New Molecular Materials for Direct Air Capture of Carbon Dioxide Using Electro-Swing Chemistry

Featured Application

Abstract

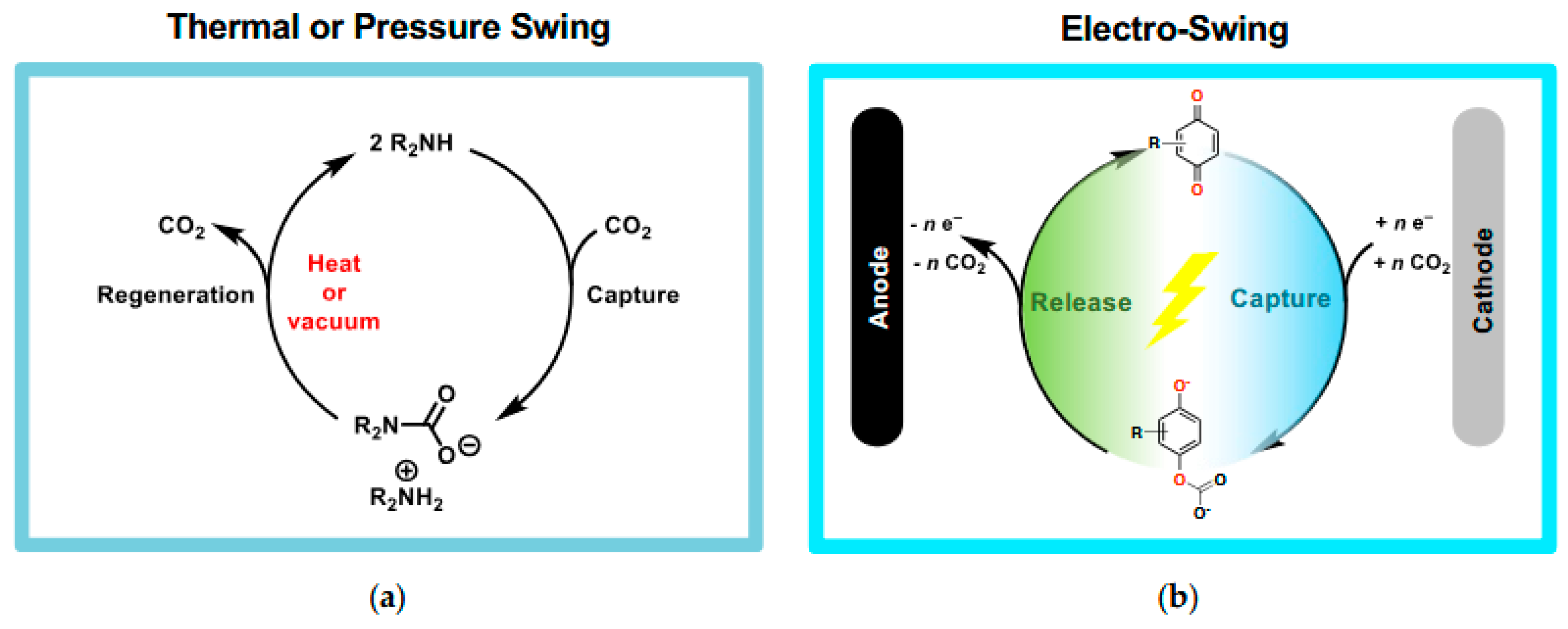

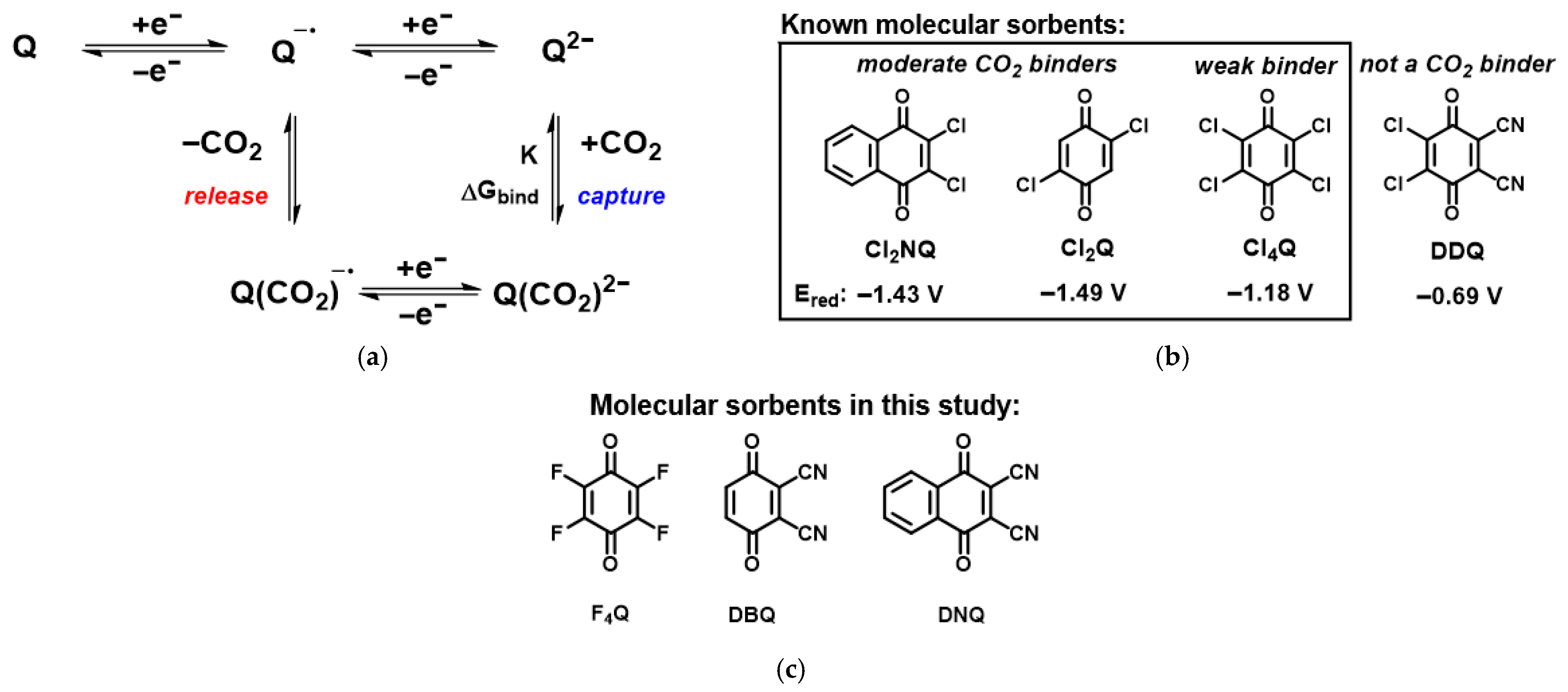

1. Introduction

2. Molecular Design of New Materials

3. Materials and Methods

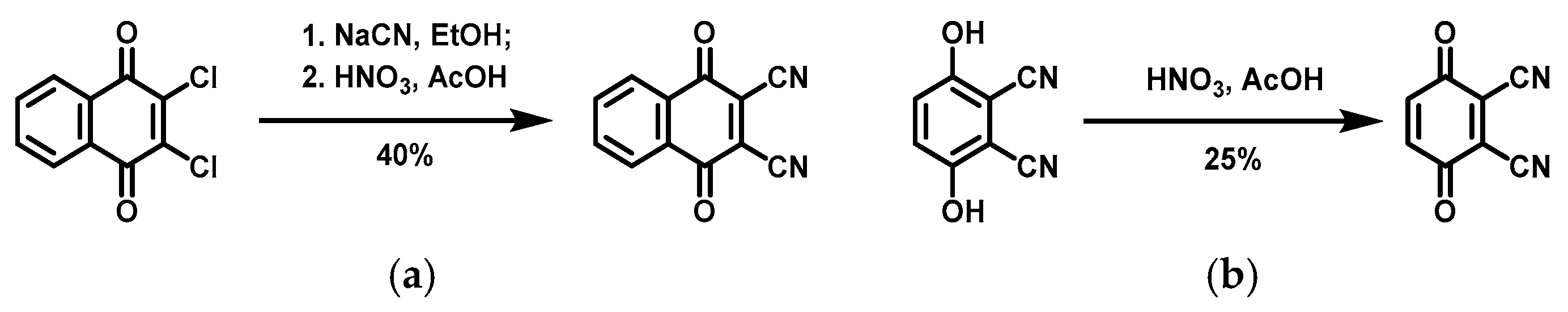

3.1. Synthesis of DNQ and DBQ

3.2. Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) Measurements [20]

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Preparation of Three Designed Quinones

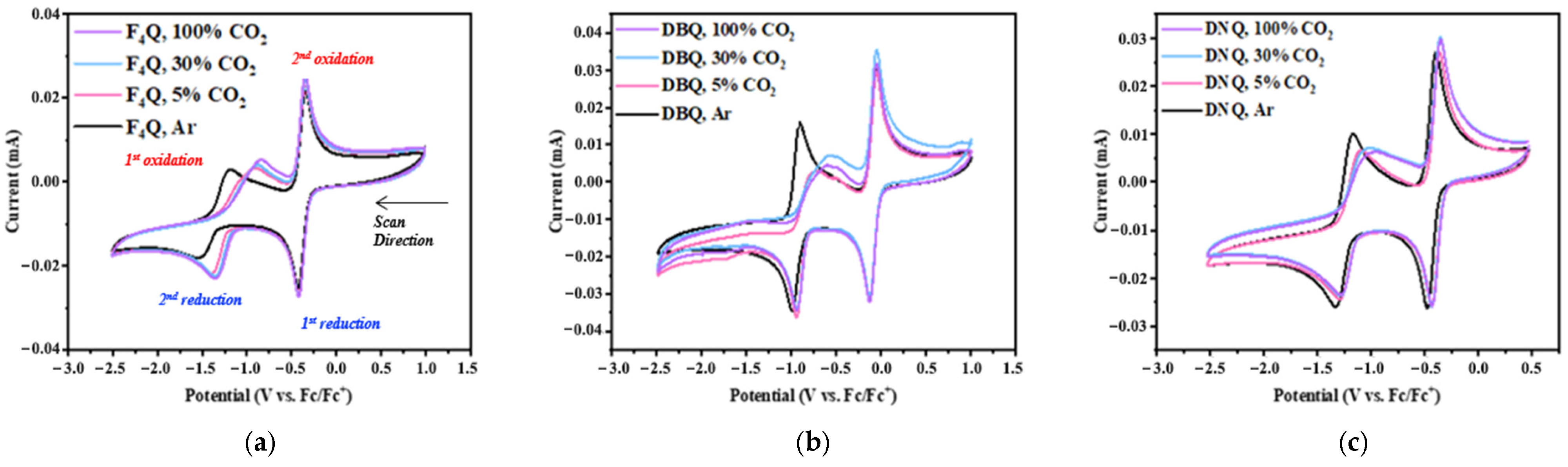

4.2. Cyclic Voltammetry Studies of Three Designed Quinones

4.3. Calculation of the Reduction Potentials and CO2 Binding Affinity of Three Quinones

4.4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ΔGbind | CO2 binding free energy |

| CCUS | Carbon capture, utilization, and storage |

| Cl2NQ | 2,3-Dichloro-1,4-naphthoquinone |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| [CO2] | Carbon dioxide concentration |

| Cl2Q | 2,3-Dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone |

| Cl4Q | 2,3,5,6-Tetrachloro-1,4-benzoquinone |

| CV | Cyclic voltammetry |

| DAC | Direct air capture |

| DBQ | 2,3-Dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone |

| DDQ | 2,3-Dichloro-5,6-dicyano-1,4-benzoquinone |

| DNQ | 2,3-Dicyano-1,4-naphthoquinone |

| E | Reduction potential |

| F4Q | 2,3,5,6-Tetrafluorobenzoquinone |

| NCAR | National Center for Atmospheric Research |

| K | Equilibrium constant |

| Q | Quinone |

References

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Synthesis Report. In Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pachauri, R.K., Meyer, L., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Tans, P.; Keeling, R. Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide. NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory. Available online: https://gml.noaa.gov/ccgg/trends/ (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- IPCC. Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5 °C; Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 677, p. 393. [Google Scholar]

- Hsiang, S.; Kopp, R.; Jina, A.; Rising, J.; Delgado, M.; Mohan, S.; Rasmussen, D.J.; Muir-Wood, R.; Wilson, P.; Oppenheimer, M.; et al. Estimating Economic Damage from Climate Change in the United States. Science 2017, 356, 1362–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, S.; Plattner, G.-K.; Knutti, R.; Friedlingstein, P. Irreversible Climate Change Due to Carbon Dioxide Emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 1704–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikkelsen, M.; Jørgensen, M.; Krebs, F.C. The teraton challenge. A Review of Fixation and Transformation of Carbon Dioxide. Energy Environ. Sci. 2010, 3, 43–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, B.; Stern, L.N.; Oam, J.H. The Global Status of CCS 2020: Vital to Achieve Net Zero. 2020. Available online: http://www.globalccsinstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/Global-Status-of-CCS-Report-English.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Cresko, J.; Elliott, W.; Nimbalkar, S.; Wenning, T.; Zaltash, A.; Quinn, J.L.; Kuehn, S.D.L. US Department of Energy’s Industrial Decarbonization Roadmap. No. DOE/EE-2635. USDOE Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy (EERE). 2022. Available online: https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/1961393 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Hack, J.; Maeda, N.; Meier, D.M. Review on CO2 Capture Using Amine-Functionalized Materials. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 39520–39530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keith, D.W.; Holmes, G.; St. Angelo, D.; Heidel, K. A Process for Capturing CO2 from the Atmosphere. Joule 2018, 2, 1573–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQueen, N.; Ghoussoub, M.; Mills, J.; Scholten, M. A Scalable Direct Air Capture Process Based on Accelerated Weathering of Calcium Hydroxide. Heirloom Carbon Technol. 2022, 1–9. Available online: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:248119333 (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Sanz-Perez, E.S.; Murdock‚, C.R.; Didas, S.A.; Jones, C.W. Direct Capture of CO2 from Ambient Air. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 11840–11876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beuttler, C.; Charles, L.; Wurzbacher, J. The Role of Direct Air Capture in Mitigation of Anthropogenic Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Front. Clim. 2019, 1, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voskian, S.; Hatton, T.A. Faradaic Electro-swing Reactive Adsorption for CO2 Capture. Energy Environ. Sci. 2019, 12, 3530–3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlow, J.M.; Yang, J.Y. Oxygen-Stable Electrochemical CO2 Capture and Concentration with Quinones Using Alcohol Additives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144, 14161–14169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massen-Hane, M.; Diederichsen, K.M.; Hatton, T.A. Engineering Redox-active Electrochemically Mediated Carbon Dioxide Capture Systems. Nat. Chem. Eng. 2024, 1, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, L.; Mathur, A.; Xu, Y.; Fang, Z.; Gu, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y. Redox-tunable Isoindigos for Electrochemically Mediated Carbon Capture. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, H.A.; Luca, O.R. Application-Specific Thermodynamic Favorability Zones for Direct Air Capture of Carbon Dioxide. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2021, 23, 12533–12536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petersen, H.A. Molecular and Energetic Tuning of Electrochemical Carbon Capture Technologies. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alherz, A.W.; Petersen, H.A.; Singstock, N.R.; Sur, S.N.; Musgrave, C.B.; Luca, O.R. Predictive Energetic Tuning of Quinoid O-nucleophiles for the Electrochemical Capture of Carbon Dioxide. Energy Adv. 2022, 1, 900–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, P. Naphthoquinones as Covalent Reversible Inhibitors of Cysteine Proteases—Studies on Inhibition Mechanism and Kinetics. Molecules 2020, 25, 2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, G.R.; Guan, Z.; He, Y.H. Synthesis of Six-membered Functionalized Carbocyclic Compounds by One-pot Reaction of Hydroquinone Derivatives and Dienes. Synth. Commun. 2011, 41, 3016–3025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zito, A.M.; Bím, D.; Vargas, S.; Alexandrova, A.N.; Yang, J.Y. Computational and Experimental Design of Quinones for Electrochemical CO2 Capture and Concentration. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2022, 1, 11387–11395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCAR/EOL. NCAR Foothills Lab Weather. National Center for Atmospheric Research. 2024. Available online: https://archive.eol.ucar.edu/cgi-bin/weather.cgi (accessed on 24 November 2025).

- Smith, S.; Geden, O.; Gidden, M.J.; Lamb, W.F.; Nemet, G.F.; Minx, J.C.; Buck, H.; Burke, J.; Cox, E.; Edwards, M.R.; et al. The State of Carbon Dioxide Removal: A Global, Independent Scientific Assessment of Carbon Dioxide Removal, 2nd ed.; The State of Carbon Dioxide Removal: Oxford, UK, 2024; Available online: https://www.stateofcdr.org/s/The-State-of-Carbon-Dioxide-Removal-2Edition.pdf (accessed on 24 November 2025).

| Sorbent | Temperature (K) | [CO2] (%) | [CO2] (M) | E2,red a (V) | E2,ox a (V) | E2,1/2 a (V) | ΔE1/2 a (V) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F4Q | 296 | 0 | 0.000 | −1.338 | −1.162 | −1.250 | 0.000 |

| 5 | 0.011 | −1.297 | −1.088 | −1.193 | 0.058 | ||

| 30 | 0.070 | −1.288 | −1.041 | −1.165 | 0.086 | ||

| 100 | 0.233 | −1.288 | −1.005 | −1.147 | 0.104 | ||

| DBQ | 295 | 0 | 0.000 | −0.903 | −0.966 | −0.935 | 0.000 |

| 5 | 0.012 | −0.943 | −0.737 | −0.840 | 0.095 | ||

| 30 | 0.072 | −0.942 | −0.580 | −0.761 | 0.174 | ||

| 100 | 0.239 | −0.935 | −0.601 | −0.768 | 0.167 | ||

| DNQ | 294 | 0 | 0.000 | −1.532 | −1.200 | −1.366 | 0.000 |

| 5 | 0.012 | −1.405 | −0.904 | −1.155 | 0.212 | ||

| 30 | 0.074 | −1.331 | −0.893 | −1.112 | 0.254 | ||

| 100 | 0.245 | −1.350 | −0.840 | −1.095 | 0.271 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Z.; Koltunski, H.J.; Luca, O.R. New Molecular Materials for Direct Air Capture of Carbon Dioxide Using Electro-Swing Chemistry. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12739. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312739

Wang Z, Koltunski HJ, Luca OR. New Molecular Materials for Direct Air Capture of Carbon Dioxide Using Electro-Swing Chemistry. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12739. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312739

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Zoe, Hunter J. Koltunski, and Oana R. Luca. 2025. "New Molecular Materials for Direct Air Capture of Carbon Dioxide Using Electro-Swing Chemistry" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12739. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312739

APA StyleWang, Z., Koltunski, H. J., & Luca, O. R. (2025). New Molecular Materials for Direct Air Capture of Carbon Dioxide Using Electro-Swing Chemistry. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12739. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312739