Tooth Surface Contact Characteristics of Non-Circular Gear Based on Ease-off Modification

Abstract

1. Introduction

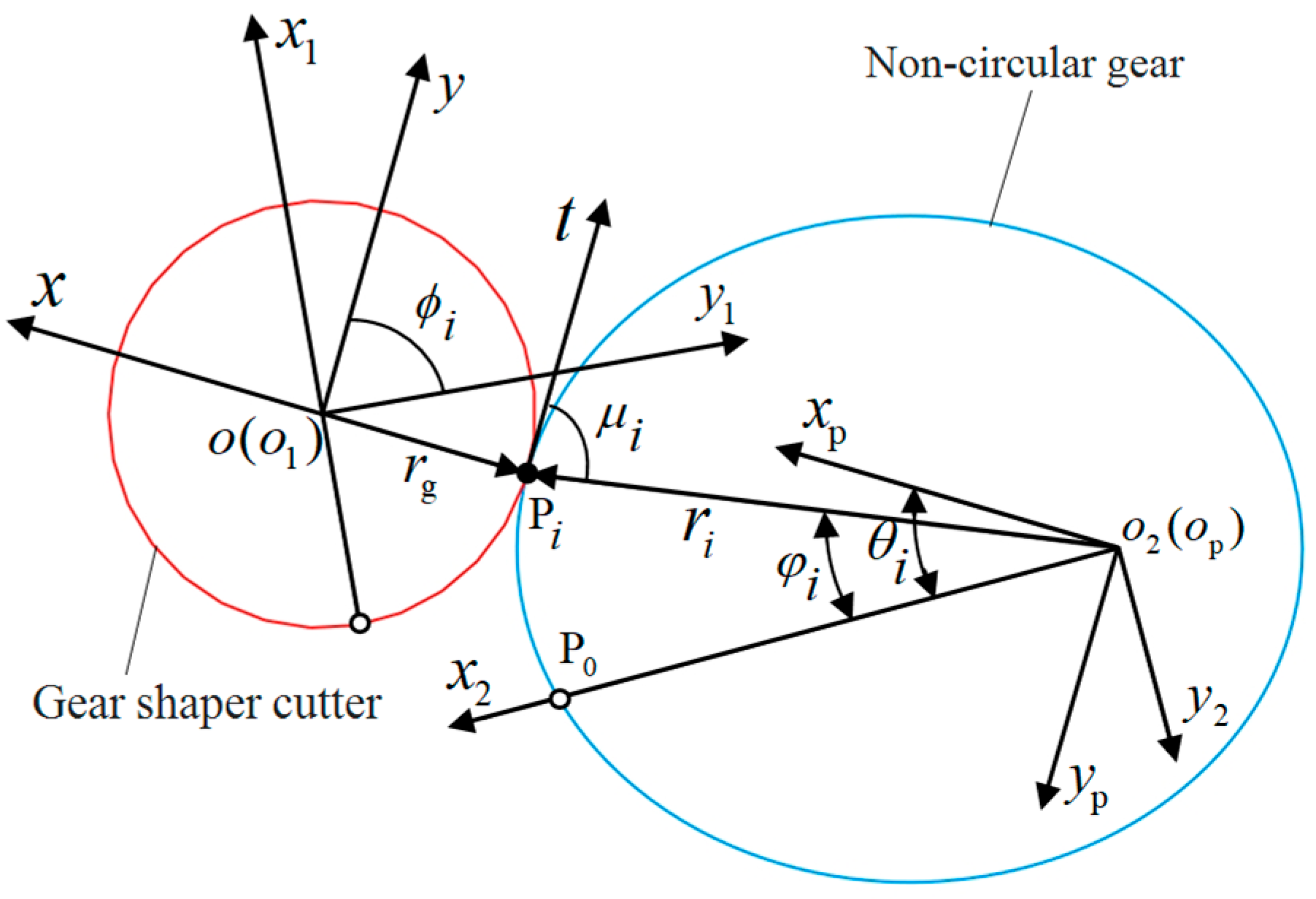

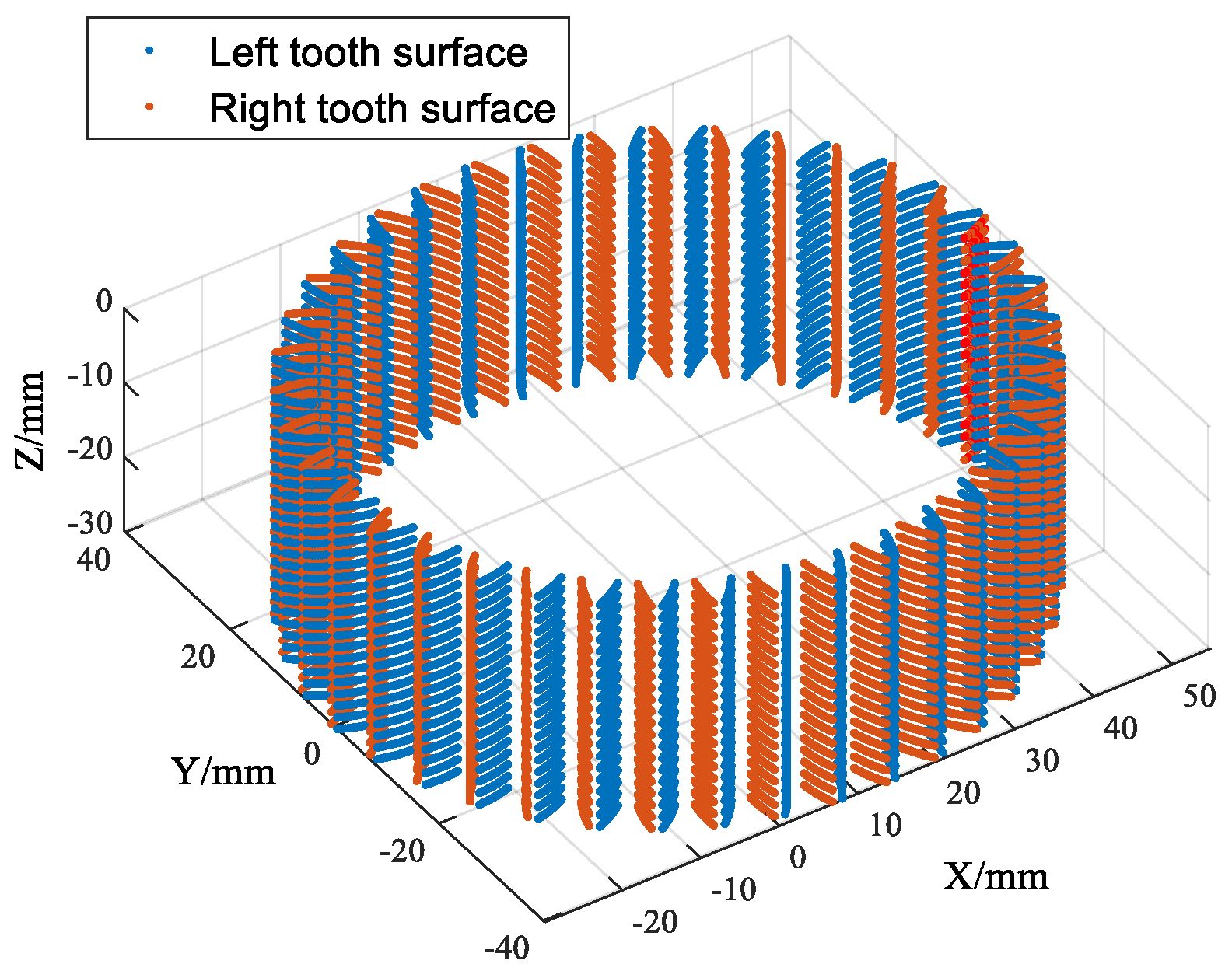

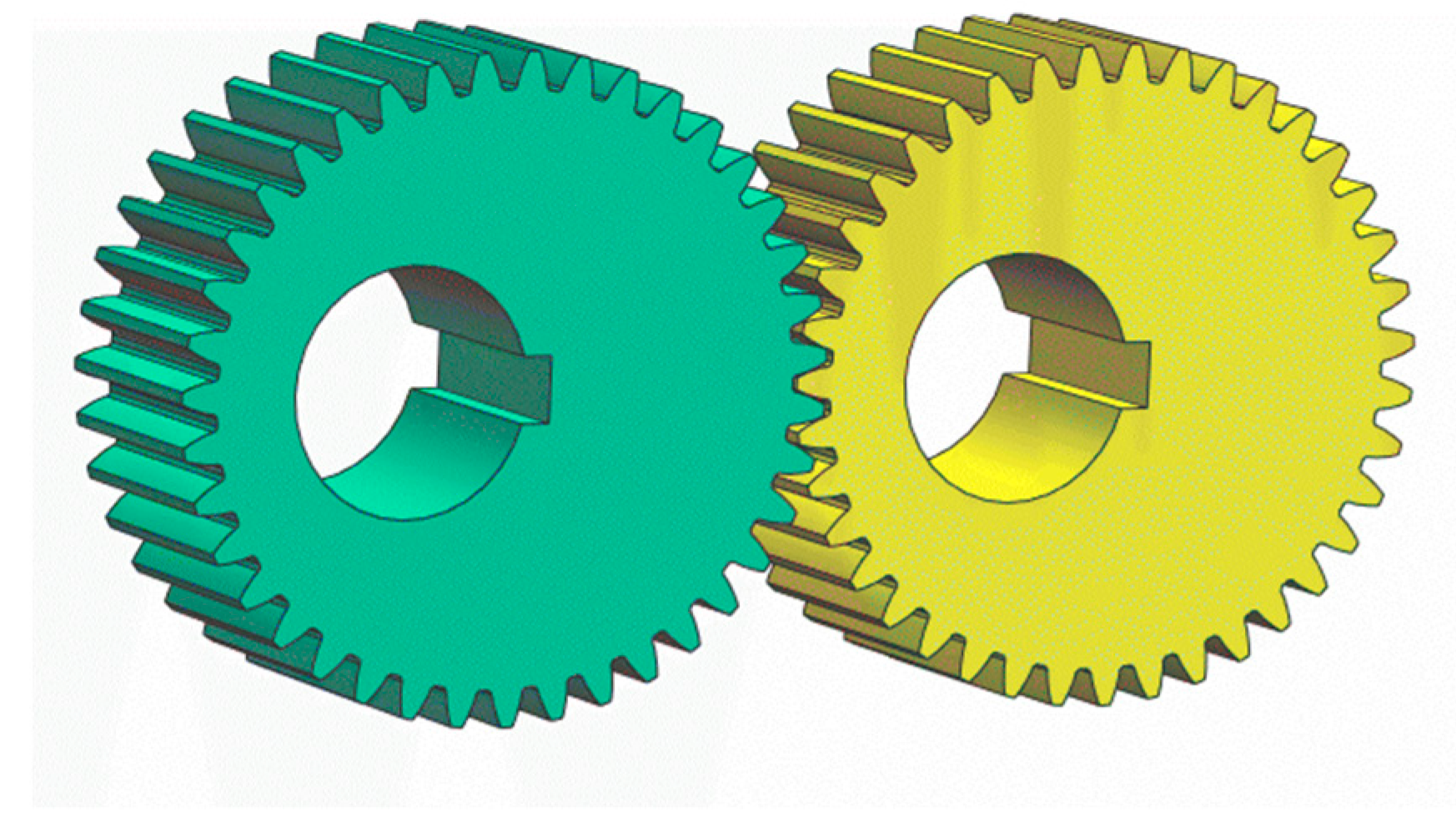

2. Mathematical Modeling of Non-Circular Gear Tooth Surface

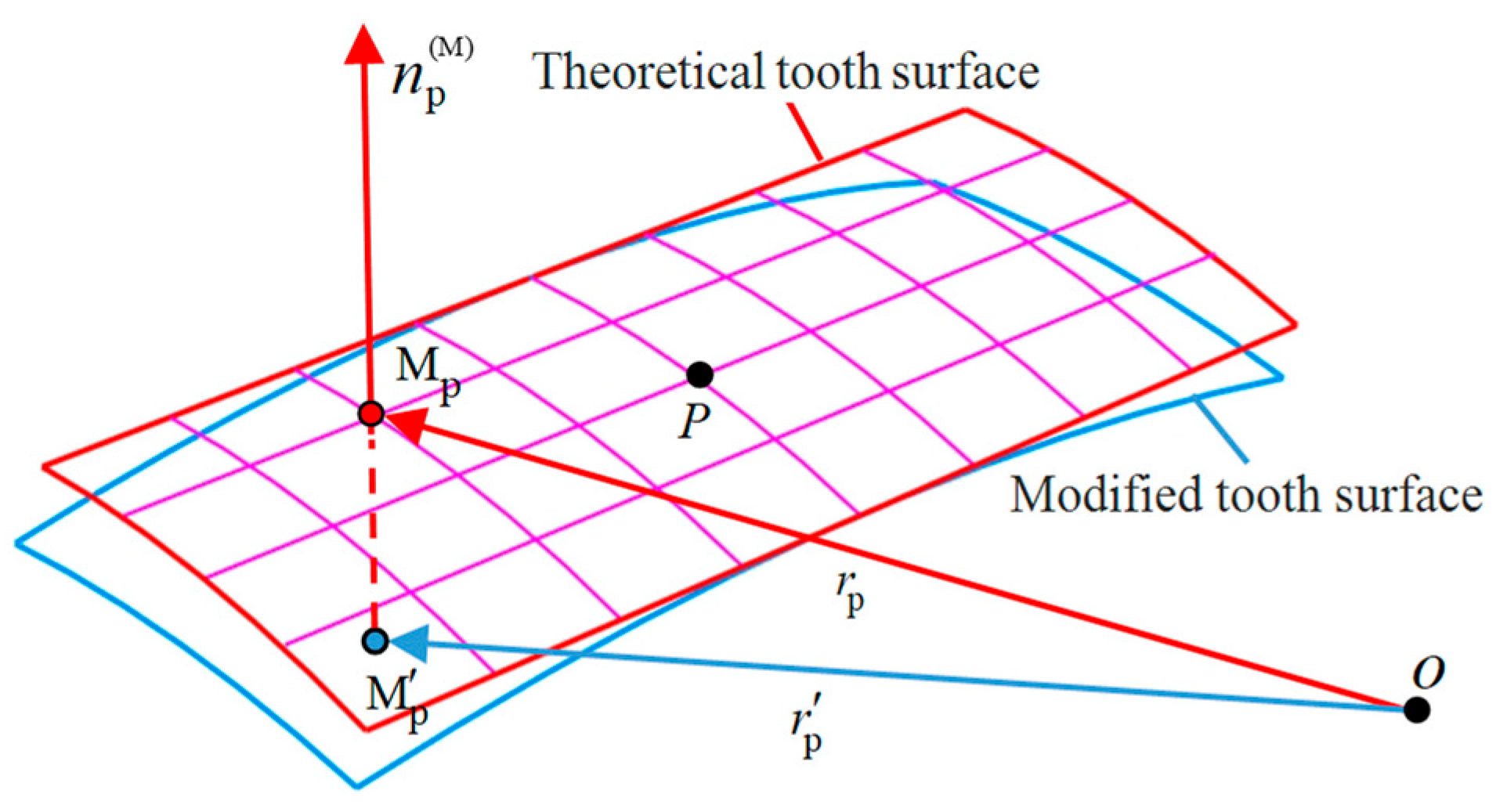

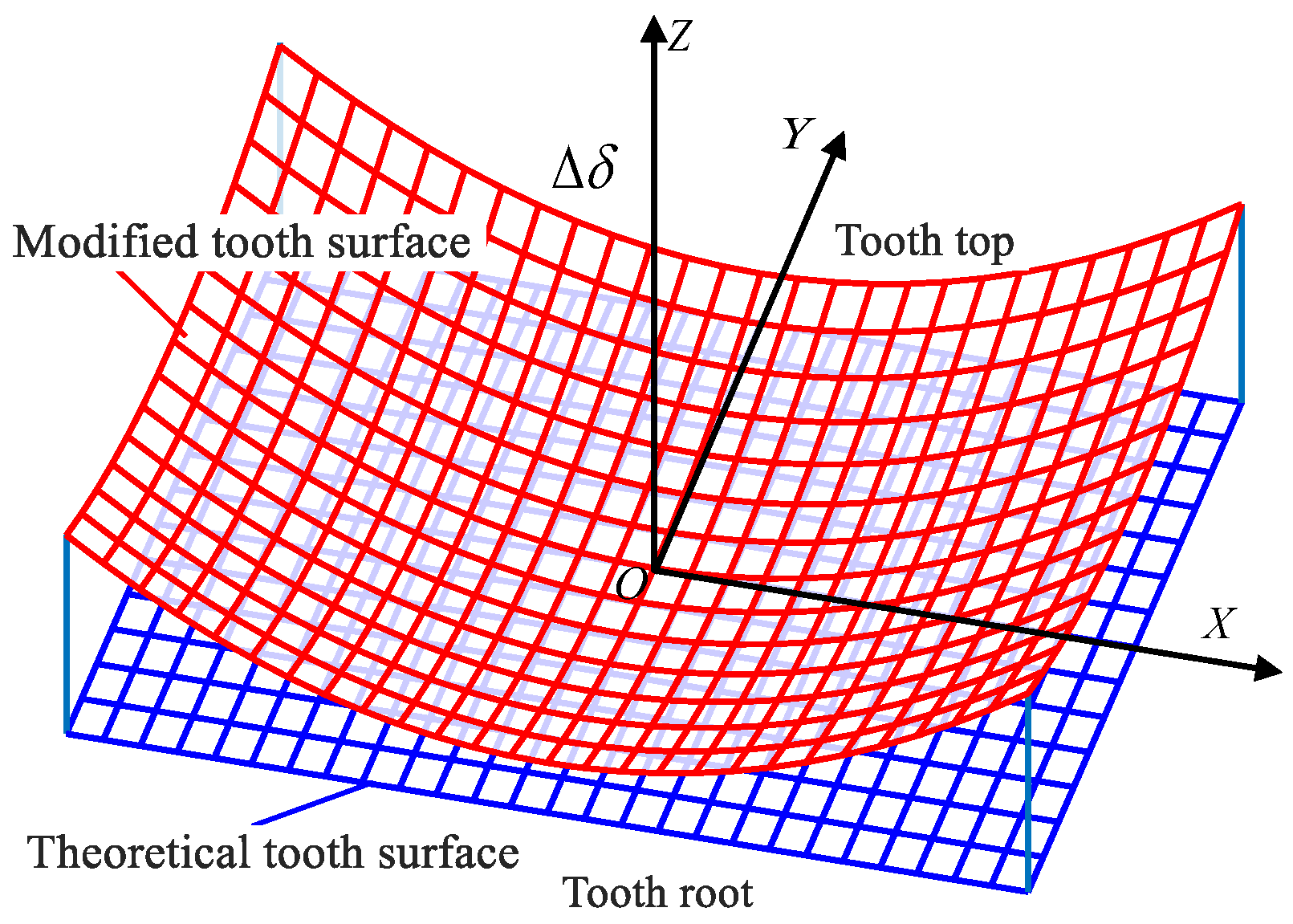

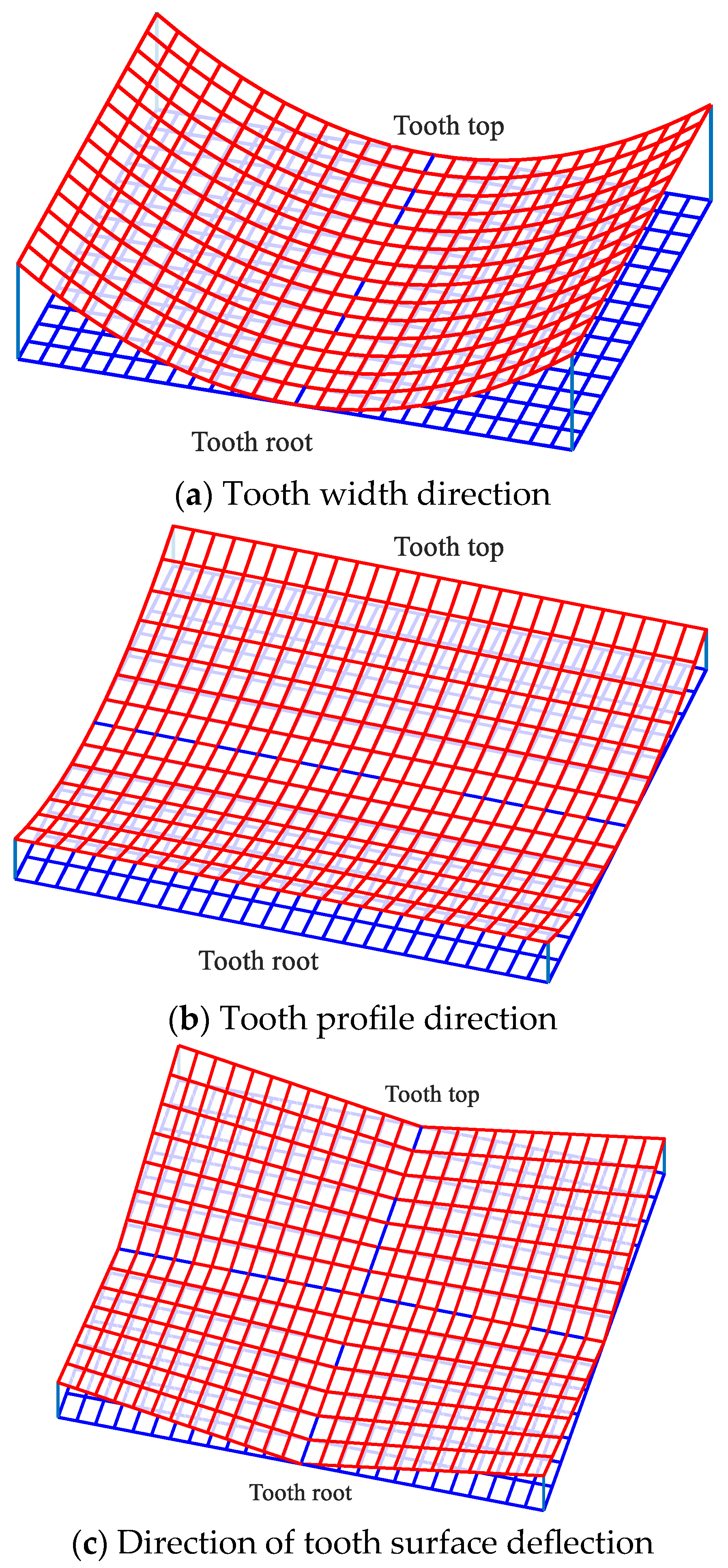

3. Design Method for Ease-off Modification

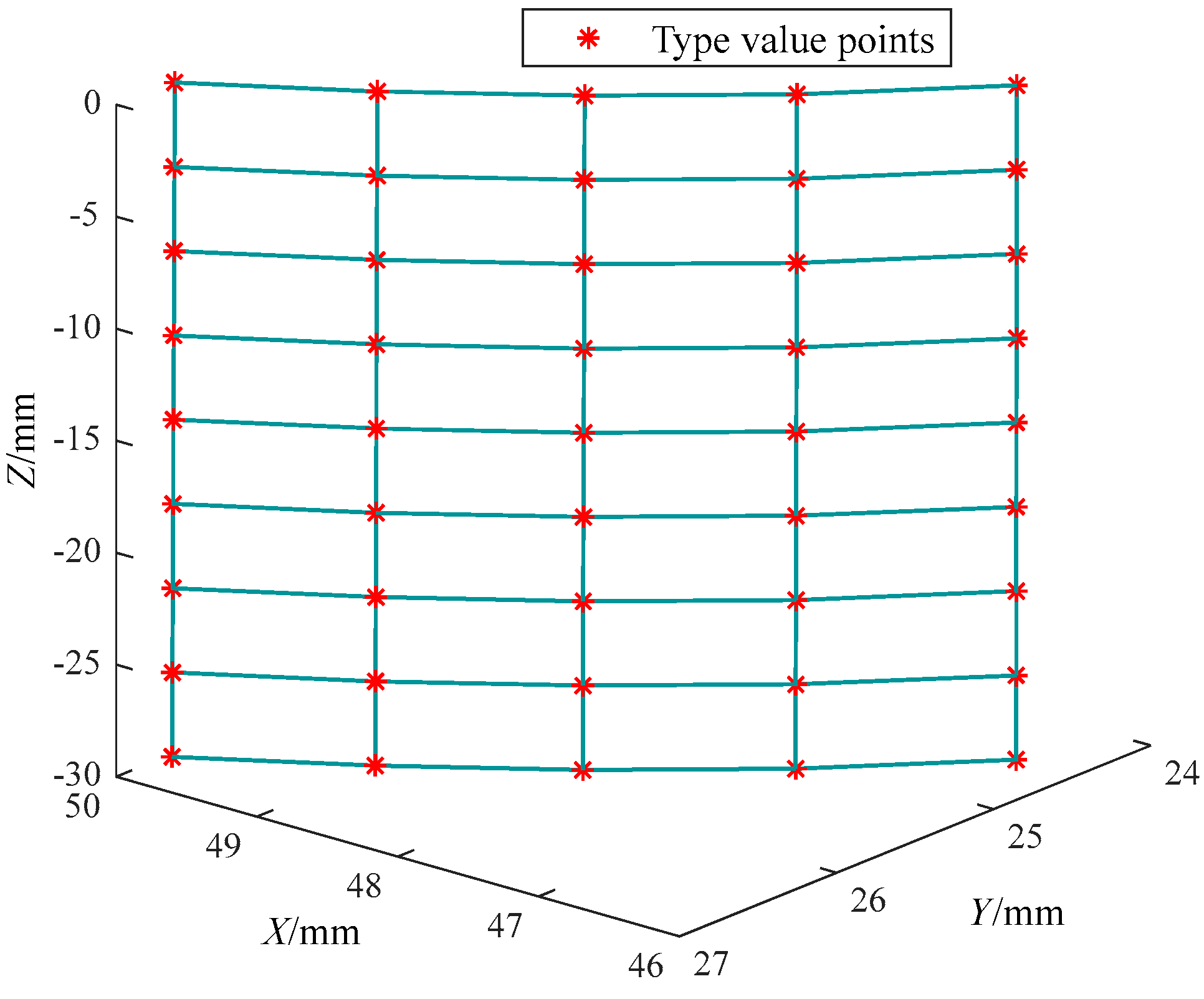

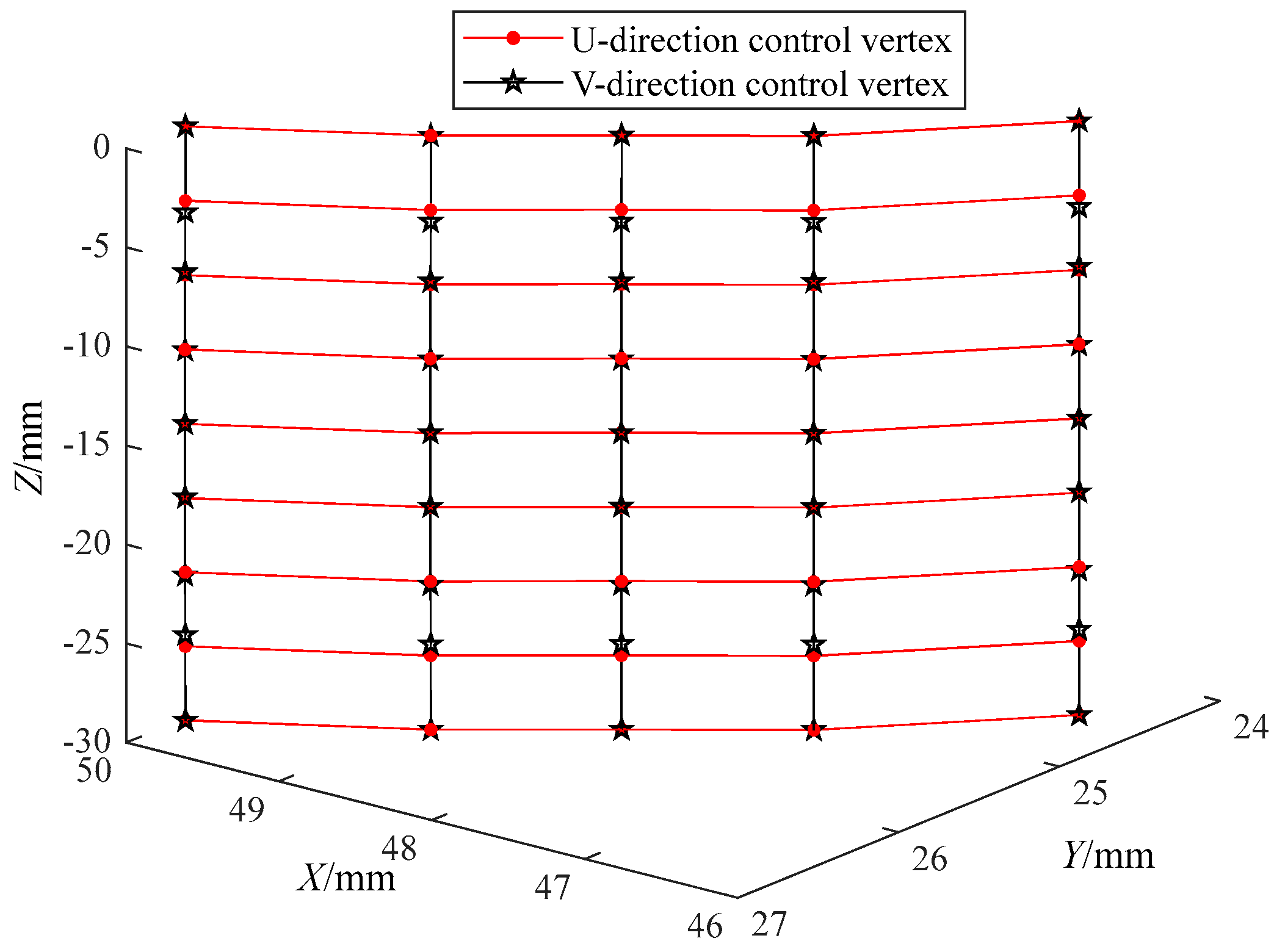

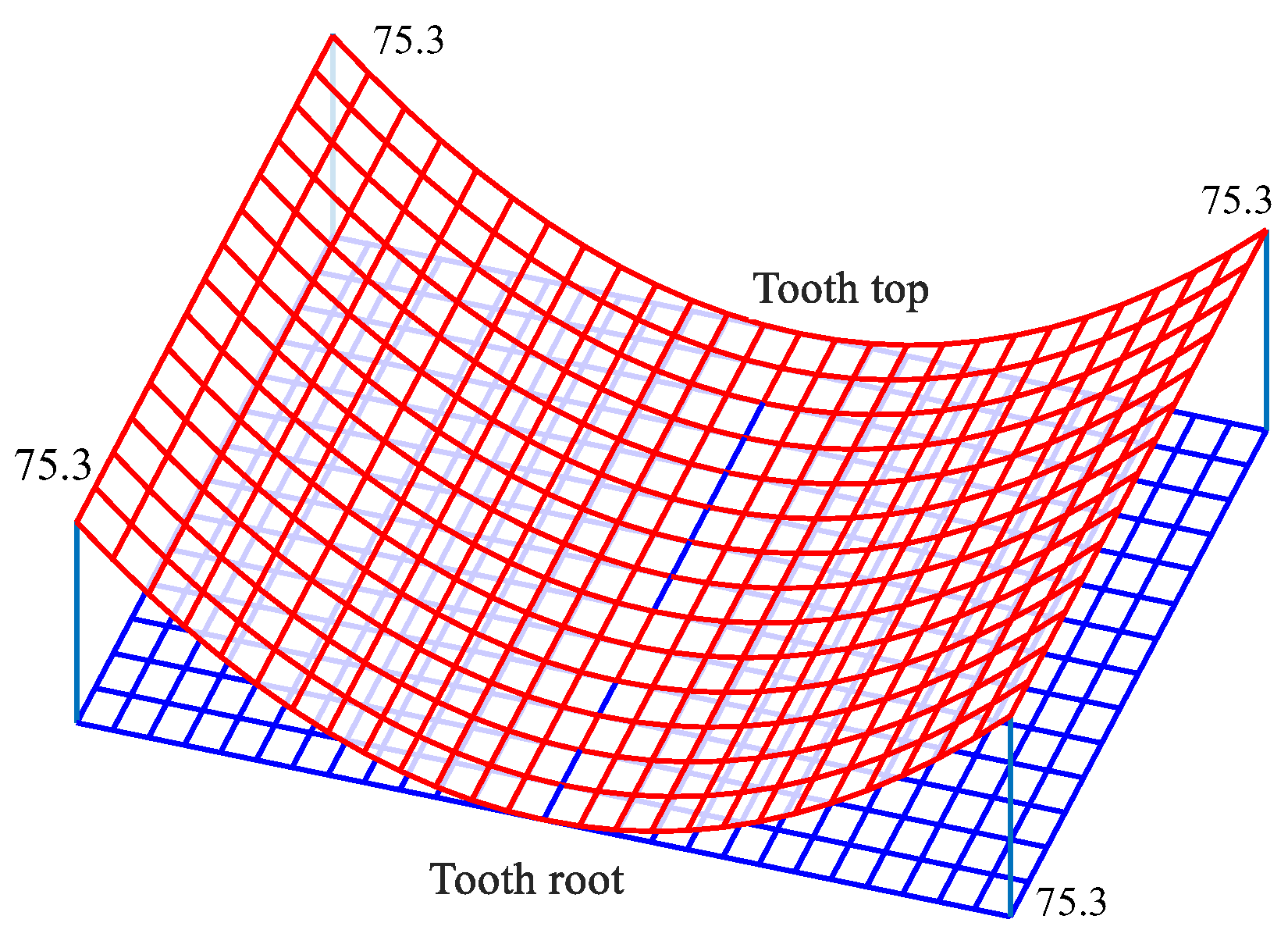

4. Digital Fitting of the Tooth Surface of a Modified Non-Circular Gear

4.1. Definition of the NURBS Surface

4.2. Double Cubic NURBS Surface Fitting

5. Tooth Contact Analysis of Modified Non-Circular Gear

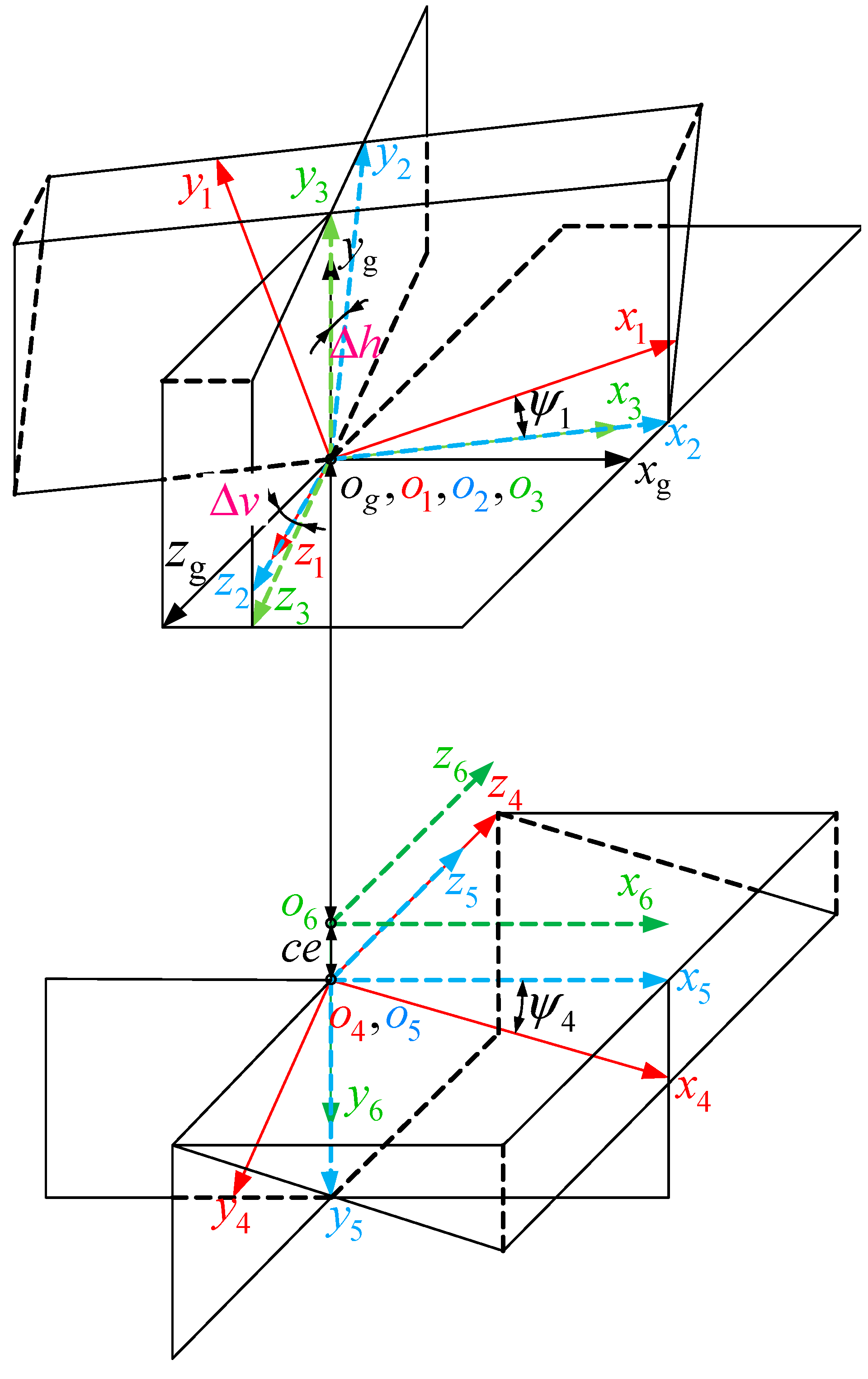

5.1. Mathematical Modeling of TCA for Modified Non-Circular Gear with Installation Errors

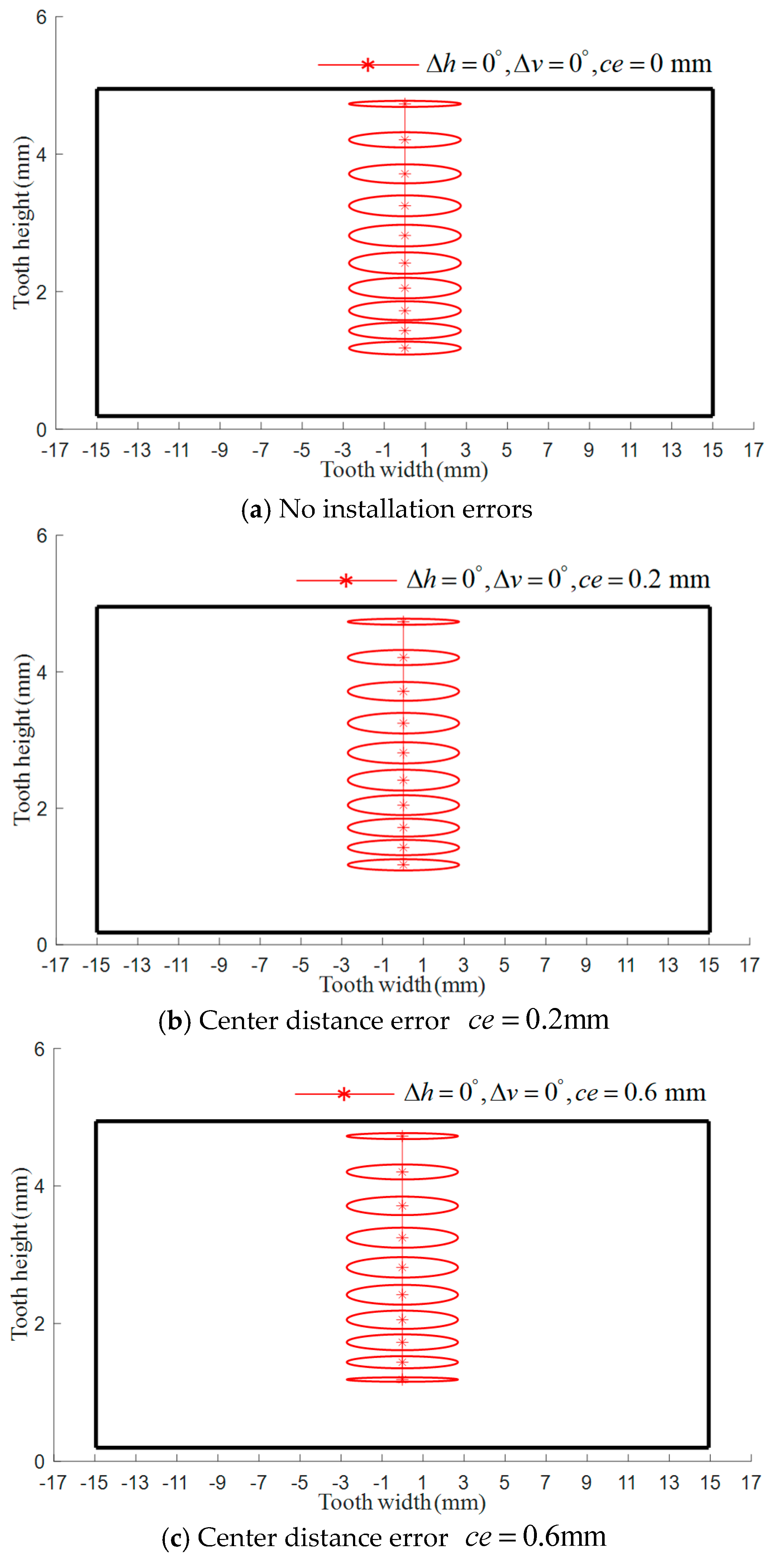

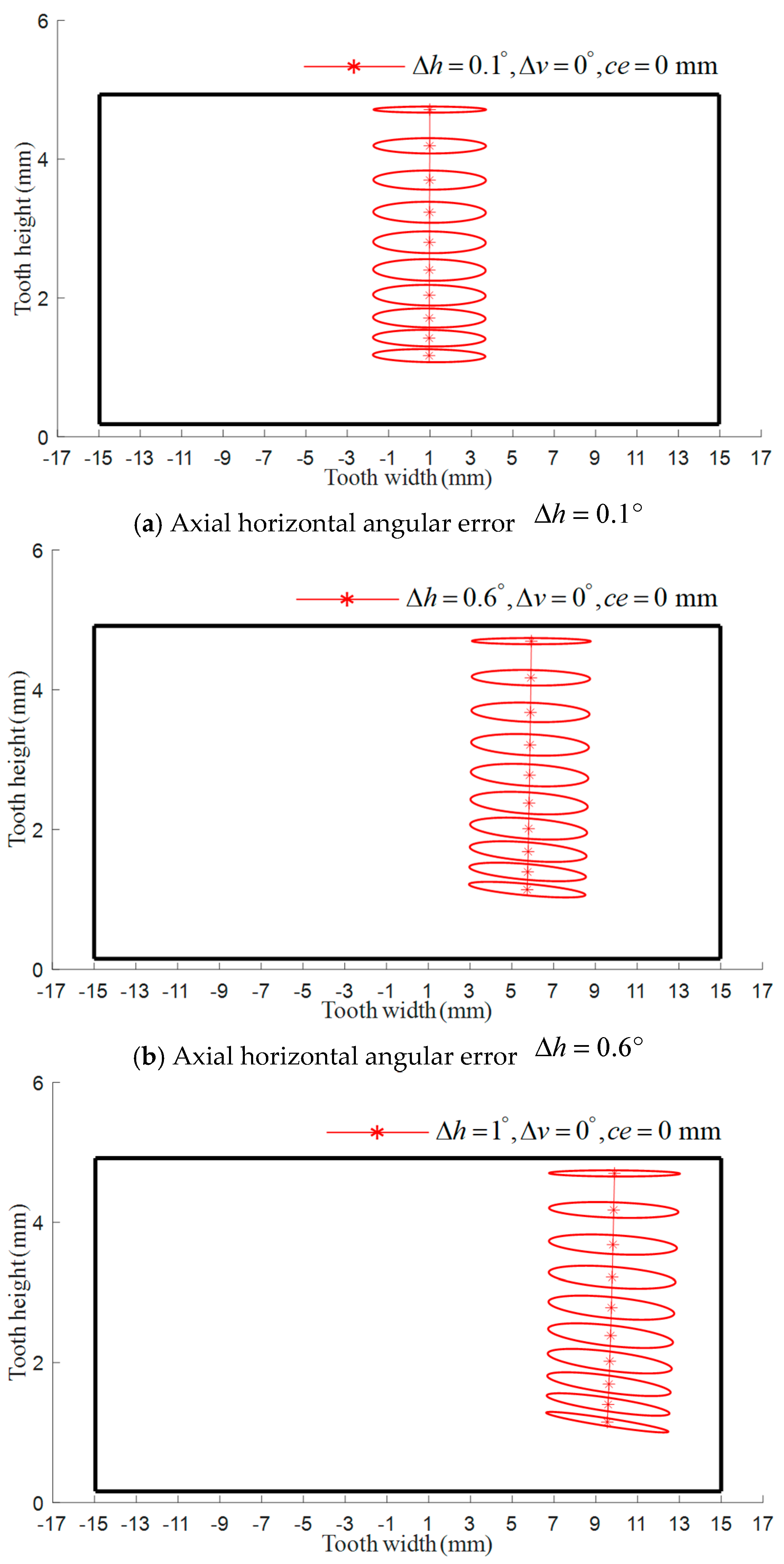

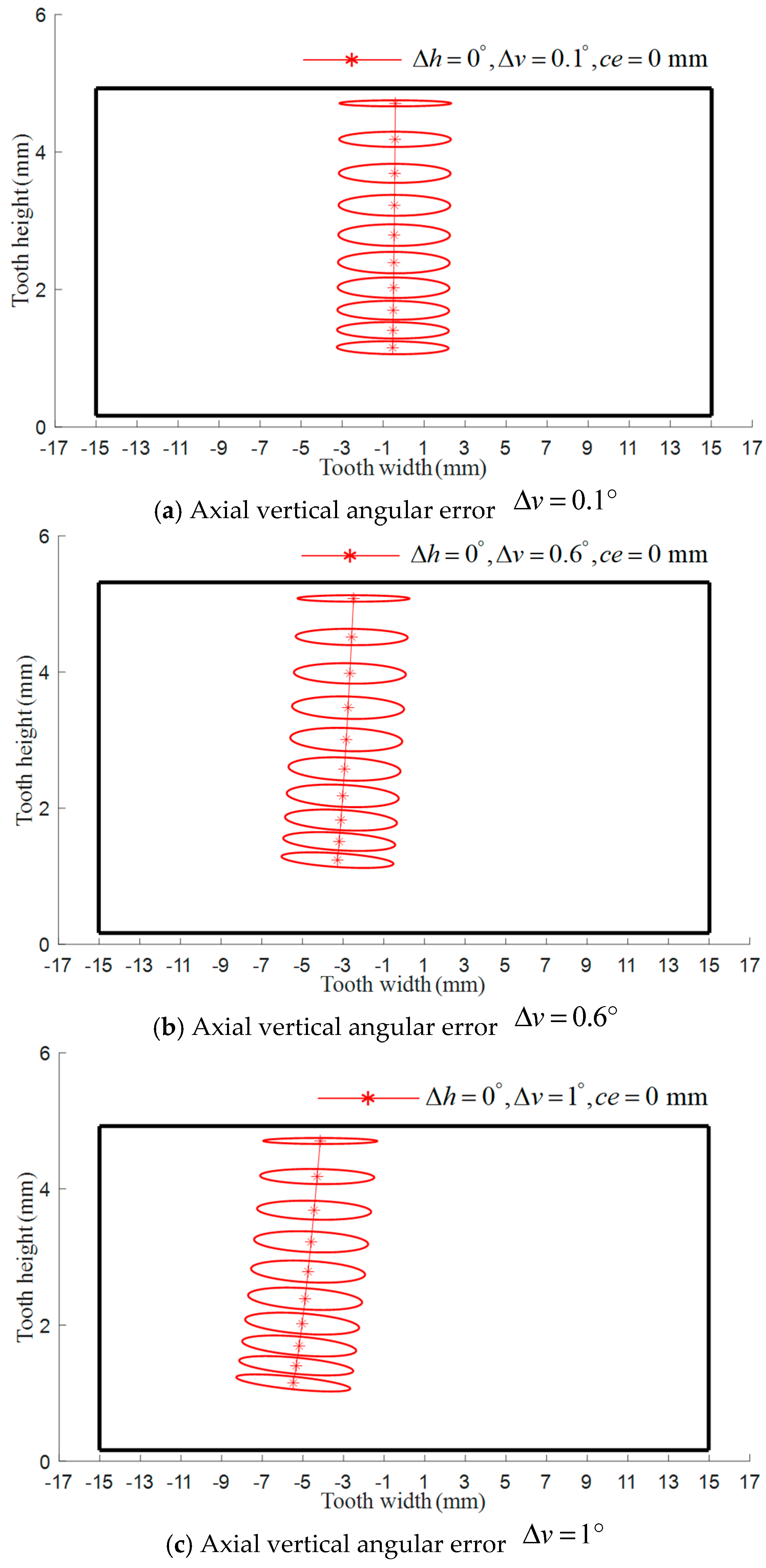

5.2. Influence of Installation Errors on the Contact Characteristics of the Tooth Surface of a Modified Non-Circular Gear

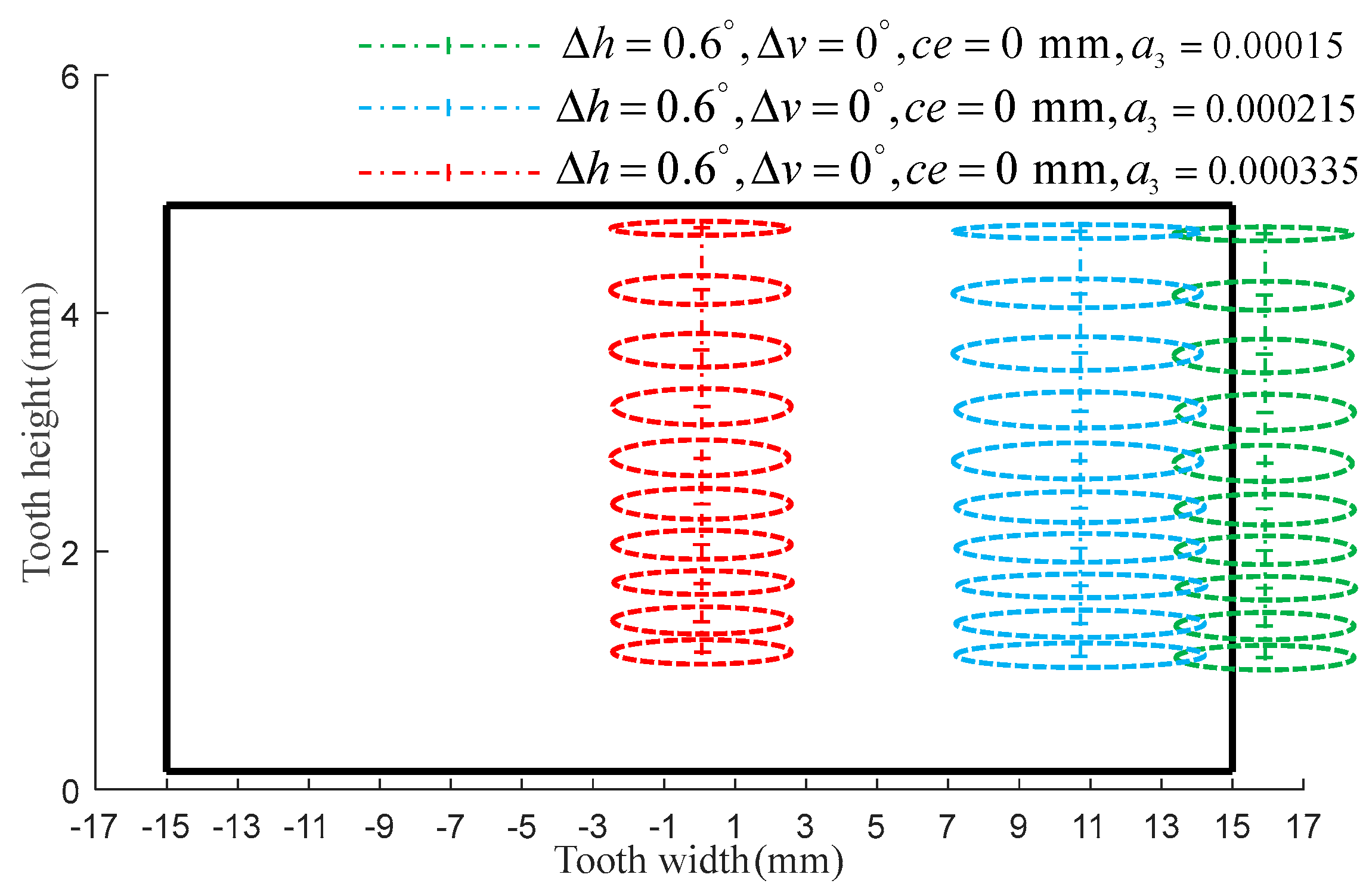

5.3. Effect of the Longitudinal Modification Coefficient on Tooth Surface Contact Behavior

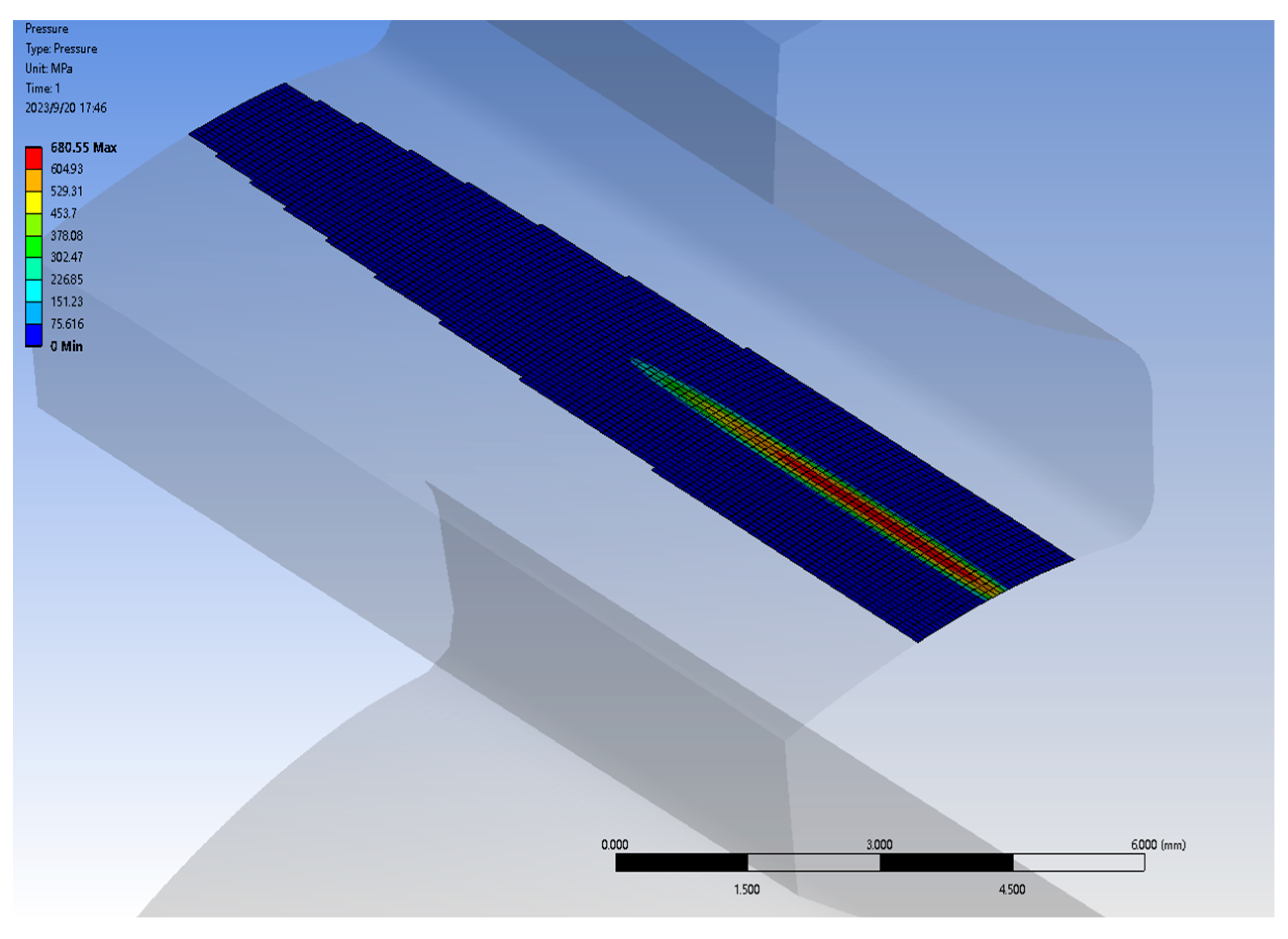

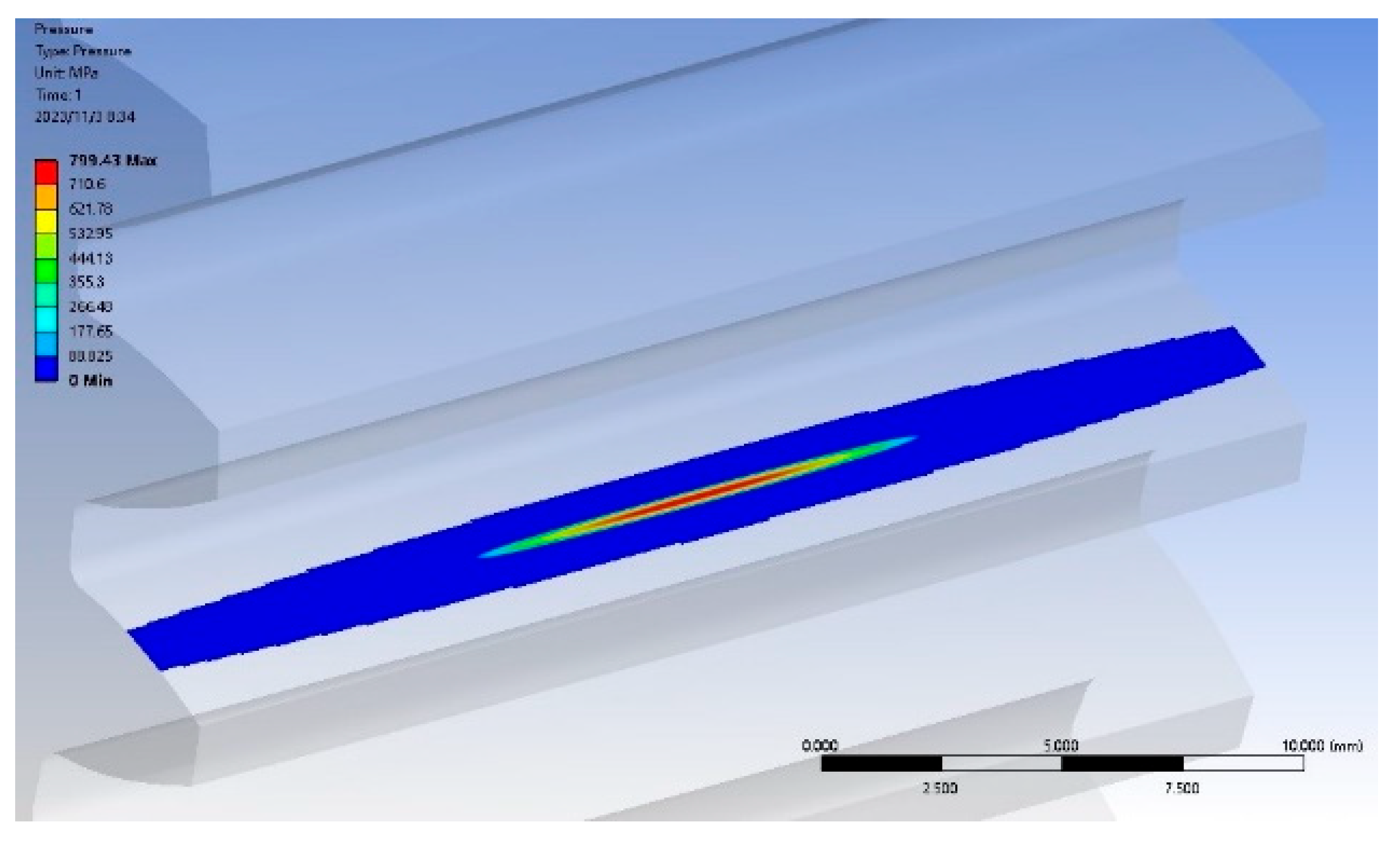

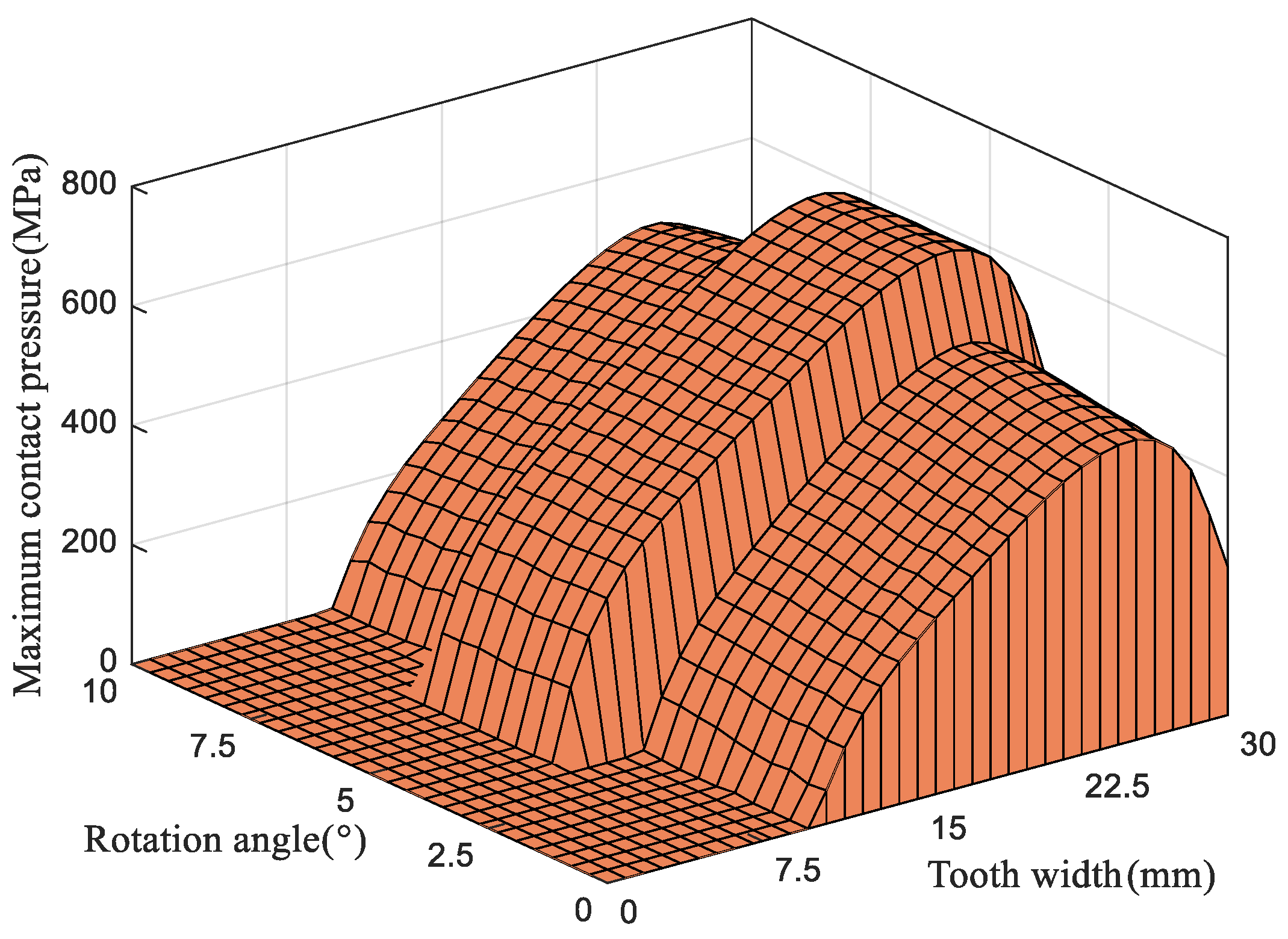

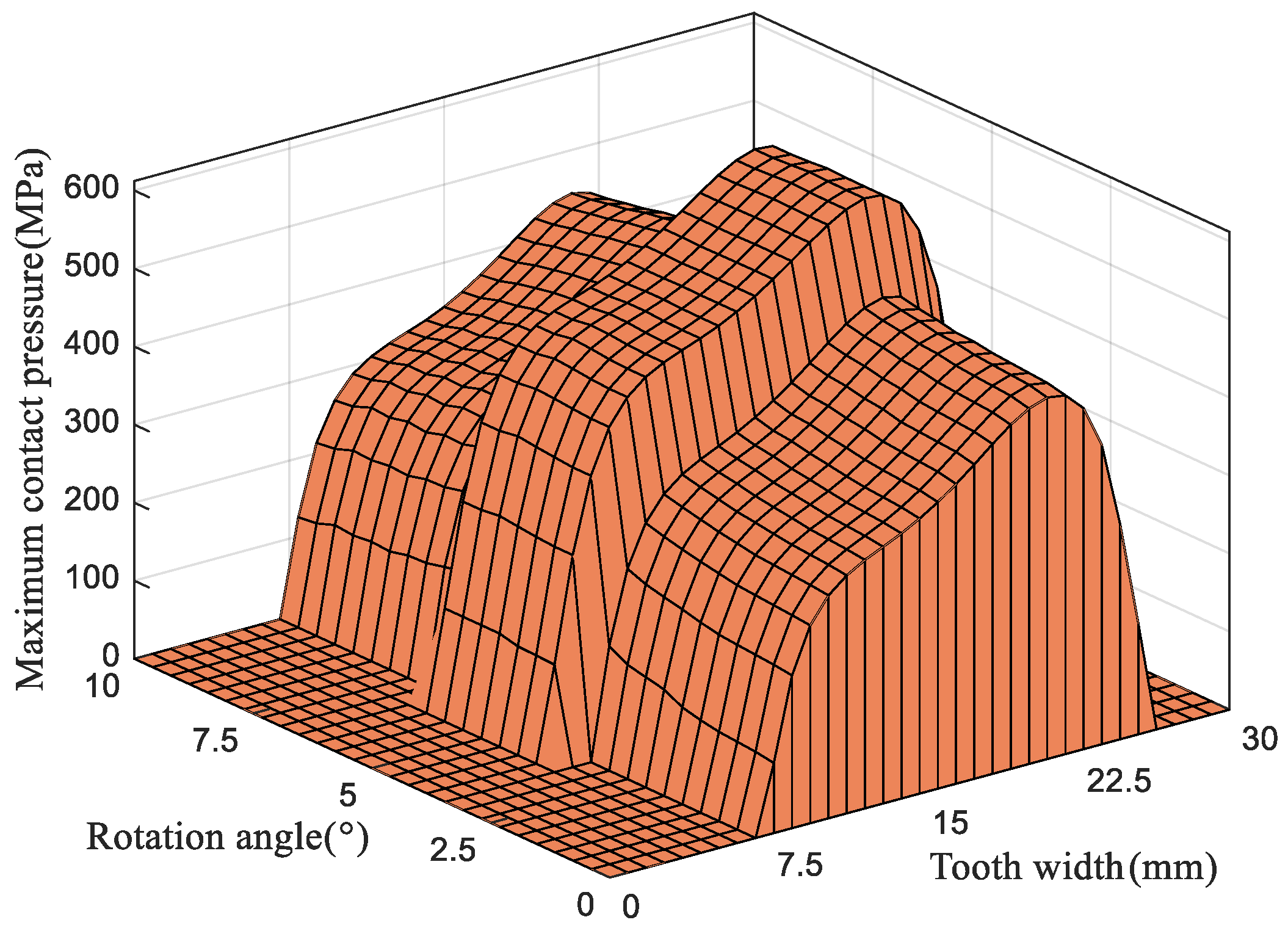

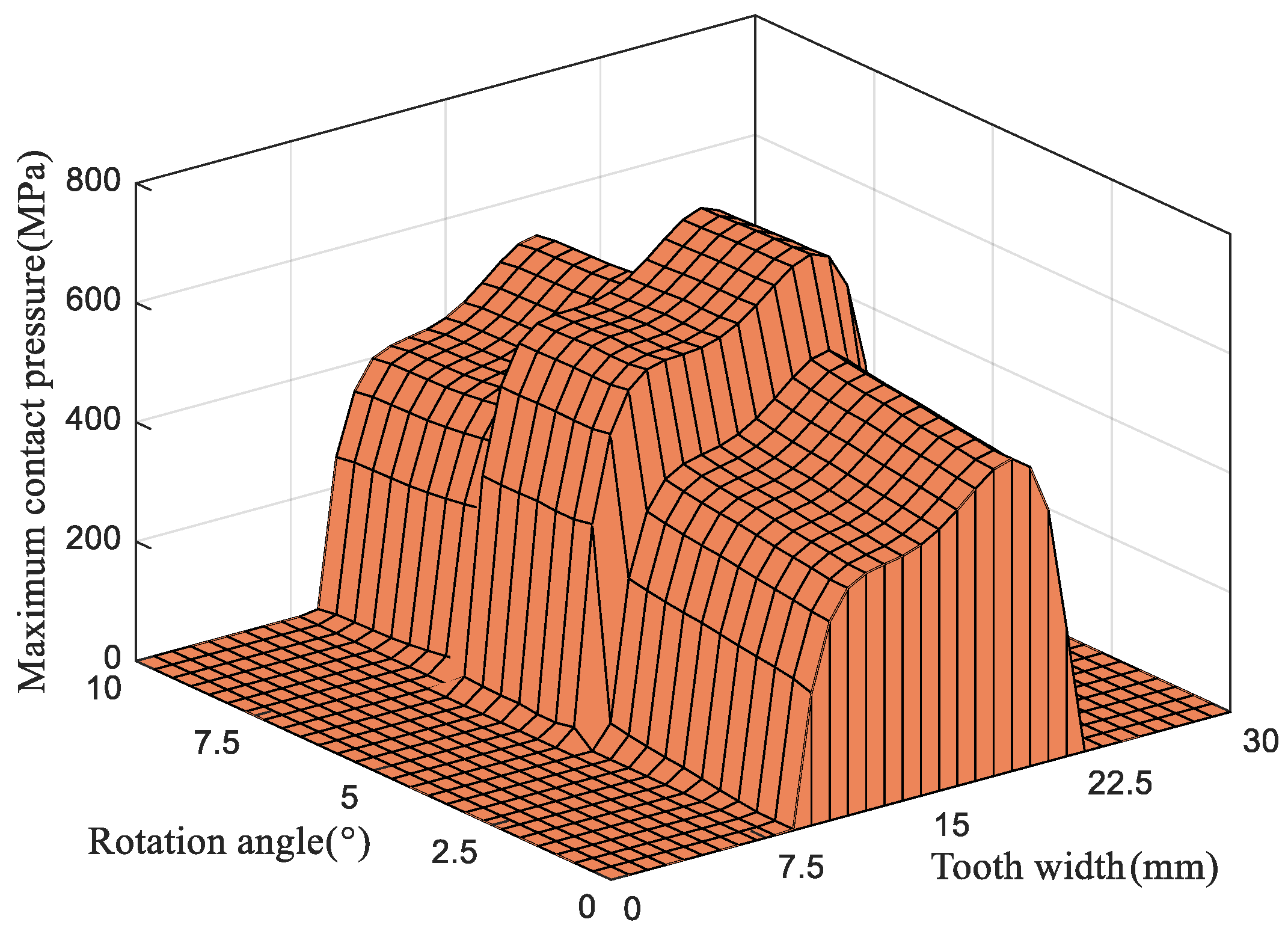

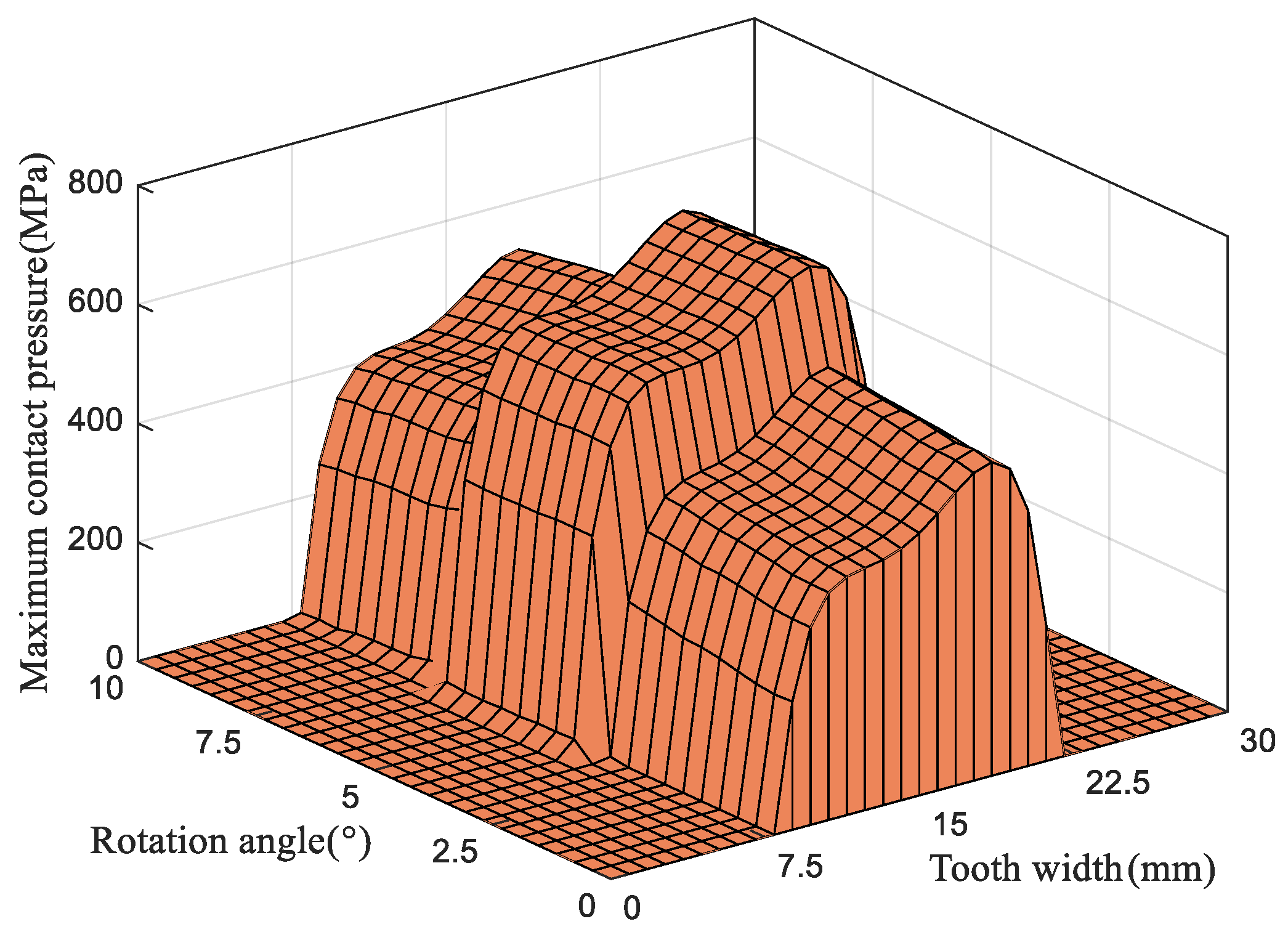

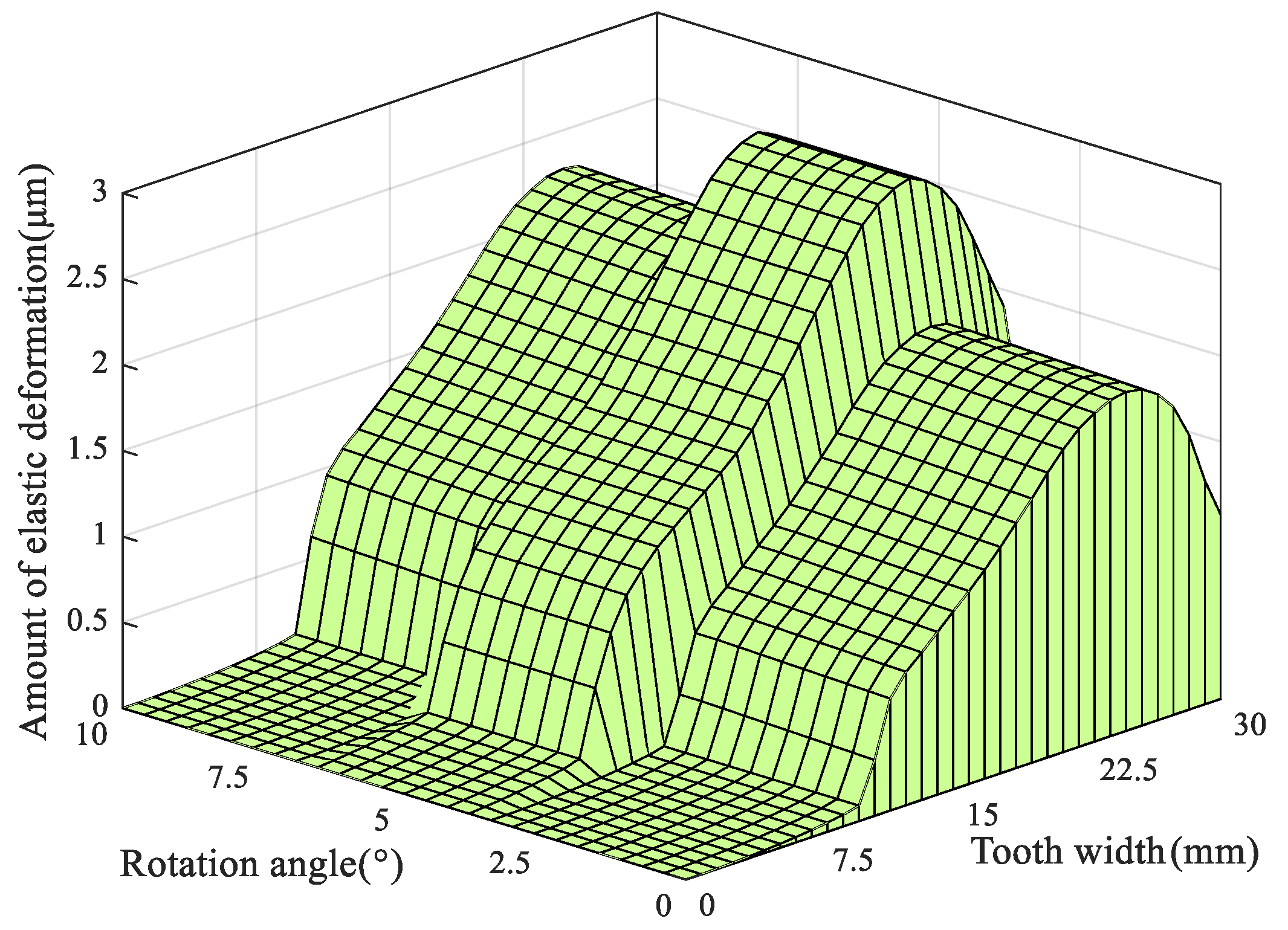

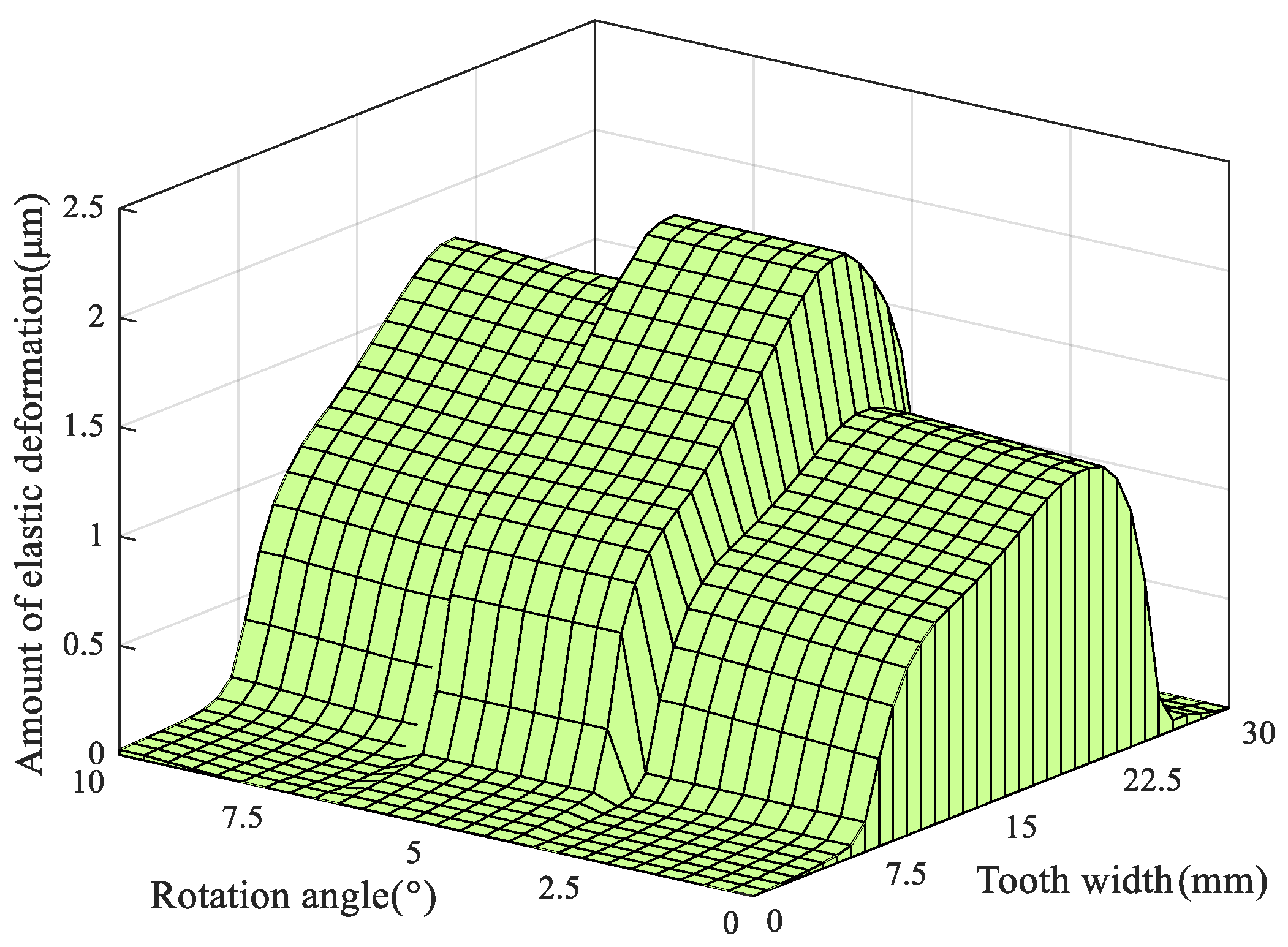

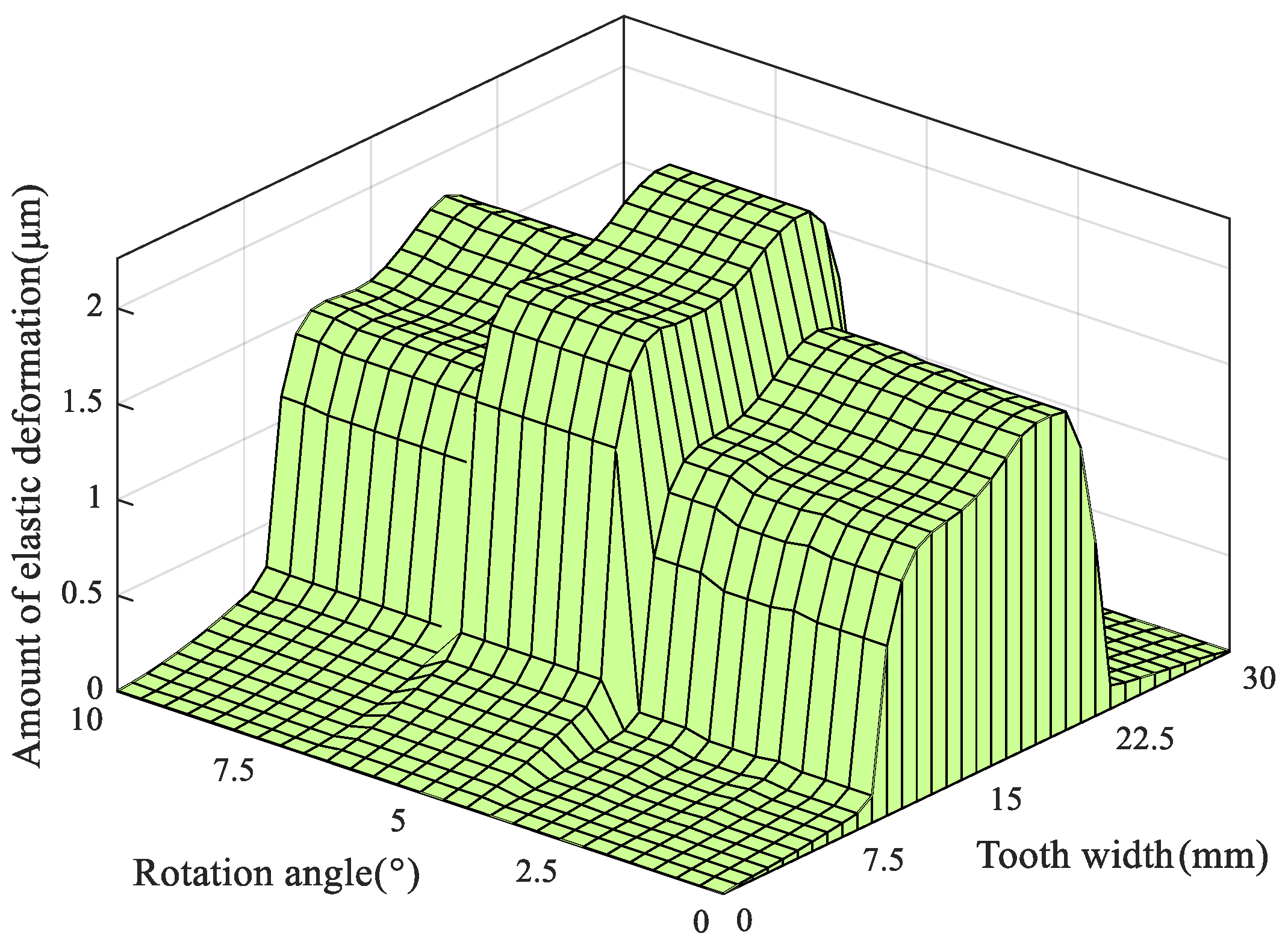

5.4. Influence of the Longitudinal Modification Coefficient on Contact Pressure and Tooth Surface Elastic Deformation

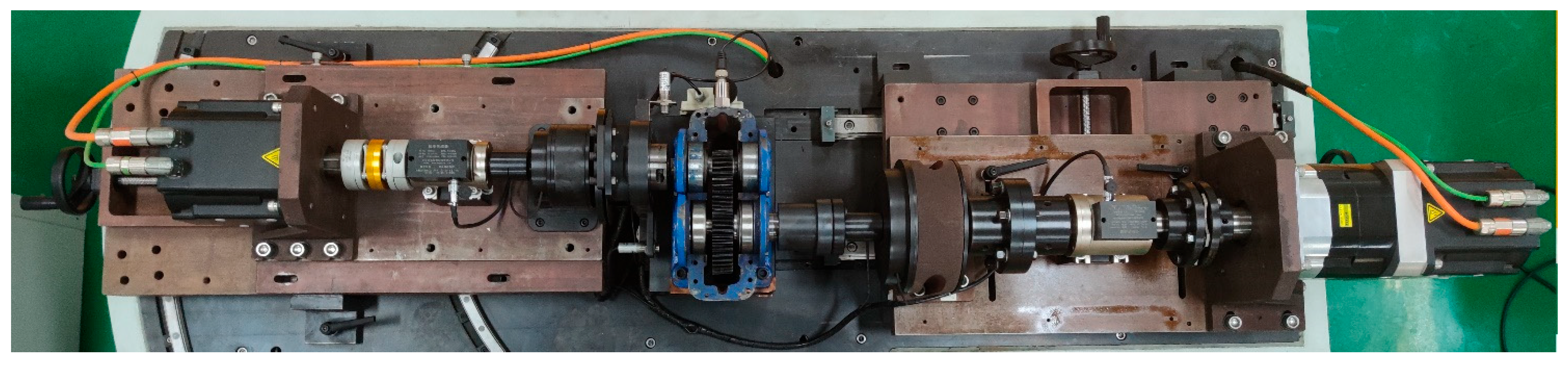

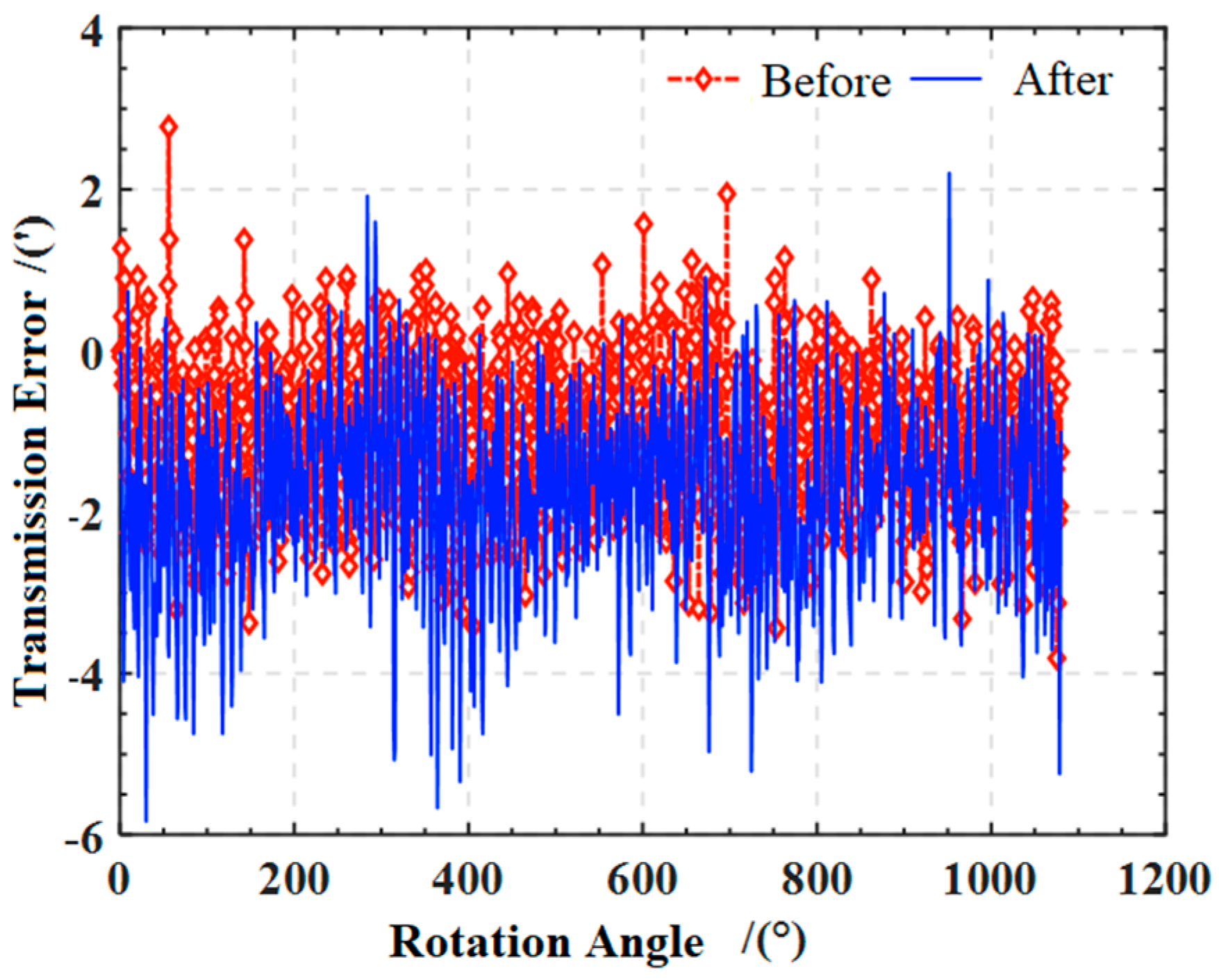

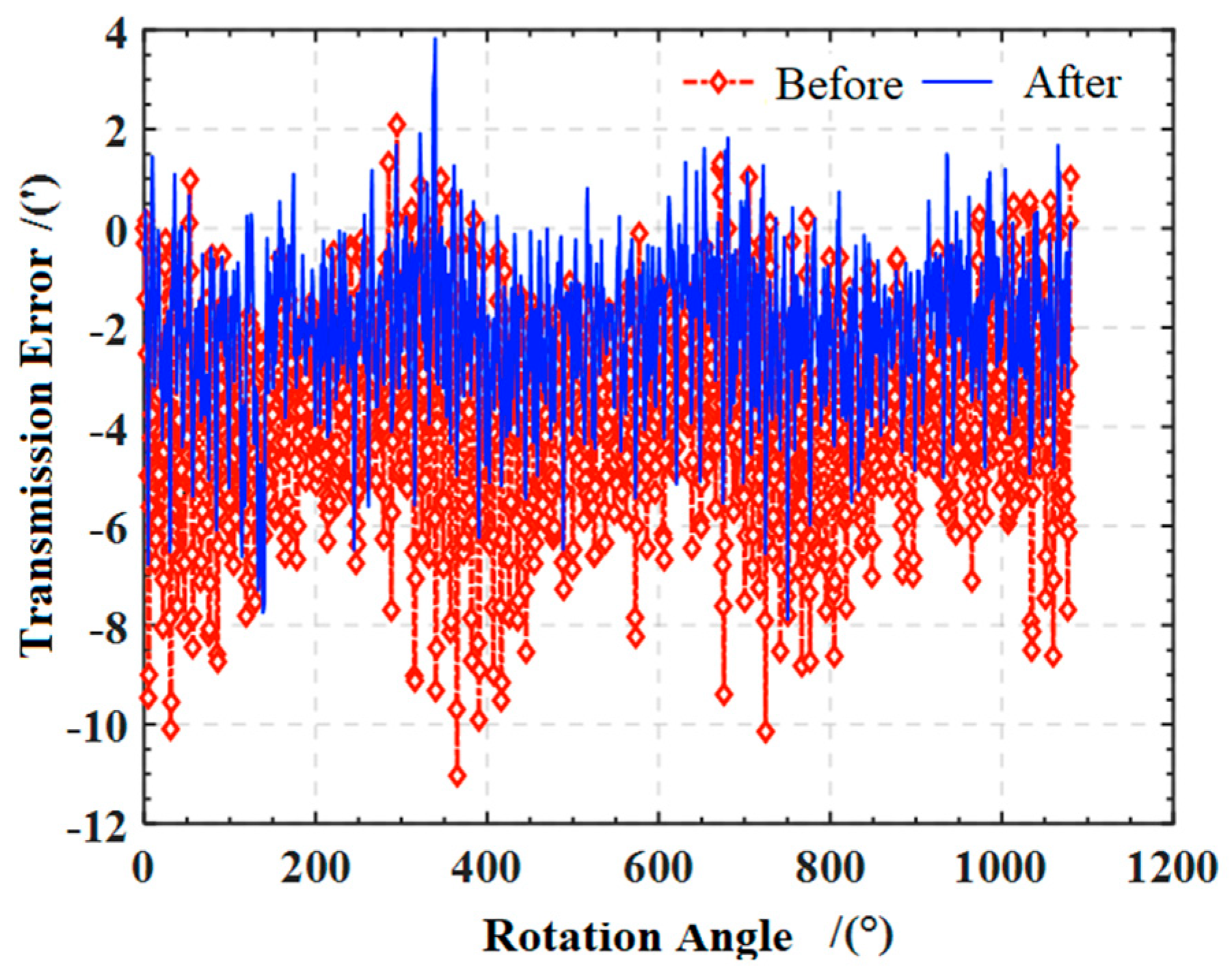

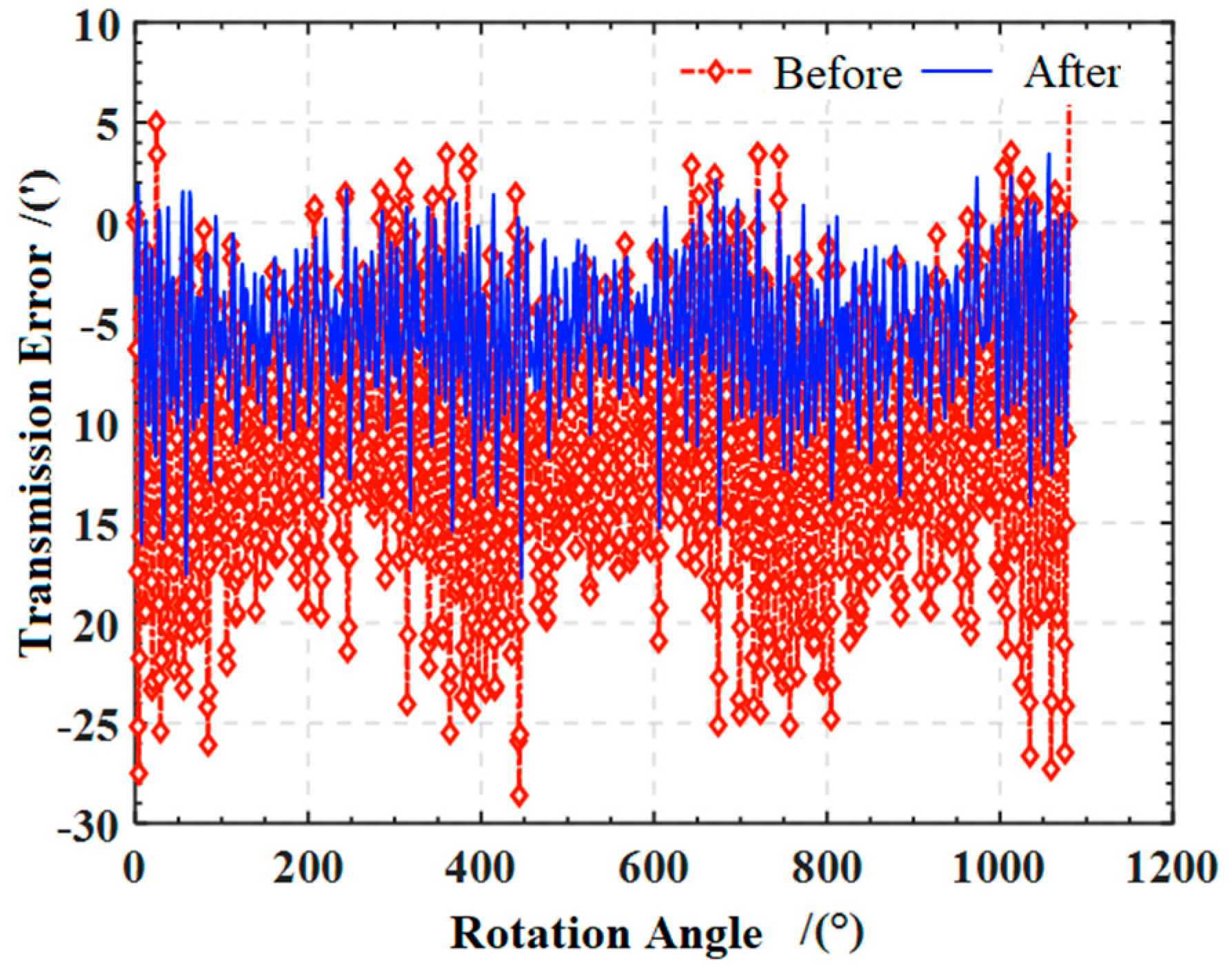

5.5. Experimental Verification

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhao, H.; Xu, G.; Li, Z. Advanced design strategies and applications for enhanced higher-order multisegment denatured Pascal curve gears. Sci. Rep. 2020, 14, 27137. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, C.B.; Liu, Y.P.; Wei, Y.Q. Dynamic contact characteristics analysis of elliptic cylinder gear under different load conditions. J. Huazhong Univ. Sci. Technol. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 47, 103–107. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.T.; Chen, D.F. Design, manufacture, inspection and application of non-circular gears. J. Mech. Eng. 2020, 56, 55–72. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, C.B.; Liu, Y.P.; Wei, Y.Q.; Deng, H.Q.; Xu, J. Analysis of nonlinear dynamic characteristic of elliptic gear transmission system. J. Jilin Univ. (Eng. Technol. Ed.) 2020, 50, 483–493. [Google Scholar]

- Pedrero, J.I.; Pleguezuelos, M.; Sánchez, M.B. Analysis of the tip interference in low gear ratio internal spur gears with profile modification. Forsch. Ingenieurwesen 2023, 87, 891–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrero, J.I.; Sánchez, M.B.; Pleguezuelos, M. Analytical model of meshing stiffness, load sharing, and transmission error for internal spur gears with profile modification. Mech. Mach. Theory 2024, 197, 105650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleguezuelos, M.; Sánchez, M.B.; Pedrero, J.I. Analytical model for meshing stiffness, load sharing, and transmission error for helical gears with profile modification. Mech. Mach. Theory 2023, 185, 105340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleguezuelos, M.; Sánchez, M.B.; Pedrero, J.I. Analytical model for meshing stiffness, load sharing, and transmission error for spur gears with profile modification under non-nominal load conditions. Appl. Math. Model. 2021, 97, 344–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrero, J.I.; Sánchez-Espiga, J.; Sánchez, M.B.; Pleguezuelos, M.; Fernández-del-Rincón, A.; Viadero, F. Simulation and validation of the transmission error, meshing stiffness, and load sharing of planetary spur gear transmissions. Mech. Mach. Theory 2024, 203, 105800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrero, J.I.; Pleguezuelos, M.; Sánchez, M.B. Influence of surface wear on the meshing stiffness and transmission error of internal spur gears with profile modification. Forsch. Ingenieurwesen 2025, 89, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.Q.; Song, C.C.; Wei, B.Y. Multi-objective orthogonal test simulation and modification parameter design based on ease-off topology. J. Mech. Transm. 2022, 46, 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- Stadtfeld, H.J. What “ease-off” shows about bevel and hypoid gears. Gear Technol. 2001, 18, 8–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, M.B.; Pleguezuelos, M.; Pedrero, J.I. Influence of profile modification on the transmission error of spur gears under surface wear. Mech. Mach. Theory 2024, 191, 105473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abruzzo, M.; Beghini, M.; Romoli, L.; Santus, C. Design for manufacturing of a spur gears profile modification based on the static transmission error for improving the dynamic behavior. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2023, 129, 1999–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, F.H.; Silva, G.C.; Chui, D.S. Vibration attenuation on spur gears through optimal profile modification based on an alternative dynamic model. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 2024, 46, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabrouk, M.; Liu, H.; Pengfei, Y.; Pu, G. Dynamic characteristics analysis of gear tooth modification in a three-stage gear system. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part D J. Automob. Eng. 2025, 239, 1083–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Wang, S.M.; Li, F. High-order contact analysis method of spiral bevel gear tooth surface based on ease-off. J. Aerosp. Power 2023, 39, 243–252. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.Q.; Guo, Y.L.; Wei, B.Y.; Cao, X.M. Research on meshing simulation analysis method for complex flanks based on surface synthesis method. J. Mech. Transm. 2022, 46, 16–20. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.Q.; Wei, B.Y.; Xie, X.K.; Li, J.Q. Ease-off surface topological modification of helical gear tooth surface calculation method of adhesive wear. J. Aerosp. Power 2023, 38, 2982–2990. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.Q.; Ma, P.P.; Guo, X.D. Contact characteristics control method of spiral bevel gears based on Ease-off. J. Beijing Univ. Technol. 2018, 44, 1024–1031. [Google Scholar]

- Nie, S.W.; Jiang, C.; Deng, X.Z.; Su, J.X.; Yang, J.J.; Wang, J.H. Flank modification method of hypoid gears with Ease-off topology correction. China Mech. Eng. 2019, 30, 2709–2715. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.J.; Gong, F.; Zhang, H. Tooth profile modification and tooth contact analysis of precision forging spiral bevel gear. J. Jiangsu Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 39, 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litvin, F.L.; Fuentes, A.; Gonzalez-perez, I.; Carvenalie, L.; Kawasaki, K.; Handschuh, R.F. Modified involute helical gears: Computerized design, simulation of meshing and stress analysis. Comput. Methods Appl. Mech. Eng. 2003, 192, 3619–3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.Q.; Li, Z.Y.; Liu, Y.P.; Guo, R.; Yang, D.; Luo, L.; Chen, Z.M. Geometric contact characteristics and sensitivity analysis of variable hyperbolic circular-arc-tooth-trace cylindrical gear with error theory considered. J. Northwestern Polytech. Univ. 2022, 40, 679–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.Z.; Li, X.D.; Yin, X.M.; Jia, H.T.; Guo, F. Design and form grinding principle of linear triangular end relief for double helical gears. J. Mech. Eng. 2023, 59, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.Y.; Chen, X.M.; Luo, C.W. Contact analysis of spur gears based on longitudinal modification and alignment errors. J. Cent. South Univ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 43, 1703–1709. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.P.; Yun, B.B.; Wei, Y.Q.; Dong, C.B.; Ren, Z.T. Research on digital design and tooth shape optimization of non-circular gears based on envelope features. J. Mech. Transm. 2022, 46, 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Zheng, F.Y. Profile modification method for non-cylindrical gear based on shaper cutter. Hoisting Conveying Mach. 2018, 46, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.W.; Liu, Y.P.; Gong, J.; Wei, Y.Q.; Zhao, G. A novel method for longitudinal modification and tooth contact analysis of non-circular cylindrical gears. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2022, 36, 6157–6170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S.W.; Deng, J.; Deng, X.Z.; Yang, J.J.; Li, J.B. Tooth surface error equivalent correction method of spiral bevel gears based on Ease off topology. China Mech. Eng. 2017, 28, 2434–2440. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.X. Free Curves and Surfaces Modeling Technology; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2001; pp. 88–168. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Cao, X.M.; Deng, X.Z.; Lei, B.Z. Research of spiral bevel gear tooth surface modification technique based on machining center. J. Mech. Transm. 2016, 40, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.H.; Fang, Z.D.; Wang, C. Digital simulation of spiral bevel gears real tooth surfaces based on non-uniform rational B-spline. J. Aerosp. Power 2009, 24, 1672–1676. [Google Scholar]

- Litvin, F.L.; Fuentes, A. Gear Geometry and Applied Theory, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2004; pp. 12–20. [Google Scholar]

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of teeth | 39 |

| Modulus (mm) | 2 |

| Addendum coefficient | 1 |

| Tip clearance coefficient | 0.25 |

| Tooth width (mm) | 30 |

| Pitch curve equation | |

| Pressure angle at the pitch curve (°) | 20 |

| Material | 38CrMoAI |

| Gear accuracy | 6 |

| Part Name | Model | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Torque sensor | YH-502 | The measuring ranges are 20 N·m and 2000 N·m, respectively. Measurement accuracy: ±0.1%. Power supply voltage: 24 VDC. Output signal: 10 ± 5 kHz. Torque accuracy: . Frequency response: |

| Noise sensor | RS-ZS-V05-2 | Range: 30–120 dB. Frequency range: 20 Hz–12.5 kHz. Measurement error: ±1.5 dB |

| Infrared temperature sensor | CK-01A | Temperature range: −20~300 °C. Spectral range: 8–14 μm. Measurement accuracy: ±1%. Response time: 50–300 ms optional |

| Vibration sensor | CA-YD-107 | Frequency response: 0.5–6000 Hz. Maximum lateral sensitivity: ≤5%. Axial sensitivity: . Magnetic sensitivity: 2 g/T. Base strain: |

| Circular grating | K-100 | Power supply voltage: 24 VDC. Resolution: 48000 P/R. Protection grade: IP50 |

| AC servo motor | MSME504G | Rated speed: 3000 rpm. Rated voltage: 400 VAC (three-phase). Torque: 15.9 N·m. Protection grade: IP67 |

| Servo motor driver | MFDTA464 | Rated voltage: 400 VAC (three-phase) |

| PLC | S7-200SMART | Power supply voltage: 220 VAC. I/O point: 30. AO channel: 4 |

| Data acquisition card | NI-6351 | Sampling rate:1.25 MS/s. AI channel: 16. A/D accuracy: 16 bits. AO channel: 2. DIO channel: 24. Counting channel: 4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, S.; Wang, Y. Tooth Surface Contact Characteristics of Non-Circular Gear Based on Ease-off Modification. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 12707. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312707

Liu S, Wang Y. Tooth Surface Contact Characteristics of Non-Circular Gear Based on Ease-off Modification. Applied Sciences. 2025; 15(23):12707. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312707

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Shukai, and Yanzhong Wang. 2025. "Tooth Surface Contact Characteristics of Non-Circular Gear Based on Ease-off Modification" Applied Sciences 15, no. 23: 12707. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312707

APA StyleLiu, S., & Wang, Y. (2025). Tooth Surface Contact Characteristics of Non-Circular Gear Based on Ease-off Modification. Applied Sciences, 15(23), 12707. https://doi.org/10.3390/app152312707