1. Introduction

Modern machine tools are characterized by high precision, accuracy, and repeatability of production. This is due to many factors related to the machine’s proper design, construction, and assembly, its installation on properly prepared foundations, the production process it performs, and its control system. This control system currently plays an increasingly important role in the correct operation of the entire machine tool and significantly controls its accuracy. A properly developed control algorithm [

1,

2,

3] allows for wider use of modern machines equipped with various types of adaptive systems. This includes, for example, the widely used various types of sensors monitoring the machine’s operating status (measuring temperature, pressure, humidity, vibration amplitude, cutting force, etc.), as well as actuators, the use of which allows, for example, variable stiffness of supports holding the workpiece for processing [

4,

5] or variable stiffness of the bearing supports themselves [

6,

7]. These types of solutions allow the same machine to be used for various types of machining and to operate within a much wider range of spindle speeds. Variable bearing support stiffness allows for the high rigidity of the spindle system, necessary for high-performance machining, i.e., cutting large amounts of material at relatively low spindle speeds. By reducing the bearing preload, the same spindle can be used for HSC (high-speed cutting) machining—low feed rates at high speeds. For the spindle system to operate correctly with an active bearing support, it is necessary to use the appropriate control system for this support to utilize the machine spindle as efficiently as possible. One possible solution to this problem is described in detail later in this article.

Vibrations are an essential element of every machine tool’s operation. The role of machine designers is to design their structures to minimize these vibrations with the least possible effort. Among the many different types of vibration (self-excited, forced, resonant), the machine tool design should ensure that its spindle always operates outside its natural vibration range. This requires high bearing support stiffness, which is achieved with high bearing preload. This type of action causes increased resistance to the movement of the rolling elements between the bearing rings and simultaneously generates increased bearing operating temperatures, often necessitating intensive cooling. Analyzing the operation of modern machine tool spindles, it can also be noted that the maximum spindle stiffness is not utilized throughout the entire process performed by the machine tool, but only in short sections, such as during roughing. For this reason, a solution in which angular contact ball bearings operate with only a light preload, not necessarily continuously. When necessary, the tension is increased to perform one or more operations during a given production process. However, it should be remembered that the lower the bearing preload, the lower the natural frequency level and the risk of the spindle operating in the natural frequency region. These relationships were investigated using numerical modeling techniques and presented in this paper [

8].

The problem of low natural vibration frequencies in machine tool spindles can be observed, for example, in grinding spindles. This is primarily due to the geometric constraints of this design. A grinding wheel, a disc-shaped element with a relatively large mass relative to the spindle shaft, is typically mounted at the front end of the spindle. It is common knowledge that the greater the grinding wheel mass, the smaller the value of the first two natural vibration modes of the spindle system while maintaining a constant bearing preload. This theory is supported by the research conducted and presented in this paper [

9].

3. Application of the Control System

The proper operation of active systems is only possible through the use of appropriate control algorithms. Currently, we can distinguish P, PI, and PID controllers (proportional, proportional-derivative, and proportional-derivative-integral). A proportional P controller is one in which the output signal value is proportional to the control error. In this type of controller, the adjustable parameter is Kp, or gain. An integral I controller is one in which the rate of change of the output signal is proportional to the control error. The characteristic parameter of this controller is the integration time Ti, defined as the time after which the output signal, following a step change in the control error, reaches a value equal to the step value. By combining PI controllers, we obtain a proportional controller—in which the output signal is the sum of the proportional and integral effects. This allows us to have two adjustable parameters in a single controller, Kp and Ti. Adding a D term to the PI controller allows us to obtain a proportional-derivative-integral controller. The differential action of the controller means that the output signal value is proportional to the rate of change in the control error. The characteristic parameter of the controller is the derivative time Td. It determines the proportion to which the derivative action in the controller is taken into account and is called the lead time.

Properly selected controllers are designed to monitor the operating status of the control system and, if necessary, using various types of actuators to change its properties and adapt these properties to the machine’s temporary, often unusual, operating conditions. These unusual operating conditions include spindle speeds close to the system’s natural vibration frequency. This type of phenomenon can occur especially in solutions where we want to actively change the stiffness of a given spindle. Any change in stiffness affects the natural vibration frequency of the machine tool spindle. Therefore, it is important to know the range of these frequencies. Based on this, it is possible to determine areas in which the spindle should not operate. The use of an active bearing support allows the spindle’s stiffness to be adjusted during operation, allowing the spindle to be used across a full range of rotational speeds and a very wide range of preloads. If, based on continuous vibration measurements, for example, at the spindle tip, an increase in vibration amplitude is observed, the spindle stiffness can be temporarily adjusted to prevent the system from operating within its natural vibration range. This type of solution, using a block diagram, is shown in

Figure 1.

Based on this block diagram, a system for actively changing the bearing preload is presented. This system is designed to control and, if necessary, correct the bearing preload in an example machine tool spindle. A detailed description of this solution is presented in previous publications [

8,

14]. In this article, the main focus is on the control system, without which active change of the preload would not be possible. A new concept for the active support control system was proposed. The initial control system was based on a step change in the bearing preload value when a specific vibration amplitude was exceeded. This article describes a modification of this approach to the bearing preload control method. A PID controller was used for control, with setpoint values for each of its components determined experimentally. A modification of the control application was proposed to enable control of the PID controller. New (different from previous studies) touch sensors mounted directly in the active support were also used. These sensors were characterized by higher resolution and measurement accuracy, which could also positively impact the operation of the entire control system.

4. Construction of the Test Stand

To conduct the tests, a proprietary test stand was designed and constructed, along with a model spindle system. The test stand configuration used at this stage of the research was based on a spindle supported by two bearing supports with a spacing of 204 mm, each equipped with B7206-CT-PS4-UM angular contact ball bearings from FAG [

15]. These bearings were arranged in an “O” configuration, one of which was actively tensioned using three PSt 150/10/40 VS15 piezoelectric actuators from Piezomechanik [

16]. According to the well-known relationship in an “O” bearing arrangement, tensioning only one bearing ensures the introduction of stiffness for the entire spindle system [

17]. For the bearings used, their nominal operating angle is 30 degrees, ensuring proper spindle stiffness in both the radial and axial directions. In the tests, a force of 200 N was used as the initial value, corresponding to the average preload at which the bearings operate at their nominal angle. This approach was dictated by the desire to vary the preload across its full range, so that the control system could both increase and decrease it. To ensure proper operation of the active system, each piezo actuator was placed symmetrically every 120 degrees relative to the spindle axis. Individual positioning was also ensured, and its correct positioning was adjusted using adjustment screws that allowed for precise setting of the bearing preload value [

9]. The use of piezo actuators as active elements was dictated by their properties, including high stiffness, short response time to the control signal, and relatively small size, which allows for their installation in non-standard applications. Three Keyence GT2-P12K displacement sensors were also located in the active support, enabling continuous monitoring of the relative displacement of the bearing raceways. The arrangement of piezo actuators and displacement sensors in the active support is shown in

Figure 2.

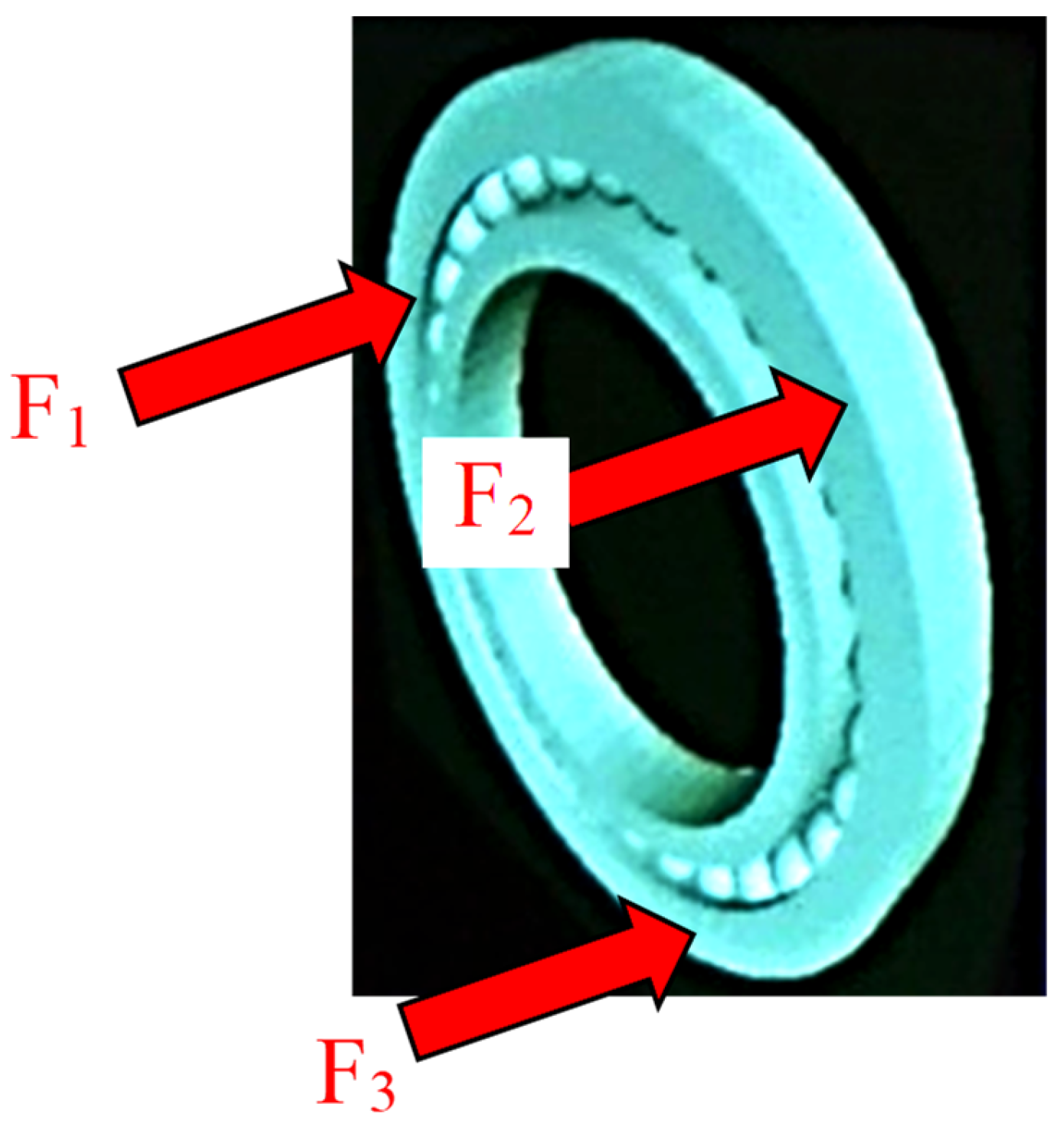

Each piezo actuator had a strain gauge system that allowed for real-time monitoring of the pressure applied to the outer bearing race. This reduced the likelihood of the bearing races skewing during the active support’s operation. This behavior is schematically shown in

Figure 3. In extreme cases, it could lead to the bearing jamming inside the bearing support, preventing the spindle assembly from functioning properly.

The model spindle was driven by an external high-speed motor connected to the spindle via a clutch. The concentricity of the coupled components was ensured after an alignment procedure using an EasyLaser E710 measuring device (Easy-Laser, Chesterfield, UK). The FAG 7206C angular contact ball bearings (Schaeffler Group, Herzogenaurach, Germany) used in the tests can operate under various preload conditions. Their characteristics are shown in

Figure 4. This shows the relationship between the bearing preload and the relative displacement of the bearing raceways. When determining this characteristic, the initial value was assumed to be the point beyond which the relative displacement of the bearing raceway causes an increase in the preload force measured using strain gauges in the piezo actuators.

Using this curve in the control system allows for monitoring the operating status of the active support. The presented system uses low-voltage piezo actuators operating in the −30 V–+150 V range. The initial control voltage is +30 V. This allows for both increasing and decreasing the initial preload value, initially set to 200 N. Each actuator has a strain gauge system that allows for direct reading of the preload force. Unfortunately, this value is only displayed on the amplifier and can be used to set the initial value. It is not directly input into the control system. Therefore, it is necessary to use the curve shown in

Figure 4 and the signal from the displacement sensors. By using displacement sensors, we can indirectly determine the preload force value of the bearings during their operation. This also allows for the introduction of a limit that protects the bearings from operating with excessive preload.

5. Description of the Control System and Its Operating Parameters

The simultaneous use of both a strain gauge system equipped with piezo actuators and displacement sensors was used to develop a system controlling the preload of the active support. The main goal of this solution was to reduce the vibration amplitude of the front spindle end. Based on numerical modeling studies, the first two natural frequencies of the spindle system were known. The first natural frequency was 278 Hz, and the second natural frequency was 979 Hz. These values were obtained for a test bench configuration with the following parameters: support spacing of 204 mm, average bearing preload of 200 N, and the use of a 3 kg equivalent mass. Each change in the preload value caused a change in the system’s natural frequency. Considering the entire range of bearing preloads, from light to heavy, the frequency range for the first frequency varied from 182 to 333 Hz and for the second frequency from 946 to 1031 Hz.

The sensitivity of the spindle system to changes in preload allowed the development of an active support control system that actively reduced the maximum amplitude values for the natural frequencies of the tested spindle. The control system’s operating principle is based on continuous monitoring of the behavior of the front spindle nose and the preload values of the bearings. Vibration amplitudes were measured directly using a non-contact displacement sensor (designed by IPPT PAN Warsaw) [

18] placed as shown in

Figure 5.

The preload was determined indirectly based on the bearing characteristics shown in

Figure 4 and the actual measurement of the relative displacement of the bearing raceways. The control system was designed to maintain the minimum preload on the bearings, ensuring stable spindle operation while simultaneously reducing the vibration amplitude of the front end in real-time. This approach was dictated by the desire to reduce bearing wear, reduce their operating temperature, and eliminate slippage in their rolling elements. Based on the literature [

11,

12,

19] it is known that the simplest solution for reducing spindle vibration is to increase its stiffness sufficiently to prevent it from operating in the system’s resonant frequency range. In the case of grinding spindles, which do not require high stiffness due to the low forces involved in the grinding process, deliberately operating the spindle with a high preload on the bearings may not be optimal.

The test stand shown in

Figure 5 was used to confirm the accuracy of the model results. To approximate the model spindle to a grinding spindle, a substitute mass simulating a grinding wheel was placed at its front end. This mass was mounted on the spindle shaft via an additional ball bearing. Based on preliminary tests, the first two resonant frequencies of the system were determined, which for a 3 kg substitute mass were 196 and 989 Hz, respectively. These values were used to determine the frequency range within which external excitation was introduced. This excitation was implemented using a GW-V20 exciter from Data Physics Corporation (Riverside, CA, USA), connected to the substitute mass in a direction perpendicular to the spindle axis. The excitation was implemented using a random-frequency, increasing signal with a random amplitude. This solution was intended to simulate the pseudo-random behavior of the spindle system during operation. The control system for the active support was responsible for correcting the bearing preload to minimize vibrations at the front spindle end while maintaining minimal bearing preload. The complete diagram of the control system for the spindle with active support is shown in

Figure 6. The blue lines represent control signals coming from MyRio. Control is implemented for the spindle speed, the piezo actuator extension, and the vibrations generated by the exciter. The red lines represent feedback signals, which measure the relative displacement of the bearing raceways. The signal value from the strain gauges installed inside the piezo actuators can also be considered feedback, but in the presented solution, it is not directly used by the control application.

The most important element of the control system is the controller. Based on numerous tests and research experiments, a PID controller was used, and its control parameters were selected based on the so-called Ziegler-Nichols second method, i.e., a closed-loop operation method. This selection involved the proper determination of three parameters k

p, T

i, and T

d, which are understood as controller settings, i.e., parameters individually adjustable for each controller. The entire control system was developed using the MyRio platform and LabVIEW software. Following the principles of LabVIEW programming, the control application was developed in Block Diagram and utilized pre-built software blocks, such as PID, While control loops with a Wait function defining the control loop execution time, controls allowing for external data entry, and a Waveform Graph for displaying time histories, e.g., from displacement sensors. Due to the complex nature of the entire control system, the application was divided into separate sections that perform tasks in parallel. This enabled reading data from displacement sensors (measuring module) with the ability to set the signal sampling rate to 0.1 s by default. The spindle speed setting module allowed speed control from level VI, which, based on mathematical functions, transmitted control values to the drive motor inverter. A separate PID controller was also implemented, utilizing the second Ziegler–Nichols method, allowing for specific settings to be entered for individual controller elements. According to this method, the settings should be, depending on the type of controller [

20]:

For the regulator P: kp = 0.5 kkr,

For the regulator PI: kp = 0.45 kkr, Ti =

For the regulator PID: kp = 0.6p kkr, Ti = 0.5 Tosc, Td = ; where

Kp—amplification factor,

Kkr—critical amplification factor at which oscillations occur,

Ti—integration time constant,

Tosc—time constant of undamped oscillations,

Td—differentiation time constant.

The use of a PID logic block within LabVIEW allowed for the setting of specific values for kp, Ti, and Td, which the author of the paper described as P, I, and D for the controller. This nomenclature was intended to clearly indicate the type of controller used during the research. Entering a zero value, for example, at position D, automatically generated a PI controller. According to the Ziegler–Nichols method, correct controller operation relies on the correct determination of the Kkr and Tosc values. To determine these Kkr and Tosc values, the system must be brought into undamped oscillation and the oscillation time constant (Tosc) must be measured. The control system is then activated and the Kkr value at which these oscillations occur is measured. In the presented solution, these values were obtained from simulation and are equal to Kkr = 4.25 and Tosc = 1.46, respectively. Knowing these values, a control algorithm can be proposed in which, instead of specifying the values of the individual controller terms (P, I, D), we specify the Kkr and Tosc values. However, for programming reasons, a solution was chosen in which the values of individual regulators are provided directly.

Based on the relationships presented above, the controller setting values were as follows: P = 2.55, I = 0.72, D = 0.03. To check whether any radical errors were made during the selection procedure, the automatic tuning method and determination of controller settings, available from the MyRio platform, were also used. A detailed description of this method is included in the study [

21]. In both cases, the setting values were similar and are shown in

Table 1.

For these controller settings, vibration amplitude reduction measurements were performed on the front spindle end. Manually selected settings were used first, followed by those obtained during the self-tuning stage. The measurements were performed while the spindle was running at 1000 rpm and using a random active excitation from the exciter. The signal sampling frequency was set to 1000 Hz. The system operated in a 500 ms feedback loop. Measured values from the displacement sensors were not filtered, but only averaged every 100 samples. An average value was determined from every 100 measured values and saved to a table in the control application. The measurements were performed for three different equivalent masses: 1.5 kg, 2.25 kg, and 3 kg. For each mass, the measurement was repeated five times. The results for manual tuning performed directly in this publication and automatic tuning based on research [

9] were compared and presented in

Table 2.

The results from

Table 2 are visualized in a bar graph (

Figure 7). The values in the table and graph should be understood as the average value of five measurements. Additionally, the dispersion of the measurements was also determined, graphically indicated by a red line for each measurement section. The graph assumes that for the system without control, the displacement amplitude of the front spindle nose, determined as the average of five measurements, is 100%. In the system using the automatic tuning control system (for a 3 kg equivalent mass), the average displacement amplitude decreased by approximately 19.49%, which is 80.21% of the vibration amplitude without control. For the system with manual tuning, we obtained an amplitude reduction of approximately 16.74% compared to the system without control, which was 73.26% of the initial value without control. The remaining percentage values of the front spindle nose displacement amplitudes were determined in the same manner for the 2.25 kg and 1.5 kg equivalent masses.