Rock Mass Strength Characterisation from Field and Laboratory: A Comparative Study on Carbonate Rocks from the Larzac Plateau

Abstract

1. Introduction

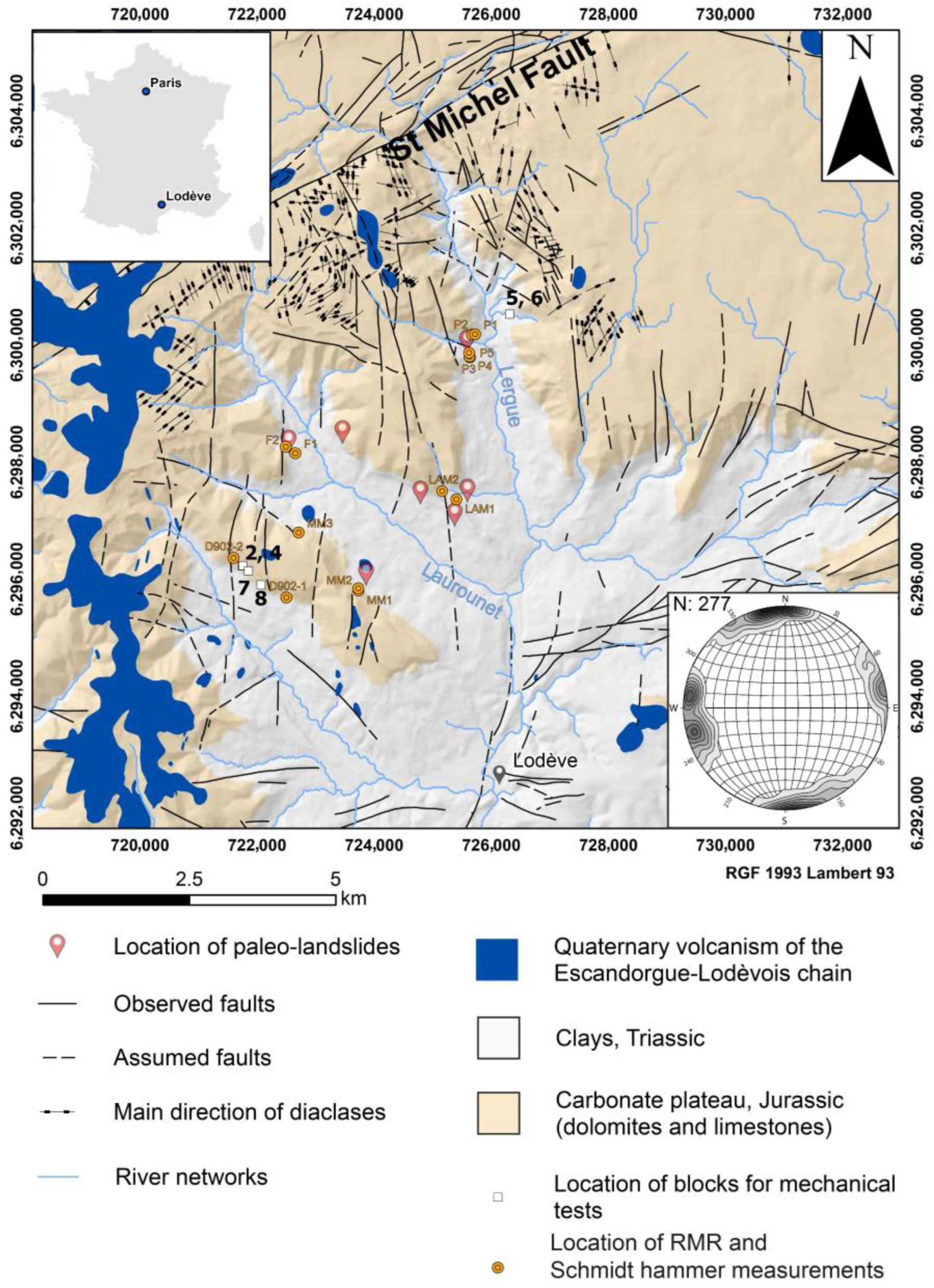

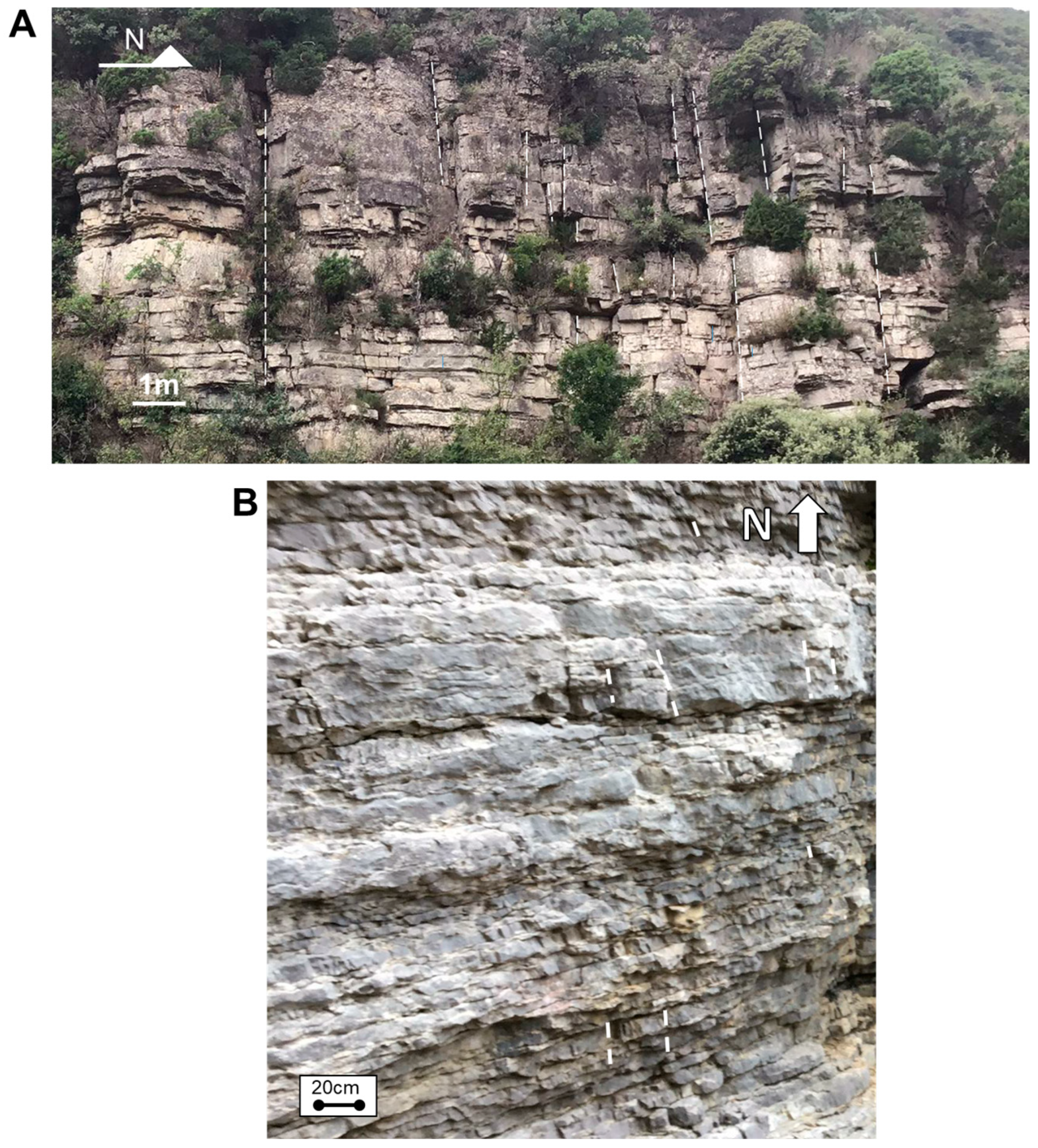

2. Geological Setting of the Larzac Plateau

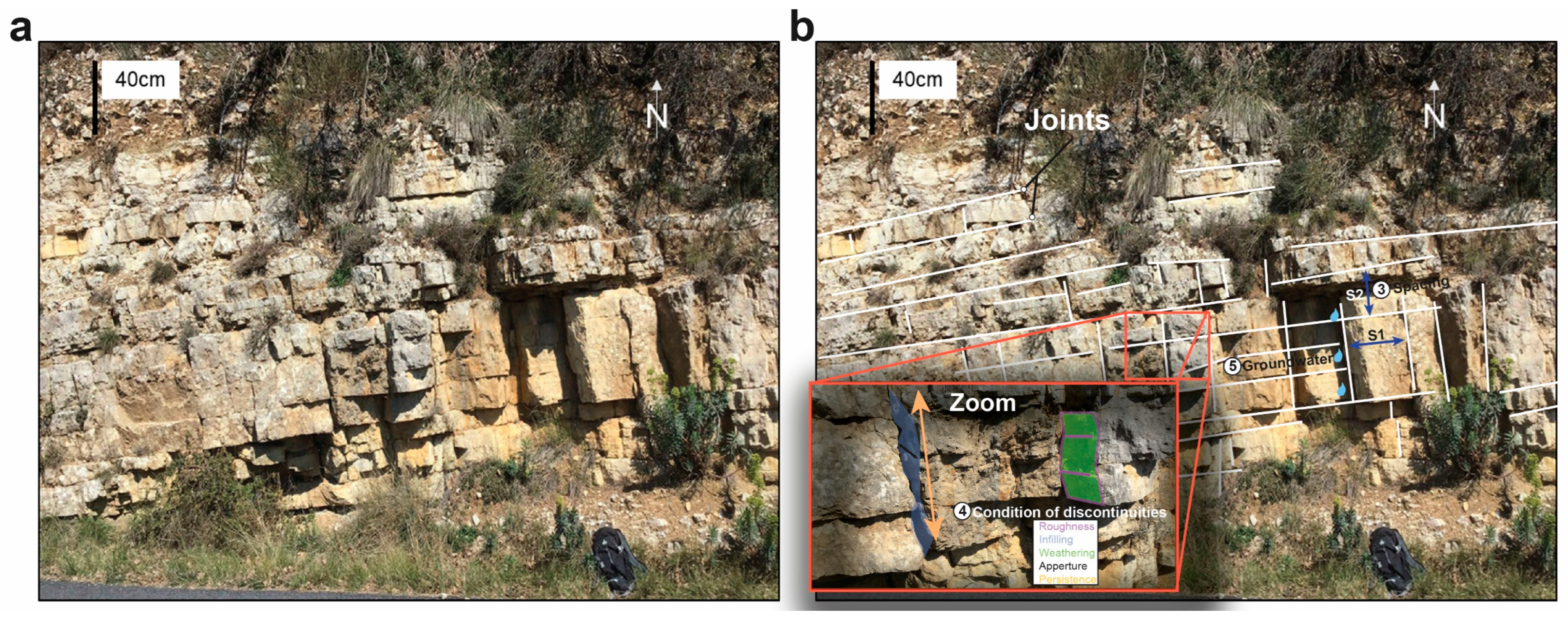

3. Rock Mass Strength from Field Investigations

3.1. Schmidt Hammer Measurements

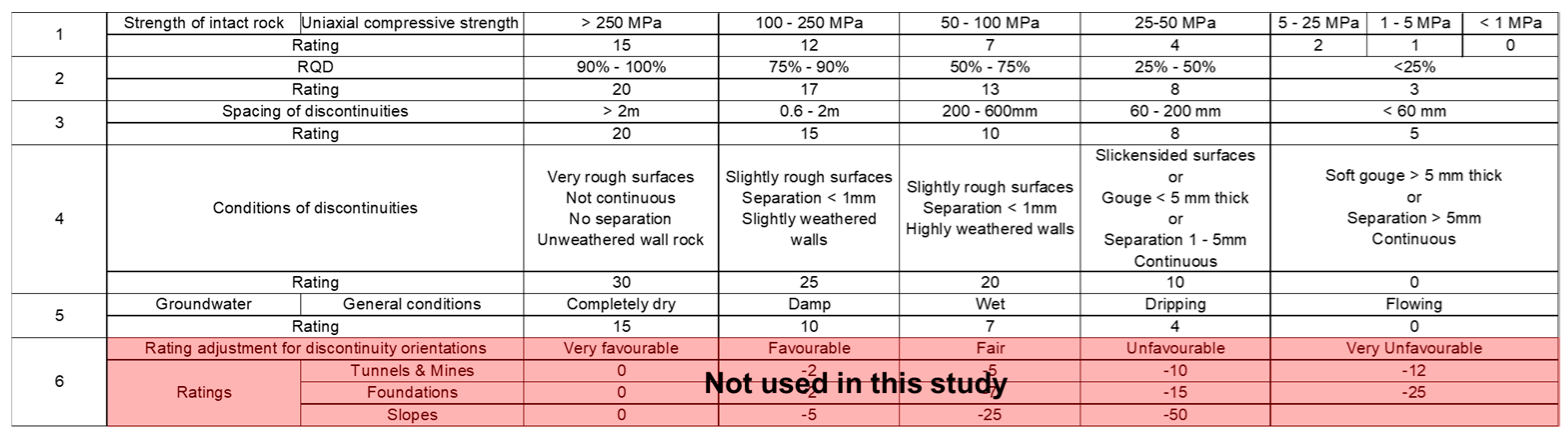

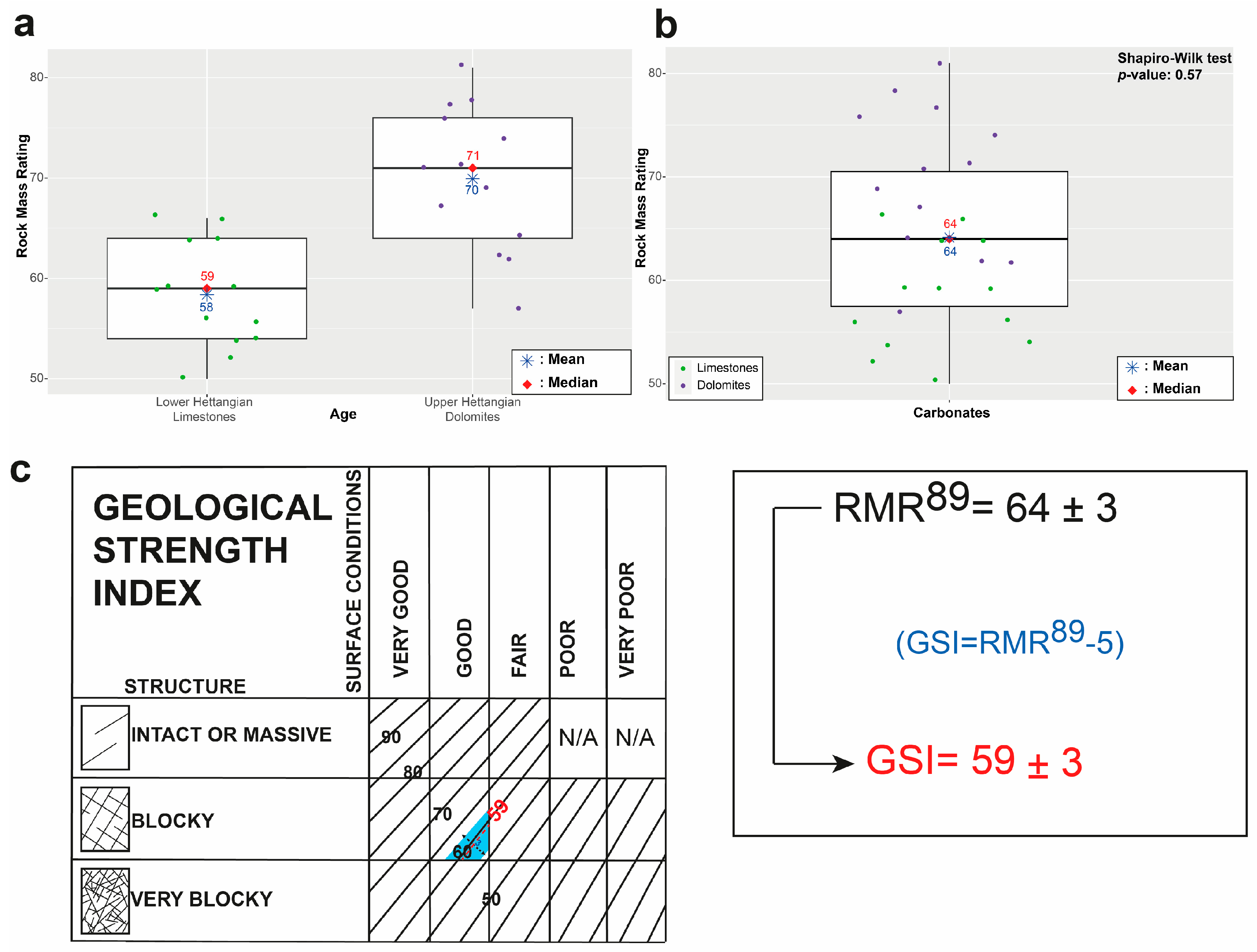

3.2. Rock Mass Classifications

3.3. Field Characterisation: Schmidt Hammer and the RMR Approach

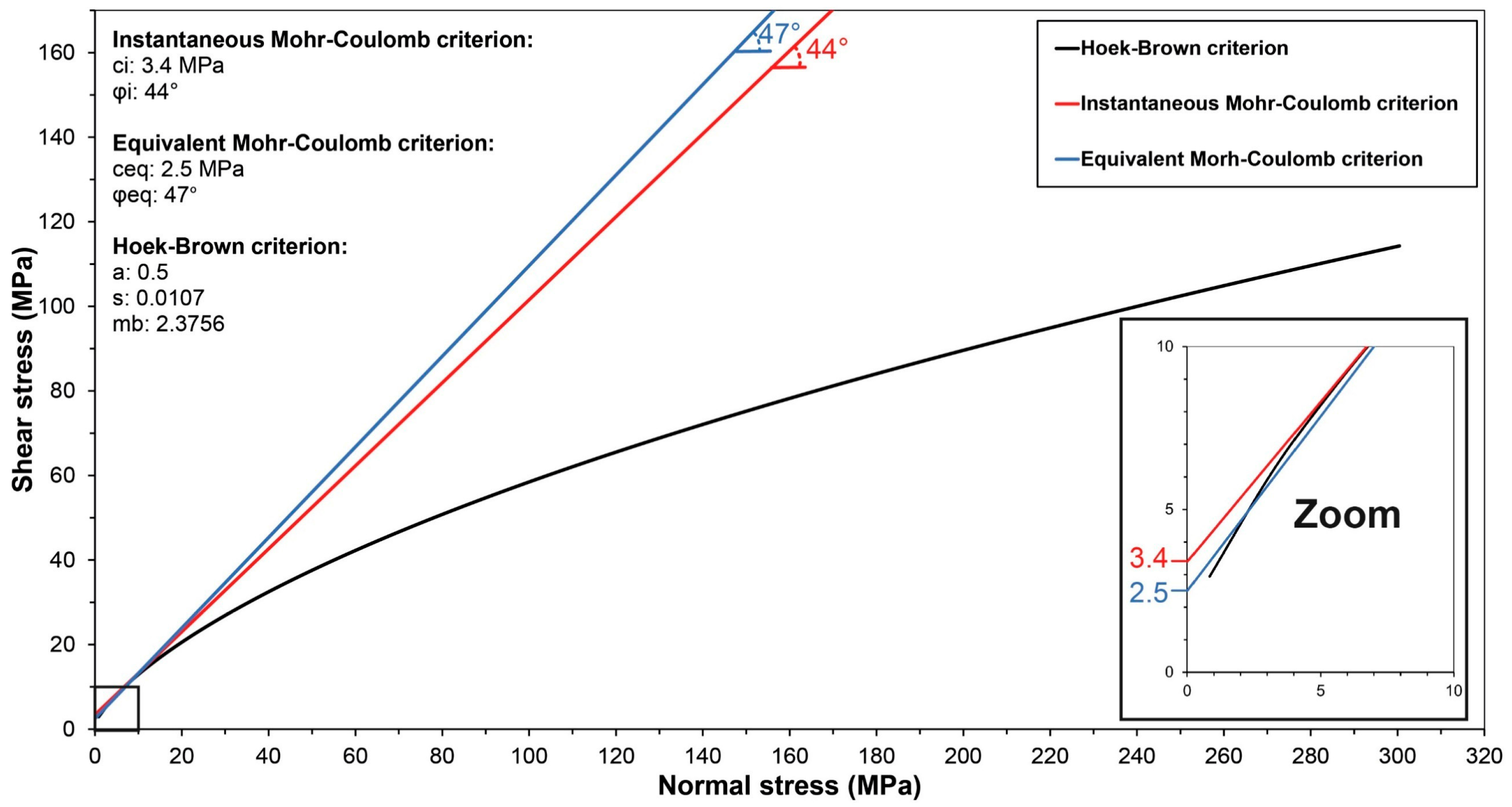

3.4. Mohr–Coulomb Strength Properties from RMR

4. Rock Mass Strength from the Laboratory

4.1. Laboratory Measurements of Rock Strength

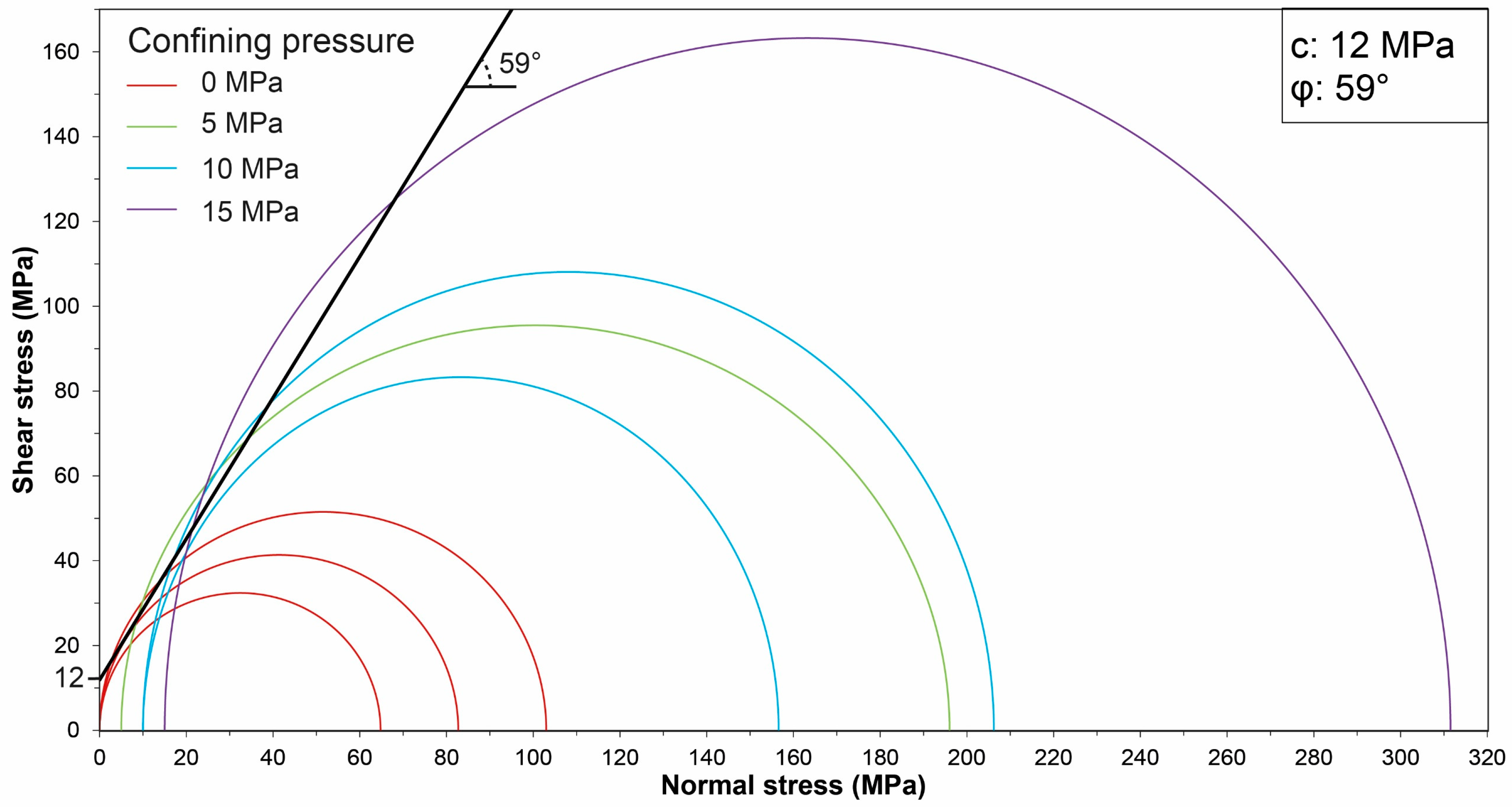

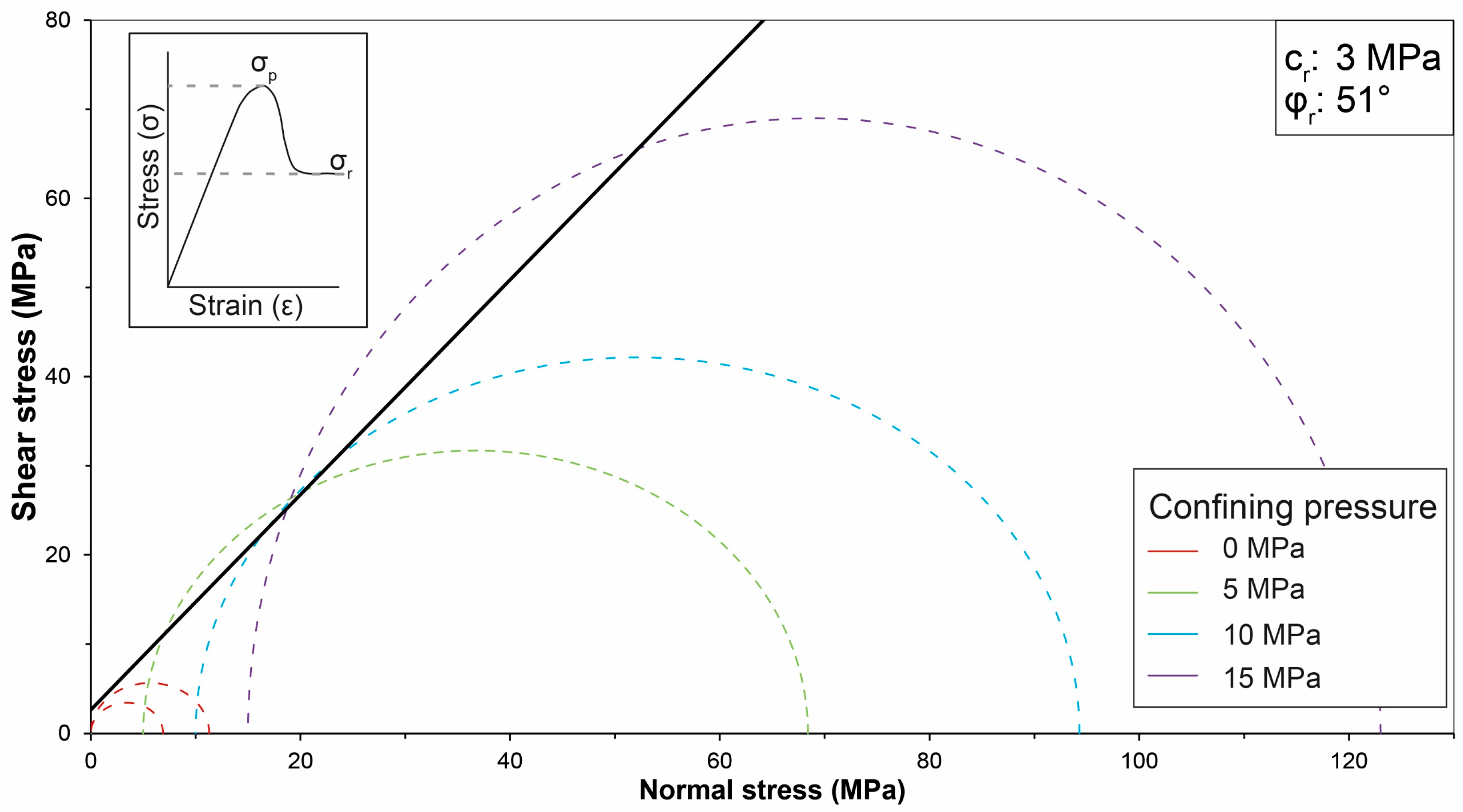

4.2. Mohr–Coulomb Strength Properties from Laboratory Tests

5. Discussion

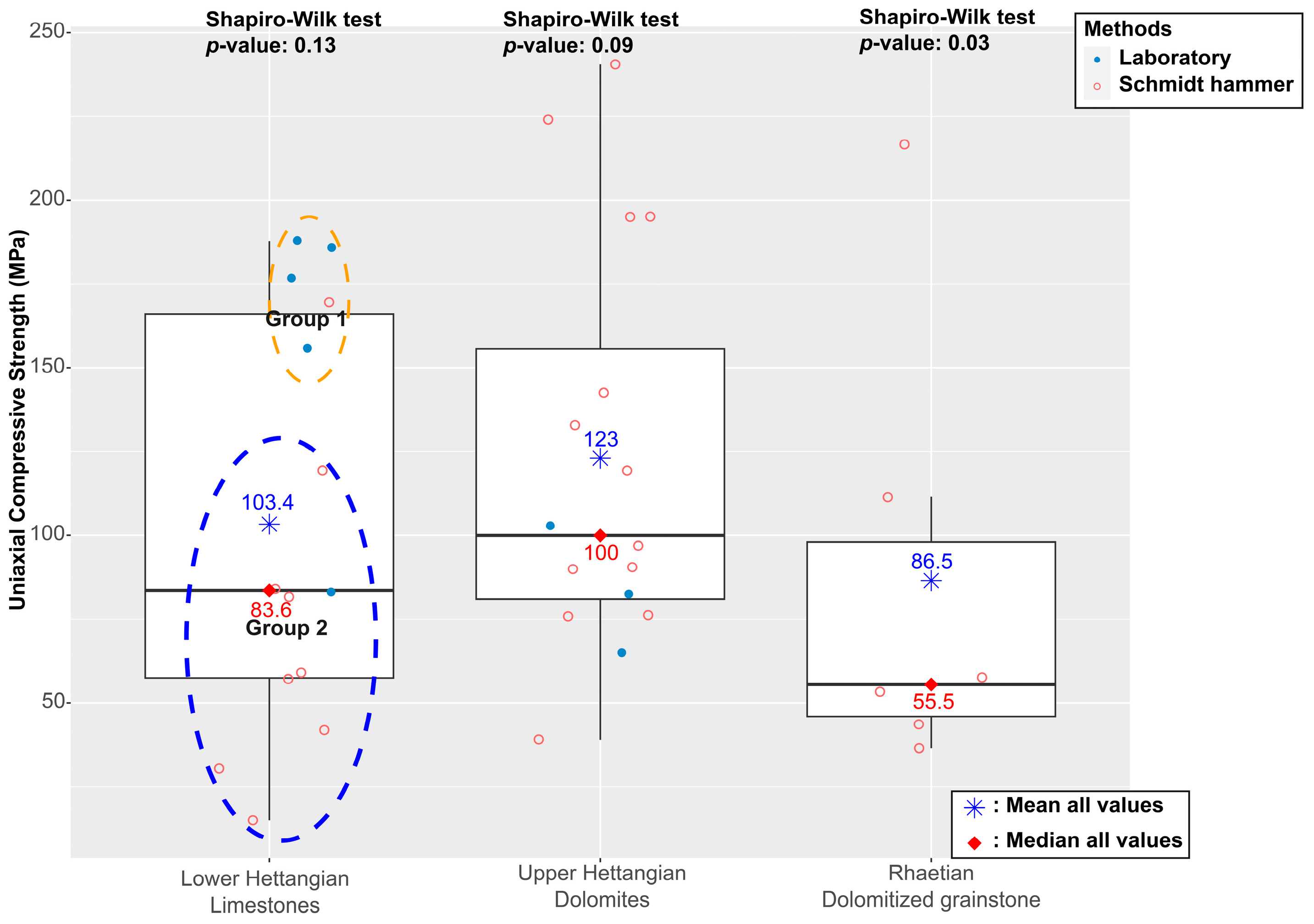

5.1. Comparison of UCS Value Between Laboratory and In Situ Measurements

5.2. Comparison of Mohr–Coulomb Parameters from the Laboratory and Derived from In Situ Measurements

- The volume effect, which is statistically linked to the increase in defects when considering a larger volume of rock.

- The surface effect, which is a result of imperfections during sample preparation or due to the reaction of rock minerals on the free surface.

- The mechanical effect, which is related to the amount of deformation energy present during compression.

5.3. Young’s Modulus

| Field | ||

|---|---|---|

| References | Formulas | Em (GPa) |

| [66] | 28.4 | |

| [67] | 22.6 | |

| [14] | 17.8 | |

| [67] | 20.3 | |

| [65] | 9.4 | |

| [68] | 20.2 | |

| Laboratory | ||

| Block Numbers | Sample name | E (GPa) |

| 4 | R 1999 Rc | 20.5 |

| 8 | Dolomie 1 | 9.7 |

| 8 | Dolomie 2 | 16.8 |

| 5 | R 2003 Rc | 16.5 |

| 5 | R 2007 Rc | 24.7 |

| 6 | R 2008 Rc | 27 |

| 6 | R 2009 Rc | 25.7 |

| 6 | R 2013 Rc | 25.1 |

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- Uniaxial compressive strength of the intact rock (see Section 3.1).

- The second parameter is the Rock Quality Designation (RQD) established by the following formulas [46]:andRQD = 115 − 3.3Jvwhere Jv is the volumetric joint count, and S1, S2, and S3 are the spacings in meters of each joint constituting the rock mass.Jv = 1/S1 + 1/S2 + 1/S3

- The third parameter is the spacing of discontinuities.

- The fourth parameter consists of several aspects and describes the conditions of the discontinuities (roughness, length, continuity, aperture, moisture, infilling, alteration).

- The fifth parameter is the circulation of water through the fractures (inlets and outlets, pressure). For scoring, it is determined whether the fracture is wet or dry.

- The sixth parameter is an adjustment for joint orientation that can be applied.

References

- Wyllie, D.C.; Norrish, N.I. Landslides: Investigation and Mitigation. Chapter 14—Rock Strength Properties and Their Measurement. In Transportation Research Board Special Report; Transportation Research Board: Washington, DC, USA, 1996; pp. 372–390. ISBN 978-0-309-06208-4. [Google Scholar]

- Kayabasi, A.; Gokceoglu, C.; Ercanoglu, M. Estimating the Deformation Modulus of Rock Masses: A Comparative Study. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2003, 40, 55–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, D.; Wolter, A. A Critical Review of Rock Slope Failure Mechanisms: The Importance of Structural Geology. J. Struct. Geol. 2015, 74, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stead, D.; Eberhardt, E.; Coggan, J.S. Developments in the Characterization of Complex Rock Slope Deformation and Failure Using Numerical Modelling Techniques. Eng. Geol. 2006, 83, 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brideau, M.-A.; Yan, M.; Stead, D. The Role of Tectonic Damage and Brittle Rock Fracture in the Development of Large Rock Slope Failures. Geomorphology 2009, 103, 30–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, R.; Xu, C.; Xuan, Z.; Zhou, J.; Du, K. Joint Characterization and Stability Analysis: Measurement Techniques and Engineering Implications. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stacey, T.R. Presidential Address: Rock Engineering—Good Design or Good Judgement? Rock Eng. 2003, 103, 411–421. [Google Scholar]

- He, J. A Case Review of the Deformation Modulus of Rock Mass: Scale Effect. In Scale Effects in Rock Masses 93; CRC Press: Balkema, Rotterdam, 1993; pp. 87–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bieniawski, Z.T. Engineering Classification of Jointed Rock Masses. Trans. S. Afr. Inst. Civ. Eng. 1973, 15, 335–344. [Google Scholar]

- Bieniawski, Z.T. Rock Mass Classification in Rock Engineering, Symposium Proceedings of Exploration for Rock Engineering; A. A. Balkema: Cape Town, South Africa, 1976; Volume 1, pp. 97–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bieniawski, Z.T. Classification of Rock Masses for Engineering: The RMR System and Future Trends. In Rock Testing and Site Characterization; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 553–573. ISBN 978-0-08-042066-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hoek, E. Strength of Rock and Rock Masses. ISRM News J. 1994, 2, 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Hoek, E.; Kaiser, P.K.; Bawden, W.F. Support of Underground Excavations in Hard Rock; A.A. Balkema: Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Brookfield, VT, USA, 1995; ISBN 978-90-5410-186-4. [Google Scholar]

- Hoek, E.; Brown, E.T. Practical Estimates of Rock Mass Strength. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 1997, 34, 1165–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, B.H.G.; Brown, E.T. Rock Strength and Deformability, 3rd ed.; Brady, B.H.G., Brown, E.T., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2006; ISBN 978-1-4020-2116-9. [Google Scholar]

- Pantelidis, L. Rock Slope Stability Assessment through Rock Mass Classification Systems. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2009, 46, 315–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashemi, M.; Moghaddas, S.; Ajalloeian, R. Application of Rock Mass Characterization for Determining the Mechanical Properties of Rock Mass: A Comparative Study. Rock Mech. Rock Eng. 2010, 43, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.C.S.; Remer, J.S.; Wilson, C.R.; Witherspoon, P.A. Porous Media Equivalents for Networks of Discontinuous Fractures. Water Resour. Res. 1982, 18, 645–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, K.-B.; Jing, L. Numerical Determination of the Equivalent Elastic Compliance Tensor for Fractured Rock Masses Using the Distinct Element Method. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2003, 40, 795–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, M. Determination of Representative Elementary Volume (REV) for Jointed Rock Masses Exhibiting Scale-Dependent Behavior: A Numerical Investigation. Int. J. Geo-Eng. 2021, 12, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniawski, Z.T.; Van Heerden, W.L. The Significance of in Situ Tests on Large Rock Specimens. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1975, 12, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, R.E. Introduction to Rock Mechanics, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bandis, S.; Lumsden, A.C.; Barton, N.R. Experimental Studies of Scale Effects on the Shear Behaviour of Rock Joints. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1981, 18, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandis, S.C. Scale Effects in the Strength and Deformability of Rocks and Rock Joints. In Proceedings of the First International Workshop on Scale Effects, in Rock Masses, Loen, Norway, 7–8 June 1990; Balkema (AA): Cape Town, South Africa, 1990; pp. 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Barton, N. Scale Effects or Sampling Bias. In Proceeding of the First International Workshop on Scale Effects in Rock Masses, Loen, Norway, 7–8 June 1990; Balkema (AA): Cape Town, South Africa, 1990; pp. 31–54. [Google Scholar]

- Fadeev, A.B. Scale Effect of Rock Strength. In Proceeding of the First International Workshop on Scale Effects in Rock Masses, Loen, Norway, 7–8 June 1990; Balkema (AA): Cape Town, South Africa, 1990; pp. 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshinaka, R.; Osada, M.; Park, H.; Sasaki, T.; Sasaki, K. Practical Determination of Mechanical Design Parameters of Intact Rock Considering Scale Effect. Eng. Geol. 2008, 96, 173–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, E.; Brown, E.T. Empirical Strength Criterion for Rock Masses. J. Geotech. Eng. Div. 1980, 106, 1013–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, K. Scale Effect on Shear Strength of Sedimentary Soft Rocks Observed in Triaxial Compression Test (Influence of Potential Joints). In Proceedings of the 36th National Conference of the Japanese Geotechnical Society, Kumamoto, Japan, 11–13 July 2001; pp. 597–598. [Google Scholar]

- Mouzannar, H. Caractérisation de La Résistance Au Cisaillement et Comportement Des Interfaces Entre Béton et Fondation Rocheuse Des Structures Hydrauliques. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Lyon, Lyon, France, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chemenda, A.I.; Bois, T.; Bouissou, S.; Tric, E. Numerical Modelling of the Gravity-Induced Destabilization of a Slope: The Example of the La Clapière Landslide, Southern France. Geomorphology 2009, 109, 86–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasc-Barbier, M.; Merrien-Soukatchoff, V.; Krzewinski, V.; Azemard, P.; Genois, J.-L. Assessment of the Influence of Natural Thermal Cycles on Dolomitic Limestone Rock Columns: A 10-Year Monitoring Study. Geomorphology 2024, 464, 109353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkharrat, K.; Homberg, C.; Lafuerza, S.; Loget, N.; Gasc-Barbier, M.; Gautier, S. Paleo-Landslides on the Meridional Border of the Larzac Plateau (France): Recognition and Predisposing/Triggering Factors. Landslides 2025, 22, 1475–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkharrat, K.; Homberg, C.; Lafuerza, S.; Loget, N.; Gasc-Barbier, M.; Gautier, S. Study Cases of Complex Paleo-Landslides in the South of France. Landslides 2025, 22, 773–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, N.; Choubey, V. The Shear Strength of Rock Joints in Theory and Practice. Rock Mech. 1977, 10, 1–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alabouvette, B.; Arrondeau, J.P.; Aubague, M.; Bodeur, Y.; Dubois, P.; Mattei, J.; Paloc, J.; Rançon, J.P. Notice Explicative de la Feuille le Caylar à 1/50000; BRGM: Orléans, France, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ambert, M.; Ambert, P. Karstification Des Plateaux et Encaissement Des Vallées Au Cours Du Néogène et Du Quaternaire Dans Les Grands Causses Méridionaux (Larzac, Blandas). Géologie Fr. 1995, 4, 37–50. [Google Scholar]

- Lemonnier, N.; Homberg, C.; Roche, V.; Rocher, M.; Bouiller, A.M.; Schnyder, J. Microstructures of Bedding-Parallel Faults under Multistage Deformation: Examples from the Southeast Basin of France. J. Struct. Geol. 2020, 140, 104138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, A. (Ed.) The ISRM Suggested Methods for Rock Characterization, Testing and Monitoring: 2007–2014; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2009; ISBN 978-3-319-07712-3. [Google Scholar]

- Aydin, A.; Basu, A. The Schmidt Hammer in Rock Material Characterization. Eng. Geol. 2005, 81, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, O.; Reches, Z.; Roegiers, J.-C. Evaluation of Mechanical Rock Properties Using a Schmidt Hammer. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2000, 37, 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, S. Evaluation of Simple Methods for Assessing the Uniaxial Compressive Strength of Rock. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2001, 38, 981–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniawski, Z.T. Engineering Rock Mass Classification; John Wiley & Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, B.; Goel, R.K. Chapter-6—Rock Mass Rating (RMR). In Rock Mass Classification; Singh, B., Goel, R.K., Eds.; Elsevier Science Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1999; pp. 34–46. ISBN 978-0-08-043013-3. [Google Scholar]

- Deere, D.U.; Hendron, A.J.; Patton, F.D.; Cording, E.J. Design of Surface and near Surface Construction in Rock. In Proceedings of the the 8th U.S. Symposium on Rock Mechanics (USRMS), Minneapolis, MN, USA, 15–17 September 1966; American Rock Mechanics Association: Alexandria, VA, USA, 1967; pp. 237–303. [Google Scholar]

- Palmstrom, A. Measurements of and Correlations between Block Size and Rock Quality Designation (RQD). Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2005, 20, 362–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, E.; Brown, E.T. The Hoek–Brown Failure Criterion and GSI—2018 Edition. J. Rock Mech. Geotech. Eng. 2019, 11, 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, M.; Kaiser, P.K.; Uno, H.; Tasaka, Y.; Minami, M. Estimation of Rock Mass Deformation Modulus and Strength of Jointed Hard Rock Masses Using the GSI System. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2004, 41, 3–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertuzzi, R.; Douglas, K.; Mostyn, G. Comparison of Quantified and Chart GSI for Four Rock Masses. Eng. Geol. 2016, 202, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morelli, G.L. Alternative Quantification of the Geological Strength Index Chart for Jointed Rocks. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2017, 35, 2803–2816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, E.; Carter, T.G.; Diederichs, M.S. Quantification of the Geological Strength Index Chart. In Proceedings of the 47th US Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium, San Francisco, CA, USA, 23–26 June 2013; Volume 3, pp. 1757–1764. [Google Scholar]

- Marinos, V.; Marinos, P.; Hoek, E. The Geological Strength Index: Applications and Limitations. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2005, 64, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balmer, G. A General Analytical Solution for Mohr’s Envelope. Proc. Am. Soc. Test Mater. 1952, 52, 1260–1271. [Google Scholar]

- Hoek, E. Estimating Mohr-Coulomb Friction and Cohesion Values from the Hoek-Brown Failure Criterion. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1990, 27, 227–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoek, E.; Carranza-Torres, C.; Corkum, B. Hoek-Brown Failure Criterion—2002 Edition, Proceedings of the Narms-Tac Conference, Toronto, ON, Canada, 7–10 July 2002; University of Toronto Press: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2002; pp. 267–273. [Google Scholar]

- Gasc Barbier, M.; Wassermann, J. Etude En Laboratoire de l’anisotropie Des Roches Par Méthode Ultrasonique: Application Au Gneiss de Valabres (Alpes-Maritimes). Bull. Lab. Ponts Chaussées 2013, 139–153. [Google Scholar]

- ASTM D4543-08; Standard Practices for Preparing Rock Core as Cylindrical Test Specimens and Verifying Conformance to Dimensional and Shape Tolerances. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2008.

- ASTM D7012-10; Standard Test Method for Compressive Strength and Elastic Moduli of Intact Rock Core Specimens Under Varying States of Stress and Temperatures. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2008. [CrossRef]

- Abd El Aal, A.K.; Ali, S.H.; Wahid, A.; Bashir, Y.; Shoukat, N. The Influence of Crystal Size of Dolomite on Engineering Properties: A Case Study from the Rus Formation, Dammam Dome, Eastern Saudi Arabia. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2024, 83, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Greco, O.; Ferrero, A.M.; Oggeri, C. Experimental and Analytical Interpretation of the Behaviour of Laboratory Tests on Composite Specimens. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. Geomech. Abstr. 1993, 30, 1539–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinos, P.; Hoek, E. Estimating the Geotechnical Properties of Heterogeneous Rock Masses Such as Flysch. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2001, 60, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heuze, E. Scale Effects in the Determination of Rock Mass Strength and Deformability. Rock Mech. 1980, 12, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L. Evaluation of Rock Mass Deformability Using Empirical Methods—A Review. Undergr. Space 2017, 2, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panthee, S.; Singh, P.K.; Kainthola, A.; Das, R.; Singh, T.N. Comparative Study of the Deformation Modulus of Rock Mass. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2018, 77, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokceoglu, C.; Sonmez, H.; Kayabasi, A. Predicting the Deformation Moduli of Rock Masses. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 2003, 40, 701–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bieniawski, Z.T. Determining Rock Mass Deformability: Experience from Case Histories. Int. J. Rock Mech. Min. Sci. 1978, 15, 237–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serafim, J.L.; Pereira, J.P. Considerations on the Geomechanical Classification of Bieniawski. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Engineering Geology and Underground Openings, Lisbon, Portugual, 5–8 September 1983; pp. 1133–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Galera, J.M.; Alvarez, M.; Bieniawski, Z.T. Evaluation of the Deformation Modulus of Rock Masses: Comparison of Pressuremeter and Dilatometer Tests with RMR Prediction. In Proceedings of the ISP5-PRESSIO 2005 International Symposium, Paris, France, 22–24 August 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Hatzor, Y.; Zur, A.; Mimran, Y. Microstructure Effects on Microcracking and Brittle Failure of Dolomites. Tectonophysics 1997, 281, 141–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Site | Lithology | Age | Hammer Rebound R | UCS/σc In Situ (MPa) | RMR Rating | GSI Rating | Lat° | Long° |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P1 | L | EH | 57 | 119.5 | 64; 64 | 59; 59 | 43.800262 | 3.319989 |

| P3 | L | LH | 52 | 84 | 56; 59; 52; 56 | 51; 54; 47; 51 | 43.796455 | 3.318871 |

| P2 | D | LH | 57 | 119.5 | 78; 76; 81 | 73; 71; 76 | 43.800203 | 3.319339 |

| LAM1 | L | EH | 62; 42 | 169.5; 41.8 | 59; 66 | 54; 61 | 43.774900 | 3.315883 |

| MM2 | L | EH | 27.5 | 15 | 54; 50; 54 | 49; 45; 49 | 43.761275 | 3.295003 |

| F1 | L | EH | 51.5; 47; 37.5 | 81.5; 59; 30.5 | 66; 59 | 61; 54 | 43.782092 | 3.281767 |

| P4 | D | LH | 50.5; 53 | 76; 90 | 69; 74 | 64; 69 | 43.796853 | 3.318786 |

| P5 | D | LH | 54; 59.5; 50.5 | 97; 142.5; 76 | 57; 62 | 52; 57 | 43.797422 | 3.318694 |

| LAM2 | D | LH | 46.5; | 57 | 67; 71 | 62; 66 | 43.776183 | 3.312850 |

| MM1 | D | LH | 64 | 195 | - | - | 43.760942 | 3.295031 |

| MM3 | D | LH | 67; 66 | 240.5; 224 | 64; 62 | 59; 57 | 43.769883 | 3.282386 |

| D902-1 | D | Rhaetian | 42.5 | 43.5 | - | - | 43.759903 | 3.279751 |

| D902-2 | D | LH | 64; 41; 58.5 | 195; 39; 132.7 | 71; 77 | 66; 72 | 43.766025 | 3.268558 |

| F2 | D | EH | 53; 41.5; 45.5 | 90.5; 57.5; 53.5 | - | - | 43.783081 | 3.279728 |

| Other | D | Rhaetian | 40; 56; 65.5 | 36.5; 111.5; 216.5 | - | - | 43.7548252 | 3.7149275 |

| Rating | Calculation | RMR | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | σc | RQD | Spacing | Persistence | Aperture | Roughness | Infilling | Weathering | Groundwater | Jv (m−1) | RQD | |

| D902-2 | 12 | 13 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 15 | 15 | 64 | 71 |

| D902-2 | 12 | 13 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 15 | 15 | 64 | 77 |

| Type of Test | pc (MPa) | σp (MPa) | σr (MPa) | σtb (MPa) | E (GPa) | ν (-) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Late Hettangian Dolomite | Tensile | - | - | - | 6.4 | - | - |

| Tensile | - | - | - | 5.6 | - | - | |

| Tensile | - | - | - | 6.4 | - | - | |

| Compressive | 0 | 103 | - | - | 20.5 | 0.24 | |

| Triaxial | 10 | 146.6 | - | - | 89.4 | 0.25 | |

| Tensile | - | - | - | 7 | - | - | |

| Compressive | 0 | 64.8 | 6.9 | - | 9.7 | 0.21 | |

| Compressive | 0 | 82.7 | 11.3 | - | 16.8 | 0.26 | |

| Triaxial | 5 | 191.6 | 68.4 | - | 24.4 | 0.28 | |

| Triaxial | 10 | 196.2 | 94.3 | - | 19.7 | 0.28 | |

| Triaxial | 15 | 296.5 | 123 | - | 23.8 | 0.27 | |

| Early Hettangian Limestone | Compressive | 0 | 83. | - | - | 16.5 | 0.19 |

| Tensile | - | - | - | 10.9 | - | - | |

| Tensile | - | - | - | 16.4 | - | - | |

| Tensile | - | - | - | 17.2 | - | - | |

| Compressive | 0 | 176.6 | - | - | 24.7 | - | |

| Compressive | 0 | 186.1 | - | - | 27 | - | |

| Compressive | 0 | 155.6 | - | - | 25.7 | - | |

| Tensile | - | - | - | 10 | - | - | |

| Tensile | - | - | - | 14.6 | - | - | |

| Compressive | 0 | 187.8 | - | - | 25.1 | - | |

| Tensile | - | - | - | 13 | - | - |

| Laboratory | Field | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak | Residual | Instantaneous | Equivalent | |

| c (MPa) | 12 | 3 | 3.4 | 2.5 |

| ϕ (°) | 59 | 51 | 44 | 47 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Elkharrat, K.; Lafuerza, S.; Homberg, C.; Gasc-Barbier, M. Rock Mass Strength Characterisation from Field and Laboratory: A Comparative Study on Carbonate Rocks from the Larzac Plateau. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12956. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412956

Elkharrat K, Lafuerza S, Homberg C, Gasc-Barbier M. Rock Mass Strength Characterisation from Field and Laboratory: A Comparative Study on Carbonate Rocks from the Larzac Plateau. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(24):12956. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412956

Chicago/Turabian StyleElkharrat, Kévin, Sara Lafuerza, Catherine Homberg, and Muriel Gasc-Barbier. 2025. "Rock Mass Strength Characterisation from Field and Laboratory: A Comparative Study on Carbonate Rocks from the Larzac Plateau" Applied Sciences 15, no. 24: 12956. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412956

APA StyleElkharrat, K., Lafuerza, S., Homberg, C., & Gasc-Barbier, M. (2025). Rock Mass Strength Characterisation from Field and Laboratory: A Comparative Study on Carbonate Rocks from the Larzac Plateau. Applied Sciences, 15(24), 12956. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152412956