1. Introduction

Eagle Syndrome (ES), first described by Watt W. Eagle in 1937, is a rare pathological condition characterized by the elongation or calcification of the styloid process and/or the stylohyoid ligament [

1]. This syndrome can manifest with a variety of symptoms, including oropharyngeal pain, dysphagia, and a sensation of a foreign body in the throat. Traditionally, ES is classified into two main clinical variants: the classic (or styloid) type, primarily associated with mechanical irritation of adjacent nerves or muscles, and the vascular variant, which involves compression of nearby blood vessels. ES is further subdivided into two vascular subtypes based on the affected vessel: the jugular variant (involving compression of the internal jugular vein) and the carotid variant (involving compression of the internal carotid artery, ICA). The carotid variant is of particular clinical interest in this study, as ICA compression may lead to neurological and cerebrovascular symptoms, including transient ischemic attacks or stroke [

2,

3].

Epidemiologically, an elongated styloid process is a relatively common anatomical finding, present in approximately 4% of the general population. However, the condition remains asymptomatic in the vast majority of cases, with true symptomatic Eagle Syndrome estimated to occur in only roughly 0.16% of the population.

The diagnosis of ES is primarily based on clinical evaluation and imaging studies. Clinically, patients often present with localized pain in the oropharyngeal region, which may be exacerbated by palpation of the tonsillar fossa or head movements. Imaging plays a crucial role in confirming the diagnosis, with computed tomography (CT) being the gold standard due to its ability to visualize the elongated styloid process or calcified stylohyoid ligament and assess its relationship with adjacent structures. Three-dimensional (3D) reconstructions from CT scans can further aid in surgical planning, particularly in cases involving vascular compression. Additionally, panoramic radiography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to complement the diagnostic process, especially when evaluating soft tissue involvement or vascular compression [

4].

The internal carotid artery is one of the major blood vessels supplying blood to the brain. It originates from the common carotid artery and ascends through the neck, entering the skull to supply the anterior and middle cerebral structures. Its course through the neck often presents anatomical variants, including tortuosity, kinking, and looping, which can affect blood flow and vessel wall susceptibility to external compression [

5,

6]. Vascular Eagle Syndrome is characterized by the compression of blood vessels, particularly the ICA, by an elongated or calcified styloid process [

7]. Despite this, the current clinical focus remains largely on styloid process length, neglecting the critical role of the ICA’s pre-existing morphology [

8]. This compression could be severely exacerbated by anatomical variants of the ICA, such as tortuosity or kinking, creating a complex stylo-vascular conflict where risk is determined not by one factor, but by the adverse combination.

The aim of this observational retrospective study was to investigate the role of specific Internal Carotid Artery anatomical variants (tortuosity, kinking, and looping) in the pathophysiology of vascular Eagle Syndrome and to compare their association with symptom severity and the CHA2DS2-VASc thromboembolic risk score against the influence of absolute styloid process length.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Population

We conducted an observational retrospective study on patients diagnosed with vascular Eagle syndrome referred to the Maxillofacial Surgery Unit of A.O.U. Policlinic “G. Martino” in Messina, Italy. The procedures were in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration; the study was approved by the local ethics committee (prot. N°116-24, 23 April 2024). The reporting of this observational retrospective study adheres to the guidelines outlined in the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement.

Patients’ data were selected from 2019 to 2024. Inclusion criteria were confirmed diagnosis of vascular Eagle syndrome, and availability of clinical and radiological data, specifically of Computed Tomography Angiography (CTA) images.

The data collected included age, sex, pathologic history, clinical symptoms, styloid process length, and ICA anatomic variations. Thromboembolic risk was assessed using CHA

2DS

2-VASc score [

9]. The CHA

2DS

2-VASc score is a validated clinical prediction rule originally developed for estimating stroke risk in patients with non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation. The acronym stands for Congestive heart failure (1 point), Hypertension (1 point), Age ≥ 75 years (2 points), Diabetes mellitus (1 point), Stroke/TIA/thromboembolism history (2 points), Vascular disease (prior myocardial infarction, peripheral artery disease, or aortic plaque) (1 point), Age 65–74 years (1 point), and Sex category (female gender) (1 point). A cumulative score is calculated for each patient, ranging from 0 to 9, with higher scores indicating a greater estimated annual risk of thromboembolic events.

Symptom severity was categorized in 3 levels: Low (e.g., pain, vertigo, dysphagia, etc.), Mid (e.g., Transitory facial paresis, lipothymia, blurry vision, etc.), High (e.g., Stroke, TIA, carotid artery dissection, etc.).

2.2. Imaging Protocols

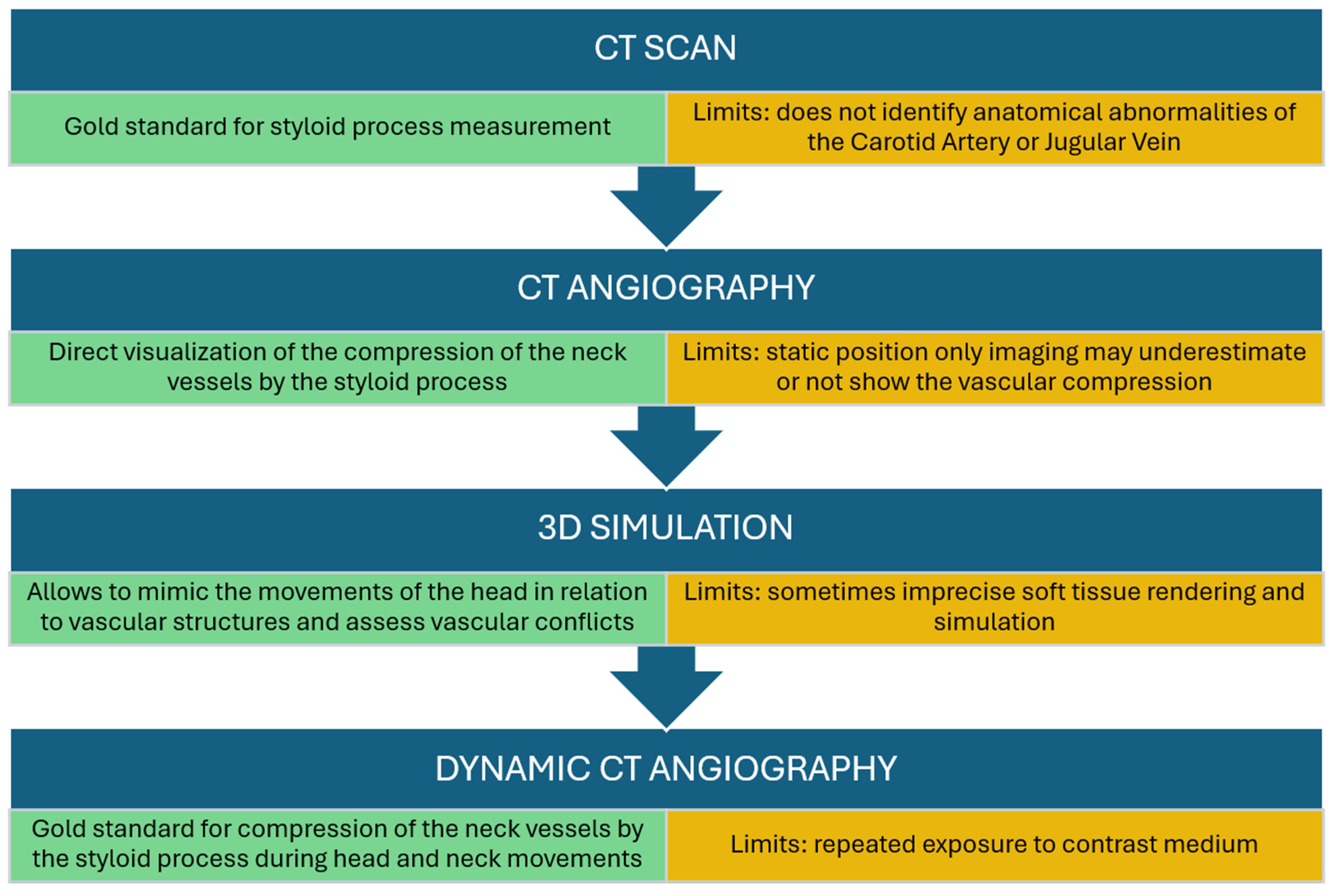

Eagle syndrome was diagnosed according to the workflow described in

Figure 1 and detailed in previous research [

10].

The CTA images were independently analyzed by a radiologist and two maxillofacial surgeons and data were confirmed by consensus. The images were used to identify the length of the styloid process, the presence of calcifications, and the anatomical variations of the ICA. Specifically, tortuosity was defined as a serpentine course of the artery, kinking as an acute curve with an angle of at least 90 degrees, and looping as a circular or ring-like artery configuration. To minimize interpretation bias, the reviewers were blinded to the patients’ CHA2DS2-VASc scores. The anatomical evaluation of the Internal Carotid Artery (ICA) and its spatial relationship with the styloid process was performed using Computed Tomography Angiography (CTA) with multiplanar and 3D volume-rendering reconstructions. This modality was selected for its ability to visualize the bony-vascular conflict and to allow the computer-assisted simulation of head and neck movements. In this study, “flow impairment” was defined radiologically based on the presence of significant vessel stenosis, kinking (acute angulation), or coiling observed on static imaging, rather than through dynamic hemodynamic measurements.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). The following variables were analyzed: age, sex, left and right ICA anatomy, left and right styloid bone length, symptom/pathology caused, symptom severity, CHA2DS2-VASc score.

p values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

To investigate potential relationships among the variables, Spearman’s rank correlation was employed to analyze the correlation between styloid bone length and both symptom severity and the CHA2DS2-VASc score.

The chi-squared test was used to assess the association between the anatomical variant of the ICA on the affected side and both symptom severity and the CHA2DS2-VASc score. Fisher’s exact test was also used to analyze the relationship between the ICA anatomical variant on the affected side and the CHA2DS2-VASc score.

Regression models were not used to avoid overfitting, given the limited sample size and the lack of significant correlations observed in the preliminary analyses.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

Out of 51 patients initially diagnosed with vascular Eagle syndrome, 9 patients were excluded due to unretrievable radiological images and/or missing clinical information, and 5 patients were excluded due to a diagnosis of neuropathic Eagle syndrome. A total of 37 patients were ultimately included in the analysis.

The study cohort comprised 16 males and 21 females. The mean age was 49 ± 11 years, with a range of 23 to 72 years. The affected side was recorded as left in 15 patients (40.5%), right in 8 patients (21.6%), and bilateral in 14 patients (37.8%).

Mean styloid bone length was 40 ± 16 mm (range: 10–90 mm) on the left side and 38 ± 9 (range: 20–65 mm) on the right side.

Patients reported a heterogeneous array of primary symptoms and resulting pathologies, which are detailed in

Table 1.

Symptom severity was distributed as follows: 56.8% low severity, 10.8% mid severity, and 32.4% high severity. The most frequent symptom or pathology recorded was strokes, followed by facial pain and Temporomandibular Joint pain.

3.2. Anatomical Variations of the ICA

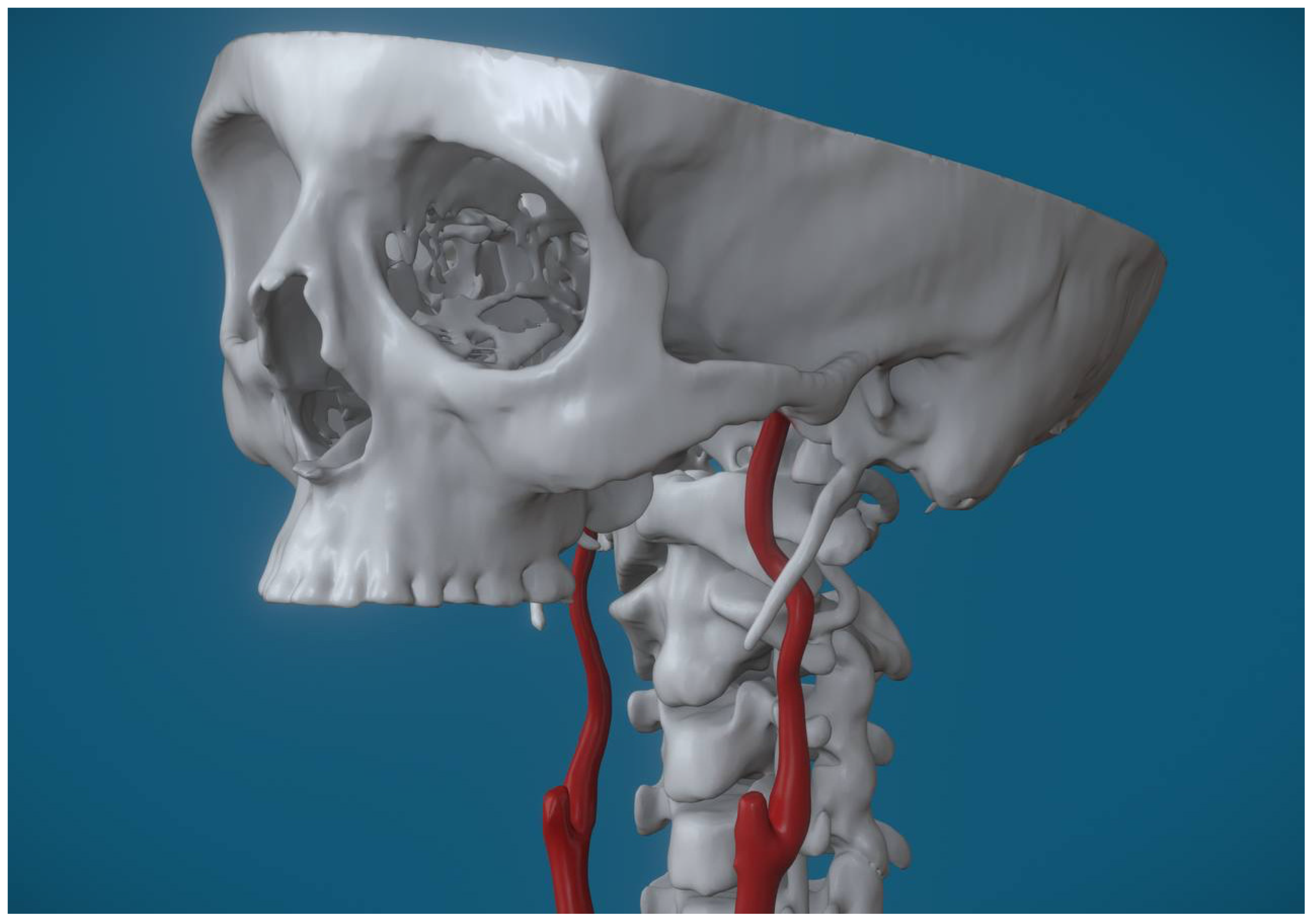

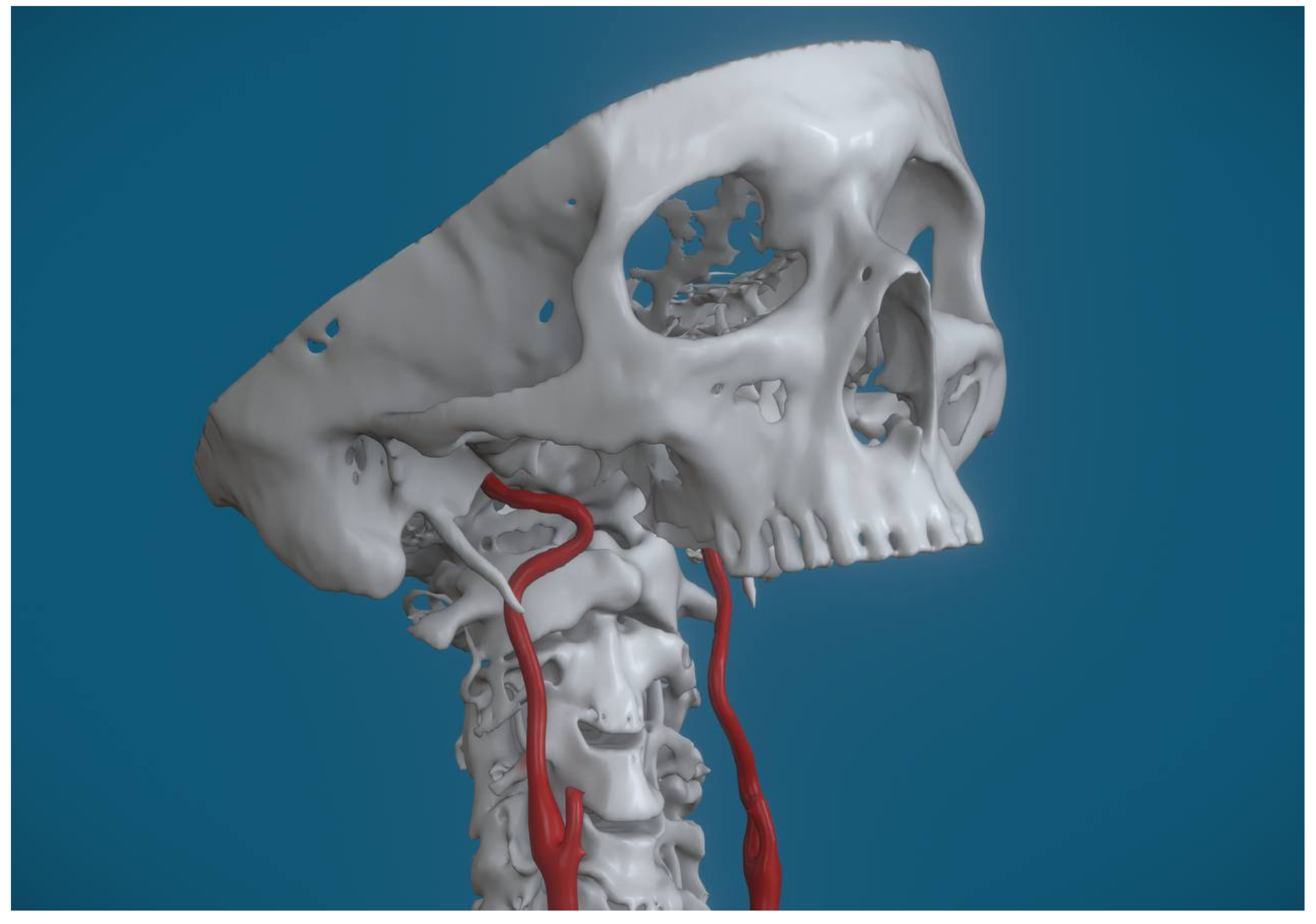

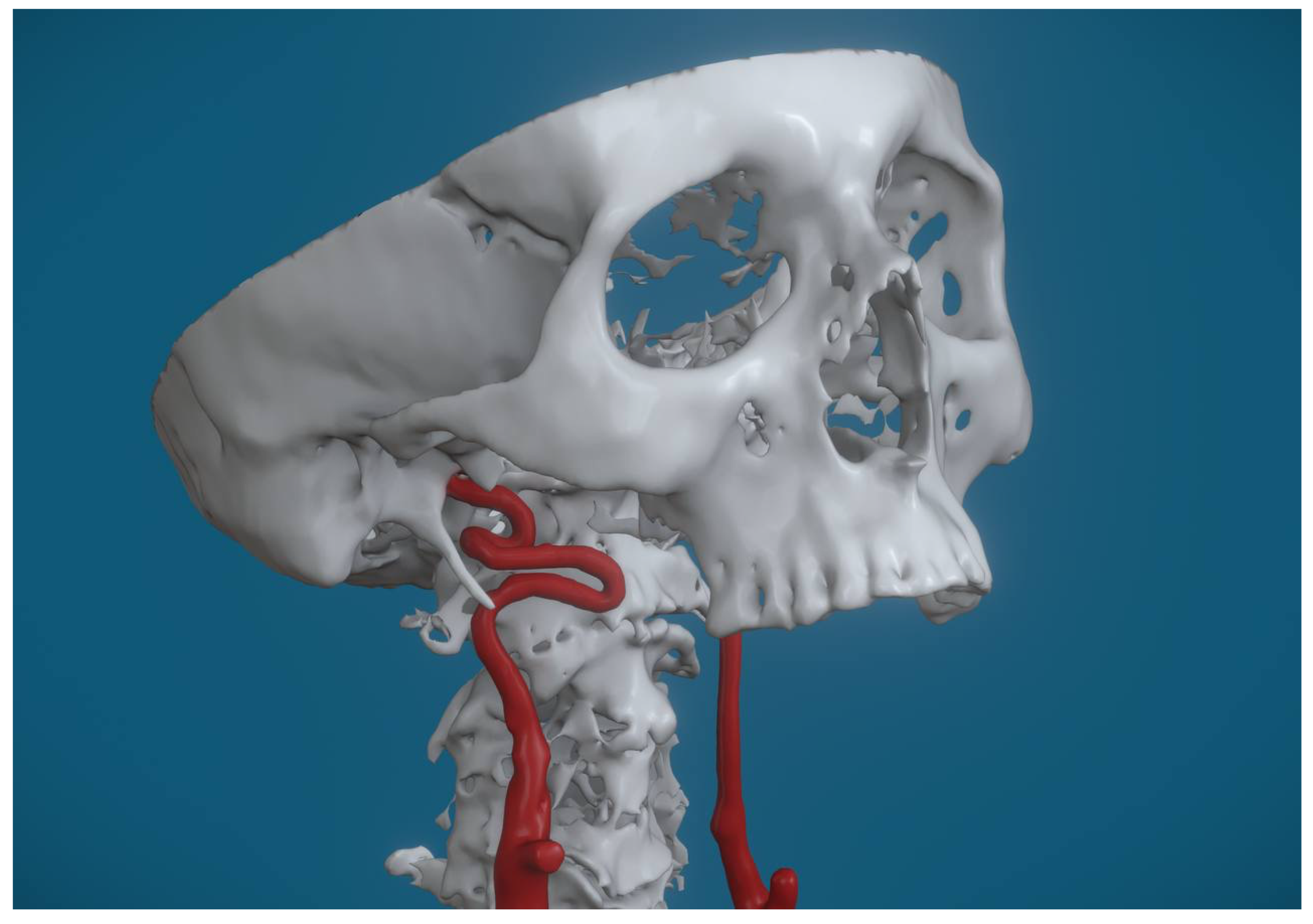

Anatomical variations were observed in 96% of the examined carotid arteries. Specifically, considering both ICAs for each patient, tortuosity was the most frequent anomaly, observed in 46 cases (62%) [

Figure 2], followed by looping, which was present in 20 cases (27%) [

Figure 3], and kinking, identified in 5 cases (7%) [

Figure 4].

When focusing only on the ICA of the affected side (or the side with the strongest symptom in bilateral cases), tortuosity was identified in 21 cases (56.8%), looping in 13 cases (35.1%), and kinking in 3 cases (8.1%).

3.3. Thromboembolic Risk Assessment

The clinical characteristics of the cohort are summarized in

Table 2 via the CHA

2DS

2-VASc score distribution. Since this scoring system is a composite of hypertension, diabetes, heart failure, and vascular history, the table reflects the cumulative cardiovascular burden of the study population.

A Spearman’s rank-order correlation was run to determine the relationship between styloid bone length and both symptom severity and CHA2DS2-VASc score. No correlation was found for either variable (p = 0.807), (p = 0.739).

No statistically significant association was found between the ICA anatomical variant of the affected side and symptom severity (Χ2(4) = 0.991, p = 0.911).

Regarding the association between the ICA anatomical variant and CHA2DS2-VASc score, the assumptions for the Chi-squared test for independence were not adequately met due to the small sample size and low expected cell counts (86.7% with expected counts < 5). Therefore, Fisher’s exact test was performed to assess this relationship. This analysis yielded a statistically significant association between the ICA anatomical variant and CHA2DS2-VASc (Fisher’s exact test statistic = 14.397, p = 0.024).

4. Discussion

4.1. Anatomical Implications

The presence of anatomical variations of the ICA, such as tortuosity, kinking, and looping, adds a layer of complexity to the diagnosis and management of vascular Eagle syndrome. These variations, observed in virtually every patient in our cohort, appear to play a significant role in determining clinical outcomes.

A direct comparative analysis between patients with and without ICA anatomical variants was not statistically possible because 96% of all examined arteries exhibited some form of variation. This overwhelming prevalence is noteworthy and mandated that our analysis focuses instead on the type of variation (tortuosity, looping, kinking) rather than the simple presence or absence of an anomaly.

Our analysis revealed a statistically significant association between the ICA anatomical variant type and the CHA2DS2-VASc score (Fisher’s exact test statistic p = 0.024). This finding is critical, as it suggests the specific morphology of the carotid artery wall and lumen, rather than the styloid length alone, may influence a patient’s risk profile for thromboembolic events.

The internal carotid artery (ICA) can present with several anatomical variations that may predispose it to compression or other complications [

11,

12]. The high prevalence of ICA anomalies observed in our cohort (96%) necessitates a clear understanding of their morphology.

One such variation is tortuosity, where the artery exhibits abnormal curvatures along its course. This condition can be either congenital or acquired and often renders the artery more susceptible to external compression, particularly in the presence of an elongated styloid process.

Another notable variation is kinking, which involves an acute angulation of the ICA. This sharp bending can compromise blood flow and increase the risk of vascular compression, especially in cases where the styloid process impinges on the artery.

Lastly, looping refers to the formation of complete loops or rings in the ICA. These loops create points of increased mechanical stress and can lead to disturbances in blood flow, further exacerbating the risk of compression-related symptoms.

Anatomical variations of the ICA can also be classified based on potential clinical impact:

Type I: Mild tortuosity without significant impairment of blood flow.

Type II: Moderate tortuosity with increased risk of compression in the presence of nearby anatomical structures, such as an elongated styloid process.

Type III: Pronounced kinking or looping causing significant impairment of blood flow and clinical symptoms.

When the ICA is tortuous, its ability to resist external compression decreases, making the onset of cerebrovascular symptoms more likely [

13,

14]. Compression of ICA can lead to a reduction in blood flow to the brain, causing symptoms such as dizziness, headaches, and even transient ischemia or transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), and in severe cases, complete cerebral ischemia may occur [

15,

16].

4.2. Clinical Relevance and Thromboembolic Risk

Recent studies suggest that anatomical variations of the ICA, such as vessel tortuosity, may predispose patients to more severe manifestations of vascular ES [

13,

15]. These structural irregularities, which include abnormal curvatures (tortuosity), sharp angulations (kinking), or complete loops (looping), increase mechanical stress on the arterial wall and reduce its resilience to external compression. When combined with the pressure exerted by an elongated or calcified styloid process, a hallmark of Eagle Syndrome, these variations can exacerbate vascular compromise. For instance, tortuous segments of the ICA are more prone to localized damage or dissection when compressed, while kinked regions may experience critical reductions in blood flow.

Clinical evidence from case series and imaging studies further supports this relationship: patients with preexisting ICA abnormalities who develop vascular ES are at higher risk of cerebrovascular complications, such as transient ischemic attacks, strokes, or carotid dissections [

13,

14,

15,

17]. A physiologically normal, straight ICA possesses greater anatomical clearance and mechanical resilience, allowing it to evade compression even in the presence of an elongated styloid process. In contrast, anatomical variations such as kinking or tortuosity are likely to reduce the vessel’s compliance and alter its spatial trajectory, making it significantly more susceptible to mechanical impingement. This hypothesis aligns with our observation of a high prevalence of ICA anomalies in symptomatic patients, reinforcing the concept that vascular morphology is a critical determinant in the development of the syndrome. This underscores the importance of evaluating ICA anatomy in suspected vascular ES cases to stratify clinical risk and guide management.

We considered the potential confounding effect of age, as advanced age is associated with both higher CHA2DS2-VASc scores and increased vascular tortuosity. However, the mean age of our cohort was 49 ± 11 years, which is significantly below the 65-year threshold where the scoring system begins to assign points for age. Consequently, the risk stratification in this study was predominantly driven by specific comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) rather than age itself.

While this result suggests a relationship within our study sample, it does not underline a causal link. The interpretation should be cautious given the limited sample size, and further research with a larger cohort is warranted to confirm these findings and explore the specific nature of the statistical association between different carotid artery variants and thromboembolic risk.

On the other hand, no statistically significant association was found between the ICA anatomical variant on the affected side and overall symptom severity. Furthermore, no correlation was found between the absolute length of the styloid process and either symptom severity or the CHA2DS2-VASc score.

This suggests that the elongation of the styloid process alone is not sufficient to cause severe vascular compression; rather, it is the interplay between the styloid process and preexisting ICA variations that drives the pathophysiology of vascular Eagle syndrome.

This aligns with findings from Baldino et al., who reported that ICA tortuosity and kinking were associated with a higher risk of cerebrovascular complications in patients with vascular Eagle syndrome [

15]. Similarly, Tardivo et al. highlighted that anatomical variations of the ICA, rather than the absolute length of the styloid process, are critical determinants of vascular compression and its clinical consequences [

14]. Our observation is consistent with the work of Cruddas et al., who demonstrated that ICA tortuosity increases mechanical stress on the arterial wall, making it more susceptible to compression even by a moderately elongated styloid process [

13].

4.3. Therapeutic Considerations

Therapeutic decision-making in vascular Eagle syndrome must account for these anatomical variations. While surgical removal of the elongated styloid process remains the definitive treatment for relieving mechanical compression, the presence of ICA anomalies, particularly given the significant association with the CHA2DS2-VASc score, often tilts the balance toward aggressive intervention.

Preoperative imaging and planning become even more critical in these cases to avoid intraoperative complications and ensure optimal outcomes. Conservative management may be considered for patients with mild symptoms or those who are not surgical candidates, but the elevated risk indicated by the ICA variant association supports a prompt and careful consideration of surgical options.

Although this study focused on diagnostic imaging, the identification of ICA variants has profound surgical implications. Styloidectomy, performed via either a transoral or transcervical approach, remains the definitive treatment for refractory Eagle Syndrome. The presence of high-risk ICA anomalies, such as kinking or looping near the tonsillar fossa, mandates a meticulous preoperative assessment to prevent catastrophic intraoperative hemorrhage. In cases with significant vascular compromise, a transcervical approach may be favored over the transoral route to ensure adequate vascular control.

Moreover, we strongly advocate the need for future research that employs dynamic imaging protocols (e.g., studying patients in different head or neck positions) to better highlight the stylo-vascular conflict. The results emphasize that it is the pathophysiological interplay between a potentially elongated styloid process and a pre-existing ICA anomaly that drives the risk of vascular complications. Integrating this detailed anatomical information into the diagnostic process could significantly improve patient management, allowing for a more targeted and personalized approach. A multidisciplinary approach, combining advanced static and dynamic imaging techniques with clinical risk assessment, is necessary to optimize the diagnosis and therapeutic strategy for this complex condition.

4.4. Limitations

Despite these insights, current studies on vascular Eagle syndrome, including ours, have notable limitations. Our primary limitation is the small sample size (N = 37) and retrospective study design, which restricts the statistical power and limits our ability to draw definitive, generalizable conclusions about the natural history of the syndrome or the long-term efficacy of therapeutic interventions. Many existing studies, including those by Baldino et al. and Tardivo et al., face similar constraints regarding small cohorts and a lack of long-term follow-up data [

14,

15].

We acknowledge that the CHA2DS2-VASc score is primarily validated for stroke risk stratification in atrial fibrillation. However, in the absence of a dedicated scoring system for vascular Eagle Syndrome, we utilized it as a surrogate marker to quantify the cumulative burden of cardiovascular comorbidities (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, vascular disease) in our cohort. Its application here serves to highlight the ‘vascular fragility’ of patients with symptomatic ICA compression, rather than to predict AFib-related stroke specifically. Future studies should aim to develop a risk model specific to carotid compression syndromes.

Our morphological assessment focused on absolute styloid length and direct vascular contact. We did not utilize the Langlais classification system, which categorizes the styloid process based on elongation and ossification patterns. Future multicentric studies should incorporate this validated classification to ensure broader comparability with the existing literature. Future research should prioritize longitudinal studies with larger cohorts to better elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the interaction between ICA variations and the styloid process morphology and position relative to the neck vessels, rather than merely the length. Additionally, advancements in imaging techniques, such as high-resolution CT angiography and 3D reconstructions, could improve the accuracy of diagnosing ICA anomalies and guide more precise surgical planning.

Our findings underscore the importance of considering ICA anatomical variations in the clinical evaluation of patients with vascular Eagle syndrome. By integrating these insights into diagnostic and therapeutic protocols, clinicians can improve patient outcomes and reduce the risk of severe cerebrovascular complications.