How Many Trials Are Needed for Consistent Clinical Gait Assessment?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

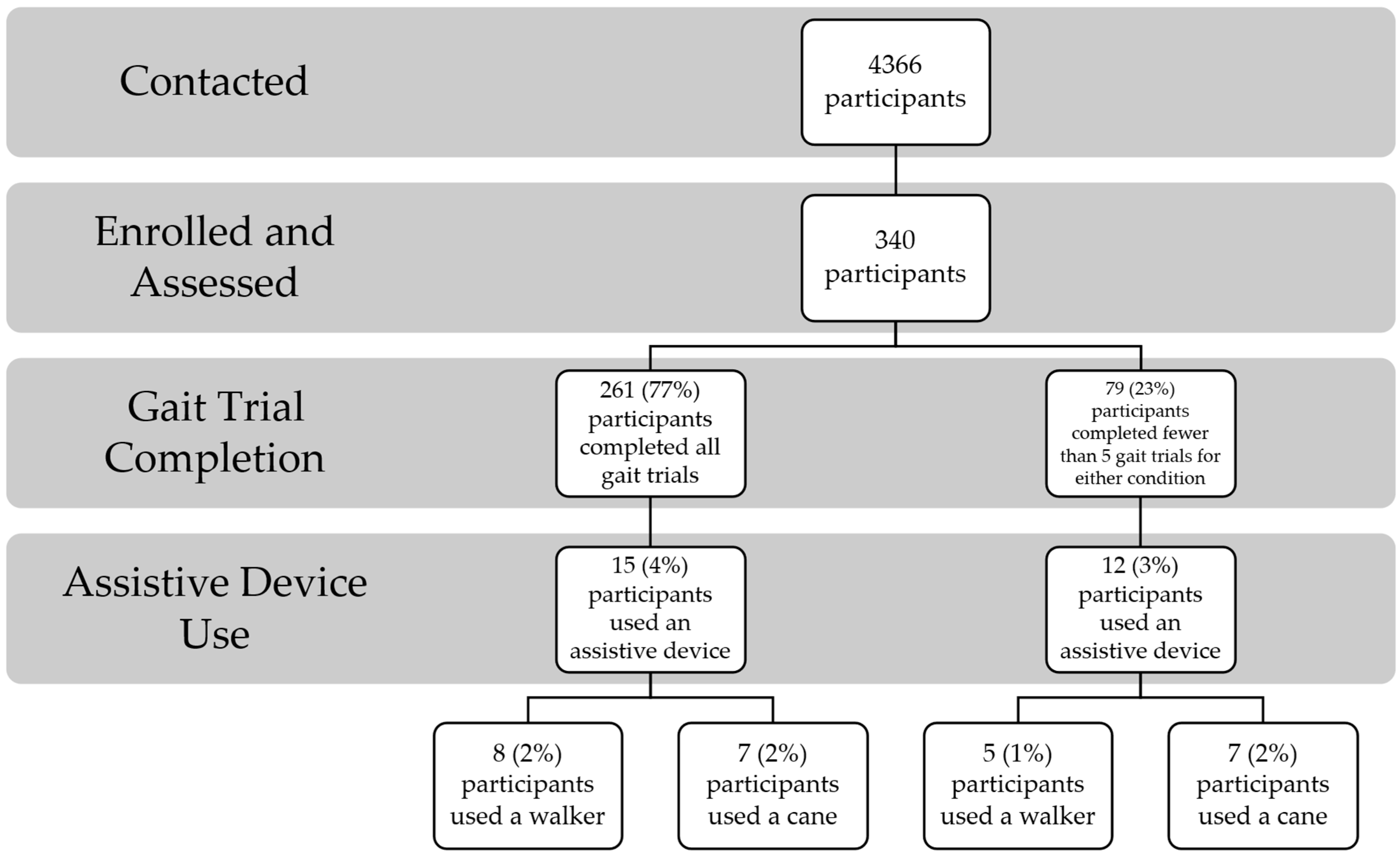

2.1. Participants

2.2. Procedures

2.3. Data Processing

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Limitations

4.2. Generalizability

4.3. Feasibility and Clinical Implementation

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ota, M.; Tateuchi, H.; Hashiguchi, T.; Ichihashi, N. Verification of validity of gait analysis systems during treadmill walking and running using human pose tracking algorithm. Gait Posture 2021, 85, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, J.; Atalaia, T.; Abrantes, J.; Aleixo, P. Gait biomechanical parameters related to falls in the elderly: A systematic review. Biomechanics 2024, 4, 165–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willwacher, S.; Kurz, M.; Robbin, J.; Thelen, M.; Hamill, J.; Kelly, L.; Mai, P. Running-related biomechanical risk factors for overuse injuries in distance runners: A systematic review considering injury specificity and the potentials for future research. Sports Med. 2022, 52, 1863–1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McAllister, M.J.; Chen, A.; Selinger, J.C. Behavioural energetics in human locomotion: How energy use influences how we move. J. Exp. Biol. 2025, 228, JEB248125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, A.; Fritz, S.L.; Lusardi, M. Walking speed: The functional vital sign. J. Aging Phys. Act. 2015, 23, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Studenski, S. Bradypedia: Is gait speed ready for clinical use? J. Nutr. Health Aging 2009, 13, 878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehmet, H.; Robinson, S.R.; Yang, A.W.H. Assessment of gait speed in older adults. J. Geriatr. Phys. Ther. 2020, 43, 42–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpman, C.; LeBrasseur, N.K.; DePew, Z.S.; Novotny, P.J.; Benzo, R.P. Measuring gait speed in the out-patient clinic: Methodology and feasibility. Respir. Care 2014, 59, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, J.E.; Ostir, G.V.; Fisher, S.R.; Ottenbacher, K.J. Assessing walking speed in clinical research: A systematic review. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2008, 14, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.; Sung, J.; An, R.; Hernandez, M.E.; Sosnoff, J.J. Gait variability in people with neurological disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2016, 47, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R.W.; Glenney, S.S. Minimal clinically important difference for change in comfortable gait speed of adults with pathology: A systematic review. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2014, 20, 295–300. [Google Scholar]

- Peel, N.M.; Kuys, S.S.; Klein, K. Gait speed as a measure in geriatric assessment in clinical settings: A systematic review. J. Gerontol. Ser. A Biomed. Sci. Med. Sci. 2013, 68, 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Leech, K.A.; Roemmich, R.T.; Gordon, J.; Reisman, D.S.; Cherry-Allen, K.M. Updates in motor learning: Implications for physical therapist practice and education. Phys. Ther. 2022, 102, pzab250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luft, A.R.; Buitrago, M.M. Stages of motor skill learning. Mol. Neurobiol. 2005, 32, 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, P.C.R.d.; Barbieri, F.A.; Zijdewind, I.; Gobbi, L.T.B.; Lamoth, C.; Hortobágyi, T. Effects of experimentally induced fatigue on healthy older adults’ gait: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0226939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homagain, A.; Ehgoetz Martens, K.A. Emotional states affect steady state walking performance. PloS One 2023, 18, e0284308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Fleiss, J.L. Intraclass correlations: Uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol. Bull. 1979, 86, 420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, J.P. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J. Strength Cond. Res. 2005, 19, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stebbins, J.; Harrington, M.; Stewart, C. Clinical gait analysis 1973–2023: Evaluating progress to guide the future. J. Biomech. 2023, 160, 111827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehdipour, A.; Malouka, S.; Beauchamp, M.; Richardson, J.; Kuspinar, A. Measurement properties of the usual and fast gait speed tests in community-dwelling older adults: A COSMIN-based systematic review. Age Ageing 2024, 53, afae055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinya, M.; Takiyama, K. Guidelines for balancing the number of trials and the number of subjects to ensure the statistical power to detect variability–implication for gait studies. J. Biomech. 2024, 165, 111995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznetsov, N.A.; Rhea, C.K. Power considerations for the application of detrended fluctuation analysis in gait variability studies. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Ivanov, P.C.; Hu, K.; Stanley, H.E. Effect of nonstationarities on detrended fluctuation analysis. Phys. Rev. E 2002, 65, 041107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirchner, M.; Schubert, P.; Liebherr, M.; Haas, C.T. Detrended fluctuation analysis and adaptive fractal analysis of stride time data in Parkinson’s disease: Stitching together short gait trials. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e85787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marmelat, V.; Reynolds, N.R.; Hellman, A. Gait dynamics in Parkinson’s disease: Short gait trials “stitched” together provide different fractal fluctuations compared to longer trials. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, M.E.; King, A.C.; Newell, K.M. Task difficulty and the time scales of warm-up and motor learning. J. Mot. Behav. 2013, 45, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipsitz, L.A.; Goldberger, A.L. Loss of ‘complexity’ and aging: Potential applications of fractals and chaos theory to senescence. JAMA J. Am. Med. Assoc. 1992, 267, 1806–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillancourt, D.E.; Newell, K. Aging and the time and frequency structure of force output variability. J. Appl. Physiol. 2003, 94, 903–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bisi, M.C.; Stagni, R. Complexity of human gait pattern at different ages assessed using multiscale entropy: From development to decline. Gait Posture 2016, 47, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

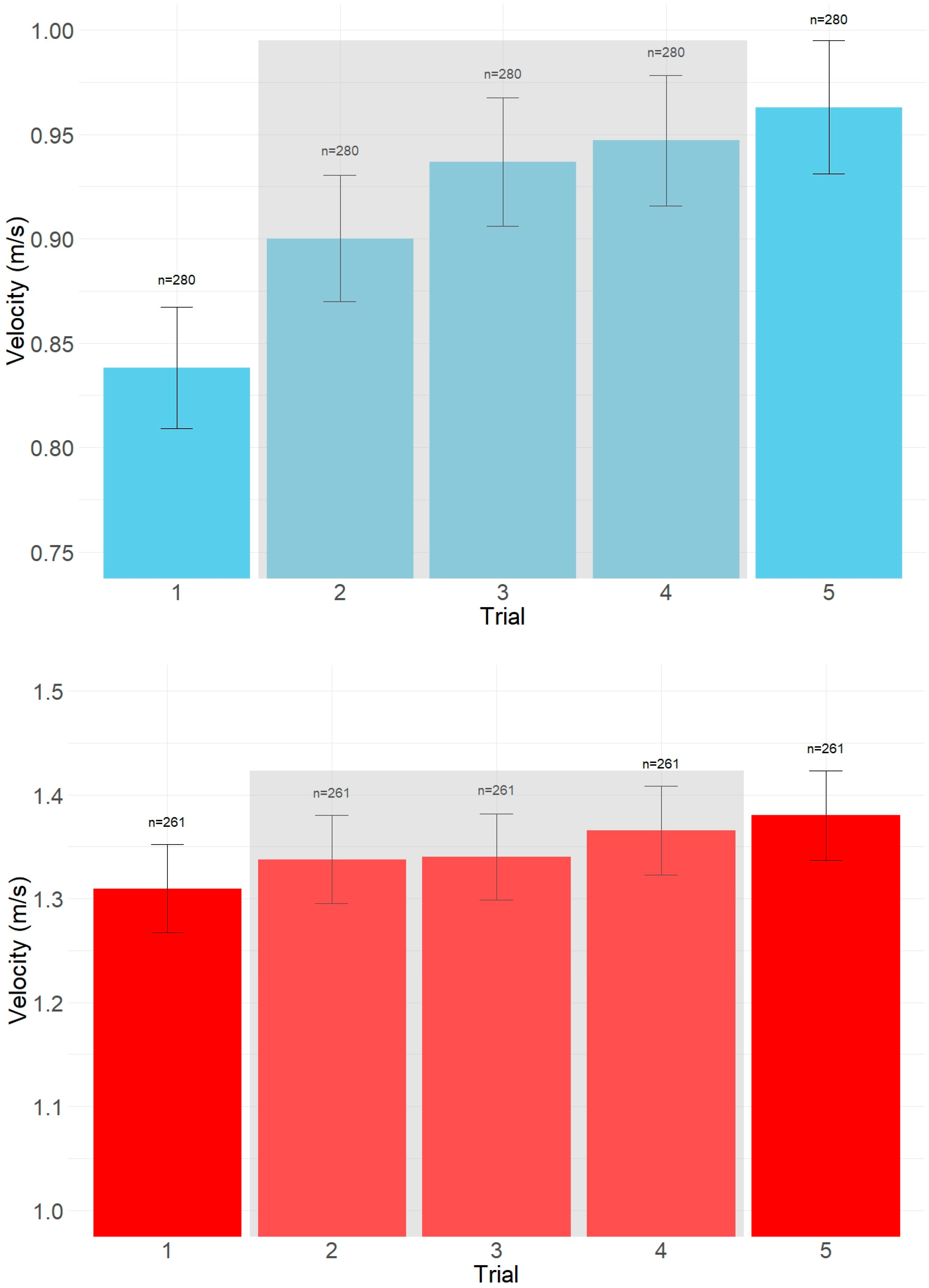

| Condition | Trial | Estimated Mean (cm/s) | SE | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred | 1 | 86.92 | 25.17 | 4.78 | 3.38 |

| 2 | 89.18 | 25.37 | 4.92 | 2.84 | |

| 3 | 90.56 | 25.58 | 5.02 | 2.51 | |

| 4 | 91.71 | 25.82 | 5.07 | 2.27 | |

| 5 | 92.80 | 26.09 | 4.09 | 2.36 | |

| Maximal | 1 | 132.38 | 34.71 | 5.83 | 4.12 |

| 2 | 132.93 | 34.39 | 5.97 | 3.45 | |

| 3 | 133.84 | 34.43 | 5.99 | 3.00 | |

| 4 | 134.67 | 34.55 | 6.03 | 2.70 | |

| 5 | 134.80 | 34.45 | 5.45 | 3.15 |

| Preferred Gait Velocity | Maximum Gait Velocity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial Average | Completers (n = 281) | Non-Completers (n = 59) | Completers (n = 261) | Non-Completers (n = 79) |

| Age (±SD) (years) | 70.83 ± 7.47 | 71.32 ± 10.64 | 70.86 ± 7.34 | 71.04 ± 10.16 |

| Sex (% female) | 62.6% | 77.3% | 62.6% | 72.9% |

| Height (±SD) (cm) | 166.64 ± 10.53 | 164.09 ± 10.48 | 166.71 ± 10.66 | 164.58 ± 10.02 |

| Number reported falls in past year (±SD) | 1.18 ± 1.21 | 1.45 ± 1.35 | 1.19 ± 1.20 | 1.38 ± 1.37 |

| Gait Speed (±SD) (m/s) | 0.93 ± 0.20 | 0.59 ± 0.25 | 1.34 ± 0.35 | 0.94 ± 0.32 |

| Number using assistive device (% of enrolled) | 20 (6%) | 8 (2%) | 13 (4%) | 15 (4%) |

| Condition | Trial | ICC(2,k) | 95% CI Lower | 95% CI Upper |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred | 1 | 0.929 | 0.850 | 0.960 |

| 2 | 0.989 | 0.984 | 0.992 | |

| 3 | 0.992 | 0.989 | 0.994 | |

| 4 | 0.991 | 0.984 | 0.994 | |

| 5 | 0.985 | 0.966 | 0.992 | |

| Maximal | 1 | 0.965 | 0.952 | 0.973 |

| 2 | 0.991 | 0.988 | 0.993 | |

| 3 | 0.992 | 0.989 | 0.994 | |

| 4 | 0.993 | 0.991 | 0.995 | |

| 5 | 0.993 | 0.990 | 0.995 |

| Condition | Trial Average | k | n | Mean Speed (cm/s) | SD_Between (cm/s) | SEM_Single | SEM_Mean | Percent_SEM | ICC_2k (ICC Lower, ICC Upper) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred | 1–2 | 2 | 280 | 86.92 | 25.17 | 4.78 | 3.38 | 3.89 | 0.953 (0.919–0.900) |

| 1–3 | 3 | 280 | 89.18 | 25.37 | 4.92 | 2.84 | 3.19 | 0.951 (0.914–0.897) | |

| 1–4 | 4 | 280 | 90.56 | 25.58 | 5.02 | 2.51 | 2.77 | 0.955 (0.921–0.906) | |

| 1–5 | 5 | 280 | 91.71 | 25.82 | 5.07 | 2.27 | 2.47 | 0.957 (0.924–0.910) | |

| Middle (2,3,4) | 3 | 280 | 92.80 | 26.09 | 4.09 | 2.36 | 2.55 | 0.983 (0.970–0.963) | |

| Maximal | 1–2 | 2 | 261 | 132.38 | 34.71 | 5.83 | 4.12 | 3.11 | 0.983 (0.970–0.962) |

| 1–3 | 3 | 261 | 132.93 | 34.39 | 5.97 | 3.45 | 2.60 | 0.988 (0.978–0.973) | |

| 1–4 | 4 | 261 | 133.84 | 34.43 | 5.99 | 3.00 | 2.24 | 0.988 (0.979–0.974) | |

| 1–5 | 5 | 261 | 134.67 | 34.55 | 6.03 | 2.70 | 2.00 | 0.988 (0.978–0.974) | |

| Middle (2,3,4) | 3 | 261 | 134.80 | 34.45 | 5.45 | 3.15 | 2.34 | 0.990 (0.982–0.977) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Howard, C.K.; Rhea, C.K.; Moxey, J.R.; Langerhans, K.; Prupetkaew, P.; Samulski, B.S. How Many Trials Are Needed for Consistent Clinical Gait Assessment? Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12740. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312740

Howard CK, Rhea CK, Moxey JR, Langerhans K, Prupetkaew P, Samulski BS. How Many Trials Are Needed for Consistent Clinical Gait Assessment? Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12740. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312740

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoward, Charlend K., Christopher K. Rhea, Jacquelyn R. Moxey, Kyle Langerhans, Paphawee Prupetkaew, and Brittany S. Samulski. 2025. "How Many Trials Are Needed for Consistent Clinical Gait Assessment?" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12740. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312740

APA StyleHoward, C. K., Rhea, C. K., Moxey, J. R., Langerhans, K., Prupetkaew, P., & Samulski, B. S. (2025). How Many Trials Are Needed for Consistent Clinical Gait Assessment? Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12740. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312740