Application of Plastic Waste as a Sustainable Bitumen Mixture—A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

Positioning Relative to Recent Reviews

| Sl.no. | Type of Plastic Waste | Data | Reference | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Softening | Penetration | Viscosity | |||

| (°C) | (dmm) | (Pa.S) | |||

| St_01 | R-LLDPE | 49.5 | 547 | 0.81 | [10] |

| St_01 | R-LLDPE | 83.7 | 403 | 1.46 | [10] |

| St_01 | R-LLDPE | 119.3 | 253 | 3.52 | [10] |

| St_01 | R-LLDPE | 122.3 | 143 | 5.75 | [10] |

| St_02 | Plastic Waste | 70 | 490 | 0.35 | [11] |

| St_02 | Plastic Waste | 72 | 400 | 0.34 | [11] |

| St_02 | Plastic Waste | 80 | 320 | 0.8 | [11] |

| St_02 | Plastic Waste | 85 | 250 | 0.9 | [11] |

| St_02 | Plastic Waste | 90 | 200 | 1.4 | [11] |

| St_03 | PET | 43 | 550 | NA | [12] |

| St_03 | PET | 51 | 450 | NA | [12] |

| St_03 | PET | 62 | 400 | NA | [12] |

| St_04 | PET | 47.5 | 820 | 6.5 | [13] |

| St_04 | PET | 48.5 | 810 | 7.1 | [13] |

| St_04 | PET | 50 | 780 | 7.55 | [13] |

| St_04 | PET | 51.25 | 740 | 7.8 | [13] |

| St_04 | PET | 53 | 710 | 7.9 | [13] |

| St_04 | PET | 55 | 670 | 8.1 | [13] |

| St_05 | PET | NA | NA | NA | [14] |

| St_05 | PET | NA | NA | NA | [14] |

| St_05 | PET | NA | NA | NA | [14] |

| St_05 | PET | NA | NA | NA | [14] |

| St_06 | Hybrid | 80 | 250 | NA | [15] |

| St_06 | Hybrid | 75 | 250 | NA | [15] |

| St_06 | Hybrid | 90 | 240 | NA | [15] |

| St_07 | LDPE | 43 | 730 | NA | [4] |

| St_07 | LDPE | 48 | 580 | NA | [4] |

| St_07 | LDPE | 57 | 550 | NA | [4] |

| St_07 | LDPE | 61 | 530 | NA | [4] |

| St_07 | LDPE | 63 | 500 | NA | [4] |

| St_07 | LDPE | 66 | 460 | NA | [4] |

| St_08 | LDPE | NA | 420 | NA | [14] |

| St_08 | LDPE | NA | 400 | NA | [14] |

| St_08 | LDPE | NA | 400 | NA | [14] |

| St_08 | LDPE | NA | 420 | NA | [14] |

| St_09 | PET | NA | NA | NA | [16] |

| St_09 | HDPE | NA | NA | NA | [16] |

| St_09 | PP | NA | NA | NA | [16] |

| St_09 | PS | NA | NA | NA | [16] |

| St_09 | PVC | NA | NA | NA | [16] |

| St_10 | HP | NA | NA | 2.4 | [17] |

| St_10 | HP | NA | NA | 0.9 | [17] |

| St_10 | HP | NA | NA | 0.5 | [17] |

| St_10 | HP | NA | NA | 1.2 | [17] |

| St_11 | PVC | 42 | 97 | NA | [18] |

| St_11 | PVC | 43 | 91 | NA | [18] |

| St_11 | PVC | 43.55 | 84 | NA | [18] |

| St_12 | Hybrid | 67.33 | 29 | NA | [5] |

| St_12 | Hybrid | 83.33 | 59 | NA | [5] |

| St_12 | Hybrid | 73 | 56 | NA | [5] |

| St_12 | Hybrid | 73 | 53 | NA | [5] |

| St_12 | Hybrid | 115 | 47 | NA | [5] |

| St_13 | PVC | 40.5 | 165 | 0.245 | [18] |

| St_13 | PVC | 41.3 | 157 | 0.282 | [18] |

| St_13 | PVC | 42 | 150 | 0.298 | [18] |

| St_14 | PP | 55 | 760 | NA | [19] |

| St_14 | PP | 59 | 710 | NA | [19] |

| St_14 | PP | 61 | 660 | NA | [19] |

| St_14 | PP | 66 | 590 | NA | [19] |

| St_14 | PP | 71 | 530 | NA | [19] |

| St_14 | PP | 78 | 490 | NA | [19] |

| St_14 | PP | 81 | 450 | NA | [19] |

| St_14 | PP | 83 | 390 | NA | [19] |

| St_15 | PVC | 6 | 463 | NA | [18] |

| St_15 | PVC | 5.3 | 490 | NA | [18] |

| St_15 | PVC | 3.833 | 540 | NA | [18] |

| St_16 | R-LLDPE | 44.1 | 593 | 0.62 | [10] |

| St_16 | R-LLDPE | 49.5 | 547 | 0.81 | [10] |

| St_16 | R-LLDPE | 83.7 | 403 | 1.46 | [10] |

| St_16 | R-LLDPE | 119.3 | 253 | 3.52 | [10] |

| St_16 | R-LLDPE | 122.3 | 143 | 5.57 | [10] |

| St_17 | PVC | 45 | 81 | NA | [18] |

| St_17 | PVC | 46.25 | 73 | NA | [18] |

| St_17 | PVC | 51 | 83 | NA | [18] |

| St_18 | LDPE and LLDPE | 10 | NA | NA | [20] |

| St_18 | LDPE and LLDPE | 5 | NA | NA | [20] |

| St_18 | LDPE and LLDPE | 29 | NA | NA | [20] |

| St_18 | LDPE and LLDPE | 130 | NA | NA | [20] |

| St_18 | LDPE and LLDPE | 131 | NA | NA | [20] |

| St_19 | PVC | 41.05 | 135 | 0.25 | [18] |

| St_19 | PVC | 41.85 | 122 | 0.3 | [18] |

| St_19 | PVC | 42.25 | 106 | 0.39 | [18] |

| St_20 | PET | NA | 450 | NA | [21] |

| St_20 | PET | NA | 420 | NA | [21] |

| St_20 | PET | NA | 390 | NA | [21] |

| St_20 | PET | NA | 350 | NA | [21] |

| St_20 | PET | NA | 300 | NA | [21] |

| St_20 | HDPE | NA | 450 | NA | [21] |

| St_20 | HDPE | NA | 440 | NA | [21] |

| St_20 | HDPE | NA | 430 | NA | [21] |

| St_20 | HDPE | NA | 460 | NA | [21] |

| St_20 | HDPE | NA | 470 | NA | [21] |

| St_20 | LDPE | NA | 460 | NA | [21] |

| St_20 | LDPE | NA | 450 | NA | [21] |

| St_20 | LDPE | NA | 410 | NA | [21] |

| St_20 | LDPE | NA | 415 | NA | [21] |

| St_20 | LDPE | NA | 450 | NA | [21] |

| St_21 | PET | 46.9 | 80 | 0.38 | [22] |

| St_21 | PET | 48.4 | 73 | 0.44 | [22] |

| St_21 | PET | 48.8 | 65 | 0.41 | [22] |

| St_21 | PET | 50.1 | 60 | 0.45 | [22] |

| St_22 | PET | NA | 101.5 | 0.65 | [5] |

| St_22 | PET | 44.5 | 102.75 | 0.73 | [5] |

| St_22 | PET | 44.8 | 103.5 | 0.79 | [5] |

| St_22 | PET | 45.2 | 104.75 | 0.86 | [5] |

| St_22 | PET | 47 | 110 | 0.91 | [5] |

| St_22 | PET | 47.5 | 112 | 0.95 | [5] |

| St_23 | PP | 55.7 | 47 | NA | [23] |

| St_23 | PP | 54.4 | 49 | NA | [23] |

| St_23 | PP | 53.9 | 53 | NA | [23] |

| St_24 | HDPE | NA | NA | NA | [24] |

| St_24 | HDPE | NA | NA | NA | [24] |

| St_24 | HDPE | NA | NA | NA | [24] |

| St_24 | HDPE | NA | NA | NA | [24] |

| St_24 | LDPE | NA | NA | NA | [24] |

| St_24 | LDPE | NA | NA | NA | [24] |

| St_24 | LDPE | NA | NA | NA | [24] |

| St_25 | PET | 52 | 730 | NA | [6] |

| St_25 | PET | 54 | 650 | NA | [6] |

| St_25 | PET | 57 | 610 | NA | [6] |

| St_25 | PET | 56 | 620 | NA | [6] |

| St_25 | PET | 55 | 640 | NA | [6] |

| St_26 | R-LLDPE | 50 | 55 | 0.8 | [10] |

| St_26 | R-LLDPE | 80 | 40 | 1.5 | [10] |

| St_26 | R-LLDPE | 118 | 25 | 3.5 | [10] |

| St_26 | R-LLDPE | 120 | 15 | 6.7 | [10] |

| St_27 | HDPE | 62.2 | 323 | 0.54 | [25] |

| St_27 | HDPE | 68.6 | 285 | 0.78 | [25] |

| St_27 | HDPE | 73.5 | 218 | 1.28 | [25] |

| St_27 | HDPE | 75.7 | 199 | 1.42 | [25] |

| St_27 | HDPE | 74 | 213 | 1.54 | [25] |

| St_28 | PET | 56 | 422 | NA | [26] |

| St_28 | PET | 59.4 | 400 | NA | [26] |

| St_28 | PET | 60.1 | 383 | NA | [26] |

| St_28 | PET | 61 | 361 | NA | [26] |

| St_29 | PE-P | 66 | NA | 1.5 | [9] |

| St_29 | PE-S | 90 | NA | 2.7 | [9] |

| St_30 | PP/PE | 65.1 | 470 | 0.618 | [8] |

| St_30 | PP/PE | 61.9 | 473 | 0.609 | [8] |

| St_30 | PP/PE | 63.6 | 464 | 0.626 | [8] |

| St_30 | PP/PE | 63.3 | 475 | 0.606 | [8] |

| St_30 | PP/PE | 62.9 | 473 | 0.612 | [8] |

| St_30 | PP/PE | 62.6 | 484 | 0.6 | [8] |

| St_30 | PP/PE | 62.5 | 473 | 0.617 | [8] |

| St_31 | PET | 45 | 666 | 0.196 | [7] |

| St_31 | PET | 46.5 | 649 | 0.238 | [7] |

| St_31 | PET | 48 | 638 | 0.293 | [7] |

| St_31 | PET | 50.5 | 612 | 0.341 | [7] |

| St_31 | PET | 53 | 594 | 0.407 | [7] |

| St_31 | PET | 55.5 | 573 | 0.459 | [7] |

| St_31 | PET | 56 | 569 | 0.537 | [7] |

| St_32 | LDPE | 52.5 | 55 | 0.54 | [27] |

| St_32 | LDPE | 52.7 | 49 | 0.72 | [27] |

| St_32 | LDPE | 61.8 | 38 | 0.84 | [27] |

| St_33 | SBS | NA | NA | NA | [28] |

| St_33 | SBS | NA | NA | NA | [28] |

| St_33 | SBS | NA | NA | NA | [28] |

| St_33 | EVA | NA | NA | NA | [28] |

| St_33 | EVA | NA | NA | NA | [28] |

| St_33 | EVA | NA | NA | NA | [28] |

| St_33 | MR6 | NA | NA | NA | [28] |

| St_33 | MR10 | NA | NA | NA | [28] |

| St_34 | Waste Plastic | 45 | 55 | NA | [12] |

| St_34 | Waste Plastic | 47.5 | 53 | NA | [12] |

| St_34 | Waste Plastic | 53 | 43 | NA | [12] |

| St_35 | HDPE | NA | NA | NA | [29] |

| St_35 | HDPE | NA | NA | NA | [29] |

| St_35 | HDPE | NA | NA | NA | [29] |

| St_36 | VPP | 51.6 | 45 | 0.2 | [30] |

| St_36 | VPP | 50.3 | 50 | 0.18 | [30] |

| St_36 | VPP | 50.1 | 54 | 0.175 | [30] |

| St_36 | VPP | 50 | 57 | 0.17 | [30] |

| St_36 | VPP | 49.8 | 60 | 0.16 | [30] |

| St_37 | LDPE | 63 | 320 | 0.7 | [31] |

| St_37 | HDPE | 61 | 270 | 0.578 | [31] |

| St_37 | LLDPE | 59 | 210 | 0.38 | [31] |

| St_37 | PP | 63 | 240 | 0.6 | [31] |

| St_37 | EVA | 57 | 500 | 0.98 | [31] |

| St_37 | EBA | 58 | 560 | 0.94 | [31] |

| St_38 | PET | 75 | 730 | NA | [32] |

| St_38 | PET | 78 | 710 | NA | [32] |

| St_38 | PET | 85 | 670 | NA | [32] |

| St_38 | PET | 98 | 560 | NA | [32] |

| St_38 | PET | 99 | 530 | NA | [32] |

| St_38 | PET | 100 | 500 | NA | [32] |

| St_39 | LDPE | 77 | 300 | NA | [33] |

| St_39 | LDPE | 77 | 300 | NA | [33] |

| St_39 | LDPE | 77 | 300 | NA | [33] |

| St_39 | LDPE | 77 | 300 | NA | [33] |

| St_39 | HDPE | 87 | 255 | NA | [33] |

| St_39 | HDPE | 87 | 255 | NA | [33] |

| St_39 | HDPE | 87 | 255 | NA | [33] |

| St_39 | HDPE | 87 | 255 | NA | [33] |

| St_40 | PET | 47 | 650 | NA | [34] |

| St_40 | PET | 47.5 | 620 | NA | [34] |

| St_40 | PET | 48.5 | 600 | NA | [34] |

| St_41 | PVC | 80.7 | 670 | NA | [35] |

| St_41 | PVC | 81.2 | 490 | NA | [35] |

| St_42 | Waste Plastic | 50 | 138 | 2 | [36] |

| St_42 | Waste Plastic | 55 | 100 | 4 | [36] |

| St_42 | Waste Plastic | 54 | 90 | 4.1 | [36] |

| St_42 | Waste Plastic | 54 | 85 | 4.9 | [36] |

| St_42 | Waste Plastic | 55 | 85 | 3.5 | [36] |

| St_42 | Waste Plastic | 59 | 80 | 5.8 | [36] |

| St_43 | PVC | 55 | 550 | 4.3 | [37] |

| St_43 | PVC | 58 | 440 | 5 | [37] |

| St_44 | Hybrid | NA | NA | NA | [38] |

| St_44 | Hybrid | NA | NA | NA | [38] |

| St_44 | Hybrid | NA | NA | NA | [38] |

| St_44 | Hybrid | NA | NA | NA | [38] |

| St_45 | PET | 52 | 49 | NA | [39] |

| St_45 | PET | 53 | 35 | NA | [39] |

| St_45 | PET | 57 | 29 | NA | [39] |

| St_46 | PET | 46.5 | 649 | 3.73 | [40] |

| St_46 | PET | 48 | 638 | 3.93 | [40] |

| St_46 | PET | 50.5 | 612 | 4.02 | [40] |

| St_46 | PET | 53 | 594 | 4.13 | [40] |

| St_46 | PET | 55.5 | 573 | 4.59 | [40] |

| St_46 | PET | 56 | 569 | 4.88 | [40] |

| St_46 | PET | 56.7 | 550 | 4.93 | [40] |

| St_47 | E-waste plastic | 54 | 643 | 0.99 | [41] |

| St_47 | E-waste plastic | 55 | 114.33 | 1.14 | [41] |

| St_47 | E-waste plastic | 66.7 | 123.33 | 1.46 | [41] |

| St_47 | E-waste plastic | 74.5 | 113.33 | 1.86 | [41] |

| St_47 | E-waste plastic | 85 | 313 | 2.01 | [41] |

| St_48 | Plastic | 48.5 | 70 | NA | [42] |

| St_48 | Plastic | 45 | 59 | NA | [42] |

| St_48 | Crumbed rubber | 47.5 | 68 | NA | [42] |

| St_48 | Crumbed rubber | 42 | 54 | NA | [42] |

| St_49 | PET+TETA | NA | NA | 5.3 | [43] |

| St_49 | PET+EA | NA | NA | 5.05 | [43] |

| St_50 | HDPE | 54 | 140 | NA | [36] |

| St_50 | HDPE | 56 | 89 | NA | [36] |

| St_50 | HDPE | 57 | 90 | NA | [36] |

| St_50 | HDPE | 58 | 81 | NA | [36] |

| St_50 | HDPE | 61 | 80 | NA | [36] |

| St_50 | HDPE | 64 | 75 | NA | [36] |

| St_50 | HDPE | 70 | 70 | NA | [36] |

| St_50 | PP | 54 | 140 | NA | [36] |

| St_50 | PP | 50 | 138 | NA | [36] |

| St_50 | PP | 55 | 103 | NA | [36] |

| St_50 | PP | 53 | 90 | NA | [36] |

| St_50 | PP | 54 | 86 | NA | [36] |

| St_50 | PP | 53 | 85 | NA | [36] |

| St_50 | PP | 59 | 80 | NA | [36] |

| St_51 | PET | 45 | 75 | 4 | [44] |

| St_51 | PET | 46.5 | 50 | 4.5 | [44] |

| St_51 | PET | 47 | 40 | 6 | [44] |

| St_51 | PET | 51 | 38 | 8.5 | [44] |

| St_51 | PET | 52 | 25 | 10 | [44] |

| Model | Key Hyperparameters | Search Range |

|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | Learning rate; max. depth; n_estimators; subsample; colsample_bytree; reg_lambda | 0.01–0.3; 3–10; 100–500; 0.6–1.0; 0.6–1.0; 0–2.0 |

| Rando Forest | n_estimators; max. depth; min_samples_split; min_samples_leaf; max_features | 200–800, 3–20, 2–10, 1–5 (auto square) |

| Ridge Regression | alpha (L2 regularization) | 10(−04)–10(04) (log-spaced) |

2. Methodology for Data Extraction and Analysis

Machine Learning Workflow

- Median baseline;

- Ridge regression;

- Random forest;

- XGBoost regression.

- Mean Absolute Error (MAE);

- Root Mean Square Error (RMSE);

- Coefficient of Determination (R2).

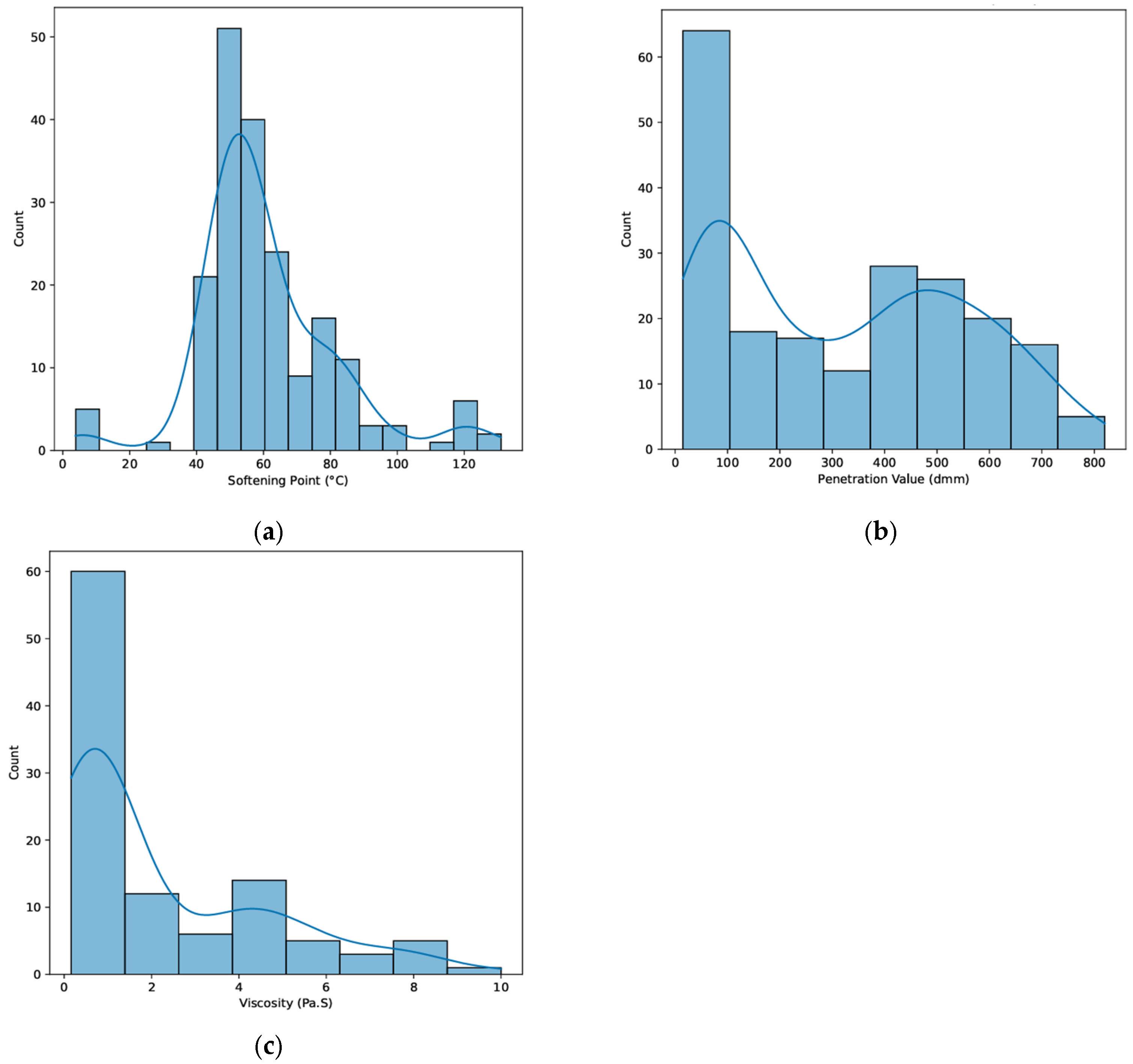

3. Results

4. Discussion

- Incorporating plastic waste generally increases softening point, decreases penetration, and increases viscosity, confirming the stiffening effect that improves rutting resistance.

- The softening point model demonstrated good predictive performance (R2 = 0.79), although slight underestimation occurred at high values.

- The penetration model showed moderate accuracy (R2 = 0.61), reflecting its sensitivity to factors such as plastic type, particle size, and mixing uniformity.

- The viscosity model demonstrated good prediction performance (R2 = 0.79), especially in the low- to mid-range viscosity values.

- Permutation analyses indicated that dosage and plastic type were the strongest predictors across targets. In our dataset, predictions became more sensitive beyond ~5% dosage: small changes above this threshold produced larger shifts in softening point and viscosity compared to changes below 5%. Partial-dependence inspection showed monotonic stiffening with dose for PE/PET classes, with diminishing returns beyond ~10–12% as mixing/dispersion limits emerge. Mixing temperature/time exhibited weaker effects within the commonly reported ranges (160–180 °C; 30–90 min).

- Tree-based ML algorithms (Random Forest and XGBoost) outperformed linear models, demonstrating the effectiveness of nonlinear approaches in predicting binder behavior.

- Previous studies support that PE, PET, and other plastic wastes improve high-temperature stability but may reduce ductility.

4.1. Compatibility and Dispersion Behavior

4.2. Environmental and Economic Context

4.3. Further Research and Direction

5. Conclusions

- Four models were evaluated: median baseline, linear regression, random forest, and XGBoost. Tree-based models (random forest and XGBoost) outperformed the other models in predicting binder properties, demonstrating their ability to capture nonlinear interaction.

- Softening point predictions show good accuracy (R2 = 0.74, MAE = 81.501), with close alignment between predicted and observed values. However, performance prediction errors increased at the upper-range values, indicating the need for additional features to fully capture variability.

- The penetration predictions demonstrated moderate accuracy (R2 = 0.614, MAE = 7.511), showing more sensitivity to uncontrolled parameters such as plastic type, particle size, and mixing homogeneity.

- Viscosity predictions also showed good performance (R2 = 0.791, MAE = 0.834), particularly in the low- and mid-range viscosity data.

- The results are consistent with existing research that shows that plastic modification generally increases softening point and viscosity while decreasing penetration. This occurs because thermoplastic polymer chains reinforce the bitumen matrix and restrict molecular movement, thereby stiffening the binder and improving rutting resistance at high service temperatures.

- The findings demonstrate that nonlinear machine learning techniques outperform baseline or linear models in predicting binder performance, encouraging their usage in sustainable pavement design research.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Geyer, R.; Jambeck, J.R.; Law, K.L. Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1700782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, G. Recycled Waste Plastic for Extending and Modifying Asphalt Binders. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Greg-White/publication/324908837_RECYCLED_WASTE_PLASTIC_FOR_EXTENDING_AND_MODIFYING_ASPHALT_BINDERS/links/5aea9deda6fdcc03cd90c94c/RECYCLED-WASTE-PLASTIC-FOR-EXTENDING-AND-MODIFYING-ASPHALT-BINDERS.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Sojobi, A.O.; Nwobodo, S.E.; Aladegboye, O.J. Recycling of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic bottle wastes in bituminous asphaltic concrete. Cogent Eng. 2016, 3, 1133480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huda, S.; Anzar, H. Plastic Roads: A Recent Advancement in Waste Management. 2016. Available online: https://www.ijert.org/research/plastic-roads-a-recent-advancement-in-waste-management-IJERTV5IS090574.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Edukondalu, K.; Adusumalli, M.; Divya, D.; Sulthan, S.S.; Naveen, K.G.; Srihari, I.; Rakesh, K. Use of Waste Plastic Materials in Flexible Pavements. Int. J. Innov. Res. Comput. Sci. Technol. 2022, 10, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulzat, A.; Madeniyet, Y.; Dana, Y.; Aiganym, I.; Sofya, M. The use of polyethylene terephthalate waste as modifiers for bitumen systems. East.-Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2022, 3, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, M.S.; Ahmad, S.A. The impact of polyethylene terephthalate waste on different bituminous designs. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2022, 69, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhou, L.; Sun, J.; Wang, S.; Zhang, M.; Hu, Y.; Temitope, A.A. Analysis of the Influence of Production Method, Plastic Content on the Basic Performance of Waste Plastic Modified Asphalt. Polymers 2022, 14, 4350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakar, M.R.; Mikhailenko, P.; Piao, Z.; Bueno, M.; Poulikakos, L. Analysis of waste polyethylene (PE) and its by-products in asphalt binder. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 280, 122492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nizamuddin, S.; Jamal, M.; Gravina, R.; Giustozzi, F. Recycled plastic as bitumen modifier: The role of recycled linear low-density polyethylene in the modification of physical, chemical and rheological properties of bitumen. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 266, 121988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayush, V. Utilization of Recycled Plastic Waste in Road Construction. 2021. Available online: https://www.ijert.org/research/utilization-of-recycled-plastic-waste-in-road-construction-IJERTV10IS050289.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Imanbayev, Y.; Bussurmanova, A.; Ongarbayev, Y.; Serikbayeva, A.; Sydykov, S.; Tabylganov, M.; Akkenzheyeva, A.; Izteleu, N.; Mussabekova, Z.; Amangeldin, D.; et al. Modification of Bitumen with Recycled PET Plastics from Waste Materials. Polymers 2022, 14, 4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, B.; Ms, R. Study on Effect of Plastic Waste on Softer Grade (Vg-10) Bitumen. Int. J. Innov. Res. Eng. Manag. (IJIREM) 2023, 10, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashaan, N.; Chegenizadeh, A.; Nikraz, H. Laboratory Properties of Waste PET Plastic-Modified Asphalt Mixes. Recycling 2021, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tri, S.; Chusnul, A.; Shaopeng, E.; Fardzanela, S. Rutting Resistance of Agricultural-Waste-Plastic Based Modified Bitumen. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2025, 13, 1647–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Fang, Y.; Liu, L.; Zhu, Q. Multi-Damage Healing Ability of Modified Bitumen with Waste Plastics Based on Rheological Property. Materials 2025, 18, 3827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elnaml, I.; Liu, J.; Mohammad, L.; Dylla, H.; Wasiuddin, N.; Cooper, S.; Cooper, S. Recycling waste plastics in asphalt mixture: Engineering performance and environmental assessment. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 453, 142180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köfteci, S.; Ahmedzade, P.; Kultayev, B. Performance evaluation of bitumen modified by various types of waste plastics. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 73, 592–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaac, H. Recycling Waste Plastics in Asphalt Pavements. 2023. Available online: https://onlinepubs.trb.org/onlinepubs/circulars/ec291.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Dai, X.L.; Marie, E.; Hassan, M.; Filippo, G. Performance Evaluation of Post-Consumer and Post-Industrial Recycled Plastics as Binder Modifier in Asphalt Mixes. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashaan, N.; Chegenizadeh, A.; Nikraz, H. A Comparison on Physical and Rheological Properties of Three Different Waste Plastic-Modified Bitumen. Recycling 2022, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelaziz, M.; Mohamed, K. Rheological Evaluation of Bituminous Binder Modified with Waste Plastic Material. 2010. Available online: https://eprints.um.edu.my/3186/1/MAHREZ_Abdelaziz.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Hu, T.; Luo, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Chu, Y.; Hu, G.; Xu, X. Mechanochemical preparation and performance evaluations of bitumen-used waste polypropylene modifiers. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2024, 21, e03471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, U.; Zamin, B.; Tariq Bashir, M.; Ahmad, M.; Sabri, M.M.; Keawsawasvong, S. Comprehensive Study on the Performance of Waste HDPE and LDPE Modified Asphalt Binders for Construction of Asphalt Pavements Application. Polymers 2022, 14, 3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hung, N.; Van Phuc, L.; Thanh Phong, N. Performance Evaluation of Waste High Density Polyethylene as a Binder Modifier for Hot Mix Asphalt. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 2023, 18, 102–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moses, M.; Reneta, K.; Nsahlai, N.; Jules, N.; Kingsly, B.; Adriel, C. Physico-Mechanical Characterization Of Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET)-Modified Ashalt For Enchanced Flexible Pavements. IOSR J. Mech. Civ. Eng. (IOSR-JMCE) 2025, 22, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joni, H.H.; Al-Rubaee, R.H.A.; Al-zerkani, M.A. Characteristics of asphalt binder modified with waste vegetable oil and waste plastics. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 737, 012126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, G.; Hall, F. Comparing Asphalt Modified with Recycled Plastic Polymers to Conventional Polymer Modified Asphalt; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Elnaml, I.; Liu, J.; Mohammad, L.N.; Wasiuddin, N.; Cooper, S.B.; Cooper, S.B. Developing Sustainable Asphalt Mixtures Using High-Density Polyethylene Plastic Waste Material. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gürü, M.; Çubuk, M.K.; Arslan, D.; Farzanian, S.A.; Bilici, İ. An approach to the usage of polyethylene terephthalate (PET) waste as roadway pavement material. J. Hazard. Mater. 2014, 279, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nizamuddin, S.; Boom, Y.J.; Giustozzi, F. Sustainable Polymers from Recycled Waste Plastics and Their Virgin Counterparts as Bitumen Modifiers: A Comprehensive Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jexembayeva, A.; Konkanov, M.; Aruova, L.; Kirgizbayev, A.; Zhaksylykova, L. Modifying Bitumen with Recycled PET Plastics to Enhance Its Water Resistance and Strength Characteristics. Polymers 2024, 16, 3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.; Hafeez, I.; Jamal; Ullah, R. Sustainable use of waste plastic modifiers to strengthen the adhesion properties of asphalt mixtures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2020, 235, 117496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umar, H.; Abdur, R.; Ammad Hassan, K.; Zia Ur, R. Use of Plastic Wastes and Reclaimed Asphalt For Sustainable Development. Balt. J. Road Bridge Eng. 2020, 15, 182–196. [Google Scholar]

- Manju, R.; Sathya, S.; Sheema, K. Use of Plastic Waste in Bituminous Pavement. Int. J. ChemTech Res. 2017, 10, 804–811. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Rmanju-Anand/publication/320243162_Use_of_Plastic_Waste_in_Bituminous_Pavement/links/59d70660458515db19c5d8a3/Use-of-Plastic-Waste-in-Bituminous-Pavement.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Appiah, J.K.; Berko-Boateng, V.N.; Tagbor, T.A. Use of waste plastic materials for road construction in Ghana. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2017, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambika, B.; Girish, S.; Gajendra, K. A sustainable approach: Utilization of waste PVC in asphalting of roads. Constr. Build. Mater. 2014, 54, 113–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.M.; Kabir, S.; Alhussain, M.A.; Almansoor, F.F. Asphalt Design Using Recycled Plastic and Crumb-rubber Waste for Sustainable Pavement Construction. Procedia Eng. 2016, 145, 1557–1564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffar, A.-M.; Sahar, M. Preparation of sustainable asphalt pavements using polyethylene terephthalate waste as a modifier. Zast. Mater. 2017, 58, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik Shoeb, A.; Fareed, M. Characterization of Bitumen Mixed With Plastic Waste. Int. J. Transp. Eng. 2016, 3, 85–91. [Google Scholar]

- Santhanam, N.; Ramesh, B.; Agarwal, S.G. Experimental investigation of bituminous pavement (VG30) using E-waste plastics for better strength and sustainable environment. Mater. Today Proc. 2020, 22, 1175–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abhaykumar, W.; Mudassir, W. Use of Waste Plastic and Waste Rubber in Aggregate and Bitumen for Road Materials. International Journal of Emerging Technology and Advanced Engineering Website: www.ijetae.com. 2008. Available online: https://xilirprojects.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/1.-Use-of-Waste-Plastic-and-Waste-Rubber-in-Aggregate-and.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Xu, X.; Leng, Z.; Lan, J.; Wang, W.; Yu, J.; Bai, Y.; Sreeram, A.; Hu, J. Sustainable Practice in Pavement Engineering through Value-Added Collective Recycling of Waste Plastic and Waste Tyre Rubber. Engineering 2021, 7, 857–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agha, N.; Hussain, A.; Ali, A.S.; Qiu, Y. Performance Evaluation of Hot Mix Asphalt (HMA) Containing Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Using Wet and Dry Mixing Techniques. Polymers 2023, 15, 1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waples, J. Mean Absolute Error Explained: Measuring Model Accuracy. 2025. Available online: https://www.datacamp.com/tutorial/mean-absolute-error (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Schneider, P. Mean Absolute Error—An Overview|ScienceDirect Topics. 2022. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/mean-absolute-error (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- ScienceDirect. Root Mean Square Error—An Overview|ScienceDirect Topics. 2022. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/engineering/root-mean-square-error (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Romeo, G. Determination Coefficient—An Overview|ScienceDirect Topics. 2020. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/mathematics/determination-coefficient (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Amani, A.A.; Abeer, A.-M.; Gabriel, B.; Sameh, A.; Ahmed, S.B.A.; Ali, A. Utilizing waste polyethylene for improved properties of asphalt binders and mixtures: A review. Advances in Science and Technology. Res. J. 2024, 19, 301–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeiada, W.; Al-Khateeb, G.; Hajj, E.Y.; Ezzat, H. Rheological properties of plastic-modified asphalt binders using diverse plastic wastes for enhanced pavement performance in the UAE. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 452, 138922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Ma, J.; Xu, X.; Pu, T.; He, Y.; Zhang, Q. Performance Evaluation of Using Waste Polyethylene Terephthalate (PET) Derived Additives for Asphalt Binder Modification. Waste Biomass Valorizat. 2025, 16, 601–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat Hosseini, A.; Hajikarimi, P.; Gandomi, M.; Moghadas Nejad, F.; Gandomi, A.H. Optimized machine learning approaches for the prediction of viscoelastic behavior of modified asphalt binders. Constr. Build. Mater. 2021, 299, 124264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopakumar, N.; Biligiri, K.P. Morphological and Rheological Assessment of Waste Plastic-Modified Asphalt-Rubber Binder. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Maintenance and Rehabilitation of Pavements, Guimarães, Portugal, 24–26 July 2024; Pereira, P., Pais, J., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 405–415. [Google Scholar]

| Column Name | Data Type | Data Category | Sample Value | Null Count | Completeness (%) | Unique Value | Value Range | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study_id | object | Text | St_01, St_01, St_01 | 0 | 100 | 51 | NA | NA |

| Type of plastic | object | Text | R-LLDPE, R-LLDPE, R-LLDPE | 0 | 100 | 28 | NA | NA |

| Dose of plastic (%) | float64 | Numeric | 3.0, 3.0, 3.0 | 0 | 100 | 25 | 0–36 | 5.43 |

| Mixing Temp. | float64 | Numeric | 170.0, 170.0, 170.0 | 15 | 94 | 17 | 120–250 | 170 |

| Mixing Rate | float64 | Numeric | 3500.0, 3500.0, 3500.0 | 85 | 66 | 16 | 20–13,000 | 2110 |

| Mixing Time | float64 | Numeric | 90.0, 90.0, 90.0 | 42 | 83 | 17 | 2–180 | 49 |

| Type of Bitumen | object | Text | C320, C320, C320 | 11 | 95 | 39 | NA | NA |

| Age/unage | object | Text | Unaged, Unaged, Unaged | 231 | 7.6 | 2 | NA | NA |

| Softening point | float64 | Numeric | 49.5, 83.7, 119.3 | 57 | 77.2 | 102 | 3.83–131 | 61 |

| Penetration | float64 | Numeric | 547.0, 403.0, 253.0 | 44 | 82.4 | 120 | 15–820 | 320 |

| Viscosity | float64 | Numeric | 0.81, 1.46, 3.52 | 144 | 42.4 | 94 | 0.16–10 | 2.2 |

| Plastic Type | n (soft) | Mean Soft (°C) | Range Soft (°C) | n (Pen) | Mean Pen (dmm) | Range Pen (dmm) | n (Visc) | Mean visc (Pa.S) | Range Visc (Pa.s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crumbed rubber | 2 | 44.75 | 42–47 | 2 | 61 | 54–68 | 0 | - | - |

| E-waste plastic | 5 | 67.04 | 54–85 | 5 | 261 | 113.33–643 | 5 | 1.492 | 0.99–2.010 |

| EBA | 1 | 58 | 58–58 | 1 | 560 | 560–560 | 1 | 0.94 | 0.94–0.94 |

| EVA | 1 | 57 | 57–57 | 1 | 500 | 500–500 | 1 | 0.98 | 0.98–0.98 |

| HDPE | 17 | 69.59 | 54–87 | 22 | 245.59 | 70–470 | 6 | 1.023 | 0.54–1.54 |

| HP | 0 | - | - | 0 | - | - | 4 | 1.25 | 0.5–2.4 |

| Hybrid | 8 | 82.08 | 67.33–115 | 8 | 123 | 29–250 | 0 | - | - |

| LDPE | 14 | 62.57 | 43–77 | 23 | 384.22 | 38–730 | 4 | 0.7 | 0.54–0.84 |

| LDPE and LLDPE | 5 | 61 | 5–131 | 0 | - | - | 0 | - | - |

| LLDPE | 1 | 59 | 59–59 | 1 | 210 | 210–210 | 1 | 0.38 | 0.38–0.38 |

| Model | Target | Avg. MAE | Avg. RSME | Avg_R2 | Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median Baseline | Softening Point (°C) | 14.154 | 21.4906 | −0.0682 | 193 |

| Linear Model (Ridge) | Softening Point (°C) | 14.4171 | 18.6615 | 0.1014 | 193 |

| Random Forest | Softening Point (°C) | 11.3263 | 16.1304 | 0.3674 | 193 |

| XGBoost | Softening Point (°C) | 11.0965 | 15.9136 | 0.3894 | 193 |

| Median Baseline | Penetration (dmm) | 206.7258 | 231.3153 | −0.0081 | 206 |

| Linear Model (Ridge) | Penetration (dmm) | 235.4897 | 275.0583 | −0.9856 | 206 |

| Random Forest | Penetration (dmm) | 238.3021 | 275.3899 | −0.9717 | 206 |

| XGBoost | Penetration (dmm) | 230.3848 | 272.7678 | −0.9346 | 206 |

| Median Baseline | Viscosity (Pa.S) | 1.7106 | 2.7141 | −0.3008 | 106 |

| Linear Model (Ridge) | Viscosity (Pa.S) | 2.557 | 3.0389 | −4.0487 | 106 |

| Random Forest | Viscosity (Pa.S) | 1.7616 | 2.1424 | −0.8741 | 106 |

| XGBoost | Viscosity (Pa.S) | 1.7879 | 2.2275 | −1.3455 | 106 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mashaan, N.S.; Chamlagai, T. Application of Plastic Waste as a Sustainable Bitumen Mixture—A Review. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12761. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312761

Mashaan NS, Chamlagai T. Application of Plastic Waste as a Sustainable Bitumen Mixture—A Review. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12761. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312761

Chicago/Turabian StyleMashaan, Nuha S., and Thakur Chamlagai. 2025. "Application of Plastic Waste as a Sustainable Bitumen Mixture—A Review" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12761. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312761

APA StyleMashaan, N. S., & Chamlagai, T. (2025). Application of Plastic Waste as a Sustainable Bitumen Mixture—A Review. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12761. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312761