Pallet, D.; Hubinger, M. Water sorption and glass transition temperature of spray dried açai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.) juice. J. Food Eng. 2009, 94, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vehring, R. Pharmaceutical Particle Engineering via Spray Drying. Pharm. Res. 2008, 25, 999–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, Y. Importance of glass transition and water activity to spray drying and stability of dairy powders. Lait 2002, 82, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, B.; Howes, T.; Bhandari, B.R.; Truong, V. Stickiness in Foods: A Review of Mechanisms and Test Methods. Int. J. Food Prop. 2001, 4, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welti-Chanes, J.; Guerrero, J.; Barcenas, M.; Aguilera, J.; Vergara, F.; Barbosa-Canovas, G. Glass transition temperature (Tg) and water activity (aw) of dehydrated apple products. J. Food Eng. 1998, 22, 91–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franceschinis, L.; Salvatori, D.M.; Sosa, N.; Schebor, C. Physical and Functional Properties of Blackberry Freeze- and Spray-Dried Powders. Dry. Technol. 2014, 32, 197–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, Y.; Karel, M. Plasticizing Effect of Water on Thermal Behavior and Crystallization of Amorphous Food Models. J. Food Sci. 1991, 56, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, J.A.; Kim, S.J.; Kwon, H.J.; Yang, Y.S.; Kim, H.K.; Hwang, Y.H. The glass transition temperatures of sugar mixtures. Carbohydr. Res. 2006, 341, 2516–2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sá, M.M.; Sereno, A.M. Glass transitions and state diagrams for typical natural fruits and vegetables. Thermochim. Acta 1994, 246, 285–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalloufi, S.; El-Maslouhi, Y.; Ratti, C. Mathematical model for prediction of glass transition temperature of fruit powders. J. Food Sci. 2000, 65, 842–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saavedra-Leos, M.Z.; Alvarez-Salas, C.; Esneider-Alcalá, M.A.; Toxqui-Terán, A.; Pérez-García, S.A.; Ruiz-Cabrera, M.A. Towards an improved calorimetric methodology for glass transition temperature determination in amorphous sugars. CYTA J. Food 2012, 10, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goula, A.M.; Adamopoulos, K.G. Effect of maltodextrin addition during spray drying of tomato pulp in dehumidified air: I. Drying kinetics and product recovery. Dry. Technol. 2008, 26, 714–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimeri, J.E.; Kokini, J.L. The effect of moisture content on the crystallinity and glass transition temperature of inulin. Carbohydr. Polym. 2002, 48, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, K.; Judson King, C. Factors Governing Surface Morphology Of Spray-Dried Amorphous Substances. Dry. Technol. 1985, 3, 321–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.; Ma, M.; Dolan, K.D. Effects of Spray Drying on Antioxidant Capacity and Anthocyanidin Content of Blueberry By-Products. J. Food Sci. 2011, 76, H156–H164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, B.; Mustapha, A.T.; Al-Awaadh, A.M.; Ahmed, K.A.M. Physical and moisture sorption thermodynamic properties of Sukkari date (Phoenix dactylifera L.) powder. CyTA J. Food 2020, 18, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, D.E.; Mumford, C.J. Spray Dried Products—Characterization of Particle Morphology. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 1999, 77, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadowska, A.; Świderski, F.; Hallmann, E. Bioactive, Physicochemical and Sensory Properties as Well as Microstructure of Organic Strawberry Powders Obtained by Various Drying Methods. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 4706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chávez Montes, B.E.; Martínez-Alejo, J.M.; Lozano-Perez, H.; Gumy, J.C.; Zemlyanov, D.; Carvajal, M.T. A surface characterization platform approach to study Flowability of food powders. Powder Technol. 2019, 357, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamarthy, S.P.; Pinal, R.; Carvajal, M.T. Elucidating raw material variability-importance of surface properties and functionality in pharmaceutical powders. AAPS PharmSciTech 2009, 10, 780–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawoodbhai, S.; Rhodes, C.T. The effect of moisture on powder flow and on compaction and physical stability of tablets. Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 1989, 15, 1577–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathlouthi, M.; Rogé, B. Water vapour sorption isotherms and the caking of food powders. Food Chem. 2003, 82, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagneten, M.; Corfield, R.; Mattson, M.G.; Sozzi, A.; Leiva, G.; Salvatori, D.; Schebor, C. Spray-dried powders from berries extracts obtained upon several processing steps to improve the bioactive components content. Powder Technol. 2019, 342, 1008–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Jiang, Y.; Zhou, W. Characteristics of soy sauce powders spray-dried using dairy whey proteins and maltodextrins as drying aids. J. Food Eng. 2013, 119, 724–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samain, S.; Dupas-Langlet, M.; Leturia, M.; Benali, M.; Saleh, K. Caking of sucrose: Elucidation of the drying kinetics according to the relative humidity by considering external and internal mass transfer. J. Food Eng. 2017, 212, 298–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosquera, L.H.; Moraga, G.; Martínez-Navarrete, N. Mechanical Changes in Freeze-Dried Strawberry Powder As Affected By Water Activity, Glass Transition and Carbohydrate Polymers Addition. Food Res. Int. 2011, 47, 201–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, J.M.; del Valle, J.M.; Karel, M. Caking phenomena in amorphous food powders. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 1995, 6, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuy, L.E.; Labuza, T.P. Caking and Stickiness of Dairy-Based Food Powders as Related to Glass Transition. J. Food Sci. 1994, 59, 43–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrassiabian, Z.; Saleh, K. Caking of anhydrous lactose powder owing to phase transition and solid-state hydration under humid conditions: From microscopic to bulk behavior. Powder Technol. 2020, 363, 488–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, C.I.; Hounslow, M.J.; Salman, A.D.; Althaus, T.O.; Niederreiter, G.; Palzer, S. Influence of environmental conditions on caking mechanisms in individual amorphous food particle contacts. AIChE J. 2014, 60, 2774–2787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, M.Y.; Yusof, Y.A.; Aziz, M.G.; Chin, N.L.; Amin, N.A.M. Characterisation of fast dispersible fruit tablets made from green and ripe mango fruit powders. J. Food Eng. 2014, 125, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saifullah, M.; Yusof, Y.A.; Chin, N.L.; Aziz, M.G. Physicochemical and flow properties of fruit powder and their effect on the dissolution of fast dissolving fruit powder tablets. Powder Technol. 2016, 301, 396–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legard, D. Dietary Supplements Containing Dehydrated Strawberry. US20180078598A1, 22 March 2018. Available online: https://patents.google.com/patent/US20180078598A1/en (accessed on 21 May 2020).

- Çopur, Ö.U.; İncedayı, B.; Karabacak, A.Ö. Technology and Nutritional Value of Powdered Drinks. In Production and Management of Beverages; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 47–83. [Google Scholar]

| Component | Content |

|---|---|

| Water | 90% |

| Carbohydrates | 7.68% |

| Sugars | 4.89% |

| Sucrose | 0.47% |

| Glucose | 1.99% |

| Fructose | 2.44% |

| Protein | 0.67% |

| Fat | 0.3% |

| Dietary fiber | 2.0% |

| Vitamin C | 58.8 mg/100 g |

| Polyphenols | 57 to 133 mg/100 g |

| Anthocyanins | 8.5–65.9 mg/100 g |

| Flavan-3-ols | 11–45 mg/100 g |

| Ellagitannins | 7.7–18.2 mg/100 g |

| Component | Content |

|---|---|

| Water | 84% |

| Carbohydrates | 9.7% |

| Sucrose | 0.11% |

| Glucose | 4.88% |

| Fructose | 4.97% |

| Protein | 0.6% |

| Lipids | 0.4% |

| Dietary fiber | 3–3.5% |

| Vitamin C | 10 mg/100 g |

| Polyphenols | 48–304 mg/100 g |

| Anthocyanin | 25–495 mg/100 g |

| Delphinidin | 27–40% |

| Malvidin | 22–33% |

| Petunidin | 19–26% |

| Cyanidin | 6–14% |

| Challenge | Underlying Cause(s) | Impact on Powder or Process |

|---|---|---|

| Stickiness during drying | High sugar content; Low Tg; Exceeding Tg during spray drying | Powder adheres to dryer wall, reduces yield, clogs equipment |

| Caking | Moisture uptake; Hygroscopic matrix; Structural collapse | Loss of flow, formation of lumps, poor rehydration |

| Agglomeration / Lumping | Capillary bridges; Mechanical compression; Surface stickiness | Reduced powder quality and handling; impaired uniformity in final product |

| Low reconstitution performance | Low wettability; Crystalline regions; Surface hydrophobicity | Poor solubility, slow dispersion, sedimentation, floating particles |

| Foaming during rehydration | Use of protein-based carriers (e.g., WPI); rapid agitation | Excessive foam formation in beverages or reconstituted products |

| Structural collapse (freeze drying) | Exceeding collapse temp (Tc); Insufficient control of sublimation front | Loss of porous matrix, shrinkage, texture degradation |

| Flowability issues | Fine particle size; Irregular shape; Surface electrostatics; High cohesion | Difficulty in handling, packaging, and dosing; segregation; poor compaction |

| Anthocyanin & Vitamin C degradation | Exposure to oxygen, light, high temp | Loss of antioxidant activity, faded color, off-flavors |

| Batch-to-batch variability | Variations in fruit composition (e.g., solids content, pH, sugar:acid ratio) | Inconsistent powder properties; poor process reproducibility |

| Economic constraints | Freeze drying is expensive; spray drying has low yield without carriers | Trade-off between cost and quality; limited adoption for premium products |

| Lack of predictive modeling | Insufficient data on Tg, aw, CWC for specific fruit matrices | Empirical trial-and-error dominates R&D; poor scalability |

| Spray Drying | Freeze Drying | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physico-chemical properties |

|

| Garcia-Coronado et al. [30]; Santivarangkna et al. [42]; Fazaeli et al. [43]; Nail et al. [46]; Peng et al. [60]; Gong et al. [13]; Kawai et al. [61]. |

| Solid-State | Amorphous | Amorphous | |

| Performance |

|

| Chegini and Ghobadian [62]; Descamps et al. [63]; Kawai et al. [61]; Kurozawa et al. [15]. |

| Product | T1 (K) | T2 (K) | T’g (K) | Tgs (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dextran | 264.15 | - | ~261.15 | 357.15 |

| Fructose | 225.15 | 310.15 | 216.15 | 286.15 |

| Glucose | 233.15 | 308.15 | 216.15 | 312.15 |

| Sucrose | 241.15 | 329.15 | 227.15, 238.85 | 343.15 |

| Sorbitol | 228.15 | - | 210.15, 225.25 | 270.15 |

| Blueberry powder | - | - | - | 295.15 |

| Strawberry powder | - | - | - | 314.15 |

| Stage | Morphology | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Free flowing | 1 | 0 |  |

| Bridging | ~1 | ~0 |  |

| Agglomeration | <1 | >0 |  |

| Compaction | ~0 | ~1 |  |

| Liquefaction | 0 | 1 |  |

| Aspect | Spray Drying | Freeze Drying (Lyophilization) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Applications | - Instant beverages - Infant foods - Snack seasonings - Nutraceutical blends | - High-value functional foods - Nutraceutical tablets - Space or military rations - Medical nutrition products |

| Product Appearance | Fine, spherical particles; moderate solubility | Porous, sponge-like matrix; high solubility |

| Nutrient Retention | Moderate – susceptible to thermal degradation | High–preserves heat-sensitive compounds (vitamin C, polyphenols) |

| Glass Transition Temperature (Tg) Concerns | Low Tg due to sugar content can lead to stickiness and agglomeration during drying | Collapse risk if the product temperature exceeds Tg or ice melting onset temperature during drying |

| Caking Risk | High, especially without carriers; stickiness on dryer walls; yield loss | Moderate to high if stored improperly; porous structure may reabsorb moisture easily |

| Carrier Agent Use | Essential (e.g., maltodextrin, gum arabic, WPI) to raise Tg and improve flow | Optional but useful to increase Tg and reduce collapse during drying |

| Thermal Sensitivity | Exposes product to high inlet temperatures (150–200 °C) | Operates at low temperatures under vacuum; better for heat-sensitive ingredients |

| Particle Size & Flowability | Poor flow due to electrostatic behavior; risk of wide PSD without optimization | Poor flow due to low bulk density, highly hygroscopic, crystallization |

| Water Sorption Behavior | Needs monitoring; higher water activity increases stickiness and agglomeration | Very low initial moisture; but highly hygroscopic post-processing |

| Energy and Cost | Economical, fast, scalable | Expensive, energy-intensive, slower throughput |

| Equipment Requirements | Atomizer, hot air generator, cyclone separator | Vacuum chamber, condenser, refrigeration and heating systems |

| Packaging Needs | Moisture barrier packaging required | High-barrier packaging mandatory due to porous, hygroscopic structure |

| Suitability for Tablet Compaction | Moderate–better if flow and compression properties are adjusted with carriers | Excellent, porous matrix allows fast dispersion and rehydration |

| Challenges | - Stickiness - Wall deposits - Thermal degradation - Low Tg | - Collapse during drying - Poor flow - High cost |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Preciado Ocampo, V.; Yepes Hernandez, A.L.; Marratte, R.; Baena, Y.; Gutiérrez-López, G.F.; Ambrose, K.; Carvajal, M.T. Effect of Drying Methods on the Physical and Surface Properties of Blueberry and Strawberry Fruit Powders: A Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13094. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413094

Preciado Ocampo V, Yepes Hernandez AL, Marratte R, Baena Y, Gutiérrez-López GF, Ambrose K, Carvajal MT. Effect of Drying Methods on the Physical and Surface Properties of Blueberry and Strawberry Fruit Powders: A Review. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13094. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413094

Chicago/Turabian StylePreciado Ocampo, V., A. L. Yepes Hernandez, R. Marratte, Y. Baena, G. F. Gutiérrez-López, K. Ambrose, and M. T. Carvajal. 2025. "Effect of Drying Methods on the Physical and Surface Properties of Blueberry and Strawberry Fruit Powders: A Review" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13094. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413094

APA StylePreciado Ocampo, V., Yepes Hernandez, A. L., Marratte, R., Baena, Y., Gutiérrez-López, G. F., Ambrose, K., & Carvajal, M. T. (2025). Effect of Drying Methods on the Physical and Surface Properties of Blueberry and Strawberry Fruit Powders: A Review. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13094. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413094