Application of Machine Learning Method for Hardness Prediction of Metal Materials Fabricated by 3D Selective Laser Melting

Featured Application

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Work and Material Preparation

2.2. Methodology of Structure Characterization

2.2.1. Fractals

2.2.2. Modeling

- 100 for the maximum number of generations;

- 500 for the size of the population of organisms;

- 0.5 for the reproduction probability;

- 0.6 for the crossover probability;

- 6 for the maximum permissible depth in creation of the population;

- 10 for the maximum permissible depth after the operation of crossover of two organisms;

- and 2 for the smallest permissible depth of organisms in generating new organisms.

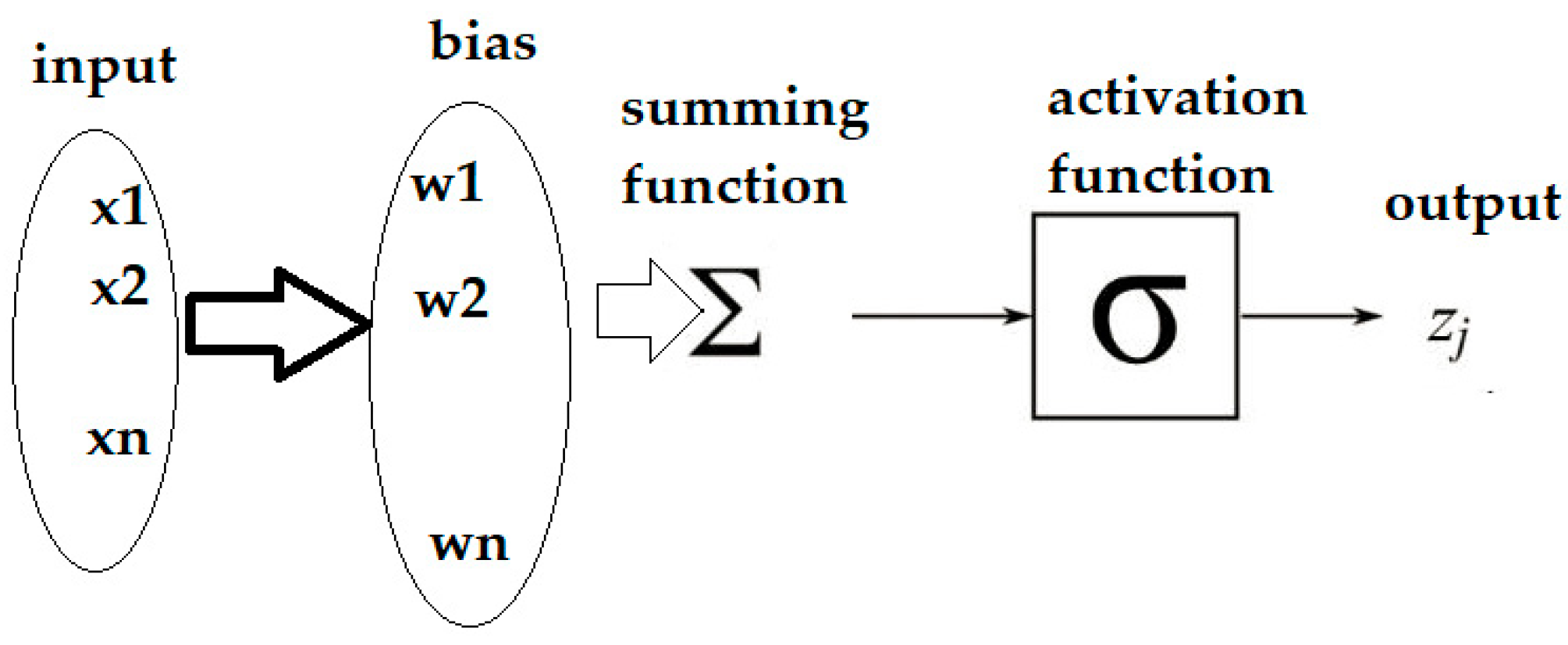

- Number of neurons per hidden layer: 100;

- Activation function: 100;

- Solver: SGD, Alpha 0.0001;

- Max iterations: 200.

- SVM, Cost (C): 1,00;

- Regression loss epsilon: 0.1;

- Kernel: RBF;

- Optimization parameters: Numerical tolerance: 0.001;

- Iteration limit: 100.

- Number of trees: 10;

- Number of attributes considered at each split: 5;

- Growth control: Do not split subsets smaller than 5.

2.2.3. Training and Validation Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| AM | Additive manufacturing |

| BPNN | Backpropagation neural networks |

| FD | Fractal dimension |

| GA | Genetic algorithms |

| GBDT | Gradient boosting decision tree |

| GP | Genetic programming |

| GVBN | Gaussian Variational Bayes Network |

| IST | Intelligent system techniques |

| kNN | k-nearest neighbors |

| MR | Multiple regression |

| MPB | Melt pool boundaries |

| MSE | Mean square error |

| NN | Neural network |

| OSBD | Orthotropic steel bridge decks |

| RF | Random forest |

| RSM | Response surface methodology |

| RTDW | Rib-to-deck welds |

| SLM | Selective laser melting |

| SVM | Support vector machine |

| VED | Volumetric energy density |

References

- Wawryniuk, Z.; Brancewicz-Steinmetz, E.; Sawicki, J. Revolutionizing transportation: An overview of 3D printing in aviation, automotive, and space industries. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2024, 134, 3083–3105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prashar, G.; Vasudev, H.; Bhuddhi, D. Additive manufacturing: Expanding 3D printing horizon in industry 4.0. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2023, 17, 2221–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lashgari, H.R.; Ferry, M.; Li, S. Additive manufacturing of bulk metallic glasses: Fundamental principle, current/future developments and applications. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 2022, 119, 131–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Król, M.; Snopiński, P.; Czech, A. The phase transitions in selective laser-melted 18-NI (300-grade) maraging steel. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2020, 142, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.; Silva, F.; Xavier, J.; Gregório, A.; Reis, A.; Rosa, P.; Konopík, P.; Rund, M.; Jesus, A. Mechanical Behaviour of Maraging Steel Produced by SLM. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2021, 34, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Dong, C.; Kong, D.; Wang, L.; Ni, X.; Zhang, L.; Wu, W.; Zhu, L.; Li, X. Influence of pore defects on the mechanical property and corrosion behavior of SLM 18Ni300 maraging steel. Mater. Charact. 2021, 182, 111514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, V.V.; Mohanty, C.P.; Prashanth, K.G. Selective laser melting of a novel 13Ni400 maraging steel: Material characterization and process optimization. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 3979–3995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.H.; Ha, S.Y.; Song, G.; Cho, J.; Kim, K.B.; Park, H.J.; Kang, G.C.; Park, J.M. Correlation between micro-to-macro mechanical properties and processing parameters on additive manufactured 18Ni-300 maraging steels. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 960, 171031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, D.; Ulbrich, D.; Stachowiak, A.; Bartkowski, D.; Bartkowska, A.; Petru, J.; Hajnyš, J.; Popielarski, P. Mechanical, corrosion and tribocorrosion resistance of additively manufactured Maraging C300 steel. Tribol. Int. 2024, 195, 109604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetková, I.; Thurnwald, P.; Bohdan, P.; Trojan, K., Jr.; Čapek, J.; Ganev, N.; Zetek, M.; Kepka, M.; Kepka, M.; Houdková, Š. Improving of mechanical properties of printed maraging steel. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2024, 54, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyczyński, P.; Siemiątkowski, Z.; Bąk, P.; Warzocha, K.; Rucki, M.; Szumiata, T. Performance of Maraging Steel Sleeves Produced by SLM with Subsequent Age Hardening. Materials 2020, 13, 3408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marciniak, Z.; Branco, R.; Macek, W.; Malça, C. Fatigue behaviour of SLM maraging steel under variable-amplitude loading. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2024, 56, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, R.; Silva, J.; Martins Ferreira, J.; Costa, J.D.; Capela, C.; Berto, F.; Santos, L.; Antunes, F.V. Fatigue behaviour of maraging steel samples produced by SLM under constant and variable amplitude loading. Procedia Struct. Integr. 2019, 22, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Deng, D.; Zhai, Z.; Yao, Y. Laser-processed functional surface structures for multi-functional applications—A review. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 116, 247–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lu, Q.; Zhang, P.; Yan, H.; Shi, H.; Sun, T.; Zhou, K.; Chen, K. A review on the simulation of selective laser melting AlSi10Mg. Opt. Laser Technol. 2024, 174, 110500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolomy, S.; Jopek, M.; Sedlak, J.; Benc, M.; Zouhar, J. Study of dynamic behaviour via Taylor anvil test and structure observation of M300 maraging steel fabricated by the selective laser melting method. J. Manuf. Process. 2024, 125, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, H.; Paul, M.J.; He, P.; Peng, Z.; Gludovatz, B.; Kruzic, J.J.; Wang, C.H.; Li, X. Machine-learning assisted laser powder bed fusion process optimization for AlSi10Mg: New microstructure description indices and fracture mechanisms. Acta Mater. 2020, 201, 316–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, P.; Zamani, M.; Mostafaei, A. Machine learning prediction of mechanical properties in metal additive manufacturing. Addit. Manuf. 2024, 91, 104320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarker, I.H. Machine Learning: Algorithms, Real-World Applications and Research Directions. SN Comput. Sci. 2021, 2, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrionuevo, G.O.; Walczak, M.; Ramos-Grez, J.; Sánchez-Sánchez, X. Microhardness and wear resistance in materials manufactured by laser powder bed fusion: Machine learning approach for property prediction. CIRP J. Manuf. Sci. Technol. 2023, 43, 106–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherkhani, K.; Ero, O.; Liravi, F.; Toorandaz, S.; Toyserkani, E. On the application of in-situ monitoring systems and machine learning algorithms for developing quality assurance platforms in laser powder bed fusion: A review. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 99, 848–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Deng, Y.; Chen, F.; Luo, Y.; Xiao, X.; Lu, N.; Liu, Y.; Deng, Y. Fatigue life prediction for orthotropic steel bridge decks welds using a Gaussian variational bayes network and small sample experimental data. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 264 Pt B, 111406, ISSN 0951-8320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González Morales, S.R.; Yamada, K.M. Cell and matrix dynamics in branching morphogenesis. In Principles of Tissue Engineering, 5th ed.; Lanza, R., Langer, R., Vacanti, J.P., Atala, A., Eds.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 217–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macek, W.; Branco, R.; Podulka, P.; Kopec, M.; Zhu, S.-P.; Costa, J.D. A brief note on entire fracture surface topography parameters for 18Ni300 maraging steel produced by LB-PBF after LCF. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 153, 107541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Cao, H.; Qu, D.; Yi, H.; Kang, X.; Huang, X.; Zhou, J.; Yan, C. Surface integrity optimization of high speed dry milling UD-CF/PEEK based on specific cutting energy distribution mechanisms effected by impact and size effect. J. Manuf. Process. 2022, 79, 731–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Li, C.; Zhang, C.; Han, B.; Wang, Z.; Fan, W.; Xu, Z. Process parameter optimisation method based on data-driven prediction model and multi-objective optimisation for the laser metal deposition manufacturing process monitoring. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2025, 204, 111108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, J.; Li, R.; Xie, J.; Zhou, X.; Li, X.; Liu, Q.; Chen, X.; Shen, W.; Wang, L. Federated learning-empowered smart manufacturing and product lifecycle management: A review. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2025, 65 Pt A, 103179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandarkar, V.V.; Broteen Das, B.; Tandon, P. Real-time remote monitoring and defect detection in smart additive manufacturing for reduced material wastage. Measurement 2025, 252, 117362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EOS M 290. Available online: https://www.eos.info/metal-solutions/metal-printers/eos-m-290#key-features (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- EOS Maraging Steel MS1 M400-4: Material Data Sheet. Available online: https://www.eos.info/metal-solutions/metal-materials/data-sheets/mds-eos-maragingsteel-ms1 (accessed on 11 March 2025).

- Owsiński, R.; Miozga, R.; Łagoda, A.; Kurek, M. Mechanical Properties of X3NiCoMoTi 18-9-5 Produced via Additive Manufacturing Technology—Numerical and Experimental Study. Adv. Sci. Technol. Res. J. 2024, 18, 45–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bochnia, J.; Kozior, T.; Zyz, J. The Mechanical Properties of Direct Metal Laser Sintered Thin-Walled Maraging Steel (MS1) Elements. Materials 2023, 16, 4699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, J.; Zhou, G.; Wang, W.; Hu, Q.; Jiang, Z.; Yang, K. Understanding the effect of cobalt on the precipitation hardening behavior of the maraging stainless steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 6719–6728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mooney, B.; Kourousis, K.I. A Review of Factors Affecting the Mechanical Properties of Maraging Steel 300 Fabricated via Laser Powder Bed Fusion. Metals 2020, 10, 1273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swain, S.; Datta, S.; Roy, T. Microstructure and Mechanical Property Characterization of Additively Manufactured Maraging Steel 18Ni(300) Built Part. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, M.; Li, H.; Li, Q.; Liu, J. Influence of layer thickness and heat treatment on microstructure and properties of selective laser melted maraging stainless steel. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 33, 3911–3927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durmaz, A.R.; Müller, M.; Lei, B.; Thomas, A.; Britz, D.; Holm, E.A.; Eberl, C.; Mücklich, F.; Gumbsch, P. A deep learning approach for complex microstructure inference. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 6272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsson, C. Self-Similarity, Fractality, and Chaos. In 5G Networks; Larsson, C., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2018; pp. 67–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, B.K.; Kovacs, K.D.; Adelman, R.A. Fractal Dimension Analysis of Widefield Choroidal Vasculature as Predictor of Stage of Macular Degeneration. Transnatl. Vis. Sci. Technol. 2020, 9, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gómez-Águila, A.; Trinidad-Segovia, J.E.; Sánchez-Granero, M.A. Improvement in Hurst exponent estimation and its application to financial markets. Financ. Innov. 2022, 8, 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babič, M.; Kokol, P.; Guid, N.; Panjan, P. A new method for estimating the Hurst exponent H for 3D objects. Mater. Technol. 2014, 48, 203–208. [Google Scholar]

- Kovačič, M.; Zupanc, A.; Župerl, U.; Brezočnik, M. Reducing scrap in long rolled round steel bars using Genetic Programming after ultrasonic testing. Adv. Prod. Eng. Manag. 2024, 19, 435–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prieto, A.; Prieto, B.; Ortigosa, E.M.; Ros, E.; Pelayo, F.; Ortega, J.; Rojas, I. Neural networks: An overview of early research, current frameworks and new challenges. Neurocomputing 2016, 214, 242–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, F.S.; Casas-Roma, J.; Subirats, L.; Parada, R. Spiking neural networks for autonomous driving: A review. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 138 Pt B, 109415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanthi, D.; Madhuravani, B.; Kumar, A. (Eds.) Handbook of Artificial Intelligence; Bentham Publishers: Singapore, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Arkes, J. Regression Analysis: A Practical Introduction, 2nd ed.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, H.N.; LaFave, S.; Marineau, L.; Stephens, J.; Thorpe, R.J. The impact of discrimination on allostatic load in adults: An integrative review of literature. J. Psychosom. Res. 2021, 146, 110434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, A.; Nagaraj, N. Augmented regression models using neurochaos learning. Chaos Solitons Fractals 2025, 201 Pt 2, 117213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halder, R.K.; Uddin, M.N.; Uddin, M.A.; Aryal, S.; Khraisat, A. Enhancing K-nearest neighbor algorithm: A comprehensive review and performance analysis of modifications. J. Big Data 2024, 11, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, S. Support Vector Machines for Pattern Classification; Springer: London, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pochiraju, B.; Kollipara, H.S.S. Statistical Methods: Regression Analysis. In Essentials of Business Analytics; Pochiraju, B., Seshadri, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 179–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powell, R.T. Computational precision therapeutics and drug repositioning. In Comprehensive Precision Medicine; Ramos, K.S., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; Volume 1, pp. 57–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, H.A.; Kalakech, A.; Steiti, A. Random Forest Algorithm Overview. Babylon. J. Mach. Learn. 2024, 2024, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobesova, Z. Evaluation of Orange data mining software and examples for lecturing machine learning tasks in geoinformatics. Comput. Appl. Eng. Educ. 2024, 32, e22735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandan, B.; Manikandan, M. Machine learning approach with various regression models for predicting the ultimate tensile strength of the friction stir welded AA 2050-T8 joints by the K-Fold cross-validation method. Mater. Today Commun. 2023, 34, 105286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogunsanya, M.; Isichei, J.; Desai, S. Grid search hyperparameter tuning in additive manufacturing processes. Manuf. Lett. 2023, 35 (Supplement), 1031–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salcedo-Sanz, S.; Casillas-Pérez, D.; Del Ser, J.; Casanova-Mateo, C.; Cuadra, L.; Piles, M.; Camps-Valls, G. Persistence in complex systems. Phys. Rep. 2022, 957, 1–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, H.; Wang, K.; Xu, K.; Lou, M.; Kan, G.; Jia, Q.; Li, C.; Xiao, X.; Chang, K. Machine learning-assisted prediction of mechanical properties in WC-based composites with multicomponent alloy binders. Compos. Part B Eng. 2025, 299, 112389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Specimen | X1 Power, W | X2 Speed, mm/s | X3 FD | Hardness HV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 320 | 1000 | 2.423 | 354.7 |

| S2 | 320 | 1150 | 2.424 | 362.7 |

| S3 | 320 | 1300 | 2.430 | 376.0 |

| S4 | 270 | 850 | 2.418 | 356.7 |

| S5 | 270 | 1000 | 2.431 | 370.8 |

| S6 | 270 | 1150 | 2.434 | 350.8 |

| S7 | 270 | 1300 | 2.439 | 382.6 |

| S8 | 220 | 700 | 2.460 | 351.8 |

| S9 | 220 | 850 | 2.450 | 374.2 |

| S10 | 220 | 1000 | 2.439 | 373.2 |

| S11 | 220 | 1150 | 2.485 | 358.7 |

| S12 | 220 | 1300 | 2.456 | 380.2 |

| S13 | 170 | 700 | 2.404 | 380.5 |

| S14 | 170 | 850 | 2.327 | 366.5 |

| S15 | 170 | 1000 | 2.450 | 374.6 |

| S16 | 170 | 1150 | 2.380 | 366.8 |

| S17 | 170 | 1300 | 2.441 | 363.4 |

| Specimen | GP | MR | RF | NN | k-NN | SVM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1 | 355.6 | 364.5 | 376.0 | 356.7 | 376.0 | 380.0 |

| S2 | 365.8 | 363.5 | 376.0 | 376.0 | 376.0 | 376.0 |

| S3 | 377.5 | 366.3 | 362.7 | 354.7 | 363.4 | 362.7 |

| S4 | 357.3 | 361.9 | 380.0 | 354.7 | 362.7 | 380.0 |

| S5 | 366.0 | 364.1 | 373.0 | 354.7 | 354.7 | 380.0 |

| S6 | 367.3 | 364.4 | 382.6 | 376.0 | 382.6 | 380.0 |

| S7 | 380.9 | 368.7 | 370.8 | 376.0 | 350.8 | 380.0 |

| S8 | 352.7 | 361.3 | 380.0 | 380.0 | 374.2 | 380.0 |

| S9 | 373.8 | 365.4 | 356.7 | 351.8 | 373.0 | 351.8 |

| S10 | 367.2 | 368.0 | 374.6 | 380.0 | 374.2 | 380.0 |

| S11 | 362.5 | 371.2 | 374.2 | 363.4 | 380.0 | 380.0 |

| S12 | 377.2 | 372.6 | 358.7 | 363.4 | 363.4 | 363.4 |

| S13 | 350.5 | 365.9 | 366.8 | 366.5 | 351.8 | 374.2 |

| S14 | 364.0 | 368.9 | 366.8 | 366.8 | 380.0 | 380.0 |

| S15 | 370.6 | 369.5 | 373.0 | 363.4 | 366.5 | 373.0 |

| S16 | 369.6 | 375.8 | 380.0 | 366.5 | 380.0 | 380.0 |

| S17 | 365.6 | 371.3 | 380.0 | 374.6 | 382.6 | 380.0 |

| GP | MR | RF | NN | k-NN | SVM | LR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average | 0.987 | 0.977 | 0.960 | 0.968 | 0.955 | 0.957 | 0.970 |

| Max | 0.999 * | 0.998 | 0.999 * | 0.999 * | 0.997 | 0.996 | 0.994 |

| Min | 0.922 | 0.961 | 0.909 ** | 0.920 | 0.909 ** | 0.917 | 0.928 |

| Range | 0.077 | 0.037 | 0.090 | 0.079 | 0.087 | 0.079 | 0.066 |

| Median | 0.993 | 0.976 | 0.963 | 0.969 | 0.957 | 0.963 | 0.979 |

| GP | MR | RF | NN | k-NN | SVM | LR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

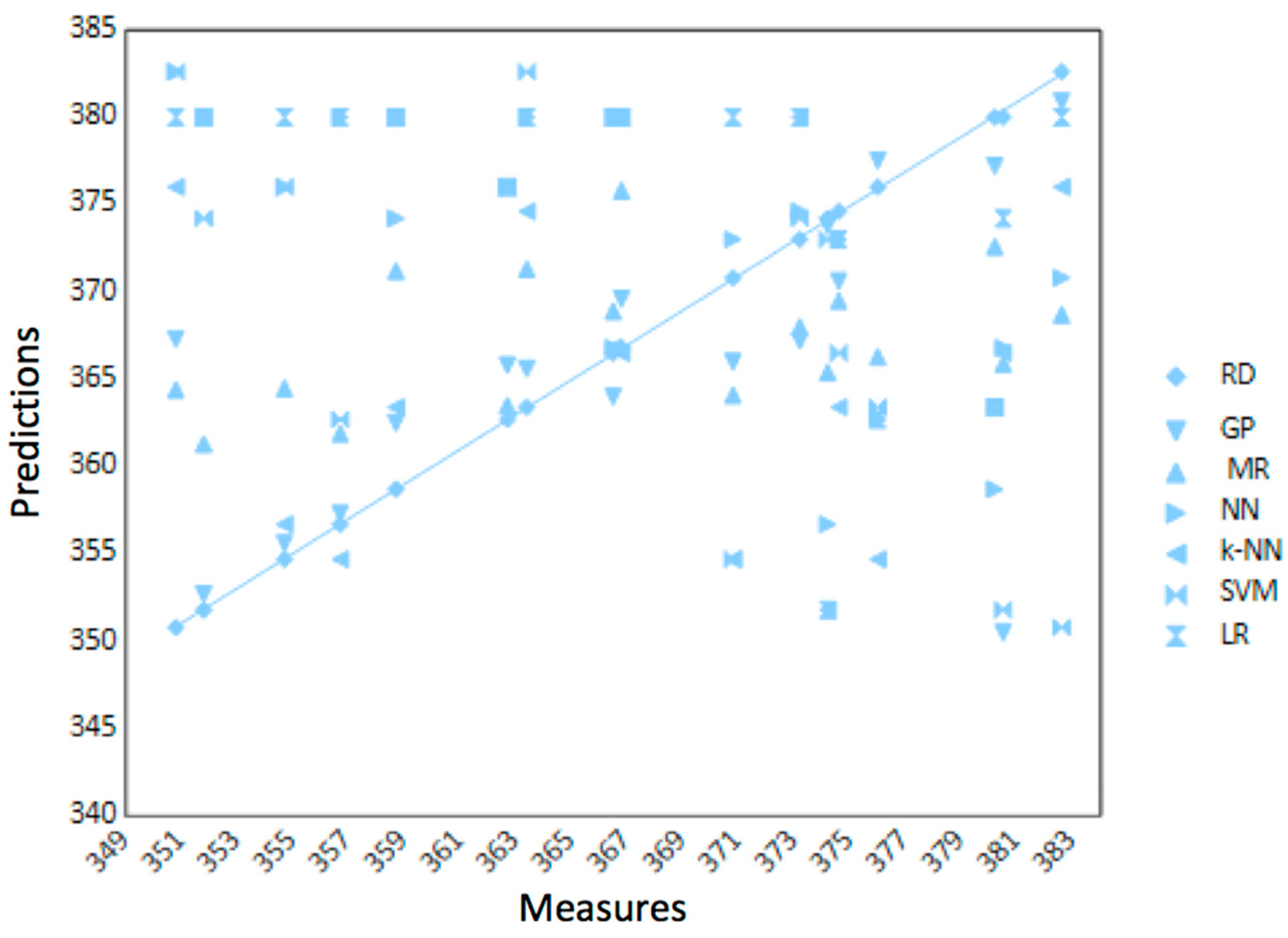

| Pearson coefficient | 0.5643 | 0.3883 | −0.7215 | −0.1587 | −0.6591 | −0.4889 | −0.0406 |

| Error (distances) | 1.30% | 2.20% | 3.90% | 3.20% | 4.40% | 4.20% | 3.00% |

| MSE | 70.737 | 78.800 | 273.908 | 202.963 | 329.272 | 290.238 | 184.532 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Babič, M.; Šturm, R.; Rucki, M.; Siemiątkowski, Z. Application of Machine Learning Method for Hardness Prediction of Metal Materials Fabricated by 3D Selective Laser Melting. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12832. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312832

Babič M, Šturm R, Rucki M, Siemiątkowski Z. Application of Machine Learning Method for Hardness Prediction of Metal Materials Fabricated by 3D Selective Laser Melting. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12832. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312832

Chicago/Turabian StyleBabič, Matej, Roman Šturm, Mirosław Rucki, and Zbigniew Siemiątkowski. 2025. "Application of Machine Learning Method for Hardness Prediction of Metal Materials Fabricated by 3D Selective Laser Melting" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12832. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312832

APA StyleBabič, M., Šturm, R., Rucki, M., & Siemiątkowski, Z. (2025). Application of Machine Learning Method for Hardness Prediction of Metal Materials Fabricated by 3D Selective Laser Melting. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12832. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312832