Blood Lactate Dynamics Reveal Distance-Specific Anaerobic Demands in 400 m Sprint Training

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Subjects

2.2. Procedure

2.3. Anthropometric Measurements

2.4. Special Endurance Trial Warm-Up

2.5. Blood Lactate Concentration Measurement

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Strengths and Limitations

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Yamamoto, K. Analysis of the major men and women’s 400 m races of 2015. Bull. Stud. Athl. JAAF 2015, 11, 128–135. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, K. Analysis of the major men and women’s 400 m races of 2016. Bull. Stud. Athl. JAAF 2016, 12, 98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Iskra, J.; Zajac, A.; Maćkała, K.; Paruzej-Dyja, M. High-Performance Sprint Training: Polish Experiences; The Jerzy Kukuczka Academy of Physical Education: Katowice, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Nummela, A.; Vuorimaa, T.; Rusko, H. Changes in force production, blood lactate and EMG activity in the 400-m sprint. J. Sports Sci. 1992, 10, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weyand, P.; Cureton, K.; Conley, D.; Sloniger, M. Percentage anaerobic energy utilized during track running events. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 1993, 25, S-105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plevnik, M.; Vučetić, V.; Sporiš, G.; Fiorentini, F.; Milanović, Z.; Miškulin, M. Physiological responses in male and female 400 m sprinters. Croat. J. Educ. 2013, 15, 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen, J.; Nummela, A.; Rusko, H.K.; Harkonen, M. Fatigue and changes of ATP, creatine phosphate, and lactate during the 400-m sprint. Can. J. Sport Sci. 1992, 17, 141–144. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, J.-j.; Qin, Z.; Wang, P.-y.; Sun, Y.; Liu, X. Muscle fatigue: General understanding and treatment. Exp. Mol. Med. 2017, 49, e384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, M.; Debold, E.P. Acidosis and phosphate directly reduce myosin’s force-generating capacity through distinct molecular mechanisms. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, A.; Megido-Ravid, M.; Itzchak, Y.; Arcan, M. Analysis of muscular fatigue and foot stability during high-heeled gait. Gait Posture 2002, 15, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousif, H.A.; Norasmadi, A.R.; Bin Salleh, A.F.; Zakaria, A.; Alfarhan, K.A. Assessment of muscles fatigue during 400-Meters running strategies based on the surface EMG signals. J. Biomim. Biomater. Biomed. Eng. 2019, 42, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enoka, R.M.; Duchateau, J. Muscle fatigue: What, why and how it influences muscle function. J. Physiol. 2008, 586, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vazel, P.J. Speed Reserve in the 400 m. Special Report. p. 16. Available online: https://web2.ustfccca.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/Tommy-Badon.pdf (accessed on 12 May 2020).

- Gorostiaga, E.M.; Asiáin, X.; Izquierdo, M.; Postigo, A.; Aguad, R.; Alonso, J.M.; Ibáñez, J. Vertical jump performance and blood ammonia and lactate levels during typical training sessions in elite 400-m runners. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 138–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffield, R.; Dawson, B.; Goodman, C. Energy system contribution to 400 m and 800 m track running. J. Sports Sci. 2005, 23, 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spencer, M.R.; Gastin, P.B. Energy system contribution during 200- to 1500-m running in highly trained athletes. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2001, 33, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zouhal, H.; Jabbour, G.; Jacob, C. Anaerobic and aerobic energy system contribution to 400-m flat and 400-m hurdles track running. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2010, 24, 2309–2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newsholme, E.A.; Blomstrand, E.; Ekblom, B. Physical and mental fatigue: Metabolic mechanisms and importance of plasma amino acids. Br. Med. Bull. 1992, 48, 477–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanon, C.; Lepretre, P.M.; Bishop, D.; Thomas, C. Oxygen uptake and blood metabolic responses to a 400 m run. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 109, 233–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schäffer, W. On Structure Characteristics of the Competitive Performance and the Corresponding Training Content in the Athletics Discipline 400 m Long Sprint. Ph.D. Thesis, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Halle, Germany, 1989; 262p. (In German). [Google Scholar]

- Hirvonen, J.; Rehumen, S.; Rusko, M.; Harkonen, M. Breakdown of high energy phosphate compounds and lactate accumulation during short supramaximal exercise. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 1987, 56, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmatlan-Gabryś, U.; Ozimek, M.; Klimek, A.; Gorner, K. Profile of Aerobic and Anaerobic Efficiency of Professional Polish Road Cyclists After Winter Preparatory Period; Annale Universitath Din Oradea, Fascicula Educatie Fizica Si Sport Editura Universitath Din Oradea: Oradea, Romania, 2005; pp. 404–414. [Google Scholar]

- Hermansen, L. Effect of metabolic changes on force generation in skeletal muscle during maximal exercise. Hum. Muscle Fatigue Physological Mech. 1981, 82, 75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Hermansen, L.; Stensvold, I. Production and removal of lactate during exercise in man. Acta Physiol. Scand. 1972, 86, 191–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bret, C.; Lacour, J.R.; Bourdin, M.; Locatelli, E.; De Angelis, M. Differences in lactate exchange and removal abilities between high-level African and Caucasian 400 m track runners. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 113, 1489–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saraslanidis, P.J.; Panoutsakopoulos, V.; Tsalis, G.A.; Kyprianou, E. The effect of different first 200 m pacing strategies on blood lactate and biomechanical parameters of the 400 m sprint. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 111, 1579–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, V.M.; Duarte, J.A.; Espírito-Santo, J.; Russell, A.P. Determination of accumulated oxygen deficit during a 400 m run. J. Exerc. Physiol. 2004, 7, 77–83. [Google Scholar]

- Nummela, A.; Rusko, H. Time course of anaerobic and aerobic energy expenditure during short term exhaustive running in athletes. Int. J. Sports Med. 1995, 16, 522–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohkuwa, T.; Kato, Y.; Katsumata, K.; Nakao, T.; Miyamure, M. Blood lactate and glycerol after 400 m and 3000 m runs in sprint and long distance runner. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. Occup. Physiol. 1984, 53, 213–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grgić, D.; Babić, V.; Blazević, I. Running’s dynamic in male 400 m sprint event. Hum. Kinet. 2019, 12, 44–52. [Google Scholar]

- Duffield, R.; Dawson, B. Energy system contribution in track running. New Stud. Athl. 2003, 18, 47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Harman, C.H. A biomechanical power model for world-class 400 meter running. In Proceedings of the Sixth Australian Conference on Mathematics and Computers in Sport, Gold Coast, QLD, Australia, 1–3 July 2002; de Mestre, N., Ed.; Bond University: Robina, QLD, Australia, 2002; pp. 155–166. [Google Scholar]

- Lacour, J.R.; Bouvat, E.; Barthhelemy, J.C. Post-competition blood lactate concentration as indicators of anaerobic energy expenditure during 400 m and 800 m races. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 1990, 61, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, M.R.; Gastin, P.B.; Payne, W.R. Energy system contribution during 400 to 1500 m running. New Stud. Athl. 1996, 11, 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hanon, C.; Thomas, C. Effects of optimal pacing strategies for 400-, 800-, and 1500-m races on the V_O2 response. J. Sports Sci. 2011, 29, 905–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcelli, E.; Mambretti, M.; Cimadoro, G.; Alberti, G. The Aerobic mechanism in the 400 m. New Stud. Athl. 2008, 2, 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Vilmi, N.; Äyrämö, S.; Nummela, A. Oxygen uptake, acid-base balance and anaerobic energy system contribution in maximal 300–400 m running in child adolescent and adult athletes. J. Athl. Enhanc. 2016, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffield, R.; Dawson, B.; Coodman, C. Energy system contribution to 100-m and 200-m track running events. J. Sci. Med. Sport. 2004, 7, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Goswami, A.; Mukhopadhayay, S. Heart rate and blood lactate in 400 m flat and 400 m hurdles running: A comparative study. Ind. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1999, 43, 361–366. [Google Scholar]

- Cairns, S.P. Lactic acid and exercise performance. Culprit or Friend? Sports Med. 2006, 36, 279–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McNaughton, L.R.; Siegler, J.; Midgley, A. Ergogenic effects of sodium bicarbonate. Curr. Sports Med. Rep. 2008, 7, 230–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebisz, R.; Hebisz, P.; Borkowski, J.; Zatoń, M. Differences in physiological responses to interval training in cyclists with and without interval training experience. J. Hum. Kinet. 2016, 50, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameters | Group 350 m, n = 6 | Group 500 m, n = 5 | Student’s t-Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | SD | t | p | |||

| Age (years) | 25.33 | 3.83 | 23.80 | 3.70 | 0.67 | 0.5190 |

| Personal best 400 m (s) | 46.09 | 0.77 | 46.63 | 1.15 | −0.30 | 0.7705 |

| Body mass (kg) | 78.35 | 7.62 | 79.50 | 6.37 | −0.62 | 0.5486 |

| Body height (cm) | 184.92 | 7.20 | 187.50 | 2.23 | 0.18 | 0.8647 |

| Parameter | Group 350 m, n = 6 | Group 500 m, n = 5 | Student’s t-Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | SD | t | p | |||

| Time (s) | 40.98 | 0.73 | 64.63 | 1.21 | −40.17 | 0.0000 |

| Step length (cm) | 223.08 | 8.34 | 221.85 | 14.46 | 0.18 | 0.8637 |

| Step frequency (Hz) | 4.00 | 0.12 | 3.55 | 0.18 | 4.99 | 0.0007 |

| Velocity (m/s) | 8.90 | 0.15 | 8.02 | 0.67 | 3.12 | 0.0123 |

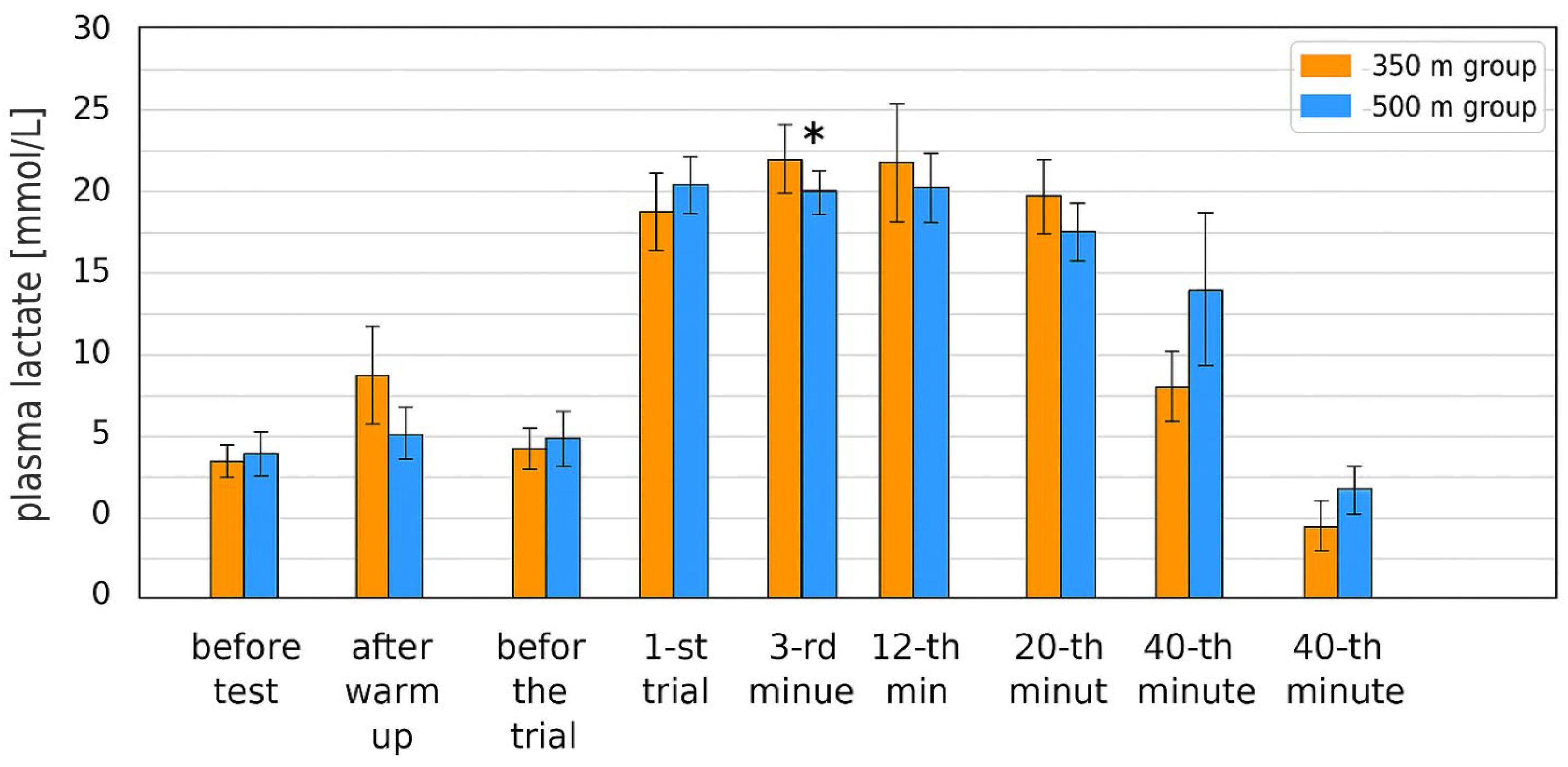

| Measurement | Group 350 m, n = 6 | Group 500 m, n = 5 | Student’s t-Test | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SD | SD | t | p | |||

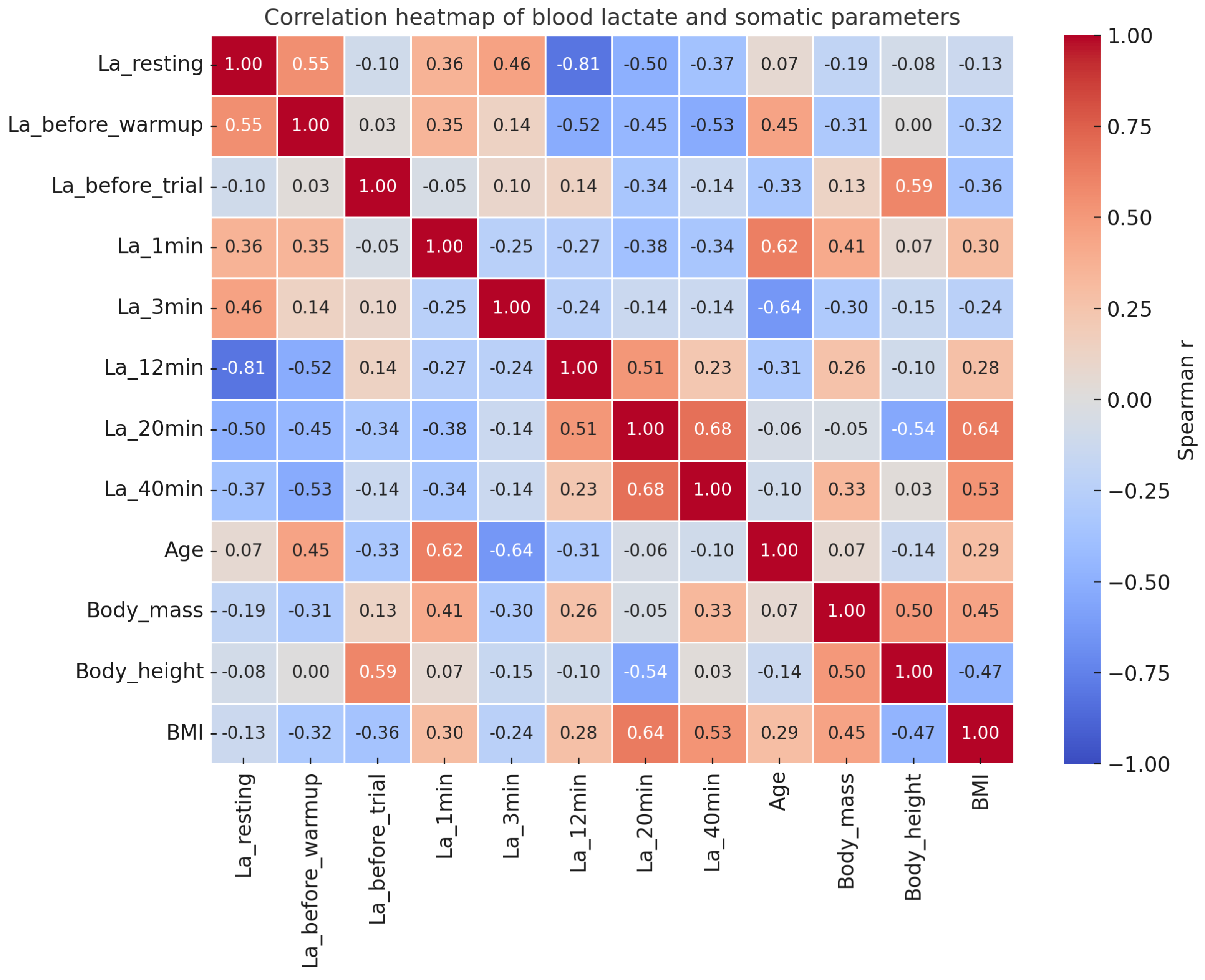

| La resting (mmol/L) | 1.64 | 0.54 | 2.03 | 0.37 | −1.38 | 0.2013 |

| La before warm-up (mmol/L) | 6.03 | 1.66 | 6.29 | 3.37 | −0.17 | 0.8683 |

| La before the trial (mmol/L) | 2.90 | 0.40 | 3.78 | 1.32 | −1.57 | 0.1513 |

| La 1 min after trial (mmol/L) | 18.04 | 2.56 | 20.10 | 0.31 | −1.78 | 0.1096 |

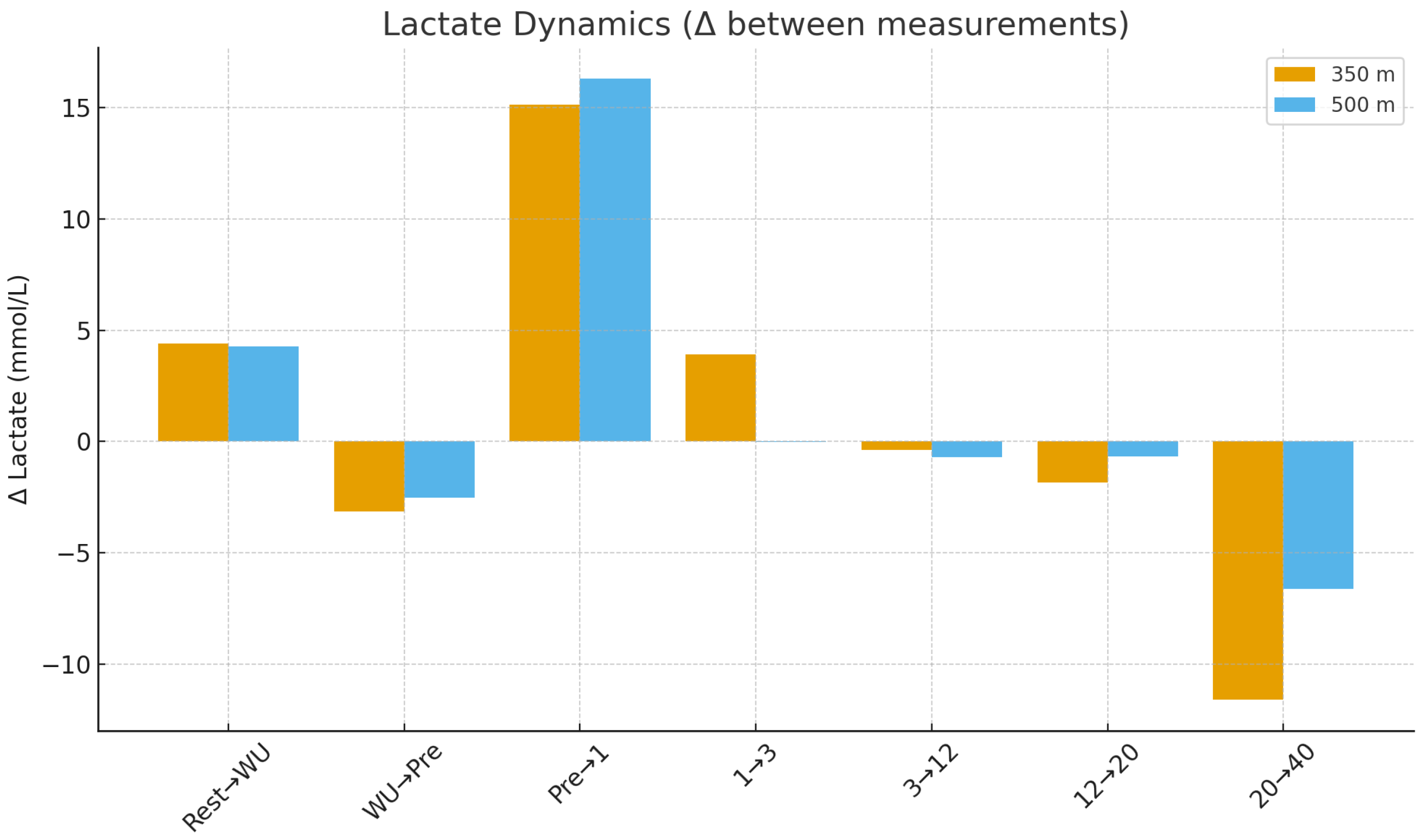

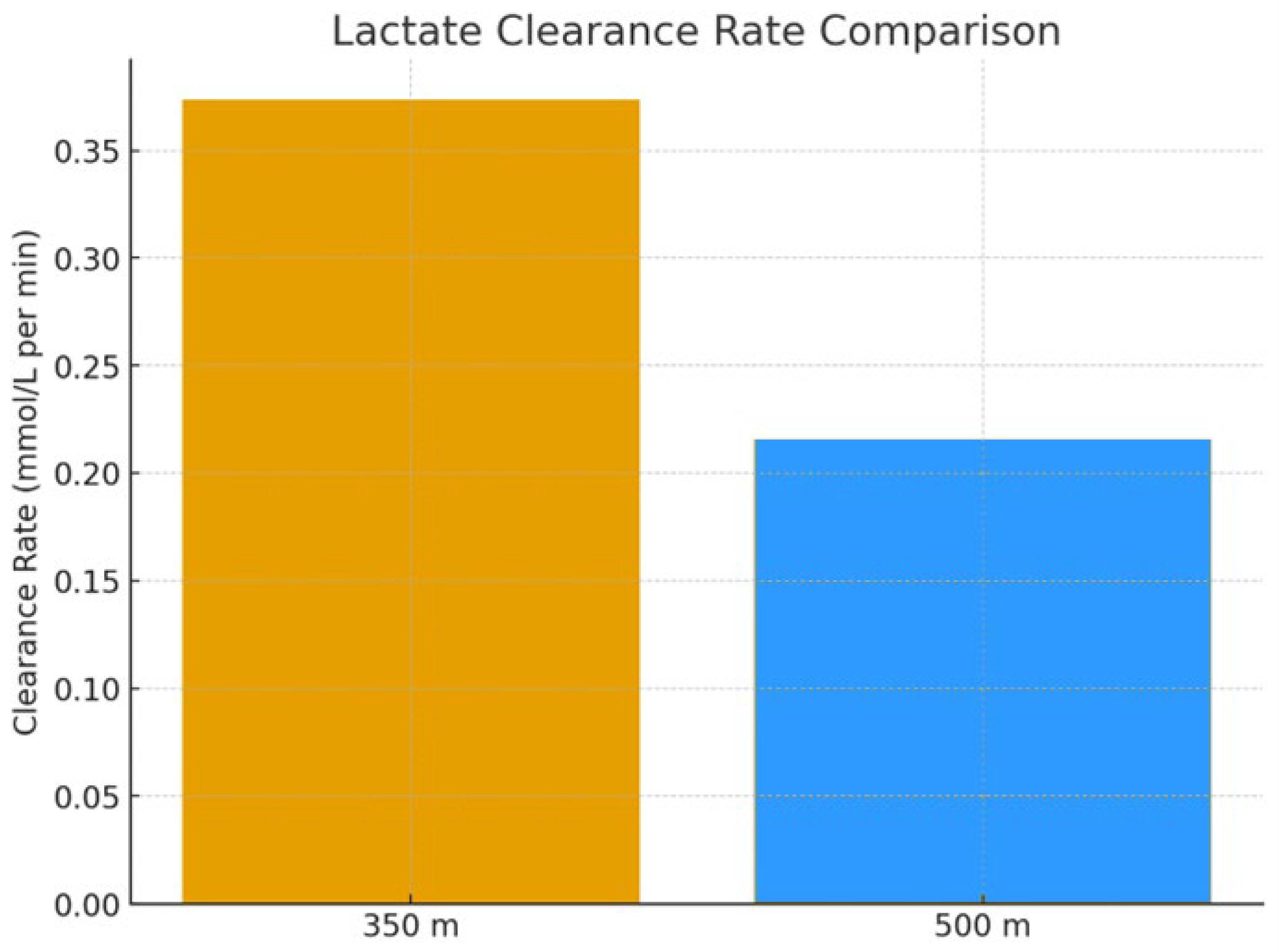

| La 3 min after trial (mmol/L) | 21.97 | 1.47 | 20.08 | 0.45 | 2.76 | 0.0223 |

| La 12 min after trial (mmol/L) | 21.59 | 2.94 | 19.37 | 0.78 | 1.63 | 0.1385 |

| La 20 min after trial (mmol/L) | 19.76 | 1.90 | 18.71 | 0.85 | 1.14 | 0.2845 |

| La 40 min after trial (mmol/L) | 8.15 | 2.20 | 12.10 | 5.44 | −1.64 | 0.1357 |

| Distance | Comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Δ1–Δ3 | Δ3–Δ12 | Δ12–Δ20 | Δ20–Δ40 | |

| 350 | 0.0000 | 0.0118 | 0.3015 | 0.0000 |

| 500 | 0.0000 | 0.7039 | 0.9929 | 0.0021 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Omelko, R.; Mroczek, D.; Jopek, M.; Mastalerz, A.; Mackala, K. Blood Lactate Dynamics Reveal Distance-Specific Anaerobic Demands in 400 m Sprint Training. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13051. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413051

Omelko R, Mroczek D, Jopek M, Mastalerz A, Mackala K. Blood Lactate Dynamics Reveal Distance-Specific Anaerobic Demands in 400 m Sprint Training. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13051. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413051

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmelko, Rafal, Dariusz Mroczek, Mateusz Jopek, Andrzej Mastalerz, and Krzysztof Mackala. 2025. "Blood Lactate Dynamics Reveal Distance-Specific Anaerobic Demands in 400 m Sprint Training" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13051. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413051

APA StyleOmelko, R., Mroczek, D., Jopek, M., Mastalerz, A., & Mackala, K. (2025). Blood Lactate Dynamics Reveal Distance-Specific Anaerobic Demands in 400 m Sprint Training. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13051. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413051