To demonstrate the effectiveness of Physics-Informed and Transfer-Learned FNOs in handling shock-dominated transport, we consider the one-dimensional B-L displacement problem as a representative benchmark. This case offers a well-understood analytical structure while exhibiting strong nonlinearities and sharp saturation fronts that pose challenges for extrapolation. The numerical experiments are designed to assess the ability of different operator-learning frameworks to generalize beyond the training regime in extended time horizons and altered mobility ratios. By comparing the baseline FNO with its physics-informed and transfer-learning extensions, we highlight how these strategies improve predictive accuracy, shock-front tracking, and data efficiency in scenarios where conventional FNOs typically fail.

3.1. Problem Setup

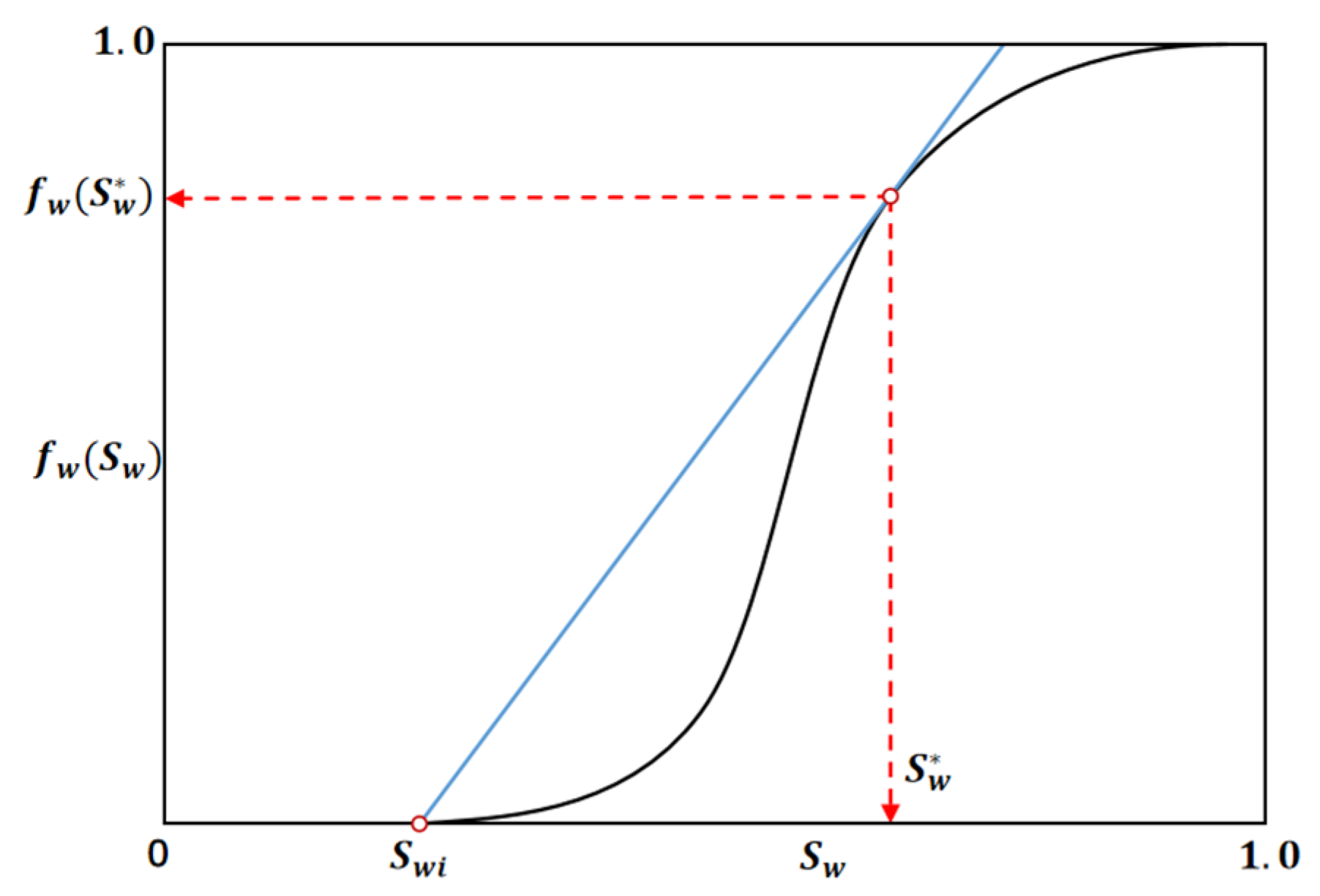

Numerical experiments were conducted on a one-dimensional homogeneous reservoir model of 100 m length in the x-direction, with the formation and fluid parameters summarized in

Table 1. The endpoint mobility ratio

M = 2 was determined from the corresponding relative permeability and viscosity values listed in

Table 1. Using these parameters, analytical B-L solutions were generated via Welge’s graphical method. For the baseline FNO, For the baseline FNO, a dataset of 2048 observation pairs

was used, where

denotes the

-th sample of the input field

, representing initial water saturation,

ui(

x) represents the corresponding water saturation at a later specified time. These pairs are partitioned into 1248 training, 400 validation, and 400 testing samples. The training interval was restricted to [0.5, 2.0] days, while validation and testing extended to [2.0, 5.0] days, enabling assessment of temporal extrapolation. All training data were generated on a standard workstation equipped with an Intel i7 CPU (3.4 GHz) and 32 GB of RAM. The input dataset is a tensor (

NT,

NX,

NC), where

NT = 2048 (time steps),

NX = 8192 (spatial discretization), and

NC = 2 (channels: water saturation, time).

A FNO is trained to predict the saturation profile at the next time step given the current profile. During training, inputs are lifted into a higher-dimensional space, transformed through stacked spectral layers where Fourier coefficients are updated, and projected back to the physical domain to yield predictions. The model parameters are optimized by minimizing the mean-squared error between predictions and reference solutions via Adam optimizer. Once trained, the FNO predicts full saturation profiles in under 1 ms, representing a 10~100 times speedup compared with a conventional finite-difference Buckley–Leverett solver.

3.2. Baseline FNO Performance

We establish a baseline using the FNO trained purely on data without physics or transfer-learning enhancements. The model was trained on the training dataset, with the training set covering time intervals up to 2 days and a fixed mobility ratio of

M = 2. Evaluation was performed both within the training regime (interpolation) and beyond it (extrapolation to longer times and different mobility ratios).

Figure 4 shows that the baseline FNO demonstrates strong interpolation performance, accurately reproducing the water saturation profiles and capturing the rarefaction and displacement fronts. Comparison with the analytical B-L solution (blue solid line) confirms excellent agreement within the training regime.

The coefficient of determination (

R2), mean squared error (MSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) are used to quantify the difference between the predicted and analytical saturation profiles. The coefficient

is defined as:

where

denotes the reference saturation values,

the predicted values, and

their mean. A value of

close to 1 indicates strong agreement between the predicted and analytical solutions.

Table 2 summarizes the interpolation accuracy of the baseline FNO across different time snapshots within the training regime. The model achieves consistently high correlation with the analytical B-L solution, with

for all cases. Both MSE and MAE remain extremely small, indicating that the FNO almost perfectly reconstructs the saturation profiles and accurately captures the sharp displacement fronts. Although MSE and MAE show a slight increasing trend as time approaches breakthrough (e.g., at

and

days), the errors remain negligible and do not affect the overall shape or position of the saturation front. These results demonstrate that the baseline FNO performs exceptionally well in the interpolation regime and provides a reliable reference point for evaluating extrapolative performance in later sections.

Yet, in the extrapolation regime, the limitations of a purely data-driven FNO become evident as demonstrated in

Figure 5.

Figure 5 illustrates the baseline FNO predictions compared against analytical B-L solutions at times extending beyond the training window [0.5, 2.0] days, and the accuracy trends are quantified in

Table 3, together demonstrating the model’s strong interpolation capability but limited reliability in extrapolation. At

t = 2.0 days, within the trained temporal domain, the FNO reproduces the saturation profile with near-perfect accuracy (R

2 ≈ 1.0). Even so, as time progresses beyond

t = 2.0 days, the predictions gradually deviate from the analytical solutions. At

t = 2.6 days, the deviation remains minor, but from t = 3.2 days onward, noticeable discrepancies emerge, the predicted front becomes steeper near the inlet and shallower near the outlet. By

t = 3.8~5.0 days, the predicted saturation front lags markedly behind the analytical solution, reflecting accumulated temporal errors and a loss of physical consistency, with the

R2 dropping below 0.5 at

t = 5.0 days. Moreover, the MSE and MAE increase consistently with time, demonstrating that whereas the FNO is an efficient interpolator, it lacks robustness for long-term extrapolation of nonlinear hyperbolic B-L.

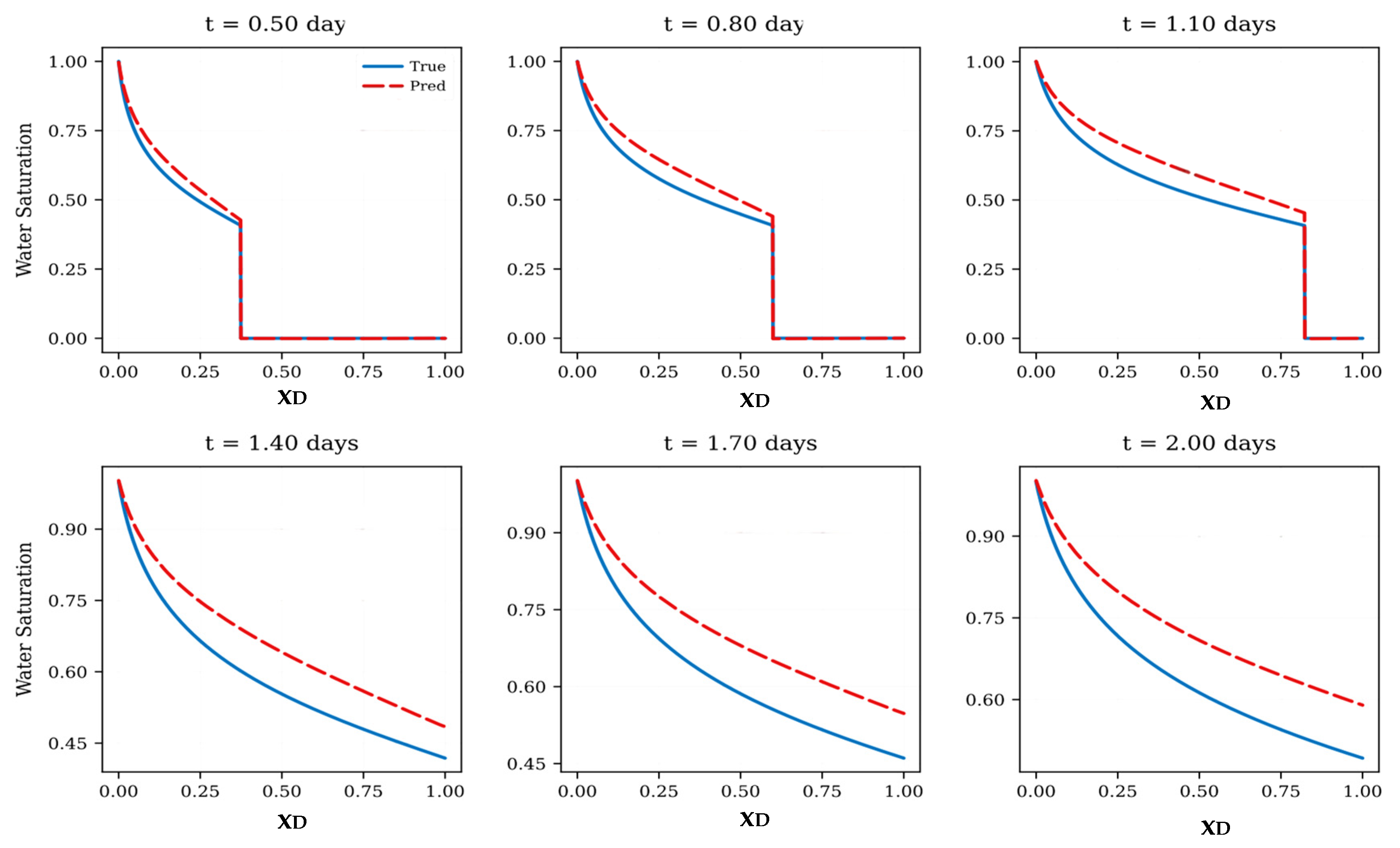

Figure 6 presents baseline FNO predictions when the mobility ratio is shifted from the training condition of

M = 2 to

M = 5. As demonstrated, at early times (

t = 0.5~1.1 days), the model captures the overall trend but fails to reproduce the sharp saturation front characteristic of higher mobility ratios, leading to smoother and prematurely advanced predictions. As time progresses (

t = 1.4–2.0 days), the discrepancy increases, with the model consistently overestimating water saturation across the domain. The predicted front becomes diffused and lags in representing the strong nonlinear displacement behavior present in the analytical solution.

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 collectively highlight the limitations of the baseline FNO in extrapolation. In the temporal domain (

Figure 5), the model reproduces saturation profiles accurately within the training window but progressively loses accuracy at later times. In the parameter domain (

Figure 6), the shift from

M = 2 to

M = 5 further exposes the model’s weaknesses, as it fails to generalize to more unstable displacement conditions, yielding significant errors in water saturation. Together, these results confirm that while the FNO is a powerful interpolator, it lacks robustness for extrapolation in both time and parameter space, motivating the introduction of physics-informed and transfer-learning strategies.

Table 4 summarizes the extrapolation performance of the baseline FNO when the mobility ratio is shifted from the training regime (

) to

. Unlike the interpolation case, the accuracy deteriorates noticeably as time increases. Although the model maintains relatively high fidelity at early times (

for

~0.8 days), the predictive capability drops sharply beyond

days, with

falling to 0.478 by

days. The increasing MSE and MAE indicate cumulative errors in saturation magnitude, consistent with the observed smoothing of the displacement front. These results demonstrate that the baseline FNO struggles to generalize across mobility ratios, underscoring the need for physics-informed constraints or transfer learning to achieve reliable extrapolation in more unstable flow conditions.

3.3. Transfer-Learned FNO Performance

The baseline results in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 demonstrate that the standard FNO, although accurate within the training regime, lacks robustness when extrapolated to longer times or shifted mobility ratios. To address this limitation, we investigate the use of TL-FNOs in the subsection. TL-FNOs leverage knowledge from a source model trained under one regime and adapt it efficiently to new target conditions. In this study, the source model is trained on B-L saturation profiles at

M = 2, and transfer learning is applied to adapt the operator to unseen regime at

M = 5. This strategy enables reuse of spectral representations already learned in the source model, while freezing all Fourier layers and fine-tuning only parameters at the linear lifting and projection layers with 300 target samples. By doing so, TL-FNO aims to accelerate convergence, reduce data requirements, and enhance extrapolation performance compared with training from scratch.

The contrast between

Figure 6 and

Figure 7 underscores the value of transfer learning for extrapolating B-L solutions.

While the baseline FNO fails to generalize when the mobility ratio shifts to M = 5, over-estimate the water saturations, the TL-FNO successfully adapts with only limited target data. By reusing spectral features from the source regime and fine-tuning selected layers, the TL-FNO provides accurate front propagation, demonstrating a substantial improvement in both accuracy and data efficiency.

Table 5 demonstrates that the TL-FNO achieves excellent extrapolation performance when transferring from the training regime (

) to the target regime (

).

Across all time snapshots, the model maintains exceptionally high accuracy, with values exceeding 0.998 and MSE and MAE remaining several orders of magnitude smaller than those of the baseline FNO. Errors increase slightly at later times, reflecting the greater difficulty of capturing sharper displacement fronts as the saturation evolves, but remain very small overall. These results indicate that transfer learning effectively leverages knowledge from the source regime and enables robust adaptation to new mobility ratios with limited target data, significantly outperforming the baseline model in both accuracy and stability.

3.4. Physics-Informed Neural Operator Performance

While transfer learning improves the adaptability of FNOs across parameter regimes, it remains fundamentally data-driven and dependent on representative training samples. To further enhance extrapolative reliability, we incorporate the B-L equation directly into the operator-learning framework. In addition, to capture the flow characteristics of subsurface reservoirs under different mobility ratios, the mobility ratio M was explicitly incorporated into the FNO training dataset. Using the same formation and fluid parameters listed in

Table 1, M was varied between 1 and 10. Consequently, the input tensor takes the form (2048, 8192, 3), where the three channels correspond to water saturation, spatial sampling, and mobility ratio. An FNO was trained to predict the saturation profile at a later time (t = 2.0 days) from the profile at an earlier time (t = 0.5 day) across the range of mobility ratios.

Figure 8 compares the FNO predictions with analytical B-L solutions for different interpolated values of M. The results demonstrate that the model interpolates well across the mobility-ratio spectrum, with the predicted saturation fronts closely matching the analytical benchmarks.

Table 6 summarizes the interpolation performance of the FNO when predicting B-L saturation profiles at mobility ratios lying between the training samples. Across all tested values of

, the model achieves excellent agreement with the analytical solutions, with

consistently above 0.98 and MSE and MAE remaining on the order of

~

. The accuracy is highest for intermediate values (e.g.,

~6.4), where both MAE and MSE fall below

, reflecting smooth interpolation within the learned parameter manifold. Even at the edges of the interpolation range (

and

), the model maintains strong performance, demonstrating robust parametric generalization. These results indicate that the baseline FNO effectively captures the mobility-ratio dependence of fractional flow dynamics and provides reliable predictions for intermediate parameter values. However, its reliability diminishes when applied outside the training domain, motivating the use of physics-informed and transfer-learning strategies to improve extrapolation.

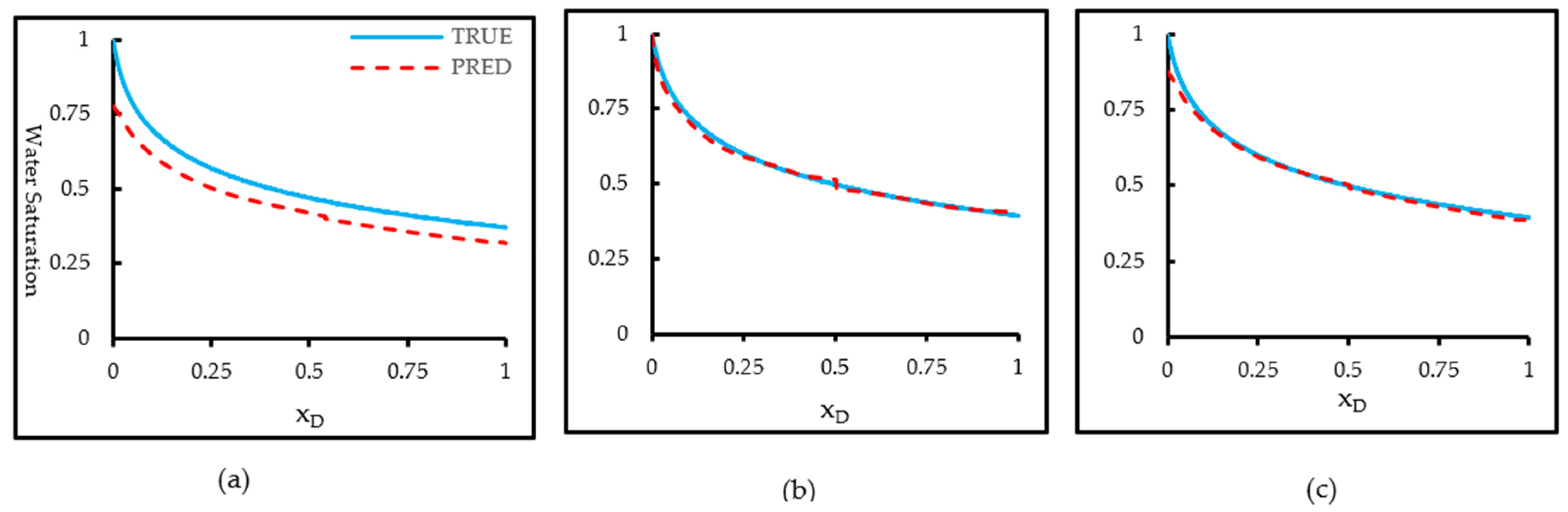

Figure 9 compares the analytical B-L solution with model predictions for extrapolation to mobility ratio M = 15, a regime beyond the training range of [1, 10]. The comparison (

Figure 9a) reveals that the baseline FNO captures the overall decreasing trend of water saturation with distance but exhibits a systematic underestimation across the entire domain. The predicted saturation front is displaced downward, reflecting the model’s inability to replicate the stronger instability and sharper displacement front associated with the higher mobility ratio. This discrepancy indicates that the trained operator, although effective within its original parameter regime, struggles to generalize to more extreme flow contrasts.

The PI-FNO shown in

Figure 9b demonstrates significant improvement. By embedding PDE residuals and enforcing initial and boundary conditions, the model closely reproduces the analytical saturation distribution. The close agreement between the two curves demonstrates that embedding physical constraints into the learning framework significantly enhances generalization beyond the training domain. The physics-constrained model accurately captures both the nonlinear curvature near the inlet and the smooth saturation decline along the spatial domain, preserving the underlying flux-saturation relationship dictated by the governing equation. The TL-FNO in

Figure 9c also enhances extrapolation performance compared with the baseline. Through fine-tuning a pretrained FNO from the

M = 10 regime using 300 target samples at

M = 15, the TL-FNO achieves reduced error and better alignment with the analytical solution, effectively capturing the nonlinear saturation profile throughout most of the domain. The strong correspondence indicates that knowledge adaptation from pre-trained models enhances the learning of transport dynamics under new mobility conditions. Nevertheless, slight deviations near the inlet suggest residual bias in reproducing the steep saturation gradient, likely due to local variations not fully represented in the source domain. The overall accuracy remains slightly below that of PI-FNO.

Table 7 summarizes the extrapolation performance of the Baseline FNO, PI-FNO, and TL-FNO at a mobility ratio of

M = 15 and confirms the trends observed in

Figure 9, providing quantitative support for the visual comparison of extrapolation performance among the three models.

In summary, PI-FNO delivers the most accurate and physically consistent extrapolation, while TL-FNO offers strong performance with higher data efficiency. Together, these approaches effectively mitigate the limitations of the baseline FNO in shock-dominated regimes beyond the training domain.

From a practical perspective, the proposed Physics-Informed and Transfer-Learned Fourier Neural Operators (PI-FNO and TL-FNO) provide a general framework that can be seamlessly integrated into industrial reservoir simulation workflows. Once trained, these operator-based surrogates can rapidly predict spatiotemporal saturation distributions for new boundary, initial, or parameter conditions, achieving orders-of-magnitude speedup compared with conventional simulators. The PI-FNO enhances physical consistency through PDE-based regularization, whereas the TL-FNO enables efficient adaptation to new reservoir conditions with limited data, making both models well suited for large-scale optimization, history matching, and uncertainty quantification. For real-world applications such as heterogeneous reservoirs and multidimensional geometries, the corresponding data and governing PDEs must be incorporated to ensure physical representativeness and model fidelity. Although model training introduces an upfront computational cost, it is performed offline and requires only moderate hardware resources. Overall, the proposed method is general, scalable, and complementary to existing simulators, providing a practical pathway toward real-time, data-efficient modeling of multiphase flow in complex reservoir systems.

If the B-L equation were extended to include heterogeneous porous media, compressibility, or capillary effects, the extrapolative performance of both PI-FNO and TL-FNO would likely depend on the accuracy with which these additional physical mechanisms are represented in the governing equations and training data. The PI-FNO could potentially maintain physical consistency by incorporating extended PDE residuals and additional terms in the loss function, but its performance might degrade if the underlying physics or constitutive relationships are incomplete or highly nonlinear. In heterogeneous or multidimensional reservoirs, the spatial variability in permeability and saturation fronts introduces stronger gradients and localized discontinuities, which may challenge the current one-dimensional formulation. Consequently, the PI-FNO may exhibit reduced accuracy or slower convergence in such cases, while the TL-FNO could alleviate part of this degradation by leveraging pretrained operators from similar physical regimes and adapting them to complex domains with limited fine-scale data. Future work will therefore focus on extending the methodology to heterogeneous and multidimensional systems through multi-fidelity learning, adaptive loss weighting, and hierarchical domain decomposition, thereby enhancing the robustness, generality, and scalability of operator learning for realistic reservoir applications.