The Use of Sheep Wool Collected from Sheep Bred in the Kyrgyz Republic as a Component of Biodegradable Composite Material

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.1.1. Biopolymers Matrix PLA

2.1.2. Sheep Wool Fibres

- Fibre diameter (fineness): 24.5 ± 2.3 μm (n = 50 fibres, measured using optical microscopy),

- Fibre length: 40–80 mm (after shearing),

- Crimp frequency: 8–12 crimps/cm,

- Bulk density (raw wool): 0.25 ± 0.05 g/cm3,

- Moisture regain: 13.0–13.5% at 65% RH, 20 °C (ASTM D2654) [21].

- Protein content (keratin): 95–98% (by dry weight),

- Lipid content (lanolin): 10–15% (by weight of raw fibre),

- Ash content: 1–2%,

- Degradation temperature (Tdeg): 189–250 °C (based on DSC/TGA).

- Tensile strength: 100–200 MPa (dry fibre at 25 °C),

- Young’s modulus: 3–4 GPa,

- Compression at break: 25–35%.

2.2. Research Methods

2.2.1. Production of Biocomposite Samples

Detailed Thermoforming Process Description

- Pre-heating stage:

- -

- The mould plates were pre-heated to 160–165 °C for 10 min to ensure thermal equilibrium.

- -

- Temperature was monitored using K-type thermocouples (±1 °C accuracy).

- Sample preparation:

- -

- Wool fibres (previously cut to 10 mm length) were weighed to achieve exactly 50% mass ratio.

- -

- PLA solution (20% in DCM) was prepared at room temperature (23 ± 2 °C).

- -

- Wool fibres were mixed manually with PLA solution in a glass container for 2 min.

- -

- The mixture was spread uniformly in the mould cavity (dimensions: 200 mm × 200 mm × 20 mm depth).

- Thermoforming parameters:

- -

- Moulding temperature: 168 ± 2 °C (monitored continuously)

- -

- Applied pressure: 65 ± 5 N (constant during forming)

- -

- Forming time: 30 s under constant pressure

- -

- Cooling phase: 5 min under pressure at room temperature

- Post-processing:

- -

- Samples were removed from the mould after cooling to below 40 °C.

- -

- Edge trimming was performed using precision cutting tools.

- -

- Samples were cut to final dimensions: 80 mm (length) × 20 mm (width) × 4.2 mm (thickness).

- -

- All samples were dried at 60 °C for 24 h to remove residual DCM and moisture.

2.2.2. Quality Control and Sample Selection Criteria

- (a)

- Visual Inspection Criteria:

- Surface smoothness assessment (absence of deep voids, cracks, or delamination visible to naked eye),

- Colour uniformity check (acceptable range: uniform light tan to cream colour, indicating consistent processing),

- Dimensional verification (thickness uniformity ± 10%, width uniformity ± 5%).

- (b)

- Defect Classification and Rejection Criteria:

- Grade A (Acceptable): <5% void fraction visible at 20× magnification, smooth surface, uniform thickness,

- Grade B (Marginal): 5–15% void fraction, minor surface irregularities, acceptable thickness variation,

- Grade C (Reject): >15% void fraction, visible delamination, thickness variation > 10%, surface cracks.

- (c)

- Sample Selection Process:

- Initial production batch: 45 composite panels,

- After quality inspection: 38 panels met Grade A/B criteria (84% acceptance rate),

- Final selection for mechanical testing: 10 Grade A samples from different manufacturing dates (ensuring manufacturing reproducibility),

- Rejected samples (Grade C, n = 7) were not included in mechanical characterisation to ensure scientific rigor.

- Demonstrate the effectiveness of PLA encapsulation of wool fibres by detecting (or confirming absence of) moisture-related thermal transitions.

- Differentiate between free water (evaporating at ~100 °C) and bound water (requiring higher temperatures) in wool fibres.

- Assess the fibre–matrix interfacial quality through moisture accessibility.

2.2.3. Biodegradation Testing of Samples

3. Results and Discussion

Overview of Experimental Rigor and Methodology Validation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saba, N.; Awad, S.A.; Jawaid, M.; Hashem, M.; Fouad, H.; Uddin, I.; Singh, B. Mechanical Performance and Dimensional Stability of Washingtonia/Kenaf Fibres-Based Epoxy Hybrid Composites. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 24242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allafi, F.; Hossain, M.S.; Lalung, J.; Shaah, M.; Salehabadi, A.; Ahmad, M.I.; Shadi, A. Advancements in Applications of Natural Wool Fiber: Review. J. Nat. Fibers 2022, 19, 497–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alyousef, R.; Aldossari, K.; Ibrahim, O.; Al Jabr, H.; Alabduljabbar, H.; Mohamed, A.; Siddika, A. Effect of Sheep Wool Fiber on Fresh and Hardened Properties of Fiber Reinforced Concrete. Int. J. Civ. Eng. Technol. 2019, 10, 190–199. [Google Scholar]

- Szczecina, J.; Szczepanik, E.; Barwinek, J.; Szatkowski, P.; Niemiec, M.; Zhakypbekovich, A.I.; Molik, E. Sheep Wool as Biomass: Identifying the Material and Its Reclassification from Waste to Resource. Energies 2025, 18, 5185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardinale, T.; Arleo, G.; Bernardo, F.; Feo, A.; De Fazio, P. Thermal and Mechanical Characterization of Panels Made by Cement Mortar and Sheep’s Wool Fibres. Energy Procedia 2017, 140, 159–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folentarska, A.; Krystyjan, M.; Baranowska, H.M.; Ciesielski, W. Renewable Raw Materials as an Alternative to Receiving Biodegradable Materials. Chem. Environ. Biotechnol. 2016, 19, 121–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penczek, S.; Pretula, J.; Lewiński, P. Polymers from Renewable Resources. Biodegradable Polymers. Polimery 2013, 58, 835–846. [Google Scholar]

- Gołębiewski, J.; Gibas, E.; Malinowski, R. Selected Biodegradable Polymers—Preparation, Properties, Applications. Polimery 2022, 53, 799–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foltynowicz, Z.; Jakubiak, P. Polylactid Acid—Biodegradable Polymer Obtained from Vegetable Resources. Polimery 2022, 47, 769–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villavicencio, A. Wykorzystanie Pozaklasowego Włókna Alpak i Wełny Owczej Do Zastosowania w Różnych Sektorach Gospodarki. Przegląd Włókienniczy-Włókno Odzież Skóra 2022, 1, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Hossain, N.; Hasan, F.; Rahman, S.M.; Khan, S.; Saifullah, A.Z.A.; Chowdhury, M. Advances of Natural Fiber Composites in Diverse Engineering Applications—A Review. Appl. Eng. Sci. 2024, 18, 100184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Du, M.; Liu, F. Recent Advances in Interface Microscopic Characterization of Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites. Front. Mater. 2023, 10, 1124338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathishkumar, T.P.; Navaneethakrishnan, P.; Shankar, S.; Rajasekar, R.; Rajini, N. Characterization of Natural Fiber and Composites—A Review. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2013, 32, 1457–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlé, T.; Nguyen, G.T.M.; Ledesert, B.; Mélinge, Y.; Hebert, R.L. Cross-Linked Polyurethane as Solid-Solid Phase Change Material for Low Temperature Thermal Energy Storage. Thermochim. Acta 2020, 685, 178191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiebat, F.; Fregonara, E.; Masoero, A.; Morselli, F.; Senatore, C.; Giordano, R. Circular Design for Natural Fibers: A Literature Review on Life Cycle Evaluation Approaches for Environmental, Social and Economic Sustainability. Preprints 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawlak, F.; Aldas, M.; Parres, F.; López-Martínez, J.; Arrieta, M.P. Silane-Functionalized Sheep Wool Fibers from Dairy Industry Waste for the Development of Plasticized PLA Composites with Maleinized Linseed Oil for Injection-Molded Parts. Polymers 2020, 12, 2523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szatkowski, P.; Tadla, A.; Flis, Z.; Szatkowska, M.; Suchorowiec, K.; Molik, E. The Potential Application of Sheep Wool as a Component of Composites. Anim. Sci. Genet. 2021, 17, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 1183-1:2025; Plastics—Methods for Determining the Density of Non-Cellular Plastics—Part 1: Immersion Method, Liquid Pycnometer Method and Titration Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025.

- ISO 527-1:2019; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties—Part 1: General Principles. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ISO 178:2019; Plastics—Determination of Flexural Properties. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- ASTM D2654-22; Standard Test Methods for Moisture in Textiles. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ISO 604:2002; Plastics—Determination of Compressive Properties. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2002.

- ISO 179-1:2023; Plastics—Determination of Charpy Impact Properties—Part 1: Non-Instrumented Impact Test. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- ASTM D570-22; Standard Test Method for Water Absorption of Plastics. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2022.

- ISO 62:2008; Plastics—Determination of Water Absorption. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- ISO 11357 1:2023; Plastics—Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)—Part 1: General Principles. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- ISO 14855 1:2012; Determination of the Ultimate Aerobic Biodegradability of Plastic Materials Under Controlled Composting Conditions—Method by Analysis of Evolved Carbon Dioxide—Part 1: General Method. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- ASTM D5988 18; Standard Test Method for Determining Aerobic Biodegradation of Plastic Materials in Soil. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2018.

- ISO 9073 1:2023; Nonwovens—Test Methods—Part 1: Determination of Mass per Unit Area. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023.

- Szatkowski, P. The Influence of Various Chemical Modifications of Sheep Wool Fibers on the Long-Term Mechanical Properties of Sheep Wool/PLA Biocomposites. Materials 2025, 18, 3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pach, J.; Mayer, P. Polymer Composites Reinforced with Natural Fibers Developed for the Needs of Contemporary Automotive Industry. Mechanik 2010, 4, 270–274. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.K.; Lin, R.J.T.; Bhattacharyya, D. Effects of Wool Fibres, Ammonium Polyphosphate and Polymer Viscosity on the Flammability and Mechanical Performance of PP/Wool Composites. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2015, 119, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasina, M.; Straznicky, P.; Hrbacek, P.; Rusnakova, S.; Bosak, O.; Kubliha, M. Investigation of Physical Properties of Polymer Composites Filled with Sheep Wool. Polymers 2024, 16, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boey, J.Y.; Lee, C.K.; Tay, G.S. Factors Affecting Mechanical Properties of Reinforced Bioplastics: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Cao, B.; Jiang, N. The Mechanical Properties and Degradation Behavior of 3D-Printed Cellulose Nanofiber/Polylactic Acid Composites. Materials 2023, 16, 6197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanakannavar, S.; Pitchaimani, J.; Thalla, A.; Rajesh, M. Biodegradation Properties and Thermogravimetric Analysis of 3D Braided Flax PLA Textile Composites. J. Ind. Text. 2022, 51, 1066S–1091S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Drozdov, A.D. The Use of Various Measurement Methods for Estimating the Fracture Energy of PLA (Polylactic Acid). Materials 2022, 15, 8623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pooley, L.I.; Abu-Bakar, A.S.; Cran, M.J.; Wadhwani, R.; Moinuddin, K.A.M. Measurements of Specific Heat Capacity of Common Building Materials at Elevated Temperatures: A Comparison of DSC and HDA. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020, 141, 1279–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farah, S.; Anderson, D.G.; Langer, R. Physical and Mechanical Properties of PLA, and Their Functions in Widespread Applications—A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2016, 107, 367–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesentini, Z.; El Mahi, A.; Rebiere, J.-L.; El Guerjouma, R.; Beyaoui, M.; Haddar, M. Effect of Hydric Aging on the Static and Vibration Behavior of 3D Printed Bio-Based Flax Fiber Reinforced Poly-Lactic Acid Composites. Polym. Polym. Compos. 2022, 30, 096739112210818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

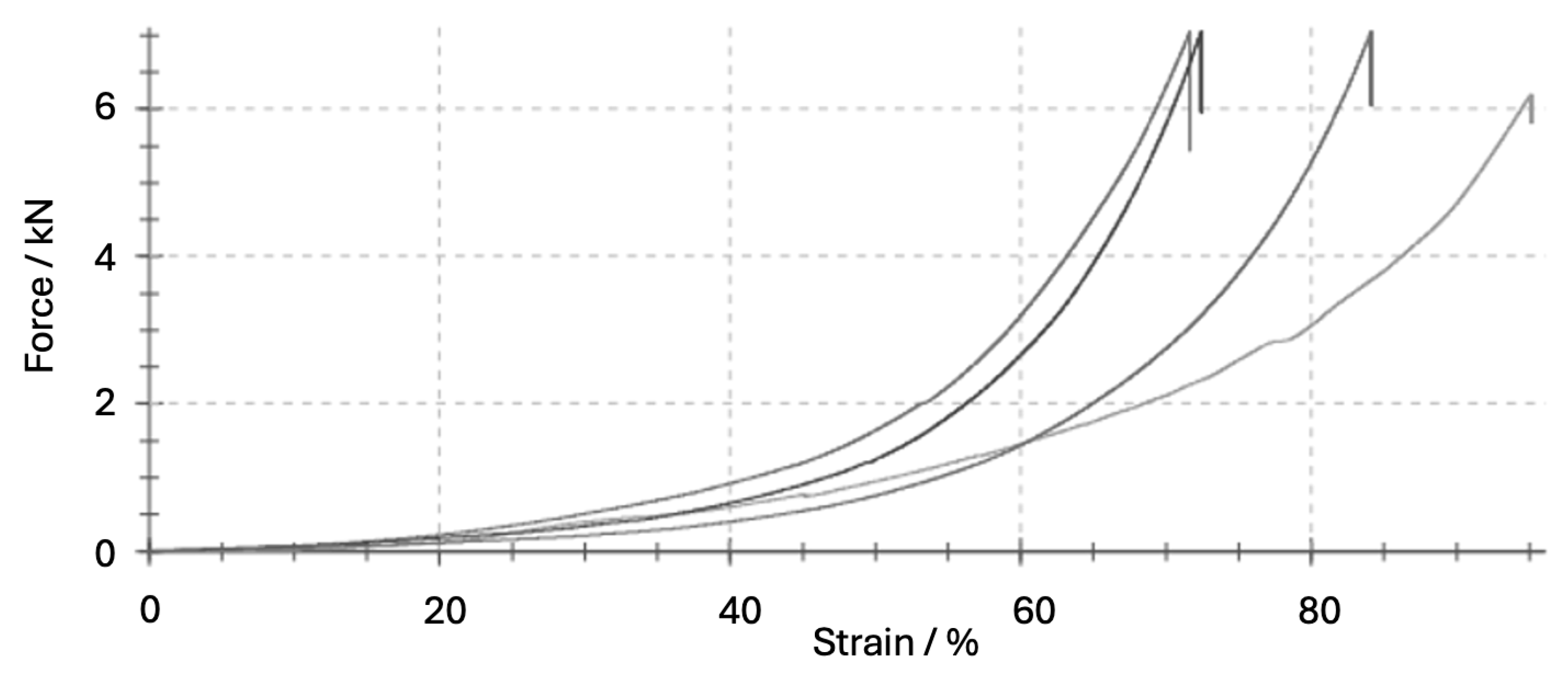

| Parameter | Unit | Mean ± SD | Coefficient of Variation (%) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Specimen dimension | ||||

| Width (a) | mm | 20.0 ± 0.2 | 1.0 | ISO 604 [22] requirement |

| Thickness (h) | mm | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 7.1 | Measured at 5 points |

| Length (L) | mm | 80.0 ± 1.0 | 1.3 | Testing standard |

| Cross-sectional area (A) | mm2 | 84.0 ± 7.5 | 8.9 | A = a × h |

| Force measurements | ||||

| Maximum compressive force (Fmax) | N | 6840 ± 427 | 6.2 | Raw output from testing machine |

| Yield force (Fy) | N | 4930 ± 325 | 6.6 | 10% offset method |

| Derived mechanical properties | ||||

| Compressive strength (σmax) | MPa | 23.56 ± 5.23 | 26.3 | σmax = Fmax/A |

| Yield strength (σy) | MPa | 8.75 ± 1.02 | 11.7 | σy = Fy/A |

| Young’s modulus (E) | GPa | 1.439 ± 0.263 | 18.3 | E = Δσ/Δε (0–2% strain range) |

| Work of destruction (Wtotal) | J | 21.97 ± 3.9 | 17.6 | Wtotal = ∫F·dL/1000 |

| Deformation at Fmax (ΔL) | mm | 16.2 ± 2.2 | 13.7 | Extension at failure |

| Strain at F_max (εmax) | % | 20.3 ± 2.8 | 13.8 | ε = ΔL/L × 100% |

| Impact strength (Charpy) | kJ | 19 ± 2 | 10.5 | See Table 3 for details |

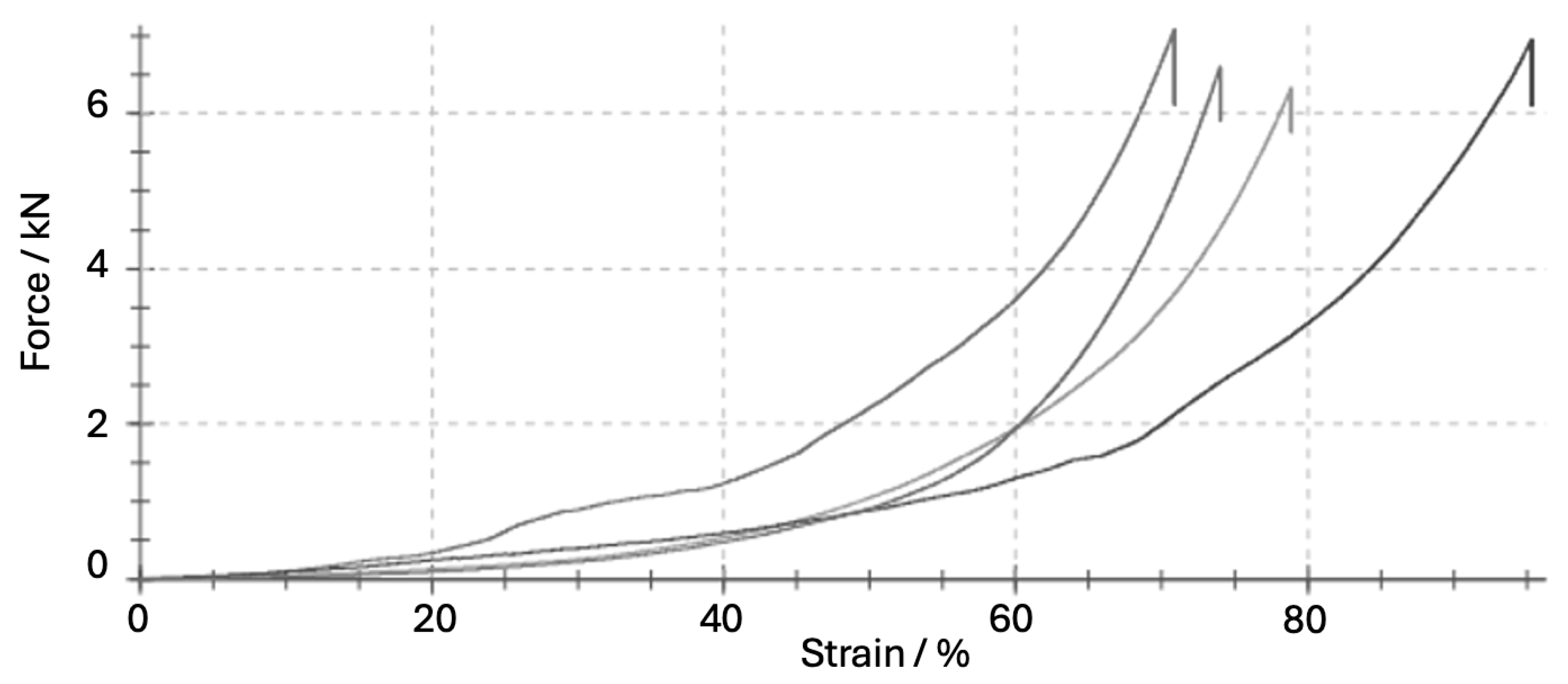

| Parameter | Unit | Mean ± SD | Coefficient of Variation (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specimen dimension (after degradation) | |||

| Width | mm | 20.1 ± 0.3 | 1.5 |

| Thickness | mm | 4.3 ± 0.4 | 9.3 |

| Cross-sectional area | mm2 | 86.4 ± 8.2 | 9.5 |

| Force measurements | |||

| Maximum compressive force (Fmax) | N | 6740 ± 337 | 5.0 |

| Compressive strength (σmax) | MPa | 9.67 ± 4.23 | 43.7 |

| Young’s modulus (E) | GPa | 1.079 ± 0.529 | 49.0 |

| Work of destruction (Wtotal) | J | 22.04 ± 5.7 | 25.9 |

| Impact strength (Charpy) | kJ | 12 ± 1.5 | 12.5 |

| Mass retention | % | 13.6 ± 2.1 | 15.4 |

| Type of Material | Specific Impact Strength (kJ/m2) |

|---|---|

| PLA/wool (non-biodegradable) | 0.226 ± 0.023 |

| PLA/wool (after biodegradation) | 0.142 ± 0.017 |

| Pure PLA (reference) | 0.600 ± 0.017 |

| Sample Description | Measurement Method | Density (g/cm3) | Void Fraction (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLA–wool composite (pre-degradation) | Geometric method (ISO 1183) | 0.27 ± 0.02 | ~78 | Highly porous structure |

| PLA–wool composite (post-degradation, 6 weeks) | Geometric method (ISO 1183) | 0.31 ± 0.03 | ~75 | Density increases due to moisture loss and fibre compaction |

| Reference material: pure PLA (4032D) | Literature value | 1.24 | N/A | NatureWorks datasheet; measured per ISO 1183 on solid samples |

| Reference material: water | Literature value | 1.00 | N/A | At 20 °C, for context |

| Sample | Thermal Conductivity in Λ [W/m·K] |

|---|---|

| Wool panel | 0.1270 |

| Wool panel after degradation | 0.1920 |

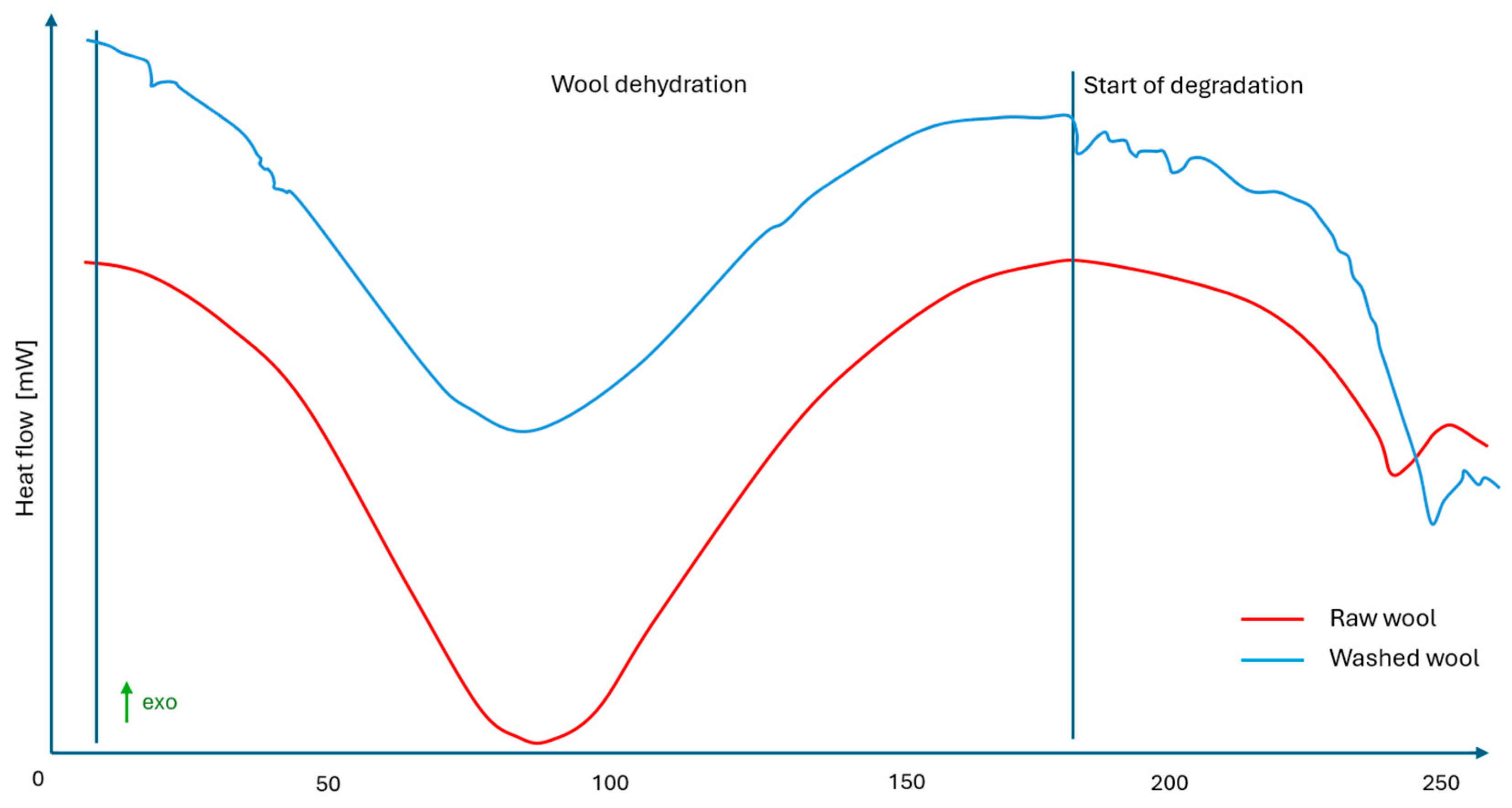

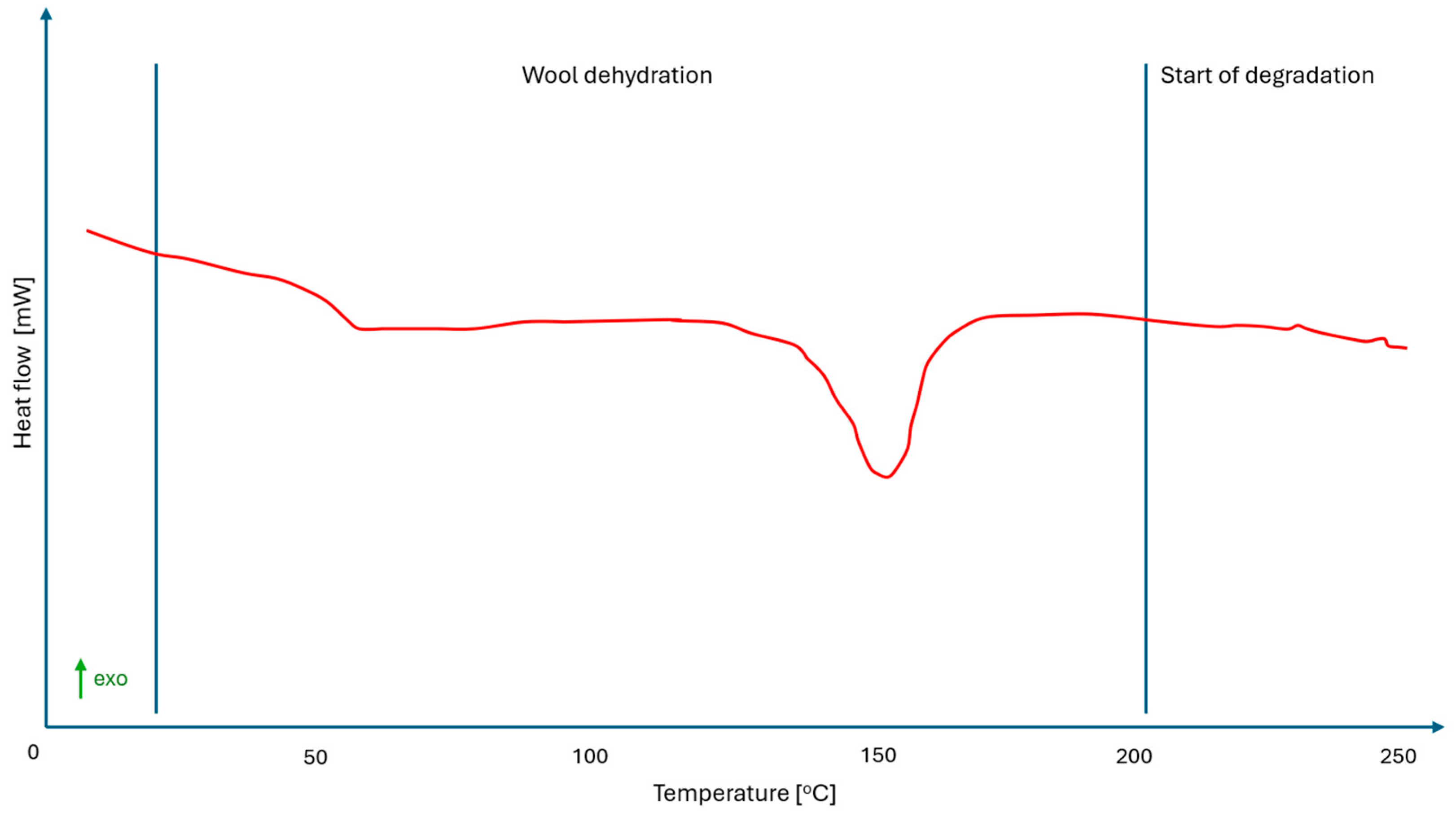

| Temp. Max Peak of Dehydration Wool [°C] | Heat of Evaporation [J/g] | Temp. of Start Degradation [°C] | Glass Temperature [°C] | ΔCp ISO [J/(g·K)] | Temp. Melt of PLA Matrix [°C] | Heat of Fusion of PLA Matrix [J/g] | PLA Crystallinity [%] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raw wool | 91 | 225.4 | 202 | - | - | - | - | |

| Washed wool | 88 | 229.8 | 179 | - | - | - | - | |

| PLA/washed sheep wool biocomposite | - | - | 220 | 62 | 0.240 | 159 | 14.79 | 32% |

| Metric | Group 1 (After 6 Week Degradation) | Group 2 (Control) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Loss (%) | 13.6 ± 2.1 * | 3.0 ± 1.1 * | Higher loss in G1 due to increased moisture-driven hydrolysis |

| Compressive Strength Retention (%) | 41 ± 8 | 12 ± 7 | 59% reduction in strength (59% loss) across all groups |

| Young’s Modulus Retention (%) | 75 ± 5 | 21 ± 6 | 25% reduction in stiffness; matrix hydrolysis primary mechanism |

| Work of Destruction Retention (%) | 80 ± 15 | 23 ± 10 | Slight increase in energy absorption post-degradation (counterintuitive; see Discussion) |

| Surface Colour Change | 3 (moderate yellowing) | 2.5 (mild yellowing) | Indicates PLA photo/thermal degradation; correlates with UV exposure and microbial activity |

| Visible Fibre–Matrix Debonding | Yes (extensive) | Moderate | G1 (high moisture) shows most severe debonding; evidence of hydrolytic cleavage |

| Microbial Colonisation (fungi/bacteria) | Heavy (fungal mycelium visible) | Moderate | G1 moisture promotes fungal growth; consistent with mass loss trend |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Szatkowski, P.; Barwinek, J.; Zhakypbekovich, A.I.; Szczecina, J.; Niemiec, M.; Pielichowska, K.; Molik, E. The Use of Sheep Wool Collected from Sheep Bred in the Kyrgyz Republic as a Component of Biodegradable Composite Material. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13054. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413054

Szatkowski P, Barwinek J, Zhakypbekovich AI, Szczecina J, Niemiec M, Pielichowska K, Molik E. The Use of Sheep Wool Collected from Sheep Bred in the Kyrgyz Republic as a Component of Biodegradable Composite Material. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13054. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413054

Chicago/Turabian StyleSzatkowski, Piotr, Jakub Barwinek, Alykeev Ishenbek Zhakypbekovich, Julita Szczecina, Marcin Niemiec, Kinga Pielichowska, and Edyta Molik. 2025. "The Use of Sheep Wool Collected from Sheep Bred in the Kyrgyz Republic as a Component of Biodegradable Composite Material" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13054. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413054

APA StyleSzatkowski, P., Barwinek, J., Zhakypbekovich, A. I., Szczecina, J., Niemiec, M., Pielichowska, K., & Molik, E. (2025). The Use of Sheep Wool Collected from Sheep Bred in the Kyrgyz Republic as a Component of Biodegradable Composite Material. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13054. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413054