A 3D CNN Prediction of Cerebral Aneurysm in the Bifurcation Region of Interest in Magnetic Resonance Angiography

Abstract

1. Introduction

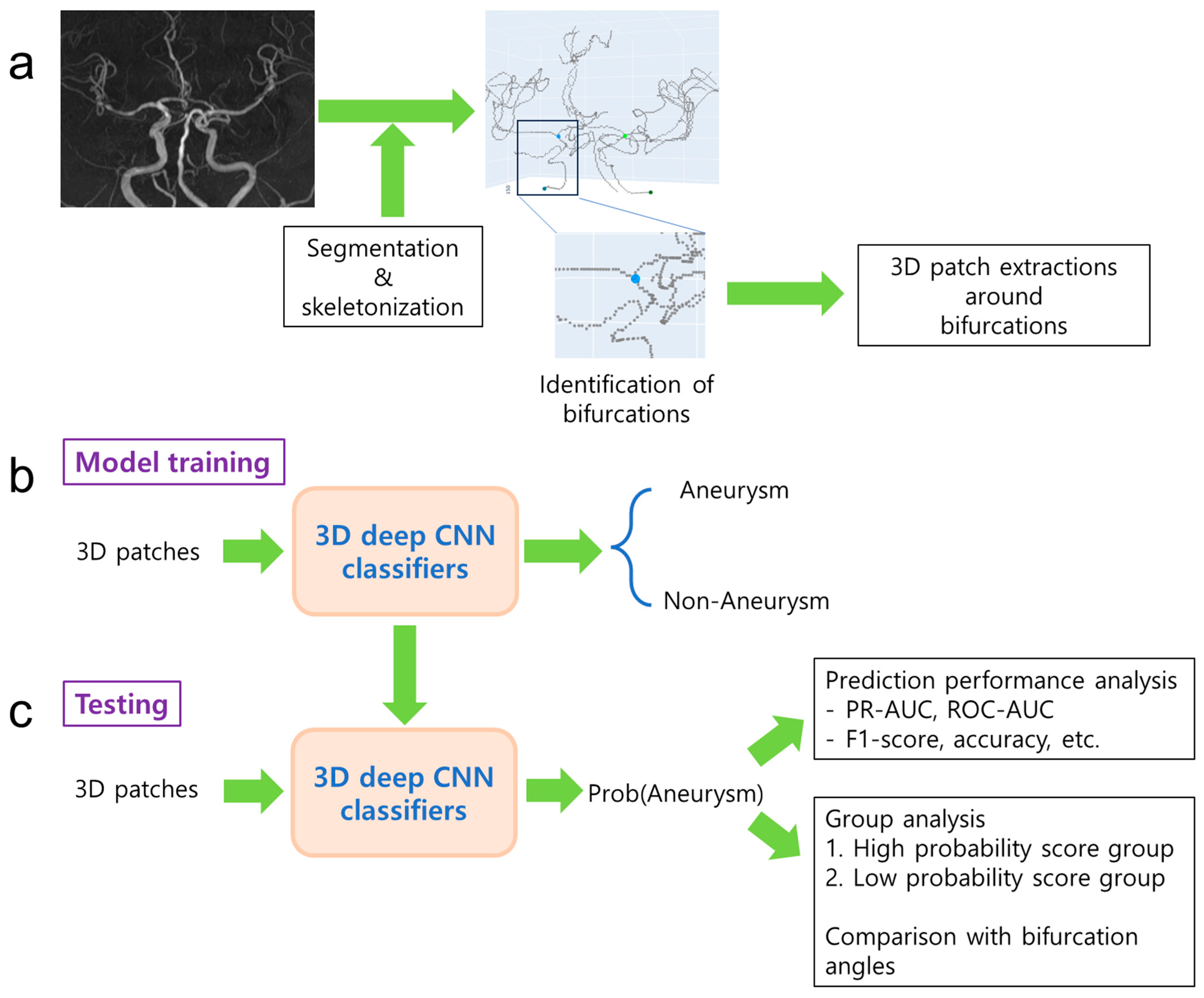

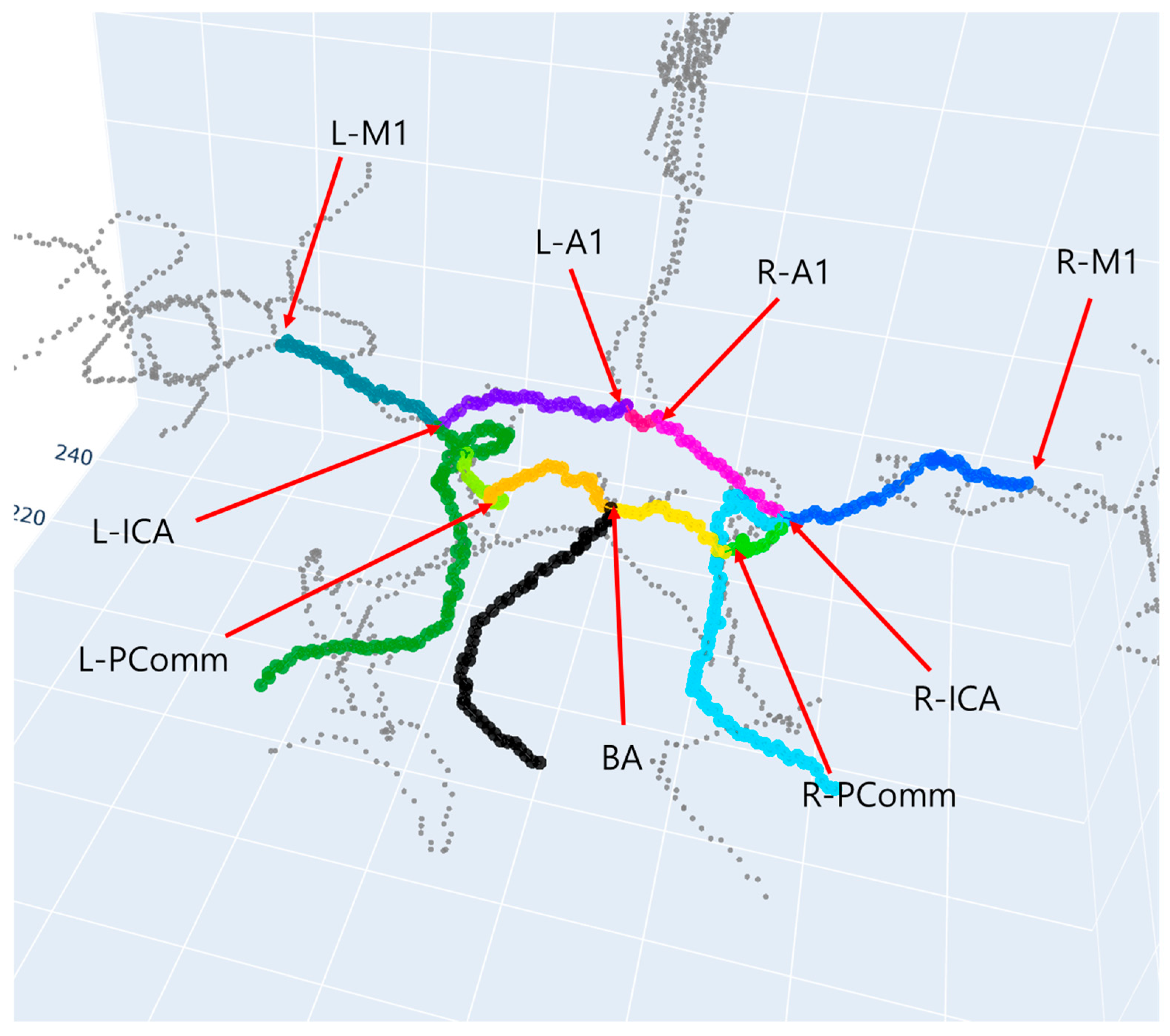

2. Methods

2.1. Data

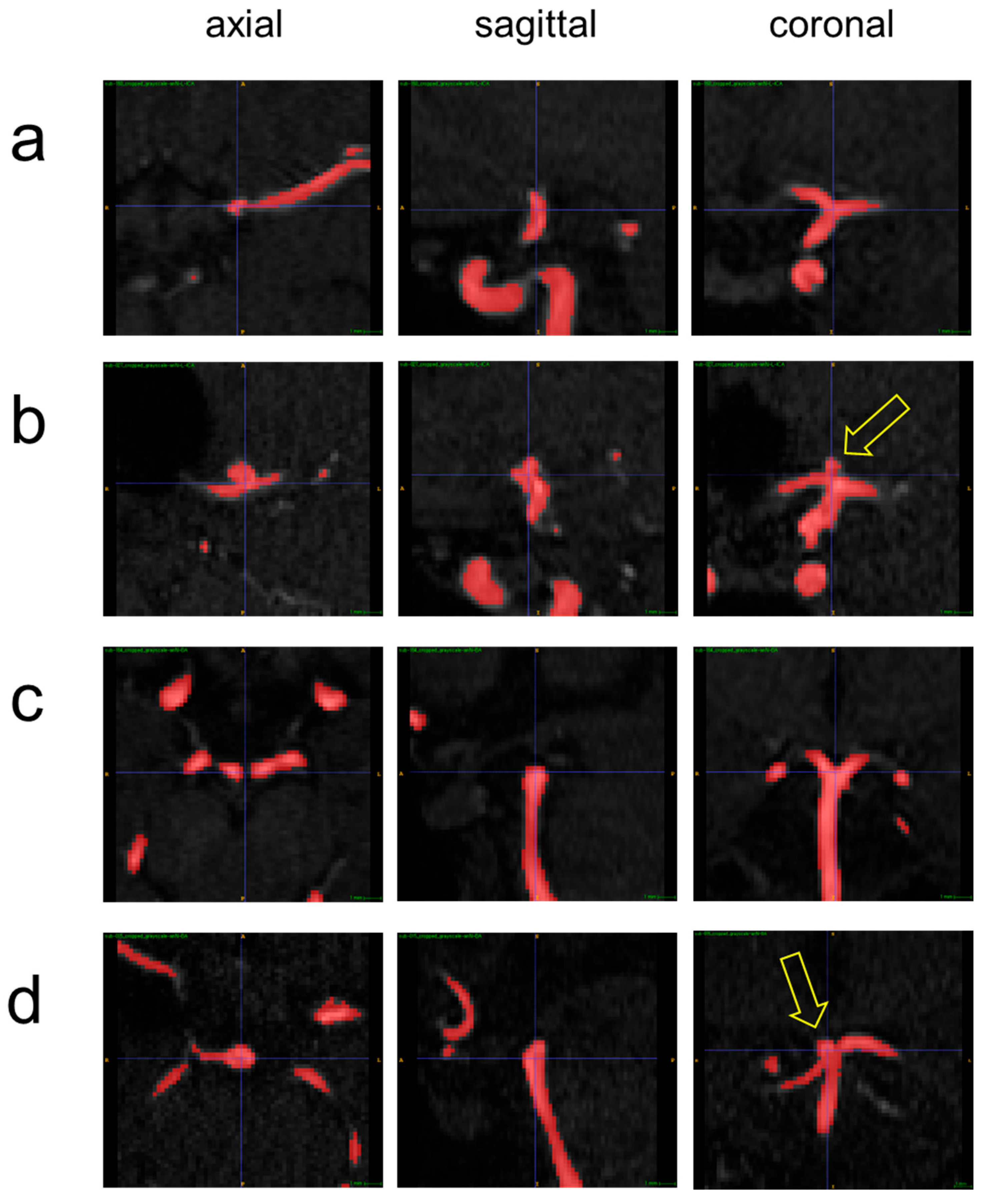

2.2. Data Labeling

2.3. Model Development

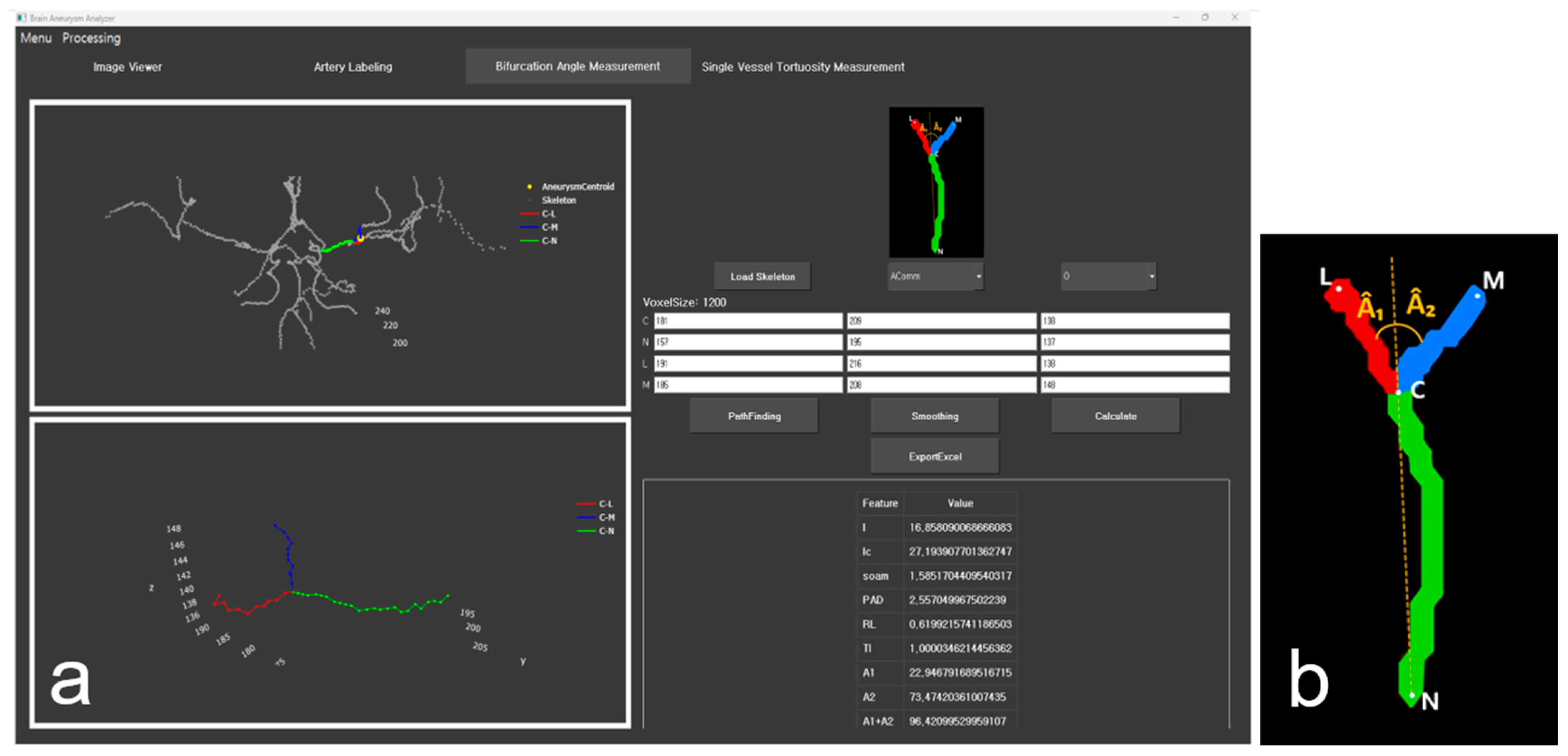

2.4. Evaluation

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hackenberg, K.A.M.; Hanggi, D.; Etminan, N. Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms. Stroke 2018, 49, 2268–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalouhi, N.; Hoh, B.L.; Hasan, D. Review of cerebral aneurysm formation, growth, and rupture. Stroke 2013, 44, 3613–3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, M.; Wang, S.; Qian, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Luo, Y.; Gong, X. Intracranial aneurysm CTA images and 3D models dataset with clinical morphological and hemodynamic data. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jeon, T.Y.; Jeon, P.; Kim, K.H. Prevalence of unruptured intracranial aneurysm on MR angiography. Korean J. Radiol. 2011, 12, 547–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, G.; Cerejo, R. Intracranial aneurysms: Review of current science and management. Vasc. Med. 2018, 23, 276–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claux, F.; Baudouin, M.; Bogey, C.; Rouchaud, A. Dense, deep learning-based intracranial aneurysm detection on TOF MRI using two-stage regularized U-Net. J. Neuroradiol. 2023, 50, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heit, J.J.; Honce, J.M.; Yedavalli, V.S.; Baccin, C.E.; Tatit, R.T.; Copeland, K.; Timpone, V.M. RAPID Aneurysm: Artificial intelligence for unruptured cerebral aneurysm detection on CT angiography. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2022, 31, 106690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Jin, Y.; Ye, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W. Classification, detection, and segmentation performance of image-based AI in intracranial aneurysm: A systematic review. BMC Med. Imaging 2024, 24, 164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anima, V.; Nair, M.S. On the automated unruptured intracranial aneurysm segmentation from tof-mra using deep learning techniques. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 53112–53125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nader, R.; Bourcier, R.; Autrusseau, F. Using deep learning for an automatic detection and classification of the vascular bifurcations along the Circle of Willis. Med. Image Anal. 2023, 89, 102919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bor, A.S.; Velthuis, B.K.; Majoie, C.B.; Rinkel, G.J. Configuration of intracranial arteries and development of aneurysms: A follow-up study. Neurology 2008, 70, 700–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.J.; Gao, B.L.; Li, T.X.; Hao, W.L.; Wu, S.S.; Zhang, D.H. Association of Basilar Bifurcation Aneurysms with Age, Sex, and Bifurcation Geometry. Stroke 2018, 49, 1371–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baharoglu, M.I.; Lauric, A.; Safain, M.G.; Hippelheuser, J.; Wu, C.; Malek, A.M. Widening and high inclination of the middle cerebral artery bifurcation are associated with presence of aneurysms. Stroke 2014, 45, 2649–2655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhar, S.; Tremmel, M.; Mocco, J.; Kim, M.; Yamamoto, J.; Siddiqui, A.H.; Hopkins, L.N.; Meng, H. Morphology parameters for intracranial aneurysm rupture risk assessment. Neurosurgery 2008, 63, 185–196; discussion 196–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocco, J.; Brown, R.D., Jr.; Torner, J.C.; Capuano, A.W.; Fargen, K.M.; Raghavan, M.L.; Piepgras, D.G.; Meissner, I.; Huston, J., III. International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms, I. Aneurysm Morphology and Prediction of Rupture: An International Study of Unruptured Intracranial Aneurysms Analysis. Neurosurgery 2018, 82, 491–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Noto, T.; Marie, G.; Tourbier, S.; Aleman-Gomez, Y.; Esteban, O.; Saliou, G.; Cuadra, M.B.; Hagmann, P.; Richiardi, J. Towards Automated Brain Aneurysm Detection in TOF-MRA: Open Data, Weak Labels, and Anatomical Knowledge. Neuroinformatics 2023, 21, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Nys, C.M.; Liang, E.S.; Prior, M.; Woodruff, M.A.; Novak, J.I.; Murphy, A.R.; Li, Z.Y.; Winter, C.D.; Allenby, M.C. Time-of-Flight MRA of Intracranial Aneurysms with Interval Surveillance, Clinical Segmentation and Annotations. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Kim, Y.C.; Khoo, M.C.; Ward, S.L.; Nayak, K.S. Dynamic 3-D MR Visualization and Detection of Upper Airway Obstruction During Sleep Using Region-Growing Segmentation. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2016, 63, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, H.S.; Oh, J.; Kim, Y.C. Assessing Machine Learning Models for Predicting Age with Intracranial Vessel Tortuosity and Thickness Information. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Walt, S.; Schönberger, J.L.; Nunez-Iglesias, J.; Boulogne, F.; Warner, J.D.; Yager, N.; Gouillart, E.; Yu, T. scikit-image: Image processing in Python. PeerJ 2014, 2, e453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.O.; Kim, Y.C. Effects of Path-Finding Algorithms on the Labeling of the Centerlines of Circle of Willis Arteries. Tomography 2023, 9, 1423–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.O.; Kim, Y.C. An Improved Path-Finding Method for the Tracking of Centerlines of Tortuous Internal Carotid Arteries in MR Angiography. J. Imaging 2024, 10, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yushkevich, P.A.; Piven, J.; Hazlett, H.C.; Smith, R.G.; Ho, S.; Gee, J.C.; Gerig, G. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: Significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage 2006, 31, 1116–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L. Pytorch: An imperative style, high-performance deep learning library. In Proceedings of the 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 3D-CNN-PyTorch: PyTorch Implementation for 3dCNNs for Medical Images. Available online: https://github.com/xmuyzz/3D-CNN-PyTorch (accessed on 13 November 2025).

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26 June–1 July 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, G.; Liu, Z.; Van Der Maaten, L.; Weinberger, K.Q. Densely connected convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 4700–4708. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q. Efficientnet: Rethinking model scaling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 10–15 June 2019; pp. 6105–6114. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, X.; Lin, M.; Sun, J. Shufflenet: An extremely efficient convolutional neural network for mobile devices. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 6848–6856. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Garcia, F.; Sparks, R.; Ourselin, S. TorchIO: A Python library for efficient loading, preprocessing, augmentation and patch-based sampling of medical images in deep learning. Comput. Methods Programs Biomed. 2021, 208, 106236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V. Scikit-learn: Machine learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, J.; Kim, Y.-C. Software design for quantitative analysis of geometric features of the vessels with cerebral aneurysms in MR angiography 3D images. J. Korean Inst. Next Gener. Comput. 2024, 20, 56–65. [Google Scholar]

- Summerfield, M. Rapid GUI Programming with Python and Qt: The Definitive Guide to PyQt Programming; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nunez-Iglesias, J.; Blanch, A.J.; Looker, O.; Dixon, M.W.; Tilley, L. A new Python library to analyse skeleton images confirms malaria parasite remodelling of the red blood cell membrane skeleton. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nader, R.; Autrusseau, F.; L’Allinec, V.; Bourcier, R. Building a Synthetic Vascular Model: Evaluation in an Intracranial Aneurysms Detection Scenario. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2024, 44, 1347–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, K.; Gao, L.; Lu, Z.; Li, C.; Xi, Q.; Zhang, F.; Sun, J.; Lin, T.; Sui, J.; Ni, X. Inpainting the metal artifact region in MRI images by using generative adversarial networks with gated convolution. Med. Phys. 2022, 49, 6424–6438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alblas, D.; Vos, I.N.; Lipplaa, M.M.; Brune, C.; van der Schaaf, I.C.; Velthuis, M.R.E.; Velthuis, B.K.; Kuijf, H.J.; Ruigrok, Y.M.; Wolterink, J.M. Deep-learning-based extraction of circle of Willis topology with anatomical priors. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 31630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Dataset | Label Type | The Number of Subjects | The Number of 3D Patches |

|---|---|---|---|

| LUH | Aneurysm | 58 | 59 |

| Non-aneurysm | 100 | 469 | |

| RBWH | Aneurysm | 46 | 57 |

| Total | 204 | 585 |

| Augmentation Method | The Number of Training Samples |

|---|---|

| (1) No augmentation | 336 |

| (2) Augmentation using flip | 672 |

| (3) Augmentation using translation | 672 |

| (4) Augmentation using flip and translation | 1344 |

| Learning Rate | Metric | Model | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DenseNet121 | DenseNet169 | EfficientNet | MobileNet | ResNetV2_18 | ResNetV2_34 | ResNetV2_50 | ShuffleNet | ||

| 0.001 | PR-AUC | 0.306 (0.123) | 0.311 (0.060) | 0.216 (0.051) | 0.250 (0.070) | 0.393 (0.106) | 0.347 (0.085) | 0.357 (0.095) | 0.373 (0.114) |

| 0.0005 | PR-AUC | 0.332 (0.108) | 0.315 (0.092) | 0.217 (0.058) | 0.258 (0.078) | 0.351 (0.117) | 0.331 (0.093) | 0.349 (0.096) | 0.347 (0.119) |

| 0.0001 | PR-AUC | 0.334 (0.107) | 0.285 (0.129) | 0.207 (0.045) | 0.258 (0.098) | 0.270 (0.084) | 0.242 (0.068) | 0.310 (0.104) | 0.313 (0.087) |

| Model | Augmentation Method | Average per Epoch Time in Training (Seconds) |

|---|---|---|

| ResNetV2_18 | No augment | 3.48 |

| Flip | 5.16 | |

| Translation | 5.17 | |

| Flip and translation | 8.62 | |

| ResNetV2_50 | No augment | 5.10 |

| Flip | 8.05 | |

| Translation | 8.06 | |

| Flip and translation | 13.87 | |

| ShuffleNet | No augment | 1.09 |

| Flip | 2.00 | |

| Translation | 2.01 | |

| Flip and translation | 3.82 |

| Model | Augmentation Method | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-score | ROC-AUC | PR-AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNetV2_18 | No augment | 0.682 (0.105) | 0.338 (0.094) | 0.629 (0.180) | 0.425 (0.097) | 0.695 (0.072) | 0.411 (0.106) |

| Flip | 0.693 (0.115) | 0.363 (0.137) | 0.575 (0.161) | 0.417 (0.083) | 0.708 (0.084) | 0.451 (0.097) | |

| Translation | 0.698 (0.099) | 0.364 (0.118) | 0.655 (0.122) | 0.454 (0.098) | 0.735 (0.076) | 0.472 (0.116) | |

| Flip and translation | 0.656 (0.154) | 0.365 (0.200) | 0.584 (0.185) | 0.400 (0.119) | 0.705 (0.085) | 0.470 (0.139) | |

| ResNetV2_50 | No augment | 0.642 (0.127) | 0.296 (0.112) | 0.511 (0.157) | 0.352 (0.083) | 0.629 (0.094) | 0.349 (0.109) |

| Flip | 0.629 (0.117) | 0.292 (0.089) | 0.595 (0.160) | 0.376 (0.082) | 0.667 (0.072) | 0.386 (0.090) | |

| Translation | 0.663 (0.098) | 0.316 (0.142) | 0.497 (0.180) | 0.348 (0.098) | 0.666 (0.065) | 0.395 (0.088) | |

| Flip and translation | 0.664 (0.103) | 0.326 (0.119) | 0.573 (0.171) | 0.389 (0.080) | 0.697 (0.072) | 0.427 (0.096) | |

| ShuffleNet | No augment | 0.608 (0.149) | 0.262 (0.125) | 0.574 (0.232) | 0.344 (0.139) | 0.639 (0.131) | 0.382 (0.139) |

| Flip | 0.619 (0.125) | 0.270 (0.092) | 0.528 (0.181) | 0.341 (0.097) | 0.626 (0.104) | 0.355 (0.099) | |

| Translation | 0.658 (0.133) | 0.314 (0.105) | 0.604 (0.205) | 0.396 (0.125) | 0.692 (0.101) | 0.430 (0.140) | |

| Flip and translation | 0.663 (0.101) | 0.307 (0.112) | 0.542 (0.154) | 0.375 (0.107) | 0.674 (0.079) | 0.429 (0.109) |

| Model A | Model B | Model A PR-AUC | Model B PR-AUC | p-Value | 95% Confidence Interval |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ResNetV2_18 (translation) | ResNetV2_50 (flip and translation) | 0.472 (0.116) | 0.427 (0.096) | 0.102 | [−0.010, 0.100] |

| ResNetV2_50 (flip and translation) | ShuffleNet (translation) | 0.427 (0.096) | 0.430 (0.140) | 0.930 | [−0.064, 0.059] |

| ShuffleNet (translation) | ResNetV2_18 (translation) | 0.430 (0.140) | 0.472 (0.116) | 0.194 | [−0.023, 0.108] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Oh, J.-M.; Yu, C.-U.; Kim, J.-W.; Lee, H.; Lee, Y.; Kim, Y.-C. A 3D CNN Prediction of Cerebral Aneurysm in the Bifurcation Region of Interest in Magnetic Resonance Angiography. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 13004. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413004

Oh J-M, Yu C-U, Kim J-W, Lee H, Lee Y, Kim Y-C. A 3D CNN Prediction of Cerebral Aneurysm in the Bifurcation Region of Interest in Magnetic Resonance Angiography. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):13004. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413004

Chicago/Turabian StyleOh, Jeong-Min, Chae-Un Yu, Ji-Woo Kim, Hyeongjae Lee, Yunsung Lee, and Yoon-Chul Kim. 2025. "A 3D CNN Prediction of Cerebral Aneurysm in the Bifurcation Region of Interest in Magnetic Resonance Angiography" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 13004. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413004

APA StyleOh, J.-M., Yu, C.-U., Kim, J.-W., Lee, H., Lee, Y., & Kim, Y.-C. (2025). A 3D CNN Prediction of Cerebral Aneurysm in the Bifurcation Region of Interest in Magnetic Resonance Angiography. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 13004. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152413004