Intelligent Identification of Embankment Termite Nest Hidden Danger by Electrical Resistivity Tomography

Abstract

1. Introduction

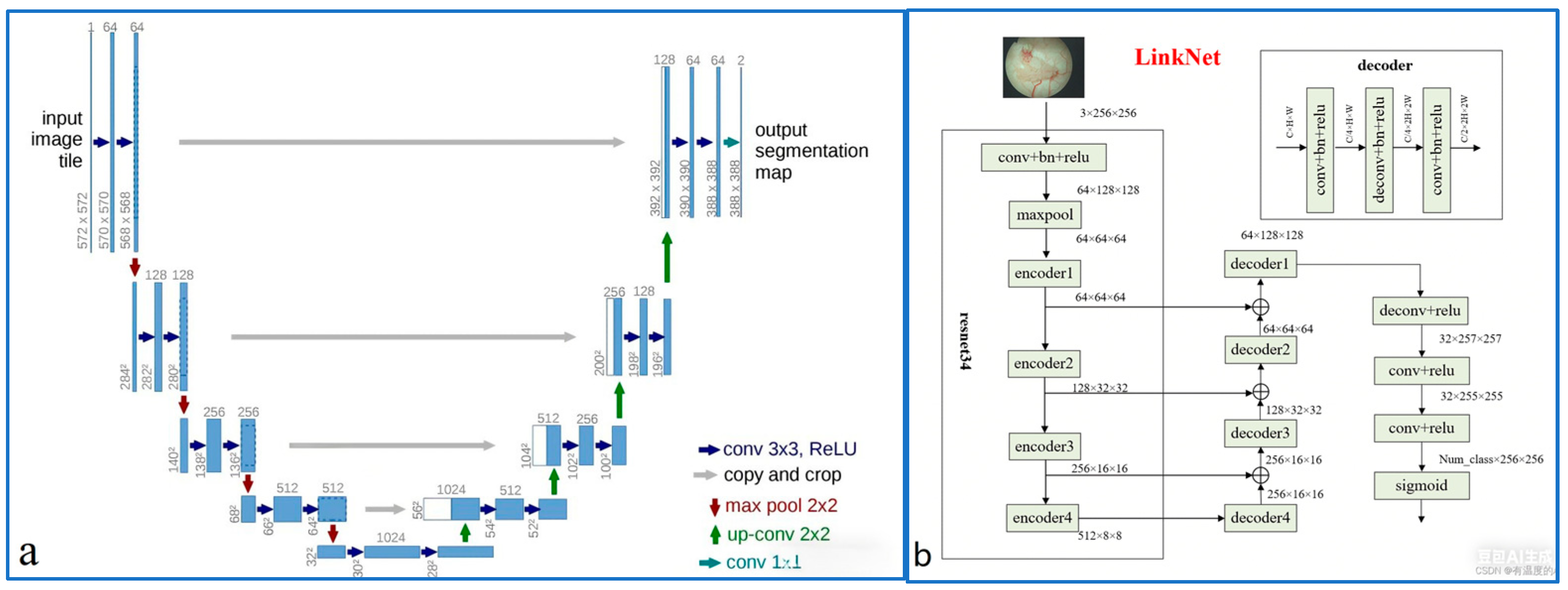

2. Basic Principle of Classical Segmentation Network

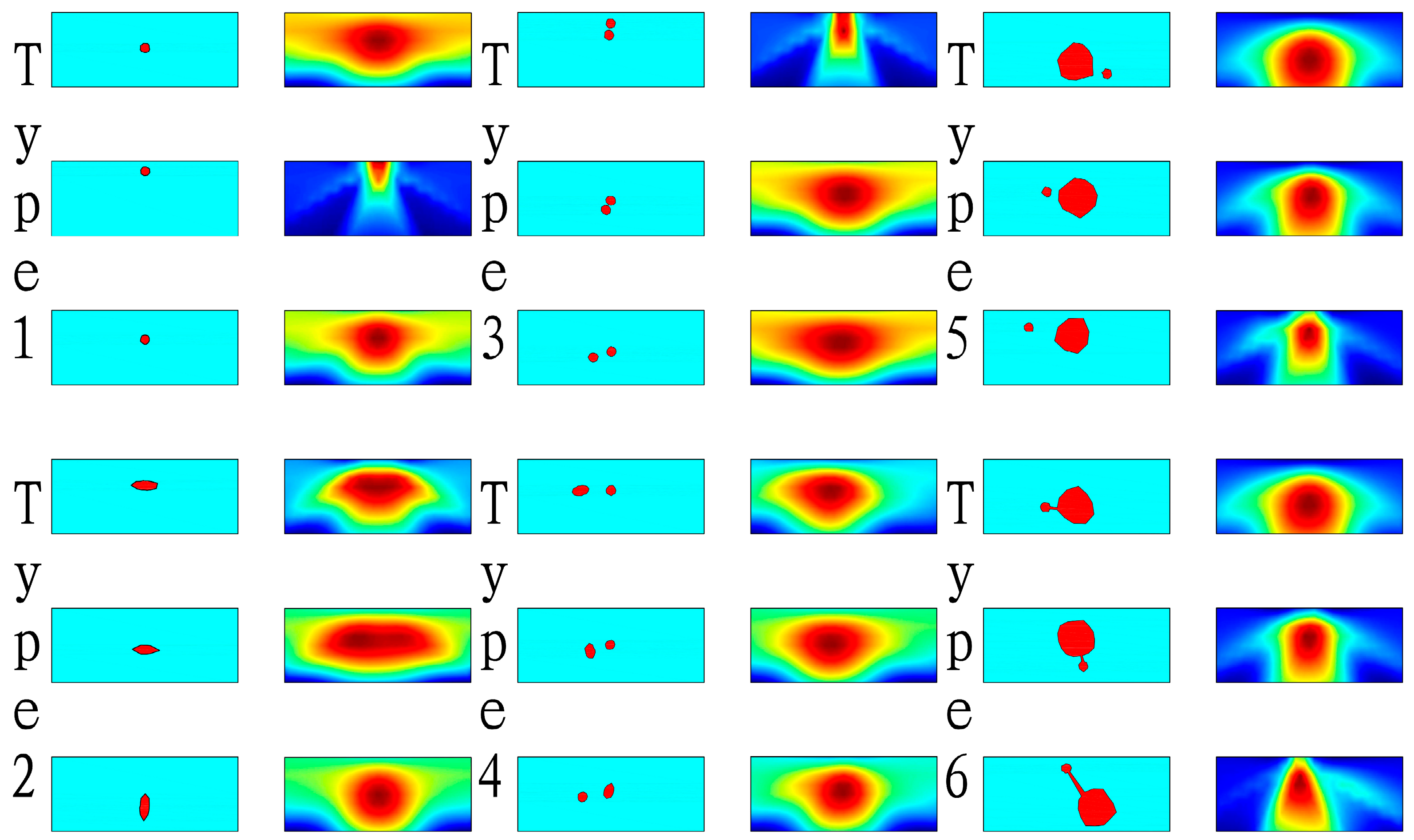

3. Improved Design of Network Architecture for ERT Inversion

3.1. The Expansion Method of Dataset

3.2. Intelligent Termite Nest Recognition Network Architecture

3.2.1. The Introduction of Attention Mechanism

3.2.2. Optimization of Loss Function

4. Improved Network Architecture for ERT Inversion

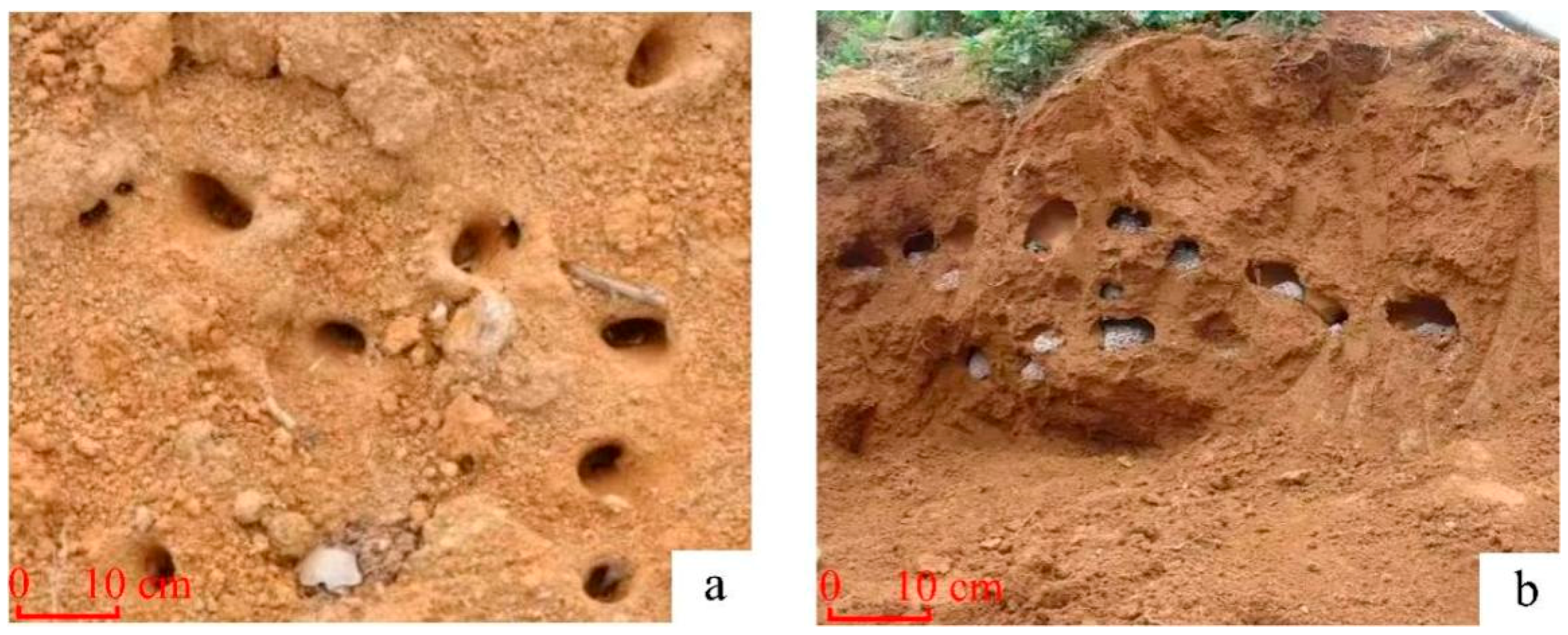

4.1. Construction of Dataset of Embankment Termite Nest Hidden Danger Model

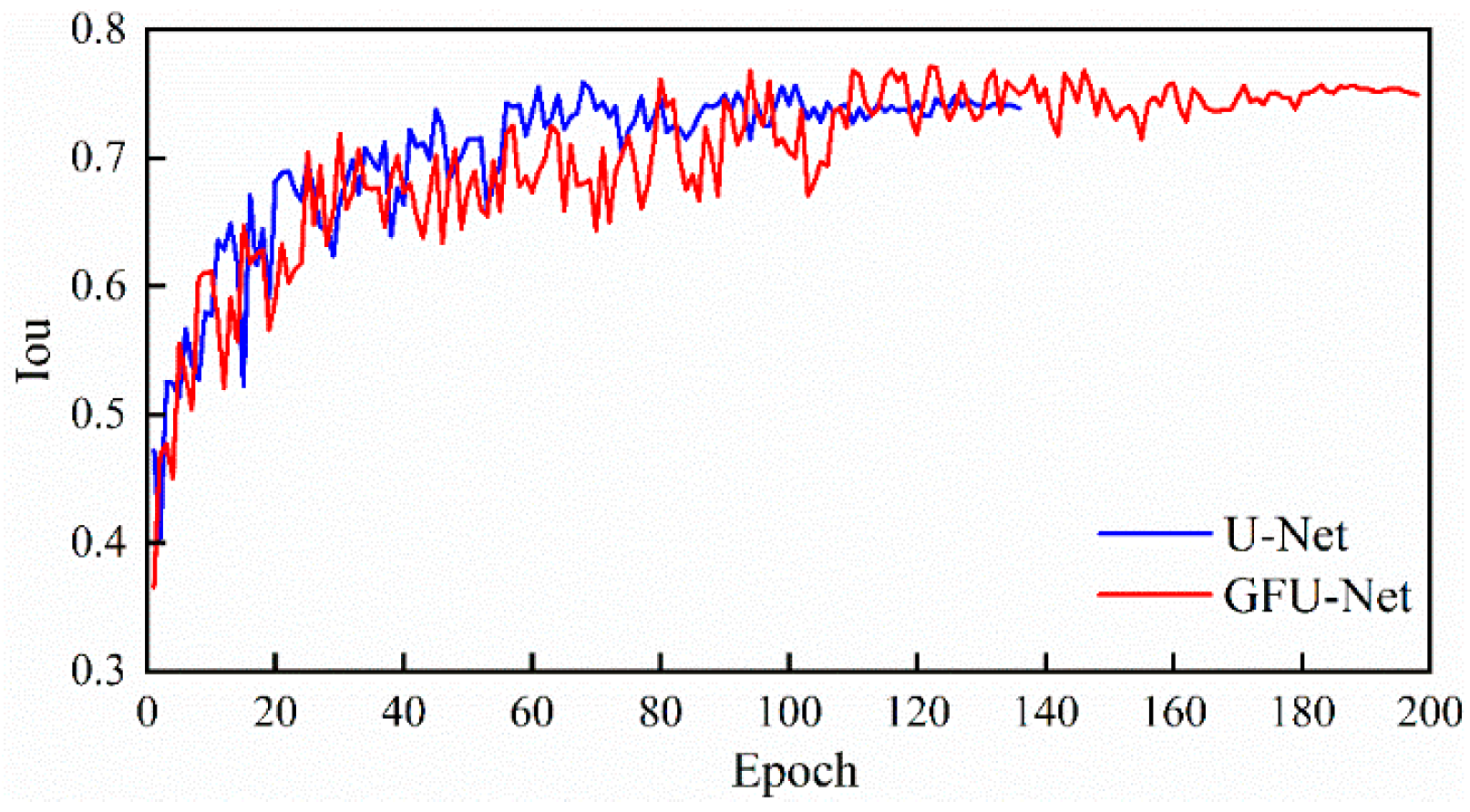

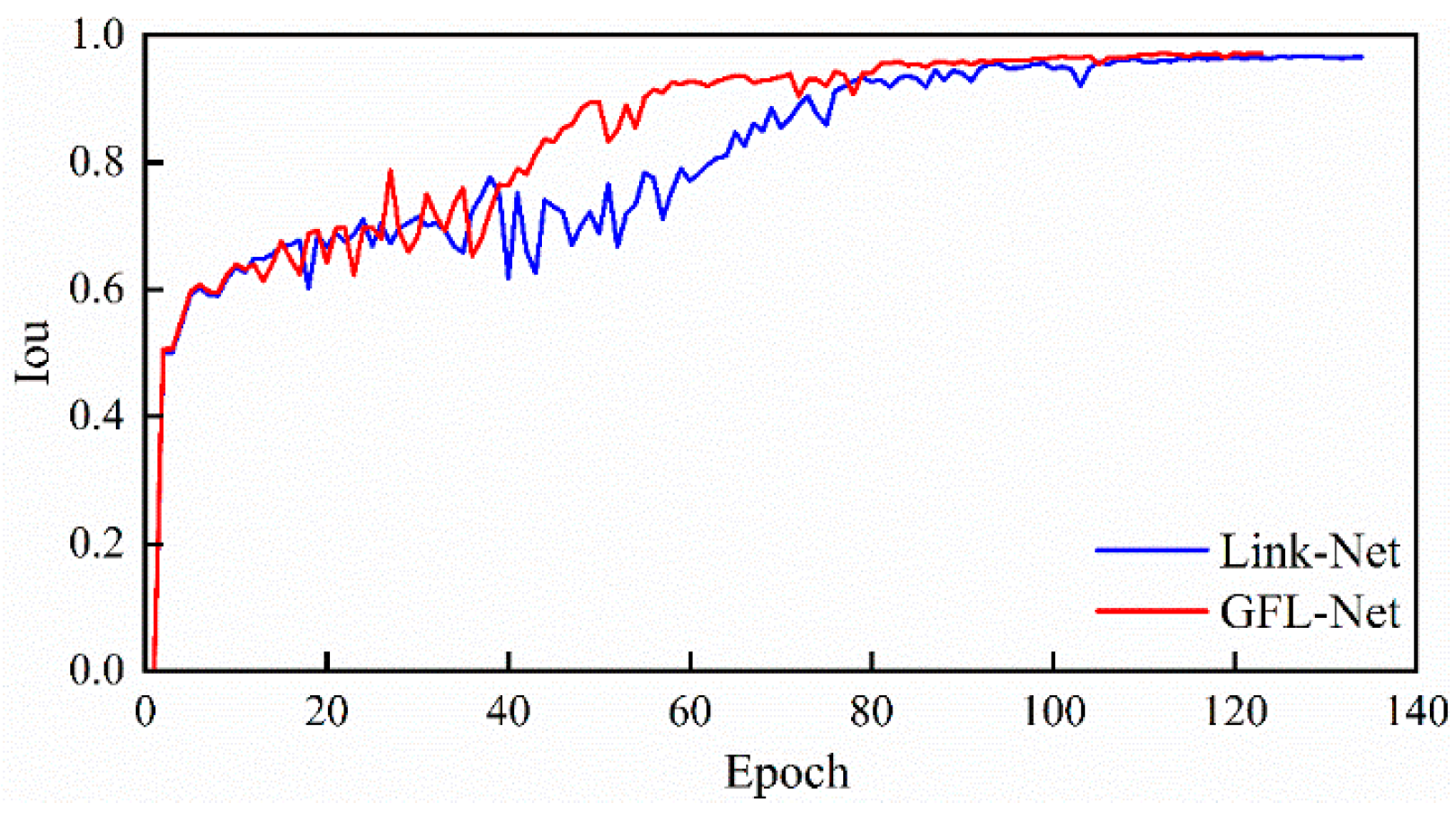

4.2. Model Training and Testing

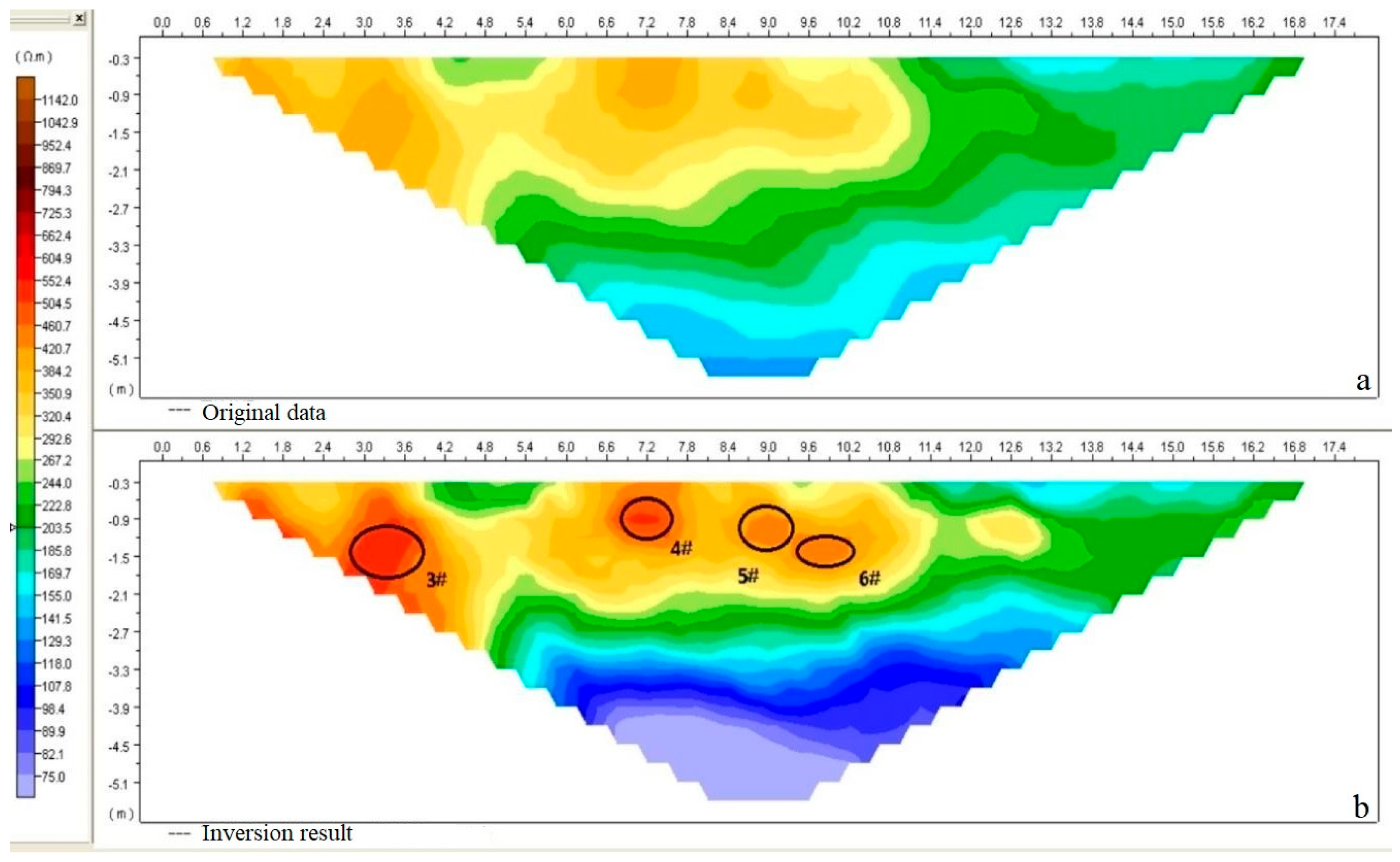

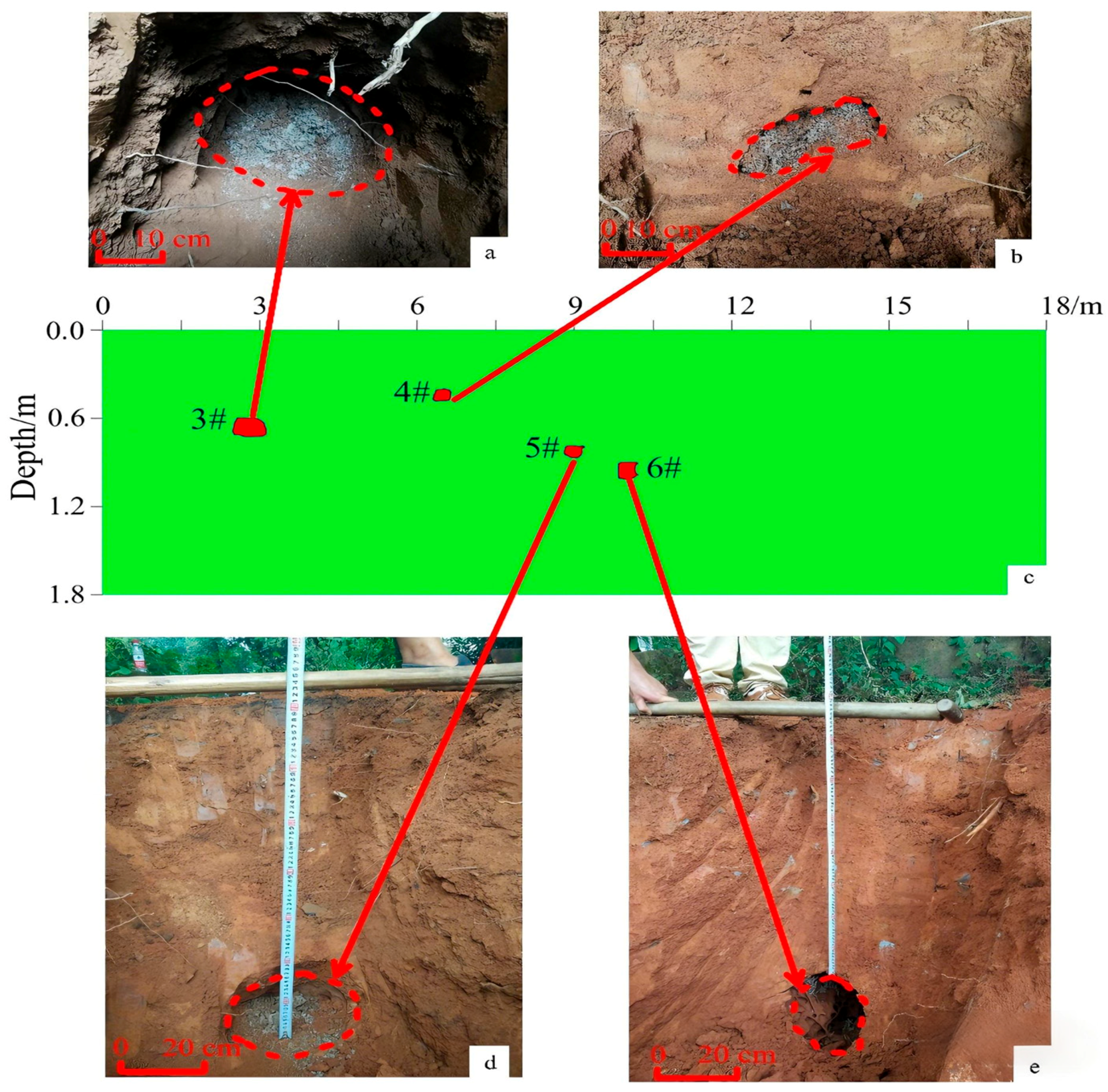

5. Validation with Field Data

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kim, S.; Kim, J. Estimation of the Damage Risk Range and Activity Period of Termites (Reticulitermes speratus) in Korean Wooden Architectural Heritage Building Sites. Forests 2024, 15, 602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuswanto, E.; Ahmad, I.; Dungani, R. Threat of Subterranean Termites Attack in the Asian Countries and their Control: A Review. Asian J. Appl. Sci. 2015, 8, 227–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Ke, Y.; Zhuang, T.; Wang, C.; Li, M.; Liu, R.; Mao, W.; Zhang, S.; Li, D. A review of the research on dike-infesting termites in China (Isoptera: Termitidae). Sociobiology 2008, 52, 751–760. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan, B.; Nanda, M.A. Detection and monitoring techniques of termites in buildings: A review. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2024, 195, 105890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, J.; Gong, Y.; Lu, W.; Lei, A.; Sun, W.; Mo, J. Control of dam termites with a monitor-controlling device (Isoptera: Termitidae). Sociobiology 2007, 50, 399–407. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Henderson, G.; Mao, L.; Evans, A. Application of Ground Penetrating Radar in Detecting the Hazards and Risks of Termites and Ants in Soil Levees. Environ. Entomol. 2009, 38, 1241–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shima, H.; Sakayama, T. Resistivity tomography: An approach to 2-D resistivity inverse problems. In SEG Technical Program Expanded Abstracts 1987; Society of Exploration Geophysicists: Houston, TX, USA, 1987; pp. 59–61. [Google Scholar]

- Espin, A.; Reyes, M.; Gil, A. Characterisation of the Historical Heritage of Murcia Using Non-Destructive Geophysical Methods. Geoheritage 2025, 17, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Dai, Q.; Liu, S.; Liu, Y. 2D Inversion of DC Resistivity Method to Detect High-resistivity Targets inside Dams. J. Environ. Eng. Geophys. 2023, 28, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Shao, S.; Jia, C.; Kong, K. Unraveling the influence of paleochannels in coastal environments vulnerable to saltwater intrusion: A synergistic approach of electrical resistivity tomography and groundwater modeling. J. Hydrol. 2025, 660, 133500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, J.E.; Wilkinson, P.B.; Gunn, D.A.; Meldrum, P.I.; Haslam, E.; Holyoake, S.; Kirkham, M. Electrical resistivity tomography applied to geologic, hydrogeologic, and engineering investigations at a former waste-disposal site. Near Surf. Geophys. 2009, 7, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichler, A.; Bobrowsky, P.; Best, M. Three-dimensional mapping of a landslide using a multi-geophysical approach: The Quesnel Forks landslide. Landslides 2004, 1, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Över, D.; Candansayar, M.E. Enhancing DC resistivity data two-dimensional inversion result by using U-net based Deep learning- algorithm: Examples from archaegeophysical surveys. J. Appl. Geophys. 2024, 227, 105430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Guo, Q.; Li, S.; Liu, B.; Ren, Y.; Pang, Y.; Guo, X.; Liu, L.; Jiang, P. Deep Learning Inversion of Electrical Resistivity Data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 5715–5728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, S.H.Y.; Oh, J.; Yoon, D.; Ryu, D.W.; Kwon, H.S. Integrating Deep Learning and Deterministic Inversion for Enhancing Fault Detection in Electrical Resistivity Surveys. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 6250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahandari, H.; Lelièvre, P.; Farquharson, C. Forward modeling of direct-current resistivity data on unstructured grids using an adaptive mimetic finite-difference method. Geophysics 2023, 88, E123–E134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Sun, Y. Fictitious Point Technique Based on Finite-Difference Method for 2.5D Direct-Current Resistivity Forward Problem. Mathematics 2024, 12, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, T.; Li, Q.; Lu, H.; Cheng, Q.; Zhang, X. GAN review: Models and medical image fusion applications. Inf. Fusion 2023, 91, 134–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, M.; Xu, T.; Liu, J.; Liu, Z.; Jiang, P.; Mu, T.; Zhang, S.; Martin, R.; Cheng, M.; Hu, S. Attention mechanisms in computer vision: A survey. Comput. Vis. Media 2022, 8, 331–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Chen, J.; Ng, M.; Huang, R.; Li, Y.; Li, C.; Yang, X.; Martel, A. Loss odyssey in medical image segmentation. Med. Image Anal. 2021, 71, 102035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iiduka, H. Appropriate Learning Rates of Adaptive Learning Rate Optimization Algorithms for Training Deep Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2022, 52, 13250–13261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prechelt, L. Automatic early stopping using cross validation: Quantifying the criteria. Neural Netw. 1998, 11, 761–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, N.; Paheding, S.; Elkin, C.; Devabhaktuni, V. U-Net and Its Variants for Medical Image Segmentation: A Review of Theory and Applications. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 82031–82057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Seo, J.; Jeon, T. NL-LinkNet: Toward Lighter but More Accurate Road Extraction with Nonlocal Operations. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. A hybrid SMOTE and Trans-CWGAN for data imbalance in real operational AHU AFDD: A case study of an auditorium building. Energy Build. 2025, 348, 116447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Evaluating cross-building transferability of attention-based automated fault detection and diagnosis for air handling units: Auditorium and hospital case study. Build Environ. 2025, 287, 113889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, J.; Menze, B. Generalisable Cardiac Structure Segmentation via Attentional and Stacked Image Adaptation. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 18th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Nice, France, 13–16 April 2021; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, C.; Li, Y.; Wang, X. AUTL: An Attention U-Net Transfer Learning Inversion Framework for Magnetotelluric Data. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petr, H.; Stefania, T.; Jan, H.; David, H. Binary cross-entropy with dynamical clipping. Neural. Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 12029–12041. [Google Scholar]

- Yeung, M.; Sala, E.; Schönlieb, C.; Rundo, L. Unified Focal loss: Generalising Dice and cross entropy-based losses to handle class imbalanced medical image segmentation. Comput. Med. Imaging Graph. 2022, 95, 102026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Hyperparameter Name | Setting Value |

|---|---|

| Batch size | 4 |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Learning rate | Dynamically adjusted |

| Epochs | 400 |

| Generator loss | BCE + Focal |

| Discriminator loss | Focal |

| Network Type | mIoU | Dice | BPA | Epochs | Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-Net | 74.2135% | 84.3730% | 96.0122% | 136 | 9.5 h |

| GFU-Net | 74.3614% | 84.4661% | 96.4980% | 198 | 16.4 h |

| Link-Net | 96.5870% | 98.1596% | 99.3094% | 134 | 5.7 h |

| GFL-Net | 97.6838% | 98.6582% | 99.6579% | 123 | 5.5 h |

| Model ID | Area Error | Centroid Distance Error (m) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U-Net | GFU-Net | Link-Net | GFL-Net | U-Net | GFU-Net | Link-Net | GFL-Net | |

| TYPE 1 | 40.29% | 39.38% | 0.47% | 0.35% | 0.279 | 0.274 | 0.028 | 0.009 |

| TYPE 2 | 20.16% | 15.37% | 5.66% | 3.51% | 0.314 | 0.307 | 0.056 | 0.022 |

| TYPE 4 | 42.37% | 36.13% | 2.01% | 1.69% | 0.279 | 0.299 | 0.032 | 0.030 |

| TYPE 5 | 9.00% | 8.55% | 3.08% | 1.58% | 0.016 | 0.072 | 0.046 | 0.011 |

| TYPE 6 | 1.19% | 4.21% | 3.23% | 3.22% | 0.063 | 0.031 | 0.015 | 0.007 |

| TYPE 7 | 26.91% | 23.69% | 23.98% | 21.29% | 0.153 | 0.144 | 0.139 | 0.126 |

| Mean Error | 22.87% | 20.39% | 6.30% | 5.02% | 0.202 | 0.204 | 0.053 | 0.032 |

| Termite Nest Number | Excavation Results (Horizontal Center/m, Top Burial Depth/m) | Inferred Location | Horizontal Center Error (%) | Top Burial Depth Error | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFL-Net | LS | GFL-Net | LS | GFL-Net | LS | ||

| 3# | (3.0, 0.55) | (2.8, 0.60) | (3.3, 1.00) | 6.667% | 10.000% | 9.091% | 81.818% |

| 4# | (7.0, 0.45) | (6.5, 0.40) | (7.2, 0.57) | 7.143% | 2.857% | 11.111% | 26.667% |

| 5# | (9.0, 0.75) | (9.1, 0.78) | (8.7, 0.70) | 1.111% | 3.333% | 4.000% | 6.667% |

| 6# | (10.5, 0.78) | (10.0, 0.90) | (9.7, 1.22) | 4.762% | 7.619% | 15.385% | 56.410% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jiang, F.; Lei, Y.; Qiao, P.; Gao, L.; Ni, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, S. Intelligent Identification of Embankment Termite Nest Hidden Danger by Electrical Resistivity Tomography. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12763. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312763

Jiang F, Lei Y, Qiao P, Gao L, Ni J, Xu X, Zhang S. Intelligent Identification of Embankment Termite Nest Hidden Danger by Electrical Resistivity Tomography. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12763. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312763

Chicago/Turabian StyleJiang, Fuyu, Yao Lei, Peixuan Qiao, Likun Gao, Jiong Ni, Xiaoyu Xu, and Sheng Zhang. 2025. "Intelligent Identification of Embankment Termite Nest Hidden Danger by Electrical Resistivity Tomography" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12763. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312763

APA StyleJiang, F., Lei, Y., Qiao, P., Gao, L., Ni, J., Xu, X., & Zhang, S. (2025). Intelligent Identification of Embankment Termite Nest Hidden Danger by Electrical Resistivity Tomography. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12763. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312763