Featured Application

The results of this study will be used to verify the methodology for determining the perpetrator’s mass in forensic science based on a footwear impression left in sands.

Abstract

In laboratory testing, analyzing the influence of various factors on oedometer test results is essential, since the oedometric modulus (Eoed) directly affects e. g. footwear impressions in forensic engineering. This study focused on incremental loading oedometer tests on two types of sand—silty sand (SM) and sand with fine-grained admixture (S-F). For each loading stage, four identically prepared samples were tested at density indices ID = 0.15, 0.65, and 0.85. The Eoed was calculated using both Slovak Technical Standard (STN) and ISO Standard, which differ in evaluating strain increments at each loading stage. The difference in Eoed between ID = 0.15 and 0.85 corresponded to about 1.5 to 5.6 times the Eoed value at ID = 0.15 for SM and about 1.0 to 3.3 times for S-F. Between ID = 0.65 and 0.85, the difference amounted to about 0.18 to 0.63 times the Eoed value at ID = 0.65 for SM and about 0.51 to 1.44 times for S-F. The difference in Eoed between STN and ISO ranged from 0.00003 to 0.067 times the STN-based Eoed value for SM and from 0 to 0.017 times for S-F. Results show a very high linear dependence of Eoed on ID for SM (Pearson R = 0.97–0.99) and high-to-very-high for S-F (Pearson R = 0.83–0.91). Accurate determination of Eoed enables a more reliable and precise assessment of footwear impressions.

1. Introduction

The determination of soil deformation characteristics is among the fundamental tasks of geotechnical engineering, as it enables the quantification of soil behavior under stress and allows for the prediction of structural settlements, stress redistribution, and the overall stability of geotechnical structures. A key parameter is the oedometric modulus Eoed, which represents the relationship between the change in vertical stress and the corresponding vertical strain during one-dimensional compression (consolidation), i.e., without lateral deformation. Accurate determination of this parameter is essential for the design and assessment of foundations, embankments, and earth structures.

The authors in [1] state that buried pipe design requires knowledge of the backfill material to properly design the backfill structure. The strength of the backfill material is described in terms of the soil reaction modulus E′ and the constrained modulus Eoed. As E′ is an empirical parameter, Eoed can be measured in the laboratory through oedometer tests. Therefore, the reliable determination of Eoed is necessary.

The authors in [2] state that there is little research on the standard consolidation test of coarse-grained soil in China, and most scholars focus on isobaric consolidation. However, the standard consolidation test is one of the necessary tests to study the HS model. Therefore they present a large-scaled consolidator with a 300 mm diameter, which is used to measure the relationship between the deformation and pressure of a sandy gravel soil sample by a standard consolidation test. The stress–strain curve under lateral limit conditions is obtained, and the oedometric modulus Eoed can be calculated. Therefore, reliable Eoed values obtained from laboratory tests are important for such modeling.

Because the process of obtaining the compression coefficient (CC) via oedometer test is recognizably time-consuming and experienced, skilled technicians are required to ensure that the test results are reliable; the authors in [3] propose a low-cost, fast, and reliable alternative for estimating this soil parameter utilizing a hybrid metaheuristic optimized neural network. The proposed model was verified at a large-scale real-life urban project where a dataset of the project with 441 samples, which recorded results of the CC and their twelve physical parameters, were used. In this case, the reliability of CC values obtained from oedometer tests is decisive for the applicability of the model.

Time-consuming work and the requirement for experienced, skilled technicians cause the fact that, in laboratory practice, a single sample is rarely tested multiple times but often only once, and the obtained Eoed value is considered the characteristic value used for calculating soil deformation and subsequently for the assessment of the serviceability limit state of geotechnical structures. Even in accordance with [4], ground investigation requirements for category 1 projects are usually minimal, as verifications rely solely on local experience. Therefore, in design practice, engineers use a quadratic relationship between Eoed and ID, in accordance with [5], or interpolate Eoed values within the given range of the ID [6]. Settlement, e.g., of a foundation footing, is then calculated as the sum of the compressions of the soil layers beneath the footing, which is directly proportional to the thickness of the soil layer, with the additional stress from structures at the middle of the layer and inversely proportional to Eoed. While this practice is applied in geotechnical engineering, it is unacceptable in forensic engineering.

To our knowledge, there is no study that examines the influence of sand sample homogeneity and sample preparation methods on Eoed values. If sands are used as model sands for investigating the depth of the perpetrator’s footwear impression left in sands, a reliable Eoed value is decisive. This is under the assumption that the perpetrator’s footwear impression left in sands is calculated similarly to the settlement of a foundation footing, for example, a 40% difference in the obtained Eoed values leads to approximately a 40% difference in the estimated mass of the perpetrator, which is unusable. For this reason, there is a need to determine the most accurate Eoed values of model sands possible, considering the effects of sample non-homogeneity, sample preparation methods, and also sand density on the Eoed values of sands.

The transfer of soil particles and the quantification of soil material adhering to footwear have been investigated in forensic studies [7,8]. However, considerably less attention has been paid to the depth of footwear impressions in soils. Authors in [9] present a study focusing on the mechanical response of soils responsible for the formation of plastic (three-dimensional) footwear impressions. Five shoes and their corresponding three-dimensional impressions made in both sand and soil were compared using a grid system and tread descriptors commonly employed in the United Kingdom. However, no analyses of sand or soil deformation parameters were conducted.

The authors in [10] analyzed effects of soil moisture on shoe impression detail and longevity. The shoe impressions are created in a standard topsoil with varying amounts of water and monitored over 48 h. They state that soil moisture has a very large effect on shoeprint detail and longevity. Soil moisture has an inverse relationship with detail longevity, meaning that the more moisture contained within soil, the faster the print will degrade and become useless for identification of class characteristics. However, no information on soil deformation properties and the relation between them and shoe impression is provided.

Even in the Interpol Review Paper of Marks and Impression Evidence 2019–2022 [11], which presents 49 references, there is no study addressing the relationship between the depth of a footwear impression and soil deformation parameters.

The depth of an impression represents a direct mechanical response of the soil to the applied load and, therefore, can provide valuable information about the interaction between the suspect and the ground surface at the time of contact. Despite its potential forensic significance—particularly for estimating loading conditions or even the body weight of an individual—to our knowledge, no research has yet addressed the quantitative relationship between applied stress and impression depth. This gap highlights the need for controlled laboratory experiments aimed at linking measurable soil deformation parameters with the depth of footwear impressions.

While the estimation of loading forces can be relatively reliable, the determination of consistent soil deformation parameters (e.g., the oedometer modulus of sand obtained from incremental loading oedometer tests) is more challenging due to sample inhomogeneities and the random behavior of particles during compaction into the oedometer ring and subsequent loading.

Moreover, different approaches to evaluating vertical strain (i.e., whether the initial sample height or the current height after each loading increment is considered) can also affect the calculated values of the oedometer modulus Eoed. For example, the oedometer modulus can be calculated in accordance with ISO Standard [12] (ISO) as follows:

Using the symbols introduced in this document, the following equation is obtained:

where σ′v1 (kPa)—pressure applied to the specimen in the previous load increment, σ′v2 (kPa)—pressure applied to the specimen in the load increment that is considered, Hi (mm)—initial height, i.e., height of the specimen at the start of the increment, and Hf (mm)—height of the specimen at the end of the increment.

According to the Polish Standard [13] (PN), the primary compression modulus M0 or secondary modulus M (kPa or MPa) is calculated by the following formula:

where Δσi (kPa, MPa)—pressure increase, Δσi = σi − σi−1; hi−1 (mm)—specimen height in the oedometer before the pressure increases from σi−1 to σi; Δhi (mm)—decrease in sample height in the oedometer ring after pressure increases by Δσi; and Δhi = hi−1 − hi.

After arranging Equation (2) according to the PN sign convention, the oedometer modulus according to ISO is calculated using the following formula:

As we can see, there is no difference between Equations (3) and (4); therefore, the methods for calculating the oedometer modulus according to ISO and PN are the same.

According to the Slovak Standard [14] (STN), the oedometer modulus for the stress interval σi−1, σi is calculated from deformations si−1,c, and sic at the end of the corresponding loading (unloading) stages by the formula:

For reconsolidated testing samples, the original sample height hor is replaced by the sample height after reconsolidation hr.

After arranging Equation (2) according to the STN convention, the oedometer modulus according to ISO is calculated by the following formula:

The method for calculating Eoed is not presented in ASTM Standard D2435/D2435M-11 [15].

Comparing Equations (5) and (6), we can see that there is a difference in parts (hor – si−1,c) and hor. This means that oedometer modulus calculated according to STN will be larger than the oedometer modulus calculated according to ISO and PN (hereinafter referred to simply as ISO).

Footwear impressions in soil can be simulated by applying loads through footwear of various sizes onto model sand placed in a container of sufficient dimensions to prevent boundary effects from the container walls. The largest footwear model requires up to 300 kg of sand, whereas the sand mass compacted in an oedometer sample ring is less than 1 kg. Hence, there is a need to determine the most representative oedometer modulus of the model sand.

In this study, we present incremental loading oedometer tests on two model sands. Four samples were identically prepared by the same person in four oedometers and tested under the same procedure at density indices ID = 0.15, 0.65, and 0.85. Two methods were used to calculate Eoed according to the STN and ISO standards, which differ in the evaluation of vertical strain increments at each loading step. Standard and robust statistical analyses were performed to identify and exclude outliers. Based on the determined Eoed values for different relative density indices ID, linear relationships between Eoed and ID were proposed. The obtained Eoed values will be used for the analysis of footwear impressions in the subsequent experimental research.

2. Materials and Methods

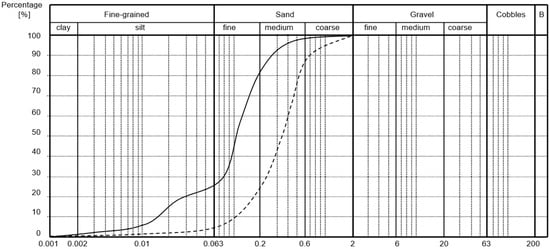

The sand from the Polanka quarry, Czech Republic, and the sand from the Danube River in Bratislava, Slovakia, with a maximum particle diameter of 2 mm, were used in the research. The standard STN EN ISO 17892-1: 2023 [16] was applied to determine the water content, STN EN ISO 17892-4: 2023 [17], to determine the particle size distribution, and STN EN ISO 17892-12: 2019 [18] to determine the liquid limit wL and plastic limit wP. The grain-size distribution curves of the sands are shown in Figure 1. The soil classification, in accordance with [5], and their properties are presented in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Grain-size distribution curves of sands: solid line: sand from the Danube River in Bratislava; dashed line: sand from the Polanka quarry.

Table 1.

Soil classification and properties.

Four oedometers (IGHP n. p., Žilina, Slovakia) were used for soil testing. The parameters of the oedometers are listed in Table A1. The apparatus has a lever loading system that increases the weight of the load tenfold. For each oedometer, an exactly calculated mass of weights was applied based on its area. Deformations of both the oedometer itself (metal samples) and the soil specimens were measured using an analog dial gauge with a 30 mm measurement range and 0.01 mm resolution.

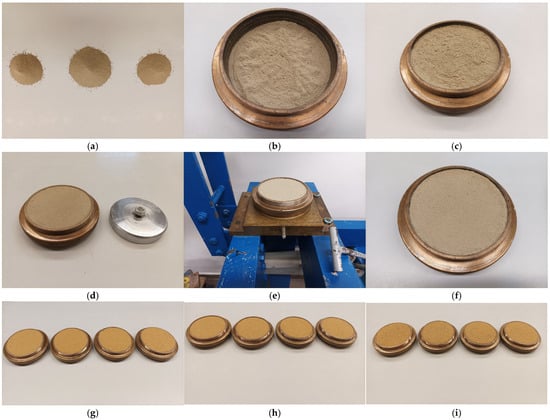

The masses of the sands compacted into the oedometer specimen rings to achieve density indices of 0.15, 0.65, and 0.85 were calculated from their maximum and minimum dry unit weights and the volumes of the oedometers. Based on the masses of the sands, the sand moisture content, and their particle density, the void ratios were calculated and are presented in Table A1. Sample preparation procedure is presented in Appendix A.2 of Appendix A and in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Specimen preparation: (a) three parts with a total mass of 444.604 g of Danube sand (oedometer A, ID = 0.15); (b) the first quarter of the specimen after compaction and lightly loosened surface; (c) further half of the specimen after compaction and lightly loosened surface; (d) the last quarter compacted up to the surface of the oedometer; (e) specimen in oedometer A after unloading; (f) detail of the specimen in oedometer A after loading; (g) four specimens of Polanka sand in oedometers A, B, C, and D (ID = 0.15) before testing; (h) four specimens of Polanka sand in oedometers A, B, C, and D (ID = 0.15) after testing; and (i) four specimens of Polanka sand in oedometers A, B, C, and D (ID = 0.65) after testing.

To eliminate the influence of the deformation of the oedometers themselves on the test results, four metal samples were used. These samples had the same height as the oedometer rings and a diameter 2 mm smaller. Figure 3a shows the four metal samples placed in the oedometers. The oedometers with metal samples were subjected to the same step-loading sequence as that applied to the soil specimens (see Table A1 for apparatus deformation). In the center of the apparatus, the plungers can be seen. Figure 3b shows the oedometers during testing (Danube sand, ID = 0.15; normal stress 200 kPa).

Figure 3.

Oedometer apparatus: (a) Four metal samples in oedometers (oedometer A is at the back left, oedometer B at the back right, oedometer C at the front left, and oedometer D at the front right); the plungers can be seen in the center of the apparatus; (b) The oedometers during testing (Danube sand, ID = 0.15; normal stress 200 kPa).

The oedometer tests were performed using a stepwise loading procedure with the following sequence of loading stages: stress from the plunger weight; 25 kPa; 50 kPa; 100 kPa; 200 kPa; and 400 kPa. In accordance with STN [14], each loading stage lasted 24 h.

The Eoed values were calculated according to ISO (Equation (2)) and STN (Equation (6)). Soil deformation was determined as the difference between the dial gauge reading and the deformation of the oedometer itself for each loading step. The Eoed values were calculated for the following normal effective stress intervals: plunger—25 kPa (hereafter referred to as loading interval No. 1 (LI 1)), 25 kPa–50 kPa (loading interval No. 2 (LI 2)), 50 kPa–100 kPa (loading interval No. 3 (LI 3)), 100 kPa–200 kPa (loading interval No. 4 (LI 4)), and 200 kPa–400 kPa (loading interval No. 5 (LI 5)).

For each sand, four Eoed values obtained from four odometers (A, B, C, and D) for the same loading interval were subjected to standard and robust statistical analyses. In the standard statistical analyses, the mean (), range (Range), standard deviation (SD), and coefficient of variation (CV) were calculated according to well-known formulas in statistics.

In the robust statistical analyses, the following parameters were calculated. First, the values were sorted as

Median (Mdn): the mean of the two middle values:

First quartile (Q1):

Third quartile (Q3):

Interquartile range (IQR):

Lower fence (LF):

Upper fence (UF):

Median Absolute Deviation (MAD):

Individual Modified Z-scores (MiA, MiB, MiC, MiD): for the Eoed values from odometers A, B, C, and D, respectively, according to [19]:

Values of indicate outlying Eoed values [19].

3. Results

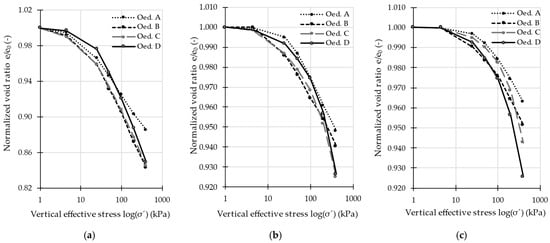

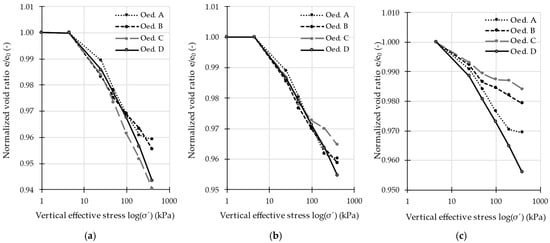

The measured deformations of specimens (including deformations of the oedometers) are presented in Table A2. The void ratios and the normalized void ratios at the end of the loading stage are presented in Table A3 and Table A4, respectively. The relationships between normalized void ratio e/e0 and vertical effective stress σ′ are shown in Figure 4 (Danube sand) and Figure 5 (Polanka sand).

Figure 4.

The relationships between normalized void ratio e/e0 and vertical effective stress σ′ (Danube sand): (a) ID = 0.15; (b) ID = 0.65; (c) ID = 0.85.

Figure 5.

The relationships between normalized void ratio e/e0 and vertical effective stress σ′ (Polanka sand): (a) ID = 0.15; (b) ID = 0.65; (c) ID = 0.85.

As can be seen in Table A3, Danube sand has a large initial void ratio, so the Eoed values are expected to be low. Polanka sand has a smaller initial void ratio, resulting in higher expected Eoed values. This fact can also be seen in Figure 4 and Figure 5, where the normalized void ratios of Polanka sand are larger than those of Danube sand. The random variation in the curves from different oedometers indicates that there are no systematic errors. The closer agreement of the curves at ID = 0.65 for both sands suggests that the scatter of Eoed values among different oedometers is smaller at this density. This behavior is likely caused by non-uniform compaction within the samples: samples at ID = 0.15 are very easy to compact, whereas samples at ID = 0.85 are much more difficult to compact.

The calculated Eoed of Danube sand according to the STN (excluding deformations of the oedometers) are presented in Table 2 and Table A5. The calculated Eoed of Danube sand according to the ISO (excluding deformations of the oedometers) are presented in Table 3 and Table A6. Similarly, the calculated Eoed of Polanka sand according to the STN and ISO (excluding deformations of the oedometers) are presented in Table 4 and Table A7 and Table 5 and Table A8, respectively.

Table 2.

Oedometric moduli Eoed for various density index ID according to the STN, Danube sand.

Table 3.

Oedometric moduli Eoed for various density index ID according to the ISO, Danube sand.

Table 4.

Oedometric moduli Eoed for various density index ID according to the STN, Polanka sand.

Table 5.

Oedometric moduli Eoed for various density index ID according to the ISO, Polanka sand.

As shown in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5, both SD and CV vary with ID and the load intervals. For the Danube sand, the lowest CV value (9.07%) was recorded at ID = 0.65, load interval No. 2 (STN, see Table 2, bold, underlined, italic number), whereas the highest CV value (49.61%) was recorded at ID = 0.65, load interval No. 1 (ISO, see Table 3, bold, underlined number). For the Polanka sand, the lowest CV value (8.66%) occurred at ID = 0.65, load interval No. 2 (ISO, see Table 5, bold, underlined, italic number), while the highest CV value (154.87%) occurred at ID = 0.85, load interval No. 4 (ISO, see Table 5, bold, underlined number). Analysis of all CV values in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 indicates that their variation is random, and there is no extreme case in which the minimum CV for a certain ID and load interval exceeds the maximum CV for another ID and load interval. Therefore, it can be concluded that no systematic error is present, and the variation in CV values exhibits no systematic dependence on ID or load interval.

Due to the high CV value, a robust statistical analysis was performed to identify and exclude outliers. It was found that all measured Eoed values did not exceed the LF and UF; even the value Eoed = 1008.817 MPa, which occurred at ID = 0.85, load interval No. 4 (ISO, see Table 5, bold, underlined, italic number), did not exceed the upper fence UF = 1345.299 MPa (ISO, see Table A8, bold, underlined number).

In addition, another robust statistical analysis using the Individual Modified Z-score method was applied to further identify and exclude outliers. Individual Modified Z-scores (MiA, MiB, MiC, MiD) for the Eoed values obtained from oedometers A, B, C, and D, respectively, were calculated according to Equation (15) and are presented in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5. Individual Modified Z-scores greater than 3.5 (number with an asterisk) indicate outliers.

These Individual Modified Z-scores represent, in most cases, the maximum of the four Eoed values for a given load interval; however, in two cases, they also represent the minimum Eoed values for a given load interval (Table 2: 12.526 MPa (with an asterisk); Table 3: 12.449 MPa (with an asterisk), both at ID = 0.85, loading interval No. 3; Table 4: 8.082 MPa (with an asterisk); Table 5: 8.045 MPa (with an asterisk), both at ID = 0.65, loading interval No. 2).

Overall, the analysis of all LF/UF and Individual Modified Z-score values in Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 indicates that their variation is random and shows no systematic dependence on ID or load interval. No systematic error was detected.

Unlike the arithmetic mean, which is highly sensitive to outliers, the median provides a robust estimate of central tendency. Given the presence of outliers in the tested datasets (identified using the Modified Z-score) and the small sample size, the median was chosen as the most consistent estimate of the characteristic value of the Eoed. For four values obtained from four odometers, the median equals the mean of the two middle values after removing the maximum and minimum. To ensure methodological consistency when comparing results across different density indices, the same robust measure of central tendency (median) was applied to all datasets. This prevents comparisons of statistics with inherently different properties. The characteristic Eoed values are reported in the last row of Table 2, Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5.

Differences in oedometric moduli Eoed of Danube sand (according to STN and ISO) caused by different density index ID are presented in Table 6. Similarly, differences in oedometric moduli Eoed of Polanka sand (according to STN and ISO) caused by different density index ID are presented in Table 7.

Table 6.

Differences in oedometric moduli Eoed caused by different density index ID (STN, ISO, Danube sand).

Table 7.

Differences in oedometric moduli Eoed caused by different density index ID (STN, ISO, Polanka sand).

As shown in Table 6 and Table 7, the difference in Eoed between ID = 0.15 and ID = 0.85 ranged from 138.8 to 562.3% (Danube sand, SM, STN) and 152.6 to 565.0% (Danube sand, SM, ISO); 97.0 to 323.1% (Polanka sand, S-F, STN) and 97.7 to 328.3% (Polanka sand, S-F, ISO), which are very high. The difference in Eoed between ID = 0.65 and ID = 0.85 ranged from 16.6 to 63.1% (Danube sand, SM, STN) and 17.5 to 63.4% (Danube sand, SM, ISO); 50.6 to 143.4% (Polanka sand, S-F, STN) and 50.9 to 144.4% (Polanka sand, S-F, ISO), which are much smaller. For Danube sand, the lowest difference occurs for loading interval 5 (normal stress 200 kPa–400 kPa), whereas for Polanka sand, the lowest difference occurs for loading interval 2 (normal stress 25 kPa–50 kPa), which indicates different behavior of the sands under the same loading conditions.

Differences in oedometric moduli Eoed between STN and ISO for Danube sand and Polanka sand are presented in Table 8. As can be seen, the Eoed values according to STN are higher than those according to ISO, which is consistent with Equations (2) and (6). However, the differences are small, with the maximum difference of 6.7% occurring for ID = 0.15, loading interval No. 5 (Danube sand). For Polanka sand, the maximum difference is 1.7%, also occurring for ID = 0.15, loading interval No. 5. In general, it can be observed that the differences are larger under higher loads (larger loading interval number). An exception is Polanka sand at ID = 0.85, where the percentage difference (0.50%) for loading interval No. 5 is smaller than for loading interval No. 4 (0.57%) due to the high value of Eoed for loading interval No. 5.

Table 8.

Differences in oedometric moduli Eoed between STN and ISO (Danube sand, Polanka sand).

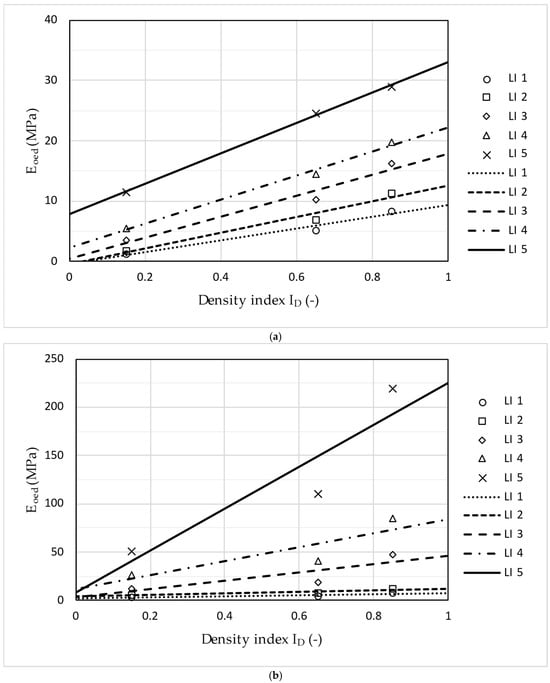

Based on the obtained Eoed values for different ID, a linear relationship between Eoed and ID was proposed in the form Eoed = a·ID + b. The values of a and b, as well as the Pearson’s correlation coefficient R and the coefficient of determination R2, are given in Table 9. Based on the R values for Polanka sand and the interpretation of correlation strength [20], it can be stated that the linear dependence of Eoed on ID, with R ranging from 0.834 to 0.917, is high (R = 0.70–0.90) to very high (R = 0.90–1.00).

Table 9.

Linear relationship between the oedometer modulus Eoed and the relative density index ID.

For Danube sand (loading intervals No. 3–5), the Pearson’s correlation coefficient R ranges from 0.995 to 0.999, defining the linear dependence of Eoed on ID as very high. Regarding loading interval No. 1, the initial unconstrained linear regression between the oedometer modulus Eoed and the relative density index ID yielded the model Eoed = 9.784·ID − 0.406 (MPa), with a very high linear dependence (R = 0.984). The negative intercept (−0.406) suggests a nonphysical negative modulus as ID approaches zero. In such a case, according to some geotechnical laboratory practices, constrained regressions are applied for parameters that are assumed to be zero (e.g., forcing zero cohesion in direct shear tests accordance with [21]). By analogy, the regression in this study was recalculated by constraining the line to pass through the origin (0, 0), resulting in Eoed = 9.209·ID (MPa). This constrained model demonstrates an even higher linear dependence (R = 0.995) compared to the initial unconstrained fit (R = 0.984). Although Eoed does not necessarily equal zero when ID = 0, this approach provides a physically acceptable and simplified correlation that is valid for ID ≥ 0.15, corresponding to the tested range of relative densities (see Table 9, Danube sand, loading intervals No. 1). Similarly, for loading interval No. 2, the regression was recalculated by constraining the line to pass through the origin (0, 0), resulting in Eoed = 12.328·ID (MPa) with a Pearson’s correlation coefficient R = 0.995, indicating a very high linear dependence of Eoed on ID. The unconstrained linear relationship between the oedometer modulus Eoed and the relative density index ID for the Danube sand and the Polanka sand is presented in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The unconstrained linear relationship between the oedometer modulus Eoed and the relative density index ID (symbols LI 1–LI 5 denote loading intervals No. 1 to No. 5): (a) Danube sand; (b) Polanka sand.

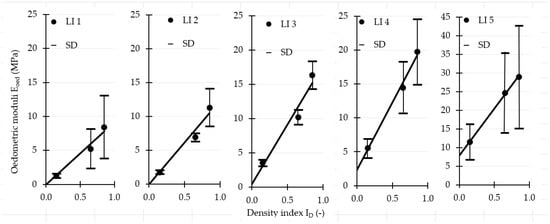

To enhance the informational value of the visual presentation, error bars have been added to the Eoed values (determined according to ISO), indicating the standard deviation (see Figure 7 and Figure 8).

Figure 7.

Constrained (through-origin, applied for loading intervals LI 1 and LI 2) and unconstrained linear relationships between Eoed and ID (Danube sand, ISO); error bars denote SD.

Figure 8.

Unconstrained linear relationships between Eoed and ID (Polanka sand, ISO); error bars denote SD (for ID = 0.85, the SD value for loading interval LI 4 is 471.1 MPa and for LI 5 is 258.0 MPa, which are displayed on the graph reduced by a factor of 10).

As can be seen in Figure 7 and Figure 8, SD values are smaller at lower ID (lower Eoed) and also at lower vertical effective stresses (loading intervals LI 1–3). Larger SD values occur at higher ID (higher Eoed) and higher vertical effective stresses (loading intervals LI 4–5). Extreme values are also observed (see Figure 8, ID = 0.85, loading intervals LI 4 and LI 5). Such outliers were successfully detected using the Modified Z-score method and were excluded from the Eoed evaluation.

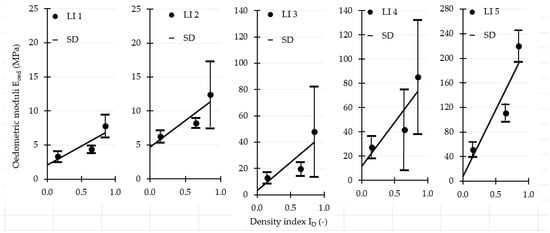

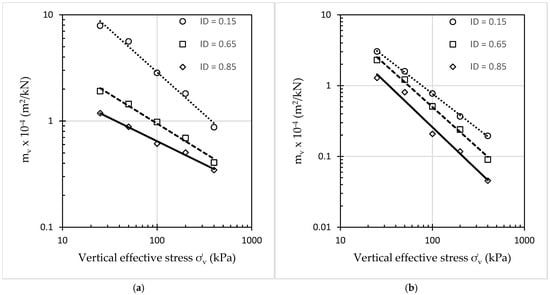

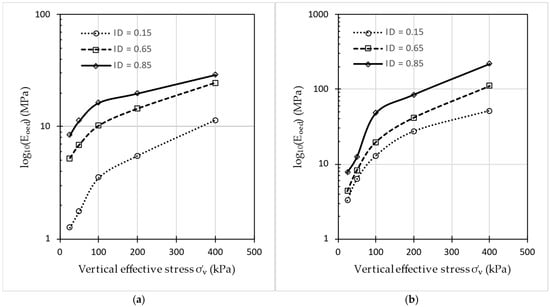

To examine the behavior of sands under loading, the relationship between mv and vertical effective stress σ′v is presented in Figure 9. The relationship between log (Eoed) and vertical effective stress σ′v is presented in Figure 10. The power function is defined as:

where C0 and n correspond to the fitting parameters of the power function. Values of C0 and n are presented in Table 10. Figure 9 indicates that the soil compressibility decreases, demonstrating strain-hardening behavior resulting from incremental loading.

Figure 9.

Relationships between mv and vertical effective stress σ′v (Eoed acc. to ISO): (a) Danube sand; (b) Polanka sand.

Figure 10.

Relationships between log (Eoed) and vertical effective stress σ′v (Eoed acc. to ISO): (a) Danube sand; (b) Polanka sand.

Table 10.

Parameters of the power function for various ID.

The graphical analysis (Figure 10) confirms a change in material behavior. For all tested densities, we observe that at low stresses (approximately up to 100 kPa), the increase in the compressibility modulus Eoed is rapid, followed by a gradual decrease in the rate of modulus increase at higher stresses. This point of slope change is interpreted as the probable boundary of particle-bond yielding, with its precise location being slightly influenced by the relative density ID.

4. Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, there are no indicative (reference) CV values for oedometer moduli obtained from laboratory testing. Authors in [22] state that because of the natural heterogeneity of soils, the estimates of c and tanφ obtained through different samples drawn from the same deposit present a certain degree of variability, and this has stimulated the formulation of statistical analysis of the shear strength parameters. Based on results presented in the literature review, it emerges that the coefficient of variation of tanφ is generally considered to be in the range 10% to 20%, while that of c seems to be between 20% and 60%.

The maximum CV value for Danube sand, considering all ID values and loading intervals, is 49.59% (Eoed obtained in accordance with STN) and 49.61% (Eoed obtained in accordance with ISO), see Table 2 and Table 3 (bold, underlined number), which are therefore lower than the CV of cohesion c (60%). For Polanka sand, 60% of the CV values (Eoed from 9 loading intervals out of 15, obtained in accordance with STN and ISO, see Table 4 and Table 5) are lower than 60%. We assume that the high CV values are caused not only by soil heterogeneity but also by human factors (even though the tests were prepared and conducted by the same person following the same procedure, differences in compaction forces cannot be entirely ruled out). Although it is difficult to compare the CV of Eoed with the CV of soil cohesion c, the mentioned values may serve as reference values for further research.

Authors in [23] present the results of oedometer tests on Osorio sand, which is classified as non-plastic, uniform fine sand. The specific gravity of the solids is 2.63 (Polanka sand: 2.64). Mineralogical analysis showed that sand particles are predominantly quartz (Polanka sand particles contain 91.6% SiO2 [24]). The grain size is purely fine sand (Polanka sand is classified as sand with fine-grained admixture S-F, with sub-angular to rounded particles) with a mean diameter of 0.16 mm (Polanka sand: 0.36 mm), with uniformity and curvature coefficients of 1.9 and 1.2, respectively (Polanka sand: 3.11 and 1.23). The minimum and maximum void ratios are 0.6 and 0.9, respectively (Polanka sand: 0.42 and 0.74). The authors suggest that the relationship between the oedometer modulus Eoed and the relative density index ID for Osorio sand is Eoed = 41.18·ID + 29.40 MPa. Among the ten interval-specific experimental regressions obtained in this study (see Table 9), the regression for Polanka sand, loading interval No. 4, Eoed = 72.255·ID + 11.626 MPa, provides the closest approximation to the literature correlation. Notably, this regression intersects the literature correlation at approximately ID ≈ 0.572 (Eoed ≈ 52.9 MPa), providing a point of reference, even though the tested Polanka sand differs from those in the literature.

A limitation of this study is that particle shape, mineral composition, particle-crushing potential, and other characteristics of the sands that influence compression behavior were not sufficiently analyzed (are available only for Polanka sand, see the previous paragraph). Therefore, it will be necessary in further research to perform tests to determine these parameters and relate them to the obtained Eoed values.

For the incremental loading tests, separate linear regressions were derived for each loading interval. This approach allows a more detailed representation of the behavior of the tested sands under varying stress conditions, capturing changes in stiffness with each incremental load. The resulting interval-specific regression models reliably describe the behavior of the sands over the investigated range of relative densities. The regressions are considered valid for ID between 0.15 and 0.85, corresponding to the experimental range. Due to the very high linear dependence, it is reasonable to interpolate within this range with confidence, while extrapolation outside this interval is not supported by the data.

Regarding the difference in Eoed caused by different approaches to evaluating vertical strain increments at each loading step (STN vs. ISO), authors in [25] present results of incremental loading oedometer tests on firm CI (clay of intermediate plasticity). For the loading interval 100–200 kPa, the difference in Eoed resulting from the two approaches is 0.266 MPa (6.803 MPa vs. 6.537 MPa), corresponding to 3.91%. This value of 3.91% is the closest to that (4.60%) observed for Danube sand at ID = 0.15 for the same loading interval (see Table 8, loading interval No. 4).

The oedometer tests in this study were limited to one-way loading, focusing only on compression. Unloading and reloading cycles were not considered, so the elastic rebound could not be assessed. To address this limitation, further tests including unloading–reloading cycles will be conducted in future research to capture the full compressive and elastic behavior of sands.

Outliers were successfully detected using the Modified Z-score method and were excluded from the Eoed evaluation. However, the small sample size (n = 4 per condition) limits the generalizability of the results. Although the median was chosen as the most consistent estimate of the characteristic Eoed value, the reliability of the mean of the two middle values after removing the maximum and minimum may not be very high. Therefore, it is useful in future research to increase the number of tests. Although performing repeated oedometer tests is more time-consuming, it is methodologically valuable; for instance, five repetitions on the same oedometer are planned for future work. After obtaining more data, it is necessary to consider whether a relationship between Eoed and ID other than linear exists. However, since there are few data points in this study, only a linear relationship can be considered. Due to the very high linear dependence of Eoed on ID for SM (Pearson R = 0.97–0.99) and the high-to-very-high dependence for S-F (Pearson R = 0.83–0.91), the applicability of this relationship in this case is justified.

5. Conclusions

The results of the oedometer tests show that the Eoed values for the same loading interval, obtained from four different oedometers, are not identical, even though the samples were prepared and tested in the same manner by the same operator and considering the deformation of the oedometers themselves. It is assumed that the differences were caused not only by the inhomogeneity of the samples but also by the preparation process, which cannot be perfectly identical for each tested sample.

The IQR method for outlier exclusion does not remove outliers when only four values are available, even though laboratory experience clearly indicates that some values are outliers. Such outliers were successfully detected using the Modified Z-score method.

The relative density significantly affects the Eoed of the examined sands. The difference in Eoed between ID = 0.15 and ID = 0.85 reached up to 565.0% for Danube sand (SM) and 328.3% for Polanka sand (S-F).

The results show a very high linear dependence of Eoed on ID for SM (Pearson R = 0.97–0.99) and a high-to-very-high dependence for S-F (Pearson R = 0.83–0.91).

The difference in Eoed between STN and ISO ranged From 0.003 to 6.7% for SM and 0.0 to 1.7% for S-F. A difference of 6.7% should not be considered negligible, as it may affect the values of footwear impressions, thereby influencing the reliability of estimating a perpetrator’s weight in forensic engineering.

The obtained Eoed values will be applied in subsequent experimental analyses of footwear impressions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization. G.N., R.B., V.A. and J.M.; methodology. G.N., R.B., V.A. and J.M.; formal analysis. G.N., R.B., V.A. and J.M.; investigation. G.N., R.B., V.A. and J.M.; writing—original draft preparation. G.N. and R.B.; writing—review and editing. G.N., R.B., V.A. and J.M.; project administration. R.B.; funding acquisition. R.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education of the Slovak Republic, grants VEGA No. 1/0444/25 and VEGA No. 1/0775/24.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| Eoed | Oedometric modulus |

| SM | Silty sand |

| S-F | Sand with fine-grained admixture |

| ID | Density index |

| STN | Slovak Technical Standard |

| ISO | ISO Standard |

| PN | Polish Standard |

| CC | Compression coefficient |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| CV | Coefficient of variation |

| Q1 | First quartile |

| Q3 | Third quartile |

| IRQ | Interquartile range |

| LF | Lower fence |

| UF | Upper fence |

| MAD | Median Absolute Deviation |

| MiA | Individual Modified Z-score for Eoed from oedometer A |

| MiB | Individual Modified Z-score for Eoed from oedometer B |

| MiC | Individual Modified Z-score for Eoed from oedometer C |

| MiD | Individual Modified Z-scores for Eoed from oedometer D |

| CI | Clay of intermediate plasticity |

Appendix A. Data and Methods

Appendix A.1. Supplementary Data

Table A1.

Parameters of oedometers and void ratio for various density indices ID.

Table A1.

Parameters of oedometers and void ratio for various density indices ID.

| Oedometers | Danube Sand | Polanka Sand | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | A | B | C | D | |

| Height (mm) | 30.328 | 30.188 | 30.388 | 30.563 | 30.328 | 30.188 | 30.388 | 30.563 |

| Diameter (mm) | 119.824 | 120.125 | 120.150 | 119.599 | 119.824 | 120.125 | 120.150 | 119.599 |

| Plunger mass (kPa) | 5115 | 5090 | 5209 | 5136 | 5115 | 5090 | 5209 | 5136 |

| Pressure from plunger (kPa) | 4.450 | 4.406 | 4.507 | 4.485 | 4.450 | 4.406 | 4.507 | 4.485 |

| Apparatus def. at plunger (mm) | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Apparatus def. at 25 kPa (mm) | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.041 | 0.001 | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.041 |

| Apparatus def. at 50 kPa (mm) | 0.012 | 0.032 | 0.038 | 0.076 | 0.012 | 0.032 | 0.038 | 0.076 |

| Apparatus def. at 100 kPa (mm) | 0.051 | 0.064 | 0.108 | 0.123 | 0.051 | 0.064 | 0.108 | 0.123 |

| Apparatus def. at 200 kPa (mm) | 0.111 | 0.107 | 0.199 | 0.164 | 0.111 | 0.107 | 0.199 | 0.164 |

| Apparatus def. at 400 kPa (mm) | 0.261 | 0.179 | 0.277 | 0.207 | 0.261 | 0.179 | 0.277 | 0.207 |

| Minimum void ratio (-) | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| Void ratio for ID = 0.15 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| Void ratio for ID = 0.65 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.54 | 0.54 |

| Void ratio for ID = 0.85 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.47 | 0.47 |

| Maximum void ratio (-) | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.42 |

Note: The dimensions of the oedometer specimen ring were measured using a vernier caliper with a resolution of 0.01 mm. Each diameter was determined as the mean of two measurements taken in perpendicular directions, and the height as the mean of four measurements. Values are reported to three decimal places (rounded to 0.001 mm) to minimize rounding errors in further calculations (e.g., volume determination). The apparatus deformation values represent the best estimates obtained by visual interpolation between dial divisions (0.01 mm resolution) to minimize rounding errors in the Eoed calculation.

Table A2.

Measured deformations of specimens for various density index ID (including deformations of the oedometers).

Table A2.

Measured deformations of specimens for various density index ID (including deformations of the oedometers).

| Measured Deformations (mm) | Danube Sand | Polanka Sand | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | A | B | C | D | |

| Density index ID = 0.15 | ||||||||

| After plunger load | 0.089 | 0.143 | 0.163 | 0.054 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| After load 25 kPa | 0.557 | 0.678 | 0.684 | 0.430 | 0.134 | 0.217 | 0.212 | 0.221 |

| After load 50 kPa | 0.891 | 1.146 | 1.118 | 0.902 | 0.285 | 0.343 | 0.372 | 0.368 |

| After load 100 kPa | 1.272 | 1.591 | 1.604 | 1.418 | 0.440 | 0.449 | 0.590 | 0.532 |

| After load 200 kPa | 1.684 | 2.182 | 2.198 | 2.012 | 0.600 | 0.562 | 0.802 | 0.713 |

| After load 400 kPa | 2.122 | 2.718 | 2.803 | 2.680 | 0.771 | 0.732 | 1.022 | 0.918 |

| Density index ID = 0.65 | ||||||||

| After plunger load | 0.003 | 0.001 | 0.021 | 0.015 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| After load 25 kPa | 0.068 | 0.197 | 0.188 | 0.152 | 0.119 | 0.162 | 0.149 | 0.188 |

| After load 50 kPa | 0.190 | 0.349 | 0.324 | 0.292 | 0.221 | 0.278 | 0.272 | 0.302 |

| After load 100 kPa | 0.389 | 0.538 | 0.532 | 0.470 | 0.362 | 0.382 | 0.398 | 0.431 |

| After load 200 kPa | 0.639 | 0.722 | 0.850 | 0.748 | 0.517 | 0.490 | 0.518 | 0.553 |

| After load 400 kPa | 0.958 | 0.975 | 1.288 | 1.203 | 0.683 | 0.614 | 0.652 | 0.691 |

| Density index ID = 0.85 | ||||||||

| After plunger load | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| After load 25 kPa | 0.041 | 0.125 | 0.073 | 0.132 | 0.090 | 0.082 | 0.076 | 0.154 |

| After load 50 kPa | 0.109 | 0.229 | 0.158 | 0.263 | 0.166 | 0.163 | 0.141 | 0.266 |

| After load 100 kPa | 0.241 | 0.352 | 0.319 | 0.432 | 0.279 | 0.213 | 0.231 | 0.388 |

| After load 200 kPa | 0.421 | 0.535 | 0.576 | 0.694 | 0.399 | 0.281 | 0.325 | 0.509 |

| After load 400 kPa | 0.708 | 0.761 | 0.967 | 1.108 | 0.558 | 0.379 | 0.432 | 0.639 |

Note: The soil specimen deformation values represent the best estimates obtained by visual interpolation between dial divisions (0.01 mm resolution) to minimize rounding errors in the Eoed calculation.

Table A3.

Void ratio e after loading (Danube sand, Polanka sand).

Table A3.

Void ratio e after loading (Danube sand, Polanka sand).

| Voi Ratio e (-) | Danube Sand | Polanka Sand | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | A | B | C | D | |

| Density index ID = 0.15 | ||||||||

| No load | 1.152 | 1.152 | 1.152 | 1.152 | 0.699 | 0.699 | 0.699 | 0.699 |

| After plunger load | 1.146 | 1.142 | 1.141 | 1.148 | 0.699 | 0.699 | 0.699 | 0.699 |

| After load 25 kPa | 1.113 | 1.104 | 1.104 | 1.125 | 0.691 | 0.687 | 0.687 | 0.689 |

| After load 50 kPa | 1.090 | 1.073 | 1.076 | 1.094 | 0.683 | 0.681 | 0.680 | 0.682 |

| After load 100 kPa | 1.066 | 1.043 | 1.046 | 1.061 | 0.677 | 0.677 | 0.672 | 0.676 |

| After load 200 kPa | 1.041 | 1.004 | 1.011 | 1.022 | 0.671 | 0.673 | 0.665 | 0.668 |

| After load 400 kPa | 1.020 | 0.971 | 0.973 | 0.978 | 0.670 | 0.667 | 0.657 | 0.659 |

| Density index ID = 0.65 | ||||||||

| No load | 0.798 | 0.798 | 0.798 | 0.798 | 0.536 | 0.536 | 0.536 | 0.536 |

| After plunger load | 0.798 | 0.798 | 0.797 | 0.797 | 0.536 | 0.536 | 0.536 | 0.536 |

| After load 25 kPa | 0.794 | 0.787 | 0.787 | 0.791 | 0.530 | 0.528 | 0.529 | 0.529 |

| After load 50 kPa | 0.787 | 0.779 | 0.781 | 0.785 | 0.526 | 0.524 | 0.524 | 0.525 |

| After load 100 kPa | 0.778 | 0.770 | 0.773 | 0.777 | 0.520 | 0.520 | 0.522 | 0.521 |

| After load 200 kPa | 0.766 | 0.761 | 0.759 | 0.763 | 0.516 | 0.517 | 0.520 | 0.517 |

| After load 400 kPa | 0.756 | 0.750 | 0.738 | 0.739 | 0.515 | 0.514 | 0.517 | 0.512 |

| Density index ID = 0.85 | ||||||||

| No load | 0.656 | 0.656 | 0.656 | 0.656 | 0.471 | 0.471 | 0.471 | 0.471 |

| After plunger load | 0.656 | 0.656 | 0.656 | 0.656 | 0.471 | 0.471 | 0.471 | 0.471 |

| After load 25 kPa | 0.654 | 0.650 | 0.652 | 0.651 | 0.467 | 0.468 | 0.468 | 0.466 |

| After load 50 kPa | 0.651 | 0.645 | 0.649 | 0.646 | 0.464 | 0.465 | 0.466 | 0.462 |

| After load 100 kPa | 0.646 | 0.640 | 0.644 | 0.639 | 0.460 | 0.464 | 0.465 | 0.459 |

| After load 200 kPa | 0.639 | 0.633 | 0.635 | 0.627 | 0.457 | 0.463 | 0.465 | 0.455 |

| After load 400 kPa | 0.632 | 0.624 | 0.618 | 0.607 | 0.457 | 0.462 | 0.464 | 0.451 |

Table A4.

Normalized void ratio e/e0 (Danube sand, Polanka sand).

Table A4.

Normalized void ratio e/e0 (Danube sand, Polanka sand).

| Voi Ratio e (-) | Danube Sand | Polanka Sand | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | A | B | C | D | |

| Density index ID = 0.15 | ||||||||

| No load | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| After plunger load | 0.995 | 0.991 | 0.990 | 0.997 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| After load 25 kPa | 0.966 | 0.959 | 0.959 | 0.976 | 0.989 | 0.983 | 0.984 | 0.986 |

| After load 50 kPa | 0.946 | 0.931 | 0.934 | 0.950 | 0.978 | 0.975 | 0.973 | 0.977 |

| After load 100 kPa | 0.925 | 0.906 | 0.908 | 0.921 | 0.969 | 0.969 | 0.961 | 0.967 |

| After load 200 kPa | 0.903 | 0.872 | 0.877 | 0.887 | 0.961 | 0.963 | 0.952 | 0.956 |

| After load 400 kPa | 0.885 | 0.843 | 0.845 | 0.849 | 0.959 | 0.955 | 0.940 | 0.943 |

| Density index ID = 0.65 | ||||||||

| No load | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| After plunger load | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.998 | 0.999 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| After load 25 kPa | 0.995 | 0.986 | 0.987 | 0.992 | 0.989 | 0.985 | 0.987 | 0.986 |

| After load 50 kPa | 0.987 | 0.976 | 0.979 | 0.984 | 0.980 | 0.977 | 0.978 | 0.979 |

| After load 100 kPa | 0.975 | 0.965 | 0.969 | 0.974 | 0.971 | 0.970 | 0.973 | 0.971 |

| After load 200 kPa | 0.961 | 0.954 | 0.952 | 0.957 | 0.962 | 0.964 | 0.970 | 0.964 |

| After load 400 kPa | 0.948 | 0.941 | 0.925 | 0.927 | 0.960 | 0.959 | 0.965 | 0.955 |

| Density index ID = 0.85 | ||||||||

| No load | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| After plunger load | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| After load 25 kPa | 0.997 | 0.990 | 0.995 | 0.992 | 0.991 | 0.992 | 0.993 | 0.988 |

| After load 50 kPa | 0.992 | 0.984 | 0.990 | 0.985 | 0.984 | 0.986 | 0.989 | 0.981 |

| After load 100 kPa | 0.984 | 0.976 | 0.982 | 0.974 | 0.977 | 0.985 | 0.987 | 0.973 |

| After load 200 kPa | 0.974 | 0.964 | 0.969 | 0.956 | 0.970 | 0.982 | 0.987 | 0.965 |

| After load 400 kPa | 0.963 | 0.951 | 0.943 | 0.926 | 0.969 | 0.979 | 0.984 | 0.956 |

Table A5.

Oedometric moduli Eoed for various density index ID according to the STN, Danube sand.

Table A5.

Oedometric moduli Eoed for various density index ID according to the STN, Danube sand.

| Oed. and Param. | Oedometric Moduli Eoed Obtained from Oedometers A, B, C, and D and Their Descriptive Statistics (Standard and Robust Measures) for 5 Intervals of Loading (No. 1 to 5), Danube Sand | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Index ID = 0.15 | Density Index ID = 0.65 | Density Index ID = 0.85 | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Oedometric moduli obtained from oedometers | |||||||||||||||

| A | 1.327 | 2.340 | 4.421 | 8.590 | 20.999 | 9.686 | 6.810 | 9.449 | 15.915 | 35.785 | 15.894 | 13.262 | 16.257 | 25.198 | 44.143 |

| B | 1.174 | 1.700 | 3.655 | 5.509 | 13.012 | 3.292 | 5.896 | 9.614 | 21.410 | 33.357 | 5.381 | 9.434 | 16.587 | 21.563 | 39.205 |

| C | 1.127 | 1.876 | 3.652 | 6.041 | 11.532 | 3.943 | 7.100 | 11.010 | 13.387 | 16.882 | 9.888 | 13.566 | 16.696 | 18.306 | 19.417 |

| D | 1.870 | 1.748 | 3.258 | 5.527 | 9.780 | 6.526 | 7.277 | 11.665 | 12.896 | 14.836 | 6.962 | 7.959 | 12.526 | 13.829 | 16.476 |

| Standard descriptive statistics | |||||||||||||||

(MPa) | 1.397 | 1.916 | 3.747 | 6.417 | 13.831 | 5.862 | 6.771 | 10.435 | 15.902 | 25.215 | 9.531 | 11.055 | 15.517 | 19.724 | 29.810 |

| Range | 0.696 | 0.641 | 1.162 | 3.082 | 11.218 | 6.394 | 1.381 | 2.216 | 8.514 | 20.948 | 10.513 | 5.607 | 4.171 | 11.369 | 27.667 |

| SD | 0.322 | 0.292 | 0.487 | 1.470 | 4.958 | 2.907 | 0.614 | 1.079 | 3.903 | 10.881 | 4.635 | 2.792 | 2.003 | 4.834 | 13.899 |

| CV (%) | 23.04 | 15.26 | 12.99 | 22.91 | 35.85 | 49.59 | 9.07 | 10.34 | 24.54 | 43.15 | 48.63 | 25.26 | 12.91 | 24.51 | 46.62 |

| Robust descriptive statistics | |||||||||||||||

| Mdn | 1.272 | 1.812 | 3.654 | 5.784 | 12.272 | 5.235 | 6.955 | 10.312 | 14.651 | 25.119 | 8.425 | 11.348 | 16.422 | 19.934 | 29.311 |

| Q1 | 1.195 | 1.724 | 3.455 | 5.518 | 10.656 | 3.617 | 6.353 | 9.532 | 13.141 | 15.859 | 6.171 | 8.696 | 14.391 | 16.068 | 17.946 |

| Q3 | 1.599 | 2.108 | 4.038 | 7.316 | 17.005 | 8.106 | 7.188 | 11.388 | 18.662 | 34.571 | 12.891 | 13.414 | 16.642 | 23.381 | 41.674 |

| IQR | 0.403 | 0.384 | 0.582 | 1.798 | 6.349 | 4.489 | 0.835 | 1.806 | 5.521 | 18.712 | 6.720 | 4.718 | 2.250 | 7.313 | 23.728 |

| LF | 0.591 | 1.148 | 2.582 | 2.821 | 1.133 | −3.116 | 5.100 | 6.823 | 4.859 | −12.208 | −3.908 | 1.620 | 11.016 | 5.098 | −17.645 |

| UF | 2.204 | 2.684 | 4.911 | 10.013 | 26.529 | 14.839 | 8.441 | 14.046 | 26.944 | 62.638 | 22.971 | 20.049 | 20.017 | 34.350 | 77.266 |

| MAD | 0.077 | 0.088 | 0.198 | 0.266 | 1.616 | 1.617 | 0.233 | 0.780 | 1.509 | 9.260 | 2.253 | 2.066 | 0.220 | 3.446 | 11.365 |

| MiA | 0.488 | 4.049 | 2.611 | 7.109 | 3.642 | 1.856 | −0.419 | −0.746 | 0.565 | 0.777 | 2.236 | 0.625 | −0.506 | 1.030 | 0.880 |

| MiB | −0.861 | −0.861 | 0.004 | −0.697 | 0.309 | −0.810 | −3.062 | −0.603 | 3.020 | 0.600 | −0.911 | −0.625 | 0.506 | 0.319 | 0.587 |

| MiC | −0.488 | 0.488 | −0.004 | 0.652 | −0.309 | −0.539 | 0.419 | 0.603 | −0.565 | −0.600 | 0.438 | 0.724 | 0.843 | −0.319 | −0.587 |

| MiD | 5.272 | −0.488 | −1.345 | −0.652 | −1.040 | 0.539 | 0.930 | 1.170 | −0.784 | −0.749 | −0.438 | −1.106 | −11.960 | −1.195 | −0.762 |

| Eoed | 1.272 | 1.812 | 3.654 | 5.784 | 12.272 | 5.235 | 6.955 | 10.312 | 14.651 | 25.119 | 8.425 | 11.348 | 16.422 | 19.934 | 29.311 |

Table A6.

Oedometric moduli Eoed for various density index ID according to the ISO, Danube sand.

Table A6.

Oedometric moduli Eoed for various density index ID according to the ISO, Danube sand.

| Oed. and Param. | Oedometric Moduli Eoed Obtained from Oedometers A, B, C, and D and Their Descriptive Statistics (Standard and Robust Measures) for 5 Intervals of Loading (No. 1 to 5), Danube Sand | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Index ID = 0.15 | Density Index ID = 0.65 | Density Index ID = 0.85 | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Oedometric moduli obtained from oedometers | |||||||||||||||

| A | 1.323 | 2.297 | 4.292 | 8.243 | 19.906 | 9.685 | 6.795 | 9.394 | 15.737 | 35.160 | 15.894 | 13.245 | 16.205 | 25.040 | 43.691 |

| B | 1.169 | 1.662 | 3.520 | 5.230 | 12.118 | 3.292 | 5.859 | 9.513 | 21.074 | 32.677 | 5.381 | 9.397 | 16.479 | 21.357 | 38.649 |

| C | 1.210 | 1.834 | 3.523 | 5.744 | 10.774 | 3.940 | 7.058 | 10.906 | 13.200 | 16.520 | 9.888 | 13.537 | 16.630 | 18.179 | 19.176 |

| D | 1.867 | 1.726 | 3.170 | 5.293 | 9.189 | 6.523 | 7.250 | 11.583 | 12.749 | 14.553 | 6.961 | 7.935 | 12.449 | 13.690 | 16.190 |

| Standard descriptive statistics | |||||||||||||||

(MPa) | 1.392 | 1.880 | 3.626 | 6.127 | 12.997 | 5.860 | 6.741 | 10.349 | 15.690 | 24.728 | 9.531 | 11.029 | 15.441 | 19.566 | 29.427 |

| Range | 0.698 | 0.635 | 1.122 | 3.013 | 10.717 | 6.393 | 1.391 | 2.189 | 8.324 | 20.607 | 10.513 | 5.602 | 4.181 | 11.350 | 27.500 |

| SD | 0.323 | 0.287 | 0.474 | 1.429 | 4.759 | 2.907 | 0.617 | 1.071 | 3.823 | 10.691 | 4.635 | 2.795 | 2.002 | 4.818 | 13.769 |

| CV (%) | 23.21 | 15.28 | 13.07 | 23.32 | 36.62 | 49.61 | 9.15 | 10.35 | 24.36 | 43.24 | 48.63 | 25.34 | 12.97 | 24.62 | 46.79 |

| Robust descriptive statistics | |||||||||||||||

| Mdn | 1.267 | 1.780 | 3.521 | 5.518 | 11.446 | 5.232 | 6.927 | 10.210 | 14.468 | 24.599 | 8.425 | 11.321 | 16.342 | 19.768 | 28.913 |

| Q1 | 1.189 | 1.694 | 3.345 | 5.261 | 9.981 | 3.616 | 6.327 | 9.453 | 12.975 | 15.537 | 6.171 | 8.666 | 14.327 | 15.934 | 17.683 |

| Q3 | 1.595 | 2.066 | 3.907 | 6.994 | 16.012 | 8.104 | 7.154 | 11.245 | 18.405 | 33.919 | 12.891 | 13.391 | 16.555 | 23.199 | 41.170 |

| IQR | 0.406 | 0.372 | 0.562 | 1.732 | 6.031 | 4.488 | 0.827 | 1.791 | 5.431 | 18.382 | 6.720 | 4.725 | 2.228 | 7.264 | 23.487 |

| LF | 0.581 | 1.137 | 2.502 | 2.663 | 0.935 | −3.116 | 5.087 | 6.767 | 4.828 | −12.036 | −3.908 | 1.579 | 10.986 | 5.037 | −17.547 |

| UF | 2.204 | 2.623 | 4.751 | 9.592 | 25.058 | 14.836 | 8.395 | 13.931 | 26.551 | 61.491 | 22.970 | 20.478 | 19.896 | 34.095 | 76.400 |

| MAD | 0.077 | 0.086 | 0.176 | 0.257 | 1.464 | 1.616 | 0.228 | 0.756 | 1.494 | 9.062 | 2.253 | 2.070 | 0.213 | 3.431 | 11.230 |

| MiA | 0.494 | 4.055 | 2.953 | 7.156 | 3.897 | 1.859 | −0.389 | −0.728 | 0.573 | 0.786 | 2.236 | 0.627 | −0.434 | 1.037 | 0.888 |

| MiB | −0.855 | −0.926 | −0.005 | −0.757 | 0.310 | −0.810 | −3.163 | −0.621 | 2.983 | 0.601 | −0.911 | −0.627 | 0.434 | 0.312 | 0.585 |

| MiC | −0.494 | 0.423 | 0.005 | 0.592 | −0.310 | −0.539 | 0.389 | 0.621 | −0.573 | −0.601 | 0.438 | 0.722 | 0.915 | −0.312 | −0.585 |

| MiD | 5.233 | −0.423 | −1.344 | −0.592 | −1.039 | 0.539 | 0.960 | 1.225 | −0.776 | −0.748 | −0.438 | −1.103 | −12.336 | −1.195 | −0.764 |

| Eoed | 1.267 | 1.780 | 3.521 | 5.518 | 11.446 | 5.232 | 6.927 | 10.210 | 14.468 | 24.599 | 8.425 | 11.321 | 16.342 | 19.768 | 28.913 |

Table A7.

Oedometric moduli Eoed for various density index ID according to the STN, Polanka sand.

Table A7.

Oedometric moduli Eoed for various density index ID according to the STN, Polanka sand.

| Oed. and Param. | Oedometric Moduli Eoed Obtained from Oedometers A, B, C, and D and Their Descriptive Statistics (Standard and Robust Measures) for 5 Intervals of Loading (No. 1 to 5), Polanka Sand | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Index ID = 0.15 | Density Index ID = 0.65 | Density Index ID = 0.85 | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Oedometric moduli obtained from oedometers | |||||||||||||||

| A | 4.696 | 5.400 | 13.034 | 30.238 | 287.981 | 5.298 | 8.307 | 14.823 | 31.829 | 377.975 | 7.044 | 11.630 | 20.431 | 50.397 | 671.956 |

| B | 2.975 | 7.399 | 20.397 | 43.126 | 61.608 | 4.045 | 8.203 | 20.964 | 46.586 | 115.663 | 8.477 | 13.240 | 83.856 | 120.752 | 232.215 |

| C | 3.084 | 5.799 | 10.266 | 25.114 | 42.799 | 4.450 | 8.082 | 27.132 | 104.784 | 108.527 | 9.439 | 21.102 | 75.969 | 1012.917 | 209.569 |

| D | 3.500 | 6.822 | 13.061 | 21.831 | 37.732 | 4.262 | 9.672 | 18.636 | 37.732 | 64.343 | 5.594 | 9.923 | 20.375 | 38.204 | 70.260 |

| Standard descriptive statistics | |||||||||||||||

(MPa) | 3.564 | 6.355 | 14.190 | 30.077 | 107.530 | 4.514 | 8.566 | 20.389 | 55.233 | 166.627 | 7.639 | 13.974 | 50.158 | 305.567 | 296.000 |

| Range | 1.721 | 1.999 | 10.131 | 21.295 | 250.249 | 1.253 | 1.590 | 12.309 | 72.955 | 313.632 | 3.844 | 11.179 | 63.480 | 974.713 | 601.696 |

| SD | 0.788 | 0.918 | 4.341 | 9.362 | 120.738 | 0.548 | 0.743 | 5.159 | 33.586 | 142.715 | 1.681 | 4.942 | 34.508 | 472.968 | 260.892 |

| CV (%) | 22.11 | 14.45 | 30.59 | 31.13 | 112.28 | 12.15 | 8.67 | 25.30 | 60.81 | 85.65 | 22.01 | 35.36 | 68.80 | 154.78 | 88.06 |

| Robust descriptive statistics | |||||||||||||||

| Mdn | 3.292 | 6.311 | 13.047 | 27.676 | 52.204 | 4.356 | 8.255 | 19.800 | 42.159 | 112.095 | 7.761 | 12.435 | 48.200 | 85.574 | 220.892 |

| Q1 | 3.030 | 5.599 | 11.650 | 23.472 | 40.266 | 4.153 | 8.143 | 16.729 | 34.781 | 86.435 | 6.319 | 10.777 | 20.403 | 44.300 | 139.914 |

| Q3 | 4.098 | 7.111 | 16.729 | 36.682 | 174.795 | 4.874 | 8.989 | 24.048 | 75.685 | 246.819 | 8.958 | 17.171 | 79.912 | 566.834 | 452.085 |

| IQR | 1.069 | 1.511 | 5.079 | 13.210 | 134.529 | 0.720 | 0.847 | 7.319 | 40.905 | 160.384 | 2.639 | 6.395 | 59.509 | 522.534 | 312.171 |

| LF | 1.427 | 3.333 | 4.031 | 3.658 | −161.528 | 3.073 | 6.872 | 5.751 | −26.576 | −154.141 | 2.631 | 1.184 | −68.860 | −739.501 | −328.342 |

| UF | 5.701 | 9.377 | 24.438 | 56.496 | 376.588 | 5.954 | 10.260 | 35.026 | 137.042 | 487.395 | 12.916 | 26.764 | 169.176 | 1350.636 | 920.342 |

| MAD | 0.262 | 0.711 | 1.398 | 4.204 | 11.938 | 0.202 | 0.113 | 3.071 | 7.378 | 25.660 | 1.197 | 1.659 | 27.797 | 41.274 | 80.978 |

| MiA | 3.608 | −0.864 | −0.007 | 0.411 | 13.321 | 3.140 | 0.311 | −1.093 | −0.944 | 6.989 | −0.404 | −0.327 | −0.674 | −0.575 | 3.757 |

| MiB | −0.814 | 1.032 | 3.547 | 2.479 | 0.531 | −1.037 | −0.311 | 0.256 | 0.405 | 0.094 | 0.404 | 0.327 | 0.865 | 0.575 | 0.094 |

| MiC | −0.535 | −0.485 | −1.342 | −0.411 | −0.531 | 0.312 | −1.038 | 1.610 | 5.725 | −0.094 | 0.945 | 3.525 | 0.674 | 15.155 | −0.094 |

| MiD | 0.535 | 0.485 | 0.007 | −0.938 | −0.818 | −0.312 | 8.480 | −0.256 | −0.405 | −1.255 | −1.221 | −1.022 | −0.675 | −0.774 | −1.255 |

| Eoed | 3.292 | 6.311 | 13.047 | 27.676 | 52.204 | 4.356 | 8.255 | 19.800 | 42.159 | 112.095 | 7.761 | 12.435 | 48.200 | 85.574 | 220.892 |

Table A8.

Oedometric moduli Eoed for various density index ID according to the ISO, Polanka sand.

Table A8.

Oedometric moduli Eoed for various density index ID according to the ISO, Polanka sand.

| Oed. and Param. | Oedometric Moduli Eoed Obtained from Oedometers A, B, C, and D and Their Descriptive Statistics (Standard and Robust Measures) for 5 Intervals of Loading (No. 1 to 5), Polanka Sand | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Density Index ID = 0.15 | Density Index ID = 0.65 | Density Index ID = 0.85 | |||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Oedometric moduli obtained from oedometers | |||||||||||||||

| A | 4.696 | 5.376 | 12.916 | 29.849 | 283.324 | 5.298 | 8.275 | 14.720 | 31.502 | 372.900 | 7.044 | 11.596 | 20.327 | 50.017 | 665.556 |

| B | 2.975 | 7.348 | 20.187 | 42.576 | 60.680 | 4.045 | 8.161 | 20.793 | 46.096 | 114.196 | 8.477 | 13.208 | 83.492 | 120.156 | 230.877 |

| C | 3.084 | 5.760 | 10.153 | 24.715 | 41.950 | 4.450 | 8.045 | 26.923 | 103.784 | 107.387 | 9.438 | 21.056 | 75.711 | 1008.817 | 208.700 |

| D | 3.500 | 6.782 | 12.936 | 21.539 | 37.054 | 4.262 | 9.625 | 18.498 | 37.352 | 63.524 | 5.594 | 9.886 | 20.249 | 37.873 | 69.467 |

| Standard descriptive statistics | |||||||||||||||

(MPa) | 3.564 | 6.317 | 14.048 | 29.670 | 105.752 | 4.514 | 8.527 | 20.234 | 54.684 | 164.502 | 7.638 | 13.936 | 49.945 | 304.215 | 293.650 |

| Range | 1.721 | 1.972 | 10.034 | 21.037 | 246.269 | 1.253 | 1.581 | 12.203 | 72.282 | 309.376 | 3.844 | 11.170 | 63.243 | 970.944 | 596.089 |

| SD | 0.788 | 0.908 | 4.296 | 9.260 | 118.818 | 0.548 | 0.739 | 5.114 | 33.279 | 140.735 | 1.681 | 4.936 | 34.392 | 471.132 | 258.024 |

| CV (%) | 22.11 | 14.38 | 30.58 | 31.21 | 112.36 | 12.15 | 8.66 | 25.28 | 60.86 | 85.55 | 22.01 | 35.42 | 68.86 | 154.87 | 87.87 |

| Robust descriptive statistics | |||||||||||||||

| Mdn | 3.292 | 6.271 | 12.926 | 27.282 | 51.315 | 4.356 | 8.218 | 19.646 | 41.724 | 110.792 | 7.761 | 12.402 | 48.019 | 85.086 | 219.788 |

| Q1 | 3.029 | 5.568 | 11.535 | 23.127 | 39.502 | 4.153 | 8.103 | 16.609 | 34.427 | 85.456 | 6.319 | 10.741 | 20.288 | 43.945 | 139.083 |

| Q3 | 4.098 | 7.065 | 16.562 | 36.212 | 172.002 | 4.874 | 8.950 | 23.858 | 74.940 | 243.548 | 8.958 | 17.132 | 79.601 | 594.486 | 448.216 |

| IQR | 1.069 | 1.497 | 5.027 | 13.085 | 132.500 | 0.720 | 0.847 | 7.249 | 40.513 | 158.092 | 2.639 | 6.391 | 59.314 | 520.542 | 309.133 |

| LF | 1.427 | 3.323 | 3.994 | 3.499 | −159.247 | 3.073 | 6.832 | 5.736 | −26.343 | −151.682 | 2.361 | 1.155 | −68.683 | −736.868 | −324.616 |

| UF | 5.701 | 9.310 | 24.102 | 55.840 | 370.751 | 5.954 | 10.221 | 34.731 | 135.710 | 480.686 | 12.916 | 26.718 | 168.572 | 1345.299 | 911.916 |

| MAD | 0.262 | 0.703 | 1.392 | 4.155 | 11.813 | 0.202 | 0.115 | 3.036 | 7.297 | 25.336 | 1.197 | 1.661 | 27.731 | 41.142 | 80.705 |

| MiA | 3.608 | −0.859 | −0.005 | 0.417 | 13.248 | 3.138 | 0.332 | −1.094 | −0.945 | 6.978 | −0.404 | −0.327 | −0.674 | −0.575 | 3.726 |

| MiB | −0.814 | 1.033 | 3.519 | 2.483 | 0.535 | −1.037 | −0.332 | 0.255 | 0.404 | 0.091 | 0.404 | 0.327 | 0.863 | 0.575 | 0.093 |

| MiC | −0.535 | −0.490 | −1.344 | −0.417 | −0.535 | 0.312 | −1.017 | 1.616 | 5.737 | −0.091 | 0.945 | 3.515 | 0.674 | 15.144 | −0.093 |

| MiD | 0.535 | 0.490 | 0.005 | −0.932 | −0.814 | −0.312 | 8.247 | −0.255 | −0.404 | −1.258 | −1.221 | −1.022 | −0.675 | −0.774 | −1.256 |

| Eoed | 3.292 | 6.271 | 12.926 | 27.282 | 51.315 | 4.356 | 8.218 | 19.646 | 41.724 | 110.792 | 7.761 | 12.402 | 48.019 | 85.086 | 219.788 |

Appendix A.2. Sample Preparation Procedure

At the beginning, 54,886.295 g of Danube sand with particles smaller than 2 mm was prepared from one quarter of the total sample obtained using the quartering method. The quartering method was then applied again to obtain a subsample of 27,443.148 g (half of the previous portion), which was subsequently divided into four parts, each weighing 6860.787 g. This subsample was divided into three portions (1962.012 g + 2348.840 g + 2549.953 g). The portion of 1962.012 g corresponds to 110% of the total mass of soil required for oedometers A, B, C, and D at ID = 0.15. The 1962.012 g portion was then divided into four parts (by estimation at the table), from which the following amounts were weighed: 444.604 g (for oedometer A), 444.771 g (for oedometer B), 447.904 g (for oedometer C), and 446.368 g (for oedometer D). In total, 1783.647 g was weighed out. The difference 1962.012 g − 1783.647 g = 178.365 g (remaining 10%) was collected from the remaining portions after weighing for each oedometer. This remaining portion was created to allow the exact amount of soil required for each oedometer to be weighed from each of the four parts with minimal handling of the others. Afterwards, this remaining portion was set aside and not used further. In a similar way, the soil masses for oedometers A, B, C, and D were prepared for ID = 0.65 (from 2348.840 g) and ID = 0.85 (from 2549.953 g). The same procedure was repeated for the Polanka sand.

The amount of 444.604 g is then divided into a quarter (111.151 g), a half (222.302 g), and a quarter (111.151 g), which are subsequently compacted into oedometer A—first, the first quarter (up to one quarter of the oedometer height), then the half (up to three quarters of the oedometer height), and finally the last quarter (up to the surface of the oedometer). After compacting each layer using a metal compactor, the surface of the layer is lightly loosened using a brush with a diameter of 12 cm. This procedure is applied in all other tests.

References

- Głuchowski, A.; Šadzevičius, R.; Skominas, R.; Sas, W. Compacted Anthropogenic Materials as Backfill for Buried Pipes. Materials 2021, 14, 717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Sun, J.; Qi, Y.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, X.; Liang, R.; Chen, H. Study on Stiffness Parameters of the Hardening Soil Model in Sandy Gravel Stratum. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 2710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samui, P.; Hoang, N.-D.; Nhu, V.-H.; Nguyen, M.-L.; Ngo, P.T.T.; Bui, D.T. A New Approach of Hybrid Bee Colony Optimized Neural Computing to Estimate the Soil Compression Coefficient for a Housing Construction Project. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EN 1997-2:2010; Eurocode 7—Geotechnical design—Part 2: Ground investigation and testing. European Committee for Standardization: Brussels, Belgium, 2010.

- STN 73 1001: 2000; Geotechnické konštrukcie. Zakladanie stavieb [Geotechnical structures. Foundation]. Slovak Institute of Technical Standardization: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2000.

- PN-81/B-03020; Grunty Budowlane. Posadowienie Bezpośrednie Budowli. Obliczenia Statyczne i Projektowanie [Building Soils. Foundation Bases. Static Calculation and Design]. Polish Committee for Standardization, Measures and Quality: Warsaw, Poland, 1981.

- Werner, D.; Burnier, C.; Yu, Y.; Marolf, A.R.; Wang, Y.; Massonnet, G. Identification of some factors influencing soil transfer on shoes. Sci. Justice 2019, 59, 643–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bull, P.A.; Parker, A.; Morgan, R.M. The forensic analysis of soils and sediment taken from the cast of a footprint. Forensic Sci. Int. 2006, 162, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, H.J.; Bennett, M.R. Recovery of 3D footwear impressions using a range of different techniques. J. Forensic Sci. 2021, 66, 1056–1064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, A.J.; Jasra, S. Effect of soil moisture on shoe impression detail and longevity. J. Emerg. Forensic Sci. Res. 2021, 6, 117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Charron, J.; Currier, C.; Hess, P.; Jacobs, P.; Zerbe, J. Interpol Review Paper of Marks and Impression Evidence 2019–2022. Forensic Sci. Int. Synerg. 2023, 6, 100308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ISO 17892-5:2017 (confirmed 2022); Geotechnical investigation and testing—Laboratory testing of soil—Part 5: Incremental loading oedometer test. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- PN-88/B-04481; Building Soils—Laboratory Tests. Alfa Publishing House: Warsaw, Poland, 1988.

- STN 72 1027: 1983; Laboratórne stanovenie stlačiteľnosti zemín v edometri [Laboratory Determination of Soil Compressibility in the Oedometer Apparatus]. ÚNM Publishing House: Prague, Czech Republic, 1983.

- ASTM D2435/D2435M-11; Standard Test Methods for One-Dimensional Consolidation Properties of Soils Using Incremental Loading. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2011.

- STN EN ISO 17892-1: 2023; Geotechnical investigation and testing—Laboratory testing of soil—Part 1: Determination of water content. Slovak Office of Standards, Metrology and Testing: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2023.

- STN EN ISO 17892-4: 2023; Geotechnical investigation and testing—Laboratory testing of soil—Part 4: Determination of particle size distribution. Slovak Office of Standards, Metrology and Testing: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2023.

- STN EN ISO 17892-12: 2019; Geotechnical investigation and testing—Laboratory testing of soil—Part 12: Determination of liquid and plastic limits. Slovak Office of Standards, Metrology and Testing: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2019.

- Iglewicz, B.; Hoaglin, D.C. How to Detect and Handle Outliers. In The ASQC Basic References in Quality Control: Statistical Techniques, 1st ed.; Mykytka, E.F., Ed.; ASQC Quality Press: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 1993; Volume 16, pp. 1–85. [Google Scholar]

- Hinkle, D.E.; Wiersma, W.; Jurs, S.G. Applied Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences, 5th ed.; Houghton Mifflin: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; 746p. [Google Scholar]

- STN 72 1030: 1988; Laboratory Direct Shear Box Drained Test of Soils. ÚNM Publishing House: Prague, Czech Republic, 1988.

- Greco, V.R. Variability and correlation of strength parameters inferred from direct shear tests. Geotech. Geol. Eng. 2016, 34, 585–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, N.C.; Fonini, A.; Maghous, S.; Schnaid, F. Experimental Analysis of the Mechanical Properties of Artificially Cemented Soils and Their Evolution in Time. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering, Paris, France, 2–6 September 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stones, Sandpits and Limestone Quarries in the Czech Republic. Available online: http://kamenolomy.fzp.ujep.cz/index.php?page=record&id=328&tab=chem (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Bzowka, J.; Nguyen, G. The differences in determination of soil deformation characteristics between European Document, Polish and Slovak Standards. Zesz. Nauk. Politech. Białost. Bud. 2006, 28, 45–57. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).