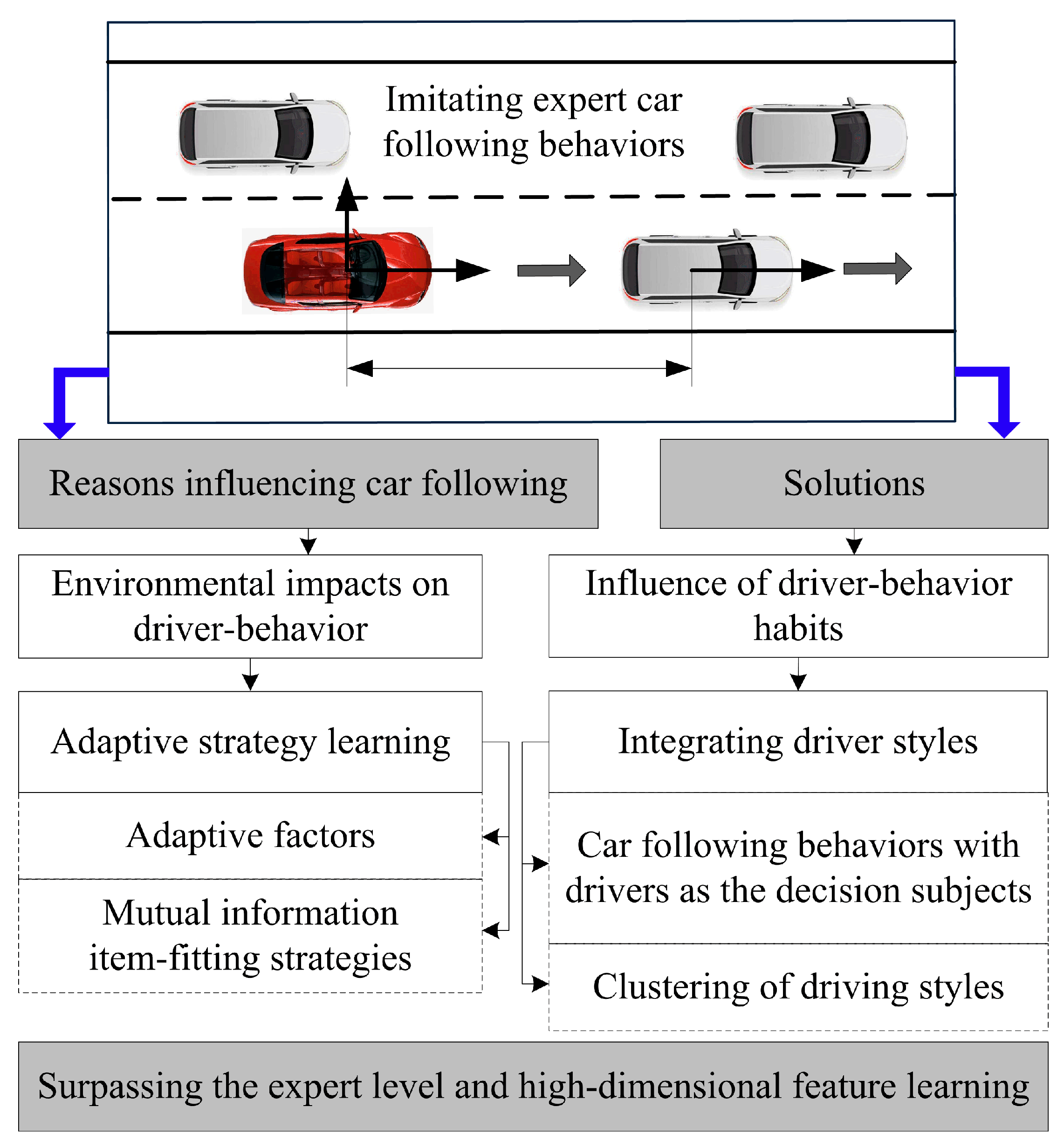

The factors that affect car following can be mainly divided into two aspects. The first is the influence of the environment itself on driver behavior, and the second is the inherent influence of individual driver behavior habits on the following strategy.

2.1. Theoretical Reference

For imitation learning methods, appropriate reward functions do not need to be manually set. Consequently, in complex and ill-defined environments, they outperform reinforcement learning methods. In actual tasks, there may be multiple intentions when drivers are following a vehicle; different drivers have different driving habits, such as aggressive and mild type, which will then lead to difficulties in choosing a reward function. To solve these problems, an adaptive learning strategy and imitation learning method was proposed, which fuses driving styles and enabled the conduction of further research and improvement.

Figure 1 illustrates the algorithm flowchart of the adaptive car-following strategy based on imitation learning in this paper.

This section proposes the following model with an adaptive factor for the inherent phenomenon of environmental influence on driver behavior. The main idea is to construct a framework of a GAN network with adaptability based on the basic principle of the GAN network: that is, instead of estimating the reward function, directly learn the strategy of the following model. The formula is as shown in (1):

where

πE is the expert strategy;

π is the strategy that needs to be learned and trained; D is used as a discriminator to distinguish state-action pairs; and

H(

π) represents causal entropy.

The adaptive strategy is model-free, but needs to be interactively trained with the environment. It treats the environment as a black box and is end-to-end differentiable. Due to internal potential variation factors such as expert level and preferences under different strategies, the generated trajectories will also have significant changes among different individuals. Even the same person when facing the same situation will make different decisions, as well, which leads to the generation of multiple different strategies. In this scenario, construct an expert strategy set: , and redefine the generation process , of expert trajectories . In this process, an adaptive parameter c is defined, and is the prior probability distribution of . The goal of this algorithm is to recover the strategy under the adaptive parameter .

In order to make the adaptive factor more closely fit with the strategy, achieve a degree of interdependence, and make the adaptive factor and the strategy have greater correlation, mutual information is added to the optimization function.

where

is the mutual information;

H(

c) is the entropy of the adaptive parameter c;

p(

c) is the prior probability distribution of the adaptive parameter

c;

π(·|

s,c) is the probability distribution of actions given the state

s and parameter

c;

τ is the expert trajectory;

p(

c|

τ) is the posterior probability distribution of c given the expert trajectory

τ; and

is the mathematical expectation.

Then add the adaptive factors to the optimization objective function to obtain

where

are the relevant parameters of the strategy to be learned;

is the discriminator parameter;

is the discriminator function with parameter

;

is the strategy to be learned; and

and

are the weight coefficients.

This can make the mixed trajectories generated by experts more clearly organized, but in the calculation process the posterior probability

is difficult to calculate. Here the Q value is directly used instead; that is

where

L1(

π,

Q) is a metric related to the policy

π and the

Q-value (since the posterior probability

p(

c|

τ) is difficult to calculate, it is used to approximate the mutual information

).

During vehicle driving, one should not only consider the influence of the driving environment on the model, but should also satisfy the comfort and safety of the driver in the car-following task. In this section, combined with vehicle dynamics itself, the car-following task will be optimized by using driver-style characteristics. Establishing a personalized car-following model requires driving data that can reflect driving styles. For this objective, the data needs to be efficiently classified in accordance with various driving styles. Combined with the inter-vehicle distance and the speed of the proxy vehicle, the reciprocal of time-to-collision (TTCI) is defined as follows:

where

represents the speed difference between the following vehicle and the leading vehicle and

represents the vehicle distance.

A method of fusing driver style into the following strategy was proposed to make the following model have personalized characteristics and improve the overall following task. This method can effectively solve the multi-objective optimization problem in the following task, mainly including the error between the actual and the expected vehicle distance, reflecting driving style; the relative speed maintaining the following behavior and with the leading vehicle; and the acceleration and deceleration for ensuring comfort. The trajectory data of different driving styles (conservative and aggressive) obtained in the previous section indicate that the differences between the two are reflected in behavioral indicators such as time interval, collision time, speed, and acceleration, which can be used to model and quantify driving styles. In typical follow-up scenarios, drivers of the same style often have similar time intervals, while drivers of different styles have significant differences. The formula for vehicle distance can be expressed as

where

is the driving speed of the following vehicle and

represents time progress. In a conservative driving style,

; in an aggressive driving style,

.

represents the safe distance when the car is driving at a very low speed.

According to the basic knowledge of the longitudinal dynamics of the front and rear vehicles, it can be deduced that

where

k represents the

-th time point;

is the sampling interval of 0.1 s;

represents the speed of the leading vehicle; and

represents the acceleration of the leading vehicle.

The goal of the vehicle following is for the driver to adjust the vehicle’s speed to that of the leading vehicle, and keep the vehicle distance close to the expected value: that is,

where ∆

derr(

k) represents the vehicle distance error and is defined as

For the purpose of providing passengers with comfort during vehicle following, the absolute values of

and

must also be as small as possible; that is,

.

represents the derivative of

, and its formula is as follows:

Solving optimization problems requires satisfying a series of constraints. Firstly, to prevent collision with the preceding vehicle, the distance between vehicles must not be less than the minimum value; secondly, to ensure that subsequent vehicles are in a suitable state, the distance should not exceed the maximum following distance; and finally, the values of velocity

a and

j(

k) should also be limited between the minimum and maximum values. To construct a manageable optimization problem, the cost function can be defined as follows:

where

represents the reference vector;

and

are the weighting matrices for control and objectives; and

and

are the open-loop predicted state and control quantity at time point

k. In the following task, it is defined as follows:

where

represents a one-dimensional vector with a value of 10.

The optimization objective and constraint conditions of model predictive control are

Considering driving style, the aggressive strategy should have safeness and comfortableness; the conservative driving strategy should have greater safeness and comfortableness. The final cost function is defined as

Regarding the composition of the dataset, driving data from 100 drivers of different regions, age groups, and driving experiences has been collected. The driving duration covers multiple scenarios: short trips (10–30 min), medium trips (30–60 min), and long trips (over 60 min), with a total of 2300 samples. Analysis of such rich and diverse data enables a more comprehensive capture of differences in driving styles among various drivers. In terms of network architecture, the constructed GAN framework includes a generator with 5 fully connected layers, each followed by a ReLU activation function to introduce nonlinear characteristics and enhance the network’s expressive ability, with a learning rate set to 0.001. The discriminator consists of 4 fully connected layers, also using the ReLU activation function, with a learning rate of 0.0005. This design ensures network complexity while avoiding overfitting. Loss evolution shows that in the early stages of training, the loss decreases rapidly, stabilizes in the later stages, and finally reaches a relatively stable low-loss state. Meanwhile, mean absolute error (MAE) and root mean square error (RMSE) are used as indicators of model accuracy. In the driving style classification task, the MAE reaches 0.15 and the RMSE is 0.2, indicating that the model can classify driving styles relatively accurately, providing a reliable basis for the learning and training of subsequent adaptive strategies.

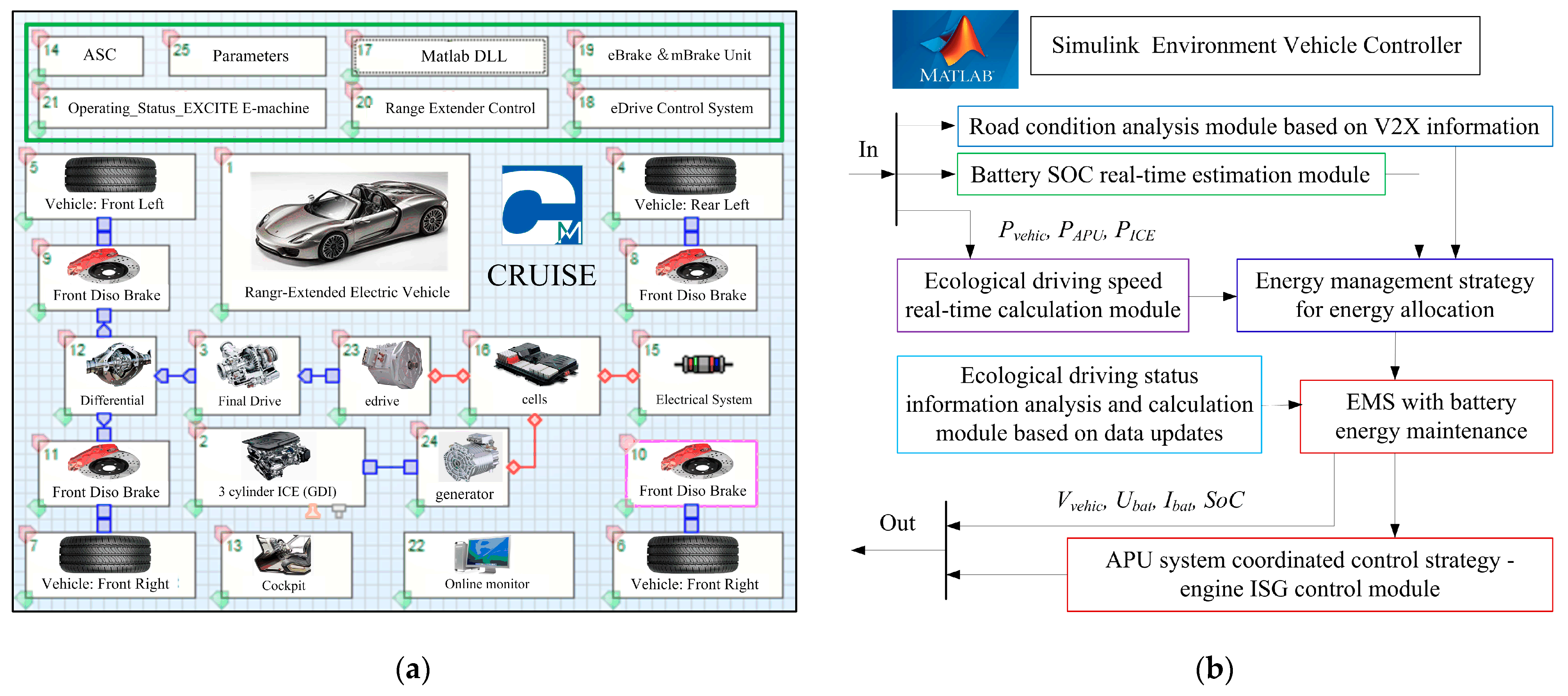

2.2. Designing of Hierarchical Dynamic Game EMS Based on Eco-Driving Speed

As environmental information and driving styles impact the eco-driving strategy, reasonable speed planning should be incorporated. The upper level involves speed planning design based on car-following behavior, while the lower level is occupied by the energy management strategy optimizer.

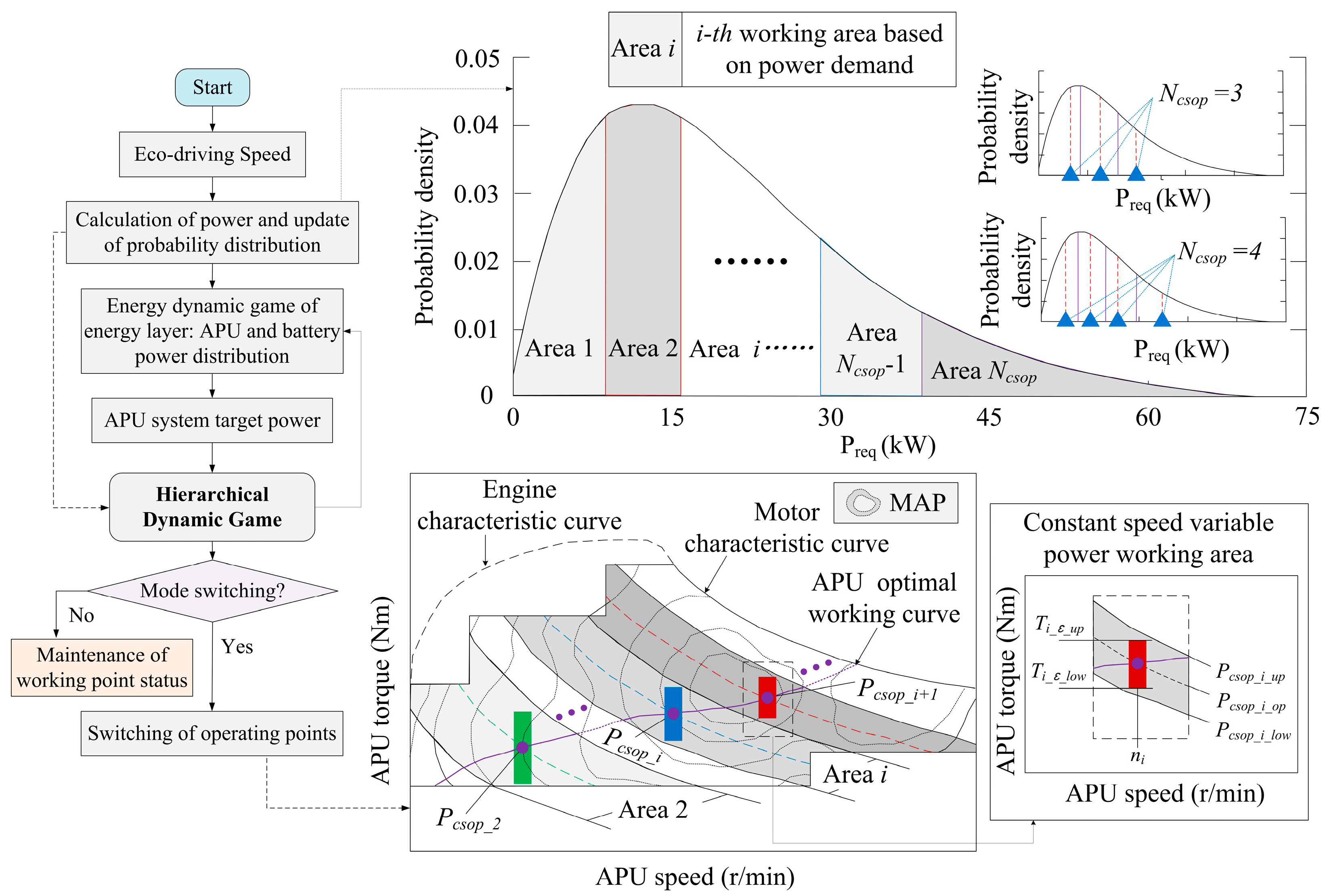

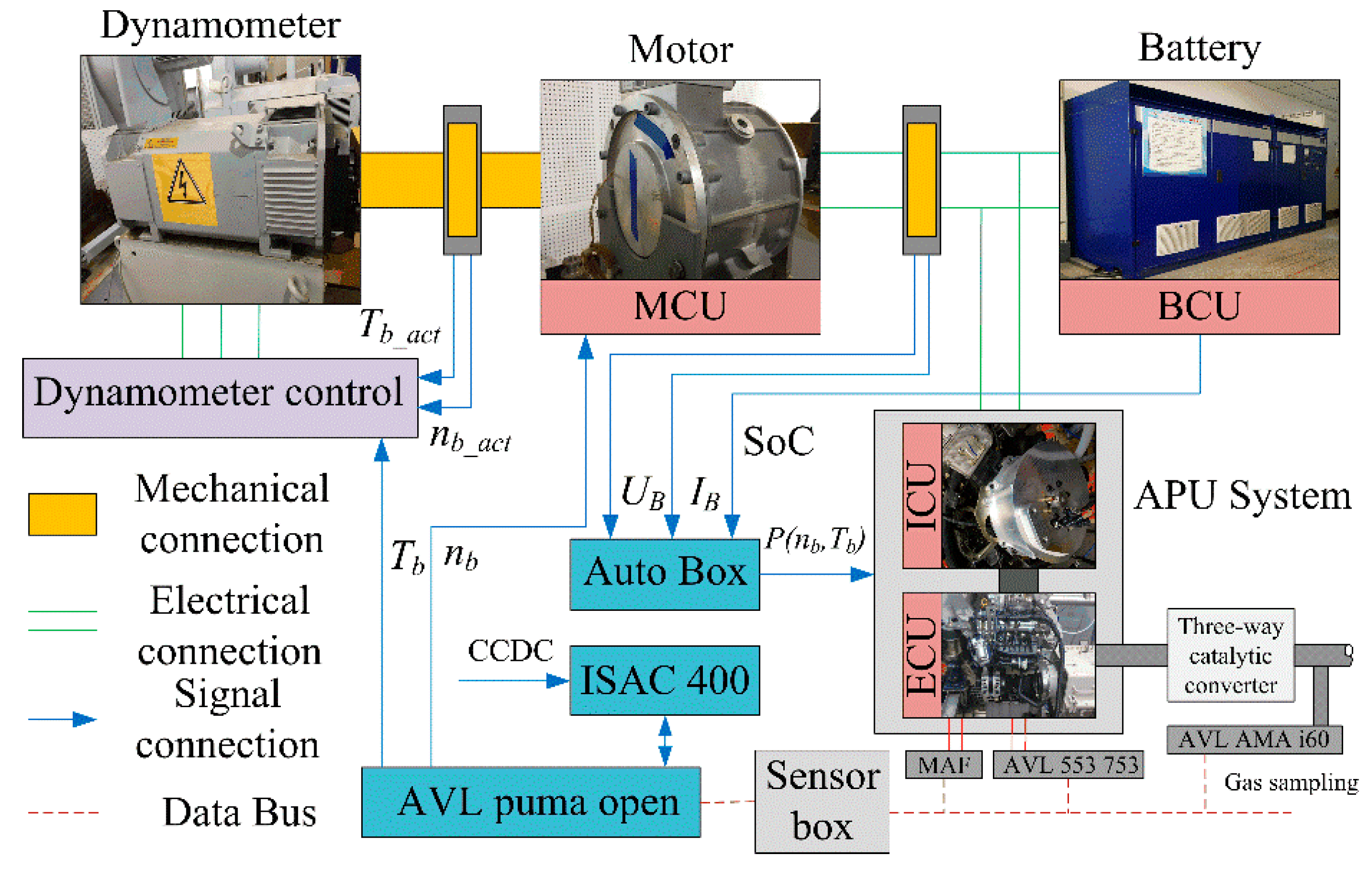

As illustrated in

Figure 2, the powertrain of the CAR-EEV is composed of a traction battery, APU, drive motor, mechanical drive mechanism, intelligent information system, and control system. This system was selected by this study as the research object for the design of the EMS.

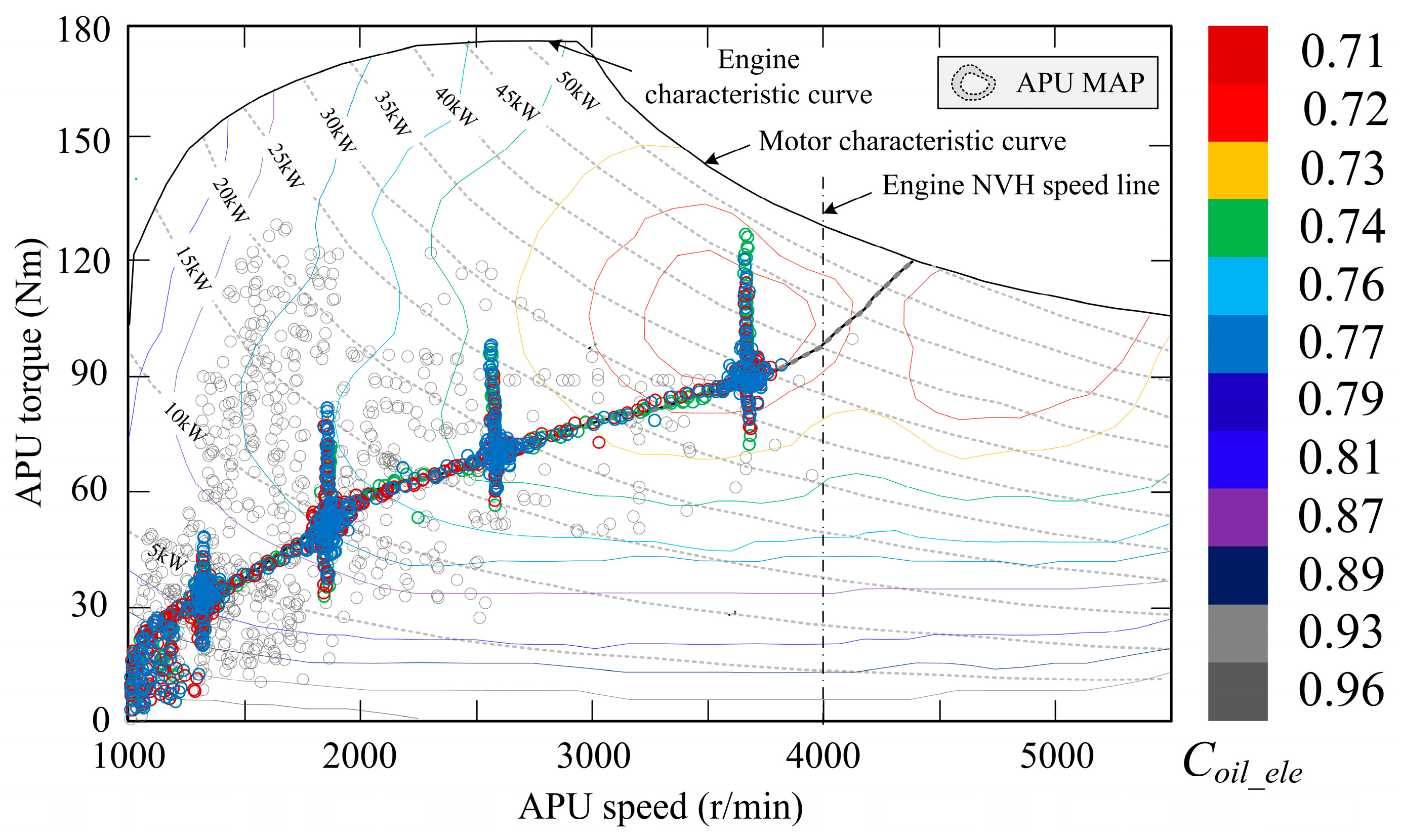

In terms of APU system work-area optimization, there are three types of rule-based APU system power-output forms (work mode/area): namely, fixed-point (constant speed, constant torque), multi-point (constant speed, variable torque) and optimal-curve power following (variable speed, variable torque), as shown in

Figure 2. The APU system operates at variable speed and torque on the optimum curve and at constant speed and torque in multi-point mode, both of which allow the APU system to follow the vehicle power requirement. When the operating point speed is considered to be continuous, the APU operating mode changes from single point to multiple points, and the number of operating points increases, to work along the optimal curve, commonly referred to as a power-following strategy. The different operating modes of the APU system can thus be described in terms of the number of APU operating points (

Ncsop) and the power range (

εi) at the speed where this operating point is located. Therefore, the operating strategy of the APU system can be structurally described as a decision logic based on

Ncsop and

εi: by synergistically optimizing these two dimensional parameters, the system can dynamically switch between fixed-point, multi-point, and power-tracking modes.

The vehicle’s required power

Preq is calculated based on the target vehicle speed under the driving cycles, and the distribution range of

Preq is statistically analyzed by dividing it into several power ranges. The cumulative power distribution function is obtained as follows:

where

Fp(

t) is the cumulative power distribution function and

preq(

t) is the probability density function of the vehicle’s required power.

The principle of the APU system working area under the power probability density function is shown in

Figure 3.

Divide the

Preq interval evenly into

Ncsop sections, with each section corresponding to a constant speed operating point of the APU system. By combining the maximum and minimum power values of the

i-th interval and the power fluctuation margin coefficient

εi, the upper and lower power limits of the APU system at operating speed

ni can be calculated as follows:

where

Pcsop_i_max,

Pcsop_i_min, Pcsop_i_up and

Pcsop_i_low are the maximum, minimum, upper and lower power in the

i-th interval;

Pcsop_i_opt is the power of the APU system operating at the optimal curve; and

εi is the power fluctuation margin coefficient. ∆

Pi_ε is the power coverage size. The torque at operating speed

ni in the

i-th interval is calculated as follows:

where

Ti_ε_up and

Ti_ε_low are the upper and lower torque limits of the APU system operating in the

i-th section; the switching thresholds for two adjacent working points are set to

where

Pi_cr_up is the APU power threshold when switching between the

i-th interval and the

i+1-th interval, and

Pi_cr_low is the APU power threshold when switching between the

i-th interval and the

i−1-th interval.

Finally, the target power and torque values of the APU real-time operating point are calculated as follows:

where

PAPU_act,

nAPU_act and

TAPU_act are the real-time target output power, speed, and torque values of the APU system, respectively.

The study uses the DP algorithm, which combines the data of engine fuel consumption, emissions, and ISG engine efficiency characteristics to obtain the optimal operating curve of APU system energy-consumption emissions characteristics [

6]. Based on this curve, the APU system operating mode/area control strategy is designed.

2.3. Principle of APU Operating Point-Switching Decision Based on Dual Dynamic Game

In order to improve the cognitive intelligence of CAR-EEV vehicle decisions and achieve intelligent vehicle control, in this section the power allocation and the decision as to whether to switch APU operating modes/points are addressed, based on the dynamic game in the context of multi-source V2X information. A feasibility analysis of the APU operating point switch under multi-point modes is also required. If the conditions for switching to the optimal operating point are met, it is necessary to consider whether the APU system can operate continuously for a certain period of time, to better meet the power demand without switching again; because of this conversion, the dual energy source system has better work efficiency after the point is switched [

18]. This involves achieving efficient operation of both the APU and battery systems, which enables connected CAR-EEV to engage in multi-step game interactions with V2X, thereby achieving higher system efficiency.

Considering the complexity, non-uniqueness, and coordination of APU multi-point operating modes in the power-following process, an intelligent switching non-cooperative dynamic game decision algorithm is established. Game theory paradigms are used to address potential conflicts between point/mode switches, considering energy consumption, emission reduction, and battery-life friendliness. The detailed modeling of power demand for the powertrain system under complex scenarios is refined into four parts: game benefits that integrate energy-saving and emission reduction, V2X information, reducing battery-capacity decay, and comprehensive performance indicators. Finally, a comprehensive performance index is established, incorporating different weight coefficients and considering vehicle dynamics constraints and road speed limits as the game’s total payoff function or optimization objective. The dynamic game interactive-decision process is unfolded using game trees, and subgame-perfect Nash equilibria for each continuous stage of the game are sought [

21]. The potential conflicts during the real-time judgment of APU operating point/mode switches are evaluated. A detailed design of the game-mode switch rule table is developed by combining standardized switching thresholds with whether APU operating-mode switching has been completed. The decision process for the APU system-operating point switching involves current power, target power demand, the span of current speed to target speed (

ni+1−

ni), the demand torque at the current speed, and the span of target torque (

Ti+1−

Ti). The main factors influencing the speed switching of the APU system include one subjective factor (driving style) and two objective factors (road congestion and battery level). In a multi-source information environment, considering the control target from multiple perspectives, the APU system operating point-switching model is more complex than conventional control modes (based on threshold switching). The most significant difference from conventional operating conditions is the predictability of future driving conditions. Therefore, an intelligent decision system has the opportunity to fully consider the impact of global optimization modes when calculating future power demand and energy management. APU work point-switching strategy based on the dynamic game algorithm is shown in

Figure 4. Firstly, it is necessary to determine whether the APU system intends to switch the operating point power: is there a change in the target speed ∆

ni > 0? This is determined by comparing the current APU operating point with the speed difference from the optimal target operating point under power demand to establish the target speed. If the demand for the optimal operating point does not require a speed change, and the operating condition demand duration exceeds a predefined time threshold, it indicates that the target operating point provides sufficient working time and space, and the APU operating point maintains its original working mode. Conversely, if the conditions for game initiation are met, indicating a conflict of interest in whether the APU operating point should switch, a game is initiated. In this case, the dynamic game algorithm of the EMS system is activated. During the game, efforts are made to determine the optimal timing for operating point switching, calculate the payoff function, construct the payoff matrix, solve the optimal strategy combination for the current stage, and choose the target operating speed. Finally, a dynamic game is carried out based on the APU’s multi-point strategy selection, until the termination conditions of the game are met.

The detailed determination processes of the utility functions and the Nash equilibrium for the two participants have been clearly presented, as follows:

where

Cs is a state-of-charge maintenance cost,

S is the current SoC,

Smin,

Smax are the target SoC range,

α is the penalty coefficient for SoC deviation from the target range,

η is the charge–discharge efficiency,

β is the impact coefficient of charge–discharge cycles on lifespan, and

Pmax-battery is the maximum output power of the battery.

Ccycle is the calculation formula for the per-cycle cost.

Combining the above three costs, the utility function of the battery (

Ubattery) can be expressed as

Procedure for determining the Nash equilibrium: the strategy space of the battery (with different output powers Pbattery, whose value range is [0, Pmax-battery]) and the strategy space of the APU (with different output powers PAPU, whose value range is [0, Pmax-APU]), and whether to switch operating points are specified; for each strategy combination of the battery and APU, the corresponding utility function values Ubattery(Pbattery, PAPU) and UAPU(Pbattery, PAPU) are calculated, and the payoff matrix is constructed. Then, the iterative method is employed to find the Nash equilibrium.

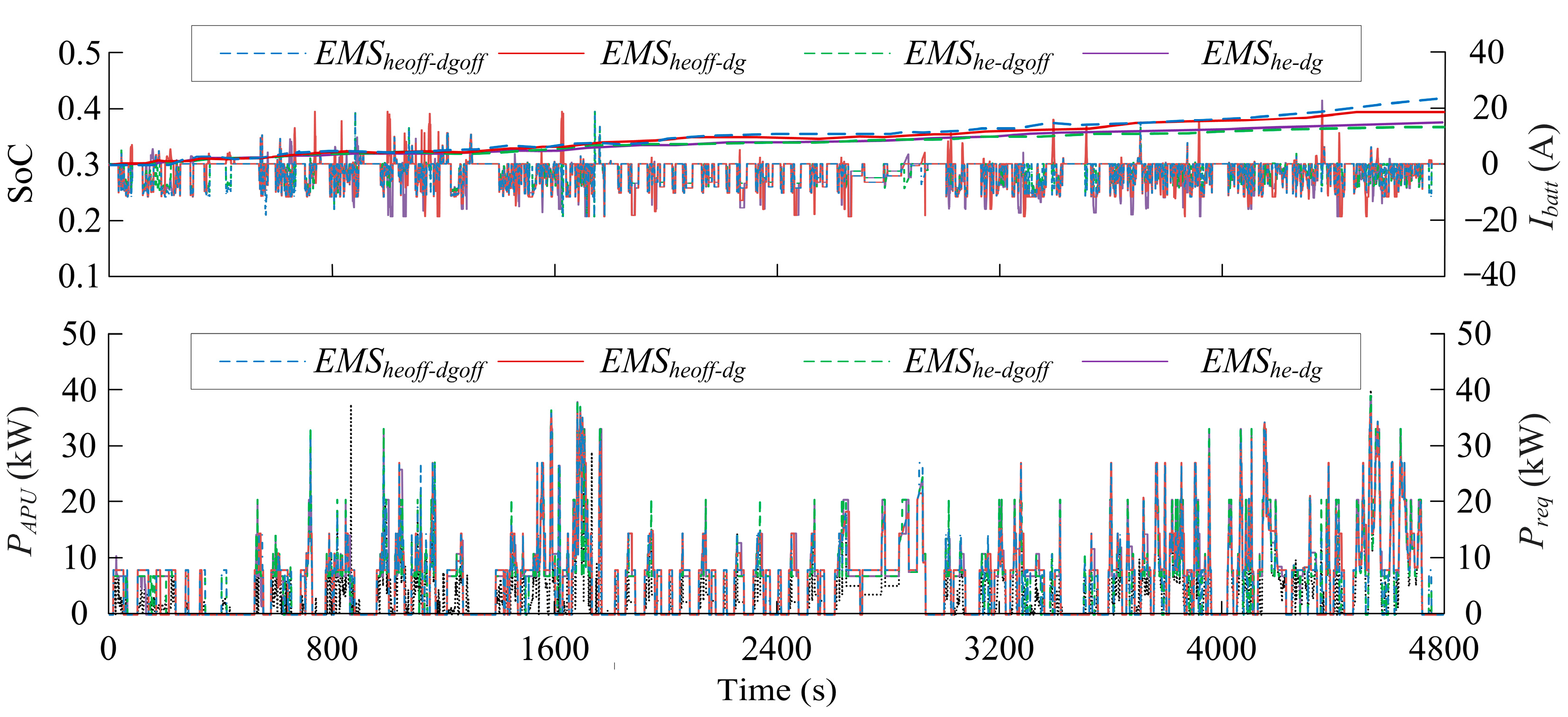

2.4. Multi-Objective Evaluation Model for EMS Considering Energy Consumption Emissions and Battery Life

While the fixed operation of APU at high-efficiency operating points can reduce energy consumption and emissions, this mode of operation can increase battery usage and shorten battery life. The parameter optimization of the HDGEMS design considers 3 primary objectives, and the HDGEMS described in

Section 2 is optimized from a multi-objective perspective. The optimization of the APU system operation mode/area is conducted based on the MOO research framework, in this section, in order to verify whether the proposed MOO method can achieve a better balance among energy consumption, emissions, and battery life. The EMS performance index considers three metrics: the oil–electric conversion loss rate (

Coil_ele), comprehensive exhaust emissions (

Ecom), and the battery-capacity loss rate (

Qloss) [

22]. The APU serves as one of the energy sources for CAR-EEV, and all fuel consumption and emissions originate from the engine. This section outlines the evaluation criteria used to assess fuel consumption and exhaust emissions, as follows. Since the engine is mechanically linked to the generator in the APU system, solely considering the engine’s oil consumption characteristics fails to accurately represent the vehicle’s overall energy consumption. Taking into account the engine efficiency, the

Coil_ele is calculated as follows:

where

ηele is the power-generation efficiency of the generator;

ηoil is the efficiency between fuel and the effective power of the engine; and

ρ is the calorific value of petrol, which is 4.6 × 10

7 J/kg. It is evident that

Coil_ele defines the energy-transmission loss rate, and a smaller

Coil_ele value corresponds to better fuel economy.

The conventional exhaust gases (

CO,

CH and

NOx) are considered in the APU comprehensive exhaust-emission characteristic function

Ecom, and the

Ecom is calculated as follows:

where

ECO,

ECH and

ENOx are CO, CH and NOx emission characteristic functions and

ξCO,

ξCH and

ξNOx are the weight coefficients of

ECO,

ECH and

ENOx, respectively. [

ξCO,

ξCH,

ξNOx]

T = [0.4, 0.3, 0.3]

T.

Undoubtedly, the repeated charge and discharge cycles of the battery storage system will affect the aging speed of the battery. The optimal charging capacity can be achieved by modifying and controlling the charging-current profiles, and the negative impact of current on battery life can be minimized [

23]. The battery-capacity loss rate

Qloss is calculated to evaluate the battery-life model.

Due to the limited space of this paper, this research primarily focuses on the application of

Qloss (for simplicity), and detailed experimental information on the fitting and determination of battery-life model parameters can be found in Ref. [

23]. In this article, the fitting parameters in this paper are set as

Q1 = 0.495 and

Q2 = 0.379. The operating temperature is also a crucial factor affecting the battery life. In this study, the battery operating temperature is standardized at 25 °C. Finally, the

Qloss is obtained as follows:

where

DOD is the depth of discharge (

DOD = 0.7);

Ahcell is the cumulative capacity of the battery;

Ibat(t) is the battery current;

Tcyc is the total cycle time; and

Ncyc is the number of cycles.

In engineering practice, determining the preferred solution is critical. In this paper, the linear normalization method is selected for optimal decision, which is a practical and efficient multi-objective normalization optimization method, and can clearly reflect the weight assigned to the optimization objective. In addition, it is necessary to standardize the cost function for each dimension before using the linear normalization method. Furthermore, the three objective functions,

Coil_ele,

Ecom and

Qloss possess different physical connotations. In order to reach the final quantitative decision, these objective functions need to be combined into a one-dimensional cost function. This study adopts a multi-objective normalization method and uses the following normalization formula:

where

X(nor) is the normalized result of the objective function;

Xp is the original data in the Pareto optimal solution set; and

Xp(max) and

Xp(min) are, respectively, the maximum and minimum values of the original data in the Pareto optimal solution set.

The comprehensive optimal performance function of the APU system, called the optimal comprehensive vehicle performance (

Icom_ovp), is defined as follows:

where

Icom_ovp is the comprehensive performance evaluation index;

ωC,

ωE, and

ωQ, respectively, represent the weight coefficients assigned to

Coil_ele,

Ecom, and

Qbatt_loss.

Coil_ele defines the energy-transmission loss rate, and a smaller

Coil_ele value corresponds to better fuel economy.

Ecom reflects the comprehensive emission level, and a smaller

Ecom value corresponds to better exhaust quality.

Qbatt_loss is used to quantify the degree of performance degradation during battery use, including capacity degradation, internal resistance increase, etc., reflecting its remaining usable life. The selection of weight coefficients plays a crucial role in determining the final results. Based on the hierarchical analysis method [

24], the multi-objective evaluation matrix is obtained as shown in

Table 1, and the weight vector result is calculated as [

ωC,

ωE,

ωQ]

T = [0.41, 0.13, 0.46]

T. This result becomes an important reference for the selection of weight coefficients. It should be noted that considering the catalytic conversion effect of the three-way catalyst weakens the relationship between the exhaust-emission level and the direct engine-emission content. Therefore, the weight factor of

Ecom is relatively small, while the weight factors of

Coil_ele and

Qbatt_loss are comparable. It is worth mentioning that different multi-objective evaluation matrices will produce different weight factors. In this study, the selected weight parameters are [

ωC,

ωE,

ωQ]

T = [0.4, 0.2, 0.4]

T. The source of the matrix elements is determined by inviting experts and combining design experience with the AHP scaling method to compare and score each indicator pairwise, and then calculating the geometric mean to obtain the matrix elements.