The Present and Future of Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Exercise Interventions: A Narrative Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

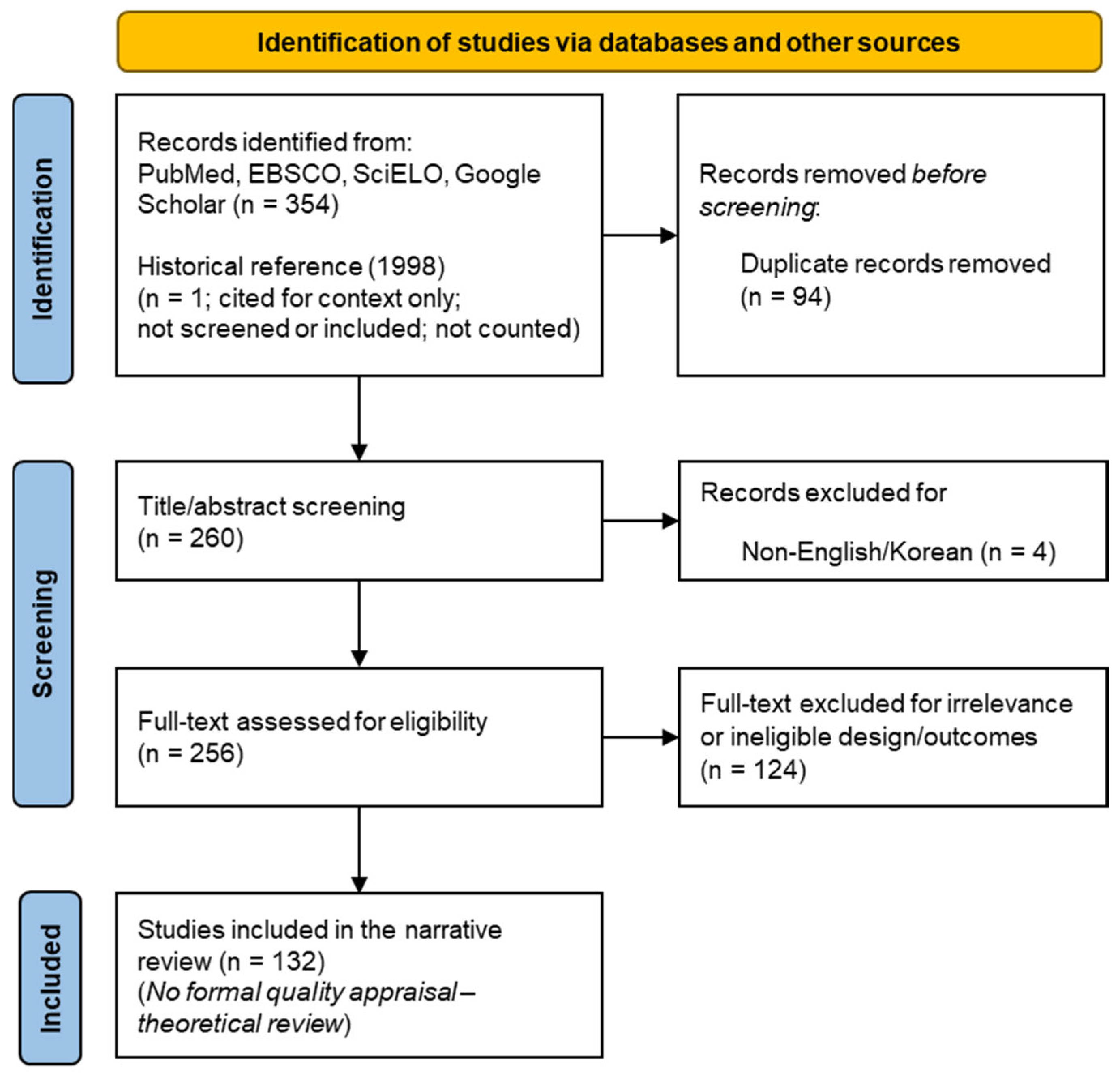

2. Methods

3. Results

3.1. Definition of Sarcopenia

3.2. Etiology

3.3. Clinical Implications

3.4. Clinical Assessment and Diagnostic Tools

3.4.1. Screening Tools

- Sarcopenia-five-item questionnaire (SARC-F) is a self-report questionnaire for the rapid screening and includes five items: muscle strength, assistance with walking, getting out of a chair, climbing stairs, and falling experience. Each item is scored on a 0–2 scale (total score = 10), with a score of 4 or higher indicating the need for further evaluation. SARC-F is quick, inexpensive, and useful for large-scale screening. However, the limitations include self-report-related subjectivity, low sensitivity, and the lack of direct assessment of muscle mass, which lead to underdiagnosis of the mild cases [39].

- SARC-F questionnaire and calf circumference (SARC-CalF), developed by Barbosa-Silva et al. [40] in Brazil, aims to compensate for the low sensitivity of the SARC-F by adding calf circumference (CC). For CC of <34 cm for men and <33 cm for women, the SARC-F total score is added to the CC score (0–10 to produce a total score, and a score of ≥11 generally indicates a high risk for sarcopenia). However, CC is subject to errors due to edema, measurement location, etc., and needs to be standardized [40].

3.4.2. Assessing Strength

- GS is highly correlated with upper extremity strength as well as with total body strength and muscle mass, meaning that weakness in the hand is likely to be accompanied by weakness in the muscles of the entire body [41].

- The FTSST is a simple and reliable method to assess lower body strength, mobility, and physical decline. The test is quick and easy to perform without any equipment and is widely used as a strength assessment tool in clinical and community settings [4].

- KE strength is a representative quantitative indicator of quadriceps strength in the lower limbs. KE strength is closely associated with lower limb weakness, functional limitations, and diagnosis of sarcopenia, making it a core metric in functional assessment [4].

3.4.3. Assessing Muscle Mass

- DXA uses radiation to simultaneously and accurately measure total body and site-specific muscle mass, body fat, and bone density. The technique is the gold standard in clinical research [42]. However, cost, accessibility, and radiation exposure are drawbacks, and alternative methods are being developed [43].

- Bioelectric impedance analysis (BIA) is a non-invasive method for estimating muscle mass using differences in the electrical properties of tissues, such as water, fat, and muscle in the body. It is widely used in clinical and large epidemiological studies owing to its simplicity, short test time, lack of radiation exposure, and low cost. However, the results can vary depending on the body hydration status, food intake, device type, and measurement environment. Furthermore, standardized conditions for conducting BIA are required and care must be taken when interpreting the results [44,45].

- Medical imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and computed tomography (CT), is the most precise imaging method for evaluating muscle quality, including muscle mass and intramuscular fat deposition (myosteatosis). It is used as a reference for research and precision diagnosis because it can quantify muscle volume and cross-sectional area through cross-sectional images and the degree of fat deposition (CT radiation attenuation, MRI fat fraction, etc.). However, cost and access challenges relating to MRI and the radiation exposure limitations of CT, these medical imaging technologies are mainly used for research and advanced clinical evaluation, and not for routine screening [4,46].

- Musculoskeletal ultrasound is a noninvasive method for assessing muscle thickness, cross-sectional area, and structure in real time. It has been increasingly used in clinical and research studies due to its low cost and lack of radiation exposure. The limitations include large differences in measurement results depending on the examiner’s skill level, and the need for standardization of the method [4,47].

3.4.4. Assessing Physical Function

- Timed up and go (TUG) measures the time taken to get up from a seated position, walk a certain distance, and then sit down again. It can simultaneously assess mobility and balance, making it useful for screening for fall risk among older adults and measuring the effectiveness of rehabilitation [4,50].

- The 6-Minute walk test (6MWT) assesses endurance and functional exercise capacity by measuring the maximum distance traveled in a limited amount of time (6 min). It is used as a surrogate marker of total body endurance, cardiorespiratory capacity, and the ability to perform ADL [50].

- The 400 m walk test assesses the ability to complete a certain distance (400 m) and reflects long-distance walking ability and endurance. It has been reported as a marker strongly associated with long-term health outcomes in older adults in large cohort studies [51].

3.4.5. Sarcopenia Assessment Tool for Psychological Factors

- The Geriatric Depression Scale and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale are widely used for assessing psychological factors in older adults. Studies have repeatedly reported that sarcopenia and depressive symptoms are independent but mutually reinforcing risk factors [53].

- Quality of Life Assessment The Sarcopenia and Quality of Life (SarQoL) Questionnaire is a tool developed specifically for patients with sarcopenia that quantifies multidimensional QoL, including physical functioning, mental health, and social engagement. This reflects the clinical impact of the disease from a patient-centered perspective [54].

- The Mini-Mental State Examination and Montreal Cognitive Assessment, among others, have been used to assess cognitive decline and an increased risk of dementia [55].

3.5. Diagnostic Criteria

3.6. Exercise Rehabilitation

3.6.1. Ideal Sarcopenia Rehabilitation

- Resistance exercise (RE)

- Combined exercise

3.6.2. Stepwise Systematic Approach

- Guidelines based on sarcopenia severity [12]

- Specific prescription guidelines for RE [76]

- Iatrogenic sarcopenia and a step-by-step nutrition and exercise integration approach [75]

- Probable sarcopenia and early intervention strategies [77]

3.6.3. Multimodal Sarcopenia Rehabilitation Program

- Adaptations of Traditional RE

- Aerobic and rhythmic exercise

- Blood flow restriction training

- Integrative mind–body exercise

- Innovative and technology-enabled interventions

| Category | Representative Types | Key Effects | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adaptations of Traditional RE [69,70,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88] | Sling, TRX, elastic bands, squats & power training, Swiss ball, plyometrics | ↑ Strength/power, ↑ hypertrophy; ↑ balance & proprioception, ↑ core stability, some ↑ bone density, mixed aerobic-resistance options | Diverse, cost-effective tools, adaptable to setting, low-load options for older adults, multidimensional functional gains | Device/setup variability → standardization needed, high-velocity/power & plyometrics may raise fall/joint load → gradual progression/supervision, adjust dose during pain/inflammation flares [111] |

| Aerobic and Rhythmic Exercise [91,92,93,94,95] | Dance sports, traditional rhythmic dance (e.g., Javanese), group rhythm-based AE | ↑ Cardiorespiratory fitness, ↑ gait speed, ↑ functional mobility/balance, addresses fall-risk factors, social bonding | Enjoyment & interaction → adherence ↑, complements fall-prevention components | Modest gains in strength/lean mass when used alone; monitoring/supervision for dizziness/balance or cardiovascular risk |

| Blood Flow Restriction Training [96,97] | LLBFR (20–30% 1RM, 40–80% LOP, 30-15-15-15) | ↑ Strength & function, favorable signals on some metabolic/cardiovascular markers, ↓ joint load | Low joint strain, bridge to capacity building in early rehab, effective short sessions | Screen for contraindications (thrombosis, PVD, uncontrolled hypertension, etc.); high-intensity RE may better maximize hypertrophy—select by goal |

| Integrative Mind–Body Exercise [98,99,100,101,102,103] | Yoga, Pilates, Tai Chi | Autonomic stabilization & stress reduction, ↑ balance/postural control, ↑ core activation | Mind–body benefits, QoL gains, reinforces fall-prevention components | Low external load → limited standalone gains in strength/power → combine with RE, faulty technique may cause pain/minor injuries → instruction/correction needed [71,112] |

| Innovative & Technology-Enabled [104,105,106,107,108] | WB-EMS, WBV, VR/AR exercise, AI telerehabilitation (3D pose estimation) | ↑ Lower-limb strength, ↑ mobility, ↑ balance, better functional scores (TUG/SPPB), and possible QoL gains → use as low-intensity, supervised adjuncts to RE | Low-load, time-efficient (WB-EMS), suitable for very old adults (WBV), immersive/task-oriented engagement (VR), feedback-rich remote delivery (AI) | Manage device-specific contraindications (WB-EMS with implanted devices, WBV in epilepsy/PVD/neuropathy/diabetic complications, VR for cybersickness/falls). Practical barriers: digital literacy, device/network access, data privacy/security [113,114,115,116,117] |

3.7. Nutrition and Education

3.7.1. Nutritional Therapy

3.7.2. Educational Programs

4. Discussion

4.1. Key Findings and Clinical Implications

4.2. Future Directions

- Dose–response relationships for resistance, aerobic, balance, and multimodal training in diverse older adults [141].

- Integrated intervention models, such as combined exercise–nutrition–education packages, evaluated on hard clinical outcomes (e.g., falls, fractures, hospitalization, mortality) [142].

- Rigorous evaluation of technology-enabled interventions (WB-EMS, WBV, VR, AI-assisted telerehabilitation), including safety, feasibility, digital access, and privacy [110].

- Real-world implementation and scale-up, including cost-effectiveness, resource requirements, and long-term adherence strategies [143].

- Development of digital or sensor-based biomarkers for monitoring muscle quality, gait dynamics, and exercise response [144].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division. World Population Ageing 2023: Challenges and Opportunities of Population Ageing in the Least Developed Countries; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Ageing and Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Chowdhury, S.R.; Chandra Das, D.; Sunna, T.C.; Beyene, J.; Hossain, A. Global and regional prevalence of multimorbidity in the adult population in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. eClinicalMedicine 2023, 57, 101860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruz-Jentoft, A.J.; Bahat, G.; Bauer, J.; Boirie, Y.; Bruyère, O.; Cederholm, T.; Cooper, C.; Landi, F.; Rolland, Y.; Sayer, A.A.; et al. Sarcopenia: Revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing 2019, 48, 16–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirk, B.; Cawthon, P.M.; Arai, H.; Ávila-Funes, J.A.; Barazzoni, R.; Bhasin, S.; Binder, E.F.; Bruyere, O.; Cederholm, T.; Chen, L.-K.; et al. The Conceptual Definition of Sarcopenia: Delphi Consensus from the Global Leadership Initiative in Sarcopenia (GLIS). Age Ageing 2024, 53, afae052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. ICD-10-CM Code M62.84—Sarcopenia. Available online: https://www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/Codes/M00-M99/M60-M63/M62-/M62.84 (accessed on 29 July 2025).

- Petermann-Rocha, F.; Balntzi, V.; Gray, S.R.; Lara, J.; Ho, F.K.; Pell, J.P.; Celis-Morales, C. Global prevalence of sarcopenia and severe sarcopenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2022, 13, 86–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cegielski, J.; Bass, J.J.; Willott, R.; Gordon, A.L.; Wilkinson, D.J.; Smith, K.; Atherton, P.J.; Phillips, B.E. Exploring the variability of sarcopenia prevalence in a research population using different disease definitions. Aging Clin. Exp. Res. 2023, 35, 2271–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Puyo, J.; Izagirre-Fernandez, O.; Crende, O.; Valdivia, A.; García-Gallastegui, P.; Sanz, B. Experimental models as a tool for research on sarcopenia: A narrative review. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 101, 102534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, J.; Xi, H.; Cheng, Y.; Han, B. Global research trends in sarcopenia: A bibliometric analysis of exercise and nutrition (2005–2025). Front. Nutr. 2025, 12, 1579572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, Y.; Wakabayashi, H.; Yamada, M.; Kim, H.; Harada, A.; Arai, H. Interventions for Treating Sarcopenia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Studies. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2017, 18, 553.e1–553.e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, A.; Tomaino, F.; Paoletta, M.; Liguori, S.; Migliaccio, S.; Rondanelli, M.; Di Iorio, A.; Pellegrino, R.; Donnarumma, D.; Di Nunzio, D.; et al. Physical exercise for primary sarcopenia: An expert opinion. Front. Rehabil. Sci. 2025, 6, 1538336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsson, L.; Degens, H.; Li, M.; Salviati, L.; Lee, Y.I.; Thompson, W.; Kirkland, J.L.; Sandri, M. Sarcopenia: Aging-Related Loss of Muscle Mass and Function. Physiol. Rev. 2019, 99, 427–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, R.N.; Koehler, K.M.; Gallagher, D.; Romero, L.; Heymsfield, S.B.; Ross, R.R.; Garry, P.J.; Lindeman, R.D. Epidemiology of sarcopenia among the elderly in New Mexico. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1998, 147, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Invernizzi, M.; Baricich, A.; Cisari, C. Sarcopenia and Aging. In Rehabilitation Medicine for Elderly Patients; Masiero, S., Carraro, U., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.-K.; Woo, J.; Assantachai, P.; Auyeung, T.-W.; Chou, M.-Y.; Iijima, K.; Jang, H.C.; Kang, L.; Kim, M.; Kim, S.; et al. Asian Working Group for Sarcopenia: 2019 Consensus Update on Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Treatment. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2020, 21, 300–307.e302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Huang, Y.; An, R.; Yang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wan, Q. Risk factors for sarcopenia in community setting across the life course: A systematic review and a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch. Gerontol. Geriatr. 2025, 133, 105807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzetti, E.; Calvani, R.; Coelho-Júnior, H.J.; Landi, F.; Picca, A. Mitochondrial quantity and quality in age-related sarcopenia. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarto, F.; Franchi, M.; McPhee, J.S.; Stashuk, D.; Paganini, M.; Monti, E.; Rossi, M.; Sirago, G.; Zampieri, S.; Motanova, E. Motor unit loss and neuromuscular junction degeneration precede clinically diagnosed sarcopenia. Physiology 2024, 39, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shur, N.; Simpson, L.; Crossland, H.; Constantin, D.; Cordon, S.; Constantin-Teodosiu, D.; Stephens, F.; Brook, M.; Atherton, P.; Smith, K.; et al. Bed-rest and exercise remobilisation: Concurrent adaptations in muscle glucose and protein metabolism. Physiology 2024, 39, 545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hämäläinen, O.; Tirkkonen, A.; Savikangas, T.; Alén, M.; Sipilä, S.; Hautala, A. Low physical activity is a risk factor for sarcopenia: A cross-sectional analysis of two exercise trials on community-dwelling older adults. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cereda, E.; Pisati, R.; Rondanelli, M.; Caccialanza, R. Whey protein, leucine-and vitamin-D-enriched oral nutritional supplementation for the treatment of sarcopenia. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romani, M.; Berger, M.M.; D’Amelio, P. From the Bench to the Bedside: Branched Amino Acid and Micronutrient Strategies to Improve Mitochondrial Dysfunction Leading to Sarcopenia. Nutrients 2022, 14, 483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calcaterra, L.; van Kan, G.A.; Steinmeyer, Z.; Angioni, D.; Proietti, M.; Sourdet, S. Sarcopenia and poor nutritional status in older adults. Clin. Nutr. 2024, 43, 701–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yue, J. Precision intervention for sarcopenia. Precis. Clin. Med. 2022, 5, pbac013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shigehara, K.; Kato, Y.; Izumi, K.; Mizokami, A. Relationship between testosterone and sarcopenia in older-adult men: A narrative review. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ibad, H.A.; Mammen, J.S.; Simonsick, E.M.; Kwoh, C.K.; Guermazi, A.; Demehri, S. Higher thyroid hormone has a negative association with lower limb lean body mass in euthyroid older adults: Analysis from the Baltimore Longitudinal study of aging. Front. Aging 2023, 4, 1150645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torii, M.; Hashimoto, M.; Hanai, A.; Fujii, T.; Furu, M.; Ito, H.; Uozumi, R.; Hamaguchi, M.; Terao, C.; Yamamoto, W.; et al. Prevalence and factors associated with sarcopenia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod. Rheumatol. 2019, 29, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakinowska, E.; Olejnik-Wojciechowska, J.; Kiełbowski, K.; Skoryk, A.; Pawlik, A. Pathogenesis of Sarcopenia in Chronic Kidney Disease-The Role of Inflammation, Metabolic Dysregulation, Gut Dysbiosis, and microRNA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wan, C.S.; Ktoris, K.; Reijnierse, E.M.; Maier, A.B. Sarcopenia is associated with mortality in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gerontology 2022, 68, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.X.M.; Yao, J.; Zirek, Y.; Reijnierse, E.M.; Maier, A.B. Muscle mass, strength, and physical performance predicting activities of daily living: A meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2020, 11, 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hetherington-Rauth, M.; Magalhães, J.P.; Alcazar, J.; Rosa, G.B.; Correia, I.R.; Ara, I.; Sardinha, L.B. Relative Sit-to-Stand Muscle Power Predicts an Older Adult’s Physical Independence at Age of 90 Yrs Beyond That of Relative Handgrip Strength, Physical Activity, and Sedentary Time: A Cross-sectional Analysis. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2022, 101, 995–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Yang, R.; Xu, J.; Fang, K.; Abdelrahim, M.; Chang, L. Sarcopenia as a predictor of postoperative risk of complications, mortality and length of stay following gastrointestinal oncological surgery. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2021, 103, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severinsen, M.C.K.; Pedersen, B.K. Muscle-Organ Crosstalk: The Emerging Roles of Myokines. Endocr. Rev. 2020, 41, 594–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, D.; Yoon, G.; Kim, O.Y.; Song, J. A new paradigm in sarcopenia: Cognitive impairment caused by imbalanced myokine secretion and vascular dysfunction. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2022, 147, 112636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.-K. Sarcopenia in the era of precision health: Toward personalized interventions for healthy longevity. J. Chin. Med. Assoc. 2024, 87, 980–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merz, K.E.; Thurmond, D.C. Role of Skeletal Muscle in Insulin Resistance and Glucose Uptake. Compr. Physiol. 2020, 10, 785–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Therkelsen, K.E.; Pedley, A.; Speliotes, E.K.; Massaro, J.M.; Murabito, J.; Hoffmann, U.; Fox, C.S. Intramuscular fat and associations with metabolic risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2013, 33, 863–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, J.; Leung, J.; Morley, J.E. Validating the SARC-F: A suitable community screening tool for sarcopenia? J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2014, 15, 630–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbosa-Silva, T.G.; Menezes, A.M.; Bielemann, R.M.; Malmstrom, T.K.; Gonzalez, M.C. Enhancing SARC-F: Improving Sarcopenia Screening in the Clinical Practice. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2016, 17, 1136–1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohannon, R.W. Grip strength: An indispensable biomarker for older adults. Clin. Interv. Aging 2019, 14, 1681–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, D.; Tanner, S.B.; Szalat, A.; Malabanan, A.; Prout, T.; Lau, A.; Rosen, H.N.; Shuhart, C. DXA reporting updates: 2023 official positions of the International Society for Clinical Densitometry. J. Clin. Densitom. 2024, 27, 101437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, S.W.; Liew, J.; Dharmaratnam, V.M.; Yik, V.Y.J.; Kok, S.; Aftab, S.; Tong, C.; Lee, H.B.; Mah, S.; Yan, C.; et al. Diagnostic performance of various radiological modalities in the detection of sarcopenia within Asian populations: A systematic review. Ann. Coloproctol. 2025, 41, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kyle, U.G.; Bosaeus, I.; De Lorenzo, A.D.; Deurenberg, P.; Elia, M.; Manuel Gómez, J.; Lilienthal Heitmann, B.; Kent-Smith, L.; Melchior, J.C.; Pirlich, M.; et al. Bioelectrical impedance analysis-part II: Utilization in clinical practice. Clin. Nutr. 2004, 23, 1430–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gade, J.; Astrup, A.; Vinther, A.; Zerahn, B. Comparison of a dual-frequency bio-impedance analyser with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry for assessment of body composition in geriatric patients. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2020, 40, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Shen, W.; Gallagher, D.; Jones, A., Jr.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Heshka, S.; Heymsfield, S.B. Total-body skeletal muscle mass: Estimation by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry in children and adolescents. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2006, 84, 1014–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abe, T.; Dabbs, N.C.; Nahar, V.K.; Ford, M.A.; Bass, M.A.; Loftin, M. Relationship between dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry-derived appendicular lean tissue mass and total body skeletal muscle mass estimated by ultrasound. Int. J. Clin. Med. 2013, 4, 283–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavasini, R.; Guralnik, J.; Brown, J.C.; di Bari, M.; Cesari, M.; Landi, F.; Vaes, B.; Legrand, D.; Verghese, J.; Wang, C.; et al. Short Physical Performance Battery and all-cause mortality: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2016, 14, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, J.Y.; Jung, H.W.; Kim, K.M.; Kim, M.; Park, C.Y.; Lee, K.P.; Lee, S.Y.; Jang, I.Y.; Jeon, O.H.; Lim, J.Y. Korean Working Group on Sarcopenia Guideline: Expert Consensus on Sarcopenia Screening and Diagnosis by the Korean Society of Sarcopenia, the Korean Society for Bone and Mineral Research, and the Korean Geriatrics Society. Ann. Geriatr. Med. Res. 2023, 27, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, E.; Morley, J.; Cruz-Jentoft, A.; Arai, H.; Kritchevsky, S.; Guralnik, J.; Bauer, J.; Pahor, M.; Clark, B.; Cesari, M. International clinical practice guidelines for sarcopenia (ICFSR): Screening, diagnosis and management. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2018, 22, 1148–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studenski, S.A.; Peters, K.W.; Alley, D.E.; Cawthon, P.M.; McLean, R.R.; Harris, T.B.; Ferrucci, L.; Guralnik, J.M.; Fragala, M.S.; Kenny, A.M.; et al. The FNIH sarcopenia project: Rationale, study description, conference recommendations, and final estimates. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2014, 69, 547–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudart, C.; Demonceau, C.; Reginster, J.Y.; Locquet, M.; Cesari, M.; Cruz Jentoft, A.J.; Bruyère, O. Sarcopenia and health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 1228–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, K.-V.; Hsu, T.-H.; Wu, W.-T.; Huang, K.-C.; Han, D.-S. Is sarcopenia associated with depression? A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Age Ageing 2017, 46, 738–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beaudart, C.; Biver, E.; Reginster, J.-Y.; Rizzoli, R.; Rolland, Y.; Bautmans, I.; Petermans, J.; Gillain, S.; Buckinx, F.; Van Beveren, J. Development of a self-administrated quality of life questionnaire for sarcopenia in elderly subjects: The SarQoL. Age Ageing 2015, 44, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugimoto, T.; Ono, R.; Murata, S.; Saji, N.; Matsui, Y.; Niida, S.; Toba, K.; Sakurai, T. Prevalence and associated factors of sarcopenia in elderly subjects with amnestic mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2016, 13, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voulgaridou, G.; Tyrovolas, S.; Detopoulou, P.; Tsoumana, D.; Drakaki, M.; Apostolou, T.; Chatziprodromidou, I.P.; Papandreou, D.; Giaginis, C.; Papadopoulou, S.K. Diagnostic Criteria and Measurement Techniques of Sarcopenia: A Critical Evaluation of the Up-to-Date Evidence. Nutrients 2024, 16, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, X.F.; Zhang, R.; Chan, H.M. Identification of Chinese dietary patterns and their relationships with health outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Public Health Nutr. 2024, 27, e209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, A.L.M.; Langley, S.R.; Tan, C.F.; Chai, J.F.; Khoo, C.M.; Leow, M.K.-S.; Khoo, E.Y.H.; Moreno-Moral, A.; Pravenec, M.; Rotival, M.; et al. Ethnicity-Specific Skeletal Muscle Transcriptional Signatures and Their Relevance to Insulin Resistance in Singapore. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018, 104, 465–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.A.; MacKenzie, M.; Barbosa-Silva, T.G.; Dionne, I.J.; Ghosh, S.; Olobatuyi, O.V.; Siervo, M.; Ye, M.; Prado, C.M. Sarcopenia Prevalence Using Different Definitions in Older Community-Dwelling Canadians. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2020, 24, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, K.; Yamaguchi, A. Recent advances in pharmacological, hormonal, and nutritional intervention for sarcopenia. Pflug. Arch. 2018, 470, 449–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giallauria, F.; Cittadini, A.; Smart, N.A.; Vigorito, C. Resistance training and sarcopenia. Monaldi Arch. Chest Dis. 2016, 84, 738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnston, A.P.; De Lisio, M.; Parise, G. Resistance training, sarcopenia, and the mitochondrial theory of aging. Appl. Physiol. Nutr. Metab. 2008, 33, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitamura, A.; Seino, S.; Abe, T.; Nofuji, Y.; Yokoyama, Y.; Amano, H.; Nishi, M.; Taniguchi, Y.; Narita, M.; Fujiwara, Y.; et al. Sarcopenia: Prevalence, associated factors, and the risk of mortality and disability in Japanese older adults. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2021, 12, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharahdaghi, N.; Phillips, B.E.; Szewczyk, N.J.; Smith, K.; Wilkinson, D.J.; Atherton, P.J. Links Between Testosterone, Oestrogen, and the Growth Hormone/Insulin-Like Growth Factor Axis and Resistance Exercise Muscle Adaptations. Front. Physiol. 2020, 11, 621226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Q.; Luo, Q.; Song, G. Control of muscle satellite cell function by specific exercise-induced cytokines and their applications in muscle maintenance. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2024, 15, 466–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chow, S.K.; Chim, Y.N.; Cheng, K.Y.; Ho, C.Y.; Ho, W.T.; Cheng, K.C.; Wong, R.M.; Cheung, W.H. Elastic-band resistance exercise or vibration treatment in combination with hydroxymethylbutyrate (HMB) supplement for management of sarcopenia in older people: A study protocol for a single-blinded randomised controlled trial in Hong Kong. BMJ Open 2020, 10, e034921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taaffe, D.R. Sarcopenia: Exercise as a treatment strategy. Aust. Fam. Physician 2006, 35, 130–134. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.-T.; Wu, H.-J.; Chen, Y.-J.; Ho, S.-Y.; Chung, Y.-C. Effects of 8-week kettlebell training on body composition, muscle strength, pulmonary function, and chronic low-grade inflammation in elderly women with sarcopenia. Exp. Gerontol. 2018, 112, 112–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiebaud, R.S.; Loenneke, J.P.; Fahs, C.A.; Rossow, L.M.; Kim, D.; Abe, T.; Anderson, M.A.; Young, K.C.; Bemben, D.A.; Bemben, M.G. The effects of elastic band resistance training combined with blood flow restriction on strength, total bone-free lean body mass and muscle thickness in postmenopausal women. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 2013, 33, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyeok, P.; Daeyeol, K. Effects of Elastic Band Resistance Training on Body Composition, Arterial Compliance and Risks of Falling Index in Elderly Females. JAKAIS 2017, 18, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Shi, Q.; Nong, K.; Li, S.; Yue, J.; Huang, J.; Dong, B.; Beauchamp, M.; Hao, Q. Exercise for sarcopenia in older people: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023, 14, 1199–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishop, D.J.; Lee, M.J.; Picard, M. Exercise as Mitochondrial Medicine: How Does the Exercise Prescription Affect Mitochondrial Adaptations to Training? Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2025, 87, 107–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, M.E.; Rejeski, W.J.; Blair, S.N.; Duncan, P.W.; Judge, J.O.; King, A.C.; Macera, C.A.; Castaneda-Sceppa, C. Physical activity and public health in older adults: Recommendation from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2007, 116, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Physical Activity. Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/behealthy/physical-activity (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Kakehi, S.; Wakabayashi, H.; Inuma, H.; Inose, T.; Shioya, M.; Aoyama, Y.; Hara, T.; Uchimura, K.; Tomita, K.; Okamoto, M.; et al. Rehabilitation Nutrition and Exercise Therapy for Sarcopenia. World J. Mens. Health 2022, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hurst, C.; Robinson, S.M.; Witham, M.D.; Dodds, R.M.; Granic, A.; Buckland, C.; De Biase, S.; Finnegan, S.; Rochester, L.; Skelton, D.A.; et al. Resistance exercise as a treatment for sarcopenia: Prescription and delivery. Age Ageing 2022, 51, afac003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polo-Ferrero, L.; Sáez-Gutiérrez, S.; Dávila-Marcos, A.; Barbero-Iglesias, F.J.; Sánchez-Sánchez, M.C.; Puente-González, A.S.; Méndez-Sánchez, R. Effect of power training on function and body composition in older women with probable sarcopenia. A study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0313072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkesola, G. Neurac-a new treatment method for long-term musculoskeletal pain. J. Fysioterapeuten 2009, 76, 16–25. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.; Chen, J.; Peng, Q.; Chen, J.; Zou, Y.; Liu, G. Effect of Sling Exercise Training on Balance in Patients with Stroke: A Meta-Analysis. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0163351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Feng, W.; Zhou, J.; Huang, F.; Long, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P.; Huang, X.; Yang, M.; Wang, K.; et al. Effects of sling exercise therapy on balance, mobility, activities of daily living, quality of life and shoulder pain in stroke patients: A randomized controlled trial. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2020, 35, 101077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, S.M.; Karpowicz, A.; Fenwick, C.M.; Brown, S.H. Exercises for the torso performed in a standing posture: Spine and hip motion and motor patterns and spine load. J. Strength. Cond. Res. 2009, 23, 455–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.T.; Myung-Gyu, S.; Jun-Woo, L. The Effect of TRX Training and Traditional Resistance Training on Physical Function in Male Senior. KJGD 2016, 24, 97–103. [Google Scholar]

- Hamaguchi, K.; Kurihara, T.; Fujimoto, M.; Iemitsu, M.; Sato, K.; Hamaoka, T.; Sanada, K. The effects of low-repetition and light-load power training on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with sarcopenia: A pilot study. BMC Geriatr. 2017, 17, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souza, M.C.; Jennings, F.; Morimoto, H.; Natour, J. Swiss ball exercises improve muscle strength and walking performance in ankylosing spondylitis: A randomized controlled trial. Rev. Bras. Reumatol. Engl. Ed. 2017, 57, 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundstrup, E.; Jakobsen, M.D.; Andersen, C.H.; Jay, K.; Andersen, L.L. Swiss ball abdominal crunch with added elastic resistance is an effective alternative to training machines. Int. J. Sports Phys. Ther. 2012, 7, 372–380. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Escamilla, R.F.; Lewis, C.; Pecson, A.; Imamura, R.; Andrews, J.R. Muscle Activation Among Supine, Prone, and Side Position Exercises With and Without a Swiss Ball. Sports Health 2016, 8, 372–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franchi, M.V.; Monti, E.; Carter, A.; Quinlan, J.I.; Herrod, P.J.; Reeves, N.D.; Narici, M.V. Bouncing back! counteracting muscle aging with plyometric muscle loading. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetrovsky, T.; Steffl, M.; Stastny, P.; Tufano, J.J. The Efficacy and Safety of Lower-Limb Plyometric Training in Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2019, 49, 113–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyang-Beum, L.; Kim, Y. A Study on the Influence of Combined Training of Dance Sports and Resistance Exercise on Motor Abilities and Sarcopenia Indicators in Old Women. J. Korean Danc. 2017, 35, 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong-Suk, Y. Effects of Korean Dance Participation on the Motor Ability and Wellness in Elderly. Kinesiology 2010, 12, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sintia, D.S.M.; Subadi, I.; Andriati, A. The Effect of Modified Traditional Javanese Dance on Hand Grip Strength and Walking Speed in Elderly. Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 1863–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabeza-Ruiz, R.; García-Massó, X.; Centeno-Prada, R.A.; Beas-Jiménez, J.d.D.; Colado, J.; González, L.-M. Time and frequency analysis of the static balance in young adults with Down syndrome. Gait Posture 2011, 33, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valdés-Badilla, P.; Guzmán-Muñoz, E.; Hernandez-Martinez, J.; Núñez-Espinosa, C.; Delgado-Floody, P.; Herrera-Valenzuela, T.; Branco, B.H.M.; Zapata-Bastias, J.; Nobari, H. Effectiveness of elastic band training and group-based dance on physical-functional performance in older women with sarcopenia: A pilot study. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodzko-Zajko, W.J.; Proctor, D.N.; Fiatarone Singh, M.A.; Minson, C.T.; Nigg, C.R.; Salem, G.J.; Skinner, J.S. American College of Sports Medicine position stand. Exercise and physical activity for older adults. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2009, 41, 1510–1530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riebe, D.; Franklin, B.A.; Thompson, P.D.; Garber, C.E.; Whitfield, G.P.; Magal, M.; Pescatello, L.S. Updating ACSM’s Recommendations for Exercise Preparticipation Health Screening. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2015, 47, 2473–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Song, Y.; Zhu, J.; Ding, P.; Chen, N. Effectiveness of low-load resistance training with blood flow restriction vs. conventional high-intensity resistance training in older people diagnosed with sarcopenia: A randomized controlled trial. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 28427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Hu, M.; Yin, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, L.; Ru, Q.; Xu, G.; Wu, Y. Blood flow restriction training: A new approach for preventing and treating sarcopenia in older adults. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1616874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandya, S.P. Yoga education program for older women diagnosed with sarcopenia: A multicity 10-year follow-up experiment. J. Women Aging 2019, 31, 446–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ross, A.; Thomas, S. The health benefits of yoga and exercise: A review of comparison studies. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2010, 16, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E. Core stability: Assessment and functional strengthening of the hip abductors. Strength. Cond. J. 2005, 27, 21–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, y.k.; Jung, S.-J. The Effect of 16-Weeks’ Pilates Exercise on the Quadriceps–Hamstring Isokinetic strength, Core Stability and Balance in Middle Aged Women. KSW 2023, 18, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Mayer, P.K.; Wu, M.Y.; Liu, D.H.; Wu, P.C.; Yen, H.R. The effect of Tai Chi in elderly individuals with sarcopenia and frailty: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ageing Res. Rev. 2022, 82, 101747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Huang, P.; Cui, S.S.; Tan, Y.Y.; He, Y.C.; Shen, X.; Jiang, Q.Y.; Huang, P.; He, G.Y.; Li, B.Y.; et al. Mechanisms of motor symptom improvement by long-term Tai Chi training in Parkinson’s disease patients. Transl. Neurodegener. 2022, 11, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Oliveira, T.M.D.; Felício, D.C.; Filho, J.E.; Fonseca, D.S.; Durigan, J.L.Q.; Malaguti, C. Effects of whole-body electromyostimulation on health indicators of older people: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. J. Bodyw. Mov. Ther. 2022, 31, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sañudo, B.; Reverte-Pagola, G.; Seixas, A.; Masud, T. Whole-Body Vibration to Improve Physical Function Parameters in Nursing Home Residents Older Than 80 Years: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analysis. Phys. Ther. 2024, 104, pzae025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, K.I.; Ricci, N.A.; de Moraes, S.A.; Perracini, M.R. Virtual reality using games for improving physical functioning in older adults: A systematic review. J. Neuroeng. Rehabil. 2014, 11, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.B.; Lin, C.W.; Huang, H.Y.; Wu, Y.J.; Su, H.T.; Sun, S.F.; Tuan, S.H. Using Virtual Reality-Based Rehabilitation in Sarcopenic Older Adults in Rural Health Care Facilities-A Quasi-Experimental Study. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2021, 29, 866–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, S.; Meng, D.; Wei, M.; Guo, H.; Yang, G.; Wang, Z. Proposal and validation of a new approach in tele-rehabilitation with 3D human posture estimation: A randomized controlled trial in older individuals with sarcopenia. BMC Geriatr. 2024, 24, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- An, Y.; Min, S.; Park, C. Mixed Reality-Based Physical Therapy in Older Adults With Sarcopenia: Preliminary Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Serious Games 2025, 13, e76357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makizako, H.; Shiratsuchi, D.; Akaida, S.; Tateishi, M.; Maeda, K.; Iijima, K.; Shimada, H.; Inoue, T.; Yamada, M.; Momosaki, R.; et al. Effects of digital-based interventions on the outcomes of the eligibility criteria for sarcopenia in healthy older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ageing Res. Rev. 2025, 104, 102663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Roie, E.; Walker, S.; Van Driessche, S.; Delabastita, T.; Vanwanseele, B.; Delecluse, C. An age-adapted plyometric exercise program improves dynamic strength, jump performance and functional capacity in older men either similarly or more than traditional resistance training. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0237921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, H.; Ward, L.; Saper, R.; Fishbein, D.; Dobos, G.; Lauche, R. The Safety of Yoga: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2015, 182, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöllberger, C.; Finsterer, J. Side effects of and contraindications for whole-body electro-myo-stimulation: A viewpoint. BMJ Open Sport. Exerc. Med. 2019, 5, e000619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Stengel, S.; Fröhlich, M.; Ludwig, O.; Eifler, C.; Berger, J.; Kleinöder, H.; Micke, F.; Wegener, B.; Zinner, C.; Mooren, F.C.; et al. Revised contraindications for the use of non-medical WB-electromyostimulation. Evidence-based German consensus recommendations. Front. Sports Act. Living 2024, 6, 1371723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drazich, B.F.; McPherson, R.; Gorman, E.F.; Chan, T.; Teleb, J.; Galik, E.; Resnick, B. In too deep? A systematic literature review of fully-immersive virtual reality and cybersickness among older adults. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2023, 71, 3906–3915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertolazzi, A.; Quaglia, V.; Bongelli, R. Barriers and facilitators to health technology adoption by older adults with chronic diseases: An integrative systematic review. BMC Public. Health 2024, 24, 506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houser, S.H.; Flite, C.A.; Foster, S.L. Privacy and Security Risk Factors Related to Telehealth Services—A Systematic Review. Perspect. Health Inf. Manag. 2023, 20, 1f. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Grune, T.; Shringarpure, R.; Sitte, N.; Davies, K. Age-related changes in protein oxidation and proteolysis in mammalian cells. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2001, 56, B459–B467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwak, H.; Kim, S.B. Aging and sarcopenia. Ann. Geriatr. Med. Res. 2007, 11, 55–59. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Huang, X.; Dong, M.; Wen, S.; Zhou, L.; Yuan, X. The Association Between Sarcopenia and Diabetes: From Pathophysiology Mechanism to Therapeutic Strategy. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes. 2023, 16, 1541–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganapathy, A.; Nieves, J.W. Nutrition and Sarcopenia-What Do We Know? Nutrients 2020, 12, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Na, W.; Oh, D.; Hwang, S.; Chung, B.; Sohn, C. Association between Sarcopenia and Energy and Protein Intakes in Community-dwelling Elderly. Korean J. Community Nutr. 2022, 27, 286–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alliband, K.H.; Parr, T.; Jethwa, P.H.; Brameld, J.M. Active vitamin D increases myogenic differentiation in C2C12 cells via a vitamin D response element on the myogenin promoter. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1322677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agoncillo, M.; Yu, J.; Gunton, J.E. The Role of Vitamin D in Skeletal Muscle Repair and Regeneration in Animal Models and Humans: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, A.; Li, H.; Lin, M.; Xu, F.; Xia, X.; Dai, D.; Sun, R.; Ling, Y.; Qiu, L.; Wang, R.; et al. Effects of active vitamin D analogues on muscle strength and falls in elderly people: An updated meta-analysis. Front. Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1327623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.-S.; Park, J.; Ryu, S.-Y.; Choi, S.-W. 25-Hydroxyvitamin D is associated with osteosarcopenia: The 2009–2011 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Health Inform. Stat. 2020, 45, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, J.; Yang, G.; Sun, W.; Li, Y.; Wang, N.; Wang, J.; Zhao, Y. Association of interleukin-6 with sarcopenia and its components in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional studies. Ann. Med. 2024, 56, 2384664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romagnoli, C.; Brandi, M.L. Muscle Physiopathology in Parathyroid Hormone Disorders. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 764346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, F.; Li, W. Vitamin D and Sarcopenia in the Senior People: A Review of Mechanisms and Comprehensive Prevention and Treatment Strategies. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2024, 20, 577–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.; Hafez, H.A.; Kamel, M.A.; Ghamry, H.I.; Shukry, M.; Farag, M.A. Dietary Vitamin B Complex: Orchestration in Human Nutrition throughout Life with Sex Differences. Nutrients 2022, 14, 3940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suidasari, S.; Uragami, S.; Yanaka, N.; Kato, N. Dietary vitamin B6 modulates the gene expression of myokines, Nrf2-related factors, myogenin and HSP60 in the skeletal muscle of rats. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 3239–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaura, V.; Hopkins, P.M. Recent advances in skeletal muscle physiology. BJA Educ. 2024, 24, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dargelos, E.; Poussard, S.; Brulé, C.; Daury, L.; Cottin, P. Calcium-dependent proteolytic system and muscle dysfunctions: A possible role of calpains in sarcopenia. Biochimie 2008, 90, 359–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.H.; Kim, M.K.; Park, S.E.; Rhee, E.J.; Park, C.Y.; Lee, W.Y.; Baek, K.H.; Song, K.H.; Kang, M.I.; Oh, K.W. The association between daily calcium intake and sarcopenia in older, non-obese Korean adults: The fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES IV) 2009. Endocr. J. 2013, 60, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Baaij, J.H.; Hoenderop, J.G.; Bindels, R.J. Magnesium in man: Implications for health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2015, 95, 1–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souza, A.C.R.; Vasconcelos, A.R.; Dias, D.D.; Komoni, G.; Name, J.J. The Integral Role of Magnesium in Muscle Integrity and Aging: A Comprehensive Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 5127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Veronese, N.; Berton, L.; Carraro, S.; Bolzetta, F.; De Rui, M.; Perissinotto, E.; Toffanello, E.D.; Bano, G.; Pizzato, S.; Miotto, F. Effect of oral magnesium supplementation on physical performance in healthy elderly women involved in a weekly exercise program: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 974–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.-M.; Yang, L.-L.; Chen, S.-H.; Hsu, M.-H.; Chen, I.-J.; Cheng, F.-C. Magnesium sulfate enhances exercise performance and manipulates dynamic changes in peripheral glucose utilization. Eur. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010, 108, 363–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-A.; Lee, S.-Y. The Study of Muscle Strength and Dietary Quality of the Korean Elderly: Based on the 2014-2018 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J. Home Econ. Educ. Res. 2022, 34, 113–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Incheon Dong-gu Public Health Center. Incheon’s Dong-gu Recruits Participants for Second Phase of Frailty Prevention Management. Available online: https://www.icdonggu.go.kr/main/bbs/bbsMsgDetail.do?msg_seq=11651&bcd=press (accessed on 26 August 2025).

- Borde, R.; Hortobágyi, T.; Granacher, U. Dose-Response Relationships of Resistance Training in Healthy Old Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sports Med. 2015, 45, 1693–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izquierdo, M.; Merchant, R.A.; Morley, J.E.; Anker, S.D.; Aprahamian, I.; Arai, H.; Aubertin-Leheudre, M.; Bernabei, R.; Cadore, E.L.; Cesari, M.; et al. International Exercise Recommendations in Older Adults (ICFSR): Expert consensus guidelines. J. Nutr. Health Aging 2021, 25, 824–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milat, A.J.; Newson, R.; King, L.; Rissel, C.; Wolfenden, L.; Bauman, A.; Redman, S.; Giffin, M. A guide to scaling up population health interventions. Public Health Res. Pract. 2016, 26, e2611604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimentel, M.M.; Dos Santos, W.H.B.; Rodrigues, E.K.; Gomes Fernandes, S.G.; de Carvalho, P.F.; Fernandes, A.; Barbosa, P.; Campos Cavalcanti Maciel, Á. Monitoring sarcopenia with wearable devices: A systematic review protocol. BMJ Open 2023, 13, e070507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Working Group | Screening | Assessment (Tests & Cut Offs) | Diagnosis (Criteria & Stages) | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EWGSOP2 (2018) [4] | Clinical suspicion or SARC-F ≥ 4 |

|

| Three-step algorithm (Find–Assess–Confirm/Severity); widely used in Europe |

| AWGS 2019 (2019) [16] | SARC-F ≥ 4 or SARC-CalF ≥ 11 or CC < 34 cm (male), <33 cm (female) |

|

|

|

| FNIH Sarcopenia Project operational criteria (2014) [51] | No formal case finding specified |

| Sarcopenia: low GS and low lean mass |

|

| Stage | Source | Exercise Prescription | Key Notes/Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probable sarcopenia | Ferrero et al. (2023) [77] | 40–60% 1RM; power vs. multicomponent training; emphasis on balance | Early phase, muscle strength decline only, safety and feasibility prioritized |

| Primary sarcopenia | Moretti et al. (2025) [12] | 60–70 min session; 50–70% 1RM RE (10 exercises × 2 sets × 10 reps); ≥30 min/day moderate AE; balance & flexibility | Full structured session, functional improvement beyond muscle mass |

| Severe sarcopenia | Moretti et al. (2025) [12] | 50–55 min session; 30–60% 1RM RE (8 exercises, chair-based); 15 min low-intensity AE; balance-focused | Safety prioritized, reduced load and duration, fall prevention focus |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jang, H.; Song, J.; Kim, J.; Lee, H.; Lee, H.; Park, H.-y.; Shin, H.; Kwon, Y.-e.; Kim, Y.; Yim, J. The Present and Future of Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Exercise Interventions: A Narrative Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12760. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312760

Jang H, Song J, Kim J, Lee H, Lee H, Park H-y, Shin H, Kwon Y-e, Kim Y, Yim J. The Present and Future of Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Exercise Interventions: A Narrative Review. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12760. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312760

Chicago/Turabian StyleJang, Hongje, Jeonghyeok Song, Jeonghun Kim, Hyeongmin Lee, Hyemin Lee, Hye-yeon Park, Huijin Shin, Yeah-eun Kwon, Yeji Kim, and JongEun Yim. 2025. "The Present and Future of Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Exercise Interventions: A Narrative Review" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12760. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312760

APA StyleJang, H., Song, J., Kim, J., Lee, H., Lee, H., Park, H.-y., Shin, H., Kwon, Y.-e., Kim, Y., & Yim, J. (2025). The Present and Future of Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Exercise Interventions: A Narrative Review. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12760. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312760