Terrain Surface Interpolation from Large-Scale 3D Point Cloud Data with Semantic Segmentation in Earthwork Sites

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Earthwork Volume Estimation Method

2.2. Terrain Surface Interpolation Method

3. Development of Terrain Surface Interpolation Method and Selection of Earthwork Volume Estimation Approach

3.1. Overview

3.2. Semantic Segmentation of Large-Scale 3D Point Cloud Data from Earthwork Sites

3.3. Development of Terrain Surface Interpolation Method

3.4. Selection of Earthwork Volume Estimation Method

4. Experimental Result and Discussion

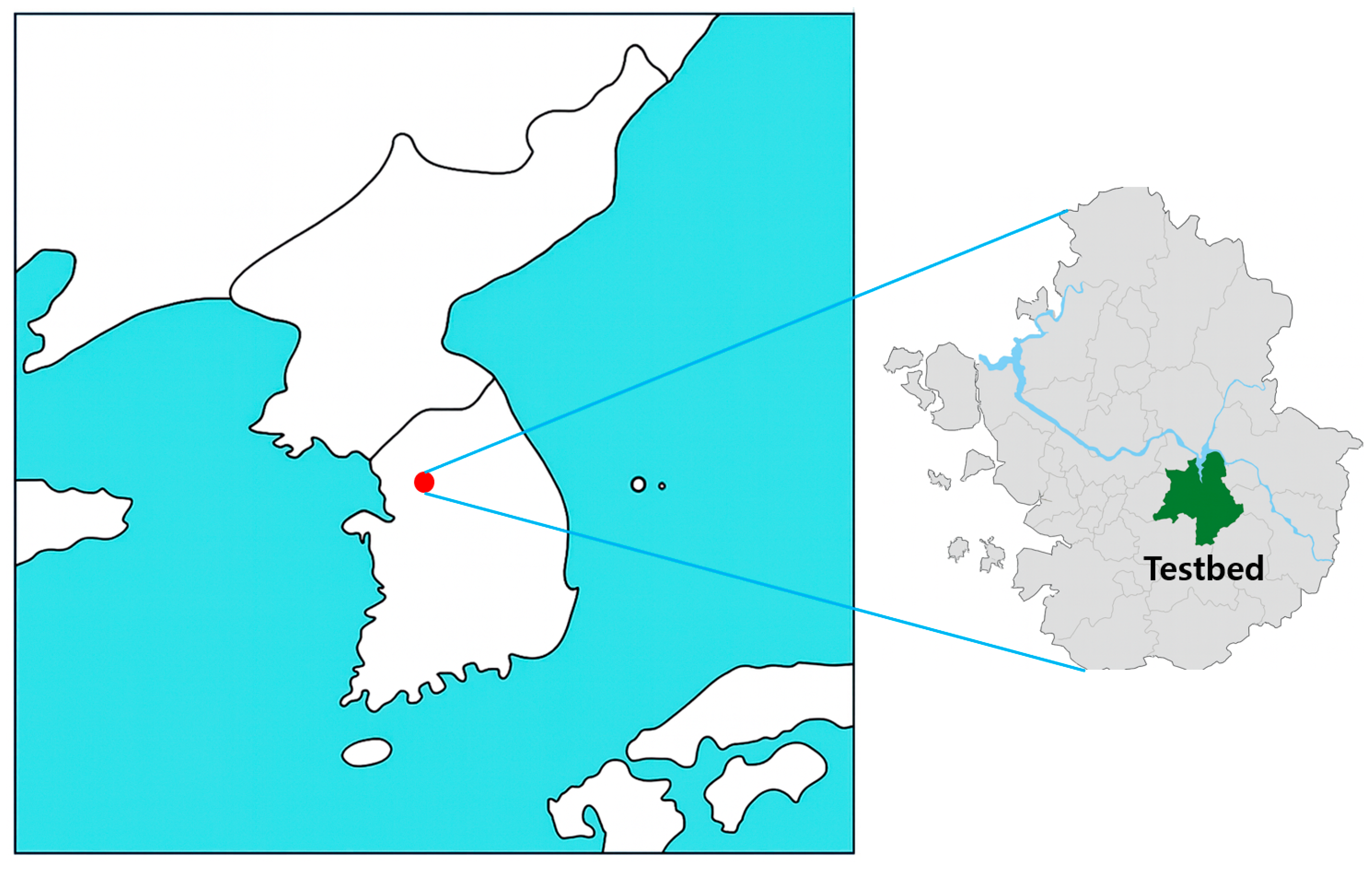

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.2. Generation of Predicted Data

4.3. Results of Terrain Surface Interpolation

4.4. Results of Terrain Change Analysis

4.5. Earthwork Volume Estimation Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, J.C.; Teng, H.C. 3D Laser Scanning and GPS Technology for Landslide Earthwork Volume Estimation. Autom. Constr. 2007, 16, 657–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lichti, D.D.; Gordon, S.J.; Stewart, M.P. Ground-Based Laser Scanners: Operation, System and Applications. Geomatica 2002, 56, 21–33. [Google Scholar]

- Prakash, A.; Verma, A.; Sharma, A.; Jaiswal, P.; Mandal, S.K. A Hybrid of GNSS Remote Sensing and Ground-Based Laser Technology for Geo-Referenced Surveying in Mining. Curr. Sci. 2024, 126, 336–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ersoz, A.B.; Pekcan, O. UAV-Based Automated Earthwork Progress Monitoring Using Deep Learning with Image Inpainting. Autom. Constr. 2025, 175, 106211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, H.; Sujaswara, A.A.; Kanemoto, T.; Tsubota, K. Possibilities of Using UAV for Estimating Earthwork Volumes during Process of Repairing a Small-Scale Forest Road, Case Study from Kyoto Prefecture, Japan. Forests 2023, 14, 677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chonpatathip, S.; Suanpaga, W.; Muttitanon, W. Earthwork Volume Measurement in Road Construction Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV). Int. J. Geoinform. 2023, 19, 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winiwarter, L.; Anders, K.; Wujanz, D.; Höfle, B. Influence of Ranging Uncertainty of Terrestrial Laser Scanning on Change Detection in Topographic 3D Point Clouds. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, 5, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastens, K.; Kaplan, D.; Christien-Blick, K. Development and Evaluation of High-Precision Earth-Work Calculating System Using Drone Survey. J. Geosci. Educ. 2001, 49, 249–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Han, D.; Song, M. Calculation and Comparison of Earthwork Volume Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Photogrammetry and Traditional Surveying Method. Sensors Mater. 2022, 34, 4737–4753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Park, S.; Choi, Y.; Kim, S. Performance Verification of Integrated Module for Automatic Analysis of Digital Maps in Earthwork Sites. J. Constr. Autom. Robot. 2023, 2, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Choi, S.; Kim, A. Scan Context++: Structural Place Recognition Robust to Rotation and Lateral Variations in Urban Environments. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2022, 38, 1856–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, A.; Ritchie, D.; Bokeloh, M.; Reed, S.; Sturm, J.; Niebner, M. ScanComplete: Large-Scale Scene Completion and Semantic Segmentation for 3D Scans. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 4578–4587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirzaei, K.; Arashpour, M.; Asadi, E.; Masoumi, H.; Bai, Y.; Behnood, A. 3D Point Cloud Data Processing with Machine Learning for Construction and Infrastructure Applications: A Comprehensive Review. Adv. Eng. Inform. 2022, 51, 101501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-G.; Park, S.-Y.; Kim, S. Development of Framework for Digital Map Time Series Analysis of Earthwork Sites. J. KIBIM 2023, 13, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Park, S.; Kim, S. GCP-Based Automated Fine Alignment Method for Improving the Accuracy of Coordinate Information on UAV Point Cloud Data. Sensors 2022, 22, 8735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bello, S.A.; Yu, S.; Wang, C.; Adam, J.M.; Li, J. Review: Deep Learning on 3D Point Clouds. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Wang, H.; Hu, Q.; Liu, H.; Liu, L.; Bennamoun, M. Deep Learning for 3D Point Clouds: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 43, 4338–4364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Park, J.; Ryu, Y.M. Semantic Segmentation of Bridge Components Based on Hierarchical Point Cloud Model. Autom. Constr. 2021, 130, 103847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharroubi, A.; Poux, F.; Ballouch, Z.; Hajji, R.; Billen, R. Three Dimensional Change Detection Using Point Clouds: A Review. Geomatics 2022, 2, 457–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lague, D.; Brodu, N.; Leroux, J. Accurate 3D Comparison of Complex Topography with Terrestrial Laser Scanner: Application to the Rangitikei Canyon (N-Z). ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2013, 82, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, C. Deep-Learning-Based Classification of Point Clouds for Bridge Inspection. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, S. 3D Point Cloud Dataset of Heavy Construction Equipment. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kim, S. Semantic Segmentation of Heavy Construction Equipment Based on Point Cloud Data. Buildings 2024, 14, 2393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Yang, B.; Xie, L.; Rosa, S.; Guo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Trigoni, N.; Markham, A. Randla-Net: Efficient Semantic Segmentation of Large-Scale Point Clouds. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 11105–11114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackel, T.; Savinov, N.; Ladicky, L.; Wegner, J.D.; Schindler, K.; Pollefeys, M. Semantic3d.net: A new large-scale point cloud classification. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1704.03847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, V.S.; Tran, M.H.; Nguyen, T.T. Filling Holes on the Surface of 3D Point Clouds Based on Tangent Plane of Hole Boundary Points. In Proceedings of the 7th Symposium on Information and Communication Technology, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam, 8–9 December 2016; pp. 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmitt, J.; Pillay, P.; Barrett, M.; Middleton, S.; Mackrell, T.; Floyd, B.; Ladefoged, T.N. A Comparison of Volumetric Reconstruction Methods of Archaeological Deposits Using Point-Cloud Data from Ahuahu, Aotearoa New Zealand. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štroner, M.; Křemen, T.; Braun, J.; Urban, R.; Blistan, P.; Kovanič, L. Comparison of 2.5d Volume Calculation Methods and Software Solutions Using Point Clouds Scanned before and after Mining. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2019, 24, 296–306. [Google Scholar]

- Idrees, A.; Heeto, F. Evaluation of Uav-Based Dem for Volume Calculation. J. Univ. Duhok 2020, 23, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leica Geosystems. Leica Cyclone 3DR. Available online: https://leica-geosystems.com/en-us/products/laser-scanners/software/leica-cyclone/leica-cyclone-3dr?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Trimble Inc. Trimble RealWorks. Available online: https://geospatial.trimble.com/en/products/software/trimble-realworks?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Girardeau-montaut, D. CloudCompare; EDF R&D Telecom ParisTech: Paris, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Skabek, K.; Kowalski, P. Building the Models of Cultural Heritage Objects Using Multiple 3D Scanners. Theor. Appl. Inform. 2009, 21, 115–129. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S.; Dong, Q.; Zhu, F.; Lv, Y.; Ye, P.; Wang, F.Y. SCF-Net: Learning Spatial Contextual Features for Large-Scale Point Cloud Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 14499–14508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolodiazhnyi, M.; Vorontsova, A.; Konushin, A.; Rukhovich, D. OneFormer3D: One Transformer for Unified Point Cloud Segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 18–22 June 2023; pp. 20943–20953. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Wang, C.; Yu, L.; Tian, S.; Ning, X.; Member, S.; Rodrigues, J. PointGT: A Method for Point-Cloud Classification and Segmentation Based on Local Geometric Transformation. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2024, 26, 8052–8062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Hu, Y.; Yang, X.; Dou, Z.; Kang, L. Robust Multi-Task Learning Network for Complex LiDAR Point Cloud Data Preprocessing. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 237, 121552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pix4D SA Pix4Dmapper. Available online: https://www.pix4d.com/product/pix4dmapper-photogrammetry-software/?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed on 4 October 2025).

- Qin, R.; Tian, J.; Reinartz, P. 3D Change Detection—Approaches and Applications. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2016, 122, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuse, T.; Yamano, T. Change Detection of Time-Series 3D Point Clouds Using Robust Principal Component Analysis. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci.—ISPRS Arch. 2021, 43, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data | Number of Points | Volume (m3) | Volume Difference to Day2 (m3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Day1 | 1,654,440 | 109,953 | (A) 1760 |

| Day1_HCE | 1,715,015 | 109,718 | (B) 1995 |

| Day1_IP | 1,715,015 | 109,940 | (C) 1773 |

| Day2 | 1,756,926 | 111,713 | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Park, S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S. Terrain Surface Interpolation from Large-Scale 3D Point Cloud Data with Semantic Segmentation in Earthwork Sites. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12831. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312831

Park S, Kim Y, Kim S. Terrain Surface Interpolation from Large-Scale 3D Point Cloud Data with Semantic Segmentation in Earthwork Sites. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12831. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312831

Chicago/Turabian StylePark, Suyeul, Yonggun Kim, and Seok Kim. 2025. "Terrain Surface Interpolation from Large-Scale 3D Point Cloud Data with Semantic Segmentation in Earthwork Sites" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12831. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312831

APA StylePark, S., Kim, Y., & Kim, S. (2025). Terrain Surface Interpolation from Large-Scale 3D Point Cloud Data with Semantic Segmentation in Earthwork Sites. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12831. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312831